Abstract

Background/Aim

Catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI) are frequently life-threatening. Several factors have been reported to be related to CRBSI development; however, the factors associated with CRBSI mortality are unclear as they have rarely been studied. This study investigated the factors associated with mortality in patients with CRBSI, specifically focusing on nutritional factors.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective, multicenter study included in-patients with acute conditions and convalescent patients diagnosed with a CRBSI between January 2019 and December 2021 at 33 hospitals (23 general hospitals, two mixed-care hospitals, and eight convalescent hospitals). The primary outcome was death. Unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with mortality.

Results

A total of 453 patients with CRBSI were enrolled. The causes of death were analyzed for 382 (84.3%) who survived CRBSI and 71 (15.7%) who died. Multivariable analysis revealed that Candida detected in blood culture [adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=2.72, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.15-6.41; p=0.025)], CRBSI onset within 30 days of catheter insertion (aOR=2.28, 95% CI=1.27-4.09; p=0.005), concurrent infection (aOR=2.07, 95% CI=1.19-3.60; p=0.009), low serum albumin level (aOR=1.64, 95% CI=1.02-2.63; p=0.044), and elevated C-reactive protein level (aOR=1.05, 95% CI=1.01-1.10; p=0.028) were risk factors for mortality, whereas the use of a peripherally inserted central catheter was associated with a reduced risk of CRBSI mortality (aOR=0.30, 95% CI=0.13-0.69; p=0.004).

Conclusion

Enhanced monitoring of factors, such as candida detected in blood culture, CRBSI onset within 30 days of catheter insertion, concurrent infection, low serum albumin level, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level and the use of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC), is crucial for mitigating CRBSI severity and risk of death.

Keywords: Catheter-related bloodstream infection, mortality, albumin, C-reactive protein, Candida

Catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs) are the leading cause of healthcare-associated bloodstream infections. CRBSIs are classified into central line-associated and peripheral line-associated bloodstream infections. Central line-associated bloodstream infections are associated with extended hospitalization, increased mortality, and increased healthcare costs (1,2). In contrast, peripheral line-associated bloodstream infections are complications that result in severe bacteremia and potential fatality (3). Consequently, CRBSI is a potentially fatal complication, and factors that can reduce the risk of its onset and mortality should be considered.

Previous studies have identified risk factors for CRBSI development, including the catheter insertion site, multi-lumen catheters, catheterization duration, poor hand hygiene, and older age (4-9). Despite numerous reports on the risk factors for CRBSI onset, only a few have investigated the factors associated with mortality in patients with CRBSI (10-13). Factors associated with CRBSI onset are classified into exogenous factors (such as bacterial invasion from outside the body) and patient-side internal factors (such as concurrent infection, reduced immunity, and bacterial translocation from long-term antibiotic use) (14,15). However, as far as we are aware, no studies have examined the factors associated with mortality from the perspective of the patient, especially the nutritional aspect.

In this study, we aimed to conduct a survey to identify the factors associated with mortality in in-patients and homebound patients with CRBSI across multiple centers. We focused on the venous access devices used before CRBSI onset, with a specific emphasis on nutritional management.

Patients and Methods

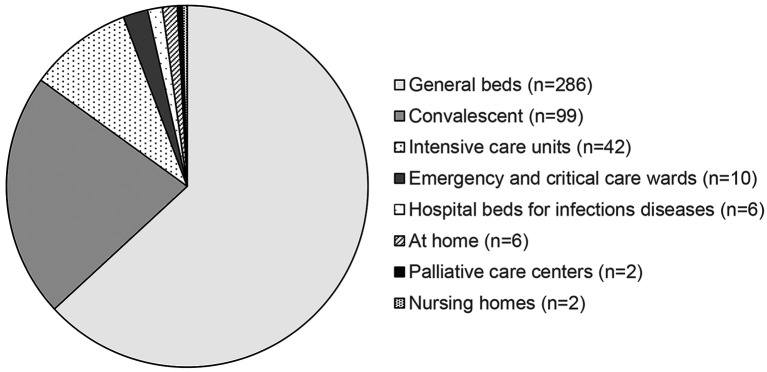

Study design and population. This retrospective observational study was conducted at 33 participating centers (23 general hospitals, two mixed-care hospitals, and eight convalescent hospitals). In-patients with acute conditions and convalescent patients diagnosed with CRBSI between January 2019 and December 2021 were included in the analysis. Of the 456 reported patients, the cohort for analysis included the 453 with documented survival outcomes, of whom the majority (n=286, 63.1%) were patients in general wards (Figure 1). All patients with intravenous catheters, diagnosed with CRBSI during the study period were included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Bed classifiably at the time of onset of catheter-related bloodstream infection.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujita Health University (HM22-418). The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design. We used an opt-out method based on Ethics Committee approval and national ethical guidelines, and patients were able to obtain information and instructions about the study on the institution’s website.

Definition of CRBSI. The definition of CRBSI adhered to that of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (9). CRBSI was diagnosed in patients with indwelling vascular catheters exhibiting bacteremia (i.e., at least one blood culture obtained from a peripheral vein was positive), clinical signs of infection (such as fever, chills, and hypotension), and no apparent source of bloodstream infection other than the catheter. Furthermore, a CRBSI diagnosis had to meet one of the following criteria: i) catheter and peripheral blood cultures positive for the same microorganism; ii) simultaneous positive catheter and peripheral blood culture results; and iii) positive blood cultures from the catheter and peripheral blood with a time difference of at least 2 hours.

Data collection. The collected variables encompassed age, sex, body mass index, catheter details (type, tip type, lumen, and insertion site), energy sufficiency rate, insulin/oral antidiabetic drug use, bacteria detected via blood culture, time from catheter insertion to CRBSI onset, presence of other infections, duration of antibiotic treatment, laboratory values [glucose, serum albumin, and total cholesterol levels; white blood cell and total lymphocyte counts; and C-reactive protein (CRP) level], nutritional indicators [prognostic nutritional index (PNI) and controlling nutritional status (CONUT)], and survival outcomes.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) as a graphical user interface for R version 4.2.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). EZR, a modified version of R Commander (version 1.61), is designed to incorporate commonly used statistical functions in biostatistics (16). Continuous variables are expressed as medians and ranges, and categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and proportions. Single variable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the risk factors for CRBSI. In the single variable analysis, variables reported as “unknown” were treated as missing values. In multivariable analysis, “missing” and “unknown” data were imputed using multiple imputations. Twenty complete datasets were generated using multivariate imputation by chained equations, assuming that the missing data occurred at random. Through 20 iterations, the missing or unknown values were replaced with a set of substituted plausible values (17). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Two-sided values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics. The baseline characteristics of the 453 patients in the analysis cohort (full cohort=382 surviving patients and 71 deceased) are presented in Table I and Table II. In the full cohort, the median age was 79.0 (range=4.0-101.0) years, with 267 (58.9%) male and 186 (41.1%) female patients. The most common catheter types, tip types, lumens, and insertion sites were central venous catheters (278 patients, 61.4%), closed-tips (184 patients, 40.6%), single lumens (236 patients, 52.1%), and the internal jugular vein (140 patients, 30.9%), respectively. Insulin or oral antidiabetic drugs were administered to 135 patients (29.8%).

Table I. Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients in this study.

BMI: Body mass index; CRP: C-reactive protein; PNI: prognostic nutritional index; CONUT: controlling nutritional status; WBC: white blood cells.

Table II. Catheter- and infection-related characteristics of patients with catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI).

CoNS: Coagulase-negative staphylococci; CRBSI: catheter-related bloodstream infection; CVC: central venous catheter; CV port: totally implantable central venous access port; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PICC: peripherally inserted central venous catheter; PVC: peripheral venous catheter.

The bacteria detected in blood cultures were predominantly coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) and Staphylococcus [excluding CoNS and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)] (90 patients, 19.9% each) and Candida (67 patients, 14.8%). Patients with several detected bacterial types were grouped regardless of the bacteria type detected (five patients, 1.1%). Over half of the patients experienced CRBSI within 30 days of catheter insertion (8-29 days: 187 patients, 41.3%; ≤7 days: 50 patients, 11.0%). The laboratory test results showed that many patients had a low serum albumin level (median=2.5 g/dl, range=0.6-4.0), low lymphocyte counts (median=915 cells/μl, range=21-5813 cells/μl), and high CRP level (median=3.2 mg/l, range=0.0-30.5 mg/l). Patients had low PNI values (median=29.2, range=9.5-63.1) and high CONUT values (median=8.0, range=1.0-12.0); however, many data were missing.

Factors associated with CRBSI mortality in the unadjusted (single variable) logistic regression analysis. All variables investigated in this study were considered as potential contributors to mortality. However, we initially conducted single-variable logistic regression analysis because of the large number of variables relative to the number of events (71 deaths) (Table III and Table IV). Factors associated with mortality included detectable Candida (OR=2.72, 95% CI=1.15-6.41) and MRSA (OR=2.77, 95% CI=1.02-7.55) in blood cultures, CRBSI onset within 30 days from catheter insertion (8-30 days=OR=2.00, 95% CI=1.10-3.63; ≤7 days=OR=2.36, 95% CI=1.04-5.36), concurrent infection (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.31-3.85), a low serum albumin level (OR=2.04, 95% CI=1.28-3.23), lymphocytopenia (OR=0.99, 95% CI=0.99-1.00), low PNI (OR=0.93, 95% CI=0.89-0.97), and a high CRP level (OR=1.07, 95% CI=1.03-1.12). Additionally, the use of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) (OR=0.38, 95% CI=0.17-0.84) and catheter insertion via the brachial vein (OR=0.38, 95% CI=0.17-0.85) were associated with reduced mortality. Factors influencing mortality in patients with CRBSI, such as adequacy of caloric intake and antibiotic treatment duration, were not associated with mortality in the single-variable analysis.

Table III. Patient-related risk factors for mortality caused by catheter-related blood stream infection in the unadjusted logistic regression analysis.

BMI: Body mass index; CI: confidence interval; CRP: C-reactive protein; PNI: prognostic nutritional index; CONUT: controlling nutritional status; OR: odds ratio; Ref: Reference; WBC: white blood cells. †Per 1 unit decrease; ‡per 1 unit increase. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

Table IV. Catheter- and infection-related factors for mortality caused by catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) in the unadjusted logistic regression analysis.

CI: Confidence interval; CoNS: Coagulase-negative staphylococci; CV port: totally implantable central venous access port; CVC: central venous catheter; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; OR: odds ratio; PICC: peripherally inserted central venous catheter; PVC: peripheral venous catheter; Ref: Reference. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

Factors associated with CRBSI mortality in the adjusted (multivariable) logistic regression analysis. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the factors influencing mortality in patients with CRBSI (Table V). To avoid overfitting in the logistic regression analysis (18), catheter type variables were categorized as PICC and non-PICC, pathogens detected on blood culture were categorized as Candida, MRSA, and other than Candida and MRSA, and the time from catheter insertion to CRBSI onset was categorized as <30 days and ≥30 days Catheter insertion via the brachial vein (co-linearity with PICC), total lymphocyte count, and PNI (for overfitting issues and/or co-linearity with serum albumin) were excluded as variables. Furthermore, multivariable analysis was performed after multiple imputations for the missing values. The multivariable analysis revealed that Candida detected in blood culture [adjusted OR (aOR)=2.08, 95% CI=1.10-3.95)], CRBSI onset within 30 days of catheter insertion (aOR=2.28, 95% CI=1.27-4.09), concurrent infection (aOR=2.07, 95% CI=1.19-3.60), a low serum albumin level (aOR=1.64, 95% CI=1.02-2.63), and a high CRP level (aOR=1.05, 95% CI=1.01-1.10) were independently associated with CRBSI mortality.

Table V. Risk factors for mortality caused by catheter-related bloodstream infection as identified in the adjusted multivariable logistic regression analysis.

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; CRP: C-reactive protein; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PICC: peripherally inserted central venous catheter; Ref: Reference. †Per 1 unit decrease; ‡per 1 unit increase. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

Discussion

This study of patients with CRBSI across 33 centers had a 15.6% (71/453) case fatality rate. Factors associated with mortality in patients with CRBSI included the use of catheters other than PICC, Candida detected in blood culture, CRBSI onset within 30 days of catheter insertion, concurrent infection, a low serum albumin level, as well as a high CRP level.

In previous studies, the CRBSI mortality rates have varied, including a 30-day mortality rate of 13.9% at a single center (10), and a crude mortality rate of 35.3% for bloodstream infections in patients in intensive care units (11). A multicenter retrospective cohort study in Spain reported that mortality from CRBSI decreased significantly from 17.9% in 2010 to 10.6% in 2019, with a 30-day mortality rate of 13.8% (12). A report examining the impact of bacterial biofilms on mortality in patients with hematological malignancies who developed bloodstream infections noted that the mortality rates were 55.9% for BSI and 31.8% for central line-associated BSI, with a 30-day mortality rate of 22% (13). Mortality rates due to CRBSI were 7.9% in 1997 and 5.9% in 2008 according to the United States National Hospital Discharge Survey (19). A 10-year cohort study of CRBSI incidence and attributable mortality in intensive care units reported that 17.4% of patients died within 30 days, with a population attributable mortality rate of 18.2% for CRBSI (20). However, comparing these rates between studies is challenging owing to variations in healthcare settings, healthcare systems, and analytical methods. Our results revealed a mortality rate of 15.6%, which may be a representative estimate of the current CRBSI mortality rate, as most participating institutions had nutrition support and infection control teams. Despite improvements in safety procedures and products, such as vascular access devices, infusion routes, and infusion formulations, the mortality rate remains high.

In this study, a PICC inserted through the upper arm was associated with a lower risk of death from CRBSI. Seventeen studies were included for analysis. Meta-analysis of comparative studies showed that PICC use was associated with a significantly lower rate of CRBSI (relative risk=0.40, 95% CI=0.19-0.83) (21), which is consistent with previous studies [reviewed in (22)]. Our study confirms that the use of PICCs is associated with lower CRBSI incidence and mortality. Patients who developed CRBSI within 30 days of catheter insertion had a higher risk of death, with 11 (15.5%) of the 50 patients developing CRBSI within 7 days. Patients who developed CRBSI within 7 days were more likely to have had a contaminated catheter at insertion. CRBSI cannot be directly ruled out as the cause of death; however, its coexistence with an underlying disease may have accelerated disease progression.

Candida is an important cause of CRBSI, accounting for 10-27% of cases (23,24). CRBSI caused by Candida has been reported to have a higher crude mortality rate than that for CRBSI caused by bacterial infections (25), which is consistent with our results.

Low serum albumin and high CRP levels have been identified as internal risk factors for mortality in patients with CRBSI. Al-Rawajfah et al. (26) reported malnutrition as a risk factor for the onset of bloodstream infections in a study of patients with indwelling central venous catheters. Our results suggest that the serum albumin level plays a crucial role as an indicator of nutritional status and a prognostic factor for CRBSI outcomes. In addition, the CONUT identifies malnutrition in hospitalized patients by scoring the serum albumin level, total lymphocyte count, and total cholesterol level as nutritional indicators (27). In this study, the CONUT score was not associated with mortality in patients with CRBSI; however, data on their total cholesterol level were missing for 54% of the patients; therefore, the association between CONUT score and mortality in patients with CRBSI warrants further investigation. In contrast, Onodera et al. (28,29) reported PNI, which combines the albumin level and total lymphocyte count, as an indicator for estimating prognosis after upper gastrointestinal surgery. In this study, PNI was not evaluated as a variable in the multivariable analysis because it had more missing values (19.9%) than serum albumin and was co-linearly related to serum albumin. Low PNI and a low albumin level may be risk factors for mortality in patients with CRBSI. Monitoring nutritional status using the serum albumin level as an indicator may play an important role in preventing death from CRBSI. In addition to a high CRP level, the presence of infection other than CRBSI was an independent predictor of mortality in patients with CRBSI. These factors, along with reduced levels of immunity, promote MRSA and Candida growth at the infection site, elevating the risk of complications from infections other than CRBSI, such as pneumonia and sepsis. Therefore, thoroughly assessing the nutritional status of the patients and improving the nutritional status of patients with malnutrition are important.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, because this was a retrospective observational study, the number of variables that could be extracted was limited, and it was not possible to investigate all previously reported risk factors. Therefore, we may not have fully adjusted for confounding factors, such as the severity of the underlying disease and comorbidities, that influence mortality from CRBSI (30). Secondly, several variables had multiple missing values, and although single-variable analysis was performed without imputing missing values to investigate factors based on actual medical data, the possibility of data bias cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

In conclusion, factors associated with mortality in patients with CRBSI include the use of catheters other than PICC, Candida detected in blood culture, CRBSI onset within 30 days of catheter insertion, concurrent infection, a low serum albumin level, and a high CRP level. Enhanced monitoring of these factors may help reduce the risk of CRBSI severity and mortality. Further studies should investigate additional previously reported risk factors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japanese Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Therapy (grant number not available). The funder had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Authors’ Contributions

AF was the chief investigator and was responsible for organizing and coordinating the study. AF, NM, MM, JI, HM, AS, KM, HO, YT, KH and MU conceived and designed the study. AF and TK collected data. AF, TK, and TN curated data and performed the statistical analyses. AF and TK drafted the article. NM, MM, JI, HM, AS, KM, HO, YT, KH, and MU reviewed the article. All Authors read and approved the final article.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Tomomi Jinnouchi (Makino Rehabilitation Hospital), Naohito Nakamura (Tosei General Hospital), Mizuho Kabeya (Fuefuki Central Hospital), Takaki Kanie (Department of Pharmacotherapeutics and Informatics, Fujita Health University Hospital), Sayaka Taji (Minoh City Hospital), Fumie Yamada (Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital), Takeshi Yoshimi (Japanese Red Cross Medical Center), Toshihiro Nakanishi (Clinical Safety Management Group, Toyota Memorial Hospital), Masaya Ito (Hashima City Hospital), Mayu Shibata (Hamamatsu Red Cross Hospital), Hiroshi Ishihara (Department of Pharmacy, Japanese Red Cross Gifu Hospital), Hiroko Kimbara (Public Central Hospital of Matto Ishikawa), Shin Inoue (Oita Oka Hospital), Keisuke Suzuki (Taito Hospital), Masashi Fujita (Komono Kosei Hospital), Namiki Makiko (Funabashi Municipal Medical Center), Yukari Takeno (Oota Hospital), Yoshihiro Uekuzu (Department of Pharmacy, Fujita Health University Okazaki Medical Center), Yuka Aimono (Hitachi General Hospital), Maho Tatsumi (Kakogawa Central City Hospital), Takashi Matsuzaki (Department of Pharmacy, St. Marianna University, Yokohama Seibu Hospital), Hiroshi Shinonaga (Department of Pharmaceutical Services, Mitoyo General Hospital), Taku Ito (Department of Pharmacy, Tenshi Hospital), Miki Kawasaki (Neuromuscular Center Yoshimizu Hospital), Yoichi Shibata (National Hospital Organization Yamagata Hospital), Hasegawa Mio (Fujiikai Kashibaseiki Hospital), Akiko Sasaki (Hibino Hospital) and Kyouko Mori in Fureai-Kamakura Hospital for providing CRBSI patient data. The Authors thank Editage (https://www.editage.com/) for editing and reviewing the article for the English language.

References

- 1.Pittet D, Tarara D, Wenzel RP. Nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1994;271(20):1598–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.20.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens V, Geiger K, Concannon C, Nelson RE, Brown J, Dumyati G. Inpatient costs, mortality and 30-day re-admission in patients with central-line-associated bloodstream infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(5):O318–O324. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakihama T, Tokuda Y. Use of peripheral parenteral nutrition solutions as a risk factor for Bacillus cereus peripheral venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection at a Japanese tertiary care hospital: a case-control study. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2016;69(6):531–533. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maki DG, Ringer M. Risk factors for infusion-related phlebitis with small peripheral venous catheters. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(10):845–854. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-10-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosoglu S, Akalin S, Kidir V, Suner A, Kayabas H, Geyik MF. Prospective surveillance study for risk factors of central venous catheter–related bloodstream infections. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(3):131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yilmaz G, Koksal I, Aydin K, Caylan R, Sucu N, Aksoy F. Risk factors of catheter-related bloodstream infections in parenteral nutrition catheterization. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2007;31(4):284–287. doi: 10.1177/0148607107031004284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garnacho-Montero J, Aldabó-Pallás T, Palomar-Martínez M, Vallés J, Almirante B, Garcés R, Grill F, Pujol M, Arenas-Giménez C, Mesalles E, Escoresca-Ortega A, de Cueto M, Ortiz-Leyba C. Risk factors and prognosis of catheter-related bloodstream infection in critically ill patients: a multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(12):2185–2193. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bicudo D, Batista R, Furtado GH, Sola A, Servolo de Medeiros EA. Risk factors for catheter-related bloodstream infection: a prospective multicenter study in Brazilian intensive care units. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15(4):328–331. doi: 10.1016/S1413-8670(11)70200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Liang M. A meta-analysis of incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infection with midline catheters and peripherally inserted central catheters. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:6383777. doi: 10.1155/2022/6383777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siempos II, Kopterides P, Tsangaris I, Dimopoulou I, Armaganidis AE. Impact of catheter-related bloodstream infections on the mortality of critically ill patients: A meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(7):2283–2289. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a02a67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saliba P, Hornero A, Cuervo G, Grau I, Jimenez E, García D, Tubau F, Martínez-Sánchez J, Carratalà J, Pujol M. Mortality risk factors among non-ICU patients with nosocomial vascular catheter-related bloodstream infections: a prospective cohort study. J Hosp Infect. 2018;99(1):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badia-Cebada L, Peñafiel J, López-Contreras J, Pomar V, Martínez JA, Santana G, Cuquet J, Montero MM, Hidalgo-López C, Andrés M, Gimenez M, Quesada MD, Vaqué M, Iftimie S, Gudiol C, Pérez R, Coloma A, Marron A, Barrufet P, Marimon M, Lérida A, Clarós M, Ramírez-Hidalgo MF, Garcia Pardo G, Martinez MJ, Chamarro EL, Jiménez-Martínez E, Hornero A, Limón E, López M, Calbo E, Pujol M, Gasch O, Surveillance of health-care associated infections in Catalonia (VINCat) Decreased mortality among patients with catheter-related bloodstream infections at Catalan hospitals (2010-2019) J Hosp Infect. 2022;126:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2022.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Domenico EG, Marchesi F, Cavallo I, Toma L, Sivori F, Papa E, Spadea A, Cafarella G, Terrenato I, Prignano G, Pimpinelli F, Mastrofrancesco A, D’Agosto G, Trento E, Morrone A, Mengarelli A, Ensoli F. The impact of bacterial biofilms on end-organ disease and mortality in patients with hematologic malignancies developing a bloodstream infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9(1):e0055021. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00550-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alverdy JC, Aoys E, Moss GS. Total parenteral nutrition promotes bacterial translocation from the gut. Surgery. 1988;104(2):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opilla M. Epidemiology of bloodstream infection associated with parenteral nutrition. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(10):S173.e5–S173.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otaka S, Ohbe H, Igeta R, Chiba T, Ikeda S, Shiga T. Factors associated with an increase in on-site time of pediatric trauma patients in a prehospital setting: a nationwide observational study in Japan. Children (Basel) 2022;9(11):1658. doi: 10.3390/children9111658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels KR, Frei CR. The United States’ progress toward eliminating catheter-related bloodstream infections: Incidence, mortality, and hospital length of stay from 1996 to 2008. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong Y, Zhou L, Liu X, Deng L, Wu R, Xia Z, Mo G, Zhang L, Liu Z, Tang J. Incidence, risk factors, and attributable mortality of catheter-related bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit after suspected catheters infection: a retrospective 10-year cohort study. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(2):985–999. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hon K, Bihari S, Holt A, Bersten A, Kulkarni H. Rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections between tunneled central venous catheters versus peripherally inserted central catheters in adult home parenteral nutrition: a meta-analysis. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2019;43(1):41–53. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crnich CJ, Maki DG. The promise of novel technology for the prevention of intravascular device–related bloodstream infection. II. Long-term devices. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(10):1362–1368. doi: 10.1086/340105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novosad SA, Fike L, Dudeck MA, Allen-Bridson K, Edwards JR, Edens C, Sinkowitz-Cochran R, Powell K, Kuhar D. Pathogens causing central-line–associated bloodstream infections in acute-care hospitals—United States, 2011-2017. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(3):313–319. doi: 10.1017/ice.2019.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada G, Iwamoto N, Ishikane M, Moriya A, Kurokawa M, Mezaki K, Ohmagari N. Predictive performance of gram staining of catheter tips for candida catheter-related bloodstream infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(12):ofac667. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: Analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(3):309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Rawajfah OM, Stetzer F, Hewitt JB. Incidence of and risk factors for nosocomial bloodstream infections in adults in the United States, 2003. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(11):1036–1044. doi: 10.1086/606167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bae MI, Jung H, Park EJ, Kwak YL, Song Y. Prognostic Value of the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score in patients who underwent cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16(15):2727. doi: 10.3390/cancers16152727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onodera T, Goseki N, Kosaki G. [Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients] Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;85:1001–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian C, Li H, Hou Y, Wang W, Sun M. Clinical implications of four different nutritional indexes in patients with IgA nephropathy. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1431910. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1431910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie C. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]