Abstract

Inherited Retinal Dystrophies (IRD) are diverse rare diseases that affect the retina and lead to visual impairment or blindness. Research in this field is ongoing, with over 60 EU orphan medicinal products designated in this therapeutic area by the Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) at the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Up to now, COMP has used traditional disease terms, like retinitis pigmentosa, for orphan designation regardless of the product's mechanism of action. The COMP reviewed the designation approach for IRDs taking into account all previous Orphan Designations (OD) experience in IRDs, the most relevant up to date scientific literature and input from patients and clinical experts. Following the review, the COMP decided that there should be three options available for orphan designation concerning the condition: i) an amended set of OD groups for therapies that might be used in a broad spectrum of conditions, ii) a gene-specific designation for targeted therapies, and iii) an occasional term for products that do not fit in the above two categories. The change in the approach to orphan designation in IRDs caters for different scenarios to allow an optimum approach for future OD applications including the option of a gene-specific designation. By applying this new approach, the COMP increases the regulatory clarity, efficiency, and predictability for sponsors, aligns EU regulatory tools with the latest scientific and medical developments in the field of IRDs, and ensures that all potentially treatable patients will be included in the scope of an OD.

Keywords: Rare diseases, orphan designation, EU regulators, medicines development, gene therapy, inherited retinal dystrophy

What is already known about this subject?

The Orphan framework provides incentives for medicines development in rare diseases in the EU with published general guidance1–3 for medicines developers on the criteria for “Orphan Designation”. How the condition is described is pivotal to the Orphan Designation (OD) application as the prevalence of the condition in the EU must not be more than 5 in 10,000.

EU regulators recognized there was a particular scientific and regulatory challenge with OD in inherited retinal dystrophies (IRD) - which was how to define the condition itself. The problem stems from the clinical and genetic heterogeneity within this disease group, and the use of a traditional classification (based on clinical appearance), which may not optimally define the population potentially benefitting from medicinal products with a gene-targeted mechanism of action. Therefore, this issue needed to be further addressed.

What this study adds?

Based on 1) a review of IRD Orphan Designations (OD) experience of in the European Union, 2) a review of scientific literature and clinical practice on IRD groupings and 3) input from patients and clinical experts, EU regulators make recommendations4,5 to guide choice of grouping for IRD conditions in the context of an EU OD.

These recommendations provide more clarity for medicines developers, open the possibility for designation of gene-specific conditions which reflects the evolving scientific understanding of disease aetiology for IRDs, bridge the gap with existing EU regulatory pathways such as Marketing authorisation, and will ensure that all potentially treatable patients are included in a European Union OD.

Introduction

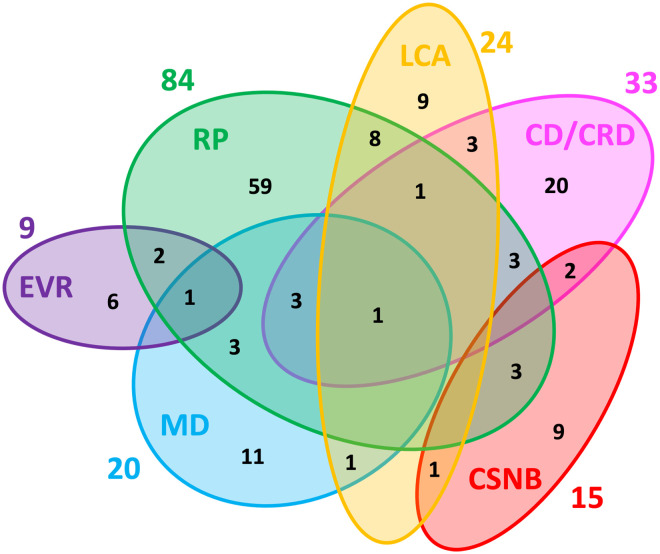

Inherited retinal dystrophies (IRD) are a group of rare diseases affecting retinal structure and function. Traditional disease names (e.g. retinitis pigmentosa (RP), Leber's congenital amaurosis (LCA), etc.) were driven by clinical features. Recently, the understanding of the genetic aetiology of IRD has increased and remains very complex. Many different single gene mutations can cause common clinical features. However, one single gene mutation can also be manifested in a variety of clinical features.6–16 See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Genetic heterogeneity among the six major non-syndromic inherited retinal diseases (IRD). Numbers outside of the ellipses correspond to the number of non-syndromic IRD genes responsible for the specific disease, while numbers within the ellipses correspond either to disease-specific genes or to genes mutated in two or more diseases. The non-redundant total of genes associated with these non-syndromic IRD is 146. RP: retinitis pigmentosa; LCA: Leber congenital amaurosis; CD/CRD: cone dystrophy/cone-rod dystrophy; CSNB: congenital stationary night blindness; MD: macular dystrophy; EVR: exudative vitreoretinopathy. Reproduced unchanged with permission of authors Cremers FPM, Boon CJF, Bujakowska K, et al. 7 © 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

The Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) is the European Medicines Agency's (EMA) committee responsible for recommending Orphan Designation (OD) of medicines for rare diseases. Receiving an EU OD, allows an innovator to access EU incentives for development of medicines of rare diseases. To be granted an OD, all relevant criteria must be satisfied.1–3 An essential part of the OD criteria (the prevalence) depends on the disease or condition for which the designation is requested. To be considered for OD, the prevalence of the condition in the EU must not be more than 5/10000.

Given the developments in understanding and treatment of IRD, it was important to review the best terminology for OD in this therapeutic area. This is because OD based on a phenotype-derived naming scheme may leave otherwise treatable patients without an effective treatment. For example, mutations in the RPE65 [retinoid isomerohydrolase RPE65] gene are associated with autosomal recessive RP and autosomal dominant RP with choroidal involvement, but also LCA. Therefore, an OD of RP would leave some potentially treatable patients, such as for example those suffering from LCA, out of scope of a gene-specific treatment targeted at RPE65. This is a consequence of the requirement that the therapeutic indication for a licensed medicinal product cannot be broader than the given OD, as imposed by article 7 of REGULATION (EC) No 141/2000. 3 Furthermore, associated clinical terms have been considered as overlapping, poorly defined and unreliable. 17 It was also relevant to consider the OD policy noting the EU approval of a targeted gene augmentation therapy (voretigene neparvovec, Luxturna®). Therefore, the COMP undertook a review to ascertain the state of the art in IRD to assess what would be the best approach or set of disease terms to use as the ‘condition’ for orphan designation in this therapeutic setting. This review was based on scientific literature, the experience of active EU OD in the therapeutic area of IRD, and a consultation of IRD clinical experts and patients. Finally, the COMP weighed the pros and cons of different possible approaches before making its recommendation.

Review of OD conditions

In order to review the experience of OD in the EU, COMP was presented with all active OD cases in the EU in IRD, the range of therapeutic targets and the final granted OD. To do this, JM searched the EMA orphan IRIS database for text strings based on traditional disease terms or syndromes within IRD. Records were reconciled with Orphanet 18 (Consortium database aggregating data from different sources), and with the publicly available Community Register of Orphan Medicinal Products (the EU listing of products granted OD in the EU).

Sixty-four cases of active EU OD were identified, with 57 unique active substances (See Table 1). Of these, 36 out of 64 OD (56%) were for gene therapies targeting single gene mutations. Four additional OD were for gene therapies taking a broader therapeutic approach. Four OD were for cell therapies, and one was a non-viral vector plasmid product. The remaining 28 products with OD had a more general mode of action applicable to many IRDs. Of the 36 targeted gene therapies, there were 20 unique gene targets (See Table 2). See Supplementary information 1 for the full EU OD listing in IRD active at the time of review. There was some heterogeneity in the OD condition granted by COMP for targeted gene therapies; six of the 36 gene therapies targeting single genes or specific mutations (sequence variants) received a gene specific OD e.g., “Treatment of RDH12 mutation-associated retinal dystrophy”, whereas the remainder received a classical term such as “Treatment of retinitis pigmentosa”, or a hybrid approach such as “Treatment of retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in the RPGR gene”. [RDH12; Retinol Dehydrogenase 12, RPGR; RGPR Retinitis Pigmentosa GTPase regulator].

Table 1.

Frequency of active granted ODs with agreed orphan conditions in the area of IRDs.*

| OD | Count |

|---|---|

| Treatment of achromatopsia | 1 |

| Treatment of achromatopsia caused by mutations in the CNGA3 gene | 2 |

| Treatment of achromatopsia caused by mutations in the CNGB3 gene | 2 |

| Treatment of Alström syndrome | 1 |

| Treatment of Bardet-Biedl syndrome | 1 |

| Treatment of choroideremia | 3 |

| Treatment of cone-rod dystrophy | 1 |

| Treatment of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy | 1 |

| Treatment of inherited retinal dystrophies | 2 |

| Treatment of inherited retinal dystrophies (initially named treatment of Leber's congenital amaurosis) | 1 |

| Treatment of inherited retinal dystrophies (initially named treatment of retinitis pigmentosa) | 1 |

| Treatment of Leber's congenital amaurosis | 9 |

| Treatment of RDH12 mutation associated retinal dystrophy | 1 |

| Treatment of retinitis pigmentosa | 26 |

| Treatment of retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in the RPGR gene | 1 |

| Treatment of retinitis pigmentosa in Usher syndrome 1B | 1 |

| Treatment of Stargardt's disease | 9 |

| Treatment of Usher Syndrome | 1 |

| Total | 64 |

*Note these are (historic) orphan designated conditions during medicine development, NOT therapeutic indications granted at the time a medicine receives a marketing authorisation. The Orphan legislation foresees giving Orphan Designation for substances that could be used for treating, preventing, or diagnosing a rare and serious condition. The Therapeutic Indication defines the target disease or condition for which the product is licensed based on the assessment of the marketing authorisation application including all the evidence of efficacy and safety. The orphan condition during development needs to define a distinct medical condition, but with a broad enough scope that there would be no risk that the therapeutic indications to be granted at the time of marketing authorisation would suddenly exceed or fall out of the scope of the orphan condition.

OD: Orphan Designation; CNGA: Cyclic Nucleotide Gated Channel Subunit Alpha;

CNGB: Cyclic Nucleotide Gated Channel Subunit Beta;

IRD: Inherited Retinal Dystrophy;

RDH: Retinol Dehydrogenase;

RGPR: Retinitis Pigmentosa GTPase Regulator.

Table 2.

Specific gene targets in IRD orphan designations.

| Gene targeted | Count |

|---|---|

| ABCA4 | 3 |

| AIPL1 | 1 |

| CEP290 | 1 |

| CEP290intron26 | 2 |

| CHM/ REP1 | 3 |

| CNGA3 | 3 |

| CNGB3 | 2 |

| CRX | 2 |

| GUCY2D | 1 |

| MYO7A | 2 |

| PDE6A | 1 |

| PDE6ß | 1 |

| RDH12 | 1 |

| RHO | 1 |

| RLBP1 | 1 |

| RPE65 | 5 |

| RPGR | 3 |

| USH2A | 1 |

| USH2A exon13 | 2 |

| Total | 36 |

ABCA: ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily A;

AIPL: Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Interacting Protein Like;

CEP: Centrosomal Protein;

CHM/ REP1: Choroideremia / Rab escort Protein;

CNGA3: Cyclic Nucleotide Gated Channel Subunit Alpha;

CNGB3: CNGB (Cyclic Nucleotide Gated Channel Subunit Beta;

CRX: human Cone-Rod Homeobox;

GUCY: Guanylate Cyclase;

MYO7: Myosin VII;

PDE: Phosphodiesterase;

PDE: Phosphodiesterase;

RDH: Retinol Dehydrogenase;

RHO: Rhodopsin;

RLBP: Retinaldehyde-Binding Protein;

RPE: Retinoid Isomerohydrolase retinal pigment epithelium;

RPGR: RGPR Retinitis Pigmentosa GTPase Regulator;

USH: Usherin.

The data highlight the high proportion of gene therapies amongst products granted an OD in the EU in IRD. Amongst the gene therapies, a variable OD approach was apparent with a mixture of some gene-specific and traditional disease terms used, highlighting the need for a standardised approach.

Policy development and relevant recent scientific literature

As part of preliminary considerations, COMP had identified two possible approaches to updating the OD policy in IRD, i.e. either continuing with a broad approach using an accepted clinical classification scheme for IRDs, or pursuing a gene-specific approach to the conditions. Therefore, JM searched the scientific literature to identify possible classifications for IRDs that might be considered useful for OD. Initial literature searches were conducted in PubMed for relevant articles and expanded with citations searching and with expert consultation.

The findings of the literature review were presented to the COMP, with the most pertinent classifications considered (Table 3). A recent clinical classification by Sergouniotis 2019, 19 which is reflected also in the ophthalmology- component of the Orphanet Rare Disease Ontology (ORDO) 18 and was derived via the European Reference Network for rare eye diseases (ERN-EYE) Ontology meeting, was briefly considered as the leading candiate scheme. The high-level group terms include: ‘Stationary non-syndromic photoreceptor dystrophies’, ‘Progressive non-syndromic photoreceptor dystrophies’, ‘Syndromic retinal dystrophies’, ‘Macular dystrophies’, ‘Choroidal dystrophies’, ‘Hereditary vitreoretinopathies’. Several uncertainties were identified in using this approach for OD. Specifically whether clinical diagnoses could separate patients into these groups (e.g., reportedly 20% of children with LCA without associated anomalies develop intellectual disability 8 ), or whether the criteria for specific terms were clear (e.g., classification as ‘macular dystrophy’ if occurring only in isolation or as part of other pathologies). In addition, there are some differences between the published literature and the Orphanet online tool where ‘macular dystrophies’ appear within ‘isolated progressive inherited disorders’ or ‘syndromic inherited disorders’, and not as a separate grouping at the same level.

Table 3.

Alternative ophthalmic grouping schemes of IRDs.

| Sergouniotis et al 2019 19 | Orphanet Rare Disease Ontology 18 | Verbakel et al 2018 13 | Fenner et al 2021 24 | Georgiou 2021 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary non-syndromic photoreceptor dystrophies, | Stationary non-syndromic photoreceptor dystrophies, (Includes Macular dystrophy) | Stationary retinal disease | ||

| Progressive non-syndromic photoreceptor dystrophies, | Progressive non-syndromic photoreceptor dystrophies, (Includes Macular dystrophy) | Progressive retinal disease, (includes Macular dystrophy) | ||

| Leber congenital amaurosis and early onset severe retinal dystrophy | ||||

| Syndromic retinal dystrophies, | Syndromic retinal dystrophies, | Syndromic forms of retinitis pigmentosa | ||

| Macular dystrophies, | Inherited degeneration involving the macular | Macular dystrophies | ||

| Choroidal dystrophies, | Choroidal dystrophies, | Chorioretinal dystrophies, | Chorioretinal degenerations | Chorioretinal dystrophies |

| Hereditary vitreoretinopathies | Hereditary vitreoretinopathies | Inherited vitreoretinopathies | ||

| Female carriers of inherited retinal dystrophies | ||||

| Metabolic disorders | ||||

| Genetic diseases | Mitochondrial disorders | |||

| cone-rod degenerations | cone and cone-rod dystrophies | |||

| cone dysfunction syndromes | ||||

| rod-cone degenerations, | rod-cone dystrophies | |||

| rod dysfunction syndromes |

Under the classification by Sergouniotis et al 2019, 19 the clinical groups would not align with pathological genes associated with IRDs. This is because a single gene may be associated with clinical manifestations across multiple IRD groups. 19 Some examples include the following: EYS (eyes shut homolog gene) mutations are associated with RP as the most common type of clinical presentation (90%). However, macular dystrophy and autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy (arCRD) are other possible manifestations of EYS-retinal dystrophy (requiring both RP and macular groups). Also, the BEST1 (bestrophin 1) gene mutations can result in a spectrum of ocular phenotypes such as macular dystrophy or vitreoretinochoroidopathy. 20

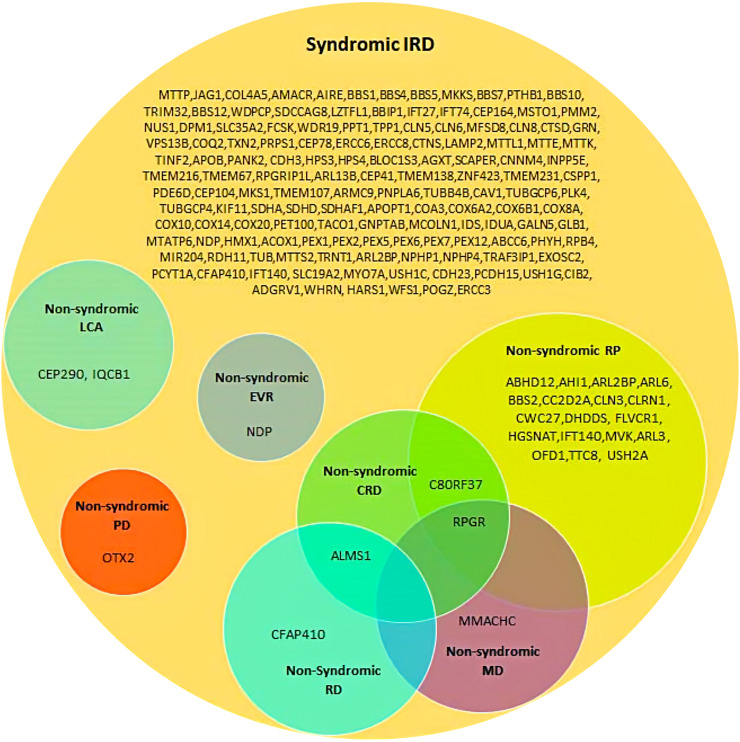

There is also overlap between syndromic and non-syndromic groups with approximately 28 different genes already having been identified as crossing these groupings. (See Figure 2 9 ). Examples include the USH2A (Usherin) gene where the Cys759Phe mutation is found in 4 to 5% of recessive RP without hearing loss. The CEP290 (centrosomal protein 290) gene in non-syndromic LCA10, 21 is also associated with LCA syndromes (e.g., Joubert syndrome). True interindividual variability has also been described, despite the same homozygous mutation. For example, in patients with the homozygous c.12del LRAT (lecithin retinol acyltransferase) mutation, some patients carry an RP phenotype, and others a cone-rod dystrophy (CORD) phenotype. 11

Figure 2.

A venn diagram showing the involvement of syndromic IRD genes in non-syndromic IRD phenotypes. CRD: cone-rod dystrophy; EVR: exudative vitreoretinopathy; LCA: Leber congenital amaurosis; MD: macular dystrophy; PD: pattern dystrophy; RD: retinal dystrophy; RP: retinitis pigmentosa. Reproduced unchanged with permission of authors (Tatour Y and Ben-Yosef T). 9 © 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

COMP also looked at possible alternative clinical groupings. Firstly, Verbakel et al 2018 13 presents slightly different high-level groups: ‘Progressive retinal disease’, ‘Stationary retinal disease’, ‘Inherited vitreoretinopathies’, ‘Chorioretinal dystrophies’, ‘Female carriers of inherited retinal dystrophies’, also separating syndromic, and non-syndromic RP groups. Likewise, during development of a web-based interoperable registry for inherited retinal dystrophies in Portugal (the IRD-PT), 22 the authors presented a further slight variation of the high-level grouping of terms based on Orphanet with macular terms as a subset within ‘isolated progressive inherited retinal disorders’.

The Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) 23 provides a standardised hierarchy of phenotypic terms including retinal dystrophy, retinopathy, abnormal choroid morphology, macular dystrophy and macular degeneration. Although mapped to Orphanet for possible disease associations, the hierarchy of the HPO terminology would not satisfy the OD need for a group of clearly defined medical diseases.

However, Fenner et al 2021 24 indicated that the majority of IRDs can be classified as one of four broad subtypes: ‘rod-cone degenerations’, ‘cone-rod degenerations’, ‘chorioretinal degenerations’ and ‘degenerations involving the macula’. Under this alternative grouping, any associated syndromes are included under the corresponding ophthalmic subtypes. The authors note that the clinical presentation of the subgroup of ‘chorioretinal degenerations’ can vary depending on the disease and may involve loss of central vision such as in the case of central areolar choroidal dystrophy, gyrate atrophy and choroideremia. The authors also add that ‘degenerations involving the macula’ often overlap with the three other groups, are more clinically heterogeneous, and are diagnostically more challenging because of their overlap with many acquired diseases.

Also Georgiou 2021 25 presents similar higher-level groups based on ‘macular dystrophies’,’ cone and cone-rod dystrophies’, ‘cone dysfunction syndromes’, ‘Leber congenital amaurosis’, ‘early onset severe retinal dystrophy (EOSRD)’, ‘rod-cone dystrophies’, ‘rod dysfunction syndromes’ and ‘chorioretinal dystrophies’. The groups overlap to some degree with the groups proposed by Fenner et al, 24 with more granularity based on a combination of aetiology and location of morphology.

Aside from grouping systems, other pertinent literature was consulted including trends, prevalence, and range of products under development for IRDs. Regarding trends, the understanding of phenotypical features and associated genetic defects continues to evolve. For example, Usher syndrome was traditionally classified into three different subtypes depending on the age of onset, severity and progression of the symptoms, and the presence or absence of vestibular dysfunction. However, new reports have been published regarding candidate genes, and a revised genotype–phenotype correlation and insights into the phenotypic spectrum of the disease. 10 Authors, including the ERN–EYE, highlight the importance of an exhaustive molecular diagnosis, because such diagnoses can be targets for potential therapies and provide information for genetic counselling and the risk of inheritance by other family members.26–28

It is recognised that patients can encounter delayed diagnoses: a recent EU survey of specialist centers by EVICR.net 29 showed that patients with biallelic RPE65 mutation-associated IRD had as referral diagnosis: early-onset severe retinal dystrophy (EOSRD) in 16.8%, Leber's congenital amaurosis in 38.2%, retinitis pigmentosa/rod-cone dystrophy in 28.1%, and unclassified visual impairment in 17.0% of the cases. According to that survey, 25% of the centers changed the referral diagnosis in >47.5% of the cases in their centres. According to different publications 25–80% of the cases are resolved, but not all IRDs have a successful molecular diagnosis.30–33 Leroy 6 notes that IRD can be classified by multiple factors including genetic associations, presence of syndromic features, affected organelles, age of onset, retinal layer affected, retinal region affected and type of functional loss but that all clinical descriptions must lead to genetic testing for definitive diagnosis, and that clinical classifications have progressively lost importance with the advent of molecular testing.

Regarding prevalence, the highest group level term (IRD) is estimated to have a prevalence between 0.03% - 0.05% in UK or Republic of Ireland.34,35 IRD causational-gene frequencies have been mostly calculated in specific cohorts or countries. Recently, Schneider et al 2022 12 compiled 31 papers and created the Global Retinal Inherited Disease (GRID) dataset that covers the most common IRD phenotypes. Hanany 2020 further estimated the prevalence of different gene mutation associated with IRDs. 36

On the therapeutic front, several candidates for broad gene-agnostic therapies are being tested such as neurotrophic factors or growth factors.37,38 Other possible pharmacological therapies are focused on slowing down the progression of IRDs and maintaining vision, mainly through anti-apoptotic (or other cell death inhibition), antioxidant and/or anti-inflammatory mechanisms, 39 cell therapies or optogenetic approaches. Reportedly, some therapies with a broad mechanism of action ameliorate some, but not other RP models. Further development programs targeting therapies to specific variant types (mutations) are already underway. A variety of mutation-specific and mutation-independent approaches are being investigated. 40 Therapies targeting modifier genes are also under investigation.38,41,42

Patient and clinician consultation

To further inform the new OD options in IRDs, COMP undertook a consultation of relevant patient and clinical experts. Nominations for IRD clinical experts were requested from ERN-EYE. Nominations for patient representatives were requested from IRD patient organisations. All participants were required to complete a declaration of interests. The questions to experts were provided in advance. All invitees were invited to complete the questionnaire. Experts were asked about the relevance and distinctness of the proposed OD grouping, potential implications of a change in OD approach in IRD, and the best level of grouping of retinal dystrophies from a clinical perspective when combined with specific genes. They were also asked about the possibility of extrapolation of findings in patients with a specific gene defect and a typical phenotype to those with an atypical one. Experts were also asked for their insights into potential prevalence estimates. Responses of experts were summarised, presented, and further discussed in an expert consultation meeting on the 17th of June, 2022.

Five patient representatives participated in the consultation process representing patient organisations including Retina International, Retina Suisse, EUPATI, Pro Rare (Austria), and Fighting Blindness. Twelve EU Clinical IRD experts participated in the process. Representatives of impacted EU regulatory committees and secretariats also participated. The outcome of the consultation exercise was presented to COMP.

The expert meeting provided significant progress on groupings for Orphan designation. Issues raised by patient representatives included the need for alignment between molecular classification and Orphanet, the concern that development of treatments for ultra-rare genetic disorders may not be prioritised by developers, and that potentially treatable patients should not be excluded from potential clinical trials by reason of orphan designations. The clinical experts indicated that IRD is an evolving field of research, and that terminology should be able to accommodate further scientific progress.

The expert consultation indicated that the criteria for the Sergouniotis 2019 19 groups could be clearer, that a relevant clinical diagnostic guideline would be welcome, and that the current clinical trend was for increasing molecular/genetic diagnoses. Clinical experts said that phenotypic diagnoses could be subject to interpretation and regional variation. The experts indicated that Sergouniotis 2019 19 groups were not mutually exclusive for treatments based on specific genes, gene mutations, or broad therapies. The estimates for prevalence for new groupings were currently uncertain. Regarding the optimised groupings for OD, there was a general consensus that a 2-level grouping would be useful and relatively discriminating, and a proposal was provided. The final optimised groupings, based on the expert consultation, are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Optimised grouping for ODs with broad pharmacological approaches in IRDs.

| Optimised grouping for OD |

|---|

| 1. Non-syndromic IRD |

| 1.1. Cone-dominant phenotype |

| 1.2. Rod-dominant phenotype |

| 1.3. Macular dystrophy |

| 2. Syndromic IRD |

| 2.1. Cone-dominant phenotype |

| 2.2. Rod-dominant phenotype |

| 2.3. Macular dystrophy |

| 3. Inherited choroidal dystrophies |

| 4. Hereditary vitreoretinopathies |

The term dominant refers to temporally sequential cone > rod or rod > cone affectation, thus indicating which photoreceptor are predominantly affected, not to inheritance patterns.

IRD: Inherited Retinal Dystrophy;

OD: Orphan Designation.

The term dominant is used to refer to temporal sequences of cone > rod or rod > cone affectation, and thus which photoreceptors are predominantly affected in each case; it does not refer to inheritance pattern in this context. The progressive/non-progressive dichotomy was not retained as emerging research indicates that at least some classic non-progressive conditions may show progressive degeneration. 43

Regarding gene-specific ODs, consulted experts acknowledged that any mutation-specific development could fall under the gene-specific OD, that the IRD term is needed in addition to a specific gene, but also, that not all IRD patients obtain a molecular/genetic diagnosis.

COMP deliberation and conclusion

Further to the literature review and expert consultation, COMP recognised that a universally accepted consensus does not exist for grouping IRD. The Committee discussed the available options for the purpose of OD, and the potential advantages and disadvantages of each approach. Table 5 summarizes these potential advantages and disadvantages associated with each OD approach.

Table 5.

Benefits and issues for different approaches to orphan designation.

| Benefits and issues for different approaches to Orphan designation | |

|---|---|

| Approach 1: Optimised Clinical grouping | Approach 2: Gene-specific |

| Benefits | |

| Intermediate level grouping, Still relatively discriminating | Very granular, allows delineation of distinct subsets |

| Best for non-targeted therapies | Scientifically appropriate for targeted therapies |

| Best for encompassing spectrum of phenotypic variability in gene-targeting therapies | |

| Concordant with published groupings | In line with regulatory guidance for Orphan designation |

| Trend is for molecular diagnoses in IRD | |

| High proportion of targeted therapies to date in IRD | |

| Issues/problems | |

| Not fully clear criteria for each group, clinical manifestations are variable, diagnoses can be variable | Not all patients obtain a molecular/genetic diagnosis |

| Categories are not exclusive for treatment based on specific genes or broad therapies; thus multiple OD envisaged for such a development program | Broad therapies would require multiple ODs |

| Trend is for molecular/genetic diagnoses | IRD term is needed (lower term grouping) in addition to gene |

| Mutation-specific developments are already a reality; but any mutation specific development could fall under the gene-specific OD. | |

| Prevalence estimates for new groupings needed | Prevalence estimates for gene-specific entities needed |

IRD: Inherited Retinal Dystrophy;

OD: Orphan Designation.

Use of the highest-level ‘IRD’ term alone for grouping OD conditions appeared very broad scientifically and clinically, with multiple rare conditions of different aetiologies included in such a broad grouping that would entail different pharmacological approaches and developments.

COMP decided that a single OD approach was insufficient and considered that three different options for OD conditions were needed. COMP could select the best option to designate the condition depending on the application. COMP recognised the operational challenges of the three approaches but deemed these surmountable in terms of defining prevalence, and any diagnostic uncertainties considering the available scientific literature.

Firstly, for targeted gene therapies, COMP could use “inherited retinal dystrophy” complemented with the gene target. This would ensure that the broadest applicable scope of treatable patients would be included in the OD. COMP considered that this is scientifically justified, and the leanest regulatory approach to designating the condition considering variable phenotypes associated with a single gene defect.

Secondly, for therapies with a broad mechanism of action, the optimised OD grouping (Table 4) could be used, offering both inclusivity whilst being relatively discriminating and an updated strategy for orphan designation for these kinds of products. These phenotypes include inherited pathological dysfunction as well as inherited progressive degenerations. This approach would not preclude the need for multiple orphan designations if a particular broad therapy could target more than one group.

Finally, some conditions recognised as IRDs may not fit the optimised OD grouping as in Table 4. Therefore, occasional singular orphan designations outside the structure may still be necessary for treatments targeting these conditions which are not gene-specific. COMP considered that any need for additional subgroups in the optimised grouping could be reviewed with experience in OD.

The target population, the choice of grouping, and why any groups outside the chosen group would not be treatable, should be justified by the sponsor at the time of OD.

Regarding syndromic IRDs, using Table 4 an optimised grouping (or IRD + gene) could be applied when a local ocular treatment is intended. For a systemic treatment, the sponsor should justify the approach taken for determining the orphan condition. This approach could have wider reverberations in how orphan designations meant for treatment of specific aspects of systemic syndromes are to be generally approached in the future.

Overall, this three-pillar strategy is considered to provide a robust yet flexible framework for orphan designations in the complex field of the genetic spectrum underlying inherited retinal dystrophies. By discarding the more rigid and somewhat out-dated phenotypically derived classification scheme traditionally used for IRD conditions, COMP now has the possibility of using a more agile decision matrix that allows for orphan designations adapted to the clinical state-of-the-art of the treatment under discussion. Hence, this newly adopted ontology will make it easier for future innovative treatments, such as gene-therapies, to be awarded the status of orphan drug and hence receive the accordant benefits meant to facilitate medicine development and future commercialisation.

Notwithstanding, the currently adopted approach is not meant to be seen as immutable. COMP is aware that both the scientific knowledge within the field of rare eye diseases, and the associated new therapies being developed, are very much rapidly moving targets. Hence it is acknowledged that future revisions and changes to this newly adopted ontological strategy for IRDs will need to be undertaken in function of progressing scientific insight.

One such limitation of this newly proposed ontology is for example the fact that novel ‘gene-independent’ genetic treatments, such as modifier gene or optogenetic therapies, may still pose problems for the new ontological scheme as presented. These therapies are generally able to treat heterogenic groupings of genetic deficiencies and hence further challenge the notion of being applicable to a ‘distinct medical entity’, which is the current fundamental regulatory base for designating an orphan condition.

In conclusion, the new strategy of COMP regarding ODs in the domain of IRDs reflects regulatory adaptation to the evolution of our scientific understanding in the field of rare eye diseases and the development of innovative therapies. Therefore, if confirmed as appropriate with future regulatory experience, it is not excluded that a similar approach could be applied to other disease areas in the near future.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-ejo-10.1177_11206721241236214 for Inherited retinal dystrophies and orphan designations in the European Union by Jane Moseley, Tim Leest, Kristina Larsson, Armando Magrelli and Violeta Stoyanova-Beninska in European Journal of Ophthalmology

Acknowledgements

Clinical experts consulted by questionnaire and/or meeting and who provided comments on the manuscript:

Dominique Bremond Gignac (Université de Paris Cité (France)), Birgit Lorenz, (Universitaetsklinikum Bonn and Justus-Liebig-University Giessen (Germany), ERN-Eye Member, Member, EVICR.net), Alejandra Daruich (Necker Enfants Malades Hospital, Paris Cité University (France)),Massimo Nicolò (Università di Genova Ospedale Policlinico San Martino (Italy)), Joao Pedro Marques (Centro Hospitalar e Universitario de Coimbra (Portugal)), Lotta Gränse (Skåne University Hospital, Lund University (Sweden)), Francesco Parmeggiani (University of Ferrara (Italy) - ERN-EYE scientific representative), Sten Andréasson (University Hospital Lund (Sweden)), Irina Balikova (University Hospital of Leuven (Belgium) / Belgian ERN-EYE member), Cristina Irigoyen (Donostia University Hospital (Spain)), Gerhard Garhöfer (Medical University of Vienna (Austria)), Ulrika Kjellström, (Skanes Universitetssjukhus (Sweden)).

The 5 patient representatives who participated in the consultation process from patient organisations including from Retina International (Petia Stratieva), Retina Suisse, EUPATI, Pro Rare (Austria), and Fighting Blindness (Mary Lavelle).

Monica Gomar; EMA for administrative and project support.

EMA members of the Committee of Orphan Medical Products for plenary discussion and decision on the project.

EMA committee representatives from the Committee for Advanced Therapies, the Paediatric Committee, The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, and EMA participants from Paediatrics Office, Orphan Medicines Office, and Therapies for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders Office for scientific and administrative support and liaison.

Footnotes

Authorship: All authors contributed to drafting and review of article, review of existing OD in IRD and scientific literature, and preparation of, participation in of the expert consultation, and reporting of all data to the COMP. JM conducted the literature search and collected and analysed the existing IRD data on OD.

Data availability statement: Study Data and data from documents are available in line with published EMA policy 0043 - European Medicines Agency policy on access to documents, or policy 70 - European Medicines Agency policy on publication of clinical data for medicinal products for human use.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval statement, patient consent statement or clinical trial registration: This is secondary, data-based research without any direct clinical study, individual patient data, and thus were not needed. Patient representatives participated in the consultation exercise and had the opportunity to comment on the manuscript and acknowledgements.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources: permissions have been granted by relevant authors.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Jane Moseley https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4889-5953

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Guideline on the format and content of applications for designation as orphan medicinal products and on the transfer of designations from one sponsor to another.

- 2.Commission E. Commission notice on the application of Articles 3, 5 and 7 of regulation (EC) No 141/2000 on orphan medicinal products. Official Journal of the European Union 2016; 59: 3–9. doi: 52016XC1118(01). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 1999 on orphan medicinal products. In: European Parliament CotEU, (ed.). Offical Journal of the European Union1999, p. 1–5.

- 4.COMP meeting minutes October 2022, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/minutes/minutes-comp-meeting-4-6-october-2022_en.pdf (accessed June 30, 2023).

- 5.Statement on the amended policy on orphan designations for inherited retinal dystrophies https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/minutes/minutes-comp-meeting-4-6-october-2022_en.pdf (accessed June 30, 2023).

- 6.Leroy B. Brave new world; gene therapy for inherited retinal diseases, https://www.aao.org/assets/bebfbaef-a092-45b0-9883-c563331546ae/636649294795430000/july-2018-eyenet-supplement-pdf?inline=1 (accessed September 13, 2023).

- 7.Cremers FPM, Boon CJF, Bujakowska K, et al. Special issue Introduction: inherited retinal disease: novel candidate genes, genotype-phenotype correlations, and inheritance models. Genes (Basel) 2018; 9: 20180416. doi: 10.3390/genes9040215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang SH, Sharma T. Leber congenital amaurosis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018; 1085: 131–137. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-95046-4_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatour Y, Ben-Yosef T. Syndromic inherited retinal diseases: genetic, clinical and diagnostic aspects. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020; 10: 20201002. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10100779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuster-Garcia C, Garcia-Bohorquez B, Rodriguez-Munoz A, et al. Usher syndrome: genetics of a human ciliopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 20210623. doi: 10.3390/ijms22136723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talib M, Boon CJF. Retinal dystrophies and the road to treatment: clinical requirements and considerations. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2020; 9: 159–179. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider N, Sundaresan Y, Gopalakrishnan P, et al. Inherited retinal diseases: linking genes, disease-causing variants, and relevant therapeutic modalities. Prog Retin Eye Res 2022; 89: 101029. 20211125. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2021.101029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verbakel SK, van Huet RAC, Boon CJF, et al. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Retin Eye Res 2018; 66: 157–186. 20180327. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.RetNet; the Retinal Information Network, https://web.sph.uth.edu/RetNet/ (accessed March 1, 2023).

- 15.Sorrentino FS, Gallenga CE, Bonifazzi C, et al. A challenge to the striking genotypic heterogeneity of retinitis pigmentosa: a better understanding of the pathophysiology using the newest genetic strategies. Eye (Lond) 2016; 30: 1542–1548. 20160826. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang S, Vaccarella L, Olatunji S, et al. Diagnostic challenges in retinitis pigmentosa: genotypic multiplicity and phenotypic variability. Curr Genomics 2011; 12: 267–275. doi: 10.2174/138920211795860116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sallum JMF, Kaur VP, Shaikh J, et al. Epidemiology of mutations in the 65-kDa retinal pigment epithelium (RPE65) gene-mediated inherited retinal dystrophies: a systematic literature review. Adv Ther 2022; 39: 1179–1198. 20220130. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-02036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orphanet nomenclature of rare diseases.

- 19.Sergouniotis PI, Maxime E, Leroux D, et al. An ontological foundation for ocular phenotypes and rare eye diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2019; 14: 20190109. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0980-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.OMIM - Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; 607854, https://omim.org/entry/607854 (accessed March 1, 2023).

- 21.Huang CH, Yang CM, Yang CH, et al. Leber's congenital amaurosis: current concepts of genotype-phenotype correlations. Genes (Basel) 2021; 12: 20210819. doi: 10.3390/genes12081261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marques JP, Carvalho AL, Henriques J, et al. Design, development and deployment of a web-based interoperable registry for inherited retinal dystrophies in Portugal: the IRD-PT. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020; 15: 304. 20201027. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01591-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohler S, Gargano M, Matentzoglu N, et al. The human phenotype ontology in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 2021; 49: D1207–D1217. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fenner BJ, Tan TE, Barathi AV, et al. Gene-Based therapeutics for inherited retinal diseases. Front Genet 2021; 12: 794805. 20220107. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.794805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Georgiou M, Fujinami K, Michaelides M. Inherited retinal diseases: therapeutics, clinical trials and end points-A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2021; 49: 270–288. 20210320. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perea-Romero I, Gordo G, Iancu IF, et al. Genetic landscape of 6089 inherited retinal dystrophies affected cases in Spain and their therapeutic and extended epidemiological implications. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 1526. 20210115. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81093-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellner U, Jansen S, Bucher F, et al. Diagnosis of inherited retinal dystrophies. Relevance of molecular genetic testing from the patient's perspective. Ophthalmologie 2022; 119: 820–826. 20220321. doi: 10.1007/s00347-022-01602-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Black GC, Sergouniotis P, Sodi A, et al. The need for widely available genomic testing in rare eye diseases: an ERN-EYE position statement. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2021; 16: 142. 20210320. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01756-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorenz B, Tavares J, van den Born LI, et al. Current management of patients with RPE65 mutation-associated inherited retinal degenerations in Europe: results of a multinational survey by the European vision institute clinical research network. Ophthalmic Res 2021; 64: 740–753. 20210308. doi: 10.1159/000515688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorenz B, Tavares J, van den Born LI, et al. Current management of inherited retinal degeneration patients in Europe: results of a multinational survey by the European vision institute clinical research network. Ophthalmic Res 2021; 64: 622–638. 20210119. doi: 10.1159/000514540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia Bohorquez B, Aller E, Rodriguez Munoz A, et al. Updating the genetic landscape of inherited retinal dystrophies. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021; 9: 645600. 20210713. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.645600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li AS, MacKay D, Chen H, et al. Challenges to routine genetic testing for inherited retinal dystrophies. Ophthalmology 2019; 126: 1466–1468. 20190424. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perea-Romero I, Blanco-Kelly F, Sanchez-Navarro I, et al. NGS And phenotypic ontology-based approaches increase the diagnostic yield in syndromic retinal diseases. Hum Genet 2021; 140: 1665–1678. 20210826. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02343-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gong J, Cheung S, Fasso-Opie A, et al. The impact of inherited retinal diseases in the United States of America (US) and Canada from a cost-of-illness perspective. Clin Ophthalmol 2021; 15: 2855–2866. 20210701. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S313719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galvin O, Chi G, Brady L, et al. The impact of inherited retinal diseases in the republic of Ireland (ROI) and the United Kingdom (UK) from a cost-of-illness perspective. Clin Ophthalmol 2020; 14: 707–719. 20200305. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S241928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanany M, Rivolta C, Sharon D. Worldwide carrier frequency and genetic prevalence of autosomal recessive inherited retinal diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020; 117: 2710–2716. 20200121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913179117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chew LA, Iannaccone A. Gene-agnostic approaches to treating inherited retinal degenerations. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023; 11: 1177838. 20230413. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1177838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.John MC, Quinn J, Hu ML, et al. Gene-agnostic therapeutic approaches for inherited retinal degenerations. Front Mol Neurosci 2022; 15: 1068185. 20230109. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.1068185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olivares-Gonzalez L, Velasco S, Campillo I, et al. Retinal inflammation, cell death and inherited retinal dystrophies. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 20210220. doi: 10.3390/ijms22042096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng D, Ragi SD, Tsang SH. Therapy in rhodopsin-mediated autosomal dominant retinitis Pigmentosa. Mol Ther 2020; 28: 2139–2149. 20200825. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S, Datta S, Brabbit E, et al. Nr2e3 is a genetic modifier that rescues retinal degeneration and promotes homeostasis in multiple models of retinitis pigmentosa. Gene Ther 2021; 28: 223–241. 20200302. doi: 10.1038/s41434-020-0134-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiu W, Lin TY, Chang YC, et al. An update on gene therapy for inherited retinal dystrophy: experience in leber congenital amaurosis clinical trials. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 20210426. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michalakis S, Schon C, Becirovic E, et al. Gene therapy for achromatopsia. J Gene Med 2017; 19: e2944. doi: 10.1002/jgm.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-ejo-10.1177_11206721241236214 for Inherited retinal dystrophies and orphan designations in the European Union by Jane Moseley, Tim Leest, Kristina Larsson, Armando Magrelli and Violeta Stoyanova-Beninska in European Journal of Ophthalmology