Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases are often accompanied by neuroinflammation and impairment of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) mediated by activated glial cells through their release of proinflammatory molecules. To study the effects of glial cells on mouse brain endothelial cells (mBECs), we developed an in vitro BBB model with inflammation by preactivating mixed glial cells (MGCs) with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) before co-culturing with mBECs to study the influence of molecules released by activated MGCs. The response of the mBECs to activated MGCs was compared to direct stimulation with LPS. The cytokine profile of activated MGCs was analyzed together with their effects on the mBEC’s integrity, expression of tight junction proteins, adhesion molecules, and BBB-specific transport proteins. Stimulation of MGCs significantly upregulated mRNA expression and secretion of several pro-inflammatory cytokines. Co-culturing mBECs with pre-stimulated MGCs significantly affected the barrier integrity of mBECs similar to direct stimulation with LPS. The gene expression levels of tight junction proteins were unaltered, but tight junction proteins revealed rearrangements with respect to subcellular distribution. Compared to direct stimulation with LPS, the expression of cell-adhesion molecules was significantly increased when mBECs were co-cultured with prestimulated MGCs and thus pre-activating MGCs transforms mBECs into a proinflammatory phenotype.

Keywords: Blood-brain barrier, Neuroinflammation, In-vitro BBB model, Glial cells, Lipopolysaccharide

Subject terms: Blood-brain barrier, Biological techniques, Biological models

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are increasingly common in the rapidly aging population1. They affect the central nervous system (CNS) by progressive cellular dysfunction and cell death in specific brain areas leading to diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and multiple sclerosis (MS)2,3. Neurodegenerative diseases are often accompanied by neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier (BBB) impairment mediated by activated glial cells (microglia and astrocytes), which trigger the release of proinflammatory cytokines4,5.

The BBB protects the brain from harmful substances circulating in the bloodstream by regulating the transport of molecules, cells, and ions from the blood to the brain. The BBB consists of a monolayer of specialized brain endothelial cells (BECs) supported and regulated by pericytes and astrocytes6. The BECs are tightly interconnected by tight junctions, like claudin-5 (CLD5) and occludin (OCLN), which have intracellular domains that bind the cytoplasmic scaffold proteins zonula occludens (ZO1-3). Tight junctions are responsible for the integrity of the BBB by regulating paracellular diffusion, thereby ensuring low passive transport into the brain6.

Activation of glial cells can affect the integrity of the BBB, but decreased integrity of the BBB can also activate glial cells, why it remains unclear whether BBB dysfunction is a cause or a result of neurodegeneration with neuroinflammation5. Microglia cells are the brain’s resident immune cells, and together with the astrocytes, these protect the CNS from insults, like infection, injury, and disease5,7. Through pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), glial cells recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and become activated. When activated, microglia and astrocytes can polarize into a pro- (M1, A1) or anti-inflammatory phenotype (M2, A2)5,8–10. M1 microglia secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines like tumor necrosis factor α, (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and interleukin 6 (IL-6), which are known to decrease the BBB permeability and alter TJ protein expression4,9,11–13, but also recruit additional cells, e.g., leukocytes, from the circulation by upregulating the expression of cell adhesion molecules, like intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM-1) on BECs14,15. The microglia proinflammatory M1 phenotype can be activated via proinflammatory stimuli like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), found in the outer wall of gram-negative bacteria, and interferon-γ (INFγ)4,8.

Transwell assays are popular for modeling the BBB in vitro and are widely used to study transport mechanisms and drug delivery strategies at the BBB16. Among the basic characteristics, a valid in vitro model expresses low paracellular permeability, high expression of tight junction proteins, and several functional transporters, including efflux transporters4,16, however, these characteristics correlate to an intact BBB. In vitro BBB models for studying the mechanisms and the cell-cell interactions related to neuroinflammation and BBB impairment in neurodegenerative diseases, are also highly relevant.

A popular source for modeling inflammatory stimuli in vivo and in vitro is LPS, as this molecule is a potent PAMP that triggers a pronounced inflammatory cascade, resulting in the production of inflammatory mediators10,17–19. In vivo, LPS triggers neuroinflammation both upon cerebral systemic administration10,15. In vitro, LPS can stimulate glial cells to secrete proinflammatory cytokines3,18 but has also been used to stimulate BECs directly leading to changed BBB permeability17,20,21. This does not resemble the effect on the BECs from proinflammatory cytokines secreted by activated glial, but rather the direct effect of LPS on the barrier integrity.

The present study, therefore, attempted to develop and explore an in vitro BBB model with inflammation where mouse mBECs (mBECs) are co-cultured with mixed glial cells (MGCs) pre-stimulated with LPS and compare this model to direct stimulation with LPS in both the luminal and abluminal chamber. We thereby aimed to investigate the response of mBECs co-cultured with activated MGCs (aMGCs) and thereby the effect of the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from MGCs compared to the stimuli obtained by direct LPS stimulation. We hypothesized that preactivation of MGCs would cause an inflammatory state of the mBECs mimicking neuroinflammation to a greater extent than direct LPS stimulation. Our analyses show that pre-stimulating MGCs before co-culturing with mBECs results in high secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which subsequently alters the integrity of mBECs, reorganizes their tight junction expression, and increases their expression of adhesion molecules, thereby transforming mBECs to exhibit a neuroinflammatory phenotype.

Results

Stimulating MGSs with LPS for only three hours is sufficient for MGC activation

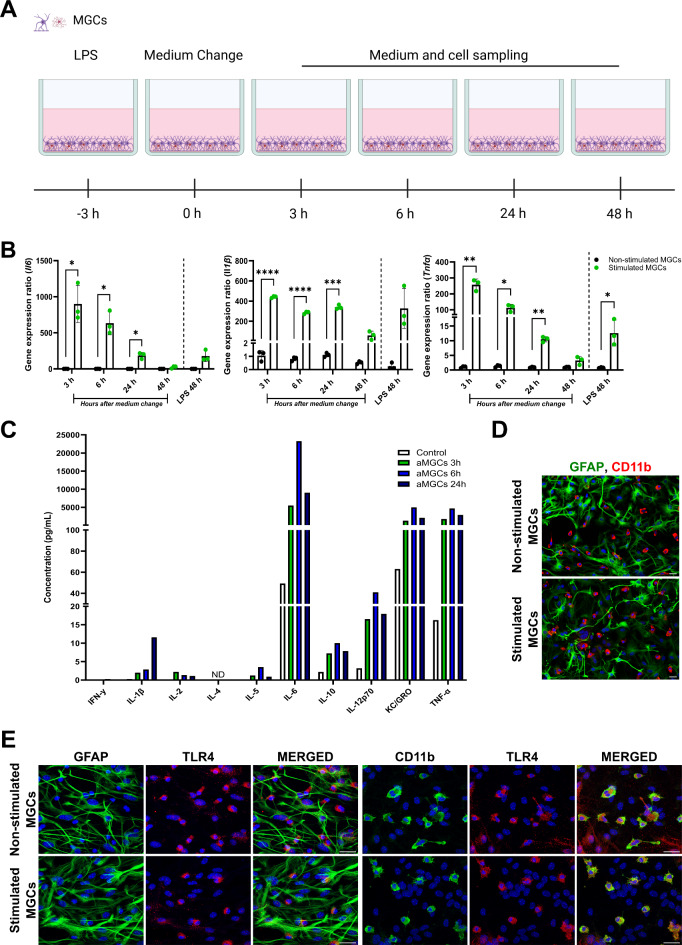

To investigate the effect of LPS on MGCs, these were stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS for three hours before the medium was changed to remove LPS. Medium and MGCs were subsequently sampled three, six, 24, and 48 h later (Fig. 1A), to measure the levels of inflammatory cytokines. Three hours after removing LPS, the relative gene expression of Il6, Il1β, and Tnfα significantly increased compared to non-stimulated MGCs (Fig. 1B). The gene expression levels of all three cytokines remained significantly elevated for 24 h but decreased to levels close to baseline after 48 h. The highest expression of the cytokines was found after three hours and steadily declined hereafter, except for Il1β, which remained at high levels for 24 h. When stimulating the MGCs with LPS continuously for 48 h, the gene expression of the cytokines increased, however only Tnfα was found to be significantly higher than the non-stimulated MGCs (Fig. 1B). To investigate the cytokine profile secreted by the LPS-stimulated MGCs, a Meso Scale Discovery electrochemiluminescent assay was carried out using the medium collected three, six, and 24 h after LPS removal (Fig. 1C). Il-6 was secreted in the highest concentration, peaking 24 h after LPS removal, followed by TNF-α and keratinocyte chemoattractant/growth-regulated oncogene (KC/GRO, also known as CXCL1) and IL-12p70, which all peaked after six hours. The LPS-stimulated MGCs also secreted IFNγ, IL-2, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-1β though at low levels, and no detectable secretion of IL-4 was observed (Fig. 1C). Together these data reveal that three hours of LPS stimulation was sufficient to activate MGCs and increase their expression and secretion of multiple cytokines for at least 24 h.

Fig. 1.

Activation of mixed glial cells. (A) Mixed glia cultures (MGCs) were stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS for three hours, followed by a medium change, to remove LPS stimulation. The MGCs were lysed after 3, 6, 24, and 48 h (h) to investigate mRNA expression of Il6, Il1β, and Tnfα, and medium sampled at each time interval to measure secretion of inflammatory cytokines. For comparison, MGCs were incubated with LPS for 48 h. Non-stimulated MGCs were used as controls. (B) Relative gene expression of Il6, Il1β, and Tnfα expression significantly increased three hours after LPS removal and remained elevated for 24 h. The expression of the cytokines was highest three hours after LPS removal, followed by a steady decline. 48 h after LPS removal, the gene expression levels had declined to levels close to normal. When MGCs were stimulated for 48 consecutive hours the expression of IL1β, and Tnfα significantly increased, but the expression was not as high as observed after only three-hour stimulation. Statistical changes in gene expression were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Significance levels were *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. (C) Meso Scale Discovery electrochemiluminescent assay on medium sampled from non-stimulated and stimulated MGCs 3, 6, 24, and 48 h after LPS removal. Medium from three wells were pooled and run in duplicates. All measurements are in pg/mL, and the data refers to the duplicate mean (n = 1). (D-E) Immunocytochemical characterization of the MGCs cultures. (D) MGCs were LPS stimulated for three hours, the medium changed and after three hours the activated MGCs were stained for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; green) or cluster of differentiation 11b (CD11b; red), which are markers for astrocytes and microglial cells, respectively, and compared to non-stimulated MGCs. (E) The MGCs were double-labeled for astrocytes (GFAP) and Toll-like receptor type 4 (TLR4 (red)), or microglia (CD11b) and TLR4, showing that TLR4 is primarily found expressed on microglia cells. The nuclei are stained with DAPI (Blue). Scale bar 25 μm.

Next, the composition of the MGC culture and expression of the TLR4 was investigated (Fig. 1D-E). The cultures were stained for the astrocytic marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and the microglia marker, cluster of differentiation molecule 11B (CD11b). The MGCs were found to be a mixture of GFAP-expressing astrocytes, and CD11b-expressing microglia cells. No major difference in morphology or distribution of the two cell types was found in response to LPS stimulation. LPS exerts its effect through the stimulation of the TLR4 receptor22,23 and independent of LPS stimulation, TLR4 colocalized with the microglia marker CD11b (Fig. 1E), thus showing the microglial cells in the MGC cultures expressed TLR4, which complies with several studies23,24. Although it cannot be excluded that TLR4 also activates astrocytes directly25, TLR4 expression was not observed in astrocytes in our study, suggesting the effect of LPS of stimulation on MGCs could be assumed to be mainly through the initial activation of microglial cells and subsequent activation of astrocytes by microglia secreted cytokines (Fig. 1E). The expression of TLR4 was also confirmed in mBECs on both a gene and protein level and was likewise not found to be influenced by LPS stimulation (data not shown).

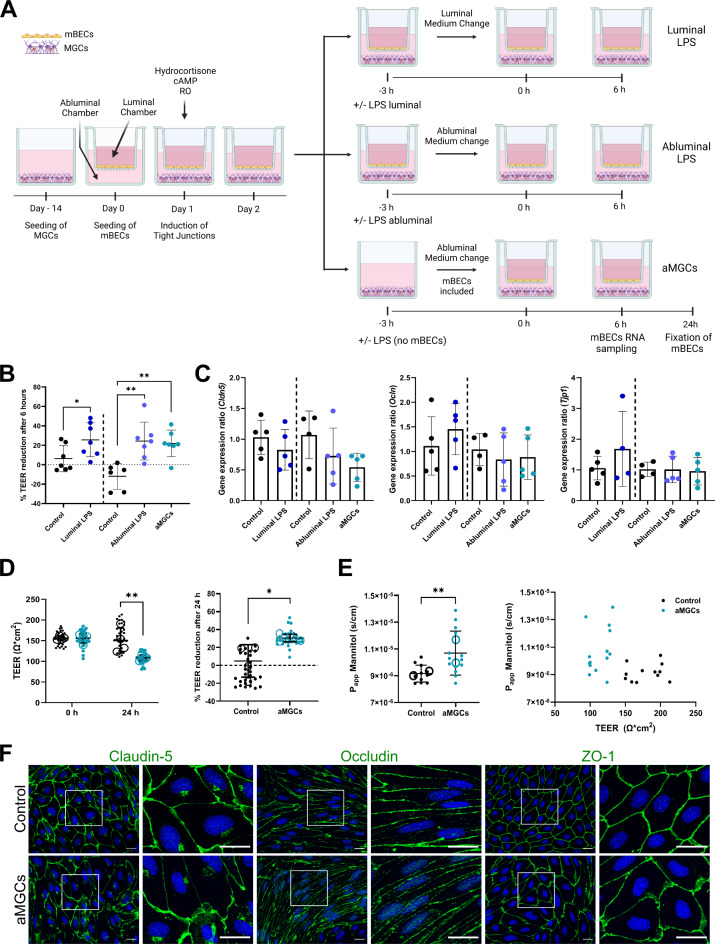

Co-culturing pre-LPS stimulated MGCs with mBEC affects barrier integrity similarly to direct LPS stimulation of the mBECs

Next to investigate the effect of the cytokine response, created by pre-stimulating MGCs with LPS, on the integrity of mBECs, an in vitro BBB model with inflammation was established (referred to as aMGCs) (Fig. 2). This model was compared to mBECs directly influenced by three hours of LPS stimulation in either the abluminal or luminal chamber (referred to as abluminal LPS and luminal LPS, respectively), followed by a medium change to remove LPS. All three cultures were compared to non-stimulated MGCs, following the same procedures of medium change in either the luminal or abluminal chamber (Fig. 2A). Firstly, the effect of activated MGCs and direct LPS on the mBECs integrity was analyzed by the measure of transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER). Mean TEER values of 131.9 ± 52.7 Ω*cm2 (luminal control), 144.4 ± 49.9 Ω*cm2 (luminal LPS), 146.1 ± 33.5 Ω*cm2 (abluminal control), 147.1 ± 47.7 Ω*cm2 (abluminal LPS) and 154.9 ± 49.5 Ω*cm2 (aMGCs) were measured before LPS stimulation. Nine hours after LPS stimulation (6 h after LPS removal) the relative TEER reduction was calculated (Fig. 2B). Luminal LPS stimulation significantly reduced the barrier integrity of the mBECs by 25.6 ± 17.5% compared to luminal control, where only a 6.3 ± 13.5% reduction was observed (P = 0.0395) (Fig. 2B). Likewise a significant reduction was seen when mBECs were stimulated abluminal with LPS (24.4 ± 19.5%, P = 0.002) or co-cultured with pre-stimulated aMGCs (21.9 ± 13.7%, P = 0.0036) compared to abluminal control, which increased by 12 ± 13.3%.

Fig. 2.

Establishment and evaluation of barrier integrity in the in-vitro blood-brain barrier (BBB) models with inflammation. (A) Mixed glia cultures (MGCs) were cultured for ~ 14 days. Primary mice brain endothelial cells (mBECs) were seeded onto filter inserts (Day 0) with induction of tight junction proteins by co-culturing the mBECs with non-stimulated MGCs and the addition of cAMP, RO, and hydrocortisone on day 1. On day 2, three different inflammatory models were established. Luminal/Abluminal LPS: 100ng/mL LPS was added to either the luminal or abluminal chamber of the BBB model for three hours before changing the medium. Control BBB models were subjected to a change of medium in either the luminal (luminal control) or abluminal chamber (abluminal control). aMGCs: the BBB model was established by pre-stimulating MGCs with 100 ng/mL LPS for three followed by a change of medium and coculturing with mBECs. All models were subsequently incubated for six hours, following lysis of mBECs, for gene expression analysis. mBECs cultured with aMGCs (and the abluminal control) were additionally cultured for 24 h, fixated, and used for immunocytochemical analysis. (B) The percentage reduction in trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) of the luminal, abluminal LPS, and aMGC models. The integrity of the mBECs is significantly affected by the addition of LPS, but also by the pre-activation of MGCs. Statistical differences were analyzed using an unpaired t-test (control vs. luminal LPS), and an ordinary one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. n = 6–7, each representing the mean of three filter inserts. (C) The relative gene expression levels of the tight junction proteins Cldn5, Ocln, and Tjp1. No significant differences were found. n = 4–6. (D-E) The integrity and permeability were additionally analyzed in the novel aMGCs model. (D) TEER values displayed in superplots at 0 h, before mBECs are co-cultured with pre-stimulated aMGCs, and after 24 h of co-culturing. The percentage reduction in TEER is additionally displayed and both show a statistical reduction when mBECs are co-cultured with aMGCs. Statistical differences were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with Sidaks multiple comparisons t-test. Large open circles represent the mean of n = 4 repeated experiments with a total of 30–33 individual filter inserts (small closed circles). (E) The apparent permeability (Papp) of 3 H-D-Mannitol was likewise assessed at 24 h. A significantly higher Papp to 3 H-D-Mannitol was observed when mBECs were co-cultured with aMGCs compared to control mBECs, corresponding well with lower TEER values in these cultures. Large open circles represent the mean of n = 2 repeated experiments with a total of 12–14 individual filter inserts (small closed circles). All data are presented as mean ± SD. Significance levels were *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. (F) Immunolabelling of tight junction proteins occludin (OCLN), claudin-5 (CLD5), and zonula occludens 1 (ZO1) all in green and the nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). The scale bars correspond to 20 μm.

Inflammation has been associated with BBB impairment, which can involve the downregulation or degradation of tight junction proteins19,26,27. Therefore, the mBECs were investigated for potential changes in the gene expression pattern of three highly expressed tight junction proteins six hours after LPS removal. No significant changes were observed in the gene expression levels of Cldn5, Ocln, or tight junction protein 1 (Tjp1, also known as ZO1), when comparing luminal LPS to the luminal control and when comparing abluminal LPS and aMGC-stimulated mBECs with the abluminal control (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the decreased TEER was not accompanied by changed tight junction gene expression levels. However, a tendency towards a lower transcriptional expression of Cldn5 was seen in all direct LPS-stimulated models compared to controls, a tendency not observed for Ocln, or Tjp1 (Fig. 2C).

To further evaluate the barrier integrity of the aMGCs model, TEER and the paracellular permeability (Papp) to 3 H-D-Mannitol, a small molecule normally not able to cross the BBB, were investigated 24 h after co-culturing with the LPS pre-stimulated MGCs (aMGCs) (Fig. 2D-E). Furthermore, changes in the composition of tight junction proteins were likewise evaluated using immunocytochemical staining. Before co-culturing mBECs with aMGCs or non-stimulated MGCs (control) both cultures displayed TEER values above 130 Ω*cm[2 16,28,29 (Control: 156 ± 4.5 Ω*cm2, aMGCs: 156 ± 11.4 Ω*cm2). However, 24 h later mBECs of the aMGCs model had significantly lower TEER values (Fig. 2D), with an average of 108 ± 6.9 Ω*cm2, whereas the control mBECs remained at the same level with TEER values of 150.3 ± 30.2 Ω*cm2 (P = 0.004) (Fig. 2D). The percentage relative decrease in TEER, therefore showed a 4.8 ± 30.34% increase in TEER for control mBECs, while mBECs of the aMGC model showed a significant decrease in integrity, corresponding to 30.34 ± 4.2% (P = 0.0286) (Fig. 2D). When assessing the paracellular permeability of 3 H-D-Mannitol, a significantly higher Papp to 3 H-D-Mannitol was observed in mBECs co-cultured with aMGCs compared to control mBECs (1.1 × 10− 5±1.6 × 10-6 s/cm, 9.2 × 10− 6±6.3 × 10− 7 s/cm respectively) (P = 0.0045) corresponding well with the lower TEER values observed in these cells (Fig. 2E).

The tight junction composition and localization of the essential tight junction proteins OCLN, CLD5, or ZO1 in the mBECs of the aMGC model (Fig. 2F) were evaluated using immunocytochemistry with a focus on the subcellular localization of the proteins. The expression of the tight junction proteins was highly, evenly, and robustly expressed at the cell-cell borders of the mBEC cultured with non-stimulated MGCs (abluminal control), however, mBECs from the aMGC model showed some tendency to a more uneven and not coherently expressed protein expression, revealing small gaps between adjacent cells. However, a complete breakdown of the barrier integrity was not observed, due to TEER values staying above 110 Ω*cm2 and never dropping below levels measured in non-induced mBECs (30–50 Ω*cm2) and the Papp remaining in the low range for mBECs isolated from mice16,28,29 (Fig. 2E).

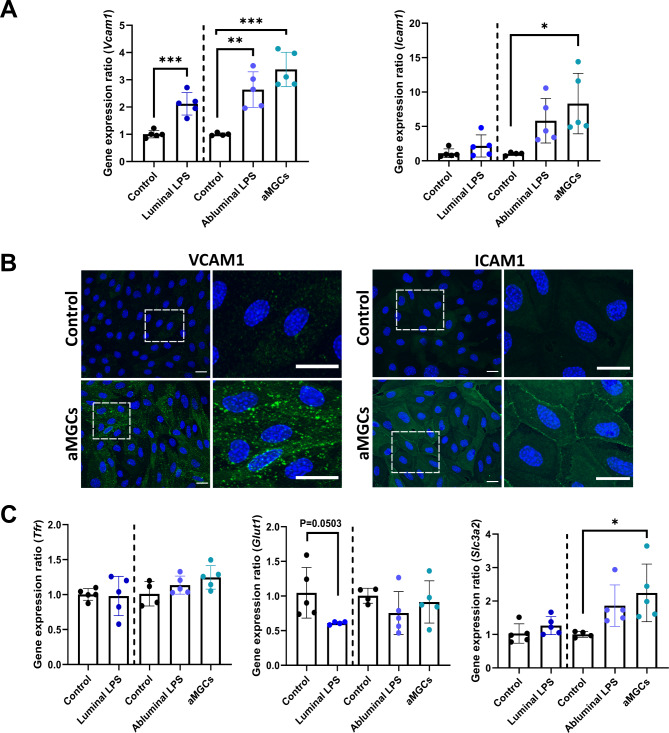

mBECs of the aMGCs model have increased expression of cell-adhesion molecules

Neuroinflammation in vivo is accompanied by increased expression of cell adhesion molecules for the recruitment of leukocyte migration across the BBB30–32. To further evaluate the inflammatory response in the mBECs, the relative gene expression of the two cell-adhesion molecules Icam1 and Vcam1 were investigated (Fig. 3A, B). mRNA expression of Vcam1 was significantly increased in mBECs stimulated with LPS in the luminal (P = 0.004) and abluminal chamber (P = 0.0026), but to an even higher degree when mBECs were co-cultured with LPS pre-stimulated MGCs (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 3A). Icam1 expression increased when LPS was added in the abluminal chamber, but only significantly when mBECs were co-cultured with pre-stimulated aMGCs compared to control mBECs (P = 0.0177) (Fig. 3A). The changes observed at the gene expression levels of the adhesion molecules were further investigated in mBECs of the aMGCs model using immunocytochemistry (Fig. 3B). ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression was almost non-detectable in the control mBECs but increased drastically with respect to its subcellular localization in mBECs of the aMGCs model after 24 h (Fig. 3B). This upregulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 indicates that the aMGCs model can mimic the upregulation of adhesion molecules observed in brain endothelial in vivo in diseases like MS33.

Fig. 3.

Co-culturing mBECs with aMGCs increases the expression of cell adhesion molecules and induces changes among potentially promising targets for BBB drug delivery. (A) The mBECs gene expression levels of vascular adhesion molecule 1 (Vcam1) significantly increased when stimulated with LPS, however, the highest increase was seen when mBECs were co-cultured with pre-stimulated aMGCs. Likewise, LPS stimulation increased mBECs expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Icam1) but only when these were abluminal stimulated with LPS, and only to a significant level when mBECs were co-cultured with aMGCs. (B) The increased expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, was confirmed in mBECs co-cultured with aMGCs using immunostainings, as mBECs co-cultured with non-stimulated MGCs have little or no expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 protein. Square boxes represent magnifications, which are displayed next to each condition. The nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue), Scale bar 20 μm. (C) mBECs gene expression levels of the transferrin receptor (Tfr), glucose transporter 1 (Glut1), and solute carrier family 3 member 2 (Slc3a2) showed no significant changes when stimulated with LPS, or co-cultured with aMGCs, except for cd98hc, which was significantly upregulated in mBECs of the aMGC model. Likewise, a tendency towards a reduction (P = 0.0503) was observed for Glut1 in mBECs of the luminal LPS model. (A, C) Statistical differences were analyzed using an unpaired t-test (control vs. luminal LPS), and an ordinary one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test, except for Tfr and Glut1, which were both analyzed using a Mann Whitney t-test (control vs. luminal LPS). All data are presented as Mean ± SD, n = 4–5. Significance levels were *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Finally, the changes in the gene expression levels of several potential drug delivery targets were investigated in all three models and compared to their respective controls. The mRNA expression levels of the transferrin receptor (Tfr), one of the most studied drug delivery targets at the BBB34, normally involved in the transport of iron into the brain were not influenced by the inflammatory response created by either direct or indirect LPS stimulation (Fig. 3C). This also attributed to the expression of the solute carrier, glucose transporter 1 (Glut1), responsible for glucose transport into the brain, which showed a tendency towards a lower expression when mBECs were directly stimulated with LPS in the luminal chamber (P = 0.0503). In comparison, the addition of LPS in the abluminal chamber or co-culturing mBECs with pre-stimulated aMGCs did not show the same tendency towards downregulated Glut1 mRNA expression. On the other hand, gene expression levels of solute carrier family 3 member 2 (Slc3a2), also known as the BBB target cluster of differentiation 98 heavy chain (CD98hc)35, significantly increased when mBECs were co-cultured with pre-stimulated aMGCs compared to the abluminal control (P = 0.0369) (Fig. 3C). Together these data show that mBECs respond to the inflammatory reaction created by LPS, by upregulating both adhesion molecules but also changing the expression of some BBB targets used for drug delivery purposes. The highest effect of LPS was however, observed in mBECs of the aMGC model that were co-cultured with MGCs pre-stimulated with LPS, suggesting this method of mimicking the effect of neuroinflammation on the BBB might be superior to the direct effect of LPS.

Discussion

This study reports on an in vitro BBB model with inflammation for studying the effects of proinflammatory mediators secreted by MGCs on the BEC’s integrity and phenotypic expression of cell adhesion molecules and transporter proteins. We developed a model, where MGCs are pre-stimulated with LPS for only three hours, which was sufficient to activate aMGCs before these were co-cultured with BECs. LPS-stimulated MGCs increased their expression and secreted a variety of pro- and inflammatory cytokines up to 24 h after removal of LPS. The effect of LPS is believed to be initiated through TLR422,23, primarily expressed by microglial cells. The inflammatory reaction created by pre-stimulating the MGCs with LPS significantly affected the BBB integrity and increased the expression of adhesion molecules, suggesting that this model is valid for further studies on the neuroinflammatory phenotype of BECs when influenced by proinflammatory mediators secreted by activated MGCs.

Stimulating MGCs with LPS for only three hours resulted in a strongly increased gene expression of Il1β, Il6, and Tnfα, which remained elevated for min 24 h. Both Il6 and Tnfα were expressed in the highest amounts three hours after removal of LPS stimuli, followed by a steadily declined expression, returning to normal after 48 h. The half-life of Tnfα mRNA from mice astrocytes has been measured to be 0.3 h, whereas it increases to 0.9 h following LPS stimulation36. The short half-life of Tnfα mRNA means that the MGCs continue to produce mRNA long after removing the LPS stimuli. Increased gene expression levels of Il6, Il1β, and TNFα upon 100 ng/ml LPS stimulation of primary microglial cells were reported previously but also confirmed on a protein level37.

We further analyzed the secretion of a panel of cytokines up to 24 h after LPS removal and found a robust secretion of IL-6, TNF-α, KC/ GRO (CXCL1), and IL-12p70 with peak secretion six hours after LPS was removed. The concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α were around 20 ng/mL and 4.7 ng/mL respectively. This is in line with a previous study demonstrating increased IL-6 and TNF-α secretion in brain homogenates after sepsis and in pure cultures of primary mouse astrocytes following stimulation with 100 ng/mL LPS38.

Normally, low levels of IL-6 are present in the brain, but during neuropathological changes as seen in MS, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer´s disease higher expression of IL-6 is observed39. IL-6 is furthermore essential for the symptom development associated with MS, as IL-6-deficient mice are resistant to the detrimental effects of the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model of MS40. IL-6 can stimulate a response through either canonical or trans-signalling. The IL-6 receptor α (IL-6R) is required for canonical signaling, and within the CNS, this receptor is only expressed by microglia, while cells like astrocytes, neurons, and endothelial cells, lack IL-6R but can respond to IL-6 through trans-signaling via soluble IL-6R residing in the cytoplasm. Hence, IL-6 can activate two distinct pathways, the classic anti-inflammatory pathway through the IL-6 receptor as well as the pro-inflammatory pathway through trans-signaling that mediates neurodegeneration39,41. Thus, IL-6 seems to have both beneficial and harmful effects41,42. IL-6 secreted by microglia can therefore via pro-inflammatory trans-signaling activate astrocytes to increase their expression and secretion of IL-6, especially in the presence of other pro-inflammatory cytokines43, but also disrupt the barrier integrity of BECs via IL-6 mediated upregulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-139,44, corresponding well to the observation reported in the present study.

TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine primarily secreted by microglia following activation and can induce the activation of adjacent resting microglia or astrocytes, thereby resulting in an unregulated inflammatory CNS response45. TNF-α has therefore also been shown to play a vital role in neurodegeneration, as anti-TNF-α approaches can alleviate CNS disease symptoms45,46. Here we demonstrate that only three hours of LPS stimulation of MGCs induced a potent TNF-α secretion peaking six hours after LPS removal reaching a concentration around 4.7 ng/mL, which is comparable to the 3 ng/mL previously reported by Kong et al., after stimulating MGCs with 100 ng/mL LPS for six hours47. Interestingly, despite these MGCs being stimulated with the same concentration of LPS, the length of stimuli does not seem to increase the TNF-α secretion significantly. Likewise, Welser-Alves et al. have investigated the secretion of TNF-α from 1 µg/mL LPS-stimulated mouse MGCs, which is a ten times higher concentration of LPS than used in the present study. They exposed the cells for 48 hours and measured the TNF-α concentration to be around 1.9 ng/mL48, which is somewhat comparable to our concentration of around 2.9 ng/mL after 24 h. Combined these data suggest that increasing the concentration and incubation time of LPS do not increase the inflammatory response exerted by the MGCs.

KC/GRO also known as CXCL1 is a chemokine that plays a role in BBB disruption during neuroinflammation and previous studies have identified the main source of KC/GRO secretion to be from astrocytes3, suggesting that the initial effect of LPS on microglia, secondarily also activates the astrocytes. It has furthermore been reported that CXCL1 affects leukocyte recruitment to brain vessels during LPS-induced inflammation49, which corresponds well with an increased expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in mBECs co-cultured together with pre-stimulated MGCs in the aMGCs model, as a consequence of their increased secretion of KC/GRO. The secretion of KC/GRO peaked 6 h after the change of media, reaching a concentration of 5 ng/mL. Liu et al. have reported similar results after stimulating primary rat astrocytes with 1 µg/mL, where the concentration of CXCL1 peaks after three hours of stimulation with a concentration of around 6.5 ng/mL50.

Microglia are activated in response to LPS both in vitro and in vivo, initiating the immune response by secreting proinflammatory cytokines, which further induces astrogliosis37,51. Our immunolabeling confirms that only microglia of the MGC culture express TLR4, why only microglia cells can respond to LPS stimulation, corresponding well to previous observations that pure cultures of rat astrocytes do not respond to LPS, as these lack TLR4 receptor and downstream signaling components required for LPS activation51. Reactive microglia can also via e.g. TNF-α secretion induce the reactive A1 phenotype of astrocytes51. Other studies do however report on cytokine secretion after LPS stimulation of astrocytic cultures36,38,50, which could suggest that these astrocytic cultures have been contaminated with microglial cells that subsequently activate astrocytes to increase the secretion of various cytokines, as the same isolation procedure can be used to isolate both astrocytes and microglial cells16, or that the astrocytes might express a lower degree of TLR4 compared to microglial cells.

A majority of neurodegenerative diseases are accompanied by neuroinflammation, thus understanding the detrimental effect of neuroinflammation on the BBB is imperative. Despite LPS being an endotoxin found in the outer wall of gram-negative bacteria, it has been used for many years to induce both systemic- and neuroinflammation, as it promotes the release of various cytokines and chemokines through microglia activation8,52. The neuroinflammatory effect can also be mimicked by stimulating BECs with cytokines like INFgamma, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α21,53, however, this might be a simplification of the complicated nature of neuroinflammation. In vitro BBB models are useful tools for studying various properties of the BBB16, however existing models often study the direct effect of LPS on the BECs19,21,27,54–56, which can lead to apoptosis57. Co-culturing mBECs with pre-activated MGCs is, therefore, an alternative method for mimicking the effect of glial-mediated inflammation on BBB properties, without LPS having any direct effect on mBECs. Instead, BECs are affected by the cytokines secreted by pre-stimulated MGCs, corresponding well with the neuroinflammatory state in vivo. Hydrocortisone, anti-inflammatory by nature, was consistently included in the media in the experiments, as this is a necessity to induce and maintain a tight BBB58. This does, however, denote a possible limitation of the study as the omission of hydrocortisone theoretically might have exaggerated the effects of the MGCs leading to a more dramatic increase in BBB permeability.

Somewhat similar approaches of activating MGCs before co-culturing with mBECs have previously been described3,26. Shigemoto-Mogami et al. (2018) used a model of primary cells generated from rats to show that selectively isolated microglial cells activated with 1 µg/mL LPS for only one hour before transfer to the astrocytic culture in the abluminal compartment of an in vitro triple co-culture model results in decreased TEER values, higher permeability, and lower protein levels of ZO1, OCLN, and CLD53,26. Park et al. (2023) also took a different approach by using the immortalized endothelial cells bEnd.3 to establish a contact co-culture BBB model together with astrocytes, from which they established a proinflammatory response by exposing the model to activated microglial conditioned media obtained from an LPS (50 ng/mL) stimulated microglial cell line. Again a decreased BBB integrity was demonstrated through decreased TEER values and lower protein expression of ZO1, OCLN, and CLD526. In comparison with these studies, the current study attempted to take advantage of a more in vivo-like situation by pre-stimulating primary MGCs to allow the collective population of cells occurring in the vicinity of the BECs to exert their concerted action. No previous study has made a direct comparison between indirect and direct stimulation with LPS as presented here, why we nonetheless also using this more integrated model find that indirect stimulation with LPS exerts a stronger neuroinflammatory mBECs phenotype than direct stimulation with LPS, and that direct luminal or abluminal LPS stimulation likewise exert different effect on this neuroinflammatory phenotype.

Studies point towards decreased BBB integrity during inflammation8,9,19,21,55–57, underlining the effect of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from activated MGCs on the BEC phenotype. We found decreased integrity determined by TEER measurements, but no significant changes in the gene expression levels of the tight junction proteins zo1, ocln, and cld5. Compared to control mBECs, mBECs of the aMGC, luminal LPS, and abluminal LPS models, all showed similar decreases in TEER around 20–25%. mBECs of the aMGC model therefore show a similar effect on TEER as directly stimulating the mBECs with LPS. This suggests that the secretion of cytokines from the pre-activated MGCs and TLR4 activation via direct LPS stimulation of the mBECs decreases the BBB permeability through different pathways. Luminal LPS stimulation affects the mBECs through their expression of TLR4, while abluminal stimulation results in both TLR4 activation of mBECs and MGCs while co-culturing mBECs with pre-stimulated MGCs represent a response solely from the cytokine production. It has previously been reported that the addition of either TNF-α, IL-1β, or IL-6 can result in a significant reduction in TEER21,53. These cytokines are all secreted by the activated MGCs and may therefore be responsible for the affected barrier integrity, as seen in the abluminal LPS and aMGCs model. Despite the decreased BBB integrity seems to occur via different pathways, neither of them seems to be through decreased gene expression levels of Cld5, Ocln, or Tjp1, but rather through post-transcriptional changes resulting in decreased protein levels or functional changes of the tight junction organization3,19,26,27,55,57. This also correlates well with our observation that the mBECs of the aMGC model had an uneven and non-consistently expression of tight junction proteins revealing small gaps between adjacent cells, which could reflect a disrupted function of the TJ proteins, rather than a downregulation of gene expression. Several studies have observed similarly displaced alteration in the arrangement of the tight junction proteins ZO1, OCLN, and CLD555–57.

Two different controls were included in the study as changing the medium, especially in the luminal chamber can affect the TEER values. Likewise including washing steps during the medium change would also negatively affect the TEER values (unpublished observations). A theoretical confounder of this study could therefore be leftover LPS residing within the cell cultures after the replacement of the cell culture medium. However, the gene expression level of relevant cytokines slowly declines 6 h after removal of LPS indicating no continued stimulation with LPS. Furthermore, the concentration of potentially leftover LPS would probably be very low as a consequence of the medium change. Including two different control situations makes it difficult to compare luminal LPS and abluminal stimulations, however, the values for these controls were generally highly comparable.

Increased trafficking of leukocytes across the inflamed BBB is an early event in some neurodegenerative diseases, and it is known that the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are of great importance for this process30,31,59. The mBECs had an increased expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 especially in the mBECs of the aMGC model, supporting the findings of previous studies19,60. In normal physiological conditions, the mBECs express very low levels of adhesion molecules, increasing this expression significantly during inflammation. This corresponds highly with the observation made in the present study where mBECs of the aMGCs model also displayed a strong upregulation of both ICAM and VCAM at a protein level. Direct luminal LPS stimulation of the mBECs did not have a significant impact on the expression of Icam1, suggesting that this gene is regulated by the cytokines secreted from the LPS-stimulated MGCs such as KC/GRO, as mentioned previously, rather than through TLR4 activation of mBECs. The increased expression of cell adhesion molecules in the mBECs of the aMGCs model makes this model very suitable for further studies on leukocyte migration across the BBB.

The BBB transporters, Glut1, Tfr, and CD98hc were investigated to determine the relative gene expression upon direct and indirect LPS stimulation. The expression of Tfr did not seem to be affected by LPS or cytokine secretion from activated MGC. However, the relative gene expression of Glut1 showed a tendency towards decreased expression as an effect of direct luminal LPS. Alzheimer’s disease has been associated with decreased GLUT1 expression in brain endothelial cells, leading to BBB dysfunction61. In a recent study, we showed that CD98hc opposed to transferrin receptor 1 remains constant at the BBB when challenged by valproic acid62. In the current study, Slc3a2, however, presented a tendency towards increased expression, when stimulated abluminally with LPS, reaching a significant increase when stimulated with activated MGCs. This suggests that the secretion of cytokines from LPS-stimulated MGCs affects the gene expression of this potential BBB target, but mechanisms remain to be explained. If the finding of CD98hc being upregulated as a consequence of neuroinflammation can be verified on a protein level, and in vivo, it might increase the potential of this receptor as a target for BBB transfer of drugs to treat neurodegenerative diseases with inflammation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the stimulation of MGCs with LPS for three hours increased the expression of multiple pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Co-culturing mBECs with the pre-activated MGCs resembles a BBB model with inflammation where the sole influence of the secreted cytokines on the BBB can be studied, without the need to use direct LPS stimulation of mBECs. Comparable to direct LPS stimulation of mBECs, mBECs of the aMGCs model exhibited decreased barrier integrity, without a complete breakdown of the barrier, but rather an altered functional organization of the tight junction proteins. Furthermore, the mBECs of the aMGCs model increased the expression of cell adhesion molecules to a higher degree than when stimulated directly with LPS, making this model highly interesting for studies on leukocyte migration across the BBB during inflammation. mBECs of the aMGCs model therefore display a neuroinflammatory phenotype caused by glial activation making this model suitable for directly studying the effects of cytokine secretion on the molecular alterations occurring at the BBB during neuroinflammation.

Materials and methods

Isolation of mixed glia cells (MGCs)

Primary mouse MGCs were isolated from one to two-day-old C57BL/6 mice as previously described16,28. The Danish Experimental Animal Inspectorate under the Ministry of Food and Agriculture approved all handling of the mice (permission no.: 2016-15-0201-00979). The study was conducted according to relevant guidelines and reported as described by the ARRIVE guidelines63. In short, the mice brains were suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Cat. no. 31966, Thermo Scientific) and filtered through a 40 μm nylon strainer. Flasks precoated with poly-L-lysine (Cat. no. P6282, Sigma/Millicell Merck KGaA) were used to culture the MGCs. MGC medium consisting of DMEM mixed with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Cat. no. 10270, Thermo Scientific) and 10 µg/mL gentamicin sulfate (Cat. no. 17-518Z, Lonza Copenhagen) was added to the flasks and subsequently placed in a CO2 incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% atmospheric air at 37 °C, with a change of medium twice a week. After three weeks, the MGCs were either frozen in DMEM supplemented with 30% FCS and 7.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (Cat. no. D2650, Sigma/Millicell Merck KGaA) for later use, or transferred to 12-well plates precoated with poly-L-lysine. MGCs were additionally cultivated for two weeks before being stimulated with LPS or co-cultured with mouse BECs (mBECs).

LPS stimulation of MGCs

To investigate the response of the MGCs to LPS, cultures of MGCs were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS for three or 48 h. After three hours of incubation with LPS, the medium was replaced with MGC medium, and cells and medium were subsequently harvested after three, six, 24, and 48 h (Fig. 1A). Non-LPS-stimulated MGCs served as a control. The cells were lysed for gene expression analysis and the medium was analyzed with mesoscale multiplex analysis for cytokine profiling. To analyze the morphological changes of the MGCs and expression of the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) after LPS stimulation, the MGCs were seeded on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips and stimulated for three hours with LPS before the medium was replaced with MGC-medium without LPS. The MGCs were cultured for an additional six hours before being fixated with either paraformaldehyde or ice-cold − 20 °C 99.9% methanol for immunocytochemistry.

Meso scale discovery electrochemiluminescent assay

The cytokine levels in the media from LPS-stimulated MGCs and non-stimulated MGCs were measured using MesoScale electrochemiluminescence with the V-PLEX mouse Proinflammatory Panel 1 (IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, KC/GRO (also known as CXCL1), and TNF-α (Cat. no K15012). Media from three control and three LPS-stimulated MGC cultures from each time point (three, six, and 24 h), were pooled and run in duplicates. To determine the protein concentration of each cytokine, a SECTOR Imager 6000 (MSD Mesoscale Discovery, USA) plate reader was applied. Samples were analyzed in duplicates and 25 µl was loaded in each well. Data analysis was carried out using MSD Discovery Workbench software.

Isolation of mouse brain capillary endothelial cells (mBECs)

Primary cultures of mBECs were isolated from the brains of eight-week-old C57BL/6 female mice as described previously16,28. All procedures and handling of mice were approved by the Danish National Council for Animal Welfare (Permit number: 2016-15-0201-00979). Mice used in the experiment were purchased from Javier Labs. All animals had unrestricted access to food and water and were housed under stable temperature conditions between 20 and 22 °C, humidity 40–60%, and a light-dark cycle of 12 h. The mice were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane and a total number of 90 mice were used for these experiments equal to six isolations of primary mBECs. The brains were isolated, and the meninges and visible white matter were removed. The gray matter was cut into small pieces in ice-cold DMEM-F12 (Cat. no. 31331, Thermo Scientific). The tissue was digested in a suspension of DMEM-F12, containing collagenase type II (1 mg/ml) (Cat. No. C6885, Sigma/Millicell Merck) and DNase I (20 µg/mL) (Cat. No. D4513, Sigma/Millicell Merck) and placed on an incubating mini shaker at 37 °C for 75 min. The homogenate was mixed and centrifuged in 20% bovine serum albumin (Cat. No. EQBAH62, Europa Bioproducts) in DMEM-F12 to separate the cells. The microvessels present in the cell pellet were further treated with DMEM-F12 supplemented with collagenase/dispase (1 mg/ml) and DNase I (7.5 mg/µl) in a mini shaker (200 rpm) at 37 °C for 50 min. A 33% Percoll gradient (Cat. No. P1644, Sigma/Millicell Merck) was used to separate and isolate the microvessels. The isolated microvessels were cultured in mBEC medium consisting of DMEM-F12 supplemented with 10% plasma-derived bovine serum (Cat. No. 60-00-810, First Link), 0.1 mg/mL Insulin-Transferrin-Sodium Selenite Supplement (Cat. No.11074547001, Sigma/Millicell Merck), 10 µg/mL gentamicin sulfate, and freshly added 1 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Cat. No. 100-18B, PeproTech Nordic), in flasks precoated with collagen IV (Cat. no. C5533, Sigma/Millicell Merck) and fibronectin (Cat. no. F1141, Sigma/Millicell Merck). For the first four days of culturing, the medium was supplemented with 4 µg/ml Puromycin, to minimize pericyte contamination64. The cells were cultured in a CO2 incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% atmospheric air at 37 °C. Four days after isolation of mBECs, they were either frozen in endothelial media, supplemented with 20% FSC (a total concentration of 30%) and 7.5% dimethyl sulfoxide, or directly passaged on to 12 well-hanging culture inserts for the establishment of a co-culture BBB models with MGCs.

Establishment of BBB in vitro models

mBECs were seeded in hanging culture inserts pre-coated twice with 1 mg/mL collagen IV and 1 mg/mL fibronectin diluted in Milli-Q water at a density of approximately 100,000 cells/cm2. To obtain a confluent monolayer, the mBECs s were placed in a CO2 incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% O2 at 37 °C for approximately 24–48 h to obtain confluent monolayers, before co-culturing with MGCs. To further induce tight junction formation the mBEC, medium in the luminal chamber was supplemented with 550 nM hydrocortisone (Cat. no. H4001, Sigma/Millicell Merck), 250 mM CTP-cAMP (Cat. no. C3912, Sigma/Millicell Merck), and 17,5 mM RO 20-1724 (Cat. no. B8279, Sigma/Millicell Merck), and the medium in the abluminal chamber contained 1:1 mixture of mBECs medium and MGCs medium, supplemented with 550 nM hydrocortisone.

Establishment of inflammatory in vitro BBB models

We created three different scenarios of LPS stimulation to create in vitro BBB models with inflammation (Fig. 2). Two models were designed to investigate the direct effect of LPS on the seeded mBEC monolayer, while the third model was designed to investigate the indirect effect of LPS on the mBECs, by pre-stimulating MGCs with LPS, thereby activating these to increase their production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The third model therefore investigates the effect of a range of cytokines secreted by MGCs on the mBECs. The models are referred to as luminal LPS, abluminal LPS, and activated MGCs (aMGCs), respectively. On day one, the mBECs in all three models were co-cultured with non-stimulated MGCs and tight junction induced. The next day (day two), the three models were created by using 100 ng/mL LPS (serotype 055:B5, Cat. No L2880, Sigma/Millicell Merck).

The luminal LPS model was established by adding LPS to the luminal chamber for three hours before the medium was replaced with mBECs medium without LPS. The mBECs were incubated for an additional six hours before the TEER was measured and the mBECs lysed for gene expression analysis.

The abluminal LPS model was established by adding LPS to the abluminal chamber for three hours before the medium was replaced with mBECs medium without LPS and the mBECs were incubated for an additional six hours before TEER was measured and the mBECs lysed for gene expression analysis.

The aMGC model was established by stimulating a culture of MGCs with LPS for three hours before the medium was replaced and the aMGCs were co-cultured with induced mBECs cultured on hanging culture inserts. The mBECs were co-cultured with the aMGCs for either six hours before TEER was measured and the mBECs lysed for gene expression analysis or for 24 h before TEER was measured and the mBECs were fixated for immunocytochemistry.

Non-stimulated mBECs co-cultured with MGCs with a change of the luminal medium served as the control for the luminal LPS model, (luminal control), and non-stimulated mBECs co-cultured with MGCs with a change of the abluminal medium served as the control for the abluminal LPS and aMGC models (abluminal control) (Fig. 2). Two different controls were included as changing the medium, especially in the luminal chamber can influence the TEER values. For the same reason, no washing steps after LPS removal were included as this would also negatively influence the TEER values.

TEER measurements

The integrity of mBECs was assessed by TEER measurements using a Millicell ERS-2 epithelial volt-ohm Meter and STX01 Chopstick Electrodes (Merck Millipore, Hellerup, Denmark, DK). The measured TEER of the mBECs was subtracted from the value of an empty collagen IV/fibronectin-coated hanging culture insert containing only medium. The differences between TEER measured in the co-culture and the TEER of an empty hanging insert were multiplied by the area of the culture inserts. TEER was measured daily and before and after experiments. The calculated TEER values are presented as mean Ω × cm2 ± Standard Deviation (SD).

Apparent permeability of 3 H-D-Mannitol

The apparent permeability of 3 H-D-Mannitol was investigated in the aMGC model after 24 h to further investigate the influence of the aMGCs on the mBECs barrier integrity. The passive permeability across the mBEC monolayer was measured by adding 1 µCi/ml 3 H-D-Mannitol (Specific activity 15.9 Ci/mol) to the luminal chamber of the filter insert16. mBECs cultured with non-stimulated MGCs served as control. TEER was measured before the addition of 3 H-D-Mannitol, and the cells were incubated for two hours at 37 ºC under mild agitation. During the incubation period, 100 µl samples were taken from the luminal chamber at 0 h and 100 µl samples were taken from the abluminal chamber at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min and replaced with the same volume of fresh media. Samples were mixed with Ultima Gold™ liquid scintillation cocktail and counted in a Hidex 300SL liquid scintillation counter (Kem-En-Rec Nordic, Taastrup, Denmark). The total amount of millimoles transported in each well was plotted against time and the flux at steady state was calculated as the slope of the straight line divided by the area of the filter insert. The Papp was then calculated by dividing the flux at a steady state with the initial concentration in the upper compartment. The calculated Papp data were plotted against the TEER value for each filter insert or collectively plotted regardless of TEER.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed on mBECs from the aMGC model and non-stimulated mBEC controls, LPS-stimulated MGCs, and non-stimulated MGCs. The cells were washed twice in 0.1 M PBS, fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, and subsequently washed twice in 0.1 M PBS. Non-specific binding sites were inhibited by adding a blocking buffer containing 3% BSA, and 0.3% Triton-X-100 diluted in 0.1 M PBS for 30 min to avoid unspecific binding of antibodies. All incubations were performed at room temperature under mild agitation. mBECs were incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-CLD5 (cat. no SAB4502981, Sigma/Millicell Merck), rabbit anti-OCLN (cat. no. ABT 146, Sigma/Millicell Merck), and rabbit anti-ZO-1 (ZO-1; cat. no. 61-7300, Zymed_Lab/Invitrogen), rat anti-VCAM (cat. no. AB19569, Abcam), and hamster anti-ICAM-1 (cat. no. MA5405, ThermoScientific Life Technology) all diluted 1:200 in incubation buffer. MGCs were incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-GFAP (cat. no. Z0334, Dako) and rat anti-CD11B (cat. no. MCA74, Serotec), and mouse anti-TLR4 (Cat.no. sc-293072, Santa Cruz) all diluted 1:250 in incubation buffer. For immunolabelling of TLR4, the MGCs were fixed with ice-cold − 20 °C 99.9% methanol for 10 min instead of with paraformaldehyde. After one hour of incubation with the primary antibodies, the cells were washed twice in washing buffer (blocking buffer diluted 1:50 in PBS) to remove unbound primary antibodies.

Secondary donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Flour 594 (cat. no. A21207, Invitrogen), goat anti-mouse Alexa Flour 594 (cat. no. 1037286, Invitrogen), donkey anti-mouse Alexa Flour 488 (cat. no. 41225 A, Invitrogen), goat anti-rabbit Alexa Flour 488 (cat. no. A11034, Invitrogen), goat anti-rat Alexa Flour 594 (cat. no. A11007, Invitrogen), and goat-anti-hamster Alexa Flour 488 (cat. no. A21110, Invitrogen) antibodies were diluted 1:200 in incubation buffer and incubated with the cells for one hour at room temperature. The secondary antibodies were removed, and cells were subsequently washed twice in PBS. For staining of the nuclei, the cells were incubated for 5 min with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (1 mg/ml; cat. no. D9542) diluted 1:500 in PBS. Afterward, cells were mounted on object slides using fluorescent mounting media (cat. no. S3023, DAKO). For examination of the cells, an AxioObserver Z1 fluorescence microscope equipped with an Apotome and Axiocam MR camera or a LSM900 confocal microscope (Zeiss) was used. Using ImageJ software, the included immunocytochemistry images were adjusted for brightness and contrast.

Reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNA isolation

RNA was isolated from mBECs (one sample corresponded to 3 hanging culture inserts) from the three inflammatory in vitro models together with their respective controls. RNA was additionally isolated from the LPS-stimulated MGCs and non-stimulated MGCs (one sample corresponds to two wells in a 12-well plate) at various time points. The Purification of RNA was conducted using the Thermo Scientific GeneJET purification kit (cat. no. K0731, Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, the cells were lysed with lysis buffer supplemented with 14.3 M beta-mercaptoethanol, and 96% ethanol was added to the lysed samples. Subsequently, the cell lysate was added to the purification columns followed by multiple washing steps using the two washing buffers included in the kit, before eluting the RNA with nuclease-free water. To determine the concentration and purity of the RNA samples, a DS-11 FX Spectrophotometer (DeNovix, USA) was utilized.

cDNA synthesis

Before synthesizing complementary DNA (cDNA), genomic DNA was removed from the purified RNA samples. In RNase-free tubes, DEPC-treated water, 10X reaction buffer with MgCl2, and DNase I enzyme (cat. no. K0731, Thermo Scientific) were mixed with 300 ng RNA from each sample. The samples were incubated in a T100TM thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (cat. no. K0731, Thermo Scientific) was added to each sample before another incubation step for 10 min at 65 °C. For synthesizing cDNA from the DNase-treated RNA samples, Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Cat. no. K1651, Thermo Scientific) was used. In RNase-free tubes, 250 ng RNA (MGCs) or 60–150 ng (mBECs) DNase-treated RNA from each sample was mixed with oligo (dT)18 primers, random hexamer primers, 10 mM dNTP mix, 5X RT buffer, and Maxima H Minus Enzyme Mix, and nuclease-free water to reach a final volume of 20 µl. The samples were then incubated for 10 min at 25 °C, 15 min at 50 °C, and 5 min at 85 °C, in the thermal cycler.

qPCR

The synthesized cDNA samples from MGCs were analyzed by qPCR to measure the relative gene expression of Il6, Il1β, Tnfα, while cDNA samples from mBECs were analyzed for relative gene expression of Cldn5, Ocln, and Tjp1 (also known as ZO1). Actin beta (Actb) and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (Hprt1) were used as reference genes (Table 1). Before the qPCR analysis, the DNase-treated samples were tested for DNA contamination, by analyzing them as reverse transcriptase minus (RT-) negative controls, and standard curves with 10 x serial dilutions were made to validate primers. Primer efficiencies of 92–108% were accepted and set to 100%. Samples were analyzed in triplicates, with a final volume of 10 µl consisting of 2 ng cDNA mixed with a master mix containing Maxima™ SYBR Green and forward- and reverse primer. The samples were analyzed using the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a thermal profile of 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min, and a melt curve cycle of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 95 °C for 15 s.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in RT-qPCR reactions.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Actb | CTGTCGAGTCGCGTCCACC | TCGTCATCCATGGCGAACTGG |

| Hprt1 | GTTGGATACAGGCCAGACTTTGTTG | GATTCAACTTGCGCTCATCTTAGGC |

| Il6 | ACAGAAGGAGTGGCTAAGGACCA | TCTGACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCA |

| Il1β | TGCCACCTTTTGACAGTGATGAGAA | TGTTGATGTGCTGCTGCGAGA |

| Tnfα | CTGGCCAACGGCATGGATCT | AGCAAATCGGCTGACGGTGT |

| Cldn5 | AGGATGGGTGGGCTTGATCCT | GTACTCTGCACCACGCACGA |

| Ocln | GATTCCGGCCGCCAAGGTT | TGCCCAGGATAGCGCTGACT |

| Tjp1 | GAGACGCCCGAGGGTGTAGG | TGGGACAAAAGTCCGGGAAGC |

For mBECs relative gene expression of Glut1, Tfr, Slc3a2, also known as CD98hc), Icam1, and Vcam1, and the reference gene Hprt1, probe-based qPCR was utilized. In short, 2 ng cDNA was mixed with a master mix containing TaqMan Multiplex MasterMix (cat. no. 4484262) and 1 µl of Taqman Probes for Hprt1 (cat. no. 4448490) in combination with 1 µl of either, Glut1 (cat. no. 4331182), Tfr (cat. no. 4351370), Slc3a2 (cat. no. 4331182), Icam1 (cat. no. 4331182), or Vcam1 (cat. no. 4331182) reaching a final volume of 20 µl. Samples were analyzed in the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with a thermal profile of 95 °C for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 1 s and 60 °C for 20 s.

The relative gene expression ratio of Il6, Il1β, Tnfα, Cldn5, Ocln, and Tjp1 were calculated according to the method described by Pfaffl65 normalizing the data to the geometric mean of the expression of the two reference genes Actb and Hprt1 and using the non-LPS-stimulated cells as the reference sample. The relative gene expression ratio of Glut1, Tfr, Slc3a2, Icam1, and Vcam1 was calculated using the delta-delta CT method using the non-LPS-stimulated cells as the reference sample.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as mean ± Standard deviation (SD), and all statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 10.2.3). All experiments were repeated several times, using cells from different isolations, and each n-value refers to each experiment unless otherwise stated in the figure legend. No statistical tests were performed to determine sample size. All statistical analyses were two-sided, and a p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data sets were analyzed for outliers using the ROUT test and for equal variances using either an F-test (two groups) or a Brown-Forsynthe test (three groups). When equal variances were met, datasets were analyzed using an unpaired T-test (two groups) or an ordinary One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. When equal variances were not met, which was only the case for a few data sets containing two groups, these were analyzed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney t-test. Data sets containing more than two variables were analyzed using a Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or an Uncorrected Fisher’s LSD. The details of the specific statistical analysis used are reported in figure legends.

Acknowledgements

We thank Merete Fredsgaard and Hanne Krone Nielsen, Aalborg University, Denmark, for their excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- Actb

Actin beta

- aMGCs

Activated mixed glial cells

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- BECs

Brain endothelial cells

- CD11b

Cluster of differentiation 11b

- CD98hc

Cluster of differentiation 98 heavy chain

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CLD5

Claudin 5

- DAMPs

Damage-associated molecular pattern

- FCS

Fetal calf serum

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- Glut1

Glucose transporter 1

- Hprt1

Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1

- ICAM-1

Intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- IL-1β

Interleukin 1β

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- INFγ

Interferon-γ

- KC/GRO

Keratinocyte chemoattractant/growth-regulated oncogene

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- mBECs

Mouse brain endothelial cells

- MGCs

Mixed glial cells

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- NeuN

Neuronal nuclei antigen

- OCLN

Occludin

- PAMPs

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- Papp

Apparent permeability

- TEER

Trans-endothelial electrical resistance

- TFR

Transferrin receptor

- Tjp1

Tight junction protein 1

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factorα

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- VCAM-1

Vascular cell adhesion protein 1

- ZO-1

Zonula occludens

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SSH, LGR, MST, Funding acquisition: AB, MST, TM, SSH, Investigation: AB, SSH, YAM, MBF, JNHJ, HH, SED, FP, LGR, KL, MST, Supervision: AB, LGR, MST, TM, Visualization: AB, SSH, MST, Writing – original draft: AB, SSH, TM, MST, Writing – review and editing: AB, SSH, YAM, MBF, JNHJ, HH, SED, FP, LGR, KL, TM, MST.

Funding

The present study has been supported by the Danish Multiple Sclerosis Society (Grant no. R588-A40233 to T Moos), the Lundbeck Foundation Research Initiative on Brain Barriers and Drug Delivery (Grant no. R155-2013-14113 to T. Moos), Svend Andersen Fonden and Fonden for Lægevidenskabens Fremme.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Datasets used and analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Annette Burkhart, Steinunn Sara Helgudóttir, Torben Moos and Maj Schneider Thomsen.

References

- 1.Hou, Y. et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol.15, 565–581 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schain, M. & Kreisl, W. C. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders—A review. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep.17, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Shigemoto-Mogami, Y., Hoshikawa, K. & Sato, K. Activated microglia disrupt the blood-brain barrier and induce chemokines and cytokines in a rat in vitro model. Front. Cell. Neurosci.12, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Brandl, S. & Reindl, M. Blood–brain barrier breakdown in Neuroinflammation: Current in Vitro models. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Takata, F., Nakagawa, S., Matsumoto, J. & Dohgu, S. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction amplifies the development of neuroinflammation: Understanding of cellular events in brain microvascular endothelial cells for prevention and treatment of BBB dysfunction. Front. Cell. Neurosci.15, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Abbott, N. J., Patabendige, A. A. K., Dolman, D. E. M., Yusof, S. R. & Begley, D. J. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis.37, 13–25 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sofroniew, M. V. Astrocyte reactivity: Subtypes, states, and functions in CNS innate immunity. Trends Immunol.41, 758–770 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon, H. S. & Koh, S. H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: The roles of microglia and astrocytes. Translational Neurodegeneration9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Zhao, Y. et al. Factors influencing the blood-brain barrier permeability. Brain Res.1788, (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Skrzypczak-Wiercioch, A. & Sałat, K. Lipopolysaccharide-induced model of neuroinflammation: Mechanisms of action, research application and future directions for its use. Molecules27, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wang, Y. et al. Interleukin-1β induces blood-brain barrier disruption by downregulating sonic hedgehog in astrocytes. PLoS One9, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Rochfort, K. D., Collins, L. E., McLoughlin, A. & Cummins, P. M. Tumour necrosis factor-α-mediated disruption of cerebrovascular endothelial barrier integrity in vitro involves the production of proinflammatory interleukin-6. J. Neurochem.136, 564–572 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochfort, K. D., Collins, L. E., Murphy, R. P. & Cummins, P. M. Downregulation of blood-brain barrier phenotype by proinflammatory cytokines involves NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS generation: Consequences for interendothelial adherens and tight junctions. PLoS One9, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Lécuyer, M. A., Kebir, H. & Prat, A. Glial influences on BBB functions and molecular players in immune cell trafficking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis.1862, 472–482 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galea, I. The blood–brain barrier in systemic infection and inflammation. Cell. Mol. Immunol.18, 2489–2501 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomsen, M. S. et al. The blood-brain barrier studied in vitro across species. PLoS One16, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Gaillard, P. J., De Boer, A. G. & Breimer, D. D. Pharmacological investigations on lipopolysaccharide-induced permeability changes in the blood-brain barrier in vitro. Microvasc Res.65, 24–31 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhen, H. et al. Wip1 regulates blood-brain barrier function and neuro-inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide via the sonic hedgehog signaling signaling pathway. Mol. Immunol.93, 31–37 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haileselassie, B. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction mediated through dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) propagates impairment in blood brain barrier in septic encephalopathy. J. Neuroinflammation17, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.De Vries, H. E. et al. Effect of endotoxin on permeability of bovine cerebral endothelial cell layers in vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.277, 1418–1423 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poetsch, V., Neuhaus, W. & Noe, C. R. Serum-derived immunoglobulins neutralize adverse effects of amyloid-β peptide on the integrity of a blood-brain barrier in vitro model. J. Alzheimer’s Dis.21, 303–314 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kielian, T. Toll-like receptors in central nervous system glial inflammation and homeostasis. J. Neurosci. Res.83, 711–730 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson, J. K. & Miller, S. D. Microglia initiate central nervous system innate and adaptive immune responses through multiple TLRs. J. Immunol.173, 3916–3924 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papageorgiou, I. E. et al. TLR4-activated microglia require IFN-γ to induce severe neuronal dysfunction and death in situ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.113, 212–217 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Smyth, L. C. D. et al. Unique and shared inflammatory profiles of human brain endothelia and pericytes. J. Neuroinflammation15, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Park, J. S. et al. Establishing co-culture blood–brain barrier models for different neurodegeneration conditions to understand its effect on BBB integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Alkabie, S. et al. SPARC expression by cerebral microvascular endothelial cells in vitro and its influence on blood-brain barrier properties. J. Neuroinflammation13, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Thomsen, M. S., Birkelund, S., Burkhart, A., Stensballe, A. & Moos, T. Synthesis and deposition of basement membrane proteins by primary brain capillary endothelial cells in a murine model of the blood-brain barrier. J. Neurochem.140, 741–754 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaillard, P. J. & de Boer, A. G. Relationship between permeability status of the blood-brain barrier and in vitro permeability coefficient of a drug. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.12, 95–102 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopes Pinheiro, M. A. et al. Immune cell trafficking across the barriers of the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis and stroke. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1862, 461–471 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abadier, M. et al. Cell surface levels of endothelial ICAM-1 influence the transcellular or paracellular T-cell diapedesis across the blood-brain barrier. Eur. J. Immunol.45, 1043–1058 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varatharaj, A. & Galea, I. The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun.60, 1–12 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bö, L. et al. Distribution of immunoglobulin superfamily members ICAM-1, -2, -3, and the β2 integrin LFA-1 in multiple sclerosis lesions. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol.55, 1060–1072 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnsen, K. B., Burkhart, A., Thomsen, L. B., Andresen, T. L. & Moos, T. Targeting the transferrin receptor for brain drug delivery. Prog Neurobiol.181, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Chew, K. S. et al. CD98hc is a target for brain delivery of biotherapeutics. Nat. Commun.14, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Li, X. et al. KSRP: A checkpoint for inflammatory cytokine production in astrocytes. Glia60, 1773–1784 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He, Y., Taylor, N., Yao, X. & Bhattacharya, A. Mouse primary microglia respond differently to LPS and poly(I:C) in vitro. Sci. Rep.11, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Beurel, E. & Jope, R. S. Lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-6 production is controlled by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and STAT3 in the brain. J. Neuroinflammation6, (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Rothaug, M., Becker-Pauly, C. & Rose-John, S. The role of interleukin-6 signaling in nervous tissue. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell. Res.1863, 1218–1227 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samoilova, E. B., Horton, J. L., Hilliard, B., Liu, T. S. T. & Chen, Y. IL-6-Deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: Roles of IL-6 in the activation and differentiation of autoreactive T cells. J. Immunol.161, 6480–6486 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West, P. K., Viengkhou, B., Campbell, I. L. & Hofer, M. J. Microglia responses to interleukin-6 and type I interferons in neuroinflammatory disease. Glia67, 1821–1841 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gruol, D. L. & Nelson, T. E. Physiological and pathological roles of interleukin-6 in the central nervous system. Mol. Neurobiol.15, 307–339 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Wagoner, N. J., Oh, J. W., Repovic, P. & Benveniste, E. N. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) production by astrocytes: Autocrine regulation by IL-6 and the soluble IL-6 receptor. J. Neurosci.19, 5236–5244 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eugster, H., Pietro, Frei, K., Kopf, M., Lassmann, H. & Fontana, A. IL-6-deficient mice resist myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur. J. Immunol.28, 2178–2187 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frankola, A., Greig, K. H., Luo, N., Tweedie, D. & W. & Targeting TNF-Alpha to elucidate and ameliorate neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurol. Disord - Drug Targets10, 391–403 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang, R. et al. Blood-brain barrier penetrating biologic TNF-α inhibitor for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Pharm.14, 2340–2349 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kong, L. Y., Lai, C., Wilson, B. C., Simpson, J. N. & Hong, J. S. Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors decrease lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory cytokine production in mixed glia, microglia-enriched or astrocyte-enriched cultures. Neurochem. Int.30, 491–497 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welser-Alves, J. V. & Milner, R. Microglia are the major source of TNF-α and TGF-β1 in postnatal glial cultures; regulation by cytokines, lipopolysaccharide, and vitronectin. Neurochem. Int.63, 47–53 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, F. et al. CXCR2 is essential for cerebral endothelial activation and leukocyte recruitment during neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation12, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Liu, S. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen alleviates the inflammatory response induced by LPS through inhibition of NF-κB/MAPKs-CCL2/CXCL1 signaling pathway in cultured astrocytes. Inflammation41, 2003–2011 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liddelow, S. A. et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature541, 481–487 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cunningham, C. Microglia and neurodegeneration: The role of systemic inflammation. Glia61, 71–90 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Vries, H. E. et al. The influence of cytokines on the integrity of the blood-brain barrier in vitro. J. Neuroimmunol.64, 37–43 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hultman, K., Björklund, U., Hansson, E. & Jern, C. Potentiating effect of endothelial cells on astrocytic plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 gene expression in an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. Neuroscience166, 408–415 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veszelka, S. et al. Pentosan polysulfate protects brain endothelial cells against bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced damages. Neurochem. Int.50, 219–228 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Banks, W. A. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced blood-brain barrier disruption: Roles of cyclooxygenase, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and elements of the neurovascular unit. J. Neuroinflammation12, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Cardoso, F. L. et al. Exposure to lipopolysaccharide and/or unconjugated bilirubin impair the integrity and function of brain microvascular endothelial cells. PLoS One7, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Hoheisel, D. et al. Hydrocortisone reinforces the blood-brain barrier properties in a serum free cell culture system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.244, 312–316 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong, D., Prameya, R. & Dorovini-Zis, K. In vitro adhesion and migration of T lymphocytes across monolayers of human brain microvessel endothelial cells: Regulation by ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E- selectin and PECAM-1. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol.58, 138–152 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coisne, C. et al. Differential expression of selectins by mouse brain capillary endothelial cells in vitro in response to distinct inflammatory stimuli. Neurosci. Lett.392, 216–220 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liebner, S. et al. Functional morphology of the blood–brain barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol.135, 311–336 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Helgudóttir, S. S. et al. Upregulation of transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) but not glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) or CD98hc at the blood–brain barrier in response to valproic acid. Cells13, (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Percie du Sert, N. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Physiol.598, 3793–3801 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Perrière, N. et al. Puromycin-based purification of rat brain capillary endothelial cell cultures. Effect on the expression of blood-brain barrier-specific properties. J. Neurochem.93, 279–289 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pfaffl, M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res.29, e45 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Datasets used and analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.