Abstract

An outdated and burdensome fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement system has significantly compromised primary care delivery in the US for decades, leading to a dire shortage of primary care workers. Support for primary care must increase from all public and private payers with well-designed value-based primary care payment. Patient care enabled by value-based payment is typically described or “labeled” as value-based care and commonly viewed as distinctly different from other models of care delivery. Unfortunately, labels tend to put individuals in camps that can make the differences seem greater than they are in practice. Achieving the aims of value-based care, aligned with the quintuple aims of health care, is common across many delivery models. The shrinking primary care workforce is too fragile to be fragmented across competing camps. Seeing the alignment across otherwise separate disciplines, such as lifestyle medicine and value-based care, is essential. In this article, we point to the opportunities that arise when we widen the lens to look beyond these labels and make the case that a variety of models and perspectives can meld together in practice to produce the kind of high-quality primary care physicians, care teams, and patients are seeking.

Keywords: primary care, lifestyle medicine, value-based payment, value-based care, whole health, whole health care

“Clinical practice guidelines for many chronic diseases recommend lifestyle intervention as the first line of treatment.”

Introduction

Resounding calls for a move to value-based payment are driving many changes across the health care system.1,2 Value-based “payment” is intended to support value-based “care” but we know that in reality, the shift is not that simple. Value-based payment, aka alternative payment models or APMs are terms used to describe a wide range of payment models—and not all are well-designed to achieve the desired outcome. 3 Likewise, when asked what constitutes “value-based care,” one is likely to receive as many unique responses as questioners asked. We assert that value-based care when applied in a primary care setting, is an example of the kind of high-quality primary care defined in the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine Report: Implementing High Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care as well as the delivery of whole health care as viewed by primary care physicians, many of whom choose to address their patient’s needs by incorporating lifestyle medicine into their practice. 4

Achieving widespread, equitable access to this kind of high-quality primary care cannot happen without significant change in the financial support for primary care. 5 While some progress has been made toward improving primary care payment through a variety of value-based payment approaches, it is not nearly enough. This paper will describe what well-designed value-based payment for primary care should look like and how that can be deployed to build care delivery models that work well for patients and their care teams, including incorporating lifestyle medicine principles into everyday practice. Finally, we point to recommendations that individuals and organizations can embrace immediately to move beyond the labels and toward implementation of the kind of primary care physicians, care teams, and patients are desperately seeking.

Powerful Synergies Hidden Beyond the Labels

While much can be said about the differences in training and practice between a biomedical and lifestyle medicine approach, the commonalities, and points of alignment for primary care physicians and others are many when considered from the perspective of the patient—the whole person. As we face the increasingly grim predictions for the primary care workforce, bridging these perspectives or “camps” is one way to ensure a supportive and well-resourced practice environment—whether one is attempting to incorporate the best of both worlds or fully in one “camp” or the other. 6 A comparison of the prevailing definitions used to describe primary care, whole health care, and lifestyle medicine reveals significant alignment around core concepts such as whole health, well-being, and integrated team-based care.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) 2021 Consensus Report, Implementing High Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation, defined primary care as the provision of whole person, integrated, accessible, and equitable health care by interprofessional teams who are accountable for addressing the majority of an individual’s health and wellness needs across settings and through sustained relationships with patients, families, and communities. 4 This report further describes whole-person health as focusing on well-being rather than the absence of disease. It accounts for the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual health and the social determinants of health of a person.

NASEM also convened an expert committee to examine and report on “Transforming Health Care to Create Whole Health: Strategies to Assess, Scale, and Spread the Whole Person Approach to Health.” The committee was tasked with examining the potential for improving health outcomes through whole health care and recommending future directions and priorities for health systems interested in implementing a system of whole-person care. The committee’s first consensus report published in 2023, Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for the Nation, describes how the Veteran’s Health Administration used its already strong primary care infrastructure to implement a whole health approach to care. 7 This report describes whole health as physical, behavioral, spiritual, and socioeconomic well-being as defined by individuals, families, and communities and whole health care as an interprofessional, team-based approach anchored in trusted relationships to promote well-being, prevent disease, and restore health. The committee further elaborates that whole health care is built on a foundation of high-quality, well-supported primary care that relies on cross sectoral integration, spanning conventional medical care, mental health, health behavior promotion, complementary and integrative health, public health, and social services. This report articulated five foundational elements of whole health that are necessary for an effective whole health care system.

(1) People-centered

(2) Comprehensive and holistic

(3) Upstream focused

(4) Accountable and equitable

(5) Grounded in team well-being

These definitions of primary care are consistent with the view of many lifestyle medicine practitioners, many of whom are primary care physicians and other clinicians. 8 The American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) estimates that nearly 60% of its physician members represent primary care specialties of family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics.

Lifestyle Medicine, as defined by the ACLM, is a medical specialty that uses therapeutic lifestyle interventions as a primary modality to treat chronic conditions including, but not limited to, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Lifestyle medicine certified clinicians are trained to apply evidence-based, whole-person, prescriptive lifestyle change to treat and, when used intensively, often reverse such conditions. (https://www.lifestylemedicine.org)

Primary Care’s Financial (Payment) Conundrum

Primary care has long been regarded as a critical component of a high-performing health system around the world.4,9 In the US, there is a persistent and significant mismatch between the level of US investment in primary care and the degree to which its importance is publicly stated. 10 An undervalued and overly burdensome fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement system has compromised the delivery of high-quality primary care in the US for decades. 11

It was 45 years ago in 1978 when the US joined more than 130 countries across the globe in signing the Declaration of Alma-Ata on Primary Health Care. This public commitment was viewed as a seminal step toward meaningful investment and support of primary health care across the globe. 12 The US also participated in the more recent Global Conference on Primary Health Care in Astana, Kazakhstan held in 2018 to mark the 40th anniversary of Alma-Ata, described by the World Health Organization as “a chance to commemorate the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care, and reflect on how far we have come and the work that still lies ahead.” 13

A number of countries have embraced these two declarations by building their health care delivery systems on a solid primary care foundation combined with a strong public health support system. Sadly, the US is not among them. In the Commonwealth Fund’s report, Mirror, Mirror: Reflecting Poorly, the US ranks last in overall health system performance when compared to a cohort of high-income, peer nations. 9 The report concludes that there are four features that distinguish the highest-performing health systems: (1) providing for universal coverage and removing cost barriers, (2) reducing administrative burdens on patients and clinicians, (3) investing in social services and worker benefits, and (4) investing in primary care systems to ensure value and equitable access.

Since the 1960s when the role of the “generalist” was affirmed by the American Medical Association Graduate Medical Education report (commonly known as the “Mills Commission” report), the US has experienced a persistent and troubling inconsistency between the way we talk about the importance of primary care and the way it is supported—financially and otherwise. US spending on primary care is estimated to be in the range of 3%–9% when measured as a percentage of total health care spending which lags behind peer nations estimated to average 12% of total health care spending on primary care.5,11,14,15

This level of primary care underinvestment persists despite unambiguous evidence of primary care’s ability to favorably impact patient health outcomes, health equity, the clinician and patient experience and overall health care affordability.16-18 The distinct lack of progress in the US served as motivation for the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine to convene the Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care which produced the consensus report, Implementing High Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care in 2021. This report provides a clear roadmap for implementation of high-quality primary care, including stakeholder-specific recommendations for action toward the achievement of five objectives including a call for reforming primary care payment to “pay for primary care teams to take care of people, not doctors to deliver services.” 4

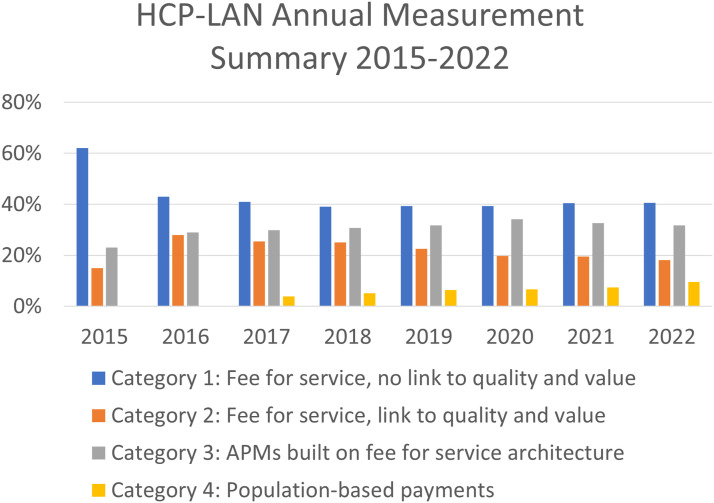

This objective is compatible with the overarching calls to move the health care system from the volume-driven nature of fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement toward a system of payment that recognizes and rewards value, aka value-based payment and care. The Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (HCP-LAN), established by the Affordable Care Act, developed a framework for categorizing a range of alternative payment models from FFS with no ties to quality to global or fully capitated payment models. 3 These categories provide a common framework for stakeholders working together to reform payment and a mechanism for understanding overall progress from volume-to-value.

The most recent report released in October 2023 shows continued progress toward this goal, albeit slowly, somewhat unevenly, and not at the scale required to facilitate the changes urgently needed in primary care. 19 There are some encouraging, and puzzling, trends observed over the last 6 years from 2016 to 2022. (Figure 1) Most notably, the level of straight FFS, no link to quality and value (Category 1 - blue bar) seems fixed at approximately 40%. While FFS linked to quality and value (Category 2 - orange bar) jumped considerably between 2015 and 2016, it has experienced a steady decline since that time moving from 28% in 2016 to 18.1% in 2022, a trend proponents of population-based payment in primary care would likely applaud. While the report does not explicitly track the movement of specific APMs from one category to another, the reduction in the more basic “pay for performance” Category 2 APMs suggests that plans are moving from these more basic APMs to Categories 3 (built on FFS architecture) and 4 (population-based payments). The recent growth in population-based payments is particularly encouraging from a primary care perspective as it increased to 9.6% in 2022 from 7.4% in 2021—the most significant increase reported for all categories. This is especially important to primary care because a significant revenue shift from FFS to population-based payments or “capitation” is believed to be necessary to support practice transformations. 20 In a 2017 study, researchers applied a microsimulation model using real data from almost one-thousand practices to understand what combination of FFS and population-based payments best equips practices to implement proactive team and non-visit based care. They estimate that 63% of practice revenue should come from capitation in order to provide the resources and flexibility needed to implement a more proactive and less “visit centric” model of primary care.

Figure 1.

Health care payment and learning action network annual measurement summary (2015 – 2022).

Promoting Integration of Lifestyle Medicine Principles in High Quality Primary Care Practice

Lifestyle medicine emerged as a therapeutic modality based on the significance of lifestyle factors in maintaining overall health. Acknowledging the importance of lifestyle in promoting well-being dates back to ancient civilizations like India, China, and Greece where diet and exercise were emphasized. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, modern medicine shifted towards a biomedical approach of treating illness with drugs and surgery. While this approach yielded considerable medical breakthroughs, it typically ignored the role of lifestyle in preventing, treating, and reversing chronic diseases.

Addressing the challenges of chronic conditions is an essential aspect of both primary care and lifestyle medicine. By promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors, such as proper nutrition, regular exercise, stress management, positive social connection and avoiding risky substances, lifestyle medicine can prevent, treat, and reverse chronic diseases, leading to improved population health. Lifestyle medicine emphasizes a patient-centered approach, where physicians and other clinical team members work closely with patients to set and achieve health goals related to their lifestyles. This approach fosters better patient-physician communication, engagement, and shared decision-making, ultimately leading to improved patient experience and outcomes.

In 1990, the Lifestyle Heart Trial, led by Dr Dean Ornish, revealed that coronary heart disease patients can effectively adopt significant lifestyle changes outside of the hospital for at least a year. The study also demonstrated a notable regression of coronary atherosclerosis, quantified through quantitative coronary arteriography. 21 Another study reported that patients with cardiovascular disease positively responded to intensive counseling and a plant-based diet, resulting in some achieving a low rate of subsequent cardiac events after maintaining the diet for approximately 3.7 years. 22 The EPIC-Potsdam cohort study found that the Nordic diet showed potential benefits in reducing the risk of MI in the population and stroke in men. On the other hand, the Mediterranean diet was effective in lowering the risk of T2D in the population and MI in women. These studies highlight the worth of lifestyle-based interventions in reducing chronic diseases. 23 Moreover, a lifestyle-based intervention, mainly focused on educating patients about the benefits of plant-based diets for diabetes treatment and remission, led to a decrease in fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels. As a result, medication use was reduced, and T2D remission was observed in 37% of patients. These studies demonstrate that lifestyle-based interventions can effectively reduce chronic diseases. 24

Lifestyle Medicine did not emerge as a unique specialty in US medicine until Dr John Kelly, the founding president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine, pushed to close a crucial gap between the more common biomedical approach that failed to address lifestyle behavior change and the mounting scientific evidence that when treating chronic diseases, lifestyle intervention could be as effective as medication, but without the negative side effects.25-31 He envisioned the need for a specialized medical society to effectively treat and reverse diseases through therapeutic lifestyle intervention. 32 The American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) was established on March 19, 2004, at the inaugural General Meeting held at Loma Linda, CA

Lifestyle modifications are recommended as a first line of treatment in many chronic disease guidelines. 33 However, physician education, training, and clinical practice heavily rely on prescription medications. It is not surprising that physicians reported having received little training in clinical nutrition and LM therapeutic modalities. 34

The ACLM’s goal is to educate, equip, and empower all medical professionals, especially primary care physicians (PCPs), to identify and facilitate the eradication of the root causes of disease with health restoration and whole-person health as the clinical outcome goal. This should be followed, when necessary, by disease management with the aim of medication de-escalation and halting disease progression. 32

Lifestyle Medicine as Therapeutic Modality

The synergies between high-quality primary care and lifestyle medicine go well beyond their definitional frameworks. Like primary care, lifestyle medicine has gained recognition over many years for its potential to contribute to the achievement of the quintuple aim of healthcare. Many lifestyle medicine practitioners come from primary care disciplines. Some work in settings that are exclusively focused on applying lifestyle interventions while others incorporate elements of lifestyle medicine into a more traditional primary care practice setting.

The ACLM recently convened an expert panel of primary care clinicians who also practice lifestyle medicine to develop an expert consensus statement to define best practices for integrating lifestyle medicine into primary care settings to achieve improved outcomes—for patients, physicians, and other members of the care team. 8 The expert panel considered 124 candidate statements across a wide range of topics and were able to arrive at consensus on 65, near consensus on 24, and no consensus on 35. The areas of clear agreement include recognizing lifestyle medicine as an essential component of primary care in patients of all ages, and that lifestyle medicine should serve as a foundational element of health professional education. The expert panel also noted the anticipated outcomes of increasing the use of lifestyle medicine in primary care including addressing the root causes of most common chronic diseases, reducing health-related costs, improving clinical outcomes, enhancing patient and clinician satisfaction, having a positive impact on the environment, and promoting health equity for historically marginalized populations. The Committee defined lifestyle medicine shared medical appointments (LMSMA) as a clinically effective model for delivery of LM services in primary care, based on their ability to improve outcomes for obesity, cardiovascular risk factors, type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and chronic pain.35-40

Lifestyle Medicine offers lifestyle intervention as the first and optimal treatment option for all people, mitigating much of the burden caused by non-communicable chronic diseases. However, it is important to note that it is intended to complement, not replace, conventional medical approaches. Two lifestyle medicine strategies that have been successfully implemented in more traditional primary care settings include the integration of lifestyle medicine vital signs and prescriptions at office visits and LMSMAs.

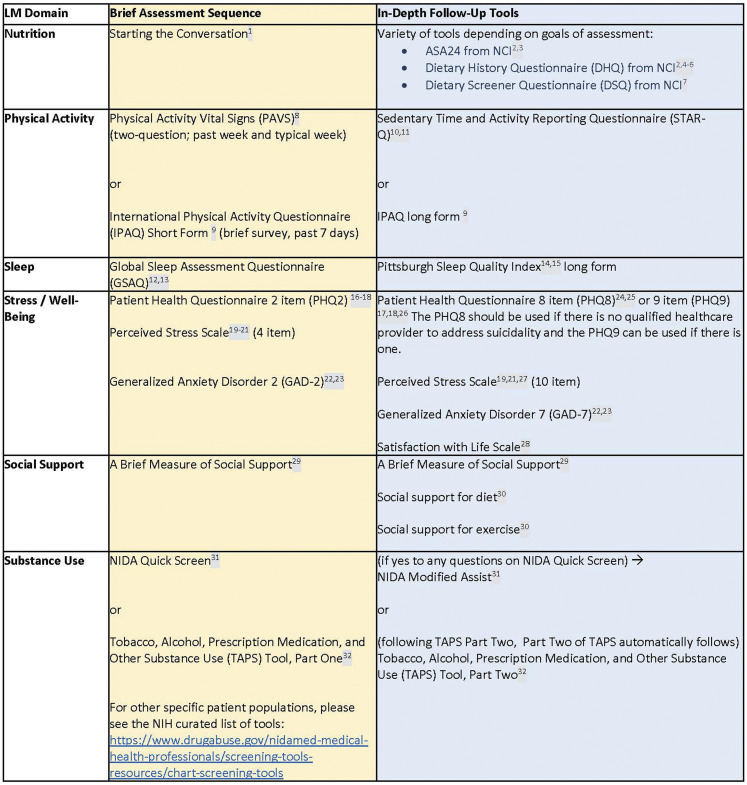

Integration of LM Vital Signs and LM Prescriptions

When examining a patient’s lifestyle medicine history, clinicians look at risk factors that can result in preventable lifestyle-related illnesses. The concept of assessing lifestyle medicine “vital signs” was described in a 2010 JAMA article and is considered a key competency for the LM practitioner. 41 These LM factors include physical activity, nutrition, stress, sleep, emotional well-being, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption. The American College of Lifestyle Medicine has developed a concise Lifestyle Assessment form to assist primary care teams in evaluating these key components (Figure 2). Both a condensed and more comprehensive version of assessment forms for lifestyle medicine risk factors are available to meet the needs of a clinician, and to assist them in directing counseling to areas where the patient is open to change.

Figure 2.

Validated Assessment Tools (created by ACLM and approved by their Research Committee).

A more detailed version of the Lifestyle Medicine assessment form has been developed to provide a comprehensive analysis of lifestyle factors. One effective way to utilize longer forms is to identify key areas of concern for the patient and provide relevant sections of the form during follow-up appointments. This approach empowers the patient to take control of their healthcare and avoids the need for a time-consuming evaluation of all potential lifestyle-related health behaviors. Using a patient-centered process flow, the patient remains at the center of care, making the process less overwhelming. 42 Vital signs are used to obtain a snapshot of important information about a patient. Briefly listing several lifestyle medicine related activities can serve the same purpose as traditional vital signs and provide a complete picture of a patient’s progress in managing their specific chronic diseases. 43

Lifestyle Medicine prescriptions are a foundational component to the practice of Lifestyle Medicine.44,45 The concept of an “evidence-based, achievable, specific written action plan such as a lifestyle prescription” has been part of the lifestyle medicine approach since its early days. Writing lifestyle prescriptions is a core competency for any lifestyle medicine health care clinician. 41 Lifestyle medicine prescriptions must be developed using a detailed lifestyle history, written using a SMART (specific, measurable, accountable, realistic, time connected) approach, and applied by giving the patient a concrete action plan that they have with them as they leave the health care interaction. 45 LM vital signs are reassessed during each visit, and LM prescriptions are adjusted accordingly.

Lifestyle Medicine Focused Shared Medical Appointment (LMSMA)

High-quality primary care is best provided by a team of physicians and other healthcare providers who are organized, supported, and accountable to meet the needs of the people and the communities they serve. Team-based care improves health care quality, use, and costs among chronically ill patients, 46 and it also leads to lower burnout in primary care. 47 Well-designed teams can support nurturing, longitudinal, person-centered care.48-50

The benefits of shared medical appointments for both patients and clinicians are well documented in a variety of contexts. 51 Lifestyle medicine focused shared medical appointments offer an integrated and coordinated team-based, patient-centered model that focuses on continuous improvement in managing chronic diseases by addressing lifestyle behaviors. The interdisciplinary team is typically embedded in medical appointments instead of in-between visits and is often comprised of a physician, NP/PA, registered dietitian, and health coach. In addition, exercise physiologists, licensed social workers or behavioral health experts can be included in the team if resources permit. The team collaborates with patients in setting goals and developing care plans. By engaging in group discussions and learning from shared experiences, patients gain valuable knowledge, skills, and support to make informed decisions about their health. 52 This empowerment enhances patient self-management and adherence to lifestyle changes, leading to better health outcomes. LMSMA structure and framework for in-person and virtual delivery have been successfully implemented in clinical practice by LM trained clinicians.52,53

Improving Value-Based Payment for Primary Care

Increasing primary care investment using a value-based payment approach designed with primary care in mind is critical to ensuring primary care practices have sufficient resources, and the freedom, to build the model of care that works best for their patients and care delivery team. A key distinction between FFS and well-designed VBP is an increase in prospective population-based payments that untether practices from the burdens associated with billing and coding documentation requirements tied to the delivery of discrete services. This is consistent with the Implementing High Quality Primary Care Report objective to “pay for primary care teams to take care of people - not doctors to deliver services.” The American Academy of Family Physician Guiding Principles for Value-Based Payment call on all public and private payers to:

• Pay prospectively to support team-based care,

• Actively engage patients in the accountable relationship,

• Risk adjust payment for medical and social complexity of patients,

• Evaluate what matters to patients and physicians in an aligned fashion across payers,

• Equip primary care teams with clinically relevant and actionable information, and

• Reward year-over-year improvement as well as sustained high performance.

Sufficiently funded population-based payments that adhere to these principles have the potential to provide practices with the flexibility to invest in the resources and supports needed to care for their patients using the approach or model that works best for them and their patients—including the implementation of lifestyle medicine principles.

Value-Based Primary Care and Lifestyle Medicine: Better Together

Despite the many challenges stemming from underinvestment and poorly designed payment models, primary care is the only health care component for which increased supply is associated with more equitable outcomes, lower mortality rates, reduced per capita health care spending, and less use of high cost services, such as hospitalizations and emergency room visits.10,54 On an individual patient level, primary care teams form enduring relationships with their patients to comprehensively treat and manage acute and chronic conditions in the context of a person’s overall health and community, coordinate care across the team, address unmet social needs, and optimize a patient’s health in a way that is meaningful to them.

Resourced by value-based payment models that are sufficiently funded and flexible in nature to allow for alternative models of care delivery, integrating lifestyle medicine principles has the potential to enhance care delivery outcomes for both patients and clinicians in a number of ways.

Manage Cost of Care

Lifestyle medicine focuses on addressing the root causes of disease instead of medicating and managing symptoms and that is why it is considered inherently high-value care. In the long run, improving the health behaviors of patients is one of the most effective ways to reduce the total cost of care, especially for some of the costliest patients—those with chronic diseases. By emphasizing healthy behaviors over costly procedures and medications, physicians engaged in value-based care can lower health care costs while still maintaining high-quality standards and improve outcomes. 55

Over a five-year timeframe, a self-insured health plan recorded substantial enhancements in biometric markers for members who had hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes participating in a holistic medicine implementation, medication optimization, and care coordination program. These enhancements entailed a decrease in LDL levels, an increase in HDL levels, and a decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. The program showcased a combined healthcare and productivity return on investment worth $9.64 for every $1 invested. 56 Vanderbilt University conducted another study that displayed improvements in HBA1C, total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides for participants enrolled in a CHIP lifestyle program for employees. Moreover, survey responses indicated progress in life evaluation, physical health, emotional health, healthy behaviors, work environment, basic access, and a well-being index. The program resulted in a net savings worth $67,582 in healthcare costs for the system, representing a six-month ROI of approximately 2.1:1. 57 Additionally, the Ornish ICR program was able to reduce costs worth 47% over a three-year duration by avoiding revascularization procedures. 58

Address Primary Care Workforce Shortage

The primary care workforce is in a fragile state. The 2023 America Health Rankings report states that the overall primary care workforce decreased by 13% (from 265.3 to 232.0 providers per 100,000 population) between 2022 and 2023. 59 The practice of lifestyle medicine, with its holistic and patient-centered approach, has the potential to offer physicians and their teams a more gratifying care experience. By delving beyond the mere treatment of symptoms and instead addressing the underlying causes of health problems, physicians and other clinicians can achieve a deeper sense of satisfaction with their work. Additionally, adopting lifestyle medicine practices can lead to enhanced patient interactions and outcomes, ultimately resulting in a more fulfilling and rewarding experience for all members of the healthcare team.

A recent study reveals that practitioners of Lifestyle Medicine who integrated it into their clinical practices reported reduced burnout. Impressively, 90% of participants claimed that Lifestyle Medicine positively affected their professional satisfaction. 60 Lifestyle medicine can play a central role in informing physicians and other health care providers about healthy lifestyle to help protect against and decrease the effects of burnout. A vast amount of literature confirms that positive lifestyle factors offer dramatic improvement to health and lower risk factors for chronic disease. Lifestyle medicine offers an opportunity for physicians to find joy and meaning in their profession again. 42

Address Health Disparities and Promote Health Equity

Lifestyle medicine has the potential to address health disparities by focusing on the social determinants of health and considering individual and community contexts. It recognizes that factors such as socioeconomic status, access to healthy food, safe neighborhoods, and education influence health outcomes. By addressing chronic diseases through lifestyle behavior, lifestyle medicine is a promising approach for addressing health disparities and achieving health equity.55,61 Community-engaged lifestyle medicine (CELM) is an evidence-based, participatory framework capable of addressing health disparities through LM, targeting health equity in addition to better health. The framework includes the following evidence-based principles: community engagement, cultural competency, and application of multilevel and intersectoral approaches. 62

Realizing these benefits requires overcoming headwinds and challenges that complicate the integration of lifestyle medicine in a more traditional practice setting.

Risk Adjustment

Lifestyle medicine practitioners prioritize disease reversal or remission, when appropriate for the patient, over managing disease with ever-increasing quantities of costly medications and procedures. Unfortunately, many risk adjustment methodologies, including hierarchical condition category coding, incentivize identification and management of the disease rather than encouraging health restoration. A primary care physician using a therapeutic dose of lifestyle medicine to achieve remission in a patient with type 2 diabetes is penalized financially because reduced risk results in lower payments. Corresponding incentives for improved outcomes to offset this loss do not exist in most value-based payment arrangements. This misalignment results in an inordinate amount of energy focused on identifying, diagnosing and managing disease relative to the amount expended on achieving remission or reversing the disease course. 63

Misaligned Quality Measures

There are certain metrics that are designed to measure processes for non-LM interventions, like medication adherence. However, these metrics can discourage LM practices, such as deprescribing. For instance, an LM physician may receive lower star ratings for not prescribing a statin medication for hyperlipidemia, even if they have achieved optimal health outcomes at a lower cost without medication. This misalignment does not incentivize patient-centered care because it disregards patient preference, shared decision-making, and evidence-based practice. 63

Gaps in Current Quality Measures

Clinical practice guidelines for many chronic diseases recommend lifestyle intervention as the first line of treatment. A growing body of evidence supports lifestyle behavior interventions to treat and, when used intensively, even reverse common chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, obesity and type 2 diabetes while also providing effective prevention for those conditions. However, no current quality measures consider lifestyle interventions as a first line of interventions for chronic disease management. 63

Moving Forward Together

Implementing high-quality primary care in the US requires new solutions and strategies applied to long-term, persistent problems. Thinking outside the box and looking beyond the labels routinely applied to care delivery “models” is one strategy that has the potential to unleash the most fundamental and powerful aspects of lifestyle medicine in a wide range of primary care settings. There are some tailwinds that are worth noting.

Well-designed value-based payment can facilitate development of the teams and workflow changes required to support high-quality, whole-person primary care are increasingly available

While it has been slow coming and there is still a long way to go as evidenced by the HCP-LAN progress report, there is reason to believe that value-based payment well-designed for primary care is on the rise and will continue to trend in the right direction. The latest CMMI primary care payment model, Making Care Primary, represents one example of movement in the right direction. This new model that is available in 8 states or regions offers primary care practices the ability to shift its revenue model from an emphasis on undervalued fee-for-service reimbursement toward more sufficiently funded prospective population-based payments. By offering primary care practices the ability to onboard into this ten-year demonstration model, they are afforded not only the opportunity to make the transformations required to adapt to this new flexible revenue stream but are also given adequate time to realize the anticipated outcomes of better health at an improved per capita cost of care and an improved experience for patients and the teams that care for them. While the proof is in the pudding, there are reasons to be optimistic about this new payment opportunity.

Improving the well-being of primary care clinicians and preserving this fragile workforce by infusing lifestyle medicine approaches into more traditional primary care practice settings has demonstrated success and should be more widely scaled

Physician burnout is a matter of significant concern across the healthcare delivery system, but it is especially dire for primary care with the shortage of primary care physicians estimated to be as high as 48,000 by 2034. 64 The shortage is attributable to many factors, but chief among them is the level of burnout experienced by primary care physicians who are reporting higher levels relative to other specialties and are leaving clinical practice at unsustainable rates.59,65 This is a complex problem that can only be solved with a broad array of policy, market, and practice-based solutions. Given the high degree of satisfaction experienced by physicians and other clinicians who have incorporated lifestyle medicine into their clinical practice, this represents a potential opportunity to improve the professional well-being of primary care physicians. In a recent survey of ACLM members designed to understand the role that incorporating lifestyle medicine played in addressing physician burnout and improving professional well-being, almost 90% of survey respondents (more than half of whom were physicians in primary care specialties) reported that integrating lifestyle medicine into their clinical practice had positively impacted their professional satisfaction. A sense of accomplishment and meaningfulness, improved patient outcomes and satisfaction, as well as the enjoyment of teaching/coaching were all contributors to improved professional satisfaction. It is worthwhile noting that more than two-thirds of the survey respondents state they are not certified in lifestyle medicine and are applying lifestyle medicine selectively in their practice, yet they and their patients are reaping benefits they attribute to the integration of lifestyle medicine in their practice. 60

Verbatim survey responses, such as “Being able to offer a way to avoid or reverse chronic disease rather than simply ‘moving chairs around on the deck of the Titanic’” reflect a renewed sense of empowerment. The professional satisfaction and joy in practice are also clear with statements such as “Truly helping patients with the root cause of their health issues, more rewarding than any other care that I have provided patients” and “To have a truck driver normalize his Hba1c from 11[%] in 3 months, it’s the biggest reward a primary care MD can get.”

Clinicians who possess the knowledge and skillset to integrate lifestyle medicine principles in practice can benefit from taking on value-based payment contracts. Prospective payments allow practices greater flexibility to design innovative care models including building interdisciplinary teams to address lifestyle behaviors. Some early adopters who have integrated lifestyle medicine approaches within value-based care models have demonstrated significant cost savings up to a 30%–40% reduction in the total cost of care in addition to improving their professional well-being. 66 The supplemental resource highlights three case studies of value-based primary care practices integrating lifestyle medicine principles. Common across all of these case studies is the role that lifestyle medicine plays in their success under value-based care contracts, in addition to the inherent benefits of improved patient satisfaction.

There are ample resources available to support primary care practices interested in incorporating lifestyle medicine principles into everyday practice

It is widely recognized that lifestyle medicine has the potential to address up to 80% of chronic illnesses. However, incorporating lifestyle medicine into patient care has been challenging due to various barriers already noted. One of the primary challenges is the lack of training that clinicians receive on how to effectively implement lifestyle medicine in practice, including utilizing interdisciplinary teams during patient visits. Additionally, delivering individualized and relationship-based care that respects shared decision-making requires more time. To overcome these challenges, both AAFP and ACLM have developed several free resources that primary care practices can use to integrate lifestyle medicine approaches into their practice. These resources include practice solutions, patient education resources, and implementation models. The shared interest of the AAFP and the ACLM in making these lifestyle medicine resources easily accessible is supporting practice’s ability to incorporate an array of strategies that can be adapted to their unique patient population needs and practice setting. (Included as supplemental material)

Conclusion

There are no definitive silver bullets or magic wands that will change the course for primary care. Many strategies and approaches are needed. The perspective that we offer in this article is that well-designed value-based payment (that we do not yet have enough of in the US) is highly compatible with the delivery of high quality, comprehensive, whole health care, aka value-based care, that can benefit by incorporating elements of lifestyle medicine. We must collectively be on guard and aware that the value movement is likely to plateau at some point in time if it’s all about the payment. We must bring an explicit focus on whole-person health and health care that can be delivered in a variety of ways, including by integrating lifestyle medicine principles into a variety of primary care practice settings.

The primary care community cannot afford to be divided by labels or camps—especially when the goals of the labels we align with (e.g., value-based care, lifestyle medicine, whole health care) are largely the same—improved health for individuals and populations, and better experience for patients, physicians, and care teams at a more affordable cost of care.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Whole Health Revolution: Value-Based Care + Lifestyle Medicine by Karen S. Johnson, and Padmaja Patel in American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Ron Stout for bringing us together to write this article.

Appendix

High Quality Primary Care (2021 National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine Consensus Report, Implementing High Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation)

The provision of whole person, integrated, accessible, and equitable health care by interprofessional teams who are accountable for addressing the majority of an individual’s health and wellness needs across settings and through sustained relationships with patients, families, and communities

*Whole-person health focuses on well-being rather than the absence of disease. It accounts for the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual health and the social determinants of health of a person.

Lifestyle Medicine (American College of Lifestyle Medicine)

Lifestyle medicine is a medical specialty that uses therapeutic lifestyle interventions as a primary modality to treat chronic conditions including, but not limited to, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Lifestyle medicine certified clinicians are trained to apply evidence-based, whole-person, prescriptive lifestyle changes to treat and, when used intensively, often reverse such conditions. Applying the 6 pillars of lifestyle medicine—a whole-food, plant-predominant eating pattern, physical activity, restorative sleep, stress management, avoidance of risky substances, and positive social connections—also provides effective prevention for these conditions.

Whole Health and Whole Health Care (2023 National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine Report, Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation)

Whole Health Care

Whole health care is an interprofessional, team-based approach anchored in trusted relationships to promote well-being, prevent disease, and restore health.

Whole Health

Whole health is physical, behavioral, spiritual, and socioeconomic well-being as defined by individuals, families, and communities.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Karen S. Johnson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0927-7503

References

- 1.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2008;27(3):759-769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new imperative to advance health equity. JAMA. 2022;327(6):521-522. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.25181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HCP-LAN . HCP-LAN Alternative Payment Model APM Framework. Baltimore, MD: Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network; 2017:47. https://hcp-lan.org/workproducts/apm-refresh-whitepaper-final.pdf, Accessed 8 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips RL, McCauley LA, Koller CF. Implementing high-quality primary care: a report from the national Academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine. JAMA. 2021;325(24):2437-2438. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baillieu R, Kidd M, Phillips R, et al. The Primary Care Spend Model: a systems approach to measuring investment in primary care. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(4):e001601. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke CA, Hauser ME. Lifestyle medicine: a primary care perspective. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):665-667. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00804.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Academies of Sciences . In: Meisnere M, South-Paul J, Krist AH, eds. Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Transforming Health Care to Create Whole Health: Strategies to Assess, Scale, and Spread the Whole Person Approach to Health. Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591730/, Accessed 19 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grega M. Expert consensus: lifestyle medicine in primary care. Am Coll Lifestyle Med. Published online November 7, 2023 https://lifestylemedicine.org/articles/ecs-lifestyle-medicine-in-primary-care/, Accessed 19 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider EC, Shah A, Doty MM, Tikkanen R, Fields K, Williams RD, II. Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2021. doi: 10.26099/01DV-H208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Sci Tech Rep. 2012;2012:432892. doi: 10.6064/2012/432892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid R, Damberg C, Friedberg MW. Primary care spending in the fee-for-service medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(7):977-980. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Conference on Primary Health Care Declaration of ALMA-ATA. The Lancet. 1978;312(8098):1040-1041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92354-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hone T, Macinko J, Millett C. Revisiting Alma-Ata: what is the role of primary health care in achieving the sustainable development goals? Lancet Lond Engl. 2018;392(10156):1461-1472. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31829-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabbarpour Y, Greiner A, Jetty A, et al. Investing in primary care: a state-level analysis. Primary care collaborative. 2019. https://www.graham-center.org/content/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/reports/Investing-Primary-Care-State-Level-PCMH-Report.pdf, Accessed 19 December 2023.

- 15.Jabbarpour Y, Petterson S, Jetty A, Byun H. The Health of US Primary Care: A Baseline Scorecard Tracking Support for High-Quality Primary Care. Washington, DC: Robert Graham Policy Center; 2023:25. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Milbank-Baseline-Scorecard_final_V2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):506-514. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Bruno R, Chung Y, Phillips RL. Higher primary care physician continuity is associated with lower costs and hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):492-497. doi: 10.1370/afm.2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson K, Rittenhouse D. From volume to value: progress, rationale, and guiding principles. Fam Pract Manag. 2023;30(1):5-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu S, Phillips RS, Song Z, Bitton A, Landon BE. High levels of capitation payments needed to shift primary care toward proactive team and nonvisit care. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2017;36(9):1599-1605. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 1990;336(8708):129-133. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91656-u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esselstyn CB, Gendy G, Doyle J, Golubic M, Roizen MF. A way to reverse CAD? J Fam Pract. 2014;63(7):356-364b. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galbete C, Kröger J, Jannasch F, et al. Nordic diet, Mediterranean diet, and the risk of chronic diseases: the EPIC-Potsdam study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1082-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panigrahi G, Goodwin SM, Staffier KL, Karlsen M. Remission of type 2 diabetes after treatment with a high-fiber, low-fat, plant-predominant diet intervention: a case series. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2023;17(6):839-846. doi: 10.1177/15598276231181574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1117-1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obarzanek E, Sacks FM, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood lipids of a blood pressure-lowering diet: the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74(1):80-89. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore TJ, Conlin PR, Ard J, Svetkey LP. DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet is effective treatment for stage 1 isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. 2001;38(2):155-158. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.2.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289(16):2083-2093. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, Marchie A, et al. Effects of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods vs lovastatin on serum lipids and C-reactive protein. JAMA. 2003;290(4):502-510. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.4.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Delaye J, Mamelle N. Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction: final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99(6):779-785. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.6.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280(23):2001-2007. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benigas S. American College of lifestyle medicine: vision, tenacity, transformation. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;14(1):57-60. doi: 10.1177/1559827619881094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. 2003;42(6):1206-1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trilk J, Nelson L, Briggs A, Muscato D. Including lifestyle medicine in medical education: rationale for American College of preventive medicine/American medical association resolution 959. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):e169-e175. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartzler ML, Shenk M, Williams J, Schoen J, Dunn T, Anderson D. Impact of collaborative shared medical appointments on diabetes outcomes in a family medicine clinic. Diabetes Educat. 2018;44(4):361-372. doi: 10.1177/0145721718776597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker R, Ramasamy V, Sturgiss E, Dunbar J, Boyle J. Shared medical appointments for weight loss: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2022;39(4):710-724. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmab105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watts SA, Strauss GJ, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes: glycemic reduction in high-risk patients. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(8):450-456. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noya C, Alkon A, Castillo E, Kuo AC, Gatewood E. Shared medical appointments: an academic-community partnership to improve care among adults with type 2 diabetes in California central valley region. Diabetes Educat. 2020;46(2):197-205. doi: 10.1177/0145721720906792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Law T, Jones S, Vardaman S. Implementation of a shared medical appointment as a holistic approach to CHF management. Holist Nurs Pract. 2019;33(6):354-359. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Znidarsic J, Kirksey KN, Dombrowski SM, et al. “Living well with chronic pain”: integrative pain management via shared medical appointments. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2021;22(1):181-190. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lianov L, Johnson M. Physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine. JAMA. 2010;304(2):202-203. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merlo G, Rippe J. Physician burnout: a lifestyle medicine perspective. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15(2):148-157. doi: 10.1177/1559827620980420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenz TL. Documenting lifestyle medicine activities. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014;8(4):242-243. doi: 10.1177/1559827614529071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dysinger WS. Lifestyle medicine prescriptions. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15(5):555-556. doi: 10.1177/15598276211006627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dysinger WS. Lifestyle medicine competencies for primary care physicians. Virtual Mentor VM. 2013;15(4):306-310. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.4.medu1-1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pany MJ, Chen L, Sheridan B, Huckman RS. Provider teams outperform solo providers in managing chronic diseases and could improve the value of care. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2021;40(3):435-444. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willard-Grace R, Hessler D, Rogers E, Dubé K, Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Team structure and culture are associated with lower burnout in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med JABFM. 2014;27(2):229-238. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.130215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.English AF. Team-based primary care with integrated mental health is associated with higher quality of care, lower usage and lower payments received by the delivery system. Evid Base Med. 2017;22(3):96. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2016-110587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner EH, Flinter M, Hsu C, et al. Effective team-based primary care: observations from innovative practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0590-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reiss-Brennan B, Brunisholz KD, Dredge C, et al. Association of integrated team-based care with health care quality, utilization, and cost. JAMA. 2016;316(8):826-834. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirsh SR, Aron DC, Johnson KD, et al. A realist review of shared medical appointments: how, for whom, and under what circumstances do they work? BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2064-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel P. Successful use of virtual shared medical appointments for a lifestyle-based diabetes reversal program. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15(5):506-509. doi: 10.1177/15598276211008396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacagnina S, Tips J, Pauly K, Cara K, Karlsen M. Lifestyle medicine shared medical appointments. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15(1):23-27. doi: 10.1177/1559827620943819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker R, Freeman GK, Haggerty JL, Bankart MJ, Nockels KH. Primary medical care continuity and patient mortality: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):e600-e611. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X712289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The Potential of Lifestyle Medicine as a HighValue Approach to Address Health Equity. Chesterfield, MO: Institute for Advancing Health Value, American College of Lifestyle Medicine; 2022:10. Accessed December 8, 2023.chrome-extension://efaidn. https://www.advancinghealthvalue.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Institute_IB_lifestyle-medicine-aclm-0922.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 56.White ND, Lenz TL, Skrabal MZ, Skradski JJ, Lipari L. Long-term outcomes of a cardiovascular and diabetes risk-reduction program initiated by a self-insured employer. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2018;11(4):177-183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shurney D, Hyde S, Hulsey K, Elam R, Cooper A, Groves J. Chip lifestyle program at vanderbilt university demonstrates an early roi for a diabetic cohort in a workplace setting: a case study. J Manag Care Med. 2012;15:5-15. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ornish D. Avoiding revascularization with lifestyle changes: the multicenter lifestyle demonstration project. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(10B):72T-76T. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00744-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.America’s Health Rankings Report . @United Health Foundation. All Rights Reserved. 2023:40. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/. Accessed 20 December 2023.

- 60.Pollard KJ, Gittelsohn J, Patel P, et al. Lifestyle medicine practitioners implementing a greater proportion of lifestyle medicine experience less burnout. Am J Health Promot AJHP. 2023;37(8):1121-1132. doi: 10.1177/08901171231182875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rooke J. Advancing health equity with lifestyle medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2018;12(6):472-475. doi: 10.1177/1559827618780680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krishnaswami J, Sardana J, Daxini A. Community-engaged lifestyle medicine as a framework for health equity: principles for lifestyle medicine in low-resource settings. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13(5):443-450. doi: 10.1177/1559827619838469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patel P. How PCPs are penalized for positive outcomes from lifestyle change. Medscape commentary. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/997218#vp_1?form=fpf, Accessed 8 December 2023.

- 64.IHS Markit Ltd . The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. Washington, D.C: AAMC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2020. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(3):491-506. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parkinson MD, Stout R, Dysinger W. Lifestyle medicine. Med Clin. 2023;107(6):1109-1120. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2023.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Whole Health Revolution: Value-Based Care + Lifestyle Medicine by Karen S. Johnson, and Padmaja Patel in American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine.