Dear Editor,

We read with great interest the systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Crane et al. [1], which investigated the global prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This study introduced a novel etiologic classification, emphasizing the role of MAFLD in HCC within the context of multiple interacting liver diseases.

MAFLD, previously known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, has demonstrated an increasing incidence in Asia [2], where chronic hepatitis and alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) are also prevalent [3,4]. The interaction of different etiologies may veil the impact of MAFLD on the development of HCC; therefore, analyzing the etiological distribution of HCC is essential.

Inspired by Crane et al. [1], we conducted a multicenter cohort study by recruiting 2,831 patients newly diagnosed with HCC between 2018 and 2023. Patients with MAFLD were diagnosed based on the criteria outlined in an international expert consensus statement [5]. Hepatic steatosis was detected using imaging and/or liver histology.

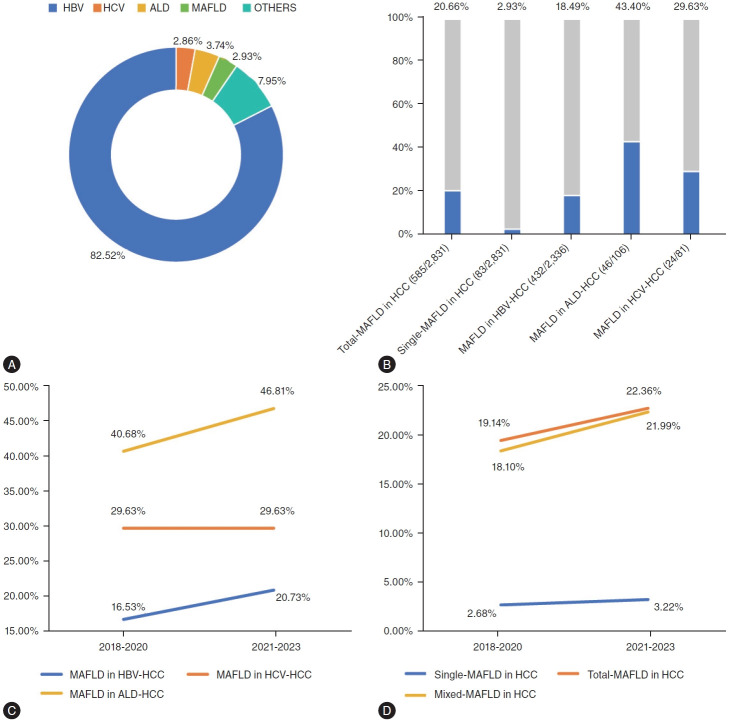

In our study, the prevalence of total-MAFLD was 20.66% (585/2,831), with single and mixed-MAFLD being 2.93% (83/2,831) and 17.73% (502/2,831), respectively. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) was the leading cause of HCC (82.52%, 2,336/2,831 patients). Additionally, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and ALD accounted for 2.86% (81/2,831) and 3.74% (106/2,831) cases of HCC, respectively. The rate of other causes, including autoimmune liver disease and cryptogenic HCC, was 7.95% (225/2,831) (Fig. 1A). A total of 585 (20.66%) patients were identified as having MAFLD associated with HCC (Fig. 1B). Among the cases of mixed-MAFLD HCC, MAFLD was present in 18.49% (432/2,336) of HBV-related HCC cases, 29.63% (24/81) of HCV-related HCC cases, and 43.40% (46/106) of ALD-related HCC cases. Compared to the patients with HCC diagnosed during 2018–2020, the percentage of MAFLD in ALD-related HCC demonstrated the greatest increase among the population with mixed-MAFLD HCC during 2021–2023 (Fig. 1C). The proportion of cases with mixed HCC increased by 3.89% within the past few years, while patients with HCC attributable to single-MAFLD exhibited a stable curve, with a slight increase of 0.54% (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

(A) Etiology distribution of HCC. (B) Proportion of MAFLD in different subgroups during 2018–2023. (C) Proportions of MAFLD in HBV, HCV, and ALD-related HCC. (D) Proportions of single-MAFLD, mixed-MAFLD and total-MAFLD in HCC. MAFLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease.

Compared to patients with non-MAFLD HCC, those with single-MAFLD HCC were older (58 vs. 68 years, P<0.001), had a lower proportion of men (83.66% vs. 69.88%, P=0.001), and were less likely to have cirrhosis (52.98% vs. 28.92%, P<0.001). Similarly, in comparison to patients with mixed-MAFLD HCC, those with single-MAFLD HCC were older (58 vs. 68 years, P<0.001), had fewer men (86.65% vs. 69.88%, P<0.001), and were less likely to have cirrhosis (54.18% vs. 28.92%, P<0.001). However, compared to the non-MAFLD HCC group, patients in the mixed-MAFLD HCC group were less likely to experience metastases (1.69% vs. 0.40%, P=0.029), had a lower likelihood of having multiple tumors (14.05% vs. 9.98%, P=0.019), and had a shorter maximum tumor diameter (4.00 vs. 3.50 cm, P=0.037). Compared to patients with HCC without MAFLD, the concentrations of alpha-fetoprotein in single-MAFLD and mixed-MAFLD HCC populations were significantly lower (30.60 vs. 5.50 ng/mL, P<0.001; 30.60 vs. 13.00 ng/mL, P<0.001). No significant differences were observed in the proportion of nerve or lymph node invasion, portal vein tumor thrombus, or platelet count among the three groups (Supplementary Table 1).

Our study discovered that the proportion of MAFLD in the entire HCC population was 20.66%, which was relatively low compared to the global prevalence of 48.7% outlined in Crane’s research. Notably, in subgroup analysis categorized by geographical settings, Crane et al. [1] reported that the pooled prevalence of single-MAFLD in Asia was only 6%, the lowest compared to other regions, while the mixed-MAFLD reached as high as 37%. This finding was similar to our results, where only 2.93% of patients with HCC were attributable to single-MAFLD, but mixed-MAFLD HCC accounted for the majority in the total-MAFLD population. Our study showed the co-existence of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) with MAFLD, leading to a higher proportion of patients falling into the mixed HCC category. In the Asia-Pacific region, the co-existence of MAFLD and chronic hepatitis has become a common phenomenon [6]. Our previous meta-analysis demonstrated that the proportion of patients with hepatic steatosis, a prerequisite for MAFLD diagnosis, was 35.0% of the CHB population in the mainland of China, aligning closely with the prevalence of 36.5% in Asia [7]. Moreover, the pooled proportion of HCC in patients with CHB and HS was 10.0%, which was higher than 4% in patients with CHB alone [7]. Although the high prevalence of MAFLD and the relatively low proportion of HCC due to MAFLD may seem contradictory, as noted by Crane et al. [1], population-based evidence has revealed that a heavy burden of metabolic dysfunction increased the risk of HCC among patients with CHB with MAFLD [8]. The delineation of MAFLD has provided researchers with an extensive framework to explore the interplay between viral hepatitis and MAFLD in the progression of HCC [6]. These findings underscore the heightened risk of HCC associated with the overlap between MAFLD and chronic hepatitis, emphasizing the need for personalized management strategies for individuals with mixed-MAFLD HCC. Another interesting finding was the higher proportion of MAFLD within the mixed-MAFLD population, particularly noted in the ALD-related HCC cohort compared to the HBV- and HCV-related HCC cohorts, as observed in both our study and Crane’s meta-analysis. Our previous study demonstrated that all-cause and cause-specific mortality increased significantly with high weekly alcohol consumption in patients with MAFLD [9]. A limitation of this investigation and that of the systematic review conducted by Crane et al. was the absence of an alcohol intake assessment. Nakamura et al. proposed that the quantity of alcohol consumption should be analyzed using the criteria of MAFLD [10]. The mechanism underlying the interplay between alcohol intake and metabolic dysfunction that drives the development of liver fibrosis and HCC requires further study.

Our study demonstrated that patients with single-MAFLD HCC exhibited distinct HCC phenotypes, which validated the findings of this meta-analysis. With the aid of advanced imaging techniques and multiple serological markers, identifying the etiology of different liver diseases is not a daunting task. The challenge lies in risk stratification, prognostic assessment, and precision medical therapy tailored to patients due to diverse etiologies.

One limitation of our study, as well as the meta-analysis conducted by Crane et al. [1], was the lack of records on medication usage and other complications, such as sarcopenia [6,10]. Loss of skeletal muscle mass and function is prevalent among HCC population. In patients with MAFLD, sarcopenia is recognized as an important risk factor for the progression of liver fibrosis and cardiovascular diseases. The missing information limited the ability to perform a more specific analysis.

In conclusion, the categorization of HCC based on the new etiological classification has been instrumental in delineating the distinct clinical characteristics of HCC and enhancing our comprehensive understanding of the interplay between MAFLD and other chronic liver diseases. Despite the relatively modest sample size of our study, this multicenter cohort investigation is a significant augmentation of the meta-analysis conducted by Crane et al. [1].

Acknowledgments

Dr Li would like to acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82170609) and Jiangsu Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. BK20231118). Dr Shi would like to acknowledge the support from the Interdisciplinary Research Projectof HangzhouNormal University (2024JCXK06).

Abbreviations

- MAFLD

metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HS

hepatic steatosis

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- ALD

alcohol liver disease

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution

Conception or design of the work: Jie Li. Drafting the article: Xiangyu Wu and Wenjing Ni. Critical revision of the article: All authors. Final approval of the version to be published: All authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Clinical and Molecular Hepatology website (http://www.e-cmh.org).

Comparison of clinical characteristics among single-MAFLD, mixed-MAFLD and non-MAFLD HCC population

REFERENCES

- 1.Crane H, Eslick GD, Gofton C, Shaikh A, Cholankeril G, Cheah M, et al. Global prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2024;30:436–448. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2024.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Zou B, Yeo YH, Feng Y, Xie X, Lee DH, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999-2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:389–398. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang Z, Ding Y, Zhang W, Zhang R, Zhang L, Wang M, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of alcohol-related liver disease in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:1276. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15645-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie D, Shi J, Zhou J, Fan J, Gao Q. Clinical practice guidelines and real-life practice in hepatocellular carcinoma: A Chinese perspective. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:206–216. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2022.0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawaguchi T, Tsutsumi T, Nakano D, Eslam M, George J, Torimura T. MAFLD enhances clinical practice for liver disease in the Asia-Pacific region. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:150–163. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2021.0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou R, Yang L, Zhang B, Gu Y, Kong T, Zhang W, et al. Clinical impact of hepatic steatosis on chronic hepatitis B patients in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2023;30:793–802. doi: 10.1111/jvh.13872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SC, Su TH, Tseng TC, Chen CL, Hsu SJ, Liao SH, et al. Distinct effects of hepatic steatosis and metabolic dysfunction on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2023;17:1139–1149. doi: 10.1007/s12072-023-10545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu Y, Xu X, Fan Z, Ma X, Rui F, Ni W, et al. Different minimal alcohol consumption in male and female individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2024;44:865–875. doi: 10.1111/liv.15849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura T, Nakano M, Tsutsumi T, Amano K, Kawaguchi T. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is a ubiquitous latent cofactor in viral- and alcoholic-related hepatocellular carcinoma: Editorial on “Global prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. ClinMol Hepatol. 2024;30:705–708. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2024.0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of clinical characteristics among single-MAFLD, mixed-MAFLD and non-MAFLD HCC population