Abstract

A series of ester derivatives with hydroxyl groups were created by esterification of 1,2-propanediol and glycerol with o-toluoyl chloride via the catalyst 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP). All the compounds were verified using nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR, 13C NMR), infrared spectroscopy, and high resolution mass spectrometry. Moisture absorption and desorption experiments were carried out on the compounds’ pure systems and their systems in reconstituted tobacco, while their hygroscopicity and moisturizing properties were evaluated using low-field nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Two compounds with better absorption and moisture retention were selected: 4 (1-hydroxypropan-2-yl 2-methylbenzoate) and 6 (2,3-dihydroxypropyl 2-methylbenzoate), respectively. Moreover, the thermal stability of compounds 4 and 6 were investigated using thermogravimetric (TG) analysis. The results of TG-DTG showed that the maximum mass loss rate of compound 4 appeared at 251.67 °C, with a mass loss rate of 87.61%. At the peak temperature of 291.83 °C, 6 showed the highest decomposition rate with 49.23% mass loss rate. To explore the antioxidant properties, we constructed three different antioxidant systems. Furthermore, compound 6 showed excellent effects, with scavenging rates reaching 69.28%, 71.92%, and 75.93%, respectively. Smoke volume results indicated that the compounds optimally replaced propanediol and glycerol at a rate of 40%. The results provide a theoretical reference for the development of new moisturizing agents based on polyol esters in the tobacco industry.

1. Introduction

Heating noncombustible cigarettes (HNB) are novel tobacco products that employ a heat source to warm tobacco flakes, also referred to as reconstituted tobacco leaves. The smoke temperature of HNB cigarettes typically remains below 350 °C, thereby minimizing the production of harmful components associated with the high-temperature combustion of conventional cigarettes.1 HNB mostly use large amounts of propanediol and glycerol as smoking agents to increase smoke concentration. Moisture content is an important factor affecting the quality of heated noncombustible cigarettes.2 The polyhydroxy structure of propanediol and glycerol in the actual production of cigarettes can effectively mitigate of water loss behavior in reconstituted tobacco by generating hydrogen bonding forces with water molecules,3 thus reducing the water loss in the tobacco.4,5 However, the excessive application of propanediol and glycerol has resulted in moisture and mildew in the storage of tobacco due to their strong hygroscopic ability and even affects the smoking effect and smoking taste of the cigarettes. Developing new humectants with moderate moisture absorption performance has become a hot research topic in the tobacco industry.

It has been found that approximately half of the mass of glycerol corresponds to oxygen atoms,6,7 making glycerol molecules excellent raw materials for synthesizing ethers, acetals, ketones, and esters through catalyzed reactions with alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids or methyl esters, respectively.8−10 Synthesis of compounds by splicing propanediol and glycerol with flavor molecules has been reported to reduce the strong hygroscopicity of the synthetic feedstock while allowing for the release of flavors by cracking at elevated temperatures.11,12 Antioxidants prevent free radical damage and inhibit the oxidation of other molecules by preventing and reducing the oxidation of large molecules.13,14 One of the main reasons for preventing food and drugs from spoilage during processing and storage is that antioxidant compounds can eliminate free radicals and extend shelf life by delaying lipid peroxidation.15 Antioxidants could protect the human body from the effects of free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS), reduce the harmful effects of ROS during the oxidation process, and thus delay some chronic diseases.16,17

Based on this, this study directly synthesized ester derivatives with hydroxyl groups using propanediol, glycerol, and o-toluoyl chloride as raw materials. And their effects on the hygroscopicity of reconstituted tobacco were investigated by using dry basis water content and low-field NMR18,19 techniques under hygroscopic desorption experiments. The thermal stability of the synthesized compounds was also explored by TG-DTG. In addition, the inhibition of three free radicals 1,1-diphenyl-2-trinitrophenylhydrazine radical (DPPH•), hydroxyl radical (OH•), and superoxide anion radical (O2•–) in vitro was probed by using different methods, which in turn evaluated the antioxidant activity of the obtained compounds.

2. Materials and Methods

Reconstituted tobacco was offered by the Technology Center of China Tobacco Henan Industry Co., Ltd. In addition to what is mentioned in ref (11), it also uses UV visible spectrophotometer Thermo Evolution 201 (Thermo, USA), Multifunctional enzyme labeler (ELX808, Bio Tek, USA), Lab Coater (MS-ZN320A, Bo Sen, China), Automatic Mini Tobacco Shredder (Jie Li, China), and Heated Cigarette Smoke Transmission Tester (VDM100, Yi Zhong, China).

2.1. Preparation of Compounds

DMAP (4-dimethylaminopyridine, 2 mmol, 0.2443 g), 1,2-propanediol or glycerol (1 mmol, 0.0761 or 0.0921 g), o-toluoyl chloride (0.5 mmol, 0.0773 g), and TEA (triethylamine, 0.5 mmol, 0.0506 g) were added to anhydrous DCM (dichloromethane, 5 mL) under no water and oxygen conditions. Then the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction process was monitored using the TLC method. After the reaction is completed, the liquid mixture was evaporated and 20 mL of ice water was added to terminate the reaction. Ethyl acetate was added to the separating funnel for extraction, the water layer was extracted with ethyl acetate three times, the ester layer was extracted twice with 1 mol/L HCl and saturated NaCl, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4 for 24 h, and concentrated. Pure polyol esters were purified by column chromatography on silica gel (100 mesh). Scheme 1 is the reaction route. 1H NMR, 13C NMR, infrared spectroscopy (IR), and high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) of synthesized compounds 4–8 could be checked in the Supporting Information (Figures S1–S20).

Scheme 1. Substrate Range of Polyols and o-Toluoyl Chloride Esterification Reaction.

2.2. Structural Characterization Data

2.2.1. 1-Hydroxypropan-2-yl 2-Methylbenzoate (4)

1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 7.85–7.78 (m, 1H), 7.33–7.26 (m, 1H), 7.14 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.20 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.12–4.03 (m, 2H), 2.50 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 3H), 1.26 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 1.20–1.17 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 167.68, 140.25, 132.18, 131.75, 130.60, 125.75, 69.85, 66.12, 21.77, 19.39. IR (KBr) v: 3401, 2967, 2392, 2333, 2153, 2021, 1707, 1250, 1081, 735, 662 cm–1. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H14NaO3 [M + Na]+, 217.0835; found [M + Na]+, 217.0849.

2.2.2. Propane-1,2-diyl Bis(2-methylbenzoate) (5)

1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 7.83 (ddd, J = 7.8, 3.8, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (dd, J = 7.5, 3.6 Hz, 4H), 5.45 (pd, J = 6.5, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.45–4.33 (m, 2H), 2.50 (s, 6H), 1.39 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.20, 166.97, 140.42, 140.16, 132.11 (d, J = 15.3 Hz), 131.72 (d, J = 4.8 Hz), 130.68 (d, J = 14.4 Hz), 129.69, 129.18, 125.75 (d, J = 3.1 Hz), 68.72, 66.50, 29.73, 21.79 (d, J = 8.7 Hz), 16.84. IR (KBr) v: 2983, 1718, 1519, 1247, 1076, 734, 672, 536 cm–1. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H20NaO4 [M + Na]+, 335.1254; found [M + Na]+, 335.1250.

2.2.3. 2,3-Dihydroxypropyl 2-Methylbenzoate (6)

1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 7.78 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (dt, J = 8.4, 4.2 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (s, 1H), 3.73–3.49 (m, 2H), 2.44 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.83, 140.35, 132.31, 131.75, 130.71, 128.99, 125.77, 70.32, 65.41, 63.58, 21.77. IR (KBr) v: 3378, 2910, 2150, 1705, 1503, 1256, 1164, 1073, 734 cm–1. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H14NaO4 [M + Na]+, 233.0784; found [M + Na]+, 233.0801.

2.2.4. 2-Hydroxypropane-1,3-diyl Bis(2-methylbenzoate) (7)

1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 7.92–7.80 (m, 2H), 7.34 (tt, J = 7.8, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 4H), 5.39 (p, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 2.52 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 140.55 (d, J = 6.7 Hz), 132.40 (d, J = 1.9 Hz), 131.82, 130.88–130.61 (m), 128.92 (d, J = 17.7 Hz), 125.82, 72.85, 62.63, 61.75, 21.83 (d, J = 2.9 Hz). IR (KBr) v: 3422, 2926, 1718, 1525, 1239, 1191, 1066, 734, 573 cm–1. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H20NaO5 [M + Na]+, 351.1202; found [M + Na]+, 351.1220.

2.2.5. 3-Hydroxypropane-1,2-diyl Bis(2-methylbenzoate) (8)

1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (td, J = 7.5, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 4.46–4.33 (m, 4H), 4.28 (q, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.52 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d): δ 167.56, 140.48, 132.37, 131.82, 130.72, 128.93, 125.82, 68.54, 65.68, 21.83. IR (KBr) v: 3434, 2953, 2146, 1708, 1502, 1250, 1176, 1081, 738, and 590 cm–1. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H20NaO5 [M + Na]+, 351.1202; found [M + Na]+, 351.1220.

2.3. Hygroscopicity and Moisturizing

2.3.1. Determination of Moisture Absorption and Retention Properties of Compounds

0.5 g of compounds 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, propanediol, and glycerol were loaded into weighing flasks and placed in a desiccator containing saturated potassium chloride solution and weighed at regular intervals. Three sets of parallel experiments were set up, and the moisture absorption rate (Ra) of the compounds was calculated and averaged; the formula for Ra is shown in (eq 1)

| 1 |

where m0 is the initial mass of the sample (g) and mt is the mass of the sample at a certain time point (g).

The compounds were dissolved in anhydrous ethanol and prepared as a 2% (w/w) solution, equilibrated for 48 h. About 1.0 g of compound solution was weighed in a weighing flask, which had been weighed at a constant weight and then desorbed in a desiccator containing saturated magnesium chloride (33% RH), which was taken out at regular intervals to weigh accurately. Three groups of parallel experiments were set up and the humidity retention rate (Rr) of the compounds was calculated and averaged, Rr was calculated as in (eq 2)

| 2 |

where m0 is the initial mass of the sample (g) and mt is the mass of the sample at a certain time point (g).

2.3.2. Determination of Moisture Absorption and Retention Properties of Compounds in the System of Reconstituted Tobacco Filaments

The tobacco shreds were placed at (22 ± 1) °C and (60 ± 2)% to reach equilibrium after 48 h. On this basis, a solution was prepared according to the product quality of 2% by weight of tobacco and sprayed uniformly on the reconstituted tobacco shreds with the identical mass of propanediol, glycerol, and water as controls. The shredded tobacco were laid at (22 ± 1) °C and (60 ± 2)% for 72 h. In addition to this, the equilibrated tobacco shreds were divided evenly into three differential treatments and subjected to initial moisture content determination, while the remaining two groups were kept in desiccators containing saturated potassium chloride (temperature at (22 ± 1) °C and relative humidity at (84 ± 2)%) and saturated magnesium chloride (temperature at (22 ± 1) °C and relative humidity at (32 ± 2)%) solutions for hygroscopicity and desorption experiments, respectively. The moisture content of each treatment was calculated based on the change in weight at different times.

2.3.3. LF-NMR Analysis

1.5 g of each group of well-equilibrated tobaccos were weighed in different humidity environments as described above, respectively. They were then placed into NMR sample tubes for analysis, and the data were captured and subjected to three parallel experiments using the CPMG pulse sequence, which have been set in reference.11

2.4. TG Analysis

5 mg portion of the compound was weighed and heated from 30 to 450 °C in an air atmosphere at a flow rate of 60 mL min–1 and a heating rate of 10 °C min–1, and the TG curves of the substances were determined using spectroscopically pure Al2O3 as a reference substance (STA 449 F3, Netzsch, Germany).

2.5. Antioxidant Activity Test

2.5.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Ability

The DPPH radical scavenging ability was measured refering to the method of Joubert.20 Compound samples were prepared with different concentrations (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mg/mL) by using distilled water. 0.5 mL of compound samples were taken with different concentrations. 2.0 mL of 0.1 mmol/L DPPH ethanol solution was added and then 1.5 mL of distilled water was added and shaken well. The mixture was quickly oscillated to mix the mixture evenly, and it was left at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a Thermo Evolution 201 UV visible spectrophotometer. Using vitamin C (Vc) as the positive control and glycerol as the control, we repeated the experiment three times for each treatment. The scavenging ratio of compound samples against DPPH radicals was calculated by the following formula

| 3 |

Among them, A2 is the absorbance of 0.5 mL compound sample solution + 2 mL DPPH solution + 1.5 mL distilled water, A1 is the absorbance of 0.5 mL compound sample solution + 2 mL ethanol + 1.5 mL distilled water, and A0 is the absorbance of 2 mL DPPH solution + 2 mL distilled water.

2.5.2. OH• Radical Scavenging Ability

The OH• radical scavenging ability was measured refering to the method of Cheng.21 1.0 mL of 9 mmol/L FeSO4, H2O2, and salicylic acid solutions were added to 1.0 mL of compound solution (0.125–4 mg/mL) and mixed well. The mixture was reacted at 37 °C for 30 min and absorbance measured at 562 nm using an ELX808 Multifunctional enzyme labeler. Vc was set as the positive control and glycerol as the control. Meanwhile, the experiment was repeated three times for each treatment. The scavenging ratio of OH• was calculated using the following formula

| 4 |

where B2 represents the absorbance of 1.0 mL of compound sample solution + 1.0 mL of FeSO4 solution + 1.0 mL of H2O2 + 1.0 mL of salicylic acid solution, B1 represents the absorbance of 1.0 mL of compound sample solution + 1.0 mL of FeSO4 solution + 1.0 mL of H2O + 1.0 mL of salicylic acid solution, and B0 represents the absorbance of 1.0 mL of ethanol + 1.0 mL of FeSO4 + 1.0 mL of H2O2 + 1.0 mL of salicylic acid solution.

2.5.3. Superoxide Anion Radical Scavenging Ability

The property was studied according to the methods reported in the literature and with slight modifications.22,23 30 μL of compound solution (0.125–4 mg/mL) and 150 μL of Tris-HC1 buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH 8.2) were mixed. After shaking, the mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min. Then 30 μL of pyrogallol (6 mmol/L) was added to the reaction mixture, shaken, and continued to be incubated at 25 °C for 5 min. Finally, 30 μL of hydrochloric acid solution (8 mmol/L) was added to end the reaction. Ascorbic acid (Vc) was set as the positive control and glycerol as the control, with test absorbance at 325 nm (OD325nm). The experiment was repeated three times for each treatment. The scavenging ratio of superoxide radicals was calculated using the following formula

| 5 |

where Cs represents the absorbance value of the sample reaction solution, Cb represents the absorbance value of the blank solution, and Cc represents the absorbance value of the sample solution without the addition of pyrogallol.

2.6. Smoke Volume Test

2.6.1. Reconstituted Tobacco Production

Reconstituted tobacco was produced according to the thick pulp production process: first, 10.4 g of outer fiber, 6 g of concentrate, 210 g of water, and 12 g of glycerol or propanediol were put into a blender and blended for 20 min; then 1.5 g of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose was added and blended again for 5 min, and finally 50 g of powdered tobacco was added and blended for 30 min. Set the coating stroke of MS-ZN320A laboratory coating machine to 350 mm, the coating speed to 200 cm/min, and the thickness to 0.7 mm. Pour the prepared slurry onto the coating machine for coating. At this time, the heating switch will automatically heat up to 70 °C. Wait for 5−7 minutes for the coated reconstituted tobacco leaves to dry off excess moisture, and then gently remove the tobacco leaves from the coating machine with a plastic spatula. For the remaining samples, the steps were the same except that the increase or decrease in the amount of glycerol, propylene glycol, and the addition of the resulting compounds were calculated according to the substitution ratio.

2.6.2. Reconstituted Tobacco Smoke Volume Test

The tobacco leaves mentioned above were cut by an automatic miniature tobacco shredder. After passing through the 20-mesh sieve, they were rolled into cigarettes by using a heated cigarette roller and then equilibrated at 40% relative humidity and 22 °C for 24 h. At last, the smoke volume of the cigarettes was detected by the heated cigarette smoke transmittance detector.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Study of Moisture Absorption and Moisture Retention Properties of Products

3.1.1. Study on the Moisture-Proof and Moisture Retention Properties of Compound Pure Systems

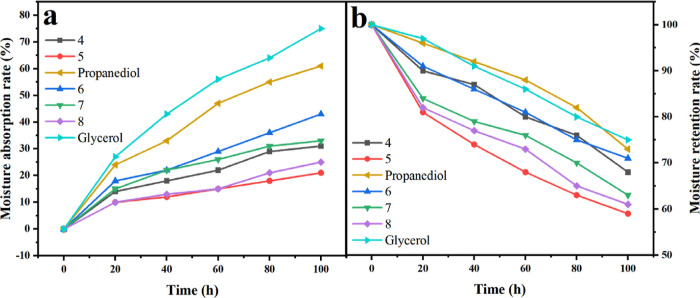

This experiment studied the moisture absorption and wettability of the obtained compound. From Figure 1, when RH = 84%, the moisture absorption rate of the compounds was positively correlated with time. At the beginning of 20 h, the water absorption rate of the sample rapidly increased and tended to equilibrate at 100 h. The compounds were found to be very effective in retaining the moisture. At this time, the moisture absorption rates of compound 4 group, compound 5 group, compound 6 group, compound 7 group, compound 8 group, propanediol group, and glycerol group were 31%, 21%, 43%, 33%, 25%, 61%, and 75%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Variation of moisture absorption and retention rates of the compound pure system ((a): 22 °C, RH = 84%; (b): 22 °C, RH = 32%).

The humidity of the samples was negatively correlated with time in the experimental environment of RH 32% and equilibrated at 100 h. At this time, the humectancies of compound 4 group, compound 5 group, compound 6 group, compound 7 group, compound 8 group, propanediol group, and glycerol group were 68%, 59%, 71%, 63%, 61%, 73% and 75%, respectively. From the analysis of Figure 1, it was obtained that the humectancy and hygroscopicity of the compound-pure system were in the following order from the largest to the smallest: propanediol > 4 > 5 and glycerol > 6 > 7 > 8, regardless of RH = 84% or RH = 32%.

3.1.2. Study on the Moisture and Humidity Retention Properties of Compounds in the System of Reconstituted Tobacco Filaments

The moisture absorption and moisturizing properties of the products were examined, and the results are shown in Figure 2. The dry-base moisture content of the reconstituted tobacco shred samples increased over time at a relative humidity of 84%. The samples exhibited a consistent upward trend in the first 40 h and then reached equilibrium after 120 h. At this time, the dry-base moisture contents of the reconstituted tobacco shreds of the propanediol group, the 4 group, the 5 group, the 6 group, the 7 group, the 8 group, the glycerol group, and the control group were 15.21%, 14.97%, 18.43%, 19.10%, 17.91%, 16.27%, 20.03%, and 14.03%, separately. It was found that at 32% RH, the moisture content gradually decreased with the extension of time, then showed a parabolic decline after 10 h, and was basically stable after 120 h. The moisture content of the samples in the two different humidity environments was in the same order of propanediol > 4 > control; glycerol > 6 > 8 > control.

Figure 2.

Moisture content at 22 °C, RH = 84% (a); RH = 32% (b).

From Figure 2, sprayed 4 and 6 tobacco shred samples showed better moisture absorption and retention properties than the control samples but less than glycerol. Propanediol and glycerol as traditional moisturizing agents could bind water through hydrogen bonding to enhance the water adsorptive capacity of tobacco to increase the water content. In comparison with propanediol and glycerol, synthetic compounds 4 and 6 diminished the amount of hydroxyl groups and hydrogen bonds, significantly reducing the raw materials’ hygroscopicity,11 while also having a certain moisture-proof and moisturizing ability.

3.1.3. Studies on the Distribution and Transport of Water in Reconstituted Tobacco Shreds with Different Moisturizing Agents

The T2 relaxation time reflected the multifunctionality of the proton molecules associated with spin–spin interactions.24 The variation of the relaxation time responded to the mobility of water as well as how strongly it was bound to the reconstituted tobacco shreds. The results showed that each sample had two significant hydrogen proton relaxation peaks, which corresponded to T21 and T23, representing two distinct conditions of existence of water. T21 was the quickest relaxation peak, with times ranging from 0.01 to 1 ms, and T23 was the slowest relaxation peak, with times ranging from 10 to 100 ms.25 It was widely believed that T21 was bound to water that can form complexes with hydrophilic components such as sugar, pectin, cellulose, etc. T23 represents free water. The water content could be calculated from the size of the peak area. An increase in peak area correlated with an increase in moisture content.26−28

From Figure 3, the peak of bound water (T21) dominated the two states of moisture of the tobacco shreds with different moisturizing agents in 84% RH (a) and 32% RH (b). The orders of moisture content of shredded tobacco with various moisturizing agent treatments were all propanediol > 4 > 5 > control; and glycerol > 6 > 7 > 8 > control. This phenomenon occurred mainly owing to the high content of hydroxyl groups in the materials propanediol and glycerol compared with the synthetic esters, which caused the hydrogen bonding between tobacco and water to be enhanced. As a result, the intermolecular forces were enhanced, the water content of the shredded tobacco binding was increased, and the hygroscopicity of the shredded tobacco was improved.29,30 Different moisturizing agents had different affinities for water, and their effects on the state of bound water varied, leading to significant changes in the distribution of T2 relaxation times.31 The relaxation rates of the T21 and T23 peaks of tobacco treated with the moisturizing agents were significantly accelerated compared with the control under different humidity conditions, indicating enhanced water stability. In addition, the T21 peak area of the monoester 4 sample was more than that of the diester 5 sample under two RH conditions, and the T21 peak area of the monoester 6 was higher than that of the diester 7 and 8 samples, which demonstrated that there was more bound water in the monoester samples, and thus, the 4 and 6 samples possessed stronger hygroscopicity and water retention properties.

Figure 3.

T2 relaxation time at 22 °C, RH = 84% (a), RH = 32% (b).

The bound water content of different groups of reconstituted tobacco shreds and the control group was measured under two different conditions. At 84% RH and 22 °C (Figure 4a), the bound water contents were as follows: 0.7943 for group 4, 0.7451 for group 5, 0.832641682 for propanediol reconstituted tobacco shreds group, 0.9115 for group 6, 0.9054 for group 7, 0.8063 for group 8, 0.9447 for glycerol reconstituted tobacco shreds group, and 0.7062 for the control group. On the other hand, at 32% RH and 22 °C, the bound water contents were 0.6736 for group 4, 0.6326 for group 5, 0.7002 for propanediol reconstituted tobacco shreds group, 0.7374 for group 6, 0.7201 for group 7, 0.7090 for group 8, 0.8228 for glycerol reconstituted tobacco shreds group, and 0.5392 for the control group (Figure 4b). This result was in agreement with the previous test results that compounds 4 and 6 were effective in inhibiting the strong hygroscopic properties of propanediol and glycerol, while retaining certain hygroscopic properties compared to the other groups.11

Figure 4.

Proportion of water content at 22 °C, RH = 84% (a), RH = 32% (b).

3.2. TG-DTG Analysis of 4 and 6

From Figure 5, compound 4 underwent the mass change phase between 106.5 and 450 °C; meanwhile, the mass loss process of 6 occurred between 177.5 and 450 °C, which were higher than the weight loss interval of 1,2-propanediol and propanetriol,32,33 indicating that the esterification reaction effectively improved the thermal stability of the target compounds. Among them, 4 reached the mass loss’ maximum rate at 251.67 °C with a total weight loss of 87.61%, while compound 6 was 291.83 °C with 99.85% total weight loss. It is hypothesized that this apparent difference may be related to molecular weight size and structure. The molecular weight of 6 is greater than that of 4, which enhances the stability of 6, resulting in a higher mass loss temperature for the malonyl monoester compound 6 than for the product monoester 4 synthesized with 1,2-propanediol.

Figure 5.

TG-DTG curves of compounds 4 and 6.

3.3. Antioxidant Activity Test

3.3.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Ability

DPPH is a useable organic nitrogen radical that can accept an electron or hydrogen radical to become a stable molecule.34 The delocalization of electrons results in a deep purple color, which is characterized by an absorption band centered at approximately 517 nm in organic solutions. When antioxidant molecules capable of providing hydrogen atoms are mixed with a DPPH radical solution, it undergoes reduction and loses its purple color.35 The free radical elimination reaction is one of the main mechanisms that inhibit the body’s peroxidation process. The ability of a sample to eliminate free radicals reflects its antioxidant activity. DPPH free radical elimination ability is the simplest and most extensive method for evaluating in vitro antioxidant activity.

The results of the compound sample’s ability to scavenge DPPH organic radicals are shown in Figure 6. Within a certain concentration range, the scavenging efficiency of compound samples toward DPPH increases with the increase of their concentration. At the same concentration, the scavenging ratio of 6 was higher than that of other samples, and the highest clearance efficiency was first achieved at 69.28 ± 0.28%. As a control group, Vc had a significantly higher DPPH scavenging effect than 1,2-propanediol, glycerol, and any group of synthesized compound samples. At a concentration of 0.125 mg/mL, the scavenging ratio of Vc reached 95%. After comparison, it was found that the esterified compounds had better DPPH scavenging ability than the synthetic raw material glycerol. According to GraphPad Prism, the IC50 of 6 was 0.06452. The lower the IC50, the higher the efficiency of free radical scavenging.36,37

Figure 6.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of compounds.

3.3.2. OH• Radical Scavenging Ability

Hydroxyl radicals (OH•) are the neutral forms of hydroxide ions (OH–). These free radicals have strong reactivity and are easily converted into hydroxyl groups, resulting in a short lifespan. Research had shown that human cells are attacked daily by hydroxyl radicals (OH•) and other free radicals, inducing an average of 105 times the stress produced by oxidation.38 As the most active type of ROS, clearing hydroxyl radicals is crucial for protecting the human body.39

As shown in Figure 7, all samples had a certain scavenging effect on the hydroxyl radicals (OH•). Ester derivatives 4 and 6 had better antioxidant activity than 1,2-propanediol and glycerol, but still weaker than the scavenging ability of Vc. At the same time, in addition to Vc, the scavenging ability of compound samples toward hydroxyl radicals gradually increased in a concentration-dependent manner. At a concentration of 4.0 mg/mL, the scavenging ratios of each sample were 61.76 ± 0.12%, 71.92 ± 0.036%, 24.34 ± 0.17%, 33.07 ± 0.11%, and 96.65 ± 0.12%, respectively. Therefore, the scavenging effect of each sample on hydroxyl radicals was as follows: Vc > 6 > 4 > glycerol > 1,2-propanediol. Through comparison, it was found that compound 6 had a higher OH• radial scavenging ability. Modified alcohol compounds with ester groups had stronger ability to scavenge hydroxyl radicals, mainly due to the presence of intermediate electron-donating acyloxy groups on the molecule, which can reduce free radicals and prevent their chain reactions. According to GraphPad Prism, the IC50 of 6 was 1.167.

Figure 7.

OH• radical scavenging activity of compounds.

3.3.3. Superoxide Anions’ Radical Scavenging Ability

The superoxide anion is a precursor of active free radicals with the potential to react with biomolecules to induce tissue damage. O2•– is a free radical centered on oxygen, with selective reactivity. It is generated by giving oxygen an electron in the body. Although superoxide is a relatively weak oxidant with limited chemical reactivity, it can produce more dangerous substances, including 1O2 and OH•, which could lead to lipid peroxidation.

The results of the compound sample’s ability to scavenge superoxide anion are shown in Figure 8, and the ability of each sample to scavenge superoxide radicals increased with the increase of concentration. Within the concentration range of 0.125–4.0 mg/mL, the scavenging ratio of Vc increased from 69.55 ± 0.67 to 96.15 ± 0.06%, the scavenging ratio of 6 increased from 60.57 ± 1.07 to 75.93 ± 0.27%, the scavenging ratio of 4 increased from 42.95 ± 3.29 to 74.49 ± 0.93%, the scavenging ratio of 1,2-propanediol increased from 12.65 ± 6.71 to 72.58 ± 0.93%, and the scavenging ratio of glycerol increased from 64.35 ± 0.25 to 69.65 ± 0.42%. The results showed that at the same concentration, the superoxide radical scavenging activity of the esterified samples was stronger than that of synthesized raw alcohol, but all were lower than control Vc. The mechanism of compound scavenging superoxide anion may be related to the difficulty of breaking the O–H bond in the molecule. The easier the molecules’ O–H bonds are broken, the stronger their ability to scavenge superoxide radicals. When compounds contain fewer electron-donating groups, the easier the O–H bonds are broken.40 Therefore, the scavenging ratio of 6 was significantly enhanced at 2.0 mg/mL higher than 4, 1,2-propanediol and glycerol. According to GraphPad Prism, the IC50 of 6 was 0.01927.

Figure 8.

Superoxide anions radical scavenging activity of compounds.

3.4. Smoke Volume Test

The effects of different substitution ratios and different compounds on smoke volume were investigated by a single substitution of propylene glycol and glycerol. From Figure 9, the smoke volume of all samples showed a tendency of increasing and then decreasing with the increase of the number of puffs. All samples, except for glycerol, reached the maximum smoke volume at the second puff and 0 at the fifth puff. As the substitution ratio increased, the smoke volume of all samples also increased and reached the maximum smoke volume at a 40% substitution ratio. However, when the substitution ratio increased to 50%, the smoke levels of all samples showed a decreasing trend. The reason for this may be that the substitution ratio is too high and the amount of glycerol and propanediol is too low, resulting in poor smoke production. When the substitution ratio is 40%, the maximum values of smoke volume of propanediol, glycerol, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 samples are 51.30, 77.85, 41.02, 26.46, 61.9, 29.26, and 27.74.

Figure 9.

Effect of different compounds on smoke production of cigarettes at each substitution ratio, (a) 20%, (b) 30%, (c) 40%, (d) 50%; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 are the puff numbers.

4. Conclusions

In summary, five polyol ester compounds were designed, synthesized, and validated through 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR, and HRMS. The effect of polyol esters on the moisture absorption performance of shredded tobacco was examined through hygroscopic desorption experiments and LF-NMR. The findings revealed that compounds 4 and 6 exhibited desirable moisture-proof and moisturizing properties, aligning with the initial design goals of reducing the hygroscopicity of polyols while also providing a certain moisturizing effect. From the TG-DTG results, it was found that with the increase of temperature, the mass loss of compound 4 decreased sharply by 97.17%, and the mass loss of compound 6 decreased sharply by 99.85%. Moreover, the scavenging activities of compounds 4 and 6 on DPPH, hydroxyl, and superoxide anion radicals were investigated. The results indicated that the compounds exhibited in vitro antioxidant activity, which was higher than that of the synthetic raw material polyol but lower than that of Vc. Specifically, compound 6 demonstrated excellent scavenging abilities for DPPH, hydroxyl radical, and superoxide anion, with IC50 values of 0.06452, 1.167, and 0.01927, respectively. The effect of the synthesized compounds on the smoke volume of heated cigarettes was investigated by smoke volume assay, and the optimum replacement polyol was found to be 40%. The polyol ester compounds in this study had good effects on waterproofing and moisturizing of shredded tobacco and could solve the trouble of shortened shelf life, moldy tobacco, and poor sensory caused by the strong hygroscopicity of propanediol and glycerol in the application process. The excellent antioxidant properties of the target compound were expected to be applied in the food and industrial fields, but its safety still needs further research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to China Tobacco Henan Industrial Co., Ltd. for support by grant number (2023410001340030).

Data Availability Statement

All the data used to confirm the results obtained in this study are included within the manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c05199.

Copies of 1H, 13C NMR, IR and HRMS spectra of the products 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ Z.G., L.H., and J.W. contributed equally to this study and share first authorship. Haiying Tian: First draft, conceptualization, and methodology in writing. Ziting Gao: Writing first draft, revision, investigation, and editing. Lu Han: Methodology, investigation. Jiqiang Wan: Data curation, methodology. Xiaopeng Yang: revision, investigation. Mengxue Li: Data curation, investigation. Wenjuan Chu: Formal analysis, methodology in writing. Miao Lai: Review & editing, conceptualization. Xiaoming Ji: Review & editing, conceptualization.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Simonavicius E.; McNeill A.; Shahab L.; Brose L. S. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: a systematic literature review. Tobac. Control 2019, 28, 582–594. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. H.; Zhang Y.; Zhong H. Y.; Zhu H.; Wang H.; Goh K. L.; Zhang J.; Zheng M. Efficient and sustainable preparation of cinnamic acid flavor esters by immobilized lipase microarray. LWT 2023, 173, 114322. 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.114322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunia-Krzyzak A.; Sloczynska K.; Popiol J.; Koczurkiewicz P.; Marona H.; Pękala E. Cinnamic acid derivatives in cosmetics: current use and future prospects. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2018, 40, 356–366. 10.1111/ics.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L.; Wang Y.; Tang Q.; Zhang R.; Zhang D.; Zhu G. Structural characterization of a Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua Tuber polysaccharide and its contribution to moisture retention and moisture-proofing of porous carbohydrate material. Molecules 2022, 27, 5015. 10.3390/molecules27155015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills B. Applications of low-field NMR to food science. Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 2006, 58, 177–230. 10.1016/S0066-4103(05)58004-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behr A.; Eilting J.; Irawadi K.; Leschinski J.; Lindner F. Improved utilisation of renewable resources: new important derivatives of glycerol. Green Chem. 2008, 10, 13–30. 10.1039/B710561D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva C. R. B.; Gonçalves V. L. C.; Lachter E. R.; Mota C. J. A. Etherification of glycerol with benzyl alcohol catalyzed by solid acids. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2009, 20, 201–204. 10.1590/s0103-50532009000200002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. L.; Pang J. Y.; Lou J. C.; Sun W. W.; Liu J. K.; Wu B. Chemo- and site-selective fischer esterification catalyzed by B(C6F5)3. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1424–1427. 10.1002/ajoc.202100188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baião Ferreira F.; da Silva M. J.; Rodrigues F. d. Á.; da Silva Faria W. L. Sulfated-alumina-catalyzed triacetin synthesis: an optimization study of glycerol esterification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 4235–4243. 10.1021/acs.iecr.1c04782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qatrinada; Setyaningsih D.; Aminingsih T. Application of MAG (monoacyl glycerol) as emulsifier with red palm oil in body cream product. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 749, 012066. 10.1088/1755-1315/749/1/012066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z.; Chu W.; Han L.; Wan J.; Li M.; Yang X.; Guo Q.; Lu H.; Ji X.; Tian H.; et al. Analysis of hygroscopicity and pyrolysis behaviour of propanediol esters synthesized by the enzymatic method. Flavour Fragrance J. 2023, 39, 125–135. 10.1002/ffj.3771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W.; Tian H.; Chen H.; Chu W.; Han L.; Li P.; Gao Z.; Ji X.; Lai M. Moisture property and thermal behavior of two novel synthesized polyol pyrrole esters in tobacco. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 4716–4726. 10.1021/acsomega.2c06683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawbaa S.; Nuha D.; Evren A. E.; Cankiliç M. Y.; Yurttaş L.; Turan G. New oxadiazole/triazole derivatives with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1282, 135213. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weng L. M.; Xiao Z. W.; Li L.; Ji L. L.; Sun P. Y.; Chen Z. Y.; Liang Y.; Li B.; Zhang X. Caffeoyl fatty acyl structural esters:enzymatic synthesis, characterization and antioxidant assessment. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104214. 10.1016/j.jff.2020.104214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Cabrera D.; Santa-Helena E.; Leal H. P.; de Moura R. R.; Nery L. E. M.; Gonçalves C. A. N.; Russowsky D.; Montes D’Oca M. G. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of new lipophilic dihydropyridines. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 84, 1–16. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmakci S.; Topdaş E. F.; Kalın P.; Han H.; Şekerci P.; Köse L. P.; Gülçin İ. Antioxidant capacity and functionality of oleaster (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.) flour and crust in a new kind of fruity ice cream. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 472–481. 10.1111/ijfs.12637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gocer H.; Akıncıoğlu A.; Oztaşkın N.; Göksu S.; Gülçin İ. Synthesis, antioxidant and antiacetylcholinesterase activities of sulfonamide derivatives of dopamine related compounds. Arch. Pharm. 2013, 346, 783–792. 10.1002/ardp.201300228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H.; Lu T.; Wu X.; Jiang C.; Gu C.; Zhang K.; Jin J. Synthesis of C-ring hydrogenated sinomenine cinnamate derivatives via Heck reactions. J. Chem. Res. 2019, 43, 469–473. 10.1177/1747519819868201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.; Lin Z. Y.; Cheng S. S.; Abd El-Aty A. M.; Tan M. Q. Effect of water-retention agents on Scomberomorus niphonius surimi after repeated freeze-thaw cycles: low-field NMR and MRI studies. Int. J. Food Eng. 2023, 19, 15–25. 10.1515/ijfe-2022-0270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert E.; Winterton P.; Brit T. J.; Ferreira D. Superoxide anion and a-diphenyl-b-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging capacity of rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) aqueous extracts, crude phenolic fractions, tannin and flavonoids. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.; Huang G. Extraction, characterisation and antioxidant activity of Allium sativum polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 415–419. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang S.; Cheng X.; Zhu N.; Stark R. E.; Badmaev V.; Ghai G.; Rosen R. T.; Ho C. T. Flavonol glycosides and novel iridoid glycoside from the leaves of Morinda citrifolia. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4478–4481. 10.1021/jf010492e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zin Z. M.; Abdul Hamid A.; Osman A. Antioxidative activity of extracts from Mengkudu (Morinda citrifolia L.) root, fruit and leaf. Food Chem. 2002, 78, 227–231. 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00402-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G.-f.; Li B.; Liu C.; Jin X.; Wang Z.-g.; Ding M.-z.; Chen L.-y.; Zhang M.-j.; Zhu W.-k.; Han L.-f. Characterization of moisture mobility and diffusion in fresh tobacco leaves during drying by the TG-NMR analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 135, 2419–2427. 10.1007/s10973-018-7312-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.; Yang S.; Li X.; Chen F.; Zhang M. Dynamics of water mobility and distribution in soybean antioxidant peptide powders monitored by LF-NMR. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 280–286. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S.; Tian B. Q.; Jia H. F.; Zhang H. Y.; He F.; Song Z. P. Investigation on water distribution and state in tobacco leaves with stalks during curing by LF-NMR and MRI. Dry. Technol. 2018, 36, 1515–1522. 10.1080/07373937.2017.1415349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell C. K.; Allen P.; Duggan E.; Arimi J. M.; Casey E.; Duane G.; Lyng J. G. The effect of salt and fibre direction on water dynamics, distribution and mobility in pork muscle: a low field NMR study. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 51–58. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S.; Tian B.; Jia H.; Zhang H.; He F.; Song Z. Investigation on water distribution and state in tobacco leaves with stalks during curing by LF-NMR and MRI. Dry. Technol. 2018, 36, 1515–1522. 10.1080/07373937.2017.1415349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z. T.; Han Lu.; Wan J. Q.; Fu G.; Yang X.; Guo Q.; Ji X.; Chu W.; Tian H.; Lai M. Analysis of water adsorption capacity and thermal behavior of porous carbonaceous materials by glycerol ester. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105789. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C. F.; Qian P.; Meng J.; Gao S. M.; Lu R. R. Effect of glycerol and sorbitol on the properties of dough and white bread. Cereal Chem. 2016, 93, 196–200. 10.1094/CCHEM-04-15-0087-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Liu Y.; Wang N.; Ruan R. NMR technique application in evaluating the quality of navel orange during storage. Procedia Eng. 2012, 37, 234–239. 10.1016/j.proeng.2012.04.233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nowosielski B.; Warmińska D.; Cichowska-Kopczyńska I. CO2 separation using supported deep eutectic liquid membranes based on 1,2-propanediol. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 4093–4105. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c06278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almazrouei M.; Adeyemi I.; Janajreh I. Thermogravimetric assessment of the thermal degradation during combustion of crude and pure glycerol. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 12, 4403–4417. 10.1007/s13399-022-02526-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.; Zhang N.; Wang D. X.; Jiao L.; Tan Y.; Wang J.; Li H.; Wu W.; Jiang D. C. Structural analysis and antioxidant activities of neutral polysaccharide isolated from Epimedium koreanum Nakai. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 246–253. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam N.; Bristi N. J.; Rafiquzzaman M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 2013, 21, 143–152. 10.1016/j.jsps.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes L. M.; Segundo M. A.; Reis S.; Lima J. L. F. C. Methodological aspects about in vitro evaluation of antioxidant properties. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 613, 1–19. 10.1016/j.aca.2008.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Liang L.; Han C. Borate suppresses the scavenging activity of gallic acid and plant polyphenol extracts on DPPH radical: a potential interference to DPPH assay. LWT 2020, 131, 109769. 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carocho M.; Ferreira I. C. F. R. A review on antioxidants, prooxidants and related controversy: natural and synthetic compounds, screening and analysis methodologies and future perspectives. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 15–25. 10.1016/j.fct.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S.-G.; Jia S.-R.; Wu Y.-K.; Yan R.-R.; Lin Y.-H.; Zhao D.-X.; Han P.-P. Effect of culture conditions on the physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from Nostoc flagelliforme. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 198, 426–433. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q.; Xie Y.; Wang W.; Yan Y.; Ye H.; Jabbar S.; Zeng X. Extraction optimization, characterization and antioxidant activity in vitro of polysaccharides from mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 128, 52–62. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data used to confirm the results obtained in this study are included within the manuscript.