Abstract

Background

Lumbodorsal fasciitis (LF) is a condition in which muscle and fascial lesions cause low back pain (LBP) and limited mobility. This retrospective study aimed to explore the efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided fascial hydrodissection combined with eperisone for treating LF.

Material/Methods

A total of 103 patients with LF were selected and divided into a combined therapy (CT) group (ultrasound-guided fascial hydrodissection and oral drugs of eperisone) and single medication (SM) group (oral drugs of celecoxib and eperisone). Outcomes were evaluated using the visual analog scale (VAS) and Oswestry disability index (ODI) at baseline and at 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months after treatment. The adverse reactions and complications of the 2 groups were recorded.

Results

There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the 2 groups (P>0.05). After treatment, all scores showed a statistically significant improvement at 2 weeks and 1 month (P<0.05). The VAS and ODI scores showed a significant effect by time and group (P<0.001). The results also showed significant group-by-time interactions (P<0.001). Patients in the CT group had lower scores at any follow-up time (P<0.05). At 3 months, the scores slightly increased. There were no adverse reactions or complications in the CT group; however, the SM group had 4 cases of gastrointestinal reactions.

Conclusions

Ultrasound-guided fascial hydrodissection combined with eperisone therapy can effectively relieve LBP and improve lumbar function in treating LF. Moreover, this procedure is considered safe.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Interventional; Fascia; Fasciitis

Introduction

Lumbodorsal fasciitis (LF), also known as low back myofascial pain syndrome, is a common condition that leads to low back pain and limited mobility that significantly affects the quality of life of individuals [1]. While various treatment approaches exist, including medication, acupuncture, and physical therapy, their efficacy is often limited, and symptoms can recur [2–4]. Additionally, academics and doctors lack awareness regarding myofascial lesions of the lower back, as identified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound [5–8]. Therefore, there is a need for further research to explore more effective treatment options for LF.

One potential treatment approach is ultrasound-guided hydrodissection therapy, which has shown clinical efficacy in the treatment of nerve entrapment and myofascial pain syndromes [9–14]. However, few studies have investigated the efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided fascial hydrodissection combined with eperisone in treating LF. Furthermore, no studies have compared the advantages of this combination therapy with single medication treatment (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and skeletal muscle relaxants). Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of combination therapy for patients with LF, and to compare it with single medication treatment. By doing so, we hope to identify a more effective treatment approach that can reduce pain symptoms and improve the quality of life in patients with LF.

Material and Methods

Patients

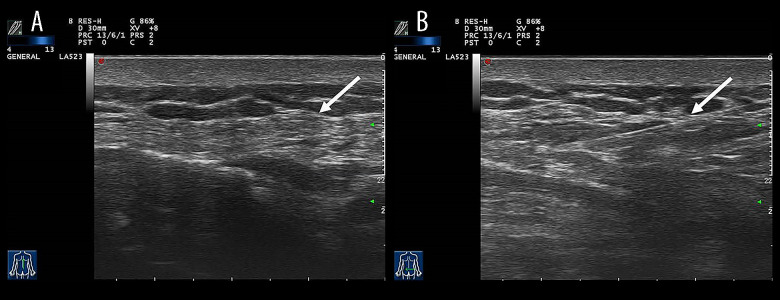

This was a retrospective study. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Rongjun Hospital. From October 2022 to October 2023, a total of 103 patients were enrolled and followed up. All were diagnosed with LF and treated with either combined therapy (CT group: ultrasound-guided fascial hydrodissection and oral application of eperisone) or single medication (SM group: oral application of celecoxib and eperisone). Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with typical symptoms were clinically diagnosed (tenderness, stiffness of low back soft tissue, nodular sensation at the painful site); (2) MRI suggested LF (Figure 1); and (3) ultrasound indicated the low back fascia thickening (Figure 2A). Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) previous treatment, such as steroid injection or drug therapy; (2) poor general condition, such as organ dysfunction or coagulation dysfunction; (3) unable to cooperate or tolerate the treatment; (4) acute inflammation around the treatment point; (5) prior history of low back trauma; and (6) history of intervertebral disc degeneration or osteoporosis.

Figure 1.

MRI of a patient with lumbodorsal fasciitis. (A) T1-weighted image in the sagittal plane of lumbar spine. (B) Dixon T2-weighted image in the sagittal plane of the lumbar spine. (Siemens Magnetom Avanto s1.5T).

Figure 2.

Ultrasound of a patient with lumbodorsal fasciitis. (A) The arrow shows the thickened lumbodorsal fascia. (B) The arrow shows the drug diffused in the lumbodorsal fascia. (Mylab Twice, Esaote).

Procedures

In the CT group, in addition to collecting the patient’s symptoms and MRI results, the clinician palpated the pain site of the patient’s low back to find nodular sensation and myofascial trigger points and marked them with a marker. Before the procedure, ultrasonography was performed by an ultrasound investigator experienced in the musculoskeletal ultrasound examination, using the Esaote Mylab Twice scanner with a 5–12-MHz linear array transducer (Mylab Twice, Esaote, Genova, Italy). The painful site was marked. Then, the probe was coated with medical ultrasonic couplant (Keppler-250, Zhejiang, China) and enclosed in a medical sterile protective cover. After sterilization of the patient’s skin, the probe was placed on the patient’s low back to search for therapeutic targets. Once the target was obtained, a 22-gauge needle was inserted into the thickened lumbodorsal fascia using an in-plane approach. Under the ultrasonic guidance, the injection (0.2 mL compound betamethasone injection+1 mL 2% lidocaine+8.8 mL normal saline) was administered between the pathological fascia of muscles (Figure 2B). Finally, the needle was withdrawn. The treatment point was pressed for 5 min, and a bandage was placed over the treatment point. To prevent infection, the wound was kept free from water for 1 day. The therapy was performed once a week for 2 weeks. At the same time, the patient was advised to take oral application of eperisone 3 times a day for 2 weeks. In the SM group, all patients took celecoxib once a day for 2 weeks and eperisone 3 times a day for 2 weeks.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures were taken at baseline (before treatment) and at 2, 4, and 12 weeks after treatment. The outcome measure of LBP was measured by the visual analog scale (VAS), with scores ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 for no pain and 10 for the worst pain [15]. Outcomes of functional disability were measured by the Oswestry disability index (ODI), scored between 0 and 50 points [16]. The higher the score, the higher the disability. Potential complications, such as gastrointestinal reaction, infection, or neurovascular damage, were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

All data analyses were performed by SPSS 22.0 software (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables with a normal distribution were presented as mean±standard deviation; categorical variables were described as frequency. The independent-sample t test was used for quantitative variables, and the chi-square test was used for determining categorical variables. In both groups, repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for the difference of the repeated outcome parameters between assessment points. A P value <0.05 was considered to be significant (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001).

Results

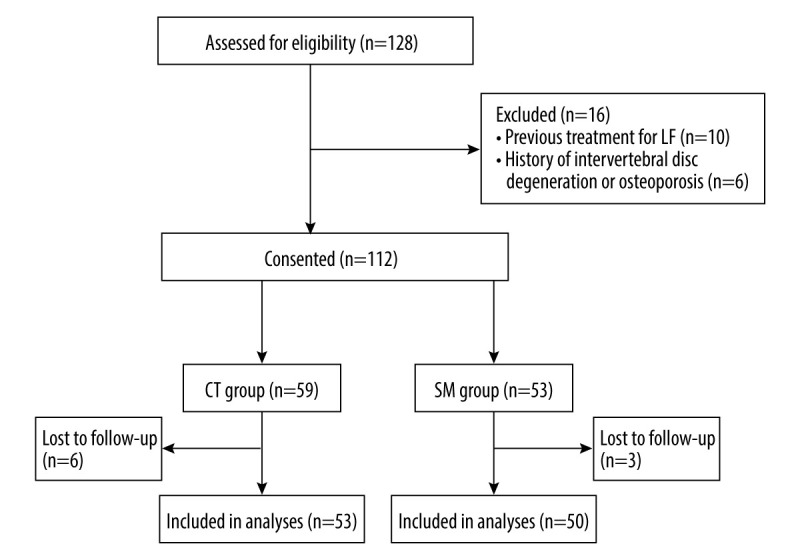

A total of 128 patients with LF who received treatment were initially enrolled in Zhejiang Rongjun Hospital from October 2022 to October 2023, and 103 patients were finally eligible, having had complete follow-up (Figure 3). There were 38 men and 65 women. The mean age was 55.53±8.20 years (range: 38–70 years). The mean duration of disease was 21.41±7.58 months (range: 6–36 months). The patients included those treated with combined therapy (CT group, n=53) and patients who received single medication (SM group, n=50). No significant difference was found in the baseline characteristic between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the study participants. (Microsoft 365 Office program, Microsoft Corporation). LF – lumbodorsal fasciitis; CT group – combined therapy group; SM group – single medication group.

Table 1.

General information of patients in the combined therapy (CT) group and single medication (SM) group.

| CT group (n=53) | SM group (n=50) | t/χ2 (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old, χ̆±s) | 56.44±8.87 | 54.76±7.49 | 0.929 (0.355) |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 17/36 | 21/29 | 1.088 (0.297) |

| Duration (month, χ̆±s) | 22.53±7.77 | 20.22±7.26 | 1.556 (0.123) |

CT group – combined therapy group; SM group – single medication group.

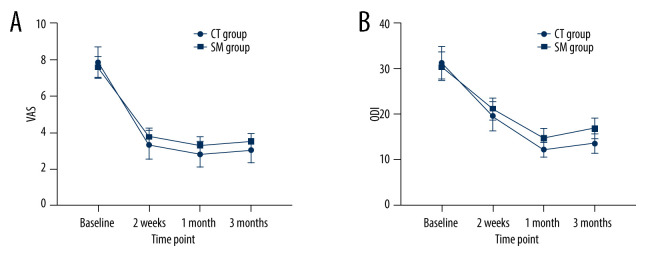

The VAS and ODI scores of the CT group were significantly lower than those in the SM group at all follow-up time points (all P<0.05). At 3 months, both groups’ scores slightly increased. The results showed significant effect of time and group in all outcome measurements (all P<0.001). This means that, compared with pretreatment, all outcome measures improved in both groups with time. Also, there were differences in the reduction of scores between the 2 groups. Group-by-time interactions were significant for VAS and ODI scores between the groups (P<0.001). The details of the intergroup comparison are summarized in Tables 2, 3, and Figure 4.

Table 2.

Visual analog scale (VAS) scores of patients in the combined therapy (CT) group and single medication (SM) group at different time points (χ̆±s).

| CT group (n=53) | SM group (n=50) | t(p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 7.83±0.86 | 7.59±0.56 | 1.676 (0.093) |

| 2 weeks | 3.31±0.79 | 3.76±0.47 | −3.571 (=0.001**) |

| 1 month | 2.78±0.69 | 3.28±0.48 | −4.283 (<0.001***) |

| 3 months | 2.99±0.66 | 3.47±0.46 | −4.265 (<0.001***) |

| F value | 904.955 | 980.877 | |

| P value | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | |

| Group F(p) | 9.059 (=0.009**) | ||

| Time F(p) | 1840.559 (<0.001***) | ||

| Time*group F(p) | 11.575 (<0.001***) | ||

VAS – visual analog scale; CT group – combined therapy group; SM group – single medication group.

Table 3.

Oswestry disability index (ODI) scores of patients in the combined therapy (CT) group and single medication (SM) group at different time points (χ̆±s).

| CT group (n=53) | SM group (n=50) | t(p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 31.3±03.66 | 30.52±3.20 | 1.152 (0.252) |

| 2 weeks | 19.55±3.18 | 21.18±2.42 | −2.920 (0.004**) |

| 1 month | 12.19±1.68 | 14.76±2.14 | −6.803 (<0.001***) |

| 3 months | 13.53±2.42 | 16.86±2.24 | −7.710 (<0.001***) |

| F value | 658.434 | 594.183 | |

| P value | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | |

| Group F(p) | 15.197 (<0.001***) | ||

| Time F(p) | 1157.372 (<0.001***) | ||

| Time*group F(p) | 15.636 (<0.001***) | ||

ODI – Oswestry disability index; CT group – combined therapy group; SM group – single medication group.

Figure 4.

Comparison of visual analog scale (VAS) and Oswestry disability index (ODI) scores between the combined therapy (CT) group and single medication (SM) group. (GraphPad Prism, 9.5, GraphPad Corporation).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that patients with LF had significant improvement and no adverse reactions or serious complications in the CT group. Notably, our research specifically addressed the effect of this combined therapy on pain relief and lumbar function improvement. By focusing on these objectives, we provided targeted insights into the potential benefits of this therapeutic approach.

Clinically, myofascial pain syndrome has recently focused on fascia [17–20]. In this study, the pathological manifestation of fascia is edema and exudation first, then adhesion, fibrosis, and thickening, which stimulates and oppresses the adjacent muscle and nerve. Additionally, Kondrup et al and Tesarz et al demonstrated that thoracolumbar fascia is an important source of LBP, due to its dense innervation [18,21]. Therefore, the above pathologic manifestations and findings well explain the symptoms experienced by patients in our research. Similar to our study, Langevin’s research team found that people with chronic LBP had increased fascial echogenicity and thickness, providing evidence for LF pathology [22]. Currently, many treatment methods exist for LF; however, patients are prone to experience recurrence [23,24]. The fundamental reason is that they cannot root out adhesion, fibrosis, and nerve entrapment. In reviewing several studies, we determined the efficacy and safety of the ultrasound-guided hydrodissection technique [25]. Based on this, we believe that the curative effect of the hydrodissection technique in treating LF merits validation.

Our findings indicated that the CT group showed significant improvements in VAS and ODI scores, compared with those in the SM group. The remarkable efficacy of the combined therapy can be attributed to several key points. First, in the CT group, we used the hydrodissection technique as a minimally invasive approach that effectively preserves the neurovascular structure, lyses fibrotic adhesion, and expands tissue space by utilizing solution pressure to separate fascia, nerve, or adjacent structures [26–29]. Second, the injections comprise small quantities of lidocaine and compounded betamethasone, which are known to induce vasodilation and mitigate aseptic inflammation. Third, all patients in this study were administered eperisone, which has been shown to alleviate skeletal muscle tension and has been applied to the treatment of LBP [30]. Finally, in our study, we used the ultrasound-guided fascia hydrodissection technique. Ultrasound not only accurately identifies the pathological lumbodorsal fascia but also provides real-time, precise guidance for the treatment pathway.

Our findings aligned with previous studies in reducing pain that highlight the efficacy of the ultrasound-guided hydrodissection technique in myofascial pain syndrome of the gastrocnemius and the trapezius muscles [31,32]. A double-blind randomized controlled trial conducted by Tantanatip et al showed that physiological saline interfascial injection reduced pain in patients with myofascial pain syndrome when compared with lidocaine injection [33]. However, the follow-up period for this study was limited to 4 weeks. Kongsagul et al showed that the ultrasound-guided physiological saline injection technique demonstrated pain reduction, by retrospectively reviewing 142 patients’ treatment [34]. However, there was no comparison of this procedure with alternative treatments, which could affect the result. Suarez-Ramos et al concluded that interfascial hydrodissection with the use of saline anesthetic solution provided a considerable period of pain relief for up to 6 months [35]. There are some differences between our study and previous investigations. First, our study is among the first to apply the fascial hydrodissection technique specifically to LF. Second, we innovatively compared the efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided fascia hydrodissection combined with eperisone versus the oral application of celecoxib and eperisone.

There were also several limitations in this study. First, the follow-up period was only 3 months, which is insufficient to assess the longer therapeutic effect. Second, shear wave elastography change of lumbar fascia was not considered, which could provide additional insights into the ultrasound-guided fascial hydrodissection therapy. Third, classification regarding age, course of disease, and efficacy was not performed, which could cause a certain deviation in the result. Finally, the lack of comprehensive therapy, including rehabilitation and physical therapy, can have an effect on the curative effect of LF. Therefore, further studies should address these limitations by incorporating a longer follow-up period, shear wave elastography of lumbar fascia, precise classification of the disease, and comprehensive treatment. We believe that future studies could advance this field and improve therapy for patients with LF.

Conclusions

Ultrasound-guided fascial hydrodissection combined with medication was an effective and safe procedure in pain relief and lumbar function improvement for LF and had better treatment benefits than single medication. However, the longer-term efficacy needs to be further discussed.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Department and Institution Where Work Was Done: Department of Ultrasound Intervention and Orthopedics, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, Zhejiang Rongjun Hospital, Zhejiang, China.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity: All figures submitted have been created by the authors, who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

Financial support: This study was supported by the key supporting discipline projects of Zhejiang Rongjun Hospital (No. 2023YJXK003)

References

- 1.Ramsook RR, Malanga GA. Myofascial low back pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(5):423–32. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0290-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galasso A, Urits I, An D, et al. A comprehensive review of the treatment and management of myofascial pain syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020;24(8):43. doi: 10.1007/s11916-020-00877-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sousa FL, Barbosa SM, Dos SG, et al. Corticosteroid injection or dry needling for musculoskeletal pain and disability? A systematic review and GRADE evidence synthesis. Chiropr Man Therap. 2021;29(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12998-021-00408-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urits I, Burshtein A, Sharma M, et al. Low back pain, a comprehensive review: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(3):23. doi: 10.1007/s11916-019-0757-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song MX, Yang H, Yang HQ, et al. MR imaging radiomics analysis based on lumbar soft tissue to evaluate lumbar fascia changes in patients with low back pain. Acad Radiol. 2023;30(11):2450–57. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2023.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langevin H, Fox J, Koptiuch C, et al. Reduced thoracolumbar fascia shear strain in human chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12(1):203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarz-Nemec U, Friedrich KM, Arnoldner MA, et al. When an incidental MRI finding becomes a clinical issue: Posterior lumbar subcutaneous edema in degenerative, inflammatory, and infectious conditions of the lumbar spine. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2020;132(1–2):27–34. doi: 10.1007/s00508-019-01576-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma K, Zhuang ZG, Wang L, et al. The Chinese Association for the Study of Pain (CASP): Consensus on the assessment and management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Pain Res Manag. 2019;2019:8957847. doi: 10.1155/2019/8957847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domingo T, Blasi J, Casals M, et al. Is interfascial block with ultrasound-guided puncture useful in treatment of myofascial pain of the trapezius muscle? Clin J Pain. 2011;27(4):297–303. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182021612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buntragulpoontawee M, Chang KV, Vitoonpong T, et al. the effectiveness and safety of commonly used injectates for ultrasound-guided hydrodissection treatment of peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes: A systematic review. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:621150. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.621150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura H, Kobayashi T, Zenita Y, et al. Expansion of 1 mL of solution by ultrasound-guided injection between the trapezius and rhomboid muscles: A cadaver study. Pain Med. 2020;21(5):1018–24. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozyemisci TO, Albayrak H, Topaloglu M, et al. Effect of ultrasound-guided rhomboid interfascial plane block on pain severity, disability, and quality of life in myofascial pain syndrome – a case series with one-year follow-up. Pain Physician. 2023;26(7):e815–e22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu YC, Yang FC, Hsu HH, et al. Median nerve injury in ultrasound-guided hydrodissection and corticosteroid injections for carpal tunnel syndrome. Ultraschall Med. 2022;43(2):186–93. doi: 10.1055/a-1140-5717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiang CF, Cheng SH, Wu CH, et al. Video demonstration of ultrasound-guided hydrodissection for superficial peroneal nerve entrapment. Pain Med. 2020;21(7):1509–10. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiarotto A, Maxwell L J, Ostelo R W, et al. Measurement properties of visual analogue scale, numeric rating scale, and pain severity subscale of the brief pain inventory in patients with low back pain: A systematic review. J Pain. 2019;20(3):245–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smeets R, Koke A, Lin CW, et al. Measures of function in low back pain/disorders: Low Back Pain Rating Scale (LBPRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Progressive Isoinertial Lifting Evaluation (PILE), Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS), and Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S158–73. doi: 10.1002/acr.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stecco A, Gesi M, Stecco C, et al. Fascial components of the myofascial pain syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17(8):352. doi: 10.1007/s11916-013-0352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondrup F, Gaudreault N, Venne G. The deep fascia and its role in chronic pain and pathological conditions: A review. Clin Anat. 2022;35(5):649–59. doi: 10.1002/ca.23882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salavati M, Akhbari B, Ebrahimi TI, et al. Reliability of the upper trapezius muscle and fascia thickness and strain ratio measures by ultrasonography and sonoelastography in participants with myofascial pain syndrome. J Chiropr Med. 2017;16(4):316–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baltazar MCDV, Russo JAO, De Lucca V, et al. Therapeutic ultrasound versus injection of local anesthetic in the treatment of women with chronic pelvic pain secondary to abdominal myofascial syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):325. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01910-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesarz J, Hoheisel U, Sensory Wiedenhofer B, et al. Innervation of the thoracolumbar fascia in rats and humans. Neuroscience. 2011;194:302–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langevin H, Stevens-Tuttle D, Fox J, et al. Ultrasound evidence of altered lumbar connective tissue structure in human subjects with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Huang QM, Liu QG, et al. Evidence for dry needling in the management of myofascial trigger points associated with low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(1):44–152. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geng T, Lin D, Fu B, Wang H, Wan J. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of low back fasciitis. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15(8):5486–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin JS, Gimarc DC, Adler RS, et al. Ultrasound-guided musculoskeletal injections. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2021;25(6):769–84. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1740349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bokey EL, Keating JP, Zelas P. Hydrodissection: An easy way to dissect anatomical planes and complex adhesions. Aust NZJ Surg. 1997;67(9):643–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb04616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arici T. Ultrasound-guided interfascial blocks of the trapezius muscle for cervicogenic headache: A report of 2 cases. Agri. 2021;33(4):278–81. doi: 10.14744/agri.2020.08831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Godek P, Paprocka-Borowicz M, Ptaszkowski K. Comparative efficacy of ultrasound-guided cervical fascial infiltration versus periarticular administration of autologous conditioned serum (orthokine) for neck pain: A randomized controlled trial protocol description. Med Sci Monit. 2024;30:e942044. doi: 10.12659/MSM.942044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cass SP. Ultrasound-guided nerve hydrodissection: What is it? a review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2016;15(1):20–22. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bavage S, Durg S, Ali KS, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of eperisone for low back pain: A systematic literature review. Pharmacol Rep. 2016;68(5):903–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park SM, Cho YW, Ahn SH, et al. Comparison of the effects of ultrasound-guided interfascial pulsed radiofrequency and ultrasound-guided interfascial injection on myofascial pain syndrome of the gastrocnemius. Ann Rehabil Med. 2016;40(5):885–92. doi: 10.5535/arm.2016.40.5.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arici T, Koken IS. Results of ultrasound-guided interfascial block of the trapezius muscle for myofascial pain. Agri. 2022;34(3):187–92. doi: 10.14744/agri.2021.98048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tantanatip A, Patisumpitawong W, Lee S. Comparison of the effects of physiologic saline interfascial and lidocaine trigger point injections in treatment of myofascial pain syndrome: A double-blind randomized controlled Trial. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. 2021;3(2):00119. doi: 10.1016/j.arrct.2021.100119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kongsagul S, Vitoonpong T, Kitisomprayoonkul W, et al. Ultrasound-guided physiological saline injection for patients with myofascial pain. J Med Ultrasound. 2020;28(2):99–103. doi: 10.4103/JMU.JMU_54_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suarez-Ramos C, Gonzalez-Suarez C, Gomez IN, et al. Effectiveness of ultrasound guided interfascial hydrodissection with the use of saline anesthetic solution for myofascial pain syndrome of the upper trapezius: A single blind randomized controlled trial. Front Rehabil Sci. 2023;4:1281813. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1281813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]