Abstract

Objective

To evaluate racial and ethnic differences in patient experience among VA primary care users at the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) level.

Data Source and Study Setting

We performed a secondary analysis of the VA Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients‐Patient Centered Medical Home for fiscal years 2016–2019.

Study Design

We compared 28 patient experience measures (six each in the domains of access and care coordination, 16 in the domain of person‐centered care) between minoritized racial and ethnic groups (American Indian or Alaska Native [AIAN], Asian, Black, Hispanic, Multi‐Race, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander [NHOPI]) and White Veterans. We used weighted logistic regression to test differences between minoritized and White Veterans, controlling for age and gender.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

We defined meaningful difference as both statistically significant at two‐tailed p < 0.05 with a relative difference ≥10% or ≤−10%. Within VISNs, we included tests of group differences with adequate power to detect meaningful relative differences from a minimum of five comparisons (domain agnostic) per VISN, and separately for a minimum of two for access and care coordination and four for person‐centered care domains. We report differences as disparities/large disparities (relative difference ≥10%/≥ 25%), advantages (experience worse or better, respectively, than White patients), or equivalence.

Principal Findings

Our analytic sample included 1,038,212 Veterans (0.6% AIAN, 1.4% Asian, 16.9% Black, 7.4% Hispanic, 0.8% Multi‐Race, 0.8% NHOPI, 67.7% White). Across VISNs, the greatest proportion of comparisons indicated disparities for three of seven eligible VISNs for AIAN, 6/10 for Asian, 3/4 for Multi‐Race, and 2/6 for NHOPI Veterans. The plurality of comparisons indicated advantages or equivalence for 17/18 eligible VISNs for Black and 12/14 for Hispanic Veterans. AIAN, Asian, Multi‐Race, and NHOPI groups had more comparisons indicating disparities by VISN in the access domain than person‐centered care and care coordination.

Conclusions

We found meaningful differences in patient experience measures across VISNs for minoritized compared to White groups, especially for groups with lower population representation.

Keywords: access to primary care, health inequities, health status disparities, patient satisfaction, patient‐centered care, regional medical programs, veterans health services

What is known on this topic

There are documented racial and ethnic disparities in patient experience, including in the Veterans Health Administration (VA).

It is not clear if there are regional variations in patient experience disparities in the VA.

What this study adds

This study identified regional variation in racial and ethnic disparities in patient experience among VA users across the United States.

Black and Hispanic Veterans had less disparate patient experiences compared to groups with lower representation in the VA.

Efforts to reduce disparities in patient experience in the VA should be tailored accordingly to regional evidence of such disparities.

1. INTRODUCTION

Patient experience, defined as the range of interactions patients have with the healthcare system, is a fundamental tenet of healthcare quality. 1 , 2 , 3 Patient experience includes core aspects of healthcare delivery that patients value highly, such as bidirectional communication with providers, access to necessary information, receiving timely appointments, and patient‐centered care coordination. Higher levels of positive patient experience are generally associated with improved outcomes, including medication adherence, 4 less emergency department use, 5 fewer avoidable hospitalizations, 6 hospital readmissions, 7 and lower inpatient mortality for patients with myocardial infarction. 8

There are well‐documented racial and ethnic disparities in patient experience in the United States. 5 , 9 , 10 Generally, minoritized racial and ethnic (hereafter “minoritized”) groups report worse patient experiences than non‐Hispanic White (hereafter “White”) groups. Disparities in patient experience are rooted in structurally racist factors that influence neighborhood investment and resultant available healthcare infrastructure, such that neighborhoods with predominantly minoritized populations have fewer and lower‐quality healthcare services available. 11 , 12 Most of the literature on racial and ethnic disparities in patient experience focuses on non‐Hispanic Black (hereafter “Black”) and Hispanic versus White disparities; however, racial and ethnic groups with lower representation in the United States, such as Asian American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI), and American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) groups, also report worse patient experiences than White individuals. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17

One of the core values of the Veterans Health Administration (VA), the nation's largest integrated healthcare system, is to provide a positive patient experience for all enrolled Veterans, including the most vulnerable. Despite this, there are documented disparities in patient experience by race and ethnicity in the VA. 18 In prior studies, Black and Hispanic Veterans reported worse patient experiences compared to White Veterans overall, 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 and in various settings, including outpatient primary care, 20 , 22 , 24 outpatient specialty care, 19 , 23 and inpatient care. 21 In these studies, patient experience was measured using several methods, including data from the VA Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP)‐Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH), which is based on Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys, other validated surveys and patient interviews. These measurements include different elements of patient experience such as timely access to care, communication with the care team, self‐management support, satisfaction with facilities, and overall satisfaction with care. SHEP‐PCMH survey data were used to generate the 2021 National Veteran Health Equity Report, which highlights disparities in patient experience for underserved and minoritized compared to White groups using nationally aggregated data. 18

While prior evidence suggests geographic variation in racial and ethnic disparities in patient outcomes across the United States, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 it is unknown if disparities in patient experience also vary geographically. It is plausible that disparities may differ regionally due to local geographical contexts and attributes of the lived environment. Such attributes include community social determinants of health, such as percentage of population living in poverty, area deprivation, social vulnerability, and residential segregation. These attributes have been associated with racial and ethnic disparities in certain process and clinical outcomes, such as late‐stage cancer diagnosis 29 and mortality. 30

The VA is an ideal environment in which to study regional variations in outcomes and patient experience as it is organized into 18 regions across the United States and Territories named Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Each VISN consists of healthcare systems with associated medical centers and community clinic sites within a defined geographical catchment area. Each VISN operates semi‐independently from VA Central Office insofar as VISN leadership has autonomy in managing strategic plans and resource allocation. Prior research suggests there are VISN‐level variations in certain process and clinical outcomes, including appointment wait times, 31 participation in the MOVE! Behavioral weight management program and referral to bariatric surgery, 32 screening for diabetic retinopathy, 33 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation rates. 34 However, to date, there is limited research examining VISN‐level variation in patient experience within the VA. 35 Additionally, there is limited literature on VISN‐level variation on racial and ethnic differences in patient experience between minoritized and White groups. Exploration of variation in these differences is valuable as it would allow leaders in VISNs where there are racial and ethnic disparities in patient experience to allocate and tailor resources to close these gaps. Further, it could identify VISNs in which minoritized groups have similar or better experiences than White patients, which could guide research aimed at identifying factors leading to parity in patient experience among racial and ethnic groups. Therefore, the purpose of this project is to describe VISN‐level variation in differences in patient experience measures between minoritized groups and White groups across the VA. The purpose is also to describe variations in patient experiences for minoritized groups overall, and for individual minoritized groups among VISNs.

2. METHODS

This research is an extension of the findings from the 2021 National Veteran Health Equity Report. 18 This report provides information on disparities in patient experience and healthcare quality for Veterans using VA services. The report presents disparities by several sociodemographic characteristics, including race and ethnicity, gender, age, and socioeconomic status (SES). Patient experience measures were derived from data from the SHEP‐PCMH survey and analyzed by VISN.

2.1. Design and data sources

We utilized data from the VA SHEP‐PCMH survey from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2019. SHEP‐PCMH is a survey administered monthly by the VA Office of Quality and Patient Safety to a national stratified random sample of approximately 60,000 VA patients per month who had a qualifying ambulatory care visit in the prior month. The overall response rate for the combined four‐year SHEP surveys was approximately 38%. 36 Poststratification weights which incorporated sampling design and non‐response were included in the analysis. Data were linked to VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) electronic health record data to obtain measures of participant demographic variables, including race, ethnicity, and sex.

The analysis received a Determination of Non‐Research from the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Dependent variables

We examined patient experience measures included in the National Veteran Health Equity Report in the domains of access, person‐centered care, and care coordination. There were 28 questions total: six each in the access and care coordination domains and 16 in the person‐centered care domain. A full list of data elements is included in Supplemental Table 1. Responses to questions with multiple response categories (Likert or numerical scale) were dichotomized into the most favorable category (i.e., “always,” “a lot,” 9–10) and all other categories combined in accordance with guidelines for scoring patient experience from CAHPS surveys. 15

2.3. Independent variables

Our primary predictor of interest was patient race and ethnicity. Patient race and ethnicity were obtained from CDW supplemented with data from the VA's Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership data model. 37 Race and ethnicity data were available for 96.8% of patients overall. 18 Race and ethnicity were combined into one variable where individuals who identified Hispanic ethnicity were categorized as Hispanic, and non‐Hispanic individuals were categorized by race. Patient race and ethnicity were then recategorized as AIAN, Asian, Black, Hispanic, Multi‐Race, NHOPI, and White. We also included VISN as a predictor.

2.4. Covariates

Covariates included age and sex. Sex was limited to male and female categories. These covariates were included because of variability in their distributions among racial and ethnic groups. 18 In our primary analysis, we purposefully omitted other covariates known to be associated with race and ethnicity within the VA (i.e., SES, comorbidity, self‐rated physical and mental health) so that our findings were representative of different racial and ethnic groups, rather than attempting to determine the isolated association of race and ethnicity with patient experience after controlling for potential confounders. This approach to reporting is consistent with methods used by the AHRQ National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports, where disparities between minoritized and White patients are reported without adjustment for covariates. 38

2.5. Statistical analysis

First, we calculated weighted descriptive statistics on the analytic sample. We performed weighted logistic regression models of each binary experience measure, controlling for sex and age, to test differences between minoritized groups and White individuals. Model specifications included race or ethnicity, VISN, a race or ethnicity‐by‐VISN interaction terms, and covariates. From the initial model coefficients, we estimated adjusted percentages of positive patient experiences for each racial and ethnic group within each VISN, and subsequently tested differences between each minoritized and White group in these positive experience percentages.

Next, we applied dual criteria to define meaningful differences between minoritized groups and White individuals within each VISN, similar to approaches used in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) National Healthcare Quality Disparities Report 38 and National Veterans Health Equity Report. 18 These criteria were a statistically significant difference in positive patient experience at a two‐tailed p‐value of <0.05, with a relative difference value of at least ±10%. In the context of racial and ethnic disparities research, the relative difference indicates how much farther from/closer to the best possible outcome a minoritized group is than the White group. The relative difference is a preferable measure of disparity/advantage over the absolute difference when the criterion for what is meaningful and important varies depending on where the historically advantaged group is on the outcome or experience measure. See Supplemental Item 1 for a detailed description and example of relative difference. We chose a minimum relative difference of 10% as a criterion of meaningfulness. If the minoritized group experienced meaningfully worse care, this was considered a disparity; if the minoritized group experienced meaningfully worse care at a relative difference of 25% or greater, this was considered a large disparity; if the care experienced was meaningfully better, it was considered an advantage; if there was no meaningful difference, this was considered equivalent.

Additionally, smaller sample sizes at the VISN level for several race and ethnicity groups have implications for increasing risk for type II error. To address these, we calculated the power offered by our existing sample sizes to detect meaningful differences in each patient experience measure, and considered tests of differences with ≥80% power as adequately powered, and tests with <80% power as underpowered. We report tests of differences in patient experiences either as evidence of disparities, advantages or equivalent for only those comparisons that are adequately powered, but with two exceptions. First, if a test of a difference was underpowered, but revealed evidence of a meaningful difference that was statistically significant, we reported this as a disparity if the minoritized group experienced significantly worse care, or as an advantage if the minoritized group experienced significantly better care. The rationale for inclusion is that the test detected a relative difference that is larger in magnitude than our minimum of 10% and was therefore more sensitive to this larger difference. Second, if a test was underpowered, but revealed a statistically significant difference that was not meaningful, we reported this as equivalent because the groups are effectively equivalent or comparable in their care experience in the presence of a difference that is not meaningful.

We performed analyses for the compiled 28 measures and categorized the results by domain. We decided that to meaningfully summarize the experience of a racial or ethnic minoritized group in each VISN, there should be adequate power to detect a meaningful difference on at least five of the 28 measures. Within domains, we decided that to meaningfully summarize the experience of a minoritized group in each VISN, there should be adequate power to detect a meaningful difference on at least two of the six measures in the access and care coordination domains and four of the 16 measures in the person‐centered care domain. If these thresholds were not met by VISN, we did not include the findings in these results. Comparisons are also illustrated by VISN between Black and Hispanic groups, as these groups had the highest representation across VISNs.

2.6. Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis adding highest educational attainment (categorized as some high school or less, high school graduate or GED recipient, some college or college graduate/advanced degree) and self‐rated physical health (categorized as excellent/very good or good/fair/poor) as covariates. We selected these variables based on recommendations from AHRQ regarding case‐mix adjustment in CAHPS analyses. 39

3. RESULTS

Overall, there were 1,038,212 VA users included in the sample (Table 1), representing a weighted population race and ethnicity distribution that was 0.6% AIAN, 1.4% Asian, 16.9% Black, 7.4% Hispanic, 0.8% Multi‐Race, 0.8% NHOPI, 67.7% White, and 4.4% of unknown race or ethnicity. The weighted sample was 90.2% male; 16.4% were age 18–44, 32.5% were 45–64, and 51.0% were 65 or older.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics of racial and ethnic groups by Veterans Integrated Service Network, sex, and age.

| Racial or ethnic group a | AIAN N = 6447 | Asian N = 8015 | Black N = 102,752 | Hispanic N = 45,220 | Multi‐Race N = 6373 | NHOPI N = 7185 | White N = 806,692 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample weighted % | 0.6 | 1.4 | 16.9 | 7.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 67.7 |

| Characteristic b | % | % | % | % | % | % | % |

| VISN | |||||||

| VISN median percentage | 0.4 | 0.5–0.6 | 13.0–13.1 | 3.1–3.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 74.0 |

| VISN range | 0.2–2.0 | 0.2–8.4 | 2.7–41.4 | 1.3–20.1 | 0.3–1.8 | 0.3–3.5 | 51.3–92.1 |

| Patient | |||||||

| Male | 84.5 | 87.4 | 83.3 | 89.1 | 82.5 | 89.5 | 92.1 |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–44 | 19.6 | 41.7 | 17.2 | 31.2 | 32.4 | 23.0 | 14.1 |

| 45–64 | 37.8 | 33.2 | 50.2 | 33.4 | 32.2 | 37.2 | 28.2 |

| 65+ | 42.6 | 25.1 | 32.6 | 35.0 | 35.4 | 39.8 | 57.8 |

Abbreviations: AIAN, American Indian or Alaska Native; NHOPI, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; VISN, Veterans Integrated Service Network.

Unweighted sample numbers for each racial and ethnic group reported.

Weighted row percentages reported for VISN. Weighted column percentages reported for sex and age.

There was VISN‐level variation in the distribution of race and ethnicity. The range in VISN‐level distribution was 0.2–2% for AIAN, 0.2–8.4% for Asian, 2.7–41.4% for Black, 1.3–20.1% for Hispanic, 0.3–1.8% for Multi‐Race, 0.3–3.5% for NHOPI, and 51.3–92.1% for White groups (Table 1).

3.1. Analysis of all patient experience measures

There were seven eligible VISNs for comparison for AIAN, 10 for Asian, 18 for Black, 14 for Hispanic, four for Multi‐Race, and six for NHOPI groups (Table 2). The average percentage of detected disparities among all groups across VISNs was 20.0%; the average percentage of detected advantages among all groups across VISNs was 33.8%. The percentage disparities among all groups varied across VISN, ranging from 0% (0 of 60 of eligible comparisons) to 53.1% (26 of 49 eligible comparisons) (Supplemental Figure 1).

TABLE 2.

Summary of patient experience measures compared to White group, adjusted for age and sex, across Veterans Integrated Service Networks overall and by patient experience domains.

| Domains | Race, ethnicity | # Eligible VISNs | # Eligible measures | Eligible measures with a disparity a across VISNs, n (%) | Eligible measures with a large disparity b across VISNs, n (%) | Eligible measures with an advantage c across VISNs, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | AIAN | 7 | 53 | 28 (52.8) | 24 (45.3) | 19 (35.8) |

| Asian | 10 | 92 | 35 (38.0) | 30 (32.6) | 26 (28.3) | |

| Black | 18 | 414 | 48 (11.6) | 4 (1.0) | 138 (33.3) | |

| Hispanic | 14 | 216 | 23 (10.6) | 7 (3.2) | 71 (32.9) | |

| Multi‐Race | 4 | 27 | 20 (74.1) | 18 (66.7) | 5 (18.5) | |

| NHOPI | 6 | 60 | 18 (30.0) | 11 (18.3) | 32 (53.3) | |

| Access | AIAN | 5 | 13 | 9 (69.2) | 5 (38.5) | 1 (7.7) |

| Asian | 9 | 27 | 16 (59.3) | 14 (51.9) | 3 (11.1) | |

| Black | 18 | 84 | 16 (19.0) | 2 (2.4) | 14 (16.7) | |

| Hispanic | 13 | 49 | 10 (20.4) | 2 (4.1) | 6 (12.2) | |

| Multi‐Race | 6 | 17 | 14 (82.4) | 11 (64.7) | 1 (5.9) | |

| NHOPI | 5 | 15 | 6 (40.0) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Person‐centered care | AIAN | 4 | 22 | 12 (54.5) | 12 (54.5) | 10 (45.5) |

| Asian | 4 | 35 | 10 (28.6) | 7 (20.0) | 8 (22.9) | |

| Black | 18 | 245 | 26 (10.6) | 2 (0.8) | 101 (41.2) | |

| Hispanic | 11 | 115 | 7 (6.1) | 2 (1.7) | 44 (38.3) | |

| Multi‐Race | 2 | 11 | 7 (63.6) | 7 (63.6) | 3 (27.3) | |

| NHOPI | 3 | 25 | 3 (12.0) | 1 (4.0) | 19 (76.0) | |

| Care coordination | AIAN | 5 | 12 | 6 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) | 5 (41.7) |

| Asian | 6 | 19 | 4 (21.1) | 4 (21.1) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Black | 18 | 85 | 6 (7.1) | 0 | 23 (27.1) | |

| Hispanic | 12 | 47 | 5 (10.6) | 2 (4.3) | 17 (36.2) | |

| Multi‐Race | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| NHOPI | 4 | 15 | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20.0) | 9 (60.0) |

Note: VISNs with a minimum of five of 28 adequately powered patient experience comparisons overall, two of six adequately powered experience measures in the domains of access and care coordination, and four of 16 in the domain of patient‐centered care were considered eligible for analysis.

Abbreviations: AIAN, American Indian or Alaska Native; NHOPI, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; VISN, Veterans Integrated Service Network.

Includes disparities (≥10%–25% relative difference) and large disparities (≥ 25% relative difference).

Large disparity is a relative difference of ≥25% in favor of White group.

Advantage is a relative difference of ≥10% in favor of racial and ethnic minoritized group.

Across VISNs, 52.8% of eligible comparisons indicated disparities for AIAN, 38.0% for Asian, 11.6% for Black, 10.6% for Hispanic, 74.1% for Multi‐Race, and 30.0% for NHOPI groups; these included 45.3% of eligible comparisons as large disparities for AIAN, 32.6% for Asian, 1.0% for Black, 3.2% for Hispanic, 66.7% for Multi‐Race, and 18.3% for NHOPI groups (Table 2). For each group, in at least one VISN, there were no disparities on any measures (Supplemental Figure 2). For AIAN and Asian groups, there were two VISNs in which all comparisons indicated disparities, and for Multi‐Race and NHOPI groups, there was one VISN in which all comparisons indicated disparities.

Black and Hispanic groups overall had the greatest representation in the number of eligible VISNs and overall showed advantages on the highest percentage of eligible measures (Table 2). In one VISN, there was a high proportion of eligible comparisons indicating disparities for both Black (10 of 23 including two large disparities; 43.4%) and Hispanic (four of five including two large disparities; 80.0%) groups (Supplemental Figure 3). Black groups tended to show advantages on patient experience measures in VISNs where the overall percentage of eligible measures indicating disparities for all minoritized groups was lower; this pattern did not hold for Hispanic groups.

3.2. Analysis by domain

Comparisons in patient experience measures by domain are summarized in Table 2. Generally, more comparisons were disparities for access compared to the other domains. For access, among all groups across VISNs, the average percentage disparities was 35.6%; the average percentage advantages was 11.7%. For person‐centered care, the average percentage disparities was 14.0%; the average percentage advantages was 35.4%. For care coordination, the average percentage disparities was 14.3%; the average percentage advantages was 40.8%.

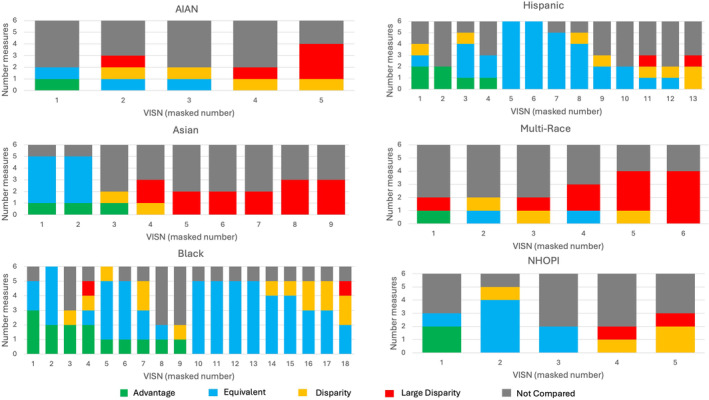

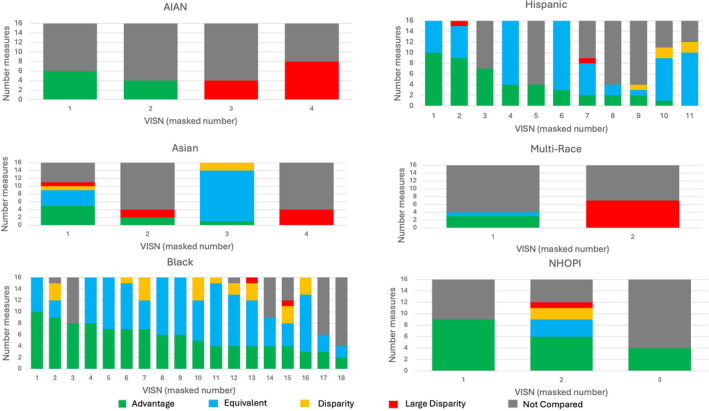

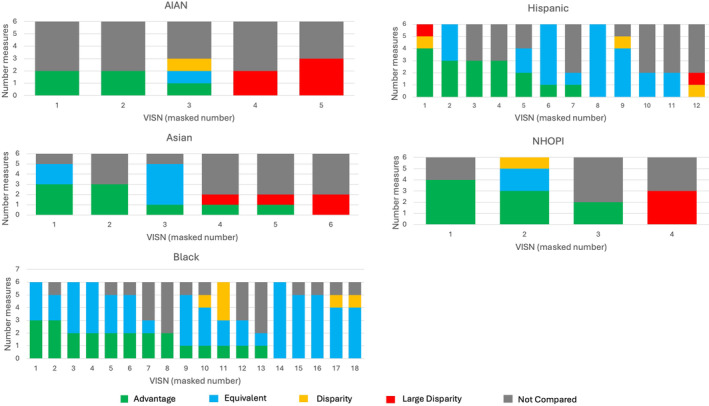

In each domain, AIAN and Multi‐Race groups, and in the access domain the Asian group showed disparities or large disparities on the highest number/proportion of eligible measures (Table 2, Figures 1, 2, 3). NHOPI groups showed disparities on a higher proportion of eligible comparisons for access, but advantages on a higher proportion for person‐centered care and care coordination. Black and Hispanic groups generally showed equivalence or advantages on higher proportions of comparisons, though this trend was less pronounced in the access domain (Table 2, Figures 1, 2, 3). In VISNs by domain in which Black and Hispanic groups could be compared, there was one VISN in the access domain that showed a relatively high proportion of disparities for both groups (Supplemental Figure 4). Otherwise, most comparisons indicated equivalence or advantages for both groups in individual VISNs (Supplemental Figures 4–6).

FIGURE 1.

Number of patient experience measures in the domain of access that are advantages, equivalent, disparity, or large disparity (≥25% relative difference) for minoritized compared to White group, adjusted for age and sex, by masked VISN. VISNs sorted from greatest to smallest number eligible measures representing advantages for minoritized groups. Axis values do not correspond with VISN number. AIAN, American Indian or Alaska Native; NHOPI, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; VISN, Veterans Integrated Service Network.

FIGURE 2.

Number of patient experience measures in the domain of person‐centered care that are advantages, equivalent, disparity, or large disparity (≥25% relative difference) for minoritized compared to White group, adjusted for age and sex, by masked VISN. VISNs sorted from greatest to smallest number eligible measures representing advantages for minoritized groups. Axis values do not correspond with VISN number. AIAN, American Indian or Alaska Native; NHOPI, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; VISN, Veterans Integrated Service Network.

FIGURE 3.

Number of patient experience measures in the domain of care coordination that are advantages, equivalent, disparity, or large disparity (≥25% relative difference) for minoritized compared to White group, adjusted for age and sex, by masked VISN. VISNs sorted from greatest to smallest number eligible measures representing advantages for minoritized groups. Axis values do not correspond with VISN number. Multi‐Race not included as no VISN had minimum number of adequately powered comparisons to be included in the analysis. AIAN, American Indian or Alaska Native; NHOPI, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; VISN, Veterans Integrated Service Network.

3.3. Sensitivity analysis

When highest educational attainment and self‐rated physical health were added as covariates into the models, there was minimal change in the primary findings for patient experience overall and by domain (Supplemental Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study among VA users, we found that there was notable VISN‐level variation in differences in patient experience measures between minoritized groups and White individuals. In some VISNs, the proportion of eligible comparisons that revealed disparities was minimal whereas in others, disparities were revealed in half or more. For each racial and ethnic group, there was substantial variation by VISN in the proportion of eligible comparisons that revealed disparities, ranging from none to all. Black and Hispanic groups, the two largest minoritized groups, generally had more VISNs in which most comparisons were equivalent or an advantage. These patterns were largely held across and within patient experience domains. Overall, our findings present a nuanced understanding of VISN‐level differences by race and ethnicity in patient experience.

To our knowledge, this is among the first studies to investigate regional variation in the VA, which is naturally divided by region into VISNs, of differences in patient experience by race and ethnicity. One study performed using VA SHEP data found that state and county market factors, such as population proportion with employer‐sponsored insurance, household median income, and Veteran unemployment rate, were associated with patient experience, specifically in the provider–patient communication domain (elements of which correspond with measures in our analysis in the person‐centered care domain). 35 However, this study did not assess the associations of these factors with racial and ethnic differences in patient experience.

Prior studies have assessed geographic variation in racial and ethnic differences in patient experience outside the VA. In a county‐level analysis of Black‐White disparities in patient experiences of access in which authors hypothesized that geographic factors related to structural racism (proportion of low‐income residents, racial segregation, and poverty segregation) would be associated with disparities, researchers found that Black‐White disparities were smaller in counties with higher‐than‐average patient experience, but that disparities were not associated with poverty or segregation measures. 12 Similar to these results, we found that patient experiences were more favorable for Black patients in VISNs where the overall proportion of disparities for all minoritized groups was lower. Another study that sought to determine if racial and ethnic differences in patient experience differed by urban/rural status of residence, found that disparities did not typically differ by urban/rural residence, except for AIAN patients in the patient experience measure of “getting needed care” (access domain). 15 We did not incorporate regional contextual measures (e.g., percentage poverty, measures of segregation, proportion rural, area deprivation index) or measures of urban/rural status to determine if these were associated with magnitudes of differences. This would be a key direction for further research to determine factors that contribute to regional variation in differences.

Our findings overall point toward equivalent or better patient experience for Black and Hispanic compared to White individuals. This remained true across most VISNs. Similarly, in the National Veteran Health Equity Report, nationally aggregated and age‐stratified patient experiences for Black and Hispanic were mostly equivalent or favored an advantage in the person‐centered care and care coordination domains. 18 For access to care, Black and Hispanic patients had mostly equivalent or disparate experiences, especially in older age groups. 18 This is consistent with a prior study performed by Zickmund et al. which found few qualitative differences in Black/White and Hispanic/White patient satisfaction after interviews with over 1000 Veterans. 24

While no prior published literature has directly assessed regional racial and ethnic differences in patient experience in the VA, studies by Hausmann et al. found Black and Hispanic patients generally had a greater magnitude in disparities in patient experience compared to White patients between facilities compared to within facilities. 20 , 21 Presumably these differences in differences reflect regional variation in patient experience. It should be noted that some of the prior literature on racial and ethnic differences in patient experience in the primary care setting predates the transition of VA primary care to Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), the VA's model for the patient‐centered medical home. 40 Though this model could potentially contribute toward narrowing in disparities in patient experience across and within VISNs, a prior assessment found persistence of racial and ethnic disparities for measures of quality (chronic disease control). 41

Racial and ethnic groups with smaller representation in the VA, namely AIAN, Asian, Multi‐Race, and NHOPI groups, generally reported more disparities in patient experience than White patients. This study is among the first to characterize patient experiences for these groups in the VA and the first to our knowledge to examine regional variations in differences. The National Veteran Health Equity Report demonstrated that these groups nationally had equivalent or worse patient experiences than White individuals. 18 Since these groups have lower representation overall, it is possible that reduced exposure to these groups among VA clinicians and staff members results in a decreased degree of cultural humility 42 toward these groups. Prior studies pertaining to racial and ethnic differences in patient experience in the VA have tended to aggregate these groups in an “Other” race or ethnicity category or not reported findings from these groups. 20 , 21 , 22 , 24 Our findings lend evidence to the importance of fully characterizing the experience of these groups and disaggregating racial and ethnic data where feasible. 43

There are several possible explanations for the observed regional variation in racial and ethnic patient experience differences. First, it may be related to racial and ethnic representation within each VISN. Presumably in VISNs with more diverse patient populations and workforces, clinicians and staff may have greater cultural humility. 42 , 44 However, a prior study found that at VA facilities with more Black or Hispanic patients, these groups reported less favorable experiences. 21 Another potential explanation is that geographic differences in factors related to structural racism that vary by VISN, including socioeconomic and demographic factors, such as percentage population in poverty, rurality, economic opportunity, segregation, and home ownership, contribute to these differences. Given VA's use of care in the community to supplement on‐site delivery of VA care, it is possible that minoritized groups that reside in economically disadvantaged areas have lower quality patient experience than those living in higher income areas due to insufficient access to high‐quality community medical care, poor infrastructure limiting access, and limited funding of overburdened healthcare systems. 45 Nationally, lower SES Veterans report worse patient experience, though there were no clear differences for rural compared to urban Veterans. 18 Prior literature has not clearly demonstrated associations between the factors above and racial and ethnic differences in patient experience, 12 , 15 though other studies have suggested that individuals with lower SES 46 , 47 , 48 and residing in rural areas 49 , 50 have lower ratings of patient experience. It is also possible that regional variations in workforce diversity contribute to these findings. Theoretically, areas with greater workforce diversity could be lower in disparities due to greater delivery of culturally informed care. For example, a recent study found there was an estimated one‐month survival increase for every 10% increase in county‐level Black representation among primary care physicians. 51 Finally, differences may be related to regional variation in availability of non‐VA care, after the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability and VA MISSION Acts. 52 A recent study found substantial VISN‐level variation in appointment wait times for VA and non‐VA care. 31 If minoritized groups had greater representation in VISNs with longer average appointment wait times, and longer times relative to community care access, this could affect perceptions of patient experience. Future research should examine if workforce diversity and use of non‐VA care impact racial and ethnic differences in patient experience with VA care.

This study demonstrates geographic nuance in racial and ethnic differences in patient experience for Veterans. As a high reliability organization and learning health system, 53 the VA must go beyond characterizing these differences toward reasonable strategies to mitigate disparities. To move toward achieving this, in partnership with the VA Office of Health Equity, the VA is planning to make available a patient experience equity dashboard that will allow VA leaders to view reported differences in patient experience at the VISN level. This will operate similarly to the Primary Care Equity Dashboard, a tool that allows VA facilities to track racial and ethnic differences in quality measures. 54 The tool will be accessible at a VA SharePoint site.

VISN leaders could use this tool to reveal if minoritized groups in their respective VISN show disparities in patient experience and if so, in which specific domains. They could then allocate operational resources accordingly to address these disparities. Additionally, VA researchers could use this dashboard to identify lower‐performing VISNs and further study factors that might contribute to these differences. Researchers could also use the dashboard to identify high‐performing VISNs and examine factors that contribute to their success in achieving parity. The VA could also use these findings to develop programs that incentivize VISNs to minimize disparities in patient experience, similar to strategies used outside VA. 55 This would contribute to the VA becoming a healthcare system that provides a consistently positive patient experience for Veterans of all racial and ethnic backgrounds.

4.1. Limitations

We acknowledge the following limitations to this study. First, we used a meaningful difference criterion of at least 10% relative difference in patient experience between minoritized and White groups, as based on the approach of AHRQ 38 and the National Veteran Health Equity Report, 18 a power criterion to determine which measures were eligible to be reported, and a minimum of five adequately powered measures to summarize VISN‐level differences in patient experience for each minoritized group. Adjustments to these criteria and changes to the number of measures included (or excluded) may lead to changes in the conclusions of our findings. Second, the overall survey response rate was 38%, similar to other studies that use SHEP 20 , 21 and CAHPS 56 data. This could contribute to non‐response bias, especially if there was differential lower response in minoritized groups, which we cannot determine from this dataset. We attempted to account for this by incorporating non‐response weights in our analysis. Third, we did not account for patient experience in healthcare received outside the VA, including for Veterans dually enrolled in Medicare 57 , 58 or those who needed specialized care not available at the VA. Patient experience with non‐VA care may affect perceptions of VA‐based care if this is used as a comparison by Veterans. This could confound the relationship between race, ethnicity, and patient experience if use of non‐VA care differs by race and ethnicity. 59 Fourth, by nature of using SHEP data, the sampling frame by definition included active VA users with a least one contact with primary care in the previous 10 months. Therefore, the experience of these users may not be generalizable to all VA enrollees, including those with less frequent or no VA‐based healthcare contact.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In our study, we found VISN‐level variation in racial and ethnic differences in patient experience, with unique patterns for minoritized groups, including groups with lower representation in the VA. Generally, Black and Hispanic groups had more favorable patient experiences compared to AIAN, Asian, Multi‐Race, and NHOPI groups within VISNs. These findings carry VA policy implications as they demonstrate that efforts to improve patient experience for minoritized groups should be tailored accordingly with VISN‐level assessments of these differences. Our findings can also guide researchers toward understanding factors that contribute to negative and positive patient experiences for minoritized groups. A planned patient experience VISN equity dashboard will allow VA administrators to monitor these differences and facilitate these equity‐promoting efforts.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the VHA Office of Health Equity and VHA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) through grant no. PEC‐15‐239 to the Health Equity‐QUERI National Partnered Evaluation Center, and by VA HSR grant no. IIR‐17‐189. External Peer Review Program (EPRP) data and SHEP‐PCMH data were obtained through a data use agreement with the VHA Office of Quality and Patient Safety–Analytics and Performance Integration (QPS‐API 10A8). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Shannon EM, Jones KT, Moy E, Steers WN, Toyama J, Washington DL. Evaluation of regional variation in racial and ethnic differences in patient experience among Veterans Health Administration primary care users. Health Serv Res. 2024;59(Suppl. 2):e14328. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14328

[Correction added on 7 June 2024, after first online publication: the Funding information section has been corrected.]

[Correction added on 14 October 2024, after first online publication: The copyright line was changed.]

REFERENCES

- 1. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201‐203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1211775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oben P. Understanding the patient experience: a conceptual framework. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(6):906‐910. doi: 10.1177/2374373520951672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta‐analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826‐834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405‐411. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Augustine MR, Nelson KM, Fihn SD, Wong ES. Patient‐reported access in the patient‐centered medical home and avoidable hospitalizations: an observational analysis of the veterans health administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1546‐1553. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05060-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41‐48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(2):188‐195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.900597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haviland AM, Elliott MN, Weech‐Maldonado R, Hambarsoomian K, Orr N, Hays RD. Racial/ethnic disparities in Medicare part D experiences. Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S40‐S47. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182610aa5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weech‐Maldonado R, Morales LS, Elliott M, Spritzer K, Marshall G, Hays RD. Race/ethnicity, language, and patients' assessments of care in Medicaid managed care. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):789‐808. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453‐1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fenton AT, Burkhart Q, Weech‐Maldonado R, et al. Geographic context of black‐white disparities in Medicare CAHPS patient experience measures. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(Suppl 1):275‐286. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nguyen KH, Wilson IB, Wallack AR, Trivedi AN. Racial and ethnic disparities in patient experience of care among nonelderly Medicaid managed care enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(2):256‐264. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hswen Y, Hawkins JB, Sewalk K, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in patient experiences in the United States: 4‐year content analysis of twitter. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e17048. doi: 10.2196/17048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martino SC, Mathews M, Agniel D, et al. National racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in experiences with health care among adult Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(Suppl 1):287‐296. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liao L, Chung S, Altamirano J, et al. The association between Asian patient race/ethnicity and lower satisfaction scores. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):678. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05534-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ngo‐Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Phillips RS. Asian Americans' reports of their health care experiences. Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):111‐119. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30143.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Washington DL. National Veteran Health Equity Report 2021. Focus on veterans health administration patient experience and health care quality. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones AL, Mor MK, Cashy JP, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in primary care experiences in patient‐centered medical homes among veterans with mental health and substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1435‐1443. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3776-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hausmann LR, Gao S, Mor MK, Schaefer JH Jr, Fine MJ. Understanding racial and ethnic differences in patient experiences with outpatient health care in veterans affairs medical centers. Med Care. 2013;51(6):532‐539. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318287d6e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hausmann LR, Gao S, Mor MK, Schaefer JH Jr, Fine MJ. Patterns of sex and racial/ethnic differences in patient health care experiences in US veterans affairs hospitals. Med Care. 2014;52(4):328‐335. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zickmund SL, Burkitt KH, Gao S, et al. Racial differences in satisfaction with VA health care: a mixed methods pilot study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(3):317‐329. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0075-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jones AL, Hanusa BH, Appelt CJ, Haas GL, Gordon AJ, Hausmann LR. Racial differences in Veterans' satisfaction with addiction treatment services. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):383‐390. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zickmund SL, Burkitt KH, Gao S, et al. Racial, ethnic, and gender equity in veteran satisfaction with health Care in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):305‐331. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4221-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS. Geographic variation in health care and the problem of measuring racial disparities. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48(1 Suppl):S42‐S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fisher ES, Goodman DC, Chandra A. Regional and Racial Variation in Health Care among Medicare Beneficiaries: A Brief Report of the Dartmouth Atlas Project. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goodman DC, Brownlee S, Chang CH, Fisher ES. Regional and Racial Variation in Primary Care and the Quality of Care among Medicare Beneficiaries: A Report of the Dartmouth Atlas Project. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skinner J, Weinstein JN, Sporer SM, Wennberg JE. Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in rates of knee arthroplasty among Medicare patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(14):1350‐1359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dai D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late‐stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place. 2010;16(5):1038‐1052. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong MS, Steers WN, Hoggatt KJ, Ziaeian B, Washington DL. Relationship of neighborhood social determinants of health on racial/ethnic mortality disparities in US veterans‐mediation and moderating effects. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(Suppl 2):851‐862. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Feyman Y, Asfaw DA, Griffith KN. Geographic variation in appointment wait times for US military veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2228783. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Berkowitz TSZ, et al. Geographic variation in obesity, behavioral treatment, and bariatric surgery for veterans. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(1):161‐165. doi: 10.1002/oby.22350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Davis M, Snider MJE, Hunt KJ, Medunjanin D, Neelon B, Maa AY. Geographic variation in diabetic retinopathy screening within the veterans health administration. Prim Care Diabetes. 2023;17:429‐435. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2023.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Joo MJ, Lee TA, Weiss KB. Geographic variation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation rates. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1560‐1565. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0354-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Minegishi T, Young GJ, Madison KM, Pizer SD. Regional market factors and patient experience in primary care. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(10):438‐443. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2020.88502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shannon EM, Steers WN, Washington DL. Investigation of the role of perceived access to primary care in mediating and moderating racial and ethnic disparities in chronic disease control in the veterans health administration. Health Serv Res. 2024;59(1):e14260. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) . US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated April 23, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023 https://www.herc.research.va.gov/include/page.asp?id=omop

- 38. 2022 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, Appendixes. 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/2022qdr-appendix-combined.pdf [PubMed]

- 39. Instructions of Analyzing Data from CAHPS Surveys . Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality. Updated June 1, 2017. Accessed February 17, 2024 https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/cahps/surveys‐guidance/helpful‐resources/analysis/2015‐instructions‐for‐analyzing‐data.pdf

- 40. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient‐centered medical home in the veterans health administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263‐e272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Washington DL, Steers WN, Huynh AK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities persist At veterans health administration patient‐centered medical homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1086‐1094. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lekas HM, Pahl K, Fuller LC. Rethinking cultural competence: shifting to cultural humility. Health Serv Insights. 2020;13:1178632920970580. doi: 10.1177/1178632920970580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peterson K, Anderson J, Boundy E, Ferguson L, McCleery E, Waldrip K. Mortality disparities in racial/ethnic minority groups in the veterans health administration: an evidence review and map. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):e1‐e11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nair L, Adetayo OA. Cultural competence and ethnic diversity in healthcare. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7(5):e2219. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fiscella K, Williams DR. Health disparities based on socioeconomic inequities: implications for urban health care. Acad Med. 2004;79(12):1139‐1147. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200412000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arpey NC, Gaglioti AH, Rosenbaum ME. How socioeconomic status affects patient perceptions of health care: a qualitative study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8(3):169‐175. doi: 10.1177/2150131917697439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roberts BW, Puri NK, Trzeciak CJ, Mazzarelli AJ, Trzeciak S. Socioeconomic, racial and ethnic differences in patient experience of clinician empathy: results of a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0247259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Okunrintemi V, Khera R, Spatz ES, et al. Association of income disparities with patient‐reported healthcare experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):884‐892. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04848-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pandit AA, Patil NN, Mostafa M, Kamel M, Halpern MT, Li C. Rural‐urban disparities in patient care experiences among prostate cancer survivors: a SEER‐CAHPS study. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(7). doi: 10.3390/cancers15071939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kang YS, Tzeng HM, Zhang T. Rural disparities in hospital patient satisfaction: multilevel analysis of the Massachusetts AHA, SID, and HCAHPS data. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(4):607‐614. doi: 10.1177/2374373519862933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Snyder JE, Upton RD, Hassett TC, Lee H, Nouri Z, Dill M. Black representation in the primary care physician workforce and its association with population life expectancy and mortality rates in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e236687. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stroupe KT, Martinez R, Hogan TP, et al. Experiences with the Veterans' choice program. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2141‐2149. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05224-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moy E, Hausmann LRM, Clancy CM. From HRO to HERO: making health equity a core system capability. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37(1):81‐83. doi: 10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Primary Care Equity Dashboard . VA HSR. Updated February 6, 2023. Accessed October 19, 2023 https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/impacts/equity_dashboard.cfm

- 55. Elliott MN, Beckett MK, Lehrman WG, et al. Understanding the role played by Medicare's patient experience points system in hospital reimbursement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1673‐1680. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Elliott MN, Adams JL, Klein DJ, et al. Patient‐reported care coordination is associated with better performance on clinical care measures. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(12):3665‐3671. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07122-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu CF, Chapko M, Bryson CL, et al. Use of outpatient care in veterans health administration and Medicare among veterans receiving primary care in community‐based and hospital outpatient clinics. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(5 Pt 1):1268‐1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01123.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu CF, Manning WG, Burgess JF Jr, et al. Reliance on veterans affairs outpatient care by Medicare‐eligible veterans. Med Care. 2011;49(10):911‐917. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822396c5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Washington DL, Villa V, Brown A, Damron‐Rodriguez J, Harada N. Racial/ethnic variations in veterans' ambulatory care use. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2231‐2237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting information.