Abstract

Introduction

Desmoid tumors (DT) are rare, locally invasive tumors originating from connective tissue. Surgical intervention is no longer the standard treatment for DT, as systemic therapy gradually replaces it due to its superior efficacy. Despite the availability of various treatment modalities, there is a need for a first-line systemic treatment regimen that offers both effective disease control and acceptable safety profiles.

Methods

To assess the efficacy and safety of different systemic treatment agents for DT, we conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eligible studies were identified through searches of PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library databases, and data were extracted according to predefined inclusion criteria.

Results

Three articles and clinical data from 295 patients with progressive and refractory DT were included in this Bayesian network meta-analysis. When considered by objective response rate (ORR), the efficacy of γ-secretase inhibitor versus placebo (OR 0.12, 95%CI 0.01–1.68) is superior to that of TKI (OR 0.49, 95%CI 0.03–7.62) and chemotherapy (OR 0.90, 95%CI 0.02–40.00). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-TKI (OR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.01–1.79) seemed to have the highest improvement in terms of 1-yr PFS rate, while chemotherapy seemed to have the highest improvement across all therapies in terms of 2-yr PFS rate across all therapies (OR, 0.06; 95 percent CI, 0.01–2.98). In terms of safety, the incidence of AEs is highest for γ-secretase inhibitor versus placebo (OR 0.16, 95%CI 0.02–1.55), while TKI is associated with the least AEs (OR 0.62, 95%CI 0.06–6.97).

Conclusion

γ-secretase inhibitor provides superior local control of tumors, while chemotherapy and TKI may offer better long-term survival benefits. Among the three regimens, TKI demonstrated better treatment-related safety. These findings have important implications for guiding clinical practice in systemic treatment of DT.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-024-01494-z.

Keywords: Aggressive fibromatosis, Desmoid tumor, Systemic treatment, Network meta-analysis

Highlights

The study conducted a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of systemic treatment options for progressive and refractory desmoid tumors.

The analysis included 3 RCT studies, and the primary clinical endpoints were progression-free survival and objective response rate.

The network meta-analysis showed that γ-secretase inhibitors have better tumor response and more severe toxicity, while chemotherapy and TKI may have better long-term survival benefits.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-024-01494-z.

Introduction

Desmoid tumors (DTs), also referred to as progressive fibromatosis, are rare, locally aggressive neoplasms originating from connective tissues. They occur across age groups but are more prevalent in adults, constituting approximately 0.03% of all tumors and less than 3% of soft tissue tumors [1]. Despite lacking distant metastasis potential, their progressive and aggressive nature can lead to severe complications and symptoms. DTs can manifest in various anatomical sites, with common locations including the abdomen, extremities, head, and neck [2]. As these tumors enlarge and exert pressure on adjacent tissues, patients often experience substantial pain, deformity, swelling, restricted mobility, functional impairment, and risks such as intestinal obstruction, perforation, and hydronephrosis [3]. Additionally, younger patients may face challenges such as prolonged opioid usage, social isolation, sleep disturbances, and psychological distress, potentially disrupting education and employment [4].

Managing DTs is challenging due to their variable and unpredictable clinical trajectories [2, 5]. Treatment modalities encompass active surveillance, surgery, ablation, systemic therapy, and radiation therapy, with selections tailored to factors like tumor location, symptoms, and disease progression [6]. While surgery historically dominated DT management, its associated morbidity, high recurrence rates, and functional limitations have prompted exploration of alternative approaches.[7, 8]. Systemic therapies encompass cytotoxic agents, hormonal therapies (e.g., estrogen or progesterone), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), γ-secretase inhibitors, and other investigational agents [9–12]. Hormonal therapy may be suitable for less aggressive DTs based on limited evidence from small-scale retrospective studies [13, 14]. For symptomatic or rapidly progressing cases endangering vital organs, TKIs (e.g., imatinib, sorafenib) or cytotoxic chemotherapies (e.g., liposomal doxorubicin, methotrexate, vinorelbine) are reasonable initial options [15–18]. However, TKI use may entail adverse effects (AEs) like neutropenia, rash, fatigue, hypertension, and abdominal pain [19]. Notably, γ-secretase inhibitors like nirogacestat and PF-03084014 have shown promising clinical outcomes in progressive DTs, with common low-grade AEs including diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, hypophosphatemia, and maculopapular rash [11, 20].

Current recommendations from the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) advocate for initiating active surveillance or systemic therapies alone in advanced DT, contingent on symptomatology [21]. Yet, no definitive therapeutic standard exists for progressive DTs necessitating systemic interventions according to French clinical guidelines, and the efficacy of various systemic treatments remains contentious [22, 23]. Therefore, there is a crucial need to refine and elucidate the efficacy and potential adverse events associated with diverse therapies. Through scrutinizing progression-free survival (PFS) and objective response rate (ORR), we conducted a comprehensive systematic review and network analysis of DT treatments to assess treatment responses and safety profiles, particularly focusing on grade ≥ 3 AEs.

This systematic review and network meta-analysis present, for the first time, a consolidated overview of the effectiveness and safety profiles of different systemic treatments for DT, aiming to foster standardized treatment protocols. Our findings underscore the variability in treatment effects under different survival parameters and emphasize the importance of tailoring treatments to individualized patient condition. Furthermore, we examined the specific AE profiles of different treatments to facilitate the implementation of appropriate therapies for distinct patient cohorts.

Methods

Search strategy

Systematic reviews and network meta-analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [24] (Supplementary Table S1). Before conducting this meta-analysis, the study was registered on the PROSPERO website (PROSPERO ID: CRD42023457444). Our search encompassed the Embase, PubMed, and Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) databases, spanning from inception to September 1, 2023. WWe employed combined phrases with their corresponding MESH search terms, including ("Desmoid tumor" OR "Aggressive fibromatosis" OR "Desmoid fibromatosis") AND ("Therapy" OR "Treatment"), with a filter for "clinical study" or "randomized controlled trial." The detailed search strategy is outlined in Supplementary Table S2. Each relevant reference underwent individual scrutiny to ensure credibility and accuracy. Three researchers independently retrieved relevant publications. Disagreements were resolved through discussions with senior researchers (R. Xie and S. Zhang). The literature review was updated upon completion of the procedure.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were defined as follows: (1) Patients diagnosed with desmoid tumors. (2) Intervention involving systemic treatment for desmoid tumor or placebo. (3) Outcome measures encompassed tumor response outcomes, survival rates, and adverse events. (4) Study design limited to randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Conversely, the exclusion criteria were delineated as: (1) Non-RCTs, reviews, case reports, letters, or expert opinions. (2) Studies lacking sufficient data to meet the research objectives. (3) Trials involving neonatal or pediatric patients.

Outcome measures

The outcomes assessed in this network meta-analysis were progression-free survival (PFS) and objective response rate (ORR), encompassing complete response (CR) + partial response (PR), as well as progressive disease (PD) + stable disease (SD) rates. Evaluation of these outcomes adhered to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. Safety outcomes focused on AEs graded as 3 or 4, defined as grade ≥ 3. AEs were classified according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) versions 5.0, as well as the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.0.

Data acquisition and quality evaluation

The texts underwent examination and analysis by three researchers (D Su, J. Ou, and Guan). Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions. Extracted general characteristics included study ID, follow-up period, sample size, patient age, patient sex, and details regarding the intervention and control arms. Assessment of the risk of bias within individual studies followed the Cochrane Handbook method for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [25]. Evaluation criteria encompassed random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessments (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other potential biases. The overall risk of bias was categorized as low (all items assessed as low risk, or at least five items deemed low risk with the remaining two uncertain), unclear (> two items rated as unclear risk), or high (one quality dimension indicating high bias).

Network meta-analysis

The network evidence diagram was generated using R 4.0.2 software (https://www.r-project.org/). To elucidate distinctions among various therapies, a Bayesian network meta-analysis was conducted, presenting pooled estimates of odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

To interpret the ORs, the surface under the cumulative ranking curves (SUCRA) [26] method was employed to compute the probability associated with each intervention. SUCRA values range from 1 to 0, where higher values indicate a superior rank for the intervention. Conversely, lower SUCRA values suggest a higher likelihood of the outcome. It is essential to exercise caution when interpreting SUCRA due to potential statistical discrepancies. To visually represent sample size and trial numbers, network plots of outcomes were generated using the "rjags" and "GeMtc" packages in R 4.0.2 [27]. the binconf() function from the "Hmisc" package was utilized to estimate incidence with a 95% confidence interval. Finally, ranking probability assessments were conducted using R.

Results

Study characteristics and quality evaluation

The initial search yielded 343 publications. However, after screening and selection procedures, this study included three papers encompassing a total of 295 participants [12, 18, 22]. Figure 1A illustrates the selection process in detail. Utilizing the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Fig. 1B), the overall risk of bias across the selected studies was determined to be low. Table 1 provides a summary of the key characteristics of these studies, with the median follow-up period ranging from 15.9 to 27.2 mo.

Fig. 1.

Study characteristics and quality evaluation (A) Flowchart for the process of screening out the included studies. B Quality assessment of each included study

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies for progressive and refractory desmoid tumors

| Study (yr) | Sample size | Median age | Sex of male (%) | Median follow-up (mo) | Intervention arm 1 | Intervention arm 2 | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gounder et al. (2018)[22] | 87 | 37 | 27 | 27.2 | Sorafenib (400 mg) | Placebo |

Tumor response outcomes (CR, PR, SD, PD, ORR) Survival rates (PFS, OS, mPFS) AEs (CTCAE, version 4.03) |

| Toulmonde et al. (2019)[18] | 72 | 38 | 36 | 23.4 | Pazopanib (800 mg) | Methotrexate (30 mg/m2) + Vinblastine (5 mg/m2) |

Tumor response outcomes (PR, SD, PD, ORR) Survival rates (PFS) AEs (NCI-CTCAE version 4.0) |

| Gounder et al. (2023) [12] | 142 | 35 | 50 | 15.9 | Nirogacestat (150 mg) | Placebo |

Tumor response outcomes (CR, PR, SD, PD, ORR) Survival rates (PFS, mPFS) AEs (CTCAE, version 5.0) |

CR complete response, PR partial response, PD progressive disease, SD stable disease, ORR objective response rate, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, mPFS median progression-free survival, AEs adverse events

Efficacy outcomes

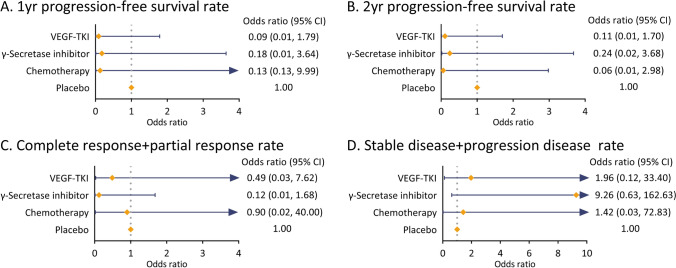

The study evaluated the efficacy of various systemic therapies in DT based on PFS, ORR, and HR for PFS (Table 2). Sorafenib showed a superior 1-yr and 2-yr PFS rates of 89% and 81%, with an ORR of 33%. The HR for PFS was 0.13, indicating a lower risk of progression compared to placebo. Pazopanib demonstrated a 1-yr and 2-yr PFS rates of 85.6% and 67.2%, with an ORR of 17% and an HR for PFS of 0.29, while the combination of Methotrexate and Vinblastine had comparable PFS rates (1-yr: 79.0%, 2-yr: 79.0%) and an ORR of 25%. Nirogacestat exhibited a 1-yr PFS of 85%, dropping to 76% at 2 years, with an ORR of 41% and a median PFS of 15.1 mo compared to placebo. Figure 2 depicts the network of the efficacy and safety comparisons. Regarding the 1-yr PFS rate, TKI (OR, 0.09; 95% CI 0.01–1.79) appeared to exhibit the highest improvement among all therapies compared to placebo, followed by chemotherapy (OR, 0.13; 95% CI 0.13–9.99) and γ-secretase inhibitor (OR, 0.18; 95% CI 0.01–3.64; Fig. 3A). For the 2-yr PFS rate, chemotherapy (OR, 0.06; 95% CI 0.01–2.98) demonstrated the highest improvement, followed by TKI (OR, 0.11; 95% CI 0.01–1.70) and γ-secretase inhibitor (OR, 0.24; 95% CI 0.02–3.68) compared to placebo (Fig. 3B). The ranking of 2-yr PFS rates after systemic treatment for progressive and refractory DT was as follows: chemotherapy (Ranking probability 65%), VEGF-TKI (59%), γ-secretase inhibitor (58%), and placebo (83%; Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Summary of drug effectiveness of systemic therapy for desmoid tumors

| Gounder et al.(2018)[22] | Toulmonde et al. (2019)[18] | Gounder et al. (2023)[12] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib (n = 49) | Placebo (n = 36) | Pazopanib (n = 48) | Methotrexate and vinblastine (n = 22) | Nirogacestat (n = 69) | Placebo (n = 72) | |

| 1 yr-PFS rate (%) | 89 (95%CI 80–99) | 46 (95%CI 32–67) | 85.6 (95%CI 70.7–93.2) | 79.0 (95%CI 53.2–91.5) | 85 (95%CI 73–92) | 53 (95%CI 40–64) |

| 2 yr-PFS rate (%) | 81 (95%CI 69–96) | 36 (95%CI 22–57) | 67.2 (95%CI 49.0–81.9) | 79.0 (95%CI 53.2–91.5) | 76 (95%CI 61–87) | 44 (95%CI 32–56) |

| ORR (%) | 33 | 20 | 17 | 25 | 41 | 8 |

| Median PFS (mo) | NE | NM | NE | NE | NE | 15.1 (95%CI:8.4-NE) |

| HR for PFS | 0.13 (95CI 0.05–0.31) | NM | 0.29 (95%CI 0.15–0.55) | |||

NE not estimable, NM not mentioned, PFS progression-free survival, HR hazard ratio

Fig. 2.

Comparison network diagrams showing three outcomes of various therapies in patients with progressive and refractory desmoid tumor. The network graphs demonstrate how various treatments compare. Each vertex symbolizes a different form of therapy, with the size of the vertexes denoting the intervention sample size. The number of trials compared is shown by the thickness of the straight line

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of multiple treatments results for efficacy outcomes with placebo as reference compound

Fig. 5.

Ranking plot of Surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) for outcomes

In terms of ORR, γ-secretase inhibitor (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.01–1.68) appeared to have the best response among all therapies in terms of complete response (CR) + partial response (PR) rate compared to placebo, followed by TKI (OR, 0.49; 95% CI 0.03–7.62) and chemotherapy (OR, 0.90; 95% CI 0.02–40.00; Fig. 3C). According to the ranking plot, γ-secretase inhibitors (77%) and VEGF-TKIs (47%) appeared to be the most promising treatments, with the highest likelihood of tumor response efficacy (Fig. 5). In terms of stable disease (SD) + progressive disease (PD) rate, γ-secretase inhibitor (OR, 9.26; 95% CI 0.63–162.63) also showed the lowest risk of control failure compared to placebo across various therapies, followed by TKI (OR, 1.96; 95% CI 0.12–33.40) and chemotherapy (OR, 1.42; 95% CI 0.03–72.83; Fig. 3D).

Safety outcomes

Three studies were included in safety analysis. γ-secretase inhibitor (OR, 0.16; 95% CI 0.02–1.55) appeared to have the highest AE occurrence rate among all therapies compared to placebo, followed by chemotherapy (OR, 0.24; 95% CI 0.01–7.18) and TKI (OR, 0.62; 95% CI 0.06–6.97). Figure 4 illustrates the odds ratios for safety events obtained from the network meta-analysis. In terms of safety, systemic treatment options can be summarized as follows: γ-secretase inhibitor (Ranking probability 57%) carried the highest risk of adverse events, followed by chemotherapy (40%) and VEGF-TKI (52%; Fig. 5). Table 3 presents recorded AEs of systemic therapy for DT. Common AEs related to TKI include palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome, rash, fatigue, hypertension, diarrhea, and nausea or vomiting. For γ-secretase inhibitor, common AEs were fatigue, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, and increase of AST or ALT. These findings provide insights into the spectrum and severity of adverse effects experienced by patients undergoing systemic therapy for desmoid tumors.

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of multiple treatments results for safety outcomes with placebo as reference compound

Table 3.

Summary of recorded adverse events of systemic therapy for desmoid tumors

| Gounder et al.(2018)[22] | Toulmonde et al. (2019)[18] | Gounder et al. (2023)[12] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE event | Sorafenib (n = 49) (%) | Placebo (n = 36) (%) | Pazopanib (n = 48) (%) | Methotrexate and vinblastine (n = 22) (%) | Nirogacestat (n = 69) (%) | Placebo (n = 72) (%) | ||||

| Grade | 1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | 1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | 1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | 1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | Any | Any |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 34 (69) | 1 (2) | 8 (22) | 0 | 16 (33) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Rash | 36 (73) | 7 (14) | 15 (42) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 13 (19) | 5 (7) |

| Pruritus | 7 (14) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fatigue | 33 (67) | 3 (6) | 22 (61) | 1 (3) | 36 (75) | 3 (6) | 14 (64) | 1 (5) | 35 (51) | 26 (36) |

| Hypertension | 27 (55) | 4 (8) | 14 (39) | 0 | 12 (25) | 10(21) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Diarrhea | 25 (51) | 0 | 12 (33) | 0 | 31 (65) | 7 (15) | 7 (32) | 0 | 58 (84) | 25 (35) |

| Nausea or vomiting | 34 (69) | 1 (2) | 20 (56) | 3 (8) | 26(54) | 0 | 16 (73) | 0 | 51(74) | 42 (58) |

| Myalgia | 18 (37) | 1 (2) | 12 (33) | 0 | 8 (17) | 0 | 4 (18) | 1 (5) | NA | NA |

| Alopecia | 18 (37) | 0 | 3 (8) | 0 | 6 (13) | 0 | 4 (18) | 0 | 13 (19) | 1 (1) |

| Arthralgia | 17 (35) | 1 (2) | 9 (25) | 0 | 9 (19) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Abdominal pain | 15 (31) | 1 (2) | 9 (25) | 4 (11) | 8 (17) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 11 (16) | 9 (12) |

| Anorexia | 15 (31) | 0 | 9 (25) | 0 | 16 (33) | 0 | 4 (18) | 0 | NA | NA |

| Constipation | 11 (22) | 0 | 4 (11) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | 8 (36) | 0 | 11 (16) | 8 (11) |

| Oral mucositis | 11 (22) | 0 | 6 (17) | 0 | 13 (27) | 0 | 7 (32) | 0 | 20 (29) | 3 (4) |

| Anemia | 8 (16) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (2) | 5 (23) | 0 | NA | NA |

| AST or ALT increase | 12 (24) | 1 (2) | 7 (19) | 0 | 10 (21) | 2 (4) | 2 (9) | 4 (18) | 32(46) | 14(19) |

Discussion

The treatment regimen involving methotrexate and vincristine for DTs traces back to the last century, primarily administered to patients with poor postoperative prognosis and not deemed suitable for surgery [28]. In our network meta-analysis, although chemotherapy exhibited moderate performance in ORR, it demonstrated decent safety profiles. Moreover, the PFS data associated with chemotherapy suggests effective systemic disease control and delay in progression onset. Previous retrospective studies have indicated a higher response rate with the combination of methotrexate and vincristine regimen. Nishida et al. reported prospective treatment outcomes of this chemotherapy combination in 2015, with 40% of patients experiencing PR and only one patient showing PD [29]. Subsequent research by the same team after five years revealed that with the same low-dose chemotherapy regimen administered every two weeks, the PR rate increased to 51%, and the 5-yr PFS improved to 80.8% [9]. Although both studies exclusively enrolled patients with CTNNB1 mutation subtypes, given reports indicating that mutation subtypes were not associated with systemic treatment response [30], this difference might be attributed to the early treatment initiation among enrolled patients, as almost all received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) treatment before chemotherapy. Despite chemotherapy's ability to stabilize the disease in refractory DT patients, severe bone marrow toxicity has hindered its adoption as the preferred treatment option [28]. Vinorelbine, a derivative of vincristine, exhibits lower toxicity, with significantly reduced reported grade ≥ 3 toxicity events in previous studies [31, 32]. When used alone for DT treatment, vinorelbine is well-tolerated. Similar to vincristine, vinorelbine can also be combined with methotrexate. Previous studies have demonstrated that low-dose methotrexate with vinorelbine can achieve up to an 81% objective response rate, with minimal occurrence of grade 1–2 toxicity events [33, 34].

Given the significant correlation between the development of desmoid tumors and abnormal β-catenin and overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [35], such as sorafenib and pazopanib have greatly improved the efficacy of desmoid tumor treatment. In our study, TKIs demonstrated superior safety profiles, higher ORR, and 1-yr PFS data compared to chemotherapy. When comparing the two TKIs in the meta-analysis, pazopanib exhibited slightly better ORR than sorafenib, albeit with poorer PFS and safety outcomes. Previous studies have consistently reported favorable efficacy and safety profiles for these agents. Gounder et al. observed significant symptom improvement in 16 out of 26 patients receiving sorafenib as first-line or follow-up treatment for desmoid tumors, with PR and SD rates of 25% and 70%, respectively [36]. Similarly, Garg et al. reported an ORR of 46.1% and a 1e-yr PFS of 86.6% for sorafenib [37]. Agresta et al. found that pazopanib demonstrated better tumor progression control and symptom relief compared to other treatments [38]. However, TKIs can lead to severe AEs, with up to 10.5% of patients discontinuing drug use in one study due to drug-related AEs [37]. In addition to serious AEs such as diarrhea and hypertension, reactive lymph node enlargement has also been reported as a side effect [39]. Several studies have suggested that reducing the initial dose of TKIs could mitigate these AEs. For instance, reducing the initial sorafenib dose from 400 to 200 mg significantly decreased the proportion of patients requiring cessation or dose reduction due to AEs, from 70 to 13%, without impacting ORR or PFS [37]. Similarly, a 25% reduction in pazopanib dosage has been shown to resolve most AEs without compromising ORR [38]. Moreover, newer VEGF-TKIs such as sunitinib and lenvatinib exhibit better targeting and resistance antagonism abilities. Further investigations and clinical trials are warranted to explore the potential of these agents in desmoid tumor treatment.

Multiple subtypes of DT, including sporadic DT and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)-associated DT, are closely associated with the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways. The development of γ-secretase inhibitors has emerged as a promising new approach for treating DT [40, 41]. To date, three γ-secretase inhibitors have been studied: nirogacestat, AL101, and AL102. Among them, nirogacestat has been the most extensively investigated, with research conducted by Gounder et al. representing the highest quality published research. When compared to TKIs, γ-secretase inhibitors have shown superior ORR and less PFS benefits. Other research reports have also confirmed the robust ORR associated with γ-secretase inhibitors. For instance, Kummar et al. reported that in a study of 16 patients, five achieved PR that lasted over two years, while the remaining eleven patients experienced long-term SD [11]. The study also documented AEs consistent with those reported by Gounder et al., including grade III hypophosphatemia in half of the patients and other toxic events ranging from grade I to grade II. In other reports, the PR was reported as high as 71.4%, albeit with a certain number of grade III AEs, ranging from 0% to 48.4% [20, 42, 43]. AL101 and AL102 still lack comprehensive and reliable research regarding DT treatment. When comparing γ-secretase inhibitors with TKIs, the former demonstrate greater advantages in PFS. In clinical practice, patients who are not surgical candidates may be more suitable for treatment with TKIs to prolong their PFS. Given the more severe AEs associated with γ-secretase inhibitors, they are more suitable as adjuvant therapy. For surgical candidates, adjuvant therapy with γ-secretase inhibitors after tumor resection may represent a potential new surgical combination therapy. Due to the recent emergence of γ-secretase inhibitors, the number of prior clinical studies and patient participation remains limited. More methods to enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity urgently need to be explored. Large-scale clinical trials are needed in the future to provide more evidence for the use of these drugs.

It is worth mentioning that among all DTs, FAP-associated DT is a relatively distinct type, exhibiting differentiated gene mutations, genetic lineages, and malignant phenotypes in comparison to sporadic DT, potentially necessitating additional considerations in treatment decisions. For patients with family history of FAP, DeFi study demonstrated that Nirogacestat had better efficacy on PFS (HR 0.24, 95% CI0.05–1.18) than placebo. For patients with sporadic DTs, Nirogacestat also showed promising effectiveness (HR 0.30, 95%CI 0.15–0.63). However, larger cohort is needed to distinguish the drug efficacy on sporadic and FAP-associated desmoids. Surgical intervention requires heightened caution. Evidence suggests that the prognosis following surgery may not be overly favorable, and the recurrence rate remains high. Owing to its intimate relationship with the intestine, surgeries often inevitably involve the mesentery, which may precipitate serious complications[44, 45]. Consequently, unless severe accompanying symptoms necessitate surgical intervention, active surveillance and pharmacotherapy remain paramount. Nonetheless, in terms of the effectiveness and safety of various drugs, minimal differences have been discerned in the existing evidence between FAP-associated and other DTs [44]. More clinical data validation is needed in the future.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, as DTs are rare with a low incidence rate, there is a scarcity of high-quality double-arm clinical trials available. In this study, we included only three articles, which may introduce some bias due to the limited literature available. Second, the final calculated OR values and their 95% confidence intervals for various clinical outcomes did not reach confirmed statistical significance. Although conclusions can be drawn based on ORs, there may be some degree of uncertainty due to potential accidental errors. Additionally, the selection of drugs such as chemotherapy and TKIs may vary, and the administration protocols and cycles of each drug can differ. Thus, there may be variations between the specific treatment plans analyzed in the included literature and real-world clinical practice experiences. To avoid potential heterogeneity in the comparisons of network meta-analysis, we added direct presentation of efficacy among the three studies by Table 2. With coming larger cohort and clinical trials in future, the results of this research may alternate.

Despite these limitations, our research also presents several strengths. The network meta-analysis approach addresses the limitation of previous clinical studies where different treatment regimens could not be directly compared. Moreover, the included studies are all prospective and of high quality, which helps mitigate potential biases to some extent. Our work integrates current evidence and contributes new insights to address controversial issues, which is valuable for informing clinical practice and guiding future research in this field.

Conclusion

In conclusion, γ-secretase inhibitors demonstrate superior tumor response but are associated with more severe toxicity, whereas chemotherapy and TKIs may offer better long-term PFS benefits. In clinical practice, treatment decisions should be based on a comprehensive evaluation of the patient's overall condition and tumor characteristics. For patients with unresectable DT, chemotherapy and TKIs may help reduce the risk of progression, while γ-secretase inhibitors may effectively shrink the tumor and provide symptomatic relief to some patients. Large-scale clinical trials are necessary to provide robust evidence to guide clinical practice in the management of DT.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- DT

Desmoid tumor

- TKI

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- PFS

Progression-free Survival

- ORR

Response Rate

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

- CR

Complete response

- PR

Partial response

- PD

Progressing disease

- SD

Stable disease

- AEs

Adverse events

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- NCI-CTCAE

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- SUCRA

Surface under the cumulative ranking curves

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SD.Z, RY.X Search and evaluation: JY.O, DD.S, YH.G, LY.G Data Analysis: RY.X, JY.O, YC.H Writing—original draft and Visualization: RY.X, JY.O, DD.S, YH.G, LY.G Writing-Review and Revision: RY.X, SD.Z, LY.G, SH.D, Y.Y, YC.H, and M.L. Supervision and Project Management: SD.Z, LY.G, SH.D, Y.Y, YC.H, M.L Resources: SD.Z, LY.G, SH.D, Y.Y, YC.H, M.L

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82273389].

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Junyong Ou, Dandan Su, and Yunhe Guan have contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors.

Ruiyang Xie and Shudong Zhang have contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-corresponding authors.

Contributor Information

Shudong Zhang, Email: zhangshudong@bjmu.edu.cn.

Ruiyang Xie, Email: xieruiyang@bjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Asaad SK, Abdullah AM, Abdalrahman SA, Fattah FH, Tahir SH, Omer CS, et al. Extra-abdominal recurrent aggressive fibromatosis: a case series and a literature review. Mol Clin Oncol. 2023;19:84. 10.3892/mco.2023.2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumert BG, Spahr MO, Von Hochstetter A, Beauvois S, Landmann C, Fridrich K, et al. The impact of radiotherapy in the treatment of desmoid tumours an international survey of 110 patients a study of the rare cancer network. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl. 2007. 10.1186/1748-717X-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prat A, Peralta S, Cuéllar H, Ocaña A. Hepatic pneumatosis as a complication of an abdominal desmoid tumor. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2007;25:897–8. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paty J, Maddux L, Gounder MM. Prospective development of a patient reported outcomes (PRO) tool in desmoid tumors: a novel clinical trial endpoint. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:11022–11022. 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.11022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukamoto S, Takahama T, Mavrogenis AF, Tanaka Y, Tanaka Y, Errani C. Clinical outcomes of medical treatments for progressive desmoid tumors following active surveillance: a systematic review. Musculoskelet Surg. 2023;107:7–18. 10.1007/s12306-022-00738-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riedel RF, Agulnik M. Evolving strategies for management of desmoid tumor. Cancer. 2022;128:3027–40. 10.1002/cncr.34332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasper B, Baumgarten C, Garcia J, Bonvalot S, Haas R, Haller F, et al. An update on the management of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis: a European Consensus Initiative between Sarcoma PAtients EuroNet (SPAEN) and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/soft tissue and bone sarcoma group (STBSG). Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2017;28:2399–408. 10.1093/annonc/mdx323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasper B, Baumgarten C, Bonvalot S, Haas R, Haller F, Hohenberger P, et al. Management of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis: a European consensus approach based on patients’ and professionals’ expertise - a sarcoma patients EuroNet and European organisation for research and treatment of cancer/soft tissue and bone sarcoma group initiative. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl. 1990;2015(51):127–36. 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishida Y, Hamada S, Urakawa H, Ikuta K, Sakai T, Koike H, et al. Desmoid with biweekly methotrexate and vinblastine shows similar effects to weekly administration: A phase II clinical trial. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:4187–94. 10.1111/cas.14626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Wang H, Wu X, Hong X, Luo Z. Phase II study of doxorubicin and thalidomide in patients with refractory aggressive fibromatosis. Invest New Drugs. 2018;36:114–20. 10.1007/s10637-017-0542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kummar S, O’Sullivan Coyne G, Do KT, Turkbey B, Meltzer PS, Polley E, et al. Clinical activity of the γ-secretase Inhibitor PF-03084014 in adults with Desmoid Tumors (aggressive fibromatosis). J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1561–9. 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gounder M, Ratan R, Alcindor T, Schöffski P, van der Graaf WT, Wilky BA, et al. Nirogacestat, a γ-Secretase Inhibitor for Desmoid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:898–912. 10.1056/NEJMoa2210140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiore M, Colombo C, Radaelli S, Callegaro D, Palassini E, Barisella M, et al. Hormonal manipulation with toremifene in sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl. 1990;2015(51):2800–7. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki R, Taki Y, Arai K, Sato S, Watanabe M. Complete Regression of an 8-cm desmoid fibromatosis after treatment with tamoxifen. Cureus. 2023;15: e37431. 10.7759/cureus.37431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benech N, Walter T, Saurin J-C. Desmoid Tumors and celecoxib with sorafenib. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2595–7. 10.1056/NEJMc1702562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chugh R, Wathen JK, Patel SR, Maki RG, Meyers PA, Schuetze SM, et al. Efficacy of imatinib in aggressive fibromatosis: results of a phase II multicenter Sarcoma Alliance for Research through Collaboration (SARC) trial. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2010;16:4884–91. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ananth P, Werger A, Voss S, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Janeway KA. Liposomal doxorubicin: effective treatment for pediatric desmoid fibromatosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017. 10.1002/pbc.26375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toulmonde M, Pulido M, Ray-Coquard I, Andre T, Isambert N, Chevreau C, et al. Pazopanib or methotrexate–vinblastine combination chemotherapy in adult patients with progressive desmoid tumours (DESMOPAZ): a non-comparative, randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1263–72. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bektas M, Bell T, Khan S, Tumminello B, Fernandez MM, Heyes C, et al. Desmoid Tumors: a Comprehensive review. Adv Ther. 2023;40:3697–722. 10.1007/s12325-023-02592-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi T, Prensner JR, Robson CD, Janeway KA, Weigel BJ. Safety and efficacy of gamma-secretase inhibitor nirogacestat (PF-03084014) in desmoid tumor: Report of four pediatric/young adult cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67: e28636. 10.1002/pbc.28636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, et al. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2018. 10.1093/annonc/mdy096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gounder MM, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, Ravi V, Attia S, Deshpande HA, et al. Sorafenib for Advanced and Refractory Desmoid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2417–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1805052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benech N, Bonvalot S, Dufresne A, Gangi A, Le Péchoux C, Lopez-Trabada-Ataz D, et al. Desmoid tumors located in the abdomen or associated with adenomatous polyposis: French intergroup clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up (SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO, ACHBT, SFR). Dig Liver Dis Off J Ital Soc Gastroenterol Ital Assoc Study Liver. 2022;54:737–46. 10.1016/j.dld.2022.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial n.d. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-08 Accessed 30 Aug 2023.

- 26.Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JPA. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:163–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staff TPO. Correction: network meta-analysis using r: a review of currently available automated packages. PLoS ONE. 2015;10: e0123364. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azzarelli A, Gronchi A, Bertulli R, Tesoro JD, Baratti D, Pennacchioli E, et al. Low-dose chemotherapy with methotrexate and vinblastine for patients with advanced aggressive fibromatosis. Cancer. 2001;92:1259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, Urakawa H, Hamada S, Kozawa E, Ikuta K, et al. Low-dose chemotherapy with methotrexate and vinblastine for patients with desmoid tumors: relationship to CTNNB1 mutation status. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:1211–7. 10.1007/s10147-015-0829-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nathenson MJ, Hu J, Ratan R, Somaiah N, Hsu R, DeMaria PJ, et al. Systemic chemotherapies retain antitumor activity in desmoid tumors independent of specific mutations in CTNNB1 or APC: a multi-institutional retrospective study. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2022;28:4092–104. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gennatas S, Chamberlain F, Smrke A, Stewart J, Hayes A, Roden L, et al. A timely oral option: single-agent vinorelbine in desmoid tumors. Oncologist. 2020;25:e2013–6. 10.1002/ONCO.13516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mir O, Honoré C, Chamseddine AN, Dômont J, Dumont SN, Cavalcanti A, et al. Long-term outcomes of oral vinorelbine in advanced, progressive desmoid fibromatosis and influence of CTNNB1 mutational status. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2020;26:6277–83. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ingley KM, Burtenshaw SM, Theobalds NC, White LM, Blackstein ME, Gladdy RA, et al. Clinical benefit of methotrexate plus vinorelbine chemotherapy for desmoid fibromatosis (DF) and correlation of treatment response with MRI. Cancer Med. 2019;8:5047–57. 10.1002/cam4.2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S, Fan Z, Fang Z, Liu J, Bai C, Xue R, et al. Efficacy of vinorelbine combined with low-dose methotrexate for treatment of inoperable desmoid tumor and prognostic factor analysis. Chin J Cancer Res Chung-Kuo Yen Cheng Yen Chiu. 2017;29:455–62. 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2017.05.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matono H, Tamiya S, Yokoyama R, Saito T, Iwamoto Y, Tsuneyoshi M, et al. Abnormalities of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway induce tumour progression in sporadic desmoid tumours: correlation between β-catenin widespread nuclear expression and VEGF overexpression. Histopathology. 2011;59:368–75. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gounder MM, Lefkowitz RA, Keohan ML, D’Adamo DR, Hameed M, Antonescu CR, et al. Activity of Sorafenib against desmoid tumor/deep fibromatosis. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2011;17:4082–90. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garg V, Gangadharaiah BB, Rastogi S, Upadhyay A, Barwad A, Dhamija E, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of sorafenib in desmoid-type fibromatosis: a need to review dose. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl. 1990;2023(186):142–50. 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agresta L, Kim H, Turpin BK, Nagarajan R, Plemmons A, Szabo S, et al. Pazopanib therapy for desmoid tumors in adolescent and young adult patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65: e26968. 10.1002/pbc.26968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papadopoulos S, Koulouris P, Royer-Chardon C, Tsoumakidou G, Dolcan A, Cherix S, et al. Case Report: tyrosine kinase inhibitors induced lymphadenopathy in desmoid tumor patients. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13: 794512. 10.3389/fendo.2022.794512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Federman N. Molecular pathogenesis of desmoid tumor and the role of γ-secretase inhibition. Npj Precis Oncol. 2022;6:1–8. 10.1038/s41698-022-00308-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shang H, Braggio D, Lee Y-J, Al Sannaa GA, Creighton CJ, Bolshakov S, et al. Targeting the Notch pathway: a potential therapeutic approach for desmoid tumors. Cancer. 2015;121:4088–96. 10.1002/cncr.29564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Messersmith WA, Shapiro GI, Cleary JM, Jimeno A, Dasari A, Huang B, et al. A Phase I, dose-finding study in patients with advanced solid malignancies of the oral γ-secretase inhibitor PF-03084014. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2015;21:60–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villalobos VM, Hall F, Jimeno A, Gore L, Kern K, Cesari R, et al. Long-term follow-up of desmoid fibromatosis treated with PF-03084014, an oral gamma secretase inhibitor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:768–75. 10.1245/s10434-017-6082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang W, Ding P-R. Update on familial adenomatous polyposis-associated desmoid tumors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2023;36:400–5. 10.1055/s-0043-1767709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinberger AE, Westfal ML, Wise PE. Surgical decision-making in familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2024;37:191–7. 10.1055/s-0043-1770732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.