Abstract

Background

People living in precarious socio-economic conditions are at greater risk of developing mental and physical health disorders, and of having complex needs. This places them at risk of health inequity. Addressing social determinants of health (SDH) can contribute to reducing this inequity. Case management in primary care is an integrated care approach which could be an opportunity to better address SDH. The aim of this study is to better understand how case management in primary care may address the SDH of people with complex needs.

Methods

A case management program (CMP) for people with complex needs was implemented in four urban primary care clinics. A qualitative study was conducted with semi-structured interviews and a focus group with key informants (n = 24). An inductive thematic analysis was carried out to identify emerging themes.

Results

Primary care case managers were well-positioned to provide a holistic evaluation of the person’s situation, to develop trust with them, and to act as their advocates. These actions helped case managers to better address individuals’ unmet social needs (e.g., poor housing, social isolation, difficulty affording transportation, food, medication, etc.). Creating partnerships with the community (e.g., streetworkers) improved the capacity in assisting people with housing relocation, access to transportation, and access to care. Assuming people provide their consent, involving a significant relative or member of their community in an individualized services plan could support people in addressing their social needs.

Conclusions

Case management in primary care may better address SDH and improve health equity by developing a trusting relationship with people with complex needs, improving interdisciplinary and intersectoral collaboration and social support. Future research should explore ways to enhance partnerships between primary care and community organizations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12875-024-02643-7.

Keywords: Integrated care, Social determinants of health, Case management, Complex needs, Primary care

Background

People living in precarious socio-economic conditions, such as food insecurity, poor housing quality, unemployment, social isolation, and difficulty affording utilities and medication[1, 2], are at greater risk of developing mental and physical health disorders [3], and of having unmet health and social needs (hereafter complex needs) [4]. People with complex needs often encounter challenges in access to care and service coordination and transition [5, 6]. Fragmented care may result in frequent emergency department visits or hospitalizations [7], poorer health indicators, higher mortality rates [8], and health inequity [9, 10]. The World Health Organization defines health equity as “the absence of unfair, avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically or by other dimensions of inequality” [11].

Health and social care services for people with complex needs call for integrated care to better meet their needs and improve health equity [12–15]. A systematic review on the effects of integrated care reported benefits in access and quality of care, and patient satisfaction [16]. A meta-analysis showed a 19% reduction in the probability of hospitalization for integrated care, as compared to usual care [17]. Case management is an integrated care program [18] defined as a collaborative, patient-driven approach [19] where case managers “serve as patient advocates to support, guide and coordinate care for patients, families and caregivers as they navigate their health and wellness journeys” [20].

To improve health equity [21, 22] and reduce negative outcomes for people with complex needs [23–25], addressing social determinants of health (SDH) is essential [26]. SDH include a wide range of personal, social, economic, and environmental factors (e.g., culture, education, employment, income, social or physical environment, etc.) that determine the health of an individual or a population [27], and are responsible for much of the inequality in health between and within countries [26]. A holistic understanding of an individual's situation is crucial to understanding complex needs [28]. Keeping in mind that 90% of essential health interventions can be delivered using a primary healthcare approach [29], case managers in primary care have the opportunity to better address individuals’ unmet needs, including SDH [30–32]. More studies are needed to understand how case management in primary care may address SDH for adults with complex needs [31] and improve health equity [31–33]. The aim of this study is to better understand how case management in primary care may address SDH of people with complex needs.

Methods

Design and setting

A descriptive qualitative study was conducted to provide an in-depth understanding [34]. A case management program (CMP) was implemented in four primary care clinics (known as Family Medicine Groups in the province of Quebec, Canada). These clinics were in a high-density urban area, on the territory of a health and social services organization that serves 430,000 people over 88 km2. This organization included hospital, local community services, residential and long-term care, child and youth protection, and rehabilitation centers [35].

Partners from the health and social services organization presented the project to primary care clinics located on its territory (n = 16), with the support of the research team. Four clinics were recruited using a non-probability sample of volunteers [36]. Two clinics were University Family Medicine Groups, that were affiliated with the health and social services organization, while the other two had no such affiliation. All primary care clinics included an interdisciplinary team of family physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, nutritionists, social workers, psychotherapists, pharmacists, etc. The University Family Medicine Groups also included residents in family medicine, and students and interns from various disciplines.

Description of the CMP

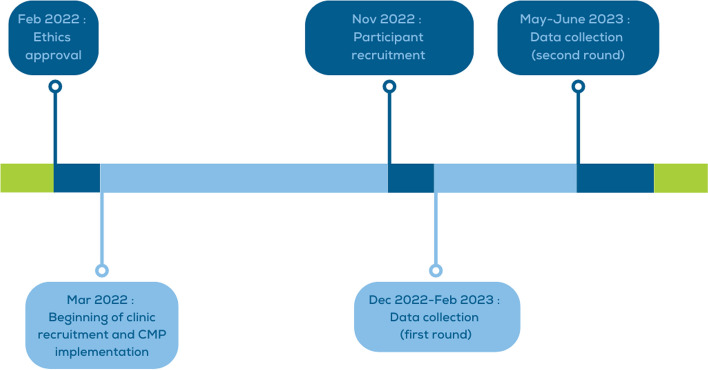

The CMP was developed in the last decade by the research team [37, 38] in line with case management standards of practice [20, 39] and six patient-centered integration characteristics [40]: (a) goal and expected outcomes of the person receiving care, (b) communication, (c) information, (d) decision making, (e) care planning, and (f) transitions. It comprised four main components [37]: 1) assessment of the needs, long-term goals, and preferences of the person and their family, 2) development and monitoring of an individualized services plan in collaboration with the person, their family, and partners involved in health and social care, 3) coordination of services among all partners, and 4) education and self-management support for the person and their family. In previous research, participants to this CMP reported positive experience of integrated care [41] and showed reduced psychological distress [42]. The CMP was implemented and evaluated over a 15-month period, between March 2022 and June 2023, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Project timeline

Primary care case managers, i.e., nurses and social workers, received an initial training lasting four hours. They started to perform the CMP with the support of an implementation committee based in the health and social services organization. The implementation committee included three hospital program managers and a hospital case manager. The hospital program managers were involved in the recruitment of the clinics. They also supported primary care program managers in the planning and follow up (monitoring) phases of the CMP implementation. The hospital case manager trained and closely supported primary care case managers both individually and through a community of practice. The nature of the work of the case manager in the hospital and primary care clinics was similar, but the hospital case manager had a dedicated role (full time), while primary care case managers integrated case management with their other activities (part time). The clinics did not receive any additional budget to implement the program. Case managers were provided with clinical and training materials, including self-supporting web modules, a tool to identify patients with complex needs [43], and several other clinical tools. These materials are available upon request to the first author (CH).

Patients targeted by the CMP were adults (18 + years old) having: six visits or more to the emergency department during the previous year; a positive score on the CONECT-6 screening tool for complex needs [43]; and complex needs confirmed by the primary care nurses or family physicians. Primary care case managers received lists of eligible patients registered to their clinics, with their consent, from the hospital case manager at each administrative period (≈ 1 list per month). Physicians helped primary care case managers in prioritizing the patients on the lists based on their complex needs (clinical judgement). All staff at the clinics were informed about the project and collaborated with and supported the primary care case managers to identify patients and plan for their care.

Participants and data collection

Participants (n = 24) were recruited through key informant sampling [36], and included hospital program managers (n = 3), one hospital case manager, one administrative agent, primary care program managers (n = 3), physician leads from the clinics (n = 4), primary care case managers (n = 8), other healthcare providers within the clinics (n = 3), and one external project manager working with the research team to support the implementation process. Research assistants contacted them by e-mail, who then signed, scanned, and e-mailed back information and consent forms. Semi-structured interviews and one focus group were conducted from December 2022 to June 2023. Semi-structured interviews aim to explore in depth each participant's views, experiences, beliefs and knowledge [44]. Because of the patients’ personal situation, administrative barriers to accessing their medical information, and the short project duration, the research team and primary care case managers were unable to recruit patients for the semi-structured interviews or focus group.

Of the 24 participants, 23 were interviewed nine to 11 months after CMP implementation began (from December 2022 to February 2023), and one was interviewed 14 months post CMP initiation (in May 2023). Nine participants were interviewed a second time in May and June 2023. We conducted a focus group in April 2023 during a clinical support meeting with the primary care case managers (n = 9) and the hospital case manager. An interview guide (see Supplementary file 1) helped to facilitate the discussions around participants’ views on how case management in primary care may address the SDH of people with complex needs. The interviews and focus group were conducted virtually on Microsoft Teams [45] and audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized. Interview and focus group summaries captured key ideas.

Analysis

Qualitative data was analyzed using inductive thematic analysis [46] and managed by two research staff members with expertise in qualitative research (MB, EAG) using NVivo V.12 server software (QSR International Pty). Sources of data were organized by the type of participant and the setting they belonged to using detailed labels. Data was analyzed in two stages. In stage one, data was coded by emerging themes [46], from which a codebook related to SDH was developed, detailing themes and sub-themes. In stage two, pattern coding, an iterative method of theme collapsing [46], was used to generate a narrative focused on explicative global categories of data. Four research team meetings were organized between October 2022 and June 2023 to discuss preliminary analysis and findings. Two patient partners took part in these meetings and had the opportunity to express their views with other team members.

Results

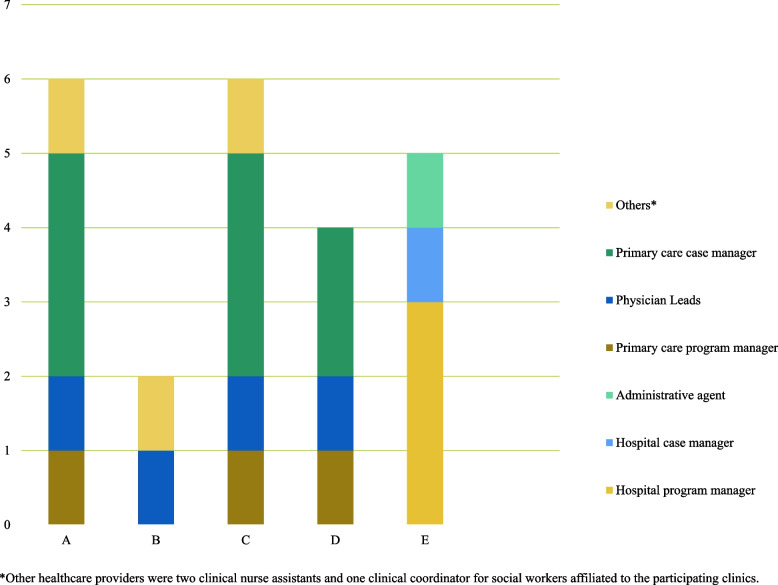

Figure 2 presents the distribution of participants involved in the study by setting: A to D correspond to the four primary care clinics (n = 18), and E corresponds to the health and social services organization (n = 5). The other participant was the project manager who worked with the research team.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of participants by setting

A total of 24 participants completed the study (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

| Characteristic | N |

|---|---|

| Gendera | |

| Female | 22 |

| Male | 2 |

| Age (years) | |

| 25–34 | 6 |

| 35–44 | 13 |

| 45–54 | 4 |

| 55–64 | 1 |

| Position | |

| In the health and social services organization | |

| Hospital program manager | 3 |

| Hospital case manager | 1 |

| Administrative agent | 1 |

| In the primary care clinics | |

| Primary care program manager | 3 |

| Physician lead | 4 |

| Nurse clinician case manager | 6 |

| Social worker case manager | 2 |

| Other healthcare providerb | 3 |

| External | |

| Project manager | 1 |

| Highest degree of education | |

| Professional studies | 1 |

| Bachelor’s | 13 |

| DESSc | 2 |

| Master’s | 4 |

| Doctorate | 4 |

| Mean | |

| Number of years of practice | 11 |

| Number of years in current position | 3 |

aOther categories such as non-binary, gender fluid, two-spirited, and others were suggested; no participant, however, identified as one of these categories

bOther healthcare providers were two clinical nurse assistants and one clinical coordinator for social workers affiliated to the participating clinics

cIn Quebec, the DESS (Diplôme d’études supérieures spécialisées) is a specialized graduate diploma of shorter duration than a Master’s or Doctorate

The qualitative data analysis led to three major themes, which are described below.

Case managers may understand the person’s overall situation, develop trust with them, and act as their advocates

Case managers were well-positioned to understand people’s social needs. They evaluated people’s health and social situation in greater depth. As the project manager and case manager within a clinic respectively noted:

It's also more inclusive for them [people with complex needs]. The term inclusive in the sense that these people are often marginalized to some extent, but it brings a certain openness to taking into account the whole dimension of their lives. (Project manager, research team)

Finally, by digging a little, [the social worker case manager] realized why [the patient] was always going to the emergency room, it's because he didn't have a home, he was itinerant you know, it's like the base, we have to see where he stays, if he already has a home, after that, it might go further later if it's not in the priority problems - it's because he can't afford his medication that he goes to the emergency room. (Other healthcare provider, clinic A)

This broader understanding also helped overcome prejudices or negative perceptions healthcare providers may have towards people with complex needs. As one program manager mentioned, “the [CMP] can help professionals understand the reasons behind emergency room visits, rather than relying on the patient's image at first glance.”

Establishing trust with people helped case managers to address their unmet social needs. Case managers were an ‘anchor’ within the healthcare system, i.e., someone patients can regularly refer to. As such, case managers may improve patients’ well-being (i.e., decrease stress and anxiety through reassurance). Case managers were also better positioned to provide follow-up care, including making appointments with hard-to-reach people. As one case manager mentioned:

For the patient, the impression I get is that it can develop a kind of anchoring. A person [case manager] who isn't always changing . . . who will probably be able to deconstruct the difficulties of understanding a prescription, of giving a course of action, all sorts of things that I realize patients are really struggling with. ... I imagine it will improve adherence to treatment, it will improve follow-up, I really see it like that. (Primary care case manager, clinic A)

Another case manager stated, “having someone to contact helps a lot with follow-up for people who are hard to reach or who don't turn up for their appointments. The [CMP] makes it easier to book appointments and improves adherence to the care plan”. According to a clinic program manager, the time spent with the case manager increases the satisfaction of the person receiving care and positively influences their perception of the healthcare system:

Focusing on consultation efficiency increased both satisfaction and positive perception of the healthcare system, and capacity for exchange during consultations. (Program manager, clinic A)

Case managers also helped people with unmet social needs navigate the healthcare system. As one physician lead mentioned, "[CMP] enables smoother navigation through the healthcare system for patients with psychosocial and addiction issues”. Another physician lead explains:

[Case managers can] bypass the processes (e.g., telephone line, standard appointment scheduling), facilitate the navigation of services, guide the person in the procedures, prioritize the request to know if urgent or not, etc. All of this means better access to services. (Physician lead, clinic A)

Case managers could also support people with socioeconomic issues avoiding unnecessary travel. As one case manager noted, "avoiding the patient having to travel for nothing, especially if he has little financial means or no means of transport, or a serious health problem, in which case telehealth is an alternative”.

Case managers could serve as patient advocates, i.e., defend their rights and interests. This advocacy was based upon trust since the case manager believes in the patients’ lived experiences and develops care plans accordingly. As a hospital case manager mentioned:

It's like asserting the patient's rights. [The patient] has the right to refuse to be followed by such an institution, even if the reasons for us are not necessarily valid. But it's his experience. Who are we to say - well, sir, listen, get over it, you know, we're not going to do that. He's lived through his trauma. (Hospital case manager)

The CMP promoted a partnership with the person that focuses on their overall situation, not simply their illness. This partnership took time to develop because primary care case managers needed to collaborate with the patient to design care plans that are meaningful and relevant for the person in line with their life trajectory. As one primary care case manager stated:

I like the more patient-focused aspect. The fact of saying - but what are your life plans? What goals are you pursuing? It also asks patients to think about where they want to go, and what information they want to send to healthcare professionals? Because I have my agenda when I look at a file, but it has to match the patient's agenda too. (Primary care case manager, clinic A)

As one hospital program manager mentioned, by promoting patient-centered care among the disciplines and organizations involved, the CMP stimulated a change of culture within the system:

The management of patients with complex needs … requires another protocol, to change the way decision-makers and professionals perceive them, to determine individual particularities so as to know how to intervene, and to accompany patients to act on these particularities. We need to take time for this. (Hospital program manager 1)

Case managers stimulate interprofessional and intersectoral collaboration

Meetings to develop the individualized services plan may help people understand how interprofessional collaboration and care responds to their health and social needs. As one case manager mentioned:

I like the idea of meeting with the patient and then with the caregivers (i.e., healthcare providers), because the patient sees that we're not doing this for nothing. We all get together because we want it to work, we want it to progress, we want there to be an answer to your problem. … so I hope that the person will be better able to understand why we're doing this care, why we're asking for these tests, why it's important to do them, otherwise we won't get any more answers. (Primary care case manager, clinic A)

One program manager within a clinic mentioned that working as an interdisciplinary team helps to demedicalize services and consider the whole person and their psychosocial needs. The program manager explains that “we were starting to work on demedicalizing all appointments in the sense that they're less medico-centric, that they go through the right professional depending on the person's needs rather than systematically going to the doctor.” The interprofessional care team used their complementary skillsets to deliver patient-centred care. As one physician lead stated, “we have a social worker who can liaise with these organizations when there are more complex problems.”

Given that visiting patients’ homes was not always possible, creating partnerships with community-based organizations, pharmacies, or outreach programs (e.g., home care and street working, i.e., social workers practicing in the community with people in difficult situations) helped to overcome this barrier. As the hospital case manager mentioned, “outreach can help support and [provide] accompaniment [for] the person for relocation, access to transportation, access to services (community, primary and secondary [care])”. Another healthcare professional mentioned that outreach was especially important to develop trust with new people arriving to the country:

We need to have someone on the ground to get to know new arrivals better, as they don't open up easily about their quality of life, housing, health, etc. We need to create a bond of trust. Outreach would enable us to better assess their needs. We need to collaborate with street workers, community organizations, and pharmacies, who are more familiar with the living environment, social network, and socio-cultural characteristics of these people. (Other healthcare professional, affiliated with all clinics).

Despite the recognition that community partnerships were indispensable in meeting people’s needs, these partnerships needed to be developed further. As one hospital program manager mentioned:

This would be a very good move to really see how we can integrate the community, because we know that the healthcare system alone can't do it, but it's by believing in collaboration with other sectors outside the healthcare system that we'll get there, really with community organizations. … how we can reach out to more partners in the community, because that's where it all starts. (Hospital program manager 2)

To this end, this hospital program manager called for organizational development and change management to develop partnerships with external organizations:

Include organizational development and change management. We start out with a dream, objectives, and a structure, but some people are going to have to change their perceptions and practices. This is no trivial matter. We experience it every day: it's not just the hospital sector, but a large part of care is provided outside the hospital. We need to develop confidence in external organizations. (Hospital program manager 2)

Case managers may improve social support

Involving any family, friends, or significant relatives in the individualized services plan was another way of meeting social needs. As one case manager stated:

I still have doctors who refuse to see two people in their office, but I accept the husband, the brother, the father, it doesn't matter, whether there are two of them, sometimes it's to help with the translation, sometimes it's just to accompany because the person is stressed, so the fact of integrating a family member, do you want to be accompanied? I think it's important to name it. (Primary care case manager, clinic C)

Another case manager mentioned:

Of course, it's easier if the person has support from those around them. It's often when they don't have any other support, that's when they have the most difficulty ... often they don't have any resources and they don't know where to turn, so I think having a case manager will really help. (Primary care case manager, clinic D)

It was important to ask the person if they would like to be accompanied, because involving a family member may pose certain issues. As the hospital case manager highlighted:

There are limits to involving the network in the intervention: the social network may face issues of its own, similar or different; the patient doesn't want to disturb his or her network due to network exhaustion or conflictual relationships; the patient is wary of relating certain problems to his or her network (confidentiality issues). (Hospital case manager)

However, for people with no family or social network, the support from the case manager could be reassuring. As one case manager mentioned, “if the person is isolated, it can be very reassuring to have someone at the end of the line, available, and accessible”.

Immigrants that are socially isolated could also feel supported by the case manager. As one physician lead explains:

I have patients who are immigrants, and most of their families are in their country of origin. So this kind of solitude is very difficult. I see it more on the positive side, where if you're a focal point for them, I think it's going to be helpful to feel that they're supported, that they're not alone. And then slowly bring them at the community level, into organizations where they can get together, to create a network. (Physician lead, clinic D)

People from the same cultural community as the person could be involved to promote health and social services. As one hospital program manager stated, “within the same cultural community, people talk to each other and pass on information. Working through community members to raise awareness of the use, availability, and operation of services is an asset”.

Discussion

Case management in primary care may better address SDH and improve health equity by evaluating a person’s whole situation in greater depth, developing a relationship of trust, and acting as advocates for them. Further, case management can improve interdisciplinary and intersectoral collaboration, and social and community support.

Results raised the importance of the trusting relationships between the case manager and the person. Developing meaningful relationships and paying attention to non-medical factors such as culture and personal goals and expectations can take time, but it provides insight into care preferences and may improve people’s engagement with the care plan [47]. For marginalized people, a relationship of trust with service providers can mitigate barriers to health equity, for example by improving continuity of care and navigation through health and social services [48]. Beyond this relationship, however, Anderman et al. (2020) also recommend that health-related social interventions like case management provide “socially accountable care”, including services that help to “advocate for structural changes to prevent homelessness and housing precarity” [48].

The study highlighted the importance of collaboration and teamwork in answering unmet social needs. Interdisciplinary activities can help health and social care providers broaden their skills in SDH [49]. Case management can be leveraged to coordinate and facilitate successful interprofessional team efforts, [30] raise awareness of patients’ social needs, [32, 50] and adjust traditional services to focus on social needs [32, 47, 50]. The study identified intersectoral collaboration as an essential strategy for addressing SDH. Partnering with local community groups and existing coalitions that address the needs of marginalized people can help fill gaps in the healthcare system by offering more care options [48]. Collaboration between multiple sectors that contribute to health is necessary to promote a more equitable distribution of resources [51] and healthy living through a healthy environment [52]. Involving organizations with expertise, resources, and opportunities to make a comprehensive and integrated response to SDH [53] is a part of the case manager role. However, developing partnerships between primary care clinics and community resources can be challenging and complex [54]. Some challenges may include unequal decision-making power [55], differences in organizational cultures and bureaucracies [56], inadequate funding [55], and unidirectional communication [56, 57].

Further research is needed to define conditions and strategies for an effective partnership between primary care clinics and community organizations throughout the implementation of urban CMPs. Involving clinic social workers in these strategies may be helpful, as they have an expertise in finding and connecting people with appropriate community resources [58, 59]. Further studies could also explore the experiences of people with complex needs of such partnerships.

The study highlighted that involving trusted, informal caregivers in individualized services plan may support people engaging in a CMP and improve their health and social outcomes [60, 61], and can lead to lower healthcare use and costs [61]. Informal caregivers can help people with care decisions and support, which may contribute to patients’ empowerment [47], and with care transitions [62]. They can also play an important role in promoting interactions with the community network, contributing to the development of strategies aiming to improve health and social care for disadvantaged people [57]. In this regard, case managers are well positioned to improve community support, increase social participation, and strengthen community belonging, especially for immigrants and refugees [63], who had a significant presence in the urban area where the study took place.

Primary care programs such as case management can be adapted to immigrants and refugees by offering flexible and culturally safe services, that are close to them [63–66]. Case management for people with complex needs can also help to advocate for public health policy that improves the continuity of healthcare and the resilience of the healthcare system [65].

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the close partnership between the research team and the implementation committee which facilitated the implementation and identification of participants. Furthermore, the level of involvement of the hospital case manager encouraged buy-in from primary care case managers and enabled them to develop their skills and confidence, particularly with people who had very complex needs.

There were also limitations. We failed in recruiting patients for the interviews. Several factors could explain this challenge including patients’ health and social situation (e.g., personal challenges, residential instability, or health deterioration) that made it difficult to recruit them, administrative barriers to accessing patients’ information, and the implementation of the CMP over a short period of time. Research with hard-to-reach people needs time and various outreach strategies and resources [67]. Even if patients’ perspectives were not broadly included in our findings, the involvement of patient partners (including MDP) in research team meetings helps to mitigate this limitation. Furthermore, the total project duration was limited for a complex intervention, which may have influenced the program's sustainability. Additionally, the program was implemented in an urban area, which may limit the transferability of findings to urban contexts. However, this study provides valuable insights that can guide future research in exploring the impact of case management on SDH within other settings, such as rural areas.

Conclusions

Case management in primary care, a recognized integrated care approach, may help to address SDH and improve health equity by evaluating the health and social situation of people with complex needs in greater depth, developing a relationship of trust, and acting as advocates for them. Moreover, case management can improve interdisciplinary and intersectoral collaboration, and social and community support. Further studies could explore the intersectoral collaboration between case managers in primary care clinics and community-based organizations, and the experience of people with complex needs.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the program managers, case managers, and healthcare providers, and the project manager who participated and contributed to the study. We are also grateful for all the patients who participated in the CMP. Moreover, we would like to thank René Benoit, a patient partner who helped validate the results, and Joshua Mitchell for his support in the writing and editorial review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CMP

Case management program

- SDH

Social determinants of health

Authors’contribution

CH and MCC are the co-principal investigators for this project. CH, MCC, GM, and LRDB were responsible for conceptualizing the project. MB and EAG were responsible for recruitment, and data collection and analysis. CH, MCC, GM, LRDB, MB, EAG, and MDP contributed to the validation of the results. MB and CH drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Foundation for Advancing Family Medicine (COVID-19 Pandemic Response and Impact Grant (Co-RIG) Program, Phase II).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Comité d’éthique du Centre intégré universitaire de santé et services sociaux du Nord-de-l’Île-de-Montréal (project number: 2022–2377) according to the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans – TCPS 2 (2022) of the Government of Canada. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation and all measures were taken to ensure respect and confidentiality of the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Heller CG, Rehm CD, Parsons AH, Chambers EC, Hollingsworth NH, Fiori KP. The association between social needs and chronic conditions in a large, urban primary care population. Prev Med. 2021;153:106752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byhoff E, Guardado R, Xiao N, Nokes K, Garg A, Tripodis Y. Association of unmet social needs with chronic illness: a cross-sectional study. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25(2):157–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kivimaki M, Vahtera J, Pentti J, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Hemingway H. Increased sickness absence in diabetic employees: what is the role of co-morbid conditions? Diabet Med. 2007;24:1043–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grembowski D, Schaefer J, Johnson KE, Fischer H, Moore SL, Tai-Seale M, et al. A conceptual model of the role of complexity in the care of patients with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care. 2014;52. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/lww-medicalcare/fulltext/2014/03001/a_conceptual_model_of_the_role_of_complexity_in.5.aspx [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Soril LJJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, Noseworthy TW, Clement FM. Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4): e0123660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joo JY, Liu MF. Case management effectiveness in reducing hospital use: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(2):296–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudon C. Bridging the gap to meet complex needs: an intersectoral action well supported by appropriate policies and governance. Health Res Policy Syst. 2024;22(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty M, Pierson R, Applebaum S. Survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Aff Millwood. 2011;30(12):2437–48 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22072063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Donnell CA, Mackenzie M, Reid M, Turner F, Clark J, Wang Y, et al. Delivering a national programme of anticipatory care in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2012;62(597):e288–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter N, Valaitis RK, Lam A, Feather J, Nicholl J, Cleghorn L. Navigation delivery models and roles of navigators in primary care: a scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Health equity. 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity#tab=tab_1.

- 12.Schoen C, Osborn R, How SK, Doty MM, Peugh J. In Chronic condition: experiences of patients with complex health care needs. In: Eight Countries. 2008. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w1?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.World health organization. Integrated care models: an overview. 2006. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/322475/Integrated-care-models-overview.pdf.

- 14.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care — a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wankah P, Gordon D, Shahid S, Chandra S, Abejirinde IO, Yoon R, et al. Equity promoting integrated care: definition and future development. Int J Integr Care. 2023;23(4):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baxter S, Johnson M, Chambers D, Sutton A, Goyder E, Booth A. The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorling G, Fountaine T, McKenna S, Suresh B. The evidence for integrated care. 2015. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/the-evidence-for-integrated-care. Cited 2023 Oct 24.

- 18.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Bisson M, Brousselle A, Lambert M, Danish A, et al. Case management programs for improving integrated care for frequent users of healthcare services: an implementation analysis. Int J Integr Care. 2022;22(1):11 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8833259/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Case Management Network of Canada: Canadian standards of practice in case management. Connect, collaborate and communicate the power of case management. Available from: http://www.ncmn.ca/resources/documents/english%20standards%20for%20web.pdf

- 20.Case Management Society of America. What Is A Case Manager? Available from: https://www.cmsa.org/who-we-are/what-is-a-case-manager/

- 21.Adler NE, Cutler DM, Harvard University, Fielding JE, University of California, Los Angeles, Galea S, et al. Addressing Social Determinants of Health and Health Disparities: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. NAM Perspect. 2016;6(9). Available from: https://nam.edu/addressing-social-determinants-of-health-and-health-disparities-a-vital-direction-for-health-and-health-care/. Cited 2024 Mar 28.

- 22.Singh GK, Daus GP, Allender M, Ramey CT, Martin EK, Perry C, et al. Social determinants of health in the United States: addressing major health inequality trends for the nation, 1935–2016. Int J MCH AIDS. 2017;6(2):139–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q. 2019;97(2):407–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cockerham WC, Hamby BW, Oates GR. The social determinants of chronic disease. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1S1):S5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974. 2014;129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TAJ, Taylor S. Commission on social determinants of health. closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet Lond Engl. 2008;372(9650):1661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Government of Canada. Social determinants of health and health inequalities. 2024. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html. Cited 2024 Apr 22.

- 28.Manning E, Gagnon M. The complex patient: a concept clarification. Nurs Health Sci. 2017;19(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Primary health care. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care.

- 30.Fink-Samnick E. Managing the social determinants of health: part II: leveraging assessment toward comprehensive case management. Prof Case Manag. 2018;23(5):240–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fink-Samnick E. The social determinants of mental health: definitions, distinctions, and dimensions for professional case management: part 1. Prof Case Manag. 2021;26(3):121–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreuter MW, Thompson T, McQueen A, Garg R. Addressing social needs in health care settings: evidence, challenges, and opportunities for public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42(1):329–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, Reznor G, Atlas SJ. Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):244–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Health and Social Services Institutions. 2018. Available from: https://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/en/reseau/etablissements-de-sante-et-de-services-sociaux/ . Cited 2024 Apr 23.

- 36.Pires A. Échantillonnage et recherche qualitative: essai théorique et méthodologique (Traduction: Sampling and qualitative research: a theoretical and methodological essay). Enjeux Epistémol Méthodol. 1997;169:113. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danish A, Chouinard MC, Aubrey-Bassler K, Burge F, Doucet S, Ramsden VR, et al. Protocol for a mixed-method analysis of implementation of case management in primary care for frequent users of healthcare services with chronic diseases and complex care needs. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e038241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Aubrey-Bassler K, Muhajarine N, Burge F, Pluye P, et al. Case management in primary care for frequent users of health care services: a realist synthesis. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(3):218–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Case Management Network of Canada. Canadian standards of practice in case management. Connect, collaborate and communicate the power of case management. 2009. Available from: https://web.persi.or.id/images/e-library/ncmn.pdf. Cited 2023 Oct 10.

- 40.National Collaboration for Integrated Care and Support. GOV.UK. Integrated Care: Our Shared Commitment. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/integrated-care. Cited 2023 Oct 10.

- 41.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Diadiou F, Lambert M, Bouliane D. Case management in primary care for frequent users of health care services with chronic diseases: a qualitative study of patient and family experience. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Dubois MF, Roberge P, Loignon C, Tchouaket É, et al. Case management in primary care for frequent users of health care services: a mixed methods study. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):232–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hudon C, Bisson M, Dubois MF, Chiu Y, Chouinard MC, Dubuc N, et al. CONECT-6: a case-finding tool to identify patients with complex health needs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krueger R, Casey M. Focus groups. A practical guide for applied research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publishing; 2014. 280 p.

- 45.Microsoft 365. Teams [software]. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation; 2023.

- 46.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis. A methods sourcebook. 3rd ed. Arizona State University, USA: Sage Publication Inc; 2014.

- 47.Kuluski K, Ho JW, Hans PK, Nelson ML. Community care for people with complex care needs: bridging the gap between health and social care. Int J Integr Care. 2017;17(4):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andermann A, Bloch G, Goel R, Brcic V, Salvalaggio G, Twan S, et al. Caring for patients with lived experience of homelessness. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2020;66(8):563–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siegel J, Coleman DL, James T. Integrating social determinants of health into graduate medical education: a call for action. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):159–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 10.17226/25467. [PubMed]

- 51.Chircop A, Bassett R, Taylor E. Evidence on how to practice intersectoral collaboration for health equity: a scoping review. Crit Public Health. 2015;25(2):178–91. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rudolph L, Caplan J, Public Health Institute, Mitchell C, California Department of Public Health, Ben-Moshe K, et al. Health in all policies: improving health through intersectoral collaboration. NAM Perspect. 2013;3(9). Available from: https://nam.edu/perspectives-2013-health-in-all-policies-improving-health-through-intersectoral-collaboration/. Cited 2024 Sep 22.

- 53.Meads G, Ashcroft J, Barr H, Scott R, Wild. The case for interprofessional collaboration: In Health and social care. Blackwell Publishing. Oxford, UK; 2005. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470776308.

- 54.Henderson S, Wagner JL, Gosdin MM, Hoeft TJ, Unützer J, Rath L, et al. Complexity in partnerships: a qualitative examination of collaborative depression care in primary care clinics and community-based organisations in California, United States. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(4):1199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chouinard MC, Bisson M, Danish A, Karam M, Beaudin J, Grgurevic N, et al. Case management programs for people with complex needs: Towards better engagement of community pharmacies and community-based organisations. Angkurawaranon C, editor. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0260928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagner J, Henderson S, Hoeft TJ, Gosdin M, Hinton L. Moving beyond referrals to strengthen late-life depression care: a qualitative examination of primary care clinic and community-based organization partnerships. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Adress the Social Determinants of Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. p. 172. 10.17226/21923. [PubMed]

- 58.Fink-Samnick E. Social work: the power of case management’s interprofessional workforce. Prof Case Manag. 2019;24(6):320–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGregor J, Mercer SW, Harris FM. Health benefits of primary care social work for adults with complex health and social needs: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(6):S8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shier G, Ginsburg M, Howell J, Volland P, Golden R. Strong social support services, such as transportation and help for caregivers, can lead to lower health care use and costs. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2013;32(3):544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hahn-Goldberg S, Jeffs L, Troup A, Kubba R, Okrainec K. “We are doing it together”; the integral role of caregivers in a patients’ transition home from the medicine unit. Hesselink G, editor. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0197831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salami B, Salma J, Hegadoren K, Meherali S, Kolawole T, Diaz E. Sense of community belonging among immigrants: perspective of immigrant service providers. Public Health. 2019;167:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aery A. Innovations to champion access to primary care for immigrants and refugees. Wellesley Institute advancing urban health; 2017. Available from: https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/publications/innova-ons-to-champion-access-to-primary-care-for-immigrants-and-refugees/.

- 65.Wylie L, Corrado AM, Edwards N, Benlamri M, Murcia Monroy DE. Reframing resilience: Strengthening continuity of patient care to improve the mental health of immigrants and refugees. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(1):69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simich L, Beiser M, Stewart M, Mwakarimba E. Providing social support for immigrants and refugees in Canada: challenges and directions. J Immigr Health. 2005;7(4):259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, Chapman K, Twyman L, Bryant J, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;25(14):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.