Abstract

The connection between SARS-CoV-2 replication–transcription complexes and nucleocapsid (N) protein is critical for regulating genomic RNA replication and virion packaging over the viral life cycle. However, the mechanism that dynamically regulates genomic RNA packaging and replication remains elusive. Here, we demonstrate that the N-terminal domain of SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 3, a core component of viral replication–transcription complexes, binds N protein and displaces RNA in a concentration-dependent manner. This interaction disrupts liquid–liquid phase separation of N protein driven by N protein–RNA interactions which is crucial for virion packaging and viral replication. We also report a high-resolution crystal structure of the nonstructural protein 3 ubiquitin-like domain 1 (Ubl1) at 1.49 Å, which reveals abundant negative charges on the protein surface. Sequence and structural analyses identify several conserved motifs at the Ubl1–N protein interface and a previously unexplored highly negative groove, providing insights into the molecular mechanism of Ubl1-mediated modulation of N protein–RNA binding. Our findings elucidate the mechanism of dynamic regulation of SARS-CoV-2 genomic RNA replication and packaging over the viral life cycle. Targeting the conserved Ubl1–N protein interaction hotspots also promises to aid in the development of broad-spectrum antivirals against pathogenic coronaviruses.

Keywords: nonstructural protein 3, nucleocapsid protein, SARS-CoV-2, phase separation, ubiquitin-like domain

For over 3 years, SARS-CoV-2 has inflicted devastating impacts across the globe, causing over 770 million confirmed infections and over 6 million deaths as of September 2023 (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update---29-september-2023). SARS-CoV-2 is classified under the betacoronavirus genus and contains a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 30,000 nucleotides. This viral genome encodes two polyproteins that are proteolytically processed into 16 nonstructural proteins (Nsps) as well as four structural and several auxiliary proteins (1). The 16 Nsps assemble into replication–transcription complexes (RTCs) that drive viral genome replication, evasion of host immunity, and maturation of viral proteins (2, 3, 4). The four structural proteins, including the spike, membrane, envelope, and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, comprise the viral particle (3). Among them, the N protein plays indispensable roles in assembling the genomic RNA into ribonucleoprotein complexes and mediating their packaging into virions through poorly defined interactions with membrane protein (5, 6).

The N protein contains two conserved domains—the N-terminal domain (NTD) and C-terminal domain (CTD)—interconnected by three intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) (7). Extensive contacts exist between both the NTD and CTD with viral genomic RNA or nonspecific RNAs, with or without cooperating with the IDRs, facilitating viral ribonucleoprotein packaging (8). Substantial evidence indicates that the N protein undergoes weak liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) in vivo and in vitro, dramatically enhanced by binding to genomic or nonspecific RNAs (9, 10, 11, 12, 13). Such RNA-driven LLPS concentrates N proteins and nucleic acids locally to strongly promote protein–nucleic acid interactions (14, 15), potentially creating an optimal environment for genome packaging. At early infection stages, N protein associated with RTCs also facilitates genomic RNA synthesis and translation by recruiting host cellular machinery and enabling template switching (16, 17, 18).

Nsp3 is the largest coronavirus protein, containing 16 or more domains, each of which plays critical roles in viral replication (19). The amino terminus of Nsp3 encompasses the ubiquitin-like domain 1 (Ubl1) and a hypervariable region (HVR) enriched in glutamic acid residues, collectively termed Nsp3a. In mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), Nsp3a interacts with the N protein to facilitate localization of genomic RNA to viral RTCs, an obligatory early step for replication (20, 21, 22). Likewise, NMR studies revealed conformational changes in the SARS-CoV-2 N protein when bound to Nsp3 (23). However, the specific mechanisms underlying Nsp3a–N protein cooperation during SARS-CoV-2 infection remain poorly understood.

In this study, we use high-resolution structural and biochemical analyses to elucidate the functional mechanisms and structural basis governing the interaction between Nsp3 and the SARS-CoV-2 N protein, unraveling a putative mechanism of Nsp3-mediated modulation of N protein–RNA binding over the viral life cycle. This work also provides molecular insights into key SARS-CoV-2 protein–protein interactions and their coordinated regulation of distinct viral processes like genome packaging and replication. Furthermore, our sequence and structure analysis identified potential broad-spectrum antiviral targets at conserved Nsp3–N protein interaction hotspots among pathogenic coronaviruses.

Results

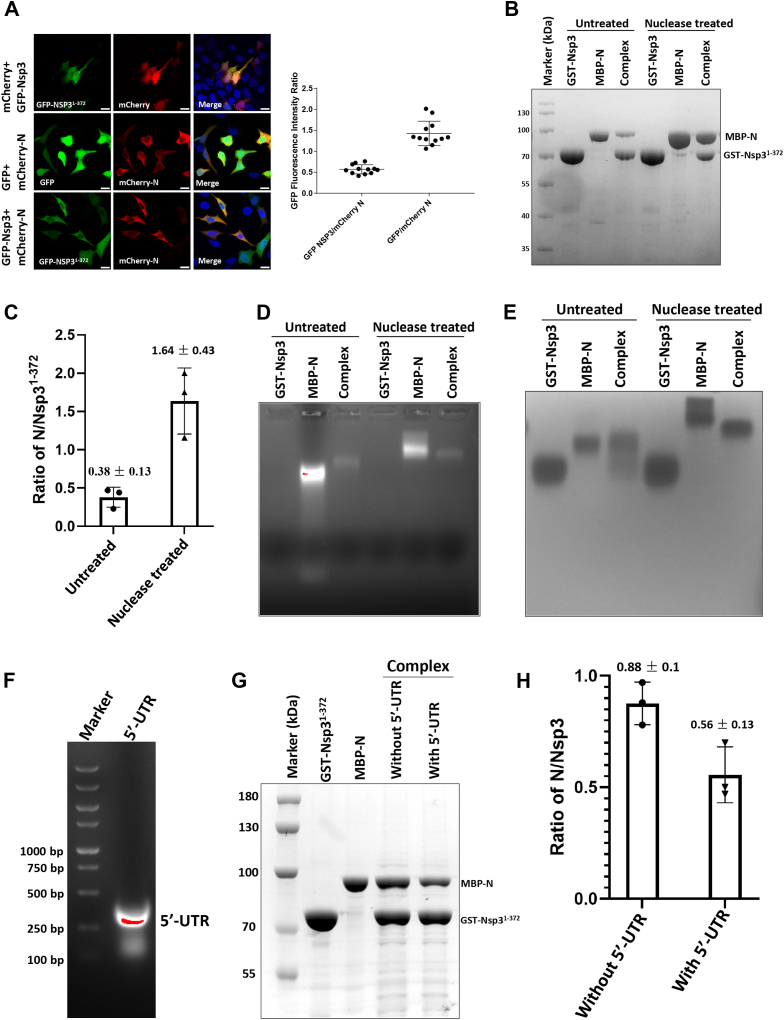

RNA negatively influences the interaction of Nsp3 with N protein

The N terminus of Nsp3 is essential for the interaction between RTCs and N protein (20, 21). Hence, we first detected the interaction of Nsp3 (residues 1–372), including the Ubl1, HVR, PL1pro, and Mac1 domains, with N protein of SARS-CoV-2 by colocalization assays in HEK293 T cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, when expressed alone, Nsp31-372 was distributed in both cell nucleus and cytoplasm, while N protein was located in cytoplasm only. When the two proteins were co-expressed in cells, Nsp31-372 was relocalized from cell nucleus to cytoplasm, confirming the interaction between Nsp31-372 and N protein.

Figure 1.

RNA negatively influences the interaction of the N-terminal region of Nsp3 with N protein.A, colocalization of Nsp31-372 with N protein in HEK293 T cells. Cells were transfected with pCDNA3.1-EGFP-Nsp31-372 and pCDNA3.1-mCherry-N plasmids, respectively, or cotransfected pairwise, using Lipofectamine 2000. Plasmids pCDNA3.1-EGFP and pCDNA3.1-mCherry were used as control groups and performed with the same approach. After 48 h posttransfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 buffer. Then, cells were stained with DAPI to show the cell nucleus. Pictures were subsequently taken with an Olympus Spin co-focus fluorescence microscope (Olympus Life Science). Scale bar, 10 μm. Two replicates were performed for this assay. B, GST pull-down assays of Nsp31-372 with N protein in the absence or presence of nuclease. Cells containing GST-Nsp31-372 and MBP-N were mixed at 1:1 ratio and homogenized by sonication. Supernatants were divided equally into two parts. Both parts were incubated with 50 μl glutathione beads in the absence or presence of nuclease, respectively. After washing five times, proteins were eluted with 100 μl elution buffer. All the samples were analyzed using SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. C, the ratio of N protein to Nsp3 in the complex. The gray levels of the bands in lane “complex” from panel B were calculated with software ImageJ. The ratios N/Nsp3 were calculated and statistically analyzed in GraphPad Prism 10 using paired t test (p = 0.02). D, RNA detection for the proteins after GST pull-down using native agarose gel electrophoresis. Samples from GST pull-down assays were treated with SDS-free loading buffer and carried out electrophoresis in a 0.8% native agarose gel containing 1‱ nucleic acid dye. Three replicates at least were performed for the assay. E, detecting complexes of Nsp31-372 with N protein using native agarose gel electrophoresis stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. F, confirmation of 5′-UTR of SARS-CoV-2 genome synthesize in vitro by agarose gel electrophoresis. G and H, influence of 5′-UTR on the interaction of GST-Nsp31-372 with N protein. GST pull-down assays were performed as described above. 20 μl 5′-UTR (120 μM) was incubated with the beads for 20 min before elution of the complexes from beads during GST pull-down assays. All the samples were analyzed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R250 after SDS-PAGE. The gray levels of the bands in lane “Complex” or “Complexes + 5′-UTR” from panel G were calculated with software ImageJ. The ratios N/Nsp3 were calculated and statistically analyzed in GraphPad Prism 10 using paired t test (p < 0.01). Nsp, nonstructural protein; N, nucleocapsid; Ubl1, ubiquitin-like domain 1.

To further characterize the interaction between the Nsp31-372 and N proteins in vitro, GST pull-down assays were utilized to monitor binding, with or without pretreatment of the proteins with a nuclease to eliminate nucleic acids. Analysis by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining revealed robust co-elution of MBP-N protein with GST-Nsp31-372 regardless of nuclease treatment (Fig. 1B), indicating a strong interaction. However, the relative quantities of MBP-N protein compared to GST-Nsp31-372 in the pull-down complexes were greater when treated with nuclease, suggesting that nucleic acids might negatively influence the interaction (Fig. 1, B and C). To test this, samples from the pull-downs were analyzed by native agarose gel electrophoresis with SDS-free loading buffer and staining with a nucleic acid dye. As previously reported, N protein purified from Escherichia coli contains copurifying RNA (Fig. 1D) (24). Strikingly, we found that bound RNA levels were substantially reduced when N protein was combined with Nsp31-372, to an even greater extent than digestion with nuclease (Fig. 1D). Additionally, when we stained the agarose gel derived from Fig. 1D with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB), Nsp31-372 and N protein migrated as a diffuse complex without nuclease treatment but a tight single band following digestion (Fig. 1E). This might be the reason that nonspecific binding of RNA generated multiple aggregative formations or charges of N proteins which resulted in the discrete location in the native gel. To further explore the influence of RNA on the interaction of N protein with Nsp3, we in vitro transcribed 5′-UTR of SARS-CoV-2 genome (Fig. 1F). In the GST pull-down assays for Nsp31-372 and N proteins, the glutathione beads bound with their complex were incubated with or without 5′-UTR. After washing, the complexes were eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and CBB-staining. Results showed that the ratio of MBP-N compared to GST-Nsp31-372 significantly declined after treatment with 5′-UTR (Fig. 1, G and H). Together, these results demonstrate that RNA binding to N protein negatively impacts its interaction with the N-terminal region of Nsp3.

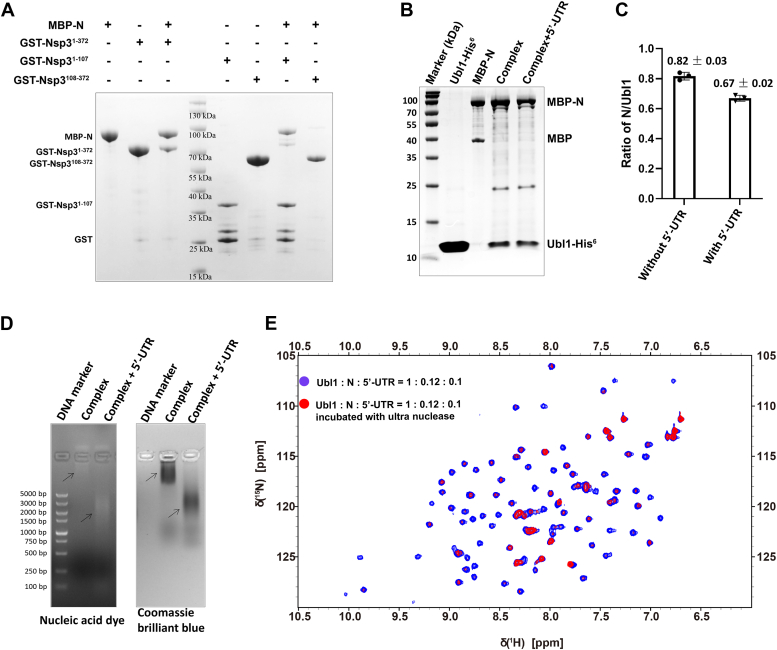

Ubl1 domain played the critical role in the interaction between Nsp3 and N protein, as well as the competition against RNA

The Ubl1 domain is located at the extreme amino terminus of Nsp3. Previous studies revealed that Ubl1 connected with N protein (20, 21). In this study, GST pull-down assays verified that MBP-N protein co-eluted with GST-Ubl1 (residues 1–107), but not with the HVR, PL1pro, and Mac1 domains (residues 108–372), revealing a robust affinity of Ubl1 with N protein (Fig. 2A). We then explored whether 5′-UTR of SARS-CoV-2 genome influence on their interactions by His6-pull-down assays in the presence or absence of 5′-UTR. The results showed that the relative quantities of MBP-N co-eluted with Ubl1-His6 declined in the elution in the presence of 5′-UTR, revealing a negative influence of 5′-UTR on the interactions (Fig. 2, B and C). The complexes with or without 5′-UTR treatment were analyzed by native agarose gel electrophoresis. RNAs and proteins were stained with nucleic acid dye and Coomassie brilliant blue R250, respectively. Results showed that complexes with 5′-UTR treatment migrated faster than that without 5′-UTR treatment in the native gel, indicating that 5′-UTR might alter charges or aggregation conformations of the complexes (Fig. 2D). In addition, we conducted NMR titration assays to investigate whether RNA binding to the N protein interferes with the N–Ubl1 interaction. In a system containing 24 μM unlabeled N protein and 20 μM unlabeled 5′-UTR RNA, the peak intensities in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 200 μM 15N-labeled Ubl1 significantly decreased 30 min after adding ultra nuclease (Fig. 2E). However, in a control system with only 200 μM 15N-labeled Ubl1 and 20 μM unlabeled 5′-UTR RNA, no significant changes in peak intensities were observed after the same treatment (Fig. S1). This indicates that RNA degradation restores the N–Ubl1 interaction, characterized by intermediate exchange at nearly micromolar binding affinity. In summary, Ubl1 was the dominant domain of Nsp3 to interact with N protein, and this interaction was competed against the interaction of RNA with N protein.

Figure 2.

Ubl1 domain played the critical role in the interaction between Nsp3 and N protein, as well as the competition against RNA.A, interaction of Ubl1 and the rest part of Nsp31-372 with N protein confirmed by GST pull-down assays. All the samples were analyzed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R250 after SDS-PAGE. Nsp31-1-07 and Nsp3108-372 referred to the Ubl1 and the rest part, respectively. Two replicates for this assay were performed. B and C, influence of 5′-UTR on the interaction of Ubl1 with N protein. Purified Ubl1-His6 was mixed with the cell suspensions containing MBP-N in the presence of nuclease and homogenized with sonication. Supernatants were incubated with 50 μl NI-NTA beads for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing for 6 times, the beads were incubated with 20 μl 5′-UTR (120 μM) for 20 min. Then, the beads were washing for three times and eluted with 100 μl elution buffer. Samples were analyzed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R250 after SDS-PAGE. The gray levels of the bands in lane “Complex” or “Complex + 5′-UTR” from panel B were calculated with software ImageJ. The ratios N/Ubl1 were calculated and statistically analyzed in GraphPad Prism 10 using paired t test (p = 0.02). D, detection of RNAs and proteins in the Ubl1–N complexes derived from His6-pull-down assays. The complexes were treated with SDS-free loading buffer and carried out electrophoresis in a 0.8% native agarose gel containing 1‱ nucleic acid dye. RNAs were detected under UV light. Then, the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. E, influence of 5′-UTR on the interaction of Ubl1 with N protein, observed through overlaid 1H-15 N HSQC NMR spectra for 15N-labeled Ubl1 in the presence of both N protein and 5′-UTR before (blue) and after (red) ultra nuclease treatment. Nsp, nonstructural protein; N, nucleocapsid; Ubl1, ubiquitin-like domain 1.

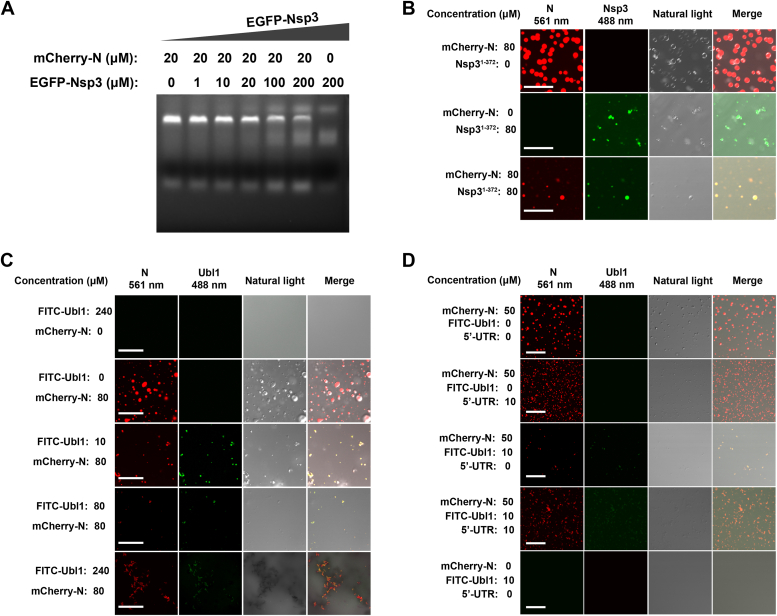

Nsp3 interrupts RNA-driven phase separation of N protein by dislodging RNA from N protein

Having confirmed that RNA negatively regulates Nsp3–N protein interactions, we conversely hypothesized that Nsp3 may directly compete with RNA for N protein binding and be competent to dislodge RNA from N protein. To testify this, N protein complexed with numerous nonspecific RNA were incubated with Nsp31-372 at a series of concentration. Indeed, agarose gel electrophoresis assays demonstrated that increasing concentrations of Nsp31-372 progressively reduced the amount of RNA copurifying with N protein (Fig. 3A). These data strongly support a model whereby Nsp31-372 displaces RNA from the N protein. Previous studies solidly confirmed that N protein generates LLPS, and this phenomenon is greatly enhanced in the presence of virus genomic RNA or some nonspecified RNA (9, 10, 11, 12, 13). Therefore, we next explored whether Nsp31-372could attenuate the LLPS of N protein. Purified mCherry-tagged N protein, carrying nonspecified RNA, was incubated at 80 μM, with or without EGFP-Nsp31-372. Strikingly, while N protein robustly underwent LLPS, addition of equimolar Nsp31-372 dramatically reduced both the size and number of N condensates which represented the attenuation of LLPS (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Nsp3 interrupts RNA-driven phase separation of N protein by dislodging RNA from N protein.A, Nsp3 dislodges RNA from N protein in a concentration-dependent manner. Purified Nsp31-372 and N protein bound with nonspecific RNA were mixed as indicated concentration and incubated at 4 °C for 20 min. All the mixtures were treated with SDS-free DNA loading buffer and subjected to electrophoresis in a 0.8% native agarose gel containing 1‱ nucleic acid dye. RNAs were detected under UV light. Two replicates of this assay were performed. B and C, Nsp31-372 and Ubl1 restrained RNA-driven LLPS in a concentration-dependent manner. Purified mCherry-N was mixed with EGFP- Nsp31-372 or FITC-stained Ubl1 as indicated concentration. 10% PEG6000 was used to initiate LLPS. The droplets were imaged on the Olympus FV3000 laser scanning confocal system and analyzed by the Olympus cellSens software. Scale bar, 20 μm. Three replicates at least for this assay were performed. D, the restraint of LLPS by Nsp3 was able to be converted by 5′-UTR. mCherry-N was mixed with FITC-stained Ubl1 and 5′-UTR as indicated concentration and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. 10% PEG6000 was used to initiate LLPS. The droplets were imaged on the Olympus FV3000 laser scanning confocal system and analyzed by the Olympus cellSens software. Scale bar, 20 μm. Two replicates of the assay were performed. LLPS, liquid–liquid phase separation; N, nucleocapsid; Nsp, nonstructural protein; Ubl1, ubiquitin-like domain 1.

We then directly examined the effects of Ubl1 on the RNA-driven phase separation process of N protein by using FITC-stained Ubl1 and mCherry-tagged N proteins to perform LLPS analysis. As described above, mCherry-N proteins underwent robust LLPS phenomenon at the concentration of 80 μM (Fig. 3C). However, when mixed with 10 μM -Ubl1, the LLPS particles formed by the mCherry-N protein were visibly reduced in amount and diminished in sizes (Fig. 3C). The LLPS particles reduced at a much greater degree when mCherry-N protein was mixed with an equimolar concentration of Ubl1 (80 μM) (Fig. 3C). When we further increased the concentration of Ubl1 to 240 μM, the mCherry-N protein then turned into amorphous agglutinates, which might reflect that the solubility of N protein was reduced and tended to amorphously aggregate at this concentration when its bound RNA was dislodged by overloaded Ubl1 (Fig. 3C). Next, we tested whether the attenuation of LLPS of N protein was able to be reversed by adding 5′-UTR of SARS-CoV-2 genome. 50 μM N protein carried nonspecific RNA were incubated with 10 μM Ubl1 in the presence or absence of 10 μM 5′-UTR and performed LLPS analysis. As described above, the condensates of N protein was strongly restrained by Ulb1 but strikingly increased in the presence of 5′-UTR (Fig. 3D).Together, these results demonstrate that Nsp3 interrupts RNA-driven phase separation of the N protein by competitively displacing RNA in a concentration-dependent manner, and this restraint could be relieved by specific RNA.

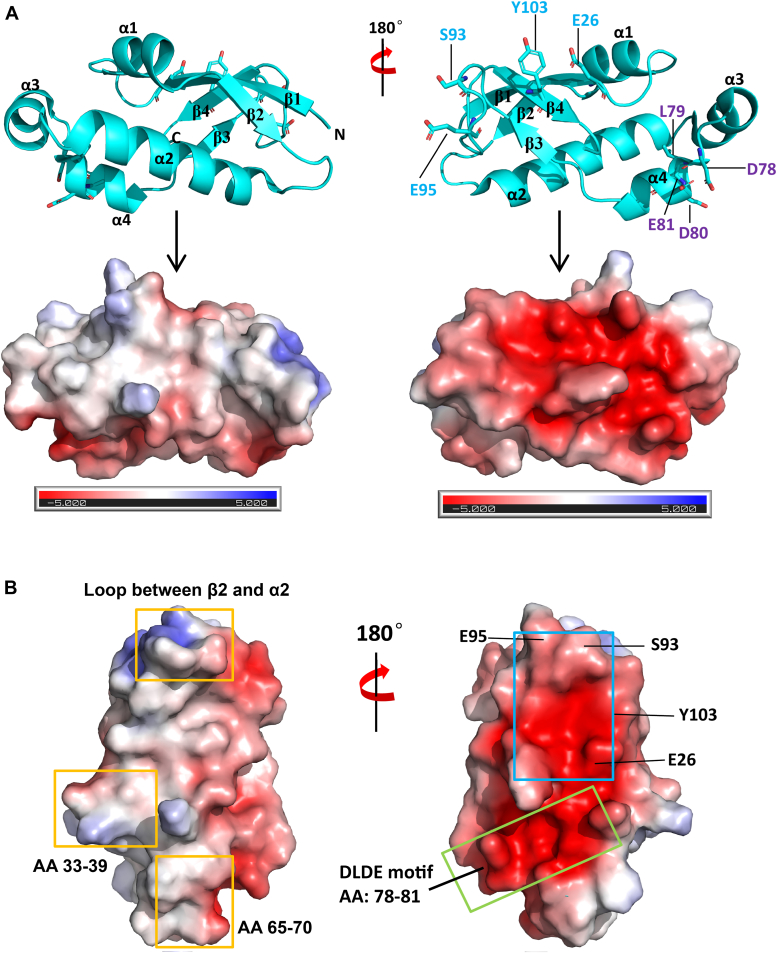

The structural basis of the interaction of Ubl1 with N protein

To elucidate the structural basis underlying the interaction between Ubl1 and N protein, we attempted to solve the crystal structure of the Ubl1–N complex but were unsuccessful. However, we obtained a high-resolution crystal structure of truncated Ubl1 (residues 18–107) in a free state at 1.49 Å (Fig. 4A, Table 1). Our structure captured Ubl1 with residues 1 to 17 absent in a monomeric state (Fig. 4A), consistent with the previous finding that the N-terminal region of Ubl1 is responsible for dimerization which is critical for stable interaction with N protein (25). The overall structure of Ubl118-107 consists of four α-helices and four β-strands arranged sequentially in the β1-α1-β2-α2-α3-α4-β3-β4 manner, with a solvent-exposed surface enriched in negative charges (Fig. 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

Structural basis of the interaction between Ubl1 and N protein.A, crystal structure of Ubl1 without residues 1 to 17 and the demonstration of electric charges. The surface charges were generated with APBS tools. Negative and positive charges were highlighted with red and blue colors, respectively. B, demonstration in our Ubl1 structure of the interfaces or key residues that interact with NTD or IDR2 of N protein. Regions that interacted with IDR2 and NTD of N protein were circled with yellow and blue boxes, respectively. An unexplored interface was circled with green box. IDR, intrinsically disordered regions; N, nucleocapsid; NTD, N-terminal domain; Ubl1, ubiquitin-like domain 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| X-ray wavelength (Å) | 0.97918 |

| Space group | P21 21 2 |

| Cell parameters a, b, c (Å) | 49.96 Å, 98.31 Å, 27.90 Å |

| 90.00° 90.00° 90.00° | |

| Resolution (Å) | 44.536–1.490 (1.53–1.49) |

| Unique reflections | 22,740 (1615) |

| Rmerge | 0.096 (1.703) |

| Rmeas | 0.100 (1.789) |

| CC1/2 | 0.998 (0.731) |

| < I/σ(I) > | 14.0 (2.300) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.9 (96.00) |

| Redundancy | 12.5 (10.8) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 44.510–1.489 |

| No. reflections | 22659 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.2098/0.2335 |

| Number of atoms | |

| Protein | 767 |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 20.7 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.777 |

The extensive negative charges on Ubl1 surface (Fig. 4B) suggests a mechanism where Ubl1 competes with RNA for binding to N protein, likely via charge-based interactions. Additionally, an NMR study by Bessa et al. revealed that residues 65 to 70, 33 to 39, and the loop between β2 and α2 of Ubl1 are involved in interacting with the IDR2 of the N protein in the presence of NTD and CTD (23). In our structure model, we highlighted these regions with yellow boxes (Fig. 4B). The interface connecting Ubl1 and NTD of N protein reported previously (25) is also mapped onto our structure, highlighting key residues E26, S93, E95, and Y103 (Fig. 4B). Intriguingly, mapping the regions characterized in the above two independent studies onto our Ubl1 structure revealed an additional solvent-exposed acidic groove containing a conserved motif among three most pathogenic coronaviruses, namely SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV dominated by α4 with the sequence DLDE (aa 78–81) (green box, Fig. 4B). It is a tempting point which needs further investigation in future.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate that the NTD of SARS-CoV-2 Nsp3, a core component of viral RTCs, interacts with N protein and displaces its bound RNA in a concentration-dependent manner. This RNA displacement disrupts the LLPS of N protein driven by RNA binding, which is critical for virion packaging. Moreover, our high-resolution crystal structure of the Nsp3 Ubl1 domain reveals abundant negative charges on its surface. Sequence and structural analyses identify conserved motifs at the Ubl1–N protein interface, notably a previously unexplored, highly negatively charged groove. These findings provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the modulation of N protein–RNA interactions by Nsp3 over the viral life cycle. Further studies should investigate this proposed functional interaction between Nsp3 and N protein in physiologically relevant contexts.

The interaction between Nsp3 and N protein has been investigated previously in coronaviruses. For MHV, the Ubl1 domain of Nsp3 interacts with the SR-rich region of N protein, which facilitates viral infection (20, 21, 22). The N protein CTD also mediates recruitment to viral RTCs (26). These findings demonstrate the importance of Nsp3–N protein interplay for coronavirus replication. Moreover, disrupting this interaction inhibits MHV infection (18), validating its significance. For SARS-CoV-2, the Ubl1 domain binds N protein SR-rich regions (23) and the Ubl1–NTD fusion protein complex structure revealed key interface residues (25). Collectively, these studies establish extensive Ubl1 contacts with multiple N protein regions. However, the linkage between the nucleic acid binding of N protein and its interactions with Nsp3 had remained unclear. Our findings that Ubl1 displaces RNA from N protein and suppresses LLPS in a concentration-dependent manner suggest Ubl1 modulates RNA packaging through competition for N protein binding. Integrating our observations with prior characterizations of Ubl1–N protein interactions, these observations imply that the RNA displacement by Ubl1 underlies a putative mechanism of expropriation of N protein IDR2/NTD binding interface for RNA displacement or through unresolved, unoccupied pocket(s). By elucidating this mechanism, our study provides insights into the dynamic regulation of SARS-CoV-2 genome packaging and replication.

Our findings provide insights into the coordinated regulation of two key steps in the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle: genome packaging and replication. The extensive RNA binding capacity of N protein facilitates packaging the lengthy viral genome into virions (27). LLPS driven by N protein–RNA interactions likely promotes this encapsidation process (9, 10, 11, 12, 13). However, following cell entry, replication and expression of the genomic RNA take priority over packaging to produce sufficient viral components. RTCs of coronavirus assembled by Nsps take charge of the replication, maturation, and translation of gRNA, while also antagonizing host innate immunity (28, 29, 30). At early stages, genomic RNA needs to be redirected from encapsidation to viral RTCs for replication and to host ribosomes in endoplasmic reticulum for translation (28, 31, 32). Our discovery that Nsp3 disrupts N protein phase separation by displacing bound RNA supports a model where Nsp3 facilitates these initial processes by limiting RNA availability for virion assembly. As Nsp3 levels subsequently decline, RNA may become more accessible to promote phase separation and packaging of progeny genomes. By regulating RNA partitioning between N protein condensates and RTCs, Nsp3 may coordinate the timely switch from replication to packaging over the course of infection. Further examination of this proposed mechanism is warranted using physiologically relevant systems. Nonetheless, our integrated findings provide a framework for understanding the nuanced transitions between distinct SARS-CoV-2 processes throughout the viral life cycle.

With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and threats from other coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-NL63, broad-spectrum antiviral targets are urgently needed to be discovered (33). We performed sequence alignment analysis of Ubl1 domains across all seven coronaviruses and revealed two highly conserved and acid motifs consisted of acid residues interspersed with F or Y—F(Y)E(D)L(F)DI (motif 1) and YL(I)F(Y)DE(D) (motif 2)—except in MERS-CoV (Fig. S2A). Mapping these conserved motifs onto our Ubl1 crystal structure showed that motif 1 (FELD, aa 25–28, labeled in green) and motif 2 (YLFDE, aa 88–92, labeled in blue) in SARS-CoV-2 were located within the same highly negatively charged interface which contained the key residues E26, S93, E95, and Y103 that connected with NTD of N protein reported in previous studies (25). Strikingly, a third motif, DLDE(D), was exclusively conserved among the three most pathogenic coronaviruses, namely SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV (Fig. S2C), mapped to the same putative RNA competing surface on Ubl1 (Fig. S2B). Together, the presence of these sequence elements at functionally important regions of Ubl1, coupled with their conservation among virulent coronaviruses, renders them potential pan-coronaviral drug targets pending further validation. Compounds targeting these motifs could plausibly impair Ubl1's ability to modulate N protein–RNA interactions, viral genome encapsidation, and gRNA access to RTCs. However, evidence is still needed to confirm this proposed mode of action. Nonetheless, our study suggests that structure-guided targeting of key Ubl1 motifs could aid the future development of wide-spectrum coronavirus therapies.

Experimental procedures

Purification of Nsp3 and N protein

The DNA sequences encoding full-length N protein, Nsp3 residues 1 to 372, 1 to 107, 108 to 372, and 18 to 107 were cloned into plasmids pET-30a(+), pGEX-4T-1, and pMAL-c2x for expression of His6-tagged, GST-tagged, or MBP-tagged proteins, respectively. The DNA sequences encoding Nsp3 and N protein used were cloned into pET-30a(+) plasmid fused with EGFP or mCherry tags for phase separation assays. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. A single colony was inoculated into Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin or 100 μg/ml ampicillin and cultured at 37 °C until the absorbance at 600 nm (A600) reached 0.8. Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside at 25 °C for 16 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole). The suspension was homogenized using a high-pressure cell disruptor, and the supernatant was isolated by centrifugation at 25,000g for 30 min. The supernatants containing His6-tagged or fluorescent protein-tagged proteins were loaded onto a Ni-NTA column with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. After washing with buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 30 mM imidazole), proteins were eluted with buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. GST-tagged or MBP-tagged proteins were purified using glutathione or amylose resin and eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione or maltose respectively. Further purification was performed by gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex 200 16/60 pg column. Purified proteins were stored in buffer A (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM TCEP).

Cell culture, transfection, and colocalization assays

HEK293 T cells (Thermo Fisher) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Lonza) and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For the colocalization assay, cells were transfected with pCDNA3.1-EGFP-Nsp31-372 and pCDNA3.1-mCherry-N plasmids, respectively, or cotransfected pairwise using Lipofectamine 2000. Plasmids pCDNA3.1-EGFP and pCDNA3.1-mCherry were used as control groups and performed with the same approach. After 48 h posttransfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20. Then, cells were stained with DAPI to show the cell nucleus. Pictures were subsequently taken with an Olympus Spin co-focus fluorescence microscope (Olympus Life Science).

Gel electrophoresis

Native agarose gel electrophoresis was used to analyze the RNAs or proteins. To detect the quantity of RNAs bound with proteins or protein–protein complexes, native agarose gel at 0.8% concentration containing 1‱ nucleic acid dye was prepared. The RNA–protein or protein–protein complexes were treated with SDS-free loading buffer and subjected to native agarose gel electrophoresis. RNAs were detected under ultraviolet light. Then the gels were stained with CBB R250 to analyze proteins. SDS-PAGE and CBB staining were also used to analyze the proteins for pull-down assays.

Phase separation assays

EGFP-tagged Nsp31-372 or FITC-stained Ubl1 and mCherry-tagged N protein were purified and stored in the buffer as described above. To detect the influence of Nsp31-372 or Ubl1 on the LLPS of N protein, indicated concentrations of EGFP-tagged Nsp31-372 or Ubl1 were mixed with indicated concentration of mCherry-tagged N protein. Subsquently, 10% PEG6000 was added to initiate phase separation. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 15 min. A total of 5 μl mixture was loaded onto microscope slide, covered with a coverslip, and sealed with nail polish. The droplets were imaged on the Olympus FV3000 laser scanning confocal system and analyzed by the Olympus cellSens software.

GST pull-down assays

For GST pull-down assays, cells were suspended with lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, and 150 mM NaCl). Cell suspensions containing GST-tagged Nsp31-372 or other truncations of Nsp3 were mixed with suspensions containing MBP-tagged N protein or with lysis buffer as blank control at 1:1 ratio. An equal part of the mixtures were separated and added with or without excess nuclease. After sonication, supernatants were collected by centrifugation and incubated with 50 μl glutathione beads for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing with 1.5 ml lysis buffer for six times, the beads were eluted with 50 μl elution buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM reduced glutathione). As to the His6 pull-down assays for Ubl1-His6 and MBP-N, purified Ubl1-His6 was mixed with the cell suspensions containing MBP-N (lysis buffer: 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole) and homogenized with sonication. Supernatants were classified by centrifugation and incubated with 50 μl NI-NTA beads for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing with 1.5 ml washing buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 30 mM imidazole) for six times, the beads were eluted with 50 μl elution buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 500 mM imidazole). All the eluted samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with nucleic acid dye or Coomassie brilliant blue.

Crystallization, data collection, and structure determination

His6-tagged Nsp3 (residues 18–107) was purified as described above. Protein was crystallized via the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 16 °C. Optimal crystals were obtained in the optimal solution containing 0.1 M Hepes sodium, pH 7.5 and 1.4 M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate. A single crystal was soaked in a cryoprotectant solution containing 0.1 M Hepes sodium, pH 7.5, and 1.4 M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate, and 20% glycerol for 1 min and rapidly cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data collection was performed at beamline BL02U1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. iMosflm was used to process the diffraction data. Molecular replacement by Phaser was processed for the primary phase using the model of SARS-CoV Ubl1 [Protein Data Bank accession number: 7TI9]. Refmac and Phenix were utilized for the refinement. The final model was generated by manual model building with WinCoot software.

Transcription in vitro

The DNA sequence of 5′-UTR of SARS-CoV-2 genome (GenBank: OV054768.1) containing T7 promoter was amplified using PCR and purified for the template of transcription. HiScribe T7 RNA Synthesis Kit (NEB) was used to synthesize 5′-UTR following the protocol. 5′-UTR was purified by isopropyl alcohol precipitation method and stored at −80 °C.

NMR assays

The preparation of protein and RNA samples for NMR characterization is detailed below. Uniform 15N-labeling of the Ubl1 protein was achieved by adding 0.1% (m/v) 15NH4Cl to M9 media prior to the protein overexpression stage. The 15N-Ubl1 protein, along with N protein at natural isotopic abundance, was dissolved in the buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, 8% D2O (v/v) for NMR characterization. The 5′-UTR RNA was prepared in RNAse-free water. Ultra nuclease (NEB) was used directly as produced. Two NMR samples were prepared with a total volume of 450 μl each: one containing 200 μM 15N-Ubl1, 24 μM N protein, and 20 μM 5′-UTR, and the other containing 200 μM 15N-Ubl1 and 20 μM 5′-UTR, both before the addition of 5 μl ultra nuclease.

The serial 2D 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra during titration were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 MHz spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin GmbH). All spectra were acquired using the hsqcfpf3gpphwg pulse program, with 12 scans per spectrum. The O1P and spectral width parameters were set to 4.697 and 13.657 ppm for the 1H dimension and 117.750 and 27.500 ppm for the 15N dimension, respectively. The software TopSpin and NMRPipe were used to process raw NMR data, and POKY was used for data analysis and spectra visualization (34, 35).

Sequence alignments

The Ubl1 sequences of indicated coronaviruses were acquired from NCBI. The sequence alignments and results output were performed with the online tools of CLUSTALW and ESprint 3.0, respectively.

Data availability

The crystal structure of Ubl1 of Nsp3 from SARS-CoV-2 has been uploaded to the PDB database (PDB accession number: 8XAB).

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the BL02U1 beamline at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for technical assistance. We thank Professor Shuguo Sun of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology for the help in using the confocal microscopy device. We appreciate Wei Wang from Medical Subcenter of HUST Analytical & Testing Center in NMR data acquisition.

Author contribution

H.Z., Z.K., and Y.L. writing–review & editing; H.Z. and Z.K. visualization; H.Z., Z.K., Y.W., Y.L., H.H., F.P.,J.W., X.L., and Ji.W. methodology; H.Z., Z.K., and X.L. investigation. Z.K. writing–original draft; Z.K. validation; Y.L. supervision; Y.L. and X.L. resources; Y.L. project administration; Y.L. funding acquisition; Y.L., Z.K., and H.H. conceptualization.

Funding and additional information

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC2600200 and 2022YFC2305500 to Y.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172299 to Y.L.), the Hubei Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (2022CFA068 to Y.L.), and the Hubei Public Health Youth Talents Program (to Y.L.).

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Craig Cameron

Contributor Information

Xiaotian Liu, Email: liuxt@sustech.edu.cn.

Hongbing Hu, Email: whfesx@163.com.

Yan Li, Email: yanli@hust.edu.cn.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Kaul D. An overview of coronaviruses including the SARS-2 coronavirus - molecular biology, epidemiology and clinical implications. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2020;10:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmrp.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawicki S.G., Sawicki D.L., Younker D., Meyer Y., Thiel V., Stokes H., et al. Functional and genetic analysis of coronavirus replicase-transcriptase proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yadav R., Chaudhary J.K., Jain N., Chaudhary P.K., Khanra S., Dhamija P., et al. Role of structural and non-structural proteins and therapeutic targets of SARS-CoV-2 for COVID-19. Cells. 2021;10:821. doi: 10.3390/cells10040821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao K., Ke Z., Hu H., Liu Y., Li A., Hua R., et al. Structural basis and function of the N terminus of SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 1. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021;9 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00169-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang C.K., Hou M.H., Chang C.F., Hsiao C.D., Huang T.H. The SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein--forms and functions. Antivir. Res. 2014;103:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurst K.R., Kuo L., Koetzner C.A., Ye R., Hsue B., Masters P.S. A major determinant for membrane protein interaction localizes to the carboxy-terminal domain of the mouse coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 2005;79:13285–13297. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13285-13297.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng Y., Du N., Lei Y., Dorje S., Qi J., Luo T., et al. Structures of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and their perspectives for drug design. EMBO J. 2020;39 doi: 10.15252/embj.2020105938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo C.Y., Tsai T.L., Lin C.N., Lin C.H., Wu H.Y. Interaction of coronavirus nucleocapsid protein with the 5'- and 3'-ends of the coronavirus genome is involved in genome circularization and negative-strand RNA synthesis. FEBS J. 2019;286:3222–3239. doi: 10.1111/febs.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iserman C., Roden C.A., Boerneke M.A., Sealfon R.S.G., McLaughlin G.A., Jungreis I., et al. Genomic RNA elements drive phase separation of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid. Mol. Cell. 2020;80:1078–10791.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savastano A., Ibanez de Opakua A., Rankovic M., Zweckstetter M. Nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 phase separates into RNA-rich polymerase-containing condensates. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:6041. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19843-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson C.R., Asfaha J.B., Ghent C.M., Howard C.J., Hartooni N., Safari M., et al. Phosphoregulation of phase separation by the SARS-CoV-2 N protein suggests a biophysical basis for its dual functions. Mol. Cell. 2020;80:1092–10103.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack A., Ferro L.S., Trnka M.J., Wehri E., Nadgir A., Nguyenla X., et al. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein forms condensates with viral genomic RNA. PloS Biol. 2021;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu S., Ye Q., Singh D., Cao Y., Diedrich J.K., Yates J.R., 3rd, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein forms mutually exclusive condensates with RNA and the membrane-associated M protein. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:502. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20768-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberti S., Gladfelter A., Mittag T. Considerations and challenges in studying liquid-liquid phase separation and biomolecular condensates. Cell. 2019;176:419–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forman-Kay J.D., Kriwacki R.W., Seydoux G. Phase separation in biology and disease. J. Mol. Biol. 2018;430:4603–4606. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stertz S., Reichelt M., Spiegel M., Kuri T., Martinez-Sobrido L., Garcia-Sastre A., et al. The intracellular sites of early replication and budding of SARS-coronavirus. Virology. 2007;361:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuniga S., Cruz J.L., Sola I., Mateos-Gomez P.A., Palacio L., Enjuanes L. Coronavirus nucleocapsid protein facilitates template switching and is required for efficient transcription. J. Virol. 2010;84:2169–2175. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02011-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cong Y., Ulasli M., Schepers H., Mauthe M., V'Kovski P., Kriegenburg F., et al. Nucleocapsid protein recruitment to replication-transcription complexes plays a crucial role in coronaviral life cycle. J. Virol. 2020;94:e01925–e02019. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01925-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei J., Kusov Y., Hilgenfeld R. Nsp3 of coronaviruses: structures and functions of a large multi-domain protein. Antivir. Res. 2018;149:58–74. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurst K.R., Ye R., Goebel S.J., Jayaraman P., Masters P.S. An interaction between the nucleocapsid protein and a component of the replicase-transcriptase complex is crucial for the infectivity of coronavirus genomic RNA. J. Virol. 2010;84:10276–10288. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01287-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurst K.R., Koetzner C.A., Masters P.S. Characterization of a critical interaction between the coronavirus nucleocapsid protein and nonstructural protein 3 of the viral replicase-transcriptase complex. J. Virol. 2013;87:9159–9172. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01275-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keane S.C., Giedroc D.P. Solution structure of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) nsp3a and determinants of the interaction with MHV nucleocapsid (N) protein. J. Virol. 2013;87:3502–3515. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03112-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bessa L.M., Guseva S., Camacho-Zarco A.R., Salvi N., Maurin D., Perez L.M., et al. The intrinsically disordered SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein in dynamic complex with its viral partner nsp3a. Sci. Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng W., Liu G., Ma H., Zhao D., Yang Y., Liu M., et al. Biochemical characterization of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;527:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.04.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni X., Han Y., Zhou R., Zhou Y., Lei J. Structural insights into ribonucleoprotein dissociation by nucleocapsid protein interacting with non-structural protein 3 in SARS-CoV-2. Commun. Biol. 2023;6:193. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-04570-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verheije M.H., Hagemeijer M.C., Ulasli M., Reggiori F., Rottier P.J., Masters P.S., et al. The coronavirus nucleocapsid protein is dynamically associated with the replication-transcription complexes. J. Virol. 2010;84:11575–11579. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00569-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang C.K., Hsu Y.L., Chang Y.H., Chao F.A., Wu M.C., Huang Y.S., et al. Multiple nucleic acid binding sites and intrinsic disorder of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein: implications for ribonucleocapsid protein packaging. J. Virol. 2009;83:2255–2264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02001-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan L., Ge J., Zheng L., Zhang Y., Gao Y., Wang T., et al. Cryo-EM structure of an extended SARS-CoV-2 replication and transcription complex reveals an intermediate state in cap synthesis. Cell. 2021;184:184–193.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouvet M., Debarnot C., Imbert I., Selisko B., Snijder E.J., Canard B., et al. In vitro reconstitution of SARS-coronavirus mRNA cap methylation. Plos Pathog. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandilara G., Koutsi M.A., Agelopoulos M., Sourvinos G., Beloukas A., Rampias T. The role of coronavirus RNA-processing enzymes in innate immune evasion. Life (Basel) 2021;11:571. doi: 10.3390/life11060571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhatt P.R., Scaiola A., Loughran G., Leibundgut M., Kratzel A., Meurs R., et al. Structural basis of ribosomal frameshifting during translation of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Science. 2021;372:1306–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.abf3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malone B., Urakova N., Snijder E.J., Campbell E.A. Structures and functions of coronavirus replication-transcription complexes and their relevance for SARS-CoV-2 drug design. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022;23:21–39. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00432-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H., Lv P., Jiang J., Liu Y., Yan R., Shu S., et al. Advances in developing ACE2 derivatives against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4:e369–e378. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee W., Rahimi M., Lee Y., Chiu A. POKY: a software suite for multidimensional NMR and 3D structure calculation of biomolecules. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:3041–3042. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The crystal structure of Ubl1 of Nsp3 from SARS-CoV-2 has been uploaded to the PDB database (PDB accession number: 8XAB).