Abstract

A simple and accurate method for the determination of ibuprofen concentrations in elephant plasma was developed and validated using reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Utilizing a liquid-liquid extraction with ethyl acetate, methanol, and phosphoric acid, samples were separated on an XBridge C18 column. The mobile phase consisted of 0.005 M ammonium phosphate and acetonitrile (40:60, v/v). Both ibuprofen and the internal standard flurbiprofen were quantitated using an ultraviolet (UV) detector set at 214 nm. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 0.05 μg/mL in 100 μL of plasma. The average recovery was over 95 % while the intra-assay variability ranged from 0.8 to 9.9 % and the inter-assay variability ranged from 2.7 to 9.8 %. The method was used successfully in a therapeutic drug monitoring program for elephants and could be used in future pharmacokinetic studies.

Keywords: Ibuprofen, Plasma, Ultraviolet detection

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A simple and accurate improvement on the determination of therapeutic drug monitoring of ibuprofen was developed.

-

•

The method can be used to monitor ibuprofen concentrations in elephants.

-

•

An extraction method that can be applied to other species with a shorter analysis time and lower limit of quantification.

1. Introduction

The importance of pain relief in animals has increased dramatically in recent years. Ibuprofen is a propionic-acid based common nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with analgesic anti-inflammatory and antipyretic properties. It has similar pharmacological actions to other NSAIDs and is commonly used to treat acute and chronic rheumatoid arthritis, fever, headaches, various joint and musculoskeletal disorders. It is one of the most extensively used analgesic drugs for relief of pain in humans and animals. It is a potent inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) [1]. However, chronic use can cause adverse side effects on the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys and liver.

There are a number of elephants in facilities around the world including zoos and circuses. These animals can suffer from a number of musculoskeletal disorders (rheumatoid and osteoarthritis) particularly as they age. To treat these conditions, NSAIDs like ibuprofen are utilized on an empirical basis. However, because of the massive body size and difference in physiology of elephants in comparison to species such as cows and horses, an accurate estimation of dosing requirements is challenging. To manage inflammation and pain effectively in elephants, administration of NSAIDs should happen at a frequency that reduces fluctuations in drug concentrations over time. Chronic use of the drug however, can lead to renal or hepatic impairment, necessitating a determination of safe therapeutic dosing regimens in elephants. Previous dosages of 7 mg/kg twice daily in African elephants have been reported to result in therapeutic serum concentrations, defined as 15–30 mg/L for up to 12 h with the Cmax ranging from 3.9 to 5.1 h [15].

Therapeutic drug monitoring can be useful in a wide range of situations such as, unexplained side effects, possible drug-drug interactions, situations that alter pharmacokinetic parameters and correlations between behavior results and lameness scores where plasma concentrations are necessary. Drug monitoring is widely used in the measurement of drugs to make sure that the medication is at an optimum concentration ensuring a satisfactory therapeutic response without drug-induced adverse effects. It can be especially useful for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, large inter- and intraindividual variability in therapeutic response and pharmacokinetics or when the therapeutic response is difficult to monitor.

This paper presents a straightforward, accurate and rapid method for the quantification of ibuprofen in elephant plasma for therapeutic drug monitoring purposes. This technique was employed for the analysis of samples sent for ibuprofen determination.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reference standards

United States Pharmacopeia grade ibuprofen was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA) while flurbiprofen was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Both compounds were ≥99 % pure and their structures can be seen in Fig. 1. Ammonium phosphate monobasic, methanol, acetonitrile phosphoric acid and ethyl acetate were HPLC grade and acquired from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Water utilized for the preparation of solutions was attained from a Barnstead Nanopure system (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Fig. 1.

Structure of flurbiprofen and ibuprofen.

Five milligrams each of ibuprofen and flurbiprofen (internal standard, IS) were weighed, then dissolved in 50 mL of methanol to obtain stock concentrations of 100 μg/mL. The ibuprofen stock solution was diluted to prepare two working solutions of 10 μg/mL and 1 μg/mL while flurbiprofen was diluted to prepare a 10 μg/mL solution. All flurbiprofen solutions were kept at −20 °C and ibuprofen solutions were stored at 4 °C. All standards were aliquoted into smaller vials to prevent cross contamination. By comparing areas of the quality control samples over time it was verified that the stock solutions were stable for a minimum of 6 months.

A standard curve was prepared by adding different amounts of stock ibuprofen solution to 7 ml glass screw top tubes, evaporating with nitrogen, then adding 100 μL of untreated elephant plasma. The standards used to create the curve were 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL. Five quality control (QC) standards including the LLOQ were picked at low, medium, and high concentrations of 0.05, 0.15, 7.5, 35, and 75 μg/mL.

2.2. Instrumentation

The chromatographic HPLC system was comprised of a Model 2695 separation module and a Model 2489 UV detector (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The column used was an XBridge C18 (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm). Ammonium phosphate monobasic (0.005 M, pH 3) and acetonitrile (40:60, v/v) were used isocratically to elute the compounds. The UV detector was monitored at 214 nm and the flow rate was 1.1 mL/min. The temperature for the column was set to 35 °C and the total run time was 9 min.

2.3. Sample preparation

Ibuprofen was extracted from previously frozen plasma using a liquid-liquid extraction. Samples were allowed to come to room temperature (23 °C) and vortexed to ensure homogeneity. One hundred microliters of plasma were placed in a 7 ml glass borosilicate screw top tube followed by 50 μL of flurbiprofen (IS, 10 μg/mL). After vortexing for 5 s, 100 μL 0.1 M phosphoric acid and 1 mL methanol were added to each tube followed by 1 mL of ethyl acetate. After capping, the tubes were placed on a rocker for 10 min, then underwent centrifugation at 1,864g for 20 min. The organic supernatant was removed and placed in a 13 × 100 mm borosilicate test tube then evaporated with nitrogen. Residues were reconstituted in 250 μL of mobile phase (40:60) followed by centrifugation a second time for 5 min. This solution was then transferred to HPLC vials and a 100 μL aliquot was analyzed.

2.4. Validation of method

The technique was validatied for selectivity, linearity, precision, accuracy, recovery, and stability. The validation was based on the most recent version of the FDAs Guidance for industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation guidelines [2].

2.4.1. Selectivity

A method is said to be selective if no interference happens at the retention times of the compounds of interest. Plasma from six different elephants that had not been given ibuprofen was analyzed to determine if there were any interfereing components.

2.4.2. Linearity and calibration curve

Linearity was assessed over a concentration range of 0.05–100 μg/mL. The calibration curve was constructed using the plasma peak area ratio versus concentration method using the following points 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL on five different days. Linearity was accepted if the correlation coefficient was >0.99.

2.4.3. Precision accuracy and recovery

Quality control (QC) samples used for precision and accuracy were prepared at 4 different concentration levels within the calibration curve range used: the LLOQ (0.05 μg/mL), low (0.15 μg/mL), medium (7.5, and 35 μg/mL) and high QC (75 μg/mL). Five replicates of each QC sample were analyzed within one run and on five diffferent days. From this information, intra- and inter-assay means, standard deviations (SD) and relative standard deviations (RSD) were determined. The accuracy and precision of each QC sample should be within ±15 % of the actual value, excluding the LLOQ which should be within ±20 %. Recovery was described as a percentage of a known quantity of the ibuprofen recovered by the extraction procedure compared to the response of the analyte in the standard solution.

2.4.4. Stability

Stability assessments of the technique were estimiated using the QC samples. The influence of multiple rounds of freezing and thawing, short term stability after extraction and storage in a refrigerator (4 °C) for 24 h and in the autosampler for 24 h were evaluated.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Sample and HPLC optimization summary

Several iterations and compositions of mobile phase concentrations were tested to determine the appropriate elution of ibuprofen and its internal standard. Selected ammonium phosphate concentrations were tested from 0.05 M to 0.005 M, with the latter being selected as the optimum choice for peak shape, baseline noise and shortest retention time. Methanol and acetonitrile were considered for the organic mobile phase component. Ibuprofen and flurbiprofen did elute with methanol, but due to high column pressure (2884 psi with methanol versus 1905 psi with acetonitrile) and long retention time of both analytes (14.6 and 16.4 min), it was replaced with acetonitrile (6.03 and 7.74 min). The impact of column temperature on peak shape and resolution was investigated and higher temperatures caused poor resolution of peaks. Temperatures less than 35 °C increased the analysis time and system pressure. The best resolution was obtained at 35 °C and this produced a run time of less than 10 min for elution of the compounds.

The criteria used for ibuprofen system suitability included: retention time, resolution, USP tailing factor and column efficiency [3]. The retention time was 7.70 ± 0.04. while the resolution, which is a measure of how well the peaks are separated, was 6.35 ± 0.75 (R ≥ 2). The USP tailing factor was 1.19 ± 0.17 which is well within required limits (T ≤ 2) and the column plate count was 11332 (N ≥ 2000). The larger the plate number the greater the efficiency of the column.

Through the development of the technique numerous organic solvents were evaluated, including acetonitrile, chloroform, ethyl acetate, hexane, methyl tert-butyl ether, and methanol. Protein precipitation alone with acetonitrile (60 %) and methanol (70 %) had a minimal recovery. Hexane and chloroform produced recoveries of less than 50 %. Ether and ethyl acetate both produced a higher recovery, however ethyl acetate had much less baseline noise than ether and was selected. The addition of methanol was considered to increase the recovery of flurbiprofen because of its polar nature. Ibuprofen has been found to have an increase in absorption in lower pH mediums so the addition of 0.1 M phosphoric acid was added to increase its recovery. Higher concentrations (0.2–1 M) of phosphoric acid provided no increase in recovery of either compound. When lower volumes of methanol were used this produced noisier baselines while higher volumes did not further increase the recovery of either compound.

There is an increased focus on green analytical chemistry and methodology with the goal of making techniques more environmentally conscience and safer for humans. The quantities and toxicity of reagents, generated waste, and reducing energy requirements through limiting procedural steps, miniaturization, and automation are a few of the criteria studied when evaluating a method's greenness. This method incorporates several standards that increase the greenness. The use of ethyl acetate (not petrol derived), a smaller sample size which decreases reagent use, shorter analysis time which decreases the amount of mobile phase used and waste generated. To access the overall greenness of this method The Analytical GREEness Calculator (AGREE) was used [4]. It is an assessment tool that provides a scored result that is easily interpretable and informative. The method developed here has a score of 0.62 which is considered sufficiently green (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Analytical Greenness report sheet.

3.2. Method validation summary

3.2.1. Selectivity

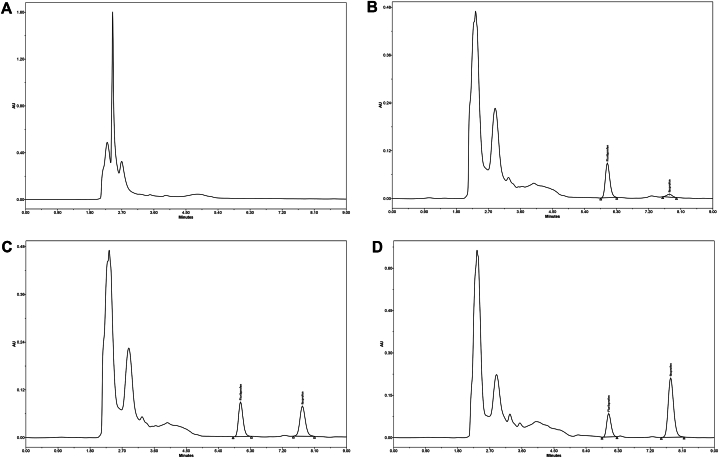

Selectivity of this technique was determined by analyzing ibuprofen free elephant plasma to verify if there were any components in the plasma that affected the elution of flurbiprofen or ibuprofen. There were no interferences detected at either ibuprofen or flurbiprofen retention times (Fig. 3A). The other chromatograms in Fig. 3 are (B) a 0.05 μg/mL standard, which is the lower limit of quantification (C) a 10 μg/mL spiked plasma standard and (D) an elephant sample after administering an oral dose of 6 mg/kg ibuprofen. Elution times were 6.03 and 7.74 min for flurbiprofen and ibuprofen, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Representative chromatograms of (A) untreated elephant plasma, (B) 0.05 μg/ml the lower limit of quantification, (C) 10 μg/mL standard and (D) an elephant sample 6 h after an oral dose of 6 mg/kg ibuprofen.

3.2.2. Linearity, LLOQ and calibration curve

Linearity was determined using eleven (0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 μg/ml) concentrations. The area ratio of ibuprofen and flurbiprofen was paired with the concentration to construct the calibration plot. Visual examination of concentration versus ratio plots suggested that the assumption of linearity was not violated. Results of the F-test indicated that the regression coefficient was significantly (p < 0.0001) different from zero. The coefficient of determination (r2) was 0.9998 which indicated that 99.98 % of the variation in the outcome was described by variation in the concentration variable, indicating a good model fit to the data. The linear relationship for ibuprofen could be defined by the equation y = 0.1114x + 0.0045, with x representing the plasma concentration of ibuprofen in plasma (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assay linearity parameters.

| Assay linearity (n = 5) | Mean ± S.D. | R.S.D. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Y-Intercept | 0.0045 ± 0.001 | 11.57 |

| Slope | 0.1104 ± 0.0004 | 3.66 |

| r2 | 0.9998 ± 0.0001 | 0.006 |

S.D.: standard deviation; n: number of curves; RSD: relative standard.

The LLOQ was 0.05 μg/mL with a signal to noise ratio of ten, while the limit of detection (LOD) was 0.025 μg/mL which characterizes a peak approximately three times baseline noise.

3.2.3. Precision accuracy and recovery

Precision which is the closeness of agreement between a sequence of measurements and accuracy which refers to the closeness of a measured value to a known standard were determined by analyzing five quality control (QC) samples on the same and different days. The QC samples were selected from the low, middle and high end of the curve and also included the LLOQ. The precision values ranged from 0.8 to 10 % (Table 2) while the accuracy values ranged from 100 to 109 % (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ibuprofen validation parameters in plasma (n = 5).

| Intra-assay variability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (μg/mL) | Measured conc. (Mean ± SD) | Accuracy (%) | RSD (%) |

| 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.002 | 100 | 4.0 |

| 0.15 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 100 | 9.9 |

| 7.5 | 8.2 ± 0.07 | 109 | 0.8 |

| 35 | 35 ± 1.3 | 100 | 3.8 |

| 75 | 76 ± 1.98 | 101 | 2.6 |

| Inter-assay variability | |||

| 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.004 | 100 | 8.0 |

| 0.15 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 100 | 6.2 |

| 7.5 | 7.5 ± 0.74 | 100 | 9.8 |

| 35 | 35 ± 1.6 | 100 | 4.6 |

| 75 | 76 ± 2.0 | 101 | 2.7 |

| Recovery | Recovery ± SD | RSD (%) | |

| 0.05 | 98 ± 10.3 | 10.6 | |

| 0.15 | 97 ± 10.1 | 10.0 | |

| 7.5 | 95 ± 1.9 | 2.0 | |

| 35 | 97 ± 5.3 | 5.4 | |

| 75 | 96 ± 6.3 | 6.6 | |

n: number of samples; SD: standard deviation; RSD: relative standard deviation.

The extraction efficiency of ibuprofen expressed as a percentage, was determined by comparing peak areas of the drug in the standard solution at a known concentration to those in extracted elephant plasma. The recovery of ibuprofen ranged from 95 % to 97 % (Table 2) whereas the recovery of flurbiprofen was 98 % ± 1.5 %.

3.2.4. Stability

Quality control standards were assessed for short term stability after extraction and storage in the refrigerator (4 °C) for 24 h and after storing in the autosampler at room temperature (23 °C) for 24 h. Ibuprofen quality control concentrations at time zero were compared to the concentrations after the applied storage conditions. Ibuprofen experienced a 34 % loss overnight in the autosampler, with a 22 % loss after refrigeration. This would indicate that care should be exercised in analyzing large sample batches that stay in the autosampler for long periods of time and storage in the refrigerator for long periods should be done with caution. Quality control standards (0.15, 7.5, 35 and 75 μg/mL) in elephant plasma were initially analyzed and then placed in a −80 °C freezer. The samples were removed and allowed to thaw and a 100 μL removed for analysis and then returned to the −80 °C. The procedure was repeated 3 separate times and no sample loss occurred for the QC standards (Table 3). Since this method involved therapeutic drug monitoring the samples were analyzed as soon as they were collected so long-term stability was not performed. However, Al-Talla et al. [5] found that ibuprofen was stable after 48 days of storage at −35 °C.

Table 3.

Stability data of ibuprofen under freeze-thaw conditions expressed as recovery.

| Ibuprofen Concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | 0.15 μg/mL (%) recovery | 7.5 μg/mL (%) recovery | 35 μg/mL (%) recovery | 75 μg/mL (%) recovery |

| Time 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Cycle 1 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| Cycle 2 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 100 |

| Cycle 3 | 99 | 100 | 101 | 100 |

N = 3.

3.3. Method application

Two aged elephants that were on oral ibuprofen for chronic arthritis had plasma samples collected as part of a therapeutic drug monitoring program. Published pharmacokinetic results for ibuprofen in African elephants [15] are limited in terms of pharmacodynamic considerations. Clinicians were investigating if there were correlations between behavioral ethogram results and lameness scores with plasma concentrations, to determine if the twice daily dosing regime and timing was effective and suitable to the elephants needs. In addition, the limited numbers of animals in this study, coupled with a variable Cmax, Tmax and half-life, suggests that further investigations are prudent to guard against poor dosing regimens. The developed technique was applied to the determination of ibuprofen plasma concentrations from both of those elephants. One was administered 6 mg/kg and the other 4.5 mg/kg orally twice a day. A chromatogram of one of the samples is illustrated in Fig. 3D. The sample was collected 4 h after oral administration of the 6 mg/kg dose and represents a concentration of 26.52 μg/mL. The other elephant sample analyzed was collected 3 h after oral administration of a 4.5 mg/kg oral dose and had a concentration of 7.20 μg/mL.

3.4. Comparison to other published methods

Several methods have been described for the analysis of ibuprofen in plasma and other matrices [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]], however many of the reported methods have limitations (Table 4). The majority of these methods use ultraviolet (UV) detection [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10],[12], [13], [14], [15]] while a few use mass spectrometry (MS) [11,[16], [17], [18]]. Some of the UV methods require 1 mL of sample [ 6, 7] while others require 0.5 mL [8,10,11,13,15]. Certain methods [7,8,12,18] use solid phase extraction cartridges (SPE) which can add cost and time to the analysis. The Nakov et al. [18], SPE method also requires 60 min to evaporate the eluent while the Kaluzny & Bannow [7] method needs 6 mL of solution to elute the drug from the SPE cartridge and then time to evaporate that volume.

Table 4.

Method comparison.

| Reference | Limitations |

|---|---|

| G.F. Lockwood, & J.G. Wagner. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of ibuprofen and its major metabolites in biological fluids. J. Chromatogr., 232 (1982), pp. 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4347(00)84173-0 | 1 ml sample size required Higher LOQ 5 μg/mL Requires 10 mL methylene chloride |

| B.D. Kaluzny, & C.A. Bannow. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of pimeprofen and its metabolite ibuprofen in sheep plasma and lymph. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 414 (1987), pp. 228–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4347(87)80046-4 | 1 ml sample size required Higher LOQ 0.5 μg/mL Uses SPE cartridges and requires 6 mL acetonitrile to elute sample 60 % recovery 40-min run time |

| M. Castillo, & P.C. Smith. Direct determination of ibuprofen and ibuprofen acyl glucuronide in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography using solid-phase extraction. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl, 614 (1993), pp. 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4347(93)80229-W | 0.5 mL sample size Higher LOQ 0.5 μg/mL Extensive extraction process with 8.5 ml of phosphate buffer needed prior to SPE extraction 70 % recovery 30 min run time |

| E.S. Jung, H.S. Lee, J.K. Rho, & K.I. Kwon. Simultaneous determination of ibuproxam and ibuprofen in human plasma by HPLC with column switching. Chromatographia, 37 (1993), pp. 618–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02274112 | Higher LOQ 0.1 μg/mL Complicated column switching technique 30 min run time |

| J. Sochor, J. Klimeš, J. Sedláček, & M. Zahradníček. Determination of ibuprofen in erythrocytes and plasma by high performance liquid chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 13 (1995), pp. 899–903. | 0.5 mL sample size Requires gradual acidification a, shaking and further acidification then extraction with 6 mL of organic |

| B.A. Way, T.R. Wilhite, C.H. Smith, & M. Landt. Measurement of plasma ibuprofen by gas chromatography‐mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Lab. Anal., 11 (1997), pp. 336–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1997)11:6<336::AID-JCLA4>3.0.CO;2-3 | 0.5 mL sample size Higher LOQ 5 μg/mL Complicated extraction that requires the use of diethylether 2′xs and then derivatization 22 min run time |

| H. Farrar, L. Letzig, & M. Gill. Validation of a liquid chromatographic method for the determination of ibuprofen in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B., 780 (2002), pp. 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00543-3 | Higher LOQ 1.56 μg/mL SPE extraction 87 % recovery |

| P. Wang, M. Qi, L. Liu, & L. Fang. Determination of ibuprofen in dog plasma by liquid chromatography and application in pharmacokinetic studies of an ibuprofen prodrug in dogs. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 38 (2005), pp. 714–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2005.02.013 | 0.5 mL sample size Higher LOQ 1 μg/mL 13 min run time |

| X. Zhao, D. Chen, K. Li, & D. Wang. Sensitive liquid chromatographic assay for the simultaneous determination of ibuprofen and its prodrug, ibuprofen eugenol ester, in rat plasma. Yakugaku Zasshi, 125 (2005), pp. 733–737. https://doi.org/10.1248/yakushi.125.733 | 0.2 mL sample size Higher LOQ 0.64 μg/mL 90 % recovery 20 min run time |

| U. Bechert, & J.M. Christensen. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered ibuprofen in African and Asian elephants (Loxodonta Africana and Elephas maximus). JZWM, 38 (2007), pp. 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1638/2007-0139R.1 | 0.5 mL sample size Higher LOQ 0.1 μg/mL Sample must be extracted 2′xs with 4 mL of cyclohexane |

| A. Szeitz, A.N. Edginton, H.T. Peng, B. Cheung, & K.W. Riggs. A validated enantioselective assay for the determination of ibuprofen in human plasma using ultra performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). AJAC, 1 (2010), pp. 47–58. https://doi.org/10.4236/AJAC.2010.12007 | Complicated extraction process, samples must be frozen in −80C then have the residue evaporated and then derivatized 84 % recovery 12 min run time |

| J.L.C. Cardoso, V.L. Lanchote, M.P.M. Pereira, N.V. de Moraes, & J.S. Lepera. Analysis of ibuprofen enantiomers in rat plasma by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci, 37 (2014), pp. 944–949. https://doi.org/10.1002/jssc.201301184 | 0.2 mL sample size Complex extraction with 5 mL of hexane/diisopropylether then placed in a shaker for 30 min 25 min run time 89 % recovery |

| N. Nakov, R. Petkovska, L. Ugrinova, Z. Kavrakovski, A. Dimitrovska, & D. Svinarov. Critical development by design of a rugged HPLC-MS/MS method for direct determination of ibuprofen enantiomers in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl., 992 (2015), pp. 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.04.029 | Higher LOQ 0.1 μg/mL Has 2 different extractions listed, liquid-liquid with ethyl acetate or SPE 80 % recovery 14 min run time |

The Jung et al. [9], method uses a complex column switching technique and requires a 30-min analysis time. Several other methods also have extended analysis times between 12 and 40 min [[7], [8], [9],11,13,14,17,18] while the one developed in this procedure is 9 min which decreases time and cost of analysis. Many of the UV and MS methods [[6], [7], [8], [9],[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]] have a much higher limit of quantification (0.1–5 μg/mL) than the method presented here (0.05 μg/mL).

The method discussed in this paper has a lower LLOQ than all previous UV methods and all but one MS method, which used a larger sample volume. This method has a shorter analysis time than all the other methods and a straightforward extraction method that does not require SPE cartridges, column switching, large amounts of solvent, 60-min evaporation times or derivatization. If a lower LLOQ is needed the sample size could be increased.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a sensitive, rapid, and validated method for determining ibuprofen concentrations in elephant plasma. The method was validated based on FDA Bioanalytical guidelines and has met all the necessary criteria. It offers excellent sensitivity, linearity, precision and recovery. This method is an improvement on existing determination techniques for ibuprofen by using straightforward sample preparation, a shorter run time and is economical with respect to reagent consumption and waste production. This technique has been applied to the analysis of samples submitted to the laboratory for therapeutic monitoring. While sample size was not an issue with the species in this article, this method could be useful for smaller animals and investigators dealing with small sample volumes. Due to its simplicity, this method should be applicable to other species for the quantitation of ibuprofen.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sherry Cox: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Aaron Bloom: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Riley Golias: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Madeline Duncan: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Joan Bergman: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Andrew Cushing: Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Davies N.M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1998;34:101–154. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199834020-00002. https://doi:10.2165/00003088-199834020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FDA Guidance for industry: bioanalytical method validation. 2021. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM070107.pdf

- 3.FDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Reviewer Guidance Validation of chromatographic methods. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/reviewer-guidance-validation-chromatographic-methods

- 4.Pena-Pereira F., Wojnowski W., Tobiszewski M. AGREE—analytical GREEnness metric approach and software. Anal. Chem. 2020;92:10076–10082. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Talla Z.A., Akrawi S.H., Tolley L.T., Sioud S.H., Zaater M.F., Emwas A.-H. Bioequivalence assessment of two formulations of ibuprofen. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2011;5(2011):427–433. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S24504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lockwood G.F., Wagner J.G. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of ibuprofen and its major metabolites in biological fluids. J. Chromatogr. 1982;232:335–343. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4347(00)84173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaluzny B.D., Bannow C.A. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of pimeprofen and its metabolite ibuprofen in sheep plasma and lymph. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 1987;414:228–234. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(87)80046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castillo M., Smith P.C. Direct determination of ibuprofen and ibuprofen acyl glucuronide in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography using solid-phase extraction. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 1993;614:109–116. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80229-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung E.S., Lee H.S., Rho J.K., Kwon K.I. Simultaneous determination of ibuproxam and ibuprofen in human plasma by HPLC with column switching. Chromatographia. 1993;37:618–622. doi: 10.1007/BF02274112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sochor J., Klimeš J., Sedláček J., Zahradníček M. Determination of ibuprofen in erythrocytes and plasma by high performance liquid chromatography. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1995;13:899–903. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Way B.A., Wilhite T.R., Smith C.H., Landt M. Measurement of plasma ibuprofen by gas chromatography‐mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 1997;11:336–339. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1997)11:6<336::AID-JCLA4>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrar H., Letzig L., Gill M. Validation of a liquid chromatographic method for the determination of ibuprofen in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B. 2002;780:341–348. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang P., Qi M., Liu L., Fang L. Determination of ibuprofen in dog plasma by liquid chromatography and application in pharmacokinetic studies of an ibuprofen prodrug in dogs. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2005;38:714–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao X., Chen D., Li K., Wang D. Sensitive liquid chromatographic assay for the simultaneous determination of ibuprofen and its prodrug, ibuprofen eugenol ester, in rat plasma. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2005;125:733–737. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.125.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bechert U., Christensen J.M. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered ibuprofen in African and Asian elephants (Loxodonta Africana and Elephas maximus) JZWM. 2007;38:258–268. doi: 10.1638/2007-0139R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szeitz A., Edginton A.N., Peng H.T., Cheung B., Riggs K.W. A validated enantioselective assay for the determination of ibuprofen in human plasma using ultra performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) AJAC. 2010;1:47–58. doi: 10.4236/AJAC.2010.12007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardoso J.L.C., Lanchote V.L., Pereira M.P.M., de Moraes N.V., Lepera J.S. Analysis of ibuprofen enantiomers in rat plasma by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2014;37:944–949. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201301184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakov N., Petkovska R., Ugrinova L., Kavrakovski Z., Dimitrovska A., Svinarov D. Critical development by design of a rugged HPLC-MS/MS method for direct determination of ibuprofen enantiomers in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 2015;992:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]