Significance

Compared to peritrichous bacteria such as Salmonella or Escherichia coli, most polarly flagellated bacteria produce shorter flagellar filaments. By investigating how FlaG actively limits polar flagellar filament length in Campylobacter jejuni, we found that FlaG functions as an antagonist to interfere with docking of FliS chaperone–flagellin complexes to FlhA of the flagellar T3SS export gate. FlaG interacted with FlhA at a different site than FliS–flagellin complexes to hinder delivery and secretion of flagellins to elongate the flagellar filament. We present a mechanism for flagellar filament length control in bacteria that restricts the linear dimension of the flagellum. This mechanism relies on FlaG functioning as an antagonist that targets FlhA to negatively impact secretion of a major substrate, flagellin.

Keywords: FlaG, Campylobacter jejuni, flagellar filament length, FlhA, FliS

Abstract

Bacteria power rotation of an extracellular flagellar filament for swimming motility. Thousands of flagellin subunits compose the flagellar filament, which extends several microns from the bacterial surface. It is unclear whether bacteria actively control filament length. Many polarly flagellated bacteria produce shorter flagellar filaments than peritrichous bacteria, and FlaG has been reported to limit flagellar filament length in polar flagellates. However, a mechanism for how FlaG may function is unknown. We observed that deletion of flaG in the polarly flagellated pathogens Vibrio cholerae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Campylobacter jejuni caused extension of flagellar filaments to lengths comparable to peritrichous bacteria. Using C. jejuni as a model to understand how FlaG controls flagellar filament length, we found that FlaG and FliS chaperone–flagellin complexes antagonize each other for interactions with FlhA in the flagellar type III secretion system (fT3SS) export gate. FlaG interacted with an understudied region of FlhA, and this interaction appeared to be enhanced in ΔfliS and FlhA FliS-binding mutants. Our data support that FlaG evolved in polarly flagellated bacteria as an antagonist to interfere with the ability of FliS to interact with and deliver flagellins to FlhA in the fT3SS export gate to control flagellar filament length so that these bacteria produce relatively shorter flagella than peritrichous counterparts. This mechanism is similar to how some gatekeepers in injectisome T3SSs prevent chaperones from delivering effector proteins until completion of the T3SS and host contact occurs. Thus, flagellar and injectisome T3SSs have convergently evolved protein antagonists to negatively impact respective T3SSs to secrete their major terminal substrates.

The flagellum is a reversible rotary motor that promotes swimming motility for many bacteria for navigation through environments to reach ideal niches for growth and survival. As such, flagella are often important for bacterial pathogens to infect hosts for colonization and pathogenesis of disease. Flagellar motor structures are generally conserved across bacterial flagellates with a flagellar type III secretion system (fT3SS) at the cytoplasmic membrane, a rod that connects the fT3SS to the surface-localized hook, and an extracellular filament that rotates for propulsion (1, 2). The majority of proteins involved in forming the flagellum are exported through the fT3SS. The fT3SS export gate is made up of three major components: a core complex, a substrate specificity switch, and a cytoplasmic docking site for chaperone-loaded secretion substrates. The core complex is composed of FliP, FliQ, and FliR, which form a pore in the cytoplasmic membrane (3). FlhB associates with the pore and controls the substrate specificity switch to transition the fT3SS from secreting rod and hook proteins to filament proteins (4–7). FlhA forms a nonamer in the fT3SS export gate. The N-terminal transmembrane domains of FlhA encircle the FliPQR pore and FlhB and function as an ion transporter to couple flagellar protein secretion to the proton motive force (8, 9). The FlhA C-terminal domain is connected to the transmembrane region by a linker and multimerizes to form a nonameric torus (10, 11). Chaperone-loaded flagellar substrates dock to the fT3SS export gate at the FlhA torus to deliver substrates for secretion (12–14). Flagellar chaperones undergo a conformational change upon binding their substrates that enable them to interact with the FlhA torus for substrate delivery and secretion (15, 16).

Flagellar proteins are secreted by the fT3SS for stepwise construction of the flagellum (reviewed in refs. 1, and 17). Substrates secreted by the fT3SS travel through the hollow core of the flagellar structure and polymerize on the growing tip of the nascent flagellum to build different substructures of the organelle (18–20). Checkpoints in the flagellar biogenesis pathway allow bacteria to detect completion of specific substructures before activating expression and secretion of flagellar proteins to form the next substructure. These regulatory mechanisms help ensure that flagellar substructures are at correct dimensions for optimal flagellar motor function. For instance, the FlgJ rod cap captures rod proteins to polymerize on the periplasmic surface of the fT3SS for outward extension of the rod to about ~22 nm until the rod contacts the outer membrane (21, 22). This checkpoint then triggers replacement of FlgJ with the FlgD hook cap that captures proteins for hook polymerization (23, 24). FliK is secreted as a linear protein during rod-hook assembly to function as a molecular ruler to ensure a hook of ~55 nm in length is formed (25–30). When this hook length is achieved, the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of FliK simultaneously interact with the hook and FlhB of the fT3SS at the cytoplasmic membrane, respectively, to induce FlhB to initiate a substrate specificity switch to halt hook protein secretion and activate filament protein secretion (5, 6, 31, 32). Initiation of filament biogenesis requires replacement of the FlgD hook cap with the FliD filament cap. Flagellins are then secreted and diffuse through the channel to the tip where FliD facilitates their incorporation into the filament (33, 34). Thousands of flagellin subunits form the filament that is rotated by the flagellar motor for swimming motility.

In contrast to the rod and hook, it is unclear whether mechanisms broadly exist in flagellated bacteria to control flagellar filament length. Some passive mechanisms influencing flagellar filament length have been described. Stochastic differences in cytoplasmic flagellin levels within a bacterial population can cause cells to produce a range of filament lengths (35). An injection-diffusion model for flagellins also has been discovered that controls the rate of filament polymerization, which limits flagellar filament length (36, 37). In this model, the injection rate of flagellin subunits by the fT3SS controls the rate of filament polymerization at the onset of filament biogenesis until hindered diffusion limits filament polymerization. After this point, the diffusion rate of injected flagellins to an increasingly distant filament tip influences filament polymerization rate, which decreases as filament length increases. This injection-diffusion model suggests that the filament stops elongating once it reaches a critical length impairing flagellins to reach the tip.

Most studies described above that analyzed influences on flagellar filament length were performed in peritrichous organisms such as Salmonella enterica or Escherichia coli that commonly produce filaments ~10 μm or longer. However, many polar flagellates such as Vibrio, Campylobacter, and Pseudomonas species produce shorter filaments, often under 5 μm (38–41). These observations support that polar flagellates may employ an active mechanism to control flagellar filament length and produce short filaments. One protein noted to influence filament length in polarly flagellated bacteria is FlaG. Mutation of flaG in Vibrio anguillarum, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Campylobacter jejuni caused substantially longer filament lengths compared to isogenic WT strains, suggesting that FlaG negatively impacts filament length (39, 42–44). In Treponema denticola, FlaG also influences filament length, along with the stability of flagellins (45). Although a mechanism is elusive, FlaG must ultimately control filament length by directly or indirectly preventing addition of flagellins at the filament tip, which is microns from the cell.

C. jejuni is an amphitrichous flagellate that produces a single flagellum at both cellular poles. Production of polar flagella and flagellar motility are required for the bacterium to infect animals and avian species for commensal colonization and humans for diarrheal disease (46–51). Previous studies investigated a role for FlaG and growth temperature on flagellar filament length of C. jejuni (39, 40, 44). Mutation of flaG caused a doubling in flagellar filament length, which may be responsible for a mild impairment in swimming motility and pellicle formation for biofilm development (39, 44). Although not investigated, FlaG was proposed to inhibit flagellin gene transcription to control flagellar filament length (39). In another study, increasing growth temperature to 42 °C, which is the body temperature of natural avian hosts for C. jejuni and suitable for growth of the bacterium, caused a 15% increase in filament length (40). This increase was linked to enhanced σ28 activity, which is required for transcription of the major flaA flagellin gene, at 42 °C. However, a flaG mutant was not analyzed in this study. Thus, whether FlaG- and temperature-dependent mechanisms are intertwined to influence filament length broadly across C. jejuni strains to control flagellar filament length is unknown.

In this study, we examined the role of FlaG in controlling flagellar filament length in C. jejuni strain 81-176, a commonly studied strain that promotes diarrheal disease in humans and commensal colonization of the chick intestinal tract (46, 51). We show that FlaG targets a conserved, understudied site on FlhA of the fT3SS export gate for an interaction to antagonize the ability of FliS–flagellin complexes to dock to FlhA. This antagonism by FlaG curbs flagellin delivery to the fT3SS to limit secretion and polymerization of flagellins into the filament to result in polarly flagellated bacteria producing shorter flagellar filaments than peritrichous organisms. In providing a mechanism for how polarly flagellated bacteria control flagellar filament length, we reveal FlaG as an endogenous antagonist that exerts negative control of fT3SS activity.

Results

Mutation of flaG Increases Flagellar Filament Lengths of Polarly Flagellated Pathogens.

In the peritrichous flagellate E. coli, fliD (encoding the filament cap) is organized in an operon with the downstream genes, fliS (encoding the flagellin chaperone), and fliT (encoding the FliD chaperone). This operon is also conserved in the polarly flagellated pathogens, C. jejuni, Vibrio cholerae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and H. pylori (Fig. 1A). However, flaG orthologs are present immediately upstream of fliD and are likely transcribed with this operon in polarly flagellated bacteria. We first analyzed whether polarly flagellated pathogens consistently produced shorter filament lengths than a peritrichous bacterium and whether mutation of flaG altered filament length. We analyzed lengths of at least 100 flagellar filaments of E. coli K-12, C. jejuni 81-176, P. aeruginosa PA14, and V. cholerae C6706 cells from three independent cultures by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). E. coli cells produced filament lengths averaging 4.67 μm with a range from 1.27 to 10.57 μm (Fig. 1B). In contrast, C. jejuni, P. aeruginosa, and V. cholerae cells produced shorter flagellar filaments on average (3.09 to 3.92 μm) that rarely extended beyond 6 μm. However, deletion of flaG from polarly flagellated bacteria universally increased flagellar filament lengths (Fig. 1 B and C). Mean filament lengths increased from 3.09 to 5.28 μm for C. jejuni, 3.54 to 4.90 μm for P. aeruginosa, and 3.91 to 4.67 μm for V. cholerae. Populations of flaG mutant cells produced a much broader range of filament lengths that were more similar to E. coli than isogenic WT cells, with some flagellar filaments in ΔflaG cells ≥12 μm. We observed no differences in the number of flagellated cells between WT and ΔflaG strains. We concluded that FlaG in polarly flagellated bacteria is necessary to produce shorter flagellar filaments and a narrower range of filament lengths than a peritrichous flagellate. We focused on understanding how FlaG controls flagellar filament length in C. jejuni for the remainder of this study.

Fig. 1.

Effect of FlaG on flagellar filament lengths in polarly flagellated bacteria. (A) Genomic organization of the flaG operon in flagellated bacteria. flaG (green) is present directly upstream of genes required for flagellar filament biogenesis including fliD (blue, encoding the filament cap), fliS (yellow, encoding the flagellin chaperone), and fliT and putative fliT orthologs (orange or white, encoding the FliD chaperone) in the C. jejuni, H. pylori, P. aeruginosa, and V. cholerae strains shown, but absent from this locus in E. coli K-12. (B) Flagellar filament lengths of WT bacteria and isogenic ΔflaG mutants. Flagellar filaments were measured from micrographs of negatively stained cells acquired by TEM. Each circle represents the length of a flagellar filament on a cell. Over 100 flagellar filaments were measured from three independent cultures (n > 300). Bar represents mean filament length. Statistical significance was calculated by the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test (*P < 0.05 between filament lengths of WT E. coli and other WT species; **P < 0.05 between filament lengths of WT strains and isogenic ΔflaG mutants). (C) Transmission electron micrographs of WT and ΔflaG mutant strains. WT cells of polarly flagellated bacteria are shown as Insets in the micrograph of respective ΔflaG mutants. (Scale bar, 1 μm.) (D). Flagellar filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and ΔflaG upon in trans complementation with WT flaG or flaGΔG43-E50-FLAG. Flagellar filament lengths of WT with vector (vec) alone, WT with vector containing WT flaG (WT), ΔflaG with vector alone, ΔflaG with vector containing WT flaG, or ΔflaG with vector containing flaGΔG43-E50-FLAG (ΔG43-E50-FLAG). Flagellar filaments were measured from micrographs of negatively stained cells acquired by TEM. Each circle represents the length of a flagellar filament on a cell. Over 100 flagellar filaments were measured from three independent cultures (n > 300). Bar represents mean filament length. Statistical significance was calculated by the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test (*P < 0.05 between filament lengths WT C. jejuni with vector alone and other strains; **P < 0.05 between filament lengths of ΔflaG with vector alone and ΔflaG complemented with vectors containing WT flaG or flaGΔG43-E50-FLAG).

We constructed two plasmids to express flaG from both its native σ54- and σ28-dependent promoters for in trans complementation. One plasmid expressed WT flaG whereas the other expressed a FlaG protein in which residues G43-E50 (GQQRGVSE) were replaced with the amino acid sequence for a FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK; FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG). This region of FLAG was predicted by AlphaFold 3 to form a part of an alpha helix following an unstructured region (52). Replacement of FlaG G43-E50 with the FLAG tag sequence was predicted to preserve the alpha helix with no other structural alterations to the protein according to AlphaFold 3. Introduction of either plasmid into C. jejuni ΔflaG restored FlaG production and WT filament lengths on average, with a small population of cells that produced elongated filaments (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Increasing FlaG production by introducing flaG in trans on a plasmid in WT caused a mild decrease in mean filament length (2.7 μm vs. 3.17 μm) and shifted the distribution of filaments toward shorter filaments compared to WT with vector alone (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

FlaG Impacts Length of Filaments Composed by Either the FlaA or FlaB Flagellin.

C. jejuni produces the FlaA major flagellin and the FlaB minor flagellin that are 95% identical and 97% similar in amino acid sequence to form flagellar filaments (53–55). FlaB primarily composes only a limited portion of the filament proximal to the hook, and FlaA forms most of the remainder of the filament (39, 55). flaA transcription is dependent on σ28, whereas flaB like flagellar rod and hook genes is dependent on σ54 for transcription (56–59). Both σ28- and σ54-dependent promoters are located upstream of flaG, suggesting that flaG, fliD, and fliS are cotranscribed simultaneously with both flagellin genes (56, 59).

We assessed whether FlaG controlled filament length regardless of the flagellin composition of the filament. Flagellar filament lengths in the flaA mutant (which only produces a filament with the FlaB minor flagellin) were very short, but deletion of flaG significantly increased both the mean (0.68 μm vs. 1.0 μm) and range of filament lengths (Fig. 2 A and B). Flagellar filament lengths of WT and flaB mutant cells (which only produce filaments with the FlaA major flagellin) were similar, but deletion of flaG in the flaB mutant increased the mean filament length (2.9 to 5.0 μm; Fig. 2 A and B). Thus, FlaG regulated flagellar filament length regardless of the flagellin composition of the filament.

Fig. 2.

Effect of FlaG on flagellar filament lengths in C. jejuni flagellin mutants. (A) Flagellar filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and ΔflaA or ΔflaB mutants with or without flaG. Flagellar filaments were measured from micrographs of negatively stained cells acquired by TEM. Each circle represents the length of a flagellar filament on a cell. Over 100 flagellar filaments were measured from three independent cultures (n > 300). Bar represents mean filament length. Statistical significance was calculated by the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test (*P < 0.05 between filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and mutants; **P < 0.05 between filament lengths of ΔflaA or ΔflaB mutants and their isogenic ΔflaG mutants). The graph on the Right is an expanded portion of the graph on the Left to show differences in the range of filament lengths of ΔflaA and ΔflaA ΔflaG. (B) Transmission electron micrographs of representative filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and mutant strains. (Scale bar, 1 μm.)

Two previous studies analyzed flagellar filament lengths in C. jejuni strain 81116 (39, 40), which is a different strain than C. jejuni 81-176 examined in this study. In one study, an 81116 flaG mutant produced elongated filaments and an in vitro interaction between FlaG and σ28 was reported (39). The authors proposed FlaG may repress σ28 activity to lower flaA transcription and FlaA flagellin levels to shorten filament length, but this hypothesis was not investigated. We compared expression of flaA and flaB in WT C. jejuni 81-176 (that was analyzed in this study) and the isogenic ΔflaG mutant by measuring levels of arylsulfatase activity from flaA::astA and flaB::astA transcriptional reporters (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). We observed no differences in flaA or flaB expression between WT and ΔflaG, but expression of each was greatly decreased in the absence of respective alternative σ factors, σ28 (ΔfliA) and σ54 (ΔrpoN), required for expression of each flagellin. Thus, FlaG did not affect flagellin gene transcription in strain 81-176 to control flagellar filament length.

Another study observed that C. jejuni 81116 increased flagellar filament lengths during growth at 42 °C in comparison to 37 °C (40). This increase in filament lengths was due to the inability of FlgM to repress σ28 activity and flaA transcription at 42 °C. However, an 81116 flaG mutant was not analyzed. We compared flagellar filament lengths of WT C. jejuni 81-176 and isogenic flaG, flgM, and flaG flgM mutants after growth at 37 °C and 42 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). We observed a 12% increase in filament length in WT C. jejuni 81-176 and ΔflgM after growth at 42 °C relative to growth at 37 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). This increase was much less than the 68% increase in filament length previously observed for a 81116 flgM mutant grown at 42 °C (40). However, deletion of flaG from WT or ΔflgM greatly increased mean filament lengths from 3.1 to 3.8 μm to over 5.2 μm in each background independent of growth temperature. These data suggest that FlaG is the primary factor that controlling filament length in C. jejuni regardless of temperature.

Levels of Cell-Associated and Secreted FlaG Are Altered in C. jejuni ΔfliS.

Because flaG is organized in an operon and likely cotranscribed via σ54- and σ28-dependent promoters with fliD and fliS and both flagellins, we analyzed FlaG, the FliD filament cap, and flagellin levels in respective mutants. Due to a high level of identity between C. jejuni FlaA and FlaB flagellins, the antisera to detect flagellins for immunoblot analysis could not differentiate the flagellins. C. jejuni flagellin levels were modestly lower in whole-cell lysates (WCLs) of ΔfliD and ΔfliS (Fig. 3A). In the absence of FliS, flagellin stability is reduced in WCLs. Reduced flagellin levels in WCLs of ΔfliD are likely due to flagellins being secreted rather than incorporated into the filament (60, 61). We observed a slight increase in cell-associated flagellins in ΔflaG relative to WT (Fig. 3A), which is consistent with longer filaments produced by ΔflaG cells (Fig. 1B). FliD levels were similar in WT C. jejuni, ΔfliS, and ΔflaG. In contrast, FlaG was present in WCLs of WT and ΔfliD cells, but absent in ΔfliS WCLs (Fig. 3A). However, FlaG levels in WCLs were restored upon complementation of ΔfliS with a plasmid expressing WT FliS or FliS-FLAG (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of FlaG levels in C. jejuni flagellar mutants. (A) Immunoblot analysis of flagellin, FliD, and FlaG levels in WCLs of WT C. jejuni and isogenic mutants lacking different genes. Specific antiserum to FlaA and FlaB flagellins (FlaAB), FliD (flagellar filament cap protein), and FlaG were used to detect specific proteins. Detection of RpoA served as a control to ensure equal loading of proteins across strains. (B) Levels of FlaG in WT C. jejuni and ΔfliS in WCLs and supernatants after growth in MH broth for 20 h in MH broth at 37 °C in microaerobic conditions. Strains contained vector alone (vec) or vector to express WT FliS (WT) or FliS-FLAG (WT-FLAG). WCL and supernatant proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antiserum for FlaG. Detection of RpoA served as a control to ensure equal loading of WCLs and absence of cytoplasmic proteins in supernatants.

We initially hypothesized that the absence of FlaG in ΔfliS was due to a requirement of FliS to bind FlaG and maintain its stability, like for flagellins. If so, FlaG might compete with flagellins for binding by FliS and lower flagellin delivery to FlhA of the fT3SS export gate, causing reduced flagellin secretion as a mechanism to control flagellar filament length. However, we observed that FlaG was secreted in WT C. jejuni and its secretion was greatly enhanced in ΔfliS (Fig. 3B). Complementation of ΔfliS with a plasmid expressing WT FliS or FliS-FLAG restored WT FlaG levels in WCLs and lowered levels of secreted FlaG compared to ΔfliS with vector alone (Fig. 3B). Our data suggest that FlaG does not require FliS for secretion by the fT3SS or stability. Therefore, FlaG unlikely competes with flagellins for binding to FliS as a mechanism to control flagellar filament length.

In T. denticola, FlaG is part of the filament, but whether FlaG incorporation into the filament is required to control filament length is unknown. Since C. jejuni FlaG is secreted presumably by the fT3SS, we analyzed whether FlaG is part of the C. jejuni flagellar filament to function as a terminator for filament polymerization. We enriched for flagellar filaments by mechanically shearing ΔflaG cells containing vector alone or a plasmid expressing WT FlaG or FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG. Immunoblot analysis of flagellar filament preparations confirmed abundant levels of flagellins and FliD (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), which is only present in four to six copies per filament (62–64). Although our filament preparations had very minor contamination of cytoplasmic RpoA, we never detected FlaG in multiple filament preparations (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Therefore, we surmised that FlaG is secreted into the extracellular environment, rather than forming a part of the flagellar filament. Our findings also suggest that FlaG may be secreted from C. jejuni by the fT3SS as a consequence of a mechanism to control filament length.

Altering Sites for FliS–Flagellin Interactions with FlhA Affect Filament Length and FlaG.

In Salmonella species, specific residues in FliS interact with defined sites on the cytoplasmic torus of FlhA in the fT3SS export gate to deliver flagellins for secretion (16). FliS in the unbound state does not interact with FlhA. Binding of flagellins causes a structural change in FliS to promote an interaction with the docking site on FlhA (15, 16). Our findings showing that FlaG is secreted from C. jejuni and secreted more abundantly in the absence of FliS suggest that FlaG also interacts with FlhA. We performed in vivo coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays to detect possible interactions between FlhA and FliS–flagellin complexes or FlaG. After recovery of FliS-FLAG from C. jejuni ΔfliS and FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG from C. jejuni ΔflaG by FLAG-affinity resin, immunoblotting analysis was performed to determine whether FlhA was present in in vivo coimmunoprecipitated complexes. We specifically detected FlhA as a part of a complex with either FliS-FLAG or FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG (Fig. 4A). These data lend further support that FlaG interacts with FlhA in a potential mechanism to control flagellar filament length and is likely secreted by the fT3SS as a consequence of this interaction with FlhA.

Fig. 4.

Effect of mutating interacting residues in FlhA and FliS on flagellar filament length and FlaG levels. (A) In vivo interactions between C. jejuni FliS or FlaG and FlhA. FliS-FLAG, FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG, or WT version of each protein without the FLAG epitope were expressed from plasmids in respective ΔfliS or ΔflaG mutants. FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated by FLAG tag antibody resin after cross-linking cells by formaldehyde. Immunoblots to detect FlhA and RpoA were performed with specific antiserum. An antibody against the FLAG epitope was used to detect FLAG-tagged FliS and FlaG. Detection of RpoA served as a negative control for a protein that does not interact with FliS or FlaG. (B) Flagellar filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and ΔfliS with vector (vec) alone, or vector to express WT FliS-FLAG, FliSY10A-FLAG, or FliSY7A Y10A N13A-FLAG. Flagellar filaments were measured from micrographs of negatively stained cells acquired by TEM. Each circle represents the length of a flagellar filament on a cell. Over 100 flagellar filaments were measured from three independent cultures (n > 300). Bar represents mean filament length. Statistical significance was calculated by the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test (*P < 0.05 between filament lengths of WT C. jejuni with vector alone and other strains; **P < 0.05 between ΔfliS complemented with WT-FliS and ΔfliS with vector alone or expressing fliS mutants). (C) Levels of FlaG, flagellins, and FliS-FLAG in WCLs or supernatants of WT C. jejuni and ΔfliS with vector (vec) alone or vector to express WT FliS-FLAG or FliSY10A-FLAG. Strains were grown for 20 h in MH broth at 37 °C in microaerobic conditions. WCL and supernatant proteins were recovered and analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antiserum for FlaG, flagellins (FlaAB), or the FLAG epitope. Detection of FlaA and FlaB flagellins are a positive control for recovery of secreted proteins in strains competent for secretion. Detection of RpoA served as a control to ensure equal loading of WCLs and absence of cytoplasmic proteins in the supernatant fraction. (D) Flagellar filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and flhA mutants with alterations of the predicted FliS binding site. Flagellar filaments were measured from micrographs of negatively stained cells acquired by TEM. Each circle represents the length of a flagellar filament on a cell. Over 100 flagellar filaments were measured from three independent cultures (n > 300). Bar represents mean filament length. Statistical significance was calculated by the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test (*P < 0.05 between filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and isogenic mutants). (E) Levels of FlaG and flagellins in whole cell lysates (WCLs) and supernatants of WT C. jejuni and isogenic ΔflaG, ΔfliS and flhA mutants with alterations in the predicted FliS binding site. Strains were grown for 20 h in MH broth at 37 °C in microaerobic conditions. WCL and supernatant proteins were recovered and analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antiserum for FlaG, flagellins (FlaAB), or RpoA. Detection of FlaA and FlaB flagellins are a positive control for recovery of secreted proteins in strains competent for secretion. Detection of RpoA served as a control to ensure equal loading of WCLs and absence of cytoplasmic proteins in the supernatant fraction.

We next investigated whether FlaG competed for the same docking sites on the FlhA torus of the fT3SS export gate as FliS, which may allow FlaG to block FliS delivery of flagellins for secretion as a mechanism to control filament length. Residues of the Salmonella FlhA torus that form a hydrophobic cleft for docking FliS via a specific region are mostly conserved in C. jejuni (16). These conserved residues in C. jejuni FliS include Y7, Y10, and N13 (corresponding to Salmonella FliS Y7, Y10, and V13, respectively) and in C. jejuni FlhA include F485, S487, V513, and T516 (corresponding to Salmonella FlhA residues F459, L461, V487, and T490, respectively; SI Appendix, Fig. S4). We hypothesized that mutation of these FliS residues would reduce interactions of FliS with FlhA to cause reduced flagellin secretion and shorter filaments. We also expected FlaG secretion to increase in these FliS mutants since reduced docking of FliS to FlhA might enhance access of FlaG to FlhA and the fT3SS export gate.

Complementation of ΔfliS with plasmids expressing FliSY10A-FLAG and FliSY7A Y10A N13A-FLAG resulted in flagellar filaments that were 0.61 to 1.31 μm shorter than WT with vector alone or ΔfliS complemented with WT FliS-FLAG (Fig. 4B). Since mutation of FliS Y10 was sufficient to reduce flagellar filament length, we examined FlaG levels in WCLs and supernatants of ΔfliS complemented with FliS-FLAG or FliSY10A-FLAG relative to WT C. jejuni. As expected, FlaG levels were lower in WCLs of ΔfliS with vector alone or expressing FliSY10A-FLAG compared to WT with vector alone or ΔfliS producing FliS-FLAG (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, we observed enhanced FlaG secretion in ΔfliS with vector alone or producing FliSY10A-FLAG (Fig. 4C). These data provided initial support that access to FlhA for FlaG increased when FliS is impaired for binding to FlhA.

If FliS and FlaG bind the same docking sites on FlhA, we hypothesized that mutation of these residues on the FlhA torus would reduce filament length (due to reduced FliS docking and delivery of flagellins to FlhA and the fT3SS export gate), while also causing accumulation of FlaG in WCLs and decreased secretion of FlaG (due to weaker FlaG docking to the same sites on FlhA as FliS). Replacement of WT flhA on the C. jejuni chromosome with flhAF485A, flhAV513G, or flhAT516M, but not flhAS487A, resulted in C. jejuni producing up to 0.73 μm shorter flagellar filaments than WT C. jejuni (Fig. 4D). A flhAF485A V513G double mutant produced even shorter flagellar filaments, which were 1.15 μm shorter than WT C. jejuni (Fig. 4D). These data support that FlhA F485, V513, and T516 are likely interaction sites for FliS–flagellin complexes, similar to Salmonella FlhA (16). When we analyzed FlaG levels in WCLs and supernatants of C. jejuni flhAF485A, flhAV513G, and flhAF485A V513G mutants, we acquired data contradictory to our hypotheses. Instead of FlaG accumulating in WCLs due to less FlaG secreted from the flhA mutants, we observed similar levels of FlaG in WCLs of WT and flhA mutants (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, FlaG secretion was not reduced, but enhanced from flhAF485A and flhAF485A V513G mutants relative to WT, like in ΔfliS (Fig. 4E). These data suggest that if FlaG interacts with the FlhA torus to antagonize FliS–flagellin complexes to bind the fT3SS export gate, FlaG does not compete with FliS for the same docking site on FlhA. Instead, FlaG may interact with an alternative site on the FlhA torus to control filament length and consequently be secreted from the cell.

Evidence for FlaG Targeting a Different Site on FlhA to Antagonize FliS–FlhA Interactions to Control Filament Length.

We explored alternative binding sites for FlaG on the FlhA torus using AlphaFold 3 (52). This tool predicted that the C-terminal six residues of FlaG (residues 116 to 121) form a β-strand that interacts with a conserved β-strand composed by residues 431 through 439 of FlhA (Fig. 5 A and C). This IRIRDNLRL sequence in the FlhA torus is conserved in multiple FlhA proteins from both polar and peritrichous flagellates (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This structural model also predicted FliS Y10 in close proximity to FlhA residues F485, V513, and T516, which caused a shortening of C. jejuni flagellar filaments when mutated (Figs. 4 B and D and 5B). If this model is correct, FlaG bound to one monomer of the torus may overlap or occupy a similar space as FliS–flagellin complexes docked to the monomer in the clockwise position of the FlhA torus (Fig. 5 A–C). If so, FlaG may hinder docking of FliS–flagellin complexes to FlhA for delivery flagellins to the fT3SS export gate for secretion and filament polymerization as a means to control flagellar filament length. To test whether the IRIRDNLRL motif from 431 to 439 of FlhA is involved in controlling filament length as a potential binding site for FlaG action, we created a series of flhA mutants in which pairs of residues in this motif were altered (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Replacement of WT flhA with flhAK430A I433A, flhAR432A D435A, flhAR434A L437A, or flhAN436A L439A all caused significant elongation of flagellar filaments, with means ranging from 3.73 to 5.07 μm compared to 3.2 μm for WT C. jejuni (Fig. 5D). This increased filament length produced by the flhAR434A L437A or flhAN436A L439A mutants (4.9 and 5.07 μm, respectively) was comparable to that of ΔflaG (4.82 μm). Furthermore, we observed FlaG accumulation in WCLs of three of the flhA mutants selected for further analysis, and these mutants showed a mild to severe reduction in its secretion (Fig. 5E). These findings support that FlaG may interact with this identified region of the FlhA torus to function in a mechanism to control filament length.

Fig. 5.

Effect of altering predicted FlhA–FlaG interactions on flagellar filament lengths and FlaG. (A–C) Cartoon representation of the predicted interactions by AlphaFold 3 of (A) FliS and FlaG with the FlhA nonamer forming the torus region, (B) FliS with an FlhA torus monomer, and (C) FlaG with an FlhA torus monomer. For (A–C), each C. jejuni FlhA monomer of the torus (residues 389 to 724) is represented by one of three shades of gray. The positions of the N terminus of the FlhA torus (K389) connected to the linker region of FlhA and the C terminus of the protein are indicated. The β-strand of FlhA from resides I431 through L439 (composed of IRIRDNLRL) that is the predicted interaction site for the C-terminal β-strand of FlaG (purple) is shown in yellow. Due to predicted flexibility of the N-terminal region of FlaG, only residues G40 through the C terminus of FlaG are shown. FliS is indicated in pink with teal representing Y10 that is predicted to interact with residues F485, S487, V513, and T516 (shown in red) of the FlhA torus. (D) Flagellar filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and ΔflaG containing WT flhA or flhA mutations in the predicted binding site for FlaG. Flagellar filaments were measured from micrographs of negatively stained cells acquired by TEM. Each circle represents the length of a flagellar filament on a cell. Over 100 flagellar filaments were measured from three independent cultures (n > 300). Bar represents mean filament length. Statistical significance was calculated by the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test (*P < 0.05 between filament lengths of WT C. jejuni and other strains). (E) Levels of FlaG and flagellins in WCLs or supernatants of WT C. jejuni and isogenic ΔflaG and flhA mutants with alterations of the predicted FliS binding site. Strains were grown for 20 h in MH broth at 37 °C in microaerobic conditions. WCLs and supernatant proteins were recovered and analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antiserum for FlaG, flagellins (FlaAB), or RpoA. Detection of FlaA and FlaB flagellins are a positive control for recovery of secreted proteins. Detection of RpoA served as a control to ensure equal loading of WCLs and absence of cytoplasmic proteins in the supernatant fraction.

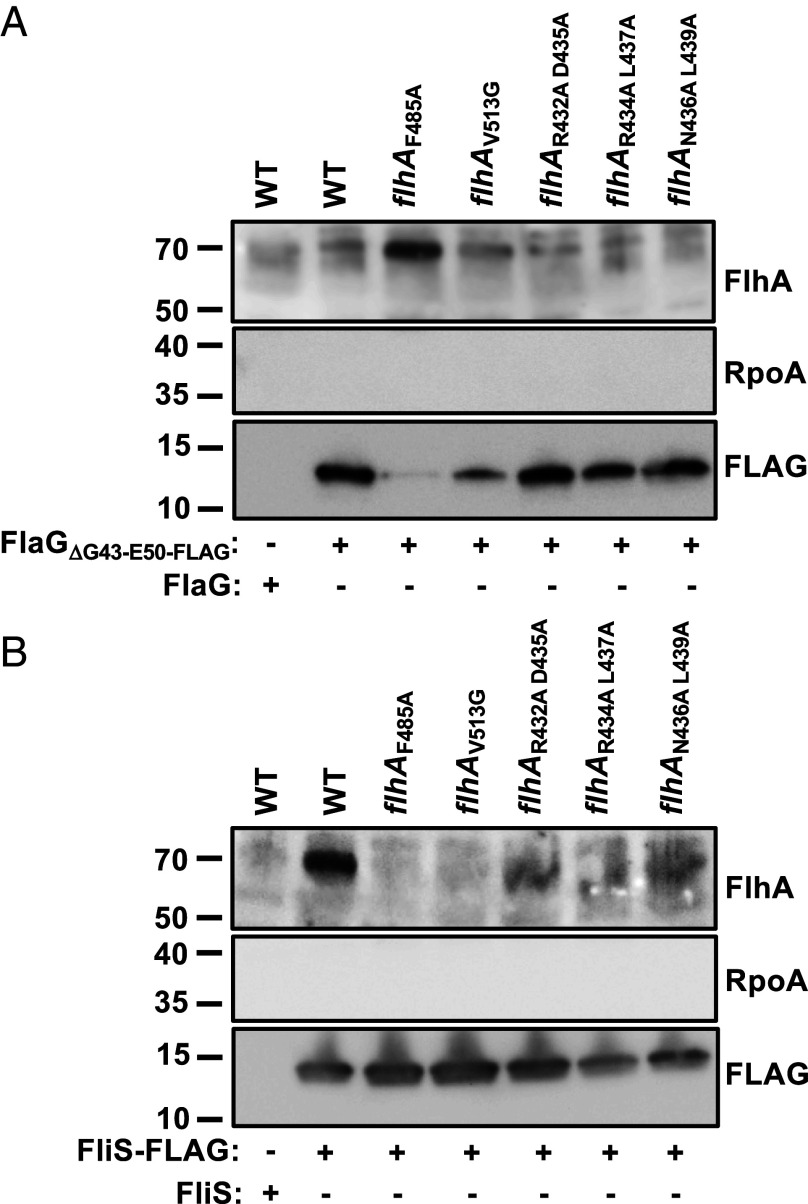

If two different binding sites for FliS–flagellin complexes and FlaG exist on the FlhA torus, and mutation of each FlhA binding site caused opposite effects on flagellar filament length and FlaG secretion, we hypothesized that FlaG and FliS may antagonize each other for binding to their respective sites on adjacent monomers of the FlhA torus. Thus, alteration of the FliS-binding sites may allow for increased interactions of FlaG with FlhA, and vice versa. Therefore, we compared in vivo interactions of FliS and FlaG in C. jejuni cells with WT and select FlhA mutants by co-IP assays. Upon recovery of FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG from WT or flhAF485A and flhAV513G mutants that altered the proposed FliS binding site, we noted a great decrease in the recovery of FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG from these mutants (Fig. 6A). This decrease in cellular FlaG was due to enhanced FlaG secretion from these mutants, especially flhAF485A, compared to WT C. jejuni (Figs. 4C and 6A). Despite lower retention of FlaG in these two FlhA mutants, we observed a disproportionate increased level of FlhA that coimmunoprecipitated with FlaG from these mutants compared to WT C. jejuni (Fig. 6A). This increased interaction with FlhA was especially prominent with C. jejuni flhAF485A, which had one of the most severe reductions in flagellar filament lengths among the FlhA FliS-binding mutants (Fig. 4B). We attempted to build a strain for co-IP assays in the flhAF485A V513G background that produced the shortest filaments among the FlhA mutants, but flhAF485A V513G spontaneously acquired multiple mutations or insertions in its sequence when we disrupted flaG or fliS. The amount of FlhAR432A D435A, FlhAR434A L437A, and FlhAN436A L439A, which have alterations in the predicted FlaG binding site, which coimmunoprecipitated with FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG tended to be lower than WT FlhA, especially FlhAN436A L439A. If these mutants are impaired for binding FlaG, then flagellar filaments should not further increase in length when flaG is mutated in these strains. Indeed, disruption of flaG in these flhA mutants did not further elongate flagellar filament lengths (Fig. 5D). These data are consistent with the IRIRDNLRL motif of the FlhA torus being a site for FlaG interactions so that FlaG executes a control mechanism to limit flagellin delivery by FliS and filament length.

Fig. 6.

In vivo interactions of FlaG and FliS with WT FlhA and FlhA binding site mutants. (A and B) In vivo interactions between C. jejuni (A) FlaG or (B) FliS and WT FlhA or FlhA mutants with alterations at residues predicted for interactions with FliS or FlaG. C. jejuni FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG, FliS-FLAG, or WT version of each protein without the FLAG epitope were expressed from plasmids in respective ΔflaG or ΔfliS mutants as indicated below immunoblots. FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated by FLAG tag antibody resin after cross-linking cells by formaldehyde. Immunoblots to detect FlhA and RpoA were performed with specific antiserum. An antibody against the FLAG epitope was used to detect FLAG-tagged FliS and FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG. Detection of RpoA served as a negative control for a protein that does not interact with FlaG or FliS. The presence of WT flhA or each flhA mutant on the chromosome is indicated above blots. FlhAF485A and FlhAV513G contain mutations predicted to disrupt interactions with FliS–flagellin complexes. FlhAR432A D435A, FlhAR434A L437A, and FlhAN436A L439A contain mutations predicted to disrupt interactions with FlaG.

We next analyzed how FliS–FlhA interactions change in FlhA mutants altered at the predicted FliS or FlaG binding sites. As expected, we found WT FlhA, but not FlhAF485A or FlhAV513G in in vivo coimmunoprecipitated complexes with FliS-FLAG (Fig. 6B), which is consistent with these mutants having alterations at the docking site for FliS–flagellin complexes. The severe reduction in an interaction between FliS and these FlhA mutants is consistent with the decreased flagellar filament lengths produced by these mutants (Fig. 4D). As expected, FliS-FLAG continued to interact well with FlhAR432A D435A, FlhAR434A L437A, and FlhAN436A L439A, which have mutations at the predicted FlaG binding site. These data support that FlaG and FliS–flagellin bind to two different sites on monomers of the FlhA torus and likely antagonize each other for access to FlhA. We propose that when FliS–flagellin complexes decrease during filament polymerization, FlaG gains access to FlhA to reduce flagellin delivery by FliS to the fT3SS export gate to limit flagellin secretion and length of flagellar filaments in C. jejuni.

Discussion

Bacteria produce many types of surface structures and organelles such as LPS, pili, and capsular polysaccharides. Biosynthetic pathways for these structures often have mechanisms to terminate their synthesis, either stochastically or when the structures reach a defined length (65–70). Whether mechanisms exist to precisely regulate flagellar filament length has not been intensely investigated. In contrast to previously identified passive mechanisms that influence filament length such as the amount of flagellins produced in a bacterial cell or the efficiency of flagellins to diffuse to the tip of the filament for incorporation (35–37), we revealed insights into a mechanism for how FlaG actively limits filament length in polarly flagellated bacteria. We found that C. jejuni FlaG interacts with a conserved, understudied site on the FlhA torus of the fT3SS export gate. This site is different than the docking site for FliS–flagellin complexes on the FlhA torus for delivery of flagellins to the fT3SS export gate. Our data suggest FlaG and FliS–flagellin complexes antagonize each other for interactions with FlhA. This antagonism during filament synthesis presumably allows FlaG to gradually access FlhA and lower the ability of FliS to deliver flagellins to the fT3SS export gate to shut down filament biosynthesis so that C. jejuni produces a normally short filament. Although peritrichous bacteria conserve the FlaG-binding site on the FlhA torus, they lack FlaG and this mechanism to finely control flagellar filament lengths to the shorter dimensions of many polarly flagellated bacteria.

Our data support that FlaG and FliS-loaded flagellins antagonize each other to interact with the FlhA torus (Fig. 7). FlhA forms a nonamer in the fT3SS export gate with each monomer in the torus having a FliS- and FlaG-binding site (10, 11). Currently, we do not know the precise mechanism of this antagonism. If the structural model is correct (Fig. 5 A–C), FlaG and FliS occupy a similar space when binding to adjacent FlhA torus monomers. Thus, binding of FlaG to one monomer in the FlhA torus could sterically hinder the ability of a FliS–flagellin complex to interact with the monomer in the adjacent clockwise position. However, we cannot rule out an allosteric mechanism with FlaG binding to one monomer lowering the affinity of another monomer to interact with a FliS–flagellin complex, and vice versa. One limitation of the model proposed by AlphaFold 3 is that the N-terminal region of FlaG may be flexible, which limited confidence in predicting its location when bound to the FlhA torus. In vitro reconstitution of the FlhA torus and fine biophysical experiments to measure binding affinity and kinetics with FlaG alone, FliS–flagellin complexes alone, and in the presence of both will likely contribute to the mechanism of antagonism between these proteins.

Fig. 7.

Proposed model for FlaG antagonism of FliS–flagellin complex interactions with FlhA to control flagellar filament length in C. jejuni. Upon completion of the rod and hook of the C. jejuni flagellum and the start of filament polymerization (Left), a bolus of FliS–flagellin complexes (FliS, pink circles; flagellin, blue ovals) likely dominate occupancy of FlhA torus monomers (yellow wedges) in the fT3SS export gate to antagonize the ability of FlaG (purple hexagons) to bind to the FlhA torus. Binding of a FliS–flagellin complex to a FlhA monomer may antagonize FlaG to bind to the FlhA monomer in the counterclockwise position in the torus. Likewise, binding of FlaG to a FlhA monomer may antagonize FliS–flagellin complexes to bind to the FlhA monomer in the clockwise position in the torus. During this initial filament polymerization phase, the limited amount of free flagellin allows FliW (green arcs) to bind to CsrA (black rectangle) to derepress translation of the mRNA for the major flaA flagellin. During filament elongation (Right), a gradual reduction in FliS–flagellin complexes likely increases the ability of FlaG to access FlhA and bind multiple torus monomers and antagonize binding of FliS–flagellin complexes to FlhA. The resulting accumulation of cytoplasmic flagellins may contribute to a partner-switching mechanism in which binding of cytoplasmic flagellin by FliW releases CsrA to inhibit translation of flaA mRNA, blocking further production of flagellin. The combination of FlaG-dependent antagonism preventing FlhA and FliS–flagellin complex interactions and the resulting CsrA-mediated translation inhibition of flagellin may reinforce each other to allow FlaG to control flagellar filament length, resulting in shorter flagellar filaments.

Our finding for FlaG negatively impacting the C. jejuni fT3SS to receive and secrete flagellins is similar to the function of gatekeepers in the evolutionarily related injectisome type III secretion systems (iT3SS) of many bacterial pathogens. SctW orthologs including MxiC, SsaL, YopN, SepL, and BopN have gatekeeping functions that prevent premature secretion of translocator and effector proteins before the iT3SS needle is made or host cell contact occurs (71, 72). Gatekeepers lose their function upon an activation signal, which is usually when the iT3SS contacts a target cell that causes a change in pH or specific ion concentrations in the bacterium (73–77). Like FlaG, gatekeepers target the FlhA ortholog SctV in the iT3SS. Some gatekeepers function analogous to our proposed mechanism for FlaG by blocking access of translocator- or effector-loaded chaperones to SctV (78). Other gatekeepers function by forming a plug in the SctV torus (79, 80) or lowering the affinity of SctV for chaperone–effector complexes (81). Modes to eliminate gatekeeper activity when host cell contact occurs include its dissociation from SctV (82), degradation (73), or secretion (75, 83–85).

Like translocators and effectors for iT3SSs, flagellins are the terminal secretion substrates for fT3SSs. Gatekeepers have highest activity to block secretion of iT3SS translocators or effectors before the activation signal of host cell contact. However, FlaG is unlikely to have highest activity before filament synthesis. If it did, it is unlikely flagellins could be secreted to form the filament. A striking feature of FlaG activity is its precision in confining C. jejuni flagellar filaments lengths to such a limited range (within 0.47 μm from the mean filament length of the population) compared to the lack of strict filament length control of peritrichous bacteria. C. jejuni FlaG would seem to be most active after secretion of flagellins has begun and the filament reaches ~3 μm. One simple possibility for FlaG maintaining such fine control of filament length may be linked to the level of flagellin and FliS–flagellin complexes present at the end of hook synthesis and the onset of filament polymerization. This initial level of intracellular flagellin and FliS–flagellin complexes may dominate FlaG for access to FlhA. Delivery and secretion of this large amount of flagellins during the first stages of filament polymerization may be sufficient to synthesize a filament of ~3 μm. At this point, a natural drop in intracellular FliS–flagellin complexes may give FlaG an advantage over FliS for access to FlhA to then antagonize further flagellin delivery to FlhA and the fT3SS. Thus, a signal for FlaG to promote its activation to curb flagellin delivery to the fT3SS could be tied to the amount of flagellin in the cell and the change in flagellin levels once filament polymerization begins.

Our finding that FlaG is ultimately secreted by the fT3SS would seemingly attenuate the ability of FlaG to continue to antagonize FliS delivery of flagellins to the fT3SS export gate to maintain shorter filament lengths. A drop in cytoplasmic FlaG levels due to its secretion could allow FliS–flagellin complexes to resume access to FlhA to secrete flagellins and further elongate the filament. We suspect that the mechanism of action for FlaG to limit flagellin delivery to the C. jejuni fT3SS export gate is linked to a known mechanism that posttranscriptionally controls flagellin levels during flagellar biogenesis, which may allow FlaG to continue maintaining filament lengths even though it is secreted. The CsrA-FliW system functions to inhibit translation of C. jejuni flaA mRNA when flagellins accumulate in the cytoplasm so that the bacterial cell only produces the flagellin necessary to build a filament (61, 86–88). As identified in Bacillus subtilis and verified in C. jejuni, the FliW protein is the major antagonist for B. subtilis and C. jejuni CsrA to bind flagellin mRNA. FliW toggles between a flagellin-bound form that frees CsrA to inhibit flagellin mRNA translation and flagellin synthesis and a CsrA-bound form to derepress flagellin mRNA translation and augments flagellin production [Fig. 7; (89–93)]. The loss of a large bolus of flagellins from the cytoplasm at the onset of filament polymerization due to their secretion could change FlaG activity and the CsrA-FliW network to reinforce each other in controlling filament length and flagellin production (Fig. 7). With decreasing FliS–flagellin complexes as the filament is made, FlaG likely gains access to FlhA to antagonize further binding of FliS–flagellin complexes. The resulting accumulation of cytoplasmic flagellin could shift FliW from binding CsrA to binding flagellin, thereby allowing CsrA to inhibit translation of flagellin mRNA to decrease flagellin production (Fig. 7). A decrease in flagellin production and FliS–flagellin complexes would continue to strengthen FlaG to antagonize flagellin delivery and secretion.

Considering that flaG is transcribed from both σ28- and σ54-dependent promoters, FlaG is transcribed simultaneously with both flagellins. However, unlike flagellins, evidence for translational control of FlaG production is lacking. Thus, FlaG could be replenished during filament synthesis as it is secreted whereas flagellin translation may decrease with filament polymerization. Since there are only one or two flagella per a cell, a sufficient level of cytoplasmic FlaG may be consistently produced to occupy the nine monomers in the FlhA torus of the fT3SS export gate to antagonize a very low number of FliS–flagellin complexes at the end of filament synthesis. If FlaG and CsrA-FliW system are intertwined in this way, these mechanisms would allow C. jejuni to maintain production of a relatively short flagellar filament.

Other polar flagellates like V. cholerae and P. aeruginosa do not produce FliW (93). Thus, it is unclear whether FlaG activity in other polarly flagellated bacteria may be connected to a mechanism to limit flagellin production during the latter stages of filament elongation to reinforce its ability to maintain shorter filament lengths. However, if FlaG is not secreted from these bacteria, then FlaG could function as an antagonist independent of a mechanism to inhibit flagellin production once flagellins and FliS–flagellin complexes drop below a critical threshold in the cytoplasm during filament elongation.

One observation we made is that altering the binding sites for FliS on FlhA appeared to greatly enhance the ability of FlaG to interact with FlhA and be secreted. Similarly, the absence of FliS also greatly augmented FlaG secretion to suggest increased FlaG–FlhA interactions. However, mutation of the binding sites for FlaG on FlhA did not strongly reciprocate augmentation of FliS binding to FlhA. FliS binding to FlhA is dependent on it binding flagellins, whose level change depending on the stage of flagellar biogenesis. Thus, detection of enhanced interactions between FliS and FlhA with reduced FlaG binding may occur within a limited time period during flagellar biogenesis. Also, we likely have not yet created a completely null FlaG-binding mutant of FlhA. Further interrogation of the FlaG–FlhA interaction should lead to such a mutant that would allow us to better examine how FlaG and FliS influence each other for access to FlhA. We attempted to make a flaG fliS double mutant to express FLAG-tagged FliS or FlaG for in vivo interaction studies to better measure how interactions with FlhA change in the complete absence of the other protein. However, we could not make this double mutant without spontaneous mutations occurring that eliminated flagellar biosynthesis. In addition, an inducible system to finely control production of FliS and FlaG would help to examine how increasing levels of one influence antagonism of these proteins for FlhA interactions. Unfortunately, an optimized inducible system for this type of analysis is lacking in C. jejuni.

We showed in this work that FlaG is a major determinant controlling flagellar filament length in C. jejuni. FlaG controls flagellar filament length in another strain, C. jejuni 81116 (39). In this strain, growth at 42 °C caused a large increase in filament lengths (40). This increase was due to a thermo-sensitive σ28–FlgM interaction in which FlgM loses its ability to repress σ28 activity at higher temperature causing an increase in transcription of flaA encoding the major flagellin. We only observed a very mild increase in flagellar filament length in the strain we used in this study, C. jejuni 81-176, but flagellar filament length did not increase with temperature in our ΔflaG mutant. It is possible that there are strain-specific differences in regulating flagellar filament length in C. jejuni, with some strains solely possessing a FlaG-dependent mechanism and others possessing both a FlaG- and temperature-dependent mechanism. For those strains with both mechanisms, it is unknown whether temperature impacts FlaG activity.

A fundamental question remains—why do polarly flagellated bacteria conserve FlaG for a mechanism to produce short flagellar filaments? Evolution of FlaG in these bacteria to confine flagellar filaments to shorter lengths than peritrichous bacteria is expected to provide some type of advantage. In two reports of a C. jejuni flaG mutant, production of elongated filaments caused a mild swimming motility defect and significantly hindered biofilm formation (39, 44). The reduction in biofilm formation may be due to elongated filaments preventing close interactions between bacterial cells for transitioning to the biofilm state. Thus, shorter filaments seem to improve flagellar motility and biofilm formation for C. jejuni.

Another possible benefit for producing shorter filaments is to curb a TLR5-dependent innate immune response to extracellular flagellin subunits during infection of hosts. Flagellins are agonist for TLR5, which recognizes a highly conserved epitope of flagellin required for flagellin subunit interactions to polymerize the filament (94, 95). Indeed, V. cholerae and P. aeruginosa, which we show in this work employ FlaG to limit flagellar filament length, produce flagellins that stimulate TLR5 and activate NF-κB to induce innate immune responses (96–98). However, C. jejuni flagellins are poor agonists for TLR5 during infection of avian hosts or in in vitro models of infection of human or avian immune cells (99–102). This is due to C. jejuni flagellin, like H. pylori flagellin, lacking the conserved epitope for TLR5 recognition and altering flagellin subdomains for flagellin interactions to polymerize the filament (96, 103). Therefore, for C. jejuni and H. pylori, limiting filament polymerization to reduce extracellular flagellins and attenuate an innate immune response via TLR5 is presumably not the primary advantage for maintaining FlaG-dependent control of flagellar filament length. It is possible that in hosts, production of shorter flagellar filaments due to FlaG may facilitate optimal colonization. Production of short, WT filament lengths may aid navigation through the intestinal tract to reach ideal lower intestinal niches for colonization or conserve resources by limiting the number of flagellins required to construct a functional flagellar motor and filament. We are currently examining whether production of shorter, WT length, or longer filaments by C. jejuni flaG and flhA mutants generated in this work significantly hinder C. jejuni to colonize and thrive in the avian host.

Materials and Methods

Materials and methods describing the growth conditions of strains, plasmid construction, bacterial mutant construction, TEM, co-IP assays, immunoblotting, arylsulfatase assays, flagellar filament preparations, antisera production, and protein structural predictions are described in detail in SI Appendix. All bacterial strains and plasmids constructed and used in this work are included in SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2, respectively. All use of animals in experimentation has been approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health NIH grants R21AI159140 and R01AI065539. We thank the laboratory of Dr. Morgan Beeby and specifically Dr. Trishant Umrekar for advice on preparing flagellar filaments from C. jejuni cells. We also thank Dr. Pengfei Ding for suggestions in constructing FlaGΔG43-E50-FLAG.

Author contributions

A.A.W. and D.R.H. designed research; A.A.W., D.A.R., and D.R.H. performed research; A.A.W., D.A.R., and D.R.H. analyzed data; and A.A.W. and D.R.H. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All strains and plasmids generated in this report will be made promptly available to readers. All other data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Minamino T., Kinoshita M., Structure, assembly, and function of flagella responsible for bacterial locomotion. EcoSal Plus 11, eesp00112023 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macnab R. M., How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57, 77–100 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhlen L., et al. , Structure of the core of the type III secretion system export apparatus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 583–590 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhlen L., et al. , The substrate specificity switch FlhB assembles onto the export gate to regulate type three secretion. Nat. Commun. 11, 1296 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser G. M., et al. , Substrate specificity of type III flagellar protein export in Salmonella is controlled by subdomain interactions in FlhB. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 1043–1057 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris H. U., et al. , FlhB regulates ordered export of flagellar components via autocleavage mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41236–41242 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minamino T., Macnab R. M., Domain structure of Salmonella FlhB, a flagellar export component responsible for substrate specificity switching. J. Bacteriol. 182, 4906–4914 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minamino T., Morimoto Y. V., Hara N., Aldridge P. D., Namba K., The bacterial rlagellar type III export gate complex is a dual fuel engine that can use both H+ and Na+ for flagellar protein export PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005495 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minamino T., Morimoto Y. V., Kinoshita M., Namba K., Membrane voltage-dependent activation mechanism of the bacterial flagellar protein export apparatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2026587118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrusci P., et al. , Architecture of the major component of the type III secretion system export apparatus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 99–104 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhlen L., Johnson S., Cao J., Deme J. C., Lea S. M., Nonameric structures of the cytoplasmic domain of FlhA and SctV in the context of the full-length protein. PLoS One 16, e0252800 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bange G., et al. , FlhA provides the adaptor for coordinated delivery of late flagella building blocks to the type III secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11295–11300 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinoshita M., Hara N., Imada K., Namba K., Minamino T., Interactions of bacterial flagellar chaperone-substrate complexes with FlhA contribute to co-ordinating assembly of the flagellar filament. Mol. Microbiol. 90, 1249–1261 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minamino T., et al. , Interaction of a bacterial flagellar chaperone FlgN with FlhA is required for efficient export of its cognate substrates. Mol. Microbiol. 83, 775–788 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanra N., Rossi P., Economou A., Kalodimos C. G., Recognition and targeting mechanisms by chaperones in flagellum assembly and operation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 9798–9803 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xing Q., et al. , Structures of chaperone-substrate complexes docked onto the export gate in a type III secretion system. Nat. Commun. 9, 1773 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chevance F. F., Hughes K. T., Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 455–465 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minamino T., Macnab R. M., Components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and classification of export substrates. J. Bacteriol. 181, 1388–1394 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H., Sourjik V., Assembly and stability of flagellar motor in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 886–899 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iino T., Polarity of flagellar growth in Salmonella. J. Gen. Microbiol. 56, 227–239 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirano T., Minamino T., Macnab R. M., The role in flagellar rod assembly of the N-terminal domain of Salmonella FlgJ, a flagellum-specific muramidase. J. Mol. Biol. 312, 359–369 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chevance F. F., et al. , The mechanism of outer membrane penetration by the eubacterial flagellum and implications for spirochete evolution. Genes Dev. 21, 2326–2335 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen E. J., Hughes K. T., Rod-to-hook transition for extracellular flagellum assembly is catalyzed by the L-ring-dependent rod scaffold removal. J. Bacteriol. 196, 2387–2395 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohnishi K., Ohto Y., Aizawa S., Macnab R. M., Iino T., FlgD is a scaffolding protein needed for flagellar hook assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 176, 2272–2281 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erhardt M., et al. , The role of the FliK molecular ruler in hook-length control in Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1272–1284 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erhardt M., Singer H. M., Wee D. H., Keener J. P., Hughes K. T., An infrequent molecular ruler controls flagellar hook length in Salmonella enterica. EMBO J. 30, 2948–2961 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minamino T., Moriya N., Hirano T., Hughes K. T., Namba K., Interaction of FliK with the bacterial flagellar hook is required for efficient export specificity switching. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 239–251 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minamino T., Ferris H. U., Moriya N., Kihara M., Namba K., Two parts of the T3S4 domain of the hook-length control protein FliK are essential for the substrate specificity switching of the flagellar type III export apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 362, 1148–1158 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shibata S., et al. , FliK regulates flagellar hook length as an internal ruler. Mol. Microbiol. 64, 1404–1415 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi N., et al. , Autonomous and FliK-dependent length control of the flagellar rod in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 191, 6469–6472 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minamino T., Inoue Y., Kinoshita M., Namba K., FliK-driven Conformational rearrangements of FlhA and FlhB are required for export switching of the flagellar protein export apparatus. J. Bacteriol. 202, e00637-19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchida K., Aizawa S., The flagellar soluble protein FliK determines the minimal length of the hook in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 196, 1753–1758 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikeda T., Yamaguchi S., Hotani H., Flagellar growth in a filament-less Salmonella fliD mutant supplemented with purified hook-associated protein 2. J. Biochem. 114, 39–44 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yonekura K., et al. , The bacterial flagellar cap as the rotary promoter of flagellin self-assembly. Science 290, 2148–2152 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Z., et al. , Frequent pauses in Escherichia coli flagella elongation revealed by single cell real-time fluorescence imaging. Nat. Commun. 9, 1885 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renault T. T., et al. , Bacterial flagella grow through an injection-diffusion mechanism. Elife 6, e23136 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen M., et al. , Length-dependent flagellar growth of Vibrio alginolyticus revealed by real time fluorescent imaging. Elife 6, e23126 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaguchi T., et al. , Structural and functional comparison of Salmonella flagellar filaments composed of FljB and FliC. Biomolecules 10, 246 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue T., Barker C. S., Matsunami H., Aizawa S. I., Samatey F. A., The FlaG regulator is involved in length control of the polar flagella of Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiology 164, 740–750 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wosten M. M., et al. , Temperature-dependent FlgM/FliA complex formation regulates Campylobacter jejuni flagella length. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1577–1591 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Contreras M., et al. , Phenotypic selection and phase variation occur during alfalfa root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens F113. J. Bacteriol. 184, 1587–1596 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGee K., Horstedt P., Milton D. L., Identification and characterization of additional flagellin genes from Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 178, 5188–5198 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capdevila S., Martinez-Granero F. M., Sanchez-Contreras M., Rivilla R., Martin M., Analysis of Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 genes implicated in flagellar filament synthesis and their role in competitive root colonization. Microbiology 150, 3889–3897 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalmokoff M., et al. , Proteomic analysis of Campylobacter jejuni 11168 biofilms reveals a role for the motility complex in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4312–4320 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurniyati K., Liu J., Zhang J. R., Min Y., Li C., A pleiotropic role of FlaG in regulating the cell morphogenesis and flagellar homeostasis at the cell poles of of Treponema denticola. Cell Microbiol. 21, e12886 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Black R. E., Levine M. M., Clements M. L., Hughes T. P., Blaser M. J., Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 157, 472–479 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindblom G.-B., Sjorgren E., Kaijser B., Natural campylobacter colonization in chickens raised under different environmental conditions. J. Hyg. (Lond) 96, 385–391 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pokamunski S., Kass N., Borochovich E., Marantz B., Rogol M., Incidence of Campylobacter spp. in broiler flocks monitored from hatching to slaughter. Avian Pathol. 15, 83–92 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nachamkin I., Yang X.-H., Stern N. J., Role of Campylobacter jejuni flagella as colonization factors for three-day-old chicks: Analysis with flagellar mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 1269–1273 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wassenaar T. M., van der Zeijst B. A. M., Ayling R., Newell D. G., Colonization of chicks by motility mutants of Campylobacter jejuni demonstrates the importance of flagellin A expression. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139, 1171–1175 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hendrixson D. R., DiRita V. J., Identification of Campylobacter jejuni genes involved in commensal colonization of the chick gastrointestinal tract. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 471–484 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abramson J., et al. , Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Logan S. M., Trust T. J., Guerry P., Evidence for posttranslational modification and gene duplication of Campylobacter flagellin. J. Bacteriol. 171, 3031–3038 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guerry P., Logan S. M., Thornton S., Trust T. J., Genomic organization and expression of Campylobacter flagellin genes. J. Bacteriol. 172, 1853–1860 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guerry P., Alm R. A., Power M. E., Logan S. M., Trust T. J., Role of two flagellin genes in Campylobacter motility. J. Bacteriol. 173, 4757–4764 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carrillo C. D., et al. , Genome-wide expression analyses of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168 reveals coordinate regulation of motility and virulence by flhA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20327–20338 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hendrixson D. R., DiRita V. J., Transcription of σ54-dependent but not σ28-dependent flagellar genes in Campylobacter jejuni is associated with formation of the flagellar secretory apparatus. Mol. Microbiol. 50, 687–702 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hendrixson D. R., Akerley B. J., DiRita V. J., Transposon mutagenesis of Campylobacter jejuni identifies a bipartite energy taxis system required for motility. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 214–224 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wosten M. M. S. M., Wagenaar J. A., van Putten J. P. M., The FlgS/FlgR two-component signal transduction system regulates the fla regulon in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16214–16222 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barrero-Tobon A. M., Hendrixson D. R., Flagellar biosynthesis exerts temporal regulation of secretion of specific Campylobacter jejuni colonization and virulence determinants. Mol. Microbiol. 93, 957–974 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Radomska K. A., Ordonez S. R., Wosten M. M., Wagenaar J. A., van Putten J. P., Feedback control of Campylobacter jejuni flagellin levels through reciprocal binding of FliW to flagellin and the global regulator CsrA. Mol. Microbiol. 102, 207–220 (2016), 10.1111/mmi.13455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ikeda T., Oosawa K., Hotani H., Self-assembly of the filament capping protein, FliD, of bacterial flagella into an annular structure. J. Mol. Biol. 259, 679–686 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Postel S., et al. , Bacterial flagellar capping proteins adopt diverse oligomeric states. Elife 5, e18857 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cho S. Y., et al. , Tetrameric structure of the flagellar cap protein FliD from Serratia marcescens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 489, 63–69 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramirez A. S., et al. , Structural basis of the molecular ruler mechanism of a bacterial glycosyltransferase. Nat. Commun. 9, 445 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verger D., Miller E., Remaut H., Waksman G., Hultgren S., Molecular mechanism of P pilus termination in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. EMBO Rep. 7, 1228–1232 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clarke B. R., et al. , In vitro reconstruction of the chain termination reaction in biosynthesis of the Escherichia coli O9a O-polysaccharide: The chain-length regulator, WbdD, catalyzes the addition of methyl phosphate to the non-reducing terminus of the growing glycan. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 41391–41401 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hagelueken G., et al. , A coiled-coil domain acts as a molecular ruler to regulate O-antigen chain length in lipopolysaccharide. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 50–56 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hagelueken G., et al. , Structure of WbdD: A bifunctional kinase and methyltransferase that regulates the chain length of the O antigen in Escherichia coli O9a. Mol. Microbiol. 86, 730–742 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Islam S. T., Lam J. S., Synthesis of bacterial polysaccharides via the Wzx/Wzy-dependent pathway. Can. J. Microbiol. 60, 697–716 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manisha Y., Srinivasan M., Jobichen C., Rosenshine I., Sivaraman J., Sensing for survival: Specialised regulatory mechanisms of Type III secretion systems in Gram-negative pathogens. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 99, 837–863 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Diepold A., Wagner S., Assembly of the bacterial type III secretion machinery. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 802–822 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu X. J., McGourty K., Liu M., Unsworth K. E., Holden D. W., pH sensing by intracellular Salmonella induces effector translocation. Science 328, 1040–1043 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deng W., et al. , Regulation of type III secretion hierarchy of translocators and effectors in attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Infect. Immun. 73, 2135–2146 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Navarrete K. M., et al. , BopN is a gatekeeper of the Bordetella type III secretion system. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0411222 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Forsberg A., Viitanen A. M., Skurnik M., Wolf-Watz H., The surface-located YopN protein is involved in calcium signal transduction in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 5, 977–986 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosqvist R., Magnusson K. E., Wolf-Watz H., Target cell contact triggers expression and polarized transfer of Yersinia YopE cytotoxin into mammalian cells. EMBO J. 13, 964–972 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Matthews-Palmer T. R. S., et al. , Structure of the cytoplasmic domain of SctV (SsaV) from the Salmonella SPI-2 injectisome and implications for a pH sensing mechanism. J. Struct. Biol. 213, 107729 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iriarte M., et al. , TyeA, a protein involved in control of Yop release and in translocation of Yersinia Yop effectors. EMBO J. 17, 1907–1918 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cherradi Y., et al. , Interplay between predicted inner-rod and gatekeeper in controlling substrate specificity of the type III secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 1183–1199 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Portaliou A. G., et al. , Hierarchical protein targeting and secretion is controlled by an affinity switch in the type III secretion system of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 36, 3517–3531 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yu X. J., Grabe G. J., Liu M., Mota L. J., Holden D. W., SsaV interacts with SsaL to control the translocon-to-effector switch in the Salmonella SPI-2 type three secretion system. mBio 9, e01149-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferracci F., Schubot F. D., Waugh D. S., Plano G. V., Selection and characterization of Yersinia pestis YopN mutants that constitutively block Yop secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 970–987 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Botteaux A., Sory M. P., Biskri L., Parsot C., Allaoui A., MxiC is secreted by and controls the substrate specificity of the Shigella flexneri type III secretion apparatus. Mol. Microbiol. 71, 449–460 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]