Abstract

Fusichalara pallida sp. nov. is described from decaying wood submerged in a freshwater stream in Taiwan. The phylogenetic relationship of Fusichalara species was sought among representative taxa from related fungal lineages, namely the Chaetosphaeriales and Glomerellalles in the Sordariomycetes, and various other ordinal groups in the Eurotiomycetes, by comparing the concatenated ITS and LSU sequences of their nuc rDNA. The novel Fusichalara species from Taiwan clustered with F. minuta within the Sclerococcales besides other ordinal groups in the Eurotiomycetes. Morphologically, F. pallida is comparable with F. dimorphospora and F. novae-zelandiae in having long-cylindrical first-formed conidia and fusiform subsequent conidia with paler end cells, however, they differ in conidial dimensions. With the addition of this novel taxon, Fusichala now comprises seven species. A synopsis of these species and a composite illustration of their conidial morphology are given to ease identification.

Keywords: Asexual freshwater fungi, dimorphic conidia, lignicolous fungi, phialoconidia, phylogeny

1. Introduction

This paper is a taxonomic treatment of a Fusichalara strain collected from Taiwan that could not be identified and provides its phylogenetic placement.

Fusichalara is a small genus currently comprising six species (Index Fungorum, 2024). It was established by Hughes and Nag Raj (1973) for three Chalara-like anamorphic fungi: F. dimorphospora S. Hughes & Nag Raj (the type species), F. dingleyae S. Hughes & Nag Raj, and F. novae-zelandiae S. Hughes & Nag Raj. They are lignicolous, dematiaceous hyphomycetes with cylindrical phialides but differ from Chalara in the presence of a pronounced wall-thickening inside the phialide at the point of transition from venter to collarette, and in producing two morphologically different kinds of phialoconidia; the first-formed conidium is cylindrical whereas those produced subsequently are fusiform or sigmoid (Hughes & Nag Raj, 1973). Three other species, all with hyaline septate conidia with truncate bases, vaguely similar to the three core species of Fusichalara, have been subsequently added to the genus: F. minuta Hol.-Jech. (Gams & Holubova-Jechova, 1976), F. clavatispora P.M. Kirk (Kirk & Spooner, 1984), and F. goanensis Bhat & W.B. Kendr. (Bhat & Kendrick, 1993).

Recent phylogenetic studies showed that Fusichalara is a polyphyletic genus. Except for F. dingleyae (Réblová, 2004) and F. minuta (Réblová et al., 2017), molecular data of the other four Fusichalara species are not available and their phylogenetic relationships are unknown. Fusichalara dingleyae was confirmed experimentally by ascospore isolation and molecular data to be the asexual morph of Chaetosphaeria fusichalaroides Réblová (Chaetosphaeriales, Sordariomycetes) (Réblová, 2004), whereas F. minuta was phylogenetically placed in the Sclerococcales (Eurotiomycetes) (Réblová et al., 2017). Since the sequence data of the generic type, Fusichalara dimorphospora, is currently unavailable, therefore, the genus is placed in Ascomycota genera incertae sedis (Wijayawardene et al., 2018).

During our continuing survey of microfungi occurring on plant litter submerged in freshwater streams of Taiwan (Goh & Kuo, 2018, 2020, 2021; Hsieh et al., 2021a, 2021b; Kuo & Goh 2018a, 2018b, 2019, 2021; Kuo et al., 2022), we collected an undescribed species of Fusichalara. We identify this fungus morphologically as a new species by comparing it with all other previously described Fusichalara species. In the present paper, we investigated its phylogenetic lineage, whether it belong to the Chaetosphaeriales (as F. dingleyae) or the Sclerococcales (as F. minuta). Since the genus is polyphyletic and phylogenetic positions of the type and three other species are yet to be resolved, we follow Réblová et al. (2017) to describe the present novel taxon as a species of Fusichalara based on morphology. A synopsis of the form-species and a composite diagram showing their conidial morphology are provided for comparison and ease of identification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample collection and morphological studies

Plant litter including wood was collected in plastic bags and returned to the laboratory where the samples were incubated at room temperature on moist filter paper in sterile plastic boxes. Materials were examined periodically for the presence of sporulating fungal structures and species were identified primarily based on morphology. Squashed mounts of fungal structures were prepared using fresh materials from their natural substrata (wood) in lactophenol. Conidia were measured using Axiocam 506 Color with operating software ZEN 2 Blue Lite linked to a Zeiss Axioskop 2 Plus microscope. The average conidial size was calculated based on 20 measurements. Single-spore isolations were made by using a hand-made glass needle. Isolated conidia were cleaned by dragging and rolling them on the surface of 3% water agar (Goh, 1999). The process was examined by using a stereo-microscope. Several small agar blocks, each containing a single cleaned conidium were eventually transferred to potato dextrose agar (PDA) slants or plates. The agar slants and plates containing the single conidia were incubated at 20 °C to obtain pure cultures. The holotype specimen was deposited in the Herbarium at the National Museum of Natural Science (NMNS), Taichung, Taiwan (herbarium code, TNM). An ex-type culture was deposited at the Bioresource Collection and Research Centre (BCRC), Food Industry Research and Development Institute, Hsinchu, Taiwan. A duplicate of dried specimen (isotype) was deposited at the Department of Plant Medicine, National Chiayi University (NCYU), Chiayi, Taiwan. All the fungal DNA sequences generated from the present study were deposited at GenBank.

2.2. DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing for fungal isolates

DNA extraction was carried out following Sambrook and Russell (2001) by using biomass from 60-d-old PDA cultures. DNA amplification was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using an experimental sample cocktail consisting of 2−8 ng DNA template, 0.4 ng forward primer and reverse primer, PCR Master Mix II (5×) (Bioman Scientific Co., Ltd., Taiwan). The large subunit ribosomal RNA gene (LSU) and the internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS) were amplified using the primers LR0R (5'-ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC-3') and LR5 (Vilgalys & Hester, 1990), and ITS5/ITS4 (White et al., 1990), respectively. Sequencing was performed on a Cycle Sequencing Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Analyzer, with BigDyeR Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA), by using the Sanger dideoxy sequencing method (Zimmermann et al., 1988) and the final sequence was assembled from two or more overlapping sequence reads.

2.3. Phylogenetic analysis

The LSU and ITS sequences generated in this study were supplemented with additional sequences retrieved from GenBank representing taxa from several related ordinal lineages of fungi (Table 1) from the Eurotiomycetes (i.e., namely Chaetothyriales, Coryneliales, Mycocaliciales, Onygenales, and Sclerococcales), and the Sordariomycetes (i.e., Chaetosphaeriales and Glomerellales). Trichoglossum hirsutum AFTOL-ID 64 (Leotiomycetes) was selected as the outgroup. Each dataset containing 41 sequences was analyzed. MUSCLE was used for DNA alignment (Edgar, 2004). Poorly aligned positions of DNA alignment were manually modified where necessary. After alignment, uneven ends were trimmed off. The alignment block of concatenated sequences was 1903 bp long (including gaps), and the dataset was partitioned at the 1106-1107 bp positions separating the LSU-ITS segments. The alignment file is attached to this paper as supplemental information. The evolutionary history of the combined dataset was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods in RAxML version 8.2.10 and MrBayes v3.2.6 under UBUNTU 19.10 (64-bit) operating system (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck, 2003; Stamatakis, 2014). The substitution model was GTR + Gamma. The best substitutional model was tested separately for each of the gene segments and the concatenated dataset. For RAxML, all random seeds for rapid bootstrapping and tree inferences were explicitly set to 5566 during the analysis to ensure reproducibility. Analyses were repeated based on 1000 bootstrapped data sets to obtain non-parametric bootstrap support (BS). MrBayes was run for 1,000,000 generations, with trees sampled every 100 generations. The first 25% of sampled trees were discarded (relburnin). Additional phylogenetic trees inferred from the concatenated sequence and the individual gene segments (ITS and LSU) using the Neighbour-Joining method were run in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016) and the results are attached with this paper as supplemental information.

Table 1. Taxa and sources of sequences used in the present phylogenetic analysis.

| Fungal taxon | Fungal strain/isolate | ITS | LSU | Fungal lineage |

| Aphanoascus verrucosus | NBRC 32381 | JN943440 | JN941553 | Onygenales |

| Ascosphaera apis | CBS 402.96 | MH862580 | FJ358275 | Onygenales |

| Brunneodinemasporium brasiliense | CBS 112007 | JQ889272 | JQ889288 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Caliciopsis orientalis | CBS 138.64 | KP881690 | DQ470987 | Coryneliales |

| Camptophora hylomeconis | CBS 113311 | KC455241 | EU035415 | Chaetothyriales |

| Ceramothyrium carniolicum | CBS 175.95 | KC978733 | KC455251 | Chaetothyriales |

| Chaenothecopsis savonica | Tibell 15876 | AY795868 | AY796000 | Mycocaliciales |

| Chaetosphaeria decastyla | NN055410 | OL627834 | OL655134 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Chaetosphaeria fusichalaroides | LAMIC0149/13 | KX499466 | KR363058 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Chaetosphaeria obovoidea | GZCC 22-0085 | ON502901 | ON502894 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Chloridium chloroconium | CBS 149055 | OP455398 | OP455505 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Chloridium peruense | CBS 126074 | OP455424 | OP455531 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Cladophialophora humicola | CBS 117536 | EU035408 | KC809987 | Chaetothyriales |

| Cladophialophora minutissima | CBS 121758 | MH863155 | KJ636047 | Chaetothyriales |

| Codinaeella lutea | CBS 624.77 | OL654086 | OL654143 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Corynelia africana | ARW 247 | KP881693 | KP881714 | Coryneliales |

| Corynelia fruitigena | ARW 250 | KP881704 | KP881716 | Coryneliales |

| Cylindroconidius aquaticus | MFLUCC 11-0294 | MH236576 | MH236579 | Sclerococcales |

| Cylindrotrichum clavatum | CBS 125239 | GU291799 | GU180649 | Glomerellales |

| Cyphellophora laciniata | CBS 190.61 | KF928483 | FJ358239 | Chaetothyriales |

| Cyphellophora sessilis | CBS 243.85 | MH861875 | EU514700 | Chaetothyriales |

| Dactylospora stygia | HN2022090370 | OQ534124 | OQ534408 | Sclerococcales |

| Dactylospora vrijmoediae | NTOU 4002 | KJ958534 | KC692153 | Sclerococcales |

| Fusichalara minuta | CBS 709.88 | KX537754 | KX537758 | Sclerococcales |

| Fusichalara pallida | BCRC FU31906 | OR944928 | OR944931 | Sclerococcales |

| Kylindria chinensis | MFLUCC 16-0965 | MH120190 | MH120186 | Glomerellales |

| Kylindria peruamazonensis | CBS 838.91 | GU180628 | GU180638 | Glomerellales |

| Lagenulopsis bispora | ARW 249 | KP881709 | KP881717 | Coryneliales |

| Menispora tortuosa | AFTOL-ID 278 | KT225527 | AY544682 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Menisporopsis theobromae | MFLUCC 15-0055 | KX609957 | KX609954 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Mycocalicium polyporaeum | ZWGeo60Clark | AY789363 | AY789362 | Mycocaliciales |

| Onygena corvina | CBS 225.60 | MH857958 | MH869510 | Onygenales |

| Reticulascus tulasneorum | CBS 570.76 | MH861002 | MH872775 | Glomerellales |

| Rhopalophora clavispora | CBS 281.75 | KX537752 | KX537756 | Sclerococcales |

| Sclerococcum martynii | F-1570b | MZ221616 | MZ221623 | Sclerococcales |

| Sclerocooccum simplex | MFLU 21-0117 | MZ664325 | MZ655912 | Sclerococcales |

| Spiromastix warcupii | CBS 576.63 | MH858362 | DQ782909 | Onygenales |

| Sporoschisma hemipsilum | DLUCC 0700 | KX455869 | KX455862 | Chaetosphaeriales |

| Sporoschismopsis angustata | CBS 136360 | KF730739 | KF730740 | Glomerellales |

| Stenocybe pullatula | Tibell 17117 | AY795878 | AY796008 | Mycocaliciales |

| Trichoglossum hirsutum | AFTOL-ID 64 | DQ491494 | AY544653 | Leotiomycetes |

3. Results

3.1. Phylogeny

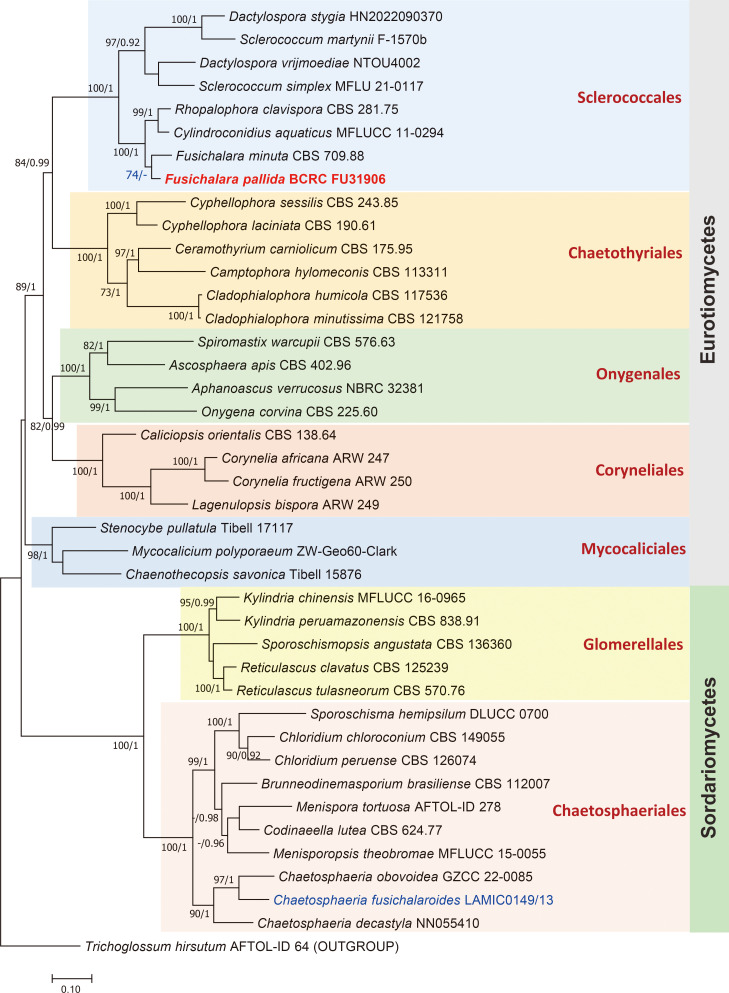

As MegaBlast search results show, the ITS barcode similarity of the new species to the most closely related F. minuta is 93.79%, indicating that they are distinct species. The phylogenetic tree inferred from the aligned sequences of 41 taxa from related fungal lineages is shown in Fig. 1. Numbers on nodes represent ML bootstrap values (greater than 70%) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (greater than 0.90) are shown in the tree. Within the alignment block, there were a total of 1065 distinct alignment patterns for analysis (i.e., LSU = 501, ITS = 564), with 991 variable sites including 764 parsimony-informative sites and 193 singleton sites. Molecular data revealed several small clusters of taxa belonging to various fungal groups representing various ordinal lineages within the Eurotiomycetes and Sordariomycetes. The new Fusichalara species collected from Taiwan (BCRC-FU31906) clustered together with F. minuta (CBS 709.88) with a ML bootstrap support of 74% but without support by Bayesian inference. In the phylogenetic tree inferred from the concatenated dataset generated by the neighbour-joining method (not shown), however, the two Fusichalara species clustered together with a higher bootstrap support of 91%. In both trees, the two species of Fusichalara were adjacent to a clade comprising Cylindroconidius aquaticus (MFLUCC 11-0294) and Rhopalophora clavispora (CBS 281.75), with a 100% bootstrap support. These four taxa were adjacent to a clade consisting of Dactylospora and Sclerococcum species, and all formed a cluster representing members of the Sclerococcales with a 100% bootstrap support. Chaetosphaeria fusichalaroides (LAMIC0149/13), the sexual morph of Fusichalara dingleyae, clustered with the other two Chaetosphaeria species with an ML bootstrap value of 90% (Bayesian posterior probabilities = 1.00), and they were among other representative taxa in the Chaetosphaeriales with a 100% bootstrap support.

Fig. 1 - RAxML phylogenetic tree with BI inferred from concatenated ITS and LSU partial sequences of the rDNA showing relationships of Fusichalara species with other taxa in the Sclerococcales and other fungal lineages. The tree is rooted with Trichoglossum hirsutum AFTOL-ID 64 (Leotiomycetes). Numbers on nodes represent ML bootstrap values (greater than 70%) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (greater than 0.90). The new Fusichalara species (in bold red font) from Taiwan is among members of Sclerococcales. Chaetosphaeria fusichalaroides (in blue font), the teleomorph of Fusichalara dingleyae, is within the clade comprising several representative chaetosphaeriaceous taxa.

3.2. Taxonomy

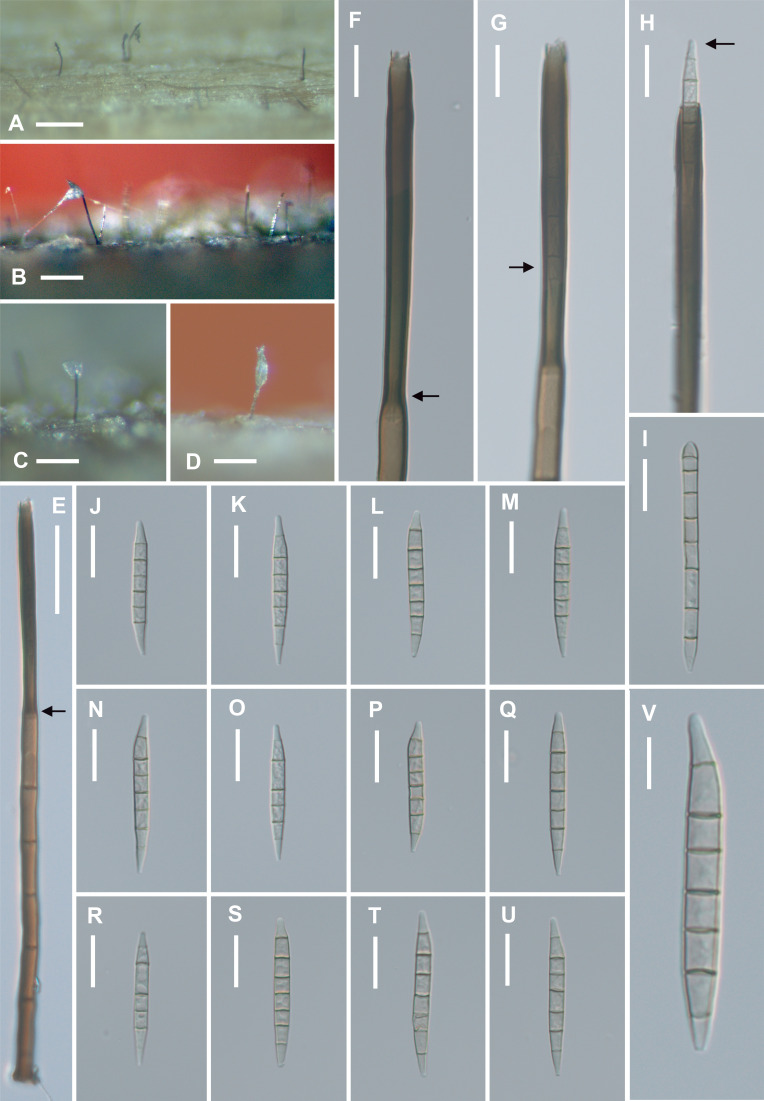

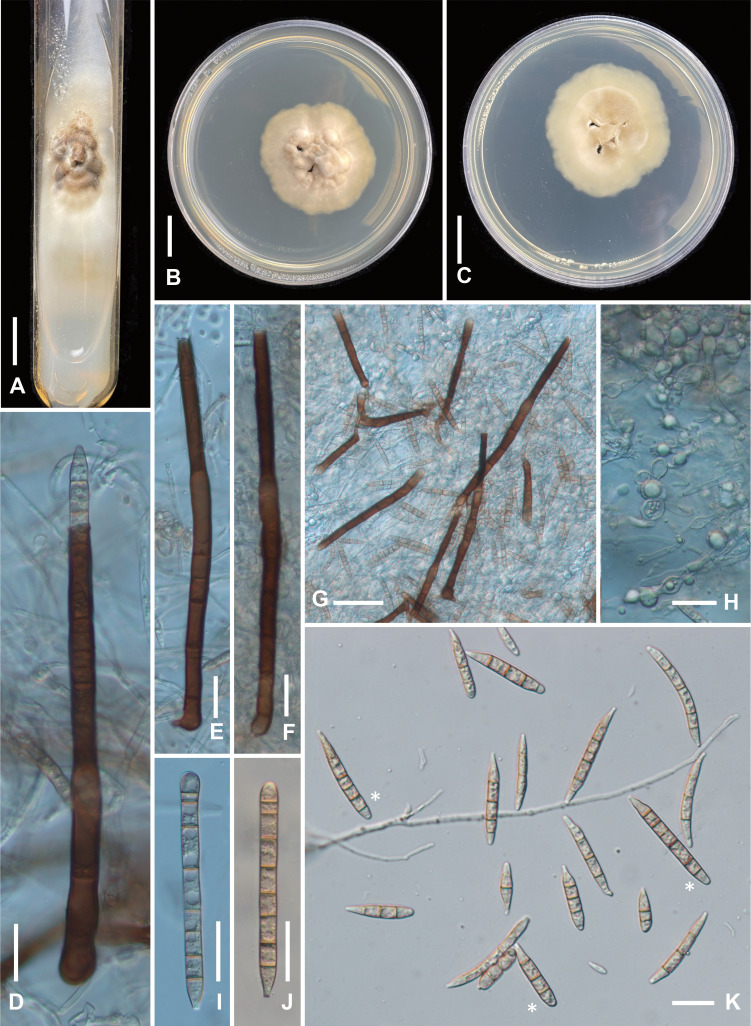

Fusichalara pallida C.H. Kuo, S.Y. Hsieh & Goh, sp. nov. Figs. 2, 3

MycoBank No.: MB 851385.

Fig. 2 - Fusichalara pallida (TNM F0037300, holotype). A, B: Colonies on natural substratum. C, D: Conidiophores on natural substratum, bearing a tuft of conidial mass at the apex. E: A conidiophore. Arrow indicates the point of transition from venter to the darker tubular collarette. F: Closer view of phialide. Note the pronounced wall-thickening (arrow) inside the phialide at the base of the tubular collarette. G: Closer view of phialide. Arrow indicates a conidium in the tubular collarette. H: Closer view of phialide showing a conidium emerging at the opening of the tubular collarette. Arrow points to the conically rounded conidial apex. I: A first-formed conidium which is cylindrical, with a rounded apex and an obconically truncate base. J-U: Subsequent conidia which are typically fusiform, 7-septate, and have paler end cells. Note that each conidium is conically rounded at the apex and obconically truncate at the base. V: Higher magnification of a subsequently formed conidium. Bars: A 500 µm; B-D 200 µm, E 50 µm; F-U 20 µm; V 10 µm.

Fig. 3 - Ex-type cultures of Fusichalara pallida (BCRC-FU31906). A: Colony on a PDA slant developed from single-spore isolate. B: Colony on PDA plate (surface view). C: Colony on PDA plate (reverse side). D: A conidiophore showing a subsequent conidium emerging at the tip of the phialide. E, F: Conidiophores. G: Squashed mount showing conidiophores, conidia, and chlamydospores. H: Mycelium showing chlamydospore formation (monilioid hyphae). I, J: First-formed conidia. K: Conidia, first-formed conidia (indicated by asterisks) are cylindrical whereas subsequent conidia are fusiform. Bars: A−C 1 cm; D−F, H−K 20 µm; G 50 µm.

Diagnosis: This species differs from other Fusichalara species in conidial morphology (first-formed conidia 8-septate, subsequent conidia 7-septate, with pale coloration)

Type: TAIWAN, Taoyuan County, Fuxing District (24.647−121.444, 1099.11 m a.s.l), on decaying wood submerged in a freshwater stream, leg. Chang-Hsin Kuo, 14 May 2022, 111FX4-2A3 (holotypus, TNM F0037300; isotype, NCYU-111FX4-2A3); ex-holotype living culture BCRC:FU31906).

DNA sequences from ex-holotype strain: OR944928 (ITS), OR944931 (LSU).

Etymology: pallida, referring to the paler coloration of the conidia when compared with that of the type species (F. dimorphospora).

Colonies on natural substratum scattered, black, hairy. Mycelium immersed, composed of subhyaline to pale brown, smooth hyphae. Conidiophores scattered, solitary or in loose fascicle of 2-3, erect, unbranched, straight or slightly curved, cylindrical, brown to dark brown, smooth-walled, up to 5-7-septate, 280-320 × 9.5-10.5 µm, not distinctly inflated to demarcate the venter of the phialide, bearing a distinctly darker tubular collarette at the distal end. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, integrated, terminal, determinate, subcylindrical, 110-120 × 9.5-11 µm, composed of a poorly differentiated, very slightly inflated venter and a tubular collarette 95-117 × 9.5-11 µm, the point of transition from venter to collarette slightly constricted (6.5-7.5 µm wide), with pronounced wall-thickening of the inner wall; distal end of tubular collarette bearing a conspicuous rim of ragged marginal frills at the opening, producing endogenous conidia successively which accumulate in a slimy mass after emergence from the tubular collarette. Phialoconidia of two kinds: first-formed conidia long-cylindrical, rounded at the apex, obconic-truncate at the base, straight, very pale orange-brown, 8-septate, 87-92 × 5.5-6 µm; subsequent conidia elongate-fusiform to slightly sigmoid, narrowly rounded at the apex (ca 2 µm wide), obconic-truncate at the base (1.0-1.5 µm wide) , predominantly 7-septate, versicolorous, median cells very pale orange-brown, end cells subhyaline, (47.5-)52-67 × 5-6(-6.5) µm ( = 58.5 × 5.5 µm, n = 20). Sexual morph undetermined.

Single conidia in PDA slants germinated readily (100%), but growth was extremely slow, with a growth rate of about 0.5 mm/d. Colonies on PDA slants (Fig. 3A) were pale creamy brown, with a broad fuzzy margin composed of thin aerial mycelium. On PDA plates (Fig. 3B), colonies attained 4.7 cm diam in 100 d at 20 °C, more or less effuse, funiculose, with sparse mycelium on the surface, pale creamy brown, with a slightly wavy margin, evenly colored, reverse side similar in appearance to upper side (Fig. 3C). Vegetative hyphae (Fig. 3H) smooth, branched, septate, hyaline, 1.5-2.5 μm wide, frequently appearing monilioid and becoming intercalarily swollen, forming chlamydospores of 3-6 µm diam (Fig. 3H). Conidiophores in culture arising from submerged mycelium, often in a terminal position (Fig. 3D-G), morphologically similar to those produced on natural substratum. First-formed conidia in culture (Fig. 3I, 3J) cylindrical, pale brown,(5-)6-8(-9)-septate, 87-92 × 5.5-6 µm; subsequent conidia (Fig. 3K) fusiform, narrowly rounded at the apex (ca 2 µm wide), obconic-truncate at the base (1.5-1.5 µm wide), (1-)2-4(-5)-septate, versicolorous, median cells pale orange-brown, end cells subhyaline, (47.5-)52-67 × 5-6(-6.5) µm ( = 58.5 × 5.5 µm, n = 20).

Habitat and distribution: Saprobic on decaying wood submerged in freshwater streams; known only from the type locality (Taiwan).

4. Discussion

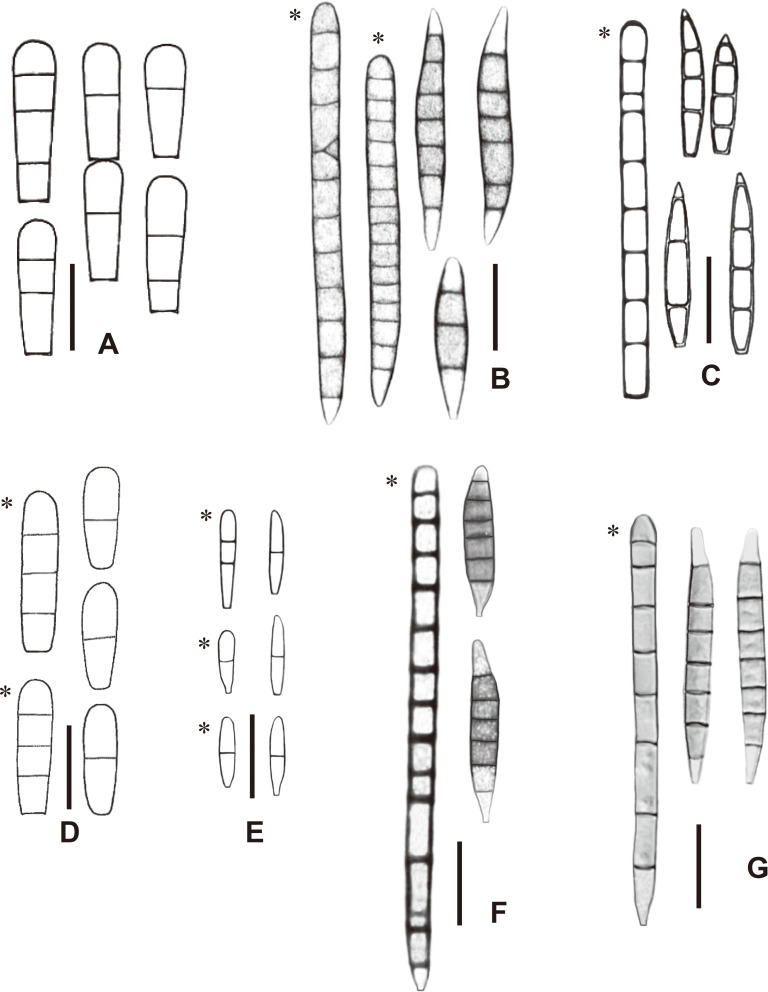

Morphologically, Fusichalara pallida is comparable with F. dimorphospora and F. novae-zelandiae in having long-cylindrical first-formed conidia and fusiform subsequent conidia with paler end cells (Fig. 4), however, they differ in conidial dimensions (Table 2). Fusichalara dimorphospora differs in having first-formed conidia which are wider (7-9 µm vs. 5.5-6 µm), occasionally with one or a few oblique septa, and subsequent conidia which are wider (7-10 µm vs. 5-6.5 µm). Fusichalara pallida is most similar to F. novae-zealandiae but the latter differs in having first-formed conidia with more septa (9-18 vs. 8) and subsequent conidia which are distinctly shorter (27-47 µm vs. 47.5-67 µm). Phylogenetically, F. pallida clustered with F. minuta within the Sclerococcales (Fig.1) and was closely related to the genera Cylindroconidius X.D. Yu & H. Zhang (as ‘Cylindroconidiis’, Yu et al. 2018) and Rhopalophora. However, Cylindroconidius differs in having polyblastic conidiogenous cells that produce Diplococcium-like conidia (Yu et al., 2018). On the other hand, both Fusichalara and Rhopalophora have phialidic conidiogenous cells, but the conspicuous wall thickening at the base of the tubular collarette and the longer, septate, dimorphic conidia in Fusichalara can readily distinguish it from Rhopalophora (Réblová et al., 2017).

Table 2. Comparison of Fusichalara species.

| Species | Current ordinal position | Size of the tubular collarettes (μm) | First formed conidia | Subsequent conidia | Holotypus and type locality | Natural substratum | References | ||||||

| Shape | Septation | Coloration | Size (μm) | Shape | Septation | Coloration | Size (μm) | ||||||

| F. clavatispora | ascomycetous incertae sedis | 12-20 × 4-5 | elongate cuneiform to clavate (apex broadly rounded , base truncate) | 1-3 | hyaline | 12-16 × 3.5-4 | elongate cuneiform to clavate (apex broadly rounded , base truncate) | 1-3 | hyaline | 12-16 × 3.5-4 | IMI 252673a; The Isle of Arran (Scotland) |

dead stem of Rubus fruticosus | Kirk & Spooner, 1984 |

| F. dimorphospora | ascomycetous incertae sedis | 70-130 × 13.5-15.3 | Long-cylindrical (apex bluntly rounded, base obconic) | 11-17; sometimes with one or a few oblique septa | pale brwon to brown, base subhyaline | 85-126 × (6-)7-9 | fusiform or slightly sigmoid (base more tapered than the apex) | (3-5)7(-8) | median cells brown, end cells subhyaline | 7-septate conidia (50-)60-72 × 9-10; 3-septate conidia 36-38 ×7.2 -8.3 |

PDD 30402; Westland District (New Zealand) |

dead bark of Weinmannia racemosa | Hughes & Nag Raj, 1973 |

| F. dingleyae | Chaetosphaeriales | 65-110 × 8-9.5 | Long-cylindrical (apex bluntly round, base truncate) | 7-16 | hyaline | 62.5-83.5(-95) × 5.5-6.5 | fusiform (apex narrowly conical, base truncate) | 3-5 | hyaline to subhyaline | 36-58 × 5-5.6 | PDD 21599; Auckland Province (New Zealand) |

rotten wood | Hughes & Nag Raj, 1973 |

| F. goanensis | ascomycetous incertae sedis | 18-24 × 6.5-8 | nearly cylindrical (apex rounded, base truncate) | 3 | hyaline | 17-22 × 5-6 | nearly cylindrical (apex rounded, base truncate) | 1 | hyaline | 12-15 × 4.5-5.5 | DAOM 214604; Goa State (India) |

decaying twig | Bhat & Kendrick, 1993 |

| F. minuta | Sclerococcales | 11-14 × 2.5-3 | clavate (apex rounded, base truncate) | 1-2 | hyaline | (9.5-)10.5-15 × 2-2.5 | fusiform or fusiform-clavate (apex narrowly rounded, base obconic-truncate) | 1 | hyaline | (10-)11-12.5 × 2-2.5 | PRM 795927; Central Bohemia Region (Czech Republic) |

decaying trunk of Quercus petraea | Gams & Holubová-Jechová, 1976; Réblová et al., 2017 |

| F. novae-zelandiae | ascomycetous incertae sedis | (60-)80-100 (-120) × 8-11 | Long-cylindrical (apex rounded, base narrowly truncate) | 9-12(-18) | subhyaline to pale brown | 83-105 × 5.5-6.5 | fusiform to slightly sigmoid (apex narrowly rounded, base obconic-truncate) | 7 | median cells pale brown, end cells subhyaline | (27-)30-40(-47) × 5-6.5(-7) | PDD 30404; Auckland Province (New Zealand) |

rotten wood of Leptospermum scoparium | Hughes & Nag Raj, 1973 |

| F. pallida | Sclerococcales | 95-117 × 9.5-11 | Long-cylindrical (apex rounded, base narrowly truncate) | 8 | very pale orange-brown | 87-92 × 5.5-6 | elongate-fusiform to slightly sigmoid (apex narrowly rounded, base obconic-truncate) | 7 | median cells very pale orange-brown, end cells subhyaline | (47.5-)52-67 × 5-6(-6.5) | TNM F0037300 Fuxing District (Taiwan) |

Submerged wood | This paper |

Fig. 4 - Conidia of Fusichalara species, re-illustrated with reference to the literature (Hughes & Nag Raj, 1973; Kirk & Spooner, 1984; Bhat & Kendrick, 1993; Réblová et al., 2017). A: F. clavatispora. B: F. dimorphospora. C: F. dingleyae. D: F. goanensis. E: F. minuta. F: F. novae-zelandiae. G: F. pallida. First-formed conidia are indicated by an asterisk (*). Bars: A, D 10 µm; B, C, E-G 20 µm.

Fusichalara species have distinct dematiaceous conidiophores bearing an integrated phialide with a tubular collarette. This feature is reminiscent of the erect, lageniform conidiophores with a tubular collarette in species of Sporoschisma Berk. & Broome and Sporoschismopsis Hol.-Jech. & Hennebert (Goh et al., 1997). With sufficient molecular studies in the past decade, Sporoschisma species have been proven to be members of the Chaetosphaeriales (Yang et al., 2016) whereas the genus Sporoschismopsis was positioned in the Glomerellales (Réblová, 2014). The present phylogenetic analysis concurred with these findings, and confirmed that Fusichalara pallida and F. minuta, although both are comparable in having similar conidiogenous features, belong to the Sclerococcales (Eurotiomycetes), which is phylogenetically distant from species of Sporoschisma and Sporoschismopsis that are members of the Sordariomycetes.

Fusichalara dingleyae is one of the core species described by Hughes and Nag Raj (1973) for the establishment of the genus. It has dark, robust, dark conidiophores with a terminal, long-cylindrical phialide, producing septate conidia occasionally in readily seceding chains. These conidiogenous features are typically found in the chaetosphaeriaceous genus Sporoschisma. Moreover, Fusichalara dingleyae has been experimentally confirmed to be the asexual morph of Chaetosphaeria fusichalaroides (Réblová, 2004) and phylogenetic studies have also proven its position in the Chaetosphaeriales. These results clearly showed that the genus Fusichalara is polyphyletic, species of which could be members of Chaetosphaeriales, Sclerococcales, or further orders.

Fusichalara dingleyae is recognized by its reddish-brown, coarsely roughened conidiophores growing in fascicles on a thin stroma and hyaline, predominantly 3-7-septate fusiform conidia (Hughes & Nag Raj, 1973). The other six known species of Fusichalara have brown to black conidiophores that are solitary rather than fasciculate on the natural substrata. The present collection of F. pallida from Taiwan has morphological features comparable with F. dimorphospora and F. novae-zelandiae in having predominantly 7-septate, versicolorous conidia with median cells that are uniformly pigmented and end cells that are hyaline to subhyaline. In contrast, Fusichalara clavatispora, F. goanensis and F. minuta have hyaline conidia that differ from those of F. dingleyae, F. dimorphospora, F. novaezelandiae, and F. pallida in shape, size, septation, and coloration. Fusichalara clavatispora is also somewhat atypical of the genus because its phialides possess a swollen venter and there is no distinction between the first-formed and subsequent conidia (Kirk & Spooner, 1984). These differences indicate that the genus Fusichalara is somewhat morphologically heterogeneous. Due to the phylogenetic uncertainty of the genus, we refrain from constructing a taxonomic key to the species for the time being, but merely provide a synopsis and a composite illustration of the form-species to ease their identification.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All the experiments undertaken in this study comply with the current laws of Taiwan where they were performed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported, in part, by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (Grant Number 111-2621-B-415-001) and the Ministry of Agriculture of Taiwan (Grant Number 113AS-1.7.1-AS-03). We would like to thank Dr Jie-Hao Ou for his constructive opinion regarding the phylogenetic analysis of fungi. Thanks are extended to Ms. Shing-Yu Lin and Ms. Hsin-Yi Peng for general technical support.

References

- Bhat, D. J., & Kendrick, B. (1993). Twenty-five new conidial fungi from the Western Ghats and the Andaman Islands (India). Mycotaxon, 49, 19-90. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research, 32, 1792-1797. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gams, W., & Holubová-Jechová, V. (1976). Chloridium and some other dematiaceous hyphomycetes growing on decaying wood. Studies in Mycology, 13, 1-99. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, T. K. (1999). Single-spore isolation using a hand-made glass needle. Fungal Diversity, 2, 47-63. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, T. K., Ho, W. H., Hyde, K. D., & Umali, T. E. (1997). New records and species of Sporoschisma and Sporoschismopsis from submerged wood in the tropics. Mycological Research, 101, 1295-1307. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953756297003973 [Google Scholar]

- Goh, T. K., & Kuo, C. H. (2018). A new species of Helicoön from Taiwan. Phytotaxa, 346, 141-156. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.346.2.2 [Google Scholar]

- Goh, T. K., & Kuo, C. H. (2020). Jennwenomyces, a new hyphomycete genus segregated from Belemnospora, producing versicolored phragmospores from percurrently extending conidiophores. Mycological Progress, 19, 869-883. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, T. K., & Kuo, C. H. (2021). Reflections on Canalisporium, with descriptions of new species and records from Taiwan. Mycological Progress, 20, 647-680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-021-01689-6 [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, S. Y., Goh, T. K., & Kuo, C. H. (2021. a). A taxonomic revision of Stanjehughesia (Chaetosphaeriaceae, Sordariomycetes), with a novel species S. kaohsiungensis from Taiwan. Phytotaxa, 484, 261-280. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.484.3.2 [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, S. Y., Goh, T. K., & Kuo, C. H. (2021. b). New species and records of Helicosporium sensu lato from Taiwan, with a reflection on current generic circumscription. Mycological Progress, 20, 169-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-020-01663-8 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, S. J., & Nag Raj, T. R. (1973). New Zealand fungi. 20. Fusichalara gen. nov. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 11, 661-671. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.1973.10430307 [Google Scholar]

- Index Fungorum (2024). Retrieved March 31, 2024, from http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/Names.asp [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, P. M., & Spooner, B. M. (1984). An account of the fungi of Arran, Gigha and Kintyre. Kew Bulletin, 38, 503-597. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G., & Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 1870-1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C. H., & Goh, T. K. (2018. a). Two new species of helicosporous hyphomycetes from Taiwan. Mycological Progress, 17, 557-569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-018-1384-7 [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C. H., & Goh, T. K. (2018. b). A new species and a new record of Helicomyces from Taiwan. Mycoscience, 59, 433-440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.myc.2018.04.002 [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C. H., & Goh, T. K. (2019). Ellisembia acicularia sp. nov. and four new records of freshwater hyphomycetes from streams in the Alishan area, Chiayi County, Taiwan. Nova Hedwigia, 108, 185-196. https://doi.org/10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2018/0493 [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C. H., & Goh, T. K. (2021). Two new species and one new record of Xenosporium with ellipsoidal or ovoid conidia from Taiwan. Mycologia, 113, 434-449. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.2020.1837566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C. H., Hsieh, S. Y., & Goh, T. K. (2022). Wenhsuisporus taiwanensis gen. et sp. nov., a peculiar setose hyphomycete from submerged wood in Taiwan. Mycological Progress, 21, 409-426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-021-01748-y [Google Scholar]

- Réblová, M. (2004). Four new species of Chaetosphaeria from New Zealand and redescription of Dictyochaeta fuegiana. Studies in Mycology, 50, 171-186. [Google Scholar]

- Réblová, M. (2014). Sporoschismopsis angustata sp. nov., a new holomorph species in the Reticulascaceae (Glomerellales), and a reappraisal of Sporoschismopsis. Mycological Progress, 13, 671-681. [Google Scholar]

- Réblová, M., Untereiner, W. A., Štěpánek, V., & Gams, W. (2017). Disentangling Phialophora section Catenulatae: disposition of taxa with pigmented conidiophores and recognition of a new subclass, Sclerococcomycetidae (Eurotiomycetes). Mycological Progress, 16, 27-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-016-1248-y [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist, F., & Huelsenbeck, J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics, 19, 1572-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., & Russell, D. W. (2001). Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis, A. (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics, 30, 1312-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys, R., & Hester, M. (1990). Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology, 172, 4238-4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S., & Taylor, J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J., & White, T. J. (Eds.), PCR protocols: A guide to methods and applications (pp. 315-322). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayawardene, N. N., Hyde, K. D., Lumbsch, H. T., Liu, J. K., Maharachchikumbura, S. S. N., Ekanayaka, A. H., Tian, Q., & Phookamsak, R. (2018). Outline of Ascomycota: 2017. Fungal Diversity, 88, 167-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-018-0394-8 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., Liu, J. K., Hyde, K. D., Bhat, D. J., JONES, E. G., & Liu, Z. Y. (2016). New species of Sporoschisma (Chaetosphaeriaceae) from aquatic habitats in Thailand. Phytotaxa, 289, 147-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.289.2.4 [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X. D., Dong, W., Bhat, D. J., Boonmee, S., Zhang, D., & Zhang, H. (2018). Cylindroconidiis aquaticus gen. et sp. nov., a new lineage of aquatic hyphomycetes in Sclerococcaceae (Eurotiomycetes). Phytotaxa, 372, 79-87. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.372.1.6 [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, J., Voss, H., Schwager, C., Stegemann, J., & Ansorge, W. (1988). Automated Sanger dideoxy sequencing reaction protocol. FEBS Letters, 233, 432-436. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(88)80477-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.