Abstract

CRISPR-Cas9 editing triggers activation of the TP53-p21 pathway, but the impacts of different editing components and delivery methods have not been fully explored. In this study, we introduce a p21-mNeonGreen reporter iPSC line to monitor TP53-p21 pathway activation. This reporter enables dynamic tracking of p21 expression via flow cytometry, revealing a strong correlation between p21 expression and indel frequencies, and highlighting its utility in guide RNA screening. Our findings show that p21 activation is significantly more pronounced with double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) or adeno-associated viral vectors (AAVs) compared to their single-stranded counterparts. Lentiviral vectors (LVs) and integrase-defective lentiviral vectors induce notably lower p21 expression than AAVs, suggesting their suitability for gene therapy in sensitive cells such as hematopoietic stem cells or immune cells. Additionally, specific viral promoters like SFFV significantly amplify p21 activation, emphasizing the critical role of promoter selection in vector development. Thus, the p21-mNeonGreen reporter iPSC line is a valuable tool for assessing the potential adverse effects of gene editing methodologies and vectors.

Highlights Established a p21-mNeonGreen reporter iPSC line to track activation of the TP53-p21 pathway.

Found a direct correlation between p21-mNeonGreen expression and indel frequencies, aiding in gRNA screening.

Showed that LVs are preferable over AAVs for certain cells due to lower p21 activation, with viral promoter choice impacting p21 response.

Keywords: CRISPR, fluorescent protein reporter genes, gene therapy, induced pluripotent stem cells, lentiviral vector, p53, recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV), P21, CRISPR-Cas9, iPSC

Sun et al. develop a p21-mNeonGreen reporter iPSC line to dynamically monitor TP53-p21 pathway activation post-CRISPR-Cas9 editing. Their findings reveal how editing components and delivery methods affect p21 activation, offering insights for optimizing gene therapy protocols to enhance safety and efficacy.

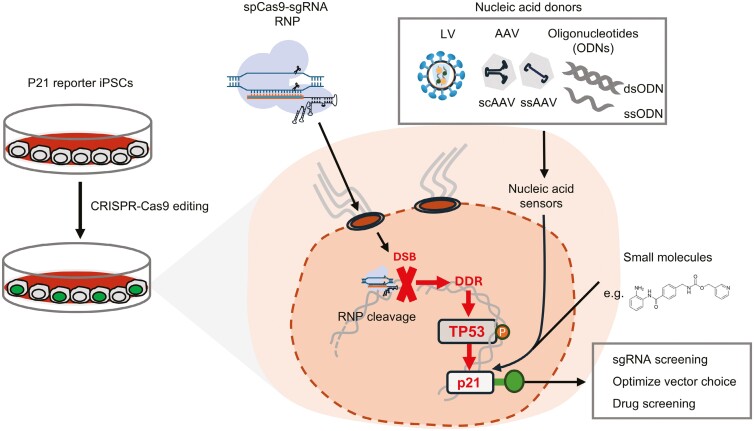

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Significant statement.

This study introduces a fluorescently labeled induced pluripotent stem cell line (iPSC line) to monitor the p21 response against nucleofecting CRISPR-Cas9 RNPs, introducing viral vectors (AAV, LV), oligonucleotides, or small molecules. The findings reveal that AAV is more therapeutic promising than LV for inducing less p21 response. The p21 reporter iPSC line may also serve as an efficient tool for inferring indel frequency and the high-throughput screening of sgRNAs.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized gene editing, allowing for precise genomic alterations through targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs).1 Despite its transformative potential, the activation of the TP53-p21 pathway by DSBs poses significant challenges, such as increased mutagenic risks and reduced efficiency of homology-directed repair (HDR).2,3 These issues compromise the safety and efficacy of gene therapies, especially those based on induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), by impacting editing outcomes and cellular integrity.

Moreover, the role of p21 in cell fate post-stress is highly context-dependent. High levels of p21 expression shortly after cellular stress often signify a compromised long-term proliferation potential in iPSCs. Conversely, a lower initial p21 expression may indicate a more favorable prognosis for cell proliferation and stability, highlighting its dual role in protecting against DNA damage and potentially hampering cellular repair and regeneration processes.4 The dynamic of P21 expression also sets a timeframe for the immune system to clear damaged cells, possibly reducing the proliferation potential of edited cells.5

Addressing p21 activation is essential for advancing stem cell-based gene therapy and gene editing applications. To this end, we developed an mNeonGreen-tagged p21 reporter iPSC line using a previously reported double-cut HDR knock-in strategy.6 This line allows for a detailed analysis of how various components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, including RNP complexes, synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs), adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors, lentiviral vectors (LVs), and specific small molecules, influence p21 activation. By providing a fluorescent indicator of p21 expression in real-time, this reporter line offers valuable insights into the DNA damage response triggered by gene editing tools, facilitating the optimization of CRISPR-Cas9 editing strategies for enhanced clinical safety and efficacy.

Experimental procedures

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further inquiries and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Xiaobing Zhang (zhangxbhk@gmail.com).

Materials availability

Access to the p21-mNeonGreen reporter iPSCs is subject to certain limitations due to the absence of an external centralized repository for distribution and the need to preserve our stock. Nevertheless, we are open to sharing the p21-mNeonGreen reporter iPSCs, with the requester bearing a reasonable fee for processing and shipping.

Guide RNAs

The development of guide RNAs (gRNAs) was meticulously planned using the CHOPCHOP tool, a well-regarded platform for optimizing gRNA design to maximize specificity and efficiency in genome editing.7 The chosen gRNA sequences were synthesized as crRNA and tracrRNA duplexes by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), with the details outlined in Table S1.

For the construction of sgRNA plasmid vectors, we adhered to protocols previously established in our research.8 These protocols involved inserting the gRNA sequences into vectors equipped with a U6 promoter to enhance sgRNA expression following transfection. These constructs underwent rigorous quality control, including restriction enzyme digestion and Sanger sequencing, to confirm the accuracy of the gRNA sequences and the integrity of the plasmid backbones.

Construction of double-cut HDR donor plasmid

The process for constructing double-cut HDR donor plasmids is rooted in our previously established protocols.6 The HDR donor sequences were generated through PCR amplification, featuring homology arms tailored to the target gene and sgDocut recognition sites complete with protospacer adjacent motifs. Subsequently, these HDR donor fragments and the pU6-sgDocut components were seamlessly integrated into a plasmid vector using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Kit.

A comprehensive verification strategy was employed to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the plasmid sequences. This involved a dual approach, utilizing the precision of traditional Sanger sequencing (provided by Tsingke) alongside the depth of long-read Nanopore sequencing (conducted by GenoStarBio). This rigorous verification process guaranteed our HDR plasmids’ structural and sequence integrity.

Lentiviral vector construction and production

In this study, we employed 3 distinct lentiviral vectors—pRSC-CAG-Crimson-Wpre, pRSC-SFFV-Crimson-Wpre, and pRSC-EF1-Crimson-Wpre—each engineered with different promoters (EF1, CAG, or SFFV) to drive the expression of the Crimson fluorescence gene. The first step involved the PCR amplification of the Crimson gene and promoter segments from existing in-house plasmids, utilizing KAPA HiFi polymerase. These purified fragments were then integrated into the lentiviral vector backbones using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Kit for exact cloning.

To confirm the accuracy and integrity of each construct, a thorough validation process was performed, which included both Sanger sequencing and Nanopore sequencing (conducted by GenoStarBio), to verify the correctness of the vector sequences. Following confirmation, high-quality clones were cultivated in CircleGrow Media (MP Biomedicals) to produce the necessary volume, and the plasmid DNA was then purified using the Endo-Free Plasmid Maxi Kits (Qiagen), achieving a high purity level crucial for effective transfection.

The production of lentiviruses followed the established calcium phosphate precipitation method described in our prior work.6 The viral particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 6000 g for 24 hours at 4 °C, yielding viral titers in the range of 2-10 × 107/mL. The biological viral titers were accurately quantified through the transduction of HT1080 cells and subsequent FACS analysis.

For the production of IDLV, the helper plasmid was substituted with the DeltaR8.74 (D64V) variant, followed by the same packaging protocol with LV.

Adeno-associated vectors and AAV6 packaging

For the construction of adeno-associated virus (AAV) expression vectors, we utilized plasmids containing AAV2’s inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) as the backbone, adhering to protocols established in our previous research.8 The cloning and verification processes for AAV plasmids mirrored those employed for the lentiviral vectors.

AAV6 packaging was carried out using a triple plasmid transfection protocol in HEK293T cells, which were brought to 80%-90% confluency before transfection. The transfection complex consisted of PEI (polyethylenimine) MAX 40K and the AAV plasmid at a 2:1 mass ratio, incorporating pAAV-Helper, pR2C6 (AAV6 capsid vector), and the pAAV (transgene vector construct) in a 2:1:1 ratio. For each 15-cm culture dish, 40 μg of plasmid DNA was utilized. Five days post-transfection, the supernatant was treated with 500 mM NaCl and 20 U/mL Benzonase to release viral particles, followed by clarification and sterilization.

The viral particles were then concentrated 20-fold using Minimate (PALL) tangential flow filtration and further purified by iodixanol gradient centrifugation. The final AAV products were dialyzed against PBS–0.01% Pluronic F68 to remove iodixanol, employing centrifugal concentrators with a 100 kDa MWCO. AAV6 titers were precisely quantified by qPCR, utilizing vector-specific primers for amplicon sequencing and additional primers to assess plasmid contamination, which was less than 5%. Further validation of titers was performed through transduction of human cells and subsequent qPCR analysis, using β-Actin as an internal reference, ensuring the accurate determination of viral concentrations for subsequent experimental use.

Oligonucleotides

In our study, we explored the impact of single-stranded oligonucleotides (ssODNs) of varying lengths (22nt, 26nt, 28nt, 34nt, 39nt) on p21 activation. These ssODNs were designed with phosphorothioate modifications at the first 2 bonds of each end to enhance stability against exonuclease degradation, while minimizing the bias introduced by chemical modifications. The ssODNs were procured from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), ensuring high quality and consistency across all experimental conditions. To generate double-stranded oligonucleotides (dsODNs), these ssODNs and their complementary strands were annealed using a standard protocol: heating to 95 °C for 10 minutes and then allowing to cool gradually to room temperature.

To assess their influence on p21 expression, 1 µg of each ssODN or dsODN variant was introduced into our p21 reporter iPSC line via nucleofection. This direct comparison enabled us to evaluate the effect of ssODN and dsODN lengths on p21 activation without interfering with other gene editing elements.

Human iPSC Culture and nucleofection

Wild-type iPSCs, previously characterized,9 were cultured under feeder-free conditions on tissue-culture-treated 6-well plates (BD) and coated with 1% Matrigel (Corning). Maintenance was in Essential 8 Medium (Gibco Technologies), with daily medium changes to ensure optimal growth conditions. The cultures were kept in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. To improve cell survival, especially after thawing or single-cell preparation using Accutase, 10 µM of the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 was added to the medium on the day following thawing or passaging. For cell passaging, iPSCs were dissociated into single cell by Accuase, and seeded into pre-coated TC-6 well with a density of 0.1 M/ml.

For nucleofection, iPSCs at 40–60% confluency were selected to optimize cell survival post-transfection. Cells were dissociated into a single-cell suspension using Accutase, and approximately 0.8–1 × 106 cells were collected by centrifugation at 200 g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet resuspended in 70 µL of Amaxa Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit 2 solution (Lonza), which consists of 57.4 µL of nucleofector solution and 12.6 µL of supplement, along with the specific test components for each experiment. Electroporation used program B-016, followed by a brief incubation at 37 °C for around 5 minutes to aid cell recovery. When electroporating with donor template and editing plasmids, 1 µg of BCL-XL plasmid was also used per reaction to improve cell viability.9

MMC assay to mimic DNA damage

To evaluate the p21 reporter cell line’s responsiveness to DNA damage and subsequent TP53-p21 pathway activation, we utilized Mitomycin-C (MMC), a well-established DNA crosslinking agent. For this assay, we treated the positive control group with a concentration of 10 µg/mL MMC in the culture medium. The MMC was left to incubate with the cells for 4 hours—a carefully calibrated period designed to induce DNA damage while minimizing cytotoxic effects effectively. The ROCK inhibitor Y27632, known for its cytoprotective properties, was administered to both the MMC-treated and control groups the following day to support cell recovery and mitigate the stress induced by MMC exposure. This strategy aimed to enhance cell viability during and after the stress response, ensuring the integrity of the assay.

RNP complex formation

According to the manufacturer’s guidelines, the formation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes began with annealing tracrRNAs and crRNAs, supplied by IDT. Both tracrRNA and crRNA were initially dissolved in TE buffer to achieve a concentration of 200 µM each. For the annealing process, 10 µL of crRNA (200 µM) was mixed with 10 µL of tracrRNA (200 µM), supplemented with 13.5 µL of 5× annealing buffer (Synthego) and 67.5 µL of nuclease-free water. The mixture was then heated at 78 °C for 10 minutes to denature the RNA strands, then cooled to 37 °C for 30 minutes to facilitate annealing, and finally allowed to gradually return to room temperature over 15 minutes to ensure stable complex formation.

The Alt-R SpCas9 Nuclease V3 protein, equipped with a nuclear localization signal, was procured from IDT. To preserve their activity, RNP complexes were assembled immediately before electroporation. This step involved mixing 60 pmol of Cas9 nuclease with 120 pmol of the annealed gRNA, establishing a 2:1 gRNA to Cas9 molar ratio, and incubating at room temperature for 10 minutes. This protocol ensured the formation of active RNP complexes ready for efficient delivery into the target cells.

Small molecules

Our study further explored a range of commercially available small molecules, selected for their potential to either augment CRISPR editing efficacy and precision or due to their original development for cancer treatments, albeit with a noted risk of precipitating drug-induced senescence. This assortment comprised HDAC inhibitors (such as Entinostat, Panobinostat, and SAHA), cell cycle modulators (like Nocodazole, Aphidicolin, and thymidine), and agents involved in DNA repair pathways (including L755507, M3814, Mirin, Scr7, Brefeldin A, and Olaparib). Thymidine was dissolved in nanopure water, while the remainder were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to enhance solubility and stability, subsequently diluted to the appropriate concentrations immediately before application to cultures of p21-mNeonGreen reporter iPSCs. To reduce potential toxicity, the culture medium was replaced 24 hours following the addition of these compounds. The capacity of these molecules to induce p21 expression was assessed using FACS analysis at 1 and 2 days post-treatment, shedding light on their effectiveness for enhancing gene editing processes or altering cellular responses to DNA damage. Table S3 contains comprehensive details on the working concentrations and the specific actions of these compounds.

AAV and LV transduction

To investigate the differential effects of adeno-associated virus (AAV) and lentiviral (LV) vector transduction on p21 expression, p21 reporter iPSCs were prepared at 50% to 70% confluency, dissociated into a single-cell suspension using Accutase, and then plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates pre-coated with 1% Matrigel (Corning). This setup ensured optimal cell adhesion and growth. AAV or LV vectors were added to the respective wells in volumes calibrated to achieve the desired multiplicity of infection (MOI), ensuring uniform transduction efficiency across experiments.

For each experimental condition, duplicate wells were designated for FACS analysis at days 1 and 2 post-transduction, allowing for the assessment of p21 expression dynamics in response to viral transduction. To facilitate LV transduction, 0.1% surfactant Synperonic F108 (Sigma) was included in the culture medium before cell seeding, enhancing the infectivity of the viral particles by modifying the cell membrane permeability.

To promote cell survival following transduction, the culture medium for cells transduced with either AAV or LV was supplemented with 10 µM ROCK inhibitor Y27632 on the first day post-transduction. This intervention aimed to mitigate the impact of enzymatic dissociation and the transduction process on cell viability, ensuring the maintenance of a healthy cell population for subsequent analysis.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry was employed to quantify the expression levels of p21-mNeonGreen following treatment of the reporter iPSCs. The analysis was conducted at 24 and 48 hours post-treatment using a BD LSRFortessa X-20 cell analyzer, with a minimum of 10 000 cells acquired per sample to ensure statistical significance. Non-viable cells and doublets were excluded from the analysis through appropriate gating strategies.

The mNeonGreen-positive cell population was identified as indicative of p21 expression, while cells expressing Crimson were recognized as successfully transduced by AAV or LV vectors. The FITC channel was used to enumerate mNeonGreen-positive cells, identifying the proportion exhibiting p21 activation. Concurrently, the APC channel identified Crimson-positive cells, marking successful viral transduction or was otherwise utilized for alternative markers as required.

Control iPSCs not subjected to treatment were included in each batch of analysis to establish baseline levels of p21 expression. This comparison enabled the evaluation of the impact of various treatments on p21 induction. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software, facilitating a detailed examination of p21-mNeonGreen and Crimson fluorescence intensities across experimental conditions.

Fluorescence microscopy analysis

High-resolution fluorescence microscopy was conducted using a Nikon Ti2-U microscope, with image observation through NIS-Elements Viewer 5.21 software. This approach allowed for the capture of both phase-contrast and fluorescent images, providing a comprehensive view of the cellular morphology and the spatial distribution of fluorescence signals. Through this analysis, we could visually confirm the activation of p21 expression and assess the efficiency of viral transduction, enhancing our understanding of the cellular response to various treatments.

Amplicon sequencing for indel frequency analysis

Amplicon sequencing was utilized to assess indel frequencies after CRISPR-mediated genome editing. For this purpose, around 5 × 105 cells were harvested to extract genomic DNA, utilizing the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) with 100 µL of digestion buffer. The DNA purification process involved the addition of Select-a-Size DNA Clean & Concentrator MagBeads (ZYMO Research) in a 1:1 ratio to the lysate, followed by magnetic separation and 2 rounds of washing with 200 µL of 75% ethanol to eliminate contaminants. The purified DNA was then eluted in 20-50 µL of TE buffer.

For PCR amplification, 100 ng of the extracted genomic DNA served as the template. The PCR primers were meticulously designed using Primer3Plus. The amplification process relied on the KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase (Roche Sequencing) and followed a precise thermal cycling protocol: an initial denaturation at 98 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 98 °C for 5 seconds (denaturation), 64 °C for 10 seconds (annealing), and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 seconds. The PCR products were then verified via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. To determine indel frequencies, Sanger sequencing data were analyzed using the ICE tool (Synthego). In instances requiring a more detailed assessment of indel patterns, Illumina sequencing (150 bp paired-end) was employed, offering an extensive overview of the genomic alterations.

Statistics

We conducted our statistical analysis with GraphPad Prism 8 to ensure a thorough and precise examination of the collected data. We calculated P-values to facilitate comparisons across different experimental setups, marking them on the graphs accordingly; “ns” was used to denote non-significant results. Mean values for each group were depicted in dot plots for a clear visual representation of the data. When evaluating differences between 2 specific groups, the Student’s t-test was our method of choice, with the decision between unpaired or paired 2-tailed tests made based on the normality of data distribution and the homogeneity of variances. This method applied to data sets confirmed to have a normal distribution through standard normality testing procedures. For scenarios involving comparisons among more than 2 groups or under varied conditions, we applied either 1-way or 2-way ANOVA tests, the selection of which depended on the structure of the data—whether it was paired/matched or unmatched. To further substantiate the validity and repeatability of our findings, all data presented in this research result from at least three independent experiments, enhancing the credibility and durability of our conclusions.

Results

Construction of a fluorescently labeled p21 reporter iPSC Line

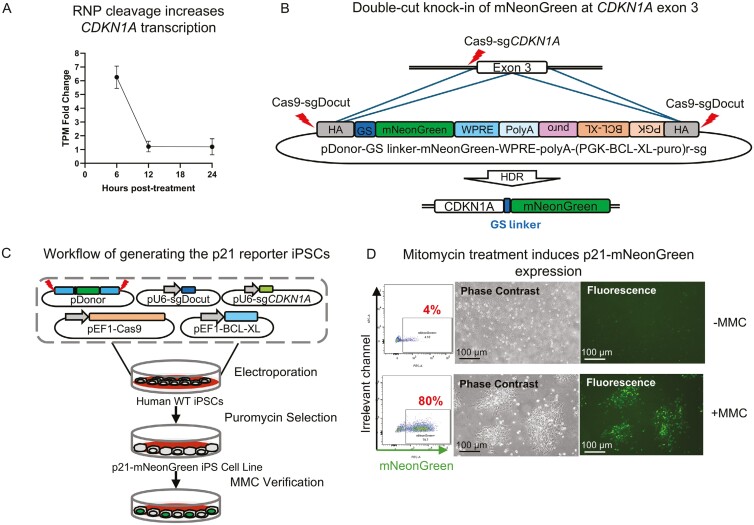

Our exploration into the dynamics of p21 transcription following CRISPR RNP transfection in iPSCs revealed a marked increase in p21 transcription within 6 hours8 (Figure 1A). This pronounced upregulation positions p21 as an early and sensitive marker for CRISPR-induced DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), suggesting its potential utility in reflecting indel frequencies.

Figure 1.

Development and validation of the p21-mNeonGreen Reporter iPSC Line. A. Temporal transcription analysis: DisplaFcys the fold increase in CDKN1A transcript levels at 6, 12, and 24 hours post-CRISPR-Cas9 RNP nucleofection compared to untreated controls, demonstrating an early transcriptional activation of CDKN1A. B. HDR double-cut knock-in strategy: Illustrates the strategy using an HDR donor plasmid (pDonor) with 600 bp homology arms for precise DSB repair at the CDKN1A gene’s exon 3, facilitated by Cas9-sgCDKN1A. This strategy also employs a sgDocut recognition site for exact cutting, a WRPE element for enhanced transcription, and BCL-XL and puromycin resistance genes under the PGK promoter to minimize disruption in expression. mNeonGreen expression is under the control of the CDKN1A promoter post-HDR. C. Development and validation process: Outlines the process involving key components: the double-cut donor plasmid (pDonor-sg), sgRNA plasmid for donor cleavage (pU6-sgDocut), CDKN1A exon 3-targeting gRNA plasmid (pU6-sgCDKN1A), and plasmids for spCas9 and BCL-XL (pEF1-Cas9 and pEF1-BCL-XL), aimed at enhancing iPSC survival post-nucleofection. D. p21-mNeonGreen expression detection: Demonstrates significant activation of the p21 pathway 48 hours post-MMC treatment, as evidenced by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy, confirming the reporter system’s functionality compared to controls.

To leverage p21 as an indicator of genomic integrity, we developed a fluorescently tagged p21 reporter iPSC line using the double-cut HDR knock-in strategy.6 This involved inserting a mNeonGreen fluorescence tag downstream of exon 3 of the CDKN1A gene. The design strategy utilized a donor plasmid with a spCas9-sgDocut recognition site for precise HDR integration, flanked by ~600 bp homology arms (Figure 1B). The resulting configuration allows for simultaneous expression of p21 and mNeonGreen, linked via a GS linker (consisting of 4 repeats of GGGGS),10 enabling real-time monitoring of p21 expression. Additionally, the inclusion of BCL-XL and a puromycin resistance gene, both driven by the PGK promoter, was to enhance iPSC survival without affecting the dynamics of p21 expression9 and to facilitate the enrichment of successfully integrated cells, respectively (Figure 1B).

Following plasmid nucleofection and subsequent puromycin selection, we established a bulk population of p21 reporter iPSCs. The functionality of this reporter line was validated by transient exposure to mitomycin C (MMC),11 hypothesizing that MMC-induced DSBs would lead to TP53-p21 pathway activation, observable as elevated mNeonGreen fluorescence. Indeed, 48 hours post-MMC treatment, fluorescence microscopy confirmed an increase in mNeonGreen signal, reflecting active p21 expression and notable cellular morphological changes (Fig. 1D). The variability in fluorescence intensity across different cells underscored the reporter’s capability to discern nuanced levels of p21 expression. Flow cytometry analysis further confirmed a 20-fold increase in p21-mNeonGreen levels, affirming the system’s effectiveness and sensitivity. Thus, the establishment of the fluorescent p21 reporter iPSC line as a sensitive tool for detecting genomic integrity was successfully demonstrated.

Predicting indel frequency through Early p21-mNeonGreen expression

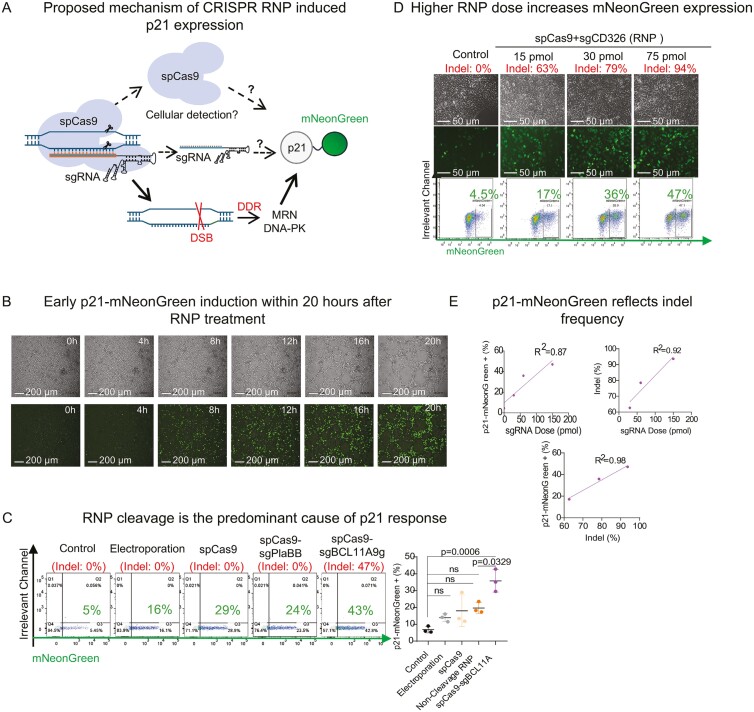

After establishing the p21 reporter iPSC line’s functionality in real-time reflection of p21 expression, we proposed leveraging early p21-mNeonGreen expression levels as predictors of indel frequency. Notably, introducing the Cas9 protein and guide RNAs (gRNAs) might independently initiate p21 expression through unspecified mechanism (Figure 1A), thus complicating the interpretation of p21-mNeonGreen expression levels. Consequently, our focus shifted to discerning how specific components of the CRISPR RNP nucleofection might influence p21-mNeonGreen expression.

We observed rapid expression of p21-mNeonGreen within 20 hours post-RNP transfection (Figure 2B) and persist to 96 hours when achieving indel frequency of 94% (Figure S1). Moreover, our findings suggest that DSBs induced by RNP cleavage were the primary triggers of p21 expression (Figure 2C). While the electroporation procedure itself slightly elevated p21-mNeonGreen expression, the increase was not statistically significant (Figure 2C). Similarly, the introduction of the spCas9 protein, with or without non-targeting sgRNA, did not significantly alter p21-mNeonGreen expression levels, effectively eliminating their potential confounding effects on the correlation between p21-mNeonGreen expression and indel frequency.

Figure 2.

Correlation between p21-mNeonGreen expression and Indel frequency. A. Potential mechanism of RNP induced p21 response: Visualizes how CRISPR RNP components may provoke cellular responses which potentially interact with the p21 regulatory network. The diagram shows RNP-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) initiating a DNA damage response pathway leading to TP53-p21 pathway activation, with black solid arrows indicating this sequence and dotted arrows suggesting gRNA and Cas9’s immune interactions. The resulting p21 upregulation correlates with mNeonGreen fluorescence to visualize gene editing outcomes. B. Temporal expression dynamics: time-lapse analysis demonstrating a marked increase in p21-mNeonGreen expression within 20 hours following spCas9-sgBCL11A9g RNP nucleofection, as captured by fluorescence microscopy. C. Induction analysis: examines factors influencing p21-mNeonGreen expression, with DNA cleavage by the RNP complex as the central trigger. Control conditions, including electroporation with a blank solution, application of 60 pmol spCas9 protein, and sgPlaBB (which targets the plasmid backbone), served to confirm that DSB formation is the primary inducer. The analysis was based on 3 independent replicates with day 2 indel frequency assessed by Sanger sequencing. Statistical relevance was determined by 1-way ANOVA. D and E. Dose–response relationship: Presents the correlation between increasing concentrations of spCas9-sgCD326 RNP and enhanced p21-mNeonGreen expression and indel frequency. Observations were made 48 hours post-nucleofection, with indel frequencies assessed via Sanger sequencing and ICE analysis, illustrating a dose-dependent gene editing effect.

To further explore this relationship, we nucleofected p21 reporter iPSCs with increasing doses of spCas9-sgCD326a RNP, hypothesizing that higher RNP doses would correspond to increased indel frequencies, as reflected by elevated p21-mNeonGreen expression. Two days post-nucleofection, fluorescence microscopy revealed enhanced mNeonGreen expression across all RNP-treated groups. Flow cytometry analysis supported this observation, showing a gradual increase in p21-mNeonGreen expression levels in parallel with a rise in indel frequency as determined by Sanger sequencing (Figure 2D). Despite some discrepancies in numeric data, linear regression analysis confirmed a positive correlation between sgRNA dose, indel frequency, and p21-mNeonGreen expression at CD326 and 3 BCL11A loci, suggesting the feasibility of using mNeonGreen expression as a practical proxy for indel frequency (Figure 2DE, Figures S2, S3). However, notable variability in the percentage of p21-mNeonGreen positive cells among samples with similar indel frequencies across different experimental batches was observed (Figure 2CDE). Yet, it did not detract from the strong correlation between indel frequency and p21-mNeonGreen expression. This finding suggests the utility of the p21-mNeonGreen reporter system in high-throughput screening of effective gRNAs, highlighting that DSBs induced by RNP, rather than the components of the CRISPR-Cas9 editing system, are the predominant triggers for p21 expression.

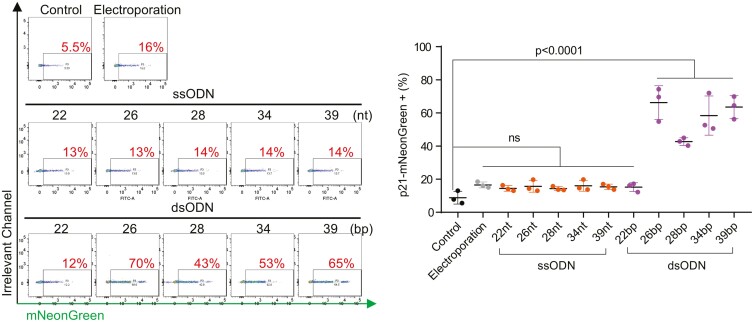

Length-dependent induction of p21 by double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides

To extend the utility of our p21 reporter iPSC line, we delved into the potential of various CRISPR-Cas9 editing components to induce p21 activation. Given that the recognition of cytosolic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) by cytosolic nucleic acid sensors such as IFI16 and cGAS is known to be length-dependent,12,13 we explored whether this mechanism correlates with subsequent p21 expression—a relationship that had yet to be clearly defined.

Our approach involved synthesizing single-stranded oligonucleotides (ssODNs) and double-stranded oligonucleotides (dsODNs) in a range of lengths: 22, 26, 28, 34, and 39 nucleotides (nt) or base pairs (bp) (Table S1). Intriguingly, ssODNs and dsODNs of 22 bp did not elicit any significant p21-mNeonGreen expression compared to the control, whereas dsODNs of lengths ≥26 bp triggered a robust p21 activation. This response was consistent across various experimental replicates, highlighting a critical length threshold for dsODN recognition and p21 pathway activation that lies between 22 and 26 bp (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Length-dependent activation of p21 by dsODNs. Analysis of oligonucleotide-induced p21 activation: evaluates p21-mNeonGreen expression following the introduction of double-stranded (dsODNs) and single-stranded oligonucleotides (ssODNs) of varying lengths into p21 reporter iPSCs. Controls include iPSCs electroporated with a blank solution and untreated cells. The study reveals that dsODNs exceeding 26 base pairs markedly elevate p21 expression, while a dsODN of 22 base pairs and all ssODNs show no significant impact on p21 activation. Measurements were taken from three independent experiments 48 hours post-nucleofection and analyzed using one-way ANOVA for statistical validation.

Taken together, these results illuminate a direct link between the sensing of cytosolic dsDNA by cytosolic sensors and the activation of the p21 regulatory network. Notably, while all dsODNs of lengths ≥26 bp induced p21 expression, no significant difference in the level of p21 activation was observed among these groups, despite their varied lengths. This underscores the existence of a length threshold for dsODN-induced p21 activation, rather than a dose-dependent relationship.

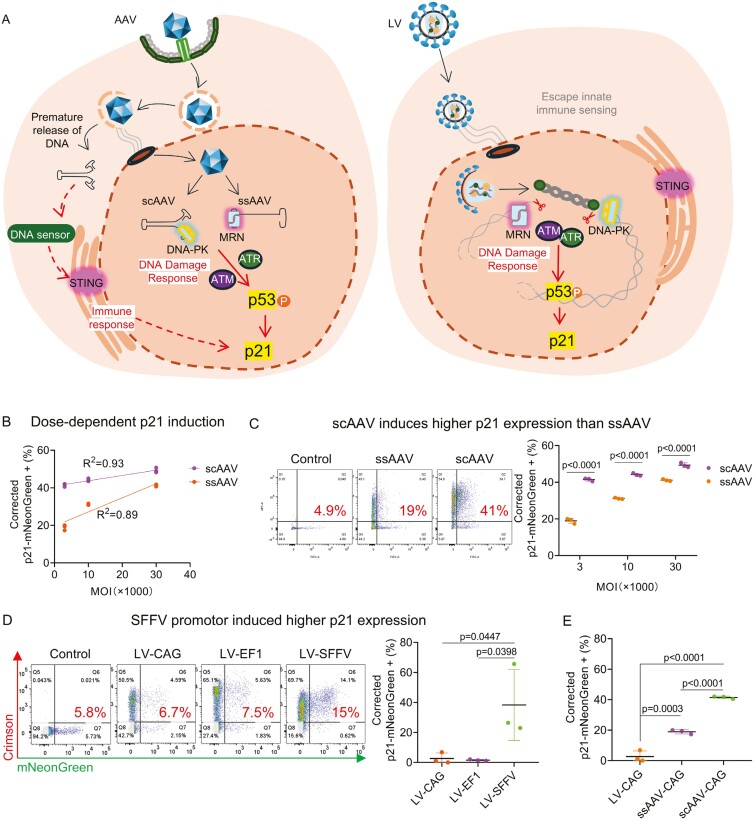

AAV vectors, in particular scAAVs, induce strong p21 expression

AAVs are widely adopted as a vector in gene therapy due to their low immunogenicity.14 However, they have also been reported to induce p53-dependent apoptosis,15-17 partially attributed to the cellular recognition of AAV inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) by classical DNA damage response (DDR) molecules (Figure 4A). To further investigate the context of AAV-induced TP53-p21 activation, we aimed to elucidate the extent of p21 expression triggered by various AAV configurations, specifically comparing self-complementary (sc) and single-stranded (ss) AAV vectors.

Figure 4.

Differential p21 activation induced by viral vectors. (A) Illustration of the cellular sensing against AAV and LV genomic material. Pre-mature released AAV genome is detected by the cytosolic DNA sensors, provoking the cGAS-STING pathway mediated innate immunity, which may intersects with the p53-p21 regulatory network (indicated by dotted arrows). Additionally, DDR molecules like MRN and DNA-PK recognize the AAV ITR region, which may lead to ATM and ATR-mediated p21 response (indicated by solid arrows). LVs may escape innate immune sensing with unspecified mechanism but may still provoke DDR through integrase-dependent mechanism. (B) Demonstrates a strong correlation between AAV MOI and the level of p21-mNeonGreen expression, for both single-stranded (ssAAV) and self-complementary AAV (scAAV) configurations. Data were collected 24 hours post-AAV transduction, with three independent replicates (n = 3) underscoring the consistency of the observed effect. (C) Comparison of p21-mNeonGreen expression levels between scAAV and ssAAV at an MOI of 3000 showing significantly higher expression in cells treated with scAAV. Three independent replicates (n = 3) were statistically validated using Student’s t-test. (D) Lentiviral vectors with the SFFV promoter induces significantly higher p21 expression compared to those with CAG or EF1 promoters. One-way ANOVA was performed on three biological repeats (n = 3). (E) Differential p21 induction by LV, ssAAV, and scAAV. Data compilation was from analyses shown in (C) and (D). (B,C,D,E) Expression level of p21-mNeonGreen were adjusted by basal p21 expression as indicated by untreated reporter iPSCs, and transduction efficiency indicated by the percentage of Crimson-positive population to mitigate bias from culture condition and varying vector uptake, respectively. The resulting parameter was denoted as “Corrected p21-mNeonGreen+ (%).” Corrected p21-mNeonGreen (+)% = [mNeonGreen (+)% - basal p21 expression] * Relative Crimson (+)%. Relative Crimson (+)% = TestN-Crimson(+)% / Test1-Crimson (+)%. Relative Crimson (+)% for Test 1 is “1.”

Employing AAV vectors expressing the Crimson gene under the control of the CAG promoter, we administered varying multiplicities of infection (MOI) levels to examine dose-dependent effects on p21 activation. Our data indicated a clear, dose-dependent increase in p21-mNeonGreen expression across both scAAV and ssAAV constructs (Figure 4B). Furthermore, scAAV induced a significantly higher level of p21-mNeonGreen expression compared to ssAAV, even after adjusting for transduction efficiency and baseline p21 expression (Figure 4C). This finding aligns with previous reports suggesting scAAVs may provoke a more potent cellular detection, thereby inducing higher levels of p21 expression.18-21 The differential response between scAAV and ssAAV highlights the importance of vector design in activating cellular stress pathways. It underscores the need to carefully consider vector types in gene therapy applications to minimize potential adverse responses.

Impact of lentiviral transduction on p21 expression and promoter choice

Lentiviral vectors (LVs) are known for their capacity to achieve stable and enduring gene expression in dividing and non-dividing cells,22 marking them as a staple in gene therapy and research applications. However, introducing LV genomes and viral components into cells may stimulate the host’s innate immunity.16,23 In certain contexts, LVs that avoid innate immune sensing can still elicit a p53 response,24 possibly through integrase-dependent DDR (Figure 4A). This distinction underscores the nuanced interplay between LVs and cellular defense pathways. To gain more insights into the LV-induced p21 response, our study focused on the effects of different promoters used in LV construction on p21 expression levels in transduced cells.

We focused on three promoters commonly employed in LV design—CAG, EF1, and SFFV—to drive the expression of the Crimson fluorescence gene, thereby assessing their impact on p21 activation.25-27 Following the transduction of p21 reporter iPSCs with LVs at a moderate multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1, we observed a significant variation in p21 induction levels. Notably, LVs utilizing the SFFV promoter led to a 5- to 10-fold increase in p21 expression compared to those driven by CAG or EF1 promoters after adjusting for baseline expression levels. This pronounced effect was not attributable to differences in transduction efficiency, as similar percentages of Crimson-positive cells were observed across the groups, indicating that the discrepancies in p21 activation were indeed promoter-dependent (Figure 4D).

These findings highlight the critical role of promoter selection in LV design, particularly in contexts where cellular stress responses, such as the activation of the TP53-p21 pathway, could impact therapeutic outcomes. The SFFV promoter seems to exert a more substantial stress on cells, potentially due to its viral origin and how it engages cellular transcriptional machinery.

AAV induces greater p21 expression compared to LV

In clinical gene therapy, AAV and LV vectors are the most commonly utilized vehicles for delivering genetic material into cells. Their unique properties and mechanisms of entry into host cells lead to distinct interactions with the cellular immune response and DNA damage pathways. Particularly, the premature release of AAV DNA into the cell may trigger a more pronounced cellular response than the RNA genome of LVs, which may have implications for their use in sensitive cell types (Figure 4A). Our comparative analysis aimed to elucidate the differential impact of these vectors on p21 expression under standardized conditions.

To adjust for transduction efficiency to ensure a fair comparison, we utilized CAG promoter-driven vectors in both viral vector platform. The findings were compelling: AAV vectors induced a 5- to 10-fold higher activation of p21 compared to LVs (Figure 4E). This substantial difference underscores the potentially higher cellular stress associated with AAV transduction, as reflected by the elevated p21 response. The analysis accounted for baseline p21 expression levels, ensuring that the observed differences were directly attributable to the vector-induced stress rather than pre-existing conditions in the cells.

Integrase-defective lentiviral vectors (IDLVs) have been specifically developed to mitigate the risk of random insertion-induced mutagenesis, thereby enhancing the safety profile of therapeutic applications.21 In our study, we extended our analysis to evaluate the impact of IDLVs on p21 expression. Our results demonstrated that IDLVs elicited p21 expression levels comparable to those induced by LVs, which remained close to baseline levels (Figure S4). Given that LVs already showed minimal p21-inducing effects, no significant differences were observed in the IDLV group.

These results underscore the therapeutic promise of LVs, especially in contexts where minimizing cellular stress and avoiding activation of the TP53-p21 pathway is crucial. Such scenarios include gene therapy applications targeting hematopoietic stem cells or immune cells, where preserving cellular integrity and functionality is paramount. Our findings advocate for thoughtful consideration of vector choice in gene therapy protocols, suggesting that, in certain cases, LVs might offer a safer alternative to AAVs, particularly with the development of Integrase-Defective Lentiviral Vector (IDLV).28

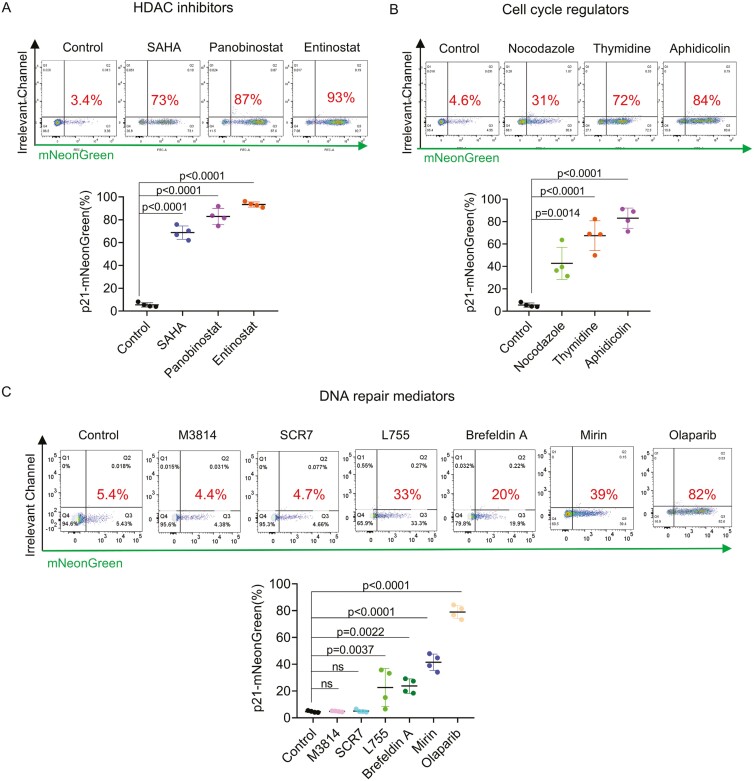

Using the p21 reporter to quantitate the toxicity of small molecules

Small molecules are commonly applied to improve CRISPR editing efficiency and precision, but these compound carries the inherent risk of inducing premature cellular senescence.29 To quantitively assess the drug-induced cytotoxicity, we screened an array of small molecules for their p21 inducing effect with standard dosing, including HDAC inhibitors, cell cycle regulators, and DNA repair mediators.

Despite the reported beneficial effect of HDAC inhibitors on HDR efficiency,30 we observed that Entinostat, Panobinostat, and Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) manifested significant elevation in p21-mNeonGreen expression within 48 hours post-treatment (Fig. 5A, Figure S5), highlighting their pronounced impact of HDAC inhibitors on cellular stress pathways.

Figure 5.

Screening for small molecule-induced toxicity using the p21 Reporter iPSCs. A. HDAC inhibitor toxicity: demonstrates the effect of HDAC inhibitors on p21-mNeonGreen expression in iPSCs. The noted increase in expression suggests these inhibitors’ potency and potential toxicity through p21 pathway modulation. B. Cell cycle regulator impact: evaluates the influence of cell cycle regulators on p21 expression. Changes in p21 levels reflect the potential toxicity and perturbation of cell cycle control by these small molecules. C. DNA repair pathway mediators: analyzes the response of p21-mNeonGreen expression to DNA repair mediators. The variance in expression levels indicates differing degrees of cellular stress and potential toxicity induced by these molecules. Each panel represents the results of treating cultured iPSCs with small molecules at recommended dosages, observed 48 hours after the 24-hour treatment period. Details on the molecules are provided in Table S3. Statistical analysis of expression changes was conducted using 1-way ANOVA to determine significance. Four independent replicates (n = 4) were adopted.

Cell cycle regulators nocodazole, aphidicolin, and thymidine enrich cells at S phase,31,32 and was observed to enhance p21 expression (Figure 5B), aligning with the normal p21 dynamics that peaks in G1-S transition. The p21-mNeonGreen expression level increased on day 2 (Figure S5), possibly due to the time lapse in cell phase synchronization.

Additionally, DNA repair mediators are applied to favor either the NHEJ or the HDR pathway, allowing improved gene editing purity.33-35 Except for the DNA-PK inhibitor M3814 and the DNA ligase IV inhibitor Scr7, most DNA repair mediators were found to prompt an increase in p21 activation, among which, Mirin and other HDR-promoting molecules elicited moderate levels of p21 expression (20%~40%). The PARP1 inhibitor Olaparib, known for its role in inhibiting the microhomology-mediated end joining repair pathway induced the highest level of p21 activation on day 2, despite only a slight increase was observed on day 1 (Figure 5C, Figure S5). These results suggest that interference of difference DNA repair pathway would elicit various level of cytotoxicity.

Taken together, the deployment of our p21 reporter iPSC line as a tool for quantitatively measuring the toxicity of small molecules offers a unique lens through which the safety profiles of these agents can be evaluated, guiding the optimization of dosing strategies for future applications.

Discussion

Advancements in genome editing approach boosts development of gene therapies, but addressing safety concerns is paramount to their success. Our study, focusing on activating the TP53-P21 pathway in response to double-strand break (DSB)-induced genome editing or stresses mediated by vector delivery, highlights a critical cellular safeguard against genomic instability.36 The induction of this pathway, a hallmark of the cellular response to DNA damage and stress, underscores the need for meticulous monitoring and management in therapeutic applications. The development of a fluorescently tagged p21 reporter iPSC line has emerged as a pivotal tool in this context, enabling a nuanced dissection of cellular responses to genome editing-related agents.

Leveraging this novel reporter line, we confirmed rapid, DSB-specific p21 responses, underscoring its potential for real-time monitoring of genomic toxicity. We found that the p21 reporter cell line can be adopted to reveal indel frequency, making it a practical tool for screening more effective sgRNAs.

Delving deeper into our findings, we uncovered that longer dsODNs of ≥26 base pairs distinctly induce a robust p21 response, a stark contrast to the minimal activation by shorter sequences. This revelation is consistent with prior studies highlighting the length-dependent recognition of dsDNAs by cytosolic sensors, which in turn initiate a cascade leading to p21 activation. Our research refines the threshold for the cellular response against dsODNs to be between 22 and 26 base pairs, a critical insight that may guide developing strategies to minimize unwanted cellular stress responses.

Furthermore, our comparative analysis of self-complementary AAVs (scAAVs) and single-stranded AAVs (ssAAVs) revealed that scAAVs significantly amplify p21 expression. This enhanced response could be attributed to the more potent cellular sensing of the larger dsDNA regions present in scAAVs. Given the widespread use of AAV vectors in research and clinical settings, understanding the differential impacts of AAV configurations on cellular stress pathways is crucial. These insights not only inform the selection of vector types for gene therapy applications but also emphasize the need for careful consideration of vector-induced cellular responses to ensure therapeutic efficacy and safety.

In exploring the effects of LVs on p21 expression, our investigation highlighted the significant influence of promoter choice on cellular stress induction. The SFFV promoter demonstrated a marked increase in p21 activation compared to the CAG and EF1 promoters. This finding suggests that the viral origins of certain promoters may inherently provoke stronger cellular stress responses, potentially impacting the therapeutic utility of LV-based gene delivery systems. Our study underscores the importance of promoter selection in designing lentiviral vectors, advocating for a strategic approach that balances efficient gene expression with minimal activation of stress pathways to optimize gene therapy outcomes.

Our comparative analysis revealed that AAV vectors induce significantly higher levels of p21 expression than LVs, indicating a greater degree of cellular stress associated with AAV-mediated transduction. In contrast, IDLVs exhibited no observable p21-inducing effect, similar to LVs. These findings underscore the therapeutic potential of LVs and IDLVs, particularly in gene therapy applications targeting sensitive cell types such as hematopoietic stem cells and immune cells, where minimizing cellular stress is crucial. This insight into vector selection highlights the importance of choosing the optimal vector for specific therapeutic contexts, contributing to the development of safer and more effective gene therapy strategies.

Leveraging our p21 reporter iPSC line, we embarked on a pioneering study to quantitatively assess the toxicity of a range of small molecules that enhance CRISPR editing efficiency and precision. This investigation highlights the potential risks of inducing premature cellular senescence, a critical concern for stem cell-based therapies. Through meticulous evaluation, we identified that specific HDAC inhibitors, such as Entinostat, Panobinostat, and SAHA, significantly elevate p21 expression, indicating a notable impact on cellular stress mechanisms.

Additionally, our analysis extended to DNA repair mediators and cell cycle regulators, revealing nuanced effects on p21 expression. Notably, the DNA-PK inhibitor M3814 and the DNA ligase IV inhibitor Scr7 did not significantly induce p21, highlighting their potential for safer application in gene editing protocols. In contrast, agents like Olaparib, known for inhibiting specific DNA repair pathways, demonstrated a pronounced ability to trigger p21 activation, underscoring the importance of dose optimization to mitigate associated risks. This systematic approach to quantifying the toxicity of editing enhancers and modulators offers a robust framework for the safe advancement of gene editing technologies, ensuring the therapeutic potential of these interventions is realized with minimal adverse effects on cellular health.

The development of a fluorescently tagged P21 reporter cell line before our study provided valuable insights into P21 dynamics at the single-cell level in response to drug-induced DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs).10 This body of research highlighted that DSBs occurring during the S phase lead to delayed P21 expression, potentially indicating a better prognosis for cell proliferation. However, these studies predated the widespread adoption of CRISPR-Cas9 technology, leaving a gap in our understanding of how CRISPR-related activities influence P21 expression patterns. Our work not only bridges this knowledge gap but also extends the utility of the P21 reporter line to the realm of CRISPR-Cas9 editing, demonstrating its application in monitoring genomic integrity in real time.

Our comprehensive investigation into the activation of P21 in response to various components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system—from RNP and ODN transfection to AAV and LV transduction—reveals the nuanced interplay between genome editing technologies and cellular stress responses. Furthermore, by evaluating the impact of small molecules that enhance editing efficiency or precision, our study provides a foundation for using the P21 reporter line in high-throughput screening applications. This approach not only facilitates the optimization of gene editing strategies for improved safety and efficacy but also underscores the importance of considering drug-related cytotoxicity in the development of CRISPR-Cas9-based therapies.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Stem Cells online.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhu-Ying Gao (State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300020, China; Tianjin Institutes of Health Science, Tianjin 301600, China) for the development and verification of the IDLV packaging method that was adopted in this experiment.

Contributor Information

Yi-Dan Sun, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300020, People’s Republic of China; Tianjin Institutes of Health Science, Tianjin 301600, People’s Republic of China.

Guo-Hua Li, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300020, People’s Republic of China; Tianjin Institutes of Health Science, Tianjin 301600, People’s Republic of China.

Feng Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300020, People’s Republic of China; Tianjin Institutes of Health Science, Tianjin 301600, People’s Republic of China.

Tao Cheng, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300020, People’s Republic of China; Tianjin Institutes of Health Science, Tianjin 301600, People’s Republic of China.

Jian-Ping Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300020, People’s Republic of China; Tianjin Institutes of Health Science, Tianjin 301600, People’s Republic of China.

Xiao-Bing Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300020, People’s Republic of China; Tianjin Institutes of Health Science, Tianjin 301600, People’s Republic of China.

Author contributions

Xiao-Bing Zhang orchestrated and oversaw the study. Yi-Dan Sun led the experimental execution and data interpretation. Guo-Hua Li and Feng Zhang were responsible for vector cloning and packaging of AAV6 and lentiviral vectors. Jian-Ping Zhang managed PCR operations and materials procurement. Yi-Dan Sun drafted the manuscript, while Xiao-Bing Zhang provided critical revisions. Tao Cheng and Jian-Ping Zhang supplied essential administrative and financial backing. All authors engaged in the review process and endorsed the manuscript for submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests..

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2019YFA0110803, 2019YFA0110204, 2019YFA0110802, and 2021YFA1100900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81870149, 82070115, 81770198, 81890990, and 81730006), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (Grant Nos. 2024-I2M-3-018, 2023-I2M-2-007, 2022-I2M-2-001, 2022-I2M-2-003, 2021-I2M-1-041, 2021-I2M-1-040, and 2021-I2M-1-001), the Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 2020-PT310-011), the Tianjin Synthetic Biotechnology Innovation Capacity Improvement Project (Grant No. TSBICIP-KJGG-017), the CAMS Fundamental Research Funds for Central Research Institutes (Grant No. 3332021093), the Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem Innovation Fund (Grant Nos. 24HHXBSS00005 and HH22KYZX0022) and the China Nationally Funded Postdoctoral Researcher Program (Grant No.GZB20230081).

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816-821. 10.1126/science.1225829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ihry RJ, Worringer KA, Salick MR, et al. p53 inhibits CRISPR-Cas9 engineering in human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Med. 2018;24:939-946. 10.1038/s41591-018-0050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haapaniemi E, Botla S, Persson J, Schmierer B, Taipale J.. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing induces a p53-mediated DNA damage response. Nat Med. 2018;24:927-930. 10.1038/s41591-018-0049-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Georgakilas AG, Martin OA, Bonner WM.. p21: a two-faced genome guardian. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23:310-319. 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sturmlechner I, Zhang C, Sine CC, et al. p21 produces a bioactive secretome that places stressed cells under immunosurveillance. Science. 2021;374:eabb3420. 10.1126/science.abb3420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang JP, Li XL, Li GH, et al. Efficient precise knockin with a double cut HDR donor after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated double-stranded DNA cleavage. Genome Biol. 2017;18:35. 10.1186/s13059-017-1164-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Labun K, Montague TG, Krause M, et al. CHOPCHOP v3: expanding the CRISPR web toolbox beyond genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W171-W174. 10.1093/nar/gkz365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fu YW, Dai XY, Wang WT, et al. Dynamics and competition of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins and AAV donor-mediated NHEJ, MMEJ and HDR editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:969-985. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li XL, Li GH, Fu J, et al. Highly efficient genome editing via CRISPR-Cas9 in human pluripotent stem cells is achieved by transient BCL-XL overexpression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:10195-10215. 10.1093/nar/gky804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stewart-Ornstein J, Lahav G.. Dynamics of CDKN1A in single cells defined by an endogenous fluorescent tagging toolkit. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1800-1811. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dusre L, Covey JM, Collins C, Sinha BK.. DNA damage, cytotoxicity and free radical formation by mitomycin C in human cells. Chem Biol Interact. 1989;71:63-78. 10.1016/0009-2797(89)90090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ.. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339:786-791. 10.1126/science.1232458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luecke S, Holleufer A, Christensen MH, et al. cGAS is activated by DNA in a length-dependent manner. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1707-1715. 10.15252/embr.201744017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang D, Tai PWL, Gao G.. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat Rev Drug Disco. 2019;18:358-378. 10.1038/s41573-019-0012-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raj K, Ogston P, Beard P.. Virus-mediated killing of cells that lack p53 activity. Nature. 2001;412:914-917. 10.1038/35091082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Charlesworth CT, Hsu I, Wilkinson AC, Nakauchi H.. Immunological barriers to haematopoietic stem cell gene therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:719-733. 10.1038/s41577-022-00698-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mingozzi F, High KA.. Therapeutic in vivo gene transfer for genetic disease using AAV: progress and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:341-355. 10.1038/nrg2988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu L, Lahiri P, Skowronski J, et al. Molecular dynamics of genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 and rAAV6 virus in human HSPCs to treat sickle cell disease. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2023;30:317-331. 10.1016/j.omtm.2023.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martino AT, Suzuki M, Markusic DM, et al. The genome of self-complementary adeno-associated viral vectors increases Toll-like receptor 9-dependent innate immune responses in the liver. Blood. 2011;117:6459-6468. 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu T, Töpfer K, Lin SW, et al. Self-complementary AAVs induce more potent transgene product-specific immune responses compared to a single-stranded genome. Mol Ther. 2012;20:572-579. 10.1038/mt.2011.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferrari S, Jacob A, Cesana D, et al. Choice of template delivery mitigates the genotoxic risk and adverse impact of editing in human hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29:1428-1444.e9. 10.1016/j.stem.2022.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Escors D, Breckpot K.. Lentiviral vectors in gene therapy: their current status and future potential. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2010;58:107-119. 10.1007/s00005-010-0063-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Annoni A, Gregori S, Naldini L, Cantore A.. Modulation of immune responses in lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer. Cell Immunol. 2019;342:103802. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Piras F, Riba M, Petrillo C, et al. Lentiviral vectors escape innate sensing but trigger p53 in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:1198-1211. 10.15252/emmm.201707922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yam PY, Li S, Wu J, et al. Design of HIV vectors for efficient gene delivery into human hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther. 2002;5:479-484. 10.1006/mthe.2002.0558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J.. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193-199. 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang X, Xu Z, Tian Z, et al. The EF-1α promoter maintains high-level transgene expression from episomal vectors in transfected CHO-K1 cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:3044-3054. 10.1111/jcmm.13216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Banasik MB, McCray PB Jr. Integrase-defective lentiviral vectors: progress and applications. Gene Ther. 2010;17:150-157. 10.1038/gt.2009.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petrova NV, Velichko AK, Razin SV, Kantidze OL.. Small molecule compounds that induce cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2016;15:999-1017. 10.1111/acel.12518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang JP, Yang ZX, Zhang F, et al. HDAC inhibitors improve CRISPR-mediated HDR editing efficiency in iPSCs. Sci China Life Sci. 2021;64:1449-1462. 10.1007/s11427-020-1855-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin S, Staahl BT, Alla RK, Doudna JA.. Enhanced homology-directed human genome engineering by controlled timing of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. eLife. 2014;3:e04766. 10.7554/eLife.04766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang D, Scavuzzo MA, Chmielowiec J, et al. Enrichment of G2/M cell cycle phase in human pluripotent stem cells enhances HDR-mediated gene repair with customizable endonucleases. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21264. 10.1038/srep21264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maurissen TL, Woltjen K.. Synergistic gene editing in human iPS cells via cell cycle and DNA repair modulation. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2876. 10.1038/s41467-020-16643-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li G, Zhang X, Zhong C, et al. Small molecules enhance CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-directed genome editing in primary cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8943. 10.1038/s41598-017-09306-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Riesenberg S, Maricic T.. Targeting repair pathways with small molecules increases precise genome editing in pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2164. 10.1038/s41467-018-04609-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vaddavalli PL, Schumacher B.. The p53 network: cellular and systemic DNA damage responses in cancer and aging. Trends Genet. 2022;38:598-612. 10.1016/j.tig.2022.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.