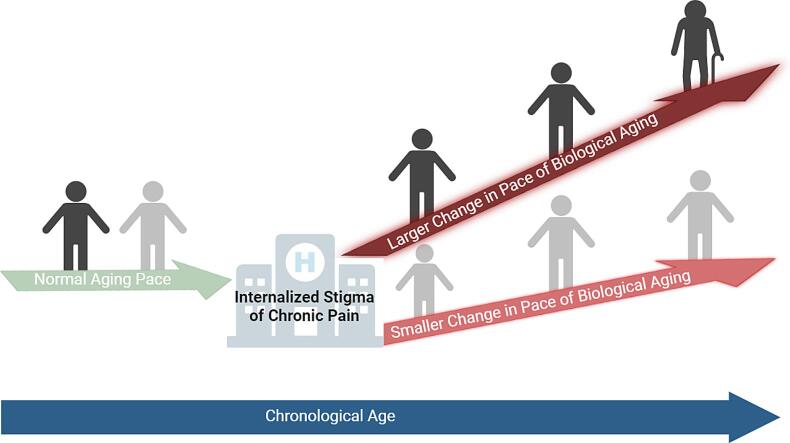

Graphical abstract

Keywords: DunedinPACE, Internalized stigma, Nonspecific chronic low back pain, Pace of biological aging, Epigenetic age, Pain disparities, Moderated mediation

Highlights

-

•

The pace of biological aging (DunedinPACE) positively correlates with the internalized stigma of chronic pain and pain severity and interference.

-

•

The pace of biological aging mediates the relationship between internalized stigma and nonspecific chronic low back pain (CLBP).

-

•

The indirect relationship of internalized stigma with nonspecific CLBP is significant for non-Hispanic Black but not for non-Hispanic White adults.

Abstract

This study aimed to determine the nature of the relationship between the internalized stigma of chronic pain (ISCP), the pace of biological aging, and racial disparities in nonspecific chronic low back pain (CLBP). We used Dunedin Pace of Aging from the Epigenome (DunedinPACE), Horvath’s, Hannum’s, and PhenoAge clocks to determine the pace of biological aging in adults, ages 18 to 82 years: 74 no pain, 56 low-impact pain, and 76 high-impact pain. Individuals with high-impact pain reported higher levels of ISCP and DunedinPACE compared to those with low-impact or no pain (p < 0.001). There was no significant relationship between ISCP and epigenetic age acceleration from Horvath, Hannum, and PhenoAge clocks (p > 0.05). Mediation analysis showed that an association between ISCP and pain severity and interference was mediated by the pace of biological aging (p ≤ 0.001). We further found that race moderated the indirect effect of ISCP on pain severity and interference, with ISCP being a stronger positive predictor of the pace of biological aging for non-Hispanic Blacks (NHBs) than for non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs). Future bio-behavioral interventions targeting internalized stigma surrounding chronic pain at various levels are necessary. A deeper understanding of the biological aging process could lead to improvements in managing nonspecific chronic low back pain (CLBP), particularly within underserved minority populations.

1. Introduction

Nonspecific chronic low back pain (CLBP) is one of the most prevalent and difficult-to-treat chronic pain conditions. Its prevalence increases with age, with a point prevalence of 45.6 % in older adults compared to those 40 years and younger (National Center for Health Statistics, 2021). Unlike most musculoskeletal chronic pain conditions, nonspecific CLBP has no clear structural or anatomical cause and cannot be diagnosed with a radiological test such as a CT scan or MRI. Nevertheless, it is associated with more severe depressive symptoms, (Birkinshaw et al., 2023) increased years lived with disability, (Collaborators, 2023) and decreased quality of life. (Collaborators, 2023, Wong et al., 2022) Like most chronic conditions, racial disparities in CLBP have been documented – non-Hispanic Blacks (NHBs) experience more intense and disabling pain than non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs) (Aroke et al., 2020, Overstreet et al., 2022). Because nonspecific CLBP cannot be diagnosed with conventional biomedical techniques, individuals living with it may experience negative judgments and stereotypes from healthcare providers and others related to their chronic pain.

Stigma, negative judgment, racism, and discrimination have disabling ramifications that can interfere with the management of nonspecific CLBP, especially when accepted by the individual being stigmatized (Slade et al., 2009). Internalized stigma or self-stigmatization is the shame and expectation of discrimination that prevents people from discussing their experiences and seeking help (Gray, 2002). Individuals with nonspecific CLBP experiencing internalized stigma of chronic pain (ISCP) accept or personalize the negative stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination associated with their chronic pain (Perugino et al., 2022, Waugh et al., 2014). ISCP is associated with worse pain outcomes, including greater pain severity, pain-related disability, depressive symptoms, and decreased quality of life (Perugino et al., 2022, Waugh et al., 2014). We have previously documented that higher chronic pain stigma predicts more severe movement-evoked pain among adults with nonspecific CLBP (Penn et al., 2020). ISCP can also impact nonspecific CLBP severity through depressive and insomnia symptoms (Waugh et al., 2014). Although the literature has identified age, race, and stigma-related differences in nonspecific CLBP outcomes, less is known about the mechanisms underlying these differences.

Accumulating evidence suggests that epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation (DNAm) play an essential role in the aging process and age-related chronic conditions. (Hamczyk et al., 2020, Lu et al., 2019) In fact, several DNAm-based algorithms, referred to as ‘epigenetic clocks’, have been used to predict different aspects of biological aging. First and second-generation clocks, such as Horvath, (Hannum et al., 2013, Horvath and Raj, 2018) Hannum, (Hannum et al., 2013, Horvath and Raj, 2018) PhenoAge (Levine et al., 2018); and GrimAge (Lu et al., 2019) epigenetic clocks, indirectly estimate of the rate of biological aging. More recently, the DunedinPACE (Dunedin Pace of Aging Computed from the Epigenome) directly calculates the pace of biological aging. Studies have consistently reported that a faster pace of biological aging correlates with age-related health decline, including a higher mortality risk (Belsky et al., 2022) and worse chronic pain symptoms (Agbor et al., 2024, Aroke et al., 2023, Aroke et al., 2023).

Emerging evidence, primarily from our laboratory, has directly linked the pace of biological aging to nonspecific CLBP outcomes. (Agbor et al., 2024, Agbor et al., 2024, Aroke et al., 2023, Aroke et al., 2023) In fact, we have previously reported that the DunedinPACE is a stronger predictor of nonspecific CLBP than chronological age and pace of biological aging calculated from Horvath, Hannum, and PhenoAge epigenetic clocks (Aroke et al., 2023). We also found that the pace of biological aging mediates the relationship between insomnia and CLBP severity (Aroke et al., 2023). More recently, we found that stronger social support may confer benefits to individuals with nonspecific CLBP by slowing the pace of biological aging (Agbor et al., 2024). Other investigators have reported that experiences of discrimination were associated with accelerated biological aging. (Cuevas et al., 2024) Given the pervasiveness of ISCP combined with the numerous ways in which it can affect health as well as the racial disparities in nonspecific CLBP, it is likely that the pace of biological aging is affected in some way, especially in individuals who report worse pain symptoms such as racialized minorities. However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the relationship between ISCP, the pace of biological aging, and racial pain disparities.

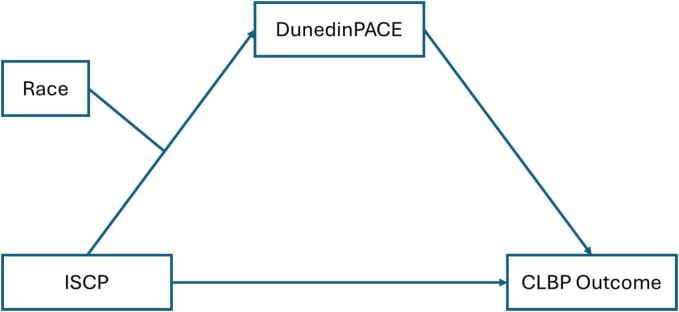

This study aims to address this gap by comprehensively examining the complex relationship between race, ISCP, the pace of biological aging, and nonspecific CLBP outcomes (pain intensity and pain interference). To accomplish this goal, first, we will test the relationship between ISCP and the pace of biological aging using five DNA methylation clocks. We include the various measures of epigenetic aging for comparative analysis, which is superior in uncovering complex relationships. Secondly, we will investigate whether the pace of biological aging mediates the relationship between ISCP and nonspecific CLBP outcomes. Finally, we will test if race has a moderating effect on the relationship between ISCP and DunedinPACE (Fig. 1). We hypothesize that the positive relationship between ISCP and the pace of biological aging will be weaker for NHWs than for NHBs.

Fig. 1.

The theoretical model of the relationship between ISCP, race, DunedinPACE, and CLBP outcomes. The relationship between ISCP and CLBP outcomes is mediated by DunedinPACE. Race moderates the relationship between ISCP and DunedinPACE. Note: ISCP = internalized stigma of chronic pain; DunedinPACE = Dunedin Pace of Aging Computed from Epigenome, CLBP = chronic low back pain.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Participants and settings

This secondary analysis is part of a larger cross-sectional study evaluating epigenetics and gene expression signatures of racial and socioeconomic status disparities in nonspecific CLBP (R01AR079178 and R01MD010441). Eligible participants were adults 18 years and over, with nonspecific CLBP or pain-free control, self-identified as African American/NHB or Caucasian/NHW, able to read and write English, and provided written informed consent. Diagnosis of CLBP was confirmed through electronic medical records. Participants were excluded if their CLBP was due to ankylosing spondylitis, infection, malignancy, compression fracture, or other trauma; they had systematic rheumatic diseases; uncontrolled hypertension; neurological diseases; serious psychiatric disorders requiring hospitalization in the past 12 months or pregnancy. It is worth noting that this paper builds on a preliminary analysis that was disseminated as a poster presentation at the US Association for the Study of Pain Conference in Seattle, Washington (Agbor et al., 2024).

2.2. Procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (IRB-170119003). Details of the study procedures have previously been published (Aroke et al., 2020, Penn et al., 2020). Briefly, a convenient sample of participants was recruited using flyers posted at Pain Clinics and the surrounding environment of Birmingham, AL. Interested participants completed an initial telephone screening to determine eligibility to participate in the study. The diagnosis of nonspecific CLBP was confirmed using electronic medical records and published guidelines (Chou et al., 2007). For comparison, we also recruited healthy controls who met the same eligibility criteria, except for the diagnosis of nonspecific CLBP. Participants completed two sets of pain assessments one week apart in the laboratory setting at UAB. During the first visit, they signed an informed consent form, did some measurements (blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, weight, height, and neck and waist circumference), completed questionnaires, and clinical pain assessments. At the second visit, they completed additional pain assessments through functional performance tasks, and blood samples were collected for DNA extraction and epigenetic age calculation.

2.3. Instruments

Participants completed a sociodemographic questionnaire, the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS), the Internalized Stigma of Chronic Pain (ISCP) Scale, and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) test. All participants self-reported their sex and race, and research staff measured their height and weight, which was used to determine body mass index (BMI).

2.4. Pain intensity and interference

The GCPS was used to determine pain intensity and interference (Von Korff et al., 1992). Consistent with previous works, pain intensity was determined as the average of three pain rating items multiplied by 100. The pain intensity scores ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting more severe pain. Pain interference was determined as an average of the 7 items related to interference with daily activities multiplied by 100. The pain interference scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting more interference with daily activities and enjoyment of life. To fully capture the impact of CLBP, participants were asked, “How many days in the last six (6) months have you been kept from your usual activities because of pain”. Together with the pain intensity and interference scores, the disability days were used to compute the GCPS grades as Grade 0 = pain-free controls (PFCs); Grades 1–2 = low-impact pain; and Grades ≥ 3 = high-impact pain, as previously described (Aroke et al., 2023, Cruz-Almeida et al., 2022). Consistent with published works, chronic low back pain (CLBP) was characterized by pain impact level (Cruz-Almeida et al., 2017, Cruz-Almeida et al., 2022, Von Korff et al., 1992). In our sample, GCPS has excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.97).

2.5. Internalized stigma of chronic pain

The 28-item Internalized Stigma of Chronic Pain scale was used to determine ISCP and its associated symptoms: alienation, experiences of discrimination, stereotype endorsement, social isolation, and stigma resistance (which was reverse-coded before being factored into the total score) (Waugh et al., 2014). Previous work has indicated that the stereotype endorsement subscale is not sufficiently reliable and does not fit well with the other subscales (Waugh et al., 2014). Thus, the total score for internalized stigma of chronic pain is only comprised of the four remaining subscales. Participants responded to the following statements on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree): “I feel embarrassed or ashamed that I have chronic pain,” “I feel inferior to others who don’t have chronic pain,” I am disappointed in myself for having chronic pain.” After reverse coding positively worded items, total scores are calculated by taking the average of the four subscales. Scores range from 1 to 4, and higher scores on this measure indicate greater internalized stigma of chronic pain. The ISCP scale used in this study had an excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

2.6. Epigenetic aging and pace of biological aging

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected from the antecubital vein, and genomic DNA was extracted as previously described (Aroke et al., 2022). Following centrifugation, DNA was extracted from the buffy coat using the Puregen DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), quantified using a NanoDrop UV spectrophotometer, and normalized to a concentration of 50 ng per microliter. Extracted DNA was sent on dry ice to the University of Minnesota Genomic Center, and DNAm was measured using the Illumina Infinium Human MethylationEPIC BeadChip v2.0 arrays (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). All samples were scanned using the Illumina iScan (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA), and quality control procedures were performed. Five samples were randomly selected and run in duplicate for quality control. Sample replicates were checked to ensure a correlation value of at least 0.99.

The Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) at the University of Minnesota Genomics Center targeted over 935,000 CpG sites in the human methylome, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The manifest file, “IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICv2manifest”, was utilized for minfi (v1.48.0) (Aryee et al., 2014) to determine differential methylation loci (https://github.com/jokergoo/IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICv2manifest). The raw data was quantile normalized using “preprocessQuantile” (Touleimat and Tost, 2012). For each CpG site, the raw beta values were extracted and submitted with the sex and age of participants to calculate DNA methylation age, epigenetic age acceleration, and biological age. Epigenetic clocks and age acceleration, including the Horvath (Horvath and Raj, 2018); Hannum (Hannum et al., 2013); and PhenoAge (Levine et al., 2018) were calculated using the online DNA Methylation Age Calculator developed by the Horvath laboratory (https://dnamage.clockfoundation.org/) (Horvath, 2013). DunedinPACE scores were calculated from the beta values using the R-software package DunedinPACE (v0.99.0) and the default proportion of probes required for EPICv2 data as described by Belsky et al (Belsky et al., 2022). The pace of biological aging was adjusted for participant phenotypes (sex and chronological age).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Before testing the study’s hypotheses, initial screening and cleaning of the data were completed. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (Windows v29.0.2.0) and visualized with R® (v4.3.3). Descriptive analyses compared chronological age, pain and stigma outcomes, and epigenetic age and epigenetic age acceleration between pain impact groups (no pain, low impact pain, and high impact pain), using one-way ANOVA to determine average group differences. The chi-squared test was utilized to detect differences in categorical variables (sex, race, and income) among the pain impact groups. Pearson’s correlations were used to evaluate the association between the pace of biological aging and pain and stigma outcomes. SPSS PROCESS Macro (v4.2) was utilized to test whether the pace of biological aging (DunedinPACE) mediates the relationship between ISCP and pain severity and interference (model 4). Also, we used a moderated mediation model (Model 7) to test whether race moderates the indirect relationship between ISCP and pain outcomes through DunedinPACE. A bootstrapping approach with a random sample of 5000 was used for the mediation analysis, and a p-value < 0.05 was statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of study participants

A total of 207 participants were included: 74 PFCs, 56 individuals with low-impact pain, and 77 individuals with high-impact pain. The distribution of demographic and health characteristics according to the pain impact group is shown in Table 1. The demographics include NHWs (47.83 %) and NHBs (52.17 %) adults who self-identified as male (48.10 %) or female (51.90 %). NHBs were more likely to report higher impact pain and be older in chronological age at the time of DNAm sampling than NHWs (p ≤ 0.05). There was no significant sex or household income level between pain-impact groups (p > 0.05). On average, individuals in the high-impact pain group reported more feelings of alienation, experiences of discrimination, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance compared to those with low-impact or no pain. Notably, in contrast to stigma resistance, there were statistically significant differences between the pain-impact groups (p ≤ 0.05; Supplemental Fig. 1). In terms of biological aging, individuals in the no-pain group had a younger Horvath age, Hannum age, and PhenoAge relative to those in the low and high-impact pain groups. However, the age differences based on the Horvath and Hannum clocks were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Overall, there was no significant difference in epigenetic age acceleration between the groups (p > 0.05), but the pace of biological aging was significantly faster in those with high-impact pain (p ≤ 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline covariates among cases based on pain impact.

| Covariate | No pain (n = 74) | Low impact pain (n = 56) | High impact pain (n = 77) | Total (n = 207) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n, %) | 0.510 | ||||

| Men | 36 (48.60) | 30 (53.60) | 33 (43.40) | 99 (48.10) | |

| Women | 38 (51.40) | 26 (46.40) | 43(56.60) | 107 (51.90) | |

| Race (n, %) | 0.003 | ||||

| Black | 27 (36.49) | 34 (60.71) | 47 (61.04) | 108 (52.17) | |

| White | 47 (63.51) | 22 (39.29) | 30 (38.96) | 99 (47.83) | |

| Income level (n, %) | 0.085 | ||||

| $0 – 24,999 | 16 (23.19) | 14 (25.45) | 29 (38.67) | 59 (29.65) | |

| $25,000 – 49,999 | 19 (27.54) | 16 (29.09) | 13 (17.33) | 48 (24.12) | |

| $50,000 – 74,999 | 12 (17.39) | 7 (12.73) | 17 (22.67) | 36 (18.09) | |

| $75,000 – 99,999 | 5 (7.25) | 5 (9.09) | 9 (12.00) | 19 (9.55) | |

| $100,000+ | 17 (24.64) | 13 (23.64) | 7 (9.33) | 37 (18.59) | |

| ISCP Total | 27.4 ± 1.51 | 38.86 ± 1.76 | 51.97 ± 1.47 | 40.00 ± 1.17 | <0.001 |

| Alienation | 6.27 ± 0.14 | 8.31 ± 0.43 | 11.61 ± 0.53 | 9.26 ± 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Stereotype Discrimination | 9.26 ± 0.34 | 11.00 ± 0.53 | 13.43 ± 0.34 | 11.34 ± 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Discrimination Experience | 5.20 ± 0.18 | 6.28 ± 0.32 | 7.78 ± 0.38 | 6.67 ± 0.21 | <0.001 |

| Social Withdrawal | 6.53 ± 0.26 | 8.14 ± 0.36 | 11.20 ± 0.43 | 9.11 ± 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Stigma Resistance | 7.10 ± 0.46 | 7.27 ± 0.41 | 8.21 ± 0.26 | 7.58 ± 0.22 | 0.061 |

| Pain Severity | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 39.23 ± 2.80 | 70.56 ± 1.75 | 37.04 ± 2.33 | <0.001 |

| Pain Interference | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 19.29 ± 2.49 | 63.01 ± 2.54 | 28.79 ± 2.24 | <0.001 |

| Chronological Age | 35.72 ± 1.72 | 42.39 ± 1.84 | 45.03 ± 1.71 | 40.99 ± 1.05 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 29.02 ± 1.56 | 30.82 ± 0.89 | 32.57 ± 0.90 | 30.82 ± 0.70 | 0.097 |

| Horvath Age | 40.77 ± 2.00 | 45.47 ± 2.08 | 46.65 ± 1.75 | 44.23 ± 1.13 | 0.066 |

| Hannum Age | 32.14 ± 2.57 | 35.18 ± 2.84 | 36.8 ± 2.47 | 34.69 ± 1.51 | 0.412 |

| PhenoAge | 32.77 ± 1.54 | 40.59 ± 1.78 | 43.05 ± 1.64 | 38.71 ± 1.00 | <0.001 |

| DunedinPACE | 1.00 ± 0.01 | 1.06 ± 0.02 | 1.10 ± 0.02 | 1.05 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Accelerated Epigenetic Aging | |||||

| ΔHorvath | 5.05 ± 0.97 | 3.08 ± 1.13 | 1.63 ± 1.05 | 3.24 ± 0.61 | 0.055 |

| ΔHannum | −3.58 ± 1.78 | −7.22 ± 2.21 | −8.22 ± 2.05 | −6.29 ± 1.16 | 0.208 |

| ΔPhenoAge | −2.95 ± 0.76 | −1.80 ± 0.94 | −1.98 ± 1.04 | −2.28 ± 0.53 | 0.640 |

NOTE: Different letters indicate means that differ between pain impact groups, p ≤ 0.05. All values are represented as mean ± SEM. P-value was obtained from chi-squared test or one-way ANOVA via SPSS where appropriate. ΔHorvath: difference between epigenetic age by Horvath’s and chronological age; ΔHannum: difference between epigenetic age by Hannum’s and chronological age; ΔPhenoAge: difference between phenotypic epigenetic age and chronological age.

3.2. Associations of internalized stigma of chronic pain, pain outcomes, and markers of biological age

Table 2 shows unadjusted bivariate correlation analyses between key study variables. As expected, there was a significant positive relationship between ISCP, pain severity, and pain interference (p < 0.001). Also, a faster pace of biological aging (higher DunedinPACE scores) significantly correlated with higher ISCP (r = 0.244, p ≤ 0.001), pain severity (r = 0.408, p ≤ 0.001), and pain interference (r = 0.405, p ≤ 0.001). Notably, there was no significant correlation between epigenetic age acceleration and pain outcomes (pain severity and pain interference), but epigenetic age acceleration measured by Horvath’s clock was negatively correlated with ISCP (r = -0.168, p ≤ 0.05).

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlations among chronic pain stigma scale, pain outcomes, and markers of biological age.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pain Severity | 1.000 | |||||

| 2 | Pain Interference | 0.898*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 3 | ISCP | 0.700*** | 0.706*** | 1.000 | |||

| 4 | Horvath EAA | −0.099 | −0.077 | −0.168* | 1.000 | ||

| 5 | Hannum EAA | −0.043 | −0.016 | −0.129 | 0.906*** | 1.000 | |

| 6 | PhenoAge EAA | −0.027 | −0.020 | 0.012 | −0.206*** | −0.393*** | 1.000 |

| 7 | DunedinPACE | 0.408*** | 0.405*** | 0.351*** | −0.073 | −0.027 | 0.109 |

NOTE: * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001.

3.3. Associations of markers of biological age with internalized stigma of chronic pain subscales

To understand the relationship between ISCP and the pace of biological aging, we examined bivariate correlations between four markers of biological aging (EAA and DunedinPACE) and all the dimensions of ISCP (Table 3). As expected, there was a significant correlation between various symptoms of ISCP. Interestingly, stigma resistance did not significantly correlate with other ISCP symptoms. The Dunedin pace of biological aging positively correlated with all symptoms of internalized stigma: alienation (r = 0.244, p ≤ 0.001), discrimination experience (r = 0.205, p ≤ 0.001), social withdrawal (r = 0.257, p ≤ 0.001), and stigma resistance (r = 0.288, p ≤ 0.001). Interestingly, no symptoms of internalized stigma were significantly correlated with epigenetic age acceleration.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlations among chronic pain stigma subscales and markers of biological age.

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alienation | 1.000 | ||||||

| 2 | Discrimination Experience | 0.635*** | 1.000 | |||||

| 3 | Social Withdrawal | 0.783*** | 0.691*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 4 | Stigma Resistance | 0.135 | 0.093 | 0.097 | 1.000 | |||

| 5 | Horvath EAA | −0.018 | −0.032 | 0.043 | −0.126 | 1.000 | ||

| 6 | Hannum EAA | 0.020 | −0.061 | 0.039 | −0.082 | 0.906*** | 1.000 | |

| 7 | PhenoAge EAA | 0.013 | −0.021 | −0.083 | 0.037 | −0.206** | −0.379*** | 1.000 |

| 8 | DunedinPACE | 0.244*** | 0.205*** | 0.257*** | 0.288*** | −0.073 | −0.027 | 0.109 |

NOTE: * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001.

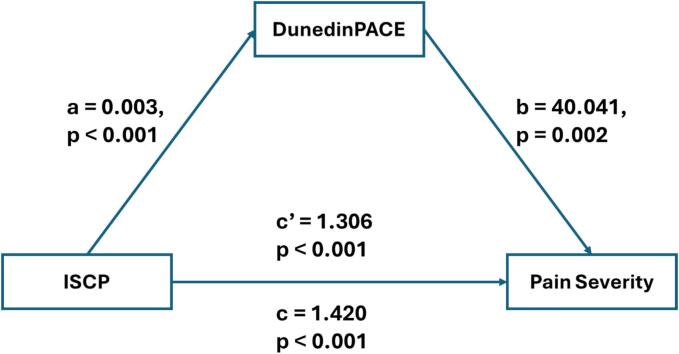

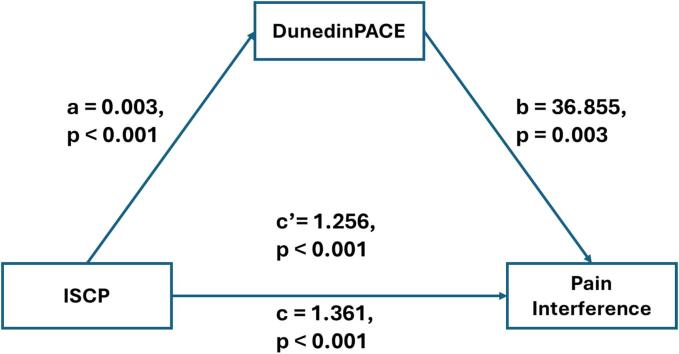

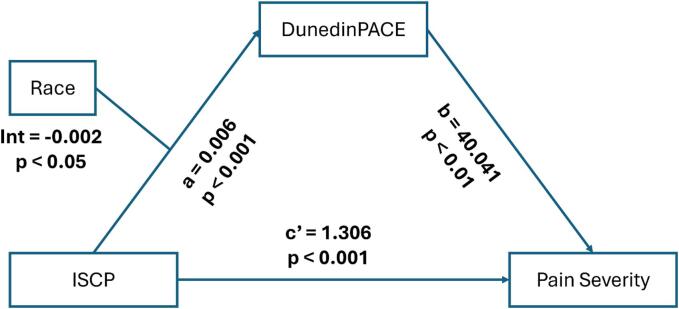

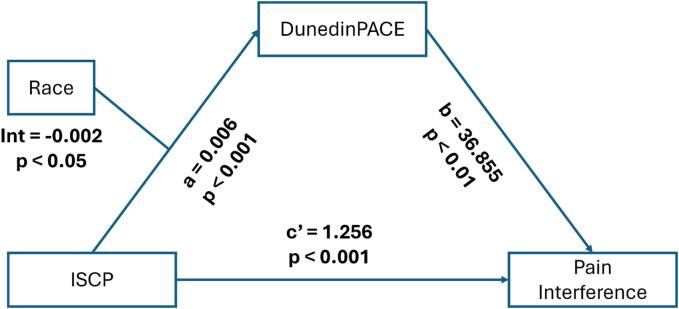

3.4. Testing the mediating role of the pace of biological aging

The results of the mediating effect between ISCP and pain severity, as well as pain interference, are depicted in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, and summarized in Table 4. After controlling for sex and BMI, the total effect of ISCP on pain severity and pain interference were statistically significant (β = 1.42 (0.10), p < 0.001 and β = 1.36 (0.10), p < 0.001, respectively). In addition, the indirect effects of ISCP on both pain severity and pain interference through the pace of biological aging were all significant, supporting the mediating role of the pace of biological aging in the relationship between ISCP and pain outcomes were present and valid. The model, including ISCP, the pace of biological aging, and covariates, accounted for 52.9 % and 53.2 % of the variance in pain severity and pain interference, respectively.

Fig. 2.

The mediating model for internalized stigma, pace of biological aging, and pain severity. Note: ISCP = internalized stigma of chronic pain; DunedinPACE = Dunedin Pace of Aging Computed from Epigenome.

Fig. 3.

The mediating model for internalized stigma, pace of biological aging, and pain interference. Note: ISCP = internalized stigma of chronic pain; DunedinPACE = Dunedin Pace of Aging Computed from Epigenome.

Table 4.

Bootstrapping indirect effects for the mediating model.

| Model paths | Bootstrap total effect |

Bootstrap indirect effect |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (SE) | LLCI | ULCI | Beta | LLCI | ULCI | |

| ISCP → DunedinPACE → Pain severity | 1.420 (0.104) | 1.215 | 1.1626 | 0.114 (0.050) | 0.018 | 0.211 |

| ISCP → DunedinPACE → Pain interference | 1.366 (0.099) | 1.166 | 1.556 | 0.105 (0.048) | 0.015 | 0.198 |

LLCI, Lower Limit 95 % Confidence Interval; ULCI, Upper Limit 95 % Confidence Interval. SE = standard error. All models included sex and BMI as covariates.

3.5. Testing the moderating effect of race

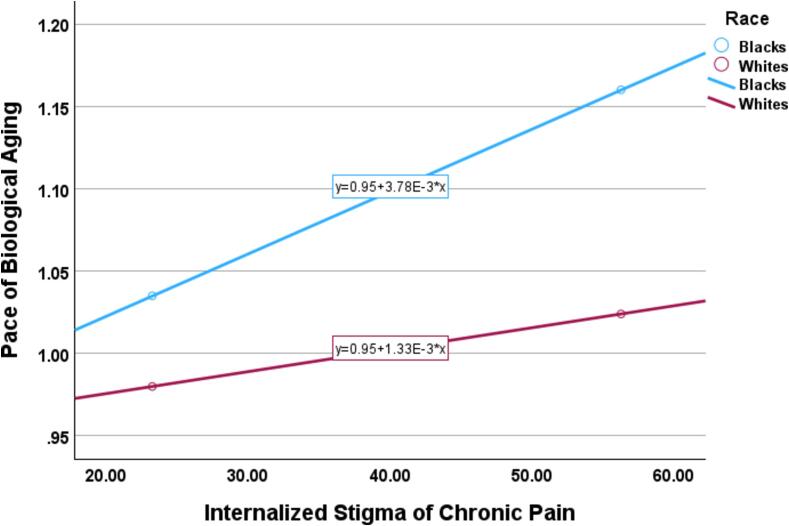

We performed a moderated mediation analysis to test whether the impact of ISCP on the pace of biological aging varied as a function of self-identified race in a valid mediating relationship (Fig. 4). Self-identified race moderated the predictive ability of ISCP for DunedinPACE. The results of the moderated mediating effect between ISCP and pain severity, as well as pain interference, are depicted in Fig. 5, Fig. 6. As shown in Table 5, the indirect effect of ISCP on pain severity through DunedinPACE was statistically significant for NHBs (β = 1.15 (0.06), Boot 95 % CI [0.027, 0.279]) but not for NHWs (β = 0.05 (0.04), Boot 95 % CI [-0.007, 0.129]). The index of moderated mediation was significant (β = -0.099 (0.05), Boot 95 % CI [-0.214, −0.008]). Similarly, the indirect effect of ISCP on pain interference through DunedinPACE was statistically significant for NHBs (β = 1.14 (0.06), Boot 95 % CI [0.015, 0.259]) but not for NHWs (β = 0.05 (0.03), Boot 95 % CI [-0.007, 0.121]). The index of moderated mediation was significant (β = -0.091 (0.05), Boot 95 % CI [-0.203, −0.004]).

Fig. 4.

Moderation of the effect of internalized stigma of the pace of biological aging by race.

Fig. 5.

The mediating model for internalized stigma, pace of biological aging, and pain severity moderated by race. Note: ISCP = internalized stigma of chronic pain; DunedinPACE = Dunedin Pace of Aging Computed from Epigenome.

Fig. 6.

The mediating model for internalized stigma, pace of biological aging, and pain interference moderated by race. Note: ISCP = internalized stigma of chronic pain; DunedinPACE = Dunedin Pace of Aging Computed from Epigenome.

Table 5.

Conditional indirect effects of ISCP on pain outcomes through DunedinPACE by race.

| Race | Pain severity |

Pain interference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot indirect effect (SE) | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Boot indirect effect (SE) | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| Black | 0.152 (0.065) | 0.027 | 0.279 | 0.140 (0.061) | 0.01 | 0.259 |

| White | 0.053 (0.036) | −0.007 | 0.129 | 0.049 (0.034) | −0.007 | 0.121 |

LLCI, Lower Limit 95 % Confidence Interval; ULCI, Upper Limit 95 % Confidence Interval. SE = standard error. Bold indicates a statistically significant model. All models included sex and BMI as covariates.

4. Discussion

Nonspecific CLBP does not have a readily identifiable cause, which makes it prompt stigmatization that worsens pain outcomes and quality of life (Hickling et al., 2024, Holubova et al., 2016). To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the mediator role of the pace of biological aging between ISCP and pain outcomes among adults with nonspecific CLBP. The main findings demonstrate that internalized stigma of chronic pain was positively associated with the pace of biological aging and both pain severity and interference. Specifically, the pace of biological aging mediates the relationship between the pace of biological aging and CLBP severity and interference. However, self-identified race moderated the effect of ISCP on pain outcomes through the pace of biological aging. The indirect effect was statistically significant for NHBs but not for NHWs.

In this study, we found that higher levels of internalized stigma of chronic pain positively correlate with a faster pace of biological aging. To our knowledge, no study has directly examined the relationship between ISCP and the aging process. Recently, life experiences such as neighborhood deprivation (Lawrence et al., 2020) and internalized stigma of chronic pain (Ghanooni et al., 2022) were found to have no association with age acceleration measured by Horvath’s clock. Interestingly, epigenetic age acceleration measured by Horvath’s clock was negatively correlated with ISCP. While the exact cause of these diversion results remains to be explored in future studies, it is possible that the difference may be related to the differences in the epigenetic clock algorithm. While the Horvath clock was trained to predict chronological age, DunedinPACE was developed to predict the pace of biological aging. Emerging evidence suggests that third-generation clocks such as the DunedinPACE are more accurate predictors of biological aging. (Belsky et al., 2022) Also, the different clocks incorporate different CpGs into the algorithm. However, there is a long history of a strong, undesired correlation between social stigma and stress (De Ruddere and Craig, 2016, Stangl et al., 2019). Drawing from stress regulation and epigenetic research, which demonstrate that psychosocial stress can have a profound impact on immune and neuroinflammatory processes through epigenetic modifications, we speculate that internalized stigma of chronic pain is a chronic stressor (Branham et al., 2023, Martin et al., 2022). Studies have also shown that ISCP is associated with differential DNAm of genes in pathways that regulate neuroinflammatory processes. Other investigators have also shown that psychosocial stress can accelerate the pace of biological aging through multiple pathways, including DNA damage, inflammation, mitochondrial damage, and telomere shortening (Polsky et al., 2022). An accelerated pace of aging is associated with many chronic conditions, including chronic pain (Aroke et al., 2023, Cruz-Almeida et al., 2022), and all-cause mortality (Marioni et al., 2015, Perna et al., 2016). Thus, it is possible that the internalized stigma of chronic pain drives worse pain outcomes through epigenetic modifications in inflammatory processes that accelerate the pace of biological aging.

One of the major findings from our study is that the pace of biological aging mediates the relationship between ISCP and CLBP in NHBs but not in NHWs. These findings corroborate existing research that has shown that individuals who experience negative societal stereotypes and discrimination about their disease process or identity, such as race, frequently have heightened stress responses and inflammation, culminating in an acceleration of biological aging processes (Aroke et al., 2022, Avila-Rieger et al., 2022, Yannatos et al., 2023). NHBs frequently experience many forms of discrimination and racism that predispose them to a lifetime of stress. Emerging evidence suggests that stigmatization and internalized stigma of chronic pain are more common among minoritized groups (Harris, 2023). Thus, it is possible that the accumulating effect of bias, stereotype, and discrimination may be accelerating the aging process in minoritized groups. Future studies should directly assess whether structural and systemic racism contributes to a faster pace of aging, as well as whether the pace of biological aging explains racial disparities in chronic pain.

The subgroup analysis of the symptoms of ISCP in this study provided nuanced insights into the associations between ISCP experiences and the different outcomes. This is important because the outcomes of internalized stigma of chronic pain are context- and population-specific (Scholz et al., 2023). While most of the bivariate associations between the different facets of ISCP and the pain outcomes were significant, the strongest associations were with experiences of alienation and social withdrawal. These findings have implications for future research and clinical interventions, suggesting that stigma must be addressed at intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural levels. Future studies should investigate strategies to enhance psychosocial coping and resilience, decrease interpersonal discrimination and prejudices, and policies and laws that promote equity.

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing different measures of epigenetic age acceleration/pace of biological aging and internalized stigma of chronic pain. The analysis of the relationship of ISCP with chronological age, Horvath age, Hannum age, and PhenoAge revealed a significant association with chronological age and PhenoAge but not Horvath and Hannum ages. Additionally, examination of the association with age acceleration showed significance with DunedinPACE but not epigenetic age acceleration. Our findings corroborate previous findings that 1st and 2nd generation epigenetic clocks are not robust predictors of age-related diseases as well as functional decline (Aroke et al., 2023). The discrepancy in various epigenetic clocks may be due to the differences in training phenotype for each epigenetic clocks (Belsky et al., 2022, Bernabeu et al., 2023). Recent findings validate DunedinPACE as a viable approach to capture age-related physiological changes, including chronic pain (Agbor et al., 2024, Aroke et al., 2023, Aroke et al., 2023). These findings highlight the importance of carefully selecting the appropriate epigenetic clock for age-related research.

This study has major strengths that increase the generalization and usability of the findings. First, the use of different epigenetic clocks is a significant strength that allows for a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena. Also, the use of well-phenotyped samples with valid and reliable instruments increases the generalizability of the findings. Another major strength is the comparability between epigenetic analyses between blood and other tissues, particularly neuronal tissues. Previous works in psychiatric epigenetic studies have focused on cross-tissue analyses between peripheral tissues and brain tissues since access to brain samples is limited. In studies investigating schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease, researchers provide compelling results that validate the use of surrogate tissues (Silva et al., 2022, Lin et al., 2018).

Despite these strengths, the study has some limitations. Firstly, the study’s cross-sectional design means the data collected was from a single time point, making it difficult to establish a causal relationship between the pace of biological aging, ISCP, and nonspecific CLBP. Future studies should use a longitudinal repeated-measures approach to capture the temporal evolution of CLBP symptoms, durations of pain, and biological aging. Second, stigma and various forms of biases and discrimination occur at various levels: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural levels (Harris, 2023, Stangl et al., 2019). Future studies should examine the impact of various forms of discrimination as well as their intersectional association with nonspecific CLBP. Finally, the pattern of findings reported may be influenced by the community context of this study. Because the study sample was drawn to be representative of the population of Black and NHWs with nonspecific CLBP in Birmingham, Alabama, further study is needed to determine whether the findings reported are generalizable to the broader U.S. population.

5. Conclusion

Nonspecific CLBP is a highly prevalence and impactful age-related chronic condition that has been associated with ISCP. Yet, the mechanism by which ISCP leads to worse pain outcomes remains unclear. Our findings address this gap, reporting that higher ISCP is associated with a faster pace of biological aging, which predicts greater pain severity and interference. Additionally, the relationship between ISCP and the pace of biological aging is significant for NHBs but not NHWs. Future studies could continue to examine the biological mechanisms through which ISCP affects the aging process and nonspecific CLBP. In clinical practice, research supports interventions to address stigma (e.g., coping and resilience, bias training, and health equity) and faster aging (e.g., exercise, healthy diet, sleep, etc.) as potential targets to improve nonspecific CLBP outcomes.

6. Perspective

The relationship link of internalized stigma of chronic pain (ISCP) with pain severity and pain interference through the pace of biological aging is race-specific; it is significant in non-Hispanic Black but not non-Hispanic White adults. Culturally sensitive Interventions to slow the pace of biological aging and reduce stigma may improve CLBP outcomes.

Author Contributions

The study was conceptualized by V.S., H.K.T., R.E.S., B.R.G., and E.N.A. Sample processing and data analysis was primarily performed by T.Q. Initial manuscript preparation by K.F. with review and revision by F.B.A.T.A., K.R.K., H.K.T., R.E.S., B.R.G., and E.N.A. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R01AR079178 and R01MD010441).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Khalid W. Freij: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Fiona B.A.T. Agbor: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Kiari R. Kinnie: Writing – review & editing. Vinodh Srinivasasainagendra: Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Tammie L. Quinn: Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Hemant K. Tiwari: Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Robert E. Sorge: Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Burel R. Goodin: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Edwin N. Aroke: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynpai.2024.100170.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Agbor F., Stoudmire T., Goodin B., Aroke E. The pace of biological aging mediates the relationship between internalized chronic pain stigma and pain-related disability. J. Pain. 2024;25(4, Supplement):43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2024.01.201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agbor F., Stoudmire T., Goodin B., Aroke E. Stronger social support with friends correlate with a slower pace of biological aging. J. Pain. 2024;25(4, Supplement):43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2024.01.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroke, E.N., Jackson, M., Overstreet, D.S., Penn, T.M., Quinn, T., Sims, A.M., Long, D.L., Goodin, B.R. 2020. Depression Mediate the Relationship Between Social Status and Chronic Pain for Whites, but Not Blacks. Sigma’s 31st International Nursing Research Congress. Abu Dhabi, United Emerald.

- Aroke E.N., Jackson P., Overstreet D.S., Penn T.M., Rumble D.D., Kehrer C.V., Michl A.N., Hasan F.N., Sims A.M., Quinn T., Long D.L., Goodin B.R. Race, social status, and depressive symptoms: a moderated mediation analysis of chronic low back pain interference and severity. Clin. J. Pain. 2020;39(9):658–666. doi: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroke E.N., Jackson P., Meng L., Huo Z., Overstreet D.S., Penn T.M., Quinn T.L., Cruz-Almeida Y., Goodin B.R. Differential DNA methylation in Black and White individuals with chronic low back pain enrich different genomic pathways. Neurobiol. Pain. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ynpai.2022.100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroke E.N., Jackson P., Meng L., Huo Z., Overstreet D.S., Penn T.M., Quinn T.L., Cruz-Almeida Y., Goodin B.R. Differential DNA methylation in black and white individuals with chronic low back pain enrich different genomic pathways. Neurobiol Pain. 2022;11 doi: 10.1016/j.ynpai.2022.100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroke E.N., Srinivasasainagendra V., Kottae P., Quinn T.L., Wiggins A.M., Hobson J., Kinnie K., Stoudmire T., Tiwari H.K., Goodin B.R. The pace of biological aging predicts nonspecific chronic low back pain severity. J. Pain. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2023.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroke E.N., Wiggins A.M., Hobson J.M., Srinivasasainagendra V., Quinn T.L., Kottae P., Tiwari H.K., Sorge R.E., Goodin B.R. The pace of biological aging helps explain the association between insomnia and chronic low back pain. Mol. Pain. 2023;19 doi: 10.1177/17448069231210648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee M.J., Jaffe A.E., Corrada-Bravo H., Ladd-Acosta C., Feinberg A.P., Hansen K.D., Irizarry R.A. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(10):1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Rieger J., Turney I.C., Vonk J.M.J., Esie P., Seblova D., Weir V.R., Belsky D.W., Manly J.J. Socioeconomic status, biological aging, and memory in a diverse national sample of older US men and women. Neurology. 2022;99(19):e2114–e2124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000201032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky D.W., Caspi A., Corcoran D.L., Sugden K., Poulton R., Arseneault L., Baccarelli A., Chamarti K., Gao X., Hannon E. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. eLife. 2022;11:e73420. doi: 10.7554/eLife.73420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernabeu E., McCartney D.L., Gadd D.A., Hillary R.F., Lu A.T., Murphy L., Wrobel N., Campbell A., Harris S.E., Liewald D., Hayward C., Sudlow C., Cox S.R., Evans K.L., Horvath S., McIntosh A.M., Robinson M.R., Vallejos C.A., Marioni R.E. Refining epigenetic prediction of chronological and biological age. Genome Med. 2023;15(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13073-023-01161-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw H., Friedrich C.M., Cole P., Eccleston C., Serfaty M., Stewart G., White S., Moore R.A., Phillippo D., Pincus T. Antidepressants for pain management in adults with chronic pain: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014682.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branham E.M., McLean S.A., Deliwala I., Mauck M.C., Zhao Y., McKibben L.A., Lee A., Spencer A.B., Zannas A.S., Lechner M., Danza T., Velilla M.A., Hendry P.L., Pearson C., Peak D.A., Jones J., Rathlev N.K., Linnstaedt S.D. CpG methylation levels in HPA axis genes predict chronic pain outcomes following trauma exposure. J. Pain. 2023;24(7):1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2023.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou R., Qaseem A., Snow V., Casey D., Cross J.T., Jr., Shekelle P., Owens D.K. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007;147(7):478–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborators G.L.B.P. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(6):e316–e329. doi: 10.1016/s2665-9913(23)00098-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Almeida Y., Cardoso J., Riley J.L., 3rd, Goodin B., King C.D., Petrov M., Bartley E.J., Sibille K.T., Glover T.L., Herbert M.S., Bulls H.W., Addison A., Staud R., Redden D., Bradley L.A., Fillingim R.B. Physical performance and movement-evoked pain profiles in community-dwelling individuals at risk for knee osteoarthritis. Exp. Gerontol. 2017;98:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Almeida Y., Johnson A., Meng L., Sinha P., Rani A., Yoder S., Huo Z., Foster T.C., Fillingim R.B. Epigenetic age predictors in community-dwelling adults with high impact knee pain. Mol. Pain. 2022;18 doi: 10.1177/17448069221118004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas A.G., Cole S.W., Belsky D.W., McSorley A.-M., Shon J.M., Chang V.W. Multi-discrimination exposure and biological aging: results from the midlife in the United States study. Brain Behav. Immunity - Health. 2024;39 doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2024.100774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ruddere L., Craig K.D. Understanding stigma and chronic pain: a-state-of-the-art review. Pain. 2016;157(8):1607–1610. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanooni D., Carrico A.W., Williams R., Glynn T.R., Moskowitz J.T., Pahwa S., Pallikkuth S., Roach M.E., Dilworth S., Aouizerat B.E., Flentje A. Sexual minority stress and cellular aging in methamphetamine-using sexual minority men with treated HIV. Psychosom. Med. 2022;84(8):949–956. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray A.J. Stigma in psychiatry. J. R. Soc. Med. 2002;95(2):72–76. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.95.2.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamczyk M.R., Nevado R.M., Barettino A., Fuster V., Andres V. Biological versus chronological aging: JACC focus seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;75(8):919–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannum G., Guinney J., Zhao L., Zhang L., Hughes G., Sadda S., Klotzle B., Bibikova M., Fan J.-B., Gao Y. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell. 2013;49(2):359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C. Breaking the Cycle of Stigma: The Role of Majority Group Stigmatization in Contributing to Internalized Stigma Among Racial Minorities. 2023.

- Hickling L.M., Allani S., Cella M., Scott W. A systematic review with meta-analyses of the association between stigma and chronic pain outcomes. Pain. 2024 doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000003243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holubova M., Prasko J., Ociskova M., Marackova M., Grambal A., Slepecky M. Self-stigma and quality of life in patients with depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016;12:2677–2687. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S118593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10):R115. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S., Raj K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018;19(6):371–384. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence K.G., Kresovich J.K., O'Brien K.M., Hoang T.T., Xu Z., Taylor J.A., Sandler D.P. Association of neighborhood deprivation with epigenetic aging using 4 clock metrics. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(11):e2024329. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M.E., Lu A.T., Quach A., Chen B.H., Assimes T.L., Bandinelli S., Hou L., Baccarelli A.A., Stewart J.D., Li Y. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 2018;10(4):573. doi: 10.18632/aging.101414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D., Chen J., Perrone-Bizzozero N., Bustillo J.R., Du Y., Calhoun V.D., Liu J. Characterization of cross-tissue genetic-epigenetic effects and their patterns in schizophrenia. Genome Med. 2018;10(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0519-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu A.T., Quach A., Wilson J.G., Reiner A.P., Aviv A., Raj K., Hou L., Baccarelli A.A., Li Y., Stewart J.D. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11(2):303. doi: 10.18632/aging.101684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu A.T., Seeboth A., Tsai P.C., Sun D., Quach A., Reiner A.P., Kooperberg C., Ferrucci L., Hou L., Baccarelli A.A., Li Y., Harris S.E., Corley J., Taylor A., Deary I.J., Stewart J.D., Whitsel E.A., Assimes T.L., Chen W., Li S., Mangino M., Bell J.T., Wilson J.G., Aviv A., Marioni R.E., Raj K., Horvath S. DNA methylation-based estimator of telomere length. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11(16):5895–5923. doi: 10.18632/aging.102173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni R.E., Shah S., McRae A.F., Chen B.H., Colicino E., Harris S.E., Gibson J., Henders A.K., Redmond P., Cox S.R., Pattie A., Corley J., Murphy L., Martin N.G., Montgomery G.W., Feinberg A.P., Fallin M.D., Multhaup M.L., Jaffe A.E., Joehanes R., Schwartz J., Just A.C., Lunetta K.L., Murabito J.M., Starr J.M., Horvath S., Baccarelli A.A., Levy D., Visscher P.M., Wray N.R., Deary I.J. DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0584-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C.L., Ghastine L., Lodge E.K., Dhingra R., Ward-Caviness C.K. Understanding health inequalities through the lens of social epigenetics. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2022;43:235–254. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052020-105613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics DoHI. Back, lower limb, and upper limb pain among U.S. adults, 2019. 2021.

- Overstreet D.S., Strath L.J., Hasan F.N., Sorge R.E., Penn T., Rumble D.D., Aroke E.N., Wiggins A.M., Dembowski J.G., Bajaj E.K., Quinn T.L., Long D.L., Goodin B.R. Racial differences in 25-hydroxy vitamin D and self-reported pain severity in a sample of individuals living with non-specific chronic low back pain. J. Pain Res. 2022;15:3859–3867. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S386565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn T.M., Overstreet D.S., Aroke E.N., Rumble D.D., Sims A.M., Kehrer C.V., Michl A.N., Hasan F.N., Quinn T.L., Long D.L., Trost Z., Morris M.C., Goodin B.R. Perceived injustice helps explain the association between chronic pain stigma and movement-evoked pain in adults with nonspecific chronic low back pain. Pain Med. 2020;21(11):3161–3171. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna L., Zhang Y., Mons U., Holleczek B., Saum K.U., Brenner H. Epigenetic age acceleration predicts cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in a German case cohort. Clin. Epigenetics. 2016;8:64. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0228-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perugino F., De Angelis V., Pompili M., Martelletti P. Stigma and Chronic Pain. Pain Ther. 2022;11(4):1085–1094. doi: 10.1007/s40122-022-00418-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polsky L.R., Rentscher K.E., Carroll J.E. Stress-induced biological aging: a review and guide for research priorities. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022;104:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2022.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz U., Bierbauer W., Lüscher J. Social stigma, mental health, stress, and health-related quality of life in people with long COVID. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2023;20(5) doi: 10.3390/ijerph20053927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva C.T., Young J.I., Zhang L., Gomez L., Schmidt M.A., Varma A., Chen X.S., Martin E.R., Wang L. Cross-tissue analysis of blood and brain epigenome-wide association studies in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):4852. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32475-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade S.C., Molloy E., Keating J.L. Stigma experienced by people with nonspecific chronic low back pain: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2009;10(1):143–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangl A.L., Earnshaw V.A., Logie C.H., van Brakel W., Simbayi L.C., Barré I., Dovidio J.F. The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touleimat N., Tost J. Complete pipeline for Infinium((R)) Human Methylation 450K BeadChip data processing using subset quantile normalization for accurate DNA methylation estimation. Epigenomics. 2012;4(3):325–341. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M., Ormel J., Keefe F.J., Dworkin S.F. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh O.C., Byrne D.G., Nicholas M.K. Internalized stigma in people living with chronic pain. J. Pain. 2014;15(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C.K.W., Mak R.Y.W., Kwok T.S.Y., Tsang J.S.H., Leung M.Y.C., Funabashi M., Macedo L.G., Dennett L., Wong A.Y.L. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with non-specific chronic low back pain in community-dwelling older adults aged 60 years and older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pain. 2022;23(4):509–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannatos I., Stites S.D., Boen C., Xie S.X., Brown R.T., McMillan C.T. Epigenetic age and socioeconomic status contribute to racial disparities in cognitive and functional aging between Black and White older Americans. MedRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.09.29.23296351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.