Abstract

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) represent a class of small particles typically with diameters ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers. These nanoparticles are composed of magnetic materials such as iron, cobalt, nickel, or their alloys. The nanoscale size of MNPs gives them unique physicochemical (physical and chemical) properties not found in their bulk counterparts. Their versatile nature and unique magnetic behavior make them valuable in a wide range of scientific, medical, and technological fields. Over the past decade, there has been a significant surge in MNP-based applications spanning biomedical uses, environmental remediation, data storage, energy storage, and catalysis. Given their magnetic nature and small size, MNPs can be manipulated and guided using external magnetic fields. This characteristic is harnessed in biomedical applications, where these nanoparticles can be directed to specific targets in the body for imaging, drug delivery, or hyperthermia treatment. Herein, this roadmap offers an overview of the current status, challenges, and advancements in various facets of MNPs. It covers magnetic properties, synthesis, functionalization, characterization, and biomedical applications such as sample enrichment, bioassays, imaging, hyperthermia, neuromodulation, tissue engineering, and drug/gene delivery. However, as MNPs are increasingly explored for in vivo applications, concerns have emerged regarding their cytotoxicity, cellular uptake, and degradation, prompting attention from both researchers and clinicians. This roadmap aims to provide a comprehensive perspective on the evolving landscape of MNP research.

Keywords: magnetic nanoparticle, biomedical application, magnetic imaging, magnetic biosensing, hyperthermia, tissue engineering, drug delivery

Introduction

In recent years, the study of nanomaterials has gone beyond traditional scientific boundaries, opening a new era of possibilities across various disciplines. Among these, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have emerged as a popular class of nanomaterials, exhibiting unique physicochemical properties due to their nanoscale dimensions and magnetic compositions. MNPs are composed of magnetic cores made from materials such as iron, cobalt, nickel, or their alloys, along with one or more organic/inorganic shells. They are typically exhibiting diameters within the range of 1–100 nanometers.

In the last decade, MNPs have found applications not only in the biomedical domain but also in environmental remediation, data storage, energy storage, and catalysis. This roadmap serves as a comprehensive guide, navigating through the current landscape of MNPs in nanomedicine research. Each section in this roadmap unfolds a distinct facet of MNPs, from understanding their magnetic properties to exploring innovative biomedical applications such as sample enrichment, bioassays, medical imaging, hyperthermia, neuromodulation, tissue engineering, and drug/gene delivery. Furthermore, the roadmap addresses crucial aspects like cellular uptake and degradation, providing a holistic perspective on the evolving landscape of MNP research in the dynamic field of nanomedicine.

Section 1 lays the groundwork for this roadmap by introducing fundamental knowledge about MNPs. Key parameters such as saturation magnetization and magnetic anisotropy are introduced. Compared to their bulk counterparts, MNPs usually show lower saturation magnetization and higher anisotropy due to the spin canting effect. In many applications, MNPs experience rapidly changing magnetic fields, particularly alternating magnetic fields. This dynamic environment poses challenges in predicting and modeling the responses of an ensemble of MNPs, considering coupled Néel and Brownian relaxations, along with dipole-dipole interactions. Various mathematical models have been developed to explain the dynamic magnetizations of MNPs, including the Stoner Wohlfarth (SW) model, static Langevin model, Debye model, Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert (LLG) model, stochastic Langevin model, and Fokker-Planck model. Each model comes with its own set of advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different external field conditions.

The synthesis and functionalization of MNPs have been the focus of extensive research to tailor their properties for specific applications. Thus, in sections 2–4, we have covered the synthesis, surface functionalization, and characterization methods for MNPs. The continual effort to improve the chemical and magnetic properties of MNPs is driving advancements in their medical applications. Synthesis methods are crucial in shaping key tunable aspects like size, morphology, surface chemistry, and magnetic properties. Section 2 discussed various synthesis methods, encompassing physical, chemical, and biological approaches. Surface functionalization plays a vital role in shaping the physical and chemical properties of MNPs and determining their potential applications. This process not only ensures the colloidal stability and biocompatibility of MNPs but also influences their interactions with biological systems, impacting behaviors such as cellular uptake for cell-based therapy. Over the last decade, significant strides have been made, presenting opportunities for improved biocompatibility, minimal opsonization, precise targeting, and enhanced single-cell sensitivity in imaging and diagnosis. In section 3, the critical role of MNP surface functionalization in biomedical applications is emphasized, along with an acknowledgment of current limitations. Specifically, it highlights the absence of standardized characterization techniques, qualification strategies, and the need for greater reproducibility across studies in the current state of MNPs’ surface functionalization. Finally, the characterization of MNPs is essential to guarantee that their inherent properties align with the diverse demands of biomedical applications. Section 4 provides an overview of prevalent characterization techniques employed to gather information on MNPs, including their size and morphology, structure and composition, colloidal stability, magnetic properties, and more. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that specific characterization techniques present challenges that demand meticulous attention. In addition to conventional methods, this section explores several advanced techniques designed to tackle current challenges in MNP characterization.

Sections 5 and 6 cover the MNP-based magnetic enrichment and bioassays. Magnetic separation is a critical technique in biomedical fields, facilitating sample enrichment for diagnostics, therapeutics, and cellular biology research. This method efficiently isolates and purifies target substances based on their magnetic properties (either magnetically labeled by MNPs or label-free). It is especially valuable for recovering and analyzing target bio-entities present at ultra-low concentrations, particularly in the context of early disease diagnosis. However, the complexity of the magnetic separation process involves various factors influencing material behavior under an external magnetic field. In section 5, the authors address key challenges for both types of magnetic separation filters to enhance performance and throughput, along with recent advances in the field. Considering the nonmagnetic nature of most biological samples, employing MNPs as labels for detecting biological target analytes offers an inherent advantage, resulting in minimal background noise and, consequently, enhanced detection limits compared to analogous chemical or optical labels. In section 6, various magnetic biosensors are examined, and diverse bioassay mechanisms are detailed. Challenges associated with the transformation of magnetic biosensors into point-of-care applications are discussed. With the increasing demand for multiplexing bioassays that are faster, more sensitive, and cost-effective, there is a need for fully automatic assays that require minimal effort from users.

Medical imaging is a crucial component of contemporary healthcare, offering valuable insights into the structure and function of the human body in a minimally invasive manner. Two prominent medical imaging techniques currently leveraging MNPs are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic particle imaging (MPI). MNPs are commonly used as contrast agents in MRI to improve visibility, and their application as T1, T2, or dual T1/T2 contrast agents was discussed in section 7. While gadolinium-based contrast agents are widely used, they pose risks such as nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and brain deposition. Researchers are exploring manganese as a T1-weighted alternative, but its toxicity raises concerns. Ongoing research focuses on iron-oxide-based MNPs as biocompatible contrast agents and drug carriers, despite susceptibility artifacts in T2-weighted images, emphasizing the need for colloidal stability in developing new dual-contrast MR agents.

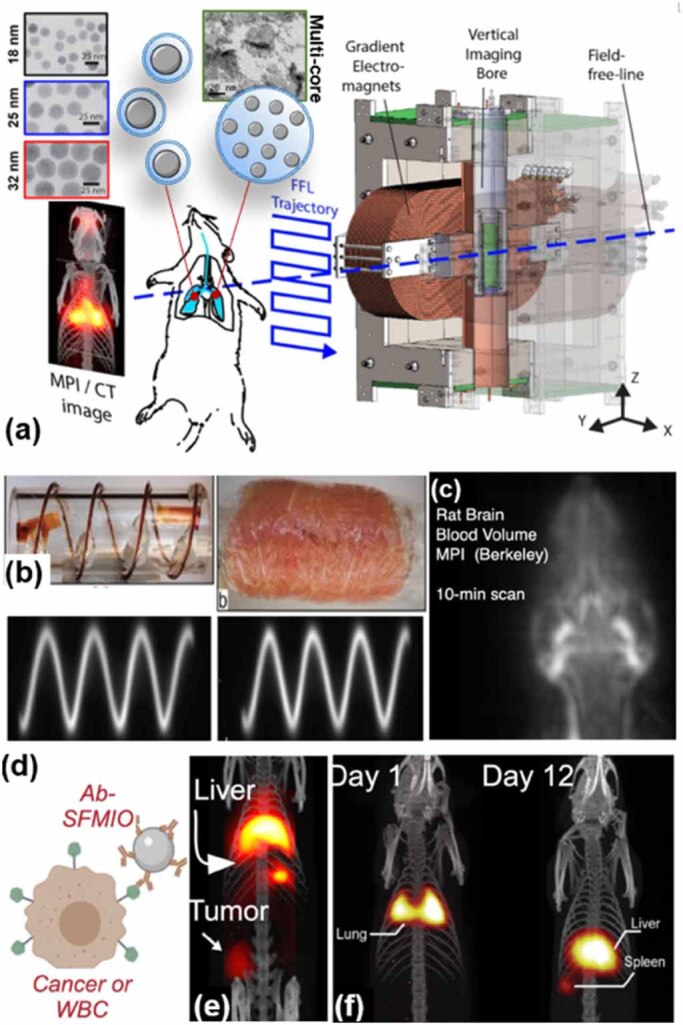

Section 8 discussed MPI, which is an emerging imaging technique distinct from MRI in hardware and physics, offering excellent safety, contrast, sensitivity, and robustness. Despite being the only non-radioactive deep tissue ‘reporter/tracer’ imaging method, MPI faces challenges such as superparamagnetism limitations on the MNP tracers’ sizes and lower spatial resolution compared to computed tomography (CT), MRI, and ultrasound. Ongoing efforts involve utilizing tailored superferromagnetic nanoparticle tracers with steeper magnetization curves and smaller saturation fields, leading to significant improvements in both MPI resolution and signal-to-noise ratio. Strategies to extend the circulation half-life of MNP tracers and employ active approaches like diapedesis by tumor-associated immune cells are proposed to enhance the targeted delivery of MNPs, improving the specificity of MPI.

Sections 9–12 are a collection of therapeutic applications of MNPs. Magnetic hyperthermia is a popular therapy tool for cancer treatment, yet its effectiveness is hindered by challenges in achieving uniform heat distribution during tumor-specific thermal treatment. Self-regulating magnetic hyperthermia emerges as a promising solution to ensure consistent heating throughout the targeted tissue. In section 9, the current state of self-regulating magnetic hyperthermia was discussed, relying on the premise that MNPs possess a magnetic transition temperature (TC) around the intended treatment temperature, ensuring magnetic heating is confined to that specific temperature range. Despite its potential, the synthesis of well-dispersed self-regulating magnetic hyperthermia nanoparticles presents a considerable challenge, mainly due to the limited availability of magnetic materials with transition temperatures close to the body temperature, which is vital for the efficacy of hyperthermia treatment.

When subjected to an alternating magnetic field (AMF), MNPs generate heat, mechanical force, and/or electric fields at the nanoscale. The ion channels in neurons are responsive to these types of external stimuli mediated by MNPs, as detailed in section 10. Various existing MNP-mediated neuromodulation techniques, including magnetothermal, magnetoelectric, chemomagnetic, and magnetogenetic methods, facilitate the opening of ion channels during stimulation, allowing ions to enter neuronal cells and induce excitation or inhibition. MNP-mediated neuromodulation offers non-invasive access to deep brain regions with high specificity, providing insights into neural circuits, motor behaviors, and potential treatments for neuropsychiatric disorders. Despite progress, MNP-mediated neuromodulation is at an early stage and requires further refinement to advance applications in neuroscience and move toward clinical trials, as emphasized by the authors.

Tissue engineering (TE) replaces the diseased or damaged tissue that cannot be treated by conventional therapies, with MNPs emerging as a crucial component of the TE toolkit. In section 11, the authors discussed MNPs’ role in steering the growth and alignment of cells and tissues, as well as their ability to initiate mechanotransduction across various cell types by MNP-induced movement. Simultaneously, with magnetic imaging techniques like MRI and MPI, MNPs offer a non-invasive means of imaging and monitoring the integration of engineered tissue constructs. Despite these advancements, challenges in utilizing MNPs for regenerative TE persist, including concerns about biosafety, the spatial distribution of magnetic fields, and the precise repair and regeneration of functional tissues containing multiple cell types arranged in the correct sequence.

MNPs’ intrinsic magnetic properties, which make them responsive to external magnetic fields, are crucial for targeted drug and gene delivery, especially in deep body locations like the brain. Section 12 discusses the development of MNP assemblies, polymers, liposomes, and silane coupling agents as drug carriers, demonstrating the potential for controlled and targeted release, especially in cancer therapy. The creation of magnetically engineered drug delivery systems (MEDDS) that integrate MNPs with other materials is essential to facilitate selective and conditional drug release, ensuring targeted treatment with minimal harm to healthy cells.

As the interest in MNPs for in vivo applications intensifies, it is important to understand the cellular uptake mechanisms of MNPs to enhance delivery efficacy to target cells and prevent clearance by the immune system. Section 13 discussed diverse endocytic pathways through which MNPs enter cells. The physicochemical properties of MNPs influence both their cellular uptake and degradation rate. For instance, smaller MNPs degrade faster due to their higher surface area-to-volume ratio. Additionally, multicore MNPs exhibit a faster degradation rate compared to core-shell multicore MNPs. Upon entering cells, understanding the effect of MNP degradation on their therapeutic and diagnostic potential becomes pivotal. Researchers strive to precisely locate and quantify MNPs, identifying their degradation products to gain deeper insights into the degradation process and its implications in cancer treatment. While the classical approach to studying MNP endocytosis pathways has certain limitations, novel microscopy techniques provide several options for tracking the internalization and degradation of MNPs at a cellular level.

Kai Wu and Jian-Ping Wang

Editors of the Roadmap on Magnetic Nanoparticles in Nanomedicine

1. Magnetic properties and dynamic magnetizations of MNPs

Niranjan A Natekar1 and Kai Wu2

1 Western Digital Corporation, San Jose, CA, United States of America

2 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States of America

Status

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) refer to particles with a magnetic core size of up to 100 nm. MNPs find applications in several areas including information and energy storage, magnetic imaging and biosensors, medical applications, and drug and gene delivery systems. The magnetic properties of MNPs differ from their bulk counterparts. One characteristic of MNPs is their small size and high surface-to-volume ratio. The surface canting effect describes the zeroing of the magnetization due to the canted alignment of spins. In figure 1, atoms inside the spin-ordered portion of the core (with diameter Dm) maintain their magnetizations based on the external field. As the size of the MNP decreases, the saturation magnetization (Ms) of the MNP decreases compared to the bulk value. This reduction is proportional to the difference in core and magnetic diameter of the MNP. The spin canting effect can occur due to (i) the breaking of the crystallographic symmetry at the MNP surface (2) the change in lattice structure at the MNP surface, and (3) the reduced coordination and exchange bonds of atoms at the MNP surface. The effective crystalline anisotropy (Keff) is also affected by the reduction in the MNP size. Equation (1) shows how Keff increases as the MNP core size (D) reduces [1]:

Figure 1.

One MNP with a core diameter of D. The spin-ordered part of the core has a diameter of Dm, with a surface spin disorder in a spin-canted layer of thickness . Original figure prepared by the authors.

The volume component of crystalline anisotropy, Kv, is the energy difference between the default magnetization state and the state in the presence of an external field. The presence of surface anisotropy Ks is valid only when spin-orbit coupling (SOC) and surface anisotropy are strong. Similarly, the cancelation of anisotropy perpendicular to the MNP surface, valid for symmetrical MNP shapes like spheres and cubes makes equation (1) invalid for these shapes. For anisotropic MNPs such as elongated shapes, plate-like shapes, etc, their effective anisotropy is more complicated, readers can refer to this work in [2].

The previous discussions are highly qualitative and primarily focused on the effect of spin canting on the magnetic properties of MNPs in an idealized scenario. Surface coatings of organic or inorganic materials, chemical binding, and other factors can alter this spin canting layer [3, 4]. Additionally, defects in the crystalline structure, annealing history, temperature, and inter-particle interactions also affect the magnetic properties of MNPs. For nanoscale materials, atomic-level to inter-particle level interactions, along with the material’s history, make it difficult to model their magnetic properties accurately. As a result, the reported magnetic properties of MNPs vary widely. For instance, reported magnetic anisotropy values for iron oxide MNPs range from 20 to 100 kJ m−3 [5], and saturation magnetizations vary from 0 to the bulk iron oxide’s value, which is 80–100 Am2 kg−1 [6].

To date, most applications of MNPs are governed by their unique dynamic magnetic properties. Various models have been developed to describe the magnetic behaviors of MNPs, including the earliest Stoner–Wohlfarth (SW) model, Langevin function, Debye model, and Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert (LLG) equation. These models often ignore one or more energy terms or isolate only one of the Néel and Brownian relaxations, which limits their applicability to ideal scenarios and makes them less suitable for real-life applications. In the past 30 years, new models such as the stochastic Langevin [7] and the Fokker–Planck [8], which consider the coupled Néel and Brownian relaxations, have been proposed and shown to be accurate for studying the dynamic magnetizations of MNPs.

Current and future challenges

As mentioned before, the early models such as SW, Langevin, Debye, and LLG equations have their individual shortness. In this roadmap, these models are not elaborated. We will focus on the recent 20–30 yr’ attempts to model the dynamics magnetizations of MNPs. This part starts with the Néel and Brownian relaxation models at equilibrium (see figure 2). These equilibrium relaxations are only valid for DC and slowly varying AC fields and assume both relaxation mechanisms are decoupled.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing representing the zero-field Brownian and Néel relaxations. The dotted line represents the easy axis of the MNP. Original figure prepared by the authors.

Nonequilibrium models are proposed to overcome the limitations associated with the magnetization dynamics of MNPs under rapidly varying AC fields. Which applies to most MNP-based applications nowadays such as hyperthermia, MPI, etc. Based on the Debye model, the empirical Brownian and Néel relaxation models are derived by Yoshida et al [9] and Dieckhoff et al [10] from experimental data fitting. Like the equilibrium models, these empirical models assume the Brownian and Néel relaxations to be decoupled and only one relaxation mechanism dominates at a time.

Later, the Fokker–Planck equation, initially used by Brown [11] to describe the time evolution of the probability density function for the orientation angles of an ensemble of MNPs, has been modified by various groups to study the decoupled Brownian [12, 13] and decoupled Néel [14] relaxations using effective field approximations. Despite these modifications, whether through empirical methods or effective field approximations, the Brownian and Néel relaxations are still treated as independent and decoupled processes. This treatment invalidates these models and their variants for accurately computing the behavior of MNPs in real biological environments.

Advances in science and technology to meet challenges

The models introduced in previous sections define the magnetization dynamics of MNPs with decoupled relaxation mechanisms under restrictions of field profiles. The solution to these limitations is to consider coupled Brownian and Néel relaxations. To counter this limitation, Brownian relaxation is added to the stochastic Langevin and Fokker-Planck equations by considering the orientation dynamics of the easy axis.

For both these formulations, the effective field equation in the model can be solved numerically, but the formulation assumes that the applied field and anisotropy axis are coaxial along the z-axis. In the stochastic Langevin equation, the LLG equation includes the dynamics of the magnetization unit vector direction, , namely, the Néel relaxation. The total energy of the system governs the Brownian relaxation dynamics of the MNP’s with direction specified by (taking the easy axis as reference). The coupled time evolution of both relaxations is expressed as [7, 15, 16]:

where is the gyromagnetic ratio, effective field (a combination of the applied field and other interacting fields), is the LLG damping parameter, is the torque acting on the particle, is the hydrodynamic volume of the particle and is the viscosity of the fluid.

Considering the thermal fluctuations, the total energy and torque can be expressed as:

where is the magnetic core volume of the particle, and refer to the magnetic properties (saturation magnetization and anisotropy, respectively), and is the applied field.

The stochastic simulations based on equations (2)–(4) can be numerically solved to model the coupled Brownian and Néel relaxations of MNP ensembles.

In 2017, Weizenecker derived the Fokker–Planck equation for the coupled Brownian and Néel relaxations, based on the coupled Langevin equations (equations (5) and (6)). The uniaxial anisotropy and magnetization direction are defined in a spherical coordinate system as shown below, with four degrees of freedom. The coupled Fokker-Planck equation is expressed below [8]:

where and are the unit vectors in the anisotropy and magnetic moment directions, respectively. Both these vectors are represented in the spherical coordinate system based on the angles they make with the coordinate axes. N and U represent the magnitudes in different directions for the anisotropy and moment, respectively.

A change in the particle easy axis direction or a change in the moment will lead to a change in the torque and the resulting angular momentum. The equations of motion for both the direction of the particle and the moment can be written by using the definition of generalized torques that will add friction terms to the Euler–Lagrange function. This results in the system of equations represented by equations (7) and (8) below:

In equations (7) and (8), η is the viscosity of the fluid, is the LLG damping parameter for the magnetic moment, is the vector field, T is the absolute temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant. in equation (7) and in equation (8) are time constants and are defined below in equation (9):

The stochastic torques X and Y related to the Brown rotation and Néel rotation, respectively, and are related as follows:

|

Equations (7) and (8) together possesses four degrees of freedom. Since and are independent, they are expressed in two different spherical coordinate systems. The angles and define the direction of whereas and define the direction of . The following relations stand true for the derivatives of and :

The terms in equations (7) and (8) can be further calculated in terms of the spherical coordinate system within which the variables of the equation are represented. By comparing the pre-factors of the basis vectors from the calculations within equations (7) and (8) to the relations expressed above, we get four coupled equations as shown in equation (13):

For a system of coupled stochastic differential equations with zero mean () and satisfying the Kronecker delta relation ( ), it can be used to derive a stochastic partial differential equation. The drift and diffusion terms for this equation are calculated from the four coupled equations shown above (equation (13)). These drift and diffusion terms are quoted in [16].

), it can be used to derive a stochastic partial differential equation. The drift and diffusion terms for this equation are calculated from the four coupled equations shown above (equation (13)). These drift and diffusion terms are quoted in [16].

Inserting the drift and diffusion terms in the stochastic partial differential equation allows us to get the Fokker Planck equations in the coupled form as shown below in equation (14):

In equation (14), F represents the probability density function (PDF) for an ensemble of MNPs and indicates the distribution of ‘spots’ on a unit sphere where the magnetization points. Additionally, represents the uniaxial anisotropy constant, represents the volume of the magnetic core, and are the same time constants as defined in equation (9), and are the angles made by the easy axis and moment with z-axis respectively while and are the corresponding in-plane angles. Finally, and represent the magnitudes for anisotropy and moment in different directions in the spherical coordinate system.

Concluding remarks

MNPs have applications in several fields of science and medicine, which makes understanding their behaviors imperative in the field of magnetism. The primary characteristic of MNP is their small size and high surface-to-volume ratio, which leads to a spin canting effect that results in a reduction in Ms and an increase in Keff compared to bulk materials. To model the magnetic behavior of MNPs for real-life applications, different models have been established so far. Researchers attempt to explain the static and dynamic magnetization behaviors of MNPs under various magnetic field conditions. The earliest models such as the SW and Langevin model ignore one or more energy terms and decouple the Brownian and Néel relaxations. Subsequent models treat the relaxations as decoupled, which is practically incorrect. The relaxation models under zero, DC, and slowly varying AC fields assume an equilibrium system and one dominant relaxation process. The non-equilibrium models can remove this limitation but cannot account for the coupling of the two relaxations. The Debye model and the empirical relaxation models are valid for low fields away from saturation. The LLG model is known for capturing magnetization dynamics but ignores Brownian relaxation.

The theory proposed by Rosensweig [17] to decouple the Brownian and Néel relaxations, although making the modeling easier, can result in seriously flawed analyses. In the stochastic Langevin model, the coupled equations of Brownian and Néel motions track both the direction of the easy axis of the MNP and the direction of the magnetization simultaneously. By solving the combined differential equations, more accurate dynamic magnetizations of MNPs can be achieved [15]. However, the convergence criteria are not used regularly either and should be included. The Fokker–Planck model is efficient computationally, but it is less flexible (harder to incorporate other effects), and the series truncation used in the derivation makes it necessary to understand the derivation to use it effectively. The result is that very little work has been done using this Fokker–Planck model. In addition, for most biomedical applications of MNPs, nanoparticles are often used in a clustered form for better MPI imaging performance [18], higher bioassay sensitivity [19], improved hyperthermia performance [20], and more. In these scenarios, MNPs in a cluster are subjected not only to external fields and thermal fluctuations but also to dipole-dipole interactions (i.e. magnetic dipole fields). These interactions should be taken into consideration to more accurately model and predict the collective dynamic magnetization behaviors of MNPs in biomedical applications.

Acknowledgments

K W acknowledges the financial support from Texas Tech University through HEF New Faculty Startup, NRUF Start Up, and Core Research Support Fund.

2. From physical and chemical approaches to biological synthesis routes of MNPs

Stefano Ciannella1, Cristina González-Fernández1,2 and Jenifer Gomez-Pastora1

1 Department of Chemical Engineering, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States of America

2 Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain

Status

The groundbreaking evolution of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) in nanomedicine is fundamentally propelled by their unique attributes: a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, chemical stability, dispersibility, magnetophoretic separation capability, low toxicity, and potential for functionalization [21, 22]. MNPs have demonstrated versatility in various biomedical applications [23], including but not limited to MRI, drug delivery, and magnetic hyperthermia for cancer treatment (see figure 3). For these applications, the green synthesis of a variety of nanoparticles has been increasingly investigated as a promising route to mitigate issues associated with conventional physical and chemical methods, such as elevated costs and hazardous byproducts [24, 25]. The historical trajectory of MNP synthesis reflects an ongoing pursuit to enhance their chemical and magnetic properties, as well as investigating cytotoxicity aspects for their medical utility. In this context, synthesis methods play a pivotal role in influencing key tunable features such as shape, size distribution, surface chemistry, and magnetic properties.

Figure 3.

Summary of current applications of MNPs in nanomedicine. Reprinted with permission from [23]. Copyright (2021) American Chemical Society.

The progress in utilizing MNPs in biomedical applications hinges on the techniques employed for synthesizing these nanomaterials. Synthesis methods include physical, chemical, and biological methodologies. Physical methods encompass a wide range of techniques that involve the fractionation of bulk materials (top–down approach) into nanometer-sized particles, with only a few instances of a bottom-up approach in this category (i.e. gas-phase condensation methods). Under the top–down physical methods, ball milling techniques are often employed to produce a variety of nano-sized magnetic and non-magnetic materials. This process unmakes chemical bonds with the kinetic energy of impacting steel balls, resulting in smaller particles with an increase surface-area-to-volume ratio [26]. In contrast, chemical and biological approaches generally adopt bottom–up strategies by assembling atoms/molecules into MNPs [27]. Chemical methods, constituting the majority of currently applied techniques and covered by a vast literature, have proven instrumental in cost-effective MNP production, offering a decent control over shape and size through precise tuning of reaction conditions. Synthetic routes are generally conducted in liquid phase, such as precipitation and co-precipitation techniques, sol–gel, microemulsions, hydrothermal, sonochemical, and polyol methods. For instance, the co-precipitation method, the simplest and oldest chemical approach to MNP synthesis, is based on precipitating precursor materials in a basic aqueous solution. Their resulting physical properties (morphology, size, and dispersion) can be tuned by setting reaction parameters such as the ratio of the precursors, pH, and temperature [28]. Despite their versatility, chemical methods bring along the use of hazardous chemicals in the form of toxic metal precursors, capping agents and stabilizers, along with high temperatures and associated elevated energy comsumption. As an example, chemical synthesis of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles requires temperatures in the range of 600 °C–1200 °C through different conventional methods [29]. In response to this problem, biological methods have gained increasing attention while being acknowledged as eco-friendly and less energy-intensive alternatives. Biological methods, rooted in living organisms like microorganisms and plants [30], emerge in this context as environmentally friendly alternatives. Based on the biological substrate, the biological synthesis of MNPs can be classified as microorganism-based and plant-based approaches. Microorganism-based synthesis entails the reduction of metal salts to metal nanoparticles by enzymes and can be carried out extracellularly or intracellularly, while the plant-mediated approach is based on the reduction of metal ions to nanoparticles by the bioactive constituents that are present in the plant extract [31]. Biological synthetic approaches have been developed as an effort to develop non-toxic, eco-friendly alternatives for their chemical and physical counterparts. By overcoming drawbacks such as high temperatures, hazardous byproducts, and production costs, biological methods are posed as simple, cost-effective, safe, and environmentally friendly routes for MNP synthesis. Table 1 reports the advantages and disadvantages of several conventional synthesis approaches as well as the main characteristics of the MNPs produced by these manufacturing routes.

Table 1.

| Classification | Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | Co-precipitation | Simple, high yield | Bad shape control, wide size distribution |

| Sol-gel | Simple, controllable particle size and morphology | Long time, use of toxic solvents | |

| Microemulsion | Uniform properties, thermodynamically stable | Low yield | |

| Hydrothermal | Controllable particle size and shape | High pressure and temperature, limitation of reliability and reproducibility | |

|

| |||

| Physical | Ball milling | Large scale production of high purity particles | High energy requirement, long period of milling time |

| Laser ablation | Relatively simple | Challenges with prolong time laser ablation | |

| Ion sputtering | Generation of less impurities than with chemical methods | Challenges with sputtering gas | |

|

| |||

| Biological | Plant-based | Fairly homogeneous particles | Low yield |

| Bacteria-based | Abundant bacteria availability | Low yield, bad shape control | |

Current and future challenges

The green synthesis of MNPs represents a transformative paradigm, yet several pivotal challenges must be addressed to fully unlock its potential in nanomedicine. The main issue perhaps relies on the lack of standardization and further exploration of optimal process conditions. This advancement should not only facilitate comparisons between studies and promote meta-analysis investigations, therefore improving their assessment toward clinical trials, but also address the problem of reproducibility and consistency of physicochemical properties of greenly synthesized MNPs, which is crucial for medical applications since variations in particle composition and size might, for example, hinder their performance in the context of diagnostics and therapy [32]. For example, through photosynthesis (i.e. plant-based), nanoparticles synthesized from different leaf extracts have shown significant size and shape variability, with recent studies reporting issues related to wide-spread size distributions, structural imperfections, and cluster formation, making it difficult to achieve uniformity and limiting the suitability of green technologies for large-scale manufacturing [36]. Another issue that requires more attention is the slow reaction time, low yield, and conversion rates within biological approaches as presented in table 1, which can potentially turn them less attractive and may affect the economy of the process when compared to various chemical synthesis methods [35]. Additionally, research on mammal toxicity and the accumulation of nanoparticles is still limited: the scarcity of reports providing in vivo particle biodistribution and kinetic profiles, essential for regulatory approval, elevates the need for more comprehensive studies. An in-depth exploration of degradation pathways is imperative, given the inadequacy of current in vitro assessments [37, 38]. While some studies have demonstrated promising properties and safety attributes of biologically synthesized MNPs, comprehensive in vivo assessments, and clinical evaluations are pointed out as necessary for establishing the safety and efficacy of MNPs in medical applications. Furthermore, their interaction with living cells can yield both beneficial and detrimental effects. Limitations such as poor drug loading in drug delivery, overdose risks, non-targeted dispersion causing cellular toxicity, and potential blood coagulation necessitate continuous monitoring and advancements to enhance the functionality of MNPs in nanomedicine applications. Overcoming these constraints requires extensive both in vitro and in vivo investigations and optimizing synthesis conditions to achieve decent quality and size control while implementing sustainability-driven technologies. The availability of natural materials is another issue that must be addressed to promote new and innovative biological routes to synthesize metal-based nanoparticles from plant extracts. In this direction, a comprehensive toxicological assessment and the optimization of genetically modified microorganisms are crucial for the production of MNPs [36].

Advances in science and technology to meet challenges

Achieving nanoparticle quality and size control involves advancements in experimental design and characterization techniques. One of the main constraints of green synthesis lies in an inadequate optimization of reaction parameters, or even lack thereof, along with the identification of optimal solvents [37]. In this context, further research efforts are crucial to unravel the intricate impact of different factors on the shape and size of greenly synthesized nanoparticles. These factors include reactant concentration, reaction time, pH, and temperature, to name a few. The understanding of these parameters is essential as they can also influence the polydispersity of the created materials. Additionally, the development of biomaterials derived from plants and microorganisms necessitates further interdisciplinary research combining biology, chemistry, and materials science. Plants and herbs are abundant, safe to handle, and contain numerous primary and secondary water-soluble metabolites such as anthocyanins, tannins, saponins, flavonoids, polyphenols, polypeptides, starches, alkaloids, and terpenoids, which serve as effective chemical reducers and stabilizers, as well as capping agents [24, 36, 39]. Exploring natural resources involves identifying new plant extracts or biological sources (bacteria, fungi, algae, etc) with optimal properties for the green synthesis of MNPs. Associated issues with the production of greenly synthesized MNPs like poor stability, dispersity, and oxidization, which altogether might also curb their applicability in biomedical and therapeutic fields, can be mitigated by including appropriate surface coatings [40]. Figure 4 provides a summary of the most common types of surface coatings used on MNPs to improve their stability and biocompatibility.

Figure 4.

Types of surface coatings commonly used on MNPs and some examples of each sort. Adapted from [33]. CC BY 4.0.

Regarding metal nanoparticles, challenges associated with clinical and diagnostic applications demonstrate the need for advancements in benchmarking their physicochemical properties and in vitro/in vivo evaluation techniques. Advanced research on surface modification is currently pointed out as a promising approach to broaden the applicability of metal-based MNPs in nanomedicine [41]. In combination with the previously pointed advancement pathways, improved in vitro and in vivo evaluation methods cannot be stressed enough and are essential for assessing nanotoxicity, therapeutic efficiency, and biodistribution. Furthermore, it is imperative to gain a comprehensive understanding of the biochemical mechanisms underlying the green synthesis of iron-based nanoparticles. While some studies suggest that biologically synthesized nanoparticles exhibit lower toxicity [41], conducting risk assessment studies is crucial to ensure the safety, economic viability, and environmental friendliness of the process.

Concluding remarks

The green and sustainable synthesis of MNPs is emerging not only as a necessary change of paradigm but also as a cost-effective, safer, and environmentally friendly alternative to conventional chemical and physical synthesis methods, which tend to employ hazardous chemical species and lack an accurate control over shape and size of MNPs, respectively. Various MNP formulations are undergoing clinical testing, suggesting potential acceptance in clinical settings in the near future. However, the current main challenges in their green, sustainable synthesis lie in the standardization of biological synthesis methods, optimization of process conditions, benchmarking physicochemical properties, and comprehensive in vitro and in vivo toxicological assessments. It is desirable to achieve magnetically active nanoparticles with defined and consistent properties using sustainable and less pollutant methods. Addressing issues such as variability in particle properties and biocompatibility concerns hold the potential to pave the way for MNPs to achieve reliable performance in diagnostics and therapeutics. In this context, surface modification and advanced evaluation methods hold promise for expanding the applicability of MNPs in nanomedicine.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by Texas Tech University through HEF New Faculty Startup, NRUF Start Up, and Core Research Support Fund. Dr Cristina González-Fernández thanks the Spanish Ministry of Universities for the Margarita Salas postdoctoral fellowship (Grants for the requalification of the Spanish university system for 2021–2023, University of Cantabria), funded by the European Union-NextGenerationEU.

3. Surface functionalization on MNPs

Yuping Bao

Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, United States of America

Status

Surface functionalization is one of the most critical aspects of MNPs that not only directly influence their physical and chemical properties [42] but also define their potential applications [43]. Numerous surface functionalization strategies have been established [44] where the specific factors impacting the magnetic property and application of MNPs were elucidated, including anchor groups on the MNP surface, chain property of the capping molecules, coverage on the MNP surface, extruding functional groups from the MNP surface, and conjugation of specific targeting molecules (see figure 5). Typically, functionalized MNPs are illustrated in figure 5 with various surface functionalities.

Figure 5.

Illustration of functionalized MNPs from various strategies. Original figure prepared by the author.

Linker chemistry [45] is one of the most common methods for the surface functionalization of MNPs, with carbodiimide (EDC) [46, 47] and N-hydroxyl succinimide (NHS) ester [48] being the most common linkers. The EDC/NHS conjugation links carboxylic and amino groups. Therefore, this technique only applies to molecules with carboxylic and amino groups. In addition, the reaction requires specific conditions, such as acidic conditions (pH 4.5–5.5) for EDC, pH 7.2–8.0 and 4 °C for NHS. Furthermore, the uncontrolled reactions between amine and carboxylic groups lead to concerns about conjugation efficiency and specificity [49, 50]. As for maleimide linker conjugation [51], maleimides form stable thioether bonds with sulfhydryl groups an alkylation reaction. The reaction takes place rather rapidly in the pH range of 6.5–7.5 [52]. However, this liker conjugation only applies to molecules with thiol groups. In addition, at higher pH, maleimide tends to undergo hydrolysis, and interaction with amine groups occurs [52].

Besides linker chemistry, certain surface coating of MNPs can be activated for conjugation such as polydopamine coating. Polydopamine surfaces can be readily activated at basic pH (>8.5) and subsequently react with amine or thiol groups of the conjugating molecules [53, 54].

Additionally, conjugation based on specific molecular recognition is another common strategy, such as enzyme-substrate [55, 56], antibody and antigen [57], and streptavidin-biotin [58]. Here, both enzyme and antibody conjugation are for very specific targets, while streptavidin-biotin is routinely used [59]. Despite the advantage of specificity, biotin-streptavidin interaction requires prior attachment of biotin or streptavidin on MNPs. The biotin-labeled nanoparticles will react with any biotin-binding proteins, reducing the specificity. On the other hand, streptavidin-labeled MNPs have four binding sites on each streptavidin, which leads to uncontrolled attachment of biotin-labeled analyses [60]. In addition, biotin is a natural biological molecule, causing a big concern about the specificity and background effects when involving biotin-rich tissues and extracts.

Recently, surface functionalization of MNPs with biomimetic membranes has become very attractive, including cell membrane [61–64] and extracellular vehicles (EVs) [65]. Here, the cell membrane carries certain properties of the original cells, allowing for desirable functions. Such as tumor targeting for cancer cell membrane-coated nanoparticles [62]. For EVs, MNPs can be loaded into EVs in situ during EV generation from cells through MNP treatment or be incorporated post-EV isolation [65, 66]. Compared to cell-membrane coating, the key advantages of EV coatings are cell communication [67] and the ability to cross biological barriers [68].

Beyond colloidal stability against aggregation and biocompatibility, surface functionalization greatly influences the interactions of MNPs with biological systems, such as cellular uptake behaviors for cell-based therapy. For example, the surface capping molecules directly affected cell labeling efficiency and cellular tracking duration [69]. The advancement in the surface functionalization of MNPs has enabled the potential of MNPs as imaging probes, for drug delivery, and theranostic applications. The emerging application of MNPs in cell-based therapy is also moving forward with an increasing number of studies in pre-clinical and clinical settings [70]. Specific surface functionalization strategies of MNPs also made direct cell interactions [71] or in situ cell labeling [72] possible. Regardless of the types of applications in nanomedicine, surface functionalization of MNPs has been playing a critical role with well-established protocols to achieve desirable properties. Thus, the surface functionalization of MNPs is evolving into a mature field.

Current and future challenges

The surface functionalization of MNPs still faces several unmet challenges despite the development of numerous strategies. First, standardized characterization and quantification methods are still lacking. Most of the surface functionalization techniques were validated by the presence of certain functional groups and indirectly quantified by the free ligands pre- and post-functionalization. However, the exact number of capping/targeting molecules is normally not provided. For large targeting molecules (e.g. proteins), the orientation of the molecules is also critical for targeting efficiency, which is normally disregarded. The lack of standardized characterization techniques also makes the scalable and reproducible preparation of functionalized MNPs and cross-comparison of similar studies impractical, yielding contradictory results or large discrepancies in findings. Second, in vivo immune clearance of MNPs remains an unresolved issue regardless of surface functionalization. The elongated blood circulation has been achieved by using PEGlyation or zwitterionic polymers, but the MNPs still ultimately accumulate dominantly inside immune organs (e.g. liver and spleen). Third, surface conjugation strategies have been primarily on using targeting molecules to direct MNPs to bypass biological barriers, such as the blood-brain barrier. However, the efficiency has been inconsistent or insufficient to achieve clinical outcomes. Finally, the long-term stability and potential health risk of functionalized MNPs continue to be a concern from the degradation of the MNP core to the surface capping molecules along with their corresponding degraded small compounds. Therefore, efforts must be continuously made to achieve better quality control of functionalized MNPs, standardized protocols for scalable and reproducible production of functionalized MNPs, and effective quantification with predictable outcomes to ensure clinical translation of functionalized MNPs.

Advances in science and technology to meet challenges

The advancement in surface functionalization of MNPs has been witnessed by various aspects, including the capability of loading multifunctional drugs for drug delivery, directed localization for imaging and therapy with targeting molecules, stimulus-responsive ligands for on-demand release of cargos, and biomimetic coatings to overcome biological barriers. Particularly, MNPs functionalized with lipid membrane coatings (e.g. cell membranes or extracellular vesicles) have demonstrated effectiveness in overcoming issues associated with chemical molecule coatings, such as enhanced tumor targeting and brain delivery. However, the functionalization of MNPs with biomimetic membranes is generally hindered by the reproducible and scalable production of quality membranes. Recently, much attention has been drawn to integrating artificial intelligence and machine learning into surface functionalization of MNPs [73]. These computer-assisted tools have the capability of analyzing massive amounts of available data with the potential of identifying the optimal surface functionalization strategy for a desirable application. Because of the capability of processing a whole body of comprehensive data, the standardization of surface functionalization protocols may become feasible, significantly accelerating the design and implementation of surface functionalization of MNPs. In particular, these computational tools will make the comparison of numerous in vitro and in vivo studies feasible, generating relevant pharmacological datasets for clinical translation. However, the success of artificial intelligence and machine learning heavily relies on the availability of a large volume of high‐quality data to validate the computational and mathematical models. Valid experimental conditions and system designs are crucial to capture the dynamic nature and complexity of biological systems. Only models that are fully validated with a large amount of quality and relevant data may offer predictive guidance in the new design of surface functionalization. Therefore, the incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning methods is anticipated to address some of the current and future challenges, facilitating better and more effective surface functionalization of MNPs and accelerating clinical translation of functionalized MNPs.

Concluding remarks

The surface functionalization has enabled MNPs’ promises in various areas of nanomedicine, such as drug delivery, cell-based imaging, and therapy, magnetically responsive soft robotics, and lab on a chip. In the last decade, advances have been made with possibilities to achieve enhanced biocompatibility, minimal opsonization, precise targeting, and single-cell sensitivity in imaging and diagnosis. Regardless of in vivo or in vitro applications, the key limitation for surface functionalization of MNPs is the lack of standardized characterization techniques, qualification strategies, and reproducibility across studies. Much work still needs to be done to fully realize the potential of functionalized MNPs. One promising strategy is the integration of multidisciplinary approaches with the assistance of computational and mathematical models. The future focus needs to be on the reproducibility, scalability, and quantification feasibility of different functionalization approaches, enabling MNPs to reach a level of consistency for clinical or commercial use.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by NSF-CBET1915873 and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation of Alabama.

4. Characterization methods for MNPs

Jinming Liu1, Shuang Liang2, Kai Wu3 and Jian-Ping Wang4

1 Western Digital Corporation, San Jose, CA, United States of America

2 Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States of America

3 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States of America

4 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States of America

Status

Characterization is the first step to evaluate the inherent properties of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) to meet the requirements of various biomedical applications [74]. Many characterization techniques have been applied to obtain information on MNPs such as their size and morphology, structure and composition, colloidal stability, magnetic properties, etc. MNPs for biomedical applications are usually composed of an inorganic magnetic core and an organic shell. The size and shape of the magnetic core determine its magnetic properties and applications. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is commonly used to characterize the core size, shape, and internal structures. TEM obtains two-dimensional projections of MNPs. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is also used to obtain the size, shape, and three-dimensional images. X-ray diffraction (XRD) can estimate the size using Scherrer’s equation. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) is an essential technique to obtain hydrodynamic size and distributions of MNPs in solutions.

Compositions of MNPs are generally characterized by energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detecting all elements. Electron energy loss spectra (EELS) is another approach to obtaining elemental compositions, which has a better signal-to-noise ratio, improved spatial and energy resolution, and enhanced sensitivity to elements with lower atomic numbers. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can provide composition and binding states on the surface of a sample (several nanometres). The structural information of MNPs is critical. For example, even though α-Fe2O3 and γ-Fe2O3 have similar compositions, their magnetic properties are quite different. XRD is a common way to determine structural information. High-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) can also measure structures from images and electron diffractions. Fourier transform-infrared (FT-IR) characterizes bonding between MNPs and organic shells, binding energy, and oxidation states.

Due to the surface canting effect, the magnetic properties of MNPs differ from their bulk materials [27]. Vibrating-sample magnetometer (VSM) is frequently used to characterize the magnetic properties of dried MNPs. Where a sample placed in a coil is subjected to a constant applied field. A voltage signal is generated in the coil by vibrating the sample according to Faraday’s law. Thus, the M-H curves are obtained, which provide information like coercivity, remanence, saturation fields, saturation magnetization, etc. A superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) is another choice that provides better sensitivity over a VSM.

Current and future challenges

Characterizing MNPs is crucial for diverse biomedical applications, yet certain characterization techniques pose challenges that require careful consideration. Take TEM as an example, it is a potent method to measure the sizes and shapes of MNPs. Due to the limitation of sample sizes, only a small fraction of samples can be characterized, necessitating considerable effort to secure a truly representative sample for comprehensive TEM analysis. MNPs may generate an external field deflecting TEM’s electron beams, requiring secure sample fixation and the astigmatism of the objective lens needs to be carefully adjusted for clear imaging. High-energy electron beams in TEM may heat up and damage MNPs of interest, especially when characterizing a single nanoparticle. Comparable constraints also extend to other electron microscopic technologies, including SEM. Meanwhile, due to the high vacuum in TEM, dried MNP samples are generally used. More advanced techniques are needed to characterize MNPs in a solution. XRD can only estimate the average size of MNPs according to Scherrer’s equation, lacking size distribution information. If MNPs exhibit an amorphous structure or are extremely small, it becomes challenging to identify a diffraction peak to determine their average size. DLS quantifies the hydrodynamic size distribution of MNPs. It is highly responsive to MNP aggregations, necessitating careful consideration of MNP concentration. The transparency of the DLS media is crucial for optimal light scattering. Additionally, the determination of the average radius of MNPs assumes a perfectly spherical shape, a condition difficult to attain in practical scenarios. Irregularities in the shape of MNPs can lead to measurement errors. The assessment of MNPs’ colloidal stability often involves measuring their Zeta potential. However, obtaining accurate measurements is challenging due to the susceptibility of Zeta potential to various extrinsic factors, such as concentrations and the composition of the solvent.

VSM and SQUID provide bulk magnetic property data for characterization, but individual particles may exhibit variations. Dried MNP samples must be securely fixed on a holder to prevent physical rotation, such as Brownian relaxation. Consequently, VSM and SQUID analyze Néel relaxations in the magnetizations of MNPs under diverse excitation fields.

Advances in science and technology to meet challenges

Scientists have devoted substantial efforts to addressing characterization challenges. The conventional use of high vacuum in TEM makes direct characterization of MNPs in liquid solutions or biological matrices challenging. Cryogenic TEM (cryo-TEM) has been developed to maintain samples at near liquid nitrogen temperatures, preserving the structure of MNPs in solutions and facilitating TEM imaging [75–77]. Cryo-TEM has proven valuable in observing various phenomena, including the nucleation and growth of particles, the formation mechanism of magnetic meso-crystals, and changes in agglomeration state when particles interact with cells. Mirabello et al explored the behavior of Fe3O4 aggregates using cry-TEM. They observed that ferrous hydroxide precursors, initially with a primary particle size of approximately 5 nm, aggregated into Fe3O4 primary crystals around 10 nm. The primary crystals then formed orientated and uniform mesocrystals, exhibiting diffraction patterns similar to those of single crystals [75].

Liquid cell TEM is also developed to preserve the liquid state and carry in-situ imaging of liquid phases with particles, which benefits the understanding of how particles perform in a liquid phase [78, 79]. Liquid samples are sealed in a small cell, which is generally made by microelectronic fabrication on silicon wafers. Samples are sealed by electron-transparent windows, such as SiN. Graphene and thin amorphous carbon film have also been used to preserve volatile samples like biological cells, under the high vacuum in TEM. Liquid cell TEM has many applications such as the in-situ growth of nanoparticles (e.g. Cu, Pt, iron oxyhydroxide, etc), core@shell structures (e.g. Au@Pd, Fe3Pt@Fe2O3, PtNi@Ni, etc), and the movement and interaction of nanoparticles. Powers et al studied the dynamic interaction of Pt-Fe nanoparticles during the assembly process using a liquid cell TEM [80]. Initially, 2D loosely packed nanoparticles were observed, which then transformed into 1D chains, and eventually formed 2D lattices over time.

Scanning SQUID biosusceptometry is developed to detect MNPs with low concentration in both ex vivo and in vivo [81]. It has a pickup coil close to the samples. The signal from a pickup coil is amplified and transferred to a SQUID sensor. A sub-millimeter spatial sensitivity could be achieved when detecting MNP-labeled tumors. MNP imaging in rat liver and heart in both in vivo and ex vivo was reported. A 0.1 attomole sensitivity was also demonstrated by integrating a microfluidic array into a scanning SQUID. Even a single MNP can be detected [82].

A recent technique, magnetic particle spectroscopy (MPS), has emerged for characterizing the magnetization dynamics of MNPs in liquid, encompassing coupled Brownian and Néel relaxations [83]. This MPS technique is used for evaluating the suitability of MNPs as tracers for MPI applications. In the MPS characterization process, an ensemble of MNPs suspended in a solution is subjected to a sinusoidal magnetic field, also known as the drive field or excitation field, with a frequency denoted as f. This field periodically saturates the magnetizations of the MNPs, generating higher harmonics at 3f, 5f, 7f, and so forth, due to the nonlinear responses of their magnetizations. These higher odd harmonics result from coupled Brownian and Néel relaxations, and their manifestation is mitigated by thermal fluctuations. The intrinsic magnetic properties of the MNPs, including relaxation time [84], saturation magnetization, anisotropy, magnetic core size, hydrodynamic size, as well as the viscosity and temperature of the solution [85], influence the characteristics of these higher harmonics.

Concluding remarks

This section presented basic characterization techniques of MNPs for biomedical applications. One may pick up the right techniques to best describe MNPs for specific applications. Essential techniques need to be considered such as representative samples for TEM to obtain size, shape, composition, and structural information on a sufficient number of MNPs. As there are challenges and limitations of some characterization techniques, several techniques may be used together to get comprehensive information. For example, XRD only provides average size information of MNPs, but TEM can help obtain size distribution, and DLS provides the hydrodynamic radius of MNPs. By combining all this information, one would have a more comprehensive idea about the size and size distribution of MNPs. It will also help in understanding other properties. Several advanced techniques aimed at addressing the challenges should also be considered as options to obtain more comprehensive information on samples.

Acknowledgments

K W acknowledges the financial support from Texas Tech University through HEF New Faculty Startup, NRUF Start Up, and Core Research Support Fund. J-P W acknowledges the financial support from the Institute of Engineering in Medicine and the Robert F Hartmann Endowed Chair professorship by the University of Minnesota.

5. Magnetic separation for sample enrichment

Xian Wu1, Linh Nguyen T Tran2, Karla Mercedes Paz González2, Hyeon Choe1, Jacob Strayer1, Poornima Ramesh Iyer1, Jeffrey Chalmers1 and Jenifer Gomez-Pastora2

1 William G Lowrie Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States of America

2 Department of Chemical Engineering, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States of America

Status

Magnetic separation has emerged as an advanced technology, gaining increasing attention in recent years within the fields of biomedicine and biology. The separation of biological materials from biofluids, such as uncommon cellular entities, pathogens, and other biomolecules, plays a pivotal role in diverse biomedical fields, including diagnostic modalities, therapeutic interventions, and foundational investigations in cellular biology. Comprehending the complexities associated with cellular dynamics often requires extracting and enriching distinct cell subsets and/or their components before their analysis, aiming to mitigate the inherent diversity within the scrutinized specimen. Instances of cell populations of interest involve but are not limited to, stem cells, circulating tumor cells (CTCs), cancer stem cells, and subpopulations of white blood cells (WBCs). The magnetic enrichment process of these cell types encompasses either the utilization of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) as magnetic labels for the separation of diamagnetic (non-magnetic) cells or label-free systems for the separation of paramagnetic cell types. Labeled magnetic separations commonly involve the deployment of MNPs, such as magnetite or maghemite, within the size range of 1–100 nm [86, 87]. These MNPs exhibit distinctive physical and chemical characteristics, augmented magnetization, and recent advances in MNP synthesis facilitate the binding of functionalizable ligands to their surface. Additionally, under small sizes, their superparamagnetic attributes enable facile manipulation through external magnetic fields. Unlike traditional labeled-based methodologies, there is a growing interest in label-free separation approaches that aspire to isolate disease-related entities without the necessity of supplementary labeling agents [88]. These label-free methodologies capitalize on the target entities’ inherent magnetic properties to achieve specific and efficient separation.

Current and future challenges

Magnetic enrichment is a complex process influenced by various factors and forces that govern the behavior of materials when subjected to an external magnetic field. These forces encompass the magnetic force, gravitational force, viscous drag, buoyancy, inertia, particle-fluid interaction, Brownian motion, as well as inter-particle phenomena that include magnetic dipole interactions and Van der Waals forces [89]. The application of magnetophoresis has proven to be effective in driving sample enrichment of several bio-entities, utilizing both high gradient magnetic separation (HGMS) columns and low gradient magnetic separation (LGMS) systems [90]. HGMS typically involves the use of packed columns of ferromagnetic materials to capture specific entities (figure 6(a)). The column packing comprises wires with diameters of approximately 50 μm, with gap distances ranging from 10 μm to 100 μm (figure 6(b)) [89]. Once the column is magnetized by an external magnetic field, the target entities (labeled cells or paramagnetic biomaterials) flow through the column and get effectively trapped on the packing surface. HGMS offers advantages, such as the ability to generate exceptionally high magnetic gradients, resulting in elevated magnetic forces acting on the entities (figure 6(c)). However, some existing drawbacks include the generation of inhomogeneous magnetic fields and gradients due to the irregular packing material, which complicates the description of the process. In addition, HGMS may lack specificity in capturing only the magnetic particles or cells, leading to potential contamination from non-magnetic entities inadvertently trapped by the magnetic matrix. The most well-known HGMS system for cell separation is the MACS (Magnetic Activated Cell Sorting) developed by Miltenyi Biotec [91].

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic diagram of the HGMS process. (b) Three possible configurations of the rod matrix in HGMS systems. (c) Effect of the rod diameter on the magnetic field distribution in HGMS matrices. Reprinted from [92], Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.

To overcome the limitations of HGMS, research efforts in magnetic separation have focused on the development of LGMS [90]. LGMS provides a cost-effective alternative capable of achieving separation of target entities using external magnetic field gradients typically on the order of <100 T m−1. An LGMS setup includes one permanent magnet or an arrangement of them to provide the magnetic fields and gradients required for separation. Unlike HGMS, LGMS does not require specialized, pre-packed columns, significantly reducing installation and operational costs, minimizing contamination due to mechanical filtration of non-magnetic particles/biomaterial, and allowing the separation process to be continuous [93]. LGMS systems utilize permanent magnet arrays to generate stable and reproducible magnetic gradients, allowing for simpler setups, easier description, modeling, and scale-up of separation processes. For large-scale processes (generally within water treatment applications), the operational cost of LGMS is notably lower, by approximately four-fold as compared to HGMS, $0.13/m3 of sample treated versus $0.52/m3 respectively, due to lower energy requirements and the absence of complex electromagnets and matrices [94]. Despite its cost-effectiveness, LGMS faces serious challenges in the separation of small particles or weak magnetic materials due to the low magnetic field gradients generated in the system, rendering it unable to isolate entities in a reasonable amount of time. Indeed, the process often requires extended periods of magnetic exposure, ranging from several hours to days, depending on entity size and concentration [95]. Nevertheless, the development of novel devices based on quadrupole magnet arrangements has shown to be promising for the separation and magnetic enrichment of small nanosized particles in a matter of minutes [96–98] and paramagnetic cells and biomolecules in a continuous-flow operation mode [99]. Figure 7(a) presents a quadrupole magnetic sorter that uses permanent magnets to separate and enrich magnetic materials.

Figure 7.

(a) Quadrupole magnetic sorter for magnetic particle separation. (b) Top view of the steel pole pieces (purple) and NdFeB magnets (yellow). (c) Cross-sectional field map. Reprinted from [98], Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier.

Advances in science and technology to meet challenges

In the pursuit of increasing the separation efficacy and expanding the applicability of HGMS systems, significant investigations have focused on the optimization of matrices, packing materials, and geometries within these separators (figure 6(b)). The fabrication of magnetic matrix/packing materials has involved the utilization of substances characterized by heightened permeability, augmented corrosion resistance, and superior abrasion resistance [92]. Additionally, the optimization of packing geometries has been systematically undertaken to mitigate fluidic impedance and amplify the capture area per unit volume, thereby enhancing the overall collection efficiency. Moreover, labeled separations have been and continue to be optimized by developing novel MNPs. This optimization includes engineering the material composition to augment saturation magnetization, consequently elevating both the magnetic force acting on the material as well as the local field gradient generated by the MNPs. Furthermore, in magnetophoresis, the geometry and arrangement of magnets influence the magnetic field gradient and its distribution within the separator volume, which are pivotal factors for improving the device’s performance. As shown in figure 7(b), a quadrupole geometry involving the arrangement of four permanent magnets has been employed to establish regions with extremely high field gradients in the order of >1000 T m−1 within the device. Finally, numerical simulations have proven to be very useful to comprehensively understand the inherent mechanisms of magnetophoresis and important parameters governing the magnetic separation process. Recent works have addressed the utility of numerical models to design and optimize magnetophoretic devices [100]. These models comprise a set of equations that describe the forces acting on magnetic materials (particles, cells, magnetically labeled biomaterials), mainly the magnetic force and fluidic drag force, and predict the magnetic material motion within the device as a function of the balance of these forces. These computational models are crafted to design separation devices and facilitate the exploration of pertinent process parameters, thus performing process optimization. Additionally, these numerical models can be used to explain experimental phenomena, thereby helping the experimental design [101]. Notably, the simulations can be employed to study the separation process within the device, encompassing predictions regarding the trajectory of the material and the capturing regions inside the separator [102]. Furthermore, the simulations are instrumental in analyzing the impact of factors such as magnetic field gradient (figure 7(c)), MNP size and concentration, sample flow rate, and enrichment performance.

Concluding remarks

Magnetic separation tools have garnered growing interest across diverse domains, particularly in sample enrichment applications in biomedical fields. Indeed, this technology is particularly useful for rare cell isolation processes, such as the recovery and analysis of cancer cells for early diagnosis. Magnetic separation methods can be broadly classified into two categories: labeled-based techniques and label-free magnetophoresis. Labeled magnetic separation primarily involves utilizing MNPs, such as magnetite or maghemite, to confer magnetic properties to the target entity (a diamagnetic material). Concurrently, there is a rising interest in the label-free separation of biological materials, aiming to enrich samples based on their weak paramagnetic moments without relying on additional labeling agents. Nevertheless, these technologies face several challenges that need to be overcome to exploit the full potential of magnetophoresis. In this chapter, we have highlighted the most critical issues that both high-gradient and low-gradient magnetic separation filters need to solve to increase separation performance (recovery and purity) and throughput, as well as recent advances in the field of magnetic separation.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Texas Tech University through HEF New Faculty Startup, NRUF Startup, and Core Research Support Fund. We also wish to thank the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1R01HL131720-01A1) and DARPA (BAA07-21) for financial assistance.

The authors wish to thank Dr Ioannis H Karampelas for their valuable contributions and input to this contribution of the roadmap.

6. MNP-based bioassays

Vinit Kumar Chugh1, Shuang Liang2, Kai Wu3 and Jian-Ping Wang1

1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States of America

2 Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States of America

3 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States of America

Status

Given the nonmagnetic properties of most biological samples, using magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) as labels for detecting biological target analytes provides the inherent benefit of minimal background noise and, consequently, improved detection limits compared to similar chemical or optical labels. This distinctive characteristic has rendered MNPs a focal point of extensive utilization and investigation within the realm of detection.

To specifically identify and establish a quantitative relationship between biological target analytes and MNP labels, distinct bioassays based on MNPs have been developed. Depending on the nature of the target analytes, the bioassays can be categorized into protein-based and DNA-based bioassays. The protein-based assays can further be divided into (a) direct bioassay, (b) indirect bioassay, (c) sandwich bioassay, and (d) competitive bioassay. In the case of a direct bioassay approach (figure 8(A1)), target analytes bind directly to MNP-labeled detection probes. This method is simple but less sensitive thus suitable only for abundant molecules. For increased sensitivity, an indirect bioassay approach is used (figure 8(A2)), where target analytes bind to primary detection probes, and these probes are then attached to MNP-labeled secondary probes. The sandwich assays (figure 8(A3)) further improve sensitivity by employing a capture probe on the device’s surface, binding to target analytes, which then attach to MNP-labeled detection probes. However, this method requires at least two binding sites on the target analytes, limiting its use for small molecule detection. Alternatively, the competitive bioassay approach (figure 8(A4)) is utilized, where labeled and unlabeled probes or target analytes compete for limited binding sites. When the target analytes are DNA fragments, a DNA-based bioassay can be established by immobilizing probe DNA on the sensor’s surface. Subsequently, the probe DNA can bind to MNP-labeled target DNA fragments (figure 8(A5)). In one example, de Olazarra et al [103] demonstrated the establishment of a DNA-based bioassay using MNPs as labels on giant magnetoresistance (GMR) biosensors for gene expression diagnostics. Initially, mRNA was isolated and reverse-transcribed to produce cDNA. Then a PCR reaction generated biotinylated amplicons, followed by denaturation to obtain single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) as the target. The ssDNA was then hybridized with a complementary probe immobilized on the GMR sensor surface. Post-hybridization, streptavidin-coated MNPs were bound to the biotinylated ssDNA, facilitating quantification of the target DNA.

Figure 8.

(A) Schematic drawing of various MNP-based bioassays. (A1) Direct assay. (A2) Indirect assay. (A3) Sandwich assay. (A4) Compactivity assay: limited number of probes (left) and limited number of target analytes (right). (A5) DNA assay. (B) Schematic representations of (B1) Néel relaxation and (B2) Brownian relaxation. Original figure prepared by the authors.