Abstract

Purpose

Multiple myeloma is an incurable hematologic cancer. A palliative approach to care can be used in conjunction with curative therapy to alleviate suffering, but is underutilized in the hemato- oncology population. The purpose of this study was to explore living with multiple myeloma and individuals’ experiences with, and perceptions of a palliative approach in their care.

Methods

Straussian grounded theory was employed. Ten individuals with multiple myeloma participated between October 2021 and May 2022.

Results

A theoretical model depicting the process of living with multiple myeloma was developed. Seven categories emerged from the data, as well as a core category: ‘existing in the liminal space between living with and dying from multiple myeloma’. Results demonstrate that a palliative approach to care was inconsistently utilized.

Conclusions

The model designed from the participant data offers an explanation of the process of living with multiple myeloma and how a palliative approach to care can be utilized to help these individuals.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, palliative approach to care, grounded theory

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable hematological cancer of plasma cells characterized by relapsing and remitting symptoms including cytopenia, elevated blood calcium levels, renal failure, and painful bony lesions (Myeloma Canada, 2017). Despite drastic improvements in treatment modalities and survival, MM remains incurable (Myeloma Canada, 2017). As people are both living longer in the general population, and with MM specifically, comorbidities, increased rounds of therapies used, and frailty associated with advanced age all increase the risk of mortality, as well as patient suffering. Thus, greater attention needs to be paid to the quality of life of this population, particularly as treatments for this disease are rapidly changing.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care (PC) as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness.” It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual (WHO, 2020).

The Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (CHPCA) and Health Canada have developed a framework for a palliative approach to care for Canadians living with life-limiting illness. The principles behind a palliative approach to care are: 1) death is a normal part of life; 2) being considered close to death is an inappropriate trigger to initiate PC; 3) everyone with life-limiting illness can benefit from a palliative approach to care in some way; 4) PC should be provided early and throughout the illness trajectory; 5) PC can be provided by primary healthcare providers throughout a variety of settings; and 6) few people require specialized PC services, as basic PC should be the responsibility of all healthcare providers (CHPCA, 2012; Health Canada, 2018).

A palliative approach to care incorporates symptom assessment and management guided by individual- and family- centred goals instead of problem-centred care. It requires empathetic and compassionate, clear and concise communication, especially regarding the delivery of prognosis-related information to promote disease understanding. And finally, it demands the recognition of non-physical suffering that can be contributed to by cultural, psychosocial, and spiritual influences (Swami & Case, 2018).

The delivery of a palliative approach to care is not confined to PC specialists, but can be delivered by any healthcare provider; it does not require specialized training or certification (Alberta Health Services [AHS], 2021). A palliative approach to care can be delivered in any care setting and may include symptom management, prognosis discussions, goals of care discussions, and advance care planning (AHS, 2021). In contrast, secondary PC is for individuals with more complex needs related to their life-limiting illness, and requires a referral to a specialized PC team (Swami & Case, 2018; AHS, 2021). Tertiary PC , intended for individuals with the most complex needs, is highly specialized PC and is typically delivered by a dedicated PC team (Swami & Case, 2018). This level of care may be required for delivery in specific locations such as specialty inpatient palliative care units (AHS, 2021).

The concept of PC, often incorrectly, has been used synonymously with end-of-life care (Gärtner et al., 2019). This confusion has contributed to the common practice of only employing PC when individuals are at the end of life, and not taking advantage of the full spectrum of value PC can provide (Gärtner et al., 2019). Literature suggests that individuals with hematologic malignancies (HMs), including MM, receive less PC compared to individuals with solid organ cancers (Hui et al., 2015). Research has demonstrated that when integrated early in the disease trajectory as an approach to care, PC has been demonstrated to improve pain and symptom management, mood, overall quality of life, and sometimes even survival rates (El-Jawahri et al., 2016; Temel et al., 2010). If individuals with HMs receive PC, it is almost exclusively at the end of life, with the most common reasons for not integrating a palliative approach being prognostic uncertainty, and the association of PC with death and dying (Howell et al., 2011).

Very few studies address the experience of living with MM from the perspective of the individual diagnosed with the disease and, to our knowledge, none have addressed understanding the experiences and perceptions of receiving a palliative approach in their MM care. Without this understanding, individuals with MM may traverse their disease trajectory without benefit of a palliative approach and, thus, endure unnecessary suffering. The purpose of this study was to explore living with multiple myeloma and individuals’ experiences with and perceptions of a palliative approach to their care. Findings from this research study offer valuable insight regarding how individuals with MM perceive PC, and their experiences with a palliative approach in their care. The findings emphasize suggestions about integrating a palliative approach to care early within the illness trajectory for the MM population.

METHODS

As the intention of this research study was to explore the experiences and perceptions of individuals, the qualitative methodology of Straussian grounded theory was selected (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). In accordance with Straussian grounded theory, convenience and purposive sampling was utilized in this study. These sampling techniques occurred via informational recruitment posters being placed in clinical areas of an outpatient oncology centre in southern Alberta inviting participants to volunteer for the study. Additionally, the posters were placed in clinical areas of an inpatient oncology unit, with potential participants also being purposefully approached by staff to determine their interest in participating in the study. The inclusion criteria included 18 years or older, able to communicate in English proficiently, cognizant enough to recount and report their experiences, had MM for at least two years, and able to provide informed written consent. The exclusion criteria were being admitted for cellular therapy and being too ill to participate. Two years post-diagnosis was selected to avoid coinciding with stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Autologous HSCT is typically done either as early as possible after initial diagnosis, or after the first relapse (O’Brien, 2011), with AHS (2015) myeloma treatment guidelines recommending HSCT within the first year of diagnosis. During HSCT and/or CAR-T therapy, a palliative approach to care or specialist PC involvement may occur because of cellular therapy-related complications, rather than because of the diagnosis itself. This would conflate the concepts of a palliative approach to care for MM with symptom management needs related to cellular therapy, contradicting the purpose of this study. Additionally, individuals receiving CAR-T cell therapy were also ineligible, as this is a novel treatment in Canada and is currently only provided on a regulated trial basis.

Data Collection

After information about the study had been explained further, including the purpose of the study; what would be required to participate; how information would be collected, used, and stored; how anonymity would be ensured; and the right to withdrawal, written informed consent was obtained. Data were collected between October 2021 and May 2022. Semi-structured interviews following an interview guide designed for this study (Appendix) was the primary form of data collection. Interviews averaged approximately 60 minutes. These interviews occurred in participants’ private hospital rooms (n = 6), over the phone (n = 1), or via video teleconferencing (n = 3). Interviews were conducted, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim by the primary researcher (AW) into a Microsoft Word© document. As data collection and analysis took place simultaneously, interview questions evolved. Participants were recruited until all categories were sufficiently developed and new data were no longer contributing to emerging theory (theoretical saturation; Corbin & Strauss , 2015) with a total of 10 participants being interviewed (Table 1). Research ethics board approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Board of Alberta (HREBA.CC-21-0166).

Table 1.

Study Sample Demographics

| Participant | Sex | Age at Diagnosis | Years Living with MM | Number of Stem Cell Transplants | Marital Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Female | 54 | 3 | 1 | Married |

| P2 | Male | 64 | 7 | 2 | Married |

| P3 | Male | 41 | 12 | 2 | Married |

| P4 | Male | 51 | 3 | 1 | Married |

| P5 | Female | 59 | 11 | 1 | Married |

| P6 | Female | 54 | 19 | 1 | Married |

| P7 | Male | 29 | 3 | 1 | Common-Law |

| P8 | Female | 68 | 13 | 0 | Married |

| P9 | Female | 45 | 17 | 1 | Married |

| P10 | Male | 47 | 4 | 1 | Married |

Note. MM = multiple myeloma.

Data Analysis

In Straussian grounded theory, data analysis is achieved through three stages of coding: open, axial, and selective (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). A key feature of grounded theory is that data collection and analysis occur simultaneously (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Thus, analysis of the interviews began upon completion of the first interview and continued in a similar concurrent manner after each subsequent interview. Analysis was completed without the use of any software, by the primary researcher (AW), and reviewed with thesis supervisor (SS) who has extensive, internationally recognized expertise in qualitative research, PC, and oncology.

Open Coding

During open coding, the data were thoroughly examined and divided into smaller fragments whereby core ideas were identified and given a conceptual label (code) to describe it (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). Codes were then grouped together into low-level concepts based on their conceptual similarities (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). This was achieved by posing questions of the data and constantly comparing codes and data (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Higher level categories and subcategories were then formed by grouping concepts together based in their conceptual similarity (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Axial coding

Open and axial coding occurred in an iterative manner, with initial subcategories and categories being refined as subsequent transcripts were analyzed, allowing for theoretical data saturation and sensitivity to occur (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). During this process, codes, subcategories, and categories were compared and reviewed using a coding paradigm, which assisted understanding the causes, contexts, conditions, action, interactions, and consequences between and within subcategories and categories (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). As a result, some subcategories were merged, some formed larger categories, and other subcategories were dismissed based on developing patterns and relationships within the data. This allowed for the development of abstract concepts to emerge and the properties and dimensions of the categories to be refined (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Selective coding

Selective coding followed axial coding, whereby the main categories were integrated into one cohesive theory. All categories were unified around a core category that was representative of the main subject of all of the research by asking questions, such as what was the main idea and to describe what was going on in just a few sentences (Corbin & Strauss, 1990).

RESULTS

Selected Demographics of the Sample

Ten individuals participated in the interviews. The sample was equally divided into males and females, and all were married (n = 9) or living common-law (n = 1). They ranged in age from 29 to 68 and had been living with MM between three and 19 years (Table 1).

Categories

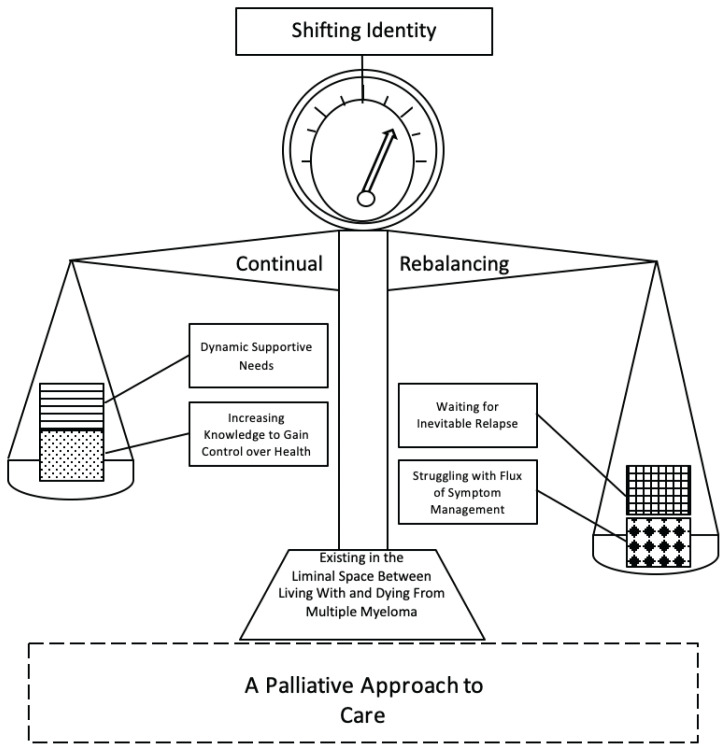

Seven categories (Table 2) emerged from the data with fifteen subcategories. The core category and name of the model (Figure 1) that connected each of the categories together and explained the process of living with MM was existing in the liminal space between living with and dying from MM.

Table 2.

Categories and Subcategories Identified During Analysis

| Category | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Core Category | |

| Existing in the Liminal Space Between Living with and Dying from Multiple Myeloma | |

| 1. Shadow Data: The Perceived Absence of a Palliative Approach to Care | |

| 2. Waiting for Inevitable Relapse: Knowing What the Future Holds | 2A: Living with the Knowledge of Inevitable Relapse 2B: Treatment Failure: Foretelling the Inevitable |

| 3. Shifting One’s Identity: Discovering a New Self While Maintaining the Old Self | 3A: A New and Permanent Label: The Effect of Multiple Myeloma on Identity 3B: New Behaviors: Forced Changes as a Result of Multiple Myeloma 3C: New Limitations: Personal Constraints That Arose a Result of Living with Multiple Myeloma |

| 4. Increasing Knowledge to Gain Control Over Health: Stabilizing the Uncertainty of Living with Multiple Myeloma | 4A: Value in Increasing Knowledge: Empowerment Through Health Education 4B: Multiple Myeloma Requires Self-Advocacy: From Knowledge to Action |

| 5. Struggling with the Flux of Symptom Management | 5A: Ongoing Side Effects: The Price to Pay for Living with Multiple Myeloma 5B: Decreased Quality of Life: The Result of Living with Multiple Myeloma 5C: Unmet Needs: When SufferingGoes Unaddressed |

| 6. Continual Rebalancing: Never Feeling Completely Settled | 6A: New Normal: When Back to Normal is Not an Option 6B: A Constant State of Uncertainty |

| 7. Dynamic Supportive Needs: Multiple Concerns Require Multiple Solutions | 7A: Primary Support Systems: Family and Close Friends Provide the Greatest Support, but Not Without Limits 7B: Support from Healthcare Providers: The Support Friends and Family Cannot Provide 7C: Support Groups: The Support Nobody Else Can Provide |

Figure 1.

Existing in the Liminal Space Between Living With and Dying From Multiple Myeloma

The model takes form as a balance scale (Figure 1). At the top of the scale is a gauge, where the category, shifting identity, is situated. The needle shifts within the gauge when the weight on either side of the balance fluctuates as an individual oscillates through the changes of their MM, which is represented by the weights in the balance plates. The four categories: increasing knowledge to gain control over health, dynamic supportive needs, waiting for inevitable relapse, and struggling with the flux of symptom management are the weights individuals with MM carry with them as they live with their disease. The two categories: waiting for inevitable relapse and struggling with flux of symptom management are the negative weights of what individuals suffer with when living with MM. On the opposite side of the balance are the positive counterweights: increasing knowledge to gain control over health and dynamic supportive needs. These positive counterweights are what support individuals through their suffering. The arms of the balance represent the category of continual rebalancing. As individuals repeatedly oscillate between periods of uncertainty and find their new normal, the balance is also constantly readjusting to the ever-changing weight. The base, represented as trapezoid at the bottom of the balance, signifies the core category: existing in the liminal space between living with and dying from MM. It acts as a foundation to keep the entire structure from toppling over. Finally, the stabilizer is the dotted line rectangle at the bottom of the model, which represents the category a palliative approach to care. The dotted lines indicate that this is a shadow category, as this topic was implicit where individuals would have liked and accepted the support had they understood it and it was offered to them. It acts to provide extra support in order to stabilize the balance and, thus, the individual’s ability to exist in the liminal space. The negative weights can never be eliminated, but they can be managed in a way, using a palliative approach to care where the scale is more balanced and spends less time at extreme fluctuations.

Regardless of where they were within the MM trajectory, participants felt they were constantly in a liminal space between feeling well and that they could live their life free from their illness, yet simultaneously being aware that their MM would never fully be gone.

Category 1: Shadow Data: The Perceived Absence of a Palliative Approach to Care

This category was labeled a shadow category as it emerged not from what participants said, but partly from what participants did not say. Ironically, while exploring the perspectives and experiences of a palliative approach to care from individuals with MM was one of the key objectives of this study, the majority of participants did not correctly understand what PC care was, nor recall having topics related to PC outside of treatment plans broached by any member of their healthcare team or remember having any specialist palliative involvement in their care. Most participants seemed extremely reluctant to talk about PC within the interviews. “We don’t talk about that until it’s time to talk about it, palliative care. I mean, if I was at that point, then I would talk about that stuff. I hope I’m getting that meaning right, close-to-death care” (P3).

Category 2: Waiting for Inevitable Relapse: Knowing What the Future Holds

Relapse was described as something participants were always waiting for, while trying to continue to live as best as possible in the interim. Knowing that relapse could happen to them at any time made it challenging to live in the present as, ironically, participants felt that so much of the present was spent worrying about the future. “Relapse is always in the back of your mind. I mean those thoughts never go away, but I try not to think about it every waking minute” (P9).

Treatment failure was not always equated with relapse, rather, treatment failure was perceived as a foretelling of eventual future relapses and the depletion of treatment options over time. “It was less than a year after my transplant that I had relapsed. Things were not looking very optimistic. But now I’ve had a very good response to the new treatment I’m on, and knock on wood, I’m cautiously optimistic” (P7).

Category 3: Shifting One’s Identity: Discovering a New Self While Maintaining the Old Self

Participants described living with MM as affecting their whole identity, including their career, their role in their relationships, and self-perception. Participants often struggled to view their identity as a cohesive whole, with many participants describing living between these two identities (who they once were and had become) as their illness fluctuated. This category specifically described how individuals navigated the changes they experienced as a result of their MM, balancing who they felt like they once were and who they felt they had become. Participants talked about how their identities became primarily that of a cancer patient. Even during times of remission when participants were feeling well and functioning more in line with their life prior to being diagnosed with MM, they felt that their identity as a cancer patient could never be relinquished. “Cancer penetrates your whole being, body and soul. Cancer is so very much a part of you that without being victimized, you’re different, you don’t belong” (P6).

All participants talked about how MM had caused severe limitations on their lives ranging from physical limitations, limitations to their time, limitations on life plans, limitations on their mental capacity, and limitations to activities due to health risks. These limitations felt repressive as participants struggled to balance living their lives and also live within these new confinements. “It takes away your freedom, and that’s the biggest impact. It’s like being let out of jail, but you have to report to your parole officer every month or every week or whatever it is. Someone, somewhere is going to control what you can and cannot do, and you don’t have much choice anymore” (P8).

Category 4: Increasing Knowledge to Gain Control over Health: Stabilizing the Uncertainty of Living with Multiple Myeloma

In the face of having their entire lives redefined and upturned by MM, participants sought to regain control by becoming increasingly knowledgeable about and focused on their myeloma. Participants described how MM took away a sense of control over their lives, leaving them with loss of their routines and changes in their plans for the future, eroding their wellbeing and optimism about their health, and stealing away the predictability of life. In turn, participants identified knowledge as an important and powerful counter-agent that provided stability in the liminal space of health-related uncertainty. “The more knowledge you have, the more you feel in control. You lack control when you don’t know what’s around the next corner. You don’t want to be blindsided. I want to sit down, I want my doctor to explain to me how does this work, because I want to know, so then I can do more research. You’re part of the education. I’ve always thought the more knowledge you have about something, the better off you are, because then you can make decisions for yourself” (P8).

Category 5: Struggling with the Flux of Symptom Management

The fifth category, ‘struggling with the flux of symptom management’, describes how individuals experienced ongoing side effects, and a decreased quality of life from their life-extending anti-cancer therapies. All individuals experienced ongoing side effects in the short- and long-term, and a decreased quality of life from their life-extending anti-cancer therapies. Some side effects were drug-related, such as nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, and neuropathy and other side effects were disease-related, such as pain, kidney injury, bone fractures, and anemia. Some side effects could not be traced back to a specific origin, but rather seemed to be a combination of a number of factors. “When I had diarrhea, it was just diarrhea. I was not worried. It wasn’t like an organ failing. I didn’t have kidney issues. So, it was strange, for me it was like a phantom inside of myself, I felt okay, but my body didn’t match” (P6).

Participants discussed how MM had, and continued to have, a negative impact on their overall quality of life, even in periods of stable disease. While the multitude of physical symptoms and side effects were experienced in a more immediate and tangible manner, the impact that their disease and treatment had on their quality of life was more cumulative and indirect and, therefore, harder for individuals to conceptualize and express. While participants were thankful to be alive, the majority did not feel satisfied in life as a result of the suffering associated with their diminished quality of life. “I’m taking all these drugs and I’m able to live, but the truth of it is, you feel crappy. I know I’m lucky. I’ve been able to enjoy grandchildren and all kinds of things, but I’m tired. The quality of life is crappy. It’s maybe a six out of 10. It’s not good” (P5).

Category 6: Continual Rebalancing: Never Feeling Completely Settled

The sixth category ‘continually rebalancing’, describes how participants constantly had to adjust their lives through the persistent and frequent transitions of their MM. These adjustments occurred around routines, medications, and emotional states, as nothing felt certain anymore. Participants described continually feeling like they were never in a state of stability, requiring them to constantly readjust to the ever-changing aspects of their disease and, therefore, their life. Upon just starting to reestablish a pattern in their lives, their MM would suddenly wreak havoc through pain crises, relapse, infection, or symptom burden. Everything would have to change again causing them to lose any small trace of stability they had managed to construct. “I was just getting into a routine. I was just getting to know that drug and how it affected me, because you have to learn all of that with each new treatment” (P2). “The aspect of seeing my body changing and not knowing if it’s caused by the cancer, or if it’s just normal” (P6).

Category 7: Dynamic Supportive Needs: Multiple Concerns Require Multiple Solutions

The seventh category, ‘dynamic supportive needs’, described how individuals required varying levels of support for spiritual, physical, emotional, and psychosocial needs, whether coming from friends and family, healthcare providers, or support groups at different times in their MM trajectory. Participants described the need for a broader dynamic support system that ebbed and flowed with the multi-faceted challenges that arose over the course of their illness. All participants talked about how important the support they received from their families and close friends was in their cancer journey, and how they felt they could not survive without this primary support network. However, participants acknowledged that, at times, despite the high level of dedication, their primary support network of family and friends was insufficient to meet their evolving needs. “I had a whole bunch of friends and family stand up and help me out in the beginning. That was huge. They still do, but to a much lesser extent. After my main treatment was done, people disappeared. I mean I get it, everyone’s busy and figuring out their lives, but I still have cancer. And I just wonder if I’m ever going to hear from them again” (P4).

Participants described the support they received from peer support groups as extremely significant in having their ever-changing supportive needs addressed. The ability to connect with someone who was living with MM, in contrast to family, friends, and healthcare professionals who did not have the disease, was felt to be particularly helpful in making participants feel they were not alone. “Sometimes you just want to talk with another myeloma person. My wife doesn’t understand everything I’m going through, but another myeloma patient would. Someone who’s had multiple myeloma can get a grasp of where another multiple myeloma patient is at” (P4).

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to explore the experiences of individuals living with MM and how a palliative approach to care affected the experience of living with incurable cancer. It is clear from the data that the experience of living with MM is underpinned by multimodal suffering. There are numerous descriptions from participants describing emotional, psychological, physical, and spiritual suffering in varying degrees throughout the illness trajectory. However, despite clear instances where a palliative approach could have been beneficial for this population, results from this study revealed that a palliative approach was infrequently used; specifically, physical suffering was usually the only type of suffering addressed, and often not well enough in the view of the participants.

A palliative approach to care is patient- and family-centred, with central tenets involving open communication with the individual and their family members, advance care planning, psychosocial and spiritual support, and pain and symptom management (CHPCA, 2012). The CHPCA (2012) and Health Canada (2018) posit that a palliative approach to care should be the gold standard for all patients with life-limiting illness, and should be provided by all healthcare providers, not just specialists.

Interestingly, during the research interview, when participants of this study were provided with an explanation of a palliative approach to care and how PC could support them, participants generally conveyed support for the idea and thought that such an approach was beneficial. However, when asked if they themselves would be open to receiving an integrated palliative approach to their care to help address their specific unmet physical, emotional, and practical needs while still pursuing any treatment that aligned with their goals, the majority of participants reverted to conflating PC and end-of-life care; they stated they were not at a point in their illness trajectory where they needed PC because they were not at the end of their lives. This paradox occurred despite previously sharing how they were struggling and would be open to an approach to care that specialized in addressing suffering.

This perspective on a PC approach indicates that not only do individuals with MM have unmet needs, but also people may be so conditioned to the term PC as equivalent to end of life, that even when explicitly told it is not exclusive to end of life, participants still regarded the terms as one in the same. Some studies suggest that changing the terminology from PC to a different, less-stigmatized term, such as supportive care, may improve the perception amongst patients and healthcare providers and, thus, utilization of the service overall (Dalal et al., 2011; Fishman et al., 2018). However, despite stigmatization of the term palliative care being one of the greatest barriers to individuals receiving PC, early identification and integration may be the foremost problem with individuals not receiving a palliative approach to care (Murray et al., 2017). This identification is notably more difficult for individuals with long-term, life-limiting conditions, like MM, whose functional decline occurs differently than the typical trajectory of progressive cancers. Until upstream changes to standard practice occur, where a palliative approach to care is simultaneously integrated within oncology care from the point of diagnosis, individuals will continue to experience avoidable suffering.

In the circumstance of a cancer diagnosis, individuals seek remission or cure of their disease, where ideally they would move from the status of an individual with cancer, to being an individual who has no clinical evidence of cancer. However, with incurable illness, individuals still seek remission, while ultimately knowing they will never fully be disease-free. This places them in a liminal space between living with MM and the knowledge that they will eventually die from the disease. Participants frequently discussed this paradox, a paradox that has been noted by Vlossak and Fitch (2008) in their study of the impact of MM on individuals and their families. Vlossak and Fitch reported that individuals with MM did not hope for a cure, but for “a relatively healthy life for as long as possible” (p. 145).

Participants in this current study often discussed perpetually waiting for the next relapse to occur. There was a shared sense of not always being able to fully enjoy their life when their disease was stable because they knew at some point it would be taken away from them. Within this study, it seemed that participants who had experienced more than one relapse, while still living with the concern of relapse looming on the horizon, consciously chose to focus on the present moment and what mattered to them the most. This focus was in comparison to that of participants who had experienced one or no relapse who seemingly had not developed this adaptive technique. The development of this adaptive technique over time reflects findings of Karlsson et al. (2014) who reported that individuals with advanced cancer often moved between existential certainty and uncertainty in relation to their disease process.

Participants of this study talked about how being diagnosed with MM contributed to a loss of identity, whereby individuals no longer recognized their own bodies. This notion of a loss of a former self is consistent with other findings in the MM literature (Kelly & Dowling, 2011; Monterosso et al., 2018). For example, Kelly and Dowling (2011) described how physical changes not only affected the personal identity of an individual with MM, but also affected how these individuals related to others when they could no longer conceal their MM diagnosis from others.

Participants of this study identified the need to become more knowledgeable about their MM diagnosis, gleaning this information from various places, such as support groups, healthcare providers, and other individuals with MM. In a literature review of the needs of individuals with HMs, informational/educational needs ranked the highest out of nine domains of needs (Tsatsou et al., 2021). The need for understanding how to best manage their disease was a common finding among other studies of individuals with MM (Cuffe et al., 2020; Kelly & Dowling, 2011; Vlossak & Fitch, 2008). MM health education was seen as the most desired commodity from healthcare providers, yet it was also often difficult to obtain due to healthcare providers’ time constraints and communication skills, as well as recipients’ readiness to learn.

Most participants reported that they experienced ongoing pain and symptom issues for years and struggled to find relief from them. However, only two participants recalled ever being presented with the option of receiving specialized PC to address their pain and symptom management issues. A number of participants spoke about how they felt they were suffering from the side effects of their treatments including neuropathy, pain, fatigue, and diarrhea. These results echo those of Mols et al. (2012) and Cuffe et al. (2020) who reported that the most prevalent pain and symptom issues for individuals with MM in their studies were fatigue, pain, and dyspnea.

Participants of this study talked about challenges with finding their new normal, getting into a routine, and feeling familiar with their life again. This is similar to the findings of De Wet et al. (2019) and Karlsson et al. (2014) who reported that, by shifting priorities, individuals with cancer in their studies were not only able to feel more control over their lives, but also feel more positive and in control over their situation overall.

Feelings of uncertainty were raised by every study participant. Uncertainty was typically caused by the fear of relapse, waiting for it to happen, and not feeling the future was predictable. This was also underpinned by not knowing if treatment was working, or when it would eventually stop, what changes in lab values represented, or what symptom presentation meant. Consistent with the literature, individuals with MM, regardless of where they were in their illness trajectory, struggled with feelings of uncertainty (Cuffe et al., 2020; De Wet et al., 2019).

Another common concept raised amongst the participants in this study was that despite how much friends and family wanted to be supportive, their support was not always enough. One reason participants felt that family/friend support was limited in utility was due to the prolonged time and required effort these participants needed. This observation aligns with the findings of Nipp et al. (2016), who found family caregivers for individuals with incurable cancer had high rates of anxiety and depression. At times, they experienced higher rates of anxiety than the individual for whom they were providing care.

One of the greatest challenges of living with MM for participants in this study was balancing the amount of life bought from undergoing treatment with the side effects and diminished quality of life that resulted from those treatments (Figure 1). As the purpose of PC is to alleviate suffering in its various forms (WHO, 2020), it is illogical not to take a palliative approach to care while administering life-prolonging therapy, knowing the treatment and disease both involve some form of suffering. The integration of a PC approach with standardized care for individuals with MM is an effective way to work proactively toward addressing avoidable suffering. Participants received attention aimed toward their physical suffering to some degree, but most could not recall conversations related to advance care planning or the acknowledgment of their non-physical suffering. Therefore, the experiences of these individuals were not consistently supported by a palliative approach to care.

IMPLICATIONS

Health Canada (2018) and the CHPCA (2012) suggest that PC can be provided by healthcare providers throughout a variety of settings, and that few people require specialized PC services. They suggest that basic PC should be the responsibility of all healthcare providers. However, in many settings, the belief held by the general public (Fliedner et al., 2021), as well as by healthcare providers, including physicians and nurses (El-Jawahri et al., 2020; Tay et al., 2021), is that PC is equivalent to end-of-life care.

Nurses typically spend the most time with patients and are, therefore, well positioned to provide primary palliative care. However, they could benefit from additional training on a palliative approach to care. Research related to nurses who are not working in a PC setting suggests that while these nurses usually report feeling fairly competent in addressing pain and symptom management issues, they feel considerably less comfortable with integrating other principles of PC. These other issues include communication techniques, and the psychosocial-related aspects of providing PC, including but not limited to engaging in difficult conversations (Hao et al., 2021).

Challenging conversations related to prognosis, advance care planning, and end-of-life care are, therefore, often avoided by general nurses. This avoidance may be due to feeling uncertain about which healthcare provider’s responsibility it is for initiating these conversations, fear of taking away a patient’s hope, or a belief that the timing of these conversations should occur when patients are deteriorating (Hjelmfors et al., 2015). Greater emphasis should be placed on providing palliative care education, including communication and psychosocial support skills, to nurses to empower them to feel confident providing primary PC.

A tool that could be implemented by nurses to promote primary PC delivery, or a palliative approach to care, is the Serious Illness Conversation (SIC) guide. The SIC guide is a document created to support clinicians in having effective and sensitive conversations with individuals facing life-limiting illness about their preferences, goals, and values (AHS, 2018). As open communication is a central tenet to a palliative approach to care, communication regarding an individual’s wishes and quality of life should occur early in the disease trajectory when an individual is well, and often throughout the course of the illness trajectory to ensure that the goals of both the patient and their healthcare providers are aligned. Currently these conversations are generally not happening often enough or early enough in patients’ illness trajectories (Bernacki, 2014). Nurses, in particular, should be prepared to engage in these conversations, as often the conversations occur spontaneously at the bedside during routine care (Beddard-Huber et al., 2021). Undergoing SIC training and feeling prepared to engage in these conversations can assist nurses with providing a palliative approach to care, as these spontaneous conversations can be some of the only advance care planning conversations that occur.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study included participants with a broad range of ages, as well as years living with MM adding to the heterogeneity of the sample and, thereby, improving the quality of the research. However, this study has some limitations to consider. A small sample size was used, which limits generalizability, but is consistent with the grounded theory research methodology of Corbin and Strauss. Additionally, the sample was taken from a single site. The sample was entirely Caucasian, thus limiting the intersectionality of experiences that different racial backgrounds could have provided to enrich the understanding of a palliative approach to care for MM. This is pertinent, as the incidence of MM is twice as high in people of African descent compared to Caucasians (Kanapuru et al., 2022). Further, all participants were in a long-term relationship, thus limiting the understanding of how the needs and experiences differ for people who do not have a spousal caregiver, and how a palliative approach to care may fill their supportive need gaps.

CONCLUSION

MM is an incurable hematological cancer. A palliative approach to care aims to alleviate suffering and can be delivered concurrently with curative intentions with a focus on open communication with individuals and their families, advance care planning, psychosocial support, and pain and symptom management (Gärtner et al., 2019). This study aimed to explore how a palliative approach to care has been utilized to support individuals with MM. However, the findings indicate that a palliative approach to care was inconsistently utilized with this group of individuals despite the observation that individuals could benefit from this approach. MM is complex, relapsing and remitting in nature, and involves higher symptom burden than any other HMs (Kiely et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020). Additionally, the majority of individuals did not fully understand what PC was. Results of this study point to a greater need for support for these individuals. Further research is needed to increase awareness regarding how a palliative approach to care should be used for individuals with MM and to contribute to a culture shift regarding how PC is received in the hemato-oncology care setting.

Appendix. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

What has it been like for you living with multiple myeloma?

What was it like being diagnosed with multiple myeloma?

-

Can you talk to me about what you understand about your illness?

What does it mean to you?

Can you talk to me about what you understand about your prognosis?

-

What has it been like receiving care for your multiple myeloma?

What were some of those things like?

Who or what has been most helpful to you during your cancer journey?

-

Do you feel like you have been suffering (mental/spiritual/physical/emotional)?

What could have been helpful?

If something like symptom management from a dedicated team been available, would that have been appealing to you?

Would there have been any benefit for you to have worked with someone from Spiritual care? Palliative care? Psychosocial care?

Who has addressed the suffering you’re talking about?

-

Who’s been supporting you?

-

Have you seen anyone from Spiritual care? Palliative care? Psychosocial care?

What was that like?

-

-

Have you heard of the term palliative care?

What does that term mean to you?

How did you learn about it?

In looking back on your experience, what kinds of people or services do you think you could have benefitted from seeing more of?

REFERENCES

- Alberta Health Services. Clinical practice guideline: Multiple myeloma. 2015. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/cancer/if-hp-cancer-guide-lyhe003-multi-myeloma.pdf .

- Alberta Health Services. Serious illness care program. 2018. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/acp/if-acp-qi-sicg-clinician-reference-guide.pdf .

- Alberta Health Services. Integrating an early palliative approach into advanced cancer care. 2021. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/cancer/if-hp-cancer-guide-supp023-early-palliative-care-advanced-cancer.pdf .

- Beddard-Huber E, Strachan P, Brown S, Kennedy V, Marles MM, Park S, Roberts D. Supporting interprofessional engagement in serious illness conversations: An adapted resource. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2021;23(1):38–45. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;174(12):1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. The way forward The palliative approach: Improving care for Canadians with life-limiting illness. 2012. http://www.hpcintegration.ca/media/23816/TWF-palliative-approach-report-English-final.pdf .

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. SAGE Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 4th ed. SAGE Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cuffe CH, Quirke MB, McCabe C. Patients’ experiences of living with multiple myeloma. British Journal of Nursing. 2020;29(2):103–110. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, Nguyen L, Chacko R, Li Z, Fadul N, Scott C, Thornton V, Coldman B, Amin Y, Bruera E. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist. 2011;16(1):105–111. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wet R, Lane H, Tandon A, Augustson B, Joske D. ‘It is a journey of discovery’: Living with myeloma. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019;27(7):2435–2442. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, Vandusen H, Traeger L, Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, Telles J, Rhodes A, Spitzer TR, McAfee S, Chen Y-BA, Lee SS, Temel JS. Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2016;316(20):2094–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Jawahri A, Nelson AM, Gray TF, Lee SJ, LeBlanc TW. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(9):944–953. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02386. https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman JM, Greenberg P, Bagga MB, Casarett D, Propert K. Increasing information dissemination in cancer communication: Effects of using “palliative,” “supportive,” or “hospice” care terminology. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2018;21(6):820–824. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliedner MC, Zambrano SC, Eychmueller S. Public perception of palliative care: A survey of the general population. Palliative Care and Social Practice. 2021;15:1–11. doi: 10.1177/26323524211017546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner J, Daun M, Wolf J, Von Bergwelt-Baildon M, Hallek M. Early palliative care: Pro, but please be precise! Oncology Research and Treatment. 2019;42(1–2):11–18. doi: 10.1159/000496184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Zhan L, Huang M, Cui X, Zhou Y, Xu E. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards palliative care and death: A learning intervention. Bio Med Central Palliative Care. 2021;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00738-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Framework on palliative care in Canada. 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/palliative-care/framework-palliative-care-canada.html .

- Hjelmfors L, Van Der Wal MHL, Friedrichsen MJ, Mårtensson J, Strömberg A, Jaarsma T. Patient-nurse communication about prognosis and end-of-life care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015;18(10):865–871. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell DA, Shellens R, Roman E, Garry AC, Patmore R, Howard MR. Haematological malignancy: Are patients appropriately referred for specialist palliative and hospice care? A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Palliative Medicine. 2011;25(6):630–641. doi: 10.1177/0269216310391692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui D, Bansal S, Park M, Reddy A, Cortes J, Fossella F, Bruera E. Differences in attitudes and beliefs toward end-of-life care between hematologic and solid tumor oncology specialists. Annals of Oncology. 2015;26(7):1440–1446. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui D, Kim S-H, Kwon JH, Tanco KC, Zhang T, Kang JH, Rhondali W, Chisholm G, Bruera E. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist. 2012;17(12):1574–1580. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanapuru B, Fernandes LL, Fashoyin-Aje LA, Baines AC, Bhatnagar V, Ershler R, Gwise T, Kluetz P, Pazdur R, Pulte E, Shen YL, Gormley N. Analysis of racial and ethnic disparities in multiple myeloma US FDA drug approval trials. Blood Advances. 2022;6(6):1684–1691. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M, Friberg F, Wallengren C, Öhlén J. Meanings of existential uncertainty and certainty for people diagnosed with cancer and receiving palliative treatment: A life-world phenomenological study. Bio Med Central Palliative Care. 2014;13(28):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-684x-13-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M, Dowling M. Patients’ lived experience of myeloma. Nursing Standard. 2011;25(28):38–44. doi: 10.7748/ns2011.03.25.28.38.c8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely F, Cran A, Finnerty D, O’Brien T. Self-reported quality of life and symptom burden in ambulatory patients with multiple myeloma on disease-modifying treatment. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2017;34(7):671–676. doi: 10.1177/1049909116646337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu J, Chen M, Gu J, Huang B, Zheng D, Li J. Health-related quality of life of patients with multiple myeloma: A real-world study in China. Cancer Medicine. 2020;9(21):7896–7913. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Oerlemans S, Vos AH, Koster A, Verelst S, Sonneveld P, Poll-Franse LV. Health-related quality of life and disease-specific complaints among multiple myeloma patients up to 10 yr after diagnosis: Results from a population-based study using the PROFILES registry. European Journal of Haematology. 2012;89(4):311–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterosso L, Taylor K, Platt V, Lobb E, Musiello T, Bulsara C, Stratton K, Joske D, Krishnasamy M. Living with multiple myeloma. Journal of Patient Experience. 2018;5(1):6–15. doi: 10.1177/2374373517715011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Mitchell G, Moine S, Amblàs-Novellas J, Boyd K. Palliative care from diagnosis to death. British Medical Journal. 2017;356(878):1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myeloma Canada. Multiple myeloma patient handbook. 2017. https://myelomacanada.ca/pixms/uploads/serve/ckeditor/myeloma_canada_patient_handbook_10_2017-2.pdf .

- Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, Gallagher ER, Stagl JM, Park ER, Jackson VA, Pirl WF, Greer JA, Temel JS. Factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in family caregivers of patients with incurable cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2016;27(8):1607–1612. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien S. Advances in LLM. Current developments in the management of leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma. Clinical Advances in Hematology & Oncology. 2011;9(9):684–686. https://www.hematologyandoncology.net/files/2013/09/ho0911_llm1.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Swami M, Case A. Effective palliative care: What is involved? Oncology. 2018;32(4):180–184. https://www.cancernetwork.com/view/effective-palliative-care-what-involved . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay J, Compton S, Phua G, Zhuang Q, Neo S, Lee G, Wijaya L, Chiam M, Woong N, Krishna L. Perceptions of healthcare professionals towards palliative care in internal medicine wards: A cross-sectional survey. Bio Med Central Palliative Care. 2021;20(101):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00787-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsatsou I, Konstantinidis T, Kalemikerakis I, Adamakidou T, Vlachou E, Govina O. Unmet supportive care needs of patients with hematological malignancies: A systematic review. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2021;8(1):5–17. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_41_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlossak D, Fitch MI. Multiple myeloma: The patient’s perspective. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2008;18(3):141–146. doi: 10.5737/1181912x183141145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care .

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, Moore M, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I, Donner A, Lo C. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]