Abstract

Background and aim

Urinary tract infections represent a substantial portion of healthcare-associated infections due to E. coli and Klebsiella. Carbapenems are broad-spectrum antibiotics considered highly effective in treating infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), including carbapenem-producing E. coli and Klebsiella isolates, have become a major concern as they limit treatment options. The study aims to determine the prevalence of carbapenemase-producing E. coli and Klebsiella while also comparing the effectiveness of two detection methods, namely the modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and modified Hodge test (MHT).

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from July 2022 to June 2023 in a tertiary care hospital, in Karad, Satara, India. Three hundred urinary isolates of E. coli (150) and Klebsiella (150) were studied. These isolates were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Two phenotypic methods, the modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and the modified Hodge test (MHT), were used to study carbapenemase production.

Results

Out of three hundred isolates, carbapenemase production was detected in 72 isolates (24%) by the modified Hodge test (MHT) and in 111 isolates (37%) by the modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM). Among the MHT-positive isolates, 46 (63.8%) were identified as Klebsiella and 26 (36.1%) as E. coli. In contrast, of the mCIM-positive isolates, 68 (61.2%) were Klebsiella, and 43 (38.7%) were E. coli. A total of 41 Klebsiella (27.33%) and 25 E. coli (16.66%) isolates tested positive by both methods, highlighting variability in detection rates between the two methods.

Conclusion

This study observed MHT and mCIM to be accurate for the detection of carbapenemase among carbapenem-resistant isolates. However, the mCIM demonstrated greater sensitivity compared to the MHT.

Keywords: antimicrobial susceptibility, carbapenemase, carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (cre), e.coli, healthcare-associated infections, klebsiella, mcim, mht, phenotypic methods, urinary tract infection

Introduction

Multi-drug-resistant (MDR) Enterobacteriaceae infections represent a serious concern to public health because of their high mortality rates. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are among the most important antibiotic-resistant bacteria, making them highly dangerous. The multidrug resistance rates in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are reported to be 30% and 50%, respectively, by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) [1]. Classical symptoms like fever, dysuria, etc. are indicative of urinary tract infections (UTI), as is a urine culture that shows the growth of identified uropathogens above 100 cfu/ml to 105 cfu/ml [2]. E. coli is the most common etiologic agent of UTI [3], with Klebsiella coming in second.

The use of carbapenems in gram-negative bacilli infections that produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) is increasing [4]. These are a class of beta-lactam antibiotics with broad antibacterial activity. They act by preventing the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), thereby inhibiting the synthesis of bacterial cell walls [5]. This disruption of cell wall production leads to bacterial cell lysis and death.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are referred to as resistance to one or more of the carbapenems: meropenem, ertapenem, and imipenem [6]. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae is primarily due to carbapenemase enzyme production. In addition to carbapenemase enzyme production, other resistance mechanisms include the over-expression of efflux pumps by the bacteria, the absence of porins in the bacterial cell membrane, and reduced binding of carbapenems to penicillin-binding proteins [7].

These enzymes are encoded by various genotypes and can be spread among Enterobacteriaceae through transferable genetic material. Notable enzymes involved include Class A carbapenemase, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae. Carbapenemase (KPC) belongs to the serine beta-lactamase family; Class B carbapenemase, known as metallo-beta-lactamase (MBL), includes New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM), Verona integron-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase (VIM), and imipenemase (IMP) and needs metal ions to function; and Class D carbapenemase, or oxacillinases, comprises various subgroups like OXA-48-like enzymes [8]. Understanding this carbapenemase classification is essential for combating antibiotic resistance and guiding treatment strategies against multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) pose a serious threat to global health due to their resistance to carbapenems, which are usually the last resort against multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. CRE infections, which are caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli, have been linked to 50% mortality rates, particularly in vulnerable populations like immunocompromised patients [9]. Low- and middle-income countries have a high rate of CRE due to ineffective infection control protocols, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, and restricted access to advanced diagnostic equipment. The World Health Organization (WHO) noted limited treatment options available for CRE, especially in underdeveloped regions, and its rapid spread as reasons for designating it as a major priority for worldwide research and antibiotic development. The emergence of CRE is further aided by overcrowded medical facilities, inadequate sanitation, and extensive antibiotic abuse [10]. The economic burden of CRE infections is substantial, burdening fragile healthcare systems with longer hospital stays, isolation needs, and costly last-line antibiotics. Addressing CRE necessitates a multifaceted approach, including enhanced antimicrobial stewardship, better infection control, and improved access to affordable diagnostics and treatments in resource-limited settings.

Molecular techniques for detecting carbapenemase genes, while highly specific, are often expensive, demand considerable expertise, and are constrained by the limited range of targeted genes. In the past decade, various phenotype-based assays have emerged as alternatives. These include growth-based techniques like the modified Hodge test (MHT), Etests, and carbapenem inactivation method (CIM), as well as rapid colorimetric assays like manual and commercial versions of the carba NP test. Furthermore, a variety of techniques for the phenotypic detection of carbapenemase activity are also available, including immunochromatographic tests and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) carbapenem hydrolysis assays [11]. Therefore, this study aims to identify the prevalence of carbapenemase-producing E. coli and Klebsiella, in addition to comparing the effectiveness of two methods for detecting carbapenemase production, with the sensitivity of mCIM being higher than that of MHT, making it more reliable in identifying resistant isolates.

Materials and methods

Study design, period, and sample size

This study, using a descriptive, cross-sectional design, took place at the Microbiology Department at Krishna Vishwa Vidyapeeth (Deemed To Be University), Karad, Satara, India, from July 2022 to June 2023 after receiving ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee through protocol number 231/2023-2024, and informed consent was taken from all the patients involved.

Inclusion criteria

Non-repetitive midstream urine samples from UTI patients with urine cultures isolating Klebsiella pneumoniae and E.coli were included.

Exclusion criteria

Isolates from the same patient and specimens will be excluded from the study to avoid duplication of isolates.

Sample collection and processing

Samples from outpatient and inpatient departments were processed using standard microbiology guidelines. Midstream urine was collected aseptically and transported to the laboratory within an hour. The isolates were grown on MacConkey agar and blood agar, identified using Gram stain, and further confirmed with oxidase, catalase, and other biochemical tests. Only Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli were part of this study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

Mueller Hinton agar was subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing using the Kirby Bauer disc diffusion technique following the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations [6]. Isolates with a meropenem inhibition zone diameter of less than 21 mm were positive for carbapenemase screening [12], and further phenotypic confirmatory tests like the modified Hodge test (MHT) and modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) were conducted on these screening-positive isolates to confirm the presence of carbapenemase enzyme.

Modified Hodge test (MHT)

A 0.5 MacFarland's broth of E. coli American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 25922, diluted 1:10, was used to streak a Mueller Hinton agar plate to make a bacterial lawn, which was then allowed to dry for two to five minutes. A 10 µg Meropenem disc was kept in the center of the plate, and a small amount of zinc sulfate powder was sprinkled onto the disc. The meropenem-resistant isolate was streaked in a straight line from the edge of the disc to the outer edge of the plate. The plate was incubated at 35-37℃ for 16-24 hours. After incubation, the appearance of clover-leaf-shaped indentation (Figure 1) at the junction of ATCC E.coli 25922 and the test isolate within the meropenem inhibition zone indicates positive MHT results [12].

Figure 1. Positive modified Hodge test showing clover-leaf indentation .

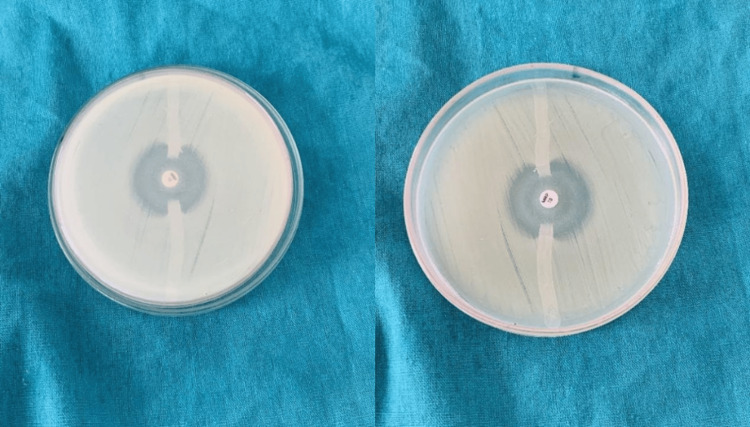

Modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM)

A 2 mL of tryptic soy broth was utilized to mix a 1µL loopful of organisms that were cultured overnight on blood agar. Next, the suspension was mixed thoroughly using a vortex for 10-15 seconds. A 10µg meropenem disc was placed within each tube using sterile forceps, making sure the disc was completely immersed in the suspension and incubated for four hours at 35-37℃. Following the incubation period, Mueller Hinton agar plates were made using an ATCC E. coli 25922 0.5 MacFarland solution. Following that, the meropenem discs were taken out of the tubes and put on Mueller Hinton agar plates, which were then left to incubate at 37℃ for the entire night. A positive result (Figure 2) is indicated by the inhibition zone size of 6-15mm or the existence of pinpoint colonies in a 16-18mm zone diameter, while the diameter of a zone ≥19mm is considered negative [6].

Figure 2. Modified carbapenem inactivation method showing positive result (left meropenem disc) and negative result (right meropenem disc).

The MHT has notable limitations in sensitivity and specificity, with sensitivity ranging from 68% to 97% and specificity from 67% to 100%. This variability can result in false negatives, especially in strains with low-level carbapenemase productions, and false positives due to other resistance mechanisms. The mCIM generally demonstrates higher sensitivity, often reaching 100%, but its performance can be influenced by bacterial load and growth conditions. Although mCIM typically maintains high specificity, it may suffer cross-reactivity with other beta-lactamases. Understanding these limitations is essential for accurate diagnosis and emphasizes the importance of additional testing to ensure reliable results.

Statistical analysis

Data was entered using MS Excel software (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, US), and the chi-square test was subsequently conducted using GraphPad InStat software (Insight Venture Management, LLC, New York, NY, US). A chi-square test was chosen to assess the association between carbapenemase production detection methods (MHT vs. mCIM) and the types of isolates (Klebsiella vs. E. coli). The analyzed data were then presented as percentages and p-values. A result was deemed statistically significant if the probability was less than 0.05.

Results

Out of 1,653 clean-catch midstream urine samples from UTI patients that were collected, 150 were Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae each. E. coli isolates were most common in the 41-60 year old age group (35%); on the other hand, Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates are common in the 41-60 year old age group (40%), as shown in Table 1. This data indicates a higher prevalence of E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in the 41-60 age group, highlighting a significant demographic for urinary tract infections.

Table 1. Age-wise distribution.

n: number; %: percentage

| Age group (in years) | E. coli, n(%) | Klebsiella pneumoniae, n(%) |

| 0-20 | 3 (2) | 4 (3) |

| 21-40 | 38 (25) | 33 (22) |

| 41-60 | 52 (35) | 60 (40) |

| 61-80 | 50 (33) | 52 (34) |

| >80 | 7(5) | 1 (1) |

| Total | 150 (100) | 150 (100) |

E. coli had nearly equal gender distribution (49% male, 51% female), while Klebsiella pneumoniae had a higher prevalence in males (59%) as depicted by Table 2. E. coli isolates show a nearly equal gender distribution, whereas Klebsiella pneumoniae is more prevalent in males, suggesting potential gender-related susceptibility or exposure factors.

Table 2. Gender-wise distribution.

n: number; %: percentage

| Gender | E. coli , n(%) | Klebsiella pneumoniae, n(%) |

| Male | 73 (49) | 88 (59) |

| Female | 77 (51) | 62 (41) |

| Total | 150 (100) | 150 (100) |

It was observed that the majority of the E. coli isolates were from the inpatient department (80%), while the rest were from the outpatient department (20%). Most of the isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae were from the inpatient department (93%), while the rest were from the outpatient department (7%), as seen in Table 3.

Table 3. Distribution of isolates among inpatient and outpatient departments.

n: Number; %: percentage

| Organism | Inpatient department, n(%) | Outpatient department, n(%) |

| E. coli | 120 (80) | 30 (20) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 140 (93) | 10 (7) |

The pattern of antibiotic susceptibility revealed that E. coli had the highest resistance to ceftazidime (97%) and norfloxacin (97%), and was most sensitive to tigecycline (97%) and fosfomycin (96%). Klebsiella pneumoniae showed maximum resistance to ceftazidime (89%) and cefuroxime (89%) and highest sensitivity to tigecycline (86%) and fosfomycin (61%), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Antibiotic susceptibility profile of E.coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Chi-square: 1519.7, p-value <0.001, significantly associated.

n: number; %: percentage

| Antibiotics | E. coli | Klebsiella pneumoniae | ||

| Sensitive, n(%) | Resistant, n(%) | Sensitive, n(%) | Resistant, n(%) | |

| Amikacin | 127 (85) | 23 (15) | 73 (49) | 77 (51) |

| Cefepime | 25 (17) | 125 (83) | 29 (19) | 121 (81) |

| Cefoxitin | 44 (29) | 106 (71) | 19 (13) | 131 (87) |

| Ceftazidime | 4 (3) | 146 (97) | 16 (11) | 134 (89) |

| Ceftriaxone | 16 (11) | 134 (89) | 18 (12) | 132 (88) |

| Cefuroxime | 14 (9) | 136 (91) | 17 (11) | 133 (89) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 7 (5) | 143 (95) | 23 (15) | 127 (85) |

| Cotrimoxazole | 63 (42) | 87 (58) | 58 (39) | 92 (61) |

| Ertapenem | 93 (62) | 57 (38) | 51 (34) | 99 (66) |

| Fosfomycin | 144 (96) | 6 (4) | 92 (61) | 58 (39) |

| Gentamicin | 80 (53) | 70 (47) | 55 (37) | 95 (63) |

| Imipenem | 102 (68) | 48 (32) | 52 (35) | 98 (65) |

| Meropenem | 104 (69) | 46 (31) | 64 (43) | 86 (57) |

| Nalidixic acid | 65 (43) | 85 (57) | 19 (13) | 131 (87) |

| Nitrofurantoin | 57 (38) | 93 (62) | 54 (36) | 96 (64) |

| Norfloxacin | 5 (3) | 145 (97) | 28 (19) | 122 (81) |

| Tigecycline | 146 (97) | 4 (3) | 129 (86) | 21 (14) |

Table 5 summarizes the results of the modified Hodge test for E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Out of the 150 isolates of E. coli, 26 showed a positive result, while 124 were negative. For Klebsiella pneumoniae, 46 isolates yielded positive results and 104 were negative.

Table 5. Results of the modified Hodge test.

Chi-square: 7.310, p-value= 0.0069, significantly associated.

n: number

| Organism | Positive (n) | Negative (n) |

| E. coli | 26 | 124 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 46 | 104 |

Table 6 presents the results of the modified carbapenem inactivation method for E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. For E. coli, 43 isolates were positive, while 107 isolates were negative. In the case of Klebsiella pneumoniae, 68 isolates showed positive results, and 82 were negative.

Table 6. Results of modified carbapenem inactivation method.

Chi-square: 8.938, p-value= 0.0028, significantly associated.

n: number

| Organism | Positive (n) | Negative (n) |

| E. coli | 43 | 107 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 68 | 82 |

In the current study, 25 (17%) E. coli and 41 (27%) Klebsiella pneumoniae tested positive for both MHT and mCIM (Table 7). The results from both MHT and MCIM indicate a substantial proportion of isolates testing positive for carbapenemase production, emphasizing the importance of accurate resistance detection.

Table 7. Comparative study of MHT and mCIM for detection of carbapenemase.

MHT: modified Hodge test; mCIM: modified carbapenem inactivation method; n: number; %: percentage

| Organism | MHT POSITIVE n(%) | mCIM POSITIVE n(%) | MHT + mCIM POSITIVE n(%) |

| E. coli | 46 (31) | 68 (45) | 25 (17) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 26 (17) | 43 (29) | 41 (27) |

These outcomes provide insightful information about the carbapenem resistance mechanisms between Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli, with a majority exhibiting positive reactions in mCIM and a significant proportion also showing positivity in MHT, suggesting the presence of diverse resistance mechanisms in this particular group of isolates. It also emphasizes the significance of utilizing a combination of diagnostic approaches to thoroughly evaluate carbapenem resistance in urinary isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli.

Discussion

Gram-negative bacilli cause infections that have emerged as significant challenges for healthcare institutions due to the limited antibiotic options and the associated high mortality rates [13]. As a result, carbapenem resistance has become a critical focal point in the ongoing battle against healthcare-associated infections, demanding increased attention to safeguard patient health and the burden of such infections on healthcare facilities. In a study by Satyajeet K. Pawar et al. [14], 82% of CRE were Klebsiella pneumoniae (63%) and E. coli (19%), whereas the current study found 44% CRE, with Klebsiella pneumoniae accounting for 29% and E. coli for 15%.

In the present study, 132 carbapenem-resistant isolates were identified, with 24% positive for MHT and 37% positive for mCIM. This highlights a moderate prevalence of carbapenemase production among isolates tested. In comparison, AP Khare et al. [15] reported 150 carbapenem-resistant isolates, with higher MHT positivity rates of 42% and a similar mCIM positive rate of 42.66%. This suggests a slightly more widespread carbapenemase activity in their study population.

Abed Zahedi et al. [4] reported 122 resistant isolates, with 57.38% positive for MHT and 71.31% on mCIM, reflecting a substantial presence of carbapenemase producers. Amjad et al. [16] identified 200 carbapenem-resistant isolates with a 69% MHT positive rate, which is comparatively high. Lastly, Jayalakshmi et al. [12] reported 152 resistant isolates, with 32.89% positive on MHT.

This study's findings of carbapenem resistance in both Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli are concerning, as carbapenems are crucial antibiotics for treating serious infections. The significant finding of our study, where 24% of the samples tested positive for MHT and 37% positive for mCIM, underscores the concern of high resistance rates and treatment challenges leading to treatment failure. These results also signify the necessity of robust antibiotic stewardship programs within healthcare settings.

Carbapenem resistance shows significant regional variations worldwide. In South Asia, particularly India and Pakistan, rates of CRE exceed 50%, largely due to New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM-1) [17]. In a study done in Seoul, Korea, it was observed that Klebsiella pneumoniae was the predominant species (56.5% of isolates), followed by Escherichia coli (17.0%) as CRE [18]. This aligns with the studies conducted in Bahrain, Taiwan, and the US [19-21], where K. pneumoniae was also the most prevalent species, reaching up to 91% in some cases. Given its frequent identification as the leading species among CRE, K. pneumoniae is referred to as carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae and is expected to play a significant role in the spread of carbapenem resistance.

Our study demonstrated that the mCIM method has higher sensitivity compared to the MHT. Saliya Al Musawi’s study revealed the mCIM method demonstrates higher sensitivity compared to MHT for detecting OXA-48 and NDM-type carbapenemases [22]. The mCIM method is well suited for resource-limited microbiological laboratories due to its low cost and simplicity. Additionally, the interpretation of mCIM results is more straightforward and less subjective compared to MHT [23].

Conclusions

The high prevalence of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella and E. coli strains, particularly those resistant due to carbapenemase production, poses a significant challenge for treatment and patient outcomes. Accurate detection of carbapenem resistance is crucial, and this study discovered that both the mCIM and MHT are effective diagnostic tools. Importantly, the sensitivity of mCIM was higher than MHT, making it more reliable in identifying resistant isolates and reducing false negatives.

The research additionally highlights the fact that both mCIM and MHT are easy to implement in routine laboratory testing without the need for specialized equipment. This accessibility permits improved integration with standard procedures, aiding clinicians in making informed decisions about antibiotic therapy. In conclusion, the study highlights the prevalence of carbapenemase and the importance of their detection methods in managing drug-resistant infections and improving patient care.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the teaching faculty, technical staff, postgraduate students, and attendants of the Department of Microbiology for their cooperation and support throughout the study. We also appreciate the Management of Krishna Viswa Vidyapeeth (Deemed To Be University), Karad, Maharashtra, India, for allowing us to conduct this work and for their continued support.

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Institutional Ethics Committee of Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences, Krishna Vishwa Vidyapeeth (Deemed To Be University), Karad issued approval 231/2023-2024. The authors affirm that this study adhered to ethical standards and received approval from Institutional Ethics Committee of Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences, Krishna Vishwa Vidyapeeth (Deemed To Be University), Karad, under protocol number 231/2023-2024.

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Kumuda Arumugam, Geeta S. Karande, Satish R. Patil

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Kumuda Arumugam, Geeta S. Karande

Drafting of the manuscript: Kumuda Arumugam, Geeta S. Karande

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kumuda Arumugam, Geeta S. Karande, Satish R. Patil

Supervision: Geeta S. Karande, Satish R. Patil

References

- 1.In vitro activity of ceftazidime-avibactam and its comparators against carbapenem resistant enterobacterales collected across India: results from ATLAS surveillance 2018 to 2019. Bakthavatchalam YD, Routray A, Mane A, et al. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022;103:115652. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2022.115652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The clinical significance of high antimicrobial resistance in community-acquired urinary tract infections. Zavala-Cerna MG, Segura-Cobos M, Gonzalez R, Zavala-Trujillo IG, Navarro-Perez SF, Rueda-Cruz JA, Satoscoy-Tovar FA. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2020;2020:2967260. doi: 10.1155/2020/2967260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Determination of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and AMPC production in uropathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli and susceptibility to fosfomycin. Gupta V, Rani H, Singla N, Kaistha N, Chander J. J Lab Physicians. 2013;5:90–93. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.119849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modified CIM test as a useful tool to detect carbapenemase activity among extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Acinetobacter baumannii. Zahedi Bialvaei A, Dolatyar Dehkharghani A, Asgari F, Shamloo F, Eslami P, Rahbar M. Annals of Microbiology. 2021;71:23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: epidemiological features, resistance mechanisms, detection and therapy. Ma J, Song X, Li M, et al. Microbiol Res. 2023;266:127249. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2022.127249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.J Clin Microbiol. Vol. 24. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2020. CLSI: M100: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; pp. 1864–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phenotypic method for differentiation of carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae: study from north India. Datta P, Gupta V, Garg S, Chander J. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:357–360. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.101744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emerging carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infection, its epidemiology and novel treatment options: a review. Tilahun M, Kassa Y, Gedefie A, Ashagire M. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:4363–4374. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S337611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the impact and evolution of a global menace. Logan LK, Weinstein RA. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:0–36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:1057–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comparison of 11 phenotypic assays for accurate detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Tamma PD, Opene BN, Gluck A, Chambers KK, Carroll KC, Simner PJ. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:1046–1055. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02338-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Performance of modified Hodge test for detection of carbapenemase producing clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Jayalakshmi S, Pandurangan S. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2016;5:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Global threat of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Jean SS, Harnod D, Hsueh PR. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:823684. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.823684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: prevalence and bacteriological profile in a tertiary teaching hospital from rural western India. Pawar SK, Mohite ST, Shinde RV, Patil SR, Karande GS. Indian Journal of Microbiology Research. 2018;5:342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comparison of three phenotypic methods of carbapenemase enzyme detection to identify carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Khare AP, Gopinathan A, Leela KV, Naik S. Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology. 2022;16:2679–2687. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modified Hodge test: a simple and effective test for detection of carbapenemase production. Amjad A, Mirza Ia, Abbasi S, Farwa U, Malik N, Zia F. https://ijm.tums.ac.ir/index.php/ijm/article/view/112. Iranian Journal of Microbiology. 2011;3:189–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: epidemiology and prevention. Gupta N, Limbago BM, Patel JB, Kallen AJ. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:60–67. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Seoul, Korea. Park S H, Kim J S, Kim H S, et al. Journal of Bacteriology and Virology. 2020;50:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a tertiary care center in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Saeed NK, Alkhawaja S, Azam NF, Alaradi K, Al-Biltagi M. J Lab Physicians. 2019;11:111–117. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_101_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections: Taiwan aspects. Jean SS, Lee NY, Tang HJ, Lu MC, Ko WC, Hsueh PR. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2888. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rising rates of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in community hospitals: a mixed-methods review of epidemiology and microbiology practices in a network of community hospitals in the southeastern United States. Thaden JT, Lewis SS, Hazen KC, et al. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:978–983. doi: 10.1086/677157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.mCIM test as a reliable assay for the detection of CRE in the Gulf region. Al Musawi S, Ur Rahman J, Aljaroodi SA, et al. J Med Microbiol. 2021;70:1381. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Comparison of four low-cost carbapenemase detection tests and a proposal of an algorithm for early detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in resource-limited settings. Kumudunie WG, Wijesooriya LI, Wijayasinghe YS. PLoS One. 2021;16:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]