Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to review and describe isolated sixth cranial nerve or abducens nerve palsy that may present with subtle ophthalmoplegia in patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA).

Materials and methods

In this systematic review following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Extension for Scoping Reviews, MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched for all peer-reviewed articles using the keywords “cranial nerve six,” “abducens nerve,” and “giant cell arteritis” from their inception to December 22, 2022.

Results

Twenty-five articles, including seven observational studies and 18 cases, were included. While the incidence and prevalence of sixth nerve palsy in GCA were variable, up to 48% of diplopia in GCA were attributed to the sixth cranial nerve palsy, according to the observational studies included. While 88.2% had a resolution of symptoms with 40-50 mg/day of prednisone-equivalent corticosteroids, it took a median of 24.5 days until the resolution of symptoms from the initiation of treatment.

Conclusion

This review summarizes the current understanding of the characteristics of sixth nerve palsy in GCA. While most patients may have reversible clinical courses, a few can suffer from persistent ophthalmoplegia, which is a potentially missed yet crucial clinical finding in GCA. Increased awareness of the sixth nerve palsy in GCA is crucial.

Keywords: Abducens nerve, giant cell arteritis, six nerve palsy, systematic review.

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a systemic inflammatory vasculitis typically affecting the aorta and its main branches, commonly encountered in adults over 50 years old.[1] GCA presents with constitutional symptoms and symptoms related to the affected artery, such as jaw claudication or headache. One of the most feared ophthalmologic complications in GCA is vision loss due to arterial inflammation of the posterior ciliary arteries.[2-4]

Although rare, GCA also causes oculomotor abnormality presenting as diplopia, with a previous report of about 3-8% among GCA and about 8-20% among GCA with ophthalmic symptoms.[3,5] GCA could affect oculomotor nerves, including the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves. Generally, the sixth cranial nerve palsy was reported to be the most common nerve paralysis among ocular motor nerves in isolation.[6-8] However, some sixth cranial nerve palsy cases in GCA were likely underdiagnosed given the lack of understanding about illness scripts and initial presentations, rendering a challenge for correct diagnosis.

At this point, it is unclear if the sixth cranial nerve palsy in GCA patients could be a temporary, reversible, or irreversible finding. Given the potential need for prompt diagnosis and treatment to address the overlooked symptom, clinical pictures of the sixth cranial nerve palsy in GCA need to be well-defined. In this study, a systematic review of existing literature related to the sixth cranial nerve palsy in GCA was performed to clarify detailed clinical presentations and characteristics.

Patients and Methods

This systematic scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews.[9,10] MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched for all peer-reviewed articles from inception to December 22, 2022. No filters for study design and language were used. A manual screening for additional pertinent articles was done using the reference lists of all articles that met the eligibility criteria. The search strategy involved relevant keywords, including “cranial nerve six,” “abducens nerve,” and “giant cell arteritis.” The search was conducted by two authors independently. See Appendix 1 for detailed search terms. The criteria for the inclusion of articles were as follows: (i) peer-reviewed articles describing cases of GCA with cranial six nerve palsy; (ii) randomized controlled trials, case-control studies, cohort studies (prospective or retrospective), cross-sectional studies, case series, case reports, and conference abstracts; (iii) adult patients. The exclusion criteria were qualitative studies, review articles, and commentaries.

Study selection

Articles selected for full-text assessment were assessed independently by two authors using EndNote 20 reference management software (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, United States). Articles considered eligible were then evaluated in full length with the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction and definition

A standardized data collection form that followed the PRISMA and Cochrane Collaboration guidelines for systematic reviews was used to obtain the following information from each study: title, name of authors, year of publication, country of origin, study characteristics, target outcome, aims, study and comparative groups, key findings, and limitations. Data from existing case reports and case series were also analyzed to identify the clinical characteristics of the included cases.

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as median with interquartile ranges (IQR) of the data if applicable. All analyses were performed using JMP 15.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

Results

Search results and study selection

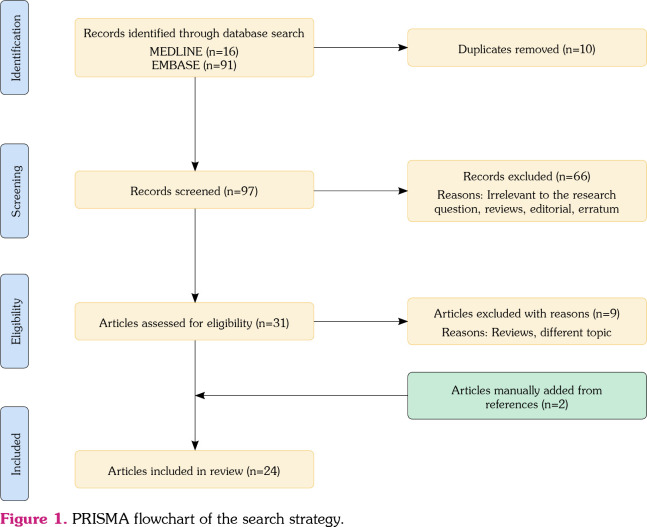

Figure 1 demonstrates a PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion and exclusion processes of the studies involved. The initial MEDLINE and EMBASE databases review yielded 16 and 91 articles, respectively. Ten duplicate studies were removed. Ninety-seven articles were screened based on their relevance and article type. Sixtysix articles that were either review articles, editorials, or studies that focused on matters irrelevant to the research question were excluded from the study. Thirty-one articles were then evaluated for full-text review for study inclusion per our eligibility criteria. Review articles or papers describing different topics were excluded. Two articles were added to the reference list search. As a result, 24 articles, including six observational studies and 18 cases from case reports and series, were included in the review. See Appendix 2 for the list of the included case reports and series.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of the search strategy.

Description of included studies

Table 1 describes the main characteristics of the seven observational studies from the scoping review. Except for studies by Haering et al. [3] and Issa et al., [5] they were investigational studies without comparative groups.[11-14]

Table 1. Main characteristics of the included observational studies in the scoping reviews.

| Author, year, country | Study type | Aim | Outcome | Population | Comparative groups | Key findings | Limitations |

| Chazal et al.[14]2022, France | Observational | To better characterize diplopia in newly diagnosed GCA patients | Characteristics and prognosis of binocular diplopia | GCA (n=lll) | None | 80/111 (72%) had visual signs, including 30/111 (27%) with binocular diplopia Diplopia was attributed to cranial nerve palsy in 21/24 (88%, especially third (50%) and sixth cranial nerve (48%) palsies |

Mainly focused on diplopia rather than six nerve palsy No outcome data about six nerve palsy Conference abstract |

| Coronel Tarancôn et al.[12]2018, Spain | Observational | To check the frequency of stroke as presentation symptom of GCA and other findings related with it | Clinical and laboratory findings | GCA (n=123) | None | 37/123 (30%) suffered from ischemic vents of internal carotid artery, 12/123 (10%) presented with neurological symptoms different from A ION. Out of 12 patients with non-ocular ischemic symptoms of central nervous system, 2/12 (17%) of sixth nerve paresis |

Data was mainly focused on stroke symptoms Conference abstract |

| Issa et al.[5]2022, Canada | Observational | To compare characteristics of patients with and without systemic GCA with ocular manifestations | Clinical and laboratory findings, and ocular manifestations | Temporal artery biopsy positive GCA without systemic symptoms (n=6) | Temporal artery biopsy positive GCA with systemic symptoms (n=36) | In GCA without systemic symptoms, 5/6 (83%) presented with A ION, 1/6 (17%) with isolated cranial nerve six palsy In GCA with systemic symptoms, 17/36 (47%) presented with A ION, 1/36 (3%) with iso lated cranial nerve six palsy |

Lacking detailed clinical data for six nerve palsy |

| Laskou et al.[13]2018, USA | Observational | To obtain information regarding the burden of vision loss in GCA | Clinical findings and ocular manifestations | GCA (n=388) | None | Visual symptoms were present in 135/388 (35%) 8 had oculomotor nerve palsies (1 bilateral 3rd, 1 bilateral 6th, and 6 unilateral 3rd or 6thnerve palsy) |

Lacking detailed clinical data for six nerve palsy |

| Nayak et al.[11] 2016 |

Observational | To evaluate epidemiologic characteristics of giant cell arteritis | Clinical findings | GCA (n=5337) | None | The most common noted cranial nerve palsy was of the sixth nerve (0.5%) | Date was extracted national database Lacking detailed clinical data for six nerve palsy |

| Haering et al.[3] 2014, Switzerland | Observational | To compare patients with and without diplopia in CGA | Clinical and laboratory findings | GCA with diplopia (n=9) | GCA without diplopia (n=28) | Prospectively analyzed AION: Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy; GCA: Fiant cell arteritis. Abduction deficit was confirmed 5/9 patients by ophthalmologic evaluation. 1/9 patient history was consistent with abduction deficit Visual impairment and loss were diagnosed 4/9 (44%) in patients with diplopia, and in 7/28 (25%) in diplopia |

Single center study |

| AION: Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy; GCA: Fiant cell arteritis. | |||||||

Chazal et al.[14] performed an observational study including 111 GCA patients to characterize diplopia and ocular symptoms in the population. Interestingly, among those who had diplopia, 48% were attributed to the sixth cranial nerve palsy. The results were limited as it was a conference abstract. Similarly, Coronel Tarancón et al.[12] focused on the neurological symptoms of 123 GCA patients but noted that only two out of 123 had sixth cranial nerve palsy. Issa et al., [5] Laskou et al.,[13] Nayak et al.,[11] and Haering et al. [3] also reported a low incidence of the sixth cranial nerve palsy in GCA. Haering et al. [3] T included those with GCA with or without diplopia. While they only included nine patients with diplopia, 55.6% with GCA and diplopia had abduction deficit by ophthalmologic evaluation, which was more common than vision loss (44.4%).

Table 2 presents the baseline demographics, diagnostic findings, and chief clinical features from the individual cases (n=18).[4,15-31] The median age of the included cases was 75.0 (interquartile range [IQR], 70.5-79.3) years. Male patients constituted 55.6% of the sample. Headache and diplopia were the most common symptoms, followed by jaw claudication, vision loss, and fever. Of the patients, 33.3% had bilateral sixth cranial nerve palsies. While the duration of the sixth cranial nerve palsy before admission and after the onset of initial symptoms was variable, initial symptoms preceded the sixth cranial nerve palsy for a median of 16.0 (IQR, 8.8-77.0) days. A biopsy-proven diagnosis was present in 88.9%. Most patients received more than 40-50 mg/day of prednisone-equivalent corticosteroids, and 88.2% had a resolution of sixth cranial nerve palsy. Interestingly, it took a median of 24.5 (IQR, 6.0-56.0) days until the resolution of symptoms from the initiation of treatment.

Table 2. Baseline demographics, laboratory findings, and chief features of the included cases.

| n | % | Median | IQR | |

| Age (year) | 75.0 | 70.5-79.3 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 10/18 | 55.6 | ||

| Female | 8/18 | 44.4 | ||

| Symptoms | ||||

| Headache | 12/18 | 72.2 | ||

| Diplopia | 14/16 | 87.5 | ||

| Vision change or loss | 6/18 | 33.3 | ||

| Fever | 4/18 | 22.2 | ||

| Jaw claudication | 8/18 | 44.4 | ||

| Abducens nerve laterality | ||||

| Unilateral | 12/18 | 66.7 | ||

| Bilateral | 6/18 | 33.3 | ||

| Duration of CN6 palsy before admission (days) | 16/18 | 88.9 | 5.5 | 1.0-19.3 |

| Duration until onset of CN6 palsy after onset of initial symptoms (days) | 16/18 | 88.9 | 16.0 | 8.8-77.0 |

| Concurrent PMR | 0/18 | 0 | ||

| Concurrent diabetes | 2/18 | 11.1 | ||

| Known autoimmune disease | 0/16 | 0 | ||

| Biopsy-proven diagnosis | 17/18 | 94.4 | ||

| Treatment | ||||

| Pulse-dose corticosteroid | 4/15 | 26.7 | ||

| Prednisone-equivalent 60-80 mg/day | 4/15 | 26.7 | ||

| Prednisone-equivalent 40-50 mg/day | 5/15 | 33.3 | ||

| Dose unspecified corticosteroid | 2/15 | 13.3 | ||

| Resolution of CN6 palsy after treatment | 15/17 | 88.2 | ||

| Duration from initiation of treatment until resolution of CN6 palsy (days) | 14/18 | 77.8 | 24.5 | 6.00-56.0 |

| Laboratory findings* | ||||

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 14/18 | 77.8 | 59.5 | 43.8-84.5 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 11/18 | 61.1 | 19.0 | 12.0-58.0 |

| IQR: Interquartile range; CN: Cranial nerve; PMR: Polymyalgia rheumatica; * Prevalence here is defined as the number of cases reported the variab le divided by the number of the total cases. | ||||

Discussion

In the present study, we thoroughly reviewed the literature and evidence regarding the sixth cranial nerve palsy in GCA. This is the first study to clarify detailed clinical presentations and time course of the critical and potentially reversible symptoms. In particular, the result that patients usually require more than three weeks until resolution of symptoms from initiation of treatment may give internists, neurologists, and rheumatologists an idea of discharge planning and how to educate patients regarding conditions and follow-up.

Currently, evidence regarding the incidence and prevalence of sixth nerve palsy has been variable. However, given the results of the reviews, it may be more common than expected in those with diplopia, which mandates clinicians’ close attention to ophthalmologic exams on subtle changes and ophthalmoplegia in addition to screening for vision loss. At the same time, differential diagnosis of the sixth nerve palsy is broad, including ischemic stroke, intracranial tumors, and demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis.[1,3,32-39] Extensive workup to exclude the above is crucial, as the sixth cranial nerve palsy due to GCA is a diagnosis of exclusion. Additionally, raising awareness of GCA as a differential diagnosis in patients with the sixth cranial nerve palsy symptoms among clinicians is crucial.

Regarding clinical characteristics, our results showed that patients with sixth nerve palsy in GCA were more likely to be male (55.4%). None of them had a concurrent diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica, and there was a very high biopsyproven diagnosis rate of 94.4%. Additionally, one-third of the patients had bilateral sixth nerve palsy. This information might be useful for physicians who need to be more observant of sixth nerve palsy symptoms.

Regarding the response to the treatment, the present results were reassuring as close to 90% showed recovery of the sixth nerve palsy with treatment based on corticosteroids. However, it is essential to note that recovery took approximately three to four weeks, or even up to two months in some cases. While further accumulation of prospective data may be needed, patients with GCA solely with abducens nerve palsy without other signs of clinical flare could be transitioned to close outpatient followup with rheumatologists and ophthalmologists. Given that approximately 10% of the patients had persistent abducens nerve palsy, future studies are warranted to recognize who is at risk of prolonged or permanent sixth nerve palsy based on baseline demographics or clinical characteristics. In these cases, treatments such as pulse dose glucocorticoids or anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibodies could be an option pending further accumulation of evidence, although it remains uncertain if the sixth cranial nerve palsy in GCA is a prodromal symptom of vision loss, given its association with the cranial and pericranial ischemic. Further investigation to see the association with prospective studies is necessary.

There are several limitations to the study. First, authors could not be contacted to obtain data not mentioned in the literature. We specifically included not only peer-reviewed articles but also conference abstracts or preprints, leading to uncertainty in the evidence level discussed. However, the risk of reporting bias was reduced as a result. Second, there is a limited number of prospective studies, and the study included a small number of patients. Furthermore, for statistical case analysis, only data from well-documented existing case reports and case series were included to identify the clinical characteristics of the included cases with the level of detail required for the in-depth investigation. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to investigate the detailed characteristics of sixth cranial nerve palsy in GCA. The data presented may be beneficial for physicians to use for determining diagnostic or treatment plans for such cases.

In conclusion, this review summarizes the current evidence and characteristics of the sixth nerve palsy in GCA. While most patients may have transient and reversible clinical courses, ophthalmoplegia is a potentially missed yet crucial clinical finding in those with GCA. Given many differential diagnoses for the sixth nerve palsy that potentially complicate the clinical scripts, increased awareness of the sixth nerve palsy in GCA and its differential diagnosis is crucial. Since a small portion of patients suffer from persistent or permanent abducens nerve palsy, future studies are warranted to identify factors associated with nonreversibility and the benefits of early and high-intensity treatment, such as pulse dose glucocorticoids or anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibodies, in the population.

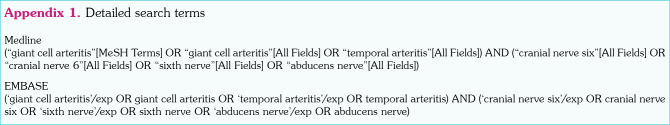

Appendix 1. Detailed search terms.

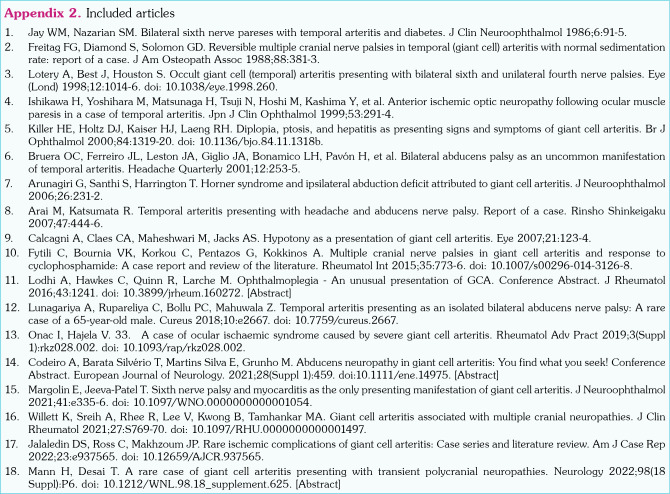

Appendix 2. Included articles.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics Committee Approval: Since this is a systematic review, no ethics committee approval was required.

Author Contributions: Searched the literature, assessed the quality of the studies, drafted, and revised the manuscript: H.S., Y.N.; Both supervised the process: Y.N., H.T.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Financial Disclosure: The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Citation: Sawada H, Nishimura Y, Tamaki H. Sixth cranial nerve palsy in giant cell arteritis: A systematic review. Arch Rheumatol 2024;39(3):479-487. doi: 10.46497/ ArchRheumatol.2024.10528.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Soriano A, Muratore F, Pipitone N, Boiardi L, Cimino L, Salvarani C. Visual loss and other cranial ischaemic complications in giant cell arteritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13:476–484. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Castañeda S, Llorca J. Giant cell arteritis: Visual loss is our major concern. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:1458–1461. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haering M, Holbro A, Todorova MG, Aschwanden M, Kesten F, Berger CT, et al. Incidence and prognostic implications of diplopia in patients with giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1562–1564. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalaledin DS, Ross C, Makhzoum JP. Rare ischemic complications of giant cell arteritis: Case series and literature review. e937565Am J Case Rep. 2022;23 doi: 10.12659/AJCR.937565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issa M, Donaldson L, Jeeva-Patel T, Margolin E. Ischemic ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis: A Canadian case series. J Neurol Sci. 2022;436:120222–120222. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rucker CW. The causes of paralysis of the third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966;61:1293–1298. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(66)90258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rush JA, Younge BR. Paralysis of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. Cause and prognosis in 1,000 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:76–79. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010078006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park UC, Kim SJ, Hwang JM, Yu YS. Clinical features and natural history of acquired third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsy. Eye (Lond) 2008;22:691–696. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, Langlois EV, O'Brien KK, Horsley T, et al. Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nayak NV, Raikundalia M, Eloy JA. Epidemiologic characteristics of giant cell arteritis using a national inpatient database. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:5082–5082. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coronel Tarancón L, Monjo I, Fernández E, Balsa A, De Miguel E. Non ophtalmological neurologic ischaemic manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2018;77:1483–1483. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.5775.[Abstract]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laskou F, Aung TH, Gayford D, Banerjee S, Crowson C, Matteson E, et al. FRI0494 Spectrum of visual involvement in giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:774–775. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.3081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chazal T, Clavel G, Leturcq T, Philibert M, Lecler A, Vignal-Clermont C. Characteristics and prognosis of binocular diplopia in patients with giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2023 doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arai M, Katsumata R. Temporal arteritis presenting with headache and abducens nerve palsy. Report of a case. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2007;47:444–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arunagiri G, Santhi S, Harrington T. Horner syndrome and ipsilateral abduction deficit attributed to giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:231–232. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000235562.42894.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruera OC, Ferreiro JL, Leston JA, Giglio JA, Bonamico LH, Pavón H, et al. Bilateral abducens palsy as an uncommon manifestation of temporal arteritis. Headache Quarterly. 2001;12:253–255. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calcagni A, Claes CA, Maheshwari M, Jacks AS. Hypotony as a presentation of giant cell arteritis. Eye. 2007;21:123–124. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Codeiro A, Barata Silvério T, Martins Silva E, Grunho M. Abducens neuropathy in giant cell arteritis: You find what you seek! European Journal of Neurology. 2021;28(Suppl 1):459–459. doi: 10.1111/ene.14975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freitag FG, Diamond S, Solomon GD. Reversible multiple cranial nerve palsies in temporal (giant cell) arteritis with normal sedimentation rate: Report of a case. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1988;88:381–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fytili C, Bournia VK, Korkou C, Pentazos G, Kokkinos A. Multiple cranial nerve palsies in giant cell arteritis and response to cyclophosphamide: A case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:773–776. doi: 10.1007/s00296-014-3126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa H, Yoshihara M, Matsunaga M, Tsuji N, Hoshi M, Kashima Y, Ogiwara H. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy following ocular muscle paresis in a case of temporal arteritis. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol. 1999;53:291–294. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jay WM, Nazarian SM. Bilateral sixth nerve pareses with temporal arteritis and diabetes. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1986;6:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Killer HE, Holtz DJ, Kaiser HJ, Laeng RH. Diplopia, ptosis, and hepatitis as presenting signs and symptoms of giant cell arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1319–1320. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.11.1318b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lodhi A, Hawkes C, Quinn R, Larche M. Ophthalmoplegia - An unusual presentation of GCA. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:1241–1241. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160272.[Abstract]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lotery A, Best J, Houston S. Occult giant cell (temporal) arteritis presenting with bilateral sixth and unilateral fourth nerve palsies. Eye (Lond) 1998;12:1014–1016. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunagariya A, Rupareliya C, Bollu PC, Mahuwala Z. Temporal arteritis presenting as an isolated bilateral abducens nerve palsy: A rare case of a 65-yearold male. e2667Cureus. 2018;10 doi: 10.7759/cureus.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mann H, Desai T. A rare case of giant cell arteritis presenting with transient polycranial neuropathies. P6Neurology. 2022;98(18 Suppl) doi: 10.1212/WNL.98.18_supplement.625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolin E, Jeeva-Patel T. Sixth nerve palsy and myocarditis as the only presenting manifestation of giant cell arteritis. e335-6J Neuroophthalmol. 2021;41 doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onac I, Hajela V. 33. A case of ocular ischaemic syndrome caused by severe giant cell arteritis. rkz028.002Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2019;3(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1093/rap/rkz028.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willett K, Sreih A, Rhee R, Lee V, Kwong B, Tamhankar MA. Giant cell arteritis associated with multiple cranial neuropathies. S769-70J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27 doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buncic JR. Neuroophthalmic signs of vascular disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1978;18:123–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cordonnier M, Van Nechel C. Neuro-ophthalmological emergencies: Which ocular signs or symptoms for which diseases. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s13760-013-0188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinkin M. Diagnostic approach to diplopia. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2014;20:942–965. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000453310.52390.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jalota L, Freed R, Jain S. Isolated 6th nerve palsyan uncommon presentation of lyme's disease. S447-S448J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kung NH, Van Stavern GP. Isolated ocular motor nerve palsies. Semin Neurol. 2015;35:539–548. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lončarić K, Markeljević J, Gregurić T, Pažanin L, Grgić MV, Lovrenčić-Huzjan A, et al. Case of abducens palsy-clival pancreatic cancer metastasis extending into sphenoid and cavernous sinuses masquerading as giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2022 doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross AG, Jivraj I, Rodriguez G, Pistilli M, Chen JJ, Sergott RC, et al. Retrospective, multicenter comparison of the clinical presentation of patients presenting with diplopia from giant cell arteritis vs other causes. J Neuroophthalmol. 2019;39:8–13. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamhankar MA, Biousse V, Ying GS, Prasad S, Subramanian PS, Lee MS, et al. Isolated third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies from presumed microvascular versus other causes: A prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2264–2269. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.