Abstract

Public health and clinical medicine should identify and characterize modifiable risk factors for skin cancer in order to facilitate primary prevention. In existing literature, the impact of occupational exposure on skin cancer, including malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers, has been extensively studied. This review summarizes the available epidemiological evidence on the significance of occupational risk factors and occupations associated with a higher risk in skin cancer. The results of this review suggest that there is sufficient epidemiological evidence to support the relationship between the increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancers and occupational exposure to solar radiation, ultraviolet radiation, ionizing radiation, arsenic and its compounds, and mineral oils. Occupational exposure to pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls appears to provide sufficient epidemiological evidence for melanoma, and a higher risk of melanoma has been reported among workers in petroleum refining and firefighters. This comprehensive analysis will establish a foundation for subsequent investigations and developing targeted interventions of focused preventive measures against skin cancer among the working population.

Keywords: Skin Neoplasms, Melanoma, Risk Factors, Occupational Exposure, Occupations, Radiation

INTRODUCTION

Skin cancer is characterized by the abnormal growth of skin cells.1 There are different types of skin cancers, such as basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and malignant melanoma (MM), each originating from various skin cell types and each presenting different characteristics. Although many skin cancers are treatable, they can cause substantial morbidity without early detection, particularly if advanced.

The risk factors for skin cancer include overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun, artificial sources such as tanning beds, fair skin tone, severe sunburns, living closer to the equator or in high-altitude areas where UV radiation is more intense, a large number of moles or atypical moles (dysplastic naevi), family history, and conditions or medications that suppress the immune system.2 In addition to well-established risk factors, job-related factors are considered modifiable risk factors for skin cancer. The concentration of carcinogens in workplaces is typically higher than that in non-work settings. Occupational cancer can develop when workers are exposed to specific risk factors or a combination of these factors. Fortunately, almost all occupational exposure to carcinogens is theoretically preventable through appropriate protective measures. However, this is only possible when occupational risk factors are properly recognized.3

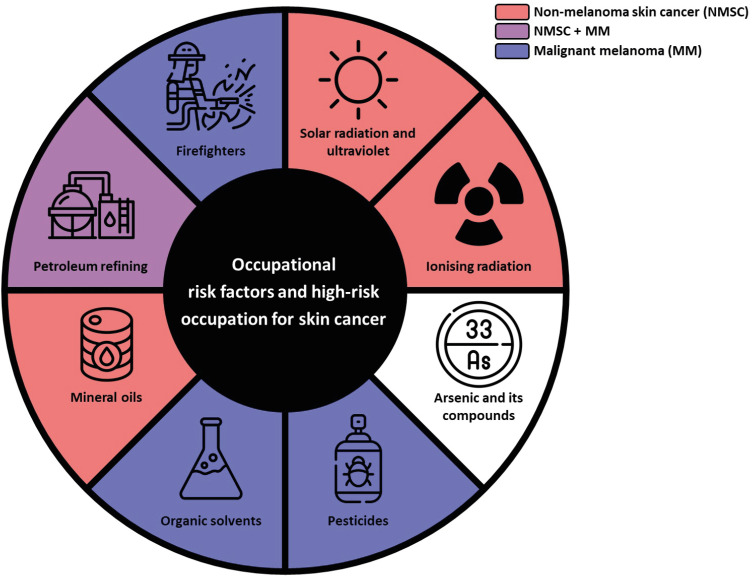

Therefore, this review aimed to summarize the available epidemiological evidence on occupational risk factors and high-risk occupation for skin cancer (Fig. 1). In addition, we reviewed the evidence for occupations associated with a higher risk for skin cancer. Given that mechanisms of skin cancer development might differ depending on the types of skin cancers, as well as exposure, review was conducted separately to MM and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). This distinction could help in understanding carcinogenesis pathways and developing more targeted and effective prevention strategies, addressing specific occupational risks, and implementing effective interventions for each skin cancer category.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram summarizing the possible occupational risk factors for skin cancer.

NMSC = non-melanoma skin cancer, MM = malignant melanoma.

EVIDENCES IN PREVIOUS RESEARCH

Solar and UV radiation

Solar rays span a spectrum of electromagnetic waves with infrared (50%), visible (45%), and UV radiation (5%). UV radiation can be divided into three types: long-wave UVA (315–400 nm), medium-wave UVB (280–315 nm), and short-wave UVC (100–280 nm). The Earth’s ozone layer absorbs UVB and UVC below 290 nm, controlling the amount that reaches the surface. This absorption regulates the amount of UVC and UVB radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. However, observations indicate ongoing depletion of the ozone layer due to the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, resulting in increased levels of UVB reaching the Earth’s surface.4

UV radiation can cause considerable damage to the skin and long-term cumulative exposure can directly affect the development of skin cancer. Short-term intense sun exposure is an important cause of melanoma and BCC, whereas long-term continuous sun exposure is associated with development of SCC.5 The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies UV radiations as Group 1 carcinogens.6 Typical skin cancers induced by UV radiation include NMSC such as BCC and SCC.

NMSC

In previous IARC papers, the causal relationship of UV radiation with BCC, SCC, and actinic keratosis (AK) was assessed through numerous epidemiological studies.6 These studies have demonstrated that UV radiation is a strong risk factor for NMSC, particularly in individuals with lighter skin tones. A review conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO) postulated a causal relationship between work-related UV exposure and NMSC.7 Recognition of occupational exposure to UVR primarily pertains to outdoor workers, such as agricultural workers, construction workers, and others who spend significant amounts of time outdoors during peak sunlight hours. These individuals are at a higher risk of prolonged and intense UV exposure compared to the general population. However, most epidemiological studies and evaluations are based predominantly on descriptive data from Caucasian populations, indicating the lack of research among non-Caucasian ethnicities due to low incidence.8

According to a systematic review by Loney et al.9 involving 19 studies, 18 reported an increased risk estimate for BCC and/or SCC among outdoor workers. All four studies reporting risk estimates for specific occupations indicated a significantly higher risk among agricultural workers. According to a case-control study comparing the prevalence of NMSC between outdoor and indoor workers in Europe, mountain guides (odds ratio [OR], 5.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.4–14.6), gardeners (OR, 4.0; 95% CI, 1.7–9.5), and farmers (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.0–5.0) exhibited significantly higher risks of NMSC compared to indoor workers.10 In another case-control study targeting Europeans, outdoor worker groups, excluding agricultural and construction workers, exhibited significant increases in AK (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.09–2.18) and BCC (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.39–2.41), whereas agricultural and construction workers showed higher risks for AK (OR, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.93–3.44), SCC (OR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.97–3.88), and BCC (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.80–2.96). Moreover, a significant elevation in all skin cancer risks was observed with over 5 years of exposure to outdoor work (AK, 3.45; BCC, 3.32; SCC, 3.67; melanoma in situ, 3.02; MM, 1.97; all P < 0.05).11 Likewise, analysis of cancer registry data from Germany showed that relative risks (RRs) of NMSC incidence among outdoor workers were significantly higher for males with BCC (RR, 2.9; 95% CI, 2.2–3.9) and SCC (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.4–4.7) and for females with BCC (RR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.8–4.1) and SCC (RR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.6–8.1), all showing statistically significant elevations.12

MM

There is convincing evidence that UV exposure is a major environmental factor in the development of MM, especially in high-risk populations, although not all melanomas are directly related to sun exposure.13

However, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury, reported research on “occupational” exposure to solar UV radiation commonly shows weak, null, or negative associations with melanoma incidence, leading to an evaluation of “limited evidence for harmfulness” and a current low quality of available evidence.7 Subsequently, a case-control study from Italy published in 2023 reported no association between occupational UV exposure and melanoma.14

Summary of evidences

Exposure to sunlight and UV radiation has been extensively documented as the primary cause of skin cancer. Both BCC and SCC were strongly associated with occupational UV exposure. However, the relationship between occupational exposure to solar UV radiation and MM is unclear, but intense UV exposure can increase the risk; therefore, caution must not be neglected.

Ionizing radiation

Exposure to ionizing radiation causes various types of cancer, including leukemia, breast cancer, thyroid cancer, and lung cancer.15 The danger of ionizing radiation in skin cancer has been demonstrated in cases caused by radiation therapy of the head and neck,16 X-ray treatment of ringworms of the scalp,17 and atomic bombs.18

NMSC

Skin cancer caused by ionizing radiation usually manifests as NMSC, especially BCC, rather than melanoma.19 The latent period of BCC can range from 2 to 70 years after exposure to radiation of up to 30 Gy.20 The incidence also increases with co-exposure to sunlight, sun-sensitive skin, radiation exposure before the age of 20 years, and genetic factors.19 In addition, SCC is reportedly associated with radiation exposure. The latent period is estimated to be approximately 20 years, and radiodermatitis often presented beforehand.16

A cohort study of workers in Russian nuclear production facility who are occupationally exposed to low-dose ionizing radiation showed that the incidence of NMSC increased by more than twice if exposed to ionizing radiation at cumulative doses above 2.0 Sv.21 More recent results of analysis with workers in same facility chronically exposed to low dose ionizing radiation occupationally, showed that the excess RR of BCC per unit skin absorbed dose of external exposure (ERR/Gy) was 0.57 (95% CI, 0.24–1.06), whereas no significant association was shown for SCC.22

Because medical practitioners are frequently exposed to radiation, research has been conducted to investigate the risk of skin cancer in these occupations. A 2005 cohort study suggested that radiologic technologists had an elevated risk of BCC if they first worked during the 1950s or earlier, indicating that they were exposed to a higher dose of ionizing radiation at that time.23 The association was stronger among individuals with lighter compared to darker eye and hair colour. Another study limited the participants to Caucasian technologists in the U.S., and the results were consistent with those of other studies.24 The risk of BCC increased with radiation exposure before the age of 30 years and prior to 1960.

MM

Although MM is rarely associated with exposure to ionizing radiation, melanoma has been reported after radiation therapy.20 Fink and Bates25 suggested a causal relationship between ionizing radiation and melanoma by estimating radiation exposure with a relative risk of leukemia. An elevated relative risk of leukemia is positively correlated with an elevated relative risk of melanoma.

Occupational studies have been conducted on this topic. The relative risk of melanoma was 1.8-fold for radiologic technologists who started working before 1950, when the estimated occupational radiation exposure was higher. The relative risk was 2.4 for those who had worked more than 5 years before 1950, and 1.4 if they did not wear protective shields such as lead aprons.26 Moreover, pilots and flight attendants are known to have a higher prevalence of melanoma, considering their exposure to cosmic radiation,27 and a meta-analysis estimated a standardised incidence ratio over 2.28 However, in studies on flight-based occupations, it is difficult to distinguish the effects of ultraviolet radiation.

Summary of evidences

Overall, ionizing radiation is widely recognized as a cause of NMSC, especially BCC. Studies on radiology technologists and other medical professionals support the effects of radiation. The risk of MM could also be associated with exposure to ionizing radiation; however, the evidence for this is insufficient.

Arsenic and its compounds

While the general population ingests arsenic through food and beverages averaging between 20–300 mcg/day, occupational exposure to arsenic primarily occurs through inhalation and dermal absorption.29,30 The carcinogenic mechanism of arsenic involves the induction of oxidative stress, immune dysfunction, chromosomal abnormalities, and altered growth factors.31 Arsenic and inorganic arsenic compounds have been classified as group 1 carcinogens by the IARC, with sufficient evidence for NMSC.32

NMSC

The most prevalent skin cancers induced by arsenic include, SCC, BCC, and Bowen disease (SCC in situ).33 Smith et al.34 investigated the impact of arsenic exposure in drinking water on cancer mortality in Region II of Chile, revealing increased mortality rates for skin cancer (standardized mortality ratio [SMR], 7.7; 95% CI, 4.7–11.9 for men; SMR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.3–6.6 for women). Furthermore, Kim et al.35 studied 124 biopsy-proven NMSC cases and 125 matched controls and discovered higher levels of certain arsenic forms, such as total inorganic arsenic, trivalent and pentavalent arsenic, and monomethylarsonic acid, in the NMSC group. However, all of these results are based on non-occupational exposure through ingestion rather than occupational exposure.

While the study conducted with 618 NMSC cases and 527 hospital-based controls showed no significant association between occupational airborne arsenic exposure and NMSC (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 0.76–4.95), the adjusted OR significantly increased by co-exposure to sunlight in workplace (OR, 10.22; 95% CI, 2.48–42.07).36 This dramatic increase in risk can be attributed to the synergistic effect of arsenic and UV radiation. Additionally, arsenic can act as a co-carcinogen, enhancing the carcinogenic effects of UV radiation. This combined exposure leads to a higher likelihood of genetic mutations and the development of skin cancer. Karagas et al.37 conducted a case-control study in New Hampshire to investigate the impact of environmental arsenic levels on NMSC (284 SCC, 587 BCC, and 524 control cases). While there was no statistically signification association in individuals with toenail arsenic concentrations above the 97th percentile (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 0.92–4.66 for SCC; OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.74–2.81 for BCC), this may be linked to challenges in accurately modelling the dose-response relationship due to limited subjects at extreme exposure levels.

MM

Only a few studies have investigated the association between melanoma and arsenic exposure, and have shown statistically insignificant associations, although some data suggested a possible association between melanoma and arsenical pesticides.38 Bedaiwi et al.39 collected cross-sectional data from 36,418 participants (no cancer, n = 35,572; MM, n = 244; NMSC, n = 602). The results of analysis indicated that individuals with higher urinary arsenic had an adjusted OR of 1.87 (95% CI, 0.58–6.05) for MM and 2.23 (95% CI, 1.12–4.45) for NMSC.39 Langston et al.40 mirrored similar findings, suggesting an insignificant association between arsenic and drinking water or environmental soil.

Summary of evidences

While extensive research has reported an association between arsenic exposure in drinking water and NMSC, evidence of relationship between occupational exposure to arsenic and skin cancer has been insufficient.

Pesticides

The widespread use of pesticides causes environmental pollution and poses health risks to human.41 Pesticides are delivered to the body via several routes. In particular, the skin is the most exposed body organ when spraying pesticides in the field. Therefore, there are large amount of reports that the incidence of skin cancer significantly increased among farmers who used pesticides.42 According to the IARC classification, occupational exposure to arsenic and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) is a definite carcinogen for skin cancer,43 and these substances commonly comprise pesticides.

NMSC

Few studies have investigated the relationship between pesticides and NMSC. According to a study comparing British pesticide users with the general population, a significantly higher standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of NMSC was observed for both males (SIR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.00–1.23) and females (SIR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.06–2.82).44 However, the SMR was not statistically significant.

MM

A meta-analysis conducted in 2019 reported a significant association between pesticide use and cutaneous melanoma (CM) by analysing two case-control studies and seven cohorts.45 The risks were divided into four categories: herbicide-ever exposure, insecticide-ever exposure, any pesticide-ever exposure, and any pesticide-high exposure. The summary RRs for the categories are 1.85 (95% CI, 1.01–3.36], 1.57 (95% CI, 0.58–4.25), 1.31 (95% CI, 0.85–2.04), and 2.17 (95% CI, 0.45–10.36), respectively. Therefore, it has been suggested that individuals high exposed to pesticides have an increased risk of developing CM. In addition, according to a systematic review in 2020 on the correlation between pesticide applicators and cancer,46 the ORs of melanoma were 2.4 (95% CI, 1.2–4.9, trend P = 0.006) for mancozeb (≥ 63 days of exposure) and 2.4 (95% CI, 1.3–4.4, trend P = 0.003) for parathion (≥ 56 exposure days). For carbaryl, RR of melanoma was significantly higher with lifetime exposure exceeding 175 days (RR, 4.11; 95% CI, 1.33–12.75), ≥ 10 years (RR, 3.19; 95% CI, 1.28–7.92), or 10 days per year (RR, 5.5; 95% CI, 2.19–13.84), compared to individuals who had never used it. Another systematic review conducted in 2022 reported that men aged 60 years and older who were occupationally exposed to pesticides had an increased risk of death from melanoma compared to the general population (SMR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.5).47 Additionally, according to another meta-analysis conducted in 2023, two studies from the International Agricultural Cohort Consortium (AGRICOH) were reviewed and indicated that women had a significantly higher incidence of melanoma compared to the general population (meta-SIR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.01–1.38).48 The analysis only covered occupational exposure, and the type of pesticide was unspecified.

Pesticide use is high among farmers working outdoors, where co-exposure to solar radiation is common. This may further increase the risk of melanoma development. Case-control studies from Italy and Brazil found that people who used herbicides (glyphosate) and fungicides (mancozeb, maneb) had a higher risk of developing melanoma compared to controls (OR, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.18–5.65).49 Particularly, the risk was higher when sun exposure was combined with pesticide use (OR, 4.68; 95% CI, 1.29–17.0).

Summary of evidences

Numerous studies have been conducted over several decades and a correlation between pesticides and skin cancers has been established. The association with MM has been frequently reported. As the same trend was observed in the results after controlling for variables related to solar radiation exposure, the influence of pesticides can be explained. However, most information on exposure is obtained through questionnaires, making it difficult to obtain strong trust. Moreover, as farmers spend a lot of time working outdoors in the sunlight, this factor cannot be completely excluded when evaluating the relationship between pesticides and skin cancer.38

Organic solvents

Organic solvents are carbon-containing substances that dissolve or disperse one or more substances.50 Trichloroethylene (TCE), tetrachloroethylene, carbon tetrachloride, methylene chloride, benzene, styrene, and similar compounds are examples of solvent constituents. They are commonly used in paints, varnishes, lacquers, adhesives, glues, degreasing agents, and cleaning agents to produce dyes, polymers, plastics, textiles, printing inks, agricultural products, and pharmaceuticals. The skin is a significant exposure route for organic solvents.

Some organic solvents are associated with cancers of the liver, kidney, lungs, haematopoietic system, and bladder.51 PCBs, which can also be found in certain industrial applications and pesticide formulations, are involved in various aspects of tumour promotion and progression and are classified as Group 1 carcinogens by the IARC.52 Particularly, “dioxin-like PCBs” activate aryl hydrocarbon receptors, which can modulate melanogenesis. This suggests a potential association between PCB exposure and an elevated risk of melanoma.

NMSC

Based on a consensus study reported by the Institute of Medicine, an association between TCE and NMSC was suspected, although only one study reported a statistically significant result.53 For the other organic solvents, six studies reported statistically insignificant associations.

MM

According to IARC Monograph volume 107, an association between PCB exposure and melanoma has been reported in several studies.52 However, recent studies reported contradictory results. In a meta-analysis published in 2017, even though the pooled SMR was statistically significant (SMR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.05–1.64), the cohort studies used had several limitations in research design such as major confounders like sun exposure.54 Another meta-analysis in 2018 reported insignificant correlation: the summary RR in random effect model was 1.13 (95% CI, 0.91–1.35) and the results from occupational cohorts and general population studies are close, even though the occupational exposures include higher concentrations.55

For substances other than PCB, the evidence of their association with melanoma is limited. In a consensus report by the Institute of Medicine, a compilation of epidemiological studies was presented.53 Among the five studies on TCE exposure, statistically significant associations were reported in one case-control study, although the number of exposed cases was limited.56 Statistically insignificant associations were observed in two studies using tetrachloroethylene and dry-cleaning solvents. In eight studies on other solvents, there was a statistically insignificant overall increase in risk. Additionally, for toluene and xylene, there were reverse significant correlations, even though the number of cases was small (5 cases for Toluene, estimated RR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1–0.9; 3 cases for Xylene, estimated RR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8).53 These inverse associations may indicate a potential confounding factor reducing the observed risk. The mechanisms behind these observations could involve competitive inhibition of metabolic pathways essential for carcinogenesis or differences in exposure levels and bioavailability that reduce the effective dose reaching target tissues.

However, other studies have reported a significant association. For example, a case-control study on chlorinated solvent exposure investigated 3,730 cancer cases and 533 control subjects, including 103 cases of melanoma. A significant association between melanoma and TCE was observed (for any exposure, OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.2–7.2; for substantial exposure, OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.0–9.9).57 In a meta-analysis of melanoma risk in industrial worker, three studies analysing the chemical industry showed a SIR of 2.08 (95% CI, 0.47–9.24), similarly, the meta-analysis of eight studies in the same context reported a SMR of 2.01 (95% CI, 1.09–3.72).58 The identified hazardous factors were primarily associated with polyvinyl chloride and vinyl chloride monomers which are commonly used as intermediates or solvents in the synthesis of organic compounds in industrial processes.

Summary of evidences

Most organic solvents act as skin irritants, and many have been confirmed to be carcinogenic. However, evidence of their association with skin cancer is currently inconsistent and contradictory. Although PCBs were classified as Group 1 by the IARC in 2016, subsequent research showed controversial results regarding the association between occupational PCB exposure and melanoma. Therefore, additional studies are needed to strengthen and re-evaluate this evidence.

Mineral oils

Mineral oils (sometimes referred to as base oils, mineral base oils, or lubricant base oils) are chemically complex and have various combinations of straight and branched-chain paraffinic, naphthenic, and aromatic hydrocarbons, which are refined from petroleum crude oils.59 They are used in the manufacture of a wide range of products, such as lubricants and non-lubricants, for various applications. Engine, transmission, gear, hydraulic, and metalworking fluids are examples of lubricant products, whereas printing inks, tire oils, and agricultural spray oils are examples of non-lubricant products.

Mineral oils may contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and other chemical additives together with biocides to limit microbiological contamination.60 The carcinogenicity of oil-based fluids is determined by how basic oils are treated, and the compounds added to them to improve their performance as coolants and lubricants. The removal of PAH from mineral oils began in the 1950s when the association between machining fluids and skin cancer began to appear. Oils that have undergone solvent extraction and hydrotreatment have fewer PAH, which lowers their carcinogenic potential.

NMSC

In 1984, the IARC classified untreated and mildly treated oils as Group 1 carcinogens with sufficient evidence from human studies.61 A few years later, The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) came to a similar conclusion.62 The evaluation by the IARC and NIOSH was mostly based on evidence of SCC of the skin, especially scrotal cancer. However, a risk assessment for cancer results from the United Autoworker-General Motors (UAW-GM) cohort of 38,549 automobile manufacturing workers with potential exposure to metalworking fluids, reported elevations in skin cancer mortality from long-term occupational exposure to metalworking fluids.63

MM

Evidence of occupational mineral oil exposure and melanoma has been reported relatively recently, mainly from retrospective cohort studies targeting workers in the US aviation or automobile industries. In a retrospective cohort study of workers employed at a California aerospace company between 1950 and 1993, high levels of exposure to mineral oils increased the incidence of melanoma (rate ratio, 3.32; 95% CI, 1.20–9.24).64 Similarly, in a cohort of autoworkers followed from 1985 through 2004 for cancer incidence,60 the hazard ratio for the highest category of straight fluid was 1.99 (95% CI, 1.00–3.96), based on 14,139 white male participants with 76 incident cases of MM. These findings indicate that oil-based fluids, especially straight mineral oils, are associated with a higher risk of MM, based on quantitative measurements of the metalworking fluid.

Summary of evidences

Mineral oils, including metalworking fluids, contain PAHs and are prone to carcinogenicity when left untreated or mildly treated. Sufficient evidence has been reported in humans for SCC of the skin, especially scrotal cancer, since the mid-1900s. In contrast, there have been few studies on the risk of melanoma, but several recent retrospective cohort studies have reported an increased risk of melanoma in workers exposed to mineral oil.

Petroleum refining

The petroleum industry is significant in many countries and contributes to the production of various chemicals. However, petroleum refining workers face potential health hazards, including the risk of developing skin cancer. Occupational exposure in petroleum refining has been classified as Group 1 by the IARC, with limited evidence for MM and NMSC.65,66

NMSC

Regarding the relationship between petroleum refining and NMSC, few studies have primarily consisted of case reports and series. Davis67 reported the case of a refinery worker who was diagnosed with SCC after removing paraffin wax for over 20 years. Subsequent investigations at the plant revealed that many workers suffered from wax boils that developed into pigmented spots, wart-like growth, and epithelioma. Lione and Denholm68 reviewed ten cases of scrotal cancer in wax pressmen in petroleum refineries. All patients were pathologically confirmed to have SCC. The workers had a minimum exposure period of 15 years to crude wax containing 20–40% petroleum oil distillate, with the longest exposure period lasting 38 years.

MM

Several cohort studies have documented the relationship between petroleum refinement and risk of melanomas among Australian, U.S., and UK petroleum industry workers.69,70,71 In a systematic review, Schnatter et al.72 discovered that 10 of 17 studies indicated a higher incidence of melanoma among petroleum refinery workers (meta-RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.09–1.38), but the mortality rates were not statistically significant. A more recent systematic review also found an increased risk of melanoma (summary effect size, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.34–2.70) associated with working in the petroleum industry, whereas no such elevation was found within the subset related to refinery work.73 However, a meta-analysis of melanoma risk in industrial workers revealed increased mortality (summary SMR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.81–1.28) and incidence (summary SIR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11–1.36) in the oil/petroleum industry, implying amplified risks considering the healthy worker effect.58

The increased risk of melanoma in the petroleum industry highlights the need to identify specific carcinogens that workers are primarily exposed to via vapour inhalation and skin contact. Mehlman et al.74 reviewed the causal relationship between exposure to chemicals in oil refining and MM, and identified exposure to chemicals such as benzene, aromatic hydrocarbons, PCBs, and heavy oils as contributing factors to the development of melanoma in oil-refining workers. PAH, classified as carcinogens by the IARC, disrupt cell membrane function and have carcinogenic, mutagenic, and immunosuppressive effects. PCBs also show sufficient evidence of their carcinogenicity in human melanoma, as mentioned above.

Summary of evidences

While some studies have indicated statistically significant relationship between petroleum refining and NMSC, the evidence is mostly based on old ones. However, there is sufficient evidence for a relationship between petroleum refining and melanoma, and chemicals such as PAH and PCBs appear to contribute to the development of melanoma in oil-refining workers.

Firefighters

Firefighters are exposed to many occupational hazards, and are already categorized as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1) in volume 132 of the IARC Monographs (mesothelioma, bladder cancer).75 There is a positive association between firefighters and several cancers, including MM, as well as substances such as PAH and benzene to which firefighters are exposed to.

NMSC

In the case of NMSC, the results related to the risk of incidence were not consistent, and no studies with increased mortality were identified. In a meta-analysis in 2020, when the meta-RR of skin cancers combined was stratified into regions, statistically significant results were found in Australia, New Zealand, and Korea (RR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.27–1.58).76 A Swedish cohort study also reported a statistically significant increase in incidences of NMSC amongst firefighters (SIR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.20–1.80).77 When stratified by employment period, the risk of NMSC was significantly elevated in those with a working period of 10–19 years (SIR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.21–2.62) and 20–29 years (SIR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.09–2.17). However, the risk was insignificantly elevated among firefighters who worked for 30 years or more.

MM

According to meta-analyses published in recent years on firefighters, the incidence of melanoma has generally increased,78,79 but the mortality rate has not.76,78,79 However, in a Swedish cohort study, the risk of melanoma among firefighters was statistically insignificant, and there was no association between melanoma incidence and duration of employment.77

Notably, the overall incidence of melanoma has decreased in firefighters over time.77,80,81 For example, a decrease in the incidence of malignant skin melanoma was observed among Swedish firefighters was observed.77 This could be related to incomplete Swedish cancer registration and explained by the healthy worker effect, which can be attributed to a lower risk if individuals are over 70 years old or have worked for more than 30 years.82 In addition, the recent trend of increasing periodic health checkups and improvements in protective measures to prevent exposure to carcinogenic substances can affect the incidence of skin cancer in firefighters.79

Summary of evidences

Firefighters showed a higher incidence of MM than the control group. This may be the case due to the exposure of firefighters to several carcinogens occupationally, such as PCBs and PAHs; however, many other factors are also involved. Current evidence regarding NMSC remains unclear and controversial. To obtain a clear conclusion regarding the occupational skin cancer risk in firefighters, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the healthy worker effect, carcinogen exposure, and regional differences.

CONCLUSION

A substantial degree of research has been conducted on the influence of occupational factors on skin cancer. The results of this review suggest that there is sufficient epidemiological evidence to support the relationship between the increased risk of NMSC and occupational exposure to solar radiation, ultraviolet radiation, ionizing radiation, and mineral oils. Occupational exposure to pesticides and PCBs appears to provide sufficient epidemiological evidence for melanoma, and a higher risk of melanoma has been reported among workers in petroleum refining and firefighters. However, the association between skin cancer and occupational exposure to other organic solvents and arsenic remains unclear. In addition, other occupational factors have been documented to be related to skin cancer, including occupational exposure to shale oil83 and repetitive mechanical stress.84 However, these factors were not covered in this review due to the limited availability of fragmented evidence.

Future research on occupational risk factors should address the following questions to build upon the robust evidence. The incidence of skin cancer is high; however, except for MM, the mortality risk is low. Therefore, mortality is a poor proxy for the risk of treatable cancers and is not an optimal outcome measure in etiological studies.63 Moreover, in relation to high-risk occupations, the healthy worker survivor effect seems to be strong; therefore, it should be considered in the research design, analysis, and interpretation of results. Occupational risk factors often include simultaneous exposure to solar UV radiation, which is known to be the strongest risk factor, and it can be difficult to distinguish their effects. Some studies have addressed simultaneous exposure to UV radiation;19,36,38,47,54,85 however, a more mechanistic understanding of this is warranted.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022R1F1A1066498).

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability Statement: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current review.

- Conceptualization: Kang MY.

- Funding acquisition: Kang MY.

- Investigation: Lee YS, Gu H, Lee YH, Yang M, Kim H, Kwon O.

- Project administration: Kang MY.

- Supervision: Kang MY.

- Visualization: Lee YS.

- Writing - original draft: Lee YS, Gu H, Lee YH, Yang M, Kim H, Kwon O, Kang MY.

- Writing - review & editing: Kim YH, Kang MY.

References

- 1.Linares MA, Zakaria A, Nizran P. Skin cancer. Prim Care. 2015;42(4):645–659. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achatz MI, Coloma MC, de Albuquerque Cavalcanti Callegaro E. In: Oncodermatology. Abdalla CMZ, Sanches JA, Munhoz RR, Belfort FA, editors. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. Risk factors for skin cancer; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song HS, Ryou HC. Compensation for occupational skin diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(Suppl):S52–S58. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.S.S52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Meteorological Organization. Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2006, Report 50. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young AR. In: Biophysical and Physiological Effects of Solar Radiation on Human Skin. Giacomoni PU, Jori G, Hader DP, editors. Cambridge, UK: RSC Publishing; 2007. Chapter 1: Damage from acute vs chronic solar exposure. [Google Scholar]

- 6.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Solar and Ultraviolet Radiation. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 55. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. The Effect of Occupational Exposure to Solar Ultraviolet Radiation on Malignant Skin Melanoma and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin HR, Lee JY, Lee DW, Shin SO, Choi YS, Yoo SJ, et al. Primary facial skin cancer: clinical characteristics and surgical outcome in Chungbuk Province, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20(2):279–282. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loney T, Paulo MS, Modenese A, Gobba F, Tenkate T, Whiteman DC, et al. Global evidence on occupational sun exposure and keratinocyte cancers: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(2):208–218. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zink A, Tizek L, Schielein M, Böhner A, Biedermann T, Wildner M. Different outdoor professions have different risks - a cross-sectional study comparing non-melanoma skin cancer risk among farmers, gardeners and mountain guides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(10):1695–1701. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trakatelli M, Barkitzi K, Apap C, Majewski S, De Vries E EPIDERM group. Skin cancer risk in outdoor workers: a European multicenter case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(Suppl 3):5–11. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radespiel-Tröger M, Meyer M, Pfahlberg A, Lausen B, Uter W, Gefeller O. Outdoor work and skin cancer incidence: a registry-based study in Bavaria. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009;82(3):357–363. doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassel JC, Enk AH. In: Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 9th ed. Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, Enk AH, Margolis DJ, McMichael AJ, et al., editors. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. Melanoma etiology and pathogenesis; pp. 1989–1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collatuzzo G, Boffetta P, Dika E, Visci G, Zunarelli C, Mastroeni S, et al. Occupational exposure to arsenic, mercury and UV radiation and risk of melanoma: a case-control study from Italy. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2023;96(3):443–449. doi: 10.1007/s00420-022-01935-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert ES. Ionising radiation and cancer risks: what have we learned from epidemiology? Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85(6):467–482. doi: 10.1080/09553000902883836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ron E, Modan B, Preston D, Alfandary E, Stovall M, Boice JD., Jr Radiation-induced skin carcinomas of the head and neck. Radiat Res. 1991;125(3):318–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shore RE, Albert RE, Reed M, Harley N, Pasternack BS. Skin cancer incidence among children irradiated for ringworm of the scalp. Radiat Res. 1984;100(1):192–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson DE, Mabuchi K, Ron E, Soda M, Tokunaga M, Ochikubo S, et al. Cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors. Part II: Solid tumors, 1958-1987. Radiat Res. 1994;137(2) Suppl:S17–S67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuperus E, Leguit R, Albregts M, Toonstra J. Post radiation skin tumors: basal cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas and angiosarcomas. A review of this late effect of radiotherapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(6):749–757. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennardo L, Passante M, Cameli N, Cristaudo A, Patruno C, Nisticò SP, et al. Skin manifestations after ionizing radiation exposure: a systematic review. Bioengineering (Basel) 2021;8(11):153. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering8110153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azizova TV, Bannikova MV, Grigoryeva ES, Rybkina VL. Risk of malignant skin neoplasms in a cohort of workers occupationally exposed to ionizing radiation at low dose rates. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0205060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azizova TV, Bannikova MV, Grigoryeva ES, Rybkina VL. Risk of skin cancer by histological type in a cohort of workers chronically exposed to ionizing radiation. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2021;60(1):9–22. doi: 10.1007/s00411-020-00883-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshinaga S, Hauptmann M, Sigurdson AJ, Doody MM, Freedman DM, Alexander BH, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in relation to ionizing radiation exposure among U.S. radiologic technologists. Int J Cancer. 2005;115(5):828–834. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee T, Sigurdson AJ, Preston DL, Cahoon EK, Freedman DM, Simon SL, et al. Occupational ionising radiation and risk of basal cell carcinoma in US radiologic technologists (1983-2005) Occup Environ Med. 2015;72(12):862–869. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-102880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fink CA, Bates MN. Melanoma and ionizing radiation: is there a causal relationship? Radiat Res. 2005;164(5):701–710. doi: 10.1667/rr3447.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freedman DM, Sigurdson A, Rao RS, Hauptmann M, Alexander B, Mohan A, et al. Risk of melanoma among radiologic technologists in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2003;103(4):556–562. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gawkrodger DJ. Occupational skin cancers. Occup Med (Lond) 2004;54(7):458–463. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, Kornak J, Kainz W, Posch C, et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(1):51–58. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez-Castillo M, García-Montalvo EA, Arellano-Mendoza MG, Sánchez-Peña LD, Soria Jasso LE, Izquierdo-Vega JA, et al. Arsenic exposure and non-carcinogenic health effects. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40(12_suppl):S826–S850. doi: 10.1177/09603271211045955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung JY, Yu SD, Hong YS. Environmental source of arsenic exposure. J Prev Med Public Health. 2014;47(5):253–257. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.14.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt KM, Srivastava RK, Elmets CA, Athar M. The mechanistic basis of arsenicosis: pathogenesis of skin cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;354(2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Arsenic, Metals, Fibres and Dusts. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2012. Arsenic and arsenic compounds. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu HS, Liao WT, Chai CY. Arsenic carcinogenesis in the skin. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13(5):657–666. doi: 10.1007/s11373-006-9092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith AH, Goycolea M, Haque R, Biggs ML. Marked increase in bladder and lung cancer mortality in a region of Northern Chile due to arsenic in drinking water. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(7):660–669. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim TH, Seo JW, Hong YS, Song KH. Case-control study of chronic low-level exposure of inorganic arsenic species and non-melanoma skin cancer. J Dermatol. 2017;44(12):1374–1379. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Surdu S, Fitzgerald EF, Bloom MS, Boscoe FP, Carpenter DO, Haase RF, et al. Occupational exposure to arsenic and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer in a multinational European study. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(9):2182–2191. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karagas MR, Stukel TA, Morris JS, Tosteson TD, Weiss JE, Spencer SK, et al. Skin cancer risk in relation to toenail arsenic concentrations in a US population-based case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(6):559–565. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.6.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dennis LK, Lynch CF, Sandler DP, Alavanja MC. Pesticide use and cutaneous melanoma in pesticide applicators in the agricultural heath study. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(6):812–817. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bedaiwi A, Wysong A, Rogan EG, Clarey D, Arcari CM. Arsenic exposure and melanoma among US adults aged 20 or older, 2003-2016. Public Health Rep. 2022;137(3):548–556. doi: 10.1177/00333549211008886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langston ME, Brown HE, Lynch CF, Roe DJ, Dennis LK. Ambient UVR and environmental arsenic exposure in relation to cutaneous melanoma in Iowa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1742. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim KH, Kabir E, Jahan SA. Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Sci Total Environ. 2017;575:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Occupational exposures in insecticide application, and some pesticides. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 16-23 October 1990. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1991;53:5–586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) List of classifications by cancer sites with sufficient or limited evidence in humans, IARC Monographs Volumes 1-135. [Accessed January 30, 2024]. https://monographs.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Classifications_by_cancer_site.pdf .

- 44.Frost G, Brown T, Harding AH. Mortality and cancer incidence among British agricultural pesticide users. Occup Med (Lond) 2011;61(5):303–310. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stanganelli I, De Felici MB, Mandel VD, Caini S, Raimondi S, Corso F, et al. The association between pesticide use and cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(4):691–708. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varghese JV, Sebastian EM, Iqbal T, Tom AA. Pesticide applicators and cancer: a systematic review. Rev Environ Health. 2020;36(4):467–476. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2020-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Graaf L, Boulanger M, Bureau M, Bouvier G, Meryet-Figuiere M, Tual S, et al. Occupational pesticide exposure, cancer and chronic neurological disorders: a systematic review of epidemiological studies in greenspace workers. Environ Res. 2022;203:111822. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cavalier H, Trasande L, Porta M. Exposures to pesticides and risk of cancer: evaluation of recent epidemiological evidence in humans and paths forward. Int J Cancer. 2023;152(5):879–912. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Togawa K, Leon ME, Lebailly P, Beane Freeman LE, Nordby KC, Baldi I, et al. Cancer incidence in agricultural workers: findings from an International Consortium of Agricultural Cohort Studies (AGRICOH) Environ Int. 2021;157:106825. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joshi DR, Adhikari N. An overview on common organic solvents and their toxicity. J Pharm Res Int. 2019;28(3):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lynge E, Anttila A, Hemminki K. Organic solvents and cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8(3):406–419. doi: 10.1023/a:1018461406120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated biphenyls. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2016;107:9–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Institute of Medicine. Gulf War and Health: Volume 2: Insecticides and Solvents. Washington, D.C., USA: The National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zani C, Ceretti E, Covolo L, Donato F. Do polychlorinated biphenyls cause cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies on risk of cutaneous melanoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Chemosphere. 2017;183:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boffetta P, Catalani S, Tomasi C, Pira E, Apostoli P. Occupational exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and risk of cutaneous melanoma: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2018;27(1):62–69. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fritschi L, Siemiatycki J. Melanoma and occupation: results of a case-control study. Occup Environ Med. 1996;53(3):168–173. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.3.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Christensen KY, Vizcaya D, Richardson H, Lavoué J, Aronson K, Siemiatycki J. Risk of selected cancers due to occupational exposure to chlorinated solvents in a case-control study in Montreal. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(2):198–208. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182728eab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vujic I, Gandini S, Stanganelli I, Fierro MT, Rappersberger K, Sibilia M, et al. A meta-analysis of melanoma risk in industrial workers. Melanoma Res. 2020;30(3):286–296. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Chemical agents and related occupations. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100(Pt F):9–562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Costello S, Friesen MC, Christiani DC, Eisen EA. Metalworking fluids and malignant melanoma in autoworkers. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):90–97. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fce4b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, Part 2, Carbon blacks, mineral oils (lubricant base oils and derived products) and some nitroarenes. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risk Chem Hum. 1984;33:1–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. What You Need to Know about Occupational Exposure to Metalworking Fluids. Washington, D.C., USA: Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costello S, Chen K, Picciotto S, Lutzker L, Eisen E. Metalworking fluids and cancer mortality in a US autoworker cohort (1941-2015) Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(5):525–532. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao Y, Krishnadasan A, Kennedy N, Morgenstern H, Ritz B. Estimated effects of solvents and mineral oils on cancer incidence and mortality in a cohort of aerospace workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(4):249–258. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Occupational exposures in petroleum refining; crude oil and major petroleum fuels. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1989;45:1–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee WJ, Lewis SJ, Chen YY, Wang YF, Sheu HL, Su CC, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls in the ambient air of petroleum refinery, urban and rural areas. Atmos Environ. 1996;30(13):2371–2378. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davis BF. Paraffin cancer: CCAL and petroleum products as cause of chronic irritation and cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 1914;62(22):1716–1720. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lione JG, Denholm JS. Cancer of the scrotum in wax pressmen. II. Clinical observations. AMA Arch Ind Health. 1959;19(5):530–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gun RT, Pratt N, Ryan P, Roder D. Update of mortality and cancer incidence in the Australian petroleum industry cohort. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(7):476–481. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.023796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wojcik NC, Gallagher EM, Alexander MS, Lewis RJ. Mortality of 196,826 men and women working in U.S.-based petrochemical and refinery operations: update 1979 to 2010. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64(3):250–262. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sorahan T. Mortality of UK oil refinery and petroleum distribution workers, 1951-2003. Occup Med (Lond) 2007;57(3):177–185. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kql168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schnatter AR, Chen M, DeVilbiss EA, Lewis RJ, Gallagher EM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of selected cancers in petroleum refinery workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(7):e329–e342. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Onyije FM, Hosseini B, Togawa K, Schüz J, Olsson A. Cancer incidence and mortality among petroleum industry workers and residents living in oil producing communities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4343. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mehlman MA. Causal relationship from exposure to chemicals in oil refining and chemical industries and malignant melanoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1076(1):822–828. doi: 10.1196/annals.1371.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.IARC Working Group on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. Occupational Exposure as a Firefighter. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Casjens S, Brüning T, Taeger D. Cancer risks of firefighters: a systematic review and meta-analysis of secular trends and region-specific differences. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020;93(7):839–852. doi: 10.1007/s00420-020-01539-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bigert C, Martinsen JI, Gustavsson P, Sparén P. Cancer incidence among Swedish firefighters: an extended follow-up of the NOCCA study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020;93(2):197–204. doi: 10.1007/s00420-019-01472-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee DJ, Ahn S, McClure LA, Caban-Martinez AJ, Kobetz EN, Ukani H, et al. Cancer risk and mortality among firefighters: a meta-analytic review. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1130754. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1130754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jalilian H, Ziaei M, Weiderpass E, Rueegg CS, Khosravi Y, Kjaerheim K. Cancer incidence and mortality among firefighters. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(10):2639–2646. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pukkala E, Martinsen JI, Weiderpass E, Kjaerheim K, Lynge E, Tryggvadottir L, et al. Cancer incidence among firefighters: 45 years of follow-up in five Nordic countries. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(6):398–404. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-101803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kullberg C, Andersson T, Gustavsson P, Selander J, Tornling G, Gustavsson A, et al. Cancer incidence in Stockholm firefighters 1958-2012: an updated cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018;91(3):285–291. doi: 10.1007/s00420-017-1276-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sidossis A, Lan FY, Hershey MS, Hadkhale K, Kales SN. Cancer and potential prevention with lifestyle among career firefighters: a narrative review. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15(9):2442. doi: 10.3390/cancers15092442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miller BG, Cowie HA, Middleton WG, Seaton A. Epidemiologic studies of Scottish oil shale workers: III. Causes of death. Am J Ind Med. 1986;9(5):433–446. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700090505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Costello CM, Pittelkow MR, Mangold AR. Acral melanoma and mechanical stress on the plantar surface of the foot. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):395–396. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1706162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Segatto M M, Hohmann C, Miligi L, Bakos L, et al. Occupational exposure to pesticides with occupational sun exposure increases the risk for cutaneous melanoma. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(4):370–375. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]