Abstract

Ribosomal DNA (rDNA) repeats harbor ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes and intergenic spacers (IGS). RNA polymerase (Pol) I transcribes rRNA genes yielding rRNA components of ribosomes. IGS-associated Pol II prevents Pol I from excessively synthesizing IGS non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) that can disrupt nucleoli and rRNA production. Here, compartment-enriched proximity-dependent biotin identification (compBioID) revealed the TATA-less-promoter-binding TBPL1 and transcription-regulatory PAF1 with nucleolar Pol II. TBPL1 localizes to TCT motifs, driving Pol II and Pol I and maintaining its baseline ncRNA levels. PAF1 promotes Pol II elongation, preventing unscheduled R-loops that hyper-restrain IGS Pol I-associated ncRNAs. PAF1 or TBPL1 deficiency disrupts nucleolar organization and rRNA biogenesis. In PAF1-deficient cells, repressing unscheduled IGS R-loops rescues nucleolar organization and rRNA production. Depleting IGS Pol I-dependent ncRNAs is sufficient to compromise nucleoli. We present the nucleolar interactome of Pol II and show that its regulation by TBPL1 and PAF1 ensures IGS Pol I ncRNAs maintaining nucleolar structure and function.

Subject terms: Long non-coding RNAs, RNA quality control, Nucleolus, Gene expression, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing

By revealing the nucleolar interactome of RNA Pol II, the authors show the regulation of transcription by TBPL1 and PAF1 within ribosomal DNA’s intergenic spacers ensures baseline ncRNA levels critical to nucleolar structure and function.

Introduction

Central to ribosome biogenesis is ribosomal DNA (rDNA)1–3. In humans, ~350 rDNA units are arranged on five chromosomes with ~70 tandem repeats per chromosome. Each rDNA unit harbors a ~ 13.3 kb ribosomal RNA (rRNA)-coding gene and a larger, ~29.7 kb, intergenic spacer (IGS). rDNA is separated from the rest of the genome in a nuclear compartment called the nucleolus1,4,5. The latter is organized through the phase separation of its resident proteins into three sub-compartments—the fibrillar center (FC), dense fibrillar component (DFC), and outermost granular component (GC)1,4–7. At the FC-DFC boundary, RNA polymerase I (Pol I) transcribes rRNA genes into a precursor rRNA (pre-rRNA) that co-transcriptionally undergoes processing and assembly into pre-ribosomes as it moves through the DFC and GC8–12. This eventually yields the mature 18S, 5.8S, and 28S rRNAs onto which ribosomal proteins are fully assembled to drive protein synthesis and cell growth8,9.

We previously reported that Pol II and Pol I cohabit the IGS, where they compete to control nucleolar structure and ribosome biogenesis13. Operating from an IGS promoter, Pol II generates antisense intergenic non-coding RNAs (asincRNAs). These asincRNAs can reinvade the DNA duplex behind Pol II, hybridizing with template DNA and yielding R-loop structures composed of an RNA-DNA hybrid and a single strand of DNA13. Pol II and its R-loops create a shield that limits Pol I recruitment to the IGS. Inhibiting Pol II hyper-induces Pol I function at the IGS13. Similar results were obtained upon repressing the Pol II-dependent R-loop shield at the IGS using a locus-associated R-loop repression system (LasR) employing a chimeric protein harboring dCas9 and the RNA-DNA hybrid repressor RNase H1 (RNaseH1-EGFP-dCas9 (RED))13,14. The unleashed Pol I synthesizes excessive levels of sense intergenic non-coding RNAs (sincRNAs) that severely disrupt nucleolar organization and ribosome biogenesis. The induction of sincRNAs preceded nucleolar disorganization, and nucleolar structure and function were rescued in IGS Pol II-deficient cells upon repressing Pol I-dependent sincRNAs using antisense oligonucleotides13. Thus, IGS Pol II is a key driver of ribosome biogenesis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) showed that Pol II localizes throughout the rDNA repeats peaking near the IGS 28-30 kb region13. ChIP-sequencing (ChIP-seq) analyzes also revealed that this IGS region is especially enriched in Pol II together with the intergenic promoter marks H3K27Ac, H3K9Ac, and H3K4me3. Together with strand-specific RNA analyzes incorporating Pol II inhibitors, these data indicated that Pol II mostly initiates transcription from the IGS’s 28-30 kb region in the antisense orientation13. However, it remains unclear how IGS Pol II transcription and its impact on IGS Pol I and rRNA biogenesis are regulated. Also, whether the baseline, constitutive function of IGS Pol I is biologically relevant is unknown.

Here, we reveal two nucleolar Pol II regulators, the TATA box-binding protein-like 1 (TBPL1) and Pol II-associated factor-1 (PAF1). Proteomic analyzes and validations revealed these factors cohabit the IGS with Pol II. TBPL1 deficiency restricted Pol II and Pol I recruitment and function at the IGS, reducing the levels of IGS ncRNAs. PAF1 depletion interfered with Pol II progression through the IGS, inducing unscheduled R-loops at a specific IGS region and restraining IGS Pol I function. Thus, the loss of TBPL1 or PAF1 converge on limiting IGS Pol I function. Notably, cells deficient in TBPL1 or PAF1 showed an altered relative organization of nucleolar constituents and rRNA biogenesis. Repression of the unscheduled IGS R-loops in PAF1-deficient cells restored IGS ncRNA expression, rescuing nucleolar organization and rRNA production. Also, directly repressing the baseline levels of IGS Pol I-dependent sincRNAs compromised nucleolar organization and rRNA biogenesis. Thus, cells have evolved mechanisms to fine-tune IGS Pol I function, the excess or deficiency of which compromises nucleolar structure and function via distinct processes.

Results

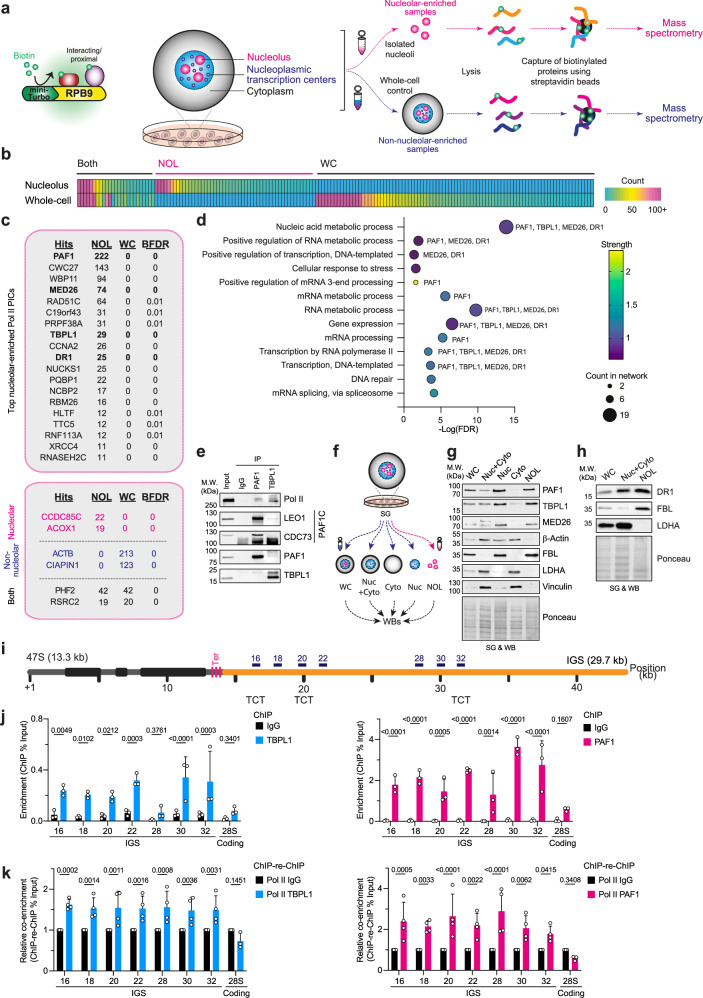

TBPL1 and PAF1 co-habit the IGS with nucleolar Pol II

To uncover the nucleolar interactome of Pol II, we tagged its RPB9/POLR2I subunit with FLAG-miniTurboID. We used the tagged protein as “bait” in a compartment-enriched proximity-dependent biotin identification (compBioID) analysis where a sucrose gradient-based nucleolar isolation was performed before using mass spectrometry to identify proteins proximal to the bait (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2)15–17. This analysis also employed a standard whole-cell proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) analysis as control16. We selected RPB9 as bait due to its proximity to the interface between the Pol II complex and DNA18,19. We detected 115 high-confidence RPB9 proximity interactors (PICs) in the non-fractionated samples, and 77 PICs in the nucleolar-enriched samples (Fig. 1b). Notably, of these 77 hits, 52 were detected exclusively in nucleolar-enriched samples (Fig. 1b). Known nucleolar proteins were detected in the nucleolar-enriched samples20, and known non-nucleolar proteins were detected only in the non-nucleolar-enriched samples (Fig. 1c(bottom)). STRING gene ontology (GO) analysis of the nucleolar-exclusive interactors identified 19 proteins linked to RNA Pol II-dependent transcription and gene expression (Fig. 1, c(top) and d). Amongst this group, the polymerase-associated factor 1 (PAF1), TATA-binding protein-like 1 (TBPL1), mediator complex subunit 26 (MED26), and down-regulator of transcription 1 (DR1) were all linked to 5/13 enriched processes and globally linked to 10/13 processes identified (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1. Localization of TBPL1 and PAF1 with nucleolar Pol II at the rDNA IGS.

a Schematic of compBioID used to identify nucleolar Pol II interactome. Expression of miniTurbo- RPB9 promotes biotinylation of proximal proteins. This is followed by sucrose gradient-based (SG) enrichment of nucleoli and identification of biotinylated factors using mass spectrometry. Non-nucleolar enriched whole-cell samples served as control. b Heatmap showing peptide counts for biotinylated proteins detected in nucleolar-enriched (NOL), whole-cell (WC), or both samples. c Top 19 biotinylated proteins detected only in NOL samples and categorized under nucleic acid regulation using STRING analysis. List of internal controls detected known to be nucleolar, non-nucleolar, or both. Peptide counts are shown with the Bayesian False discovery rate (BFDR). d Biological processes gene ontology analysis of the 19 proteins from panel (c) with the number of proteins in the molecular network (bubble size), and the strength of the enrichment (color). e Immunoblots showing Pol II co-immunoprecipitates with PAF1 or TBPL1. f Schematic of modified SG-based cellular fractionations to compare nucleoplasmic+cytoplasmic (Nuc+Cyto), nucleoplasmic (Nuc), Cytoplasmic (Cyto), and NOL fractionations to non-fractionated WC samples by Western blotting (WB). g, h Immunoblots assessing the presence of PAF1, FBL, TBPL1, DR1, and MED26 in WC, Nuc+Cyto, Nuc, Cyto, and NOL samples. Nucleolar-enriched FBL served as positive control and non-nucleolar proteins β-actin, vinculin, and LDHA served as negative controls. i Schematic of a mammalian rDNA unit containing the 47S pre-rRNA-encoding 13.3 kb rRNA gene and the 29.7 kb intergenic spacer (IGS, orange) with the positioning of key primer pairs used in this study. Also shown are IGS sites harboring TCT motifs. j Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) showing the localization of TBPL1 (left) and PAF1 (right) at the IGS. 28S rRNA-coding site served as negative control. k ChIP-re-ChIP showing the co-localization of TBPL1 (left) or PAF1 (right) with Pol II at the IGS. Enrichments are presented relative to the Pol II+immunoglobulinG (IgG) mock ChIP-re-ChIP control. 28S rRNA-coding site served as negative control. a–k Experiments were performed using Flp-In 293 T-RExTM (b–d) or HEK293T cells (e–k); blots (e, g, h) are representative of three biologically independent experiments; data in (j, k) are shown as mean ± s.d., were from large experimental sets sharing IgG control, were analyzed using two-way ANOVA, and n = 3 (j) or n = 4 (k) biologically independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

TBPL1 (a.k.a. TLP, TRF2, or TLF) is a TBP homolog that preferentially recognizes TCT motifs (CTCTTTCC; a.k.a. polypyrimidine initiator elements)21,22. Recognition of TCT-type motifs by TBPL1 promotes Pol II transcription initiation from TATA-less promoters21. Once Pol II initiates transcription, the polymerase enters a stage of promoter-proximal pausing. The release of Pol II from this pausing is dependent on a balance between factors that promote pausing, such as negative elongation factor (NELF) and DRB-sensitivity inducing factor (DSIF), and those that promote Pol II release, such as positive elongation factor b (P-TEFb)23. PAF1, which is the major subunit of the PAF1 complex (PAF1C), is also an important regulator of Pol II pause release23–25. PAF1C consists of PAF1, LEO1, CDC73, SKIC8, and CTR924.

MED26 is a subunit of the mediator complex, which is recruited to promoters through direct interactions with regulatory proteins and scaffolds the assembly of a functional pre-initiation complex with Pol II and its general transcription factors26–28. DR1 (DownRegulator of transcription 1; a.k.a. Negative Cofactor 2β or NC2β), together with NC2α, forms a heterodimeric complex that binds to TBP, preventing its interaction with TFIIA or TFIIB. DR1 also binds DNA and is a component of the chromatin remodeling ATAC complex29,30.

Consistent with the identification of TBPL1 and PAF1 in the compBioID analysis, these endogenous proteins were detected via immunoblotting following the streptavidin-mediated pulldown of biotinylated proteins only from cells induced to express Flag-mTurbo-RPB9 (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In addition, immunoprecipitating endogenous PAF1 or TBPL1 pulled down endogenous Pol II (Fig. 1e). The co-immunoprecipitation of LEO1 and CDC73 with PAF1 served as positive control. To validate the enrichment of TBPL1, PAF1, MED26, and DR1 in mammalian nucleoli, we performed sucrose gradient-based nucleolar isolation coupled to immunoblotting (Fig. 1f). Indeed, TBPL1, PAF1, MED26, and DR1 were all present in the nucleolar fraction along with the nucleolar resident protein fibrillarin (FBL) (Fig. 1g, h). The natural depletion of the nucleoplasmic or cytoplasmic proteins β-actin, vinculin, and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) confirmed the efficiency of nucleolar isolation (Fig. 1g, h), consistent with the microscopy-based observation of isolated nucleoli in the nucleolar-enriched samples (Supplementary Fig. 1a). In addition, chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled to qPCR (ChIP) revealed the localization of TBPL1 and PAF1 across the IGS (Fig. 1i, j), and this was comparable to other genetic loci known to be occupied by these factors (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The 28S rDNA coding region served as negative control, revealing the preferred localization of these proteins at the IGS (Fig. 1j). However, we could not detect MED26 or DR1 at rDNA (Supplementary Fig. 3c), even though we detected these factors at known positive control genomic sites (Supplementary Fig. 3d). To gain a better understanding of the relationship of Pol II with chromatin states, TBPL1, or PAF1 at the IGS, we performed sequential ChIP coupled to qPCR (ChIP-re-ChIP)13. In this assay, two consecutive protein pull-downs are performed before co-immunoprecipitating DNA. First, we assessed whether Pol II is associated with active or inactive rDNA units by first pulling down H3K27Ac or H3K9me2, followed by a Pol II pulldown13. We observed the preferred co-localization of Pol II with H3K27Ac compared to H3K9me2 at the IGS, suggesting Pol II is preferentially at active rDNA units, consistent with the expected higher localization of Pol II to more accessible chromatin (Supplementary Fig. 3e). More importantly, Pol II co-localized with TBPL1 or PAF1 across the IGS but not the rRNA-coding 28S region (Fig. 1k). Analysis of the IGS DNA sequence identified several TCT motifs (Fig. 1i, Supplementary Fig. 3f), further supporting the presence of TBPL1 at the IGS region21,22. Also, consistent with the ChIP-re-ChIP results showing the co-localization of Pol II with TBPL1 or PAF1 at the IGS (Fig. 1k), proximity ligation assays (PLA) gauging Pol II proximity to TBPL1 or PAF1 revealed nucleolar signals (Supplementary Fig. 3g). Taken together, our findings so far reveal that PAF1 and TBPL1 associate with nucleolar Pol II at the IGS within active rDNA units.

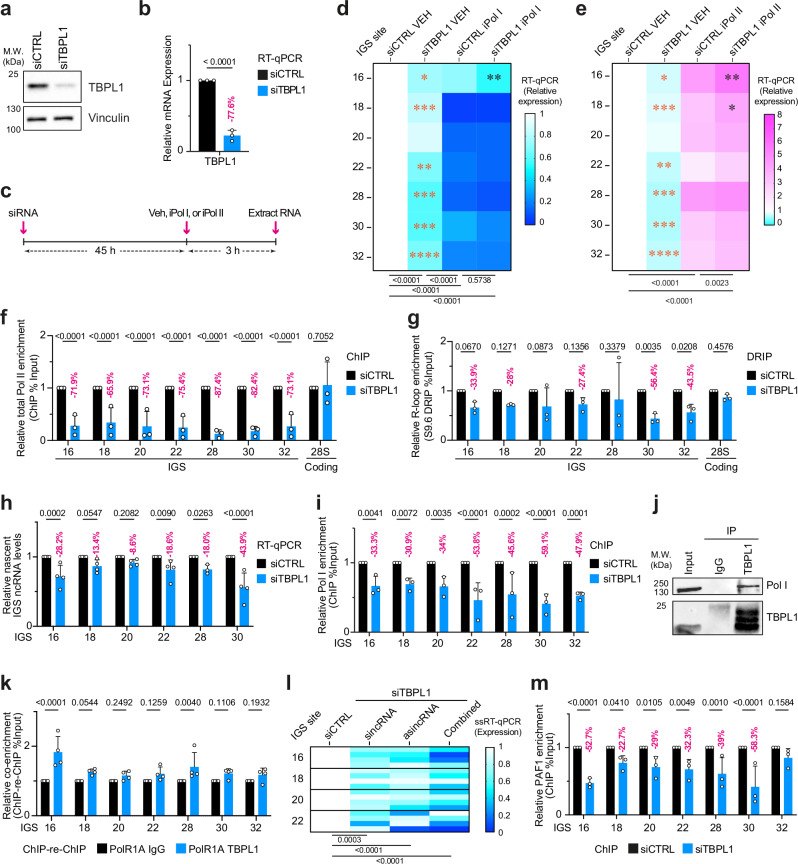

Dependence of intergenic Pol II and Pol I on TBPL1

To investigate the function of PAF1 and TBPL1 at the IGS, we first studied TBPL1 since it has previously been reported to regulate Pol II transcription initiation from TCT-containing promoters21,22. Therefore, we asked whether TBPL1 impacts the levels of ncRNA across the IGS. Free sincRNAs are much more abundant throughout the IGS than the R-loop formation-prone asincRNAs, so most of the detectable IGS ncRNAs are Pol I-dependent transcripts13. Thus, to better distinguish the relationship of TBPL1 with the RNA polymerases at the IGS, we evaluated the impact of TBPL1 depletion on IGS ncRNAs in the presence or absence of Pol I or Pol II inhibition (iPol I or iPol II) (Fig. 2a–c). To do so, cells were treated for three hours with DMSO (Veh.), low-dose actinomycin D (LAD) for iPol I, or flavopiridol (FP) for iPol II (Fig. 2c). TBPL1-depleted cells showed a significant decrease in steady-state IGS ncRNA levels, specifically at the IGS 16, 18, and 22-32 regions (Fig. 2d), partly mimicking Pol I inhibition13. The average change in the levels of ncRNAs at all IGS sites tested following TBPL1 knockdown was a reduction of 28.7% (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Also, iPol I was dominant over TBPL1 knockdown, almost entirely repressing ncRNA levels from IGS18 to IGS32 (Fig. 2d), as expected13. However, at IGS16, where iPol I did not entirely repress ncRNA levels, iPol I and TBPL1 knockdown additively lowered ncRNA levels, suggesting that these interventions decrease IGS ncRNA levels by non-identical processes (Fig. 2d). In addition, iPol II did induce ncRNA levels across the IGS as we previously showed (Fig. 2e)13. Notably, iPol II was fully dominant over TBPL1 depletion, except for the IGS 16 and 18 regions where TBPL1 knockdown slightly but significantly increased ncRNA levels further (Fig. 2e). Overall, these findings indicate that TBPL1 promotes IGS ncRNA expression primarily in unperturbed cells, where both Pol I and Pol II are functional at the IGS. Pol I inhibition significantly lowers ncRNA levels, largely muting the repressive effect of TBPL1 depletion. Similarly, in the absence of Pol II function, the drastically increased function of Pol I at the IGS greatly desensitizes the region to TBPL1 depletion.

Fig. 2. TBPL1 mediates Pol II and Pol I transcription at the rDNA IGS.

a, b Validation of TBPL1 knockdown via immunoblotting (a) and RT-qPCR (b). c Schematic of the experimental setup employing a 3-hour inhibition of Pol I or Pol II (iPol I or iPol II) following siRNA-mediated knockdown of TBPL1 (siTBPL1). d, e Heatmaps showing the effect of TBPL1 knockdown on IGS ncRNA levels in cells treated with vehicle (VEH), iPol I, or iPol II. f ChIP analysis of total Pol II localization across the IGS and the 28S rRNA-coding negative control site. g DRIP analysis of R-loop levels at the IGS and the 28S negative control site. h RT-qPCR analysis of 5-EU-labeled nascent IGS ncRNAs. i ChIP analysis of Pol I localization across the IGS. j Immunoblotting showing Pol I pulldown with immunoprecipitated TBPL1. k ChIP-re-ChIP assessing the co-localization of TBPL1 and Pol I at the IGS. l Heatmap presenting the strand-specific analysis of IGS ncRNA using ssRT-qPCR following TBPL1 knockdown. (m) ChIP analysis of PAF1 localization at the IGS. a–m Experiments were performed using HEK293T cells; quantitative data are shown as mean±s.d. from n = 3 except for (h, k, l) where n = 4 biologically independent experiments; blots are representative of three biologically independent experiments (a, j); data in (f, i, m) were from large experimental sets sharing the IgG control; data were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed t-test (b), two-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD (f–k, m) or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (l), and for (d, e) shown is two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (below heatmaps), multiple unpaired two-tailed t-tests comparing VEH-treated samples (orange asterisks) and two-way ANOVA for iPol I- or iPol II-treated samples (black asterisks). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next sought to investigate the impact of TBPL1 on Pol I and Pol II at the IGS in unperturbed cells. TBPL1-depleted cells exhibited a significant decrease in total Pol II localization across the IGS (Fig. 2f). This result was akin to the impact of TBPL1 depletion on Pol II localization at the ribosomal protein gene RPLP1A (Supplementary Fig. 4b), which is transcribed via TBPL1/TCT-dependent Pol II function in Drosophila31. This decrease in Pol II localization following TBPL1 depletion was not observed at TCT-independent sites, namely the 28S rRNA-coding region and β-ACTIN gene promoter (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 4b), and occurred without changing global Pol II level (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Reduced Pol II enrichment at the IGS was accompanied by a significant decrease in the levels of IGS R-loops as measured using S9.6 antibody-based DNA-RNA immunoprecipitation (DRIP; Fig. 2g; Supplementary Fig. 4d). DRIP signals were sensitive to RNaseH1 treatment in vitro, highlighting the specificity of R-loop detection using S9.6 (Supplementary Fig. 4d). These changes in R-loops were also observed using the His-GFP-tagged catalytically dead RNase H1 (GFP-dRNH1; a.k.a. RNaseH1(DN)), which depicted similar R-loop levels at the IGS (Supplementary Fig. 4d–f). Hence, TBPL1 is required to enrich Pol II at the IGS efficiently.

Given that Pol II generates R-loops at the IGS to shield the region from excessive Pol I recruitment, we next assessed transcriptional activity at the IGS by measuring the incorporation of 5-ethynyl uridine (5-EU) in nascent transcripts13. TBPL1 knockdown decreased the levels of nascent IGS ncRNA (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Fig. 4g) and reduced Pol I occupancy at the IGS (Fig. 2i). This occurred without changes to global Pol I levels (Supplementary Fig. 4h). These findings point to a role for TBPL1 in increasing the localization of Pol I and Pol II at the IGS.

Notably, co-immunoprecipitation revealed endogenous interaction between TBPL1 and Pol I (Fig. 2j). Furthermore, ChIP-re-ChIP indicated that TBPL1 and Pol I are co-localized especially at the IGS16 region (Fig. 2k), which harbors TCT-type sequences on the DNA sense strand (Fig. 1i, Supplementary Fig. 4i). This prompted us to study the impact of depleting TBPL1 on sense and antisense IGS transcripts. We observed reductions in sincRNA and asincRNA levels (Fig. 2l), suggesting that TBPL1 is required for the efficient function of Pol II and Pol I at the IGS. Analysis of the sincRNA/asincRNA ratio showed that TBPL1 depletion, despite decreasing overall IGS ncRNA levels (Fig. 2l), did not significantly tilt the balance between the Pol I-dependent sincRNAs and Pol II-dependent asincRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 4j). On the other hand, and as expected, control iPol I and iPol II decreased and increased the sincRNA/asincRNA ratio, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4j). Together these findings are consistent with TBPL1 equally promoting Pol I-dependent sincRNAs and Pol II-dependent asincRNAs. Consistent with this notion and with the operation of TBPL1 upstream of the Pol II-associated PAF1, the depletion of TBPL1 also lowered the localization of PAF1 across the IGS (Fig. 2m), indicating that TBPL1 is required for the efficient recruitment of Pol I, Pol II, and Pol II-associated factor PAF1.

Considering the interaction of TBPL1 with Pol I at the IGS, and the known regulation of ribosomal protein genes by TBPL1, we suspected that TBPL1 might be a master regulator of diverse transactional processes impacting ribosome biogenesis. So, we next asked whether TBPL1 also co-habits the rRNA gene promoter with Pol I. Indeed, ChIP-re-ChIP analysis revealed the co-localization of TBPL1 and Pol I at the rRNA gene promoter (Supplementary Fig. 4k). Furthermore, TBPL1-depleted cells showed a partial yet significant reduction in Pol I occupancy at the rRNA gene promoter, and this without significant changes at the 28S rRNA-coding region (Supplementary Fig. 4l). Overall, our findings suggest that TBPL1 promotes the localization and function of Pol I and Pol II at numerous genomic loci promoting ribosome biogenesis. Specifically, TBPL1 promotes Pol I loading at the rRNA gene promoter, Pol I and Pol II localization at the IGS, and Pol II recruitment to ribosomal protein genes. So, we propose that TBPL1 is a master regulator of ribosome manufacture.

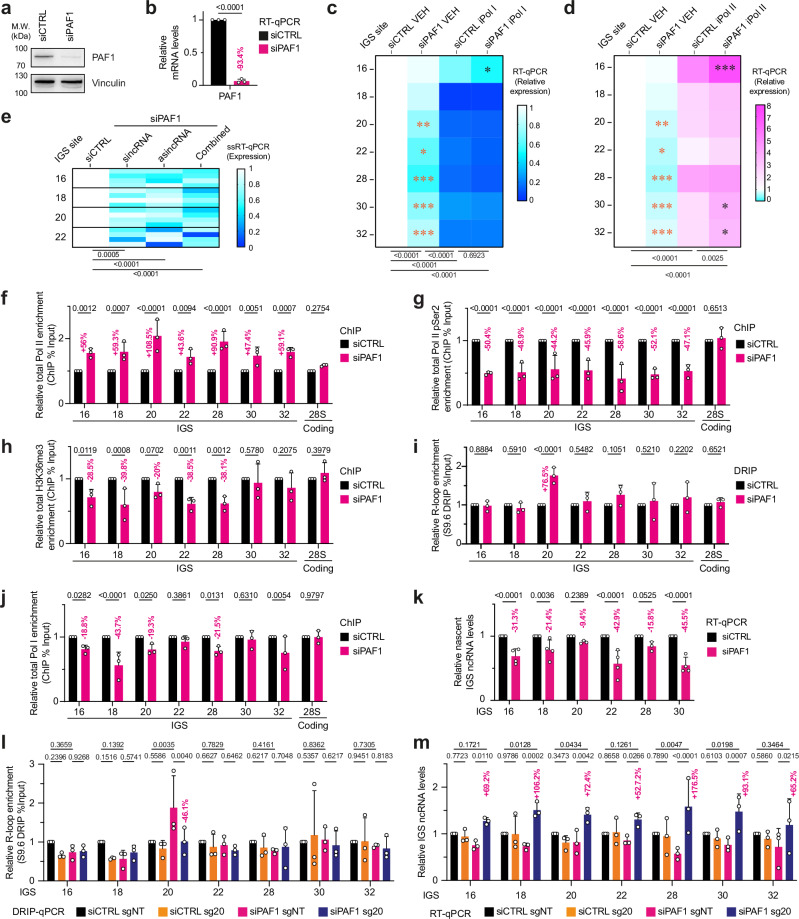

IGS Pol II transcription elongation via PAF1

Next, we aimed to further study the impact of PAF1 on the IGS. First, we set out to assess the effect of PAF1 depletion on IGS ncRNA expression in the presence or absence of iPol I or iPol II. We used cells following a 48 h siRNA-mediated knockdown of PAF1 (Fig. 3a, b). PAF1 knockdown alone did not significantly alter ncRNA levels within the IGS 16-18 region, from which IGS Pol I initiates ncRNA synthesis (Fig. 3c). However, PAF1 knockdown partly mimicked iPol I, decreasing IGS ncRNA levels in the IGS 20-30 region (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 5a). Pol I inhibition was dominant over PAF1 depletion, almost entirely repressing ncRNA levels across the IGS except for IGS16, where combining PAF1 knockdown with iPol I further decreased ncRNA levels (Fig. 3c). On another front, iPol II induced IGS ncRNA levels as expected (Fig. 3d). Notably, PAF1 knockdown failed to repress IGS ncRNA levels in the presence of iPol II despite the presence of readily detectable levels of ncRNAs (Fig. 3d). In fact, knocking down PAF1 slightly yet significantly increased IGS ncRNA levels at IGS 16 and 30. Together, these findings indicate that PAF1 maintains ncRNA levels in unperturbed cells. Also, PAF1 knockdown may moderately increase the ncRNA-repressing effect of iPol I and partly boost the ncRNA-inducing effect of iPol II. Strand-specific analysis of ncRNAs at the IGS further revealed that PAF1 knockdown significantly decreased sincRNA and asincRNA levels (Fig. 3e), similar to TBPL1 disruption (Fig. 2l). Moreover, knockdown of TBPL1 and PAF1 were epistatic in terms of decreasing overall IGS ncRNA levels (Supplementary Fig. 5b). However, unlike TBPL1 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 4j), PAF1 knockdown significantly increased the sincRNA/asincRNA ratio (supplementary Fig. 5c). Overall, our observations suggest that both TBPL1 and PAF1 support the function of Pol I and Pol II at the IGS, albeit PAF1 may primarily promote Pol II function. The data also indicate that TBPL1 is critical to Pol I and Pol II recruitment at the IGS (Fig. 2f, h–i, l), consistent with TBPL1’s known ability to initiate transcription from TCT motifs (Fig. 1i; Supplementary Figs. 3f, 4i)21. These observations prompted us to further assess whether TBPL1 and PAF1 perform identical functions or distinct roles that ultimately converge on the promotion of IGS transcription.

Fig. 3. IGS-associated PAF1 mediates Pol II transcription elongation.

a, b Validation of PAF1 knockdown via immunoblotting (a) and RT-qPCR (b). c, d Heatmaps showing the effect of PAF1 knockdown on IGS ncRNA levels in cells treated with vehicle (VEH), iPol I, or iPol II. e Heatmap presenting the strand-specific RT-qPCR (ssRT-qPCR) analysis of IGS ncRNAs following PAF1 knockdown. f–h ChIP analysis assessing the impact of PAF1 knockdown on the localization of total Pol II (f), Pol II pSer2 (g), and H3K36me3 (h) across the IGS and the 28S rRNA-coding control. i–k Impact of PAF1 knockdown on R-loops detected using DRIP (i), Pol I in ChIP (j), and nascent ncRNA levels in RT-qPCR (k) at the IGS. The 28S rRNA-coding site served as control i, j. l, m Use of the LasR system employing the RED fusion protein together with sg20 represses R-loops at the IGS20 site in DRIP (l) and increases IGS ncRNA levels across the IGS in RT-qPCR (m). a–k Experiments were performed using HEK293T cells except for (k, m) where HEK293 TRexTM were used; blots (a) are representative of three biologically independent experiments; quantitative data are shown as means (heat maps) or mean±s.d. (graphs); n = 3 except for (e, k) where n = 4 biologically independent experiments; data were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests (b), two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (e) or with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test (f–m), and for (c, d) shown is two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (below heatmaps), multiple unpaired two-tailed t-tests comparing VEH-treated samples (orange asterisks), and two-way ANOVA for iPol I- or iPol II-treated samples (black asterisks). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Therefore, we set out to gain further insight into the role of PAF1 at the IGS. PAF1 commonly regulates transcription elongation within protein-coding genes by associating with Pol II and regulating histone marks, such as histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation (H3K36me3)32. At the IGS, PAF1 knockdown led to the accumulation of total Pol II and depletion of Pol II pSer2, which represents elongating Pol II (Fig. 3f, g). These changes were observed in the absence of any change in Pol II protein level (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Decreases in H3K36me3 accompanied the changes in Pol II occupancy (Fig. 3h). These findings are consistent with PAF1 regulating Pol II transcription elongation at the IGS, a role that we did not observe for TBPL1.

Pol II stalling is linked to the formation of unscheduled R-loops33–35. Antisense R-loops created by an RNA polymerase can strongly obstruct RNA polymerases operating in the sense orientation at sites of convergent transcription13. Consistent with this notion, DRIP assays using the S9.6 antibody revealed the accumulation of R-loops specifically at IGS20 following PAF1 knockdown (Fig. 3i, Supplementary Fig. 5e), which was the site with the largest total Pol II accumulation following PAF1 knockdown (Fig. 3f). S9.6 signals were reduced using in vitro RNaseH1 treatment, confirming S9.6 signal specificity (Supplementary Fig. 5e). In addition, this increase in nucleolar R-loops at IGS20 was confirmed using GFP-dRNH1 (Supplementary Fig. 5f). Furthermore, knockdown of PAF1 but not TBPL1 increased the accumulation of nucleolar R-loops as measured using a less sensitive microscopy-based analysis employing the GFP-tagged R-loop/RNA-DNA hybrid-binding domain of RNaseH1 (HB-GFP; Supplementary Fig. 5g)36. Of note, TBPL1 knockdown prevented the accumulation of HB-GFP-marked nucleolar R-loop signals in PAF1-deficient cells (Supplementary Fig. 5g), in agreement with TBPL1 acting upstream of PAF1 in the regulation of Pol II-dependent transcription. Notably, the increase in R-loops at IGS20 was accompanied by losses in Pol I occupancy, especially at the IGS 16-20 region (Fig. 3j) despite stable Pol I protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 5h). Consistent with the disruption of Pol I and Pol II at the IGS of PAF1-depleted cells, they displayed decreased ncRNA synthesis throughout the IGS (Fig. 3k). These findings are consistent with a model where TBPL1 ensures transcription initiation by Pol I and Pol II at the IGS. Therefore, TBPL1 operates upstream of the Pol II transcription elongation-promoting PAF1 at the IGS. This function of PAF1 prevents the formation of unscheduled R-loops at IGS20. The accumulation of such unscheduled R-loops in PAF1-deficient cells may also limit Pol I function at the IGS. Taken together, our results so far suggest that PAF1 and TBPL1 operate via non-identical molecular processes that ultimately converge on a common mechanism promoting the expression of IGS ncRNAs.

To repress the unscheduled R-loops at IGS20 without repressing IGS ncRNA expression, we employed the LasR system13,14. We used short guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting IGS20 (sg20) to selectively enrich the inducibly expressed RED (RNaseH1-EGFP-dCas9) fusion protein at the affected IGS site13,14,37,38. As controls, we used non-targeting sgRNA (sgNT) and the fusion protein dRED (dRNaseH1-EGFP-dCas9), which harbors a catalytically dead version of the RNaseH1 enzyme13,14. ChIP indicated the successful targeting of RED or dRED to IGS20 when using sg20 compared to sgNT (Supplementary Fig. 5i, j). DRIP analysis indicated the repression of the unscheduled R-loops at IGS20 in PAF1-depleted cells when targeting RED using sg20 (Fig. 3l). Resolving the unscheduled R-loops increased ncRNA levels throughout the IGS (Fig. 3m), and this reflected increases in the levels of both the sincRNAs and asincRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 5k). Of note, the rescued production of ncRNAs resulted in their levels being slightly higher in the rescued PAF1-deficient cells than in the control cells at some but not all IGS sites tested (Fig. 3m). This could be related to the use of an artificial rescue system, which may not reflect endogenous processes. For instance, the restoration of Pol II elongation in the absence of natural transcriptional pause and release owing to continued PAF1 deficiency could result in slightly excessive asincRNA synthesis and may also partly limit the ability of the faster Pol II transcription to effectively limit Pol I-dependent sincRNA. More importantly, unlike RED, dRED did not lower R-loop levels or induce IGS ncRNA levels even when combined with sg20 (Supplementary Fig. 5l, m). Our findings suggest that the Pol II elongation defect-related accumulation of unscheduled R-loops at IGS20 in PAF1-depleted cells also hinders baseline Pol I function at the IGS.

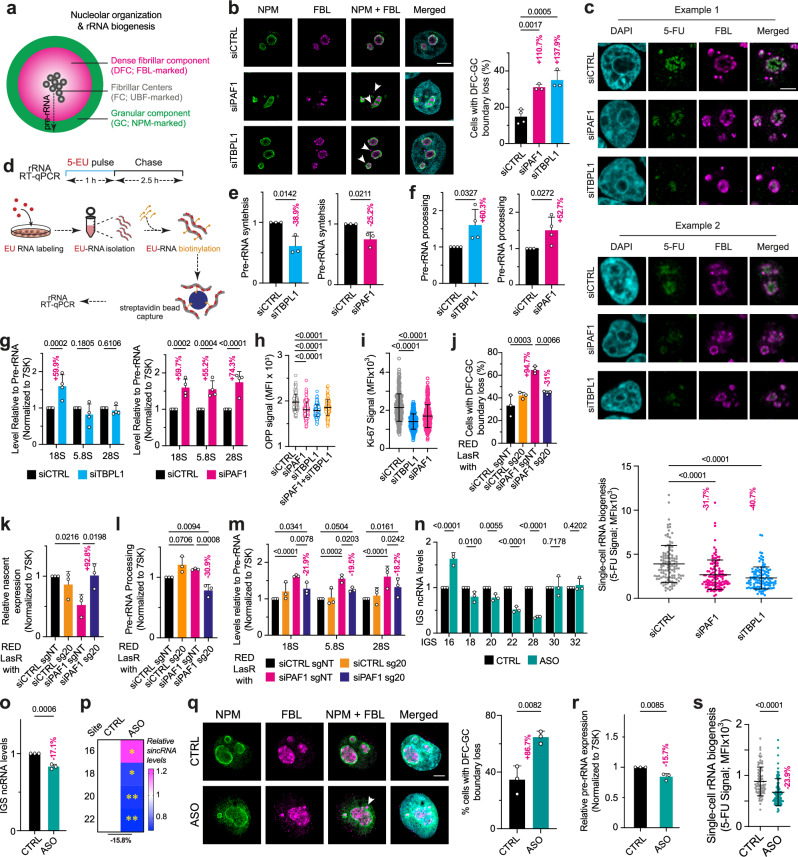

Optimization of nucleoli via PAF1, TBPL1, and baseline sincRNAs

Inhibition of IGS Pol II excessively induces Pol I-dependent sincRNAs13. This increase in sincRNAs likely occurs in the absence of detectable rRNA gene-associated Pol I readthrough transcription into the IGS within our experimental conditions as suggested by long-read RNA sequencing of IGS transcripts (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b) and by PCR-based assessment of potential readthrough transcripts (Supplementary Fig. 6c), and consistent with prior works where such readthrough transcripts were non-detectable under diverse conditions13,39,40. However, it is possible that at least some sincRNAs may implicate Pol I readthrough transcription under different settings or that the absence of detectable rRNA-gene-associated Pol I readthrough reflects the elevated activity of nucleolar rRNA-containing surveillance and processing machineries. Following Pol II inhibition, the accumulating Pol I-dependent sincRNAs drastically disrupt nucleolar architecture and rRNA biogenesis13. This is consistent with a beneficial role for baseline asincRNAs and a deleterious role for accumulating sincRNAs. However, whether baseline sincRNA levels serve a biological function is unknown. Our findings suggest that TBPL1 and PAF1 operate through different mechanisms to ultimately promote the recruitment and function of Pol I and Pol II at the IGS. Thus, we hypothesized that baseline IGS transcription by Pol I and Pol II maintains nucleolar organization and its role in rRNA biogenesis. Pre-rRNA synthesis and early processing occurs in the nucleolar FCs and at the FCs-DFC boundary followed by the transcript’s migration through the DFC and GC for continued sequential processing (Fig. 4a)6,41. Immunofluorescence and imaging analyzes of the DFC-marking protein FBL and GC-indicating protein nucleophosmin (NPM) showed that the knockdown of PAF1 or TBPL1 partly changed the positioning of the DFC relative to the GC (Fig. 4b). Particularly, PAF1 or TBPL1 deficiency increased the levels of FBL-marked DFC bodies that protruded into the NPM-marked GC or were even located beyond it into the nucleoplasm. These altered nucleolar phenotypes suggest that PAF1 and TBPL1 maintain the proper layering of nucleolar sub-compartments housing pre-rRNA synthesis and processing. This is distinct from the complete nucleolar fragmentation observed following the direct inhibition of Pol II or its R-loops using different approaches13.

Fig. 4. Nucleolar organization and function via PAF1, TBPL1, and sincRNAs.

a Schematic of nucleolar organization and related rRNA biogenesis. b Knockdown of PAF1 or TBPL1 alters the organization of FBL relative to NPM. c Representative images and quantifications from single-cell analyzes showing the impact of PAF1 or TBPL1 knockdown on rRNA biogenesis as assessed using 5-FU-labeled rRNA at the FBL-marked nucleolus. d–f Schematic (d) of the 5-EU-labeling and biotinylation-based pulse-chase RT-qPCR assay used to measure rRNA synthesis (e) and processing (f). g RT-qPCR analysis of the processing of the indicated mature rRNA molecules following the knockdown of PAF1 or TBPL1. h O-propargyl puromycin (OPP) pulse-labeling signal shows the impact of knocking down PAF1, TBPL1, or both on nascent protein synthesis. i Impact of TBPL1 or PAF1 knockdown on Ki-67 signal. j–m Combining RED together with sg20 restores the FBL-NPM boundary (j), restores rRNA synthesis (k), and decreases rRNA processing (l, m). n, o Impact of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting sincRNAs within the IGS18-28 region on IGS ncRNA levels at the indicated single IGS sites (n) or all IGS sites (o) tested. p Impact of ASOs on sincRNA levels as assessed by ssRT-qPCR. q–s Impact of the ASOs on the nucleolar FBL-NPM boundary (q), EU-labeled pre-RNA synthesis in RT-qPCR (r), and single-cell rRNA biogenesis assessed by 5-FU-labeled nucleolar rRNAs (s). b–s Experiments were performed using HEK293T cells except for (j–m) where 293 T-RExTM were used; data shown as mean±s.d.; n = 3 (b, d–e, j–r) or n = 4 (f, g) biologically independent replicates, and n = 116 (c), 150 (h), 276 (i), or 83 (s) cells per condition from three biologically independent replicates; statistical analysis conducted using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s (b, h, i) or Tukey’s (c, j–l) multiple comparisons test, unpaired two-tailed t-tests (e, f, o–s), two-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test (g, m, n, q) Images are representative of three (b, c, q) independent experiments; Scale bar, 5 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Therefore, we set out to assess the potential role of PAF1 and TBPL1 in regulating rRNA biogenesis using 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), the incorporation of which into newly synthesized rRNAs can be quantified using single-cell microscopy. Notably, rRNA biogenesis was significantly disrupted in cells with TBPL1 or PAF1 knockdown (Fig. 4c). To assess the impact of TBPL1 and PAF1 on pre-rRNA synthesis and processing specifically, we used 5-EU-labeled RNA pulse-chase assays coupled to RT-qPCR (Fig. 4d). Indeed, PAF1 or TBPL1 knockdown decreased pre-rRNA synthesis (Fig. 4e), consistent with the single-cell rRNA biogenesis results (Fig. 4c). We then assessed rRNA processing by quantifying the levels of 5-EU-marked 18S, 5.8S, or 28S rRNA relative to pre-rRNA levels following a 2.5-hour chase with unlabeled media (Fig. 4d). Notably, despite decreasing rRNA synthesis and rRNA biogenesis overall, the knockdown of PAF1 or TBPL1 increased pre-rRNA processing as assessed by 5-EU pulse-chase coupled to RT-qPCR (Fig. 4f). Of note, detailed analysis of the processing phenotype in PAF1-deficient cells indicated that processing related to all mature rRNAs was increased (Fig. 4g, right). This observation suggests an evenly accelerated processing rate of the different rRNA processing intermediates. In contrast, in TBPL1-deficient cells, the increased rate of rRNA processing was specific to 18S rRNA and was therefore not observed for the 28S or 5.8S rRNAs (Fig. 4g, left). These results suggest an asymmetrically increased rRNA processing in TBPL1-deficient cells. Consistent with the impact of TBPL1 or PAF1 on rRNA biogenesis, their depletion decreased nascent protein synthesis as measured using modified puromycin pulse-labeling (Fig. 4h) and lowered cell growth as assessed using Ki-67 staining (Fig. 4i). Overall, consistent with our molecular studies (Figs. 2 and 3), these findings indicate that TBPL1 and PAF1 promote rRNA biogenesis through overlapping but non-identical processes.

To examine whether the altered localization of FBL relative to NPM and rRNA biogenesis in PAF1-depleted cells is dependent on the unscheduled IGS20 R-loops observed in these cells (Fig. 3i, l, m), we enriched the RED or control dRED fusion protein at IGS20 (Supplementary Fig. 5i, j). In PAF1-deficient cells, resolving the unscheduled R-loops at IGS20 (Fig. 3l), which moderately increases IGS ncRNA levels (Fig. 3m), restored the localization of FBL-marked DFC relative to NPM-marked GC (Fig. 4j), rescuing rRNA synthesis (Fig. 4k), and restraining processing (Fig. 4l, m). These findings suggest that low or baseline levels of ncRNAs may be critical for optimizing nucleolar organization and function.

Considering that Pol I-dependent sincRNAs constitute the bulk of baseline IGS ncRNAs13, we asked whether the direct repression of sincRNAs alters nucleolar organization and rRNA biogenesis, similar to the depletion of PAF1 or TBPL1. Therefore, we depleted the baseline levels of the Pol I-dependent sincRNAs in otherwise unperturbed cells using a pool of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting sincRNAs synthesized from the IGS18-28 region (Fig. 4n). Notably, targeting sincRNAs in this region increased the levels of ncRNAs at IGS16, likely as part of a compensatory selection for cells with higher sincRNA transcription by Pol I initiating from IGS16 (Fig. 4n). Nonetheless, the ASO approach decreased the levels of IGS ncRNAs tested by an average of 17.1% (Fig. 4o). Concordantly, strand-specific analysis confirmed that the sincRNA-targeting ASOs decreased relative sincRNA levels by an average of 15.8% across all sites tested (Fig. 4p). Notably, ASO-mediated knockdown of baseline sincRNAs phenocopied the loss of PAF1 or TBPL1, altering the localization of FBL relative to NPM (Fig. 4q). This altered localization was matched by a decreased rRNA biogenesis (Fig. 4r,s). These results suggest that a low level of Pol I-dependent sincRNAs is critical for the relative organization of nucleolar constituents and nucleolar function in live cells. So, we further assessed the potential impact of sincRNA levels on molecular self-assembly in a reductionist system in vitro. Amyloid-converting motifs (ACMs) drive the condensation of various proteins into liquid-like bodies in the nucleolus, and this in a sincRNA-dependent manner13,39,42–44. Consistent with this notion, we observed that sincRNA16 drives ACM condensation in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 6d, e), as expected13,39,42–44. However, excessively increasing the sincRNA concentration decreased ACM condensation in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 6d, e). Taken together, our findings suggest that an optimal baseline level of Pol I-dependent sincRNAs is critical for nucleolar structure and function.

Discussion

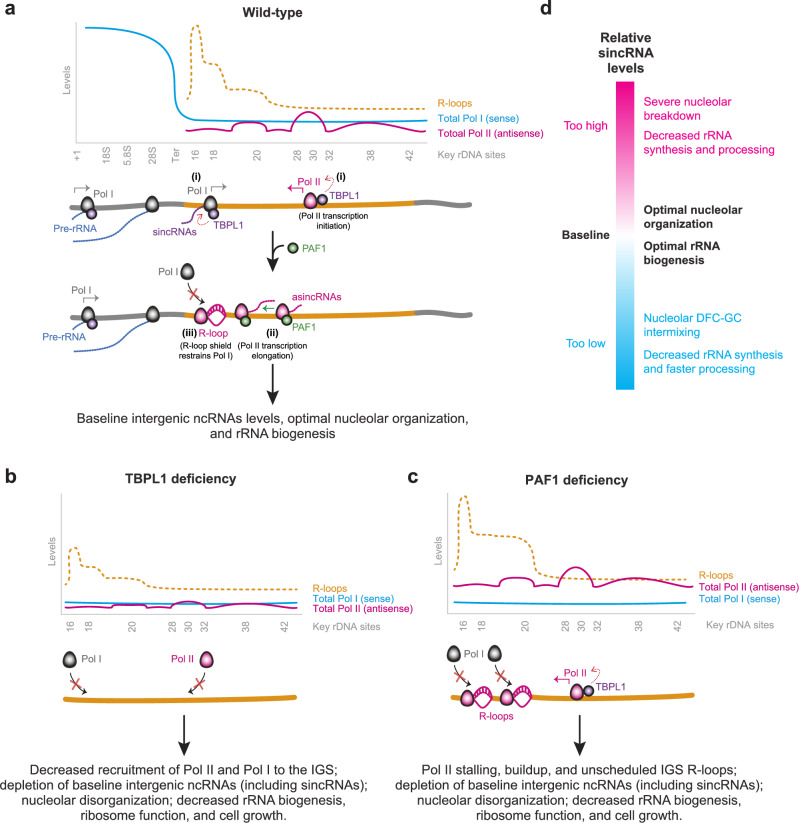

The nucleolus harbors the rDNA repeats encoding the rRNAs critical to universal protein synthesis4,45. At rDNA repeats, in addition to Pol I-dependent synthesis of pre-rRNA from rRNA genes, Pol I and Pol II transcribe ncRNAs from across the rDNA IGS. Previous work revealed a role for the IGS Pol II-dependent asincRNAs and R-loops in preserving nucleolar structure and function. Processes controlling Pol II function at the IGS and whether baseline IGS Pol I function serves a biological function was unclear. Our findings here reveal the regulation of Pol I and Pol II function at the IGS by TBPL1 and PAF1 through different processes and show that baseline Pol I function at the IGS optimizes nucleolar organization and rRNA biogenesis. Specifically, TBPL1 promotes the localization of Pol I and Pol II and consequent synthesis of sincRNAs and asincRNAs at the IGS (Fig. 5a). Downstream of TBPL1-dependent transcriptional initiation, PAF1 supports IGS Pol II elongation, preventing the formation of unscheduled R-loops that can hyper-repress Pol I localization and sincRNA synthesis at the IGS (Fig. 5a). TBPL1 deficiency limits the localization of Pol I and Pol II to the IGS, ultimately hyper-repressing sincRNA levels and altering the localization of FBL relative to NPM and rRNA biogenesis (Fig. 5b). PAF1 deficiency leads to the accumulation of unscheduled R-loops that hyper-repress sincRNA levels and disrupt rRNA production (Fig. 5c). Thus, TBPL1 and PAF1 exert different molecular functions that ultimately converge onto ensuring Pol I-dependent sincRNA production at the IGS. Together, our current and prior work13 indicate that the excessive depletion or accumulation of sincRNAs disrupts nucleolar structure and function (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5. Model for the TBPL1- and PAF1-dependent regulation and roles of Pol II, Pol I, and their ncRNAs at the rDNA IGS.

a At the IGS of wild-type cells grown under standard conditions, TBPL1 at TCT motif-containing IGS sites promotes sense Pol I and antisense Pol II recruitment (i) for the synthesis of sincRNAs and asincRNAs, respectively. Downstream of Pol II transcription initiation, PAF1 promotes the release of Pol II from a natural pause site at IGS20 (ii). Pol II promotes a natural R-loop shield for Pol I (iii). Thus, TBPL1 and PAF1 promote the maintenance of baseline sincRNA levels through different processes. b TBPL1 deficiency reduces the recruitment and function of Pol I and Pol II at the IGS, decreasing the levels of intergenic ncRNAs and abrogating nucleolar structure and function. c Loss of PAF1 induces excessive Pol II pausing at IGS20, leading to total Pol II buildup, depletion of elongating Pol II, and the emergence of unscheduled R-loops, limiting the recruitment of Pol I and its ability to synthesize the baseline levels of sincRNAs needed to ensure nucleolar organization and rRNA biogenesis. d Overall impact of sincRNA levels on nucleolar structure and function.

In conditions where sincRNAs were excessively depleted, we observed an increased number of cells with FBL signal protrusion within or beyond the NPM signal. This different subnuclear organization was associated with altered rRNA biogenesis, and both phenotypes were rescued when sincRNA levels were restored in the PAF1-deficient conditions using the RED system. The alteration of the localization of FBL relative to NPM may ultimately impact rRNA biogenesis via multipronged processes and could implicate the mislocalization of FBL to various non-nucleolar compartments that could be linked to rRNA biogenesis, such as Cajal bodies46,47. Therefore, future research may benefit from exploring the potentially non-nucleolar functions of primarily nucleolar proteins and how such functions may intersect with mechanisms controlling nucleolar structure and function.

Pol II transcription initiation is regulated at multiple levels, including core promoter DNA sequences recognized by different transcription factors. TATA box is a common core promoter recognized by a TATA box-binding protein (TBP) that recruits other transcription factors, including TFIID and TAFs48. The TBP gene was duplicated with modifications during evolution, giving rise to different isoforms such as TBPL1, also known as TBP-related factor 2 (TRF2)49. TBPL1 preferentially recognizes TATA-less promoters with polypyrimidine motifs known as TCT promoters, mostly at ribosomal protein genes21,31. Here, we found that TBPL1 localizes to the rDNA IGS at sites harboring such TCT motifs. Of note, TCT motifs are in the sense orientation at IGS sites where Pol I initiates sincRNA synthesis and in the antisense orientation at IGS sites from which Pol II initiates asincRNA synthesis. So, the positioning and orientation of these TCT motifs is consistent with our data indicating that TBPL1 promotes Pol I and Pol II recruitment and function at the IGS. Our results also revealed that TBPL1 promotes Pol I binding at the rRNA gene promoter. Together, our findings point to TBPL1 as a master regulator of coding or non-coding transcriptional units impacting rRNA manufacturing.

Initiated Pol II commonly undergoes promoter-proximal pausing. Release of Pol II from pausing depends on the balance between the ability of DSIF and NELF to stabilize Pol II in the paused state while pTEFb releases Pol II and promotes transcription elongation50,51. pTEFb, consisting of CDK9, is recruited to Pol II, where it phosphorylates DSIF, NELF, and Ser2 on the CTD of Pol II itself52,53. PAF1 regulates this stage of Pol II transcription through the recruitment of chromatin remodeling and elongation factors. Here, we observed increased Pol II pausing and depletion of H3K36me3 in PAF1-deficient cells, suggesting that PAF1 promotes Pol II transcription elongation at the IGS. This is consistent with studies showing that PAF1C promotes Pol II elongation and the deposition of H3K36me3, H3K4me3, and H2Bub32,54–56. Other studies showed that PAF1C can promote Pol II pausing, but such contrasting findings may be linked to the different systems used or specific genes studied57. Nonetheless, in the absence of PAF1, we observed the accumulation of unscheduled R-loops at IGS20, which can result from excessive or longer Pol II pausing33–35,54. Notably, this IGS region displays a strong guanine-cytosine skew (GC skew), a genomic feature associated with Pol II pausing and R-loop accumulation13,58,59. Also of note, the processes uncovered in our study here may impact tumorigenesis. For instance, cells lacking the BRCA1 tumor suppressor rely on the ability of RNF8 and RNF168 to ubiquitylate and recruit the R-loop-repressive factors XRN2 and DHX9, respectively, to prevent the excessive accumulation of R-loops at the rDNA IGS60,61. Excessive R-loop accumulation in BRCA1-mutant cells deficient in RNF8 or RNF168 stalls cellular growth and prevents tumor growth60,61.

In response to environmental stresses such as heat shock, cells repress asincRNAs and induce the expression of certain sincRNAs13,39,40,42,43. Under such stress conditions, the induced sincRNAs may promote the transition of the nucleolus from a liquid-like to solid-like structure as part of a process that promotes cell survival under stress13,40,42,62,63. Our data here show that baseline sincRNA levels can exert beneficial effects, even in the absence of environmental stress. Our observed non-linear relationship between sincRNA levels and nucleolar function suggests that cells utilize TBPL1 and PAF1 to help maintain optimal IGS ncRNA levels, balanced via competition between intergenic Pol I and Pol II. This balance maintains nucleolar organization, rRNA biogenesis, and de novo protein synthesis. Notably, under heat shock, the abundance of various proteins controlling Pol II function increases in the nucleolus64. We expect future studies to assess the impact of PAF1, TBPL1, and other Pol II regulatory factors on the expression and function of sincRNAs under various conditions including during the activation of the nucleolar stress response as in during heat shock. In addition, under heat shock conditions, a long ncRNA called PAPAS can be transcribed in the antisense orientation to the rRNA gene promoter62. PAPAS may promote the heterochromatinization of the rRNA gene promoter under stress62. Also, the ‘ncRNA’ PAPAS can encode for a protein called Ribosomal IGS-encoded protein (RIEP)65. Of note, RIEP enriches mostly at the Pol II IGS promoter region65. Thus, it will be critical to assess whether the heat-shock-dependent enrichment of RIEP intersects with TBPL1 and PAF1 function to modulate IGS Pol II activity and Pol I-dependent sincRNA synthesis under stress.

Inhibition of Pol II using flavopiridol (inhibits CDK9 phosphorylation of Pol II CTD) or α-amanitin (degrades Pol II) hyper-induces sincRNAs, robustly disrupting nucleolar organization and ribosome biogenesis13. In the presence of Pol II inhibition, partly repressing the hyper-induced sincRNAs using ASOs partially rescues nucleolar organization and rRNA production13. Such partial rescue could be due to the incomplete repression of sincRNAs. Partial rescue only in the context of CDK inhibition may also be tentatively linked to the potential presence of other nucleolar CDK targets66.

We have demonstrated the crosstalk between Pol I and Pol II at the IGS to occur at open chromatin, which is consistent with prior reports suggesting Pol I to preferentially function at rDNA open chromatin in mammalian cells67,68. However, it is important to note that Pol I may operate from nucleosome-free DNA based on a study from yeast69. So future studies will need to investigate whether Pol I operates from nucleosome-free DNA in mammalian cells and how various nucleosome assemblies at the rDNA impact IGS transcriptional activity.

Like all studies, our work here has some limitations. First, we have identified a number of PICs co-enriched with nucleolar Pol II and have extensively characterized TBPL1 and PAF1 function in rDNA regulation. These factors are known to critically affect Pol II via non-direct interactions, as previously determined using molecular and structural studies24,70–72. Though it is outside of the scope of our study, future studies should assess whether the other nucleolar-enriched PICs identified here directly or indirectly interact with or are only in close proximity of nucleolar Pol II. Such studies could include the analysis of protein-protein, protein-RNA, and protein-DNA interactions in vivo and potential binding interfaces in vitro. For instance, the herein identified nucleolar Pol II PICs of MED26 and DR1 coimmunoprecipitate with Pol II and localize to the nucleolar fraction of cells, but we could not detect them at rDNA in ChIP assays. Such PICs may interact with nucleolar Pol II off of chromatin or might colocalize with Pol II onto chromatin at rDNA only under specific conditions. We also note that the broader list of hits from the compBioID may include some factors that interact with Pol II in the nucleoplasm before localizing to the nucleolus. So, future work focusing on nucleolar Pol II-linked PICs from this study should similarly validate their interaction with Pol II, nucleolar localization, and co-localization with Pol II at rDNA or even at perinucleolar chromatin. Second, in addition to the targeted repression of IGS R-loops, the exogenous expression of sincRNAs would have been helpful as an additional tool to rescue defects in TBPL1 or PAF1 deficient cells. However, rescuing phenotypes via such exogenous sincRNA overexpression presents several challenges. These include determining the exact levels and mixtures of distinct sincRNAs needed and achieving perfect nucleolar and sub-nucleolar localization, amongst other problems. We rescued nucleolar structure and function by selectively ablating the unscheduled IGS R-loops in PAF1-deficient cells. So, even if PAF1 can impact myriad processes throughout the nucleus, the targeted ablation of the unscheduled R-loops in PAF1-deficient cells allowed us to isolate the critical molecular event required for the disruption of nucleolar structure and function in PAF1-deficient cells. Third, due to the ability of TBPL1 to impact numerous processes linked to ribosome biogenesis, we could not devise an experiment to rescue rRNA biogenesis in TBPL1-deficient cells. Fourth, other limitations of our study include those linked to using the RED/dRED-based LasR system for targeted R-loop modulation, which we have described in detail previously14. For instance, all limitations associated with CRISPR- and dCas9-based technologies apply to this system, including poorly understood yet rare chromosome rearrangements73. Fifth, rDNA repeats are highly repetitive so our analysis of chromatin at such loci represents an average picture of the state of the repeats across the cell population and should not be interpreted as absolute measurements related to any single rDNA unit, rRNA gene, or IGS region.

Overall, we present the nucleolar proximity-based interactome of Pol II. This interactome helped reveal the regulation of Pol II and Pol I by TBPL1 and PAF1 proteins at the rDNA IGS and the beneficial impact of these two proteins on nucleolar structure and function. We also uncovered the role of Pol I and baseline sincRNAs at the IGS in maintaining rRNA manufacture. Our findings offer important implications for our understanding of cell growth in the presence and absence of environmental stresses and in the context of physiological and pathological settings such as cancer. Finally, we anticipate that the nucleolar Pol II interactome uncovered here will continue yielding critical insights into rRNA biogenesis and other processes in the future.

Methods

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293T) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Wisent Bioproducts) supplemented with 10% (v/v) of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Wisent) and 1% (v/v) penicillin and streptomycin (Wisent) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 condition. 293 T-RExTM cells (ThermoFisher Scientific) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) tetracycline-free FBS and 1% (v/v) penicillin and streptomycin. Flp-In 293 T-REx cells grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Wisent) were used to generate BioID cell lines to interrogate interacting partners of the RNA Pol II subunit POL2RI/RPB9, whose ORF was cloned into a pcDNA5 FRT/TO 3xFLAG MiniTurboID plasmid (Raught Lab)74 such that the biotin ligase fusion is N-terminal to the protein. Stable T-REx lines were generated by transfecting 1 μg of pcDNA5 FRT/TO 3xFLAG MiniTurboID and 2 μg of pOG44 (V600520, Invitrogen) with Lipofectamine3000 (L3000001, Invitrogen) in a 6-well plate at 60% confluency. Cells were passaged into a 10 cm dish and subsequently selected for resistance to 200 μg/mL hygromycin B (Gibco). For knockdown experiments, HEK293T cells at 50% confluence were transfected with 50 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (13778150, Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer in an antibiotic-free growth medium for 48 h. For inhibitory experiments, 2 µM flavopiridol (sc-202157, Santa Cruz; iPol II), 50 ng/ml actinomycin D (A1410-2MG, Simga; LAD/iPol I), or DMSO vehicle control were used. For locus-associated targeting of RED or dRED as part of the LasR system, HEK293T T-RExTM cells were grown at 70% confluence and used as described previously14. For knockdown experiments, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (13778075, Invitrogen). Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) used to knock down sincRNAs were as follows. We used the antisense LNA GapmeR negative control B (339515, LG0000001-DDA; gctcccttcaatccaa), IGS18 (LG00210930-DDA; agtgtgctctgtgaac), IGS20 (LG00210936-DDA; acgcaagaaaggaaga), IGS22 (LG00210956-DDA; acgtgaccgagagaaa) and IGS24 (LG00210966-DDA; gtgacgtgtagagatt). Commercially available siRNAs were used for TBPL1 (L1:L-017254-00-0005, Dharmacon,) and its control (D-001810-10-05, Dharmacon,), and PAF1 (s29267, Thermo Fischer) and its control (4390843, Thermo Fischer). Additional reagents consisting of antibodies, primers, and short RNAs (or their target sequences) used are listed in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

compBioID

Proximity-dependent biotinylation (BioID17) was performed as previously described with modifications to integrate sucrose gradient-based cell fractionation15. Briefly, stable isogenic cell pools expressing FmT-alone (“tag only” controls) or the FmT-fused bait protein(s) were expanded to 5 and 10 × 15 cm2 plates at ~80% confluency for the non-nucleolar-enriched whole-cell control and nucleolar-enriched conditions, respectively. Expression of the fusion protein was induced by the addition of 1 ug/ml tetracycline to the culture media for 24 h. The following day, cells were treated with 50 μM biotin (final concentration) for 60-90 min. Cells planned for the whole-cell control and the nucleolar enrichment were washed twice with S1 solution (1 mM Sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2)75 before scraping the cells using S1 solution and spinning at 162 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The whole-cell control cell pellets were set aside on ice, while the nucleolar enrichment cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μL of S1 solution and sonicated five times at 50% for 10 sec each. 700 μL of S2 solution (1 M Sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2) was then added to the bottom of the tube before spinning at 1800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, after which the supernatant was discarded. The whole-cell control pellet and the purified nucleolar pellet were washed twice with PBS, and the dried pellets were snap-frozen. Pellets were thawed on ice and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH;7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1:500 protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), 1:1000 benzonase nuclease (Novagen)), then incubated on an end-over-end rotator at 4 °C for 1 h, briefly sonicated to disrupt any visible aggregates, and centrifuged at 45,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh 15 ml conical tube. 30 μl of packed, pre-equilibrated (in lysis buffer) streptavidin-sepharose beads (GE) were added, and the mixture was incubated for 3 h at 4 °C with end-over-end rotation. Bound beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 2 min and transferred with 1 ml of lysis buffer to a fresh 1.5 ml tube, washed once with 1 ml lysis buffer and twice with 1 ml of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ammbic, pH 8.3), transferred in ammbic to a fresh centrifuge tube and washed two more times with 1 ml ammbic. Tryptic digestion was performed by incubating beads with 1 μg MS-grade TPCK trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) dissolved in 200 μl of 50 mM ammbic (pH 8.3) overnight at 37 °C. The following morning, an additional 0.5 μg MS-grade TPCK trypsin was added, and the beads were incubated for an additional 2 h at 37 °C. The beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh 1.5 ml tube. The beads were washed twice with 150 μl of 50 mM ammbic, and the washes were pooled with the first eluate, to collect liberated tryptic peptides. The peptide mix was lyophilized and resuspended in buffer A (0.1% (v/v) formic acid). 1/6th of the sample was analyzed per MS run. Validation of biotinylation was conducted using HRP Streptavidin (ab7403, Abcam) western blots. To ensure the analysis of equal material, whole cell and nucleolar fraction BioID experiments used five and ten 15-cm2 cell culture dishes, respectively. These conditions were further validated by the detection of internal control proteins in the non-nucleolar-enriched and/or nucleolar-enriched samples as outlined in the text. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 3% (w/v) BSA in TBST and subsequently incubated with 1:15,000 dilution (v/v) of streptavidin HRP in blocking buffer for 30 min at 23oC. Uncropped blots are in the Source Data file.

Mass spectrometry

High-performance liquid chromatography was conducted using a 2 cm pre-column (Acclaim PepMap 50 mm×100 um inner diameter (ID)), and 50 cm analytical column (Acclaim PepMap, 500 mm × 75 um ID; C18; 2 um; 100 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), running a 120 min reversed-phase buffer gradient at 225 nl/minute on a Proxeon EASY-nLC 1000 pump in-line with a Thermo Q-Exactive HF quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. A parent ion scan was performed using a resolving power of 60,000, then up to the twenty most intense peaks were selected for MS/MS (minimum ion count of 1,000 for activation) using higher energy collision induced dissociation (HCD) fragmentation. Dynamic exclusion was activated such that MS/MS of the same m/z (within a range of 10 ppm; exclusion list size = 500) detected twice within 5 sec were excluded from analysis for 15 sec. For protein identification, Thermo.RAW files were converted to the.mzXML format using Proteowizard76, then searched using X!Tandem77 and COMET78 against the Human RefSeq Version 45 database (containing 36,113 entries). Data were analyzed using the trans-proteomic pipeline (TPP)79 via the ProHits software suite (v3.3)80. Search parameters specified a parent ion mass tolerance of 10 ppm, and an MS/MS fragment ion tolerance of 0.4 Da, with up to two missed cleavages allowed for trypsin. Variable modifications of +16@M and W, +32@M and W, +42@N-terminus, and +1@N and Q were allowed. Proteins identified with an iProphet cut-off of 0.9 (corresponding to ≤ 1% FDR) and at least two unique peptides were analyzed with SAINT Express v.3.681. Twenty control runs (from cells expressing the FlagBirA* epitope tag alone) were collapsed to the four highest spectral counts for each prey and compared to the experimental data, consisting of two biological replicates (each analyzed with two technical replicates). High confidence interactors were defined as those with bayesian false discovery rate (BFDR) ≤ 0.01.

Sucrose gradient-based cell fractionation

Cells grown to 70-80% confluence in 15 cm plates were washed twice with S1 solution (1 mM Sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2)75 before scraping the cells using S1 solution and spinning at 162 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended with 500 μL of S1 solution and an aliquot (~50 μL) was saved on ice as the whole-cell sample. The remaining amount was sonicated five times at 50% for 10 sec each. 700 μL of S2 solution (1 M Sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2) was then added to the bottom of the tube containing the sonicated sample before spinning at 1800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting pellet is the purified nucleolar pellet, while the supernatant is the nucleoplasmic+cytoplasmic sample. A small aliquot (~50–100 μL) of the supernatant was saved as the nucleoplasmic+cytoplasmic sample. The remaining supernatant was centrifuged (13,200 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was saved on ice as the cytoplasmic sample and the pellet was saved on ice as the nucleoplasmic sample. The nucleolar pellet was resuspended in S1 solution, and an additional round of centrifugation was performed to increase purity. Each sample was then resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH8, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) NP-40, 1X protease inhibitor) and needle-shredded before running on SDS-PAGE and further analysis.

RNA extraction

Total RNA was isolated from cells using a Rneasy mini kit (74104, Qiagen) as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was performed as previously described13. In summary, 1 μg of total RNA was treated with Dnase I followed by reverse transcription using dNTPs, random hexamers, 5X first-strand buffer, DTT, RNaseOUT, and MMLV reverse-transcriptase at 25 °C for 10 min, 37 °C for 60 min and 70 °C for 15 min. The cDNA was diluted 1:10 (v/v), and a 4 µL sample was used for qPCR-based analyzes. qPCR reactions were performed at 95oC for 5 min and 60oC for 30 sec, followed by 39 cycles of 95oC for 5 sec and 60oC for 30 sec. ΔΔCt = 2-(ΔCtMutant − ΔCtWT), where ΔCt = Ct(transcript of interest) − Ct(control), and Ct is the cycle threshold.

Strand-specific RT-qPCR (ssRT-qPCR)

We used previously designed primers and followed as described previously. Briefly, separate 10 μL reverse transcription reactions were set up, where 200 ng of purified RNA was incubated with 2.5 nM strand-specific tagged primer, 2.5 nM control strand-specific primer (for example, 7SK), 1 mM dNTPs, 1x first-strand buffer, 10 mM DTT, 40 U RNaseOUT, and 200 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase. For each RNA sample, false-primer reactions were carried out using DEPC ddH2O instead of the transcript of interest. Reactions were carried out in the same cycling as above. cDNA samples were diluted 1:10 (v/v) and amplified using strand-specific primers at the IGS and 7SK. qPCR reactions were performed as above.

Population-level pulse-chase assays

Cells cultured to a 50% confluency in a 6-well plate were pulsed with 20 mM 5-EU for 1 h, followed by either RNA extraction or a 2.5 h chase using non-labeled growth media. Total RNA was isolated as described above in the ‘RNA extraction’ section. Click-iT Nascent RNA capture kit (C10365, Invitrogen) was used as described in the manufacturer’s protocol to isolate 5-EU-ladled RNA. In summary, 1 μg of total RNA was incubated with Click-iT EU buffer, CuSO4, biotin azide, Click-iT reaction buffer additive 1 for 3 min before the addition of Click-iT reaction buffer additive 2 and incubation for 30 min at 23oC. The RNA was precipitated by incubating overnight with UltraPure Glycogen, 7.5 M ammonium acetate, and 100% ethanol at −80 °C, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C and two rounds of washes with 75% (v/v) ethanol. 0.75 µg of the precipitated RNA was then incubated with 2X Click-iT RNA binding buffer and RNaseOUT for 5 min at 67–70 °C followed by the addition of streptavidin beads and incubation for 30 min at room temperature with frequent agitation. The RNA beads were washed five rounds with Click-iT reaction wash buffer 1 followed by wash buffer 2. The beads were then incubated at 68–70 °C for 5 min followed by reverse transcription and qPCR as described above.

Single-cell rRNA biogenesis assays

Cells previously seeded and transfected in 24-well plates were used. On the day of the assay, the cells were exposed to 1 mM 5-fluorouracil (F5130, Sigma; 5-FU) for 15 min, followed by a gentle wash with unlabeled media. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained as described below (see the ‘Immunofluorescence’ section). Staining was performed using antibodies for BrdU (1:500 (v/v)), FBL (1:500 (v/v)), or POLR1A (1:500 (v/v)) antibodies.

Single-cell nascent protein synthesis assays

Cells previously seeded and transfected in 24-well plates were used, and assay was performed using Click-iTTM OPP Alexa FluorTM 647 Protein Synthesis Assay Kit (C10458, Invitrogen)82. Briefly, on the day of the assays, the cells were exposed to 20 μM Click-iT® OPP for 30 min. Cells were then washed with 1X PBS, fixed with 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized using 0.5% (v/v) triton X-100 for 15 min. Staining was performed using Click- iT® Plus OPP cocktail for 30 min before proceeding to DNA staining and mounting of coverslip.

Immunofluorescence

25,000-50,000 cells were seeded on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips for 24 h. Cells were then fixed using 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde for 15 min, followed by three washes with 1X PBS. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 15 min, followed by three washes with 1X PBS before incubation with 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at 23oC. The cells were then incubated with the primary antibody in 5% (v/v) BSA overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. The following day, coverslips were washed thrice with 1X PBS and incubated with the secondary antibody at 1:500 (v/v) in 5% (v/v) BSA. Coverslips were then incubated with 1X DAPI for 5 min before mounting on slides using DAKO mounting media (Agilent Technologies, Cat #S302380-2). Images were captured at 60X or 100X using a Nikon C2+ confocal microscope coupled to NIS-Elements AR software (Nikon). Representative images are the single mid-plane of z-stacks where NPM is enriched at the edge of the nucleolus, and we verified that NPM exhibits a weaker intranucleolar signal in 2D projections of z-stacks, as expected5,13,43,83,84.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

Cells were seeded in 24 well plates with 12 mm coverslips. After 48 h seeding, cells were fixed with 1% (v/v) PFA/PBS for 15 min and washed three times with PBS. Cells were permeabilized with 0.25% (v/v) triton X-100 for 10 min and washed with PBS once. The coverslips were blocked for 1 h at 23oC with 2% (v/v) BSA in PBS. Cells were then incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4 °C (1:500 (v/v) anti-Pol II (sc-17798, Santa Cruz) alone; 1:500 (v/v) anti-PAF1 (ab20662, Abcam) alone; 1:500 (v/v) anti-TBL1 (12258-1-AP, Proteintech) alone or together). Coverslips were washed two times with wash buffer A and incubated in a mixture of PLA probe anti-mouse minus and PLA probe anti-rabbit plus (DUO92101, Sigma) for 1 h at 37 °C. The Duolink in Situ detection reagents (DUO92008, Sigma) were used to perform the PLA reaction according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells with DAPI-counterstained DNA were fixed on a glass slide using MOWIOL.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cells at a 70-80% confluency were washed twice with ice-cold 1X PBS before being lysed using 1X CoIP lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1X protease inhibitor). Lysates were incubated for 30 min with 5 μL of Benzonase under agitation at 4 °C. Lysates were precleared with magnetic Dynabeads protein A (10006D, Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4 °C while 2.5 µg of the antibody was incubated with 10 µL of magnetic beads for 2 h at 4 °C. Then 2.5 mg of the precleared lysate was incubated with the antibody-bead complex for 1 h at 4 °C. The immunocomplex was washed thrice with 1X PBST and eluted off the beads using 50 µL of 2X SDS loading buffer at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Cells grown to 70–80% confluency were crosslinked with 1% (v/v) formaldehyde for 10 min, followed by 5 min incubation with 2.5 mM glycine to quench the reaction. Cells were lysed using lysis buffer (5 mM PIPES, 85 mM KCL, 0.5% (v/v) NP-40, 1X protease inhibitor), incubated on ice for 10 min followed by a 10 min spin at 162 × g. and 4 °C. The cell pellet was incubated with nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, 10 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) SDS, 1X protease inhibitor) for 10 min on ice followed by eight rounds of sonication for 20 sec each at 40% amplitude. Samples were then spun at 12,500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. 50 µL of the sheared chromatin was used for the immunoprecipitation by dilution at 1:10 (v/v) in IP dilution buffer (16.7 mM Tris-HCL pH 8.0, 0.01% (w/v) SDS, 167 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM EDTA, 1.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1X protease inhibitor) and incubation with 2–5 µg of the given antibody overnight at 4 °C with constant rotation. 20% (v/v) of the sheared chromatin was also aliquoted and stored at 4 °C. The immunocomplex was then incubated with pre-washed magnetic Dynabeads protein A (10006D, Invitrogen) for 2 h at 4 °C with constant rotation. The bead-immunocomplexes were then washed with low salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl), high salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl), LiCl wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1% (v/v) NP-40, 1% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM LiCl), and two rounds of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) before incubation twice with elution buffer (1% (w/v) SDS, 100 mM NaHCO3) for 15 min each. The eluates were de-crosslinked by incubating overnight at 65 °C with 200 mM NaCl. The RNA and proteins were depleted from the samples using a 30-min incubation with RNase A (10 mg/mL) and two 2-hour incubations with Tris-HCl (0.04 M, pH 8), EDTA (0.01 M), and proteinase K (0.1 mg/mL) at 45 °C. The DNA was then purified using the Gel/PCR DNA-fragment extraction (DF3000, Geneaid) and diluted at 1:5 (v/v) before qPCR-based analyzes. Analysis performed by calculating adjusted input (% Input) = Log (dilution factor, 2), followed by corrected Ct = 100 × 2(Adjusted Input – Ct IP).

Sequential ChIP (ChIP-re-ChIP)

Before beginning, antibodies to be used for the first round of immunoprecipitation were bound and crosslinked to Protein A/G magnetic beads using PierceTM Crosslink Magnetic IP/Co-IP Kit (88805, Thermo Fischer) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 25 µL of magnetic beads were washed and incubated with 10 µg of antibody for 15 min at 23oC. Samples were then crosslinked by incubating with 20 µM DSS for 30 min at 23oC. The antibody-bead mixture was then washed twice with elution buffer followed by IP buffer. ChIP-re-ChIP was performed similarly to ChIP (see above) but with some modifications. The sheared chromatin is incubated with 5 µg of antibody crosslinked to beads overnight at 4oC. The immunocomplex was washed as done in regular ChIP before eluting off the beads using 50 µL of Elution buffer (pH 2.0) from PierceTM Crosslink Magnetic IP/Co-IP for 5 min. Samples were then neutralized using 4 µL of Neutralization Buffer (pH 8.5) from PierceTM Crosslink Magnetic IP/Co-IP Kit before dilution at 1:10 (v/v) in IP dilution as in ChIP and incubating with 2–5 µg of antibody overnight at 4 °C for the second round of immunoprecipitation. The remaining steps in the protocol were the same as described in the ‘ChIP’ section above.

DNA-RNA hybrid immunoprecipitation (DRIP)

DRIP experiments were performed as previously described13. In summary, cells at 70-80% confluency in 6 cm plates were washed twice with 1X PBS. Cell pellets were resuspended in TE buffer and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 0.5% (w/v) SDS and proteinase K (0.5 mg/mL) for cell lysis and protein digestion. Genomic DNA was isolated using phenol-chloroform followed by precipitation with 3 M NaOAc pH 5.2 and 100% ethanol. The DNA was spooled out and washed with 70% (v/v) ethanol before it was left to dry. The isolated DNA was then resuspended in TE buffer and incubated overnight at 37 °C with HindIII (R01045, New England Biolabs (NEB)), EcoRI (R0101L, NEB), BsrgI (R05755, NEB), XbaI (R01455, NEB), SSPI (R0132, NEB), buffer 2.1, and spermidine. The digested DNA was then purified using 3 M NaOAc pH 5.2, phenol-chloroform, and 100% ethanol before washing it with 70% (v/v) ethanol and leaving it to dry. The precipitated DNA was resuspended with TE (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) buffer. Then, 4.4 µg of DNA was incubated with RNaseH1 overnight at 37 °C before incubating with 10 µg of IgG or S9.6 antibody overnight at 4 °C. The antibody-DNA complexes were incubated with protein G magnetic beads for 2 h at 4 °C, then washed thrice with 1X binding buffer. Alternatively, for His-GFP-dRNH1 DRIP, 5 µg of the sheared DNA was incubated with 5 µg of His-GFP-dRNH1 overnight at 4 °C. The immunocomplex was then incubated with HisPur Ni-NTA magnetic beadsTM (88831, Thermo Fischer) for 2 h at 4 °C, then washed thrice with 1X binding buffer. For both types of DRIP’s, samples were then eluted off the beads by incubating with DRIP elution buffer and proteinase K for 45 min at 55 °C. The DNA was then purified using Gel/PCR DNA-fragment extraction (DF3000, Geneaid) before qPCR-based analyzes. Analysis performed by calculating adjusted input (% Input) = Log (dilution factor, 2), followed by corrected Ct = 100 × 2(Adjusted Input – Ct IP).

In vitro condensation

An ACM corresponding to the VHL-short cationic domain (residues 104–119) was custom synthesized by Biomatik at > 95% purity. Peptide stock solutions were kept at 50 mM in nuclease-free water. FAM-labeled sincRNAs were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville IA) and resuspended in 50 mM NaCl to 100 µM. The sincRNAs at the indicated concentrations were mixed with 25 µM ACM in 150 mM NaCl and imaged after a 10-min incubation. For quantification, three fields of view for each sample were counted using FIJI by equally adjusting thresholds and running the particle analyzer program. The number of condensates in three fields of view was averaged to determine the mean number of condensates per field of view for each independent experiment.

Long-read sequencing of nucleolar RNA

Cells under standard conditions (37 °C) or sincRNA-hyper-inducing conditions (43 °C for 1 h) were washed with PBS, harvested in solution 1 (0.5 M sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2) at 4 °C, and sonicated on ice for 5 × 10 sec using a microtip probe. Samples were then underlaid with solution 2 (1 M sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2) at 4 °C and centrifuged at 1800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Pellets were resuspended in PBS, and a fraction of each sample was used to determine the accurate isolation of nucleoli by microscopic evaluation. The remaining resuspended samples were used for RNA isolation with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Pacbio Sequencing was performed by polyadenylating the RNA using the Poly(A) Polymerase Tailing Kit (PAP5104H, Biosearch Technologies). cDNA Synthesis & amplification were carried out using the NEBNext® Single Cell/Low Input cDNA Synthesis & Amplification Module (E6421S, NEB). Iso-Seq libraries were constructed and barcoded using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (PacBio, 100-938-900). Libraries were pooled and sequenced in two SMRT cells on a Sequel IIe instrument for 30 hours. For Isoseq analysis, the reads were removed of barcodes using lima with isoseq and peek-guess settings. The resultant bam files were refined using Isoseq3 with require-polya setting and clustered using Isoseq3 cluster with verbose and use-qvs settings. Clustered bam files from both flow cells were combined using samtools merge and aligned to GRCh38.primary_assembly.genome.fa with pbmm2 align using preset ISOSEQ, sort, log-level INFO settings. Aligned bam files were visualized using Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV). Binary tiled data was generated using the Count feature on IGV tools and viewed across GL000220.1 to visualize the rDNA cassette.

Statistical analysis