Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the implementation and trust‐building strategies associated with successful partnership formation in scale‐up of the Veteran Sponsorship Initiative (VSI), an evidence‐based suicide prevention intervention enhancing connection to U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and other resources during the military‐to‐civilian transition period.

Data Sources and Study Setting

Scaling VSI nationally required establishing partnerships across VA, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), and diverse public and private Veteran‐serving organizations. We assessed partnerships formalized with a signed memorandum during pre‐ and early implementation periods (October 2020–October 2022). To capture implementation activities, we conducted 39 periodic reflections with implementation team members over the same period.

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative case study evaluating the number of formalized VSI partnerships alongside directed qualitative content analysis of periodic reflections data using Atlas.ti 22.0.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

We first independently coded reflections for implementation strategies, following the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy, and for trust‐building strategies, following the Theoretical Model for Trusting Relationships and Implementation; a second round of inductive coding explored emergent themes associated with partnership formation.

Principal Findings

During this period, VSI established 12 active partnerships with public and non‐profit agencies. The VSI team reported using 35 ERIC implementation strategies, including building a coalition and developing educational and procedural documents, and trust‐building strategies including demonstrating competence and credibility, frequent interactions, and responsiveness. Cultural competence in navigating DoD and VA and accepting and persisting through conflict also appeared to support scale‐up.

Conclusions

VSI's partnership‐formation efforts leveraged a variety of implementation strategies, particularly around strengthening stakeholder interrelationships and refining procedures for coordination and communication. VSI implementation activities were further characterized by an intentional focus on trust‐building over time. VSI's rapid scale‐up highlights the value of partnership formation for achieving coordinated interventions to address complex problems.

Keywords: implementation scale‐up, implementation strategies, military transition, partnership formation, suicide prevention, trust‐building, veteran

What is known on this topic

Prevention of suicide among transitioning service members (TSMs) is a complex public health problem with many potential partners and a high level of uncertainty regarding effective solutions.

The Veteran Sponsorship Initiative (VSI) is an evidence‐based intervention to reduce suicide risk for TSMs by supporting partnerships in suicide prevention.

Partnerships are valued in implementing evidence‐based initiatives, but little research has examined trust‐building and partnership formation in implementation scale‐up and spread.

What this study adds

We conducted a qualitative case study of implementation strategies and trust‐building strategies associated with successful partnership formation in the scale‐up and spread of VSI from October 2020–October 2022.

The VSI implementation team leveraged diverse implementation and trust‐building strategies in establishing new partnerships; attending to strategies for successful partnership‐building is likely to be important in accelerating scale‐up and spread.

Implementation research should explore how fostering trust‐based relationships can support spread, sustainment, and innovation in confronting complex problems in health and healthcare.

1. INTRODUCTION

Suicide remains a significant public health concern in the United States (U.S.), particularly among military service members and Veterans. Suicide rates among Veterans continue to rise at a faster rate than among civilians, with the highest risk among Veterans aged 18–34 years. 1 The first year after military service, often called the “deadly gap”, can be a time of increased vulnerability. 2 During this period, many of the life supports and structures of the military—including housing, employment, healthcare, and social networks—fall away, while a service member must navigate a significant cultural shift back to civilian society. 3 Transitioning service members (TSMs) may also struggle with physical and mental health comorbidities associated with combat and other service‐related stressors. 4 , 5 , 6

Suicide prevention is a “wicked problem” characterized by having multiple complex causes, significant overlap with related problems, involvement from many partners, and uncertainty regarding effective solutions. 7 Preventing Veteran suicide is a top priority of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), 8 and a growing number of policy initiatives, including the Hannon Act and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Governor's and Mayor's Challenges to Prevent Suicide among Service Members, seek to strengthen suicide prevention efforts by implementing coordinated, evidence‐based healthcare and support services across local, state, and national Veteran‐serving organizations. 9 , 10 There have been repeated calls over time for public‐private partnerships to support more effective delivery of mental healthcare services for Veterans in the U.S., particularly post‐9/11. 11 , 12

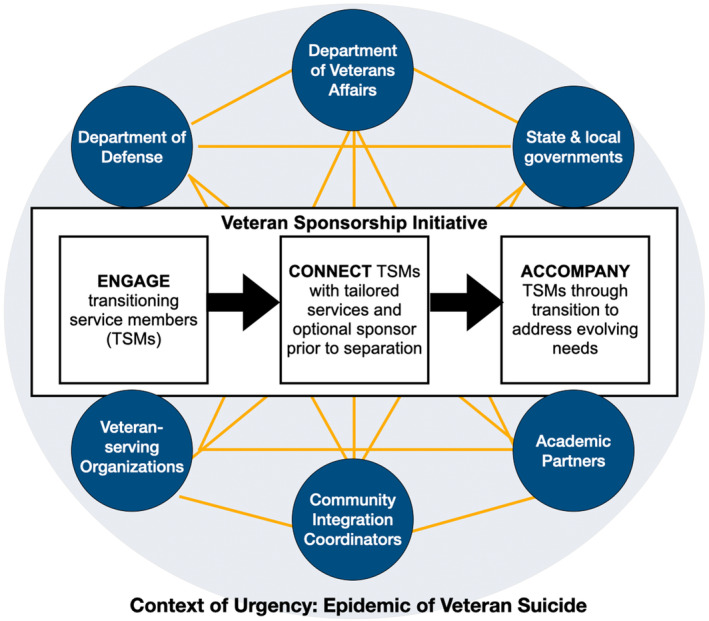

The Veteran Sponsorship Initiative (VSI) was established to bridge the deadly gap for TSMs by harnessing the power of partnerships in suicide prevention. 13 , 14 VSI is an evidence‐based intervention (see Figure 1) that combines peer sponsorship with linkages to U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and community‐based resources to ensure critical support during the military‐to‐civilian transition. 14 Core components of the intervention include: (1) engaging and enrolling TSMs before separation; (2) connecting TSMs with tailored services by identifying their priority needs, facilitating enrollment in VA healthcare and other services, and if they choose, linking them with a sponsor in their area; and (3) addressing their evolving needs, drawing on a connected network of VA, state, and community partners, and using a sophisticated data platform to support continuous information‐sharing throughout the transition. Sponsors are Veteran or civilian volunteers trained to provide transition support and assess suicide risk, who are matched with a TSM and regularly check in to provide ongoing support. This model of sponsorship draws upon similar procedures for managing service member relocations in the military, and thus is culturally appropriate and familiar for TSMs. 13 VSI has been shown to reduce reintegration difficulties and increase social connectedness, thereby mitigating two of the most impactful risk factors for Veteran suicide. 15 , 16

FIGURE 1.

Veteran Sponsorship Initiative: Program components and potential organizational partners.

Implementing VSI nationally requires establishing non‐monetary partnerships across the VA and U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) with diverse public and non‐profit Veteran‐serving organizations. Partnerships are essential for improving implementation, coordination, and sensemaking, that is, organizing shared understandings of a problem or environment in order to coordinate action. 17 , 18 , 19 Moreover, some researchers have asserted that trust‐building itself is an essential implementation strategy. Notably, Metz and colleagues proposed a theoretical model for understanding how trust is formed in implementation partnerships and described explicit technical and relational strategies for trust‐building. 20 Parallel work has examined the role of relationships within specific implementation strategies. 21 However, there are few published data on effective strategies for partnership‐building in the implementation of large‐scale initiatives, particularly in the context of complex initiatives like those required for population‐level suicide prevention. We conducted an in‐depth qualitative case study to assess implementation and trust‐building strategies associated with successful partnership formation in the scale‐up and spread of VSI.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data collection

Qualitative case study design is recommended for developing a comprehensive understanding of how and why a bounded phenomenon may have occurred, 22 , 23 and allows for drawing upon multiple data sources (including quantitative) to characterize a “program, activity, event, process.” 24 To examine implementation and trust‐building strategies associated with partnership formation in the VSI initiative, as part of a larger randomized stepped‐wedge hybrid type 2 effectiveness‐implementation evaluation, 14 we gathered data longitudinally between October 2020 and October 2022, during VSI's pre‐launch and early implementation periods. All activities were deemed to be non‐research evaluation and approved by the VA Associate Chief of Staff for Research at the Central Texas Healthcare System.

2.1.1. Partnership formation

For this case study, we defined “partnerships” as non‐monetary partnerships in support of VSI that were formalized through a memorandum facilitated by the VHA National Center for Healthcare Advancement and Partnerships (HAP), a program office that provides guidance on nonmonetary partnerships. Each signed memorandum laid out a set of shared objectives, responsibilities, and performance metrics. HAP provided descriptive data on the number, geographic distribution, funding type (public, non‐profit), and impact area (national, regional, state, county) of organizations partnering with VSI under a non‐monetary memorandum during this period. Partnerships were considered “active” if memoranda were current and not expired between October 2020–October 2022.

2.1.2. Periodic reflections

Periodic reflections are an ethnographically informed method in which brief guided discussions are conducted regularly with active implementation participants throughout an implementation effort; discussions capture and document implementation activities, events, and context. 25 , 26 Amid dynamic implementation, during which activities such as the use of implementation strategies may shift in response to unexpected events (e.g., change in policy or leadership), 27 , 28 reflections allow for continuous, low‐burden documentation from an information‐rich sample of participants, and thus take a purposive, “information power” approach to sampling. 29 To ensure a comprehensive overview of key implementation activities and events, we conducted periodic reflections every 1–2 months with key VSI implementation team members whose roles were positioned to allow insight on activities and events occurring across VSI's scale‐up effort. Roles were selected in discussion among the VSI team, and evolved as team size and scope expanded. The eight participants included: from VSI, the overall team lead, lead for sponsor education and training, lead for all TSM intake activities, and a VA regional coordinator; a program coordinator from an early partnering community organization; leads for enrollment and program coordination from a partnering non‐profit organization; and a representative from the partnering HAP office. Team members were individually invited by email to participate as part of VSI program evaluation. 14 Reflections were conducted one‐on‐one by either a PhD‐level medical anthropologist or clinical psychologist trained in qualitative interviewing, using a semi‐structured reflections guide adapted for the VSI program evaluation. 14 Reflections were conducted virtually and documented using near‐verbatim notes and/or recorded and transcribed using Microsoft Teams. Specific discussion prompts included recent implementation activities, implementation progress and/or challenges, changes to the intervention or implementation plan, relevant changes to the local or national environment, and planned next steps (see Online Appendix 1 for full guide).

2.2. Analysis

To characterize implementation strategies and trust‐building approaches utilized in the VSI initiative, we conducted directed qualitative content analysis of 39 periodic reflections gathered during the October 2020–October 2022 period, using Atlas.ti software. 30 Members of the VSI evaluation team (EF, SF, NK, EG) independently coded reflections for all implementation strategies used, following the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy 31 and a prior coding manual published for this purpose. 32 To aid in comprehensive coding, we further organized the codebook by ERIC strategy clusters recommended by Waltz et al. 33 Following recent guidance, we also included the “plan for sustainment” strategy under the Use iterative and evaluative strategies cluster. 34 Building on the Theoretical Model for Trusting Relationships and Implementation, proposed by Metz and colleagues (2022), we also coded for technical and relational strategies and attributes of trust‐building in implementation. After developing the full coding manual, the coding team independently coded five transcripts and met weekly to compare and discuss codes and establish internal consistency. During these discussions, we identified and refined additional inductive codes as needed to reflect emergent findings. From that time on, each reflection was coded by a single individual and reviewed by a second person; we continued to meet weekly to discuss and compare coding. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was achieved.

All qualitative findings were merged, summarized, and presented over several meetings to the implementation team, including those who had participated in periodic reflections, as a form of member checking. 35 , 36 , 37 Team members provided feedback resulting in iterative analysis and refinement of findings.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Partnership formation

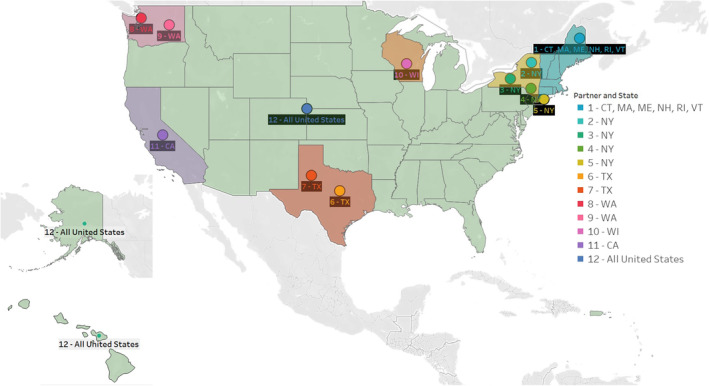

VSI established formal, signed memoranda with 12 organizational partners nationwide between October 2020 and October 2022, of which two were publicly funded and 10 were non‐profit organizations. Organizations served varying impact areas (one national, one regional, five state, and five county‐level). Figure 2 illustrates the geographic distribution of these partners across the U.S.

FIGURE 2.

Geographic distribution of Veteran Sponsorship Initiative (VSI) organizational partners (n = 12): October 2020–October 2022. Figure indicates partners serving regional (Connecticut [CT], Massachusetts [MA], Maine [ME], New Hampshire [NH], Rhode Island [RI], and Vermont [VT]), state/county (New York [NY], Texas [TX], Washington [WA], Wisconsin [WI], and California [CA]), and national impact areas. As of 2023, VSI had presence in all fifty states; figure denotes formalized partnerships as of October 2020–October 2022.

3.2. ERIC implementation strategies

In examining VSI implementation rollout and activities, three primary lanes of effort emerged: (1) developing and implementing training and standardization for intervention delivery (e.g., among sponsors, community partners, and VA‐based case managers); (2) developing interconnected networks for coordination and linkage to services across VA, state, local, and nonprofit organizations and service providers; and (3) building innovative cross‐system data infrastructure for secure information‐sharing. VSI team members during this period drew upon 35 implementation strategies (Table 1) to advance these lanes of effort, with some of the most frequently used implementation strategies including: building a coalition; promoting network weaving; staging implementation scale‐up; developing effective educational materials; revising professional roles; accessing new funding; planning for outcome evaluation; and using data warehousing techniques.

TABLE 1.

Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) Implementation Strategies in the Veteran Sponsorship Initiative (VSI): October 2020–October 2022.

| Implementation Strategy Clusters a | VSI Implementation Strategies: Pre‐ and Early Implementation | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Build stakeholder interrelationships | Build a coalition; Obtain formal commitments; Promote network weaving; Inform local opinion leaders; Capture & share local knowledge; Identify & prepare champions; Develop academic partnerships; Conduct local consensus discussions | Creation of the Veteran Sponsor Partnership Network to support partnerships between VA b regional offices and community‐based organizations |

| Train and educate stakeholders | Conduct educational meetings; Develop educational materials; Conduct ongoing training; Distribute educational materials; Make training dynamic; Create a learning collaborative | Creation of training programs to educate and certify peer sponsors to support transitioning service members during and after transition |

| Use iterative and evaluate strategies | Assess for readiness & identify barriers & facilitators; Stage implementation scale up; Develop & organize quality monitoring; Develop & implement tools for quality monitoring; Plan for outcome evaluation; Develop a formal implementation blueprint; Plan for sustainment | National and regional program evaluations; continuous formative evaluation and feedback to partners |

| Adapt and tailor to context | Use data warehousing techniques; Use data experts; Tailor strategies to overcome barriers & honor preferences; Use improvement/implementation advisors | Continuous refinement of coordination, monitoring, and implementation plans based on evaluation and partner feedback |

| Support intervention delivery | Create new teams; Develop resource‐sharing agreements; Revise professional roles | Ongoing assessment of existing capacity, refinement of roles, and creation of new staff roles as needed |

| Engage consumers | Involve Veterans in implementation; Engage consumers to increase demand | Strategic communication to support engagement of consumers and stakeholders |

| Utilize financial strategies | Access new funding; Use other payment schemes | Request expanded budget to support partnership activities |

| Change infrastructure | Change record systems; Mandate change | Partner with non‐profit organization to develop dashboard for inter‐agency communication |

| Provide interactive assistance | Provide clinical supervision | Weekly supervision for clinical team members |

Implementation strategy clusters reflect recommendations by Waltz et al. 33

US Department of Veterans Affairs.

These strategies were utilized over the pre‐ and early implementation periods by different subgroups within the VSI team, with strategy use evolving over time as VSI spread accelerated. Members of the training and education lane, for example, developed educational materials and both in‐person and hybrid training models for sponsors and community partners who connect TSMs with appropriate education, employment, financial, healthcare, and other services. The training and education group also standardized the roles of the community partner points of contact and their VA‐based counterparts, the VA Regional Community Coordinators. As pre‐implementation shifted into post‐launch activities, use of implementation strategies shifted from developing materials and modules to evaluating and refining these products, hiring and training staff to serve TSMs in new regions, and updating staffing guidance to reflect evolving roles and responsibilities.

In seeking to develop the interconnected network of partners necessary to achieve coordination and linkage of services for TSMs across DoD, VA, state, local, and other organizational partners, the VSI team relied on implementation strategies including efforts to build a coalition and promote network weaving, obtaining formal commitments from diverse partners, informing local opinion leaders, developing academic partnerships, and conducting consensus discussions.

As VSI implementation took hold across a broader network of partners, building a cross‐system data infrastructure became essential to facilitate timely, accessible, and protected information‐sharing across partners. Given high standards for information security across governmental and non‐governmental agencies, and as a proactive approach to preventing privacy or security breaches of Veterans' data, VSI leadership brought in data experts and implementation advisors and changed record systems by collaborating closely with a non‐profit partner to refine and integrate a dashboard for inter‐agency communication. This effort also required the VSI team to engage in consensus discussions with diverse partners, with the dual purpose of (1) achieving the necessary level of data system integration, and (2) establishing trust in a novel information platform.

3.3. Trust‐building strategies

Building new relationships and leveraging existing relationships were areas of intense focus for the VSI team. Over two years, the VSI team reported aiming for, if not always achieving, all of the four technical strategies (i.e., frequent interactions, responsiveness, demonstrating expertise and credibility, and achieving quick wins) and five relational strategies (i.e., bi‐directional communication, co‐learning, empathy, authenticity, vulnerability) identified by Metz and colleagues as supportive of trust‐building in implementation. 20

3.3.1. Technical strategies

Of the technical strategies for trust‐building, the VSI team relied most heavily upon frequent interactions, with key members of the team attending regular meetings—often in‐person—with a variety of potential partners to engage with individuals and organizations. Even amid the COVID‐19 pandemic, VSI's principal team lead made 25 in‐person visits around the country during this two‐year period. Similarly, leads for training, enrollment, and program intake made frequent site visits, delivered virtual and in‐person trainings, and attended weekly and monthly meetings with partners. As the regional coordinator indicated,

There's a lot of meetings so that I can represent the VA and the VSI…they need to see my face so that when I say, ‘we have a sponsor training,’ they say, ‘[She] needs something, let's support her because she supported us.’ Strategically building mutually beneficial relationships.

Throughout this period, VSI team members also displayed consistent responsiveness to the needs of partners, listening carefully to understand their needs and goals, and working intentionally to align with those needs wherever possible. As the VSI team lead indicated, this effort was about,

…finding out how do we speak their language and align with their outcomes so we're not seen as competition but we very much are seen as a way for them to accomplish their mission set in a much better way than they ever possibly could.

In some cases, this responsiveness took the form of providing information or services not otherwise available, for example, by providing local counties with information on Veterans relocating to their area, thus allowing them to move from “reactive to proactive preparation” [Lead, VSI Enrollment]. In other cases, this responsiveness took the form of taking on responsibilities that were not directly within the scope of VSI implementation, as when the team agreed to conduct an unfunded program evaluation for a pivotal partner.

As a new initiative, VSI team members were also attentive to purposefully demonstrating expertise and credibility. At one point early on, the team lead pondered,

[H]ow do we establish trust, then, with the states and offices and the entities, and then most importantly, need to be seen as a competent program or initiative. And how do we demonstrate that competence?

Demonstrating expertise and credibility required tailoring program messaging for each of VSI's growing array of audiences and partners. For example, in communicating with TSMs, the enrollment lead, a Veteran himself, made a point of sharing his own experience of transition. In communicating with academic and VA operational partners, the team emphasized published studies on the effectiveness of the VSI intervention in improving TSM well‐being, and highlighted the program's relevance to ongoing VA and federal policy priorities, like the Hannon Act.

While VSI team members described demonstrating expertise and credibility as an ongoing and multi‐faceted effort, they rarely reported achievement of quick wins, the last of the proposed technical strategies for trust‐building. The team lead did on several occasions express the desire to show rapid gains to partners, suggesting that the importance of quick wins was seen and valued, if difficult to achieve.

3.3.2. Relational strategies

Of the relational trust‐building strategies described by VSI team members, the most commonly relied upon were bi‐directional communication and co‐learning, both of which emerged in team members' descriptions of outreach and engagement efforts, as well as in negotiating work processes and relationships within the team. In one example, the lead for education and training described “working closely” with an individual within a partnering organization, “focusing on establishing or solidifying workflow and communication patterns to make it easier to transfer information.” Such bi‐directional communication seemed to allow for co‐learning to emerge as the VSI team worked with partners to identify and overcome emergent challenges. A member of HAP provided an example of such challenges:

[One VA program] tried to build out a peer support system but had a hard time finding a good fit for the facilitator model—trying to facilitate impact on social determinants of health. But [there were] concerns around how to coordinate with non‐VA staff working on non‐VA turf—how does the picture fit together?

As discussions among VA partners continued, they added, VSI was able to “figure out the solution of coordinating with community partners who facilitate engagement with VA.” In similar examples, ongoing bi‐directional communication with other VA partners prompted active problem‐solving and sensemaking, resulting in several innovations. In one case, the VSI team and partners were able to identify a novel pathway for expediting TSM enrollment in VA, while in another they developed a strategy for using VA virtual care clinics to serve TSMs during the transition from service.

Empathy, vulnerability, and authenticity likewise emerged in VSI team members' descriptions of engaging with partners of all kinds, within and outside the team. Team members described openly expressing their concerns about challenges within VSI as it evolved, which led to corresponding changes in workflow, developing novel solutions for sharing and reducing task burden, and supporting continuous learning. The team lead discussed having open conversations with partners around shared life experiences, particularly military service and experiences of a loved one's suicide. Such empathetic, vulnerable, and authentic discussions were described less frequently than efforts to display competence and support active problem‐solving, but at times seemed to play a critical role. As the team lead described one encounter,

…we had like a really really good individual session… and it's interesting that it was that meeting that helped me to establish a relational and interpersonal relationship to the point that he really trusted what we were doing.

3.4. Emergent features of the VSI approach

In addition to relying upon recognized strategies for implementation and trust‐building, VSI team members also exhibited cultural competence in navigating DoD and VA organizational structures and were able to accept and persist through conflict, which may have further facilitated VSI scale‐up.

3.4.1. Cultural competence

VSI is a Veteran‐driven team, with four of the core team members during this period having transitioned out of the military after combat deployments in Iraq or Afghanistan. Beyond offering a training module on Veteran cultural competence, the team itself demonstrated deep understanding of both DoD and VA organizational environments, which share a strong reliance on hierarchy but at times differ in operational norms and priorities. As a result, team members were able to tailor messaging and communications to address DoD priorities around service member suicides, ongoing military recruitment, and unit readiness, as well as VA priorities around the financial metrics of serving Veterans (e.g., number of encounters), protecting Veteran privacy and data, and preserving role clarity across VA program offices. As partnerships proliferated over the early launch period, so did the complexity of navigating a growing array of partners with increasingly diverse needs. The team's cultural competence in working within DoD and VA organizations appeared to be a foundational strength in a rapidly moving effort.

3.4.2. Accepting and persisting through conflict

At times, conflict arose during VSI's pre‐implementation and early launch over issues such as ownership of the initiative, clarifying roles and responsibilities, and determining appropriate resource‐ and/or data‐sharing across partners. The intake team lead evocatively described doing scissor kicks under his desk to release the tension in certain Zoom meetings. Yet the VSI team demonstrated an acceptance of conflict as part of the long‐term implementation process, and could even see its benefits. In the words of the team lead, who referenced Tuckman & Jensen's stages of group development, 38

When organizations don't go through storming, [how do] we know our words, our vulnerabilities, where's our cracks? But you know and kind of go underwater and get destroyed, but survive storming and end up with the link with your true partners.

The VSI case example further illustrated that trust is earned and building genuine partnerships can take time. As the enrollment lead described:

At Fort [redacted], the staffers are seeing [VSI] as a great program and as a team member on base. It's going to take time, like it took about a year just on one installation to get to this place where [they] trust them and see them not as a threat but as a partner.

Another team member noted the importance of “anticipating natural resistance,” and understanding that this kind of partnership building can sometimes require “sheer dogged persistence.”

4. DISCUSSION

VSI demonstrated success in establishing active partnerships during this two‐year period. Despite challenges that included the COVID‐19 pandemic, the VSI team achieved a dozen formally executed partnerships, setting the conditions for rapid scale‐up nationwide. To assess the use of strategies for implementation and trust‐building associated with these successes, we conducted qualitative content analysis of team member reflections during this same time period. Findings reveal that the VSI team utilized both formal implementation strategies (e.g., building coalitions, signing formal agreements) 31 , 33 , 34 and strategies for trust‐building (such as empathy and responsiveness). 20 Use of these strategies was accompanied, and likely enhanced, by the team's cultural competence in working with diverse partners, and acceptance of and persistence through conflict.

Notably, the VSI team collectively utilized a diverse range of implementation strategies in achieving coordinated scale‐up and spread. This finding is consistent with the broader literature, for while funded implementation studies often evaluate the impact of a single strategy or small set of strategies, 39 , 40 pragmatic assessments repeatedly find that implementation practitioners draw on a wide and often flexible array of strategies over the course of implementation. 41 , 42 , 43 Huynh et al. 43 identified 16 implementation strategies used in launching a cardiovascular risk reduction template, while Bunger et al. 32 utilized 45 strategies in implementing a county‐level children's behavioral health program. The need for so many discrete strategies may reflect the intensity of planning and problem‐solving required in implementing complex initiatives. 39 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47

Alongside structured activities for program launch and scale‐up, the VSI team also engaged in concerted effort to build partnerships. Partnerships in public health and health care are recognized for their utility in improving coordination, increasing efficiency, incorporating diverse perspectives, and generating solutions. 48 , 49 , 50 Even so, the dedicated process of building partnerships has been underexamined as an ingredient in effective implementation, and few guidelines exist for defining or operationalizing partnerships in implementation. 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 For this case study, we defined active partnerships in terms of non‐monetary partnerships formalized via signed memoranda, but the nature of partnerships is likely to vary across implementation settings and initiatives. Even within VSI, other types of partnerships also supported development and scale‐up. For example, the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 17 Center of Excellence (CoE) on Research for Returning War Veterans and the VISN 2 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) contributed direct funding, infrastructure, and staffing for key VSI positions, as well as research and administrative support. The VISN 17 CoE and VISN 2 MIRECC later expanded their collaboration to include HAP, which provided additional funding, infrastructure, and staffing, and developed the Veteran Sponsor Partnership Network (VSPN). Launched in September 2021, the VSPN directly facilitated the growth of VSI partnerships, as well as supporting VA staff at medical and regional VA facilities in implementing the partnerships. Recognizing this diversity, future studies examining partnership formation in implementation should consider how best to define the needs and nature of partnership as specific to their goals, activities, and context.

Recent theoretical work on trust‐building similarly invites new investigation of partnership formation in implementation science. 20 We found the VSI team's description of relationship‐building activities aligned well with the Metz et al. model, particularly its focus on frequent interaction, responsiveness, demonstrating credibility and expertise, bidirectional communication, and co‐learning, all of which appear to have been critical in setting the conditions for VSI's implementation and scale‐up. Drawing on the same model, Bartley et al. 21 have recently classified each of the ERIC taxonomy of implementation strategies on a continuum from relational to transactional, finding that the majority of implementation strategies rely upon relationships as an active ingredient in their success.

Taken in sum, these findings point to the interconnectedness of implementation strategies, as construed in the ERIC taxonomy, and the effort to build trusting relationships. In the VSI example, careful planning of the initial program rollout (as described in Geraci et al. 14 ) was accompanied by dedicated listening to partners, as part of committed engagement and frequent interaction. Highly attuned listening allowed for tailored and responsive iteration to action plans, and effective demonstration of credibility, value, and trustworthiness. Rather than highlighting the critical importance of specific individual strategies for implementation or trust‐building, this case study appears to underscore how strategies worked in concert, mutually reinforcing efforts and amplifying partnership formation over time. 17

Other lessons emerging from this analysis included the value of cultural competence in successfully navigating complex and hierarchical organizations. One element of the Metz et al. model that did not emerge as a good fit with these data was the suggestion that power differentials should be addressed by the implementation team prior to trust‐building efforts. While addressing power differentials is likely to be relevant, and perhaps essential, in participatory implementation, 55 it is not always feasible or salient in initiatives where the implementation team itself has relatively low power. This suggests that having a sophisticated grasp of how power is leveraged in institutions may be an asset, 56 , 57 , 58 which the VSI team demonstrated repeatedly, particularly in targeting outreach efforts and selecting key opinion leaders with whom to connect and plan.

Moreover, partnership‐embedded work, even where grounded in empathy, may come with storms. Rather than being dissuaded or daunted by conflict, however, VSI team members persisted in their attuned and proactive approach, often finding that a partner's early concerns were able to be acknowledged and addressed over time. Future work on productively managing conflict in implementation is likely to be of value to the field. 59

4.1. Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of this case study. The number of partnerships reported reflects formalized memoranda and does not reflect additional partnerships developed during this period. Qualitative findings draw upon self‐reported activities from the implementation team, do not rely on direct observation, and may not be comprehensive in describing all team activities, as the level of detail provided by periodic reflections is less granular than that offered by comparable (but often less feasible) methods like tracking logs. 32 Strengths of this case study that increase its rigor and trustworthiness include: use of an ethnographically‐informed method for gathering detailed data over the course of implementation 26 ; high levels of information power among participants, who as the implementation team were the experts in ongoing implementation activities 29 ; and iterative feedback provided by participants in member checking of preliminary findings. 36 , 37 We additionally drew upon recommended strategies for verification of qualitative data, including ensuring internal coherence between the research question and methods, selecting an appropriate sample, and continuously reexamining the fit between our theory‐driven coding for ERIC implementation and trust‐building strategies, inductively‐derived codes, and data. 60 Although this case study was observational in nature and made no explicit effort to improve team capacity for partnerships, cultivating skillsets for trust, relationships, and collaboration is likely to be of benefit in amplifying implementation impact. 20 , 21

4.2. Conclusions

This case study is among the first to directly examine strategies for establishing partnerships in implementation. Scale‐up of complex initiatives like those required for population‐level suicide prevention is likely to require strong partnerships, and attending to the characteristics of successful partnership‐building is an important element of accelerating scale‐up and spread. Implementation research and practice should continue to explore how an intentional focus on fostering trust‐based relationships can support spread, sustainment, and innovation in confronting wicked problems in health and health care.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Funding for this work was provided by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC 20–170; J. Geraci, PI), the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 17 Heart of Texas Network, the VISN 17 Center of Excellence (CoE) for Research on Returning War Veterans, the VISN 2 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, the Bronx VA Medical Center, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) National Center for Healthcare Advancement and Partnerships (HAP). Dr. Krauss is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Central Texas VA Health Care System, and the VISN 17 CoE. Dr. Frankfurt is supported by an Office of Rehabilitation Research and Development Career Development Award (IK1RX003495).

Supporting information

Appendix 1. Supporting Information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge valuable feedback and suggestions offered in the peer review process. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Finley EP, Frankfurt SB, Kamdar N, et al. Partnership building for scale‐up in the Veteran Sponsorship Initiative: Strategies for harnessing collaboration to accelerate impact in suicide prevention. Health Serv Res. 2024;59(Suppl. 2):e14309. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14309

[Correction added on 4 October 2024, after first online publication: The copyright line was changed.]

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramchand R. Suicide Among Veterans: Veterans' Issues in Focus. RAND Corporation; 2021. doi: 10.7249/PEA1363-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sokol Y, Gromatsky M, Edwards ER, et al. The deadly gap: understanding suicide among veterans transitioning out of the military. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300:113875. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finley EP. Fields of Combat: Understanding PTSD among Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. Cornell University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Copeland LA, Finley EP, Rubin ML, Perkins DF, Vogt DS. Emergence of probable PTSD among U.S. veterans over the military‐to‐civilian transition. Psychol Trauma. 2022;15(4):697‐704. doi: 10.1037/tra0001329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borowski S, Rosellini AJ, Street AE, Gradus JL, Vogt D. The first year after military service: predictors of U.S. Veterans' suicidal ideation. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(2):233‐241. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shor R, Borowski S, Zelkowitz RL, et al. The transition to civilian life: impact of comorbid PTSD, chronic pain, and sleep disturbance on veterans' social functioning and suicidal ideation. Psychol Trauma. 2022;15(8):1315‐1323. doi: 10.1037/tra0001271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sobelson M. A Wicked Public Health Problem of the West: Clinical Perspectives and Organizational Dynamics for Preventing Suicide in Utah. Harvard University; 2019. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2457562376?fromopenview=true&pq-origsite=gscholar [Google Scholar]

- 8. Veterans Health Administration Priorities & Strategic Enablers: 6 Effective Ways to Drive Change and Innovation within VHA. Veterans Health Administration; 2023. Accessed October 27, 2023. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/Veterans_Health_Administration_Priorities_and_Strategic_Enablers.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9. S.785—Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019. Published October 17 2020. Accessed April 23, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- 10. Governor's and Mayor's Challenges to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, Veterans, and their Families. Published March 29 2023. Accessed April 23, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/smvf-ta-center/mayors-governors-challenges

- 11. Pedersen ER, Eberhart NK, Williams KM, Tanielian T, Batka C, Scharf DM. Public‐private partnerships for providing behavioral health care to veterans and their families: what do we know, what do we need to learn, and what do we need to do? Rand Health Q. 2015;5(2):18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chretien JP, Chretien KC. Coming home from war. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):953‐956. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2359-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geraci JC, Dichiara A, Greene A, et al. Supporting servicemembers and veterans during their transition to civilian life using certified sponsors: a three‐arm randomized controlled trial. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(Suppl 2):248‐259. doi: 10.1037/ser0000764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geraci JC, Finley EP, Edwards ER, et al. Partnered implementation of the veteran sponsorship initiative: protocol for a randomized hybrid type 2 effectiveness—implementation trial. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s13012-022-01212-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klonsky ED, Pachkowski MC, Shahnaz A, May AM. The three‐step theory of suicide: description, evidence, and some useful points of clarification. Prev Med. 2021;152:106549. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schafer KM, Duffy M, Kennedy G, et al. Suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death among veterans and service members: a comprehensive meta‐analysis of risk factors. Mil Psychol. 2022;34(2):129‐146. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2021.1976544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Himmelman AT. Collaboration for a Change: Definitions, Decision‐Making Models, Roles, and Collaboration Process Guide. 2002. Accessed January 25, 2023 http://tennessee.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Himmelman-Collaboration-for-a-Change.pdf

- 18. Kania J, Mark K. Collective impact. Stanf Soc Innov Rev. 2011;9:3641. doi: 10.48558/5900-KN19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weick KE. Sensemaking in Organizations. Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Metz A, Jensen T, Farley A, Boaz A, Bartley L, Villodas M. Building trusting relationships to support implementation: a proposed theoretical model. FrontHealth Serv. 2022;2:894599. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.894599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bartley L, Metz A, Fleming WO. What implementation strategies are relational? Using relational theory to explore the ERIC implementation strategies. FrontHealth Serv. 2022;2:913585. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.913585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boblin SL, Ireland S, Kirkpatrick H, Robertson K. Using Stake's qualitative case study approach to explore implementation of evidence‐based practice. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(9):1267‐1275. doi: 10.1177/1049732313502128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. TQR. 2015;13(4):544‐559. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 3rd ed., [Nachdr.] SAGE Publ; 2008:20. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brunner J, Farmer MM, Bean‐Mayberry B, et al. Implementing clinical decision support for reducing women Veterans' cardiovascular risk in VA: a mixed‐method, longitudinal study of context, adaptation, and uptake. FrontHealth Serv. 2022;2:946802. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.946802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Finley EP, Huynh AK, Farmer MM, et al. Periodic reflections: a method of guided discussions for documenting implementation phenomena. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0610-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1). doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chambers DA, Norton WE. The Adaptome. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):S124‐S131. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753‐1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. ATLAS.ti Mac (version 22) [Qualitative data analysis software]. 2022. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://atlasti.com

- 31. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bunger AC, Powell BJ, Robertson HA, MacDowell H, Birken SA, Shea C. Tracking implementation strategies: a description of a practical approach and early findings. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12961-017-0175-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nathan N, Powell BJ, Shelton RC, et al. Do the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) strategies adequately address sustainment? FrontHealth Serv. 2022;2:905909. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.905909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs‐principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt2):2134‐2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1802‐1811. doi: 10.1177/1049732316654870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Torrance H. Triangulation, respondent validation, and democratic participation in mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res. 2012;6(2):111‐123. doi: 10.1177/1558689812437185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tuckman BW, Jensen MAC. Stages of small‐group development revisited. Group Organ Stud. 1977;2(4):419‐427. doi: 10.1177/105960117700200404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kirchner JE, Smith JL, Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Proctor EK. Getting a clinical innovation into practice: an introduction to implementation strategies. Psychiatry Res. 2020;283:112467. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1). doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rogal SS, Yakovchenko V, Waltz TJ, et al. The association between implementation strategy use and the uptake of hepatitis C treatment in a national sample. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0588-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rogal SS, Yakovchenko V, Waltz TJ, et al. Longitudinal assessment of the association between implementation strategy use and the uptake of hepatitis C treatment: year 2. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0881-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huynh AK, Hamilton AB, Farmer MM, et al. A pragmatic approach to guide implementation evaluation research: strategy mapping for complex interventions. Front Public Health. 2018;6:134. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, Ellis LA, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1057-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cullen L, Hanrahan K, Edmonds SW, Reisinger HS, Wagner M. Iowa implementation for sustainability framework. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01157-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, Taylor BS, McCannon CJ, Lindberg C, Lester RT. How complexity science can inform scale‐up and spread in health care: understanding the role of self‐organization in variation across local contexts. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:194‐202. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reed JE, Howe C, Doyle C, Bell D. Simple rules for evidence translation in complex systems: a qualitative study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1076-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chung B, Ngo VK, Ong MK, et al. Participation in training for depression care quality improvement: a randomized trial of community engagement or technical support. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(8):831‐839. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Engaging Your Community: A Toolkit for Partnership, Collaboration, and Action. John Snow, Inc. 2012. Accessed May 9, 2023 https://publications.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=14333&lid=3

- 50. Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, et al. Community‐partnered cluster‐randomized comparative effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning or resources for services to address depression disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(10):1268‐1278. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Finley EP, Closser S, Sarker M, Hamilton AB. Editorial: the theory and pragmatics of power and relationships in implementation. Front Health Serv. 2023;3:1168559. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2023.1168559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Villalobos A, Blachman‐Demner D, Percy‐Laurry A, Belis D, Bhattacharya M. Community and partner engagement in dissemination and implementation research at the National Institutes of Health: an analysis of recently funded studies and opportunities to advance the field. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s43058-023-00462-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Blachman‐Demner DR, Wiley TRA, Chambers DA. Fostering integrated approaches to dissemination and implementation and community engaged research. Behav Med Pract Policy Res. 2017;7(3):543‐546. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0527-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Anderson LM, Adeney KL, Shinn C, Safranek S, Buckner‐Brown J, Krause LK. Community coalition‐driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane public health group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online June 15. 2015;CD009905. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009905.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ramanadhan S, Davis MM, Armstrong R, et al. Participatory implementation science to increase the impact of evidence‐based cancer prevention and control. Cancer Causes Control. 2018;29(3):363‐369. doi: 10.1007/s10552-018-1008-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hockett Sherlock S, Goedken CC, Balkenende EC, et al. Strategies for the implementation of a nasal decolonization intervention to prevent surgical site infections within the veterans health administration. FrontHealth Serv. 2022;2:920830. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.920830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Majumdar P, Gupta SD, Mangal DK, Sharma N, Kalbarczyk A. Understanding the role of power and its relationship to the implementation of the polio eradication initiative in India. FrontHealth Serv. 2022;2:896508. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.896508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shattuck D, Richard BO, Jaramillo ET, Byrd E, Willging CE. Power and resistance in schools: implementing institutional change to promote health equity for sexual and gender minority youth. FrontHealth Serv. 2022;2:920790. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.920790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tjosvold D, Wong ASH, Chen NYF. Managing conflict for effective leadership and organizations. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management. Oxford University Press; 2019. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1(2):13‐22. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Supporting Information.