Abstract

Background:

Implicit bias may prevent patients with abdominal pain from receiving optimal workup and treatment. We hypothesized that patients from socially disadvantaged backgrounds would be more likely to experience delays in receiving operative treatment for cholecystitis. To study this question, we examined factors related to having a prior ED presentation for abdominal pain (prior ED visit) within 3 months of urgent cholecystectomy.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients who received an urgent cholecystectomy at an urban safety net public hospital between 7/2019-12/2022. The main outcome of interest was prior ED visit within 3 months of index cholecystectomy. We examined patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, preferred language, insurance, and employment status. Bivariate comparisons and logistic regression were used to determine the relationship between patient factors and prior ED visit.

Results:

Of 508 cholecystectomy patients, 138 (27.2%) had a prior ED visit in the 3 months preceding their surgery. In bivariate analysis, younger age, Black race, Hispanic ethnicity, non-English preferred language, and type of insurance (p<0.05) were associated with prior ED visit. In regression, younger age, Black race, Hispanic ethnicity, and having Medicare or being uninsured were associated with higher odds of having a prior ED visit.

Conclusion:

More than 1 in 4 patients had an evaluation for abdominal pain within 3 months of having an urgent cholecystectomy, and these patients were more likely to be from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. Standardized evaluation pathways for abdominal pain are needed to reduce disparities from institutional or implicit bias.

Two Sentence Summary

Through a retrospective chart review of patients receiving an urgent cholecystectomy, more than 1 in 4 patients were found to have had an evaluation for abdominal pain within 3 months of the procedure, and these patients were more likely to be from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. Standardized evaluation pathways for abdominal pain are needed to reduce disparities from institutional or implicit bias.

Introduction

Cholecystectomy, or surgical removal of the gallbladder, is a common procedure in the United States, with upwards of 500,000 cholecystectomies yearly1. For patients with acute gallbladder inflammation, or acute cholecystitis, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy within three days of hospital admission is the standard of care2. While generally a safe procedure, cholecystectomy does have risks which occur in less than 20% of cases and can include bile duct injuries, bile leakage, hemorrhage, subhepatic abscess, retained bile duct stones, and death3,4. The timing of cholecystectomy has been shown to be a crucial factor in patient outcomes. Studies have shown that conducting a cholecystectomy within 24 hours of hospital admission is associated with better outcomes, such as lower rates of postoperative complications and shorter mean hospital length of stay5. Therefore, identifying and correcting the factors that lead to delays in cholecystectomies is imperative to improving outcomes in this patient population.

Currently, emergency general surgery (EGS) care is affected by significant disparities, particularly for patients from disadvantaged groups, such as individuals of Non-White race and individuals without insurance. Inequities can be demonstrated by measured differences in accessibility and quality of care provided to individuals from disadvantaged groups, and can manifest as longer wait times for surgery, more advanced disease presentation, and higher surgical complications. Literature suggests that counties with higher proportions of Black, Hispanic, and uninsured individuals are less likely to have access to EGS care at local hospitals.6 Wait times are longer for Black patients in the emergency room when compared to White patients, and Black Medicare patients are significantly less likely than their White counterparts to receive surgical consultations7,8. Even among patients who undergo surgery emergently, Black patients have been found to be 10% more likely to die following surgery compared to White patients, which has been attributed to higher comorbidity burdens, more severe EGS disease, and treatment at hospitals with lower quality care9-11. Given the disparities faced by non-White and uninsured populations at every level of EGS management, it is likely these same patients would face barriers to obtaining timely cholecystectomies.

The goal of our study was to examine factors that contribute to delays in care for patients with acute cholecystitis. We selected this medical condition in particular because of anecdotal experiences of patients with cholecystitis telling providers of prior episodes of medical evaluation for similar pain but did not receive a workup for potential gallstone disease. . Based on these experiences, our research team wanted to evaluate whether there was institutional or systemic bias that contributed to delays in care for patients who eventually underwent an emergent cholecystectomy. We performed a single center retrospective study of consecutive patients who underwent urgent cholecystectomy and determined whether the patient had been discharged from the ED for an abdominal pain presentation within three months of their index surgical admission. We examined whether age, sex, race, ethnicity, preferred language, insurance, and employment status could be associated with patients being discharged without a cholecystectomy during their prior ED visit for abdominal pain. Based on prior literature, we hypothesized that emergency cholecystectomy patients who were of non-White race or who lacked insurance would be more likely to have prior ED visits for abdominal pain before receiving an emergent cholecystectomy.

Methods

Study Population

We queried the electronic medical record (EMR) for all cholecystectomies conducted by the acute care surgery (ACS) service at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio from July 2019 to December 2022. MetroHealth Medical Center is a tertiary care, level 1 trauma center with an active emergency department and a dedicated Emergency General Surgery service. This hospital is a publicly owned institution, with a longstanding public commitment to care for everyone, regardless of ability to pay.

Patients were identified by querying the electronic medical record (EMR) for cholecystectomy (both open and laparoscopic) procedures performed attending physicians from the Emergency General Surgery service, thus indicating the procedure was performed in a non-elective fashion. Cases were excluded if patients were under the age of 18 and if the cholecystectomy was performed in the elective or outpatient setting. The admission for urgent cholecystectomy was considered the index admission, and we conducted a retrospective chart review for all patients who met inclusion criteria.

Outcome of Interest

Our main outcome of interest was prior presentation to the ED for abdominal pain in the three-month period preceding the index cholecystectomy admission (prior ED visit). We recorded whether the patient had a prior ED visit, the number of prior ED visits, if they received workup at the prior ED visit including imaging studies such as an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan or right upper quadrant (RUQ) ultrasound, bloodwork, or a surgical consultation. The patient’s presumed diagnosis at discharge from the prior ED visit was also noted. We additionally reviewed patient charts for intraoperative and postoperative outcomes, including length of surgery, intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, and total length of stay.

Covariates

Patient demographic information collected included patient age at cholecystectomy, age, sex, race, ethnicity, preferred language, insurance, and employment status. Patients were categorized by race as White [the reference group], Black or African American, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, more than one race, and Unknown or Not Reported. The race and ethnicity categories are based on the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) 2015 Racial and Ethnic Categories notice12. Due to sample size limitations, race groups were then condensed to three groups of White, Black, or Other for multivariable regression analysis. Patients were categorized by ethnicity as either Not Hispanic or Latino [reference] and Hispanic or Latino. Preferred language was categorized as English [reference], Spanish, or Other. Insurance was defined as Private [reference], Uninsured, Medicare, Medicaid, Both Medicare and Medicaid, Tricare, Other, and Unknown or Not Reported. Employment was categorized as Employed [reference], Self-employed, Retired, Unemployed, and Unknown or Not Reported.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were made between patients who did and did not have a prior ED visit. Categorical and binary variables were compared using X2 testing. Continuous variables are reported as medians with interquartile range (IQR) and were compared using Wilcoxon ranksum testing. Multivariate logistic modeling was performed to determine the demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with a prior ED visit.

We then reported surgical outcomes between patients who did and did not have a prior ED visit, including operative time, operative complications, conversion to open, and postoperative complications using X2 and Wilcoxon ranksum testing. For patients with a prior ED visitwe report the number of previous visits, the reason for discharge without surgery, whether imaging was performed, and whether there were any abnormalities in laboratory tests that were performed. The rationale of examining these factors was to determine if these patients were underdiagnosed (which would suggest clinician bias in recognizing disease), or if the diagnosis was made and no surgery was performed (which might suggest patient preference or plans for alternative care).

All statistical analyses were performed in STATA SE/17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This study was approved by the local institutional review board (IRB #20-00965).

Results

We included 508 patients in our study. More than one in four of those patients (27.2%, n = 138) had a prior ED visit for abdominal pain. Upon analysis of patient demographics (Table 1), there were significant differences between patients who had a prior ED visit compared to those who did not. Patients who had a prior ED visit were significantly younger (p < 0.001), with a median age of 39 years old (IQR 29-60) compared to 50 years old (IQR 36-65) for those without a prior presentation to the ED. Race groups significantly differed between those with and without prior ED visits (p=0.013) (Table 1). Black patients made up 32.6% of the patients with a prior ED visit compared to 25.1% of those without a prior ED visit. White patients, who encompassed 58.7% of the entire study population, made up 50% of the group with a prior ED visit and 61.9% of those who did not. Hispanic patients were also more likely to have a prior ED visit (p = 0.010), making up 23.2% of those with a prior ED visit and 13.5% of patients without a prior ED visit. Patients with a prior ED visit were also more likely to speak Spanish as their preferred language (p = 0.019). Lastly, insurance status was significantly different between the two groups, with patients with a prior ED visit being more likely to be uninsured or on Medicaid (p = 0.009).

Table 1.

Demographics of patients with emergent cholecystectomy with and without a prior ED visit for abdominal pain (July 2019-December 2022).

| Demographics | Prior ED visit (n = 138, 27.2%) |

No prior ED visit (n = 370, 72.8%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 39 (29-60) | 50 (36-65) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Male | 38 (27.5%) | 38 (27.5%) | 0.180 |

| Female | 125 (33.8%) | 125 (33.8%) | ||

| Race | American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.013* |

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (2.4%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.8%) | ||

| Black or African American | 45 (32.6%) | 93 (25.1%) | ||

| White | 69 (50.0%) | 229 (61.9%) | ||

| More than one | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (0.8%) | ||

| Unknown/not reported | 33 (8.9%) | 22 (15.9%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 32 (23.2%) | 50 (13.5%) | 0.010* |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 106 (76.8%) | 313 (84.6%) | ||

| Unknown/not reported | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (1.9%) | ||

| Preferred Language | English | 113 (81.9%) | 334 (90.3%) | 0.019* |

| Spanish | 19 (13.8%) | 23 (6.2%) | ||

| Other | 6 (4.4%) | 13 (3.5%) | ||

| Insurance | Private | 21 (15.2%) | 89 (24.1%) | 0.009* |

| Uninsured | 22 (15.9%) | 30 (8.1%) | ||

| Medicaid | 62 (44.9%) | 124 (33.5%) | ||

| Medicare | 24 (17.4%) | 83 (22.4%) | ||

| Medicare and Medicaid | 5 (3.6%) | 31 (8.4%) | ||

| Tricare | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Other | 3 (2.2%) | 6 (66.7%) | ||

| Unknown/not reported | 1 (0.7%) | 6 (1.6%) | ||

| Employment Status | Employed | 56 (40.6%) | 128 (34.6%) | 0.583 |

| Unemployed | 62 (44.9%) | 180 (48.7%) | ||

| Self-employed | 6 (4.4%) | 12 (3.2%) | ||

| Retired | 6 (4.4%) | 26 (7.0%) | ||

| Unknown/not reported | 8 (5.8%) | 24 (6.5%) | ||

Logistic Regression

We then analyzed factors associated with a prior ED presentation in a multivariable logistic regression (Table 2), Black patients had 1.80 the odds of having a prior ED visit for abdominal pain compared to White patients (p=0.017, 95% CI 1.11-1.92). Hispanic patients had 1.94 the odds of having a prior ED visit for abdominal pain compared to non-Hispanic patients (p=0.021, 95% CI 1.10-3.40). Insurance was also significantly related to prior ED presentation, as patients without insurance (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.31-5.95 p=0.007) and with Medicare (OR 2.57, p=0.021, 95% CI 1.15-5.70) both having increased odds of a prior ED presentation. Patients with Medicaid had 1.69 the odds of having a prior ED visit, although that was not statistically significant (p=0.079, 95% CI 0.94-3.03). Of note, primary language was co-linear with ethnicity and therefore preferred language was not included in our logistic regression model.

Table 2.

Factors associated with a prior ED visit for abdominal pain by logistic regression.

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p- value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.97 | (0.96,0.99) | 0.001 | |

| Female | 0.99 | (0.62,1.58) | 0.96 | |

| Race (vs. White) | Black | 1.80 | (1.11,2.92) | 0.017 |

| Other | 1.40 | (0.54,3.65) | 0.49 | |

| Ethnicity (vs. Not Hispanic or Latino) | Hispanic or Latino | 1.94 | (1.10,3.40) | 0.021 |

| Insurance (vs. Private) | Medicare | 2.57 | (1.15,5.70) | 0.021 |

| Medicaid | 1.69 | (0.94,3.03) | 0.079 | |

| Uninsured | 2.80 | (1.31,5.95) | 0.007 | |

| Other | 0.90 | (0.24,1.68) | 0.36 | |

Surgical and Pathological Outcomes

In patients with a prior ED visit, there was no significant difference in rates of intraoperative complications, open cholecystectomies, or postoperative complications between patients who did and did not have a prior ED visit (Table 3). There was a statistically significant, but not clinically significant, difference in operating time whereby patients with a prior ED visit had a shorter median operating time compared to patients without a prior visit (123 vs 136 minutes, p=0.045). Pathology was documented for 508 patients. There was no significant difference between the pathology findings between the prior ED visit and no prior ED visit cohorts. For the prior ED visit cohort, 18.7% had acute cholecystitis, 53.2% had chronic cholecystitis, and 28.1% had acute on chronic cholecystitis. In in the no prior ED visit cohort, 18.5% had acute cholecystitis, 53.1% had chronic cholecystitis, and 28.4% had acute on chronic cholecystitis.

Table 3.

Perioperative Outcomes for Patients With and Without a Prior ED Visit

| Prior ED visit (n = 138, 27.2%) |

No prior ED visit (n = 370, 72.8%) |

p- value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative Factors | ||||

| Operating Time (median, IQR) | 122.5 (90-181) | 136 (108-170) | 0.045 | |

| Complications | Yes | 13 (9.4%) | 40 (10.8%) | 0.65 |

| No | 125 (90.6%) | 330 (89.2%) | ||

| Laparoscopic status | Fully laparoscopic | 135 (97.8%) | 356 (96.2%) | 0.11 |

| Laparoscopic converted to open | 2 (1.5%) | 14 (3.8%) | ||

| Open | 1 (0.72) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Post-operative Factors | ||||

| Length of stay (days) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-5) | 0.46 | |

| Presence of post-op complication | Yes | 22 (15.9%) | 72 (19.5%) | 0.36 |

| No | 116 (84.1%) | 298 (80.5%) | ||

Characterization of Prior ED Visits

We further characterized patients’ prior ED visits for abdominal pain in the three months preceding their emergent cholecystectomy (Table 4). Of the patients who had a prior ED visit, 61.2% presented once within the preceding three months, 28.4% presented twice, 9.0% presented three times, and 1.5% presented four times. No patients presented more than 4 times. Most of these patients were discharged from the ED without a surgery consultation (56.8%), while a minority received a surgery consultation before discharge (12.9%). Some refused the surgery or left the ED against medical advice (8.3%).

Table 4:

Prior ED Visit Characteristics

| Variable | Patients who were previously seen (n = 138) |

|---|---|

| Number of previous visits | |

| 1 | 82 (61.2%) |

| 2 | 38 (28.4%) |

| 3 | 12 (9.0%) |

| 4 | 2 (1.5%) |

| Reason for discharge without surgery | |

| ED discharge w/o surgery consult | 75 (56.8%) |

| Surgery consulted, discharged | 17 (12.9%) |

| Patient refusal/AMA | 11 (8.3%) |

| Other | 22 (16.7%) |

| Unknown | 7 (5.3%) |

| Testing received (type) | |

| Imaging | |

| No imaging | 37 (29.1%) |

| RUQ US | 36 (28.4%) |

| CT scan | 32 (25.2%) |

| No RUQ US or CT scan | 3 (2.4%) |

| Both RUQ and CT scan | 19 (15.0%) |

| Abnormalities on lab testing | |

| No testing done | 15 (12.0%) |

| WBC only | 25 (20.0%) |

| LFTs only | 31 (24.8%) |

| WBC and LFTs | 13 (10.4%) |

| No abnormal testing | 41 (32.8%) |

During the ED visit immediately preceding the urgent cholecystectomy, imaging was not acquired for 29.1% of patients, while the rest either received an RUQ ultrasound (28.4%), CT scan (25.2%) or both (15.0%). Regarding laboratory testing, 12.0% of patients had no white blood cell counts (WBC) or liver function tests (LFTs) completed. Of the patients who received these laboratory tests, 32.8% of patients had no abnormal results. Presumed diagnosis at discharge was collected for 134 of the 138 patients with a previous ED presentation. The most common diagnoses at discharge were abdominal pain (n=38, 28.4%), calculus of gallbladder without cholecystitis (n=20, 14.9%), biliary colic (n=10, 7.4%), cholelithiasis (n=10, 7.4%), and gastritis (n=8, 6.0%). Other diagnoses, which made up the last third of patients, were nausea/vomiting (n=4), choledocholithiasis (n=3) acute pancreatitis (n=2), constipation (n=2), diverticulitis (n=2), elevated LFTs (n=2), abdominal wall abscess (n=1), acid reflux in pregnancy (n=1), alcohol withdrawal syndrome (n=1), anxiety (n=1), chest wall contusion (n=1), chronic back pain (n=1), common bile duct dilatation (n=1), COVID-19 (n=1), E. coli bacteremia (n=1), flank pain (n=1), hepatitis (n=1), HIV infection (n=1), hyperglycemia (n=1), infection of arteriovenous fistula (n=1), lumbar strain (n=1), sepsis (n=1), splenule (n=1), strain of abdominal wall (n=1), ureterolithiasis(n=1), viral syndrome (n=1). Only 6 patients (4.5%) had a diagnosis of cholecystitis upon their initial discharge. 25 patients received surgical consultation on their prior ED visit. These included patients with discharge diagnoses of acute cholecystitis (5/6), calculus of gallbladder without cholecystitis (6/20), choledocholithiasis (3/3), biliary colic (2/10), cholelithiasis (2/10), acute pancreatitis (1/2), E. coli bacteremia (1/1), abdominal pain (1/38), gastritis (1/8), hepatitis (1/1), ureterolithiasis (1/1), and viral syndrome (1/1).

Discussion

In our study, which included 508 patients who underwent emergent cholecystectomy, we found that more than one in four (27.2%) had a previous visit to the emergency department for abdominal pain. Patients with a prior ED visit were generally younger, with a median age of 39 years, and more likely to be Black or Hispanic compared to those without a prior visit. Our logistic regression analysis further highlighted that Black and Hispanic patients had higher odds of a prior ED visit for abdominal pain compared to their White and non-Hispanic counterparts. Insurance status also played a significant role, with uninsured patients and those on Medicare more likely to have had a prior ED visit.

Our findings corroborate existing literature that has found that patients from minoritized backgrounds, such as patients of Black race or patients that lack insurance, face disparities in EGS care, such as experiencing longer wait times3-9. Of note, our retrospective patient cohort was collected at an institution which prides itself upon a mission to care for all, regardless of ability to pay. However, based on our findings, even in our institution, minoritized patients may be affected by systemic biases including under-diagnosis. In our study, nearly 3 in 10 patients did not receive any imaging during their prior ED visit, and 12.0% did not have a WBC or LFTs obtained. This inadequate workup may have led to patients being discharged with acute cholecystitis only to return for an urgent cholecystectomy. For some patients, it is also likely that the pain was attributed to biliary colic rather than acute cholecystitis, and patients with social disadvantage were unable to schedule elective cholecystectomy before another biliary abdominal pain episode occurred which then necessitated cholecystectomy. Due to the small sample size of the prior ED visit subgroup, race, ethnicity, and insurance status were not assessed, however, these factors may have played a role in completing the workup as well. Our study also suggested that there are multiple decision points that can contribute to a delayed cholecystectomy including recognition and workup of the disease, decision that a cholecystectomy is appropriate by surgery, and patient preference. .

Disparities Based on Race, Ethnicity, and Preferred Language

We found that minoritized patients, particularly Black and Hispanic patients were significantly more likely to have a prior ED visit for abdominal pain before receiving an urgent cholecystectomy compared to White and non-Hispanic patients. This supports previous health disparities research that shows that Black and Hispanic populations have less access to EGS care at local hospitals and longer wait times for consultations, if they receive a surgical consultation at all6-8. One possible reason among many for these observed disparities is racial bias that predisposes clinicians to disbelieve the pain of people of color13-15. Additionally, in the univariate analysis, Spanish speakers had an increased likelihood of a prior ED visit for abdominal pain. This disparity may be due to racial or ethnic biases leading clinicians to disbelieve patients’ symptoms and stories or the presence of a language barrier, which may lead to mistranslation and miscommunication about severity, onset, location, and quality of pain.

Disparities Based on Insurance Status

Insurance can be used as a proxy for socioeconomic status, with lack of insurance or Medicaid insurance denoting patients with higher risk. Our study found that patients without insurance and those using Medicare were significantly more likely to have a prior ED visit for abdominal pain compared to privately insured patients. This supports previous research finding that uninsured patients receive less EGS care compared to insured patients6,16. In our logistic regression analysis, Medicaid was not a statistically significant risk for having a prior ED visit compared to patients with private insurance. However, 33.3% of Medicaid patients had a prior ED visit compared to 19.1% of privately insured patients, so the data shows a trend in the direction of Medicaid patients being more likely to have a prior ED visit. This finding supports previous literature on access to EGS care which has found that Medicaid patients have decreased access and worse outcomes compared to privately insured patients17,18. Finally, the relationship between insurance and prior ED presentation is likely complicated by the complex interplay between race, insurance, and socioeconomic status. Black and Hispanic patients have historically had much higher uninsurance and Medicaid rates than White adults19, as race, socioeconomic status, and insurance are frequently linked. Thus, it is possible that disparities by insurance status are masked by racial and ethnic disparities or vice versa.

No Difference in Surgical Outcomes Based on Early Versus Delayed Choles

In our analysis of 508 patients, having a prior ED visit was not associated with worse surgical outcomes following emergent cholecystectomy. This finding is consistent with the previous equivocal outcomes documented by other studies20-22. In our study, patients with a prior ED visit even had a shorter median operating time than patients who did not have a prior ED visit, although the time difference was fourteen minutes and not clinically significant. Given the low rates of conversion to open and mortality for cholecystectomy, our study was not powered to find a difference in these outcomes. Despite not finding a difference in postoperative outcomes, we argue that the act of returning to the ED multiple times for the same chief complaint is undesirable and is itself a reason to address this disparity as this is a financial, occupational, and emotional burden for patients23,24.

Strategies to Reduce Disparities based on Race, Ethnicity, and Insurance Status

Following an ED visit for abdominal pain, several steps must be taken before a patient receives a cholecystectomy. Each step, from obtaining appropriate imaging, laboratory tests, a surgical consultation, to consenting to the procedure itself is a place for disparities to occur2. If the ED staff does not procure proper testing or decides the results do not indicate acute cholecystitis, the patient may be discharged before receivinga surgery consultation. . Once a patient is discharged, they are instructed to return to the ED if their symptoms worsen or their pain persists25. Patients who return to the ED and subsequently receive a cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis may be days to weeks removed from the standard of care time it should have taken to receive the procedure.

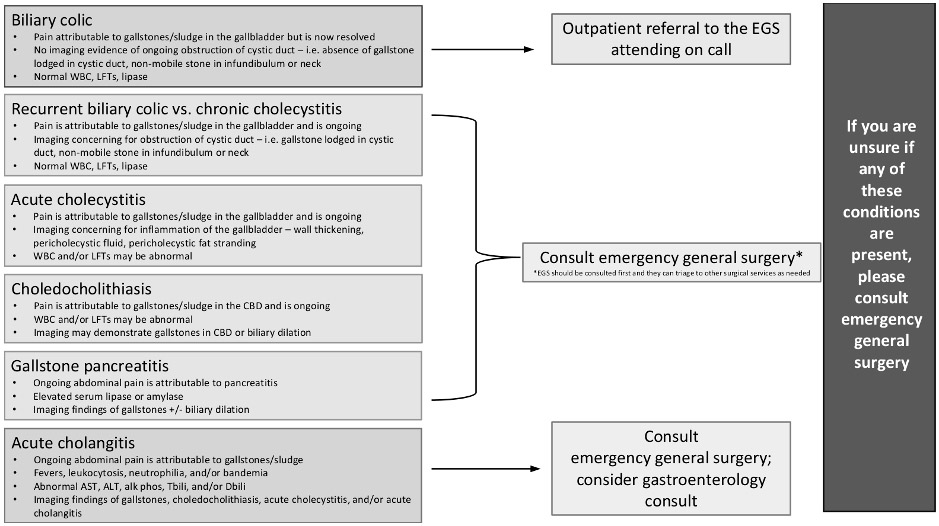

One way to eliminate racial, ethnic, and insurance disparities in emergent cholecystectomies is to provide individualized, feedback-oriented bias training to clinical staff. An anti-bias training effort undertaken by fellows and residents specializing in treating chronic pain were found to have more equitable treatment practices after undertaking this training26. This work was completed at a large, public county hospital. While it would be not be feasible for every patient to receive an EGS consult, ED providers should follow a standardized protocol in order to most accurately determine which patients require a surgical consult. At our institution, we instituted a guideline for benign biliary diseases (Figure 1), which includes clear direction for when to consult general surgery for suspected benign biliary diseases considering the patient’s symptoms, imaging findings, and laboratory testing values. By using this workflow, the goal is to eliminate bias and disparities to ensure patients receive appropriate, timely care for emergent cholecystectomies. This system was implemented at our institution in 2023, and future research will examine if disparities decrease after guideline implementation.

Figure 1.

Institutional guideline for benign biliary diseases.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study is that it explores a previously under-researched area in disparities studies – factors that influence a patient’s likelihood of having a prior ED visit for abdominal pain preceding an urgent cholecystectomy. Anecdotally, women and people of color of all genders are ‘turned away’ from the ED after workup, and this study explored whether these anecdotal reports have merit. The large sample size of our study adds power to our results.

Important limitations of our study include the retrospective and single-center nature of the study. In addition, imaging and laboratory testing results were obtained for most patients that had a prior ED visit for abdominal pain, with some having normal labs and imaging reassuring against acute cholecystitis. This could suggest that these patients did not qualify for an emergent cholecystectomy at the time of their initial ED visit. Additionally, some patients presented with multiple problems, which could suggest that there may have been a more urgent issue to be addressed before determining indications for emergent cholecystectomy. We are unable to know how many patients presented to the hospital with abdominal pain, and if patients later re-presented to other institutions with cholecystitis. Further analysis of the discharge diagnoses will need to be done to determine correlation between ED presentation and later emergent cholecystectomy. An additional potential limitation to the study is that the data largely came from the COVID-19 pandemic. In the future, it would be valuable for us to compare this study to one from data before the pandemic, or even after, with the incorporation of the new benign biliary disease guideline.

Conclusion

Our study found that more than one in four patients were evaluated for abdominal pain in the ED within three months of undergoing an urgent cholecystectomy. These patients were disproportionately from historically marginalized groups, aligning with previous research that shows racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in other aspects of EGS care. While there is a large literature base showing that healthcare disparities exist along racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines, more research must be done on concrete ways to address disparities6-8,13,14,16 Many studies provide potential strategies to reduce disparities, such as improving health literacy or improving patient advocacy, but few randomized controlled trials have been attempted to compare patient outcomes following attempts to reduce disparities26-29 . These findings underscore the importance of standardized evaluation plans for abdominal pain in the ED to reduce disparities from implicit or institutional bias.

COI/Disclosures

VPH was supported by the CTSC of Cleveland (KL2TR002547).

VPH spouse is a consultant to Zimmer Biomet, Sig Medical, Atricure, Astra Zeneca, and has received research support from Zimmer Biomet and the Intuitive Foundation.

Funding/Financial Support

This publication was made possible by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, KL2TR002547 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research.

Footnotes

This work was presented at the Academic Surgical Congress, February 6-8, 2024, in Washington, D.C.

References

- 1.Schirmer BD, Winters KL, Edlich RF. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 2005; 15: 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallaher JR, Charles A. Acute Cholecystitis: A Review. JAMA 2022; 327: 965–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banz V, Gsponer T, Candinas D, et al. Population-Based Analysis of 4113 Patients With Acute Cholecystitis: Defining the Optimal Time-Point for Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 2011; 254: 964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duca S, Bãlã O, Al-Hajjar N, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: incidents and complications. A retrospective analysis of 9542 consecutive laparoscopic operations. HPB 2003; 5: 152–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutt CN, Encke J, Köninger J, et al. Acute Cholecystitis: Early Versus Delayed Cholecystectomy, A Multicenter Randomized Trial (ACDC Study, NCT00447304). Ann Surg 2013; 258: 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khubchandani JA, Shen C, Ayturk D, et al. Disparities in Access to Emergency General Surgery Care in the United States. Surgery 2018; 163: 243–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Angelis P, Kaufman EJ, Barie PS, et al. Disparities in Timing of Trauma Consultation: A Trauma Registry Analysis of Patient and Injury Factors. J Surg Res 2019; 242: 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts SE, Rosen CB, Keele LJ, et al. Rates of Surgical Consultations After Emergency Department Admission in Black and White Medicare Patients. JAMA Surg 2022; 157: 1097–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall EC, Hashmi ZG, Zafar SN, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in emergency general surgery: explained by hospital-level characteristics? Am J Surg 2015; 209: 604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimick J, Ruhter J, Sarrazin MV, et al. Black patients more likely than whites to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated regions. Health Aff Proj Hope 2013; 32: 1046–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zogg CK, Olufajo OA, Jiang W, et al. The Need to Consider Longer-term Outcomes of Care: Racial/Ethnic Disparities among Adult and Older Adult Emergency General Surgery Patients at 30, 90, and 180 Days. Ann Surg 2017; 266: 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institutes of Health. Racial and Ethnic Categories and Definitions for NIH Diversity Programs and for Other Reporting Purposes. Notice NOT-OD-15-089, https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-089.html (8 April 2015, accessed 8 October 2023).

- 13.Salamonson Y, Everett B. Demographic disparities in the prescription of patient-controlled analgesia for postoperative pain. Acute Pain 2005; 7: 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills AM, Shofer FS, Boulis AK, et al. Racial disparity in analgesic treatment for ED patients with abdominal or back pain. Am J Emerg Med 2011; 29: 752–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickason RM, Chauhan V, Mor A, et al. Racial Differences in Opiate Administration for Pain Relief at an Academic Emergency Department. West J Emerg Med Integrating Emerg Care Popul Health; 16. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2015.3.23893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz DA, Hui X, Schneider EB, et al. Worse outcomes among uninsured general surgery patients: Does the need for an emergency operation explain these disparities? Surgery 2014; 156: 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bischoff A, Bovier PA, Isah R, et al. Language barriers between nurses and asylum seekers: their impact on symptom reporting and referral. Soc Sci Med 2003; 57: 503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al Shamsi H, Almutairi AG, Al Mashrafi S, et al. Implications of Language Barriers for Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Oman Med J 2020; 35: e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulatao RA, Anderson NB, National Research Council (US) Panel on Race E. Health Care. In: Understanding Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life: A Research Agenda. National Academies Press (US), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK24693/ (2004, accessed 28 July 2023). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucocq J, Patil P, Scollay J. Acute cholecystitis: Delayed cholecystectomy has lesser perioperative morbidity compared to emergency cholecystectomy. Surgery 2022; 172: 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee W, Kwon J. Delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy after more than 6 weeks on easily controlled cholecystitis patients. Korean J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg 2013; 17: 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roulin D, Saadi A, Di Mare L, et al. Early Versus Delayed Cholecystectomy for Acute Cholecystitis, Are the 72 hours Still the Rule? Ann Surg 2016; 264: 717–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emergency department visits exceed affordability threshold for many consumers with private insurance. Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/emergency-department-visits-exceed-affordability-thresholds-for-many-consumers-with-private-insurance/ (accessed 28 July 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faessler L, Perrig-Chiello P, Mueller B, et al. Psychological distress in medical patients seeking ED care for somatic reasons: results of a systematic literature review. Emerg Med J EMJ 2016; 33: 581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macaluso CR, McNamara RM. Evaluation and management of acute abdominal pain in the emergency department. Int J Gen Med 2012; 5: 789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsh AT, Miller MM, Hollingshead NA, et al. A randomized controlled trial testing a virtual perspective-taking intervention to reduce race and SES disparities in pain care. Pain 2019; 160: 2229–2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bucknor-Ferron P, Zagaja L. Five strategies to combat unconscious bias. Nursing2023 2016; 46: 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dykes DC, White AA. Getting to Equal: Strategies to Understand and Eliminate General and Orthopaedic Healthcare Disparities. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 2598–2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hendren S, Griggs JJ, Epstein RM, et al. Study Protocol: A randomized controlled trial of patient navigation-activation to reduce cancer health disparities. BMC Cancer 2010; 10: 551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]