Abstract

Background

Approximately 9.9 % of children present with difficulties in language development (DLD), 7.6 % without serious additional impairments and 2.3 % associated with language-relevant comorbidities, e.g., hearing loss. Notably, in a consensus statement by experts in German-speaking countries, in the guideline presented here, and further in this article, all of these disorders are referred to as “developmental language disorders” (DLD), whereas the international consortium CATALISE only refers to those without comorbidities as DLD. DLDs are among the most commonly treated childhood disorders and, if persistent, often reduce educational and socio-economic outcome. Children in their third year of life with developmental language delay (late talkers, LT) are at risk of a later DLD.

Methods

This German interdisciplinary clinical practice guideline reflects current knowledge regarding evidence-based interventions for developmental language delay and disorders. A systematic literature review was conducted on the effectiveness of interventions for DLD

Results

The guideline recommends parent training (Hedges g = 0.38 to 0.82) for LTs with expressive language delay, language therapy (Cohen’s d = –0.20 to 0.90) for LTs with additional receptive language delay or further DLD risk factors, phonological or integrated phonological treatment methods (Cohen’s d = 0.89 to 1.04) for phonological speech sound disorders (SSDs), a motor approach for isolated phonetic SSDs (non-DLD), and for lexical-semantic and morpho-syntactic impairments combinations of implicit and explicit intervention approaches (including input enrichment, modeling techniques, elicitation methods, creation of production opportunities, meta-linguistic-approaches, visualizations; Cohen’s d = 0.89–1.04). Recommendations were also made for DLD associated with pragmatic-communicative impairment, bi-/multilingualism, hearing loss, intellectual disability, autism-spectrum disorders, selective mutism, language-relevant syndromes or multiple disabilities, and for intensive inpatient language rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Early parent- and child-centered speech and language intervention implementing evidence-based intervention approaches, frequency, and settings, combined with educational language support, can improve the effectiveness of management of developmental language delay and disorders.

Approximately 9.9% of children present with difficulties in language development (1), making these among the most common and most frequently treated childhood disorders. Around 9% of all girls and 14.3% of boys insured by Germany‘s largest health insurance company currently receive speech-language therapy, mostly between the ages of 5 and 9 (2). In 7.4–7.6% of such cases, no serious co-occurring impairments are to be expected (1, 3). ICD-10 (F80.-) names such disorders “specific developmental disorders of speech and language” (e1) but ICD-11 (6A01.0) refers to them simply as “developmental speech or language disorders” and (6A01.2) “developmental language disorders” (DLD) (e2). In a further 2.3% of children, problems with language development are associated with comorbidities, such as hearing loss, autism spectrum disorders (ASD), neurological disorders, or intellectual disability (1, 4, 5). In the German guideline presented here (1) and in a consensus statement by experts in German-speaking countries (4), all of the above-named types of non-acquired childhood language disorders are referred to as „developmental language disorders“ (DLD), whereas the international consortium CATALISE only refers to those without comorbidities as DLD (4). DLDs affect one or more linguistic domains expressively, i.e., concerning language production, and/or receptively, i.e., concerning language comprehension: phonological (speech sound production and use), lexical-semantic (vocabulary and word meaning), morpho-syntactic (grammar; structure of sentences and words), and/or communication (pragmatics) (6) (Box 1).

Box. Grammatical (morpho-syntactic) impairment.

The main components of grammar are syntax and morphology. Syntax determines how words are arranged into phrases and sentences, while morphology refers to the internal structure of words. The grammatical functions of words are indicated by noun and verb inflection, i.e., number and case marking or verb conjugation. Symptoms of syntactic impairment include below-average performance in sentence comprehension, limited sentence complexity and variability, reduced length of utterances, omission of obligatory constituents (e.g., omission of subject: “stroke dog”) or function words (e.g., omission of articles: “girl strokes dog”), absence of subordinate clauses, verb placement errors (such as the final verb position in a declarative sentence, “Lisa cake eats”) or rigid sentence structures. Morphological deficits are characterized by inflection errors caused by missing or inappropriate affixes. Examples of morphological errors are violations of subject-verb agreement (“Lisa eat cake”), incorrect formation of participles (“the dog has swimmed”), and errors in gender, number, or case marking.

Intervention focuses on sentence formation with correct word order, especially correct verb placement (i.e., verb-second in German declarative sentences), flexible use of different sentence structures, and the establishment of morphological paradigms, in particular subject-verb agreement and noun inflection (gender, number, case). Implicit methods are used to enrich the input with target structures or to provide feedback by offering recasts and expansions of the child‘s utterances. Explicit methods evoke sentence structures, create production opportunities, or convey syntactic rules through meta-linguistic instructions and visualizations (e.g., symbols for sentence constituents). Both methodological approaches should be combined (Table 1) (14, 27, 30, e32), and interfaces with other linguistic domains (phonological, lexical) need to be considered (e33, e34).

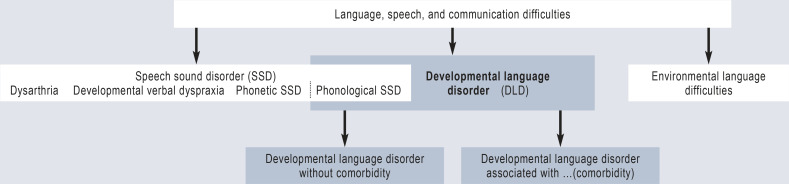

DLD must be distinguished from environmental language difficulties (e.g., German as second language) and some congenital or acquired speech sound disorders (SSD), namely those with impaired cerebral speech motor planning (developmental verbal dyspraxia, childhood apraxia of speech, CAS), speech motor execution control (dysarthria), or impaired articulation (peripheral speech motor disorder or phonetic SSD) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Classification of developmental language disorders and similar language, speech, and communication difficulties (4) in childhood

DLDs often impair children’s social-emotional and cognitive development, social participation, educational outcomes and career opportunities (7–9, e4). Furthermore, DLD is frequently associated with learning, behavioral, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders, motor and coordination deficits, and low self-esteem (10–12).

Symptoms can persist into adulthood (7–12). Forty to 55% of children with DLD have problems later with literacy acquisition, around 40% have learning difficulties (7, 8, 13, e5–e8) as well as a lower level of cognition (p <0.001), lower educational attainment (p = 0.01), and lower occupational status (p <0.0001) than their linguistically well-developed peers (12). A clinical practice guideline on intervention for DLD and late talkers (LT) has been developed in view of the fact that DLDs do not usually resolve without specialist intervention (6, 11) and that language therapy is effective, at least in the short term, according to systematic reviews and meta-analyses (14–16). In Germany they usually start too late, take a long time, and are only occasionally supported by high-quality German studies (17).

Methods

The guideline fulfills all requirements of an S3-guideline (clinical practice guideline) in accordance with the regulations of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) (e9) and involved a multidisciplinary committee of 23 scientific societies/associations and a patient organization (eTable 1). The handling of conflicts of interest was transparent. A systematic literature search and evaluation of the evidence, taking into account DLD/LT-specific criteria, was conducted, and there was a structured, formal consensus process involving two digital voting rounds and five AWMF-moderated consensus conferences.

eTable 1. Professional societies or organizations and elected representatives involved in the guideline: Publishing professional society: German Society of Phoniatrics and Pediatric Audiology, represented by Prof. Dr. med. Katrin Neumann.

| Professional society / organization | Elected representatives |

| Cochlear Implant (Re)Habilitation Working Group (ACIR) | Dipl.-Log. Karen Reichmuth |

| German Association of Paediatric and Adolescent Care Specialists (BVKJ) | Prof. Dr. med. Roland Schmid, Dr. med. Klaus Rodens |

| Professional Association Hearing& Communication (BDH) | Dr. phil. Markus Westerheide |

| Professional Association of German Psychologists, BDP and Department of Clinical Psychology | Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Dipl. Psych. Christiane Kiese-Himmel |

| Alliance of Child and Adolescent Rehabilitation (BKJR) | Dr. med. Monika Schröder |

| German Society of Audiology (DGA) | Prof. Dr. phil. Vanessa Hoffmann |

| German Educational Research Association (GERA | DGfE) | Prof. Dr. phil. Susanne van Minnen |

| German Society of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery (DGHNO-KHC) | Prof. Dr. med. Christopher Bohr |

| German Society of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine (DGKJ) | Dr. med. Cornelia Köhler |

| German Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapie (DGKJP) | Prof. Dr. med. Michele Noterdaeme, Prof. Dr. med. Dipl.-Theol. Christine Freitag |

| German Society of Pediatric Rehabilitation and Prevention (DGPRP) | Dr. med. Julia Hauschild |

| German Society of Phoniatrics and Pediatric Audiology (DGPP) | Prof. Dr. med. Katrin Neumann |

| The German Psychological Society (DGPs) | Prof. Dr. phil. Franz Petermann†, Prof. Dr. phil. Sabine Weinert |

| German Society for Social Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (DGSPJ) | Prof. Dr. med. Andreas Seidel |

| German Society of Special Education for Children with Speech and Language Disorders (dgs) | Prof. Dr. phil. Stephan Sallat |

| German-Speaking Society of Speech, Language, and Voice Pathology (DGSS) | Prof. i. R. Harald A. Euler, PhD,Dr. med. Sabrina Regele |

| German Children‘s Charity | Herr Heino Qualmann |

| German Professional Organization of Phoniatricians and Pediatric Audiologists (DBVPP) | Dr. med. Barbara Arnold, Prof. Dr. med. Christine Schmitz-Salue, Prof. Dr. med. Rainer Schönweiler |

| German Professional Association of Otolaryngologists (BV-HNO) | Dr. med. Joachim Wichmann |

| German Federal Association of Academic Speech/Language Therapy (dbs) | Prof. Dr. phil. Christina Kauschke,Prof. Dr. phil. Volker Maihack |

| German national professional association of Logopedics (dbl) | PD Annette Fox-Boyer, PhD, MSc |

| Society of Interdisciplinary Language Acquisition Research and Developmental Language Disorders in the German-speaking Countries. (GISKID) | Dr. phil. Katharina Albrecht |

| German-Speaking Society of Neuropediatrics (GNP) | Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Lücke |

| German Association for Special Needs Education (vds) | Prof. Dr. phil. Carina Lüke |

| Moderation and counseling | |

| Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) | Prof. Dr. Dr. med. Ina Kopp |

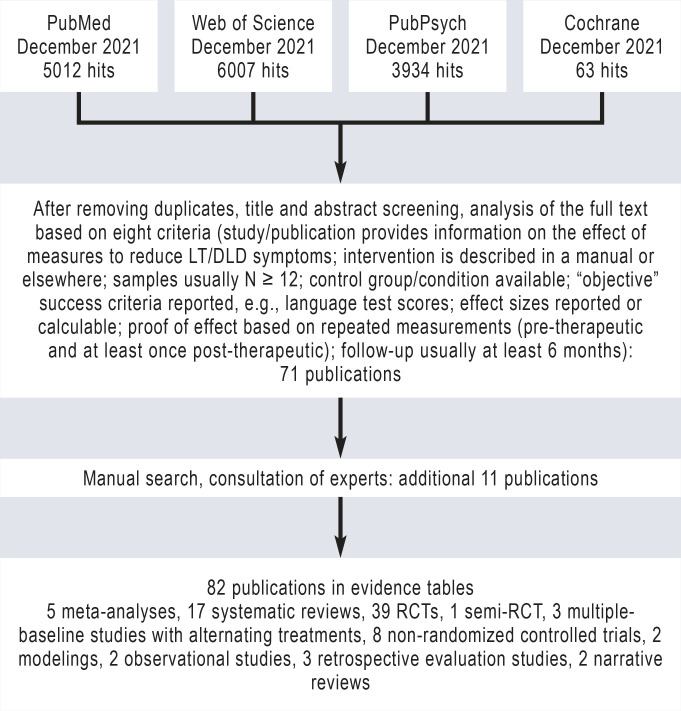

The effectiveness of interventions for DLD and LT was examined in a systematic literature review (Figure 2), for DLD in general and differentiated into its linguistic domains. Furthermore, systematic literature searches were conducted for DLD interventions regarding cases of multilingualism, hearing loss, intellectual disability, ASD, selective mutism, language-related syndromes, and multiple disabilities, as well as for inpatient language rehabilitation and for implementation in educational institutions (17). The guideline recommendations are predominantly based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or systematic reviews and meta-analyses. As effect sizes tend to be overestimated in pre-post intervention comparisons, studies with several months of follow-up were included where possible.

Figure 2.

Systematic literature review (01/1999–12/2021) and selection of LT/DLD interventions (excluding DLD with comorbidities)

N, number of participants; RCT, randomized controlled trial; LT, late talker; DLD, developmental language disorder

Developmental language delay (late talkers)

Developmental language delay affects children without apparent language-related comorbidities whose vocabulary size is in the lower 10% range according to parent questionnaires (e10) or who do not produce word combinations by their 2nd birthday. Prevalence is approximately 15%. The term LT should only be applied to children between their 2nd and 3rd birthdays. In international and German studies, a vocabulary size of fewer than 50 words or the absence of word combinations at 24 months are associated with an increased risk of DLD (e11–e15; for example, 2.5-fold increase in the presence of delayed word combinations; e13). Precisely determining a child‘s vocabulary size using parental questionnaires depends on the number and choice of words presented in the questionnaire; with gender-related results in favor of girls (e16–e21).

If a language delay is detected, for example at the standard pediatric child screening in Germany (U7, at 21–24 months), the child‘s language development shall be monitored within the next 3 months, until the 27th month at the latest, supplemented by further observation and test procedures. A decision is then made as to whether and which interventions are indicated. Early intervention should begin in the third year of life in LTs, because only approximately one third of children catch up by their third birthday, one third develop DLD and another third maintain some language deficits (e22).

In the case of expressive delay (18, 19, e26, e27), parent-based interventions should be provided first, e.g., the structured “Heidelberg Parent-Based Language Intervention” (20, e23–e25). Child-centered early language intervention (18, e26, e28) conducted by speech and language therapists should be offered—potentially combined with parent training (21)—if a) expressive language skills do not clearly improve after parent-based intervention or in the presence of b) additional language comprehension deficits or c) other risk factors (familial disposition for DLD, low parental education level, low nonverbal cognitive abilities of the child). During intervention, language comprehension should be targeted first, followed by language production methods (Table 1). If LTs present with DLD at 3 years of age, further language therapy is required. However, early intervention may reduce the number of subsequent therapy sessions required (e25).

Table 1. Evidence-based intervention techniques and components for late talkers, lexical-semantic and morpho-syntactic impairments (modified after 27).

| Method/Technique | Other terms | Explanation |

|

Implicit methods do not impose any direct demands on the child

and are particularly suitable for initial use with younger children. Learning contexts are enriched and optimized. | ||

| Input enhancement, | Modeling, focused stimulation, input optimization, auditory bombardment | Highly frequent, dense, and concise presentation of target structures (words, grammatical structures) using enhanced input to direct attention to specific target structures, often combined with contrasting two structures |

| (Conversational) recasting | - | Responding to a child’s utterance with feedback techniques such as corrective feedback and expansion |

|

Explicit methods

involve working directly on linguistic target structures. They require the child to consciously engage with language. | ||

| Elicitation techniques | Elicited production, prompting, elicited imitation | Eliciting a specific verbal response; evoking language structures in communication-stimulating interactions; creating opportunities for language production |

| Metalinguistic methods* | Metalinguistic/explicit instruction | Explanation of, and conscious engagement with, language structures and rules, often combined with visualizations |

* not applicable to late talkers

Speech sound disorders

Speech sound disorders (SSDs) are among the most commonly treated developmental abnormalities in children (prevalence: 3.8 to 16%, sex ratio: 3 ♂ : 1 ♀). SSD results in reduced intelligibility of a child’s utterances.

Only phonological disorders are classified as DLDs (Figure 1). Phonological processes (error patterns) are rule-like simplifications or changes of adult speech which are typically observed during speech development. They need to be differentiated diagnostically from atypical phonological error patterns which do not occur during typical speech development. A distinction is also made between functional SSDs and those of organic origin. The following classification is commonly used for functional SSDs: 1. phonological disorder with consistent word realization (DLD): inappropriate phonological pattern usage; delayed error patterns and/or atypical patterns; replacement or omission of sounds, sound combinations, or syllables occurs in a consistent manner; 2. inconsistent phonological disorder (DLD): inability to retrieve the correct sounds in the correct sequence for word production; inability to create automated word production plans for the same word in a consistent manner.

These two subgroups are categorized as DLD, while phonetic disorders (articulation disorders) are not. The latter are articulatory or motor SSD (e.g., distorted /s/ sound-production in the form of an interdental lisp). Phonetic disorders (lisps, lateral <sh> production) do not necessarily require treatment because they do not influence language or literacy development. If treatment is provided, traditional motor-oriented articulation therapy should be offered (Van-Riper approach) (22), with treatment starting regardless of secondary dentition.

Phonological disorders can adversely affect the acquisition of literacy skills (23, e29, e30) and should be treated as early as at the age of three years. For children with delayed phonological patterns, treatment should begin no earlier than six months after the age at which more than 90% of typically developed children have overcome these patterns. Phonological or integrated phonological treatment shall be provided for children with phonological disorders and consistent word production (23–25). An approach such as Core Vocabulary Therapy can be useful for inconsistent word production (e31).

Lexical-semantic impairment

Lexical-semantic impairment is associated with problems in the acquisition, processing, storage (mapping of acoustic [phonological] word form and word meaning [semantics]), retrieval, and/or use of words. Receptive and/or expressive vocabulary and lexical diversity are reduced, and knowledge of word meaning is fragile. Approximately 25% of children with DLD demonstrate word finding or retrieval difficulties.

Vocabulary intervention shall promote word comprehension and production and support children in acquiring words, in broadening their vocabulary, working out the meaning of words, linking words semantically, and facilitating word access. Effective components of vocabulary intervention include:

Basic skills such as understanding symbols and categorizing words into superordinate and subordinate terms, e.g., “animal” as superordinate category of “dog”; “poodle” and “dachshund” as coordinated terms, which are subordinated to “dog”.

Introducing target words selected according to linguistic criteria

Elaborating semantic and phonological word characteristics

Improving the structure of the mental lexicon

The components and methods of vocabulary intervention shall be selected with regard to the child’s individual symptoms. Children shall be given a variety of opportunities to use words, for example during naming games or by associative recall of words that match generic terms, semantic fields, or initial sounds/letters. A variety of methods shall be used (Table 1), combining implicit with explicit methods. Implicit methods (input enhancement with selected target words presented very frequently) do not impose any direct demands on the child; instead, learning contexts are enriched and optimized. Explicit methods (direct reflection on word form and meaning, teaching of strategies for word acquisition, storage, and retrieval) require the child to consciously engage with language. Visualizations and gestures may have a supporting effect on word learning.

Impairment of mainly pragmatic language (social-pragmatic communication disorders)

Children with pragmatic-communicative impairment have deficits in the use of language and nonverbal and paraverbal signs for social purposes, for example in discourse, turn-taking, nonverbal communication, emotion recognition, gestures and facial expressions, linguistic adaptation to different contexts, and/or of coherence and cohesion of narrative content (e35). English-language evidence-based intervention concepts are available for pragmatic-communicative skills in ASD. Intervention focuses on intra- and interpersonal skills in communication behavior/conversation, text processing/production, situational/contextual behavior and the strengthening of basic skills such as sensory, motor, socio-emotional skills, memory, and attention (eTable 1).

Developmental language disorders in bi- and multilingual children

Multilingualism is usually a benefit. It does not cause DLD, nor does it increase the risk of DLD. Multilingual children often demonstrate linguistic peculiarities during language acquisition arising from language interference. These environmental language difficulties must be distinguished by differential diagnosis from DLD, with which they may share a phenomenological resemblance. They do not require treatment; the children need an increase in input and pedagogical support in their surrounding (second) language (6). DLD always affects all the languages spoken by the child, however symptoms are sometimes language-specific (e36). Individualized therapy based on the WHO‘s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), taking into account the linguistic and cultural environment and bio-psycho-social factors, is essential (e37). Where possible, language therapy should also include the child’s first language(s). Such therapy is particularly effective and demonstrates transfer effects to the non-treated language(s). Nevertheless, language interventions in only one language are also effective (31, 32, e38, e39). Therapy methods that have proven effective for monolingual children should also be used for multilingual children, flanked by pedagogical language support if necessary. Language mixing in multilingual families is the rule. Contrary to previous recommendations of the “one-parent-one-language” principle, parents should speak with their child in their preferred language(s) (e40).

Inpatient language rehabilitation

Inpatient language rehabilitation for DLD is practiced specifically in Germany, and its effectiveness has been proven (33, 34, e41). Rehabilitation is indicated if long-term effects on physical and/or mental activities, performance, and participation are to be expected (e42), for example where the success of a prolonged outpatient DLD treatment is limited. Therapy should also focus on language-promoting strategies by the family and include the accompanying parent in the intervention. This recommendation follows a meta-analysis of 59 RCTs and 17 non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs) which demonstrated that parent-implemented intervention strategies in children up to the age of six years effectively improve the language-promoting behavior of parents and the language outcomes of their children (35).

Treatment of developmental language disorders associated with comorbidities

Intellectual disabilities, language-relevant syndromes, and multiple disabilities

Children with DLD and intellectual disabilities, learning difficulties, global developmental delay or language-relevant syndromes should receive early language therapy and support in accordance with the intervention approaches described above. The intervention used should consider the cognitive and general level of the child’s development and be integrated into a comprehensive therapy and support concept within a multi-professional team. A family-centered, individual, multimodal communication approach (e.g., using spoken language, gestures, external communication aids) should be aimed for (35, 36, e43–e48).

People with disabilities require augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) at an early stage if their communication skills and social participation are severely impaired or threatened (e49–e56). AAC distinguishes between unaided forms of communication (facial expressions, gazes, vocalizations, gestures, sign languages and systems …) as well as aided low-tech (non-electronic) forms (communication boards, folders, symbol cards, photos …) and high-tech (electronic) communication aids (buttons, talkers, or tablets with and without voice output …). Interventions (especially “modeling”) that teach the use of the AAC system in speech-language therapy and everyday life, and instruct the closest caregivers, improve communication and language skills (e54, e55). Brain-computer interfaces can provide access to communication for people with severe speech or language and physical disabilities (e56).

Autism spectrum disorders

Early evidence-based therapy and promotion of social communication and language development are central to the treatment of ASD and are set out in a separate S3-guideline (37). Children with ASD and intellectual disability usually present impaired or absent (expressive) language development. With language and communication-promoting interventions, many children develop verbal communication skills preceded by nonverbal communication skills (e52).

Selective mutism

This anxiety disorder manifests itself in consistent, permanent selective inability to speak in certain social situations. Children with selective mutism are unable to speak in the presence of certain individuals or in specific situations, although their underlying ability to speak is unimpaired. The core symptoms occur frequently in association with developmental (e.g., DLD), cognitive (e.g., social anxiety), behavioral (e.g., withdrawal), and emotional (e.g., shyness) symptoms. The main components of behavioral therapy include exposure-based methods to tackle defined anxiety situations, parent-based contingency management, and desensitization. Social skills training, language therapy, and pharmacotherapy may also be necessary (38).

Hearing loss

There is ample evidence that early detection of infant hearing loss through newborn hearing screening, early treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants, and family-centered early intervention have a beneficial effect on the child’s language development and reduce the burden on parents (e57–e62). The quality of parental language input is a key factor. The guideline recommends intervention programs to improve the quality and quantity of language stimulation and parent-child interaction for the age range 0.5–5 years, preferably from the first year of life. From the age of around 2 to 2.5 years, family-centered language therapy is recommended for DLD, in addition to specialist early hearing support. For children aged 3 years and older with persistent specific (e.g., morphological) difficulties, the guideline recommends an approach in which evidence-based language therapy for normal hearing children is adapted to children with hearing loss. This includes work on morpho-syntactic, phonological, semantic-lexical, and narrative skills, supplemented where necessary by training auditory and memory skills with linguistic material. For children with additional impairments, AAC therapy elements are recommended, as well as active music-making in speech-language rehabilitation (39, e63–e83).

Summary of interventions for DLD and LT

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses confirm the clear short-term effectiveness and some long-term effectiveness of speech and language therapy, particularly for children with phonological or expressive vocabulary difficulties, but less so for receptive language difficulties (14, 15, e85). Inconsistent results were found for expressive syntax interventions (14). Group therapy is as effective as individual therapy, interventions by trained parents as effective as those by specialists, and the inclusion of peers with typical linguistic development in therapy is also effective (14). Early interventions, such as parent training and language therapy, can address the risk of LTs developing DLD. Inpatient language rehabilitation should be considered for evident or impending developmental language and communication deficits. Evidence of effectiveness and guideline recommendations for all of the above-mentioned interventions are shown in Table 2 and eTable 2.

Table 2. Effectiveness of interventions available in Germany for developmental language delays/disorders and exemplary evidence.

| Area/disorder | Intervention | Effects, effect sizes*1 | Recommendations*2 |

| Developmental language delay (late talker; LT) | Early interventions in the 3rd year of life to stimulate vocabulary & syntax | g = 2.33 for expressive and 1.42 for receptive language measures, g = 1.54 for mean length of utterance (18, e26I), d = 0.61 for number of different target words as reported by parents (e28, 18) | Should be applied*3 |

| • Parent-centered, e.g., Heidelberg Parent-based Language Intervention | • g = 0.35 for receptive language measures, g = 0.82 for expressive language measure (19); d = 0.72–1.16 expressive language measures pre–post (20); follow-up 2 years: d = 0.68–0.75 (e25) | Shall initially be applied for expressive developmental language delay | |

| • Child-centered (language therapy) | • g = 0.73 for expressive and −0.20 for receptive language (both ns) (e26II, 18); g = 0.61 for number of different words as reported by parents, g = 0.90 for mean length of utterance (e28, 18) | Should be offered where there is a lack of improvement after parent-centered intervention or in cases of receptive deficits or DLD risk factors | |

| • Parent-centered and child-centered in combination | • Indirect proof of effectiveness (18) | May be considered in cases of receptive deficits or DLD risk factors | |

| Developmental language disorder (DLD) in general | Language therapy in general | Effective for children with phonological (SMD = 0.44) and vocabulary difficulties (SMD = 0.89), inconsistent for expressive syntax (SMD = 1.02), less for receptive difficulties (SMD = −0.04) (14) or inconsistent (n.d.) (15, e85) | Children with DLD shall receive evidence-based, disorder-specific, development-oriented, parent- or child-centered language intervention.Therapy shall establish age-appropriate language competence and performance and prevent negative psycho-emotional, social, cognitive, edu- cational, and occupational consequences. Outpatient, day-care, or inpatient treatment settings, individual or group ther-apy, intensive, interval, or extensive treatment forms shall be adapted to in-dividual needs. If the treatment goal is not achieved, multi-dimensional diagnostic assessments should be performed and a treatment plan drawn up based on the bio-psycho-social ICF model. |

| Intervention as group versus individual intervention and clinician-administered versus implemented by trained parents | No difference in effectiveness (SMD = 0.01) (14) | ||

| Inclusion of peers without DLD in therapy | Effective (SMD = 2.29) (14) | ||

| Parent-centered intervention for children up to 6 years of age: training parents to implement language-promoting communication strategies, e.g,, dialogic picture book reading | Children with DLD: major effects for communication, engagement, and language in general (gm 0.82), language reception (gm = 0.92) and expression (gm = 0.83), medium effect for social communication (gm = 0.37) Parents: strong association between parent training and use of language support strategies (gm 0.55) (35)*4 | ||

| DLD: phonological speech sound disorder (SSD) | Early treatment | Age 3.6–5.5 yrs: d = 0.89–1.04 for pre-post language measures, without age effect (24) | Phonological SSDs should be treated from age 3 years. |

| Phonological or integrated phonological intervention, e.g., PhonoSens (23, 24) | Pre-post IG versus CG: % correct consonants: d = 0.89; reduction in phonological error patterns: d = 1.04 (24); follow-up 3–6 yrs: 11.5% spelling disorders in IG, 56% in comparable group, 22% in a large age-matched cohort (23) | A phonological or integrated phonological therapy approach shall be applied for phonological SSDs with consistent word production. | |

| Treatment focused on consistent word production | n.d., core vocabulary therapy is more effective for inconsistent word production than phonological therapy, which is more effective for consistent word production (p = 0.001); follow-up 8 weeks (e31)* 5 | This approach may be considered for phonological SSDs with inconsistent word production. | |

| DLD: lexical-semantic impairment | Vocabulary intervention: | Large effect on vocabulary improvement (g = 0.88); major effect on word learning at ages ≤ 5 yrs. (g = 0.85) and 5–6 yrs. (g = 0.94) (28) | Shall be carried out from the age of 3 and may even be indicated beforehand for LTs |

| Methods in Table 1 | Should exploit variety of methods and shall include word understanding and production as well as create a variety of opportunities to use words | ||

| DLD: grammatical (morpho-syntactic) impairment | Grammatical intervention: | Expressive syntax: d = 0.70, receptive syntax: d = −0.04 (14) | Shall be conducted with specifically selected target structures |

| Focus on sub-areas of grammar Methods in Table 1 | Feedback techniques: short-term mean effect size from 8 individual d’s was 0.96 for proximal and 0.76 for global language measures of grammar development; reflects a positive benefit of approx. 0.75–1.00 SD; long-term mean effect size 0.76, benefit approx. 0.5–1.0 SD (30) | Methods from Table 1 should be used, preferably in combination: initially mainly implicit, later explicit methods | |

| DLD in bi-/multilingual children | Approaches that are effective for monolingual children | Should also be used for multilingual children | |

| Treatment in all the child‘s languages | n.d., vocabulary intervention for bilingual children conducted in the surrounding (second) language only promotes vocabulary development of this language; bilingual intervention promotes both native and second-language vocabulary (31) | First language(s) should be included wherever possible. | |

| Inpatient DLD rehabilitation | Multimodal, intensive, interdisciplinary as block or interval therapy | Inpatient block and interval treatments are (equally) effective for language comprehension (d = 0.89 and d = 0.91, respectively) and expressive vocabulary (d = 0.60 and d = 0.79, resp.) (34)*6 | Should be considered if significant, persistent deficits in language development and verbal communication are present or imminent |

IG, intervention group; CG, control group; NRCT, non-randomized controlled trial; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; DLD, developmental language disorder; LT, late talker; ns, not significant; SMD, standardized mean difference

Footnotes to Table 2:

*1 Effects: intervention groups compared with control groups; effect sizes: n.d. (no details) where data is missing or cannot be calculated from the data provided (17); (mean) Hedges’ g (gm), Cohen’s d, SMD are classified by convention as small (≥ 0.20), moderate (≥ 0.5–0.8), and large (≥ 0.80)

*2 Recommendations (based on strength of evidence or clinical consensus): shall/shall not – strong recommendation, should/should not – recommendation; may/may not be considered – open recommendation

*3 The wording of the guideline has been slightly edited for greater clarity and more consistency.

*4 Meta-analysis (35) rated gm according to weighting above that indicated under *1

*5 Multiple-baseline design with alternating treatments

*6 Retrospective analysis

References:

italics: systematic review; italics and bold: meta-analysis; underlined: RCT

Reference (18): 9 studies, 5 RCTs, 3 NRCTS; including reference (e26I): pre-post 6 months, IG focused stimulation delivered by trained parents, CG delayed-treatment; reference (e26II): IG direct speech-language therapy, CG general cognitive stimulation delivered by trained parents; reference (e28): pre-post 12 weeks, IG clinician-implemented language therapy, CG delayed-treatment

Reference (19): 18 trials, 15 RCTs

Reference (20): pre 3 months after end of intervention, follow-up 12 months (not reported here), IG parent training, delayed-treatment CG; reference (e25): follow-up two years

Reference (14): 25 RCTs

Reference (15): 25 RCTs

Reference (e85): narrative review

Reference (35): 76 studies: 59 RCTs, 17 NRCTs

Reference (24): IG speech-language therapy, CG delayed-treatment; reference (23): follow-up 3–6 years

Reference (e31): multiple-baseline design with alternating treatments

Reference (28): 67 trials, including RCTs

Reference (30): 35 publications for systematic review, 14 trials for meta-analysis

Reference (31): pre-post, 4 parallel groups (IG 1–4)

Reference (34): retrospective analysis

Education

Given that poor language skills in children correlate with lower educational attainment, educational recommendations were also included in the guideline. Besides language therapy, children with DLD need integrated language adaptation in daycare and in school, for example the simplification of linguistic-communicative contexts so that they can understand the teacher, their peers, and the content of the lessons despite their impaired language processing abilities. Furthermore, integrated language therapy and language support should counteract problems in language as well as task and text comprehension in order to improve learning and educational participation in accordance with the bio-psycho-social ICF model (40, e84). Parents and educational professionals should be advised to take children‘s linguistic and communicative limitations into account when planning teaching and learning contexts and educational programs.

Need for action and research

Research on DLD in Germany often does not meet international standards. Individual case studies or small samples and qualitative analyses predominate. Follow-ups are often absent. Only five German RCTs from three working groups were available for the guideline’s systematic review. The guideline confirms the need for therapy research in Germany in order to make therapy procedures, dosages, and settings (e.g., individual versus group therapy, extensive versus intensive therapy or interval therapy) more effective. Although internationally recognized as highly effective, parent training is rarely used and is not regularly reimbursed by health insurance companies; small group therapy for outpatients, online therapy (e127), and the inclusion of linguistically typically developed peers are infrequently employed. Early interventions for LT and DLD are still the exception. Language therapy usually takes place late, at ages five to nine. Treatment practice and remedy guidelines in Germany should therefore be adapted to the current state of knowledge.

Video and audio files are available for this article.

eTable 3. Areas of therapy and support for impairment of mainly pragmatic language (social-pragmatic communication disorders) (modified from 17 and e126).

| Intrapersonal level:Understanding/recognizing | Interpersonal level: Producing/using |

| Communication behavior / conversation management | |

| – Knowledge of conversation and discourse rules – Recognizing turn-taking moments in conversation – Listening behavior – Advanced monitoring of language comprehension – Understanding figurative speech |

– Improving and developing conversation / discourse management – Improving turn-taking skills – Dealing with topic changes and drifting – Repairs / revisions – Using figurative speech |

| Text processing and understanding | |

| Understanding texts / utterances – Understanding presuppositions – Recognizing inferences – Extracting meaning from oral and written texts (coherence / cohesion) |

Producing texts / utterances – Adapting information content (presupposition) – Application of coherence / cohesion – Promoting oral and written narrative skills |

| Situational and contextual behavior | |

| Social interpretation – Understanding nonverbal aspects of communication – Understanding context clues (social context, e.g., social status, expectations; factual context, e.g., space, time, topic) – Understanding other people‘s thoughts and intentions (switching perspective) – Understanding social roles and relationships (e.g., friendships, groups) |

Social interaction – Use of nonverbal communication – Using strategies to improve flexibility – Politeness, consideration, appreciation, and interaction in groups and relationships – Appropriate use of vocabulary |

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all persons and organizations involved in the development of the guideline (eTable 1), and especially Natalja Bolotina, Harald A. Euler, Jessika Melzer, Corinna Gietmann, Philipp Mathmann, Theresa Rieger, and Fabian Burk for their assistance in preparing the evidence tables and the guideline report.

Translated from the original German by the authors, by Ross Parfitt, and by Dr Grahame Larkin

As with many other professional journals, clinical guidelines in the German Medical Journal Deutsches Ärzteblatt are not subject to the peer review process, as S3 guidelines are texts that have already been assessed and discussed many times by experts (peers) and have a broad consensus.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

AFB developed the phonological therapy P.O.P.T. [Psycholinguistically Oriented Phonology Therapy] and is the first author of its publications. She receives royalty and license fees.

CK co-developed the PLAN therapy concept and receives author’s fees from Elsevier.

CKH co-developed the ELAN-R test and received an author‘s fee for this.

KN is senior author of publications on the phonological therapy method PhonoSens. She receives lecture fees from SONOVA Retail, the DGSS (German Society of Speech, Language and Voice-Pathology),the DBVPP (German Professional Organization of Phoniatricians and Pediatric Audiologists), the BVKJ (German Professional Association of Pediatricians), and the EUHA (European University Hospital Alliance).

CL is the First Chairperson of the Association for Interdisciplinary Language Acquisition Research and Childhood Language Disorders in German-speaking Countries.

SS declares that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Norbury CF, Gooch D, Wray C, et al. The impact of nonverbal ability on prevalence and clinical presentation of language disorder: evidence from a population study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57:1247–1257. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waltersbacher A. www.wido.de/fileadmin/Dateien/Dokumente/Publikationen_Produkte/Buchreihen/Heilmittelbericht/wido_ hei_heilmittelbericht_2022_2023.pdf (last accessed on 12 December 2023) Berlin: WIdO - Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK; 2023. Heilmittelbericht 2022/2023. Ergotherapie, Sprachtherapie, Physiotherapie, Podologie. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomblin JB, Records NL, Buckwalter P, Zhang X, Smith E, O’Brien M. Prevalence of specific language impairment in kindergarten children. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1997;40:1245–1260. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4006.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lüke C, Kauschke C, Dohmen A, et al. Definition and terminology of developmental language disorders—interdisciplinary consensus across German-speaking countries. PLoS One. 2023;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293736. e0293736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann K, Arnold B, Baumann A, et al. Neue Terminologie von Sprachentwicklungsstörungen? Monatsschr Kinderh. 2021;169:837–842. [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Langen-Müller U, Kauschke C, Kiese-Himmel C, Neumann K, Noterdaeme M. Diagnostik von (umschriebenen) Sprachentwicklungsstörungen. Eine interdisziplinäre Leitlinie. In: Kiese-Himmel C, editor. Sprachentwicklung - Verlauf, Störung, Diagnostik, Intervention. Vol. 19. Frankfurt/M: Peter Lang; 2012. 27 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aram DM, Ekelman BL, Nation JE. Preschoolers with language disorders: 10 years later. J Speech Hear Res. 1984;27:232–244. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2702.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aram DM, Nation JE. Preschool language disorders and subsequent language and academic difficulties. J Commun Disord. 1980;13:159–170. doi: 10.1016/0021-9924(80)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Botting N. Language, literacy and cognitive skills of young adults with developmental language disorder (DLD) Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2020;55:255–265. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nitin R, Shaw DM, Rocha DB, et al. Association of developmental language disorder with comorbid developmental conditions using algorithmic phenotyping. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.48060. e2248060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsenfeld S, Broen PA, McGue M. A 28-year-follow-up of adults with a history of moderate phonological disorder: linguistic and personality results. J Speech Hear Res. 1992;35:1114–1125. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3505.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenfeld S, Broen PA, McGue M. A 28-year follow-up of adults with a history of moderate phonological disorder: educational and occupational results. J Speech Hear Res. 1994;37:1341–1353. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3706.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McArthur GM, Hogben JH, Edwards VT, Heath SM, Mengler ED. On the „specifics“ of specific reading disability and specific language impairment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:869–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law J, Garrett Z, Nye C. Speech and language therapy interventions for children with primary speech and language delay or disorder. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2003;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004110. CD004110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson HD, Nygren P, Walker M, Panoscha R. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children: systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e298–e319. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartmann E. Wirksamkeit von Kindersprachtherapie im Lichte systematischer Übersichten. Vierteljahresschr Heilpadagog Nachbargeb. 2012;81:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neumann K, Kauschke C, Lüke C, et al. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Phoniatrie und Pädaudiologie (DGPP), editors Therapie von Sprachentwicklungsstörungen. Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie, Version 1.1. www.register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/049-015 (last accessed on 12 December 2023) 2022 AWMF-Registernr. 049-015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cable AL, Domsch C. Systematic review of the literature on the treatment of children with late language emergence. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2011;46:138–154. doi: 10.3109/13682822.2010.487883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts MY, Kaiser AP. The effectiveness of parent-implemented language interventions: a meta-analysis. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2011;20:180–199. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0055). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buschmann A, Jooss B, Rupp A, et al. Parent based language intervention for 2-year-old children with specific expressive language delay: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:110–116. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.141572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVeney SL, Hagaman JL, Bjornsen AL. Parent-implemented versus clinician- directed interventions for late-talking toddlers: a systematic review of the literature. Comm Disord Q. 2017;39:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preston J, Leece M. Articulation interventions. In: Williams A, McLeod S, McCauley R, editors. Interventions for children with speech sound disorders. Baltimore, MD: Brooks; 2021. pp. 526–558. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siemons-Lühring DI, Hesping AE, Euler HA, et al. Spelling proficiency of children with a resolved phonological speech sound disorder treated with an integrated approach-a long-term follow-up randomized controlled trial. Children (Basel) 2023;10 doi: 10.3390/children10071154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siemons-Lühring DI, Euler HA, Mathmann P, Suchan B, Neumann K. The effectiveness of an integrated treatment for functional speech sound disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Children (Basel) 2021;8 doi: 10.3390/children8121190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox-Boyer AV. Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner; 2014. POPT - Psycholinguistisch orientierte Phonologie-Therapie: Therapiehandbuch. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe H, Henry L, Müller LM, Joffe V. Vocabulary intervention for adolescents with language disorder: a systematic review. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2018;53:199–217. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kauschke C, Rath J. Implizite und/oder explizite Methoden in Sprachförderung und Sprachtherapie - was ist effektiv? Forsch Spr. 2017;5:28–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marulis L, Neuman S. The effects of vocabulary intervention on young children´s word learning: a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res. 2010;80:300–335. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motsch HJ, Marks D. Efficacy of the lexicon pirate strategy therapy for improving lexical learning in school-age children: a randomized controlled trial. Child Lang Teach Ther. 2015;31:237–255. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleave PL, Becker SD, Curran MK, Van Horne AJ, Fey ME. The efficacy of recasts in language intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2015;24:237–255. doi: 10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Restrepo MA, Morgan GP, Thompson MS. The efficacy of a vocabulary intervention for dual-language learners with language impairment. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2013;56:748–765. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0173)x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thordardottir E, Cloutier G, Ménard S, Pelland-Blais E, Rvachew S. Monolingual or bilingual intervention for primary language impairment? A randomized control trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2015;58:287–300. doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-13-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fermor C. Effektivität stationärer Sprachtherapie bei Kindern mit Sprachentwicklungsstörungen. Sprachtherapie aktuell: Forschung-Wissen-Transfer: Schwerpunktthema: Intensive Sprachtherapie. 2017;1 e2017-02. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keilmann A, Kiese-Himmel C. Stationäre Sprachtherapie bei Kindern mit schweren spezifischen Sprachentwicklungsstörungen. Laryngo-Rhino-Otol. 2011;90:677–682. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1277209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts MY, Curtis PR, Sone BJ, Hampton LH. Association of parent training with child language development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:671–680. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie e.V. (DGKJP) S2k Praxisleitlinie „Intelligenzminderung“. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/028-042l_S2k_Intelligenzminderung_2021-09.pdf (last accessed on 12 December 2023) [Google Scholar]

- 37.DGKJP; DGPPN et al. Autismus-Spektrum-Störungen im Kindes-, Jugend- und Erwachsenenalter. Teil 2: Therapie. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/028-047l_S3_Autismus-Spektrum-Stoerungen-Kindes-Jugend-Erwachsenenalter-Therapie_2021-04_1.pdf (last accessed on 12 December 2023) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steains SY, Malouff JM, Schutte NS. Efficacy of psychological interventions for selective mutism in children: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Child Care Health Dev. 2021;47:771–781. doi: 10.1111/cch.12895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holzinger D, Dall M, Sanduvete-Chaves S, Saldaña D, Chacón-Moscoso S, Fellinger J. The impact of family environment on language development of children with cochlear implants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ear Hear. 2020;41:1077–1091. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sallat S. Sprache und Kommunikation in Unterricht und Schule - kein exklusives Problem. In: Budnik I, Grummt M, Sallat S, editors. Sonderpädagogik - Rehabilitationspädagogik - Inklusionspädagogik. Hallesche Impulse für Disziplin und Profession. 5. Beiheft Sonderpädagog Förd heute. Weinheim: Beltz-Juventa; 2022. pp. 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- E1.Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM) www.bfarm.de/DE/Kodiersysteme/Klassifikationen/ICD/ICD-10-GM/_node.html (last accessed on 12 December 2023) Berlin: BfArM; 2022. Internationale statistische Klassifikation der Krankheiten und verwandter Gesundheitsprobleme, 10. Revision, German Modification (ICD-10-GM), Version 2023. [Google Scholar]

- E2.World Health Organization. www.icd.who.int/en/ (last accessed on 12 December 2023) Geneva: WHO; 2020. International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (ICD-11), Version 01/2023) [Google Scholar]

- E3.Kauschke C, Lüke C, Dohmen A, et al. Delphi-Studie zur Definition und Terminologie von Sprachentwicklungsstörungen - eine interdisziplinäre Neubestimmung für den deutschsprachigen Raum. Logos. 2023;31:84–102. www.prolog-shop.de/media/pdf/fb/89/a2/ORG-Delphi_online1.pdf?sPartner=Maerz23-7 (last accessed on 12 December 2023) [Google Scholar]

- E4.Kiese-Himmel C, Kruse E. A follow-up report of German kindergarten children and pre-schoolers with expressive developmental language disorders. Logopedics, Phoniatrics, Vocology. 1998;23:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- E5.Catts HW, Fey ME, Tomblin JB, Zhang X. A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45:1142–1157. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/093). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Pennington BF, Bishop DVM. Relations among speech, language, and reading disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:283–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Snowling MJ, Hayiou-Thomas ME, Nash HM, Hulme C. Dyslexia and developmental language disorder: comorbid disorders with distinct effects on reading comprehension. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:672–680. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Snowling MJ, Nash HM, Gooch DC, Hayiou-Thomas ME, Hulme C. Wellcome language and reading project team: developmental outcomes for children at high risk of dyslexia and children with developmental language disorder. Child Dev. 2019;90:e548–e564. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) AWMF-Regelwerk Leitlinien. www.awmf.org/regelwerk/ (last accessed on 6 November 2023) [Google Scholar]

- E10.Fenson L, Marchman VA, Thal D, Dale P, Reznick JS, Bates E. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 2007. MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: user‘s guide and technical manual. [Google Scholar]

- E11.Desmarais C, Sylvestre A, Meyer F, Bairati I, Rouleau N. Systematic review of the literature on characteristics of late-talking toddlers. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2008;43:361–389. doi: 10.1080/13682820701546854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Rescorla L. The Language Development Survey: a screening tool for delayed language in tod-dlers. J Speech Hear Disord. 1989;54:587–599. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5404.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Rudolph JM, Leonard LB. Early language milestones and specific language impairment. Jof Early Interv. 2016;38:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- E14.Sachse S, Buschmann A. Frühe sprachliche Auffälligkeiten und Frühdiagnostik. In: Sachse S, Bockmann AK, Buschmann A, editors. Sprachentwicklung. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2020. pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- E15.Szagun G. Langsam gleich gestört? Variabilität und Normalität im frühen Spracherwerb. Forum Logopädie. 2007;21:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- E16.von Suchodoletz W, Sachse S. Sprachbeurteilung durch Eltern, Kurztest für die U7 (SBE-2-KT), Version vom 17.07.2009. www.ph-heidelberg.de/fileadmin/wp/wp-sachse/SBE-2-KT/SBE-2-KT.pdf (last accessed on 12 December 2023) [Google Scholar]

- E17.Bockmann AK, Kiese-Himmel C. Göttingen: Beltz; 2012. Eltern Antworten - Revision (ELAN-R). Elternfragebogen zur Wortschatzentwicklung im frühen Kindesalter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Grimm H, Doil H. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2000. Elternfragebögen für die Früherkennung von Risikokindern. [Google Scholar]

- E19.Szagun G, Stumper B, Schramm SA. Frankfurt/Main: Pearson; 2009. FRAKIS: Fragebogen zur frühkindlichen Sprachentwicklung. FRAKIS (Standardform). FRAKIS-K (Kurzform) [Google Scholar]

- E20.Deimann P, Kastner-Koller U, Esser G, Hänsch S. TBS-TK-Rezension: FRAKIS Fragebogen zur frühkindlichen Sprachentwicklung. FRAKIS (Standardform) und FRAKIS-K (Kurzform) Psychol Rundsch. 2010;61:169–171. [Google Scholar]

- E21.von Suchodoletz W. Elternfragebögen zur Früherkennung von Sprachentwicklungsstörungen. Handbuch Spracherwerb und Sprachentwicklungsstörungen: Kleinkindphase. In: Sachse S, editor. München: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- E22.Kühn P, v. Suchodoletz W. Ist ein verzögerter Sprachbeginn ein Risiko für Sprachstörungen in Einschulungsalter? Kinderärztliche Praxis. 2009;80:343–348. [Google Scholar]

- E23.Buschmann A. Frühe Sprachförderung bei Late Talkers. Effektivität des Heidelberger Elterntrainings bei rezeptiv-expressiver Sprachentwicklungsverzögerung. Pädiat Prax. 2012;78:377–389. [Google Scholar]

- E24.Buschmann A, Gertje C. Sprachentwicklung von Late Talkers bis ins Schulalter: Langzeiteffekte einer frühen systematischen Elternanleitung. Logos. 2021;29:4–16. [Google Scholar]

- E25.Buschmann A, Multhauf B, Hasselhorn M, Pietz J. Long-term effects of a parent-based language intervention on language outcomes and working memory for late-talking toddlers. J Early Interven. 2015;37:175–189. [Google Scholar]

- E26.Gibbard D. Parental-based intervention with pre-school language-delayed children. Eur J Disord Commun. 1994;29:131–150. doi: 10.3109/13682829409041488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Girolametto L, Pearce PS, Weitzmann E. Interactive focused stimulation for toddlers with expressive vocabulary delays. J Speech Hear Res. 1996;39:1274–1283. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3906.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Robertson SB, Ellis Weismer S. Effects of treatment on linguistic and social skills in toddlers with delayed language development. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1999;42:1234–1248. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4205.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Broomfield J, Dodd B. Clinical effectiveness. In: Dodd B, editor. Differential diagnosis and treatment of children with speech disorder. London: Whurr; 2013. pp. 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- E30.Hayiou-Thomas ME, Carroll JM, Leavett R, Hulme C, Snowling MJ. When does speech sound disorder matter for literacy? The role of disordered speech errors, co-occurring language impairment and family risk of dyslexia. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58:197–205. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Crosbie S, Holm A, Dodd BC. Intervention for children with severe speech disorder: a comparison of two approaches. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2005;40:467–491. doi: 10.1080/13682820500126049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Cirrin FM, Gillam RB. Language intervention practices for school-age children with spoken language disorders: a systematic review. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2008;39:S110–S137. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Tyler AA, Lewis KE, Haskill A, Tolbert LC. Efficacy and cross-domain effects of a morphosyntax and a phonology intervention. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2002;33:52–66. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2002/005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Tyler AA, Lewis KE, Haskill A, Tolbert LC. Outcomes of different speech and language goal attack strategies. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003;46:1077–1094. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/085). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Achhammer B. München: LMU; Förderung pragmatisch-kommunikativer Fähigkeiten bei Kindern: Konzeption und Evaluation einer gruppentherapeutischen Intervention [Dissertation] 2014a. [Google Scholar]

- E36.Chilla S, Rothweiler M, Babur E. München: Reinhardt; 2022. Kindliche Mehrsprachigkeit. Grundlagen - Störungen - Diagnostik. [Google Scholar]

- E37.World Health Organization. www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43737/1/9789241547321_eng.pdf (last accessed on 12 December 2023) Geneva: WHO; 2014. Classification of functioning, disability, and health for children and youth (ICF-CY) [Google Scholar]

- E38.Petersen DB, Thompsen B, Guiberson MM, Spencer TD. Cross-linguistic interactions from second language to first language as the result of individualized narrative language intervention with children with and without language impairment. App Psycholinguist. 2016;37:703–724. [Google Scholar]

- E39.Scharff Rethfeld W. Evidenzen zu Empfehlungen und Ansätzen in der Sprachtherapie mit mehrsprachigen Kindern. Forum Logopädie. 2017;31:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- E40.Lüke C, Ritterfeld U, Biewener A. Impact of family input pattern on bilingual students’ language dominance and language favouritism. German as a foreign language. 2020;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- E41.Dippold S, Wolf-Mühlbauer J, Lässig A, Kainz M-A, Echternach M, Keilmann A. Langzeitverlauf nach stationärer Sprachtherapie: schulische und sprachliche Entwicklung von Kindern mit schwerer spezifischer Sprachentwicklungsstörung (SES) HNO. 2021;69:978–986. doi: 10.1007/s00106-021-01005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft für Rehabilitation e.V. (BAR) Rehabilitation und Teilhabe: Ein Wegweiser. www.bar-frankfurt.de/fileadmin/dateiliste/_publikationen/reha_grundlagen/pdfs/WegweiserHandbuch2020.RZweb.pdf (last accessed on 12 December 2023) 2022 [Google Scholar]

- E43.Seager E, Sampson S, Sin J, Pagnamenta E, Stojanovik V. A systematic review of speech, lan-guage and communication interventions for children with Down syndrome from 0 to 6 years. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2022;57:441–463. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Smith E, Hokstad S, Næss KB. Children with Down syndrome can benefit from language in-terventions; results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Commun Disord. 2020;85 doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2020.105992. 105992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Tamas D, Marcović, Milankov V. Systemic multimodal approach to speech therapy treatment in autistic children. Med Pregl. 2013;66:233–239. doi: 10.2298/mpns1306233t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Tellegen CL, Sanders MR. Stepping stones triple P—positive parenting program for children with disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:1556–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Yoder PJ, Woynaroski T, Fey M, Warren S. Effects of dose frequency of early communication intervention in young children with and without Down syndrome. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;119:17–32. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-119.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Yoder PJ, Woynaroski T, Fey ME, Warren SF, Gardner E. Why dose frequency affects spoken vocabulary in preschoolers with Down syndrome. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;120:302–314. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-120.4.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E49.Langarika-Rocafort A, Mondragon NI, Etxebarrieta GR. A systematic review of research on augmentative and alternative communication interventions for children aged 6-10 in the last decade. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2021;52:899–916. doi: 10.1044/2021_LSHSS-20-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E50.Schlosser R, Lee D. Promoting generalization and maintenance in augmentative and alternative communication: a meta-analysis of 20 years of effectiveness research. Augment Altern Comm. 2000;16:208–226. [Google Scholar]

- E51.Walker VL, Snell ME. Effects of augmentative and alternative communication on challenging behavior: a meta-analysis. Augment Altern Comm. 2013;29:117–131. doi: 10.3109/07434618.2013.785020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E52.Freitag CM, Jensen K, Teufel K, et al. Empirisch untersuchte entwicklungsorientierte und verhaltenstherapeutisch basierte Therapieprogramme zur Verbesserung der Kernsymptome und der Sprachentwicklung bei Klein- und Vorschulkindern mit Autismus-Spektrum-Störungen. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2020;48:224–243. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E53.Leonet O, Orcasitas-Vicandi M, Langarika-Rocafort A, Mondragon NI, Etxebarrieta GR. A systematic review of augmentative and alternative communication interventions for children aged from 0 to 6 years. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2022;53:894–920. doi: 10.1044/2022_LSHSS-21-00191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E54.Biggs EE, Carter EW, Gilson CB. Systematic review of interventions involving aided AAC modeling for children with complex communication needs. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018;123:443–473. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-123.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E55.Romski M, Sevcik RA, Adamson LB, et al. Randomized comparison of augmented and nonaugmented language interventions for toddlers with developmental delays and their parents. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2010;53:350–364. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0156). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E56.Peters B, Eddy B, Galvin-McLaughlin D, Betz G, Oken B, Fried-Oken M. A systematic review of research on augmentative and alternative communication brain-computer interface systems for individuals with disabilities. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.952380. 952380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E57.World Health Organization. www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-hearing (last accessed on 12 December 2023) Geneva: WHO; 2021. World report on hearing. [Google Scholar]

- E58.Moeller MP. Early intervention and language development in children who are deaf and hard of hearing. Pediatrics. 2000;106 doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E59.Moeller MP, Carr G, Seaver L, Stredler-Brown A, Holzinger D. Best practices in family-centered early intervention for children who are deaf or hard of hearing: an international consensus statement. J Deaf Stud Deaf Edu. 2013;18:429–445. doi: 10.1093/deafed/ent034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E60.Neumann K, Euler HA, Chadha S, White KR the International Newborn and Infant Hearing Screening (NIHS) group. A survey on the global status of newborn and infant hearing screening. J Early Hear Detec Intervent. 2020;5:63–84. [Google Scholar]

- E61.Neumann K, Mathmann P, Chadha S, Euler HA, White KR. Newborn hearing screening benefits children, but global disparities persist. J Clin Med. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/jcm11010271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E62.Yoshinaga-Itano C, Manchaiah V, Hunnicutt C. Outcomes of universal newborn screening programs: systematic review. J Clin Med. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/jcm10132784. 2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E63.Ab-Shukor NFA, Lee J, Seo YJ, Han W. Efficacy of music training in hearing aid and cochlear im-plant users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;14:15–28. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E64.Ambrose SE, Walker EA, Unflat-Berry LM, Oleson JJ, Moeller MP. Quantity and quality of caregivers’ linguistic input to 18-month and 3-year-old children who are hard of hearing. Ear Hear. 2015;36(Suppl 1):48–59. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E65.Binos P, Nirgianaki E, Psillas G. How effective is auditory-verbal therapy (AVT) for building language development of children with cochlear implants? A systematic review. Life (Basel) 2021;11 doi: 10.3390/life11030239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E66.Casoojee A, Kanji A, Khoza-Shangase K. Therapeutic approaches to early intervention in au-diology: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;150 doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2021.110918. 110918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E67.DesJardin JL, Doll ER, Stika CJ, et al. Parental support for language development during joint book reading for young children with hearing loss. Commun Disord Q. 2014;35:167–181. doi: 10.1177/1525740113518062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E68.Dettman S, Wall E, Constantinescu G, Dowell R. Communication outcomes for groups of children using cochlear implants enrolled in auditory-verbal, aural-oral, and bilingual-bicultural early intervention programs. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:451–459. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182839650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E69.Fung PC, Chow BW, McBride-Chang C. The impact of a dialogic reading program on deaf and hard-of-hearing kindergarten and early primary school-aged students in Hong Kong. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2005;10:82–95. doi: 10.1093/deafed/eni005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E70.Glanemann R, Reichmuth K, Matulat P, Zehnhoff-Dinnesen AA. Muenster parental programm empowers parents in communicating with their infant with hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:2023–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E71.Kaipa R, Danser ML. Efficacy of auditory-verbal therapy in children with hearing impairment: a systematic review from 1993 to 2015. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;86:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E72.Meinzen-Derr J, Sheldon R, Altaye M, Lane L, Mays L, Wiley S. A technology-assisted language intervention for children who are deaf or hard of hearing: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2021;147 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-025734. e2020025734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E73.Mishra SK, Boddupally SP. Auditory cognitive training for pediatric cochlear implant recipients. Ear Hear. 2018;39:48–59. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E74.Nicastri M, Giallini I, Ruoppolo G, et al. Parent training and communication empowerment of children with cochlear implant. J Early Intervention. 2020;43:117–134. [Google Scholar]

- E75.Rayes H, Al-Malky G, Vickers D. Systematic review of auditory training in pediatric cochlear implant recipients. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019;62:1574–1593. doi: 10.1044/2019_JSLHR-H-18-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E76.Roberts MY. Parent-implemented communication treatment for infants and toddlers with hearing loss: a randomized pilot trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019;62:143–152. doi: 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-18-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E77.Roman S, Rochette F, Triglia JM, Schön D, Bigand E. Auditory training improves auditory per formance in cochlear implanted children. Hear Res. 2016;337:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E78.van Wieringen A, Wouters J. What can we expect of normally developing children implanted at a young age with respect to their auditory, linguistic and cognitive skills? Hear Res. 2015;322:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E79.Wiggin M, Sedey AL, Yoshinaga-Itano C, Mason CA, Gaffney M, Chung W. Frequency of early intervention sessions and vocabulary skills in children with hearing loss. J Clin Med. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/jcm10215025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E80.Yanbay E, Hickson L, Scarinci N, Constantinescu G, Dettman SJ. Language outcomes for children with cochlear implants enrolled in different communication programs. Cochlear Implants Int. 2014;15:121–135. doi: 10.1179/1754762813Y.0000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E81.Yoshinaga-Itano C, Baca RL, Sedey AL. Describing the trajectory of language development in the presence of severe-to-profound hearing loss: a closer look at children with cochlear implants versus hearing aids. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:1268–1274. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181f1ce07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E82.Zamani P, Soleymani Z, Jalaie S, Zarandy MM. The effects of narrative-based language inter-vention (NBLI) on spoken narrative structures in Persian-speaking cochlear implanted children: a prospective randomized control trial. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;112:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E83.Zussino J, Zupan B, Preston R. Speech, language, and literacy outcomes for children with mild to moderate hearing loss: a systematic review. J Commun Disord. 2022;99 doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2022.106248. 106248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E84.Sallat S, Spreer M. www.kita-fachtexte.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Publikationen/KiTaFT_SallatSpreer_2018_wennalltagsintegrierteSprachbildung__01.pdf (last accessed on 12 December 2023) Berlin: Kita Fachtexte; 2018. Wenn alltagsintegrierte Sprachbildung nicht reicht: Kinder mit sprachlichem Förderbedarf in der Kita. [Google Scholar]

- E85.von Suchodoletz W. Wie wirksam ist Sprachtherapie? Kindheit Entwickl. 2009;18:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- E86.Kauschke C, Siegmüller J. Der patholinguistische Ansatz in der Therapie von Sprachentwicklungsstörungen im Überblick. Logos. 2017;24:464–475. [Google Scholar]

- E87.Allen MM. Intervention efficacy and intensity for children with speech sound disorder. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2013;56:865–877. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0076). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E88.Almost D, Rosenbaum P. Effectiveness of speech intervention for phonological disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:319–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E89.Jesus LMT, Martinez J, Santos J, Hall A, Joffe V. Comparing traditional and tablet-based intervention for children with speech sound disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019;62:4045–4061. doi: 10.1044/2019_JSLHR-S-18-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E90.McLeod S, Baker E, McCormack J, et al. Cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of computer-assisted intervention delivered by educators for children with speech sound disorders. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2017;60:1891–1910. doi: 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-S-16-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E91.Lee AS, Gibbon FE. Non-speech oral motor treatment for children with developmental speech sound disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009383.pub2. CD009383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E92.Motsch HJ, Ulrich T. „Wortschatzsammler“ und „Wortschatzfinder“. Effektivität neuer Therapieformate bei lexikalischen Störungen im Vorschulalter. Sprachheilarbeit. 2012;57:70–78. [Google Scholar]

- E93.Ebbels SH, Nicoll H, Clark B, et al. Effectiveness of semantic therapy for word-finding difficulties in pupils with persistent language impairments: a randomized control trial. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2012;47:35–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E94.Gerber S, Brice A, Capone N, Fujiki M, Timler G. Language use in social interactions of school-age children with language impairments: an evidence-based systematic review of treatment. Lang Speech Hear Res. 2012;43:235–249. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0047). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E95.Branson D, Demchak M. The use of augmentative and alternative communication methods with infants and toddlers with disabilities: a research review. Augment Altern Comm. 2009;25:274–286. doi: 10.3109/07434610903384529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E96.Dyer K, Santarcangelo S, Luce SC. Developmental influences in teaching language forms to individual with developmental disabilities. J Speech Hear Disord. 1987;52:335–347. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5204.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E97.Fidler DJ, Philofsky A, Hephurn SL. Language phenotypes and intervention planning: bridging research and practice. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:47–57. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E98.Neil N, Jones EA. Communication intervention for individuals with Down syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Neurorehabil. 2018;21:1–12. doi: 10.1080/17518423.2016.1212947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E99.Burgoyne K, Duff FJ, Clarke PJ, Buckley S, Snowling MJ, Hulme C. Efficacy of a reading and language intervention for children with Down syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:1044–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E100.Moraleda Sepúlveda EM, López-Resa P, Pulido-García N, Delgado-Matute S, Simón-Medina N. Language intervention in Down syndrome: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19106043. 6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]