Abstract

Background

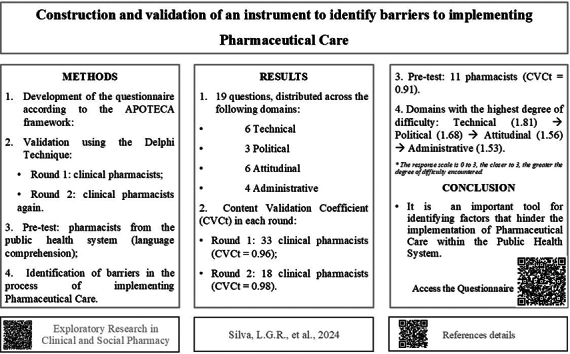

Pharmaceutical Care is a professional practice in high demand for implementation in Primary Health Care within the Public Health System. Consequently, it was necessary to develop and validate an instrument to assess the obstacles to this process.

Methods

A methodological study was conducted in three stages: first, the questionnaire was developed based on the APOTECA framework, which includes Attitudinal, Political, Technical, and Administrative domains. Second, the content was validated using the Delphi Technique, with a content validity coefficient greater than or equal to 0.8 considered acceptable. Third, a pre-test was conducted with pharmacists working in Primary Health Care within the Public Health System. After validation, the instrument was administered to pharmacists participating in a training and support project for the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care.

Results

The results indicated that the instrument was validated after two rounds of evaluation, with the first round involving 33 experts achieving a total content validity coefficient of 96 %, and the second round involving 18 experts achieving a total content validity coefficient of 98 %. In the third stage, the pre-test with Primary Health Care pharmacists resulted in a total content validity coefficient of 91 %. The final version of the questionnaire, which incorporated suggestions for improvements, included 19 questions. When answered by pharmacists, the responses indicated that Technical questions were the most significant barrier to implementation, followed by Political, Attitudinal, and Administrative questions.

Conclusion

The validation of this instrument provides an important tool for identifying factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care within the Public Health System.

Keywords: Validation study, Evidence-based pharmaceutical practice, Pharmaceutical care, Public health system

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Tool identifies barriers to implementing pharmaceutical care in Primary Health Care.

-

•

The validation was conducted using the Delphi Technique.

-

•

The tool has 19 questions in 4 domains: Attitudinal, Political, Technical, Administrative.

-

•

The barriers with the greatest impact belonged to the Technical domain.

1. Introduction

Pharmaceutical Care (PC) encompasses a series of services aimed at the population, such as health tracking and education, management of self-limited problems, medication dispensing, review of pharmacotherapy, and pharmacotherapeutic monitoring, thus bringing numerous economic and humanistic benefits.1., 2., 3. Thus, there is a growing demand for this service to be included in everyday life at different levels of health care, with the pharmacist working in an integrated manner with health teams, due to PC contributing to reducing complications and damage caused by medications to patients.4., 5., 6.

Despite the benefits, PC is not uniformly incorporated into health systems, facing several barriers in its implementation and consolidation, such as: lack of knowledge among the population, scarcity of human and financial resources, lack of knowledge on the part of the community and patients, little understanding of the roles and responsibilities of the clinical pharmacist within the multidisciplinary healthcare team, and lack of time for pharmacists to perform patient care services. These difficulties are present both in countries with emerging economies7., 8., 9. and in developed countries.10., 11., 12., 13.

Knowing the barriers inherent to each place where PC is planned to be implemented is a necessary step to overcome them and achieve the consolidation of clinical services. Onozato and collaborators (2019) developed APOTECA (from the acronym: Attitudinal, Political, Technical, and Administrative), in order to list the factors that hinder the implementation of PC in the hospital environment.14 With regard to Primary Health Care (PHC), there is, to our knowledge, no instrument for identifying these barriers.

In view of the above, this study is justified by the absence of validated instruments that allow identifying the barriers for PC to be implemented in PHC in the Brazilian health system. Thus, the development and validation of the instrument contribute to filling the gaps between the knowledge available from scientific evidence and its use aimed at the population. Therefore, the study aims to develop and validate an instrument to identify the factors that hinder the implementation of PC in PHC.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design

This is a methodological study, with construction and validation of the instrument entitled ‘Factors hindering the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care within the scope of the Public Health System (SUS)’. Validation was developed using the Delphi technique,15 starting from the domains present in the APOTECA framework: Attitudinal, Political, Technical, and Administrative 14, and divided into three stages: elaboration of the questionnaire based on the literature; content validation; and a pre-test with pharmacists who work in SUS PHC.16 After validation, the questionnaire was answered by pharmacists (also working in SUS PHC) who participated or are participating in a training and support project for the implementation of PC.

2.2. Step 1: Elaboration of the questionnaire

To prepare the questionnaire, the APOTECA framework was used, which served as a base model for preparing the instrument. APOTECA is supported by four pillars, defined by Onozato (2019)14 as follows:

-

a)

Attitudinal: relates to behavior (action/reaction) motivated by feeling/opinion related to a fact or person;

-

b)

Political: relates to relationships within a group/organization that allow individuals to influence others, referring to assistance and support;

-

c)

Technical: relates to the characteristics of the implemented pharmaceutical clinical service, together with the skills and knowledge required for its execution;

-

d)

Administrative: relates to administrative processes, both organizational and managerial, necessary for the execution of pharmaceutical clinical services.

Understanding these factors and their relationships allows the implementation of pharmaceutical clinical services to be carried out in a sustainable and appropriate manner, resulting in an increase in the quality of services to meet the demands of patients and healthcare professionals.14

In the first stage, the questionnaire ‘Factors hindering the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care within the scope of the Public Health System (SUS)’ was prepared, based on the domains of the APOTECA framework: Attitudinal, Political, Technical, and Administrative.14 It is an individual, self-administered questionnaire and in each domain, questions were presented that were required to be evaluated.

2.3. Step 2: Content validation

The Delphi technique was used for validation. The judges to carry out the validation were selected for convenience, so that the composition of the panel was balanced between impartiality and interest in the subject, and that it was varied in relation to time of experience, areas of specialty, and perception regarding the problem analyzed. This characteristic of the panel of judges, of heterogeneous groups, allows a positive contribution for achieving the purpose of motivating the application of the method.15,17

The judging pharmacists were identified through an active search, and they were contacted via their email addresses and/or telephone numbers. After agreeing to participate, the experts signed the Free and Informed Consent Form (Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido - TCLE) and analyzed each question, scoring them, as shown in Chart 1. Upon returning the answers, a second round was carried out with these same experts.

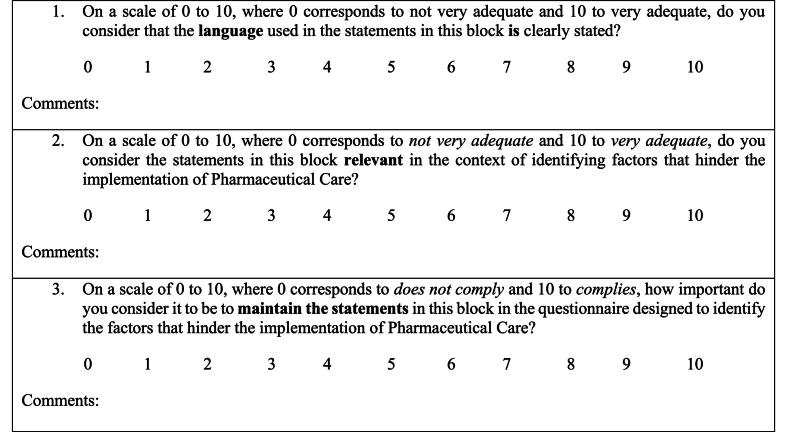

Chart 1.

Questions intended for pharmacist judges, to evaluate the instrument regarding the language, relevance, and maintenance of questions in each block, 2023.

Source: prepared by the authors.

In order to evaluate the questionnaire, a form was created for the judges on Google Forms®, which presented three questions for each domain (block), totaling 12 questions, explained in Chart 1. These questions were evaluated using a Likert type scale, from 0 to 10, with the evaluations being the language style used, the relevance in the context of identifying the factors that hinder the implementation of PC, and finally the assessment of the need to maintain the questions.17

Resources from the virtual environment were used to carry out the data collection, control, statistical analysis, and communication between the researcher and the judges. Thus, initially the judges analyzed the instrument with the aim of evaluating the relevance of the questions contained based on the scores given, and if the score was lower than eight, a suggestion/improvement comment was requested. Comments and suggestions were also analyzed, even in the case of scores equal to or greater than eight.15, 16., 17.

The validation of the instrument was carried out in two rounds by the judges. Initially, the instrument to be validated was sent, along with the form created in Google Forms®, containing the items to be evaluated. At this stage, the judges had 30 days to respond to the form. According to the answers provided, questions were changed in the instrument and a second round was carried out with the same judges, who had 20 days to return.

The Content Validation Coefficient (CVC) was calculated using the following steps:

(a) calculation of the average score (Mx);

(b) calculation of the initial CVC (CVCi), by dividing the average by the maximum point value that the item could achieve;

(c) calculation of the error (Pei), based on the division of the number one (1) by the total number of evaluating judges, increased by the same number of evaluators – the error aims to minimize possible biases of these judges;

(d) calculation of the final CVC (CVCc), from the subtraction of the CVCi from the Pei.18,19

Items with CVCc greater than 0.8 were considered valid.16 Statistical analysis was performed according to the CVC formulas implemented in the Excel program, version 10 from Microsoft®.

2.4. Step 3: Pre-test

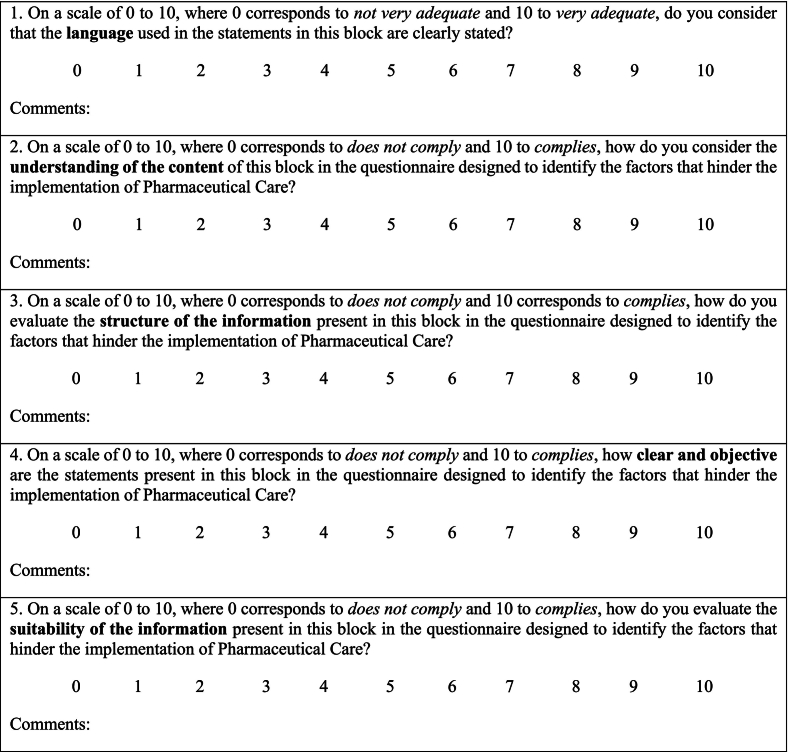

After validation of the instrument by the judges, carried out in two rounds, a pre-test was carried out with pharmacists working in SUS PHC, with the aim of verifying whether it would be properly understood. At this stage, each domain (block) of the questionnaire intended for the target population was analyzed, as shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2.

Questions aimed at pharmacists working in Primary Care of the Brazilian Public Health System, 2023.

Source: prepared by the authors.

An electronic form, created on the Google Forms® platform, was used to collect responses from the applied pre-test. At this stage, agreement between the responses of PHC pharmacists who were the target audience for the pre-test was also verified, using the CVC.

2.5. Application of the validated instrument for pharmacists

This stage aimed to understand the factors that hinder the implementation of PC in municipalities in the state of Minas Gerais (Brazil). The respondents were pharmacists who participated in a training and support project for the implementation of PC. The questionnaire was inserted into the Google Forms® platform and the link was sent via email and an instant messaging application (WhatsApp Messenger®). A period of 15 days was given to respond, counting from the date of receipt of the invitation.

For the purposes of interpreting the instrument, each of the response options was assigned a value:

-

•

Doesn't make it difficult at all: 0 points

-

•

Makes it a little difficult: 1 point

-

•

More or less difficult: 2 points;

-

•

Very difficult: 3 points.

Subsequently, the average of each of the 19 questions was calculated, ranging from 0 to 3: the closer to 3, the more difficult the factor reported in the question. The average for each block (Administrative, Political, Technical, and Attitudinal) was also calculated. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee Involving Human Subjects (CEPES) of the Federal University of São João del-Rei (UFSJ), Campus Centro-Oeste Dona Lindu (CAAE 45666921.0.0000.5545), and by the Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials (ReBEC), identifier RBR-85 kg336.

3. Results

The final instrument presented 19 statements, including: four from the Administrative domain, six from the Technical domain, six from the Attitudinal domain, and three from the Political domain. The questionnaire is available in English and Portuguese versions on the website https://ufsj.edu.br/nepefac/instrumentos_guias_e_pareceres.php

3.1. Preparation and validation of the questionnaire

Of the 96 pharmacists invited to participate as judges, 33 agreed to participate in the first round and 18 in the second. None of the points analyzed obtained a CVCc <0.8, according to the CVCc presented in Table 1; the total CVC (CVCt) in the first round was 0.96 (96 %), and in the second round the CVCt was 0.98 (98 %), after the two rounds.

Table 1.

Final content validity coefficient (CVCc) of experts' assessments in the two rounds on the questionnaire “Instrument for evaluating potential hindering factors for the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care within the scope of the Public Health System (SUS)”, 2023.

| FIRST ROUND | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Points covered | CVCc content validation (n = 33) |

|||

| CVC Administrative Factors | CVC Technical Factors | CVC Attitudinal Factors | CVC Political Factors | |

| Do you consider that the language used in the statements in this block are clearly stated? | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.9 4 |

| Do you consider the statements in this block relevant in the context of identifying the factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care? | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| How important do you consider it to be to maintain the statements in this block in the questionnaire designed to identify the factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care? | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

| CVCt of each block | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| CVCt of the entire instrument | 0.96 (96 %) | |||

| SECOND ROUND |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Points covered | CVCc content validation (n = 18) |

|||

| CVC Administrative Factors | CVC Technical Factors | CVC Attitudinal Factors | CVC Political Factors | |

| Do you consider that the language used in the statements in this block are clearly stated? | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.93 |

| Do you consider the statements in this block relevant in the context of identifying the factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care? | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| How important do you consider it to be to maintain the statements in this block in the questionnaire designed to identify the factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care? | 1 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| CVCt of each block | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| CVCt of the entire instrument | 0.98 (98 %) | |||

Source: prepared by the authors.

Regarding the profile of the judges, in the first round, the age is between 24 and 55 years old, with an average of 32.75 years old (standard deviation ±6.7). As for the institution where they graduated, 65.7 % were from public universities and 34.3 % from private universities, with training completed between the years 1996 and 2022. In relation to the judges' degree, 42.9 % have a master's degree, 22.9 % lato sensu specialization, and 5.7 % a doctorate.

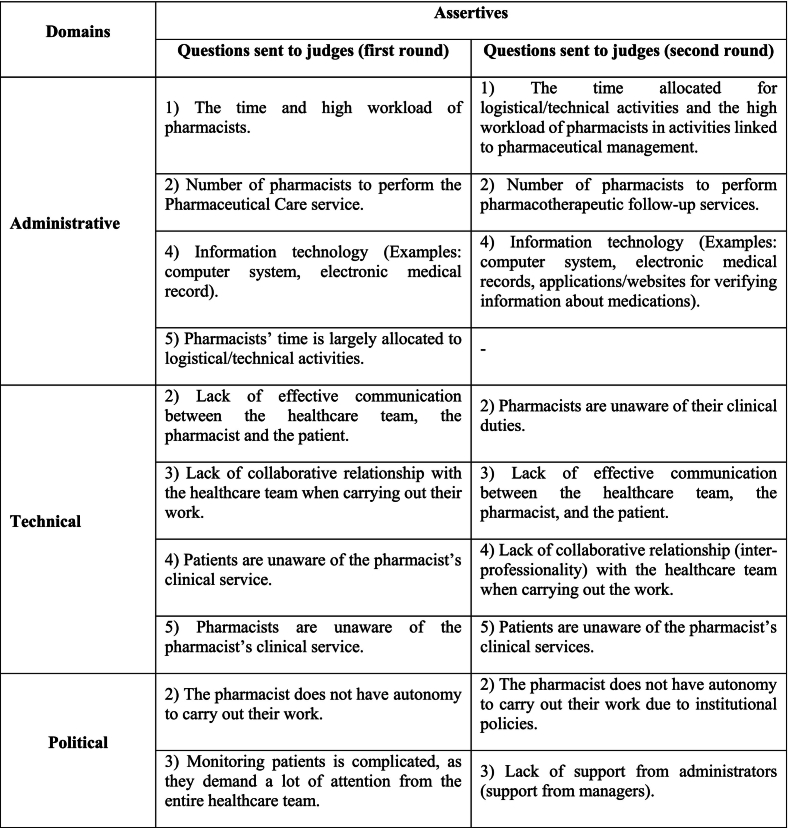

Even with all CVCc higher than 0.80 in the first round, some changes were made to the questionnaire after the judges suggested that the second round be carried out. Of the questions contained in the questionnaire, only question number 5 from the Administrative domain was removed. It was reformulated to appear together with question 1, in the same domain. In the Technical domain, in addition to the reformulation of the questions, there was also a change in their numbering. Finally, in the Political domain, two questions were reformulated in order to improve understanding when applying the questionnaire, as shown in Chart 3 (at this moment, there have been no changes in the attitudinal domain):

Chart 3.

Changes made to the questionnaire “Instrument for evaluating potential hindering factors for the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care within the scope of the Public Health System (SUS)”, after the first round, 2023 (n = 33).

Source: prepared by the authors.

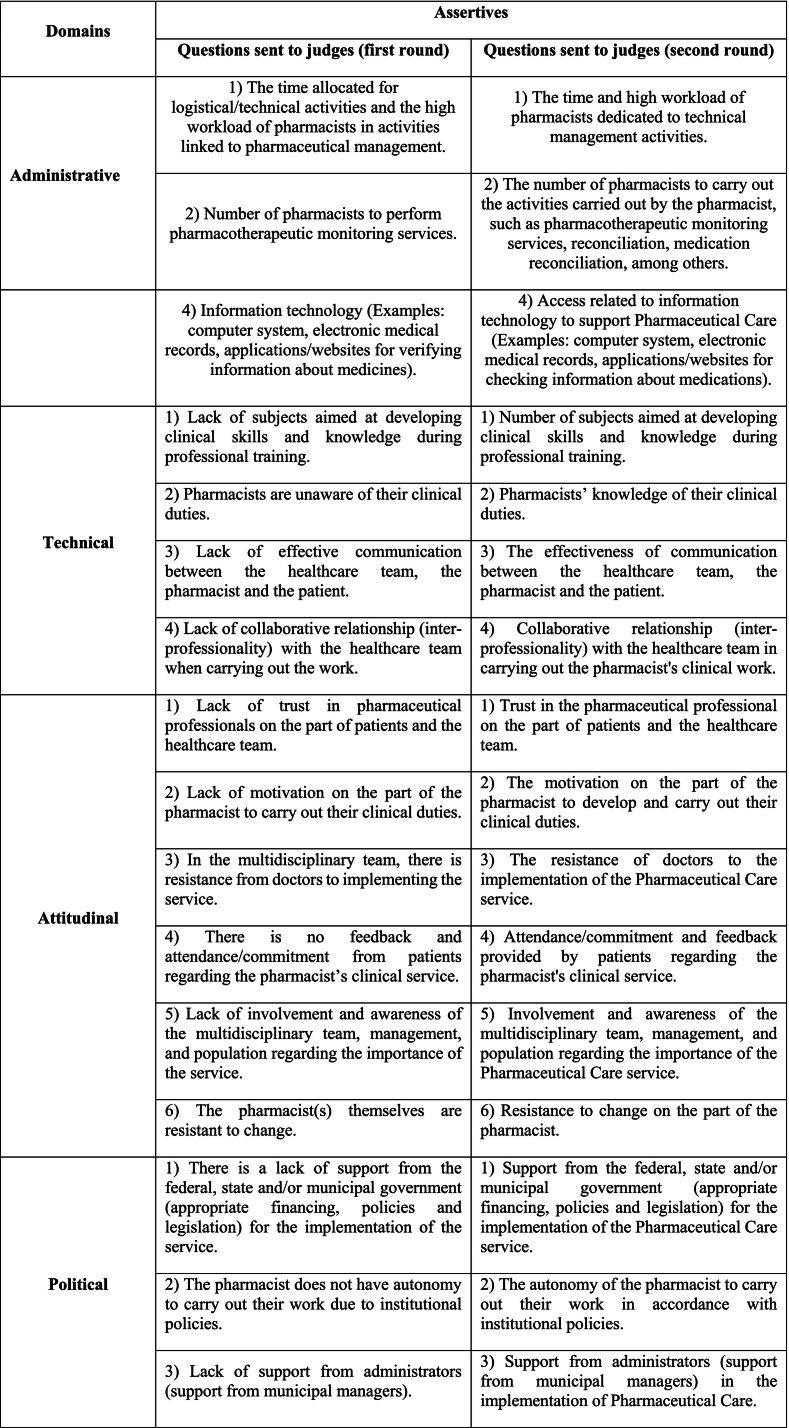

None of the points analyzed in the first round obtained CVCc <0.8, whereas the CVCt in the first round was 0.96 (96 %). However, the suggestions for improvement were accepted and changes were made. Therefore, the instrument to be validated was sent back to the judges for a new evaluation, to continue the second round of validation, with the participation of 18 experts, in which none of the points obtained CVCc <0.8, resulting in a CVCt of 0.98 (98 %). There were 11 new suggestions, which were considered after the second round, and again the instrument underwent some changes, presented in Chart 4, so that it could be sent to the group of pharmacists who make up the target audience for the pre-test (pharmacists from PHC of the SUS). The questionnaire initially consisted of 20 questions, all multiple choice and with space for possible comments. In the end, one question was removed, totaling 19.

Chart 4.

Changes made to the questionnaire “Tool for evaluating potential hindering factors for implementing Pharmaceutical Care within the scope of the Public Health System (SUS)”, after the second round, 2023 (n = 18).

Source: prepared by the authors.

It is worth mentioning that there were comments from the judges about spelling, the logical sequence for question arrangement on the instrument, or suggestions about writing, in order to improve understanding. In the first round, among the comments left by the panelists, some were more prominent regarding the change in the statement, such as: “The time and high workload of pharmacists”, in which the judge commented that it was necessary to “Specify the pharmaceutical workload: the time and high workload of the pharmacist in activities linked to the management of pharmaceutical care”; the suggestion being accepted, so that for the second round the assertion was presented in the instrument as follows: “The time allocated for logistical/technical activities and the high workload of pharmacists in activities linked to pharmaceutical management”, as shown in Chart 3.

Likewise, in the second round, some considerations highlighted by the judges were analyzed and the instrument underwent changes, mostly with regard to the writing of the statements, which could induce the pharmacist, “In some questions, the statement to be analyzed presents a negative when presenting the complicating factor. When reading the text, I have the impression that the pharmacist is led to agree with that difficulty. Therefore, I suggest that the language be placed in a more neutral way, so that in the answer options the pharmacist can make their assessment in a more impartial way”, as for example in the statement “Absence of subjects aimed at developing clinical skills and knowledge during the professional qualification”. After the change in the instrument, it was presented as follows: “Number of subjects aimed at developing clinical skills and knowledge during professional training” as shown in Chart 3.

In the first round there were 34 comments, which resulted in the rewriting of six of the 20 statements and the exclusion of one (as shown in Table 1); and in the second round, 11 comments, which resulted in the rewriting of 15 of the 19 statements. This fact shows that the quantitative content analysis must occur together with a qualitative analysis, because although the CVC values are higher than 0.80, the comments explained the need to change and delete the messages.

3.2. Pre-test

In the pre-test, regarding the profile of the participating pharmacists, their ages ranged from 23 to 51 years old, with an average of 32.7 years old (standard deviation ±7.9). Regarding the type of university at which they completed their degree, 72.7 % responded with public universities and 27.3 % to private universities. As for postgraduate studies, 45.5 % have a lato sensu specialization, 18.2 % a doctorate, and 9.1 % a master's degree, while 27.3 % do not have a postgraduate degree.

In validation with the target audience, which occurred with the pre-test, 93 SUS PHC pharmacists (who did not participate in the training and support project for the implementation of PC) were invited to participate, and 11 accepted. As with the validation of the questionnaire by experts, none of the points analyzed had a CVCc lower than 0.8 and the CVCt was 91 % (Table 2).

Table 2.

Final content validity coefficient (CVCc) of the pre-test group evaluation of the questionnaire “Instrument for evaluating potential hindering factors for the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care within the scope of the Public Health System (SUS)”, 2023 (n = 11).

| Points covered | CVCc content validation (n = 11) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVC Administrative Tactors | CVC Technical Factors | CVC Attitudinal Factors | CVC Political Factors | |

| Do you consider that the language used in the statements in this block are clearly stated? | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

| How do you consider the understanding of the content of this block in the questionnaire designed to identify the factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care? | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.86 |

| How do you evaluate the structure of the information present in this block in the questionnaire designed to identify the factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care? | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| How clear and objective are the statements present in this block in the questionnaire designed to identify the factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care? | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| How do you evaluate the suitability of the information present in this block in the questionnaire designed to identify the factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care? | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| CVCt of each block | 0.9 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| CVCt of the entire instrument | 0.91 (91 %) | |||

Source: prepared by the authors.

After evaluating the pre-test stage, none of the questions were modified.

3.3. Identification of factors hindering the implementation of pharmaceutical care

Of the 21 pharmacists (from 15 Brazilian municipalities) who participated in a training and support project for the implementation of PC, 19 (14 municipalities) responded to the validated instrument. The average age was 39.16 (±5.66) years, 89.48 % (17) were female, and all pharmacists graduated, on average, 15.21 (±6.29) years ago. Regarding the type of university, 68.42 % (13) declared their graduation from public institutions and 84.21 % (16) have completed some type of postgraduate degree.

Regarding the phase of the project (training and support for the implementation of PC) in which they were, 63.15 % (10) of the pharmacists had already regulated PC in the municipality where they operate. Normalizing PC is understood as the approval of the normative act (decree, ordinance. or resolution) that regulates PC in the municipality. The pharmacists participating in this phase had already carried out an average of 5.32 ± 2.94 consultations.

The “Technical” block was the main barrier reported by the study pharmacists (average = 1.85), followed by the “Political” block (average = 1.68) and “Attitudinal” (average = 1.56). The “Administrative” block presented the lowest average (1.53), thus presenting the lowest degree of difficulties (Table 3). The response scale is 0 to 3, the closer to 3, the greater the degree of difficulty encountered.

Table 3.

Domains of the Instrument for identifying factors that hinder the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care and their respective scores, following responses from Brazilian pharmacists (n = 19).

| Domain | Factors | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative | High workload focused on technical medication management | 1.95 |

| Number of pharmacists to carry out technical and clinical management | 1.84 | |

| Information contained in medical records | 1.21 | |

| Access to information technology | 1.11 | |

| Mean | 1.53 | |

| Lack of subjects focused on the clinic in undergraduate courses | 1.74 | |

| Technical | Pharmacists' knowledge of clinical assignments | 1.37 |

| Communication: multidisciplinary team, pharmacist, and patient | 1.58 | |

| Relationship with multidisciplinary team | 1.84 | |

| Patients' lack of knowledge about Pharmaceutical Care | 2.26 | |

| Lack of knowledge of the health team and management about Pharmaceutical Care | 2.32 | |

| Mean | 1.85 | |

| Attitudinal | Trust in the pharmacist by the multidisciplinary team and patients | 1.47 |

| Motivation of pharmacists to develop their clinical duties | 1.63 | |

| Medical resistance for the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care | 1.32 | |

| Patient commitment to pharmaceutical care | 1.74 | |

| Involvement of the multidisciplinary team, management and population regarding the importance of Pharmaceutical Care | 2.00 | |

| Resistance to change on the part of the pharmacist themself | 1.21 | |

| Mean | 1.56 | |

| Political | Government support (federal, state/municipal) for the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care | 1.94 |

| Pharmacist autonomy to perform their clinical duties within institutions | 1.47 | |

| Support from local managers (of health units) in the implementation of Pharmaceutical Care | 1.63 | |

| Mean | 1.68 |

Source: prepared by the authors.

The questions with the highest scores were in the “Technical” domain, especially those that addressed the lack of knowledge of positive PC experiences on the part of the multidisciplinary team, management, and patients. This issue is linked to the main barrier of the “Attitudinal” domain, which concerns the involvement of the multidisciplinary team, management awareness, and guidance of the population regarding the importance of PC.

In the “Administrative” block, the lack of time due to the high workload of pharmacists (who are overloaded with the technical management of medications) was the most common barrier; and in the “Political” block, the lack of support from federal, state and municipal governments (appropriate financing, policies and legislation) for implementation of PC was the main obstacle identified.

Other relevant points were the lack of access related to information technology to support PC (mainly the use of electronic medical records); the lag in the academic training of pharmacists; and medical resistance to the implementation of PC.

4. Discussion

The clarity of the information achieved by the judging pharmacists and the target audience, as well as the relevance and importance of each question, evaluated by the CVC (>0.8), showed that the questionnaire is suitable for the population for which it is intended (pharmacists who work in PHC in the SUS).17., 18., 19., 20. The CVC calculation is used to validate several instruments in the health sector.21., 22., 23. Furthermore, the questionnaire proved to be viable to be applied to the target population, whose responses were satisfactorily compiled. In practical terms, a CVCc greater than 0.8 indicates that the instrument effectively assesses what it intends to measure, demonstrating good validity, robustness, and reliability, while also reducing the risk of bias.18

The questions with the highest scores were from the “Technical” domain. Systematic reviews also highlighted issues in the technical domain, such as lack of knowledge about PC (both on the part of other health professionals and patients) as important barriers to the implementation of PC.24., 25., 26. To overcome such obstacles, it is important that there is knowledge sharing between health team professionals and collaborative work between them, in addition to good communication.6,27 Furthermore, building a bond with the patient contributes positively to the implementation of PC and to the recognition and appreciation of all professionals involved in person-centered comprehensive care [26,28].

The lack of time for clinical activities due to the high workload allocated to technical management (Administrative domain), are barriers that were also found by Hatton and collaborators in their systematic review (2021),26 and Kilonzi et al. (2023) in implementing PC in hospitals in Tanzania.6 To mitigate this problem, it is important that the pharmacist delegates those functions that are not restricted to them. The exchange of knowledge between assistants and pharmacists and team training increase the possibility of delegating some activities, such as the delivery of medications, local organization, and the ability to resolve problems with access to medications; thus improving workflow. In this way, pharmacists have more time for clinical activities.7,24

The lack of political support (in all spheres of government and from the managers of the institutions themselves) makes the implementation and sustainability of PC difficult.14 In Brazil, important public policies have placed PC as a guideline,29,30 but more efforts are important to institutionalize these clinical activities, ensuring adequate structure, access to information technologies, qualification of professionals, financing, and evaluation of results, to ensure the sustainability of PC [31,32].

It is important to highlight that overcoming the barriers to implement PC strengthens not only pharmaceutical services, but also Brazilian PHC, which proposes integrated work between health team professionals, guaranteeing the population not only the recovery and protection of health, but the prevention of diseases, through a joint construction of interventions and therapeutic projects, at an individual and collective level.33,34

Despite the unprecedented instrument being suitable for the target audience and capable of identifying the factors that hinder the implementation of PC within the SUS, it is important to highlight the following limitations of the validation process: difficulty in finding professionals who present knowledge on the topic and are available to participate; lack of availability of judges to participate and comply with data collection, affecting the response rate; possibility of not receiving the invitation due to blocking of the email protection system; and a potential bias regarding understanding on the part of respondents, both in validation by Delphi and in the pre-test.15

Additionally, it is important to highlight that the decrease in the number of pharmacists participating in each round of validation can be partly attributed to a lack of time resulting from work overload. Furthermore, “survey fatigue” is a significant factor, as the increase in online surveys has further burdened professionals, resulting in reduced participation. This phenomenon is frequently observed in health studies, where an excess of questionnaires can lead to decreased respondent engagement.35

5. Conclusions

The instrument for evaluating the factors hindering the implementation of PC within the scope of the SUS, developed and validated by experts, can be applied within the scope of PHC. Validation was carried out using the Delphi technique and proved to be relevant, since at the end of the second round, after the evaluation by the pharmacists who made up the panel of judges, all items obtained a CVCc greater than 0.8, a value recommended as the cutoff point to consider each item evaluated as valid.

The pharmacists who responded to the validated instrument identified that the main factors hindering the implementation of PC were: the population's lack of knowledge about PC (Technical); the lack of political support for this implementation to occur and be sustained (Political); the low involvement between pharmacists and other members of the multidisciplinary team and management regarding the importance of offering PC (Attitudinal); and the high workload focused on technical issues (Administrative).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Luanna Gabriella Resende da Silva: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Rúbia Yumi Murakami Silva: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mariana Linhares Pereira: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Maria Teresa Herdeiro: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. André Oliveira Baldoni: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank the Federal University of São João del-Rei (UFSJ), campus Centro-Oeste Dona Lindu and Clinical Pharmacy Teaching and Research Center (NEPeFaC).

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Support Foundation of the state of Minas Gerais (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do estado de Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG - APQ-01107-21), by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES – 001), and by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq - 304131/2022–9).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsop.2024.100529.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material.

References

- 1.McKenzie C., Spriet I., Hunfeld N. Ten reasons for the presence of pharmacy professionals in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50:147–149. doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phimarn W., Saramunee K., Leelathanalerk A., et al. Economic evaluation of pharmacy services: a systematic review of the literature (2016–2020) Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;45:1326–1348. doi: 10.1007/s11096-023-01590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sallom H., Abdi A., Halboup A.M., Başgut B. Evaluation of pharmaceutical care services in the Middle East countries: a review of studies of 2013–2020. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:1364. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forgerini M., Lucchetta R.C., Oliveira F.M., Herdeiro M.T., Capela M.V., Mastroianni P.C. Impact of pharmacist intervention in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2022;58 doi: 10.1590/s2175-97902022e19876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merks P., Religioni U., Jaguszewski M., et al. Patient satisfaction survey of “healthy heart” pharmaceutical care service – evaluation of pharmacy labelling with pharmaceutical pictograms. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:962. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09986-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilonzi M., Mutagonda R.F., Mlyuka H.J., et al. Barriers and facilitators of integration of pharmacists in the provision of clinical pharmacy services in Tanzania. BMC Prim Care. 2023;24:72. doi: 10.1186/s12875-023-02026-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerqueira-Santos S., Rocha K.S.S., Araújo D.C.S.A., et al. Which factors may influence the implementation of drug dispensing in community pharmacies? A qualitative study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2023;29:83–93. doi: 10.1111/jep.13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barberato L.C., Scherer M.G.A., Lacourt R.M.C. The pharmacist in the Brazilian primary health care: insertion under construction. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2019;24:3717–3726. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320182410.30772017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eldin M.K., Mohyeldin M., Zaytoun G.A., et al. Factors hindering the implementation of clinical pharmacy practice in Egyptian hospitals. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2022;20:2607. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2022.1.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jebara T., Cunningham S., MacLure K., et al. Health-related stakeholders' perceptions of clinical pharmacy services in Qatar. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;43:107–117. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorgenson D., Laubscher T., Lyons B., Palmer R. Integrating pharmacists into primary care teams: barriers and facilitators. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22:292–299. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sin C.M.H., Huynh C., Dahmash D., Maidment I.D. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical pharmacy services on paediatric patient care in hospital settings. EJHP. 2022;29:180–186. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2020-002520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weidmann A.E., Hoppel M., Deibl S. It is the future. Clinical pharmaceutical care simply has to be a matter of course. - Community pharmacy clinical service providers' and service developers' views on complex implementation factors. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022;18:4112–4123. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2022.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onozato T., C. Francisca dos Santos Cruz, A.G. Milhome da Costa Farre, C.C. Silvestre, R.O.S. Silva, G.A. Santos-Junior, et al. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical pharmacy services for hospitalized patients: a mixed-methods systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;16:437–449. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocha-Filho C.R., Cardoso T.C., Dewulf N., de L.S . 1st ed. Brazil Publishing; Curitiba, PR: 2019. Método e-Delphi modificado: um guia para validação de instrumentos avaliativos na área da saúde. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reis T.M., Zanetti A.C.B., Obreli-Neto P.R., et al. Pharmacists in dispensing drugs (PharmDisp): construction and validation of a questionnaire to assess the knowledge for dispensing drug before and after a training course. Rev Eletr Farm. 2018;14 doi: 10.5216/REF.V14I4.45372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez-Nieto R. 1st ed. Booksurge Publishing; Mérida, Universidad de Los Andes: 2002. Contributions to Statistical Analysis: The Coefficients of Proportional Variance, Content Validity and Kappa. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasquali L. 1st ed. Vozes; Petrópolis, RJ: 2017. Psicometria: teoria dos testes na psicologia e na educação. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigues L.S., Tinoco M.S., da Silva L.G.R., et al. Barriers and enablers to deprescribing benzodiazepines in older adults: elaborating an instrument and validating its content. GGA. 2021;15:1–9. doi: 10.53886/gga.e0210059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coluci M.Z.O., Alexandre N.M.C., Milani D. Construção de instrumentos de medida na área da saúde. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20:925–936. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015203.04332013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishaq I., Skinner I.W., Mehta P., Walton D.M., Bier J., Verhagen A.P. Clinical validation of grouping conservative treatments in neck pain for use in a network meta-analysis: a Delphi consensus study. Eur Spine. 2024;33:166–175. doi: 10.1007/s00586-023-08025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravid-Saffir A., Sella S., Ben-Eli H. Development and validation of a questionnaire for assessing parents' health literacy regarding vision screening for children: a Delphi study. Sci Rep. 2023;13:13887. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-41006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohanty S., Mohanty A., Cool J.A., Fainstad B. Validation of an educational tool for skin abscess incision and drainage by Delphi and Angoff methods. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38:3093–3098. doi: 10.1007/s11606-023-08205-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lelie-van der Zande R., Koster E.S., Teichert M., Bouvy M.L. Barriers and facilitators for providing self-care advice in community pharmacies: a qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;45:758–768. doi: 10.1007/s11096-023-01571-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riboulet M., Clairet A.L., Bennani M., Nerich V. Patient preferences for pharmacy services: a systematic review of studies based on discrete choice experiments. Patient. 2024;17:13–24. doi: 10.1007/s40271-023-00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatton K., Bhattacharya D., Scott S., Wright D. Barriers and facilitators to pharmacists integrating into the ward-based multidisciplinary team: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17:1923–1936. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva B.B., Fegadolli C. Implementation of pharmaceutical care for older adults in the Brazilian public health system: a case study and realistic evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4898-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuhec M., Hahn M., Taskova I., et al. Clinical pharmacy services in mental health in Europe: a commentary paper of the European Society of Clinical Pharmacy Special Interest Group on mental health. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;45:1286–1292. doi: 10.1007/s11096-023-01643-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos. Serviços farmacêuticos na atenção básica à saúde / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos. – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2014. 108 p. : il. – (Cuidado farmacêutico na atenção básica; caderno 1) 2014. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/servicos_farmaceuticos_atencao_basica_saude.pdf; Accessed 2024.03.29.

- 30.Brasil Conselho Federal de Farmácia. Resolução no 585, de 29 de agosto de 2013. Ementa: Regulamenta as atribuições clínicas do farmacêutico e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília - DF, 27 nov. 2013. 2013. https://www.cff.org.br/userfiles/file/resolucoes/585.pdf Accessed 2024. 03.31.

- 31.Destro D.R., Vale S.A., do Brito M.J.M., Chemello C. Desafios para o cuidado farmacêutico na Atenção Primária à Saúde. Physis. 2021;31 doi: 10.1590/S0103-73312021310323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mekonnen A.B., Yesuf E.A., Odegard P.S., Wega S.S. Pharmacists' journey to clinical pharmacy practice in Ethiopia: key informants' perspective. SAGE Open Med. 2013;1 doi: 10.1177/2050312113502959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Portaria no 154, de 24 de janeiro de 2008. Cria os Núcleos de Apoio à Saúde da Família - NASF. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília-DF, 25 jan. 2008. 2008. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2008/prt0154_24_01_2008.html Accessed 2024.04.29.

- 34.Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Portaria no 472, de 31 de maio de 2023. Altera a Portaria SAES/MS n° 37, de 18 de janeiro de 2021, visando a identificação das equipes Multiprofissionais na Atenção Primária à Saúde no Cadastro Nacional de Estabelecimentos de Saúde (CNES). Diário Oficial da União. Brasília-DF, 02 jun. 2023. 2023. https://bvs.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/saes/2023/prt0472_02_06_2023.html Accessed 2024.04.29.

- 35.Wu M.J., Zhao K., Fils-Aime F. Response rates of online surveys in published research: a meta-analysis. Computers Hum Behav Rep. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.