Abstract

Background:

Combining visual thinking and storytelling makes whiteboard animation an effective educational tool. However, the impact of whiteboard animation is understudied in health science education. This literature review explored the use and impact of whiteboard animation on teaching in health science education.

Method:

A comprehensive electronic literature search was conducted in 5 databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Education Research Complete to identify full-text research articles published in English between 2013 and 2024. Articles were screened to match inclusion criteria, and data were extracted from the eligible studies.

Results:

After 2 rounds of screening, 6 articles were included in the review, all focussing on evaluating the impact of whiteboard animations in dental, medical, and other health science education. All studies reported positive impacts on student satisfaction and knowledge acquisition. A correlation between the number of video views and students’ longitudinal exam performance was also reported.

Discussion and Conclusion:

The concise and engaging animations explaining concepts in a storytelling manner offer an alternative mode of presenting teaching material, reducing extrinsic cognitive loads on the learners. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of this powerful tool on health science education.

Keywords: education, learning, teaching, teaching method, whiteboard animation

Abstract

Contexte :

Les animations sur tableau blanc sont un outil pédagogique efficace, car elles combinent la pensée visuelle et la narration d’histoires. Cependant, on manque d’études sur l’impact de l’animation sur tableau blanc dans l’enseignement des sciences de la santé. Cette analyse documentaire a examiné l’utilisation et l’impact de l’animation sur tableau blanc dans le cadre de l’enseignement des sciences de la santé.

Méthode :

Une recherche documentaire électronique complète a été menée dans 5 bases de données : PubMed, Google Scholar, CINAHL, Web of Science et Education Research Complete dans le but de trouver les articles de recherche en texte intégral publiés en anglais entre 2013 et 2024. Les articles ont été évalués afin de répondre aux critères d’inclusion et les données ont été extraites des études admissibles.

Résultats :

Après 2 cycles de vérifications, 6 articles ont été inclus dans l’examen, tous étant axés sur l’évaluation de l’impact des animations sur tableau blanc dans le cadre de l’enseignement dentaire, médical et d’autres sciences de la santé. Toutes les études ont révélé des effets positifs sur la satisfaction des étudiants et l’acquisition de connaissances. Elles font aussi état d’une corrélation entre le nombre de vidéos visionnées et la réussite des étudiants sur leurs examens longitudinaux.

Discussion et conclusion :

Les animations concises et captivantes qui expliquent des concepts de manière narrative offrent un autre moyen pour présenter du matériel pédagogique, réduisant les charges cognitives extrinsèques sur les apprenants. D’autres études sont nécessaires pour évaluer l’impact de cet outil puissant sur l’enseignement des sciences de la santé.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THIS RESEARCH.

The unique features of whiteboard animation make it a valuable tool for simplifying complex concepts and engaging learners.

The storytelling feature of whiteboard animations can be particularly effective for case presentations and patient education.

INTRODUCTION

Higher educational institutions worldwide are increasingly interested in improving student engagement by incorporating innovative and engaging teaching tools and resources.1-3 Teaching complex scientific concepts in an engaging manner is one of the major challenges educators face.4 Science education delivered solely by lecturing is less effective and a leading cause of loss of interest in science among students at the undergraduate level.5, 6 The rapid development of digital instructional tools has enormous potential for the design and development of engaging and effective teaching resources; whiteboard animation can be one of them.4, 7

Whiteboard animations

Animated videos are a successful pedagogical tool for explaining concepts and engaging students by combining audio messages with changing graphics.4 Animations have a long history in education, impacting learning outcomes.8 A meta-analysis by Höffler and Leutner9 identified a significant impact of animation, compared to static images, on the learning outcomes of undergraduate and high school students. Whiteboard animation is a newly developed branch of animation that is rapidly gaining popularity as an educational tool. Whiteboard animation refers to a specific style of animated videos where the content appears to be hand-drawn on a school whiteboard and narrated, typically in a storytelling manner. This technique uses cartoons and line drawings rather than live videos and realistic images. Hand movement showing the process of creating the line drawings or writing the on-screen text is the signature feature of a whiteboard animation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Screenshot of a whiteboard animation explaining genetics

Some of the signature features of whiteboard animation, including human hand motion, white background, and a line-drawn character, are shown here.

Whiteboard animations have all the benefits of traditional animations: illustrating an abstract idea, simplicity, and engagement. However, the feature that makes whiteboard animations stand out as an educational tool is their ability to combine visual thinking and storytelling.10, 11 Storytelling is a multimodal teaching approach that simultaneously engages listeners’ thinking, emotions, and imagination.12 However, this powerful tool has consistently been understudied and underutilized in higher education, particularly science education.13, 14 Csikar and Stefaniak15 used storytelling in the classroom to teach human anatomy and physiology at the university level in a quasi-experimental study. Results revealed that storytelling was equally effective in conveying complex scientific information as traditional instructional methods.15 Whiteboard animations are powered by storytelling. The short animations include explanatory narratives, which are essential for breaking down the often large concepts illustrated sequentially.11, 16 Depending on the concept being presented, some storytelling in whiteboard animation includes characters, conflicts, quests, and resolutions.11

Tools to create whiteboard animations

The original theme of whiteboard animation—the white background, hand motion, and voice-over—is inspired by the classroom environment. The founding of YouTube in 2005 prompted people to create and share videos of all kinds, including animations.3 The United Parcel Service (UPS) created some of YouTube’s earliest known whiteboard animation videos to explain key concepts to customers.17 The Royal Society for Arts (RSA) is one of the leaders in creating and popularizing modern-day whiteboard animations.17, 18 The first whiteboard animations were manually hand-drawn and filmed over the artist’s shoulder, a tedious technique still in use. However, in recent years, software has been developed to replicate the style, making whiteboard animation more straightforward. Popular web tools for creating whiteboard animations include GoAnimate, VideoScribe, Animaker, PowToon, and Rawshorts.19 Figure 1 shows a screenshot from a simple whiteboard animation created using PowToon.20

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

|

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

|

|

Language |

English |

Non-English |

|

Year of study |

Studies published between 2013 and 2024 |

Studies published before 2013 |

|

Study focus |

Health science education |

Non-health science education |

|

Used for student education |

Used for patient education |

|

|

Tools to improve education |

Tools to improve patient care, clinical practice |

|

|

Studies to assess the impact of whiteboard animation on students’ learning experience |

No assessment was performed Review articles Editorials Perspective articles Full-text not available |

|

|

Study design |

Any |

None |

|

Setting |

Any |

None |

Whiteboard animations as a teaching tool

Visual storytelling with whiteboard animations has enormous potential as a teaching tool. Multiple educational theories support such educational videos. According to Dewey’s pragmatic view of learning, learning is essentially a social activity resulting from human interactions.21, 22 Consistent with this view, studies found that the on-screen appearance of avatars, cartoon characters, dialogues, and simulated real-world settings in animated videos serves an important social function in engaging students.4, 10

Cognitive Load Theory and the principles derived from the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning also support the use of animated videos as a teaching tool. According to the Cognitive Load Theory, individuals hav,e a working memory with a limited capacity that is affected by the underlying nature of the subject matter (intrinsic load) and the way the topic is presented (extrinsic load).23, 24 The intrinsic load cannot be changed for a given subject matter, but the learning process can be eased by changing how the subject is presented (extrinsic load).23, 24 Whiteboard animations offer an alternative learning scaffold; they are expected to reduce the extrinsic load of understanding complex concepts. The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning postulates that receiving information through multiple channels (e.g., auditory and visual) helps students process the information to be moved into long-term memory more effectively by integrating the new knowledge with their existing knowledge.25, 26 In support of this theory, in a study, participants identified animated videos as “a refreshing change from conventional teaching,” suggesting reduced extrinsic load by the alternative presentation method.4

The success of a teaching technology is often guided by Keller’s Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction (ARCS) model.27 The characters, storytelling, and pictures used in whiteboard animations aim to gain viewers’ attention through perceptual arousal, inquiry arousal, and variability.27, 28 The study by Liu and Elms4 revealed that animated teaching videos enhanced students’ learning experience by improving their self-assessed understanding of the materials, indicating enhanced confidence. The animated videos are often made accessible to students outside the classroom, facilitating flexible and self-paced learning and thus increasing student satisfaction.4

Whiteboard animations have a positive effect on retention, engagement, and enjoyment. Li et al.29 studied the effectiveness of whiteboard animation for educational purposes at a university in Hong Kong. Educational videos made with whiteboard animation techniques were offered to the students as a part of a general education course. The results of the study showed that students who watched the animations before class achieved better grades than those who did not. Over 92% of students found the whiteboard animations helpful in imparting knowledge and clarifying concepts.29 In another study, general adult populations selected as study participants were randomly distributed to 1 of 4 instructional conditions: whiteboard animation, electronic slideshow (sequential images with narration), audio-only, and text-only, to learn concepts of physics. The study reported that whiteboard animations had a better impact on retention, engagement, and enjoyment than other instructional media.8

Objective of the review

Despite the potential and positive impact of whiteboard animations, their application in health science education is scarce. This narrative review aims to explore the current literature to identify the application of whiteboard animation as a teaching tool in health science education. It aims to answer the following questions:

What is the nature of whiteboard animations developed or used for teaching purposes in health science education?

How do whiteboard animations impact students’ learning experiences in health science education?

METHODS

A comprehensive electronic literature search was conducted in 5 databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Education Research Complete using the search terms “Whiteboard animation” AND “Health science education.” Full-text, non-duplicate articles published in English between 2013 and 2024 were included. Articles were excluded if they were published in a language other than English, were not available in full-text form, did not include faculty or students from health science education, or did not conduct an evaluation to assess the impact of the whiteboard animation. Review studies, editorials, and perspective articles were also excluded. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of this review are summarized in Table 1.

Two rounds of review were carried out to screen the articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The first screening was conducted by title and abstract. A full-text review was conducted in the second round, followed by data extraction. Data were extracted from the eligible studies related to the year of publication, source, and topic of the whiteboard animation used for intervention, study participants, evaluation method, and the evaluation outcome.

RESULTS

Features of the reviewed studies

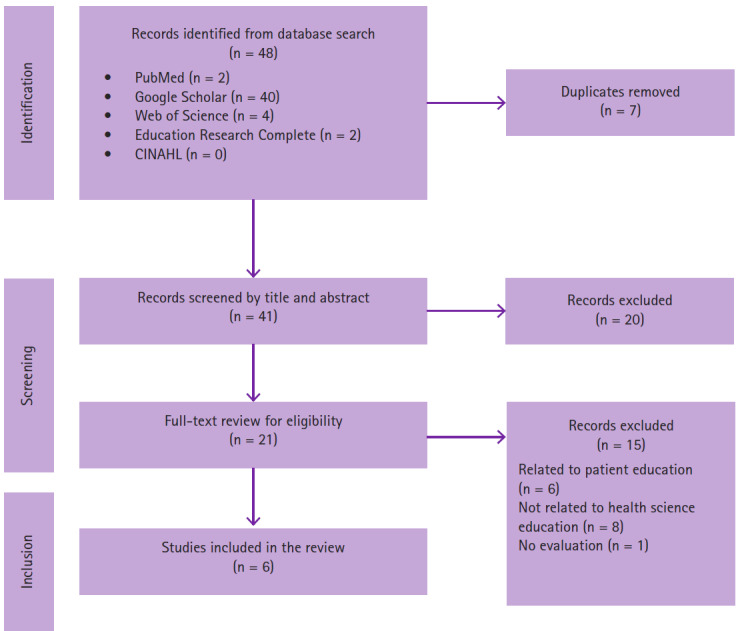

The initial search identified 48 articles. After 2 rounds of screening, 6 articles were included in this review (Figure 2).30-32, 34-36 Studies were published between 2016 and 2023 in Canada (n = 2) and the United States (n = 4). Study participants were from medical schools (4 studies), a dental school (1 study), and university health professional, biomedical or science-related programs (1 study).

Nature and source of the whiteboard animations

Several institutions used whiteboard animations to explain scientific concepts, ranging from simple (basic science) to complex (empiric antibiotic selection, biofilm formation by bacteria) (Table 2). Three studies used whiteboard animations commercially available from Osmosis (www.osmosis.org) as supplementary learning materials for dental and medical students.30-32 Osmosis is a web-based collaborative learning platform for medical students that provides open access to a series of whiteboard animations and self-assessment questions.33

In contrast, 3 studies used author-created whiteboard animations as teaching tools.34-36 McGuinness35 created whiteboard animations by hand-drawing the images on a whiteboard and filming the drawing process.35 Larnard et al.36 used screen capture and video editing software to create whiteboard animations for students.

Figure 2.

Study selection process

Impact of whiteboard animations on students’ learning experiences

The included studies conducted quantitative research to evaluate the impact of whiteboard animations on student satisfaction, engagement, and knowledge acquisition (Table 2). Zheng et al.32 evaluated dental students’ perceptions, video-watching patterns, and the correlation between video-watching and exam performance. The whiteboard animations from Osmosis were well received by students. Most study participants reported those videos as valuable for their learning. The results also revealed a positive correlation between the number of video views and students’ longitudinal exam performance in 2 content areas: biochemistry and nutrition.32 Whiteboard animations from Osmosis were also perceived as beneficial and preferred over traditional lectures by medical students.30 However, in a campus-wide study, Hudder et al.31 reported that only 50% of medical students signed up for an account on the Osmosis platform when it was made available to them. The findings of the study revealed a positive experience for students with learning resources on Osmosis; it also identified medical students’ lack of time as a barrier to adopting this platform.31

Larnard et al.36 invited participants to complete a survey and knowledge test before and after watching a whiteboard animation video on empiric antibiotic selection.36 All study participants (100%) agreed or strongly agreed that the whiteboard animated videos were an effective way to learn the material. A significant improvement in test scores was reported in the knowledge test after watching the video.36 A similar approach by Thomson et al.34 showed a significant increase in the test scores of the study participants after watching a whiteboard animation on infertility.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of members participating in personal interviews

|

Author, Year of Publication, Country |

Source of the whiteboard animation video |

Video topics |

Study participants |

Evaluation method |

Impact of the whiteboard animations on students’ learning |

|

Zheng et al. (2023)32 Canada |

A series of commercial whiteboard animation videos created by “Osmosis” was made available to students. |

Multiple topics related to basic science concepts |

Students in the Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) program (n = 143) |

The authors used surveys, platform analytics, and exam scores to evaluate student perceptions, video-watching patterns, and the correlation between video-watching and exam performance. |

The whiteboard animations were well received by students. Most study participants reported the videos as valuable for their learning. Regression analyses revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between the number of video views and students’ longitudinal exam performance in biochemistry and nutrition. |

|

Thomson et al. (2016)34 Canada |

The authors created a 15-minute whiteboard animation video with assistance from Information Technology Services at the university. |

Infertility |

First- and second-year medical students (n = 101) |

A questionnaire was used for knowledge assessment before and after watching the whiteboard animation video. |

Students showed a significant increase in their scores after watching the video. Female respondents had a greater increase in mean score after watching the video than male respondents. |

|

McGuinness (2020)35 United States |

The author created a video by hand drawing on a whiteboard and filming that drawing process. |

Biofilm formation by bacteria |

Students of health professional, biomedical, or science-related fields (n = 500) |

A survey was conducted to assess participants’ opinions on the comparative impact between whiteboard and 3D animations. |

58% of participants responded that the whiteboard animation was easier to understand than the 3D animations. |

|

Larnard et al. (2020)36 United States |

The authors created a video using Show Me, Screen Capture, and Camtasia |

Empiric antibiotic selection |

Fourth-year medical students (n = 37) |

Surveys and knowledge assessments were conducted before and after watching the video. |

Significant improvement was found in the knowledge test after watching the video. All participants agreed or strongly agreed that whiteboard animations as a supplementary module were an effective way to learn the material. |

|

Hudder et al. (2019)31 United States |

A series of commercial whiteboard animation videos created by “Osmosis” was made available to students. |

Multiple topics related to basic science concepts |

First- and second-year medical students (n = 1135) |

Engagement metrics were tracked for the 2016–2017 academic year within the Osmosis platform for all students who created an account across the 3 campuses of the institution. |

The adoption of the Osmosis platform varied among medical students. 50% of students signed up for an account on the Osmosis platform. Although use of the platform across campuses was uneven, it was most significant when there was overt support by faculty. |

|

Tackett et al. (2021)30 United States |

A series of commercial whiteboard animation videos created by “Osmosis” was made available to students. |

Cardiovascular systems |

First-year medical students (n = 232) |

Survey |

Most students found whiteboard animation videos helpful for learning and preferred these videos to traditional lectures. |

According to a study conducted by McGuinness,35 whiteboard animations are effective in explaining complicated ideas. The study focussed on students’ preferences in understanding biofilm formation by bacteria through either whiteboard or 3D animation. The majority of the participants reported that whiteboard animation was easier to comprehend than 3D animation.35

DISCUSSION

This review investigated th,e current literature on the use and impact of whiteboard animations as a teaching tool in health science education. It includes a small number of studies, and though many other studies of animated videos aiming to explain health or disease-related topics were found, those videos were either developed for patient education or were not evaluated for their impact or effectiveness. Although research on whiteboard animations in health science education is scarce, their positive effect on students’ learning experiences is evident from the findings of the study.

Half of the studies included in this review used commercially available whiteboard animation videos created by Osmosis; others created their own animations to explain specific topics. Although the sample size for all the studies was large, the evaluations focussed on knowledge acquisition and satisfaction only. Qualitative studies and studies exploring student motivation are largely absent. Another weakness of the studies included in this review is the absence of theory-driven application and evaluation of whiteboard animations as an educational tool.

Although traditional animations have a long history in education, few studies have focussed on whiteboard animations.8, 37 This review identifies limited research and potential for future endeavours in establishing whiteboard animation as a teaching tool in health science education. Visual storytelling is the most appealing and unique feature of whiteboard animation. Studies found the successful application of storytelling in conveying complex scientific information.15 Along these lines, more research is needed on the impact of whiteboard animations in higher education, focussing on their ability to explain complex scientific concepts to reduce extrinsic cognitive loads.

A study exploring the aspects of animation design that enhance student engagement found that character design, dialogues, and voice acting contribute the most towards students’ interest, enjoyment, and engagement.4 Whiteboard animation uses line-drawn characters, narrative voice-over, storytelling, and human hand-motion. It is crucial to investigate which components of whiteboard animations contribute to enhancing student engagement.

Animated educational videos can impact students differently depending on their demography. Liu & Elms4 reported that, although all study participants, regardless of gender and age, found animations useful for their learning, female and younger students said that animations made learning more enjoyable. To male students, animations were more valuable in simplifying complex technical concepts.4 The same study also found that older students appreciated the flexibility offered by the animated videos for self-directed learning.4 Evaluating the pedagogical value of whiteboard animations for diverse learners is another potential research area.

The characters, narratives, tones, and humour used in whiteboard animations can be tailored easily for target learners and audiences, which makes this tool particularly valuable for adult education. Adults learn differently from children. Adult learning theories suggest that adults are goal and relevancy oriented, intrinsically motivated, and self-directed.38, 39 Educational videos using the whiteboard animation technique can be effective for adult education, providing self-directed, flexible, and relevant learning options. Investigating the impact of whiteboard animations on adult learning is also an area of potential future research.

Though the majority of the studies in the current review do not incorporate the theoretical underpinnings of the reasons whiteboard animations are effective in education, many educational theories may explain why students thrive when using this technology. Narrative learning theory suggests that the storytelling in whiteboard animation videos can engage the learner at multiple levels, including cognitive, emotional, and cultural. This creates a dimensional, integrated learning experience that allows them to reconstruct that knowledge into something that is meaningful to them as an individual.40 This constructivist approach to learning helps learners think critically about the material they are learning and integrate it into their existing knowledge, belief system, and culture.

The storytelling component of whiteboard animation videos also lends itself to Indigenous ways of knowing and knowledge mobilization. These videos can be used to teach in a way that is consistent with Indigenous values and traditions, such as the development of skills through observation.41, 42 The use of whiteboard animation videos has been shown to help to overcome knowledge mobilization barriers in Indigenous communities and can improve knowledge translation, particularly when compared with conventional knowledge translation outputs such as manuscripts, which are often difficult to access and understand outside of the academic community.43

The multimedia aspect of whiteboard animation videos may also explain why they are more effective as a learning tool when compared with conventional means. The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning postulates that receiving information through both auditory and visual channels (known as dual coding) facilitates the transfer of information from working memory into long-term memory.26 This theory may explain why the Larnard et al.36 and Thomson et al.34 studies found improved test scores following teaching with whiteboard animation videos.

Many digital technologies, such as whiteboard animation videos, can also be used to support equity, diversity, and inclusion in the classroom and beyond. The Universal Design for Learning framework strives to make education equitable and accessible by following 3 principles: 1) engagement; 2) representation; and 3) action and expression.44 This inclusive pedagogical approach is captured by whiteboard animations as the dynamic, multisensory nature of the videos allows students to modify the speed of the videos, replay them, or enable closed captioning. Representation of distinct cultures, genders, and abilities is also readily facilitated by this technology.

One of the major drawbacks of using whiteboard animation videos for education is that creating even short videos can take a significant amount of time and resources. However, with the recent popularization of artificial intelligence (AI), the production of whiteboard animation videos is becoming more streamlined and requires less technical expertise. A number of AI-assisted free or paid online whiteboard animation tools are readily available, including Canva45, Mango Animate: Mango AI46, and Powtoon Imagine47. AI-based text-generation tools can also be used to create scripts for whiteboard animations.

CONCLUSION

The unique features of whiteboard animation make it a valuable tool for simplifying complex concepts and engaging learners. The application of whiteboard animations is rapidly growing in health science education. Multiple applications of animated educational videos made using the whiteboard animation technique are reported. Besides traditional classroom teaching, the storytelling feature of whiteboard animations can be particularly effective for case presentations and patient education. Further research is needed to carefully evaluate the impact of this powerful tool in improving learning experiences in health science education.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors of this study have declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

CDHA Research Agenda category: capacity building of the profession

References

- Azer SA , Sarah A 3D anatomy models and impact on learning: A review of the quality of the literature Health Professions Education 2016 ; 2 ( 2 ): 80 – 98 [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK , Kim SM , Khera O , Getman J The experience of three flipped classrooms in an urban university: An exploration of design principles The Internet and Higher Education 2014 ; 22 : 37 – 50 [Google Scholar]

- Tan E , Pearce N Open education videos in the classroom: Exploring the opportunities and barriers to the use of YouTube in teaching introductory sociology Research in Learning Technology 2011 ; 19 [Google Scholar]

- Liu C , Elms P Animating student engagement: The impacts of cartoon instructional videos on learning experience Research in Learning Technology 2019 ; 27 [Google Scholar]

- Wood WB Innovations in teaching undergraduate biology and why we need them Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2009 ; 25 : 93 – 112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour E, Hunter AB, Weston TJ. Why we are still talking about leaving. In: Seymour E, Hunter AB, editors. Talking about leaving revisited: Persistence, relocation, and loss in undergraduate STEM education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2019. pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Voithofer R Designing new media education research: The materiality of data, representation, and dissemination Educational Researcher 2005 ; 34 ( 9 ): 3 – 14 [Google Scholar]

- Türkay S The effects of whiteboard animations on retention and subjective experiences when learning advanced physics topics Computers & Education 2016 ; 98 : 102 – 114 [Google Scholar]

- Höffler TN , Leutner D Instructional animation versus static pictures: a meta-analysis Learning and Instruction 2007 ; 17 ( 6 ): 722 – 738 [Google Scholar]

- Adams C , Yin Y , Vargas Madriz LF , Mullen CS A phenomenology of learning large: The tutorial sphere of xMOOC video lectures Distance Education 2014 ; 35 ( 2 ): 202 – 216 [Google Scholar]

- Forno S. How Whiteboard Animation Changed Online Video [website]. ©2017 [cited 2024 Jan 23]. Available from: https://idearocketanimation.com/15321-whiteboard-animation-history/

- Crocetti G , Barr B Teaching science concepts through story: Scientific literacy is more about the journey than the destination Literacy Learning: The Middle Years 2020 ; 28 ( 3 ): 44 – 52 [Google Scholar]

- Kokkotas P , Rizaki A , Malamitsa K Storytelling as a strategy for understanding concepts of electricity and electromagnetism Interchange 2010 ; 41 : 379 – 405 [Google Scholar]

- Krupa JJ Scientific method & evolutionary theory elucidated by the ivory-billed woodpecker story The American Biology Teacher 2014 ; 76 ( 3 ): 160 – 170 [Google Scholar]

- Csikar E , Stefaniak JE The utility of storytelling strategies in the biology classroom Contemporary Educational Technology 2018 ; 9 ( 1 ): 42 – 60 [Google Scholar]

- Tversky B, Heiser J, Mackenzie R, Lozano S, Morrison J. Enriching animations. In Lowe R, Schnotz W, editors. Learning with animation: Research implications for design. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 263–85. [Google Scholar]

- Next Day Animations. A Brief History of Whiteboard Animation [website]. ©2017 [cited 2024 Jan 23]. Available from: https://nextdayanimations.com/brief-history-whiteboard-animation/

- The RSA. We Unite People and Ideas [website]. ©2023 [cited 2024 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.thersa.org/

- Kharbach M. 5 Powerful Tools To Create Educational Whiteboard Animation Videos [website]. ©2017 [cited 2024 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.educatorstechnology.com/2017/06/powerfultools-to-create-educational.html

- POWTOON. The visual communication platform. [website]. London; 2023 [cited 2024, Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.powtoon.com/?locale=en

- Feinberg W , Torres CA Democracy and education: John Dewey and Paulo Freire Educational Practice and Theory 2001 ; 23 ( 1 ): 25 – 37 [Google Scholar]

- Kivinen O, Piiroinen T, Saikkonen L Two viewpoints on the challenges of ICT in education: Knowledge-building theory vs. a pragmatist conception of learning in social action Oxford Review of Education 2016;42(4):377–390 [Google Scholar]

- Sweller J Cognitive load theory and educational technology Educational Technology Research & Development 2020 ; 68 ( 1 ): 1 – 16 [Google Scholar]

- Van Merriënboer JJ , Sweller J Cognitive load theory in health professional education: design principles and strategies Med Educ 2010 ; 44 ( 1 ): 85 – 93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer RE. Multimedia learning. In: Psychology of learning and motivation, Vol 41. Ross BH, editor. Amsterdam: Elsevier BV; 2002. pp. 85–139. [Google Scholar]

- Yue C , Kim J , Ogawa R , Stark E , Kim S Applying the cognitive theory of multimedia learning: an analysis of medical animations Med Educ 2013 ; 47 ( 4 ): 375 – 387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JM. Motivational design research and development. In: Motivational design for learning and performance. New York (NY); Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Milman NB , Wessmiller J Motivating the online learner using Keller’s ARCS model Distance Learning 2016 ; 13 ( 2 ): 67 [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Lai CW, Szeto WM. Whiteboard animations for flipped classrooms in a common core science general education course. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Higher Education Advances, June 25–28, 2019, Valencia, Spain. Valencia, Spain: Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València; 2019. pp. 929–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tackett S , Green D , Dyal M , O’Keefe E , Thomas TE , Nguyen T , et al. Use of commercially produced medical education videos in a cardiovascular curriculum: multiple cohort study JMIR Medical Education 2021 ; 7 ( 4 ): e27441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudder A , Tackett S , Moscatello K First-year experience implementing an adaptive learning platform for first- and second-year medical students at the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine J Am Osteopath Assoc 2019 ; 119 ( 1 ): 51 – 58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Cuenin K, Lyon C, Bender D An exploratory study of dental students’ use of whiteboard animated videos as supplementary learning resources in basic sciences. 2023 TechTrends. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes MR , Gaglani SM , Wilcox MV , Mitchell T , DeLeon V , Goldberg H Learning through Osmosis: a collaborative platform for medical education Innov Global Med Health Educ 2014 ; 2 [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AA , Brown M , Zhang S , Stern E , Hahn PM , Reid RL Evaluating acquisition of knowledge about infertility using a whiteboard video J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2016 ; 38 ( 7 ): 646 – 650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness S. Comparing whiteboard and 3D animation in visualization of neuron-like bacterial communication in biofilms [doctoral dissertation]. Chicago (IL): University of Illinois at Chicago; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Larnard J , Zucker J , Gordon R The stairway to antibiotic heaven: a scaffolded video series on empiric antibiotic selection for fourth-year medical students MedEdPORTAL 2020 ; 16 : 11036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plass JL , Heidig S , Hayward EO , Homer BD , Um E Emotional design in multimedia learning: Effects of shape and color on affect and learning Learning and Instruction 2014 ; 29 : 128 – 40 [Google Scholar]

- Knowles MS, Holton EF, III, Swanson RA. The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development, 8th Ed. Oxon (UK): Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karge BD , Phillips KM , Jessee T , McCabe M Effective strategies for engaging adult learners Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC) 2011 ; 8 ( 12 ): 53 – 56 [Google Scholar]

- Clark MC, Rossiter M. Narrative learning in the adult classroom. Proceedings of the Adult Education Research Conference, St. Louis, Missouri, 2008. Available from: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2008/papers/13 [Google Scholar]

- Latycheva O , Chera R , Hampson C , Masuda JR , Stewart M , Elliott SJ , Fenton NE Engaging First Nation and Inuit communities in asthma management and control: Assessing cultural appropriateness of educational resources Rural and Remote Health 2013 ; 13 ( 2 ): 1 – 11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smylie J , Kaplan-Myrth N , McShane K , Métis Nation of Ontario–OttawaCouncil , Pikwakanagan First Nation , Tungasuvvingat Inuit Family Resource Centre Indigenous knowledge translation: Baseline findings in a qualitative study of the pathways of health knowledge in three Indigenous communities in Canada Health Promotion Practice 2009 ; 10 ( 3 ): 436 – 446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford LE , Bharadwaj LA Whiteboard animation for knowledge mobilization: A test case from the Slave River and Delta, Canada Int J Circumpolar Health 2015 ; 74 ( 1 ): 28780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose DH, Meyer A. Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria (VA): Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Canva. Free Online AI Image Generator [website]. ©2024 [cited 2024 April 10]. Available from: www.canva.com/ai-image-generator/

- Mango Animate. Mango AI [website]. ©2024 [cited 2024 April 10]. Available from: https://mangoanimate.com/

- Powtoon imagine. Elevate Your L&D with AI-Powered Video [website]. ©2024 [cited 2024 April 10]. Available from: www.powtoon.com/imagine/powtoon-ai