Abstract

Background

Maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity in conflict-affected northeastern areas of Nigeria, such as Yobe State, are disproportionately higher than those in the rest of the country. There is limited evidence on the factors that influence maternal and newborn health (MNH) policymaking and implementation in this region, particularly with respect to the impact of conflict and context-specific issues. This study explores the political, economic and health system factors that drive the prioritization of MNH policies in Yobe State. The aim of this study was to elucidate the conflict-related factors influencing MNH outcomes, which could inform targeted interventions to improve MNH.

Methods

The study is a descriptive case study that relies on multiple data sources and is guided by the Health Policy Analysis Triangle. We reviewed national and subnational research, technical reports and policies related to reproductive health and the MNH in Nigeria since 2010. Following stakeholder mapping, we identified and invited prospective participants in the MNH policymaking space. Nineteen stakeholders from the government, civil society and nongovernmental organizations, donor agencies, and public and private sector health providers in Yobe State participated in the semistructured in-depth interviews. Data were collected from November 2022 through January 2023 and were thematically analysed via Dedoose software.

Findings

MNH services in Yobe State have received considerable attention through initiatives such as the National Midwifery Service Scheme, free MNH services, training of midwives with deployment to rural areas, and health facility renovations. The effective implementation of MNH services and policies faces challenges due to insufficient funding, and sustainability is hampered by changes in governance and political transitions. The Boko Haram insurgency exacerbated the humanitarian crisis in Yobe State and disrupted MNH services due to the displacement of populations and the decline in the number of health workers. Additionally, sociocultural and religious beliefs hinder timely access to and utilization of MNH services. Although policies and guidelines for MNH services exist in the state, they are inadequately disseminated to health providers, which affects their effective implementation across facilities. Collaboration and intersectoral coordination platforms exist, but competition and rivalries among unions, political entities, and implementing agencies sometimes impede progress.

Conclusion

Enhancing MNH services in Yobe state requires increased commitment for funding through the Northeast Development Commission rehabilitation fund; strengthening the health workforce, safety and retention plan; promoting gender inclusivity within the health sector; and addressing sociocultural barriers to women’s health-seeking behaviors. Concrete, time-bound plans for policy dissemination are necessary to ensure effective service implementation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13031-024-00628-y.

Keywords: Maternal and newborn health, Yobe state, Nigeria, Health policy

Background

The United Nations (UN) global strategy to reduce the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and neonatal mortality rate (NMR) to less than 70 per 100,000 live births and 12 per 1000 live births per year by 2030 [1] adds enormous pressure on countries such as Nigeria, with extremely high MMR and NMR rankings [1]. The Lancet Nigeria Commission [2] made bold recommendations for improved investment in health and enforcement of existing polices to address the population health needs of Nigerians. Unfortunately, Nigeria contributes 28.5% of all global maternal deaths (1,047 per 100,000 live births) and 12% of neonatal deaths (35 per 1000 live births) [3]. In some conflict-affected areas, such as northeastern (NE) Nigeria, there are more than 1500 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births and 61 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births [4]. Most maternal, newborn and child deaths in Nigeria occur in northern states, which are challenged by Boko haram insurgency and weak health systems, poverty and sociocultural practices that negatively affect health outcomes [5].

Nigeria also ranks high on the Fragile States Index due to insecurity, particularly stemming from the Boko Haram insurgency in Northeastern region [6]. This poses significant challenges to healthcare systems and leads to the destruction of health infrastructure, displacement, a shortage of health workers [7], and sometimes complete cessation of healthcare services [6]. These disruptions have profoundly affected up to 80% of the rural population in the NE region [6]. Without adequate planning for the prioritization of health services, these disparities in maternal and newborn mortality will continue to worsen [5, 6]. The purpose of this study is to explore the political, economic and health system factors that drive the prioritization of MNH policies in Yobe State. This study aims to elucidate the factors influencing MNH outcomes in conflict-affected contexts in the state and inform policies or interventions to mitigate the barriers to quality MNH services.

Methods

Study design

This was a descriptive case study [8] that explored how factors related to the policy actors, content, context, and processes influence MNH prioritization in Yobe State, Nigeria. The study relied on multiple sources of data, including a literature review and in-depth interviews with key stakeholders in the MNH decision-making and implementation space in government, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), bilateral and multilateral institutions, civil society, and health care providers.

Conceptual Framework

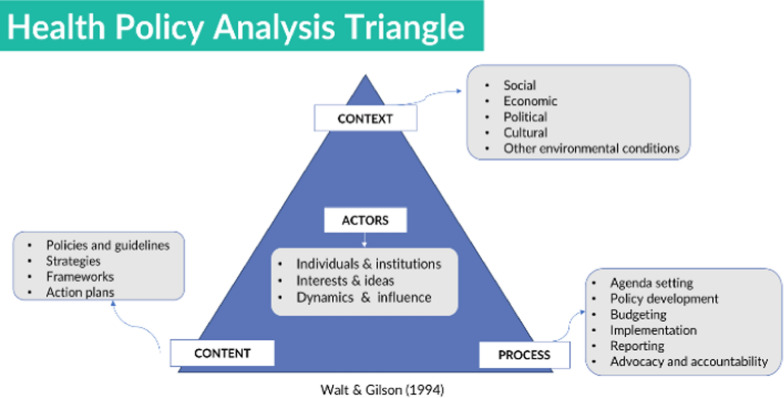

The study utilized the health policy analysis (HPA) triangle [8] to examine the political, economic and health system factors that influence MNH policy and action in Yobe State. Instead of solely focusing on policy content, the HPA framework considers processes, context, and events related to policy design and implementation. It involves analysing actor interests and influences across various levels of the health system, prevailing ideas, evidence, power dynamics, and political economic factors [8]. This framework has been used to explore political economy factors in humanitarian contexts in South Sudan [9]. The HPA triangle, illustrated in Fig. 1, guided both the research questions and the data interpretation in this study.

Fig. 1.

Health policy analysis triangle by Walt and Gilson [10]

In this analysis, the HPA framework served as a valuable tool, guiding actions that prioritized the MNH through funding, service provision, and organizational arrangements. Descriptions of the various HPA components used in this study are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conceptual framework components and descriptions

| Framework component | Themes | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Content | MNH policies and guidelines | All policies and guidelines, laws and initiatives that support MNH, including Gender Equity and Social Inclusion |

| Process | MNH policy implementation strategies and accountability | The processes for policy making, dissemination, and implementation at all levels of health system, including feedback mechanisms, and accountability for service delivery by healthcare workers in MNH |

| Context | MNH prioritization environment, limitations, and challenges | MNH prioritization by providers, community, and decision makers including limitation and challenges |

| Actors | Stakeholders by position or influence in MNH decision-making space | Individuals, institutions, organizations, and communities involved in decision making, implementation and utilization of MNH services |

Participant selection

The participants were identified through stakeholder mapping by the study team (RSA, CM and EI) to purposively identify a diverse pool of participants at the national and state levels on the basis of MNH experience, roles, and areas of expertise. Twenty-one potential participants were invited to participate in the study via a structured recruitment script. Our sample of participants included government officials from the Federal and State Ministries of Health (n = 7), multilateral and NGOs, local/civil society organizations (n = 7), professional associations, and public and private sector health providers (n = 5). A total of 19 stakeholders (12 males and 7 females) responded and were interviewed.

Data collection

We conducted a literature review of academic, policy, and technical reports to understand the current evidence on MNH policy and programs in Nigeria, the Northeast Region, and Yobe State in particular. The following databases were searched: PubMed, Google Scholar, organizational websites, and physical documents and reports. The literature review informed the research questions and interview guides and provided the foundation for understanding the broader context and framework relevant to the study objectives. Semistructured interview guides (Annex 1) tailored for each stakeholder group were used to conduct nineteen in-person interviews in English from November 2022 through January 2023. The semistructured interview guides were piloted in Abuja immediately after the data collection training. The interviews were conducted by members of our research team (RSA, CM, KA, and EI). Depth and saturation were reached at approximately 16–18 interviews on the basis of recurring themes. However, the team interviewed all the respondents because it was important to include participants from all the sectors.

Data analysis

The audio files were transcribed verbatim by the research team members (SII and KA) to ensure the preservation of original meanings. To maintain confidentiality, the transcripts were anonymized, ensuring that participants could not be identified from their responses.

Dedoose® (version 9.0.90) software was used to analyse the data. Using the HPA conceptual framework, interview guides and literature, a codebook was developed (annex 2), and the interview transcripts were analysed deductively. Key conceptual framework components were used as parent codes (Table 1), while descriptive codes were created from interview guides and added as child codes. The codebook was piloted, and additional codes were added while existing codes were refined. In the first level of coding, descriptive codes were applied to the data. In our analysis, the data richness was determined on the basis of a 50% response across the code and descriptor and an assessment of the code application chart. The team then exported the data and reviewed excerpts, codes, and descriptors to assess emerging themes.

In the second level of coding, the initial descriptive codes were categorized into emerging pattern codes in Microsoft Excel, which were described as subthemes under the main HPA framework components. The research team met and discussed the emerging themes and interpretations and drew up recommendations on the basis of the findings. The team engaged in reflexive exercises to understand their positionality and how it influenced analysis and interpretation. Memos in Dedoose® and systematic notes in Microsoft Excel were used to record reflexive judgments.

Results

Prioritization of MNH services in Yobe State

These findings are organized according to the subthemes that emerged from the interviews in alignment with the HPA framework components. When asked about MNH policies, guidelines, implementation and funding, participants identified commendable initiatives by the government and areas of critical gaps.

Content

Policy: According to the respondents, national policies and guidelines are adopted for state-level implementation, with minor adaptations to meet the unique requirements and characteristics of Yobe state. A critical data review revealed that a national health policy aimed at achieving health for all Nigerians was first disseminated in 1988 and later revised in 2004. The updated policy outlines the goals, structure, strategy, and direction of Nigeria’s health care delivery system [11]. We found that MNH is a significant priority in response to the high maternal mortality ratio in NE Nigeria. Various government policies and initiatives have been established with the aim of reducing maternal death, such as the following: (1) Free maternal, newborn, and child health services, which provide free medical services for pregnant women and children under five years of age. The goals of the MNH component of this policy are to improve access to and the number of deliveries conducted by skilled birth attendants; (2) HIV/TB and malaria prevention policies for pregnant women and newborns, which provide free antiretroviral treatment and malaria prevention for pregnant women living with HIV; (3) Renovation and equipment in health facilities; (4) Provision of ambulance services to improve access to emergency care; and (5) The Midwifery Service Scheme, which is a national policy that continues in the State to offer immediate employment opportunities for midwives. However, our review revealed some regional disparities in health service delivery and resource availability from the national level to the state level [12]. This disparity is reflected in several health outcomes reported in the 2008 Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), which reported a child mortality rate ranging from a low of 32 deaths per 1000 children in the Southwest Zone to 139 deaths per 1,000 children in the Northwest Zone [13]. A list of selected policy documents from 2009 to 2022 in relation to MNH prioritization in Yobe State is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Policies related to MNH prioritization

| Policy | Year established |

|---|---|

| Midwifery service scheme | 2009 |

| National policies on the implementation of HIV, TB, and malaria response | 2011 |

| Yobe State strategic health development plan | 2013–2015 |

| National Policy on task shifting and sharing | 2014 |

| Yobe State human resource for health | 2014 |

| National strategic health development plan | 2021–2025 |

| Nigerian National Gender Policy | 2021 |

| Yobe State Social equity initiative | 2022 |

Other policies and new initiatives in response to emergency MNH service demand include the Yobe State Contributory Health Management Agency [14], the Yobe State Drug and Medical Consumables Management Agency [15], and the Yobe State Emergency Medical Ambulance Service [16], which were established to cater to patients at all levels. The state government provides medications and other essential services at no cost to pregnant women. The basic healthcare and social equity policy launched in June 2022 [17] addresses the National Mandate for Gender Equity and Social Inclusion policy and ensures free health services for women with disabilities.

Funding and collaboration

Among policymaker respondents, MNH prioritization was discussed in terms of budget allocation for specific sectors. Although this varies annually and changes on the basis of government priorities and funding availability, the MNH still receives higher budget allocation than other sectors do. According to two of the participants:

Initially, the state budget for health was approximately 9.7%,... he [the governor] recommended an increase to 13%. He also asked for an increase in the primary healthcare budget to at least 25% of the health budget. Therefore, what is allocated to other ministries and agencies is the remainder. Policymaker 11.

...the free drug program is a fund that comes every month for the past thirteen years. It is specifically meant for maternal child health. It has increased from ten million Naira to eighteen million and currently thirty-five million Naira. This fund cannot cover all the facilities, so representative beneficiaries from each facility are selected for support. This may not be adequate but at least the support is there... CSO 12.

In addition, funding from development partners such as the World Health Organization, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, the United Nations Fund for Population Activities, and the United Kingdom’s foreign commonwealth development office complements access to MNH services. Various respondents among healthcare workers and civil society organizations mentioned that the government prioritizes funding allocation for MNH services by investing in upgrading colleges and health facilities and regularly paying salaries for staff motivation and retention.

Importantly, some participants highlighted deficiencies in budgetary distribution related to political interests in budget allocation, disbursement, and management. This hinders the comprehensive implementation of MNH policies and initiatives in the State.

Processes

Policy implementation and utilization: Due to high maternal and neonatal mortality rates, Uneke et al. [13] highlighted the need for context specific, evidence-informed policies for MNH implementation. Decision-making policies that translate theories to reality in practice are needed. This study revealed multiple MNH policies as well as gaps in dissemination to end users. Our findings suggest that strong cooperation and collaboration exist between MNH stakeholders and actors. In communities, traditional rulers and health providers work as teams to implement MNH services through advocacy and demand creation. The state government, schools and hospitals collaborate to ensure that health care workers (HCWs) are trained and deployed to facilities, especially in rural areas. Through the midwifery service scheme, the government employs and reintegrates retired midwives into the workforce to mentor younger midwives. To ensure the availability of midwives in rural communities, Yobe State has implemented a newly accredited 2-year community midwifery program to rapidly educate and deploy graduates to primary health centers. Another policy implementation example highlighted by the participants is the gender-based violence policy and guidelines, which are implemented through a referral pathway between health facilities and the Ministry of Women Affairs. This pathway establishes structured mechanisms for identifying, referring, and supporting victims and survivors.

Traditional birth attendants (TBAs) are highly utilized in Nigeria, especially in rural areas [18], due to a shortage of midwives and a lack of access to health care facilities. The government encouraged training TBAs to identify danger signs and the need for referrals. Through such training, TBAs can form a bridge to achieve safe motherhood objectives [18]. To prevent and reduce maternal and infant mortality and morbidity, the HCWs engaged and educated TBAs and encouraged them with stipends of five hundred Naira to refer pregnant women to health facilities. The inclusion and engagement of TBAs has expanded access to MNH services in communities. Even though the stipend is no longer given, TBAs still refer pregnant women for services.

There were several other examples of collaboration between policymakers and health facilities during supportive supervision and monitoring visits. Meeting with the local government and primary healthcare leadership enhances community collaboration. The collaboration between healthcare facilities and NGOs was identified as a positive factor by healthcare professionals and policymakers. This enhances the capacity to provide supplemental structures, supplies, and additional workers to help meet MNH service needs.

Evaluation and accountability: According to the respondents, to ensure quality implementation and accountability among service providers, implementation processes are monitored by various mechanisms. HCWs are held accountable through monitoring and supportive supervision for services such as task-shifting/task-sharing, audit/review meetings, standard quality requirements for suppliers, and the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response (MPDSR) system [19], along with the action obstetric quality assurance platform. The effectiveness of these mechanisms is often undermined by the actions of administrators and health providers. For instance, the MPDSR is not always completed. According to one of the policymakers:

This has a serious issue... because when a woman dies inside or outside a facility, nobody checks what led to her death. They will just say, this is her time. Policymaker 09.

Feedback mechanisms: The participants reported that feedback channels for clients include suggestion boxes at various locations in health facilities and customer care hotlines. These mechanisms create a feedback loop that promotes communication and accountability among HCWs and contributes to improved practices. The suggestion boxes provide confidential platforms for individuals to anonymously submit suggestions, complaints, or feedback, thereby identifying implementation successes and challenges. The respondents mentioned that customer care hotlines help offer direct and accessible avenues for clients to express their concerns, seek assistance, or provide feedback on MNH services through the hospital administration office.

Another effective feedback mechanism according to the participants is ward development committees, which constitute a community structure that plays a pivotal role in fostering community engagement and feedback at the community level. They enable clients to advocate for their needs and provide input on local service delivery.

Context

Religious and sociocultural factors: We found that MNH services are generally accepted. However, the respondents expressed the importance of cultural and religious awareness among HCWs, as these awareness levels may impact service uptake and client satisfaction. For example, there is a religious belief that home births are divinely sanctioned, which can hinder implementation and timely access to MNH services. According to one of the participants:

“... seeking healthcare is an indicator that you do not believe in God” CSO 19.

Additionally, gender and cultural norms require spousal permission to access medical care. Some male partners prefer female HCWs for all MNH service delivery:

“…in some places, the husbands will not want a male midwife or nurse to care for their wives. Sometimes the women prefer female providers.” Policymaker 01.

Some respondents contend that male staff are prohibited from entering labor and delivery wards; this restriction may underutilize male midwives and impact service quality and accessibility.

Impact of crises on MNH prioritization

The crisis in Yobe State has resulted in limited access to MNH services due to the destruction of infrastructure and displacement, which has led to long distances from functional health facilities. According to a policymaker:

“… because of the seriousness of the Boko haram insurgency in the state, … many maternal health clinics and facilities were shut down. Approximately seventy to eighty facilities were destroyed completely by the insurgents. Drugs were looted, and the facilities were burned to ashes....” Policymaker 13.

Additionally, women had to seek care from TBAs due to HCW shortages or nonavailability and facility closure. A health provider stated that:

“...during the Boko haram crisis, for 4--5 months, nobody was in the facility. It truly affected the women. Only TBAs were attending to the women. When issues arise, they will have to reach Geidam, which is very far, most times a woman who is seriously bleeding dies before reaching there.” HCW 02.

While Boko Haram's violence remains the primary cause of population displacement, community clashes and natural disasters are also contributing factors in some states. More than 1.2 million people have been displaced in northern and central Nigeria due to the Boko Haram insurgency, which continues to drive large-scale population movements [20]. The International Organization for Migration and Displacement Tracking Matrix identified 1,188,018 internally displaced persons in Nigeria's Northeast Region, covering Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, and Yobe states. Additionally, Nigeria’s National Emergency Management Agency has registered 47,276 IDPs in the central regions of the country. This results in the total number of displaced persons identified being 1,235,294 in northern and central Nigeria[20].

When asked about the camps of internally displaced persons, most of the participants reported that many women experienced rape, violence, psychological disturbances, and/or teenage pregnancies. Additionally, women’s access to family planning services is sometimes nonexistent. Insurgency undermines HCWs' effectiveness, impacting their income and investments and restricting their access to clients and communities. The stressors faced by HCWs are heightened, with reported cases of threats, abductions, and murder. They reported that wearing health care uniforms makes HCWs vulnerable to kidnapping. Newly employed HCWs are hesitant to accept postings in insecure areas because of the significant challenges faced by those who are already working in those locations. Reported stressors also include physical and mental exhaustion, a shortage of HCWs resulting in heavy workloads and limited accommodation. An NGO respondent shared the following:

“The critical issue is a lack of accommodation in rural areas. Additionally, when [community midwifery] students graduate and return to their communities, they do not have senior midwives to mentor them. This affects the quality of the services rendered.” NGO 14.

The participants emphasized the pressing need for increased compensation for personnel in remote and insecure areas, given the harsh conditions they endure, especially the scarcity of trained staff in most health facilities.

Actors

Stakeholder collaboration is essential for supporting government efforts in terms of maternal and newborn health. These collaborations bring together diverse expertise, resources, and perspectives, enhancing the overall effectiveness of MNH initiatives. However, the dynamics of relationships and power can significantly influence the policymaking and implementation processes, often determining the success or failure of these initiatives.

Key Actors in MNH Decision-Making: MNH prioritization is deeply influenced by several key actors. Community leaders, who represent the interests of their community members, play a crucial role. They are trusted figures within the community and can mobilize support for MNH initiatives because of their perceptions and interests. Their endorsement significantly impacts the uptake of MNH services.

Institutions that produce and employ health workers, such as medical and nursing schools, are critical in ensuring a steady supply of qualified personnel. These institutions not only train future healthcare workers but also shape the standards and expectations for MNH service delivery. Hospital administrators constitute another pivotal group that is responsible for implementing health policies. They manage resources, oversee operations, and ensure that MNH services are delivered efficiently and effectively.

Donors and implementing organizations, including international agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), provide vital financial support and resources. They often bring innovations, technical expertise, and additional funding that complement government efforts. However, a few respondents highlighted the need to strengthen coordination and collaboration platforms among stakeholders. Effective coordination can reduce duplication of efforts and minimize rivalry, especially among NGOs, ensuring that resources are used efficiently and that efforts are not fragmented or counterproductive.

Political leaders, such as governors, legislators, health commissioners, executive secretaries, and primary health leaders, play decisive roles in creating MNH policies and allocating the necessary funding. Their decisions directly impact the availability and quality of MNH services. Healthcare workers (HCWs) and consumers also play significant roles through active engagement in service delivery. HCWs are on the front lines, implementing policies and providing care, whereas consumer feedback and participation can drive improvements in service quality and accessibility.

Politics and power dynamics

The prioritization of MNH services is influenced by broader governance structures, continuity, and shifting priorities. Policymakers noted that Nigeria's complex governance structure impacts decision-making at various levels. For example, any change in leadership can lead to changes in key positions, such as legislators, health commissioners, executive secretaries, and primary health leaders. This often necessitates a realignment of relationships and priorities, which can disrupt established implementation timelines, objectives, and funding allocations. Frequent changes in leadership can lead to instability in policy direction and inconsistent support for MNH initiatives. Moreover, there can be challenges with the perception of health as a priority over other sectors. Some political leaders may prioritize areas such as infrastructure, security, or education over health, affecting the amount of attention and resources dedicated to MNH services. This can result in insufficient funding, delayed implementation of policies, and inadequate support for HCWs.

“… one of the biggest challenges is making health a priority. Looking at the Nigerian context, this will remain a problem because I was talking to one of the governors, and he said, look, with the salary of one health worker, I can employ four teachers” Policymaker 09.

This perception affects the continuity and prioritization of MNH services, especially with changes in governance.

Gender inclusion and decision making: When asked about gender disparity in decision-making roles, many participants stated that only a few women occupy senior administrative positions. Some of the respondents indicated that women face marginalization and purposeful frustration in senior leadership positions because at the health facility level, female employees are rarely involved in decision making, and the majority of female workers are frontline health providers.

“Environmental health staff will be in charge of the facility when a senior nurse is there because the nurse is a female; she reports to him very rarely in fact I have a very good friend of mine who has been contesting for one of the Federal Medical Centers looking for the position of the Chief Medical Director, she did not get it.” NGO 14.

Additionally, the respondents highlighted that the involvement of women and women-led organizations, such as the Ministry of Women's Affairs, Initiatives such as the Ward Development Committee, which is aimed at appointing female representatives in communities, has been instrumental in enhancing women's participation in decision-making as implementers rather than decision makers. Poor awareness and training of end users of policies and guidelines were identified as a gap, especially in relation to the Nigerian National Gender Policy [17], which protects individuals from discrimination.

Discussion

This study reveals multiple policies and contextual factors that drive MNH prioritization in Yobe State. Funding allocation for MNH services is clearly a high priority for the state government because of the high maternal and neonatal mortality rates in the region. Yearly government budget allocation for maternal and newborn health and financial donations from development partners play crucial roles in financing the MNH. However, there is a high dependency on donor funding for MNH services, which is a sustainability concern. The state has several program implementation strategies and initiatives aimed at reducing barriers to MNH services and health worker shortages. However, policy and guideline dissemination to frontline health workers was identified as a serious gap. This was also demonstrated in other studies in conflict-affected regions [21], Latin America and the Caribbean [22].

Other challenges that influence MNH funding include political will and a lack of governance continuity, as highlighted in similar situations observed in Kaduna, Nigeria [23]. A lack of political capital often results in insufficient investment, as highlighted in this study, as the perception of recruiting and retaining healthcare personnel is a greater financial burden than that of other workers, such as teachers. In addition, our findings revealed that MNH resources are sometimes reprioritized for security and emergency response. Similar issues that result in financial restrictions have been reported in Nigeria [23] and other African countries [21]. There is a need to establish a robust strategy to actively engage political leaders in Yobe State to ensure the long-term sustainability of the MNH. This involves creating a sustained dialogue with key policymakers, demonstrating the direct impact of MNH programs on community well-being and development, encouraging political leaders to integrate MNH priorities into broader health agendas and policies, and securing budgetary allocations and institutional support through rehabilitating funding from the Northeast Development Commission [24].

The contextual issues highlighted in this study include the effects of armed insurgency and insecurity on MNH services, such as staff shortages, recruitment difficulties, kidnapping and murder among HCWs, destruction of health infrastructure, and restricted access to services for pregnant women. Our findings were consistent with those of other studies from South Sudan and Afghanistan, as well as Nigeria [9, 21], where armed conflict hampered the provision of basic MNH services, resulting in low utilization of services. Like other crisis-affected and fragile contexts, our study revealed that HCWs in high-risk areas experience excessive workloads, risk for kidnapping and murder, among other adverse conditions [9, 21]. There is a need for the government to consider additional recruitment of HCWs with strong ties to communities, as recommended in other studies from African conflict-affected countries [25, 26]. In addition, the government should increase security interventions for HCWs [21] and financial incentives such as hazard allowances, short-term rotational posting to reduce staff burnout, and accommodations with safety devices such as walkie-talkie devices for easy and safe communication during emergencies [24].

As in other areas of northern Nigeria (Kaduna, Jigawa, and Zamfara), cultural and religious beliefs limit the utilization of MNH services because of the general preference for female birth attendants [23]. Considering the challenges associated with HCW recruitment and retention, where there are limited female skilled birth attendants, these preferences interfere with safe MNH service delivery. Research from South Sudan [25], Nepal [7] and other areas in Nigeria [23] revealed similar attitudes, with pregnant women and their husbands expressing concern about male midwives seeing women’s bodies during delivery. While HCW gender preferences are advocated, community engagement and education about the benefits of skilled birth delivery are necessary to eliminate preventable maternal and newborn deaths. Healthcare providers should encourage the use of junior HCWs as companions during delivery to minimize these cultural concerns while protecting the privacy of other women in the labor room.

Despite political and governance changes are unavoidable, a structured and cohesive collaborative strategy for timely advocacy can help mitigate the negative impact of these changes. In terms of disparities in gender representation among health leaders in policy and decision-making forums, the inclusion of women necessitates intentional efforts toward gender balance to address MNH needs comprehensively. Previous studies have documented the positive effect of gender inclusion in decision-making as well as the inclusion of women with disabilities as drivers of improved outcomes [27, 28]. The state government should be more involved in driving stakeholder collaboration to achieve intersectoral quality of care and service availability to ensure that community needs are prioritized appropriately [29].

Although this study presents issues related to MNH prioritization in Yobe State, Nigeria, the data collection period may have limitations in capturing dynamic changes or evolving policy perspectives over time. MNH priorities and policies could have changed before or after the study period, affecting the relevance of these findings. While reflexivity exercises were conducted to acknowledge researchers' biases and positions, eliminating the influence of researcher subjectivity on data interpretation and analysis is challenging.

Conclusions

This study highlights the complex landscape of MNH prioritization in Yobe State, Nigeria, revealing both commendable initiatives by the government and areas of critical gaps. Programme implementation efforts demonstrate a commitment to addressing barriers to accessing care and mitigating health worker shortages, particularly midwives. However, the sustainability of these programs requires careful planning to ensure lasting benefits. Other significant challenges highlighted in this study that had profound impacts on MNH service delivery included gaps in policy dissemination to frontline healthcare workers, insufficient funding and cost-cutting measures, security, cultural beliefs, gender disparities in health leadership and decision-making forums. Addressing these challenges necessitates timely advocacy and streamlined processes for efficient resource management. Sustained political will, strong governance structures and inclusive stakeholder collaborations are also needed to retain the benefits of implementation.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants who took part in this study. We acknowledge the support of the research staff of the International Research Center of Excellence of the Institute of Human Virology, Nigeria, and the EQUAL Research Consortium. We also thank Hannah Tappis and Paul Spiegel for their review and valuable insights into this manuscript.

Author contributions

ENI, CPM, MM and NK conceived the study design and data collection tools. RSA and ENI supported the design of the methods. RSA led the data collection and analysis. SII, KOA, CPM, GO, ENI, HS and RHA assisted in data collection and analysis. RHA led the manuscript preparation, assisted by ENI, CPM, SII and RSA and MM and NK substantively reviewed and provided critical feedback. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UK International Development from the UK government as part of the EQUAL Research Programme Consortium.

Data availability

The data generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions, but anonymized transcripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by the Yobe State Ministry of Health Ethics Committee under the reference MOH/GEN/747/VOL.I. All the interviewees voluntarily gave their prior informed consent to the interview and audio recording. Data were collected and analysed with complete confidentiality. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or non‑financial competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.“United Nations in Nigeria.” Accessed: Jun. 03, 2024. https://nigeria.un.org/en

- 2.Abubakar I, et al. The lancet Nigeria commission: investing in health and the future of the nation. Lancet. 2022;399(10330):1155–200. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02488-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.“Analytical Fact Sheet Maternal mortality: The urgency of a systemic and multisectoral approach in mitigating maternal deaths in Africa Rationale,” 2023.

- 4.Umar N, Wickremasinghe D, Hill Z, Usman UA, Marchant, T. Understanding mistreatment during institutional delivery in Northeast Nigeria: a mixed-method study. 2019; 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Fadeyibi O, De Wet N. Barriers to accessing health care in Nigeria: implications for child survival. Glob Health Action. 2014;1:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Development, S. Boko–Haram insurgency and rural livelihood dilemma : implication for Boko–Haram insurgency and rural livelihood dilemma : implication for sustainable development in North‒East Nigeria Rebelia Boko–Haram i dylemat braku środków do życia na wsi : implika,” 2023; 10.35784/pe.2023.1.23.

- 7.Chukwuma A, Ekhator-mobayode UE. Armed conflict and maternal health care utilization: evidence from the Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 2019. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bigirinama RN, Mothupi MC, Lyabayungu P, Batu M, Ngaboyeka GA, Bisimwa GB. Prioritization of maternal and newborn health policies and their implementation in the eastern conflict affected areas of the Democratic Republic of Congo: a political economy analysis. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2024. 10.1186/s12961-024-01138-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widdig H, Tromp N, Lutwama GW, Jacobs E. The political economy of priority—setting for health in South Sudan: a case study of the health pooled fund. Int J Equity Health. 2022. 10.1186/s12939-022-01665-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walt G, Gilson L. Review article reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994;9(4):353–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Population N, Project, HP. National policy on population for sustainable; 2015.

- 12.Abdulrazak U, Singh R, Ahmad KM. Regional disparities in Nigeria: a spatial analysis. Int J Res Soc Sci Humanit Res. 2016;2(8):19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uneke CJ, Sombie I, Keita N, Lokossou V, Johnson E, Zogo PO. An assessment of maternal, newborn and child health implementation studies in Nigeria: implications for evidence informed policymaking and practice. Tabriz Univ Med Sci. 2016;6(3):119–27. 10.15171/hpp.2016.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.“YSCHMA—Yobe State Contributory Health Care Management Agency.” Accessed: Jun. 03, 2024. https://yschma.yb.gov.ng/

- 15.“YODMA Partners Life Bank Logistics On Drugs Distribution In Yobe—Independent Newspaper Nigeria.” Accessed: Jun. 03, 2024. https://independent.ng/yodma-partners-life-bank-logistics-on-drugs-distribution-in-yobe/

- 16.“Yobe State launches Emergency Medical Ambulance Service—Federal Ministry of Information and National Orientation.” Accessed: Jun. 03, 2024. https://fmino.gov.ng/yobe-state-launches-emergency-medical-ambulance-service/

- 17.Pemerintah, K. “62a696D2D8E2D884253154,” Kompak; 2022.

- 18.Iwu CA, Uwakwe K, Oluoha U, Duru C, Nwaigbo E. Empowering traditional birth attendants as agents of maternal and neonatal immunization uptake in Nigeria: a repeated measures design. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–8. 10.1186/s12889-021-10311-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FMoH, “Technical Guidelines for Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response in Nigeria. Dep. E, Ed. Lilongwe2014. p. 377, pp. 1–439, 2019. https://www.ncdc.gov.ng/themes/common/docs/protocols/4_1476085948.pdf

- 20.“Displacement Hits 1.”

- 21.Ahmadi Q, et al. SWOT analysis of program design and implementation: a case study on the reduction of maternal mortality in Afghanistan. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2016;31(3):247–59. 10.1002/hpm.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Mucio B, Binfa L, Ortiz J, Portela A. Status of national policy on companion of choice at birth in Latin America and the Caribbean: Gaps and challenges. Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan Am J Public Heal. 2020;44:1–6. 10.26633/RPSP.2020.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anyebe EE, Olisah VO, Garba SN, Murtala HH, Danjuma A. Barriers to the provision of community-based mental health services at primary healthcare level in northern Nigeria—a mixed methods study. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2021;15: 100376. 10.1016/j.ijans.2021.100376. [Google Scholar]

- 24.“Jalingo”.

- 25.Sami S, et al. Maternal and child health service delivery in conflict-affected settings: a case study example from Upper Nile and Unity states, South Sudan. Confl Health. 2020;14(1):1–12. 10.1186/s13031-020-00272-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin TK, Werner K, Kak M, Herbst CH. Health-care worker retention in postconflict settings: a systematic literature review. Health Policy Plan. 2023;38(1):109–21. 10.1093/heapol/czac090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sule FA, et al. Examining vulnerability and resilience in maternal, newborn and child health through a gender lens in low-income and middle-income countries: a scoping review. BMJ Glob Heal. 2022;7(4):1–11. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udenigwe O, Okonofua FE, Ntoimo LFC, Yaya S. Seeking maternal health care in rural Nigeria: through the lens of negofeminism. Reprod Health. 2023;20(1):1–12. 10.1186/s12978-023-01647-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramponi F, et al. Demands for intersectoral actions to meet health challenges in east and Southern Africa and methods for their evaluation. Value Heal Reg Issues. 2024;39:74–83. 10.1016/j.vhri.2023.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions, but anonymized transcripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.