Summary

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is a global health issue and a breach of human rights. However, the literature lacks understanding of how socioeconomic and geographic disparities influence women's attitudes toward IPV in Guyana over time. This study aimed to assess trends in women's attitudes about IPV in Guyana.

Methods

Data from three nationally representative surveys from 2009, 2014 to 2019 were analysed. The prevalence of women's attitudes about IPV was assessed, specifically in response to going out without telling their partners, neglecting their children, arguing with their partner, refusing sex with their partner, or burning food prepared for family meals. A series of stratified subgroup analyses were also completed. We assessed trends in IPV using the slope index of inequality (SII) and the concentration index of inequality (CIX). We used multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression to assess factors associated with women's attitudes justifying IPV.

Findings

The prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV for any of the five reasons declined from 16.4% (95% CI: 15.1–17.8) in 2009 to 10.8% (95% CI: 9.7–12.0) in 2019. Marked geographic and socioeconomic inequalities were observed among subgroups. The SII for any of the five reasons decreased from −20.02 to −14.28, while the CIX remained constant over time. Key factors associated with women's attitudes about IPV were area of residence, sex of the household head, marital status, respondent's level of education, wealth index quintile, and the frequency of reading newspapers/magazines.

Interpretation

From 2009 to 2019, Guyana was able to reduce women's attitudes justifying IPV against women by 34.1% and shortened subgroup inequalities. However, the prevalence remained high in 2019, with persisted inequalities among subgroups. Effective strategies, including the use of media to raise awareness, promotion of community-based approaches, and educational campaigns focusing on geographic and socioeconomic disparities, are essential for continuing to reduce the prevalence of IPV and associated inequalities.

Funding

The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center grant number D43TW012189.

Keywords: Attitudes, Domestic violence, Intimate partner violence, Violence against women, Guyana

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Domestic violence against women is a global public health crisis and has far-reaching consequences, such physical and mental health issues, economic instability, disruptions to family and community structures, and increased risk of intergenerational violence. We search PubMed for articles published from database inception from January 1990 to May 2023, with no language restrictions. We used the search term “attitude” AND “Violence” OR “domestic violence” OR “spouse abuse” OR “intimate partner violence” AND “Guyana”. We also used the same terms for articles published in LILACS. We identified only articles that attempted to assess the personal experiences and attitudes towards intimate partner violence in healthcare providers in Guyana. Therefore, we focused our study in assessing women's attitudes about IPV against women in Guyana over the last decade.

Added value of this study

This is the first study conducted in Guyana that examines trends in the prevalence of women's attitudes about IPV against women, utilizing data from the largest epidemiological and demographic surveys conducted from 2009 to 2019. To assess patterns of inequalities in women's attitudes about IPV against women over time, two complex measures of inequalities were computed. We used multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression to assess factors associated with women's attitudes about IPV. We observed that the prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV for any of the five reasons in Guyana declined by 34.1% from 2009 to 2019. However, marked geographic and socioeconomic inequalities persisted among subgroups. Place of residence, sex of the household head, marital status, respondent's level of education, wealth index quintile, and the frequency of reading newspapers/magazines were main factors associated with women's attitudes about IPV.

Implications of all the available evidence

The results of our study underscore the importance of targeted strategies to reduce the prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in Guyana, and to end inequalities among subgroups. It is crucial to implement educational campaigns that focus on geographic and socioeconomic disparities further to reduce justifications for IPV. Effective use of media and the promotion of community-based approaches, such as organizing workshops to educate community members about the negative impacts of IPV, gender equality, and healthy relationship practices, can enhance the reach and impact of anti-IPV messaging. Engaging local leaders to advocate against IPV and implementing school programs to teach children and adolescents about consent, respect, and healthy relationships are also crucial. Additionally, economic empowerment initiatives and strengthening legal frameworks are essential to support vulnerable groups and foster environments where IPV is less likely to be justified or tolerated.

Introduction

The United Nations defines violence against women as any gender-based act leading to physical, sexual, or psychological harm, encompassing threats, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty in public or private life.1 Relatedly, domestic violence against women by an intimate partner is a global societal and health concern.2 For nearly three decades, violence against women has been acknowledged internationally as a widespread crisis that significantly impacts the lives and health of women, constituting a violation of human rights.3 The advocacy for its eradication has been spearheaded by women's health and rights organizations for decades.3 Globally, these efforts gained prominence with key milestones such as the 1993 United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women and the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action. Additionally, various other global and regional conventions and consensus documents have contributed to the institution of public health programs for the elimination of violence against women across the world.3 The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically target 5.2, aspire to eradicate all forms of violence against women and girls, both in public and private spheres.4 This includes addressing issues such as trafficking, sexual exploitation, and other forms of exploitation against women and girls.4 Indeed, this target underscores a profound commitment from the global community to establish a world in which women and girls can exist without the looming threat and consequences of violence. Despite the injustice of physical intimate partner violence (IPV), gauging its prevalence is challenging due to underreporting driven by fear of stigma, gaslighting, intimidation, isolation, economic control, and physical harm.5, 6, 7

In 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that globally, 1 in 3 women (30%) aged 15 years or older experienced physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime, primarily by an intimate or domestic partner.3 However, this global average may not fully capture the nuanced and complex realities within individual countries or sub-regions. In 2019, Bott et al., conducted a comprehensive review and reanalysis of national surveys spanning from 1998 to 2017, focusing on physical and/or sexual IPV in 24 countries across the Americas. They showed that in Brazil, El Salvador, Panama, and Uruguay, the prevalence of women reporting ever experiencing IPV ranged from 13.7% to 16.1%, while in Bolivia, it was notably higher at 52.4%,8 revealing that IPV against women persists as a significant public health and human rights concern throughout the region.8

The high prevalence of physical or sexual violence against women and girls noted across various countries can be attributed to a complex interplay of numerous factors, including societal, gender, religious, cultural, economic, and individual dynamics. In Patriarchal societies rooted in gender norms, individuals may internalize societal beliefs that perpetuate IPV, with women often being the survivors and men the perpetrators.9 Additionally, systemic deficiencies within this patriarchal framework may hinder effective prevention of physical IPV.9 While changing harmful gender norms across society is paramount to preventing all forms of violence against women (and many forms of violence against children, as well), the main target of such efforts should continue to be the protection of girls and women including also boys and men who could be perpetrators and survivors of violence. Indeed, the role and responsibility of men (and of the norms they hold) is a central tenet for the prevention of violence against women and has not been mentioned or discussed enough in studies related to IPV.

Violence against women has far-reaching consequences, impacting the physical and mental health as well as the overall well-being of women, children, and families over short, medium, and long-term periods.10 Moreover, its effects extend to encompass substantial social and economic ramifications for both countries and societies at large.10

In Guyana, IPV against women is socially perceived as a private or familial issue, and often rationalized as a form of punishment or discipline.11 In response to the challenges posed by IPV, Guyana enacted a series of laws and regulations aimed at addressing the pervasive issue of domestic abuse against women and girls.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Guyana also demonstrated its commitment to safeguarding women from IPV by signing and ratifying six key international conventions: the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (1977), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW-1980), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1981), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1999), the Convention Against Torture (1988), and the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women (the Belém do Pará Convention-1995).18

A comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of such interventions on the prevalence of IPV can, therefore, provide insights for crafting and adjusting policies, programs, and campaigns. Changes in women's attitudes justifying IPV can be an important indicator of changes in perception, acceptance, and behaviour. From 2009 to 2019, Guyana has undertaken three nationally representative surveys with valuable data that can be used to assess women's attitudes about IPV against women. In this study, we aimed to assess trends in women's attitudes about IPV in Guyana and its associated factors. Herein we refer to women's attitudes about IPV against women as the attitudes of women in justifying wife's beating by a male partner.

Methods

We used data extracted from three nationally representative surveys: the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS-2009) and the Multiple Indicators Cluster Surveys (MICS 2014 and 2019). These surveys encompassed various demographic, geographic, and attitudinal indicators, capturing information from 15,959 women (4996; 5076 and 5887 women for DHS-2009, MICS 2014 and MICS 2019 respectively) in the reproductive age group (15–49 years). The surveyed parameters included sociodemographic distribution, access to media, and women's attitudes toward wife beating by a male partner.

Utilizing a two-stage sample design, the surveys first selected enumeration districts (EDs) from a master sample. In the second stage, households were systematically sampled from each ED using an updated household listing of the selected EDs. Sample weights were used to adjust for differences in the probabilities of selection of the sample households, and to ensure representativeness of the survey findings both nationally and sub-nationally. Data collection for DHS 2009 took place from March to July 2009; for MICS 2014, it began in April and concluded in July 2014; and for MICS 2019, it ran from June 2019 to February 2020. The Bureau of Statistics and the Ministry of Health conducted the DHS, with technical assistance from ICF Macro and funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)/Guyana under the Measure DHS program. The MICS were also conducted by the Bureau of Statistics, but with technical and financial support from the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the Government of Guyana. Further details on the methodologies and outcomes of DHS and MICS can be found elsewhere.19, 20, 21

Outcomes and variables

Women's attitudes about IPV against women were assessed by both DHS and MICS using unprompted responses to the following questions:19, 20, 21 Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. In your opinion, is a husband right in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations: [a] If she goes out without telling him? [b] If she neglects the children? [c] If she argues with him? [d] If she refuses to have sex with him? [e] If she burns the food? A binary option of answers (Yes/No) was considered for each question. Options of answers “Don't know/Not sure/Depends (DK) were excluded from the analyses.

In this study, the prevalence of women's attitudes about IPV against women was the main outcome we assessed. It was defined as the prevalence of women who believed a husband is justified in beating his wife for any of the following reasons as well as the combination of these five reasons: “goes out without telling him”, “neglects the children”, “argues with him”, “refuses sex with him”, and “burns the food”. Of note, these five reasons were used by DHS and MICS only to assess the social justification for physical violence by a husband in Guyana.

Stratifiers

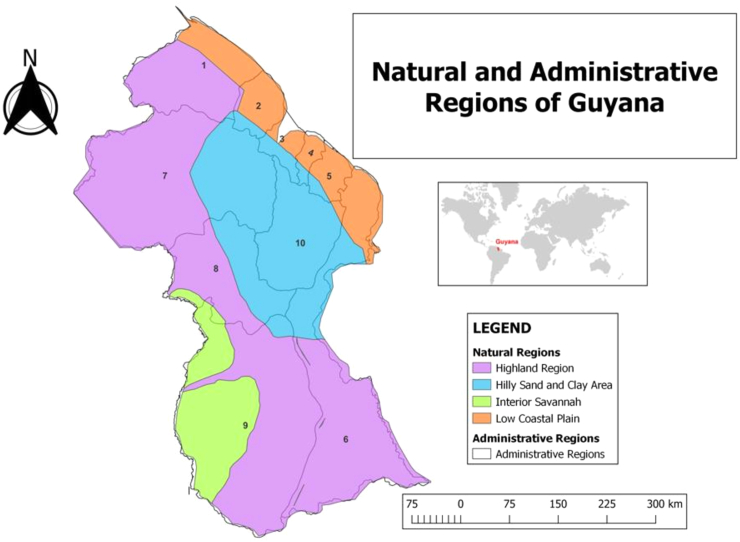

Ten stratifiers were analyzed in this study. The urban-rural place of residence, the coastal and interior place of living, geographic regions (10 administrative regions), women's age (years), biological sex of the household's head (male/female), marital/union status of the women, women's education, wealth asset index, frequency of reading newspaper or magazine, and the frequency of watching television. In both MICS and DHS, the sex of the household head (MICS) was determined by listing the names of each person who usually lives in the household starting with the household head. Then the interviewers asked the following question for each person: Is (name) male or female? This list of variables was selected based on their availability and similarity of the questions in the three surveys as well as their pre-established relationship with IPV against women. Notably, except for coastal and interior places of residence, all other variables are stratifiers commonly used in studies that monitor health inequality worldwide.22,23 The coastal and interior place of living was included in the study for its local significance as the terms urban and rural are rarely used in Guyana. Guyana's 10 administrative regions are categorized into Coastland and Hinterland areas (Fig. 1).24 The Hinterland represents 10.9% of the total population, with the Coastland comprising the remaining 89.1%. Across the regions, approximately 74% of the population resides in rural areas. Moreover, the coastal plain hosts the majority of the non-indigenous population, while the Hinterland regions are predominantly inhabited by Amerindians (Indigenous peoples).24 Region 4, encompassing the capital city of Georgetown, serves as the focal point for Guyana's administrative and economic activities. We refer to the Interior location as synonymous with the Hinterland region.

Fig. 1.

Geographic representation of the ten administrative regions and the Coastal and Hinterland regions in Guyana.

The wealth asset quintile used in this study is pre-calculated in both DHS and MICS through principal component analysis, considering both dwelling characteristics and household asset ownership. This may encompass items such as ownership of television, refrigerator, vehicles, and availability of water and sanitation facilities, among others.19, 20, 21,25 The resulting index is typically divided into five equally proportioned groups, where quintile 1 (Q1) signifies approximately the poorest 20% of households, and quintile 5 (Q5) represents the richest 20%.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted for each outcome, spanning the years 2009, 2014 and 2019. The prevalence of each outcome was systematically examined, with disaggregation by all selected stratifiers. To delve deeper into the analysis of inequalities in the prevalence of women's attitudes about IPV against women, two complex measures of inequalities were utilized. The slope index of inequality (SII) and the concentration index of inequality (CIX), both widely applied in epidemiology and public health to quantify the extent of inequality across different socioeconomic groups. These measures provide a nuanced understanding of how the prevalence of women's attitudes about IPV against women varied across the socioeconomic strata from 2009 to 2019.23 SII is a measure of absolute inequality, while CIX measures the relative inequality. Regression analysis was used to compute the slope index of inequality by considering the entire distribution of the result over the five wealth quintiles.23 A SII of zero indicates the absence of inequality between subgroups. Positive values indicate that the wealthiest women are more likely to justify wife's beating by the husband, suggesting a higher prevalence of such attitudes in wealthier segments; while negative values suggest the opposite.23

The calculation of CIX is akin to the Gini coefficient, which assesses the concentration of income among the wealthiest individuals.23 The CIX ranges between −1 and +1, with zero indicating no inequality. In the context of this study, positive values suggest that the prevalence of women's attitudes about IPV by a husband is more concentrated among the richest individuals. Conversely, negative values suggest the opposite.23

We used multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression analysis to explore factors associated with women's attitudes justifying IPV against women for any of the five reasons, with each time point per region serving as the unit of analysis. We arrived at 30 time points (resulting from 10 regions x 3 surveys) as our units of analysis. These individual units were then organized into higher-level units (regions) within the multilevel model to address any correlations within regions. The model included fixed effects for time (years), allowing us to estimate its impact on women's attitudes about IPV, and random effects for regions, which accounted for variability between these regions.

We conducted the modelling at the regional level due to the theoretical benefits of individualized modelling, particularly driven by specific characteristics like education. We aimed to use a concise model with substantial explanatory and predictive capability, ensuring it contained the appropriate number of factors to explain the results effectively. We used a conceptual framework, organized in levels (2 levels), to guide our analysis and elucidate the numerous factors that may be associated with women's attitudes about IPV against women. At each level of the conceptual framework, beginning with level 1, we initially conducted a crude mixed-effects logistic regression analysis, assessing the relationship between outcomes and one factor at a time. Variables with a significance level of P ≤ 0.05 were chosen for integration into the adjusted multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression. Subsequently, we employed a backward stepwise selection method to eliminate variables with P-values greater than 0.05, beginning with those exhibiting the highest P-values. This systematic approach enabled us to derive a conclusive model for each level, incorporating variables slated for inclusion in the subsequent level. Throughout the process, the model consistently incorporated the variable “year” to factor in the influence of time. Location of residence (Coastal vs. Interior) was excluded from the model to allow for comparison with studies from other settings. Our analyses only used available data for each variable. However, none of the variables analyzed had missing data exceeding 0.3%. We report our study in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (STROBE) for observational studies. All analyzes were performed using Excel (version 2016) and Stata (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for each survey was granted by the Guyanese Ministry of Health-Institutional Review Board (MOH-IRB). Verbal informed consent was obtained for each participant in the surveys prior to data collection. All respondents were made aware of the voluntary nature of their participation, as well as the confidentiality and anonymity of their information. They were also informed of their right to refuse to answer any or all questions and to stop the interview at any time.

Role of the funding source

The funder of this study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

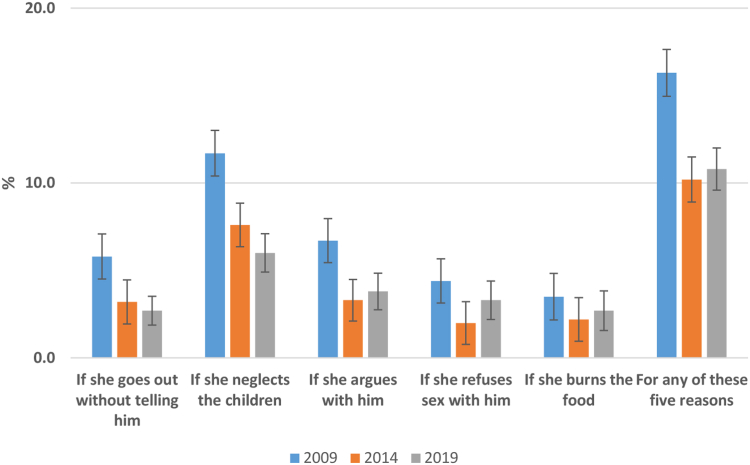

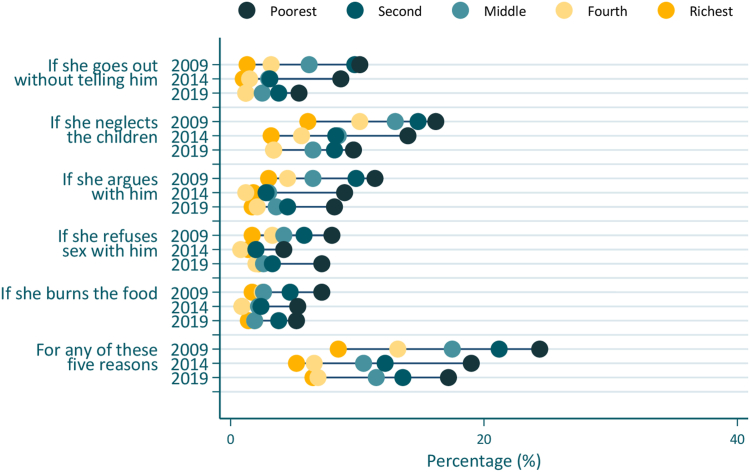

We report findings for 15,959 women in the reproductive age group (15–49 years) with data available on their attitudes about IPV against women in Guyana, including 4996 women from DHS 2009, 5076 from MICS 2014, and 5887 from MICS 2019. The prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women for at least one of the five reasons ranged from 16.4% (95% CI: 15.1–17.8) in 2009, 10.2% (95% CI: 9.1–11.4) in 2014, to 10.8% (95% CI: 9.7–12.0) in 2019 (Fig. 2). When assessing each reason separately, all the indicators showed a statistically significant decrease from 2009 to 2014. Women's attitudes justifying IPV against women if “she goes out without telling him” and if “she neglects the children” showed a slight decrease from 2014 to 2019, but with their confidence intervals overlapping. Similarly, women's attitudes justifying IPV against women if “she argues with him,” if “she refuses sex with him,” and if “she burns the food” seemed to increase during the same period, but with overlapping confidence intervals. Neglecting the children appeared to be the most prevalent among the justifying reasons, ranging from 11.7% (526/4996) to 6.0% (354/5887) between 2009 and 2019.

Fig. 2.

National prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in Guyana (2009–2019).

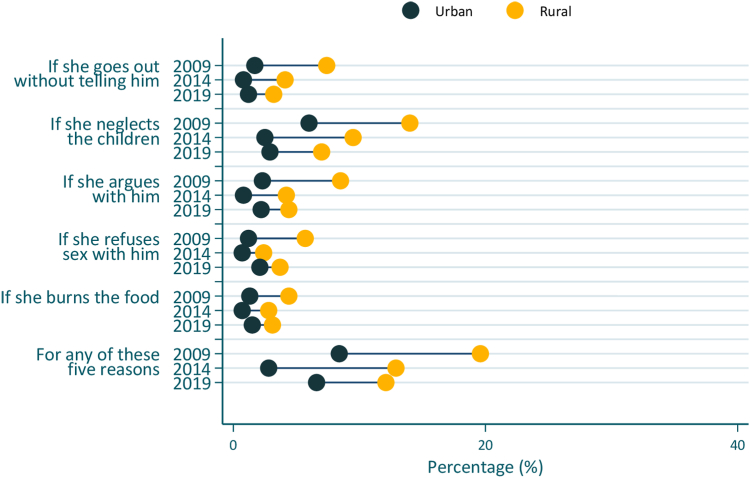

Women's attitudes justifying IPV against women was more common in rural areas. However, the gap between urban and rural areas seemed to decrease over time for each of the assessed reasons. The justification of IPV against women for any of the five reasons decreased from 8.4% (124/1475) to 6.6% (93/1424) in urban areas between 2009 and 2019, while in rural areas, it decreased from 19.6% (690/3521) to 12.1% (540/4463) during the same period (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in Guyana (2009–2019), by urban-rural place of residence.

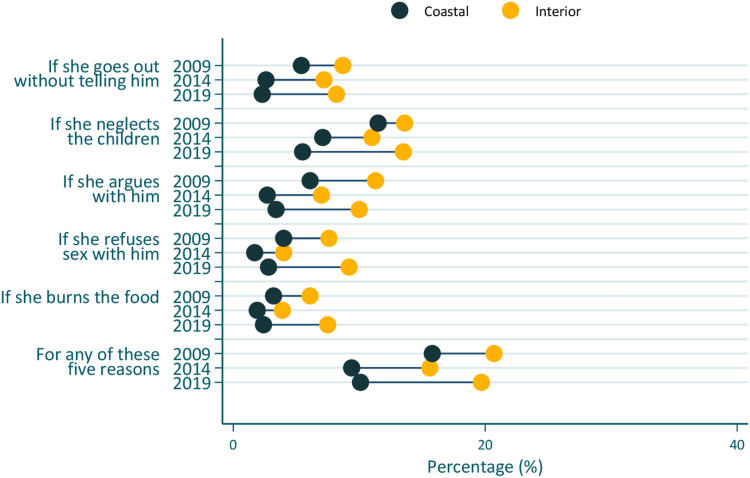

Similarly, women's attitudes justifying IPV against women seemed to be more common in the interior locations, with an increasing gap between coastal and interior locations over time (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables S1–S3). Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Tables S1–S3 illustrate geographic variations in the prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women. Significant inequalities were observed between regions, with regions 4 and 10 having the lowest prevalence and region 1 exhibiting the highest prevalence in both 2009 and 2019 (P < 0.001). Region 1 consistently lagged behind all other subgroups for each of the outcomes, indicating a top inequality pattern.

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in Guyana (2009–2019), by coastal-interior place of residence.

The disaggregation of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women by respondent's age did not show a clear pattern over time. No statistically significant differences were observed for such prevalence for any of the five reasons in 2009 and 2014. However, in 2019, this attitudes justification seemed to be more common among women aged 45–49 years (P = 0.003), and mostly driven by: “if she argues with him”, “if she refuses sex with him”, and “if she burns the food” (Supplementary Tables S1–S3). The women's attitudes justifying IPV against women seemed to be more common among women where the household's head is a male from 2009 to 2014 (P < 0.05). In 2019, no statistically significant differences were observed (Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

Women who were currently married or in a union were more likely to justify IPV against women for several reasons across different years. In 2009, 2014, and 2019, they justified it if the woman went out without telling her partner. Justifications were also evident in 2009 and 2014 if she neglected the children, and in 2009 if she argued with him or refused sex. In 2019, they justified it if she burned the food. For any of the five reasons mentioned, justification was present in 2009, 2014, and 2019 (P < 0.05), Supplementary Tables S1–S3. Additionally, these attitudes were more common among women with no education or only primary-level education across all outcomes (P < 0.001), Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

Fig. 5 illustrates the breakdown of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women by wealth quintile. A statistically significant decrease was observed in the prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women for any of the five reasons among women from the poorest household quintiles. The prevalence dropped from 24.4% (190/779) in 2009 to 17.2% (171/993) in 2019. In contrast, decline for women from the richest household was lower, from 8.5% (98/1151) to 6.5% (79/1213) during the same period. Although the wealth gap appeared to narrow over time, in 2019, women's attitudes justifying IPV against women were more than three times higher among women from the poorest households compared to those from the richest. This trend was consistent for each of the five reasons (Fig. 5, Supplementary Tables S1–S3). Regarding access to media, a greater prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women was found among women who read newspapers/magazines less than once a week or not at all, and who watch television less than once a week or not at all (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

Fig. 5.

Prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in Guyana (2009–2019), by wealth quintile.

Table 1 summarizes progress in both absolute and relative inequalities in women's attitudes justifying IPV against women. The SII for the combination of the five reasons decreased from minus 20.02 in 2009 to minus 14.28 in 2019. However, the CIX remained constant during the same period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Trends in slope index and concentration index of inequalities in women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in Guyana (2009–2019).

| Indicators | Slope index of inequality (SE) |

Concentration index of inequality (SE) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2014 | 2019 | 2009 | 2014 | 2019 | |

| If she goes out without telling him | −12.96 (2.85) | −9.51 (1.56) | −5.90 (0.41) | −0.32 (0.10) | −0.39 (0.08) | −0.31 (0.05) |

| If she neglects the children | −12.52 (2.28) | −12.53 (1.33) | −8.95 (0.92) | −0.16 (0.06) | −0.25 (0.07) | −0.22 (0.04) |

| If she argues with him | −11.49 (1.18) | −8.77 (2.61) | −8.20 (0.80) | −0.25 (0.05) | −0.36 (0.07) | −0.31 (0.06) |

| If she refuses sex with him | −7.89 (0.55) | −3.57 (1.05) | −5.92 (1.74) | −0.26 (0.07) | −0.26 (0.07) | −0.26 (0.06) |

| If she burns the food | −6.96 (0.51) | −5.65 (0.77) | −4.99 (0.31) | −0.28 (0.04) | −0.35 (0.07) | −0.27 (0.03) |

| For any of these five reasons | −20.02 (2.11) | −17.03 (1.16) | −14.28 (0.86) | −0.19 (0.05) | −0.25 (0.05) | −0.20 (0.04) |

SE, Standard error. The results in the table are expressed in percentage points. Each estimate representing the prevalence in percentage point (SII) or the concentration (CIX) for each indicator in the particular year at national level.

In Table 2, we present results that are adjusted for time alone as well as results adjusted for both time and confounder variables. Except for woman's age, all the determinants showed a statistically significant association with women's attitudes justifying IPV for any of the five reasons (P < 0.001). Regression analyses adjusted for both time and confounding factors, following the conceptual framework hierarchy, revealed that women living in rural areas (AOR: 2.22; 95% CI: 1.90–2.66), where sex of household head was male (AOR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.11–1.40), currently married/in union (AOR: 1.17; 95% CI: 1.02–1.33), and with primary level of education (AOR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.39–1.82) were more likely to justify IPV. Likewise, women from the poorest household (AOR: 2.30; 95% CI: 1.90–2.80), and who did not read newspapers/magazines in the past month (AOR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.39–1.95) were more likely to justify wife's beating by a husband. Overall, women's attitudes about IPV against women seemed to decrease by 6.0% from 2009 to 2019 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multilevel mixed logistic regression for the association between the determinants and women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in Guyana.

| Determinants | Time-AOR (95% CI) | P-value | Time and confounder-AOR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area of residence | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Urban | ref | ref | ||

| Rural | 2.46 (2.11–2.88) | 2.22 (1.90–2.66) | ||

| Woman age | 0.12 | |||

| 15–19 | ref | – | – | |

| 20–24 | 0.82 (0.71–0.99) | |||

| 25–29 | 0.91 (0.77–1.08) | |||

| 30–34 | 0.87 (0.72–1.04) | |||

| 35–39 | 0.96 (0.81–1.15) | |||

| 40–44 | 0.88 (0.73–1.05) | |||

| 45–49 | 1.18 (0.99–1.40) | |||

| Sex of household head | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Male | 1.36 (1.21–1.52) | 1.25 (1.11–1.40) | ||

| Female | ref | ref | ||

| Marital/Union status | <0.001 | 0.046 | ||

| Currently married/in union | 1.34 (1.19–1.51) | 1.17 (1.02–1.33) | ||

| Formerly married/in union | 1.12 (0.90–1.39) | 1.09 (0.86–1.38) | ||

| Never married/in union | ref | ref | ||

| Woman education | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| None | 1.60 (1.07–2.41) | 1.13 (0.73–1.73) | ||

| Primary | 2.04 (1.79–2.31) | 1.59 (1.39–1.82) | ||

| Secondary+ | ref | ref | ||

| Wealth index quintile | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Poorest | 2.90 (2.42–3.49) | 2.30 (1.90–2.80) | ||

| Second | 2.12 (2.08–2.91) | 2.12 (1.78–2.53) | ||

| Middle | 2.01 (1.69–2.38) | 1.71 (1.43–2.04) | ||

| Fourth | 1.32 (1.10–1.75) | 1.21 (1.001–1.46) | ||

| Richest | ref | ref | ||

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Almost every day | ref | ref | ||

| At least once a week | 1.42 (1.23–1.63) | 1.27 (1.09–1.47) | ||

| Less than once a week | 1.66 (1.40–1.97) | 1.38 (1.16–1.65) | ||

| Not at all | 2.23 (1.91–2.60) | 1.65 (1.39–1.95) | ||

| Frequency of watching television | <0.001 | 0.82 | ||

| Almost every day | ref | ref | ||

| At least once a week | 1.10 (0.95–1.26) | 1.02 (0.88–1.19) | ||

| Less than once a week | 1.24 (1.004–1.53) | 1.11 (0.89–1.39) | ||

| Not at all | 1.47 (1.27–1.70) | 0.99 (0.84–1.18) | ||

| Time (Year) | 0.95 (0.94–0.96) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) | <0.001 |

The units of analysis are 30 (10 regions × 3 years). Variable from level 1 includes area of residence, woman age, sex of household head, marital status/union, woman education and wealth index quintile. Level 2 includes frequency of reading newspaper or magazine, and frequency of watching television. Each variable was adjusted for all other variables within the same level and above.

Discussion

Our study assessed trends in women's attitudes about justifying IPV against women in Guyana and the factors associated with these attitudes. The results presented here analyzing three national surveys indicate a reduction in the prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in Guyana from 2009 to 2019 with more progress being observed from 2009 to 2014. Substantial socioeconomic and geographic disparities in the justification of IPV were observed, but there appears to be a trend of narrowing gaps among subgroups over time. The latter is a good signal, which suggests that efforts aimed at improving gender equality in Guyana have been effective to some extent, even though disparities between subgroups continue to persist overtime. In our multilevel regression, the key factors associated with women's attitudes towards justifying IPV against women were area of residence, sex of the household head, marital status, and women's level of education, wealth index quintile, and the frequency of reading newspaper or magazine. These findings are of utmost importance not only by showing the subgroups that are more likely to justify wife's beating by a husband as acceptable but can also be used to inform targeted interventions and policies aimed at promoting gender equality, combating IPV against women, and fostering attitudes of respect and equality within households.

The findings from this study are consistent with findings from other studies in other low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Sardinha et al., showed a regional prevalence of attitudes justifying IPV in the Latin America and the Caribbean countries of 11.9% in 2018, which is comparable to that observed in Guyana.2 However, Belize (5.2%) and the Dominican Republic (2.4%), two Caribbean countries with income economy comparable to Guyana, showed a lower prevalence of women justifying IPV by a husband for any of the five reasons as acceptable.2,26 In other Caribbean countries like Honduras (12.4%), and Haiti (16.7%), this prevalence was notably higher than observed in Guyana.2 Tran et al., in 2016, using similar data from 39 LMICs showed that women from rural areas of residence, who belonged to the lowest household wealth quintile, and with low level of education were more likely to justify IPV by a husband as acceptable.27 Another study by Hayes and Boyd using DHS data from 41developing countries showed that women living in urban areas, with higher levels of education, who belonged to the richest household wealth quintile were less likely to support IPV.28 A more recent analysis by Alam et al., in Bangladesh in 2022, showed area of residence, women's level of education, women's marital status, wealth quintile index, and exposure to mass media as key factors associated with women's attitudes justifying IPV.29 The prevalence of any of the five reasons observed in that study was more than twice the observed in Guyana in 2019.29 The sex of the household head is another important factor associated with women's attitudes about IPV. This is consistent with findings from literature. Gunarathne et al., in a study with 20 LMICs showed a 5% reduction in women's attitudes justifying IPV against women in households where the heads are females.30 Similar findings were reported by Paintsil et al., in a study with 30 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.31

The literature lacks evidence on trends of women's attitudes about IPV in the Americas. However, Patil and Khanna showed that, in a study in Nepal, the prevalence of women justifying IPV remained unchanged from 2003 (29.1%) to 2016 (29.1%).32 Bott et al. (2019) using a different approach to assess the prevalence of women's reported experiences of IPV across the Americas, revealed a notable decline over time in Colombia, Guatemala, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Mexico. However, in the Dominican Republic, this prevalence seemed to increase from 2002 to 2013.8

The positive change observed here for Guyana can potentially be linked to the concerted efforts and strategies implemented by both the government and local institutions over the past decades to address domestic violence against women, including the Domestic Violence Act of 1996,12 the Evidence Act of 2008,13 the Protection of Children Act of 2009,14 the Sexual Offense Act of 2010,15 the Women and Gender Equality Commission,33 the Equality for Women (Article 149F, year)16 the office of Gender Affairs Bureau34 within the Ministry of Human Services and Social Security (MHSSS) in 2016, and the National Gender Equality and Social Inclusion for Guyana (NGESIP) in 2018.17 A 24-h national Domestic Violence hotline was also implemented in 2010 to report any case of IPV.35 Besides, several institutions were created to support women and reduce IPV against women in the country, including, but not limited to the Red Thread Women's Development Program (1986),36 the Guyana Women's Leadership Institute (1990),37 the Guyana Legal Aid Clinic (1994),38 and Help and Shelter (1995)39; These institutions, in conjunction with the Guyanese governments work to provide free and/or legal assistance to women grappling with the challenges of IPV against women might have contributed to the reductions observed in the time trend analysis. The several international conventions signed and ratified by Guyana in the past decade, particularly the CEDAW, played a key role in launching several institutions in the country. These conventions provided a normative framework for implementing action plans for gender equality, enacting legislative measures to eliminate discrimination against women, and encouraging the active participation of civil society organizations in promoting and protecting women's rights, among other efforts.35,38,40

A recent study by Ellsberg et al. highlighted how policy reforms particularly driven by feminist advocacy have impacted women's attitudes towards violence, leading to a decrease in the prevalence of IPV in Nicaragua.41 Weldon and Htun also advocated for the role of policy reforms driven by feminist mobilization to combat IPV.42

In addition to the direct measures undertaken by Guyana to combat IPV, two other factors must be considered in the recent history of the country that might indirectly affect IPV prevalence. First, the acceleration in economic activity in Guyana particularly due to gas exploration.43 This shift in economic landscape, can lead to increased employment opportunities and enhanced social services such as better access to education and public awareness campaigns, which in turn, may change the traditional roles and power dynamics within households. Secondly, in the last decades, the governments have implemented several policy reforms to reduce poverty, and provide better access to education, health and social services.44, 45, 46 Previous and the current study have shown associations between IPV acceptance poverty and education; thus the recent economic growth paired with direct investments in reducing poverty and improving education might have also contributed to the results observed in our analysis.

Our study has strengths and limitations. We utilized data from DHS and MICS in Guyana, which were designed to generate nationally and regionally representative estimates. Both DHS and MICS are global household surveys conducted in 90 (DHS) and 120 LMICs (MICS) respectively since 1984 (DHS) and 1990 (MICS). DHS and MICS data have been used globally to inform strategies towards achieving the global Sustainable Developments Goals (SDGs) from 2016 to 2023. To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Guyana assessing trends in women's attitudes about IPV against women, with an equity lens. We were also able to demonstrate key factors associated with women's attitudes justifying IPV, as well as its change over time. However, the study has limitations, particularly regarding uncertainties surrounding the reliability and validity of the questions used by DHS and MICS to measure women's attitudes toward domestic violence.47,48 Nevertheless, these questions have been used for decades to assess women's attitudes about IPV against women in several other countries.26,29,49 It is essential to acknowledge that the study focused exclusively on women's attitudes about IPV against women, here understood as physical violence only, aligning with DHS and MICS data collection methods. These surveys collect data on women's attitudes about IPV while omitting other forms of IPV. The report on women's attitudes about IPV against women does not necessarily mean that the women responding to the questionnaire has experienced IPV. Importantly, we were unable to assess women's attitudes according to their ethnicities, as this information was unavailable. This must be regarded as an important limitation as ethnicity in Guyana, similarly to other South American countries, is intersectionally related to wealth and a critical component of the socioeconomic analysis, with different impacts in the many regions of the country. Future work should expand data collection to allow for a stratified analysis of race/ethnicity and IPV perception, acceptance, and attitudes. Finally, the literature lacks evidence on trends of women's attitudes about IPV against women over the years in the Americas, which could be used to compare the findings from this study.

Conclusion and recommendations

Guyana has improved the prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV against women, and reduced inequalities among various subgroups over the last decade. Concurrently, the implementation of policy reforms, and commitment of local institutions can be considered key contributors for such improvement. Nevertheless, in 2019, the level of justification for IPV against women remains high, especially in rural areas, among women from the poorest households, and those with lower levels of education, highlighting significant disparities. Targeted policy interventions, including the effective use of media, the promotion of community-based approaches, and the implementation of school programs teaching children and adolescents about consent, respect, and healthy relationships, are necessary to reduce justifications for IPV against women in Guyana. These interventions should also encompass educational campaigns focusing on geographic and socioeconomic disparities. This comprehensive approach would help both men and women oppose gender-based violence, protecting women's rights and fostering a more equitable and safe society. Besides, while the prevalence of women's attitudes justifying IPV seems to be decreasing, other beliefs such as attitudes towards gender roles, body shaming, political ideologies, among others may be rising. Future studies are necessary to understand the evolving beliefs and attitudes that might affect people's safety and health and threat any universal human right in Guyana.

Contributors

GJ played a role in designing the study, acquiring data, conducting analyses, interpreting results, and drafting the manuscript. CB and CM contributed to the study's design, result interpretation, and provided final reviews of the manuscript. SR and MR contributed to interpreting the results, drafting the manuscript, and provided final review of the manuscript. GJ, CB, and CM had full access to the data used in the study and accepted responsibility to submit the final manuscript for publication. GJ was responsible for submission of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The data used in this research is publicly available and can be accessed via the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) at https://mics.unicef.org/surveys and the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) at https://dhsprogram.com/Data/.

Editor's note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the Guyana Research in Injury and Trauma Training (GRITT) project to facilitate capacity building in research training and methods by stimulating interest and promoting knowledge in suicide, trauma, and injury prevention in Guyana. We thank Ms. Joanne Nelson for her contribution to designing the MAP that represents the administrative regions of Guyana.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2024.100920.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.United Nations . UN; New York: 1993. Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sardinha L., Catalán H.E.N. Attitudes towards domestic violence in 49 low-and middle-income countries: a gendered analysis of prevalence and country-level correlates. PLoS One. 2018;13(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization(WHO) 2021. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations (UN) Sustainable development goals. 2015. https://www.un.org/ Available at:

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; Geneva: 2012. Understanding and addressing violence against women: intimate partner violence. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO) 2005. WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women : initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah S.H., Rajani K., Kataria L., Trivedi A., Patel S., Mehta K. Perception and prevalence of domestic violence in the study population. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21(2):137. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.119624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bott S., Guedes A., Ruiz-Celis A.P., Mendoza J.A. Intimate partner violence in the Americas: a systematic review and reanalysis of national prevalence estimates. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2019;43:e26. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2019.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kandiyoti D. Bargaining with patriarchy. Gend Soc. 1988;2(3):274–290. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO) 2013. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health impacts of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Contreras-Urbina M., Bourassa A., Myers R., Ovince J., Rodney R., Bobbili S. Government of Guyana; 2019. Guyana women's health and life experiences survey report. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Government of Guyana Domestic violence ACT. 2012. https://mhsss.gov.gy/ Available at:

- 13.Parliament of the co-operative republic of Guyana. Evidence Act (Amendment); 2008. https://parliament.gov.gy/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parliament of the co-operative republic of Guyana. Protection of Children Act; 2009. https://parliament.gov.gy/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Government of Guyana Sexual offences act. 2012. https://dpp.gy/ Available at:

- 16.Parliament of the co-operative republic of Guyana. Equality for Women (Article 149F) https://parliament.gov.gy/ Available at:

- 17.Department of Public Information (DPI) National gender equality and social inclusion policy for Guyana (NGESIP) https://dpi.gov.gy/ Available at:

- 18.United Nations Human Right Office of the high commissioner. https://indicators.ohchr.org/ Available at:

- 19.Ministry of Health (MOH), Bureau of Statistics (BOS), and ICF Macro . MOH, BOS, and ICF Macro; Georgetown, Guyana: 2010. Guyana demographic and health survey 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Public Health and UNICEF . Georgetown, Guyana: Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Public Health and UNICEF; 2015. Guyana Multiple indicator cluster survey 2014, final report. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MeasureDHS . ICF International; Calverton: 2012. DemographicandHealthSurveySamplingandHousehold listing manual. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barros A.J., Victora C.G. Measuring coverage in MNCH: determining and interpreting inequalities in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health interventions. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization (WHO) 2013. Handbook on health inequality monitoring: with a special focus on low-and middle-income countries. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 24.https://statisticsguyana.gov.gy/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Final_2012_Census_Compendium2.pdf

- 25.Rutstein S.O., Johnson K., Measure O. The DHS wealth index: ORC Macro MEASURE DHS. Measure DHS. 2004;6:1–77. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statistical Institute of Belize and UNICEF Belize . Belmopan, Belize: Statistical Institute of Belize and UNICEF Belize; 2017. Belize Multiple indicator cluster survey, 2015-2016, final report. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tran T.D., Nguyen H., Fisher J. Attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women among women and men in 39 low-and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2016;11(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes B.E., Boyd K.A. Influence of individual-and national-level factors on attitudes toward intimate partner violence. Socio Perspect. 2017;60(4):685–701. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alam M.I., Sultana N. Attitudes of women toward domestic violence: what matters the most? Violence Gend. 2022;9(2):87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunarathne L., Apputhurai P., Nedeljkovic M., Bhowmik J. Factors associated with married women's attitude toward intimate partner violence: a study on 20 low-and middle-income countries. Health Care Women Int. 2024:1–21. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2024.2319214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paintsil J.A., Adde K.S., Ameyaw E.K., Dickson K.S., Yaya S. Gender differences in the acceptance of wife-beating: evidence from 30 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):451. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02611-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patil V.P., Khanna S. Trends in attitudinal acceptance of wife-beating, domestic violence, and help-seeking among married women in Nepal. J Biosoc Sci. 2023;55(3):479–494. doi: 10.1017/S0021932022000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parliament of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana Women and gender equality commission. https://parliament.gov.gy/ Available at:

- 34.Ministry of Human Services and Social Security Gender Affairs Bureau. https://mhsss.gov.gy/ Available at:

- 35.Guyana Chronicle Domestic abuse emergency hotline launched. 2010. https://guyanachronicle.com/ Available at:

- 36.Red Thread Red Thread women's development programme. https://redthreadguyana.org/ Available at:

- 37.Guyana Chronicle Renewed and expanded women's institute will provide unconventional training. 2021. https://guyanachronicle.com/ Available at:

- 38.Guyana legal Aid clinic. https://www.legalaid.org.gy/ Available at:

- 39.Help & shelter. https://www.hands.org.gy/ Available at:

- 40.Ministry of Human Services and Social Security (MHSSS) Probation and social service department. https://mhsss.gov.gy/ Available at:

- 41.Ellsberg M., Quintanilla M., Ugarte W.J. Pathways to change: three decades of feminist research and activism to end violence against women in Nicaragua. Global Public Health. 2022;17(11):3142–3159. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2022.2038652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weldon S.L., Htun M. Feminist mobilisation and progressive policy change: why governments take action to combat violence against women. Gend Dev. 2013;21(2):231–247. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDonald L., Üngör M. New oil discoveries in Guyana since 2015: resource curse or resource blessing. Resour Policy. 2021;74 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Government of Guyana National development strategy (2001 - 2010): a policy framework . Edicating poverty and unifying Guyana: a civil society document. https://www.parliament.gov.gy/ Available at:

- 45.Bedi A.S., Jong N. Guyana's poverty reduction strategy and social expenditure. Eur J Dev Res. 2011;23:229–248. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lowe J. 2001. Guyana Education Access Project (GEAP): development plan for an appropriate cadre of INSET secondary trainers. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lawoko S. Factors associated with attitudes toward intimate partner violence: a study of women in Zambia. Violence Vict. 2006;21(5):645–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawoko S. Predictors of attitudes toward intimate partner violence: a comparative study of men in Zambia and Kenya. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(8):1056–1074. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kebede S.A., Weldesenbet A.B., Tusa B.S. Magnitude and determinants of intimate partner violence against women in East Africa: multilevel analysis of recent demographic and health survey. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01656-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.