Abstract

Termites digest wood using Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZymes) produced by gut bacteria with whom they have cospeciated at geological timescales. Whether CAZymes were encoded in the genomes of their ancestor’s gut bacteria and transmitted to modern termites or acquired more recently from bacteria not associated with termites is unclear. We used gut metagenomes from 195 termites and one Cryptocercus, the sister group of termites, to investigate the evolution of termite gut bacterial CAZymes. We found 420 termite-specific clusters in 81 bacterial CAZyme gene trees, including 404 clusters showing strong cophylogenetic patterns with termites. Of the 420 clusters, 131 included at least one bacterial CAZyme sequence associated with Cryptocercus or Mastotermes, the sister group of all other termites. Our results suggest many bacterial CAZymes have been encoded in the genomes of termite gut bacteria since termite origin, indicating termites rely upon many bacterial CAZymes endemic to their guts to digest wood.

Subject terms: Coevolution, Phylogenetics

The phylogenetic trees of prokaryotic CAZymes found in termite gut mirror the termite phylogeny, suggesting termites rely on many CAZymes that were already encoded in the genomes of the ancestors of their gut prokaryotes.

Introduction

Termites, the oldest lineage of social insects with a fossil record dating back ~130 million years ago1, are best known for their xylophagous habits. They descend from a wood-feeding cockroach ancestor2,3, a diet many species have retained, except in the Termitidae, which include many species feeding on highly decomposed wood or soil4,5. Although termite genomes encode a few cellulase genes6,7, the ability of termites to digest and metabolize the wood lignocellulose largely depends on their symbiotic gut microbes, including bacteria, archaea, and lignocellulolytic protists present in all termite families but the Termitidae8,9. In addition to these gut microbes, the termitid subfamily Macrotermitinae is associated with the lignocellulolytic fungus Termitomyces they cultivate inside their nest10.

Lignocellulose is a recalcitrant biopolymer composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and a variety of minor components11. Cellulose is a linear chain of glucose, hemicellulose is composed of various sugars linked by networks of bonds, and lignin is a biopolymer composed of cross-linked phenolic compounds12. The degradation of the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin composing lignocellulose requires the action of distinct cocktails of Carbohydrate-Activate Enzymes (CAZymes) attacking various bonds of the polymer. CAZymes are enzymes that biosynthesize, break down, modify, or bind carbohydrates and glycoconjugates13,14. They are divided into six classes based on their properties: Glycosyl Transferases (GTs) catalyze the formation of glycosidic bonds15; Glycoside Hydrolases (GHs), Polysaccharide Lyases (PLs), and Carbohydrate Esterases (CEs) cleave or rearrange glycosidic bonds16,17; enzymes with Auxiliary Activities (AAs) act in conjunction with CAZymes, helping GH, PL, and CE gaining access to carbohydrates, for example by degrading lignin18; and enzymes of the Carbohydrate-Binding Modules class (CBMs) bind to carbohydrates and are associated with catalytic modules19. Therefore, GH, PL, CE, and AA are the classes of CAZymes involved in lignocellulose degradation.

Most CAZymes depolymerizing lignocellulose in the termite gut are produced by gut microbes20–22. Termite gut microbes participate in the hydrolysis of cellulose through the production of various CAZymes, such as endoglucanases (EC 3.2.1.4) (e.g., GH9, GH45, and GH51) and β-glucosidases (EC 3.2.1.21) (e.g., GH1, GH3, and GH5)22,23. They also participate in the degradation of hemicellulose, for example through the production of xylanases (e.g., GH10, GH11, and GH43) and endo-β-1,4-mannanase (e.g., GH8 and GH26), which respectively degrade xylans and glucomannans, two primary constituents of hemicellulose24. Termite gut bacteria are also involved in other metabolic functions, such as nitrogen metabolism, including the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen and the recycling of nitrogen wastes25,26.

Termites acquire their gut microbes through vertical and horizontal transmission events, a process referred to as mixed-mode transmission27. Vertical transmission is the primary mode of acquisition of lignocellulolytic protists and many bacterial lineages abundant in the gut of termites28–32. It is mediated by nestmates exchanging gut fluid through trophallaxis from both ends of the digestive tract along with the microbes it contains, a behavior ensuring the transfer of gut microbes from parent colonies to the offspring colonies33–35. Many bacterial lineages transferred vertically form clades endemic to the termite gut, and their phylogenetic trees generally present a strong cophylogenetic signal with that of their termite host28,29,36. Termite gut bacteria acquired from the environment can readily be recognized in phylogenetic trees by their close evolutionary relationship to bacteria from non-termite environmental samples. These bacteria do not form termite-specific clades and do not present cophylogenetic patterns with termites29,37,38. So far, these cophylogenetic analyses were performed using marker genes, and it remains unclear whether bacterial genes functionally relevant for the processing of glycans and lignocellulose digestion present similar cophylogenetic patterns with termites.

Some CAZyme gene families are ubiquitous in gut metagenomes of all termites and their sister group, the cockroach genus Cryptocercus20. One potential explanation for the origin of bacterial-borne CAZyme families present in the gut of all modern termites is their presence in the genomes of the bacteria that initially colonized the gut of termites and Cryptocercus over the past 150 million years. This hypothesis entails that these CAZyme genes are encoded in the genomes of bacteria vertically transmitted across generations of termites. Therefore, the phylogenetic trees of these CAZyme genes are expected to present a cophylogenetic pattern with termites, similar to that found with bacterial marker genes28. Alternatively, the CAZymes encoded in the genomes of bacteria present in the gut of modern termites may have been acquired more recently by horizontal transfers from bacteria living outside termite guts, in which case no cophylogenetic signals are expected. In this study, we analyzed the gut metagenomes of 195 termites and one Cryptocercus to reconstruct the evolutionary history of termite gut CAZymes. We built the phylogenetic trees of 180 CAZyme families using sequences derived from termites and Cryptocercus and sequences from the GTDB database not associated with termites. We carried out cophylogenetic analyses with the phylogenetic trees of CAZyme sequences forming termite-specific clusters (hereafter: TSCs) and one phylogenetic tree of termites reconstructed using 322 ultraconserved elements (UCEs) by Arora et al.28. Our analyses revealed a strong cophylogenetic signal between termites and many clusters of CAZyme sequences only found in termite gut metagenomes, suggesting that the termite gut microbiota encodes unique CAZymes inherited across generations over the past 150 million years.

Results and discussion

The set of dominant CAZyme families is conserved across termite gut metagenomes

We found a total of 101,941 CAZyme sequences in the gut metagenome assemblies of 195 termites and one individual of Cryptocercus. Our sampling included species from all 13 termite families and 15 of the 18 subfamilies of Termitidae (as defined by ref. 39 (Supplementary Data 1)). We found up to 135 CAZyme families per metagenome. In total, we detected 180 CAZyme families across all gut metagenomes, including 96 GHs, 42 GTs, 11 PLs, 14 CEs, 5 AAs, and 12 CBMs (Supplementary Data 2). 34 CAZymes were found in more than 70% of gut metagenomes, nine of which, including the lignocellulolytic GH3, GH5, GH13, GH43, and GH77, were present in more than 90% of gut metagenomes, confirming that the dominant CAZyme families are ubiquitous across the gut bacterial communities of all termite species, as described in more detail by ref. 20.

Many bacterial CAZymes found in the gut of termites form clusters endemic to termite gut and present a cophylogenetic pattern with termites

We reconstructed the phylogenetic trees of each CAZyme family composed of more than 20 sequences derived from termite gut bacteria using sequences from the gut metagenomes of termites and Cryptocercus and sequences not associated with termites obtained from the GTDB database and identified with BLAST searches. For the 12 CAZyme families divided into subfamilies, we reconstructed one phylogenetic tree for each subfamily. Of the 201 reconstructed CAZyme trees, 116 contained up to 23 termite-specific clusters (TSCs) (Supplementary Data 3, Supplementary Data 4), which we defined as clusters including only sequences associated with termites and found in at least 20 termite and Cryptocercus samples. Some CAZyme trees included a dozen TSCs or more. This was the case of CAZymes ubiquitous amongst termites involved in cellulose degradation, such as GH3 (containing 16 TSCs) and GH5_2 (11 TSCs), and hemicellulose degradation, such as GH5_4 (12 TSCs), GH13 (23 TSC across 11 subfamily trees), and GH43 (17 TSCs across ten subfamily trees).

We identified 420 TSCs comprising an average of 120 sequences, the largest of which was composed of 1080 sequences of the amylomaltase GH77 primarily belonging to Breznakiellaceae (phylum Spirochaetota, previously family Treponemataceae) (Supplementary Data 5, Supplementary Data 6). We carried out cophylogenetic analyses between each TSC and one phylogenetic tree of termites reconstructed using 322 UCE loci. The topology of our termite phylogenetic tree was consistent with previous phylogenetic trees reconstructed with transcriptome and UCE data40,41. We used three cophylogenetic methods: PACo42, the generalized Robison-Foulds metric43, and the method of Nye et al.44. 404 of the 420 TSCs showed a significant cophylogenetic signal with the three methods, 333 of which were highly significant (p < 0.001) for all three methods (Supplementary Data 6). TSCs highly significant (p < 0.001) for all three methods included the 20 TSCs composed of more than 500 sequences, all of which, besides four TSCs composed of GTs, were involved in lignocellulose degradation (two GH3, four GH5, one GH10, one GH13, one GH18, one GH20, two GH57, one GH77, one GH94, one GH130). On average, 42.3% of the CAZyme sequences derived from the contigs composing each metagenome assembly and 44.5% of CAZyme raw reads generated with the Illumina sequencing platform belonged to TSCs (Supplementary Data 2), indicating that they are an important component of the cocktail of bacterial CAZymes found in termite guts. Note that these values represent underestimations of the bacterial CAZymes forming clusters endemic to the termite gut environment given our conservative definition of TSCs, which included sequences of at least 20 samples, and our non-exhaustive sampling effort of the termite diversity. The high relative abundance of bacterial CAZymes composing TSCs is reminiscent of past studies performed on the 16S rRNA gene and bacterial marker genes that demonstrated many key members of the gut microbiota of termites, such as the Breznakiellaceae (phylum Spirochaetota) and the Ruminococcaceae (phylum Bacillota), belong to lineages endemic to termite guts and presenting cophylogenetic patterns with termites28,29,36. In addition, most TSCs were composed of CAZyme families involved in the lignocellulose degradation, such as GH5, GH9, GH13, or GH43. Therefore, many CAZyme genes encoded by the gut microbiota of termites are only found in termite guts, are involved in lignocellulose degradation, and mirror cophylogenetic patterns found for bacterial marker genes.

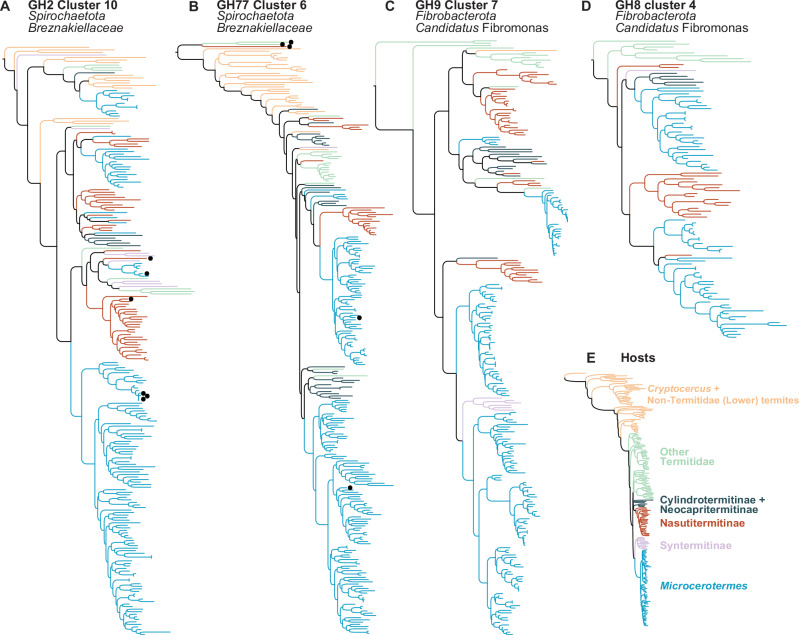

Related termite species harbour termite-clade specific CAZyme clusters

Bacterial contigs from the gut metagenomes of termites and Cryptocercus comprising CAZymes were taxonomically annotated with DIAMOND BLASTx searches45 against the GTDB database Release 20746. Many bacterial CAZyme sequences composing TSCs were involved in lignocellulose digestion and found to belong to taxa dominating the gut microbiota of termites and known to present strong cophylogenetic signals with their termite hosts. This is well illustrated by many TSCs mostly comprised of sequences assigned to Spirochaetota (mostly Breznakiellaceae) and Fibrobacterota (mostly Candidatus Fibromonas) (Table 1, Fig. 1A–D), two bacterial lineages dominating the gut microbiota of many termite species and involved in the digestion and fermentation of wood fibers47. Notably, CAZymes assigned to Breznakiellaceae and Candidatus Fibromonas form large termite clade-specific clusters associated exclusively with Microcerotermes, a genus of termites represented by 58 samples in this study (Fig. 1A–D). Termite clade-specific CAZyme clusters annotated as Breznakiellaceae and Candidatus Fibromonas were also found in the Nasutitermitinae (Fig. 1A–D). These results corroborate those of Arora et al.28, who found termite clade-specific lineages of Breznakiellaceae and Candidatus Fibromonas exclusively associated with Microcerotermes and the Nasutitermitinae. The similar cophylogenetic patterns found across many genes of Breznakiellaceae and Candidatus Fibromonas and involving the same termite hosts highlight the stability of these genomes over tens of millions of years of association with specific termite lineages.

Table 1.

Results of the cophylogenetic analyses performed on the 420 termite-specific bacterial clusters (TSCs)

| Cophylogeny | Fibrobacterota | Spirochaetota | Bacteroidota | Firmicutes A | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PACo p-value < 0.001 | 82 | 55 | 49 | 26 | 142 |

| 0.05 > PACo p-value ≥ 0.001 | 5 | 3 | 27 | 5 | 19 |

| PACo non-significant p-value | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Nye et al. p-value < 0.001 | 85 | 59 | 56 | 25 | 153 |

| 0.05 > Nye et al. p-value ≥ 0.001 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 6 | 8 |

| Nye et al. non-significant p-value | 1 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 3 |

| Robinson–Foulds p-value < 0.001 | 87 | 59 | 58 | 27 | 156 |

| 0.05 > Robinson–Foulds p-value ≥ 0.001 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 4 | 6 |

| Robinson–Foulds non-significant p-value | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 88 | 59 | 78 | 31 | 164 |

P-values were estimated using three cophylogenetic analyses (PACo, generalized Robinson Foulds (RF) metric, and Nye et al.’s method). TSCs were assigned to a bacterial phylum when more than 95% of sequences were assigned to this phylum. The phylum Firmicutes is split into multiple categories in the GTDB database, including Firmicutes_A, one category abundant in termite guts.

Fig. 1. Four of the 420 maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees of termite-specific bacterial clusters (TSCs).

All four trees showed strong cophylogenetic signals with termites. The trees included several termite clade-specific CAZyme clusters only found in Nasutitermitinae and Microcerotermes. Phylogenetic trees of (A) GH2 Cluster 10 composed of 97.4% of Spirochaetota, (B) GH77 Cluster 6 composed of 98.1% of Spirochaetota, (C) GH9 Cluster 7 composed of 100% of Fibrobacterota, and (D) GH8 Cluster 4 composed of 100% of Fibrobacterota. E Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of termites inferred from UCEs. Black dots indicate CAZyme sequences assigned to a different bacterial phylum.

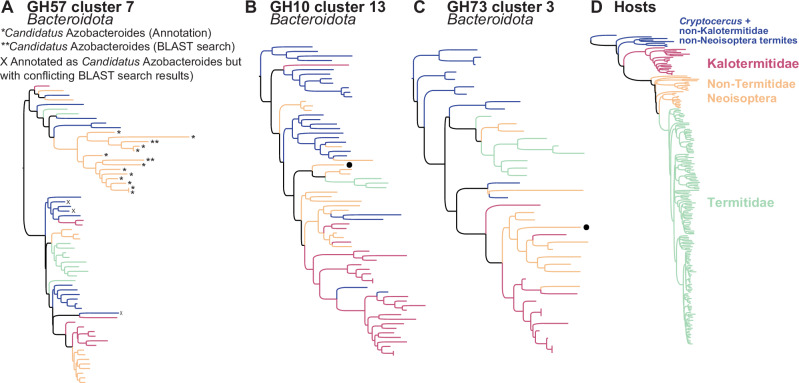

Termite clade-specific CAZyme clusters were also found to be associated with termite lineages sampled less intensively. For example, several TSCs annotated as Bacteroidota comprised subclades of termite clade-specific CAZyme clusters annotated as Candidatus Azobacteroides (Fig. 2A), a bacterial endosymbiont of the cellulolytic protist Pseudotrichonympha48, confirming the exclusive association of these bacteria with all genera of Neoisoptera excluding Reticulitermes and the Termitidae, which do not harbor Pseudotrichonympha49. Several TSCs also included subclades primarily associated with the Kalotermitidae (Fig. 2B, C), suggesting that termite-clade-specific bacterial CAZyme clusters are present across the termite tree of life. We expect future studies, relying on a comprehensive sampling of termite lineages not sampled intensively in this study, to reveal the existence of additional termite-clade-specific bacterial CAZyme clusters.

Fig. 2. Three of the 420 maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees of termite-specific bacterial clusters (TSCs).

All three trees showed strong cophylogenetic signals with termites and included termite clade-specific CAZyme clusters associated with Kalotermitidae or non-Termitidae Neoisoptera. Phylogenetic trees of (A) GH57 Cluster 7 composed of Bacteroidota only and including the genus Candidatus Azobacteroides, (B) GH10 Cluster 13 composed of 98.5% of Bacteroidota, and (C) GH73 Cluster 3 composed of 97.6% of Bacteroidota. D Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of termites inferred from UCEs. *CAZyme sequences annotated as Candidatus Azobacteroides; **CAZyme sequences assigned to Candidatus Azobacteroides with BLAST search against the GenBank database; X CAZyme sequences originally annotated as Candidatus Azobacteroides but with conflicting BLAST search against the GenBank database. Black dots indicate CAZyme sequences assigned to a different bacterial phylum.

Some termite-specific clusters are present across termites and Cryptocercus, suggesting their history of association is ~150 million years old

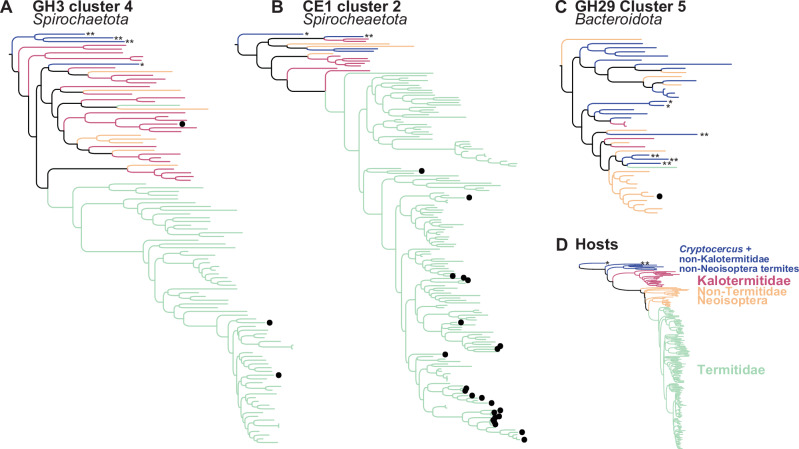

Many bacterial CAZyme sequences forming TSCs were found in the gut metagenomes of diverse termites and Cryptocercus. For example, 131 of 420 TSCs comprised at least one CAZyme sequence associated with the gut metagenomes of Cryptocercus or Mastotermes, which were represented by only one sample each in this study, and 229 TSCs comprised CAZyme sequences from the gut metagenomes of both Neoisoptera and non-Neoisoptera termites (Supplementary Data 6; Fig. 3A–C). The presence of bacterial CAZyme sequences associated with phylogenetically distant termite species in many TSCs suggests they have an ancient history of association with termites and Cryptocercus, some dating back to the origin of these insects ~150 million years ago. There is evidence that termites acquired some of the symbiotic bacterial lineages populating their guts some 150 million years ago28, roughly around the time they acquired their gut lignocellulolytic protists9. While horizontal transfers of gut bacterial CAZymes among unrelated termite species could theoretically explain their distribution across termites in some cases, the strong cophylogenetic signals between most TSCs and termites and the existence of numerous termite clade-specific CAZyme clusters within TSC trees suggest coevolution with vertical transfers is the dominant factor. Termite colony members frequently exchange gut fluid and the microbes it contains through a process called trophallaxis, which provides a stable route of vertical transfer from parent to offspring colonies33–35. This specific mode of inheritance, coupled with the oxygen sensitivity and the specialization of termite gut bacteria to the gut environment, possibly makes termite gut bacteria unable to migrate outside their host, explaining the strong cophylogenetic patterns with their hosts. Following this scenario, many CAZymes forming TSCs were acquired together with the bacteria encoding them in their genomes and have remained exclusively associated with termite guts since then.

Fig. 3. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees of three of the 131 termite-specific bacterial clusters (TSCs) containing at least one sequence of Cryptocercus and/or Mastotermes.

The three trees showed strong cophylogenetic signals with termites. Phylogenetic trees of (A) GH3 Cluster 4 composed of 97.3% of Spirochaetota, (B) CE1 Cluster 2 composed of 86.2% of Spirochaetota, and (C) GH29 Cluster 5 composed of 97.7% of Bacteroidota. D Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of termites inferred from UCEs. *Cryptocercus kyebangensis; **Mastotermes darwiniensis. Black dots indicate CAZyme sequences assigned to a different bacterial phylum.

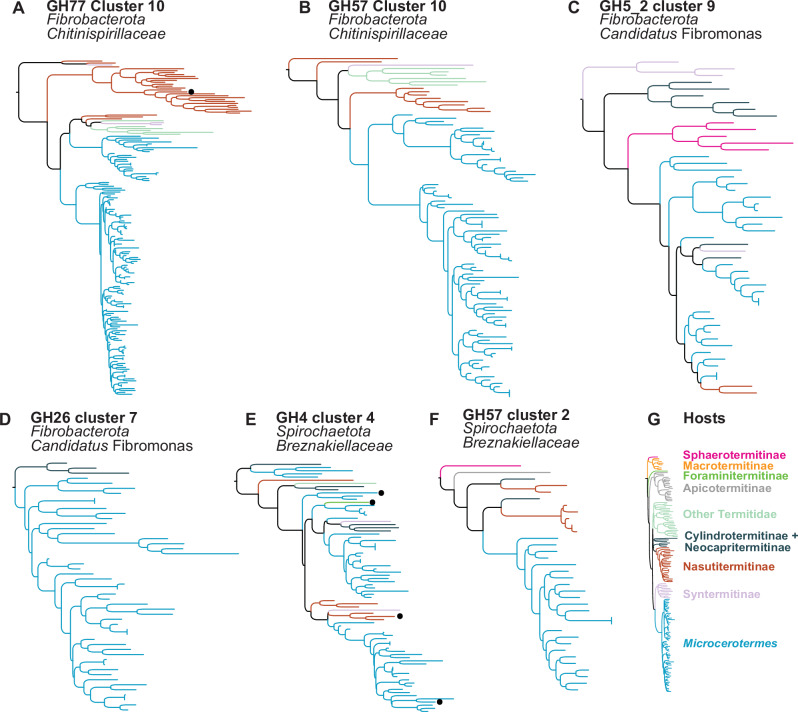

Some termite-specific clusters are unique to Termitidae, suggesting their history of association is 30 to 60 million years old

While our results indicate many bacterial CAZymes forming TSCs have been inherited from early termite ancestors, some, such as the 175 exclusives to Termitidae, may have been acquired more recently by the ancestors of Termitidae, some 30–60 million years ago. Two mechanisms of acquisition of these CAZymes are the acquisition of new gut bacterial symbionts together with the CAZyme repertoire encoded in their genomes and horizontal transfers from bacteria not associated with termite guts. We found evidence of the former mechanism in 26 TSCs restricted to Termitidae and including upward of 90% of CAZymes assigned to Chitinispirillaceae (phylum Fibrobacterota) (Fig. 4A, B), a family of bacteria recorded in no other termites than Termitidae20. Similarly, 23 TSCs restricted to Termitidae were comprised of upward of 90% of CAZymes annotated as Candidatus Fibromonas (phylum Fibrobacterota) (Fig. 4C, D), a bacterial genus abundant in the gut of many Termitidae and rarely found in other termites28, suggesting these CAZymes were encoded in the genome of Candidatus Fibromonas as it transitioned to become a termite gut symbiont. In contrast, five TSCs restricted to Termitidae are suggestive of the latter mechanism, as they included more than 90% of CAZymes annotated as Spirochaetota, most of which from the Breznakiellaceae (Fig. 4E, F), a bacterial family present across the gut of most termites20. Future studies are needed to determine whether the Breznakiellaceae populating the gut of the ancestor of Termitidae acquired these CAZymes by horizontal transfer from bacteria not associated with termite guts.

Fig. 4. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees of six of the 175 termite-specific bacterial clusters (TSCs) strictly associated with Termitidae.

The six trees showed strong cophylogenetic signals with termites. Phylogenetic trees of (A) GH77 Cluster 10 composed of 99.4% of Fibrobacterota, primarily of the family Chitinispirillaceae, (B) GH57 Cluster 10 composed only of Fibrobacterota, primarily of the family Chitinispirillaceae, (C) GH5_2 Cluster 9 composed only of Fibrobacterota of the genus Candidatus Fibromonas, (D) GH26 Cluster 7 composed only of Fibrobacterota, primarily of the genus Candidatus Fibromonas, (E) GH4 Cluster 4 composed of 94.9% of Spirochaetota, and (F) GH57 Cluster 2 only composed of Spirochaetota. G Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of Termitidae inferred from UCEs. Black dots indicate CAZyme sequences assigned to a different bacterial phylum.

Conclusion

Our results show that a large fraction of the CAZymes encoded by the termite gut microbiota are only found in termites and have been associated with this niche at geological timescales. Some were likely encoded in the genomes of the first gut symbiotic bacteria of the common ancestor of termites and Cryptocercus and passed down to modern termites by means of vertical transfers. This includes many CAZymes involved in lignocellulose degradation, indicating that the cocktail of CAZymes allowing termites to digest wood is largely encoded in the genomes of vertically inherited bacteria, with limited contribution from bacteria living outside their guts. The uniqueness of termite gut bacterial CAZymes raises the possibility that the exceptional efficiency of termites at digesting wood is partly linked to the intrinsic characteristics of their CAZymes.

Materials and methods

Data collection and metagenome analyses

We used the gut metagenome assemblies of 195 termites and one Cryptocercus previously published by refs. 20,28 (Supplementary Data 1). All contigs composing these assemblies and longer than 1000 base pairs were taxonomically annotated using DIAMOND BLASTx searches45 with e-value 1e-24 against the GTDB database Release 9550. The open reading frames coding for CAZymes were identified among these metagenome contigs using Hidden Markov model searches against the dbCAN2 database51. Fragments of CAZyme sequences shorter than 50% of the expected CAZyme length were not considered. We only considered hits with e-value lower than e-30 and coverage upward of 0.35. For CAZymes composed of several modules, we separated the domains corresponding to specific CAZyme families. CAZyme sequences from termite gut metagenomes were also searched against the GTDB database Release 20746 using Nucleotide-Nucleotide BLAST v2.10.0+52 with default settings to obtain sequences not associated with termites. We retained a single copy of every sequence obtained from the GTDB database and not associated with termites using seqkit tool v2.0.053. These CAZymes sequences not associated with termites were analyzed together with CAZyme sequences derived from termite gut metagenomes.

Reconstruction of CAZyme phylogenetic trees

We reconstructed one phylogenetic tree for each CAZyme family comprising more than 20 sequences derived from termite gut bacteria. For the large families divided into subfamilies, we reconstructed one phylogenetic tree for each CAZyme subfamily composed of more than 20 sequences derived from termite gut bacteria. 12 families were divided into subfamilies: GH43 into 25 subfamilies; GH13 into 21 subfamilies; GH5 into 20 subfamilies; GH30 into seven subfamilies; PL8 and PL12 into three subfamilies; and AA3, PL1, PL6, PL9, PL10, and PL11 into two subfamilies. In total, we reconstructed 201 phylogenetic trees. We used sequences derived from termite gut metagenomes and sequences from the GTDB database not associated with termites. Nucleotide sequences were translated into amino acid sequences using the codon Supplementary Table 11 (bacterial and archaeal code) with Geneious prime v2022.2.0. Protein sequences of each CAZyme gene family were aligned using MAFFT v7.490 with the parameters “--auto setting”, which are recommended for aligning many sequences54,55. Protein alignments were converted into nucleotide alignments using pal2nal v14.1-356 with the codon table 11 (bacterial and archaeal code). Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree reconstructions were carried out on nucleotide alignments using Fasttree v2.1.11-257 with the settings “-gtr -gama”. The phylogenetic trees of every CAZyme family were rooted using 20 sequences of related CAZyme families included in the analyses as outgroups and chosen based on information available on www.cazy.org14. The outgroup sequences were non-termite sequences obtained from the CAZyme database v11 available at bcb.unl.edu/dbCAN2/download/Databases/v11/. We verified that outgroup sequences cluster together in the phylogenetic analyses, allowing us to identify the root of the tree unambiguously.

Termite phylogenetic trees

We used the termite phylogenetic trees reconstructed by ref. 28 with UCEs. The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed with 322 of the 50,616 termite-specific UCE loci41. An average of 186.8 UCE loci were found per termite gut metagenome, thence the completeness of the matrix was ~57%. These UCE loci matched, at least partly, singly-annotated exons from the draft genome of Zootermopsis nevadensis58. The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using IQ-TREE v1.6.12 with a GTR+G+I model of nucleotide substitution and 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates (UFB) to assess branch supports59,60, as described in ref. 28. The phylogenetic tree, reconstructed with 43% of missing data, was congruent with previous phylogenetic trees built using UCE and transcriptome data, which contained smaller proportions of missing data40,41.

Identification of termite-specific CAZyme clusters

We searched the phylogenetic trees of all CAZyme families for clusters including sequences exclusively derived from the gut metagenomes of termites and Cryptocercus. We only considered clusters containing sequences from more than 20 termite and Cryptocercus samples. We refer to these clusters as termite-specific clusters (hereafter: TSCs). Clusters containing sequences from fewer than 20 samples were not considered in downstream analyses. To estimate the relative contribution of TSCs to termite wood digestion, we calculated the relative abundance of each TSC by mapping the trimmed sequencing reads onto the CAZyme sequences. The procedure was performed separately on sequences from TSCs and sequences that did not belong to any TSC. Reads were aligned using BWA-MEM v0.7.1061 and the resulting alignments were sorted (“sort”) and fixed (“fixmate”) with SAMtools v1.962. The number of reads mapping to each set of CAZymes was extracted using the SAMtools “flagstat” command. We used these values to estimate the proportion of CAZymes belonging to TSCs for each gut metagenome analyzed in this study.

Statistics and reproducibility

We carried out cophylogenetic analyses between termites and all TSCs using three different approaches. The first approach was the Procrustean Approach to Cophylogeny implemented in the R package PACo42. For this approach, termite and TSC trees were converted into distance matrices using the cophenetic() function of the vegan R package63. We ran the software using the backtrack method of randomization to conserve the overall degree of interactions between termite and TSC trees64. The second approach was the generalized Robinson Foulds (RF) metric43 implemented in the ClusteringInfoDistance() function of the TreeDist R package43. The third approach was the method of Nye et al.44 implemented in the NyeSimilarity() function of the TreeDist R package43. For this approach, the termite and TSC trees were matched to find an optimal 1-to-1 map between branches. For the last two methods, implemented in the TreeDist R package, each termite tip was split into x tips of zero branch length, where x is the number of CAZyme sequences associated with the metagenome corresponding to that termite tip65,66. Congruence between the termite and TSC trees was determined using 1000 random permutations.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (project No. 20-20548S) and project IGA No. 20233113 from the Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences of the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague. Computational resources were provided by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology.

Author contributions

A.B. and T.Bou. conceptualized the experiments and approach. T.Ber., J.A., and S.H. performed the bioinformatics analyses. T.Bou. wrote the paper. T.Ber., J.A., J.R.A., A.B., G.T., J.S., and S.H. read, commented, and accepted the final version of this manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Joao Paulo L. Franco-Cairo and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Sabina La Rosa and David Favero.

Data availability

Raw sequence data used in this study were previously published and are available in two MGRAST projects (https://www.mg-rast.org/mgmain.html?mgpage=project&project=mgp101108 and https://www.mg-rast.org/mgmain.html?mgpage=metazen2&project=mgp84199) (see Table S1 for individual IDs). The UCE sequences were previously published and are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: 10.5061/dryad.tmpg4f53w.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Tereza Beránková, Jigyasa Arora.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-07146-w.

References

- 1.Engel, M. S., Barden, P., Riccio, M. L. & Grimaldi, D. A. Morphologically specialized termite castes and advanced sociality in the Early Cretaceous. Curr. Biol.26, 522–530 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo, N. et al. Evidence from multiple gene sequences indicates that termites evolved from wood-feeding cockroaches. Curr. Biol.10, 801–804 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inward, D. J. G., Vogler, A. P. & Eggleton, P. A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of termites (Isoptera) illuminates key aspects of their evolutionary biology. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.44, 953–967 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan, S. E., Eggleton, P. & Bignell, D. E. Gut content analysis and a new feeding group classification of termites. Ecol. Entomol.26, 356–366 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourguignon, T. et al. Feeding ecology and phylogenetic structure of a complex neotropical termite assemblage, revealed by nitrogen stable isotope ratios. Ecol. Entomol.36, 261–269 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe, H., Noda, H., Tokuda, G. & Lo, N. A cellulase gene of termite origin. Nature394, 330–331 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tokuda, G. et al. Major alteration of the expression site of endogenous cellulases in members of an apical termite lineage. Mol. Ecol.13, 3219–3228 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brune, A. Symbiotic digestion of lignocellulose in termite guts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.12, 168–180 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chouvenc, T., Šobotník, J., Engel, M. S. & Bourguignon, T. Termite evolution: mutualistic associations, key innovations, and the rise of Termitidae. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.78, 2749–2769 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouland-Lefèvre, C. Symbiosis with Fungi. in Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbioses, Ecology (eds. Abe, T., Bignell, D.E., Higashi, M.) 289–306 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2000). 10.1007/978-94-017-3223-9_14.

- 11.Lynd, L. R., Weimer, P. J., van Zyl, W. H. & Pretorius, I. S. Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.66, 506–77 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Béguin, P. & Aubert, J.-P. The biological degradation of cellulose. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.13, 25–58 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantarel, B. L. et al. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res.37, D233–D238 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drula, E. et al. The carbohydrate-active enzyme database: functions and literature. Nucleic Acids Res.50, D571–D577 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coutinho, P. M., Deleury, E., Davies, G. J. & Henrissat, B. An evolving hierarchical family classification for glycosyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol.328, 307–317 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henrissat, B. & Davies, G. Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.7, 637–644 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lombard, V. et al. A hierarchical classification of polysaccharide lyases for glycogenomics. Biochem. J.432, 437–444 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levasseur, A., Drula, E., Lombard, V., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. Expansion of the enzymatic repertoire of the CAZy database to integrate auxiliary redox enzymes. Biotechnol. Biofuels6, 41 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boraston, A. B., Bolam, D. N., Gilbert, H. J. & Davies, G. J. Carbohydrate-binding modules: fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem. J.382, 769–781 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arora, J. et al. The functional evolution of termite gut microbiota. Microbiome10, 78 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marynowska, M. et al. Compositional and functional characterisation of biomass-degrading microbial communities in guts of plant fibre- and soil-feeding higher termites. Microbiome8, 96 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warnecke, F. et al. Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature450, 560–565 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe, H. & Tokuda, G. Cellulolytic systems in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol.55, 609–632 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albersheim, P., Darvill, A., Roberts, K., Sederoff, R. & Staehelin, A. Plant Cell Walls (Garland Science, 2010). 10.1201/9780203833476.

- 25.Brune, A. & Ohkuma, M. Role of the termite gut microbiota in symbiotic digestion. In Biology of Termites: a Modern Synthesis (eds. Bignell, D. E., Roisin, Y., Lo, N.) 439–475 (Springer Netherlands, 2010). 10.1007/978-90-481-3977-4_16.

- 26.Katsumata, K. S., Jin, Z., Hori, K. & Iiyama, K. Structural changes in lignin of tropical woods during digestion by termite, Cryptotermes brevis. J. Wood Sci.53, 419–426 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebert, D. The epidemiology and evolution of symbionts with mixed-mode transmission. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst.44, 623–643 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arora, J. et al. Evidence of cospeciation between termites and their gut bacteria on a geological time scale. Proc. Biol. Sci.290, 20230619 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourguignon, T. et al. Rampant host switching shaped the termite gut microbiome. Curr. Biol.28, 649–654 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noda, S. et al. Endosymbiotic Bacteroidales bacteria of the flagellated protist Pseudotrichonympha grassii in the gut of the termite Coptotermes formosanus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.71, 8811–8817 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohkuma, M., Noda, S. & Kudo, T. Phylogenetic diversity of nitrogen fixation genes in the symbiotic microbial community in the gut of diverse termites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.65, 4926–4934 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohkuma, M. & Brune, A. Diversity, structure, and evolution of the termite gut microbial community. in Biology of Termites: a Modern Synthesis (eds. Bignell, D.E. Roisin, Y., Lo, N.) 413–438 (Springer Netherlands, 2010). 10.1007/978-90-481-3977-4_15.

- 33.Michaud, C. et al. Efficient but occasionally imperfect vertical transmission of gut mutualistic protists in a wood-feeding termite. Mol. Ecol.29, 308–324 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nalepa, C. A., Bignell, D. E. & Bandi, C. Detritivory, coprophagy, and the evolution of digestive mutualisms in Dictyoptera. Insectes Soc.48, 194–201 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinotte, V. M., Renelies-Hamilton, J., Andreu-Sánchez, S., Vasseur-Cognet, M. & Poulsen, M. Selective enrichment of founding reproductive microbiomes allows extensive vertical transmission in a fungus-farming termite. Proc. Biol. Sci.290, 20231559 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietrich, C., Köhler, T. & Brune, A. The cockroach origin of the termite gut microbiota: patterns in bacterial community structure reflect major evolutionary events. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.80, 2261–2269 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chouvenc, T., Elliott, M. L., Šobotník, J., Efstathion, C. A. & Su, N.-Y. The Termite Fecal Nest: A Framework for the Opportunistic Acquisition of Beneficial Soil Streptomyces (Actinomycetales: Streptomycetaceae). Environ. Entomol.47, 1431–1439 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visser, A. A., Nobre, T., Currie, C. R., Aanen, D. K. & Poulsen, M. Exploring the potential for actinobacteria as defensive symbionts in fungus-growing termites. Microb. Ecol.63, 975–985 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hellemans, S. et al. Genomic data provide insights into the classification of extant termites. Nat. Commun.15, 6724 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bucek, A. et al. Evolution of termite symbiosis informed by transcriptome-based phylogenies. Curr. Biol.29, 3728–3734.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hellemans, S. et al. Using ultraconserved elements to reconstruct the termite tree of life. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.173, 107520 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balbuena, J. A., Míguez-Lozano, R. & Blasco-Costa, I. PACo: A novel Procrustes Application to Cophylogenetic analysis. PLoS One8, e61048 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith, M. R. Information theoretic generalized Robinson-Foulds metrics for comparing phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics36, 5007–5013 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nye, T. M. W., Liò, P. & Gilks, W. R. A novel algorithm and web-based tool for comparing two alternative phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics22, 117–119 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods12, 59–60 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parks, D. H. et al. GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res.50, D785–D794 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tokuda, G. et al. Fiber-associated spirochetes are major agents of hemicellulose degradation in the hindgut of wood-feeding higher termites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA115, E11996–E12004 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hongoh, Y. et al. Genome of an endosymbiont coupling N2 fixation to cellulolysis within protist cells in termite gut. Science322, 1108–1109 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kitade, O. & Matsumoto, T. Characteristics of the symbiotic flagellate composition within the termite family Rhinotermitidae (Isoptera). Symbiosis25, 271–278 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parks, D. H. et al. A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nat. Biotechnol.38, 1079–1086 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, H. et al. dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res.46, W95–W101 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol.215, 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shen, W., Le, S., Li, Y. & Hu, F. SeqKit: A Cross-pPlatform and Ultrafast Toolkit for FASTA/Q File Manipulation. PLoS One11, e0163962 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K.-I. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res.30, 3059–3066 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol.30, 772–780 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suyama, M., Torrents, D. & Bork, P. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res.34, W609–W612 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol.26, 1641–1650 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terrapon, N. et al. Molecular traces of alternative social organization in a termite genome. Nat. Commun.5, 3636 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoang, D. T., Chernomor, O., von Haeseler, A., Minh, B. Q. & Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol.35, 518–522 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol.32, 268–274 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F. G., Kindt, R. & Legendre, R. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-10, edn. (2014). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

- 64.Hutchinson, M. C., Fernando Cagua, E., Balbuena, J. A., Stouffer, D. B. & Poisot, T. paco: implementing Procrustean Approach to Cophylogeny in R. Methods Ecol. Evol.8, 932–940 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Perez-Lamarque, B. & Morlon, H. Characterizing symbiont inheritance during host-microbiota evolution: Application to the great apes gut microbiota. Mol. Ecol. Resour.19, 1659–1671 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Satler, J. D. et al. Inferring processes of coevolutionary diversification in a community of Panamanian strangler figs and associated pollinating wasps. Evolution73, 2295–2311 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequence data used in this study were previously published and are available in two MGRAST projects (https://www.mg-rast.org/mgmain.html?mgpage=project&project=mgp101108 and https://www.mg-rast.org/mgmain.html?mgpage=metazen2&project=mgp84199) (see Table S1 for individual IDs). The UCE sequences were previously published and are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: 10.5061/dryad.tmpg4f53w.