Abstract

This study evaluates the safety and potential benefits of PBM on pancreatic beta cells and islets. PBM was applied to insulin-secreting cell lines (MIN6) and rat pancreatic islets using a 670 nm light source, continuous output, with a power density of 2.8 mW/cm², from 5 s to several 24 h. Measure of cell viability, insulin secretion, mitochondrial function, ATP content, and cellular respiration were assessed. Additionally, a diabetic rat model is used for islet transplantation (pre-conditioning with PBM or not) experiments. Short and long-term PBM exposure did not affect beta cell islets viability, insulin secretion nor ATP content. While short-term PBM (2 h) increases superoxide ion content, this was not observed for long exposure (24 h). Mitochondrial respirations were slightly decreased after PBM. In the islet transplantation model, both pre-illuminated and non-illuminated islets improved metabolic control in diabetic rats with a safety profile regarding the post-transplantation period. In summary, for the first time, long-term PBM exhibited safety in terms of cell viability, insulin secretion, energetic profiles in vitro, and post-transplantation period in vivo. Further investigation is warranted to explore PBM’s protective effects under conditions of stress, aiding in the development of innovative approaches for cellular therapy.

Keywords: Diabetes, Photobiomodulation, Beta cells, Insulinosecretion, Viability, Functionnality, Safety, Long exposure

Subject terms: Biophysics, Cell biology, Endocrinology, Optics and photonics

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) results from the loss of beta cells that produce insulin. As a result, patients with T1D must have daily administration of insulin. However, despite optimal medical care, some patients experiment severe hypo- or hyper-glycaemia leading to unstable diabetes. In this case, islet transplantation can be proposed as a therapeutic option. To briefly describe the technique, human islets are obtained from brain-dead donors through pancreas sampling. Then, the pancreas undergoes a complex process of islet isolation followed by islet transplantation in diabetic recipients1. Pancreatic islet transplantation demonstrated its positive effect on metabolic parameters and quality of life2–4. However, to achieve this control of metabolic parameters, 2–3 grafts are needed due to the high loss of islet after injections5,6. Several investigations are ongoing to address these issues, including tissue engineering to protect islets during engraftment or finding alternative cell types, such as stem cell-derived beta cells.

Photobiomodulation (PBM), also known as low-level laser therapy, has been extensively explored, with over 800 publications per year indexed in Medline since 2020. PBM involves the selective absorption of specific wavelengths (from red to near-infrared) by chromophores, leading to biological modifications. Numerous preclinical and clinical studies have investigated the potential of PBM in diabetes-related complications7 (retinopathy, neuropathies, wound healing). Indeed, in our most recent review7, PBM has been shown to reduce pain and improve the quality of life for patients with diabetic neuropathy, as well as enhance diabetic wound healing by promoting angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, and collagen density. Finally, clinical studies have reported that PBM induces a reduction in fasting and postprandial glycemia, suggesting an impact of PBM on beta cells and islets. However, only a few have focused on insulin secretion8 or its direct effects on beta cells9 and islets10,11 with inconsistent results.

The principle of PBM is likely governed by the Arndt-Schultz law12, where low doses do not produce an effect and high doses are detrimental13–15. However, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms leading to PBM effects remain unclear but involve mitochondria. PBM increases mitochondrial membrane potential, modulates reactive oxygen species (ROS), increases adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and by extrapolation has an impact on the mitochondrial respiratory chain especially cytochrome C oxidase (CCO) that had its absorption peak in the range used in PBM16,17. This results in a reduction of oxidative stress, leading biologically to anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and tissue regeneration effects18,19. Since PBM affects mitochondria, and the mitochondria of islets are particularly sensitive to oxidative stress18 (which occurs notably during islet transplantation), PBM could be considered as a strategy to mitigate the impact of this oxidative stress. However, it is crucial to first ensure the safety of PBM on the basal functions of islets.

As PBM was usually applied from second to minute, in this study, we aimed to evaluate the long-term safety of PBM (in hours) on pancreatic beta cell line, pancreatic rat islets on viability and functionality in basal conditions, and on rat islets graft in diabetic rats. This first-up preliminary study will lay the template for future experimental study examining the effects of PBM on condition related to human pancreatic islet transplantation.

Results

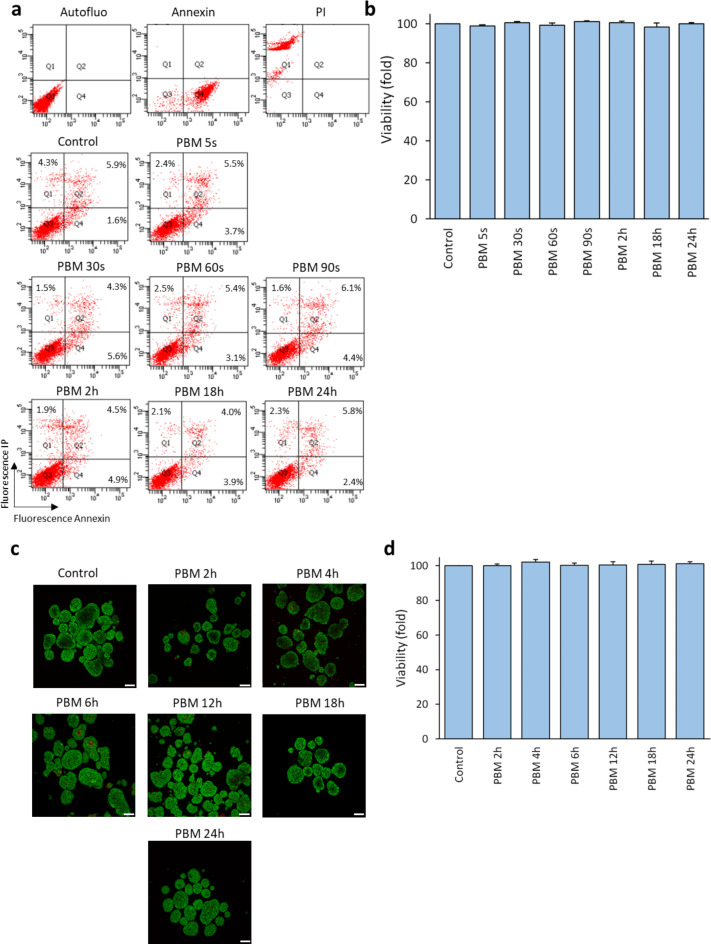

PBM did not altered MIN6 cells nor rat islets’ viability

No difference was observed between control and illuminated conditions for viability (p = 0.408, Fig. 1a and b for MIN6 cells, and p = 0.791, Fig. 1c and d for rat islet).

Fig. 1.

Effect of PBM on the viability of MIN6 cells and rat islets. MIN6 cells and rat islets are exposed to 2.8 mW/cm² PBM illumination. a Results of a representative flow cytometry experiment on the viability of MIN6 cells after PBM. Live cells are in Q3 (annexin-negative and PI-negative). Annexin and PI conditions correspond to death control. b Effect of PBM on MIN6 cells’ viability. Results are normalized to the control value. c Representative images of islet viability experiment by confocal microscopy after PBM. Live cells are labeled with Syto13 (green) and dead cells are labeled with PI (red). d Effect of PBM on rat islets’ viability. Results are normalized to the control value. PBM: photobiomodulation, PI: propidium iodide. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM,n = 4, Scale bares = 100 μm, One-way ANOVA Kruskal–Wallis’s test with pairwise comparison.

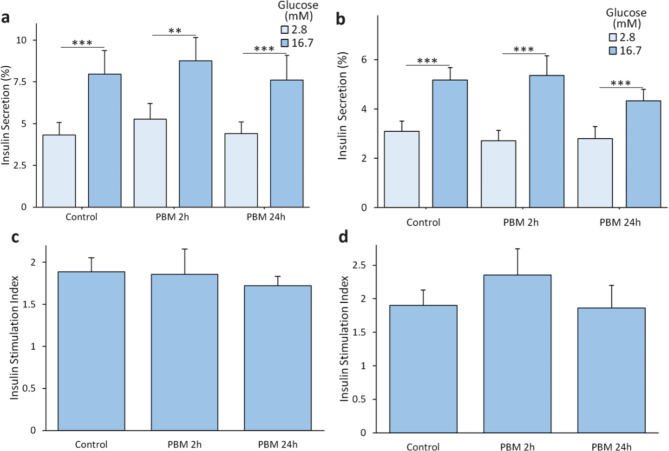

PBM did not altered MIN6 cells and rat islets’ insulin secretion

No difference was observed between control and illuminated condition for insulin secretion in low glucose 2.8 mM (p = 0.707, Fig. 2a for MIN6 cells, and p = 0.760, Fig. 2b for rat islets), in high glucose 16.7 mM (p = 0.847, Fig. 2a for MIN6 cells, and p = 0.470, Fig. 2b for rat islets) or insulin stimulation index (p = 0.700, Fig. 2c for MIN6 cells, and p = 0.718, Fig. 2d for rat islets).

Fig. 2.

Effect of PBM on insulin secretion of MIN6 cells and rat islets. MIN6 cells and rat islets are exposed to 2.8 mW/cm² PBM illumination. a Effect of PBM on MIN6 cells’ insulin secretion (normalized to total insulin content) in response to glucose (n = 8). Results are normalized by total insulin content. b Effects of PBM on islets’ insulin secretion (normalized to total insulin content) in response to glucose (n = 5). Results are normalized by total insulin content. c Effect of PBM on MIN6 cells’ insulin stimulation index (high glucose insulin secretion/low glucose insulin secretion)). d Effect of PBM on islets’ insulin stimulation index. PBM: Photobiomodulation. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, One-way ANOVA Welch’s with Games Howell post-hoc test, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

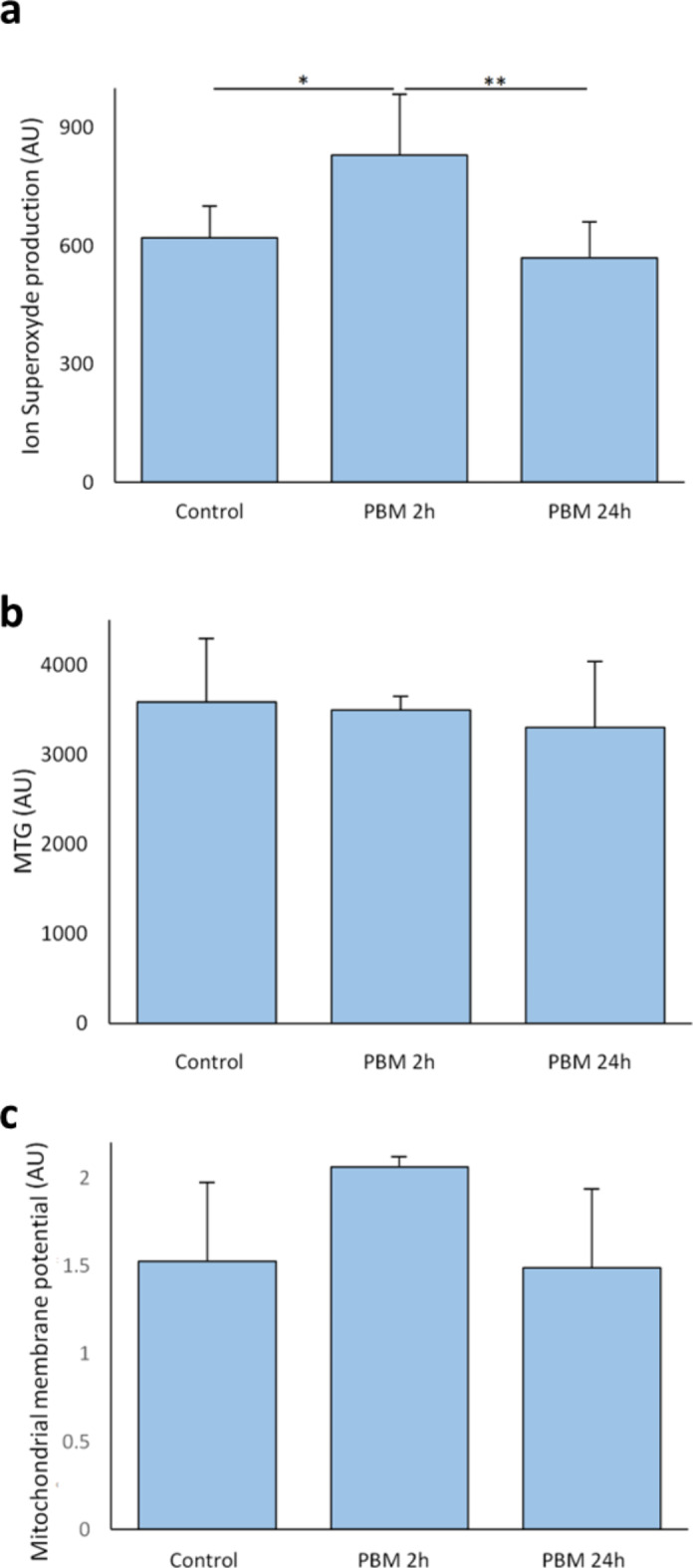

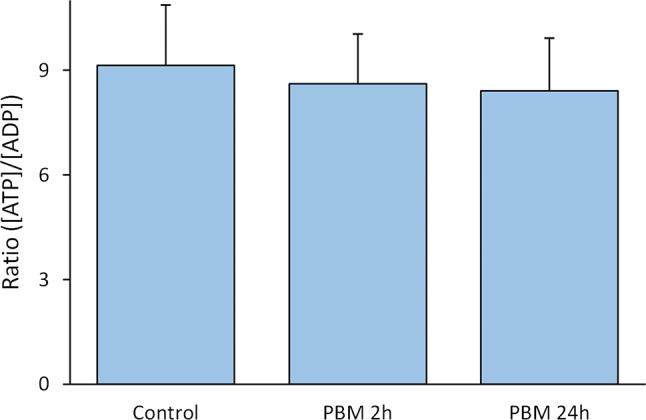

Superoxide content was slightly modified after 2 h of PBM but not after 24 h, but mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP/ADP ratio were not affected by PBM

MIN6 superoxide content was significantly higher than control after 2 h of PBM (829 ± 155 vs. 620 ± 80, p = 0.023) but did not differ from control after 24 h of PBM (569 ± 92, p = 0.63, Fig. 3a). PBM did not altered mitochondrial mass (Fig. 3b) nor the mitochondrial membrane potential of MIN6 (Fig. 3c). PBM did not altered ATP/ADP ratio of MIN cells (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Effect of PBM on superoxide content and mitochondrial membrane potential of MIN6 cells. The MIN6 cells are exposed to 2.8 mW/cm² PBM illumination. a Effect of PBM on MIN6 cells’ superoxide content. Data are expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity. (n = 3 for PBM 2 h,n = 6 for PBM 24 h). b Effect of PBM on the MIN6 cells’ mitochondrial masse. c Effect of PBM on the MIN6 cells’ mitochondrial membrane potential (n = 3 for PBM 2 h,n = 5 for PBM 24 h). Data obtained by flow cytometer and expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity. The mitochondrial membrane potential is (TMRM-CCCp)/MTG. AU: Arbitrary unit; MTG: Mitotracker Green™; PBM: photobiomodulation. Results expressed as the mean ± SEM, One-way ANOVA Welch’s with Games-Howell post-hoc test, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Fig. 4.

Effect of PBM on ATP/ADP of MIN6 cells. The MIN6 are exposed to 2.8 mW/cm² PBM illumination. PBM: photobiomodulation. Results are obtained by HPLC and expressed as the mean ± SEM,n = 7, One-way ANOVA Welch’s with Games-Howell post-hoc test.

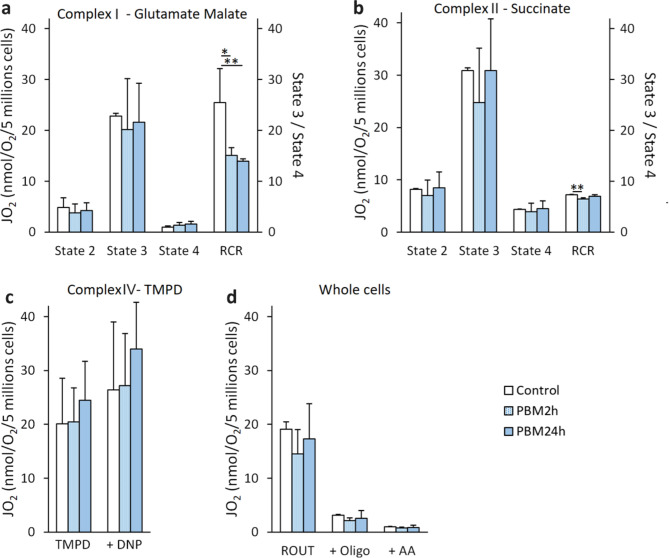

Mitochondrial and cell respiration were slightly affected by PBM

For complex I, PBM significantly decreased RCR if applied during 2 h (15.1 ± 1.5 nmol/O2/min/5 million of cells (JO2), p = 0.012) or 24 h (13.9 ± 0.5 JO2, p = 0.006) compared to control (25.5 ± 6.7 JO2, Fig. 5a). For complex II, PBM decreased respiratory control ratio (RCR) if applied during 2 h (6.3 ± 0.3 JO2, p = 0.002) compared to control (7.1 ± 0.1 JO2) but had no impact if applied for 24 h (6.9 ± 0.3 JO2, p = 0.319, Fig. 5b). For complex IV, PBM did not affect oxygen consumption in uncoupled conditions (DNP) if applied for 2 h (26.5 ± 9.4 JO2, p = 0.998) or 24 h (33.1 ± 8.4 JO2, p = 0.580) compared to control (25.7 ± 12.3 JO2, Fig. 5c). The routine respiration of intact cell (ROUT) was not affected by PBM if applied for 2 h (14.5 ± 4.5 JO2, p = 0.390) or 24 h (17.3 ± 6.4 JO2, p = 0.860) compared to control (19.0 ± 1.4 JO2, Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Effect of PBM on mitochondrial and cell respiration of MIN6 cells. The MIN6 cells are exposed to 2.8 mW/cm² PBM illumination. a Effect of PBM on the MIN6 cells’ complex I (glutamate malate) activity. b Effect of PBM on the MIN6 cells’ complex II (succinate) activity. c Effect of PBM on the MIN6 cells’ complex IV (TMPD) activity. d Effect of PBM on respiration of the whole MIN6 cells. AA: antimycin A; Oligo: Oligomycine; PBM: photobiomodulation; RCR: respiratory control ratio (state 3/state 4) graduation is in the right y-axis; ROUT: routine respiration of intact cells. Results are obtained by oxygraphy and expressed as nmol of oxygen consumed per minute per 5 million live cells. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM,n = 4, One-way ANOVA Fisher’s with Tukey post-hoc test, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

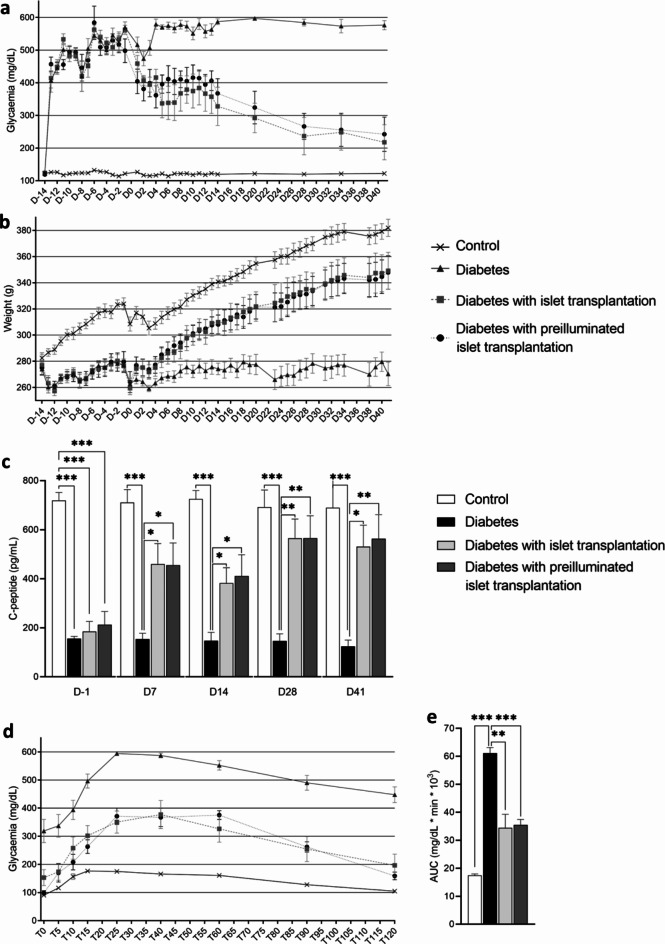

Islet transplantation in diabetic rats increased metabolic control either in case of preconditioning with PBM with non-incremental benefit of PBM

At the time of surgery (Day 0), both blood glucose levels and weight were comparable for diabetic groups (p > 0.6 for both, Fig. 6a and b). Transplantation of control or pre-illuminated islets allowed improvement in glycemia after 3 days (Fig. 6a), body mass after 10 days (Fig. 6b), and C-peptide levels after 7 days (Fig. 6c) as compared to non-transplanted diabetic rats. Glycemia no longer differed from those of the control group after Day 28. C-peptide no longer differed from those of the control group after Day 28. Baseline glucose levels during the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) did not differ between the islet graft groups (illuminated or not) and control groups (p > 0.2) and were lower than those of the diabetic group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6d). In the diabetic group, 100% of the animals exhibited blood glucose levels > 500 mg/dL during the OGTT, compared to one animal in the non-illuminated islet group, none in the pre-illuminated islet group. Higher glucose intolerance was observed in the diabetic group (AUC = 61.1 ± 5.7 mg/dL*min*103) compared to the control group (17.4 ± 1.5 mg/dL*min*103, p < 0.001) and the non-illuminated islet group (34.4 ± 13.7 mg/dL*min*103, p = 0.003) or pre-illuminated islet group (35.5 ± 5.5 mg/dL*min*103, p < 0.001). No difference in AUC is observed between non-illuminated and illuminated islets (Fig. 6e). Regarding safety, no hypoglycemia was observed at any time during the follow-up (early hypoglycemia could be related to initial islet death), nor during the OGTT (hypoglycemia during OGTT could be related to excessive islet activity).

Fig. 6.

Evolution of metabolic parameters after islet transplantation of diabetic rats. a Evolution of glycaemia. b Evolution of body weight. c Evolution of C-peptide secretion. d Glycemia during OGTT, time is expressed in minutes. e AUC of OGTT. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, One-way ANOVA Fisher’s with Tukey post-hoc test, n = 8 per group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we present a first report on the safety of PBM exposure on MIN6 beta cell line, rat islets, and islet transplantation in diabetic rats.

In contrast to studies mentioned in the introduction15,20, our study revealed no toxic effect when cells were exposed to LED illumination at 670 nm, with an irradiance of 2.8 mW/cm² for durations ranging from 5s to 24 h, corresponding to fluence of 14 mJ/cm² to 241.9 J/cm². This difference might arise from the fact that the irradiance used in our study is 100 times lower than the others.

Our work demonstrated that PBM did not influence insulin secretion in MIN6 cells nor rat islets, regardless of glucose concentrations (2.8 mM or 16.7 mM) or insulin stimulation index. To date, only three studies have investigated the effects of PBM on insulin secretion in β cells or islets. Liebman et al.9. reported a 29% increase in insulin secretion at low glucose (0.5 mM) in BTC6 cells (but not- a significant effect in high glucose 3 mM). However, because these cells have different glucose stimulation thresholds than islets (2–3 mM at low glucose and 16.7–20 mM at high glucose), the results are not directly extrapolatable. Irani et al.10. reported a 2.4-fold increase in insulin secretion at a high glucose concentration (16.7 mM) under continuous 830 nm laser illumination (156 mW/cm² for 7s, fluence: 1 J/cm²) and a 3.4-fold increase under continuous 630 nm laser illumination (125 mW/cm² for 8s, fluence: 1 J/cm²). No effect on basal insulin secretion (2.8 mM glucose) was observed. These results may differ from our observations for several reasons. First, the results of the study by Irani et al. were not normalized concerning the insulin content of the islets. Although each condition included 10 islets, their sizes vary significantly in rats (ranging from 50 to 500 μm), and consequently, their insulin content may also vary. Second, while our control islets exhibited an insulin stimulation index close to 2, their values were closer to 1, indicating poor islet secretion capability possibly due to islet stress. It has been demonstrated that the effects of PBM depend on the stress levels of cells. For example, in the presence of inflammation, PBM may have anti-inflammatory effects, whereas in the absence of inflammation, it may exhibit pro-inflammatory effects, which are necessary for tissue remodelling19. Finally, like our study, Huang et al.11. reported no effect of continuous illumination with a 633 nm laser at 1.7 mW/cm² for 9–18 s (irradiance: 15.6–31.3 J/cm²) on insulin secretion in porcine islets, which are known to have low secretion capacity.

Regarding the potential mechanisms of PBM, mitochondrial action, particularly on CCO (complex IV), is highly likely21. In this study, we evaluated various mechanisms involving the production of superoxide ions, mitochondrial membrane potential, cellular energy levels (ATP/ADP ratio), and mitochondrial respiration. Illumination of MIN6 cells for 2 h led to an increase in superoxide content coherent and a decrease in the RCR of complexes I and II. As previously mentioned, the effects of PBM may depend on cell stress levels22. In non-stressed cells (as in our study), PBM increased the mitochondrial membrane potential and associated ROS content. However, excessive ROS production, despite being beneficial in moderate quantities, may be deleterious14. While some studies have proposed an increase in the activity of the respiratory chain based on the combined effects of PBM on mitochondrial membrane potential, ATP production, and the absorption spectrum of CCO, only one study23 demonstrated this hypothesis in isolated horse heart CCO exposed to a 632.8 nm laser at 10 mW/cm² for 200s and a fluence of 2 J/cm². However, these results have not been replicated, regardless of the preconditioning or simultaneous application of PBM during oxygen consumption measurements in isolated CCO24–26. Several studies have reported an isolated increase in ATP production in different cell models (lymphocytes27, liver cells28, neurons29, and cardiomyocytes30). Chaudary et al.31. found no effect of pulsed 635 nm laser illumination (40 mW/cm² for 10 min, fluence: 24 J/cm²) on ATP production in myoblasts and fibroblasts. Interestingly, MIN6 cells exposed to continuous illumination for 24 h showed no alteration in mitochondrial membrane potential, superoxide content, and ATP content. This discrepancy might be attributed to the establishment of a new equilibrium (or transient alteration) in the mitochondrial membrane potential and superoxide after 24 h of illumination, as variations in cellular models are known to be transient. Notably, no effect was observed on the oxygen consumption of complex IV at 2–24 h PBM.

The in vitro study was conducted on non-stressed cells and mildly stressed islets (experiencing no more stress than common stress associated with their isolation). As a result, for the in vivo approach we want to be as much as possible in favorable conditions. A research team showed that in rats, the site of transplantation that led to the best islet survival was the renal capsule, whereas the portal route yielded inferior outcomes32. This is attributed to the well-vascularized and oxygenated parenchyma of the rat renal capsule33, resulting in reduced substrate deficiency. Moreover, the renal capsule graft model is ideal for small animals because of its accessibility. This in vivo model allowed us to study the mid-term safety of islet pre-conditioning before transplantation. As a result, preconditioning islet and control islet presented the same ability to ameliorate glycaemic parameters in diabetic rats.

While previous PBM studies have applied the technique for seconds to several minutes, our study is the first to report the long-term safety of PBM. These results mean that PBM can be considered with peace of mind (absence of toxicity after long exposure) in the islet isolation/transplantation process. Indeed, it has been reported that 50% of transplanted islets are rapidly destroyed by various mechanisms5,6,34, such as inflammatory and cytokine reactions (named instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction (IBMIR)), nutrient deprivation, and hypoxia. Since PBM has demonstrated interesting properties in inflammation and cellular protection19, and as islets are available ex vivo for a period of 24–72 h, preconditioning them before transplantation and the occurrence of such stresses could be considered. Thus, this study (using rat islets with no more stress than common stress associated with their isolation and implantation in a favorable environment to minimize oxidative stress and IBMIR) represents an essential preliminary step before further investigation of this approach in the field of cellular therapy for T1D.

In conclusion, our study shows for the first time that long-term PBM exposure on pancreatic beta cells, rat islets, and rat islets graft in diabetic rats is safe with regard to cell viability, insulin secretion, energetic profile (mitochondrial membrane potential, superoxide ion content, and ATP/ADP ratio) and glycaemic control in vivo. PBM was known to have a positive impact on stressed cells. Future research should focus on investigating the protective effects of PBM against various stresses that may occur after islet transplantation, which will determine whether this approach holds promise for the treatment of T1D.

Methods

Biological materials

The present study was performed in parallel either on insulin-secreting cell lines or primary rodent pancreatic islets. The cell line and primary cells were maintained in a controlled atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

MIN6 cells (immortalized murine pancreatic insulin-secreting β-cells) (AddexBio, San Diego, California, USA) were used and cultured in DMEM 24.8 mM glucose (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin, and 50µM 2-β mercapto-ethanol. Cells were stored for 48 h before experimentation and each condition comprised 400,000 cells.

Rat pancreatic islets were obtained as previously described35. Briefly, male, 8 weeks old, 300 g Wistar rat (Charles River, Lyon, France) pancreases were harvested after injection of a 10 mg/mL collagenase IX solution. The pancreas was then enzymatically and mechanically digested by shaking for 11 min in a water bath at 37 °C. The isolate was then purified by a discontinuous gradient of different densities. Islets were stored for 24 h before experimentation in RPMI 1640, 11 mM glucose (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bourgoin-Jallieu, France) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate, 1% (v/v) L-Glutamine, 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin. All animal experiments were authorized by the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research and approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (APAFIS #41704-2020082615014444).

Photobiomodulation procedure

The illumination was made by a PBM device (EFFI-BL-IP69K, Effilux, Les Ulis, France), wavelength of 670 nm, continuous output power, and irradiance of 2.8 mW/cm² (Table 1). The 670 nm wavelength was extensively used in the literature, and the irradiance was most of the time in mW/cm², as a result, we planned to use these parameters and we planned to vary the exposure times. Short illuminations (a few seconds to several minutes, see Table 1) were made at room temperature. Long illuminations (more than 2 h) were made in a humidity incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). As the illumination bench generates heat, a chiller was added to keep the incubator temperature stable at 37 °C. PBM irradiation parameters were monitored and adjusted using a power and optical energy meter (PM100D, Thorlabs, Newton, New Jersey) with a photodiode power sensor (S120C, Thorlabs). The cells (MIN6) were illuminated 72 h after passage and islets were illuminated 24 h after isolation.

Table 1.

PBM parameters.

| Parameters | PBM |

|---|---|

| Type of light | LED, incoherent light |

| Wavelength | 670 nm |

| Pulse structure | Continuous wave |

| Irradiance | 2.8 mW/cm² |

| Back light panel area | 20 * 30 cm², 90% homogeneity |

| Illumination time | Fluence |

|---|---|

| Short | |

| 5s | 14 mJ/cm² |

| 30s | 84 mJ/cm² |

| 60s | 168 mJ/cm² |

| 90s | 252 mJ/cm² |

| Long | |

| 2h | 20.2 J/cm² |

| 4h | 40.3 J/cm² |

| 6h | 60.5 J/cm² |

| 12h | 121 J/cm² |

| 18h | 181.4 J/cm² |

| 24h | 241.9 J/cm² |

MIN6 cells viability assay

MIN6 cells were detached with 2X trypsin-EDTA, centrifuged for 3 min at 1200 rpm, and rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The pellet (1,000,000 of cells) was re-suspended in 100 µL of specific 1X buffer. Annexin V-FP488 (Interchim, Montluçon, France) was added before incubation for 20 min at room temperature with a final concentration of 2.5 µg/mL. The suspension was then supplemented with 900 µL of PBS and Propidium Iodide (PI) with a final concentration of 10 µg/mL (Thermo Fisher Scientific) just before analysis with a BD LSR Fortessa™ flow cytometer (Beckton-Dickinson Biosciences, Pont-de-Claix, France). It was equipped with two excitation lasers: a Coherent Compass 532 nm laser and a Coherent Sapphire 488 nm laser. The corresponding emission filters are 610/20 nm for PI and 525/50 nm for annexin-FP488. The data acquisition and processing software were BD FACsDivaTM (Beckton Dickinson Biosciences). Results were reported as a percentage of viability from 10,000 events were recorded per condition and defined as negative cells for both labelings (Annexin V-FP488 and PI). Positive control of death was obtained with cells supplemented before analysis with digitonin 2% (v/v). Results were normalized to the control value.

Islet viability assay

Islets viability was analyzed by confocal microscopy on whole and intact islets, previously cultured in a petri dish with a glass bottom (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Austria). Islets were incubated in 2 mL of fully supplemented RPMI 1640 media with 1 µM Syto13 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min in a humid atmosphere (37 °C, 5% CO2) and protected from light36. Briefly, just before analysis, PI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added with a final concentration of 10 µg/mL. The 488 and 532 nm lasers were used at 2% for excitation; the fluorescence emission was collected between 500 and 530 nm for Syto13 and 585–665 nm for IP. Images were obtained using a Leica TCS CSU SP8 confocal microscope (LEICA, Microsystems Heidelberg, Germany) equipped with a Fluotar 10x/0.30 HC PL objective driven by the LasX software. Images were acquired in z-stack with a z-step of 10 μm, and a pinhole of 1 (Airy units) for all channels. Green Syto13 fluorescence labeled live cells while dead cells were labeled by a positive IP nuclear label in red. Quantification was done with a macro on ImageJ software (version 8). The raw images from each channel are loaded separately. Precise feature thresholding is performed and applied to each of the images for each channel to achieve optimum object individualization. Then, the picture is transformed into a binary signal, and a watershed was applied to obtain individualized objects for quantization. Results were expressed as a percentage of viability = 100 * number of green fluorescent cells / (total number of green and red cells), at least 50 islets equivalent (IEQ) were analyzed for each condition. Results were normalized to the control value.

Glucose Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS) assay

GSIS was performed in static incubation using Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer medium (125 mM NaCl, 4.74 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 5 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (w/v) according to the following protocol: wash in 2.8 mM glucose, pre-incubation 1 h at 37 °C in 2.8 mM glucose, incubation 1 h at 37 °C in 2.8 mM glucose (basal condition), then incubation 1 h at 37 °C in 16.7 mM glucose (stimulated condition). All incubation was made in a humid atmosphere (37 °C, 5% CO2). Insulin content was extracted by overnight incubation at -20 °C in ethanol acid solution (375 mL absolute ethanol + 7.5 mL 12.7 M HCl + 117.5 mL distilled water). The incubation supernatants were collected and frozen for later analysis. Insulin assays were performed on incubation supernatants from basal, stimulated, and acid-ethanol extracts. The assays were done by chemiluminescence enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Eurobio Scientific, Les Ulis, France) using the CLARIOstar plate reader (BMG Labtech, Champigny-sur-Marne, France). The results were expressed as a percentage of secreted insulin in relation to the total (contained and secreted), and the insulin stimulation index was (insulin secreted in high glucose / insulin secreted in low glucose). At least 100 IEQ or 1,000,000 MIN6 cells were used for GSIS assay for each condition.

Mitochondrial superoxide content

Superoxide content measurement was performed by flow cytometry. After trypsinization, 1,000,000 total cells were incubated for 20 min in 1 mL of medium containing 1 µM of MitoSOX™ Red (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA), in a humid atmosphere (37 °C, 5% CO2) and protected from light. Fluorescence was measured by a 488 nm laser with PE emission filter (BP 575/26), analysis software remained unchanged, and results were expressed as average fluorescence intensity arbitrary unit.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

Mitochondrial membrane potential measurement of MIN6 was performed by flow cytometry. After trypsinization, 1,000,000 total cells were incubated either in 1 mL of fully supplemented DMEM medium with 100 nM Tetramethyl rhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA), or in 1 mL of fully supplemented DMEM medium with 100 nM Mitotracker Green™ (MTG) (Life Technologies) in a humid atmosphere (37 °C, 5% CO2) protected from light. Cell suspensions were analyzed by FACS with excitation at 488–532 nm and emission bandpass filters 530/30 nm for MTG and 585/15 nm for TMRM, respectively. Mitochondrial mass is estimated by quantification of MTG labeling (fluorescence average). TMRM-labelled cells were then incubated for 15 min with 250 µM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Louis, Missouri, USA). Mitochondrial membrane potential was calculated as a difference in TMRM fluorescence before and after the addition of CCCP and then divided by mitochondrial mass (MTG).

Mitochondrial and cell oxygen consumption

This was performed as previously described37. Briefly, the rate of oxygen consumption was measured at 37 °C using a Clark-type O2 electrode in a 1 mL chamber filled with 500 µl respiration buffer: KCl 125 mM, EGTA 1 mM, Tris HCl 20 mM, pH 7.2. MIN6 were detached with 2X trypsin-EDTA, centrifuged for 3 min at 1200 rpm count, and used for the experiment. Cells were quantified with an automated cell counter (LUNA-II®, Logos Biosystems, Villeneuve d’Ascq, France) after blue trypan exclusion labeling to quantify dead cells.

Complexes I and II MIN6 activity: cells (5 million living cells) were permeabilized with 2% digitonin, measurement was firstly made in the presence of different substrates (state 2): glutamate.

5 mM / malate 2.5 mM (for complex I) or succinate 5 mM / rotenone 1 µM (for complex II), after the addition of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) 0.5 mM (state 3) and followed by the addition of oligomycin 2 µg/mL (state 4).

The RCR was obtained by dividing state 3 (ADP) by state 4 (oligomycin). The RCR reflected how the respiratory was coupled to the ATP production, a decrease in RCR translates into a decrease in ATP production for a given amount of oxygen consumed.

Complex IV MIN6 activity: cells (2.5 million living cells) were permeabilized with 2% digitonin, measurement was made in the presence of antimycin A (AA) 1 µM / Ascorbate 4 mM, followed by TMPD 0.5 mM / Ascorbate 0.25 mM and finally DNP 150 µM.

MIN6 cells oxygen consumption (5 million total cells): measurement was made in DMEM medium (ROUT), followed by the addition of oligomycin 2 µg/mL and finally AA 1 µM. Results were expressed in JO2 (consummation O2 in nmol/min/5 millions of living cells).

ATP/ADP content

After the experiment, 1,000,000 total cells were rinsed 3 times with PBS. Then, attached cells were incubated for a minute in perchloric acid 2.5% EDTA 6.25 mM solution, then detached mechanically, centrifuged (2 min, 13,000 rpm, 4 °C), neutralized by addition of KOMO solution (KOH 2 N and 3-morpholinoproprane-1-sulfonic acid 0.3 M), and centrifuged again (10 min, 13,000 rpm, 4 °C). Protein-free extract (supernatant) was separated on a C18 HPLC column (Polaris 5C18-A, S250*4.6 Repl, Varian, France) in pyrophosphate buffer (28 mM, pH 5.75) at 1 mL/min flow rate and 308 C. ATP and ADP eluted at 3 and 5 min, respectively. Elution peaks were integrated with the STAR software (Varian, France). Results were presented as the ratio of ATP/ADP.

Animal model and groups

This animal experiment followed the ARRIVE guidelines. All animal experiments were authorized by the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research and approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee “COMETH Comité d’éthique en experimentation animale de Grenoble” (APAFIS #41704-2023010617343060). A total of 32 male Lewis rats (syngeneic rats to avoid immune rejection), aged 7 weeks and weighing 240 and 310 g, were obtained from Charles Rivers. All rats were housed under a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 24 °C with ad libitum access to food and water. To induce diabetes, rats were injected intraperitoneally with 1% streptozotocin (STZ, Sigma Aldrich) at a dose of 60 mg/kg of body weight. The control group (n = 8) was injected with diluent. Blood glucose levels were monitored daily, and glycemia above 16.5 mM for more than one day was defined as diabetes. It was estimated that two pancreases were necessary for single islet transplantation (1000 IEQ has been transplanted per rat as previously reported38,39). After islet isolation (from other Lewis rats), they were stored overnight. Half of the islets were illuminated for 24 h and transplanted under the kidney capsule. Groups were as follows: control (n = 8, sham injection, sham surgery), diabetes (n = 8, sham surgery), diabetes with islet transplantation (n = 8, 1000 IEQ per rat), and diabetes with pre-illuminated islet transplantation (n = 8, 1000 IEQ per rat). To obtain a puissance > 90% (α 5%) 8 animals per group were required, and diabetic animals were randomized between the three groups on the day of implantation. Two weeks after STZ injection, all animals were fasted for 12 h, and islet transplantation was performed as previously described40. Briefly, animals were anesthetized and maintained with isoflurane. After an incision was made at the right back side of the animal, the kidney was exposed, and the islets were placed under the kidney capsule. After the surgery, the animals received subcutaneous injections of 0.05 mg/kg of buprenorphine three times a day for two days. For the control group, sham surgery was performed without islets. Glycemia and weight were monitored regularly. Several blood samples were collected to check for C-peptide secretion. Blood was centrifuged at 4 °C at 3000 rpm for 15 min and samples were then stored at -80 °C until analysis. An OGTT was performed 35 days after surgery. The animals were fasted for 12 h and then fed a standard dose of 30% glucose (2 g/kg weight), and glycemia was monitored at different time points: 0, 5, 10, 15, 25, 40, 60, 90, and 120 min. After the experiment, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Euthanasia was performed after anesthesia induction using isoflurane 42 days after the surgery.

Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean value +/- SEM (standard error of the mean), the number of experimentations was indicated in the legend of each figure. All statistical tests were performed by Jamovi software (version 2.25). The different groups were compared by ANOVA (or an equivalent non-parametric test if the application conditions were not met). A value is considered significant if p < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the “Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes”, the Edmond J.Safra Foundation, the “Fond de Dotation-Clinatec” and its sponsors, CEA, UGA, CHUGA. We thank S. Attia for his technical help on ATP/ADP dosage, A. Achouri for her technical help on in vivo experiment and J. Mitrofanis for comments on an early version of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AA

Antimycine A

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- CCCP

Carbonylcyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone

- CCO

Cytochrome C oxidase

- FBS

Fœtal bovine serum

- GSIS

Glucose stimulated insulin secretion

- IBMIR

Instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction

- IEQ

Islet equivalent

- MIN6

Mouse insulinoma cells

- MTG

Mitotracker green

- OGTT

Oral glucose tolerance test

- PBM

Photobiomodulation

- PBS

Phosphate buffer saline

- RCR

Respiratory control ratio

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- ROUT

Routine respiration of intact cells

- STZ

Streptozotocin

- T1D

Type 1 diabetes

- TMRM

Tetramethyl rhodamine methyl ester

Author contributions

Q.P. writing the original draft, conception, plan and carried out analysis, collected the data, data analysis, formal analysis, review, editingC.CR., F.L. contributed to data analysis, carried out experimentsC.T. and J.V. carried follow out of animals, performed OGTT and euthanasia procedureG.V. methodology, carried out the formation on surgeryE.T. conception, methodology, data analysisP.B., A.D., A.P., ML.C. methodology, data analysis C.M. S.L. conception, fundings, supervised the findings. All authors discussed the results and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All constructs created in this work are available from the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Equally contribution

References

- 1.Perrier, Q. et al. Failure mode and effect analysis in human islet isolation: from the theoretical to the practical risk. Islets. 13, 1–9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lablanche, S. et al. Ten-year outcomes of islet transplantation in patients with type 1 diabetes: data from the Swiss-French GRAGIL network. Am. J. Transpl. Off J. Am. Soc. Transpl. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg.21, 3725–3733 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lablanche, S. et al. Islet transplantation versus insulin therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes with severe hypoglycaemia or poorly controlled glycaemia after kidney transplantation (TRIMECO): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.6, 527–537 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vantyghem, M. C., de Koning, E. J. P., Pattou, F. & Rickels, M. R. Advances in β-cell replacement therapy for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Lancet Lond. Engl.394, 1274–1285 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsson, B., Ekdahl, K. N. & Korsgren, O. Control of instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction to improve islets of Langerhans Engraftment. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transpl.16, 620–626 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toso, C. et al. Positron-emission tomography imaging of early events after transplantation of islets of Langerhans. Transplantation. 79, 353–355 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrier, Q., Moro, C. & Lablanche, S. Diabetes in spotlight: current knowledge and perspectives of photobiomodulation utilization. Front. Endocrinol.15, (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Scontri, C. M. C. B. et al. Dose and time-response effect of photobiomodulation therapy on glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients combined or not with hypoglycemic medicine: a randomized, crossover, double-blind, sham controlled trial. J. Biophotonics e202300083 doi: (2023). 10.1002/jbio.202300083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Liebman, C., Loya, S., Lawrence, M., Bashoo, N. & Cho, M. Stimulatory responses in α- and β-cells by near-infrared (810 nm) photobiomodulation. J. Biophotonics. 15, e202100257 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irani, S. et al. Effect of low-level laser irradiation on in vitro function of pancreatic islets. Transpl. Proc.41, 4313–4315 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, H. H., Stillman, T. J., Branham, L. A. & Williams, S. C. The effects of Photobiomodulation Therapy on Porcine Islet insulin secretion. Photobiomodulation Photomed. Laser Surg.40, 395–401 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Freitas, L. F. & Hamblin, M. R. Proposed mechanisms of Photobiomodulation or Low-Level Light Therapy. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. Publ IEEE Lasers Electro-Opt Soc.22, 7000417 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karu, T. Photobiology of low-power laser effects. Health Phys.56, 691–704 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, Y. Y., Sharma, S. K., Carroll, J. & Hamblin, M. R. Biphasic dose response in low level light therapy - an update. Dose-Response Publ Int. Hormesis Soc.9, 602–618 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flores Luna, G. L. et al. Biphasic Dose/Response of Photobiomodulation Therapy on Culture of human fibroblasts. Photobiomodulation Photomed. Laser Surg.38, 413–418 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glass, G. E. & Photobiomodulation A review of the molecular evidence for low level light therapy. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. JPRAS. 74, 1050–1060 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silveira, P. C. L. et al. Effects of photobiomodulation on mitochondria of brain, muscle, and C6 astroglioma cells. Med. Eng. Phys.71, 108–113 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, X. et al. Mitochondria play a key role in oxidative stress-induced pancreatic islet dysfunction after severe burns. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg.92, 1012–1019 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamblin, M. R. Mechanisms and applications of the anti-inflammatory effects of photobiomodulation. AIMS Biophys.4, 337–361 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schalch, T. D. et al. Photobiomodulation is associated with a decrease in cell viability and migration in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Lasers Med. Sci.34, 629–636 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zein, R., Selting, W. & Hamblin, M. R. Review of light parameters and photobiomodulation efficacy: dive into complexity. J. Biomed. Opt.23, 1–17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, Y. Y., Nagata, K., Tedford, C. E., McCarthy, T. & Hamblin, M. R. Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) reduces oxidative stress in primary cortical neurons in vitro. J. Biophotonics. 6, 829–838 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastore, D., Greco, M. & Passarella, S. Specific Helium-neon laser sensitivity of the purified cytochrome c oxidase. Int. J. Radiat. Biol.76, 863–870 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ball, K. A., Castello, P. R. & Poyton, R. O. Low intensity light stimulates nitrite-dependent nitric oxide synthesis but not oxygen consumption by cytochrome c oxidase: implications for phototherapy. J. Photochem. Photobiol B. 102, 182–191 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quirk, B. J. & Whelan, H. T. Effect of Red-to-Near Infrared Light on the reaction of isolated cytochrome c oxidase with cytochrome c. Photomed. Laser Surg.34, 631–637 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quirk, B. & Whelan, H. T. Effect of Red-to-Near Infrared Light and a nitric oxide donor on the Oxygen consumption of isolated cytochrome c oxidase. Photobiomodulation Photomed. Laser Surg.39, 463–470 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benedicenti, S., Pepe, I. M., Angiero, F. & Benedicenti, A. Intracellular ATP level increases in lymphocytes irradiated with infrared laser light of wavelength 904 nm. Photomed. Laser Surg.26, 451–453 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passarella, S. et al. Increase of proton electrochemical potential and ATP synthesis in rat liver mitochondria irradiated in vitro by Helium-neon laser. FEBS Lett.175, 95–99 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong-Riley, M. T. T. et al. Photobiomodulation directly benefits primary neurons functionally inactivated by toxins: role of cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem.280, 4761–4771 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, R. et al. Near infrared light protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia and reoxygenation injury by a nitric oxide dependent mechanism. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol.46, 4–14 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaudary, S. et al. In vitro effects of 635 nm photobiomodulation under hypoxia/reoxygenation culture conditions. J. Photochem. Photobiol B. 209, 111935 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stokes, R. A. et al. Transplantation sites for human and murine islets. Diabetologia. 60, 1961–1971 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlsson, P. O., Palm, F., Andersson, A. & Liss, P. Markedly decreased oxygen tension in transplanted rat pancreatic islets irrespective of the implantation site. Diabetes. 50, 489–495 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onaca, N., Takita, M., Levy, M. F. & Naziruddin, B. Anti-inflammatory Approach with Early double cytokine blockade (IL-1β and TNF-α) is safe and facilitates Engraftment in Islet Allotransplantation. Transpl. Direct. 6, e530 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laporte, C. et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells improve rat islet functionality under cytokine stress with combined upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 and ferritin. Stem Cell. Res. Ther.10, 85 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laporte, C. et al. Improved human islets’ viability and functionality with mesenchymal stem cells and arg-gly-asp tripeptides supplementation of alginate micro-encapsulated islets in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.528, 650–657 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vial, G. & Guigas, B. Assessing mitochondrial bioenergetics by Respirometry in cells or isolated organelles. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ. 1732, 273–287 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He, Y. et al. Reversal of Early Diabetic Nephropathy by Islet Transplantation under the Kidney Capsule in a Rat Model. J. Diabetes Res. 4157313 (2016). (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Hara, Y. et al. Influence of the numbers of islets on the models of rat syngeneic-islet and allogeneic-islet transplantations. Transpl. Proc.38, 2726–2728 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thévenet, J., Gmyr, V., Delalleau, N., Pattou, F. & Kerr-Conte, J. Pancreatic islet transplantation under the kidney capsule of mice: model of refinement for molecular and ex-vivo graft analysis. Lab. Anim.55, 408–416 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All constructs created in this work are available from the corresponding authors.