Abstract

Background and purpose

To determine the risk factors for puncture-related complications after the distal transradial approach (dTRA) for cerebrovascular angiography and neuroendovascular intervention and to explore the incidence and potential mechanisms of procedural failure and puncture-related complications.

Materials and methods

From February to November 2023, 62 patients underwent dTRA in our department. Demographic, clinical, and procedural data were collected retrospectively. Postoperative puncture-related complications were defined as a syndrome of major hematoma, minor hematoma, arterial spasm/occlusion, arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurysm, and neuropathy. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were performed to identify significant factors contributing to puncture-related complications.

Results

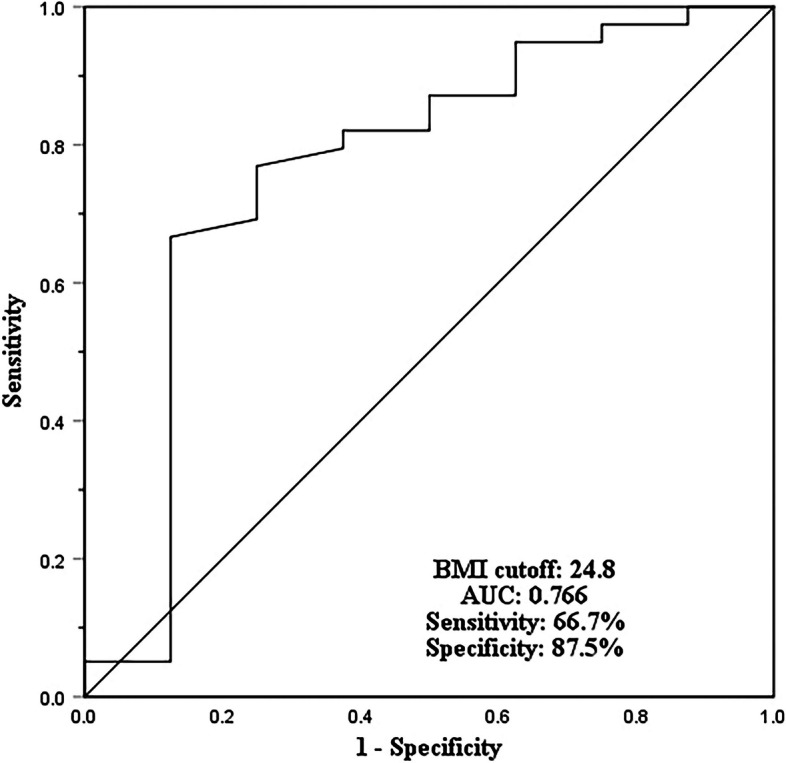

Forty-five diagnostic cerebral angiograms and 17 neurointerventions were performed or attempted with dTRA in 62 patients. Procedural success was achieved via dTRA in 47 (75.8%) patients, whereas 15 (24.2%) required conversion to other approaches. Reasons for failure included puncture failure (n = 8), inability to cannulate due to arterial spasm (n = 6), and inadequate catheter support of the left vertebral artery (n = 1). 17.0% (8/47) of patients had postoperative puncture-related complications. Minor hematoma occurred in 8.5% (4/47) of patients, arterial spasm/occlusion in 6.3% (3/47), and neuropathy in 2.1% (1/47). No major complications were observed. On stepwise multivariable regression analysis, BMI (OR = 0.70, 95%CI 0.513 to 0.958; p = 0.026) was an independent risk factor for puncture-related complications, with a cut-off of 24.8 kg/m2 (sensitivity 66.7% and specificity 87.5%).

Conclusion

Our cohort is the first study of risk factors for puncture-related complications after neurointerventional interventions with dTRA. This study has shown that a low BMI (< 24.8 kg/m2) is independently associated with the development of puncture-related complications.

Keywords: Distal transradial approach, Risk factors, Complications, Diagnostic cerebral angiography

Background

The transradial approach (TRA) for cerebral angiography and neuroendovascular treatment has gained popularity. Due to its many advantages over the transfemoral approach, including lower risk of bleeding complications, shorter recovery time, and higher patient satisfaction [1]. Additionally, TRA provides a more direct anatomic pathway to access the ipsilateral vertebral artery and simplifies catheterization in patients with complex aortic arch anatomy, such as bovine and type III arches.

However, this approach is not without shortcomings. Radial artery occlusion is a rare complication of TRA, occurring in approximately 4% of patients [2]. Although always asymptomatic, it still has the potential to cause severe hand ischemic events in patients with inadequate ulnar collateral circulation [2]. Similarly, occlusion of the proximal radial artery located in the forearm may limit future TRA and use of the vessel as a conduit for bypass grafting or arteriovenous fistula formation.

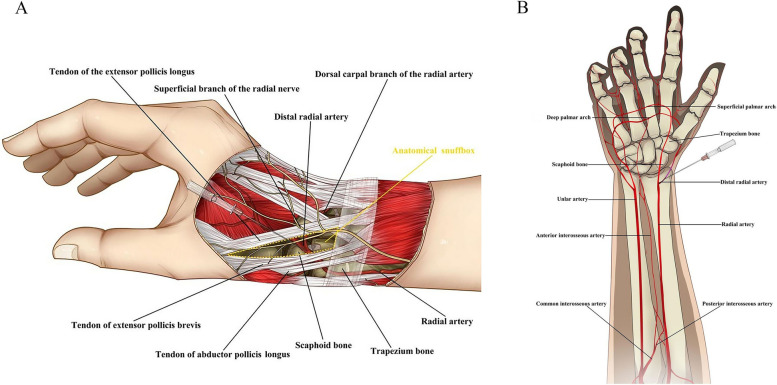

The distal radial artery (dRA) is accessed in the anatomical snuffbox. The anatomical snuffbox is a triangular space surrounded by the tendons of the extensor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, and abductor pollicis longus muscles, and its floor is formed by the scaphoid and trapezium bone(Fig. 1A). The dRA extends to form the superficial and deep palmar arches. The blood compensation of two branches can guarantee the hand blood supply even arterial occlusion, reducing the risk of hand ischemia(Fig. 1B). Other potential benefits include a lower rate of radial artery occlusion, improved patients and operators comfort, and shorter hemostasis times [3]. The safety and feasibility of dTRA has been preliminarily recognized [4–17]. However, few studies have focused on the factors influencing procedural success and puncture-related complications in dTRA. In the present study, we assessed the risk factors associated with puncture-related complications. We also conducted a systematic review to explore the incidence and potential mechanisms of procedural failure and puncture-related complications.

Fig. 1.

Distal radial artery puncture site (anatomical snuffbox area) and relevant surrounding anatomic structures. A Vascular anatomy of the forearm and hand. B

Methods

Patient population

From February to November 2023, we retrospectively analyzed our institutional database of all diagnostic or neurointerventional procedure cases performed with dTRA. All patients underwent a forearm ultrasound of the forearm arteries to assess radial artery diameter and anatomic condition. Exclusion criterion: high-bifurcation radial origins, full radial loops, and radial tortuosity. The study was approved by our institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data collection

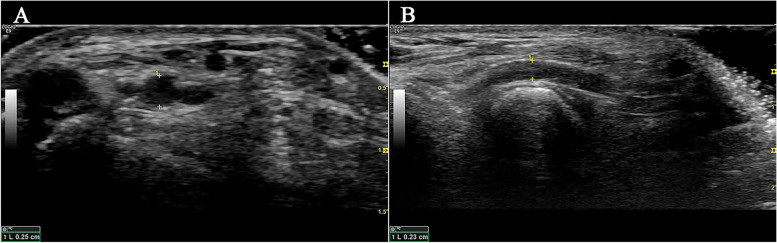

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and procedural variables were collected through a review of the electronic medical records. Patient demographic data comprised of age, sex, and BMI. Clinical data comprised antiplatelet therapy (classified as dual antiplatelet therapy, single antiplatelet use, or neither), medical history information (history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia), and diagnosis. Arterial diameters were measured preoperatively by ultrasound (Philips iE33 ultrasound machine; Philips L11-3 ultrasound Probe), including the distal radial artery in the anatomical snuffbox and the radial artery proximal 2–3 cm of the styloid process of radius (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 2.

Preoperative assessments of forearm RA and dRA based on ultrasonography. A Diameter of the RA in the horizontal section. B Diameter of the dRA in the longitudinal section. RA, radial artery; dRA, distal radial artery

Procedural variables included puncture side (dichotomized into right side vs left side), procedural purpose (classified as diagnostic angiography and interventional therapy), puncture time, access time, fluoroscopic time, operation duration, compression hemostatic time, discharge time, and radiation exposure. Indications for diagnostic angiography during evaluation or follow-up include aneurysm, internal carotid artery stenosis, vertebral basilar artery stenosis, and others. According to the specifications proposed by the First Korea-European Transradial Intervention Consensus in 2021, we defined the puncture time as the time between the puncture needle contacting the skin and the guidewire passing the puncture needle into the artery [3]. The access time was defined as the time between the anesthesia needle touching the skin and the proper placement of the introducer sheath.

Distal transradial approach technique

All procedures were performed by the same neurointerventionalist. Before involvement in this study, this operator had independently completed at least 200 TRA and 50 dTRA procedures—experience consistent with having overcome the basic TRA and dTRA learning curve as described by Zussman [18] and Hoffman [10]. The Allen test was not performed because all patients underwent preoperative forearm ultrasound. The dTRA was preferred, and if the procedure failed, it was sequentially converted to the TRA and transfemoral approach.

The patient lay supine on the examination table, the right upper arm was positioned naturally next to a side-board, and the wrist was elevated to the level of the body using padding. The hand was kept slightly flexed and deviated toward the ulna to straighten the radial artery and bring it to a more superficial plane. Disinfection was performed from the palms and proximal dorsum of the hands to the distal forearm (Fig. 3A). The puncture point was chosen where the distal radial artery pulse was strongest at the anatomic snuffbox. All interventional procedures were performed under general anesthesia, whereas diagnostic cerebral angiography was performed under local anesthesia. After infiltrating the soft tissues around the puncture site using 1–2 ml of lidocaine, the distal radial artery was punctured with the single-wall technique (Fig. 3B). Regardless of the procedure performed, a 6F hydrophilic radial sheath (RADIFOCUS Introducer II, Terumo) was introduced over the wire (Fig. 3C, D). Next, a mixture of 200 mcg nitroglycerin, 2.5 mg verapamil, and 2,000 units of heparin was infused into the sheath immediately following hemodilution. The remainder of the case proceeds in an identical fashion to standard TRA.

Fig. 3.

Distal transradial approach technique. A The patient’s right hand is kept in a neutral position on the side-board, and the wrist is elevated using padding with the fingers curled. The entire forearm is sterilized (including the radial and ulnar artery puncture points). B An 18G needle was used to puncture the dRA in a single wall at 30° to 45°, and the blood spray at the tail of the needle was observed. (C, D) After ensuring backflow, a 018″ guidewire and a 6F radial sheath are gently inserted. (E, F) Place a small piece of gauze over the puncture site and roll it tightly with an elastic

The puncture site can be easily closed by placing a small piece of gauze over the puncture site and then rolling it tightly with an elastic bandage (excluding the thumb) (Fig. 3E, F).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was puncture-related complications. This was determined by a consensus of experienced neurointerventionalists and ultrasonographers at 1d postoperatively and defined as a composite of major hematoma, minor hematoma, arterial spasm/occlusion, arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurysm, and neuropathy. We graded local hematoma based on the EASY (Early Discharge After Transradial Stenting of Coronary Arteries Study) hematoma scale, which defined EASY grades I-II as minor hematoma and EASY grades III-IV as severe hematoma [19]. Arterial spasm/occlusion may occur in the forearm radial artery, the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox, or both. There are no established diagnostic criteria for radial artery spasm, and we defined it as a decrease in radial artery diameter and patency on Doppler studies, with or without forearm pain. Radial artery occlusion was defined as the absence of radial pulsations on palpation and antegrade flow signal on Doppler studies. The secondary outcome was procedure success (successful completion of the procedure from the intended access site), and the incidence and causes of procedure failure were recorded. Composite secondary outcomes included dRA puncture success and dRA cannulation success. We defined puncture success as the smooth delivery of the guidewire through the punctured artery and cannulation success as the proper placement of the sheath through the punctured artery.

Statistical analysis

All the analyses and calculations were conducted using SPSS Statistic 22.0 (IBM-Armonk, New York, USA). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s test. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test based on the distributions. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between the distal radial artery and the variables. Univariate and stepwise multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify the risk factors for puncture-related complications. All probability values are two-tailed, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for the significant risk factors of puncture-related complications.

Results

From February to November 2023, 45 diagnostic cerebral angiograms and 17 neurointerventions in 62 patients were performed or attempted with dTRA. Procedural success was achieved via dTRA in 47 (75.8%) patients, whereas 15 (24.2%) required conversion to TRA (n = 13) and transfemoral approach (n = 2). Reasons for failure included puncture failure (n = 8), inability to cannulate due to dRA spasm (n = 6), and inadequate catheter support of the left vertebral artery (n = 1).

Table 1 summarizes the patient and clinical characteristics of the study cohort and compares these factors between those with successful versus failed procedures. The mean age was (59.71 ± 10.75) years, and 40.3% (25/62) of patients were female. The mean BMI was (25.72 ± 3.27) kg/m2. The median diameters of the dRA and RA were (1.91 ± 0.26) mm and (2.34 ± 0.26) mm, respectively. 17 (27.4%) patients received dual antiplatelet therapy, 15 (24.2%) patients used a single antiplatelet agent, and 30 (48.4%) patients without antiplatelet therapy. A history of hypertension was noted in 82.3% (51/62), diabetes mellitus in 19.4% (12/62), and hyperlipidemia in 22.6 (14/62)%. 53.2% (33/62) were diagnosed with aneurysm on imaging, 9.68% (6/62) with internal carotid artery stenosis, 24.2% (15/62) with vertebrobasilar artery stenosis, and 12.9% (8/62) with others. There was no significant correlation between procedure success and any patient and clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Summary of patient and clinical characteristics of the study cohort, and comparison of factors between patients with successful versus failed procedure with dTRA

| Total (n = 62) | Procedural success (n = 47) | Procedural failure (n = 15) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient charateristics | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 59.71 ± 10.75 | 60.19 ± 10.74 | 58.20 ± 11.04 | 0.537 |

| Female, n (%) | 25 (40.3) | 18 (38.3) | 7 (46.7) | 0.565 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 25.72 ± 3.27 | 25.56 ± 3.38 | 26.24 ± 2.97 | 0.491 |

| Clinical charateristics | ||||

| Arterial diameter (mm), mean ± SD | ||||

| dRA | 1.91 ± 0.26 | 1.94 ± 0.27 | 1.81 ± 0.21 | 0.095 |

| RA | 2.34 ± 0.26 | 2.33 ± 0.27 | 2.39 ± 0.23 | 0.387 |

| Antiplatelet therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 17 (27.4) | 11 (23.4) | 6 (40.0) | 0.356 |

| Single antiplatelet use | 15 (24.2) | 12 (25.5) | 3 (20.0) | 0.929 |

| None | 30 (48.4) | 24 (51.1) | 6 (40.0) | 0.455 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 51 (82.3) | 38 (80.9) | 13 (86.7) | 0.900 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (19.4) | 10 (21.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0.762 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 14 (22.6) | 11 (23.4) | 3 (20.0) | 1.000 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Aneurysm | 33 (53.2) | 27 (57.5) | 6 (40.0) | 0.238 |

| ICAS | 6 (9.68) | 3 (6.38) | 3 (20.0) | 0.146 |

| Vertebrobasilar stenosis | 15 (24.2) | 11 (23.4) | 4 (26.7) | 1.000 |

| Others | 8 (12.9) | 6 (12.8) | 2 (13.3) | 1.000 |

dTRA distal transradial approach, SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index, dRA distal radial artery, RA radial artery, ICAS internal carotid artery stenosis

Pearson’s correlation coefficients for the dRA diameter were -0.148 (p = 0.321) for age, 0.287 (p = 0.051) for sex, 0.147 (p = 0.324) for history of hypertension, -0.207 (p = 0.163) for history of diabetes and -0.131 (p = 0.379) for history of hyperlipidemia. The correlation coefficient between the diameter of the dRA and BMI was 0.332 (p = 0.022), and that of the RA was 0.743 (p < 0.001), showing moderate and highly correlations, respectively.

Predictors of puncture-related complications after procedure

Postoperative puncture-related complications occurred in 17.0% (8/47) of the 47 patients who underwent successful procedures with dTRA. Of these, 8.5% (4/47) developed minor hematomas, but no major hematomas were observed. 2.1% (1/47) and 4.2% (2/47) of patients were diagnosed with dRA spasm and asymptomatic occlusion, respectively, on ultrasound examination. 2.1% (1/47) experienced neuropathy manifested as numbness on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, which resolved spontaneously after 3d.

Table 2 summarizes the patient characteristics and procedural variables of patients with successful procedures, and the comparison of factors between patients with puncture-related complications and those without puncture-related complications. Female gender was more common (75.0% vs 30.8%, respectively; p < 0.019), but BMI was lower in patients (22.09 ± 3.74 kg/m2 vs 26.09 ± 3.09 kg/m2; p < 0.016) with complications than in those without it. In addition, there were significant differences in the presence of dRA diameter between the two groups (p = 0.044).

Table 2.

Characteristics and procedural variables of patients with dTRA success, and comparison of factors with puncture-related complications

| Total (n = 47) | Non-complication (n = 39) | Complication (n = 8) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient charateristics | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 60.19 ± 10.74 | 60.31 ± 10.48 | 59.63 ± 12.69 | 0.872 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 25.56 ± 3.38 | 26.09 ± 3.09 | 22.99 ± 3.74 | 0.016* |

| Female, n (%) | 18 (38.3) | 12 (30.8) | 6 (75.0) | 0.019* |

| Clinical charateristics | ||||

| Arterial diameter (mm), mean ± SD | ||||

| dRA | 1.94 ± 0.27 | 1.97 ± 0.27 | 1.76 ± 0.23 | 0.044* |

| RA | 2.33 ± 0.27 | 2.36 ± 0.27 | 2.16 ± 0.24 | 0.061 |

| Antiplatelet therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 11 (23.4) | 10 (25.6) | 1 (12.50) | 0.733 |

| Single antiplatelet use | 12 (25.5) | 9 (23.1) | 3 (37.5) | 0.921 |

| None | 24 (51.1) | 20 (51.3) | 4 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 38 (80.9) | 33 (84.6) | 5 (62.5) | 0.340 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (21.3) | 7 (18.0) | 3 (37.5) | 0.449 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 11 (23.4) | 7 (18.0) | 4 (50.0) | 0.136 |

| Procedural variables | ||||

| Puncture side, n (%) | ||||

| Right | 46 (97.9) | 38 (97.4) | 8 (100) | 1.000 |

| left | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | |

| The indication of diagnostic angiography, n (%) | ||||

| Aneurysm (evaluation or follow-up) | 21 (44.7) | 17(43.6) | 4 (50.0) | 0.437 |

| ICAS (evaluation or follow-up) | 2(4.3) | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Vertebrobasilar stenosis (evaluation or follow-up) | 7 (14.9) | 6 (15.4) | 1 (12.5) | 0.733 |

| Others | 5 (10.6) | 5 (12.8) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Interventional therapy, n (%) | 12 (25.5) | 9 (23.1) | 3 (37.5) | 0.684 |

| Puncture time (min), mean ± SD | 2.06 ± 1.37 | 1.94 ± 1.26 | 2.66 ± 1.80 | 0.379 |

| Access time (min), mean ± SD | 4.16 ± 1.52 | 3.99 ± 1.59 | 4.97 ± 0.72 | 0.097 |

| Fluoroscopic time (min), mean ± SD | 12.01 ± 7.63 | 11.94 ± 7.54 | 12.37 ± 8.59 | 0.932 |

| Operation duration (min), mean ± SD | 43.79 ± 25.03 | 43.44 ± 22.45 | 45.50 ± 37.14 | 0.618 |

| Compression hemostatic time (min), mean ± SD | 156.28 ± 29.68 | 153.85 ± 29.19 | 168.13 ± 31.16 | 0.219 |

| Discharge time (d), mean ± SD | 4.11 ± 4.60 | 4.26 ± 5.0 | 3.38 ± 1.51 | 0.305 |

| Radiation exposure (Gy·cm2), mean ± SD | 39.26 ± 27.32 | 38.65 ± 26.05 | 42.24 ± 34.75 | 0.723 |

SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index, dRA distal radial artery, RA radial artery, ICAS internal carotid artery stenosis

*Indicates significant value (p < 0.05)

Table 3 details the univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analysis for risk factors of puncture-related complications. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed for the variables with statistically significant p values in Table 2 and revealed that only BMI (OR = 0.70, 95%CI 0.513 to 0.958; p = 0.026) remained independently associated with the complication. The cut-off value for BMI was 24.8 kg/m2 (specificity of 87.5%, sensitivity of 66.7%, AUC of 0.766) (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic analysis for risk factors of puncture-related complication

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysisa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

| Female | 0.15 | 0.026 to 0.843 | 0.031 | - | - | 0.077 |

| BMI | 0.70 | 0.513 to 0.958 | 0.026 | 0.70 | 0.513 to 0.958 | 0.026 |

| dRA diameter | 0.02 | 0.000 to 1.033 | 0.052 | - | - | 0.155 |

BMI body mass index, dRA distal radial artery

aForward LR method was used for multivariate analysis

Fig. 4.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. (III) The AUC was 0.72 (95%CI, 0.668 to 0.769). The cut-off baseline value for BMI was set to 24.8 with specificity of 87.5% and sensitivity of 66.7%, respectively

Discussion

Our results revealed that low BMI (< 24.8 kg/m2) was an independent risk factor for puncture-related complications after the procedure with dTRA. Furthermore, we found no significant correlation between procedural success and any patient and clinical characteristics in this study.

We reviewed 14 neurointerventional studies with a sample size of more than 10 cases, and the success rate of the procedure with dTRA, ranging from 76.7% to 98.7%, is shown in Table 4. We found that the massive variation between institutions depended largely on criteria for procedural success, which in some studies was determined by entry of the puncture needle into the lumen of the vessel or smooth advancement of the sheath, whereas others also needed to satisfy that the catheter was navigated into the target vessel on the aortic arch. Our puncture success rate of 87% was slightly lower than most previous studies. However, we achieved cannulation and procedure success in 77.4% and 75% of cases, respectively, which was close to what was reported by some other investigators. For example, Bhambhani et al [20] reported 93%, 78%, and 77% success rates for dTRA puncture, cannulation, and procedure, respectively. In our cohort, the dRA pulse could not be palpable in 53.3% (8/15) of the cases. Thus, puncture failure is considered the most common cause of procedural failure with dTRA. There are several reasons to explain our relatively high puncture failure rate. Firstly, Kiemeneij et al [21] reported that in 23% of cases the pulse of the radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox was too weak or imperceptible to attempt puncture. Moreover, radial artery diameter < 2 mm has been correlated with puncture failure and procedure failure [22]. Our study included all-comers without pre-selection, including those with a weak and poorly-palpable dRA pulse and dRA size < 2 mm, with the aim of more comprehensively assessing the feasibility and safety of dTRA. Secondly, Ultrasound-guided has been shown to improve the success rate of the first puncture in TRA and shorten the puncture time [3]. Mori et al [23] recently attempted ultrasound-guided for dTRA and found that the success rate of the procedure increased from 87 to 97% (P= 0.0384). However, we are unable to adopt this technique routinely due to limited conditions, but our operators are experienced, including having undergone at least 200 TRA and 50 dTRA procedures, which may preclude the influence of the learning curve. This was verified in a recent study where the learning curve for dTRA was overcome between 11 and 33 cases and further refinement at 40–50 cases [10]. Finally, in our case, the size of the radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox was approximately 80% of that in the forearm and tended to be smaller in females, as described in previous studies [5, 24]. Additionally, the tortuosity and angulations of the dRA are considered to cause difficulty in arterial puncture [6]. Therefore, puncture of dTRA may be more challenging compared to TRA, and preoperative ultrasound assessment of the size and running direction of the dRA and intraoperative real-time ultrasound-guided puncture may be helpful, especially for first-time operators.

Table 4.

Previous studies on the distal radial artery approach for cerebral angiography and neuroendovascular treatment

| Study (yr) | Patients | Number of procedure cases | Mean age (SD/Range) (yr) | Mean distal radial artery inner diameter (SD/Rang) (mm) | Proportion of interventions (%) | Type of interventions (No.) | Ultrasound guided (%) | Sheath size (%) | Success Rate (%) | Reasones for failure (No.) | Apporach conversion (No.) | Complication Rate (%) | Complication description (No.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunet et al., 2019 [4] | 85 | 85 | 53.8 (15) | 2.4 (0.6) | 0 | NA | 100% | 5Fr (100%) | 91.8% (78/85)a | RA spasm/Cannulation failure (7) |

TRA (1) TFA (6) |

0% | NA |

| Patel et al., 2019 [5] | 38 | 38 | 54.5 (11.5) | NR | 0 | NA | 100% | 5Fr (100%) | 89.5% (34/38) | Severe RA spasm (4) |

TRA (2) TFA (2) |

5.9% | Transient right wrist pain (2) |

| Saito et al., 2020 [6] | 51 | 51 | 59.4 (13.5) | 2.19 (0.41) | 0 | NA | 19.6% (10/51) | 4Fr (100%) | 92.2% (47/51)a | Cannulation failure (4) | TRA (4) | 2.0% | Transient peri-puncture site numbness (1) |

| Weinberg et al., 2020 [7] | 120 | 120 | 54.7 (14.7) | NR | 7.5% (9/120) |

Aneurysm (1) AVM/AVF/CCF (7) Others (1) |

100% |

5Fr (94.2%) 6Fr (5.8%) |

100% | NA | NA | 1.7% | Hematoma/RA spasm (2) |

| Kühn et al., 2020 [8] | 46 | 48 | 64.4 (35–84) | 2.3 (1.6–3.6) | 100% |

Aneurysm (18) CAS (6) MT (2) AVM/AVF (3) Others (14) |

100% | 6Fr (100%) | 89.6% (43/48) | Tortuous vessel anatomy/limited support of the catheters in the aortic arch (5) | TFA (5) | 2.1% | Asymptomatic dRA occlusion (1) |

| Kühn et al., 2020 [9] | 11 | 11 | 63.5 (10.2) | NR | 100% | Aneurysm (11) | 100% | 6Fr (100%) | 90.9% (10/11) | Severe brachial artery fibromuscular dysplasia (1) | TFA (1) | 0% | NA |

| Hoffman et al., 2021 [10] | 75 | 75 | 56.1 (14.8) | NR | 0 | NA | 100% | 5Fr (100%) | 98.7% (74/75) | NR | NR | 4.0% |

Hematoma (1) RA spasm (1) RA injury with contrast extravasation (1) |

| Kühn et al., 2021 [11] | 20 | 22 | 69.4 (53–87) | NR | 100% | CAS (22) | 100% |

6Fr (77.3%) 7Fr (4.5%) Sheathless (18.2%) |

90.9% (20/22) |

Persistent RAS (1) Insufficient catherter support and tortuous anatomy in a type 3 aortic arch for left CAS (1) |

TFA (2) | 0% | NA |

| Manzoor et al., 2021 [12] | 102 | 114 | 41.9 (15.2) | 2.4 (1.6–2.9) | 31.6% (36/114) |

Aneurysm (11) CAS (2) MT (3) AVM/AVF (7) Others (13) |

100% |

4Fr/5Fr (66.7%) 6Fr (33.3%) |

94.7% (108/114) |

Puncture failure (3) severe dRA Spasm (3) |

TRA (3) TFA (2) TUA (1) |

2.7% | Hematoma (3) |

| Ahmed et al., 2021 [13] | 64 | 64 | 56 (16–81) | NR | 26.6% (17/64) |

Aneurysm (8) MT (1) AVM (3) Others (5) |

100% | NR | 96.9% (62/64) |

Proximal RA occlusion (1) Anomalous brachiocephalic artery and aortic arch anatomy (1) |

TFA (2) | 1.6% | RA occlusion/injury (1) |

| Rodriguez Caamaño et al., 2022 [14] | 100 | 100 | 58 (15.6) | 2.03 (0.38) | 47% (47/100) |

Aneurysm (16) CAS (3) MT (14) AVM/AVF (4) Others (10) |

100% | 5Fr/6Fr (100%) | 96% (96/100) |

Puncture failure due to dRA dissection (1) Arterial loop at the elbow joint (1) Difficult catheterization of target vessel (2) |

TRA (1) TFA (3) |

6.0% |

Hematoma (3) dRA occlusion (1) dRA stenosis (2) |

| Chivot et al., 2022 [15] | 57 | 61 | 54.2 (30–86)b | 2.1 (1.7–2.6)b | 100% | Aneurysm (61) | 100% | 6Fr (100%) | 98.4% (60/61) | Guide catheter Kinking (1) | TFA (1) | 0% | NA |

| Umekawa et al., 2022 [16] | 30 | 30 | 67 (32–87) | 2.3 (1.7–3.2) | 30% (9/30) |

CAS (6) Others (3) |

NR |

4Fr (80%) 6Fr (20%) |

76.7% (23/30) | NR | TRA (7) | 3.3% | Hematoma (1) |

| Bhatia et al., 2023 [17] | 25 | 25 | 45.4 (13.5) | 2.09 (0.12) | 0% | NA | 60% (15/25) | 5Fr (100%) | 84% (21/25)a |

Servere dRA spasm (3) dRA dissection (1) |

TRA (3) TFA (1) |

4.0% | Hematoma (1) |

| Present study | 62 | 62 | 59.71 (10.75) | 1.91 (0.26) | 27.4% (17/62) |

Aneurysm (7) Vertebral artery stenting (8) Others (2) |

0% | 6Fr (100%) | 75.8% (15/62) |

Puchture failure (8) dRA spasm (5) Server RA spasm (1) Insufficient catherter support for left vertebral artery (1) |

TRA (13) TFA (2) |

17.0% |

Hematoma (4) dRA spasm (2) Asymptomatic dRA occlusion (1) Transient peri-puncture site numbness (1) |

NA not applicable, NR not reported, AVF arteriovenous fistula, AVM arteriovenous malformation, CCF carotid cavernous fistula, CAS carotid artery stent placement, MT mechanical thrombectomy, RA radial artery, dRA distal radial artery, TFA transfemoral approach, TRA transradial approach, TUA transulnar approach

aOnly refer to successful puncture and cannulation

bThis study included 32 embolizations of ruptured aneurysms and 29 embolizations of unruptured aneurysms. The dagger indicates that the data include only cases from the ruptured aneurysm group

In contrast, cannulation failure due to radial spasm or abnormal forearm vascular anatomy, such as arterial loops, tortuous vessels, and brachial artery fibromuscular dysplasia, were the leading causes of failure in ultrasound-guided procedure with dTRA, as shown in Table 4. It is worth mentioning that we performed forearm ultrasonography for all patients before the procedure and excluded cases with abnormal arterial anatomy. Therefore, in our study, all 6 patients with cannulation failure were due to radial artery spasms. In 5 of these patients, the radial artery spasm occurred at the anatomical snuffbox and could be directly converted from dTRA to TRA without repositioning or redraping. The remaining 1 patient, who suffered severe radial artery spasm of the forearm owing to repeated manipulation of the guidewire via the dTRA, was forced to convert to a transfemoral approach. In addition, a segment of physiologic tortuosity exists in the dRA above the radial styloid process of radius process, which can sometimes result in poor guidewire delivery [4]. Our experience has been to adopt a thinner guidewire (0.018 or 0.014 inches) and reshape its tip to the appropriate angle according to the vascular anatomy. Simultaneously, the guidewire was gently advanced under roadmap guidance to avoid inadvertent entry into other adjacent branch vessels.

Regarding catheterization of supra-aortic arch target vessels via dTRA, encouraging results were reported by Umeka [16] and Patel [4], with selective catheterization achieved in all intended vessels. In contrast, Saito et al [6] failed to selectively catheterize in 6 (8.6%) of 70 vessels, 5 of which attempted to catheterize the left internal carotid artery with right dTRA. Similarly, Bhatia et al [17] catheterized 96 vessels, 3 (2 left vertebral artery and 1 right vertebral artery) of which were unsuccessful because of the tortuous right subclavian artery. In our study, 1 patient failed to catheterize the left vertebral artery because the catheter herniated into the aortic arch due to inadequate proximal support and stability. We believe that this failure was due to an insufficient catheter length. The existing opinion suggests that the puncture point of the dTRA is shifted 3-5 cm distally from the TRA, which may compromise proximal support and distal operability of the catheter, especially in tall patients [4]. Additionally, although the anatomical pathway of the right dTRA is more advantageous for catheterizing the cerebral vessels, the left dTRA may be particularly useful in cases with acute left vertebral artery course or poor anatomy of the right vascular system.

Currently, there is still controversy about the factors that influence the procedural success in dTRA. Two previous cardiology studies indicate that low body weight, low BMI, and dual antiplatelet therapy are independent risk factors for dTRA procedure failure [25, 26]. However, a recent neurointerventional literature reported that no patient factor or medical history was associated with procedural success [27]. Similarly, our comparative analysis of successful and failed procedural cases did not reveal significant differences in patient and clinical characteristics between the two groups, including BMI and antiplatelet therapy, as shown in Table 1.

In the present study, puncture-related complications after the procedure were observed in 17.0% (8/47) of cases, a proportion significantly higher than the 0% to 6.0% reported in previous studies, as shown in Table 4. A possible explanation is that our puncture operations are often empirical rather than ultrasound-guided, and multiple punctures at the same site inevitably increase the risk of complications at the puncture site. Additionally, larger sheath (6Fr) insertions may damage the intima, which may cause subsequent dRA spasm or occlusion [28]. Hematoma was the most common complication. Minor hematoma occurred in 8.4% (4/47) of patients, all of whom received additional compression therapy, and no major hematoma events were observed. Spasms or occlusion of the dRA as well as neuropathy were infrequent, which is consistent with previous reports [6]. Anatomically, in the proximal part of the anatomical snuffbox, the radial artery gives off a superficial palmar branch that anastomoses with the ulnar artery to form the superficial palmar arch. There is a rich collateral network exists between the superficial palmar arch and the deep palmar arch. Therefore, even with severe spasm or occlusion of the dRA, antegrade blood flow to the hand is maintained, which is why we attempted to insert a larger sheath. Moreover, in our cohort, 1 of 47 (2.1%) patients experienced transient numbness of the fingers, which may be related to injury to the superficial branch of the radial nerve. Overall, these complications were not serious clinical events and appear to be acceptable.

However, few studies have focused on the risk factors for post-procedural puncture-related complications of dTRA. A recent interventional cardiology study showed that low weight, peripheral arterial disease, dual antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation, and percutaneous coronary intervention predicted intra-procedural puncture-related complications of dTRA [25]. In this study, we discovered that only low BMI was independently associated with the occurrence of puncture-related complications. Meo et al [29] found that males and patients with BMI > 30 exhibited larger diameter of dRA and may be ideal candidates for the dTRA. This is consistent with our results that there is a moderate positive correlation between BMI and dRA. Li et al [26] also pointed out that the dRA is thin and tortuous in patients with low BMI and may be correlated with more anatomical variations under the snuffbox. Based on the above factors, one possible mechanism is that patients with a low body mass index have smaller dRA inherently, which indirectly affects the difficulty and frequency of puncture, thereby increasing the risk of hematoma and other complications. Our findings provide important information for the selection of appropriate candidates for dRA and the prevention of postoperative puncture-related complications.

Several studies have described the application of the dTRA in various neuroendovascular treatments, including intracranial aneurysm embolization, carotid stenting, mechanical thrombectomy, and others, as shown in Table 4. Because of the caliber limitations of the dRA, introducer sheath is usually selected from among the 4- to 6-Fr systems. However, in two studies by Kühn et al [8], 7-Fr guiding sheath and even sheathless catheters with up to 8-Fr outer diameters (2.7 mm, Fubuki 6F, Asahi Intecc) were successfully inserted, respectively. This suggests that dRA insertion of large-diameter sheaths is possible in selected cases. However, a large number of studies are still needed to explore the optimal threshold of dRA diameter corresponding to different sheath sizes.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study that had typical limitations, such as selection bias and incomplete data. Meanwhile, the inherent risk factors were not further analyzed due to the small number of puncture-related complications in this study. Second, we did not find any factors associated with surgical failure, which may be related to the relatively small sample size. Third, this study was performed with 6F sheaths inserted in all patients, ignoring the size of their dRA diameters, without further evaluation of the impact of different caliber sheaths on procedural success and complications. Finally, regular ultrasound follow-up data are lacking for assessing long-term puncture-related complications and their prognosis; our results need to be confirmed in the future with a large sample of multicenter controlled studies.

Conclusions

Our cohort is the first study of risk factors for puncture-related complications after neurointerventional procedures with dTRA. This study demonstrated that a low BMI (< 24.8 kg/m2) is an independent risk factor for puncture-related complications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- dTRA

Distal transradial approach

- TRA

Transradial approach

- dRA

Distal radial artery

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Weikai Wang: drafting the original manuscript. YM: data collection and analysis. PS: conception and design of the study. WL and GF: material preparation. CW and CS: critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant number ZR2023MH001).

Data availability

The datasets generated or analysed during the current study are available in the [PubMed] repository. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Research Committee at Binzhou Medical University Hospital (October 2023/2023-KT-121). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Weikai Wang and Yonggang Ma contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Romano DG, Frauenfelder G, Tartaglione S, et al. Trans-Radial Approach: technical and clinical outcomes in neurovascular procedures. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3(1):58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinha SK, Jha MJ, Mishra V, et al. Radial Artery Occlusion - Incidence, Predictors and Long-term outcome after TRAnsradial Catheterization: clinico-Doppler ultrasound-based study (RAIL-TRAC study). Acta Cardiol. 2017;72(3):318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sgueglia GA, Lee BK, Cho BR, et al. Distal Radial Access: Consensus Report of the First Korea-Europe Transradial Intervention Meeting. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(8):892–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunet MC, Chen SH, Sur S, et al. Distal transradial access in the anatomical snuffbox for diagnostic cerebral angiography. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(7):710–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel P, Majmundar N, Bach I, et al. Distal Transradial Access in the Anatomic Snuffbox for Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2019;40(9):1526–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito S, Hasegawa H, Ota T, et al. Safety and feasibility of the distal transradial approach: A novel technique for diagnostic cerebral angiography. Interv Neuroradiol. 2020;26(6):713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg JH, Sweid A, Khanna O, et al. Access Through the Anatomical Snuffbox for Neuroendovascular Procedures: A Single Institution Series. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2020;19(5):495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn AL, de Macedo RK, Singh J, et al. Distal radial access in the anatomical snuffbox for neurointerventions: a feasibility, safety, and proof-of-concept study. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020;12(8):798–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhn AL, Singh J, de Macedo RK, et al. Distal radial artery (Snuffbox) access for intracranial aneurysm treatment using the Woven EndoBridge (WEB) device. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;81:310–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman H, Bunch KM, Mikhailova T, et al. Transition from Proximal to Distal Radial Access for Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography: Learning Curve Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2021;152:e484–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn AL, Singh J, Moholkar VM, et al. Distal radial artery (snuffbox) access for carotid artery stenting - Technical pearls and procedural set-up. Interv Neuroradiol. 2021;27(2):241–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manzoor MU, Alrashed AA, Almulhim IA, et al. Exploring the path less traveled: Distal radial access for diagnostic and interventional neuroradiology procedures. J Clin Neurosci. 2021;90:279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed M, Zyck S, Gould GC. Initial experience of subcutaneous nitroglycerin for distal transradial access in neurointerventions. Surg Neurol Int. 2021;12:513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez Caamano I, Barranco-Pons R, Klass D, et al. Distal Transradial Artery Access for Neuroangiography and Neurointerventions : Pitfalls and Exploring the Boundaries. Clin Neuroradiol. 2022;32(2):427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chivot C, Bouzerar R, Yzet T. Distal radial access for cerebral aneurysm embolization. J Neuroradiol. 2022;49(5):380–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umekawa M, Koizumi S, Ohara K, et al. Distal radial artery approach is safe and effective for cerebral angiography and neuroendovascular treatment: A single-center experience with ultrasonographic measurement. Interv Neuroradiol. 2024;30(2):280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia V, Kesha M, Kumar A, et al. Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography Through Distal Transradial Access: Early Experience with a Promising Access Route. Neurol India. 2023;71(3):453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zussman BM, Tonetti DA, Stone J, et al. Maturing institutional experience with the transradial approach for diagnostic cerebral arteriography: overcoming the learning curve. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(12):1235–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertrand OF, Larose E, Rodes-Cabau J, et al. Incidence, predictors, and clinical impact of bleeding after transradial coronary stenting and maximal antiplatelet therapy. Am Heart J. 2009;157(1):164–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhambhani A, Pandey S, Nadamani AN, et al. An observational comparison of distal radial and traditional radial approaches for coronary angiography. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2020;32(1):17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiemeneij F. Left distal transradial access in the anatomical snuffbox for coronary angiography (ldTRA) and interventions (ldTRI). EuroIntervention. 2017;13(7):851–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan ZX, Zhou YJ, Zhao YX, et al. Anatomical study of forearm arteries with ultrasound for percutaneous coronary procedures. Circ J. 2010;74(4):686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori S, Hirano K, Yamawaki M, et al. A Comparative Analysis between Ultrasound-Guided and Conventional Distal Transradial Access for Coronary Angiography and Intervention. J Interv Cardiol. 2020;2020:7342732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y, Ahn Y, Kim MC, et al. Gender differences in the distal radial artery diameter for the snuffbox approach. Cardiol J. 2018;25(5):639–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikuta A, Kubo S, Osakada K, et al. Predictors of success and puncture site complications in the distal radial approach. Heart Vessels. 2023;38(2):147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Y, Sun X, Chen R, et al. Feasibility and Safety of the Distal Transradial Artery for Coronary Diagnostic or Interventional Catheterization. J Interv Cardiol. 2020;2020:4794838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erdem K, Kurtoglu E, Kucuk MA, et al. Distal transradial versus conventional transradial access in acute coronary syndrome. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2021;49:257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen T, Li L, Yang A, et al. Incidence of Distal Radial Artery Occlusion and its Influencing Factors After Cardiovascular Intervention Via the Distal Transradial Access. J Endovasc Ther 2023:15266028231208638. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Meo D, Falsaperla D, Modica A, et al. Proximal and distal radial artery approaches for endovascular percutaneous procedures: anatomical suitability by ultrasound evaluation. Radiol Med. 2021;126(4):630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analysed during the current study are available in the [PubMed] repository. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.