Abstract

Vascular calcification, a common complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD), remains an unmet therapeutic challenge. The trans-differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) into osteoblast-like cells is crucial in the pathogenesis of vascular calcification in CKD. Despite ferroptosis promotes vascular calcification in CKD, the upstream or downstream regulatory mechanisms involved remains unclear. In this study, we aimed to investigate the regulatory mechanism involved in ferroptosis in CKD vascular calcification. Transcriptome sequencing revealed a potential relationship between HDAC9 and ferroptosis in CKD vascular calcification. Subsequently, we observed increased expression of HDAC9 in calcified arteries of patients undergoing hemodialysis and in a rat model of CKD. We further demonstrated that knockout of HDAC9 attenuates osteogenic trans-differentiation and ferroptosis in VSMCs stimulated by high calcium and phosphorus. In addition, RSL3 exacerbated ferroptosis and osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs exposed to high levels of calcium and phosphorus, and these effects were suppressed to some extent by HDAC9 knockout. In summary, our findings suggest that HDAC9 promotes VSMCs osteogenic trans-differentiation involving ferroptosis, providing new insights for the therapy of CKD vascular calcification.

Keywords: HDAC9, ferroptosis, vascular calcification, vascular smooth muscle cell, osteogenic trans-differentiation

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is recognized as a major global issue, with an estimated global prevalence of 9.1% in 2017 [1]. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) constitutes the leading cause of mortality in patients with CKD [2–4]. Numerous studies have highlighted the pivotal role of vascular calcification in CVD among patients with CKD [5–8]. Vascular calcification is an early complication of CKD that worsens with declining renal function. The China Dialysis Calcification Study reported an increase in the overall incidence of vascular calcification from 77.1% at baseline to 90.7% after 4 years, with 86.5% of patients experiencing progression [9]. However, effective therapeutic interventions for vascular calcification remain lacking.

The trans-differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) into osteoblast-like cells is crucial in the pathogenesis of vascular calcification in CKD. This process is characterized by the upregulation of osteogenic markers, notably Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), and the downregulation of contractile phenotypic markers such as smooth muscle 22α (SM22α) [10]. Several factors, including hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, oxidative stress [11], and cell death [12], contribute to driving osteogenic trans-differentiation in VSMCs. However, the specific mechanisms need to be further explored.

Distinguished from autophagy, necrosis, and apoptosis, ferroptosis has unique morphological and biochemical features [13]. Morphologically, autophagy is predominantly characterized by the formation of double-membraned autolysosomes (autophagic vacuoles), whereas ferroptosis does not form the classical closed bilayer membrane structures. Ferroptosis also does not have the characteristics of conventional apoptosis, such as the reduction of cellular volume and nuclear volume, nuclear fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and the formation of apoptotic bodies. Moreover, ferroptosis does not have the typical features of necroptosis, such as rupture of the plasma membrane, generalized swelling of the cytoplasm and organelles, and moderate chromatin condensation. The morphological features of ferroptosis mainly manifests as obvious mitochondrial alterations, including mitochondrial shrinkage, increased mitochondrial membrane density, and rupture or deletion of mitochondrial cristae. Biochemically, increased lysosomal activity and LC3-I to LC3-II conversion are the main features of autophagy. Apoptosis is mainly characterized by the activation of caspases, oligonucleosomes and DNA fragmentation, while necroptosis is mainly characterized by a drop in ATP levels and the activation of receptor interacting kinase-1, receptor interacting kinase-3, and mixed-lineage kinase-like proteins. For ferroptosis, the biochemical features are iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation [13–15]. Several studies have highlighted the role of ferroptosis in the pathogenesis of CVD such as cardiomyopathy [16], heart failure [17], myocardial ischemia [18], and atherosclerosis [19]. Additionally, inhibiting ferroptosis has been shown to attenuate vascular calcification in rat and mouse models of CKD [20]. Despite these findings, the upstream or downstream regulatory mechanisms involved in ferroptosis in the osteogenic trans-differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) remains unclear. In this study, we aimed to investigate the regulatory mechanism involved in ferroptosis in CKD vascular calcification. By understanding these mechanisms, it is expected to provide new strategies for preventing or treating vascular calcification in patients with CKD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and treatment

Rat thoracic aortic VSMCs (A7r5) were obtained from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, 10566016), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, 10099-141 c) and 1% antibiotics (Hyclone, SV30010), and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. To induce osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs, VSMCs were exposed to a medium supplemented with 10 mM β-Glycerophosphate (Sigma, G9422) and 1.5 mM calcium chloride (Solarbio, C7250) for 5 d [21]. Additionally, in certain experiments, VSMCs were treated with 0.5 µM RSL3 (Selleck, S8155). The medium was changed every 2 d.

2.2. Animals and ethical approval

Male Wistar rats (8–10 weeks, 200–300 g) (n = 14) were obtained from DOSSY Laboratory Animals, Ltd. The rats were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with a range of 20 °C–26 °C and humidity maintained at 40%–70%. A 12-h light-dark cycle was maintained for the rats. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (approval no. 2017.36). In addition, our ethical approval of animal experiments complies with ARRIVE guidelines.

2.3. Human subjects

This study involved arterial samples from two individuals. The artery in the control group was obtained from the lower extremity artery of a patient who underwent amputation at our hospital due to severe motor accidents. This patient had normal renal function and no previous medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebral infarction, atherosclerosis, or coronary artery calcification. The artery in the calcified group was obtained from a patient undergoing hemodialysis (HD) at our hospital, and the radial artery was obtained during an arterial-venous fistula surgery. This hemodialysis patient had abdominal aortic calcification confirmed by X-ray, but not history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cerebrovascular disease. Furthermore, neither the patient who underwent amputation nor the patient undergoing hemodialysis had active inflammatory diseases, severe wasting diseases such as cirrhosis, tumors, or severe malnutrition. They also did not receive corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents within six months. All procedures involving human samples were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sichuan People’s Hospital (approval no.2017.36). Written informed consent was obtained from human subjects prior to any procedures of the study.

2.4. Induction of the vascular calcification model in CKD rats

Wistar rats were randomly allocated into two groups: sham group (n = 7) and CKD group (n = 7). The CKD group underwent a 5/6 nephrectomy (Nx) and were fed a high-phosphorus diet (1.2%). The 5/6 Nx was conducted in two stages. Rats were initially anesthetized with 1% sodium pentobarbital (4 mL/kg, intraperitoneal injection) and then analgesically treated with ibuprofen oral suspension (0.25 mL/kg, 1:10 dilution in saline). The surgical site was sterilized using 1% povidone iodine and 75% alcohol. The skin around the left kidney was incised, and the surrounding tissues were separated to expose the kidney. The left kidney was resected after ligation of the renal artery and vein. The incision was sutured, and pain relief was provided with ibuprofen suspension as previously described. Rats were injected intraperitoneally with 0.05 mL of cefazolin sodium once a day for 3 d to prevent infection. One week later, the right kidney was similarly exposed and the upper and lower poles were resected. The sham group, which acted as controls, received a standard diet (0.6% phosphorus) and underwent a sham operation. The sham operation was performed concurrently with the CKD group, involving the exposure and separation of the kidney capsule without resection. After 4 weeks, rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 1% sodium pentobarbital (4 mL/kg) and then euthanized. Aortas were collected for subsequent experiments.

2.5. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing

A model of HDAC9 knockout A7r5 cell line was generated using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering. Initially, guide RNAs (gRNAs) were designed using CCTop the CRISPR/Cas9 Target Online predictor (uni-heidelberg.de). The sequence of the gRNA was CGGACGACAGGATCCACCAC-AGG following an assessment of its cutting efficiency. Subsequently, the gRNA was incubated with CRISPR/Cas9 and delivered into cells via RNP electro transfection. Positive colonies exhibiting frameshift mutations in the cell pool were identified using PCR and Sanger sequencing. The identified colonies were then expanded, and PCR and Sanger sequencing were performed to confirm the establishment of stable HDAC9 knockout cell lines.

2.6. Bioinformatics analysis of GSE146638 data

The dataset GSE146638 was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. In this study, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were defined as genes exhibiting a fold change (FC) > 1.5 with q < 0.001. A heatmap was generated using the ‘pheatmap’ package. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses and visualizations were conducted using the ‘clusterprofiler’ software package. p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

2.7. Nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing

Nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing was conducted on normal rat aortas and calcified aortas from a CKD rat model, following standard procedures provided by Oxford Nanopore Technologies. Total RNA was extracted from rat arteries using the TRIzol reagent. Subsequently, poly-A mRNA was isolated using mRNA capture beads (VAHTS, N401, China) for cDNA library construction, followed by cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification. Sequencing was performed using a PromethION flow cell on a PromethION48 device with MinKNOW version 2.2 software for 72 h.

2.8. Bioinformatics analysis of Nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing

Gene expression levels were quantified using counts per million [22]. Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 software package on the BMKCloud platform (www.biocloud.net), and known gene with |log2 (FC)|>1.5 and false discovery rate (FDR) value < 0.01 were defined as DEGs. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed using the ClusterProfiler software package. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis was conducted using the STRING database, with a significance threshold set at an interaction score > 0.4.

2.9. Alizarin red staining

Artery tissue sections (4 μM) were stained with Alizarin Red S Staining Solution (Solarbio, G3280) for 5 min, rinsed with distilled water, and then sealed with neutral resin. The images of the arterial sections were observed and collected under a microscope, revealing red staining in the calcified regions. VSMCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min before being stained with Alizarin Red S Solution (OriCell, ALIR-10001) for 5 min. After rinsing with distilled water, the VSMCs were imaged using a bright-field microscope, with cells exhibiting calcium deposits characterized by a red coloration.

2.10. Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was conducted using the Opal 4-color IHC kit (Akoya Biosciences, NEL821001KT). Initially, arterial slices were deparaffinized, fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin (NBF), and treated with AR6 solution for antigen retrieval. Following incubation with the antibody dilution/containment solution at room temperature, the blocking solution was removed. The sections were then sequentially incubated with the primary antibody, HRP secondary antibody, and Opal fluorophore. Between staining steps for each antigen, the slices were rinsed twice with an AR6 solution. The primary antibodies used were anti-HDAC9 (1:1000, Abcam, ab109446), anti-RUNX2 (1:200, Abcam, ab236639), and anti-SM22α (1:50, Proteintech, 10493-1-AP). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Subsequently, the sections were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and representative images were collected.

2.11. Transmission electron microscopy

After the indicated treatment, cells cultured on a 100-mm dish were promptly harvested and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min to obtain a cell precipitate. The cell precipitate and arterial tissue were fixed with a TEM fixative (Servicebio, G1102) for 4 h. Subsequently, the cell precipitate and arterial tissue were pre-embedded in 1% agarose solution and further fixed with 1% OsO4 for 2 h. The samples were then dehydrated using a graded ethanol series, followed by embedding in resin and sectioning. These sections were transferred to 150-mesh cuprum grids and stained with 2% uranium acetate in a saturated alcohol solution and 2.6% Lead citrate. Representative images were acquired using a transmission electron microscope (HT7700, Tokyo, Japan).

2.12. Lipid peroxidation measurement

To evaluate lipid peroxidation, cells were subjected to the treatment protocol and subsequently incubated with a 2.5-μM Liperfluo (Dojindo, L248) working solution for 30 min at 37 °C following the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the Liperfluo working solution was removed, and the cells were washed three times with DMEM medium. The nuclei were then stained with DAPI for 10 min, and Prolong Gold antifade reagent was added to mitigate fluorescence quenching. Imaging was conducted using a confocal microscope (ZEISS).

2.13. Measurement of glutathione and glutathione disulfide

The levels of total glutathione (GSH + GSSG) and GSSG were quantified using a commercial GSSG/GSH Quantification Kit II (Dojindo, catalog number G263), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm with a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x; Molecular Devices). The concentrations of GSSG and total glutathione were determined from the standard curves. The calculation for reduced GSH (GSH) was as follows: GSH = Total glutathione (GSH + GSSG) − GSSG × 2.

2.14. Western blot

Cell lysates were prepared by incubating cell samples on ice in RIPA lysis buffer (Biosharp, BL504A) supplemented with 1% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride for 30 min. The proteins were then boiled in loading buffer (Solarbio, P1040) at 100 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, the proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. After blocking with 5% milk for 2 h, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: Goat HDAC9 Rabbit mAb (1:500, Zenbio, Cat# R381443), Goat Anti-Rabbit Runx2 antibody (1:1000, HUABIO, Cat#ET1612-47), Goat Anti-Rabbit SM22α antibody (1:1000, Proteintech, Cat# 10493-1-AP), Goat Anti-Rabbit glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) (1:5000, Abcam, Cat#ab125066), Goat Anti-Rabbit solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) (1:1000, Zenbio, Cat#382036). The next day, the membranes were incubated with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (1:10000, Zen Bio, Cat#511203) for 2 h. Protein expression was detected using an ultrasensitive ECL chemiluminescent substrate (Biosharp, BL523B), and band intensities were semi-quantified using ImageJ software, normalized against beta-actin (8F10) mouse mAb (HRP) (1:10000, Zenbio, Cat#70068).

2.15. Statistical analysis

All data analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM. Normality was assessed via the Shapiro–Wilk test. Differences between groups were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s test for post-hoc comparison. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Ferroptosis manifestation in calcified arteries of patient undergoing hemodialysis and CKD rats

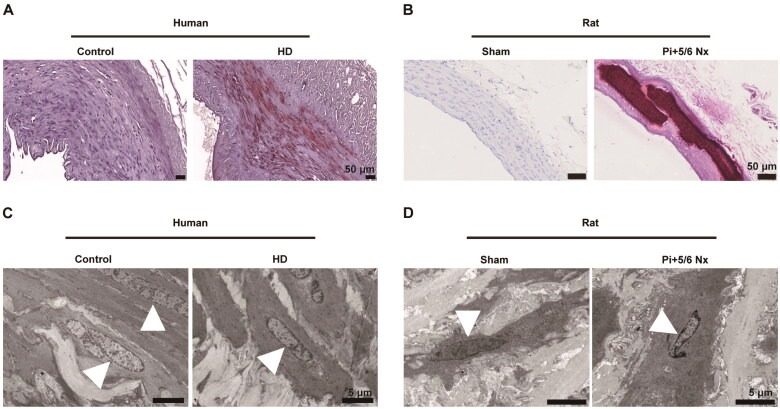

Alizarin Red S staining revealed substantial calcium deposition in the arterial media of patient with hemodialysis and CKD rat models, compared to the control group (Figure 1A,B). Transmission electron microscopy highlighted significant morphological alterations in mitochondria under conditions of vascular calcification, including decreased volume, membrane disruption, and increased membrane density (Figure 1C,D). These findings suggest the occurrence of ferroptosis in the context of CKD vascular calcification.

Figure 1.

Ferroptosis occurs in the calcified arteries of patient with hemodialysis and rats subjected to 5/6 nephrectomy and a high-phosphorus diet. (A) Representative alizarin red staining of human arterial sections from control and patient with hemodialysis (HD). Calcified areas were visualized by red staining. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Representative alizarin red staining of the aorta in rats receiving a sham operation or 5/6 nephrectomy (5/6 Nx) and a high-phosphorus diet. Scale bars, 50 μm. (C–D) Ultrastructure of mitochondria in arterial sections of human (C) and rat (D) observed by transmission electron microscopy. White triangles indicate mitochondria. Scale bars, 5 μm

3.2. Association of ferroptosis with CKD vascular calcification indicated by GSE146638 dataset and Nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing

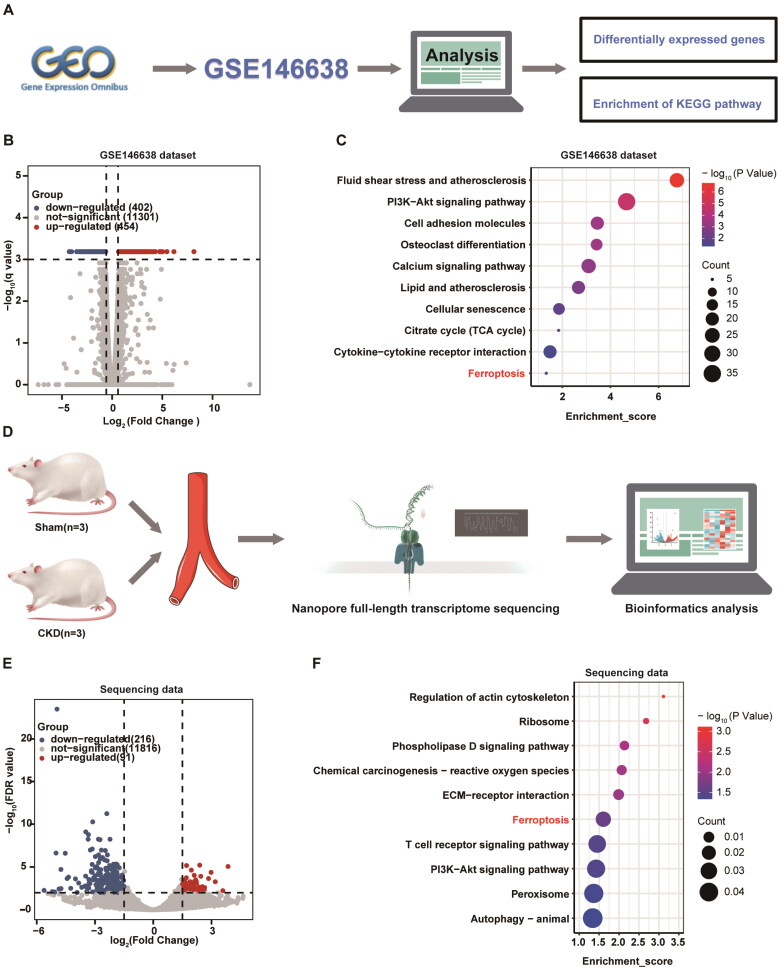

We performed bioinformatics analysis of the RNA-seq dataset of CKD vascular calcified rats from the GEO database (registry number GSE146638) (Figure 2A). This study revealed that 454 genes were upregulated and 402 genes were downregulated in the uremic group compared to the control group (Figure 2B). KEGG enrichment analysis indicated potential signaling pathways in CKD vascular calcification, with a notable contribution from ferroptosis (Figure 2C). Additionally, full-length transcriptome sequencing of arterial tissues from rats subjected to 5/6 nephrectomy and a high-phosphorus diet, as shown in Figure 2D, identified 307 differentially expressed genes (Figure 2E). Similarly, KEGG pathway analysis suggested the enrichment of ferroptosis in CKD vascular calcification (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

GSE146638 Dataset and nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing indicated that ferroptosis is associated with CKD vascular calcification. (A) Overview of the analytical procedures for the GSE146638 dataset. (B) Volcano plot depicting differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the arterial tissues of control (n = 5) and uremic groups (n = 5) from the GSE146638 dataset. The uremic group represents a model of vascular calcification in rats with CKD. (C) Bubble diagram of representative pathways for Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis of DEGs in the GSE146638 dataset. The size of each bubble represents the number of genes enriched in a pathway, and the color indicates the level of significance, with deeper red indicating a more significant difference. (D) Overview of the analytical procedures for nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing. (E) Volcano plot displaying the DEGs in the sham groups (n = 3) and Pi + 5/6 Nx groups (n = 3) from the nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing data. Pi + 5/6 Nx rats represent a vascular calcification model of CKD. Nx, nephrectomy. (F) Bubble diagram of representative pathways for KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs in the nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing data. The size of each bubble represents the number of genes enriched in a pathway, and the color indicates the level of significance, with deeper red indicating a more significant difference

3.3. Ferroptosis facilitates calcium deposition and lipid peroxidation in VSMCs following high calcium and phosphorus treatment

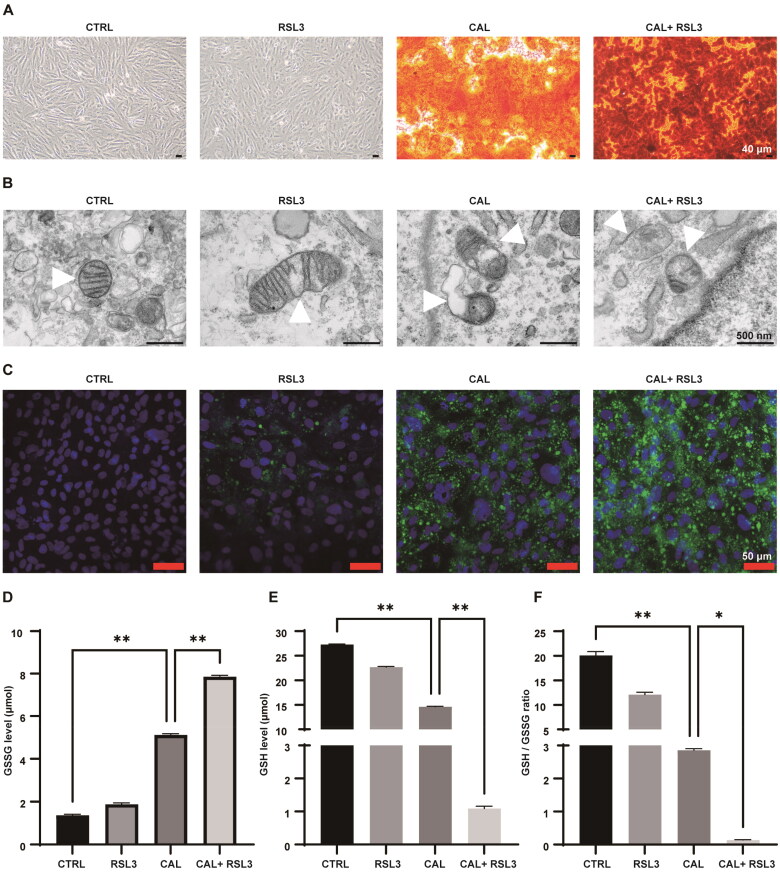

Alizarin red staining indicated a significant calcium deposition in VSMCs under high calcium and phosphorus conditions, which was further exacerbated by RSL3 treatment (Figure 3A). Transmission electron microscopy revealed that RSL3 treatment, in conjunction with high levels of calcium and phosphorus, led to mitochondrial abnormalities, including mitochondrial shrinkage, increased membrane density, and cristae breakage (Figure 3B). Furthermore, RSL3 treatment significantly promoted lipid peroxide accumulation in VSMCs subjected to high calcium and phosphorus (Figure 3C). This accumulation was accompanied by elevated levels of GSSG and a reduction in GSH, leading to a decreased GSH/GSSG ratio (Figure 3D–F). These findings collectively suggest that ferroptosis facilitates calcium deposition and lipid peroxidation in VSMCs under conditions of high calcium and phosphorus.

Figure 3.

Ferroptosis facilitates calcium deposition and lipid peroxidation in VSMCs following treatment with high concentrations of calcium and phosphorus. VSMCs were treated with growth medium or calcifying medium supplemented with or without RSL3 (0.5 μM) for 5 d. (A) Representative images of Alizarin Red staining of VSMCs. Red color indicates calcium deposition. Scale bar, 40 μm. (B) The mitochondrial ultrastructure of VSMCs was examined using transmission electron microscopy. White triangles indicate mitochondria. Scale bar, 500 nm. (C) Detection of lipid peroxidation in VSMCs using a commercial liperidluo kit. Green indicates lipid peroxides, and blue indicates nuclei stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (D–E) The oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and reduced glutathione (GSH) contents in VSMCs were assessed using commercially available GSSG and GSH kits. (F) The GSH-to-GSSG ratio was calculated for each group. ‘CAL’ indicates the cells were treated with a calcifying medium containing high concentrations of calcium and phosphorus for 5 days. *p < .05 and **p < .01

3.4. Bioinformatics analysis suggests HDAC9 is involved in ferroptosis in CKD vascular calcification

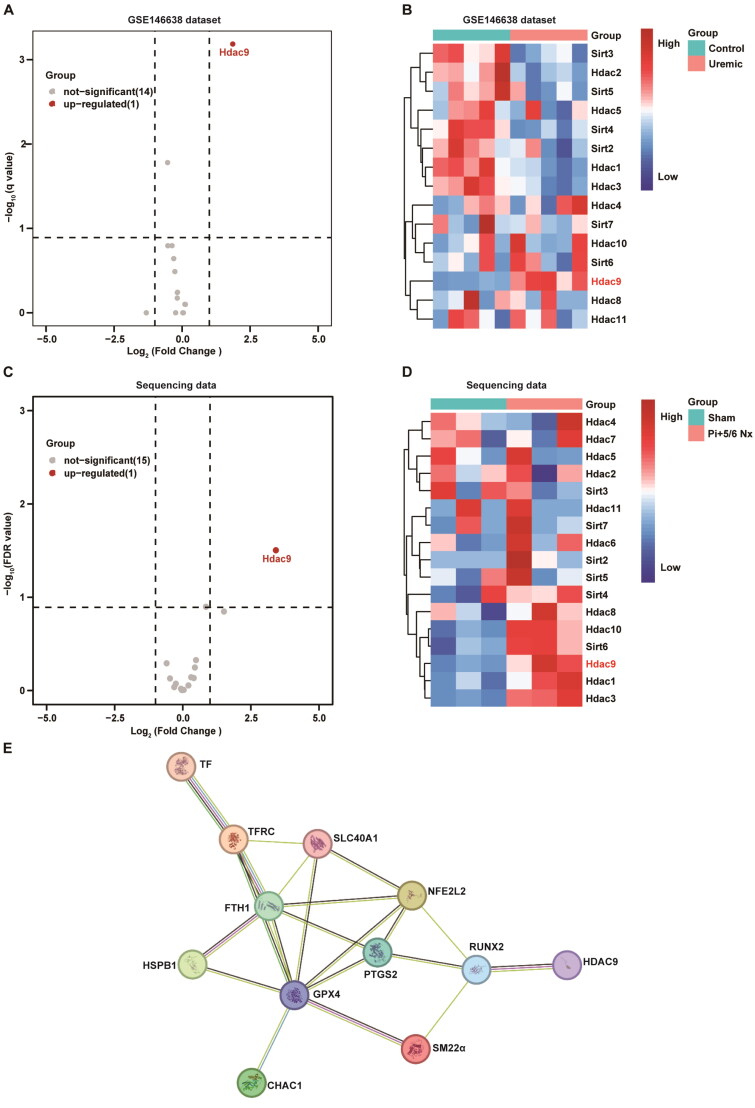

RNA-seq analysis of the GSE146638 dataset revealed significant upregulation of histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9) in the arterial tissue of uremic rats, compared to the control group (log2 FC = 1.86, q < 0.05) (Figure 4A–B). Furthermore, nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing further confirmed significant upregulation of HDAC9 in the arterial tissue of rats in the Pi + 5/6Nx group (log2 FC = 3.42, FDR < 0.05) (Figure 4C–D). Additionally, we identified nine classic genes closely associated with ferroptosis from the FerrDB database: TF, TFRC, SLC40A1, FTH1, GPX4, CHAC1, HSPB1, NFE2L2, and PTGS2. PPI analysis suggested a potential interaction between the proteins encoded by these genes and HDAC9, mediated by Runx2 and SM22α (Figure 4E). These findings indicate that HDAC9 is involved in the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs via ferroptosis under conditions of vascular calcification in CKD.

Figure 4.

Bioinformatics analysis suggested that HDAC9 is involved in ferroptosis in CKD vascular calcification. (A–B) Volcano plot (A) and heatmap (B) displaying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within the histone deacetylation family in the arteries of the control (n = 5) and uremic groups (n = 5) from the GSE146638 dataset. The uremic group represents a model of vascular calcification in CKD rats. (C–D) Volcano plot (C) and heatmap (D) of DEGs within the histone deacetylation family in the aorta of the sham group (n = 3) and Pi + 5/6 Nx group (n = 3) from nanopore full-length transcriptome sequencing data. Nx, nephrectomy. (E) The string database predicts protein interactions of HDAC9 with ferroptosis-associated proteins via Runx2 and SM22α

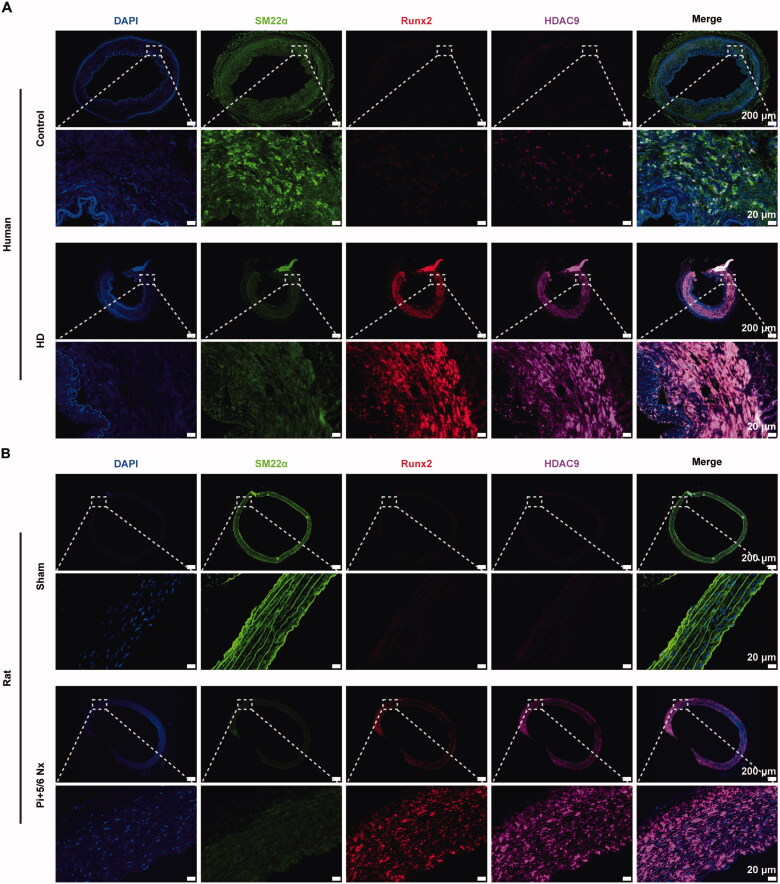

3.5. HDAC9 expression is increased in calcified arteries from patients undergoing HD and CKD rats

In arterial tissues from patient undergoing HD and in CKD rats, multiplex immunofluorescence staining revealed a significant increase in the expression of HDAC9 (purple) and Runx2 (red), accompanied by a decrease in the expression of SM22α (green). Moreover, HDAC9 and Runx2 were found to colocalized in the nucleus (blue) (Figure 5A,B). These findings suggest that HDAC9 expression is upregulated during vascular calcification in patients with CKD.

Figure 5.

Increased expression of HDAC9 in calcified arteries of human and CKD rat models. (A–B) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for SM22α (green), Runx2 (red), and HDAC9 (purple) in human (A) or rat aortas sections (B). The control group represents a normal artery from a patient who underwent amputation surgery. The HD group represents a calcified artery from a patient who underwent maintenance hemodialysis with vascular calcification. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Nx: nephrectomy. Scale bar: 200 µm (low power). Scale bar: 20 µm (high power)

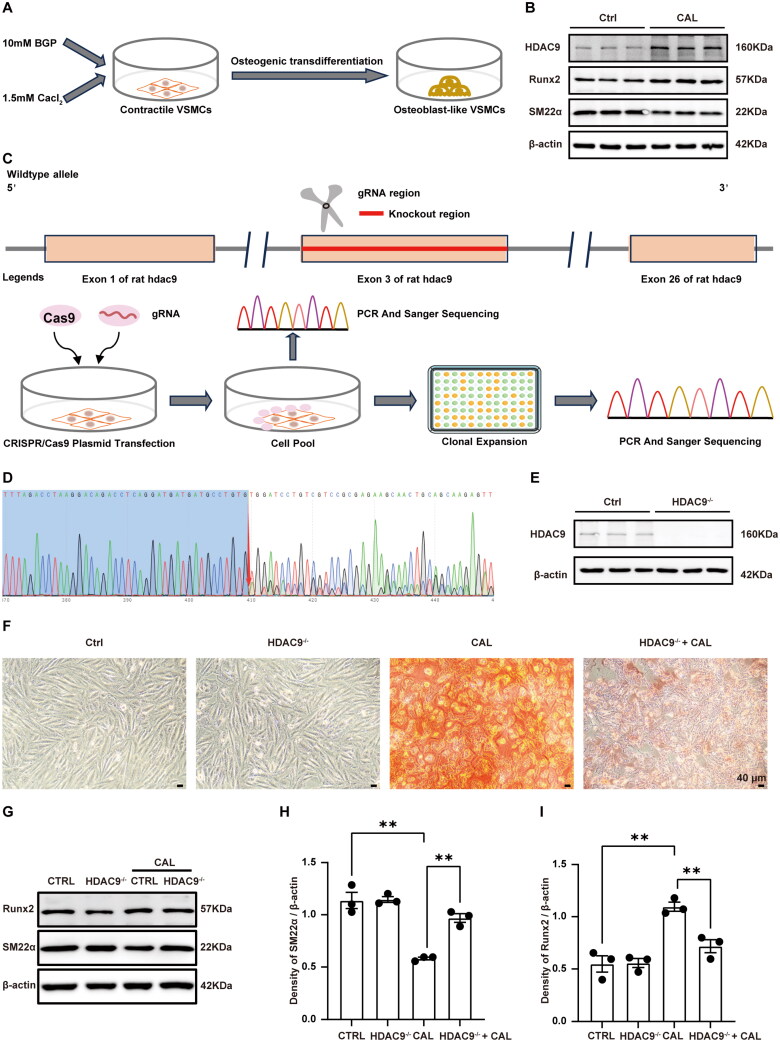

3.6. Knockout of HDAC9 attenuates high calcium/phosphorus-induced osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs

We further explored the function of HDAC9 in the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs. Osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs was induced using a calcifying medium containing 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and 1.5 mM calcium chloride (Figure 6A). Consistent with the results of immunofluorescence staining, HDAC9 protein expression was elevated in VSMCs treated with high levels of calcium and phosphorus, accompanied by an increase in Runx2 and a decrease in SM22α (Figure 6B). Subsequently, we specifically knocked out HDAC9 in VSMCs using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Exon 3 of HDAC9 was targeted (Figure 6C), and sanger sequencing revealed a double peak at base 410 following the knockout (Figure 6D). Western blot analysis further confirmed that HDAC9 protein was not detected in HDAC9 knockout VSMCs (Figure 6E). Alizarin Red S staining showed significant calcium deposition in VSMCs treated with the calcifying medium, which was inhibited by HDAC9 knockout (Figure 6F). Correspondingly, western blot analysis indicated that high calcium/phosphorus stimulation increased Runx2 expression and decreased SM22α expression, while HDAC9 knockout inhibited these effects (Figure 6G–I). These findings support the hypothesis that HDAC9 deficiency attenuates calcium deposition and osteogenic trans-differentiation in VSMCs under high calcium and phosphorus conditions.

Figure 6.

Effect of HDAC9 on the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs upon stimulation with high levels of calcium and phosphorus. (A) a schematic protocol for inducing osteogenic trans-differentiation in VSMCs. (B) Western blot analysis of SM22α and Runx2 and HDAC9 expression in VSMCs. (C) Overview of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology-mediated knockout of HDAC9 in VSMCs. (D) Sanger sequencing was conducted on clonal cell lines following HDAC9 knockout in VSMCs. (E) Western blot analysis of HDAC9 expression in VSMCs. (F) Representative images of Alizarin Red staining of normal VSMCs and HDAC9 knockout VSMCs. Scale bars, 50 μm. (G–I) The protein expression levels and semiquantitative analysis of SM22α and Runx2 expression in VSMCs. ‘HDAC9-/-’ indicates knockout of HDAC9 in VSMCs. ‘CAL’ indicates the cells were treated with a calcifying medium containing high concentrations of calcium and phosphorus for 5 d. N = 3 independent experiments. **p < .01

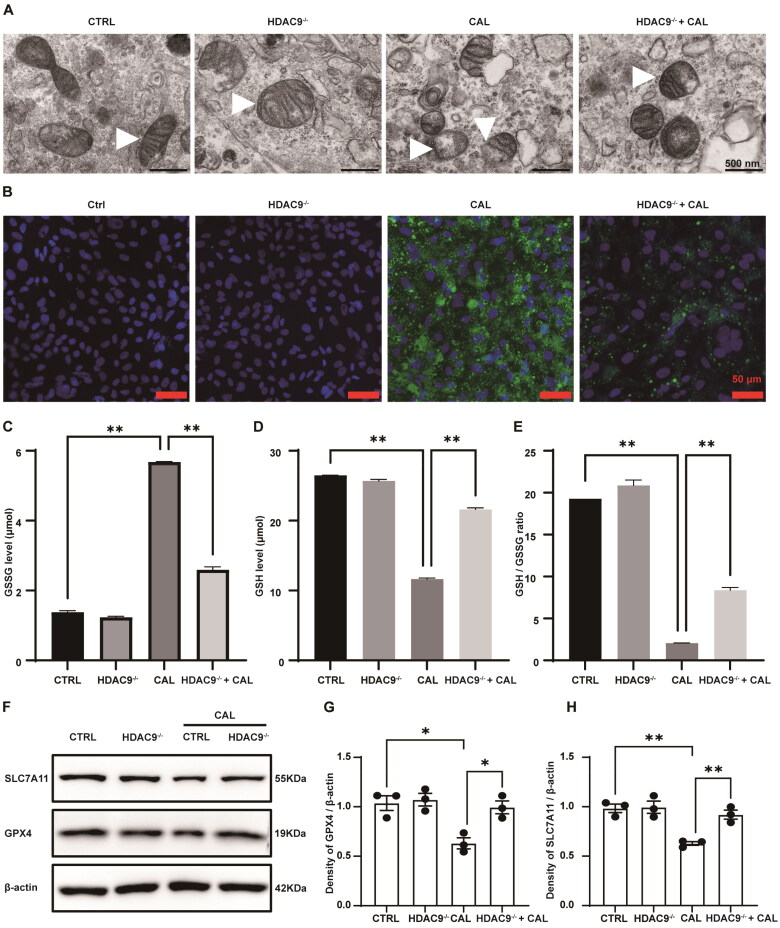

3.7. HDAC9 deficiency inhibits ferroptosis in VSMCs following high calcium and phosphorus treatment

Transmission electron microscopy showed shrinkage of mitochondrial volume, increased membrane density, and loss or breakage of mitochondrial cristae in VSMCs treated with high levels of calcium and phosphorus (Figure 7A). The morphological alterations of mitochondria support the occurrence of ferroptosis in VSMCs. Furthermore, liperfluo measurements indicated a significant elevation in lipid peroxide production in VSMCs exposed to high calcium and phosphorus levels, which was mitigated by HDAC9 knockout (Figure 7B). Consistently, treatment with high levels of calcium and phosphorus led to an increase in the content of GSSG and a decrease in the levels of GSH and the GSH/GSSG ratio in VSMCs. Conversely, the deficiency in HDAC9 was associated with a reduction in GSSG concentrations, an increase in GSH levels and the GSH/GSSG ratio in VSMCs subjected to high calcium and phosphorus (Figure 7C–E). Western blot analysis demonstrated that the induction of high calcium and phosphorus levels resulted in a reduction in the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4, which was partially alleviated by HDAC9 knockout (Figure 7F–H). These findings collectively suggest that HDAC9 deficiency exerts a protective role against ferroptosis in VSMCs under conditions of high-calcium and high-phosphorus treatment.

Figure 7.

Effect of HDAC9 on ferroptosis in VSMCs under conditions of elevated calcium and phosphorus levels. (A) Representative images of the mitochondrial ultrastructure in VSMCs using transmission electron microscopy. White triangles indicate mitochondria. Scale bars, 500 nm. (B) Lipid peroxidation in VSMCs was detected using the Liperfluo kit. Green indicates lipid peroxidation, with nuclei counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 50 μm. (C,D) The concentrations of GSSG and reduced GSH (GSH) in VSMCs. (E) The ratio of reduced GSH (GSH) to GSSG was calculated for each group. (F–H) The protein levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 in VSMCs. ‘HDAC9−/−’ indicates the knockout of HDAC9 in VSMCs. ‘CAL’ indicates the cells were treated with a calcifying medium containing high concentrations of calcium and phosphorus for 5 days. N = 3 independent experiments. *p < .05 and **p < .01

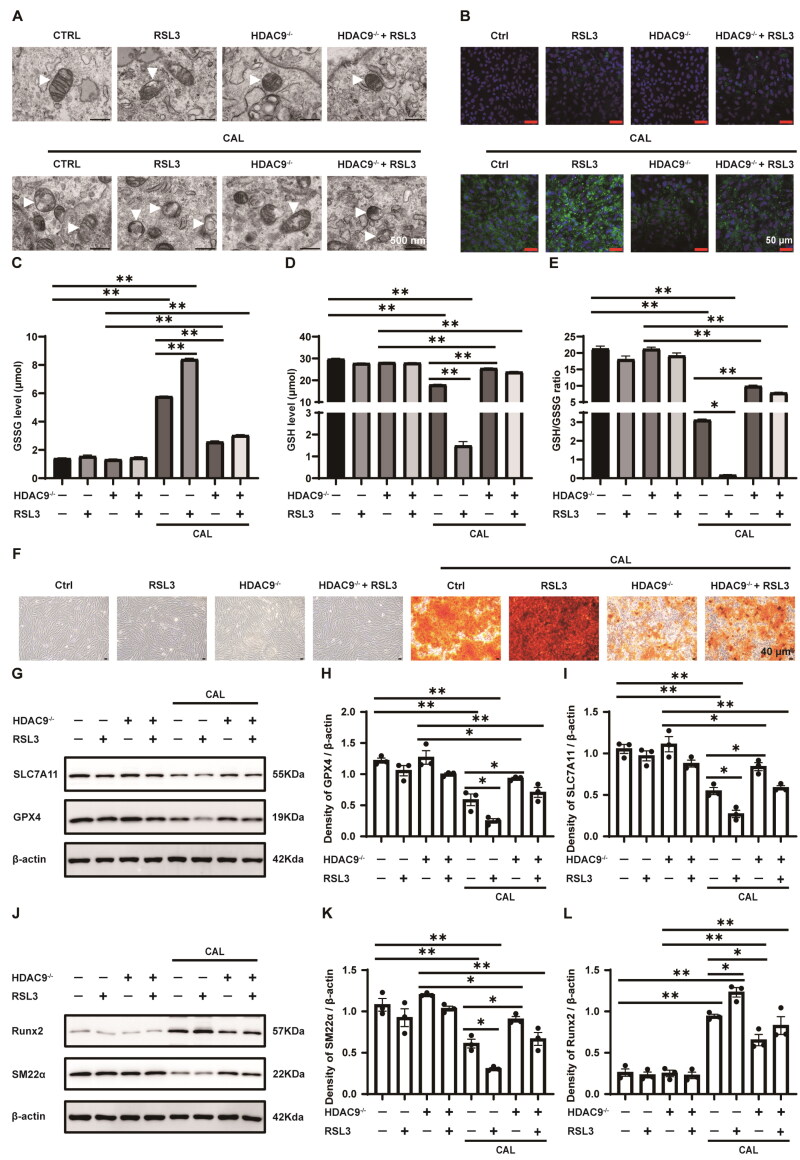

3.8. HDAC9 deficiency suppresses ferroptosis and osteogenic trans-differentiation induced by RSL3 in VSMCs exposed to high calcium and phosphorus conditions

Transmission electron microscopy revealed that high calcium and phosphorus treatments induced the classical mitochondrial features of ferroptosis as previously described, which were aggravated by treatment with RSL3. This effect was partially mitigated by HDAC9 knockout (Figure 8A). Moreover, RSL3 treatment significantly increased lipid peroxide accumulation in VSMCs exposed to high calcium and phosphorus, whereas HDAC9 knockout reduced lipid peroxide production (Figure 8B). Consequently, RSL3 treatment further elevated GSSG levels and reduced GSH content and the GSH/GSSG ratio in VSMCs under high calcium and phosphorus conditions. HDAC9 deficiency inhibited these effects (Figure 8C–E). Additionally, HDAC9 deficiency partially prevented RSL3-promoted calcium deposition in VSMCs under high calcium and phosphorus induction (Figure 8F). Western blot analysis demonstrated that RSL3 further decreased SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression in VSMCs following high calcium and phosphorus treatment, whereas HDAC9 deficiency counteracted these effects in some extent (Figure 8G–I). Furthermore, RSL3 upregulated Runx2 expression and downregulated SM22α expression in VSMCs under high calcium and phosphorus conditions, which was inhibited by HDAC9 knockout (Figure 8J–L). In summary, these data indicate HDAC9 deficiency suppresses ferroptosis and osteogenic trans-differentiation induced by RSL3 in VSMCs exposed to high levels of calcium and phosphorus in vitro.

Figure 8.

The role of HDAC9 in RSL3-mediated ferroptosis and osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs under high calcium and phosphorus conditions. VSMCs with and without HDAC9 were cultured in growth or calcifying medium, with or without RSL3 (0.5 uM), for 5 d. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy images of the ultrastructure of mitochondria in VSMCs. White triangles indicate mitochondria. Scale bar, 500 nm. (B) Lipid peroxidation in VSMCs was assessed using the Liperfluo kit. Green indicates lipid peroxidation. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 50 μm. (C,D) The levels of oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and reduced glutathione (GSH). (E) The ratio of GSH/GSSG for each group was calculated. (F) Calcium deposition was visualized with Alizarin Red S staining. Scale bar, 40 μm. (G–I) The protein expression levels and semiquantitative analysis of GPX4 and SLC7A11 in VSMCs. (J–L) The protein expression levels and semiquantitative analysis of SM22α and Runx2 in VSMCs. ‘HDAC9−/−’ indicates knockout of HDAC9 in VSMCs. ‘CAL’ indicates the cells were treated with a calcifying medium containing high concentrations of calcium and phosphorus for 5 days. N = 3 independent experiments. *p < .05 and **p < .01.

4. Discussion

Ferroptosis is associated with the development and progression of several CVD [23]. Recent studies have shown that inhibition of ferroptosis attenuates atherosclerosis [24]. Furthermore, metformin could mitigate hyperlipidemia-induced vascular calcification by counteracting ferroptosis [25]. However, the role of ferroptosis in CKD vascular calcification remains poorly investigated. In this study, we identified the classical features of ferroptosis in calcified vascular tissues from patient with hemodialysis and CKD rat models. Furthermore, RNA transcriptome sequencing from the GSE146638 dataset [26] and our team revealed that ferroptosis is associated with vascular calcification in CKD. Notably, we found that HDAC9 promotes the trans-differentiation of VSMCs into osteoblast-like cells via involving ferroptosis. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first to demonstrate the role of HDAC9 in ferroptosis in CKD vascular calcification, providing new insights into the prevention and treatment of vascular calcification in CKD.

Vascular calcification, characterized by the abnormal deposition of calcium and phosphorus crystals in the vascular wall [27]. Numerous studies have highlighted its similarities with bone formation, and the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs playing a pivotal role [28,29]. It has been established that elevated levels of calcium and phosphorus can induce VSMCs to transition from a contractile phenotype to osteoblast-like cells [30]. In the current study, we explored the effect of ferroptosis on the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs exposed to high concentrations of calcium and phosphorus. The observed mitochondrial morphological alterations, excessive lipid peroxide accumulation, and abnormal glutathione metabolism suggest that calcium/phosphorus-treated VSMCs underwent ferroptosis, which also indicated that ferroptosis is involved in the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs.

GPX4 is known to eliminat cytotoxic lipid peroxides by converting GSH to GSSG [15]. We examined the alterations in GSH and GPX4 levels in VSMCs induced by high levels of calcium and phosphorus treatments. Furthermore, we quantified the protein levels of SLC7A11, a key subunit involved in the transport of extracellular cystine into cells via the cystine/glutamic acid reverse transport system (system Xc-) [31]. Our study revealed that high calcium and phosphorus levels led to increased GSSG levels and decreased GSH concentrations in VSMCs, accompanied by reduced levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins. Moreover, the ferroptosis inducer RSL3 exacerbated lipid peroxidation and further decreased the protein levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4. In addition, RSL3 increased calcium deposition and Runx2 expression in VSMCs treated with calcium and phosphorus. These findings highlight the role of ferroptosis in promoting the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs.

To elucidate the regulatory mechanism underlying ferroptosis contributes to the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs, we focused on the interaction between HDAC9 and ferroptosis through bioinformatics analyses. HDAC9, a histone deacetylase located on chromosome 7, has been implicated in atherosclerosis and is known to affect the VSMCs phenotype [32]. Previous research has demonstrated that the downregulation of HDAC9 by β-hydroxybutyrate inhibit vascular calcification [33]. However, the specific role of HDAC9 in ferroptosis during CKD vascular calcification has not been fully elucidated. Our findings indicate that HDAC9 expression is elevated in the calcified aortas of patient with hemodialysis and CKD rats. Moreover, the knockout of HDAC9 inhibits the osteogenic trans-differentiation and ferroptosis of VSMCs induced by high levels of calcium and phosphorus. Notably, HDAC9 deficiency alleviated RSL3-induced ferroptosis and osteogenic trans-differentiation in VSMCs under conditions of high calcium and phosphorus. These findings suggest that HDAC9 promotes osteogenic trans-differentiation through ferroptosis.

This study has several limitations. Our investigation was confined to the initial effects of HDAC9 on the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs involving ferroptosis, without fully elucidating the underlying mechanisms. Despite we explored the regulatory role of HDAC9 on ferroptosis, our findings were limited to in vitro observations. Future studies should utilize HDAC9 knockout animal models to gain a better understanding of the specific role and mechanism of HDAC9 on ferroptosis during osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs in CKD vascular calcification. Additionally, we only explored the effect of RSL3 on the osteogenic trans-differentiation of VSMCs. Future research should incorporate multiple ferroptosis inducers and inhibitors to comprehensively investigate the mechanisms by which HDAC9 regulates ferroptosis and affects the phenotypic transformation of VSMCs. It is also important to note that patients with end-stage renal disease, including those who have undergone dialysis, have significantly increased blood aluminum levels [34], which may contribute to ferroptosis [35]. However, in this article, we did not test aluminum levels in hemodialysis patient. In future clinical and research studies, attention should be paid to the effect of aluminum on ferroptosis to minimize the risk of aluminum toxicity in patients with CKD as well as possible confounding factors in scientific studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights that HDAC9 facilitates the trans-differentiation of VSMCs from a contractile phenotype to osteoblast-like cells by involving ferroptosis, providing new insights into preventative and therapeutic strategies for managing vascular calcification in patients with CKD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Prof. Zhenglin Yang at Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, for generously providing the research platform and technical support for this study. We also acknowledge Weishen Wu for his guidance with bioinformatics analysis. We thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20349, 82270729, and 82070690); Projects from Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province (24NSFSC1735 and 2023ZYD0170).

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: L.W, G. L, and Y.L; Methodology: L.X, Q.X, L.H, J.G; Validation: L.X, Q.X, R.C, L.H; Formal Analysis: L.X; Investigation, L.X, Q.X, R.C, L.H; Resources: L.X, Q.X, R.C, L.H; Data Curation: L.X; Writing – Original Draft: L.X; Writing – Review & Editing: G. L and Y.L; Visualization: L.X, J.G; Supervision: L.W, G. L, and Y.L; Funding Acquisition: L.W, G. L, and Y.L. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Yi Li.

References

- 1.GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration . Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;10225(395):709–733. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swartling O, Rydell H, Stendahl M, et al. CKD progression and mortality among men and women: a Nationwide study in Sweden. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(2):190–199.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Gilbertson DT, et al. US renal data system 2022 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;81(3 Suppl1):A8–A11. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cozzolino M, Mangano M, Stucchi A, et al. Cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(suppl_3):iii28–iii34. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Budoff MJ, Reilly MP, et al. Coronary artery calcification and risk of cardiovascular disease and death among patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(6):635–643. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yun HR, Joo YS, Kim HW, et al. Coronary artery calcification score and the progression of chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(8):1590–1601. doi: 10.1681/asn.2022010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung WS, Shih MP, Wu PY, et al. Progression of aortic arch calcification is associated with overall and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis. Dis Markers. 2020;2020:6293185–6293187. doi: 10.1155/2020/6293185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian WB, Zhang WS, Jiang CQ, et al. Aortic arch calcification and risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;23:100460. doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Li G, Yu X, et al. Progression of vascular calcification and clinical outcomes in patients receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2310909. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.10909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durham AL, Speer MY, Scatena M, et al. Role of smooth muscle cells in vascular calcification: implications in atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114(4):590–600. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu CT, Shao YD, Liu YZ, et al. Oxidative stress in vascular calcification. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;519:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2021.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Wang ZW, Fang LJ, et al. Programmed cell death in atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(5):467. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04923-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, et al. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(3):369–379. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):88. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Ren J, Zhang J, et al. FTO ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis via P53-P21/Nrf2 activation in a HuR-dependent m6A manner. Redox Biol. 2024;70:103067. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2024.103067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantrell AC, Zeng H, Chen JX.. The therapeutic potential of targeting ferroptosis in the treatment of mitochondrial cardiomyopathies and heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2024;83(1):23–32. doi: 10.1097/fjc.0000000000001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang CH, Yan YJ, Luo Q.. The molecular mechanisms and potential drug targets of ferroptosis in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Life Sci. 2024;340:122439. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X, Xu XD, Ma MQ, et al. The mechanisms of ferroptosis and its role in atherosclerosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;171:116112. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.116112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye Y, Chen A, Li L, et al. Repression of the antiporter SLC7A11/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 axis drives ferroptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells to facilitate vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 2022;102(6):1259–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voelkl J, Luong TT, Tuffaha R, et al. SGK1 induces vascular smooth muscle cell calcification through NF-κB signaling. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(7):3024–3040. doi: 10.1172/jci96477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X, Lindsay H, Robinson MD.. Robustly detecting differential expression in RNA sequencing data using observation weights. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(11):e91–e91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin S, Wang H, Zhang X, et al. Emerging regulatory mechanisms in cardiovascular disease: ferroptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;174:116457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai T, Li M, Liu Y, et al. Inhibition of ferroptosis alleviates atherosclerosis through attenuating lipid peroxidation and endothelial dysfunction in mouse aortic endothelial cell. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;160:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma WQ, Sun XJ, Zhu Y, et al. Metformin attenuates hyperlipidaemia-associated vascular calcification through anti-ferroptotic effects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;165:229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rukov JL, Gravesen E, Mace ML, et al. Effect of chronic uremia on the transcriptional profile of the calcified aorta analyzed by RNA sequencing. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310(6):F477–491. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00472.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van den Bergh G, Opdebeeck B, D’Haese PC, et al. The vicious cycle of arterial stiffness and arterial media calcification. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25(12):1133–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding N, Lv Y, Su H, et al. Vascular calcification in CKD: new insights into its mechanisms. J Cell Physiol. 2023;238(6):1160–1182. doi: 10.1002/jcp.31021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Zhao X, Wu H.. Arterial stiffness: a focus on vascular calcification and its link to bone mineralization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(5):1078–1093. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.120.313131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbasian N. Vascular calcification mechanisms: updates and renewed insight into signaling pathways involved in high phosphate-mediated vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Biomedicines. 2021;9(7):804. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X, Li J, Kang R, et al. Ferroptosis: machinery and regulation. Autophagy. 2021;17(9):2054–2081. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1810918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malhotra R, Mauer AC, Lino Cardenas CL, et al. HDAC9 is implicated in atherosclerotic aortic calcification and affects vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Nat Genet. 2019;51(11):1580–1587. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0514-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lan Z, Chen A, Li L, et al. Downregulation of HDAC9 by the ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate suppresses vascular calcification. J Pathol. 2022;258(3):213–226. doi: 10.1002/path.5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yüzbaşıoğlu Y, Hazar M, Aydın Dilsiz S, et al. Biomonitoring of oxidative-stress-related genotoxic damage in patients with end-stage renal disease. Toxics. 2024;12(1):69. doi: 10.3390/toxics12010069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ćirović A, Ćirović A, Nikolić D, et al. The adjuvant aluminum fate – Metabolic tale based on the basics of chemistry and biochemistry. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2021;68(2021):126822. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2021.126822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Yi Li.