Abstract

Background

Effective physician-patient communication is crucial to compassionate healthcare, particularly when conveying life-altering diagnoses such as those associated with congenital heart diseases. Despite its importance, medical practitioners often face challenges in communicating effectively. Because of these gaps, we aim to introduce a simulation-based training protocol to improve pediatric cardiology trainee’s communication skills. This study will be conducted in collaboration with associations supporting caregivers of children with congenital heart disease. It strives to demonstrate how specific training programs can efficiently foster humanistic, patient-centered care in standard medical practice.

Methods

This multicenter, open-label randomized controlled trial will be conducted in pediatric cardiac units and simulation centers of across 10 universities in France. The study population comprises pediatric cardiologists in training (including pediatric cardiac fellows or specialist assistants). The SIMUL-CHD intervention will consist of simulation-based training with standardized patients, focusing on improving communication skills for pediatric cardiology trainees during diagnostic counselling. Patients and caregivers have been recruited from a National Patient Association named “Petit Cœur de Beurre”. The primary outcome is the quality of physicians’ communication skills. The evaluation committee, which will review video recordings of the sessions, will be blinded to which participants received simulation-based training (group of interest) and which received theory-based training (control group). Secondary outcomes are the effect of SIMUL-CHD on empathy and anxiety levels in young pediatric cardiologists. Baseline scores pre and post-intervention will be compared, and skill improvement resulting from the intervention measured.

Discussion

Simulation-based training has proven efficacy in teaching technical skills in various scenarios however its application to communication skills in pediatric cardiology remains unexplored. The involvement of experienced parents provides a unique perspective, incorporating their profound understanding of the emotional challenges and specific hurdles faced by families dealing with congenital heart disease.

Trial registration

This trial is registered with the OSF registry (registered https://osf.io/ed78q).

Keywords: Pediatric cardiology, Communication skills, Simulation-based training, Congenital heart disease, Medical education, Breaking bad news, Physician-patient communication, Patient-centered care, Empathy

Background

Congenital heart disease (CHD) affects 8:1000 live births with disease severity ranging from mild to severe and potentially life-threatening [1]. The management of CHD has evolved significantly over the past century however despite significant advancements in medicine, many CHD diagnoses still lack a cure and substantial comorbidity persists (such as cardiovascular or neurodevelopmental sequelae). In recent times, there has been a shift in focus from survival to enhancing the quality of life for children with CHD and their families [2–4]. Parents of children with CHD are at a higher risk of experiencing depression and anxiety [5]. Moments of particular concern for these emotional challenges arise during the initial diagnosis and around the time of surgical interventions. “Bad news” in the context of diagnosis often refers to more than the diagnosis itself. For many parents, it includes the prospect of prolonged hospital stays, open-heart surgeries (often multiple in the child’s early years), potential heart transplantation, and ongoing medical complications, such as growth failure, feeding difficulties, and neurodevelopmental or behavioral issues. Parents of children with CHD frequently endure long periods away from home, which adds strain to family relationships, marriages, and finances [6]. In addition, parents must cope with the emotional weight of mourning the loss of the “normal” child they had expected, often grappling with feelings of guilt, grief, and anger, which put them at an increased risk for mental health challenges such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder [7]. Heightened levels of stress have been observed following the postnatal diagnosis of CHD in newborns, during a period of postpartum vulnerability for couples [6]. Parental stress and anxiety have an important physiological impact on children and have been associated with poorer neurological development in children with heart conditions [8]. This risk is additionally exacerbated in cases where the mother experiences postpartum depression [9]. Therefore, effective communication between the pediatric cardiologist and the caregivers of children with CHD plays a crucial role, not only in circumstances where a “cure” is not achievable. It is thus paramount that every physician with a holistic approach to healthcare should be able to develop “caring” skills. The way in which pediatric cardiologists communicate this diagnosis, manage expectations, and guide parents through treatment plays a pivotal role in helping families cope and prepare for the road ahead [10]. However, such skills are significantly underrepresented in medical education and even more rarely addressed in research protocols.

In France, approximately 65 to 70% of severe CHD is detected during prenatal screening. Consequently, a substantial portion of CHD diagnoses is anticipated to occur during the postnatal period [11]. This pivotal first interaction often takes place at the newborn or child’s bedside, in the presence of exhausted parents, usually at the time of initial echocardiography and can be impacted by other commitments including on-call duties, and with minimal supervision. This practical training gap, focusing on medical skills rather than humanistic ones, is not aligned with the approach of new medical educations reforms in France. It also contradicts the commonly emphasized principle of “never the first time on a patient” ; which means that training is required before practicing [12]. The importance of formal training in communication skills has also been acknowledged by the National Academy of Medicine [13]. It is inevitable that pediatric cardiologists will face the challenging responsibility of delivering ‘bad news’ to patients and families, and it is suggested that these initial interactions between the physician and the family could potentially influence patient outcomes, including compliance during follow-up. Despite this, many pediatric cardiology fellowship programs fail to integrate formal communication skills in their curriculum, something that may be easily addressed by simulation-based training.

Simulation-based education involves recreating realistic clinical scenarios in a safe, controlled environment. This allows healthcare professionals to practice practical skills, make critical decisions, and develop interpersonal abilities without risking patient safety. It is increasingly used in both adult and pediatric medicine for training in clinical skills, such as emergency management and resuscitation [14–17]. While some studies have shown the benefits of simulation training for patient-physician communication, it is still underutilized in pediatrics [18–20]. A few studies have demonstrated improved confidence and communication skills through simulation-based learning in oncology [21–24], as well as better communication after resuscitation [25, 26]. In pediatric cardiology, trainees can struggle with the emotional challenges of diagnosis counseling. Anxiety and lack of confidence can hinder their ability to communicate effectively with families. Poor communication during initial CHD diagnosis can lead to feelings of guilt and disappointment in the trainees, significantly affecting their psychological well-being [27, 28].

Research gap

There have been no randomized controlled trials (RCT) published comparing a simulation-based communication training program in providing CHD counselling compared to traditional training methods.

Methods/design

Study aims

Our aim is to investigate the impact of a simulation-based education program on the effectiveness of initial counselling of postnatal diagnoses of CHD among pediatric cardiology trainees. The primary outcome of this study is the effect of our simulation program on communication skills. The secondary outcomes include the impact of the simulation program on performance anxiety prior to the diagnostic disclosure and the level of empathy experienced by participants before the announcement.

Study design and settings

Participants’ characteristics

In the French medical system, there are two key stages. After completing medical school, doctors enter a stage called “internat,” which is equivalent to pediatric cardiology fellows in many countries. During this period, they are in specialized training within a specific medical field (e.g., pediatric cardiology). This training typically lasts 3 to 5 years, during which they rotate through various departments, gaining practical experience under the supervision of senior doctors. After completing their residency, they may take up the role of post-residency position that involves working as a fully licensed doctor but still within a structured training environment. During these two stages, trainees did not received specific communication training skills.

All members of the French national congenital heart disease network (“M3C”) comprising 10 number of centers, with pediatric cardiology trainees within their institutions will be invited to take part in the study. The study period will be 6 months. All pediatric cardiology trainees (pediatric cardiology fellows, post-residency assistants) irrespective of the stage in training will be included within the study. Participants without a high proficiency in the French language will be excluded to control for any bias in communication attributed to language. Pediatric cardiology trainees who have recently undertaken training in diagnostic counselling in the year prior to assessment will also be excluded in order to maintain homogeneity of prior skills.

Study design

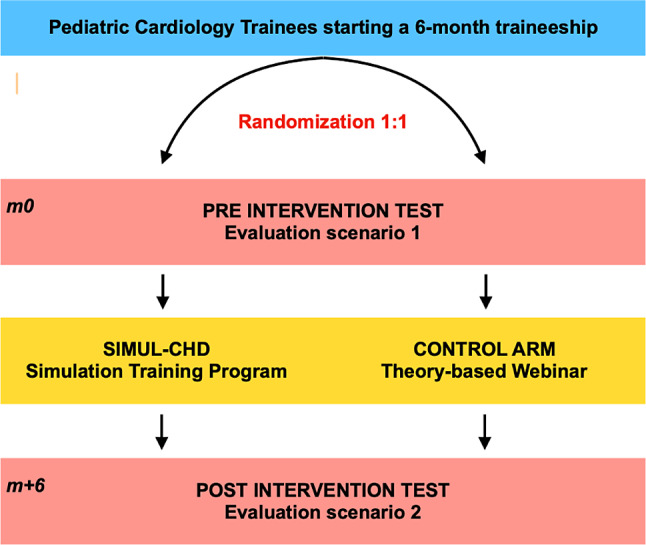

This is a multicenter, randomized, superiority trial conducted over 10 university hospitals and tertiary pediatric cardiac centers in France (SIMUL-CHD trial) with a study period of 6 months. Figure 1 describes the study design. Participants are recruited into the study following initial eligibility assessment and consent procedures. The steering committee will proceed with randomization using a computer-generated allocation sequence. Randomization will be stratified by center and by the level achieved during the study, with two strata: [1] pediatric cardiology fellows [2] post-residency assistants.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study design. m0 represents “Month 0” the beginning of the study period and m + 6 represents the end of the study period “six month later”

Simulated parents

To enhance the authenticity of our simulation, we propose the inclusion of simulated parents, individuals who have personally faced the challenges associated with a diagnosis of CHD. Simulated parents in this study are standardized parents who have undergone training to be able to train medical students and young physicians : there are not actors but actual parents of the national association “Petit Coeur de Beurre”’. Family and caregiver involvement will be entirely voluntary, and they will not receive compensation for participating in the study. They will be selected by the association’s director based on the fact that their child’s CHD is in the past, allowing them the emotional distance needed to engage in our study. By incorporating the perspectives of simulated parents, we aim to provide a more authentic and emotionally resonant learning experience for pediatric cardiologists. This approach aligns with the ‘patient-centered’ medical philosophy endorsed by the World Health Organization, advocating for the active involvement of patients and the public in medical care, education, and research [29].

Primary outcome definition

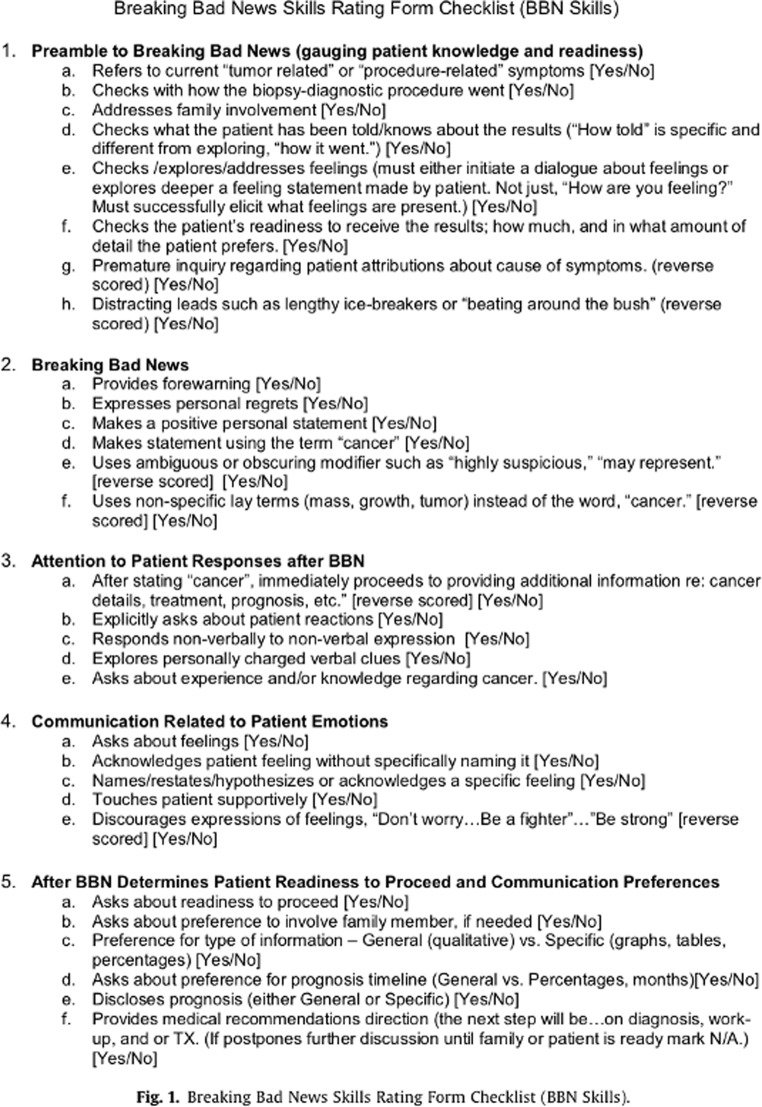

The primary endpoint is the change from baseline between initial and final scores for dimension 2 “Breaking Bad News (BBN)” skills form (Fig. 2) following intervention. The BBN skills will be completed by the evaluation committee using videos and blinded to the intervention. This mean variation will be compared between the two groups. The evaluation committee will be composed of a senior pediatric cardiologist, a clinical psychologist specializing in diagnostic counseling and a member of the national parents’ association (“Petit Coeur de Beurre”). The mean of the three scores will be calculated to evaluate the primary outcome.

Fig. 2.

Breaking Bad News Skills Form (Gorniewicz et al., Patient Educ Couns 2017). The BBN questionnaire was originally designed for use in oncology; it will be translated and adapted for broader use in France, whether for breaking bad news to a patient and their family, in pediatrics or adult medicine

The BBN is a checklist of skills or actions to be performed during the breaking of bad news, which will be assessed with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses. Some items are reverse-scored. The score comprises 30 questions in total, but the maximum possible score is 24. This score is divided into five sections that correspond to the overall competencies expected during a diagnostic announcement. The first section addresses the preamble to delivering bad news and consists of eight items (two of which are reverse-scored). The second section pertains to the direct action of announcing the bad news and includes six items (two of which are also reverse-scored). The third section focuses on the attention given to the reactions of the patient or their relatives following the announcement, comprising five items, one of which is reverse-scored. The fourth section relates to the communication regarding the emotions of the patient (or their relatives) after the announcement and consists of five items (one of which is reverse-scored). Finally, the last section evaluates the patient’s or their relatives’ readiness to consider next steps and their preferences for communication following the announcement, comprising six items. The assessment form will be used within the study to evaluate the effectiveness of the diagnostic counselling session. The BBN Skills form was chosen due its comprehensive assessment of communication skills when delivering bad news [24]. Initially used in adult oncology and in the English language, it will be translated into French and adapted for use in any diagnostic counselling scenario. Psychometric validation will be carried out in an ancillary study.

Video recording evaluation

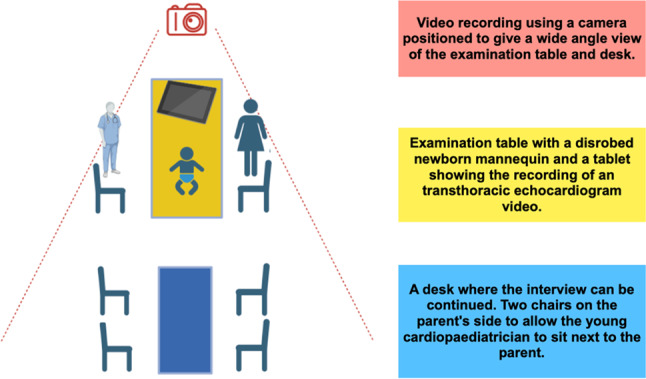

The video recording will be standardized and the participants in the pre- and post-evaluation scenarios will be equipped with microphones to ensure good quality audio (Fig. 3). The evaluation scenarios will include the diagnostic counselling of a simple form of CHD, for example : “postnatal detection of a ventricular septal defect requiring surgery in the first year of life”. The pediatric cardiology trainees will be expected to carry out this simulation with a “parent” acting within the scenario. The parent will have prior experience and training to perform and react appropriately within the scenario. The parents’ responses to the words and actions of the pediatric cardiology trainees will be standardized and reproducible. The scenario will begin with a visualization of several clips of transthoracic echocardiography. The diagnosis of the congenital heart disease will be revealed at the end of the video and the main principles of management will be outlined to the participant to standardize for any knowledge differences between the trainees. The aim is to assess communication skills and not CHD knowledge proficiency.

Fig. 3.

Standardized floor plan for evaluating diagnostic announcement scenarios. The setup includes a video recording camera for a wide-angle view, a table with a newborn mannequin and echocardiogram display, and a desk with chairs for the cardiopaediatrician and parent, facilitating realistic communication scenarios

Secondary outcome definition

During the study duration, baseline and final evaluations will be performed and recording. Performance anxiety and empathy are key psychological factors that can influence performance and interactions in the medical field. These two secondary parameters will also be assessed by questionnaires and the change from baseline will be compared within the two groups:

Empathy will be assessed using the Jefferson Scale of Physician’s Empathy (JSPE) questionnaire.

Anxiety will be assessed using the self-assessment of performance anxiety with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) questionnaire.

The JSPE is a self questionnaire consisting of 20 items, ten of which are inverted (i). Each item is rated from 1 to 7 on a Likert scale, corresponding respectively to “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree”. The items are divided as follows into the three sub-components of cognitive empathy:

Perspecting taking (ability to understand the patient’s perspective): items 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 17 and 20 (sub-scores from 10 to 70).

Compassionate care: items 1(i), 7(i), 8(i), 11(i), 12(i), 14(i), 18(i) and 19(i) (sub-score from 8 to 56).

The ability to walk in the patient’s shoes: items 3(i) and 6(i) (sub-scores from 2 to 14).

The overall score obtained from the questionnaire ranges from 20 to 140. The higher the score, the greater the empathy estimated by the participant. This scale is widely used throughout the world. Its reliability and validity have been verified by the authors at the time of its creation [30, 31] and in a follow-up cross-cultural study in 2014, confirming that the 3 components of this scale remain stable even in different cultures [32]. Its internal consistency was determined by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80. The JSPE has been validated in French [33]. In addition, the JSPE has already been used to assess the empathy of medical fellows in several other studies [34–36].

In order to assess performance anxiety, we selected the STAI questionnaire [37, 38].The STAI is a widely recognized psychometric tool for assessing anxiety in individuals in specific situations [39–42]. The STAI consists of two distinct parts: the State Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Trait Anxiety Scale (TAS). The SAS assesses the temporary or transient anxiety that individuals may experience in specific situations, while the TAS assesses general or lasting anxiety in individuals, regardless of the situation. The STAI questionnaire is composed of several items scored on a Likert scale, where participants indicate their degree of agreement with the proposed statements. It provides quantitative scores that can be used to measure the intensity of anxiety experienced by individuals. The STAI is widely used in psychological research and has demonstrated its reliability and validity. It has also been validated in French [43]. We believe it can be used to assess performance anxiety specific to situations where patients are given bad news. Thus, using the STAI in this study will make it possible to collect objective data on the performance anxiety of the participants prior to delivering difficult news to the patient and their families.

Ancillary studies

Two ancillary study are planned

Translation in French and psychometric validation of the BBN Skills communication performance score for future use.

Qualitative evaluation of the simulation session in the SIMUL-CHD arm.

The “SIMUL-CHD” program and the comparative group

The “SIMUL-CHD” program

The SIMUL-CHD training program is a comprehensive, one-day simulation-based workshop that aims to improve pediatric cardiology trainees’ communication skills. The training program integrates theoretical learning with hands-on simulation exercises, designed to foster empathy, improve clarity in communication, and provide participants with essential tools to handle emotionally charged medical situations. The design of the program reflects the feedback and input from senior cardiologists, psychologists, and actual parents of children with CHD. This collaboration ensures a holistic approach to communication training. The course is designed for small groups of five participants, allowing for intensive and personalized learning. These participants are pediatric cardiology trainees at various stages of their careers. This multidisciplinary setup ensures that the training is applicable to all levels of experience, while small group sizes enable each participant to engage deeply in both simulated scenarios and debriefing sessions.

The SIMUL-CHD training is delivered by a multidisciplinary team, including:

A senior pediatric cardiologist, who brings medical expertise and shares their experience in delivering difficult diagnoses.

A psychologist, who focuses on the emotional and psychological impact of delivering and receiving bad news.

Two simulated parents, real parents of children with CHD, who share their lived experiences and participate in the simulated scenarios. One parent engages directly in the role-play scenarios, while the other joins the debriefing to offer authentic insights into the parent’s perspective.

Program Structure:

The morning session focuses on theoretical knowledge, with contributions from each of the trainers:

Senior Pediatric Cardiologist : The cardiologist explains the process of delivering bad news, focusing on organization, body language, verbal and non-verbal communication, and managing both the physician’s and the family’s expectations. Key points include how to manage complex medical information and the physician’s role in supporting the family emotionally.

Psychologist : The psychologist provides insights into the psychological impact of these communications, emphasizing how stress and emotional states can affect both the physician’s delivery and the family’s reception of the news. They also discuss strategies for managing difficult emotional responses during these interactions.

Simulated Parents : parents shares what they wish doctors would know when delivering a diagnosis. Their testimony is aimed at helping trainees understand the emotional weight and expectations parents have during these critical conversations.

After a brief break, participants are encouraged to share their own experiences of delivering bad news, whether positive or negative. This open discussion allows for peer learning and reflection, with input from both the psychologist and the parent, providing an emotionally safe environment for trainees to discuss challenges they have faced. These experiences are then linked back to the theoretical concepts discussed earlier.

The afternoon session is dedicated to hands-on simulated scenarios. Each participant will take on the role of the “main announcer,” or “co-announcer. Each simulation consists of three phases: the announcement, the debriefing, and peer feedback.

Each scenario simulates a real-life situation where a trainee must communicate a difficult diagnosis. The trainees must explain the medical implications of the diagnosis, including possible treatments and outcomes, while managing the emotional needs of the parents. These scenarios are designed to cover a range of emotional and cognitive challenges, from parents in shock to those with numerous questions and fears about the future. After each simulation, participants receive structured feedback from the trainers and peers. The debriefing is structured using the “plus-delta” approach, focusing on what was done well and what could be improved. The presence of the partner parent in the debriefing adds an authentic perspective, highlighting the emotional nuances that may have been missed by the trainees. Formative assessment takes place throughout the day during the debriefing sessions. Trainees receive real-time feedback on their communication style, empathy, and ability to handle emotionally charged situations. These assessments are not graded but are meant to foster growth and reflection. All sites will use the same set of simulated scenarios, with scripts carefully designed to cover a variety of communication challenges. The trainers, including cardiologists, psychologists, and parents, will undergo a standardized preparation session to ensure consistency in feedback and debriefing methods. The same trainers will be used across all sites.

To reduce bias, the parent/caregiver taking part in the training program will be different to those participating in the evaluation scenarios. Similarly, the scenarios used during the simulation program will be different from those used in the evaluation scenarios.

The comparative group

In order to avoid bias of over-evaluation of the effect of our simulation program by the “simple” fact of giving more time for training, we are going to implement an online training webinar sufficiently relevant for the control arm. The webinar will last approximately 3 h and will be organized into three to four presentations. These presentations will be delivered by pediatric cardiologists, psychologists, and parents, each offering unique perspectives on delivering difficult news. Also, employing a control group receiving standardized theoretical training can be regarded as ethically sound, ensuring access to a form of training for all study participants.

Study design and statistical methods

Sample size calculation

The study by Gorniewicz et al. (2017) concluded that if dimension 2 (“Breaking Bad News”) is retained, a sample of 18 people in each group will have 90% power to detect a difference in mean of -1.3 (the difference between a control group mean, µ₁, of -0.25 and an intervention group mean, µ₂, of 1.05) assuming a common standard deviation of 1.14, using a Student’s t-test with a two-tailed significance level of 5% (NQuery software). With a non-exploitable data rate of around 10%, we concluded that it would be necessary to include 20 subjects per group.

Study timeline and feasibility

In France, resident and post-resident juniors rotate between departments every six months which provides a predictability with participant availability. The major pediatric cardiac referral centers enroll 5 to 10 pediatric cardiology trainees and the centers of pediatric cardiac expertise support 1 and 5 pediatric cardiology trainees. The feasibility of the study over a six-month period is therefore guaranteed. The study will start in in May 2025 and end in November 2025. During this six-month period, all participants will undergo an initial evaluation, followed by training based on randomization, and finally, a concluding evaluation. The participant timeline is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Timeline

| STUDY PERIOD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolment | Allocation | Post-allocation | ||||

| TIMEPOINT* | M0 | M1 | M2 | M5 | M6 | |

| ENROLMENT: | ||||||

| Eligibility screen | X | |||||

| Informed consent | X | |||||

| Allocation | X | |||||

| INTERVENTIONS: | ||||||

| SIMUL-CHD program group | ||||||

| Theory-based training group | ||||||

| ASSESSMENTS: | ||||||

| Baseline variable | X | |||||

| Primary outcome (BBN skills form by video assessment) | X | X | ||||

| Secondary outcome ( SCAI & JSCE) | X | X | ||||

| Qualitative assessment of the Simulation program | X | X | ||||

• Timepoint : M0, M1, M2, M5 and M6 represents month of the study period

Data analysis plan

A descriptive analysis of the initial characteristics of each group will be conducted. Qualitative variables will include the sample size and the frequency of different modalities. Quantitative variables will include the sample size, mean, standard deviation, median, and extreme values (minimum and maximum). The comparability of the two groups before treatment will be assessed for all initial characteristics. In case of non-comparability on one or more parameters that may influence the efficacy criteria, an adjustment may be made on these parameters for the intergroup comparisons of the outcome measures as part of a sensitivity analysis.

The analysis of efficacy outcome measures will be conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. Each doctor will be analyzed to their randomized group regardless of protocol deviations.

The difference between the initial and final scores for dimension 2 “Breaking Bad News” skills questionnaire will be compared between the two groups using a Student’s t-test if the distribution is parametric or using a Mann-Whitney test if the distribution is non-parametric. The effect size (Cohen’s d) and its 95% confidence interval will be assessed. The following secondary criteria will be analyzed using the same strategy as the primary criterion: [1] difference between initial and final scores for the other 4 dimensions of “BBN Skills” evaluated by the evaluation committee [2] self-assessment by the paediatric cardiology trainees of performance anxiety before and after the intervention [3] self-assessment of trainee empathy and [4] concordance between different assessments of the BBN Skills score.

A test will be considered statistically significant if the p-value is less than the 5% significance threshold. The analyses will be conducted using the SAS or R software after the database is locked and the Statistical Analysis Plan is approved.

Discussion

Our study protocol, SIMUL-CHD, addresses the unique challenges in successful communication during the period of initial diagnostic counselling of CHD by pediatric cardiologists to patients and their families. The intricacies of child/parent-physician relationships in the context of postnatal detection of CHD underscore the need for a nuanced and practical simulation-based training approach. Our protocol addresses this challenge by utilizing a simulation-based approach that combines both theoretical and practical elements, creating a comprehensive learning experience designed to improve physician-patient-family interactions.

The inclusion of real parents as standardized patients in our simulations is a particularly innovative aspect of this study. While simulated patients have been employed in medical education since the 1960s, the specific use of parents in pediatric settings—particularly within cardiology—remains largely unexplored. This approach introduces a personal and experiential element that goes beyond the standard simulated patient model. The inclusion of parents who have personally experienced the challenges of raising a child with CHD adds an unparalleled layer of authenticity to the simulation. This experiential component allows trainees to engage with the emotional realities of families in a way that goes beyond traditional simulation models. To our knowledge, no prior studies have employed this approach specifically in pediatric cardiology. We anticipate that this model could be adapted for use in other pediatric subspecialties or chronic disease areas where effective communication is paramount. This study could shift the broader medical education paradigm toward integrating real patients and caregivers as standardized patients, fostering a deeper, more empathetic approach to clinical care.

Despite the potential benefits, the SIMUL-CHD study has several limitations. First, the training of simulated parents may introduce variability, as it relies heavily on the personal experiences and emotional authenticity of the parents involved. Standardizing this component across multiple training sites is challenging and may affect the uniformity of the educational experience.

Second, while the study's small group size allows for personalized feedback and interaction, it may limit the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, we must consider the possibility that the effects observed in a controlled, simulated environment may not fully translate to real-world clinical settings, where emotional and time pressures can vary significantly.

Lastly, our study focuses primarily on the technical and emotional aspects of delivering a diagnosis. While this is crucial, further studies are needed to assess how these communication improvements impact long-term family outcomes, including parental coping, adherence to medical recommendations, and the child's health trajectory.

Conclusion

The SIMUL-CHD protocol addresses the intricate challenges of communication skills training in pediatric cardiology, particularly when delivering a diagnosis of CHD. A key innovation of this study is the involvement of real parents of children with CHD as simulated parents, which we believe will provide trainees with a more realistic and impactful learning experience. This unique approach could pave the way for similar training models in pediatric specialties.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank French National Association “Petit Coeur de Beurre” and “Laboratoire Expérimental de Simulation de Médecine Intensive de l’Université (LESiMU) de Nantes” for their invaluable support.

Abbreviations

- CHD

congenital heart disease

- RCT

randomized controlled trials

- BBN

Breaking Bad News

- JSPE

Jefferson Scale of Physician’s Empathy

- STAI

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- SAS

State Anxiety Scale

Author contributions

Each author has contributed significantly to the submitted work: (a) conception and design (P.P., Q.H., P.A. and A.-E.B.), (b) drafting of the manuscript (P.P., Q.H., A.G., M.-C.P. P.A., A.-E.B.), (c) critical revision for important intellectual content (all authors), (d) final approval of the manuscript submitted (all authors).

Funding

This trial is funded by Cardiogen “filière nationale de santé maladies cardiaques héréditaires ou rares”. By a research grant from the French Federation of Cardiology (to P.P.); by a research grant from the Fondation Maladies Rares (to A.-E.B.); by a research grant from the French Government as part of the “Investments of the future” program managed by the National Research Agency, grant reference ANR-16-IDEX-0007 (to A.-E.B.)

Data availability

The results will be presented at scientific meetings and published in peer reviewed medical journals. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by Ethics Committee of Nantes “Groupe Nantais d’Ethique dans le Domaine de la Santé” (n°24-19-02-270 ). Young Pediatric Cardiologist are only included after informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liu Y, Chen S, Zühlke L, Black GC, Choy MK, Li N, et al. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970–2017: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int J Epidemiol 1 avr. 2019;48(2):455–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abassi H, Huguet H, Picot MC, Vincenti M, Guillaumont S, Auer A, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with congenital heart disease aged 5 to 7 years: a multicentre controlled cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. nov 2020;12(1):366. 10.1186/s12955-020-01615-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Derridj N, Bonnet D, Calderon J, Amedro P, Bertille N, Lelong N, et al. Quality of life of children born with a congenital heart defect. J Pediatr Mai. 2022;244:148–e1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amedro P, Dorka R, Moniotte S, Guillaumont S, Fraisse A, Kreitmann B, et al. Quality of life of children with congenital Heart diseases: a Multicenter controlled cross-sectional study. Pediatr Cardiol déc. 2015;36(8):1588–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner O, El Louali F, Fouilloux V, Amedro P, Ovaert C. Parental anxiety before invasive cardiac procedure in children with congenital heart disease: contributing factors and consequences. Congenit Heart Dis Sept. 2019;14(5):778–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dandy S, Wittkowski A, Murray CD. Parents’ experiences of receiving their child’s diagnosis of congenital heart disease: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature. Br J Health Psychol Mai. 2024;29(2):351–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bainton J, Trachtenberg F, McCrindle BW, Wang K, Boruta R, Brosig CL et al. Prevalence and associated factors of post-traumatic stress disorder in parents whose infants have single ventricle heart disease. Cardiol Young 2023;1–10. 10.1017/S1047951122004012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Roberts SD, Kazazian V, Ford MK, Marini D, Miller SP, Chau V, et al. The association between parent stress, coping and mental health, and neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants with congenital heart disease. Clin Neuropsychol 4 Juill. 2021;35(5):948–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirhosseini H, Moosavipoor S, Ahmad, Nazari MA, Dehghan A, Mirhosseini S, Bidaki R et al. Cognitive Behavioral Development in Children Following Maternal Postpartum Depression: A Review Article. Electron Physician. 20 déc. 2015;7(8):1673–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Tacy TA, Kasparian NA, Karnik R, Geiger M, Sood E. Opportunities to enhance parental well-being during prenatal counseling for congenital heart disease. Semin Perinatol juin. 2022;46(4):151587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vincenti M, Guillaumont S, Clarivet B, Macioce V, Mura T, Boulot P, et al. Prognosis of severe congenital heart diseases: do we overestimate the impact of prenatal diagnosis? Arch Cardiovasc Dis avr. 2019;112(4):261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levraut J, Fournier JP. Jamais La première fois sur le patient ! Ann Fr Médecine Urgence Nov. 2012;2(6):361–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dying in America. Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Academies; 2015. [cité 10 janv 2024]. Disponible sur:. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marker S, Mohr M, Østergaard D. Simulation-based training of junior doctors in handling critically ill patients facilitates the transition to clinical practice: an interview study. BMC Med Educ déc. 2019;19(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stritzke A, Murthy P, Fiedrich E, Assaad MA, Howlett A, Cheng A, et al. Advanced neonatal procedural skills: a simulation-based workshop: impact and skill decay. BMC Med Educ 13 janv. 2023;23(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Lee JH. Effects of simulation-based education for neonatal resuscitation on medical students’ technical and non-technical skills. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12):e0278575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parikh P, Samraj R, Ogbeifun H, Sumbel L, Brimager K, Alhendy M, et al. Simulation-based training in high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation among neonatal intensive care unit providers. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:808992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy DM, Powell RE, Cameron KA, Salzman DH, Papanagnou D, Doty AMB, et al. Simulation-based mastery learning compared to standard education for discussing diagnostic uncertainty with patients in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ déc. 2020;20(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blackmore A, Kasfiki EV, Purva M. Simulation-based education to improve communication skills: a systematic review and identification of current best practice. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn oct. 2018;4(4):159–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz-Blanco S, Boss R. Simulation for communication training in neonatology. Semin Perinatol Nov. 2023;47(7):151821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brock KE, Tracewski M, Allen KE, Klick J, Petrillo T, Hebbar KB. Simulation-based Palliative Care Communication for Pediatric critical care fellows. Am J Hosp Palliat Med sept. 2019;36(9):820–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parle M, Maguire P, Heaven C. The development of a training model to improve health professionals’ skills, self-efficacy and outcome expectancies when communicating with cancer patients. Soc Sci Med janv. 1997;44(2):231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering Bad News: application to the patient with Cancer. Oncologist 1 août. 2000;5(4):302–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorniewicz J, Floyd M, Krishnan K, Bishop TW, Tudiver F, Lang F. Breaking bad news to patients with cancer: a randomized control trial of a brief communication skills training module incorporating the stories and preferences of actual patients. Patient Educ Couns avr. 2017;100(4):655–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian JD, Wu FF, Wen C. Effects of a teaching mode combining SimBaby with standardized patients on medical students’ attitudes toward communication skills. BMC Med Educ. nov 2022;30(1):825. 10.1186/s12909-022-03869-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Johnson EM, Hamilton MF, Watson RS, Claxton R, Barnett M, Thompson AE et al. An Intensive, Simulation-Based Communication Course for Pediatric Critical Care Medicine Fellows: Pediatr Crit Care Med. août. 2017;18(8):e348–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Burn Res sept. 2017;6:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heier L, Schellenberger B, Schippers A, Nies S, Geiser F, Ernstmann N. Interprofessional communication skills training to improve medical students’ and nursing trainees’ error communication - quasi-experimental pilot study. BMC Med Educ 3 janv. 2024;24(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tritter JQ. Revolution or evolution: the challenges of conceptualizing patient and public involvement in a consumerist world. Health Expect sept. 2009;12(3):275–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemmerdinger JM, Stoddart SD, Lilford RJ. A systematic review of tests of empathy in medicine. BMC Med Educ déc. 2007;7(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hojat M. Exploration and confirmation of the latent variable structure of the Jefferson scale of empathy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Hojat. - Exploration and confirmation of the latent variabl.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Emilie Boujut C, Buffel A, Catu-Pinault J-L, Tavani L, Rigal, et al. Development of a French-Language Version of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy and Association with Practice Characteristics and Burnout in a sample of General practitioners the Jefferson Scale of Physician. Int J Person Centered Med. 2012;2(4):759–66. ⟨hal-01473301⟩. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Shanafelt TD, West CP. Impact of resident well-being and empathy on assessments of faculty physicians. J Gen Intern Med janv. 2010;25(1):52–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangione S, Kane GC, Caruso JW, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Hojat M. Assessment of empathy in different years of internal medicine training. Med Teach Juill. 2002;24(4):370–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuen JK, See C, Cheung JTK, Lum CM, Lee JS, Wong WT. Can teaching serious illness communication skills foster multidimensional empathy? A mixed-methods study. BMC Med Educ 11 janv. 2023;23(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spielberger CD, Sharma S. Cross-cultural measurement of anxiety. Dans CD. In: Spielberger, Diaz-Guerrero R, editors. Cross-cultural anxiety. Volume 3. Washington u.C: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1976. pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spielberger CD, Vagg PR. Psychometric properties of the STM: a reply to Ramanaiah, Fransen, and Schill. J Pers Assess. 1984;480:95–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bridou M, Aguerre C. Validity of the French form of the Somatosensory amplification scale in a non-clinical sample. Health Psychol Res 2 janv. 2013;1(1):e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iwata N, Higuchi HR. Responses of Japanese and American university students to the STAI items that assess the presence or absence of anxiety. J Pers Assess févr. 2000;74(1):48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fountoulakis KN, Papadopoulou M, Kleanthous S, Papadopoulou A, Bizeli V, Nimatoudis I, et al. Reliability and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the state-trait anxiety inventory form Y: preliminary data. Ann Gen Psychiatry 31 janv. 2006;5:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kennedy BL, Schwab JJ, Morris RL, Beldia G. Assessment of state and trait anxiety in subjects with anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychiatr Q. 2001;72(3):263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gauthier J, Bouchard S. Adaptation canadienne-française de la forme révisée du state–trait anxiety Inventory De Spielberger. Can J Behav Sci Rev Can Sci Comport oct. 1993;25(4):559–78. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The results will be presented at scientific meetings and published in peer reviewed medical journals. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.