Abstract

Objective:

We sought to confirm, refute, or modify a 4-step process for implementing shared decision-making (SDM) in pediatrics that involves determining 1) if the decision includes >1 medically reasonable option; 2) if one option has a favorable medical benefit-burden ratio compared to other options; and 3) parents’ preferences regarding the options; then 4) calibrating the SDM approach based on other relevant decision characteristics.

Methods:

We videotaped a purposive sample of pediatric inpatient and outpatient encounters at a single US children’s hospital. Clinicians from 7 clinical services (craniofacial, neo-natology, oncology, pulmonary, pediatric intensive care, hospital medicine, and sports medicine) were eligible. English-speaking parents of children who participated in inpatient family care conferences or outpatient problem-oriented encounters with participating clinicians were eligible. We conducted individual postencounter interviews with clinician and parent participants utilizing video-stimulated recall to facilitate reflection of decision-making that occurred during the encounter. We utilized direct content analysis with open coding of interview transcripts to determine the salience of the 4-step SDM process and identify themes that confirmed, refuted, or modified this process.

Results:

We videotaped 30 encounters and conducted 53 interviews. We found that clinicians’ and parents’ experiences of decision-making confirmed each SDM step. However, there was variation in the interpretation of each step and a need for flexibility in implementing the process depending on specific decisional contexts.

Conclusions:

The 4-step SDM process for pediatrics appears to be salient and may benefit from further guidance about the interpretation of each step and contextual factors that support a modified approach.

Keywords: decision-making, pediatrics, shared

Implementation of shared decision-making (SDM) and measurement of its impact on health care quality are key national priorities.1 Pediatric clinicians, however, struggle with whether and how to implement SDM.2,3 Most SDM scholarship focuses on clinical scenarios of competent adult patients facing acute, one-time interventions for the treatment of disease.4–6 Comparatively few analyses have focused on the use of SDM in situations with decisional features common to the care of children, such as decisions that include longitudinal interventions,7 preventive treatment,8–10 or adolescents11,12 and surrogate decision-makers whose own values and preferences merit some deference.13 The concept and process of SDM in pediatrics therefore remains poorly understood,14–16 thwarting measurement of SDM and interventions to support use of SDM in pediatrics. In fact, there are no instruments specifically designed to measure SDM in pediatrics,17 though recent adaptations of instruments designed for adult patients have shown promise.18

We previously conceptualized a best practice process for implementing SDM in pediatric settings involving young children.19 In that work, we adapted prior work on SDM in the adult setting8,20–25 to pediatric care to account for factors such as the role and authority of parents in decision-making. The SDM process included 4 steps: Medical Reasonableness (Step 1): determine if the decision includes >1 medically reasonable option (with Steps 2–4 applicable to decisions with >1 option, as these are the domain of SDM); Benefit-Burden (Step 2): determine if one option has a favorable medical benefit-burden ratio compared to other options; Preference Sensitivity (Step 3): determine parents’ preferences regarding the options; Calibration (Step 4): calibrate the approach to the decision along a spectrum from parent- to clinician-guided SDM based on the answers to Steps 2 and 3 and other relevant decision characteristics.

Critical to the adoption and reach of this proposed SDM process is that it resonates with clinicians and parents. In this study, we assessed the salience and face validity of this 4-step process by determining whether it aligns with the experiences of parents and clinicians participating in actual decisions across multiple pediatric disciplines, specifically decisions they identify as shared. We sought to identify themes that confirmed, refuted, or modified this process.

Methods

We videotaped a purposive sample of problem-oriented pediatric encounters from 7 clinical services at one US children’s hospital to capture the decision-making process of parents and clinicians across diverse settings, acuity, and complexity. We subsequently interviewed parent and clinician participants that included playback of the video-taped encounter. Interviewers queried participants’ experiences of the decision-making process, including whether participants perceived the decision-making to be shared, and among clinician participants, how and why they may have used SDM. The study was reviewed and approved by the Seattle Children’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Eligible clinicians (M.D., D.O., A.R.N.P., P.A.-C.) were nontrainees and active medical staff on 1 of 7 clinical services (craniofacial, neonatology, hematology/oncology, pulmonary, pediatric intensive care, general pediatrics/hospital medicine, and sports medicine) at Seattle Children’s Hospital, a quaternary medical center. These specialties encompassed a diverse range of medical decision-making scenarios across different settings (outpatient and inpatient), acuity (intensive and nonintensive care), and complexity (specialty and general). Clinicians were recruited via email and staff meeting presentations. To minimize the Hawthorne effect, we described the study’s objective generally as understanding clinician-parent-child communication.26 Clinicians provided informed consent prior to participation and received a $30 gift card at interview completion.

Parents were eligible if they were ≥18 years old, English-speaking, and had a child ≤17 years old who was an inpatient with an upcoming family care conference (FCC) or an outpatient with a problem-oriented encounter scheduled with a participating clinician during the study period. We included parents of adolescents (age ≥11 years old) to begin to understand the applicability of the 4-step SDM process with this age group (though these data are not reported here). We restricted eligibility in inpatient settings to those with an upcoming FCC since medical decisions are often considered at these conferences,27 they represent an opportunity to capture SDM,28 and they could be anticipated by study staff for planning purposes.

Study staff approached eligible parents in inpatient settings prior to an upcoming FCC. Eligible parents in outpatient settings were sent a letter explaining the study prior to their child’s visit with a participating clinician and were then approached in the clinic waiting room after check-in. The study was described to parents as one focused on clinician-parent-child communication. Parents provided informed consent and children ≥7 years old provided assent prior to participation. Parent participants received a $30 gift card at interview completion.

Data Collection

All participants completed a demographic survey at enrollment. Outpatient encounters and inpatient FCCs were video-recorded. For postencounter interviews, we utilized video-stimulated recall (VSR), a method involving playback of videotaped encounters during interviews to explicitly explore routine communication events that participants may proceed through instinctively or inattentively, such as offering information or eliciting beliefs, which are behaviors common to the SDM process.29

Postencounter VSR interviews of parent and clinician participants were conducted separately and done in-person or remotely via Zoom by study staff (D.O., N.D., A. M., H.S.). If the videotaped encounter involved a child ≥11 years old who agreed to be interviewed, the child had the option of being interviewed with their parent (adolescent interview data are not included in this analysis). Otherwise, parent interviews were conducted without the child present. We attempted to complete interviews within 2 weeks of the encounter. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed.

Semistructured interview templates were based on the concepts underlying the 4-step SDM process,19 VSR methodology,30 existing parent interview approaches,31 and literature regarding how parents and clinicians make medical decisions (Appendices 1 and 2).32 These templates were iteratively revised in minor ways over the course of the study to add and improve the quality of probes based on earlier interviews. Study staff (N.D., A. M., H.S.) were trained on standardized VSR interview procedures. First, 2 study staff members (D.O. and either N.D., A.M., or H.S.) independently viewed the videotaped encounter prior to the interview to identify segments that included potential decision-making events using criteria adapted from published work.33 We included any potential decision, not just a decision that appeared to be shared, since we were interested in elements of the decision-making process that helped clinicians or parents distinguish a decision as shared (and how shared decisions aligned with the 4-step SDM process), Study staff subsequently met to compare and resolve any disagreements about included segments. Next, the semistructured interview template was customized to query selected segments. At the start of the interview, participants were asked if they recalled any decisions made in the encounter to ensure those were included if they had not already been preidentified. Selected video segments were then played back for participants, followed by specific questions from the interviewer to elicit the participant’s interpretations of their actions at these moments.

Analysis

We coded postencounter interviews using directed content analysis (DCA). DCA is primarily deductive in nature but also involves open coding to be able to identify new concepts not captured by pre-existing categories.34 We selected this approach in order to confirm, refute, or modify our proposed 4-step process.

A preliminary codebook was developed containing categories corresponding to the 4-step SDM process as well as other components of medical decision-making33 and SDM (Appendix 3).35,36 We also included codes labeled “other” to capture additional themes pertinent to SDM not categorized with an existing code. A training sample of 4 transcribed interviews was then coded by 5 investigators (E.M.W., N.D., H.V., H.S., D.O.) independently to further develop and refine the codebook. The codebook was further revised through discussion with the entire study team. Subsequently, 3 investigators (N.D., H.V., H.S.) separately coded transcripts using the final codebook, then met to compare their coding with disagreements resolved through discussion with a fourth investigator (D.O.). Prior to resolutions of disagreement, we calculated a kappa statistic (k) to determine the degree of coding agreement between these 3 coders (Stata Intercooled 9, Stata Corp, College Station, TX).37 After the first 20 interviews, a k of ≥0.7 was reached between a pair of investigators (N.D., H.V.), suggesting greater than moderate agreement.38 The remaining interviews were coded by this investigator pair, with periodic interviews coded by both investigators independently and k remained ≥0.7. Three investigators (D. O., N.D., H.V.) subsequently reviewed all “other” codes to determine whether they could be categorized as an existing code or represented a new theme. Coding and encounter data were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

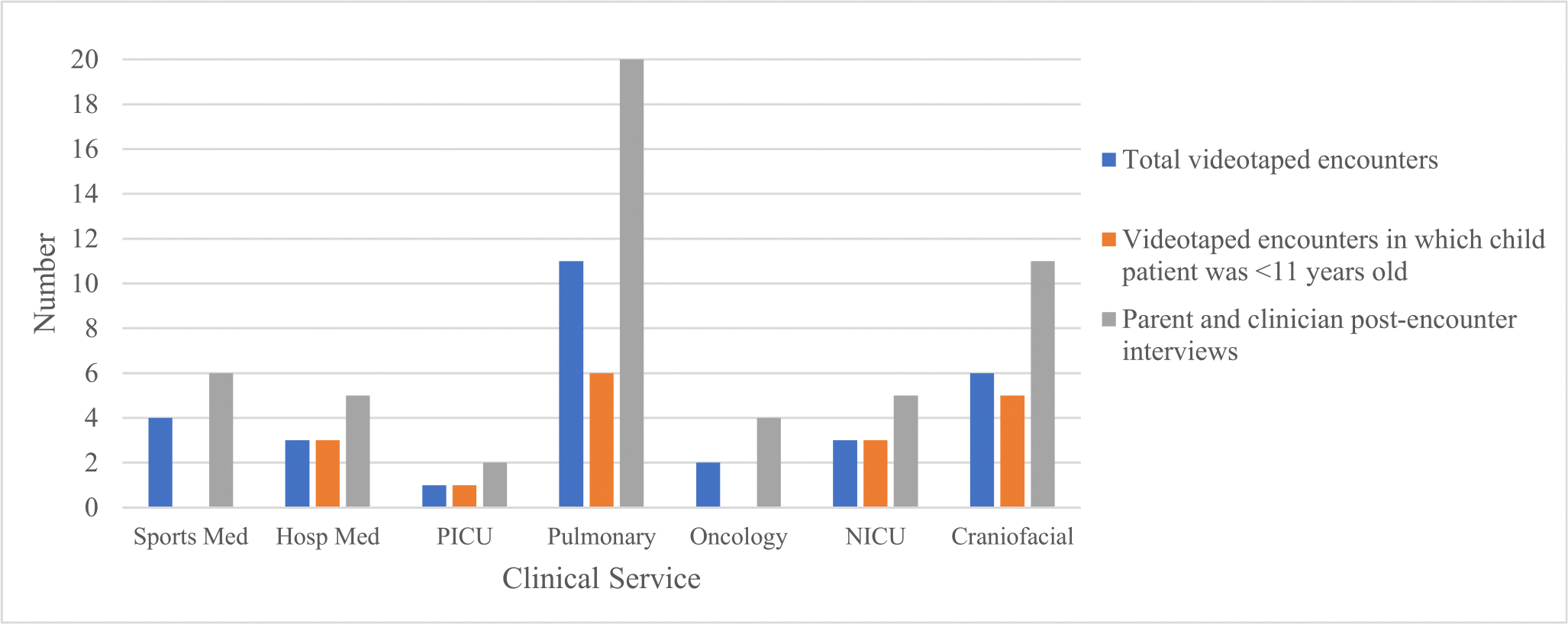

We videotaped 30 encounters, most of which were outpatient encounters (N = 22) and involved parents of children <11 years old (N = 18). There was ≥1 videotaped encounter from each clinical service (Figure). We conducted 53 postencounter interviews of parent and clinician participants: 25 with parents (Table 1A) and 28 with clinicians (23 unique clinicians, with 5 clinicians contributing 2 interviews each; Table 1B). There were 7 encounters in which either a parent participant (N = 5) or clinician participant (N = 2) was lost to follow-up and an interview was not conducted. Interviews were conducted an average of 9 days postencounter (9.72 days [range 1–45 days] for parent participants and 9 days [range 2–19] for clinician participants).

Figure.

Distribution of videotaped encounters and interviews by child age and clinical service.

Table 1A.

Parent Participant Demographics

| Parent Participant Demographics (N = 25) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|

| |

| Relationship to child | |

| Mother | 18 (72%) |

| Father | 7 (28%) |

| Race* | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 |

| Asian | 3 (13%) |

| Black or African American | 2 (8%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (4%) |

| White | 18 (75%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 4 (16%) |

| Age | |

| 18–29 | 4 (16%) |

| >29 | 21 (84%) |

| Education | |

| Eighth grade or less | 0 |

| Some high school, but not a graduate | 0 |

| High school graduate or High school graduate or passed General Educational Development (GED) test | 3 (12%) |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 8 (32%) |

| Four-year college degree | 8 (32%) |

| More than 4-year degree | 6 (24%) |

| Household Income | |

| ≤$30K | 2 (8%) |

| $30,001-$50K | 4 (16%) |

| $50,001-$75K | 4 (16%) |

| >$75K | 15 (60%) |

| Children in household | |

| One | 5 (20%) |

| ≥Two | 20 (80%) |

Participants could select all that apply; missing data from 1 participant who did not provide a response to this item.

Table 1B.

Clinician Participant Demographics

| Clinician Participant Demographics (N = 23)* | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 (61%) |

| Female | 9 (39%) |

| Race | |

| White | 20 (87%) |

| Asian | 3 (13%) |

| Medical specialty | |

| Pediatric intensive care | 1 (4%) |

| Hospital medicine | 2 (9%) |

| Craniofacial | 4 (17%) |

| Pulmonary | 9 (39%) |

| Hematology-oncology | 2 (9%) |

| Neonatology | 3 (13%) |

| Sports medicine | 2 (9%) |

| Years practicing | |

| 0–5 | 7 (30%) |

| 6–10 | 5 (22%) |

| 11–15 | 6 (26%) |

| >16 | 5 (22%) |

Clinicians from pulmonary (N = 1), craniofacial (N = 2), and sports medicine (N = 2) gave 2 interviews, resulting in 28 total clinician interviews.

We identified up to 4 potential decisions per encounter, ranging from topics such as withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment to performing screening tests. There was substantial agreement overall between clinicians and parents regarding what constituted a decision. Across encounters with both clinician and parent interview data (N = 23), 76% of the 54 potential decisions identified were perceived by both parents and clinicians to be decisions.

Salience of the 4 Steps for Implementing SDM

We found substantial support from parent and clinician participants for each step in the proposed 4-step process for implementing SDM. In terms of determining whether to use SDM, we found that the presence or absence of >1 available option was the most cited factor in clinician interviews (N = 18) that influenced how clinicians approached a particular decision (Table 2A), in support of the medical reasonableness step (Step 1). Similarly, a clinician’s explicit or implicit mention of the presence/absence of options helped parent participants (N = 25) perceive whether there was a decision in which they could be involved (Table 2A). Other factors cited in clinician interviews that influenced how they approached a particular decision were their familiarity with the parent and past experiences with this type of decision (N = 16), contextual features such as the amount of time available in the clinical encounter (N = 10), and determinations that the decision was mostly relevant to the clinician or the parent (N = 10) (Table 2A).

Table 2.

(A-D) Representative Quotes Demonstrating the Salience of the 4 Shared Decision-Making (SDM) Steps

| (A) Medical Reasonableness Step (Step 1): Determine If the Decision Includes More Than One Medically Reasonable Option | |

|

| |

| Clinicians | “In my mind, I’m weighing, uh, the options for treatment, which is, uh, which is continue to watch first, or some intervention that could range from oxygen to a jaw surgery.” (MS102) “...I do think [an] important context is that there are multiple ways and multiple approaches to this...” (MS302) “There are times where I think it could go either way. And I basically tell the family that. I’m like, ‘Look, it’s your choice. You can do surgery or not do surgery.’” (MS101) “It probably just has to do with that there’s different ways to approach this...It ends up being like, ‘Hey, there’s these different options.’” (MS702) |

| Parents | “Then towards the end, he gave an option. If I wanted to do the blood allergy testing or not.” (MS401) “I kind of felt more like she was letting me know the options that I had. Whether to come down [on the medication] or I guess come down slowly off of it to completely afterwards.” (MS402) |

|

| |

| Other factors influencing how clinicians approached a decision | |

|

| |

| Familiarity with the parent and their past decision-making | “So I think, probably more than two years ago, we tried peeling back meds, and he actually ended up coming in, having to go to the ED. It was just a complete stumble. And so I hadn’t forgotten that, and clearly I don’t think Dad has either. So that’s always in the back of my mind too.” (MS410) “I was probably building from what I know about them from prior visits and knowing that they’re much more likely to want to check than to not check something, not necessarily lab or anything. And so I interpreted her question to be, um, more like we’re checking again today, right?” (MS409) |

| Contextual features (eg, time) | “Part of it honestly, especially in the last few months, is we’ve been dealing with uh, you know, COVID issues through clinic is, um, trying to kind of get [patients] in and out of the clinic as, as quickly as possible.” (MS101) |

| Relevance to one stakeholder | “I think for the [decision] about [genetic testing to determine] recurrence risk, I think that was something that I felt like was completely up to them and their time and their sort of, you know, priorities in their timeline.” (MS102) |

|

| |

| (B) Benefit-Burden Step (Step 2): Determine If One Option Has a Favorable Medical Benefit-Burden Ratio Compared to Other Options | |

|

| |

| Clinicians | “I think when it came to like thinking about the sleep study is one where I was, I definitely did a benefit burden calculation in my head...I thought this study is gonna have limited, you know, validity at a young age, and [we should get] one at a time when it’s gonna make more sense and be more valid.” (MS102) “So part of it is...how bad would it be to leave things the way they are? Um, and then the other part is, how risky is the surgery compared to how risky is it to leave something the way it is?” (MS101) “This is sort of just based on a combination of guidelines and I guess I think you know what I’m saying...clinical expertise.” (MS401) “I think I thought it made the most medical sense. . . I’ve just seen that in patients who are at risk for recurrent exacerbations... because she has lung issues, that the rate of exacerbations is just, you know, gone through the, gone down to almost zero. So I think her risk would be relatively low.” (MS403) “I think in the long run my goal was to try the bolus feeds, but I also knew there was a risk that he might have more reflux, and worsening respiratory support, and we weren’t going to know that until we tried.” (MS611) |

| Parents | “He gave me enough feedback and kind of enough context around why that was his suggestion that I felt like he got what I was asking.” (MS404) “We had some visibility into what [the doctor] was thinking, and that’s important for me to know.” (MS410) |

|

| |

| Other factors cited by clinicians related to whether or not to favor one option | |

|

| |

| It’s the clinician’s role to weigh in about the options | “I remember thinking to myself, ‘I’ve got to try to convince them that this is the right thing to do.’” (MS405) “it’s, here I am, representing all the knowledge that I have been trained with, and I want to make sure that if I can, the family is aware of that understanding. I can’t wiggle on that, but I can try to wiggle on other things.” (MS408) |

| Assuming that the parent(s) don’t have a preference about the options | “I um, think that um, I was, um. . . evaluating that they probably didn’t have a really strong opinion, and so I weighed in with mine.” (MS403) |

|

| |

| (C) Preference Sensitivity Step (Step 3): Determine Parents’ Preferences Regarding the Options | |

|

| |

| Clinicians | “I really wanted to gauge Mom’s comfort on, I’d like to wait an extra week and have you guys do this, and know this is the right thing. Versus, nope, I want to take him home tomorrow, and I don’t want to make any more changes.” (MS611) “[Parent preferences are] the deciding factor, really. We’re not going to twist their arm and say, ‘You have to have a tracheostomy.’ We also, in this case, wouldn’t force them to not do a tracheostomy Essentially, it’s their child, their decision in this specific situation.” (MS206) “If there’s like, observation, medicine, and surgery, and the family really wants to do medicine, and in my experience that’s not gonna do much but it’s not gonna help a lot, then I might push back a little bit to one of the other two. But I try to understand where they’re coming from and incorporate that.” (MS104) |

|

| |

| (C) Preference Sensitivity Step (Step 3): Determine Parents’ Preferences Regarding the Options | |

|

| |

| Parents | “Someone asked us [to make sure we are on] the same page... ‘what are your goals?’ ...And I felt like they kind of understood what we wanted.” (MS206) “Him explicitly saying, ‘Does this 100% feel okay to you?’ ...gives you the opportunity to kind of go, ‘Well, yeah, I guess I am.’” (MS401) “Just her statement: ‘are you guys okay with it’? And if we’re not, then we can have some more discussions about it.” (MS406) I will say coming out of it...[the doctor] didn’t come back around [to say], “Hey, is he on board with continuing the medication as stated right now?”...It didn’t change the way I felt about the meeting or anything, but I definitely thought about it more in the context because that conversation didn’t loop around to like, “Are you good with that or is this something you still want to do?” (MS410) |

|

| |

| Other factors cited by parents that influenced whether they shared their preferences regarding a specific decision | |

|

| |

| Previous experience with the decision or with decision-making with the clinician | “I feel like we’ve had this conversation, you know, in prior years. And I always look back at the very first time we had the conversation, and I really was like. . .‘I don’t want to do this’. And she was explaining to me why, what the rationale was behind it, and then we were like, ‘Okay, we’ll, try it.’ But then, you know, over the years, I’ve just learned.” (MS403) “Like so two or three visits ago, they were talking about [patient’s] weight increase and wanting to increase his steroids. So when we’re talking about his weight increase in how we’re changing his chemo, that to me just triggers another thought like, ‘Well, about his steroids, you know, are we. . .? Um let’s revisit that and decide if you know if steroid dose is appropriate.’ Because my number one concern is my son’s comfort...” |

| The nature of the available options and/or magnitude of the decision | “We’re always reluctant to put him through something that doesn’t improve his quality of life. And so if he had said, ‘Yeah, the tongue tie is an easy repair. it’s not very painful, and his quality of life could be greatly improved.’ Then I would have said, ‘Let’s do it.’” (MS104) |

| The presence or absence of choice | “He took his time with us to explain everything and gave us that decision. it’s not like he gave us only one option. He actually gave us the three options, so that actually made me feel a lot more comfortable because we had more to choose from, not just what that person thought was best now.” (MS702) |

|

| |

| (D) Calibration Step (Step 4): Calibrate the Approach to the Decision Under Consideration Along a Spectrum From Parent- to Clinician-Guided SDM Based on Steps 1 –3 and Other Relevant Decision Characteristics | |

|

| |

| Clinician-family trust as well as clinician familiarity with the parents and the patient’s medical condition | “I suspect that there are some family encounters where that trust isn’t already there and that might be harder to rely on. Um, and I think, like I do think that I’ve got a framework for what he’s got going on. That makes a lot of sense. So I feel confident in this decision um, I just want families to also feel confident in the decision.” (MS102: clinician) “And the fact that he already had that discussion with me, I kind of related to him. We didn’t have to spend time in this and that was a part of the decision making in a way. I don’t know if everybody gets a continual doctor where someone would spend like 4 weeks, 4 months here and you have a big decision and knowing a lot of why where we were coming from. Looking at this bigger picture and kind of getting assurance and getting confirmation from him helped.” (MS206: parent) |

| Perceived urgency and seriousness of medical condition and/or unfamiliarity with medical condition | “When she was in the ER, I mean she was very ill and I mean honestly I didn’t know much about her condition. So I didn’t really know what to do or what to say. So basically, I just kind of went with what the doctor had to say.” (MS402: parent) |

When there was >1 option, clinicians acknowledged their role included assessing the available options, with their medical judgment emerging as the most prominent factor (N = 24) in determining whether they favored one option over another (Table 2B), in support of the benefit-burden step (Step 2). Less commonly, clinicians cited fulfilling their obligation to communicate their expertise or ensure the best interest of the patient was met as factors that influenced whether they recommended one option over another (N = 16). Other clinicians (N = 9) felt a recommendation was warranted because they assumed that the parent(s) didn’t have a strong opinion about the options (Table 2B). In general, a clinician’s recommendation helped parents recognize that the clinician was weighing medical benefits and burdens of the available options (Table 2B).

For the preference sensitivity step (Step 3), the ability of parents to express their preferences was a central factor cited in both parent (N = 23) and clinician (N = 22) interviews for how shared they perceived the decision-making. The most cited factors in clinician interviews (N = 25) that influenced whether parent preferences were elicited was the acknowledgment that parent preferences mattered in the decision, or conversely, the perception that parents were unlikely to have preferences (Table 2C). Notably, parent preferences were not always elicited or expressed explicitly. In 6 parent interviews, parents mentioned that they only expressed their preferences implicitly, and in 13 clinician interviews, clinicians stated parent preferences were only implicitly elicited.

There were also several factors that parents cited as influencing whether they shared their preferences during a specific decision (Table 2C). Some parents stated an important factor was having previous experiences with the decision or familiarity with the clinician (N = 17). Others stated that sharing their preferences was dependent on the nature of the available options and/or magnitude of the decision (N = 16). Some parents expressed their preferences (or withheld them) purely because of the perceived presence (or absence) of choice (N = 14).

Lastly, several factors seemed to modify the role clinicians and parents played in sharing the decision (Table 2D), consistent with the calibration step (Step 4). Parents and clinicians identified the clinician-family relationship as a factor that influenced how involved or directive they were in the decision-making, and clinicians cited their familiarity with the parents and knowledge of the patient’s medical condition. In addition, parents cited factors such as the perceived urgency and seriousness of their child’s medical condition as other factors influencing their desired involvement in the decision-making.

Emergent Themes about the 4-Step Process Itself

There were several examples from parents and clinicians that highlighted varied ways in which the SDM process was implemented, such as the absence of certain steps, the lack of visibility of all steps to both parties, or a mixed ordering of the steps. One such example was an encounter in which a clinician discussed with a family about whether to conduct cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if their child were to have a cardiac arrest (Table 3A). Though the clinician acknowledged in their interview that both CPR and no CPR were acceptable options (Step 1)—placing this decision within the domain of SDM—the only subsequent SDM step visible in their communication with the family was their assessment of the benefits and burdens of each option and articulation of a clear preference for not attempting CPR (Step 2).

Table 3.

(A-E) Representative Quotes of Emergent Themes Regarding the 4-Step Shared Decision-Making (SDM) Process Itself

| (A) Theme Relating to Not All 4 Steps Being Used During the Encounter for a Decision, Not All Steps Being Visible to Both Parties, and/or the Order of the 4 Steps Varied | |

|

| |

| Clinician discussion with family regarding decision about whether to perform CPR Clinician response to interviewer question: "Tell me what was behind your approach here?" |

“There is one thing that [medical team member] and I were talking about, which is, would CPR be helpful if she was to need that? I’d be pushing on the chest. Um, and I think right now, it would be reasonable to not do that if her heart stopped or wasn’t working enough. That’s something that is unlikely to make her better. And it can certainly be, um, uncomfortable and cause problems, especially when she’s on blood thinners. Um, could have some broken bones. So, my suggestion is that we would not do CPR if her heart was to all of a sudden, stop working. Just wanted you to know. And that’s again something that- especially if this is an infection that we can get her better from, we could re-address any time. It’s not a permanent decision.” “I think the belief that compressions wouldn’t really offer her any survival advantage. Um and can have more morbidity with them. And that making a recommendation for what things are reasonable to offer her was more reasonable and helpful for this quiet family who had shared some of their values with us. So, um, um, that just seemed most appropriate, was just to make a recommendation. And if they had come back and said, no, do everything, which some parents do, then...that also would have been okay.” (MS202) |

|

| |

| (B) Theme Relating to Not Treating Step 1 and Step 2 as Distinct | |

|

| |

| Clinician | “X-ray, from my perspective is such small risk. I’m obviously, so biased, because I’m around it all the time and I do it all the time... We’ll just get these and then we’ll know and be able to rule out all these other things.” (MS702) |

|

| |

| (C) Theme Related to Decisions Feeling Very Joint Because of Past Exploration of Preferences, Even Though These Preferences Weren’t Revisited During the Current Encounter or for the Current Decision | |

|

| |

| Parent | “I honestly, I don’t know if there’s been anything that explicit, where it’s been like, ’What’s your opinion on this?’ I think again because we both are very much on the same page, like we came to the table with the same page that he came to the table, that it has felt very joint.” (MS104) |

|

| |

| (D) Theme Related to Parent Not Expressing Preferences Because of Trust in Clinician or Clinicians Not Being Explicit About All SDM Steps Because of Parents Trust in Them | |

|

| |

| Parent | “So, once you get the feel of trusting the doctors or trust the people that take care of you and or your child, there is very little scope that you feel that you should even think about if it is right or wrong.” (MS206) |

| Clinician | “I suspect that there are some family encounters where that trust isn’t already there and that might be harder to rely on. Um, and I think, like I do think that I’ve got a framework for what he’s got going on. So I feel confident in this decision um, I just want families to also feel confident in the decision.” (MS102) |

|

| |

| (E) Theme Related to Equating Eliciting Parent Preferences With Seeking Their Agreement With a Recommendation | |

|

| |

| Clinician | “Maybe it’s just me wanting to make sure that everybody feels good about the process, but even if it’s a tacit, give me a nod, does it sound reasonable?” (MS702) |

| Clinician | “I think because he was doing well on the medicine, I just wanted to make sure she also understood that and that she’s okay with it.” (MS406) |

CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

There were also examples in which clinicians did not treat Step 1 and Step 2 as distinct: the process of determining whether there is more than one option (Step 1) at times appeared synonymous with determining which option was more favorable (Step 2). For example, regarding the decision to get an x-ray, one clinician communicated to a parent that “we’ll just get” x-rays (Table 3B). Implied here is that there is a choice (Step 1) to get (or not get) an x-ray, placing this decision within the domain of SDM. However, instead of making this choice explicit by describing both options, what was instead conveyed was the clinician’s recommendation (Step 2) based on the clinician’s preference for obtaining x-rays when weighing the medical benefits and burdens. In addition, clinicians may decide whether there is >1 option (Step 1) by determining if they would honor a parent’s refusal of their favored option. In response to the interviewer’s question about whether the parent had a choice to get an x-ray, this same clinician stated: “if they refused, I wouldn’t force them to get an x-ray. If they have concerns about getting a plain film, I wouldn’t just steamroll them and say, ‘You need to get one or I’m not treating you.’”

Lastly, there were examples that complicated and contextualized the application of Step 3. For instance, some participants felt shared decisions were made based on past exploration of preferences, even though these preferences weren’t explicitly revisited during the observed encounter (Table 3C). Similarly, parents did not always feel the need to express their decision preferences because they trusted their child’s clinician (Table 3D). Clinicians also cited that trust in the clinician-parent relationship obviated the need to be explicit about all the steps (Table 3D). Lastly, what it meant to elicit parent preferences differed among clinicians. In particular, there were several interviews (N = 12) in which clinicians, in the context of a decision with >1 option (and therefore, again, the domain of SDM) in which they acknowledged that parent preferences were important to the decision-making, stated that the manner in which they elicited parent preferences was by seeking agreement with their recommendation (Table 3E).

Discussion

In this study, we found that each step in the proposed process for SDM in pediatrics appeared salient to clinician and parent participants across a range of decision-making scenarios. Themes emerged from clinicians and parents regarding how they approached or experienced SDM that were representative of each step, lending face validity to this as a process for implementing SDM in pediatrics. This finding supports emerging consensus regarding the necessary components of SDM35 and underscores the relevance of these components, such as choice awareness, describing options, and eliciting preferences, for SDM in the pediatric setting.39

Although our interviews confirmed the 4-step SDM process, our findings cannot exclude the need for further additions and refinements. Our data, in fact, reveal several new insights into the 4-step process for implementing SDM that may benefit from further guidance about the interpretation of each step and contextual factors that might support a modified 4-step approach. First, our data demonstrated that the 4-step process is a generalization: it is agnostic of the decision context and type. There are various ways this process may be implemented to support SDM in a specific context, such as not using all steps during a specific encounter, not making all steps visible at a specific encounter, or varying the order of the steps. These departures from the 4-step process may not undermine the functionality of the process, but may vary in their appropriateness. For instance, in the context of a long-established, trusting relationship where there is extensive shared understanding about the parent’s values and preferences, SDM can still occur even though a clinician may not explicitly explore parent preferences for the current decision (Step 3). However, in situations where there is less trust, familiarity, and shared understanding (eg, a first time visit between parent and clinician), explicit exploration of the parent’s preferences for a particular decision in which there is >1 option may be more critical for the decision-making process to be considered shared.

Second, and relatedly, departures from the generalized 4-step process may yield a process that is less shared than intended or indicated. For example, conflating the presence of >1 option with favoring one option over another may obscure choice awareness, an important element of SDM.35 Without knowing whether there is >1 option available, parents may simply interpret the clinician’s recommendation as the only option and feel there is no room for SDM at all. Likewise, assuming parent preferences are being elicited if parents simply agree with the clinician’s recommendation falls short of SDM. As Epstein and Peters remind us, “Respecting and responding to patient preferences... means eliciting, exploring, and questioning preferences and helping patients construct them.”40

This raises a third observation. What appears to matter is not just doing these steps, but how they are done. A clinician doing Step 3 suboptimally—by simply seeking parent agreement with the clinician’s preferred option, for instance—has the potential to result in a decision that feels less shared than if the clinician explicitly elicits and explores parent preferences. There are gradations in how each of these steps can be realized, from minimally to fully realized.41

Lastly, we found evidence that clinician determinations of whether there is >1 option—and therefore whether to use SDM—may hinge on assessments of whether they would honor a parent’s refusal of the one medically reasonable option. This, however, is problematic, as there may only be 1 medically reasonable option (eg, to obtain a newborn screening blood sample)—and therefore SDM would not be indicated—yet parental refusal of the 1 medically reasonable option would be respected.42 There may therefore be a need for Step 1 guidance to keep determinations regarding what is medically reasonable separate from determinations of the appropriateness of a parent’s response to medically reasonable options, as these require different considerations: the former is informed by clinical evidence and standards of care and the latter by the risk of harm to the child.43

This study has several limitations. First, videotaping may have affected participant behavior. Previous investigators, however, have demonstrated this effect to be negligible.44 In addition, we tried to minimize the Hawthorne effect by describing the study to participants in general terms. We also asked each participant at the conclusion of their interview whether they felt that the camera affected how they conducted (clinician) or participated in (parent) the encounter, and most participants (48/52 [92%] with missing data from 1 parent encounter) said it had no effect. Second, we approached 60 parent participants to enroll 30, which may have introduced selection bias. Among clinician participants, most who were approached agreed to participate (48/52; 92%), though only 23 out of the 48 participating clinicians were videotaped (48%) given thematic saturation was reached before they had an eligible encounter. Lastly, the representativeness and generalizability of our findings is limited by our small sample, exclusion of non–English-speaking parents, and our study setting (eg, quaternary medical center). In addition, our sampling frame does not account for decision-making that occurs outside of inpatient and outpatient settings (eg, emergency departments).

Conclusions

The 4-step process for SDM in pediatrics appears salient to parents and clinicians and represents a functional and generalized approach to implementing SDM across a range of clinical scenarios. Additional guidance on interpreting each step may further promote the appropriate use of SDM. Nonetheless, this preliminary work provides confidence in the validity of this 4-step SDM process in pediatrics and offers an opportunity to develop and evaluate an instrument to measure SDM anchored to this process.

Supplementary Material

What’s New.

The concept and process of shared decision-making (SDM) in pediatrics remains poorly understood. In this observational study, we identified themes that support a 4-step process for implementing SDM across a range of decision-making scenarios in pediatrics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica Giang for her help with recruiting parent participants and videotaping encounters, Michele Grafelman, MD, for her help with some data interpretation, and Abby Rosenberg, MD, MS, MA, for her help in the design of the study and recruitment of clinician participants.

Financial statement:

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ; grant number R03HS26994–01A1). AHRQ had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2023.01.007.

Contributor Information

Douglas J. Opel, Division of Bioethics and Palliative and Division of General Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Holly Hoa Vo, Division of Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine and Division of Bioethics and Palliative Care, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Nicolas Dundas, Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Heather Spielvogle, Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Amanda Mercer, Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Benjamin S. Wilfond, Division of Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine and Division of Bioethics and Palliative Care, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Jonna Clark, Division of Critical Care Medicine and Division of Bioethics and Palliative Care, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Carrie L. Heike, Division of Craniofacial Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Center for Clinical and Translational Research, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Elliott M. Weiss, Division of Neonatology and Division of Bioethics and Palliative Care, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle, Wash.

Mersine A. Bryan, Division of Hospital Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Center for Clinical and Translational Research, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Seema K. Shah, Department of Pediatrics, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine; Bioethics Program, Lurie Children’s Hospital, Chicago, Ill.

Carolyn A. McCarty, Division of General Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.

Jeffrey D. Robinson, Department of Communication, Portland State University Portland, Ore.

Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby, Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex.

Jon Tilburt, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.

References

- 1.Spatz ES, Krumholz HM, Moulton BW. Prime time for shared decision making. JAMA. 2017;317:1309–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson PL, Fraenkel L. Is shared decision-making the right approach for febrile infants? Pediatrics. 2017;140: e20170225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Opel DJ. A push for progress with shared decision-making in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2017;139: e20162526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Sci Med (1982). 1997;44:681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montori VM, Gafni A, Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect. 2006;9:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller-Engelmann M, Keller H, Donner-Banzhoff N, et al. Shared decision making in medicine: the influence of situational treatment factors. Patient Educ Counsel. 2011;82:240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan RM. Shared medical decision making. A new tool for preventive medicine. Am J Prevent Med. 2004;26:81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keirns CC, Goold SD. Patient-centered care and preference-sensitive decision making. JAMA. 2009;302:1805–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malone H, Biggar S, Javadpour S, et al. Interventions for promoting participation in shared decision-making for children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;5: CD012578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss EM, Clark JD, Heike CL, et al. Gaps in the implementation of shared decision-making: illustrative cases. Pediatrics. 2019;143: e20183055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiks AG, Jimenez ME. The promise of shared decision-making in paediatrics. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1464–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams RC, Levy. SE Council on children with D. Shared decision-making and children with disabilities: pathways to consensus. Pediatrics. 2017;139: e20170956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyatt KD, List B, Brinkman WB, et al. Shared decision making in pediatrics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronson PL, Shapiro ED, Niccolai LM, et al. Shared decision-making with parents of acutely ill children: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson EG, Cohen J, Signorelli C, et al. What instruments should we use to assess paediatric decision-making interventions? A narrative review. J Child Health Care. 2020;24:458–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valentine KD, Lipstein EA, Vo H, et al. Pediatric caregiver version of the shared decision making process scale: validity and reliability for ADHD treatment decisions. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22:1503–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opel DJ. A 4-step framework for shared decision-making in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2018;142(suppl 3):S149–S156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wirtz V, Cribb A, Barber N. Patient-doctor decision-making about treatment within the consultation—a critical analysis of models. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitney SN. A new model of medical decisions: exploring the limits of shared decision making. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandman L, Munthe C. Shared decision making, paternalism and patient choice. Health Care Anal. 2010;18:60–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray E, Charles C, Gafni A. Shared decision-making in primary care: tailoring the Charles et al. model to fit the context of general practice. Patient Educ Counsel. 2006;62:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kon AA. The shared decision-making continuum. JAMA. 2010;304:903–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gwyn R, Elwyn G. When is a shared decision not (quite) a shared decision? Negotiating preferences in a general practice encounter. Soc Sci Med (1982). 1999;49:437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roethlisberger F, Dickson W. Management and the Worker. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boss RD, Donohue PK, Larson SM, et al. Family conferences in the neonatal ICU: observation of communication dynamics and contributions. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:223–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fox D, Brittan M, Stille C. The pediatric inpatient family care conference: a proposed structure toward shared decision-making. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4:305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paskins Z, McHugh G, Hassell AB. Getting under the skin of the primary care consultation using video stimulated recall: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry SG, Fetters MD. Video elicitation interviews: a qualitative research method for investigating physician-patient interactions. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipstein EA, Dodds CM, Lovell DJ, et al. Making decisions about chronic disease treatment: a comparison of parents and their adolescent children. Health Expect. 2016;19:716–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipstein EA, Brinkman WB, Britto MT. What is known about parents’ treatment decisions? A narrative review of pediatric decision making. Med Decis Making. 2012;32:246–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith MA, Clayman ML, Frader J, et al. A descriptive study of decision-making conversations during pediatric intensive care unit family conferences. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:1290–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayring P Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qual Soc Res. 2000;1. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bomhof-Roordink H, Gartner FR, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Key components of shared decision making models: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9: e031763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Counsel. 2006;60:301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burla L, Knierim B, Barth J, et al. From text to codings: intercoder reliability assessment in qualitative content analysis. Nurs Res. 2008;57:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. 3rd ed. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eaton SM, Clark JD, Cummings CL, et al. Pediatric shared decision-making for simple and complex decisions: findings from a Delphi panel. Pediatrics. 2022;150: e2022057978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information: exploring patients’ preferences. JAMA. 2009;302:195–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valentine KD, Vo H, Fowler FJ Jr, et al. Development and evaluation of the shared decision making process scale: a short patient-reported measure. Med Decis Making. 2021;41:108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics, Committee on Genetics, and, the American College of Medical Genetics, and Genomics Social, Ethical, and Legal Issues Committee. Ethical and policy issues in genetic testing and screening of children. Pediatrics. 2013;131:620–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diekema DS. Parental refusals of medical treatment: the harm principle as threshold for state intervention. Theor Med Bioethics. 2004;25:243–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Themessl-Huber M, Humphris G, Dowell J, et al. Audio-visual recording of patient-GP consultations for research purposes: a literature review on recruiting rates and strategies. Patient Educ Counsel. 2008;71:157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.