Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this qualitative study is to demonstrate the use of patient-reported outcome measure-based journey maps in facilitating clinicians’ ability to communicate with patients about their well-being at each phase of their cancer journey.

Methods

Individual semi-structured online and phone interviews were conducted with older adults in British Columbia, Canada. Participants (n = 6) were asked to describe their cancer experiences associated with their well-being score using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System revised questionnaire throughout their cancer journey (i.e., pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, to post-treatment).

Results

Six older adults who received cancer treatment were interviewed. Six journey maps were developed with evidence of fluctuation in participants’ level of well-being through their cancer journeys.

Conclusion

Journey maps can facilitate patient-clinician communication for tailoring interventions and draw clinicians’ attention to additional prompts to better understand patients’ well-being throughout the cancer journey.

Keywords: patient-reported outcome measures, journey maps, radiation therapy, cancer care, older adults

BACKGROUND

The number of people diagnosed with cancer worldwide is projected to increase from the current 19.3 million to 28.4 million by 2040 (Ferlay et al., 2021; Sung et al., 2021), with predictions of increasing survival rates for most cancers (Siegel et al., 2022). Older adults constitute one of the fastest-growing subgroups accounting for nearly 67% of new cancer cases (Pilleron et al., 2019).

As advances in cancer treatment continue to improve, well-being is increasingly recognized as an important outcome (Niedzwiedz et al., 2019; Sibeoni et al., 2018). Well-being encompasses life satisfaction and happiness, and can be assessed by asking how a person feels overall (Diener, 1984). Poor well-being is common and often overlooked during the treatment of patients with cancer. It has been negatively associated with treatment adherence and survival (Chen et al., 2018; Mols et al., 2013), as well as increased healthcare use and costs (Mausbach et al., 2020). In addition, fluctuations in levels of well-being are common, as patients move through the four phases of the cancer journey (e.g., pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, post-treatment; Dinesh et al., 2021; Rutherford et al., 2020), resulting in differences in individuals’ perceived level of well-being across their cancer experiences.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), questionnaires that enable patients to directly report on aspects of their health, provide a quick and measurable way to assess and monitor patients’ well-being (Bottomley et al., 2019; Graupner et al., 2021). However, PROMs often lack the contextual nuances necessary to understand the reasons behind changes in patients’ well-being scores over time. This absence of detailed insight creates a divide between the data gathered from PROMs and the intricate narratives within patients’ experiences. Without a deeper understanding of these narratives, clinicians may face challenges in recognizing and addressing the unique care needs of each individual, potentially impeding the delivery of truly person-centred care.

One approach to capture and explore individual patients’ dynamic circumstances is journey mapping. Based on the tenets of patient-oriented design, journey mapping is an approach adapted from customer service and marketing research to generate insights into the patient experience with healthcare service use (McCarthy et al., 2016). A journey map is a visualization of a patient’s experiences through complex situations or encounters over time (Davies et al., 2023; Gibbons, 2018; Joseph et al., 2022; McCarthy et al., 2016). Previous studies have used journey maps to improve the delivery of health services, follow-up care, and educational interventions for patients (Maddox et al., 2019; Philpot et al., 2019). Journey maps can be used as educational tools for clinicians to contextualize how PROM well-being scores change over time and facilitate understanding of the differences in cancer journeys from the patients’ point of view.

Our purpose is to demonstrate how PROM-based (well-being scores) journey maps can be used to facilitate clinicians’ ability to communicate with patients about their well-being at each phase of the cancer journey. The objective of this study was to develop journey maps to visualize the experiences of older adult patients who received cancer treatment across four phases of the cancer journey: 1) pre-diagnosis, 2) diagnosis, 3) treatment, and 4) post-treatment. The outcome is to promote person-centred care by using journey maps as a tool to facilitate clinicians’ ability to communicate with patients about their well-being at each phase of their cancer journey.

METHODS

Study design

This was a qualitative description study (Bradshaw et al., 2017) with semi-structured interviews guided by a collaborative patient engagement strategy (Gagliardi et al., 2016). Two older patient partners who have experience living with cancer were involved in identifying recruitment strategies, provided input on the recruitment poster and the interview guide, and participated in research team meetings and practice interviews. The University of British Columbia Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the study.

Participants and recruitment

Study participants were recruited through newsletters and from community organizations located in British Columbia (BC), Canada (e.g., Self-management BC, Eldercare Foundation, Prostate Cancer Foundation BC) between September and December 2022. Participants were eligible to participate if they (a) were diagnosed with cancer at or after 65 years of age, (b) received radiation therapy as part of their cancer treatment, and (c) were residents of BC. Participants provided informed consent to be interviewed and received a $50 grocery store gift card as an honorarium.

Data collection procedures

The semi-structured interviews were conducted virtually over Zoom or by telephone by three research assistants (AJ, GI, MM) trained in qualitative interviewing. Each interview was approximately two hours in duration. The interview guide (see Appendix) was informed by our previous persona project focused on illustrating patients’ life stories and well-being scores (Kwon et al., 2023). The interview began by asking general questions about participants’ cancer journey experiences, starting with the pre-diagnosis phase (e.g., “Can you tell me about your pre-diagnosis experience? What was that like for you?”). Participants were then asked to rate their well-being at this phase by completing a well-being item from the revised Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS-r; Chang et al., 2000). The item asks respondents to rate their overall well-being on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 represents the best (highest) and 10 represents the worst (lowest) possible feeling of well-being. We used empathy mapping to contextualize the well-being scores, which is a design tool to gain deeper insight into the participants’ experiences by focusing on three categories: feeling/thinking, tasks/activities, and influences/supports (Gray et al., 2010). Some of the guiding questions in the feeling/thinking category were, “What were you thinking about at this time?” For the tasks/activities category, we asked, “What tasks were you trying to complete?” For influences/supports, we asked, “Were there particular people you went to for advice or support? Or places or activities you took part in that influenced how you were feeling or coping?” (see supplementary file of the interview guide). Similar questions were asked for the pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, and post-treatment phases of the cancer journey.

Data analysis

Participant demographics were recorded (e.g., age, sex, type of cancer). Based on published criteria, the ESAS-r well-being scores were categorized as high well-being if participants reported a score of 3 or less, moderate if scored between 4–6, and low well-being if scored 7 or greater (Selby et al., 2010). Each interview was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by research assistants. Interview transcripts were analyzed by the research team using qualitative description with thematic analysis (Bradshaw et al., 2017). Three researchers (AJ, JY, MM) began the analyses by independently reading the interview transcripts. The goal of the analyses was to understand better the unique health experiences of each participant by staying close to the original transcripts to ensure that the journey maps accurately represent participants’ experiences. Key descriptions of participants’ experiences during each phase of their cancer journey were developed, connected with their well-being scores, and mapped onto the empathy mapping categories of feeling/thinking, tasks/activities, and influences/supports. For example, when asked about their pre-diagnosis phase, a participant recounted “feeling scared and apprehensive” upon their doctor’s recommendation for a breast biopsy subsequent to a routine mammogram. This firsthand account was integrated into the feeling/thinking category of their pre-diagnosis experience. Our aim was to authentically capture participants’ experiences through their own words across each of the empathy mapping categories throughout the four phases of the cancer journey.

Following this process, initial journey maps were constructed by four researchers (AJ, GI, JY, MM). The opportunities-to-discuss-well-being section was developed by the research team to facilitate patient-clinician communication for tailoring interventions and draw clinicians’ attention to additional prompts to better understand patients’ well-being throughout the cancer journey. The journey maps, subsequently, were further refined based on input from the larger team (e.g., co-authors) as well as member checking with the participants.

Rigour was addressed by member checking and keeping an audit trail in capturing data collection and the analysis process (Bradshaw et al., 2017). The results led to the development of six journey maps, which were visualized using the UXPressia® software tool. Pseudonyms were used on the journey maps to protect privacy, while preserving the unique personal nature of participants’ experiences.

RESULTS

Six older adults (four women, two men) who received radiation therapy participated in the study. Participants were diagnosed with cancer between the ages of 69 and 81 years. At the time of the interviews, participants had undergone radiation therapy ranging from less than a year to four years prior. Two of the participants had prostate cancer, three had breast cancer, and one had uterine cancer. Most participants reported moderate to high well-being with scores between 0 to 6 across all phases of the cancer journey (pre-diagnosis to post-treatment), except for two participants who reported low well-being scores of 7 or greater during two or more phases (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ Demographics and Well-Being Scores

| Pseudonym | Age | Sex | Type of cancer | Occupation | Post treatment | Well-being Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Pre-diagnosis | Diagnosis | Treatment | Post-treatment | ||||||

| Shelley | 69 | Female | Breast | Retired | 4 years | 8 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

| Fiona | 69 | Female | Breast | Psychologist | 1 year | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Robin | 72 | Male | Prostate | Retired | 1 year | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Sharon | 79 | Female | Uterine | Homemaker | 1 year | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Mary | 81 | Female | Breast | Retired | 3 years | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

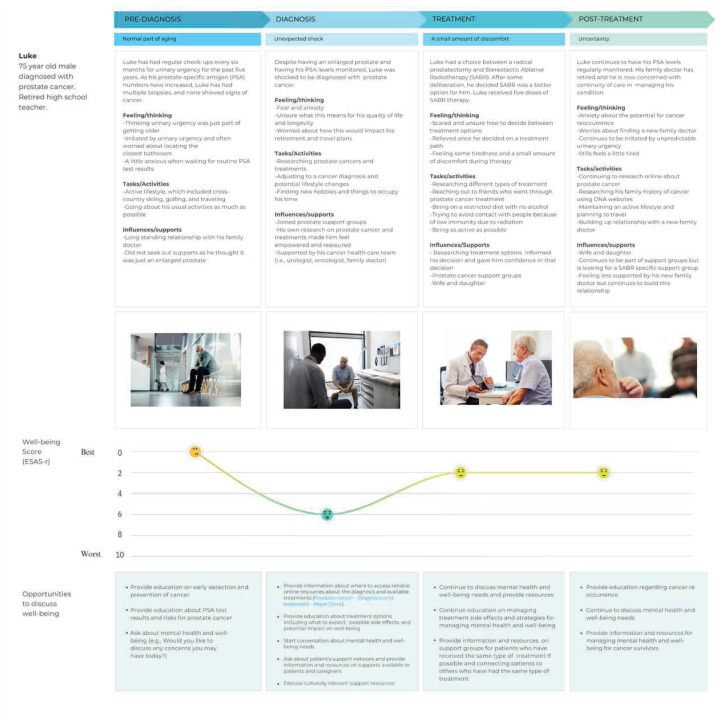

| Luke | 75 | Male | Prostate | Retired | < 1 year | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

Note: High well-being = 0–3; moderate well-being = 4–6; low well-being = 7–10.

We summarize below participants’ experiences (names are fictious) and reported well-being during each phase of their cancer journey, which are further contextualized by the journey maps in Figures 1 to 6.

Figure 1.

Fiona’s Journey Map

Figure 2.

Shelley’s Journey Map

Figure 3.

Robin’s Journey Map

Figure 4.

Sharon’s Journey Map

Figure 5.

Mary’s Journey Map

Figure 6.

Luke’s Journey Map

Pre-diagnosis

During the pre-diagnosis phase, most participants (n = 5) reported high levels of well-being (ranging from 0 to 2) and described going for a regular check-up for minor issues, which were deemed to be a normal part of aging.

While most participants reported feeling scared and apprehensive about getting further diagnostic testing, they did not expect abnormal results or a confirmed diagnosis of cancer. For example, Fiona (see Figure 1), who reported a high well-being score (2/10), was seeing her family doctor for her yearly mammogram exam and was recommended to have a breast biopsy. She felt a bit confused about this because she was not expecting an abnormal mammogram result.

Similarly, Luke (see Figure 6), who reported the highest well-being score (0/10), was having regular check-ups for urinary urgency and did not expect to have cancer based on the results of previous biopsies. Conversely, Shelley (see Figure 2), who reported a low well-being score (8/10), felt a lump in her breast and realized that she needed to have it checked out. Shelley described being particularly anxious, scared, and worried about not knowing what to expect and having difficulty cognitively processing that she might have cancer.

Diagnosis

During the diagnosis phase, four of the six participants reported moderate to low well-being (ranging from 4 to 10) and described feelings of shock, confusion, and anxiety about their cancer diagnosis. For example, Shelley (see Figure 2), who reported the lowest well-being score (10/10), was devastated by the diagnosis because she had been a healthy and active person. She did not know what to do and was unsure how to proceed living with cancer. Similarly, Fiona (see Figure 1), who reported the second lowest well-being score (8/10), was feeling overwhelmed by her diagnosis and the treatment information. She felt that decisions were being made too quickly and was wondering what else was going on that she did not know about.

In contrast, two participants reported high well-being scores (2/10) despite being diagnosed with cancer. For example, after receiving the news that his biopsy showed a small cancerous growth on his prostate gland, Robin (see Figure 3) felt a little surprised because he had not experienced any symptoms. While Robin was concerned about the side effects of the different treatment options, he was open with his family and friends about his diagnosis and carried on with his social life and hobbies. Likewise, after Mary (see Figure 5) received the results of her positive biopsy, she was not anxious or upset as she knew that her decision to take hormone replacement therapy for osteoporosis had increased her risk of breast cancer.

One participant, Sharon (see Figure 4), who reported moderate well-being (4/10), initially declined treatment when she received her uterine cancer diagnosis. Despite being encouraged by her partner, sons, and healthcare provider to have treatment, Sharon did not feel that she needed any treatment and accepted her cancer diagnosis because of her age. However, after collapsing several times and requiring a blood transfusion, Sharon decided to treat the cancer because she felt the blood she received should not be wasted.

Treatment

There was a wide range of well-being scores during the treatment phase, which ranged from the best possible well-being (0/10) to low well-being (8/10). Three participants (Mary, Luke, and Sharon) reported high scores. Mary (see Figure 5), with the highest well-being score (0/10), felt that radiation therapy was an interesting experience having received 16 doses over three weeks and had a positive outlook toward treatment. Mary tried not to focus on cancer but rather chose to focus on having a healthier diet to keep her energy level up. Similarly, both Luke and Sharon (see Figures 6 and 4, respectively) reported high well-being scores (2/10). Luke was initially unsure about how to decide between treatment options (i.e., radical prostatectomy and stereotactic ablative radiotherapy) and felt relieved once he decided on a treatment path. While Luke was feeling some tiredness and discomfort during treatment, he focused on being as active as possible while trying to avoid contact with people because of low immunity due to the radiation. Sharon felt good about receiving treatment and was thinking that she should have started her treatment earlier. While the cancer clinic was more than an hour away, Sharon was grateful that her son was there to take her to treatments and help at home.

Two other participants (Shelley and Robin) reported moderate well-being scores. Shelley (see Figure 2), who was staying at a cancer lodge while receiving radiation therapy because she lived far from the cancer treatment centre, reported a well-being score of 6/10. She felt lonely at the lodge, often feeling tired with low energy, and was upset about having to receive additional radiation booster treatments. She spent a lot of time reading and resting, and video calls from her daughter and granddaughter improved her spirits. Robin (see Figure 3), who reported a well-being score of 4/10, worried about bathroom breaks during the long drive to and from the cancer treatment centre. He felt a little concerned about radiation therapy but had many supports in place, including his wife, family, and friends who had gone through cancer experiences. Robin was also in close contact with the doctor leading the research study in which he was enrolled.

Amongst all the participants, Fiona (see Figure 1) reported having the lowest well-being (8/10) during treatment. She described feeling exhausted and did not feel adequately informed about the side effects of having short and intensive radiation therapy. Fiona continued to work and care for her ill husband during her treatment, which contributed to her exhaustion.

Post-Treatment

Most participants (n = 5) reported high well-being scores (0 to 2) during the post-treatment phase, which was attributed to being able to return to their pre-cancer routines and outlook on life. For example, Mary (see Figure 5), who reported the best possible well-being score (0/10), felt positive overall as her cancer treatment went well. She focused on getting back to her normal pre-cancer routine, connecting with family and friends, and getting outside more often. Likewise, Shelly (see Figure 2), who reported a high well-being score of 2/10, felt that her life has returned to normal and looks forward to golfing, gardening, and travelling. While some participants who reported high well-being scores felt that their lives had more or less returned to normal, others indicated they continued to have concerns about their health. For instance, Luke (see Figure 6) who reported a well-being score of 2/10, was in the process of finding a new family doctor and as a result, was concerned about managing his health and continuity of care. He continues to have his PSA levels monitored with some worries about the potential for cancer reoccurrence.

In contrast to the above participants who reported high well-being scores post-treatment, Fiona (see Figure 1) continued to rate her well-being as low (8/10). This was a product of her feeling “burnt out” from treatment, being exhausted from work, and being concerned about her husband’s health.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates how journey maps can be used to facilitate understanding of well-being scores by shedding light on the diverse and complex lives of individuals facing various phases of their cancer journey.

Pre-diagnosis and diagnosis phases

During the pre-diagnosis phase, participants generally reported high levels of well-being, often attributing their symptoms to normal aspects of aging. However, underlying feelings of fear and uncertainty were evident as they underwent additional diagnostic tests. The experiences of Fiona, Luke, and Shelley exemplify the unexpected nature of abnormal results and the emotional turmoil associated with the possibility of a cancer diagnosis.

In the diagnosis phase, participants’ well-being scores varied more widely. While Shelley and Fiona grappled with profound shock and uncertainty, Robin and Mary continued to maintain high well-being scores despite the cancer diagnosis. Robin’s acceptance and Mary’s understanding of her increased risk due to previous treatments were notable contrasts to the struggles of others, such as Sharon’s initial hesitation towards treatment.

Treatment and post-treatment phase

In the treatment phase, participants showed a range of well-being scores that varied from 0 to 8. Mary, Luke, and Sharon demonstrated resilience in navigating treatment challenges, each finding their unique path to maintain a positive outlook. Mary’s dietary focus, Luke’s active engagement despite fatigue, and Sharon’s gratitude for familial support illustrate the use of diverse coping strategies. However, some participants experienced additional burdens accompanying treatment, including Shelley’s feelings of isolation, Robin’s concerns about treatment logistics (e.g., managing bathroom breaks during lengthy trips to and from treatment), and Fiona’s added responsibilities of work and caregiving.

In the post-treatment phase, a sense of relief and a desire to resume normal activities were prevalent with notably high well-being scores reported among most participants. For example, Mary and Shelley expressed joy in reclaiming aspects of their lives pre-cancer, engaging in activities that brought them fulfillment. However, lingering concerns about health and potential cancer recurrence persisted for some, indicating the ongoing emotional journey of cancer survivors.

Role of journey maps in enhancing patient-clinician communication with PROMs

The development of six journey maps from participant interviews offer an innovative approach for facilitating a more holistic and better understanding of PROM scores and the cancer journey from the patients’ point of view. While PROMs can be a valuable tool, the individual patient’s story or “narrative” is often lost in the numbers. Journey maps bridge this gap by bringing to life the underlying narrative and challenges that patients face as well as identifying potential opportunities for clinicians to discuss and address patients’ well-being. For example, Fiona’s low well-being score during the diagnosis phase (8/10), highlights the potential benefits of further discussions about treatment expectations, the possible side effects, and their impact on well-being. Similarly, Sharon’s moderate well-being score (4/10) during diagnosis suggests the need for extra support and assistance, particularly given her caregiving responsibilities. Giving context to patients’ PROM scores can be a valuable way for clinicians to detect overlooked problems and individualize care (Greenhalgh and Meadows, 1999; Lavallee et al., 2016).

Consistent with previous studies (Skovlund et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2018), these six journey maps highlight that further prompts and inquiry can help clinicians contextualize patients’ PROM well-being scores, facilitating patient-clinician communication for tailoring interventions. Specifically, during the pre-diagnosis phase, PROMs can be used to initiate conversations about well-being and establish rapport with patients, offering opportunities to discuss feelings of surprise or uncertainty they may be experiencing (e.g., “Your well-being score is X. What are you feeling that makes it less than the best?”). During the diagnosis phase, PROMs can be used to continue conversations about well-being and provide resources on mental health or caregiver supports that may be needed, particularly when patients do not recognize what they may need or are not forthcoming with the concerns for which they are struggling with (e.g., “What’s causing you to rate your well-being as X right now?”). During treatment, PROMs can be used to maintain momentum for tailoring care and services to individual patients, including continued education about what to expect, side effects, and potential impact on well-being (e.g., “What kinds of supports do you have [or are lacking] that might be impacting your well-being score?”). During post-treatment, PROMs can be used to follow up on any further changes to patients’ well-being and additional supports that may be needed (e.g., “What do you need to get back to normal life and recover from your cancer treatment?). Similar research has been reported on the use of PROMs to improve patient-clinician communication and foster therapeutic relationships (Greenhalgh and Meadows, 1999; Yang et al., 2018). Various resources are available to support clinicians who wish to integrate PROMs into their practice, including: a resource guide for healthcare providers’ use of PROMs (healthyqol.com), the ePROs in Clinical Care Guidelines and Tools for Health Systems (becertain.org), and the User’s Guide to Implementing Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice of the International Society for Quality of Life Research (isoqol.org).

Limitations and implications for practice and research

Our study has some limitations that point to areas for future research. The small sample cannot be assumed to reflect all older adults’ experiences nor capture ethnic or cultural differences. Different patients would benefit from questions about supports earlier in the cancer journey and/or prompts about information during the treatment phase. In addition, each phase of the cancer journey (e.g., pre-diagnosis to post-treatment) was based on participants’ memory of past events at a single point in time and may not have captured all of the fluctuations they experienced during their journeys. Future knowledge translation initiatives could examine the potential utility of journey maps for educating the next generation of clinicians to use PROMs for facilitating patient-clinician communication and improving person-centred care. As an educational strategy, PROM-informed journey maps can help foster clinician awareness of how responses to PROMs can be used to not only address gaps in care but also promote well-being. Despite these limitations, our study exemplifies the potential for journey maps to contextualize PROMs data, providing background information and specific insights about patients’ experiences. To that end, this information can provide guidance for clinicians in using PROMs in practice. It draws attention to the need for contextualizing PROMs data to better understand patients’ unique life situations.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the participants for whom this project would not have been possible as well as patient partners who were involved throughout the project.

Appendix. Interview Guide

This interview guide is to be used by the interviewer to facilitate the semi-structured interviews with project participants. The first page and a half is an overview of the interview process .

This project will be creating journey maps based on personas developed from real-life experiences of patients to gain a basic understanding of human behavioural patterns of the older adults’ cancer experience focusing on radiation therapy.

Overview of interview process:

Each semi-structured interview will be approximately 2 hours long.

Interviews will be conducted via zoom (i.e., recorded, transcribed, and stored in a Sync folder shared only with research team members).

Interviewers will briefly provide participants with an overview of the journey mapping concept as it relates to PROMs, their cancer journey and patient reported experience (PRE).

During the interview participants will be asked general questions about their overall health and well-being, and healthcare experience for example “Can you tell me about your pre-diagnosis experience? What that was like for you?” Specifically focusing on participants’ feelings, tasks, and influences during each phase of their cancer journey (see empathy map below).

Participants will be asked to rate their well-being at each phase of their cancer journey using a single item from the BC Cancer Patient-Reported Information & Symptom Measurement (PRISM) questionnaire.

Interview structure:

approx. 10 mins of introductions, includes interview preamble, introduction and demographic questions.

approx. 25 mins for each phase of journey map (Pre-diagnosis, Diagnosis, Treatment, Post-treatment).

approx. 5 mins for interview wrap-up/concluding comments.

Interview Preamble:

Hi, my name is [Name of Interviewer] and I am a research assistant for the journey mapping project.

-

Before we go any further, I would like to confirm that you are eligible for participating in the project:

Were you diagnosed with cancer at or after 65 years of age?

Did you receive radiation therapy as part of your cancer treatment?

Are you a resident of British Columbia?

[Participant must answer ‘Yes’ to all above questions to proceed with the interview]

Example response if participant answers no to any of the above questions:

Thank you for your time and willingness to participate, but unfortunately you are not eligible for the project. I’m sorry if this has caused you any inconveniences. End interview.

This interview is being conducted to understand older adults’ experiences of cancer better with a focus on radiation therapy. We are interested in learning about your overall health and well-being, as well as your healthcare experiences throughout your cancer journey. The interview will be approximately two hours and will be audio-recorded onto my password-protected and encrypted computer and later uploaded to a secure server (the service is located in Canada).

This interview will be used to inform the development of a journey map that will visually display the healthcare experience at each phase of the cancer journey.

Think of this journey map as a visual timeline that displays your healthcare experience over time.

This interview will break-up your cancer journey into four phases: 1. Pre diagnosis, 2. Diagnosis, 3. Treatment, and 4. Post-treatment

For each of these phases, you will be asked about your experience, so we can understand better what you were feeling/thinking, what tasks you were focused on, as well as what influenced you, and your healthcare needs during that time.

Then, reflecting on your experience, I will ask you to rate what your well-being1 was at each phase on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 represents the best feeling of well-being and 10 represents the worst possible feeling of well-being.

This information will help us better understand how these numbers relate to your cancer experiences and how you would rate your well-being on a self-report questionnaire.

Before we begin, I would like to briefly review the consent form with you. I want to confirm that you reviewed and understand the consent form and answer any questions you still may have.

Your participation in this study is voluntary. This means that you have the right to refuse to participate or withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences. During the interview you can choose not to answer questions or stop the interview at any time.

Throughout this interview you will be reflecting on your health, well-being, and healthcare experiences, which may bring up uncomfortable or distressing memories. If you do experience emotional discomfort or distress during the interview, you may take a break whenever necessary, stop the interview and/or withdraw from the study if you wish. If you need further supports, information for mental health resources have been provided on page 2 of the consent form.

Do you have any questions about the interview or the consent form?

Do you consent to participate in the interview?

Is there anything that you would like to share before we start recording the interview?

[Start of interview – Interviewer presses the Zoom audio-record button]

Introduction questions:

Could you tell me a little bit about yourself?

What made you want to be part of this project?

Have you ever completed a survey or questionnaire about your health and well-being as part of your cancer care? If so, how was that experience for you?

Demographic questions:

What is your current age? How old were you when you received your cancer diagnosis?

What type of cancer do/did you have?

When did you receive your radiation therapy (year?)

Note: Bolded questions are the key questions that should be asked during the interview. Prompts and probing questions are suggestions to be used as needed. Please do not read off all the prompts/probing questions, as asking the bolded questions will likely suffice in most interviews.

Phase 1 – Pre-diagnosis (e.g., having symptoms, seeking answers for the symptoms, etc.)

Can you tell me about your pre-diagnosis experience? What was that like for you?

Pre-diagnosis specific prompts:

What was it that caused you worry?

Did you have unusual symptoms or signs that could now be attributed to cancer?

How long did it take before you investigated the signs/symptoms?

Well-being scale:

Based on what you have been telling me about your pre-diagnosis experience, on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being the best feeling of well-being and 10 being the worst possible feeling of well-being, how would you rate your well-being at this time?

How were you feeling and/or what were you thinking about at this time? [Feelings]

Example probing questions:

Were you feeling scared not knowing what was happening?

Were you nervous or worried about getting test results back?

During the pre-diagnosis phase, what tasks were you trying to complete? [Tasks]

Example probing questions:

What types of things were you focused on at this time? (e.g., how were you managing symptoms for example self-medication or lifestyle modifications? Booking appointments with doctors and/or specialists? Did you have easy accesses to healthcare services?)

How were you able to complete these tasks and how did this impact you?

Were there particular people you went to for advice or support? Or places or activities you took part in that influenced how you were feeling or coping? [Influences]

Example probing questions:

Did you change any of your social activities/life? If so, how did this impact your well-being? (e.g., usual activities to relieve stress may no longer be possible, self-conscious of symptoms, overwhelmed with worry, not willing to discuss symptoms).

Were there any changes with who you interacted with? (e.g., pre-cancer was an active member of their golf club and was in involved in the social events and no longer able to do so, could be clubs, activities, or groups of friends, etc.)

Did you seek out any supports or resources? If so, what were they and how did you find them?

General questions:

-

Do you feel that you had adequate access to healthcare services to meet your needs during the pre-diagnosis phase?

Example probing question: Could you tell me more about that?

What, if anything, did you do to address your well-being needs at this time?

Phase 2 – Diagnosis (e.g., getting a diagnosis, making sense of the diagnosis, etc.)

Can you tell me about your diagnosis experience? What was that like for you?

Diagnosis specific prompts: Let the participant tell their experience. Keep it general, if needed ask for more information – “Can you tell me more about that?”

Well-being Scale:

Based on what you have been telling me about your diagnosis experience, on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being the best feeling of well-being and 10 being the worst possible feeling of well-being, how would you rate your well-being at this time?

How were you feeling and/or what you were thinking about at this time? [Feelings]

Example probing questions:

What were your initial feelings/reaction to the diagnosis?

Were you concerned for other people who you cared for, or who cared for you, and did this influence this experience?

During the diagnosis phase, what tasks were you trying to complete? [Tasks]

Example probing questions:

What types of things were you focused on at this time? (e.g., managing symptoms? Next steps? Starting treatment?)

Did you have goals/events that you had to stay focused on? (e.g., vacation, work)

How were you able to complete these tasks and how did this impact you?

Were there particular people you went to for advice or support? Or places or activities you took part in that influenced how you were feeling or coping? [Influences]

Example probing questions:

Did you share your diagnosis with others?

Did you change any of your social activities/life? If so, how did this impact your well-being? (e.g., usual activities to relieve stress may no longer be possible).

Were there any changes with who you interacted with? (e.g., pre-cancer was an active member of their golf club and was involved in the social events and no longer able to do so, could be clubs, activities, or groups of friends, etc.)

Did you seek out any supports or resources? If so, what were they and how did you find them?

General questions:

-

Do you feel that you had adequate access to healthcare services to meet your needs during the diagnosis phase?

Example probing question: Could you tell me more about that?

What, if anything, did you do to address your well-being needs at this time?

Phase 3 – Treatment (e.g., finding a plan, going through treatment focusing on radiation therapy)

Treatment-specific questions – these MUST be asked

At what point in your treatment journey did you have radiation? (i.e., Was radiation therapy your first treatment? What other treatments/therapies did you receive?)

What was the order of your treatments?

Can you tell me about your experiences during radiation therapy? What was that like for you?

Treatment specific prompts:

How long was your radiation therapy?

Were there other therapies or treatments that impacted your radiation therapy?

Well-being Scale:

Based on what you have been telling me about your treatment experience, on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being the best feeling of well-being and 10 being the worst possible feeling of well-being, how would you rate your well-being at this time?

How were you feeling and/or what you were thinking about at this time? [Feelings]

Example probing questions:

Were you worried about the treatment process?

Were you nervous about side effects of therapy or managing your care at home?

Were you feeling frustrated with radiation therapy? Could you tell me more about that?

During the treatment phase, what tasks were you trying to complete? [Tasks]

Example probing questions:

What types of things were you focused on at this time? (i.e., Getting to and from radiation therapy appointments? Managing side effects? Self-care activities, such as mediation, yoga, walking etc.?)

Did you have goals/events that you had to stay focused on? (e.g., vacation, work)

How were you able to complete these tasks and how did this impact you?

Were there particular people you went to for advice or support? Or places or activities you took part in that influenced how you were feeling or coping? [Influences]

Example probing questions:

Did you change any of your social activities/life? If so, how did this impact your well-being? (e.g., changes in routines while receiving radiation therapy?).

Were there any changes to whom you interacted with? (e.g., pre-cancer was an active member of their golf club and was involved in the social events and no longer able to do so, could be clubs, activities, or groups of friends, etc. Less energy to socialize?)

Did you share or talk about your radiation therapy experience or what you were going through with others?

Did you seek out any supports or resources? If so, what were they and how did you find them?

General questions:

-

Do you feel that you had adequate access to healthcare services to meet your needs during the treatment phase?

Example probing question: Could you tell me more about that?

What, if anything, did you do to address your well-being needs at this time?

Phase 4 – Post-treatment (e.g., optimizing and adjusting, life post-treatment, etc.)

Can you tell me about your post-treatment experience? What was/is that like for you?

Post-treatment specific prompts:

Did you experience any challenges or difficulties adjusting to life post-treatment?

How would you describe your lifestyle now after your cancer journey?

Have your daily routines (i.e., hobbies, interests) changed?

Well-being Scale:

Based on what you have been telling me about your post-treatment experience, on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being the best feeling of well-being and 10 being the worst possible feeling of well-being, how would you rate your well-being at this time?

How were you feeling and/or what you were thinking about at this time? [Feelings]

Example probing questions:

Were you nervous/hesitant about adjusting to life post-treatment?

Were you worried about a chance of recurrence?

During the post-treatment phase, what tasks were/are you trying to complete? [Tasks]

Example probing questions:

What types of things were you focused on at this time? (e.g., planning a vacation/traveling, spending time with family/friends, caring for self, caring for others?)

Did you have goals/events that you had to stay focused on? (e.g., vacation, work)

How were you able to complete these tasks and how did this impact you?

Were there particular people you went to for advice or support? Or places or activities you took part in that influenced how you were feeling or coping? [Influences]

Example probing questions:

Did you change any of your social activities/life? If so, how did this impact your well-being? (e.g., return to activities, hobbies, interest prior to cancer diagnosis? Continue with new routines?).

Were there any changes to whom you interacted with? (e.g., reconnect with friends? Expanded social circle? More time/energy to be social?)

Did you continue to use supports or resources or seek out new ones? Could you tell me more about this?

General questions:

-

Do you feel that you had/have adequate access to health care services to meet your needs during the post-treatment phase?

Example probing question: Could you tell me more about that?

What, if anything, did/do you do to address your well-being needs at this time?

Interview wrap-up/concluding comments:

Thank you very much for your time and for sharing your cancer journey with me. Your contribution to this project has been very valuable.

Your unique story will help our team create a visual illustration of your unique experiences during your cancer journey.

In terms of next steps, after our team has had an opportunity to develop the journey map, we would like to contact you again to share the journey map with you to ensure that we’ve adequately captured your unique experience. Would that be okay?

Do you have any questions or concerns at this time?

[End of interview]

Post-interview processes: (for interviewers only)

After the interview the researchers will transcribe and synthesize the interview data (using a transcription service) and begin developing the experience journey map.

After developing a draft of the journey map, the researchers will email participants for feedback to ensure that the journey map aligns with their experiences.

Footnotes

Definition of well-being: The state of being comfortable, healthy, or happy (Oxford English Dictionary). Well-being can also be thought of as the capacity to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face.

Note. Well-being includes physical, mental, emotional, social, and spiritual health.

Funding: This work was supported by the University of Victoria Human & Social Development grant. Sawatzky’s contribution is possible, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval: Ethics was approved by UBC’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board (H22-01714). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained prior to individual interviews.

Consent to Participate: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals who participated in the study.

Authors’ contributions: JY led the conceptualization, analysis, and writing of the manuscript. MM analyzed, interpreted and helped with the writing. GI and AJ analyzed the data and provided input to the manuscript. LW and HH helped interpret the data and reviewed the manuscript. ACW, LL, LKL, and RS provided feedback in the research process and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Bottomley A, Reijneveld JC, Koller M, Flechtner H, Tomaszewski KA, Greimel E, Ganz PA, Ringash J, O’Connor D, Kluetz PG, Tafuri G, Grønvold M, Snyder C, Gotay C, Fallowfield DL, Apostolidis K, Wilson R, Stephens R, Schünemann H, van de Poll-Franse L. Current state of quality of life and patient-reported outcomes research. European Journal of Cancer. 2019;121:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw C, Atkinson S, Doody O. Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qualitative Nursing Research. 2017;4:2333393617742282. doi: 10.1177/2333393617742282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000;88(9):2164–2171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2164::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AM, Hsu S, Felix C, Garst J, Yoshizaki T. Effect of psychosocial distress on outcome for head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiation. The Laryngoscope. 2018;128(3):641–645. doi: 10.1002/lary.26751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies EL, Bulto LN, Walsh A, Pollock D, Langton VM, Laing RE, Graham A, Arnold-Chamney M, Kelly J. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: A scoping review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2023;79(1):83–100. doi: 10.1111/jan.15479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2162125) Social Science Research Network. 1984. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2162125 .

- Dinesh AA, Helena Pagani Soares, Pinto S, Brunckhorst O, Dasgupta P, Ahmed K. Anxiety, depression and urological cancer outcomes: A systematic review. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. International Journal of Cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ijc.33588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi AR, Berta W, Kothari A, Boyko J, Urquhart R. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: A scoping review. Implementation Science. 2016;11(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0399-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons S. Journey Mapping 101. Nielsen Norman Group; 2018. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/journey-mapping-101/ [Google Scholar]

- Graupner C, Kimman ML, Mul S, Slok AHM, Claessens D, Kleijnen J, Dirksen CD, Breukink SO. Patient outcomes, patient experiences and process indicators associated with the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in cancer care: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2021;29(2):573–593. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05695-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray D, Brown S, Macanufo J. Gamestorming: A playbook for innovators, rulebreakers, and changemakers. O’Reilly; 2010. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0596804172/ref=as_li_qf_sp_asin_il_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0596804172&linkCode=as2&tag=gamestormingc-20 . [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh J, Meadows K. The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: A literature review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 1999;5(4):401–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.1999.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A, Monkman H, MacDonald L, Kushniruk A. Contextualizing online laboratory (lab) results and mapping the patient journey. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2022;295:175–178. doi: 10.3233/SHTI220690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J-Y, Moynihan M, Lau F, Wolff AC, Torrejon M-J, Irlbacher G, Hung L, Lambert L, Sawatzky R. Seeing the person before the numbers: Personas for understanding patients’ life stories when using patient-reported outcome measures in practice settings. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2023;172:105016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J-Y, Phillips C, Currie LM. Appreciating the Persona paradox: Lessons from participatory design sessions with HIV+ gay men. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2014;201:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, Petersen C, Holve E, Segal CD, Franklin PD. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2016;35(4):575–582. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox K, Baggetta D, Herout J, Ruark K. Lessons learned from journey mapping in health care. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care. 2019;8(1):105–109. doi: 10.1177/2327857919081024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Decastro G, Schwab RB, Tiamson-Kassab M, Irwin SA. Healthcare use and costs in adult cancer patients with anxiety and depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2020;37(9):908–915. doi: 10.1002/da.23059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy S, O’Raghallaigh P, Woodworth S, Lim YL, Kenny LC, Adam F. An integrated patient journey mapping tool for embedding quality in healthcare service reform. Journal of Decision Systems. 2016;25(sup1):354–368. doi: 10.1080/12460125.2016.1187394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Husson O, Roukema J-A, Poll-Franse LV. Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all-cause mortality: Results from a prospective population-based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2013;7(3):484–492. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedz CL, Knifton L, Robb KA, Katikireddi SV, Smith DJ. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):943. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpot LM, Khokhar BA, DeZutter MA, Loftus CG, Stehr HI, Ramar P, Madson LP, Ebbert JO. Creation of a patient-centered journey map to improve the patient experience: A mixed methods approach. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes. 2019;3(4):466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilleron S, Sarfati D, Janssen-Heijnen M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Soerjomataram I. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: A population-based study. International Journal of Cancer. 2019;144(1):49–58. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford C, Müller F, Faiz N, King MT, White K. Patient-reported outcomes and experiences from the perspective of colorectal cancer survivors: Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2020;4(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00195-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby D, Cascella A, Gardiner K, Do R, Moravan V, Myers J, Chow E. A single set of numerical cutpoints to define moderate and severe symptoms for the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010;39(2):241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibeoni J, Picard C, Orri M, Labey M, Bousquet G, Verneuil L, Revah-Levy A. Patients’ quality of life during active cancer treatment: A qualitative study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):951. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2022;72(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovlund PC, Ravn S, Seibaek L, Thaysen HV, Lomborg K, Nielsen BK. The development of PROmunication: A training-tool for clinicians using patient-reported outcomes to promote patient-centred communication in clinical cancer settings. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2020;4(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-0174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LY, Manhas DS, Howard AF, Olson RA. Patient-reported outcome use in oncology: A systematic review of the impact on patient-clinician communication. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2018;26(1):41–60. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3865-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.