Abstract

This paper describes pharmacokinetic analyses of the monoamine-oxidase-B (MAO-B) radiotracer [18F](S)-(2-methylpyrid-5-yl)-6-[(3-fluoro-2-hydroxy)propoxy]quinoline ([18F]SMBT-1) for positron emission tomography (PET) brain imaging. Brain MAO-B expression is widespread, predominantly within astrocytes. Reactive astrogliosis in response to neurodegenerative disease pathology is associated with MAO-B overexpression. Fourteen elderly subjects (8 control, 5 mild cognitive impairment, 1 Alzheimer’s disease) with amyloid ([11C]PiB) and tau ([18F]flortaucipir) imaging assessments underwent dynamic [18F]SMBT-1 PET imaging with arterial input function determination. [18F]SMBT-1 showed high brain uptake and a retention pattern consistent with the known MAO-B distribution. A two-tissue compartment (2TC) model where the K1/k2 ratio was fixed to a whole brain value best described [18F]SMBT-1 kinetics. The 2TC total volume of distribution (VT) was well identified and highly correlated (r2∼0.8) with post-mortem MAO-B indices. Cerebellar grey matter (CGM) showed the lowest mean VT of any region and is considered the optimal pseudo-reference region. Simplified analysis methods including reference tissue models, non-compartmental models, and standard uptake value ratios (SUVR) agreed with 2TC outcomes (r2 > 0.9) but with varying bias. We found the CGM-normalized 70–90 min SUVR to be highly correlated (r2 = 0.93) with the 2TC distribution volume ratio (DVR) with acceptable bias (∼10%), representing a practical alternative for [18F]SMBT-1 analyses.

Keywords: Positron emission tomography, monoamine oxidase-B, astrogliosis, Alzheimer’s disease, neurodegeneration

Introduction

Monoamine oxidases (MAO) catalyze the oxidative deamination of dietary amines and monoamine neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine. Two MAO types have been characterized, MAO-A and MAO-B, based on substrate selectivity, genetic source, protein structure, and tissue distribution. 1 Both are expressed in mammalian brain within the outer mitochondrial membrane. 2 MAO-B expression is higher than MAO-A in most regions of the adult human brain, 3 increases with age, 4 and is predominantly expressed within astrocytes. 5

While astrocytes are important for maintaining brain homeostasis, reactive astrogliosis is characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases, 6 notably Alzheimer’s disease (AD), 7 where overexpressed MAO-B is found in reactive astrocytes surrounding senile plaques.8,9 Reactive astrocytes are present in other neurodegenerative conditions such as aging-related tau astrogliopathy, 10 limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, 11 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobe degeneration, 12 Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, 13 and Parkinson’s disease. 14 MAO-B is therefore an attractive target for in vivo assessment of astrogliosis in neurodegenerative conditions and understanding potential synergistic or independent contributions to their respective clinical phenotypes.

Early attempts at imaging MAO-B using positron emission tomography (PET) were based on irreversibly-bound MAO-B inhibitors such as L-[11C]deprenyl (selegiline). 15 However, the high rate of binding of L-[11C]deprenyl in regions with high MAO-B expression yielded flow-limited outcomes that underestimated true MAO-B concentrations. Deuterium substitution in L-[11C]deprenyl-D2 ([11C]DED) yielded a significant reduction in the rate of enzymatic trapping and reduced flow-delivery weighting of tracer uptake in high MAO-B regions. 16 Consistent with autoradiographic studies, 8 significantly higher in vivo [11C]DED retention was observed in AD cortical regions that correlated with [11C]Pittsburgh Compound-B (PiB) indices of β-amyloid (Aβ) load. 17 Other [11C]DED studies showed higher binding in prodromal stages of both late-onset and familial AD.18,19 However, quantitative assessments of MAO-B using [11C]DED are complicated by its irreversible kinetics and metabolism to R(-)-[11C]methamphetamine, 20 which readily enters brain and binds to monoamine transporters.

To overcome these quantification challenges, ongoing MAO-B radiotracer development is focused on reversibly binding agents such as the 2-oxazolidinone derivate [11C]SL25.1188, which showed high brain uptake and slow peripheral metabolism in baboons. 21 Although the pharmacology of SL25.1188 has not been published, baboon blocking studies of [11C]SL25.1188 with deprenyl and lazabemide suggest MAO-B specific binding. 21 Human studies showed [11C]SL25.1188 to be amenable to pharmacokinetic and graphical analyses yielding a well-identified outcome measure, the total volume of distribution (VT), with acceptable test-retest reproducibility (10–15%) and good agreement with the regional distribution of MAO-B. 22 A limitation of [11C]SL25.1188 is its short-lived (20.4 min) carbon-11 label restricting its practical use. [18F]THK-5351, developed for imaging tau, was later shown to also bind in vivo to MAO-B 23 and has been used for MAO-B imaging in presumed astrogliopathies.24–26 However, its use in AD and other tauopathies is complicated by overlapping tau and astroglial pathology. A structural analog of THK-5351, (S)-(2-methylpyrid-5-yl)-6-[(3-18F-fluoro-2-hydroxy)propoxy]quinoline ([18F]SMBT-1), binds to MAO-B with high affinity (KD = 3.7 nM) but not to MAO-A (IC50 = 0.7 µM) and both Aβ and PHF-tau aggregates (IC50 > 1.0 µM). 27 Autoradiographic studies of human brain tissues showed complete inhibition of [18F]SMBT-1 specific binding by the MAO-B inhibitor lazabemide. 27 Initial in vivo human studies showed [18F]SMBT-1 to have high brain uptake and reversible kinetics, 28 and large reductions (>85%) in [18F]SMBT-1 retention after a 5-day regimen of oral selegiline suggest a robust specific binding signal. 28 A shortcoming of these first-in-human studies is that they were conducted with limited kinetic information (dynamic data in only 10 of 69 participants) and without arterial input function determination to support detailed pharmacokinetic analyses. A semi-quantitative index, the 60-80 min standardized uptake value ratio normalized to subcortical white matter (SUVR60–80), was reported for all participants and reflected the known brain distribution of MAO-B. 8

The present work extends earlier [18F]SMBT-1 studies with the collection of dynamic PET image datasets and metabolite-corrected arterial input functions to support pharmacokinetic analyses of [18F]SMBT-1 in a cohort of elderly subjects displaying a range of Aβ and tau pathologic burden and cognitive impairment. The goal of the present work was to investigate various modeling approaches and methodologic simplifications amenable to [18F]SMBT-1 imaging studies in an elderly subject population where Aβ and tau pathology is frequently observed.

Material and methods

Human subjects

Fourteen older subjects were recruited from cohorts associated with the University of Pittsburgh’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center with prior neuropsychiatric evaluations, consensus clinical diagnoses, and participation in [11C]PiB PET and [18F]flortaucipir (FTP) imaging studies. All participants were non-smokers and screened for disqualifying neurologic, psychiatric, or other medical conditions and recent use of specific drug classes (see Supplementary Methods). The protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB) in accordance with the Belmont Report and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). All participants or their proxies provided written informed consent.

Radiochemistry

[18F]SMBT-1 was synthesized in accordance with previously described methods 27 with minor modifications (Supplementary Methods). Radiochemical purity of the [18F]SMBT-1 final product was >90% with an average molar activity at time-of-injection of 1.43 ± 1.01 GBq/nmol (injected mass: 0.06 ± 0.05 µg; range: 0.01–0.21 µg).

Arterial input function determination

Blood sampling

Arterial blood samples were collected to determine the [18F]SMBT-1 arterial input function (see Supplementary Methods). Thirty-five whole blood samples (0.5 mL) were collected with a frequency of one per ∼6 sec over the first 2 min. Blood samples were centrifuged for 2 min (13,000 g) and 200 µl of the supernatant was pipetted into a tube for counting in a high-efficiency gamma counter (Packard Cobra 5003) and radioactivity concentrations (kBq/mL) determined after correcting for physical decay and the counter efficiency. Eight additional arterial blood samples (3.0 mL) were drawn at prescribed timepoints for the determination of radiolabeled metabolites. A blood sample drawn prior to [18F]SMBT-1 injection was used to measure the plasma free-fraction (fp) using ultracentrifugation. 29 As preliminary studies of human blood indicated that the majority (>96%) of radioactivity after [18F]SMBT-1 injection was associated with the plasma supernatant (data not shown), whole blood measurements of radioactivity were not performed.

Determination of plasma radiolabeled metabolites

The radiometabolite assay methods were modified during the course of the study. In the initial 8 scans, an isocratic reverse-phase HPLC method was employed with a mobile phase of 30% acetonitrile/70% ammonium formate buffer (pH 4.2, 2.0 mL/min) and a Prodigy ODS-3 4.6 × 250 mm analytical column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The serendipitous observation of the splitting of the peak corresponding to unmetabolized [18F]SMBT-1 warranted further investigation as a possible radiolabeled metabolite with similar retention characteristics. A step-gradient HPLC system was used to investigate whether the peak splitting was due to a radiolabeled metabolite or an artifact of protein loading, employing a Novapak C18 analytical column (4 µm, 8 mm × 100 mm) with a C18 µBondapak guard column (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) and two solvents: 100% solvent A (5% acetonitrile/95% ammonium formate buffer, pH 4.2, 1.0 mL/min for 5 min) switching to 100% solvent B (30% acetonitrile/70% ammonium formate buffer, pH 4.2, 2.0 mL min for 10 min). The step-gradient method completely resolved two separate radiolabeled components and was used for the following 5 subjects. An optimized isocratic reverse-phase HPLC method was used for the last participant (Ryuichi Harada, personal communication) employing a mobile phase of 40% acetonitrile/60% 20 mM monosodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5, 1.0 mL/min) and an InertSystain® (GL Sciences USA, Rolling Hills Estates, CA) C18 column (5 µm, 7.6 mm × 150 mm).

The [18F]SMBT-1 unchanged fraction data was fit using a variety of models, including one-, two-, and three-exponential, Hill, 30 and Watabe models 31 to determine a function describing the [18F]SMBT-1 time-varying unchanged fraction to correct the plasma radioactivity curve for radiolabeled metabolites. Models were compared using the residual sum-of-squares to select the optimal model.

Imaging

[18F]SMBT-1 PET imaging

All [18F]SMBT-1 PET scans were acquired on a Siemens Biograph mCT Flow™ TrueV PET/CT scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA), acquiring 109 transverse image planes (2.027 mm) over a 22.1 cm axial field-of-view (FOV) with a maximum intrinsic spatial resolution (NEMA NU-2, 2007) of 4.1 mm FWHM (transverse) × 4.7 mm FWHM (axial). 32

In preparation for blood sampling, radial artery catheterization was performed under local anesthesia. An intravenous catheter was placed in the contralateral forearm for radiotracer injection and fluid replacement. Prior to [18F]SMBT-1 injection, subjects were positioned in the scanner and the head immobilized using a custom restraint. A planar radiograph was acquired for subject positioning, followed by a low-dose (∼19 mrem) CT scan for scatter and attenuation correction. Subsequently, [18F]SMBT-1 (173.9 ± 7.4 MBq) was injected as a slow (20 sec) bolus and 90 min of PET emission data collected in list-mode. PET images were reconstructed on a 256 × 256 × 109 voxel matrix using filtered backprojection with Fourier rebinning (3 mm Hann kernel, voxel size = 1.273 ×1.273 × 2.027 mm) into a dynamic series of 38 frames (16 × 15 sec, 3 × 60 sec, 4 × 120 sec, 15 × 300 sec) with standard corrections for decay, attenuation, scatter, and electronics dead-time applied.

[11C]PiB PET imaging

All participants previously underwent [11C]PiB imaging under other protocols on average 7.3 mo (range: 2.3 mo–48.9 mo) prior to [18F]SMBT-1 imaging to document Aβ status (A+/A−) and load as previously described. 33 Aβ load was assessed using CapAIBL software (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Canberra, Australia) and indexed in Centiloid (CL) units. Aβ status was established using a positivity criterion of >25 CL. 34

[18F]FTP PET imaging

A subset of participants with [11C]PiB data previously underwent [18F]FTP imaging under other protocols on average 3.3 mo (range: 2.3 mo–48.9 mo) prior to the [18F]SMBT-1 imaging session to document tau status (T+/T−) and load as previously described. 35 Tau load was indexed in SUVR units and a sensitivity cutoff of >1.18 SUVR in the MetaTemporal region was used to establish T+. 36

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging

For automated anatomical region of interest (ROI) definition, an accelerated sagittal T1‐weighted magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) MR series was acquired prior to the [18F]SMBT-1 imaging session using a Siemens MAGNETOM PRISMA 3T scanner in conformance with Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 3 (ADNI3) protocols. 37

Image processing

Reconstructed dynamic PET images were corrected for interframe motion and transformed into MR native space (see Supplementary Methods). MR images were parcellated into bilateral cortical and subcortical volumes-of-interest (VOIs) using the default FreeSurfer (v7.1.1) pipeline. 36 A subcortical white matter VOI encompassing the supraventricular cores of the frontal and parietal lobes, the centrum semiovale (CES), was manually defined on the MR image. VOIs were used to sample PET images and generate time-activity curves (TAC) for 24 regions (Supplementary Table S1) representing: 1) regions of high MAO-B expression (e.g., amygdala, putamen); 2) regions lower in MAO-B expression but characterized by high levels of Aβ deposition in AD (e.g., posterior cingulate, precuneus); and 3) candidate reference regions characterized by both low MAO-B expression and low levels of Aβ (e.g., cerebellar grey matter (CGM), CES). TACs were normalized to SUV units using injected dose and body mass.

Pharmacokinetic analyses

PMOD software (v.4.401, PMOD Technologies LLC., Zurich, Switzerland) was used to perform all pharmacokinetic analyses. To support the application of reversible models of radioligand binding we assessed equilibrium conditions using linear regression to test whether tissue:plasma radioactivity ratios attained a constant ratio (slope not significantly non-zero) after some time t*. Target:reference region ratios were computed at each timepoint using CGM and CES as reference tissues. A smoothed curve (2nd order smoothing polynomial, 4 neighbors) representing the first derivative of the time-varying ratios was computed to characterize rates of change in target:CGM and target:CES ratios to assess the time stability of reference-tissue normalized outcomes (e.g. SUVR).

Compartmental models

Compartmental models of radiotracer transport applicable to reversibly binding radioligands under equilibrium conditions were applied to [18F]SMBT-1 data yielding outcomes in conformance with consensus nomenclature. 38 Model configurations examined included one tissue compartment (1TC) and two tissue compartment (2TC) models. Model parameters include rate constants (K1-k4) describing the exchange of tracer between plasma and tissue compartments. These are used to derive the total radiotracer volume of distribution (VT), a measure representing the equilibrium ratio of the total concentration of radioligand in tissue to that in plasma. A 1TC model applies when the exchange of radiotracer between free, non-specifically bound, and specifically bound compartments occurs too rapidly to be distinguished at typical PET noise levels and sampling rates. Here, is defined as where K1 (mL/min/cm3 tissue) and k2 (min−1) describe the influx and efflux between plasma and tissue compartments, respectively. The 2TC model includes parameters k3 and k4 describing the specific binding bimolecular association rate ( , min−1) and dissociation rate ( , min−1), respectively, where Bavail represents the tissue concentration of free target receptors (nmol/L), kon the association rate constant (min−1), and fND a proportionality factor representing the fraction of free ligand in the non-displaceable tissue compartment that cannot be directly measured. In the 2TC model, VT is the sum of the radiotracer specific binding volume of distribution VS ( ) and the non-displaceable volume of distribution VND ( ) such that:

| (1) |

The ratio k3/k4 is referred to as the binding potential relative to non-displaceable uptake, or BPND:

| (2) |

Here, KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant ( , nmol/L) that is an intrinsic property of the ligand-receptor complex and assumed invariant, such that differences in BPND are interpreted to reflect differences in Bavail, such as reduced expression of the target receptor or occupancy by a drug. If a reference region exists that is devoid of radiotracer specific binding, it may be possible to estimate BPND without the use of an arterial input function using reference tissue models. While postmortem tissue studies indicate no brain region is devoid of MAO-B expression, the grey-matter cerebellar cortex (CGM) is consistently lowest among tissues examined.3,8,39 We therefore investigated CGM for use as a pseudo-reference region that best approximates VND in order to estimate BPND using both compartmental modeling and simplified analysis methods to characterize tradeoffs between bias and precision related to their application. CGM was also used to compute the distribution volume ratio (DVR), where DVR = VT/VND, to facilitate direct comparisons with tissue ratio outcomes (SUVR) representing the ratio of radiotracer retention in target tissues to non-target regions. Using the definitions of BPND (equation (2)), VND, and VS above, we note that equation (1) can be reformulated as:

| (3) |

Thus BPND and DVR are trivially related.

In our pharmacokinetic analyses, we examined several 2TC configurations with specific constraints to optimize the identifiability of the [18F]SMBT-1 VT macroparameter as a primary consideration and the identifiability of microparameters (e.g., K1-k4) secondarily, where vB is the vascular volume fraction of brain tissue. Tested 2TC configurations included:

2T5k: A configuration with five fit parameters (K1, k2, k3, k4, vB).

2T4k: A configuration with four fit parameters (K1, k2, k3, k4) and vB fixed to a physiologically appropriate value of 0.05. 40

2T4kK1k2fit: A configuration with four fit parameters (K1, K1/k2, k3, k4) where the macroparameter VND (K1/k2) is fit and vB fixed to 0.05.

2T4kK1k2WB: A configuration with four fit parameters (K1, k3, k4, vB) and the K1/k2 ratio fixed to a value determined by fitting a participant’s whole brain time-activity curve (TAC) using 2T4kK1k2fit.

2T3kK1k2WB: A configuration with three fit parameters (K1, k3, k4) where the K1/k2 ratio is fixed to a whole brain value and vB fixed to 0.05.

In all 2TC configurations, a delay parameter kdelay (sec) accounting for the delay between the delivery of tracer to the brain and the radial artery sampling site was fit using a 90-min whole brain TAC. The kdelay value was used as a fixed parameter to fit regional data.

Non-compartmental models

We examined several non-compartmental models such as the Logan plot that transform the measured input function and tissue TAC into graphical variables enabling the estimation of VT using linear regression. 41 While computationally simple, a limitation of the Logan plot is bias arising from the noisy instantaneous tissue concentration term appearing in the denominator of both predictor and response variables. This correlated noise is only accounted for in the response variable by ordinary least squares fitting, yielding negatively biased VT estimates. Rearranging the Logan plot operational equations, Ichise et al. formulated multilinear regression models for estimating VT that are less vulnerable to this bias. 42 Variations of this method estimating either two parameters (MA1) or four parameters (MA2) have been described, the former of which assumes a linearity condition is satisfied after some time t*, whereas MA2 does not. An error criterion of 10% was used to select t*, which is the earliest sample for which the deviation between the fit and all subsequent measurements used in the regression is <10%.

Reference tissue models

A further methodologic simplification obviates arterial input functions in favor of a reference tissue TAC assumed to be devoid of specific binding. Violations of this assumption may yield bias in specific binding outcomes, 43 although some bias may be tolerated to adopt methodologic simplifications that improve participant recruitment and retention. The reference tissue methods examined include: 1) the reference Logan plot (rLP) that directly estimates DVR from the regression of graphical variables; 44 2) Ichise’s multilinear reference tissue model (MRTM), a reformulation of the MA1 model equation for a reference tissue input estimating BPND and the reference tissue to plasma efflux rate constant k2′; 3) MRTM2, a variation of MRTM that constrains k2′ to the value estimated using MRTM estimating only BPND; 45 and 4) the simplified reference tissue model (SRTM) estimating BPND, k2, and the parameter R1 representing the ratio of the delivery parameter in the target tissue (K1) to reference tissue (K1′) . 46

Tissue ratio (SUVR) methods

SUVR methods do not require blood sampling and use an abbreviated (∼20 min) imaging protocol that is practical and well tolerated. SUVR methods are nearly universal in studies of Aβ and tau pathology using [11C]PiB, 47 [18F]FTP, 48 and [18F]MK6240. 49 The optimal time interval for evaluating SUVR begins at the onset of steady-state conditions between target and non-target tissue radioactivity concentrations. In the present work, we characterized four candidate SUVR normalizing regions: CGM, cerebellar white matter (CWM), whole cerebellum (WCB) and CES. We also examined the time stability of SUVR indices by shifting a 20-min interval for SUVR computation later in 10 min increments beginning at 30 min post-injection.

Statistical analyses

The identifiability of the various models applied to [18F]SMBT-1 was assessed using the corrected Akaike Information Criteria (AICc), a formulation of the AIC 50 appropriate for small samples, 51 and model selection criteria (MSC), a reciprocal modification of AIC independent of the scaling of the data (Scientist software, MicroMath Inc., Saint Louis, MO). The preferred model is the one with the lowest AICc and/or the highest MSC value. We tested normality within the entire sample and between Aβ+ and Aβ− participants using the Shapiro-Wilk test, although for small samples these tests often fail to detect deviations from normality. Regardless of the distribution, we used multiple Mann-Whitney tests to assess the significance of regional differences in [18F]SMBT-1 VT outcomes between Aβ+ and Aβ− subjects with p-values adjusted for a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05. 52 Linear relationships between [18F]SMBT-1 outcomes were assessed using simple linear regression without constraints and expressed in terms of Pearson’s r2. PRISM v.10.1.1 (GraphPad Software, LLC, San Diego, CA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Participants

Participant characteristics are described in Table 1. Briefly, participants had a median (Q1, Q3) age of 75 (74, 80) and 6 (43%) were female. With respect to diagnosis, 8 participants were cognitively unimpaired (CU), 5 had mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and one had a probable AD diagnosis. Six subjects (2 NC, 3 MCI, 1 AD) were determined to be A+. One MCI subject had an Aβ load in the perithreshold range (15–25 CL) and was considered to have indeterminate Aβ status. Twelve participants also underwent FTP imaging of which 5 (2 NC, 2 MCI, 1 AD) were determined to be T+. Due to extreme motion artifacts that could not be satisfactorily corrected, one subject (MCI-3) was excluded from image analyses.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| Subject ID | Sex | Age | Diagnosis | Aβ status (load in CL) | Tau status (MetaTemp SUVR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC-1 | F | 75 | Cognitively unimpaired | negative (1.0) | negative (1.05) |

| NC-2 | F | 75 | Cognitively unimpaired | negative (−1.6) | negative (1.01) |

| NC-3 | M | 79 | Cognitively unimpaired | negative (2.1) | positive (1.20) |

| NC-4 | M | 67 | Cognitively unimpaired | positive (31.3) | negative (1.11) |

| NC-5 | M | 75 | Cognitively unimpaired | negative (5.1) | negative (1.10) |

| NC-6 | M | 82 | Cognitively unimpaired | negative (−11.6) | negative (1.15) |

| NC-7 | F | 74 | Cognitively unimpaired | negative (−0.9) | positive (1.19) |

| NC-8 | F | 76 | Cognitively unimpaired | positive (95.5) | N/A |

| MCI-1 | M | 74 | MCI, abnormal without complaint | negative (−7.4) | negative (1.03) |

| MCI-2 | F | 80 | MCI, abnormal without complaint | indeterminate (18.9) | negative (1.15) |

| MCI-3 a | M | 83 | MCI, amnestic w/other domains | positive (67.3) | positive (1.28) |

| MCI-4 | F | 64 | MCI, amnestic w/other domains | positive (63.7) | positive (1.42) |

| MCI-5 | M | 82 | MCI, non-amnestic, focal | positive (101.0) | N/A |

| AD-1 | M | 73 | Probable AD, atypical presentation | positive (130.1) | positive (1.92) |

No [18F]SMBT-1 image data used, blood data only.

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; CL: centiloids; MCI: mild cognitive impairment.

Input function determination

Radio-HPLC plasma analyses revealed two major [18F]SMBT-1 radiometabolites. Under initial HPLC conditions (n = 8) measurement of the [18F]SMBT-1 unchanged fraction was confounded by co-elution of [18F]SMBT-1 and one of its radiometabolites, which were resolved in subsequent studies using refined separation methods. Analogous to [18F]THK5351, 53 the confounding [18F]SMBT-1 radiometabolite was identified as the product of O-sulfation (Supplementary Figure S1), which did not enter rodent brain or bind to recombinant MAO-B. 54

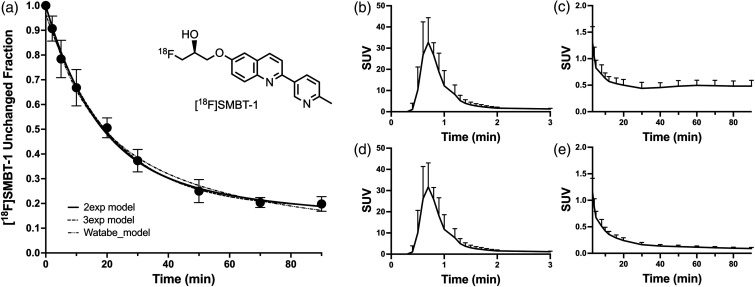

In order to conduct pharmacokinetic modeling studies of all 14 subjects, we computed the mean [18F]SMBT-1 unchanged fraction at each timepoint using data from later studies (n = 6) where [18F]SMBT-1 and its radiometabolites were resolved. The two-exponential, three-exponential, and Watabe models 31 fit the unchanged fraction data, which were best fit (lowest sum-of-squares) with a biexponential decay model:

with fast and slow half-times and of 12.0 min and 152.2 min, respectively, and a scale factor A equal to 0.722 (Figure 1(a)). The fit of the mean unchanged fraction measurements was interpolated to blood sample times for correcting total plasma radioactivity samples. The mean plasma radioactivity concentration reached a peak of 31.7 ± 11.3 SUV at 42 seconds after injection and declined rapidly to 10% of the peak value by ∼90 seconds (Figure 1(b) to (e)). The plasma free fraction (fp) was measured to be 9.4 ± 3.3% (n = 13) and could not be determined in one subject due to sample loss. However, as >50% of [18F]SMBT-1 radioactivity used in the protein binding assay was retained by the filter and sample tube, fp estimates may be unreliable.

Figure 1.

(a) Average (±1 SD) unchanged fraction of [18F]SMBT-1 for n = 6 subjects showing two exponential, three exponential, and Watabe model fits. (b) Averaged (+1 SD) total arterial plasma radioactivity of study subjects (n = 14) shown for the 0–3 min and (c) 3–90 min post-injection intervals. (d) Average (+1 SD) [18F]SMBT-1 metabolite-corrected arterial input function for the 0–3 min and (e) 3–90 min post-injection intervals.

Brain uptake and clearance

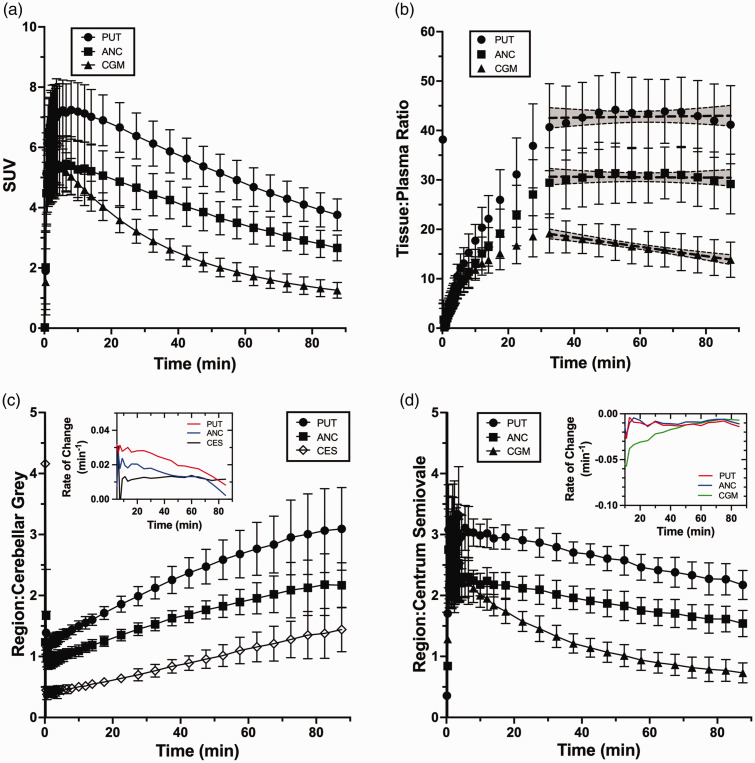

Rapid brain uptake following [18F]SMBT-1 injection was observed across subjects and grey matter regions, reaching peak values of 4–9 SUV between 1.5 and 7 min post-injection. Clearance of brain radioactivity was moderate, with peak:90 min radioactivity concentration ratios of ∼2 in high MAO-B regions (e.g., putamen) and ∼5 in low MAO-B regions (e.g., CGM; Figure 2(a)). Ratios of [18F]SMBT-1 tissue:plasma radioactivity concentrations reached a plateau by ∼35 min in intermediate (anterior cingulate) to high (putamen) MAO-B regions, as indicated by slopes that were not significantly non-zero, whereas low MAO-B regions (CGM) did not achieve tissue:plasma steady-state conditions (Figure 2(b)). Ratios of putamen:CGM radioactivity concentrations were ∼1.1 at scan start and initially increased rapidly at a rate of ∼0.03/min before slowing to a terminal rate of 0.008/min at a peak ratio of ∼3 (Figure 2(c)). CES:CGM ratios began near ∼0.5 and continuously increased at a rate of ∼0.012/min (Figure 2(c)). In contrast, target:CES ratios decreased at a constant rate of ∼ −0.01/min (Figure 2(d)). This phenomenon is likely explained by a slower rate of clearance from CES (peak:90 min ratio of ∼1.6) compared to target regions and CGM (peak:90 min ratio of ∼5), indicating that CES is not an ideal pseudo-reference region.

Figure 2.

(a) Average (±1 SD) [18F]SMBT-1 time-activity curves and (b) tissue:plasma ratios for n = 13 subjects in regions of interest that span the range of MAO-B expression in human brain. Shown are putamen (high MAO-B), anterior cingulate (intermediate MAO-B) and cerebellum (low MAO-B). Also shown are the best fit line and 95% confidence interval from linear regression of tissue plasma ratios over 30-90 min post-injection that demonstrate steady-state conditions for putamen and anterior cingulate. (c) Average (±1 SD) ratios of regional [18F]SMBT-1 brain radioactivity concentrations to cerebellar grey and (d) centrum semiovale pseudo-reference regions. Inset graphs show the absolute rate of change (min−1) in the ratios over time.

PET images showed the highest radioactivity retention in putamen, amygdala, thalamus, and caudate. Intermediate levels of retention characterized hippocampus, entorhinal, lateral temporal, anterior and posterior cingulate, precuneus, and fusiform regions. Low retention was observed in parietal and occipital lobe regions, cerebellar grey and white matter, and subcortical white matter. Increased [18F]SMBT-1 signal was observed in amyloid positive subjects in cortical regions associated with Aβ deposition, notably in frontal and parietal lobes (Supplementary Figure S2).

Kinetic analyses

Compartmental modeling

Compartmental modeling analyses showed a 1TC model to be inadequate for describing the kinetics of any region including CGM, which has the lowest MAO-B expression of regions examined. 8 In general, 2TC model configurations fit the data well when a fit blood delay parameter was included (Supplementary Figure S3). VT was well identified for all 2TC model configurations examined, as evidenced by low VT parameter error (∼2–3% relative standard error (RSE)) and comparable intersubject variability (∼15–20% coefficient of variation (%CV) across regions). Although the 2T5k model often showed the lowest AICc values, identifiability of vB, k2, k3, and k4 were relatively poor (Supplemental Table S2) and in 2 of 13 subjects the model failed to converge for some regions. Reducing the number of fit parameters by fixing vB to an accepted physiologic value (vB = 0.05) was associated with larger AICc values and increased parameter error for most regions (Supplementary Table S2). Based on observations that K1 and k2 were highly correlated in 2T5k and 2T4k model fits and thus not independently identifiable, we sought to improve the fit by initially configuring 2TC models with K1/k2 (VND) as a fit parameter (2T4kK1k2fit) and subsequently fixing K1/k2 to the fit value for an individual’s whole-brain (WB) time-activity curve (2T4kK1k2WB). This configuration was considered optimal based on improved parameter identifiability, low AICc values, and a reduction in outliers (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S4). In the subsequent text, unless otherwise indicated, 2TC model outcomes refer to the optimal 2T4kK1k2WB model configuration.

2TC kinetic model parameter estimates are shown in Table 2 for a subset of regions spanning the range of MAO-B expression in human brain. Across regions, VT and K1 were well identified with a RSE < 5%. VS was also identifiable (<10% RSE), whereas other 2TC parameters were not independently identifiable. We found no relationship between K1 and VT in 2TC model estimates (p > 0.3, data not shown), indicating that [18F]SMBT-1 VT is likely not flow limited.

Table 2.

Optimal 2TC Model (2T4kK1k2WB) Parameters (mean ± SD, n = 13).

| PUT | AMG | HIP | ERC | ITG | SMG | CGM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 (mL/min/cc) | 0.490 ± 0.092 | 0.321 ± 0.059 | 0.331 ± 0.064 | 0.282 ± 0.051 | 0.357 ± 0.075 | 0.375 ± 0.086 | 0.397 ± 0.067 |

| K1 RSE (%) | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

| k2 (min−1) a | 0.103 ± 0.026 | 0.067 ± 0.017 | 0.069 ± 0.017 | 0.059 ± 0.014 | 0.075 ± 0.019 | 0.078 ± 0.019 | 0.083 ± 0.019 |

| k3 (min−1) | 0.324 ± 0.101 | 0.193 ± 0.052 | 0.116 ± 0.038 | 0.117 ± 0.049 | 0.151 ± 0.069 | 0.115 ± 0.050 | 0.061 ± 0.037 |

| k3 RSE (%) | 11.2 ± 5.8 | 20.2 ± 7.9 | 10.4 ± 2.9 | 19.0 ± 6.5 | 7.9 ± 2.0 | 8.5 ± 4.5 | 7.8 ± 2.2 |

| k4 (min−1) | 0.092 ± 0.022 | 0.060 ± 0.020 | 0.048 ± 0.012 | 0.066 ± 0.026 | 0.093 ± 0.033 | 0.088 ± 0.029 | 0.073 ± 0.033 |

| k4 RSE (%) | 11.8 ± 5.8 | 24.2 ± 10.4 | 13.2 ± 4.2 | 23.4 ± 9.7 | 8.9 ± 2.9 | 9.5 ± 4.7 | 9.5 ± 3.1 |

| K1/k2 b | 4.93 ± 0.84 | 4.93 ± 0.84 | 4.93 ± 0.84 | 4.93 ± 0.84 | 4.93 ± 0.84 | 4.93 ± 0.84 | 4.93 ± 0.84 |

| k3/k4 | 3.53 ± 0.72 | 3.35 ± 0.82 | 2.37 ± 0.45 | 1.84 ± 0.56 | 1.63 ± 0.41 | 1.31 ± 0.33 | 0.80 ± 0.22 |

| k3/k4 RSE (%) | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 3.3 | 4.2 ± 1.8 | 6.6 ± 5.4 | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.6 |

| vB | 0.068 ± 0.021 | 0.056 ± 0.019 | 0.068 ± 0.014 | 0.064 ± 0.017 | 0.056 ± 0.015 | 0.066 ± 0.016 | 0.071 ± 0.016 |

| vB RSE (%) | 8.6 ± 2.3 | 15.4 ± 6.6 | 6.8 ± 1.9 | 9.2 ± 2.4 | 5.3 ± 1.6 | 4.4 ± 1.9 | 4.0 ± 1.4 |

| Delay (sec) | 9.58 ± 3.22 | 9.58 ± 3.21 | 9.58 ± 3.21 | 9.58 ± 3.21 | 9.58 ± 3.21 | 9.58 ± 3.21 | 9.58 ± 3.21 |

| VT | 22.09 ± 3.08 | 21.35 ± 5.3 | 16.49 ± 2.81 | 14.04 ± 4.09 | 12.96 ± 3.12 | 11.33 ± 2.30 | 8.80 ± 1.34 |

| VT RSE (%) | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 2.8 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 4.4 ± 4.3 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| VS | 17.16 ± 3.41 | 16.42 ± 4.80 | 11.57 ± 2.33 | 9.11 ± 3.57 | 8.04 ± 2.58 | 6.41 ± 1.81 | 3.87 ± 0.97 |

| VS RSE (%) | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 3.3 | 4.2 ± 1.8 | 6.6 ± 5.4 | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1.6 |

Calculated parameter.

Fixed to individual participant’s whole brain K1/k2 ratio.

AMG: amygdala; CGM: cerebellar grey matter; ERC: entorhinal cortex; HIP: hippocampus; ITG: inferior temporal gyrus; PUT: putamen; RSE: relative standard error; SMG: supramarginal gyrus.

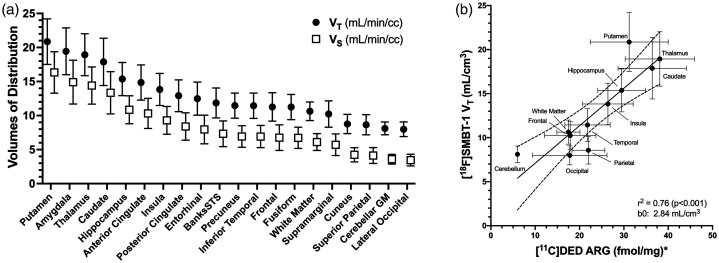

The rank order of mean [18F]SMBT-1 2TC VT values for the set of regions examined is shown in Figure 3(a). Here, only subjects with no demonstrable amyloid or tau pathology (n = 8) were included to depict the normal distribution of MAO-B without the potential influence of overlapping AD pathology. Putamen, amygdala, thalamus and caudate showed the highest mean VT values (VT ∼ 18–21). The majority of the remaining regions occupied an intermediate range (11 < VT < 16), whereas cuneus, superior parietal, CGM and lateral occipital showed low levels of binding (VT < ∼9). For these subjects the mean VT value for lateral occipital cortex (VT = 8.0) was slightly lower than CGM (VT = 8.1), but for the full sample CGM had the lowest mean VT. Regional [18F]SMBT-1 VT values showed strong agreement (r2 = 0.76, p < 0.001) with the reported brain distribution of MAO-B 8 (Figure 3(b)). Based on a fit whole brain VND averaging 4.93 ± 0.84, VS was estimated by the model to be 62.3% ± 9.7% of VT across regions (range: 44.0%–77.7%), suggesting that the majority of [18F]SMBT-1 signal is specifically bound.

Figure 3.

(a) Regional rank order of [18F]SMBT-1 total volume of distribution (VT) and specific volume of distribution (VS) for n = 8 Aβ negative subjects. (b) Correlation of in vivo [18F]SMBT-1 outcomes for Aβ negative subjects (n = 8) with post-mortem [11C]DED autoradiographic (ARG) determination of region MAO-B expression (fmol/mg, mean ± SD). *Data from Gulyás et al., 2011.

Reference region

Consistent with the observation of low but non-negligible levels of MAO-B expression in cerebellum and white matter,3,8 we found that the kinetics of all candidate reference regions (CGM, CWM, WCB, and CES) were not well described by a 1TC model. For AD pathology free subjects (n = 8), we found that 2TC VT estimates in CWM (10.20 ± 1.00) were 26% higher than CGM (8.11 ± 0.94), whereas VT was not well-identified in CES due to large errors in k3 and/or k4 parameter estimates. As such, we concluded that CGM was the preferred pseudo-reference region for approximating [18F]SMBT-1 VND, even though ∼60% of the CGM VT value could be attributed to specific binding (Table 2).

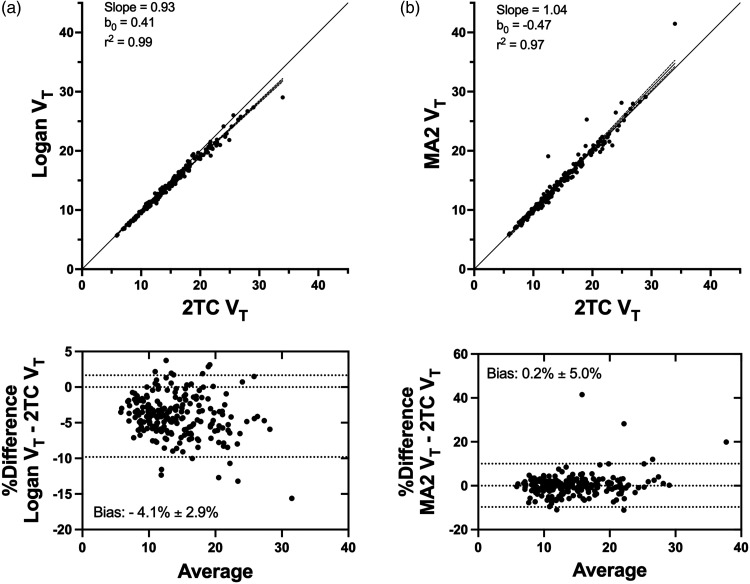

Non-compartmental models

The Logan plot yielded VT measures that were highly correlated with 2TC estimates (r2 = 0.99) with low bias (−4.1% ± 2.9%) (Figure 4(a)). The four-parameter multilinear analysis method, MA2, yielded VT values that were also highly correlated with 2TC model (r2 = 0.97) estimates with negligible (0.2% ± 5.0%) bias (Figure 4(b)). We found that MA2 performed better than MA1, which showed a level of bias comparable to the Logan plot (data not shown).

Figure 4.

(a) Comparing optimal two-tissue compartment (2TC) model (2T4kK1k2WB) total volume of distribution (VT) estimates with the Logan plot and (b) Ichise’s 4-parameter multilinear analysis (MA2) for all regions and subjects. Shown are the best fit line, the 95% confidence interval, and the line of identity. Bland-Altman plots show the Logan VT values to be on average ∼4% lower than 2TC VT values across all regions and subjects (n = 13), whereas MA2 VT values were essentially unbiased.

Reference tissue methods

Some bias was expected in reference tissue analysis outcomes due to factors that include displaceable binding in the reference tissue and violations of the assumed model topology (e.g., 1TC reference region kinetics).43,55 Nevertheless, all reference tissue methods yielded outcomes (either DVR or BPND) that were highly correlated with analogous 2TC-derived outcomes (r2 > 0.95) with low to moderate bias (Supplementary Figure S4).

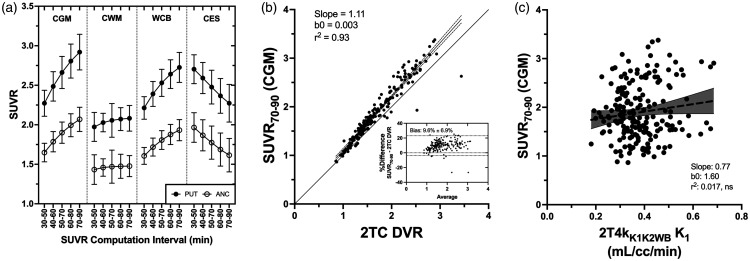

Tissue ratio methods

Varying the time interval of computation and the normalizing region, we found that SUVR values normalized to CGM and WCB did not completely plateau by the latest summation interval (70–90 min), whereas CWM-normalized SUVR values were more stable albeit at a lower ratio (Figure 5(a)). This observation reflects small but positive changes in tissue:CGM ratios over this interval (Figure 2). SUVR values normalized to CES decreased continuously with increasing time. Relative to 2TC DVR, SUVR70–90 outcomes were more biased using CWM (−24.0%) or CES (−15.6%) as a normalizing region then either CGM (9.6%) or WCB (2.8%). CGM-normalized SUVR70–90 outcomes showed good agreement with 2TC DVR values (r2 = 0.93) and acceptable bias (9.6%) (Figure 5(b)). We also found that SUVR70–90 (CGM) outcomes were not significantly influenced by radiotracer delivery, showing no significant relationship with 2TC K1 (Figure 5(c)). WCB-normalized SUVR values also showed good agreement with 2TC DVR with low bias (Supplementary Table S3), but due to the increased VT of [18F]SMBT-1 in cerebellar white matter, which presumably reflects higher constitutive MAO-B expression, we favored CGM as a reference region for SUVR computation.

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of post-injection computation interval and selection of normalizing region on the calculation of [18F]SMBT-1 SUVR for regions with high (putamen) and low (sensorimotor cortex) MAO-B expression. Shown are mean SUVR values for five summation intervals and four normalizing regions: cerebellar grey matter (CGM), cerebellar white matter (CWM), whole cerebellum (WCB), and centrum semiovale (CES). (b) Comparing 2TC-derived distribution volume ratio (DVR) and SUVR70–90 outcomes normalized to cerebellar grey matter (CGM) for all regions and subjects. Inset Bland-Altman plot shows SUVR to have a bias of ∼10% relative to the 2TC DVR and (c) SUVR70–90 outcomes showed no significant relationship with 2TC K1 values, indicating that SUVR is not biased by radiotracer delivery.

Discussion

The present work describes the pharmacokinetic modeling of [18F]SMBT-1 as a PET radiotracer for indexing brain MAO-B density and characterizes simplified imaging methodologies more practical for studies in clinical research populations. Consistent with earlier studies, 28 we found [18F]SMBT-1 to readily enter brain and show increased retention in high MAO-B brain regions (Figure 2(a)) consistent with its known regional distribution (Figure 3(b) and Supplementary Figure S2).

Pharmacokinetic modeling of [18F]SMBT-1 revealed that a 2TC model that included a blood delay parameter and a K1/k2 constraint fixed to a whole brain value best fit regional TAC data across tissues spanning the range of MAO-B expression. With this model configuration, VT was well identified (RSE < 5%) with a between-subject coefficient of variation (%CV) of 20.4% ± 3.4% averaged across all subjects and regions. The rapid rise time of the [18F]SMBT-1 tissue response likely explains the need for a blood delay parameter to satisfactorily fit the data. Although the K1/k2 constraint generally improved parameter identifiability, we found VT to be comparably well identified (RSE < 5% across regions) for all 2TC configurations.

To demonstrate MAO-B selectivity, earlier studies showed profound reductions (∼85%) in [18F]SMBT-1 uptake across regions after selegiline pretreatment. 28 Accurate estimates of the non-displaceable volume VND in a non-target reference region (i.e., VS = 0) are required for specific binding estimates in target-rich tissues, which is not possible given the ubiquitous brain distribution of MAO-B. Consistent with the presence of low but non-negligible levels of MAO-B expression in cerebellum and white matter shown by post-mortem studies,3,8 and earlier in vivo [18F]SMBT-1 human studies showing large reductions in cerebellar grey, cerebellar white and subcortical white matter SUV following selegiline pretreatment, we found that the kinetics of all candidate [18F]SMBT-1 reference regions were not well described by a 1TC model. In instances where no true reference region exists, an alternative strategy for measuring VND is to pre-administer pharmacologic doses of an unlabeled competitor (e.g., selegiline) to occupy binding sites and block radiotracer specific binding. 56 In lieu of direct measurement, VND can be derived from 2TC model rate constants (VND = K1/k2) or from total and specific volume estimates (VND = VT–VS) provided these parameters are well identified. In the present study, we observed that regional K1/k2 ratios estimated using the 2T4k model configuration were significantly correlated with the VT value (r2 = 0.32, p < 0.0001). Further, parameter sensitivity studies showed that k2 was not independent of either K1 or k3 (data not shown). As the individual rate constants were not independently identifiable, it is possible that macroparameters such as VND and VS may be well identified but not reflect physiologically meaningful quantities. For this reason, we recommend VT as the preferred [18F]SMBT-1 outcome measure.

Based on the magnitude of the reductions of regional [18F]SMBT-1 SUV values reported for previous selegiline blocking experiments, which is assumed to indicate the specific binding fraction, we predicted VND would range from ∼5% of VT in the highest MAO-B regions to ∼40% of VT in low MAO-B regions. 28 In the present work, we found that a whole brain estimate of VND averaged 4.93 ± 0.8 mL/cm3 (range: 3.5–6.2 mL/cm3) across subjects, a value representing 22% (putamen) to 56% (CGM) of VT. The y-intercept of the fit line from the regression of [18F]SMBT-1 VT values and [11C]DED autoradiographic measures of regional MAO-B concentrations (fmol/mg) from post-mortem brain tissue (Figure 3(b)) suggests a somewhat lower VND of 2.8 mL/cm3 than estimated by fitting K1/k2 from a whole brain TAC, although both are within the 95% confidence interval of the fit (−1.74–7.42 mL/cm3). In any case, both VND estimates suggest a larger non-displaceable compartment than predicted by selegiline blocking. Considering the 92% reduction in putamen SUV observed after selegiline pretreatment 28 and our finding of a mean putamen VT of 22.09 mL/cm3 (Table 2), a VND of only ∼1.8 mL/cm3 would represent a 92% reduction in VT post-selegiline. This discrepancy may be explained by the insensitivity of SUV outcomes to alterations in radiotracer delivery parameters, non-specific binding, peripheral metabolism, or plasma protein binding pre- and post-selegiline, and therefore SUV may overestimate the response to selegiline. Nevertheless, our data suggests that a large fraction of [18F]SMBT-1 VT is attributable to specific binding and supports its use as an index of brain MAO-B expression. Additional fully quantitative studies of [18F]SMBT-1 kinetics following selegiline pretreatment are necessary to fully understand the influence of MAO-B expression on reference region kinetics and accurately assess VND.

The fully-quantitative [18F]SMBT-1 imaging experiments reported in this work provided a benchmark (the 2TC VT) to compare simplified methods. Graphical analysis methods estimate VT directly and are conducive to parametric image generation. Both Logan and MA2 VT estimates were highly correlated with 2TC VT outcomes showing low to negligible bias (Figure 4). Regions with high MAO-B expression exhibit slower kinetics and therefore impose a later t* than low MAO-B regions for a given error criterion, as a more stringent one could leave too few points to perform linear regression. In MA1 and the Logan plot the selection of t* based on an error criterion of 10% may therefore underestimate VT in high MAO-B regions due to fitting before the true point of linearity, whereas MA2 has the advantage of using all tissue data for times t > 0. TAC noise may also be a potential source of bias in Logan plot outcomes.

The use of a pseudo-reference tissue with a displaceable binding compartment in reference tissue analyses yields outcomes vulnerable to bias. 43 In the present work we estimated the mean [18F]SMBT-1 VND to be ∼5 mL/cm3, a value that is ∼60% of the mean CGM VT value of 8.1 mL/cm3 in AD pathology-free subjects (n = 8), suggesting that ∼40% of [18F]SMBT-1 binding in CGM is displaceable. Nevertheless, we found that using CGM in reference tissue analyses yielded outcomes in good agreement (r2 > 0.85) with corresponding 2TC model outcomes (e.g., DVR or BPND) with low to moderate bias (Supplementary Figure S4). SRTM failed to converge in some instances where target region specific binding was lower than CGM, whereas linear methods like rLP, MRTM and MRTM2 yielded negative BPND values or DVR estimates less than 1. As such, reference tissue methods may not provide reliable specific binding estimates in low MAO-B regions that overlap with CGM. Although the reference tissue outcomes examined compared favorably to 2TC outcomes, it is important to note that the outcomes of any analysis methodology relying upon reference tissue quantification, including SUVR, are inherently sensitive to changes in the reference tissue between comparison populations, treatment conditions, or serial observations and should be used cautiously without prior validation. Although the present study has limited statistical power to characterize group differences in [18F]SMBT-1 specific binding, we observed significant (p < 0.05) 2TC VT increases in Aβ-positive (n = 5) relative to Aβ-negative (n = 8) subjects in several brain regions, including CWM, cuneus, lateral occipital, superior parietal, and cerebral white matter, that remained significant after FDR correction (Supplementary Figure S5). Comparison of SUVR70–90 outcomes between Aβ-positive and Aβ-negative subjects showed only lateral occipital to be significantly different after FDR correction (Supplementary Figure S5). It will remain the object of future studies with greater statistical power to fully examine relationships between indices of AD pathology and [18F]SMBT-1 binding indices, including pseudo-reference region changes.

SUVR methods are favored for their many practical advantages, such as an abbreviated scan protocol, no blood sampling, and computational simplicity. Previous studies have shown that [18F]SMBT-1 SUVR values normalized to subcortical white matter predict the in vitro distribution of MAO-B, 28 and the present work shows that CGM-normalized SUVR70–90 outcomes are strongly correlated with 2TC DVR with low bias and insensitive to radiotracer delivery (Figure 5). SUVR values normalized to CGM and to a lesser extent WCB showed a positive bias compared to 2TC DVR (Supplementary Table S3), which may be due to slower clearance in MAO-B rich tissues and incomplete stabilization of tissue:CGM ratios (Figure 2(c)). The use of earlier intervals for SUVR computation, or other normalizing tissues yields increased bias (Supplementary Table S3), likely due to the lack of steady-state conditions between high MAO-B target regions and pseudo-reference tissues (Figure 2).

The present study extends earlier [18F]SMBT-1 first-in-human studies 28 by providing full pharmacokinetic analyses with metabolite-corrected arterial input functions. Our findings support the application of CGM-normalized SUVR70–90 methods to [18F]SMBT-1 data, which are possible using an abbreviated imaging protocol that is practical and well-tolerated. Alternatives, such as graphical analysis methods (e.g. Logan plot, MA2) that estimate VT directly, perform well and are conducive to parametric image generation, but maintain the requirements of arterial blood sampling and 90-min dynamic PET data acquisition. Reference tissue methods directly estimating [18F]SMBT-1 BPND also compare favorably to BPND estimates derived from 2TC VT outcomes and are also conducive to parametric image generation, although with increased bias and/or potential challenges estimating BPND in low MAO-B regions. This may be an acceptable tradeoff that obviates arterial blood sampling, although their application still requires 90 min of dynamic data acquisition.

A limitation of the present study is the lack of test-retest reliability assessments of [18F]SMBT-1 outcomes, an important criterion for sample size and statistical power calculations that could further inform the selection of an optimal [18F]SMBT-1 analysis method. Another limitation was our inability to separate unmetabolized [18F]SMBT-1 from its sulfoconjugate radiometabolite in a majority of subjects (n = 8), which required the determination of an average metabolite correction from n = 6 subjects to correct for radiolabeled metabolites in all subjects. Because of individual differences in metabolism, an average correction may be a source of error in input-function driven outcomes. However, we observed no significant differences (p > 0.5) between 2TC VT values determined using individual data from participants where we were able to resolve [18F]SMBT-1 and its radiometabolites (n = 6) and using an average metabolite correction derived from these same subjects (Supplementary Figure S6). Consistent [18F]SMBT-1 metabolism across subjects (Figure 1) suggests that an average metabolite correction may offset the measurement variability characteristic of individual data, and a population metabolite correction may represent an additional methodologic simplification supporting image-derived input functions. Future studies will explore alternative analysis strategies that do not rely on reference region assumptions, such as the derivation of a population-based input function for estimating VT or late-scan tissue-to-plasma ratios, 57 to characterize potential changes in [18F]SMBT-1 binding attributable to a global astroglial response to neurodegenerative disease pathology.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X241254679 for Kinetic modeling of the monoamine oxidase-B radioligand [18F]SMBT-1 in human brain with positron emission tomography by Brian J Lopresti, Jeffrey Stehouwer, Alexandria C Reese, Neale S Mason, Sarah K Royse, Rajesh Narendran, Charles M Laymon, Oscar L Lopez, Ann D Cohen, Chester A Mathis and Victor L Villemagne in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ryuichi Harada and colleagues at Tohoku University, Japan, for their assistance with radiometabolite identification and assay conditions.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Aging (P01 AG025204).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: Brian J. Lopresti: study concept and design, overall responsibility for data analyses, acquisition and interpretation, prepared manuscript.

Jeffrey Stehouwer: data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, [18F]SMBT-1 radiosynthetic methods and metabolite analyses.

Alexandria C. Reese: data analyses.

Neale S. Mason: data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, [18F]SMBT-1 radiosynthetic methods and metabolite analyses.

Sarah K. Royse: data analyses, critical revision of manuscript.

Rajesh Narendran: critical revision of manuscript.

Charles M. Laymon: data acquisition

Oscar L. Lopez: study concept and design

Ann D. Cohen: study concept and design

Chester A. Mathis: critical revision of manuscript

Victor L. Villemagne: study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of manuscript.

Supplementary material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD: Jeffrey Stehouwer https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8871-2544

References

- 1.Shih JC, Chen K, Ridd MJ. Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci 1999; 22: 197–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tipton KF. The sub-mitochondrial localization of monoamine oxidase in rat liver and brain. Biochim Biophys Acta 1967; 135: 910–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong J, Meyer JH, Furukawa Y, et al. Distribution of monoamine oxidase proteins in human brain: implications for brain imaging studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 863–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler CJ, Wiberg A, Oreland L, et al. The effect of age on the activity and molecular properties of human brain monoamine oxidase. J Neural Transm 1980; 49: 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekblom J, Jossan SS, Bergström M, et al. Monoamine oxidase-B in astrocytes. Glia 1993; 8: 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acioglu C, Li L, Elkabes S. Contribution of astrocytes to neuropathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res 2021; 1758: 147291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar A, Fontana IC, Nordberg A. Reactive astrogliosis: a friend or foe in the pathogenesis of alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 2023; 164: 309–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulyás B, Pavlova E, Kása P, et al. Activated MAO-B in the brain of Alzheimer patients, demonstrated by [11C]-L-deprenyl using whole hemisphere autoradiography. Neurochem Int 2011; 58: 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saura J, Luque JM, Cesura AM, et al. Increased monoamine oxidase B activity in plaque-associated astrocytes of Alzheimer brains revealed by quantitative enzyme radioautography. Neuroscience 1994; 62: 15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovacs GG, Xie SX, Robinson JL, et al. Sequential stages and distribution patterns of aging-related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG) in the human brain. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2018; 6: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amador-Ortiz C, Ahmed Z, Zehr C, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis dementia differs from hippocampal sclerosis in frontal lobe degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 2007; 113: 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radford RA, Morsch M, Rayner SL, et al. The established and emerging roles of astrocytes and microglia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Front Cell Neurosci 2015; 9: 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engler H, Nennesmo I, Kumlien E, et al. Imaging astrocytosis with PET in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: case report with histopathological findings. Int J Clin Exp Med 2012; 5: 201–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Booth HDE, Hirst WD, Wade-Martins R. The role of astrocyte dysfunction in Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Trends Neurosci 2017; 40: 358–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler JS, MacGregor RR, Wolf AP, et al. Mapping human brain monoamine oxidase a and B with 11C-labeled suicide inactivators and PET. Science 1987; 235: 481–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Logan J, et al. Selective reduction of radiotracer trapping by deuterium substitution: comparison of carbon-11-L-deprenyl and carbon-11-deprenyl-D2 for MAO B mapping. J Nucl Med 1995; 36: 1255–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santillo AF, Gambini JP, Lannfelt L, et al. In vivo imaging of astrocytosis in Alzheimer's disease: an 11C-L-deuteriodeprenyl and PIB PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011; 38: 2202–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter SF, Chiotis K, Nordberg A, et al. Longitudinal association between astrocyte function and glucose metabolism in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2019; 46: 348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter SF, Schöll M, Almkvist O, et al. Evidence for astrocytosis in prodromal Alzheimer disease provided by 11C-deuterium-L-deprenyl: a multitracer PET paradigm combining 11C-Pittsburgh compound B and 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med 2012; 53: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds GP, Elsworth JD, Blau K, et al. Deprenyl is metabolized to methamphetamine and amphetamine in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1978; 6: 542–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saba W, Valette H, Peyronneau MA, et al. [(11)C]SL25.1188, a new reversible radioligand to study the monoamine oxidase type B with PET: preclinical characterisation in nonhuman primate. Synapse 2010; 64: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusjan PM, Wilson AA, Miler L, et al. Kinetic modeling of the monoamine oxidase B radioligand [11C]SL25.1188 in human brain with high-resolution positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 883–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng KP, Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, et al. Monoamine oxidase B inhibitor, selegiline, reduces (18)F-THK5351 uptake in the human brain. Alzheimers Res Ther 2017; 9: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishibashi K, Miura Y, Hirata K, et al. 18F-THK5351 PET can identify astrogliosis in multiple sclerosis plaques. Clin Nucl Med 2020; 45: e98–e100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tago T, Toyohara J, Sengoku R, et al. Monoamine oxidase B binding of 18F-THK5351 to visualize glioblastoma and associated gliosis: an Autopsy-Confirmed case. Clin Nucl Med 2019; 44: 507–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takami Y, Yamamoto Y, Norikane T, et al. 18F-THK5351 PET can identify lesions of acute traumatic brain injury. Clin Nucl Med 2020; 45: e491–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harada R, Hayakawa Y, Ezura M, et al. (18)F-SMBT-1: a selective and reversible PET tracer for monoamine oxidase-B imaging. J Nucl Med 2021; 62: 253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villemagne VL, Harada R, Doré V, et al. First-in-humans evaluation of (18)F-SMBT-1, a novel (18)F-labeled monoamine oxidase-B PET tracer for imaging reactive astrogliosis. J Nucl Med 2022; 63: 1551–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandelman MS, Baldwin RM, Zoghbi SS, et al. Evaluation of ultrafiltration for the free-fraction determination of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) radiotracers: beta-CIT, IBF, and iomazenil. J Pharm Sci 1994; 83: 1014–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Somvanshi PR, andVenkatesh KV, et al. Hill equation. In: Dubitzky W, Wolkenhauer O, Cho K-H, (eds) Encyclopedia of systems biology. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2013, pp. 892–895. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watabe H, Channing MA, Der MG, et al. Kinetic analysis of the 5-HT2A ligand [11C]MDL 100,907. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000; 20: 899–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakoby BW, Bercier Y, Conti M, et al. Physical and clinical performance of the mCT time-of-flight PET/CT scanner. Phys Med Biol 2011; 56: 2375–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snitz BE, Tudorascu DL, Yu Z, et al. Associations between NIH toolbox cognition battery and in vivo brain amyloid and tau pathology in non-demented older adults. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2020; 12: e12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bourgeat P, Doré V, Fripp J, AIBL research group et al. Implementing the centiloid transformation for (11)C-PiB and β-amyloid (18)F-PET tracers using CapAIBL. Neuroimage 2018; 183: 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan KJ, Liu A, Chang CH, et al. Alzheimer's disease pathology in a community-based sample of older adults without dementia: the MYHAT neuroimaging study. Brain Imaging Behav 2021; 15: 1355–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gogola A, Lopresti BJ, Tudorascu D, et al. Biostatistical estimation of tau threshold hallmarks (BETTH) algorithm for human tau PET imaging studies. J Nucl Med 2023; 64: 1798–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Initiative AsDN. ADNI-3 Procedure Manuals, https://adni.loni.usc.edu/adni-3/procedure-manuals/ (2017, accessed 21 September 2023).

- 38.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007; 27: 1533–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saura J, Bleuel Z, Ulrich J, et al. Molecular neuroanatomy of human monoamine oxidases A and B revealed by quantitative enzyme radioautography and in situ hybridization histochemistry. Neuroscience 1996; 70: 755–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leenders KL, Perani D, Lammertsma AA, et al. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen utilization. Normal values and effect of age. Brain 1990; 113 (Pt 1): 27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, et al. Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl]-(-)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1990; 10: 740–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ichise M, Toyama H, Innis RB, et al. Strategies to improve neuroreceptor parameter estimation by linear regression analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2002; 22: 1271–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salinas CA, Searle GE, Gunn RN. The simplified reference tissue model: model assumption violations and their impact on binding potential. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, et al. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1996; 16: 834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichise M, Liow JS, Lu JQ, et al. Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2003; 23: 1096–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage 1996; 4: 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lopresti BJ, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, et al. Simplified quantification of Pittsburgh compound B amyloid imaging PET studies: a comparative analysis. J Nucl Med 2005; 46: 1959–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shcherbinin S, Schwarz AJ, Joshi A, et al. Kinetics of the tau PET tracer 18F-AV-1451 (T807) in subjects with normal cognitive function, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer disease. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 1535–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pascoal TA, Shin M, Kang MS, et al. In vivo quantification of neurofibrillary tangles with [(18)F]MK-6240. Alzheimers Res Ther 2018; 10: 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr 1974; 19: 716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugiura N. Further analysis of the data by Akaike's information criterion and the finite corrections. Commun Stat – Theory Methods 1978; 7: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol) 1995; 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harada R, Furumoto S, Tago T, et al. Characterization of the radiolabeled metabolite of tau PET tracer (18)F-THK5351. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016; 43: 2211–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harada R, Shimizu Y, Du Y, et al. The role of chirality of [(18)F]SMBT-1 in imaging of monoamine oxidase-B. ACS Chem Neurosci 2022; 13: 322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parsey RV, Slifstein M, Hwang DR, et al. Validation and reproducibility of measurement of 5-HT1A receptor parameters with [carbonyl-11C]WAY-100635 in humans: comparison of arterial and reference tissue input functions. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000; 20: 1111–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cunningham VJ, Rabiner EA, Slifstein M, et al. Measuring drug occupancy in the absence of a reference region: the Lassen plot re-visited. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30: 46–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buchert R, Dirks M, Schütze C, et al. Reliable quantification of (18)F-GE-180 PET neuroinflammation studies using an individually scaled population-based input function or late tissue-to-blood ratio. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2020; 47: 2887–2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X241254679 for Kinetic modeling of the monoamine oxidase-B radioligand [18F]SMBT-1 in human brain with positron emission tomography by Brian J Lopresti, Jeffrey Stehouwer, Alexandria C Reese, Neale S Mason, Sarah K Royse, Rajesh Narendran, Charles M Laymon, Oscar L Lopez, Ann D Cohen, Chester A Mathis and Victor L Villemagne in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism