Abstract

Background

Despite the availability of evidence-based treatments for anorexia nervosa (AN), remission rates are moderate, and mortality is high. Olanzapine is used as adjunct therapy for AN in case of insufficient response to first-line treatments, even though the evidence is limited. Its effect on eating disorder (ED) psychopathology, its efficacy and tolerability, and its acceptability and adherence rate are unclear.

Methods

We assessed the feasibility of a future definitive trial on olanzapine in young people with AN in an open-label, one-armed feasibility study that aimed to include 55 patients with AN or atypical AN aged 12–24 who gained < 2 kg within at least one month of treatment as usual (TAU) during outpatient, inpatient, or day-care treatment. Time points for assessments were at baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and 6 or 12 months. We estimated the following planning parameters: Recruitment rate (number of patients who agreed to take olanzapine/number eligible), adherence rate (number adhering to treatment/number recruited) and attrition rate (number completing study assessments/number recruited). In addition, two exploratory effect size parameters were estimated: Mean change in body mass index (BMI) and mean change in ED psychopathology.

Results

Fifty-two people were pre-screened (June 2022 to May 2023; 10 study sites in England). 13 were ineligible at pre-screening . Of the 39 approached, 4 were found ineligible at screening. Of the remaining 35 eligible, 10 declined and 5 did not take part for other reasons. Thus, 20 participants were recruited and started olanzapine (recruitment rate: 20/35 = 57%). 15 out of 20 (75%) continued olanzapine for ≥ 16 weeks, and 13 participants (65%) remained in the trial until follow-up (either 6 or 12 months). Participants experienced, on average, a decrease over time in their Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) Global scores (0.07 per week, N = 20) and an increase in BMI (0.08 kg/m2 per week, N = 20) during treatment with olanzapine plus TAU.

Conclusions

Possible reasons for the recruitment difficulties and low adherence rate include the high clinical workload of ED services during the COVID-19 pandemic and the reluctance of patients to agree to take olanzapine under the relatively restricted conditions of a clinical study.

Trial registration

International standard randomised controlled trial register number: ISRCTN80075010. Registration date: 27/04/2022.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-024-06215-y.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, Olanzapine, Feasibility, Recruitment, Adherence, Attrition, Side effects

Background

Despite evidence-based psychological treatments, anorexia nervosa (AN) still has low rates of remission and a high risk of mortality [1]. The British physician William Withey Gull who described the symptoms of AN for the first time in 1873, already recommended a pharmacological approach in a broader sense as he advised: “With the nourishment, I would conjoin a dessertspoonful of brandy every two or three hours” [2].

The use of first-generation antipsychotics to treat AN was investigated in open and uncontrolled trials but also in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in the 1970s and 1980s, and it was found that most of these medications were superior to placebo in terms of weight gain. However, most reports showed that first-generation antipsychotics did not have any significantly beneficial effect on anorexic psychopathology, such as anxiety and body image disturbances [3, 4].

In 1996, olanzapine, a second-generation antipsychotic, was U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved and introduced into the market. Almost 10 years later, when appetite and weight increase became known as frequent side effects of olanzapine, psychiatrists started to trial olanzapine for the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Since then, four RCTs showed a significant effect on weight gain in people with AN [5–8]. Like first generation antipsychotics, olanzapine led to an increase in weight, but data on AN psychopathology were inconsistent across RCTs. In adolescents, the effect of olanzapine is less clear. An open study [9] reported a significant increase in body weight under olanzapine, but one pilot study found no significantly different effect on body weight compared with placebo [10]. Thus, the latest guideline update of the World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) on the pharmacological treatment of eating disorders (EDs) gave only a limited recommendation for olanzapine to achieve weight gain if treatment as usual which includes psychotherapy, nutritional advice and physical health monitoring does not lead to treatment response, and the WFSBP guidelines highlighted that there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of olanzapine in adolescents with AN [11]. Apart from the limited evidence on psychopathology and its effectiveness in adolescence, RCTs have shown a reluctance of patients to take olanzapine [7] and low adherence rates [8, 11].

In summary, there is some evidence for a clinically significant effect of olanzapine on body weight in people with AN. However, data on psychopathology and clinical evidence for adolescent patients are lacking. Therefore, we designed a protocol for an open-label feasibility study to test Olanzapine for young PEople with aNorexia nervosa (OPEN). The protocol has already been published elsewhere [12]. Here, we report the outcome of this open-label feasibility study.

Methods

Study design

Study participants

We performed an open-label feasibility study in adolescents (12–17 years old) or young adults (18–24 years old) with AN. The OPEN study included patients aged 12 to 24 years to target the age range at which AN incidence is at peak [13] with the aim to maximise and speed up the treatment effect by adding olanzapine as an adjunct therapy in case of insufficient response to first-line treatments.

The aim was to include 55 young people with AN who received inpatient, day-care or outpatient treatment, were diagnosed with AN or atypical AN according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM‐5), had gained less than 2 kg within at least 1 month of treatment as usual (TAU) and were able to read and write in English. Study participants were treated with olanzapine and followed up for up to 12 months. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, at 8 weeks, 16 weeks, 6 months and 12 months after starting olanzapine. The study adhered to CONSORT guidelines.

The cut-off point of 2 kg weight gain within one month was chosen for two reasons: First, according to a previous systematic review and meta-analysis, progress in the first month of treatment was found to be predictive of further therapy response [14] and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that treatment progress for AN should be reviewed after one month [15]. Second, guidelines for AN inpatient treatment suggest a minimum weight gain of 0.5 kg per week [15, 16]. Taken together, after 4 weeks of treatment which is about one month, a patient with AN should have gained 2 kg of body weight.

Exclusion criteria were serious self-harm, suicidality, psychotic disorder, serious medical comorbidities that are contraindications for olanzapine, current alcohol or substance use disorder, current use of major tranquilliser or opioids, serious electrocardiogram (ECG) or laboratory abnormalities, other psychopharmacological medication at stable dose for less than 4 weeks, medication interacting with olanzapine, pregnancy or breastfeeding, being of childbearing potential and unwilling to have pregnancy tests, objecting to taking effective contraceptive measures, and taking part in another pharmacological trial for AN. For further details regarding the exclusion criteria, see the published protocol [12].

Potential participants were identified by the treating clinicians at the recruiting National Health Service (NHS) ED services (outpatient, inpatient or day-care), and patients were informed about the study. If the patients were interested, they were contacted by the research team and eligibility criteria were assessed by a delegated member of the research team after obtaining written informed consent. To assess the presence of exclusion criteria at screening, the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Tool (ASSIST) [17] was used, an ECG was performed, and blood was taken (either as part of standard practice or as part of the OPEN study).

The follow-up period was originally designed to be 12 months. However, as it became evident that the study would not meet its recruitment target, it was agreed to shorten the study to a follow-up period of 6 months.

Intervention

Olanzapine was prescribed off-label for AN in the form of tablets or dispersible tablets of 2.5, 5, 7.5 or 10 mg, from any brand or manufacturer with a marketing authorisation and in original packaging. Olanzapine was initiated at 1.25 or 2.5 mg/day in adolescents. In adults, the starting dose was 2.5 mg/day. Patients were maintained at this dose if it was deemed clinically sufficient by their treating clinicians in terms of weight restoration and improvement regarding ED psychopathology. A slow titration schedule was followed, comprising weekly increments of 1.25 or 2.5 mg/day for adolescents and 2.5 mg/day for adults, up to a maximum of 10 mg/day for both.

Feasibility parameters

The primary feasibility parameters to assess the feasibility of a future definitive RCT included recruitment (the aim was to recruit 55 participants), adherence and completion of the assessments. To inform the ability to recruit sufficient numbers of participants for a future definitive RCT, recruitment was assessed by the total number of recruited people out of the required sample size, and rate of recruitment in terms of number recruited/number who were approached and eligible. Rates of adherence to olanzapine treatment (out of number recruited) were assessed over the entire follow-up period to inform the acceptability of treatment through adherence. Rates of completion of baseline and follow-up assessments (out of number recruited) were reported to inform the sample size calculation for a future trial [12].

The sample size calculation was made based on estimating the feasibility parameter “rate of adherence”: Assuming that 70% of patients took olanzapine for at least 16 weeks, a sample size of 55 patients could estimate a 95% confidence interval (CI) for this parameter with 12.2% margin of error (i.e., expected CI from 57.8 to 82.2%; for a more extreme attrition rate of 50% the margin of error increases to 13.3%) [12].

Secondary feasibility parameters were the feasibility of recording the following measures at baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks, 6 months and 12 months: Demographics, the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test, height, weight and body mass index (BMI), ED psychopathology questionnaires, general psychopathology questionnaires, health economic and quality of life assessments, olanzapine serum level, physical examination measures, ECG, laboratory parameters and a measure of sleepiness. We also asked about participants’ willingness to participate in a future blinded, placebo-controlled RCT at baseline and during further assessments.

Exploratory measures

The mean change in body mass index (BMI) and the mean change in ED psychopathology (EDE-Q Global Score) over time were explored in the sample to inform future sample size calculations.

To assess ED psychopathology, we used the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q [18]), the Revised Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire (BAVQ‐R; [19]) and the Self‐Regulation of Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (SREBQ [20]). For the assessment of general psychopathology, we applied the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS [21]) and the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS [22]). Health economic and quality of life measures included the Child, Adolescent and Adult Service Use Schedule (CAA‐SUS), a measure of health and social care service use, which was adapted for this study based on previous versions for young people and adults with EDs [23, 24], the youth version of the three-level EQ‐5D™ measure of health-related quality of life (the EQ-5D-Y-3 L [25]), and the Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale (EDSIS [26]).

Medication safety measures

To assess medication safety, we used the physical examination, ECG, the measurement of routine laboratory parameters and the UKU-Side Effect Rating Scale (UKU‐SERS [27]).

Qualitative outcomes

Participants’ experience of recruitment and treatment, acceptability, reluctance to take olanzapine and reasons for adherence and non-adherence were ascertained in qualitative interviews.

Statistical analyses

Descriptives

Means and standard deviations (SDs) are reported for descriptives of continuous variables and frequencies or proportions used to describe categorical variables. Published guidance was used to handle missing items in scales where present, otherwise scales were pro-rated if fewer than 20% of items were missing.

Feasibility parameters

The main feasibility outcome of recruitment is presented as a proportion of the required sample size and as the proportion of participants recruited out of those who were approached and eligible (with exact 95% confidence interval). Other feasibility parameters are also presented as proportions with exact 95% confidence intervals. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method [28]. Completion rates of individual measures are presented as numbers with percentages; some measures only applied to certain subgroups of the sample (e.g., the age-dependent measures) and completion rates are presented out of the number who should have completed the measure.

Adherence to treatment was pre-defined in the Statistical Analysis Plan as taking at least 16 weeks (112 days) of olanzapine calculated from the total number of daily doses taken according to pill returns. However, pill return data was entirely missing for 9 participants and incomplete for several other participants, and so adherence to the intervention has instead been primarily defined in terms of daily doses prescribed (greater than 112 days). Consequently, this does not represent adherence to olanzapine in the same way and is more reflective of all participants who remained in the trial.

Exploratory analyses: EDE-Q Global score, Weight (kg), and BMI (kg/m2) were explored for changes over time. The EDE-Q Global score was calculated by summing the four subscales and dividing the resulting total by the number of subscales (i.e. four) as per [29, 30].

Linear mixed models were used to model change over time in these measures, with time as the independent variable and with a random intercept for participant. Models using both categorical time (per the expected assessment time visit) and linear time (actual timing of assessment) were considered, with the latter used to calculate change in time per week (with 95% confidence intervals). Other time parameters were not considered due to the low sample size. These were constructed for the whole sample and in only the sample who “adhered” to olanzapine.

Baseline observations were included in the model as the reference group to estimate mean differences from baseline. Month 12 observations were omitted as there were only 2 observations of the EDE-Q at month 12 and no observations for Weight or BMI. All participants were included in these models if they had a least one observation of the measure (including at baseline). This linear mixed model approach assumes that data is missing at random; no other missingness mechanisms were considered as these analyses are intended to be exploratory only.

Scatter graphs were constructed with outcomes plotted against the actual timings of the assessment, with predicted values from the models used to plot an estimated trend over time (with confidence intervals).

No p-values were presented for any analyses, and all analyses were treated as underpowered and not to be used to make inferential conclusions.

Results

Patient enrolment and baseline characteristics

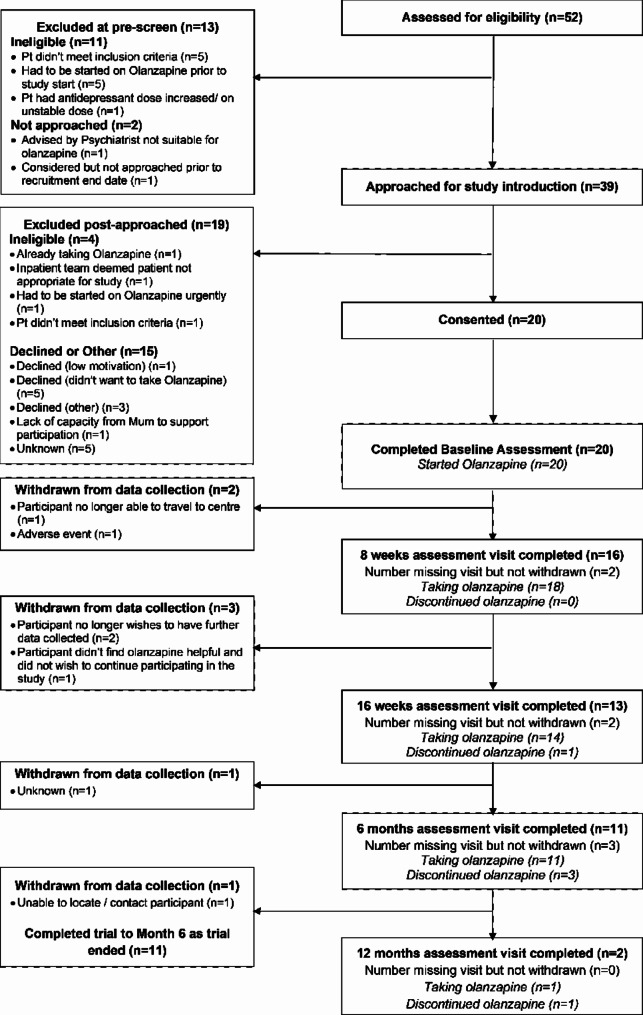

Participants were recruited across 10 sites in England from June 2022 to May 2023, and the study ended in December 2023 in accordance with the contract between the Sponsor and the Funder. Sites which recruited at least one patient into the study are listed in Supplementary S1. Three of the 10 sites did not consent any participants. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram [31] for the trial. Fifty-two people were assessed at pre-screening for initial eligibility, of which 13 were excluded. Thirty-nine people were therefore approached, of which 10 declined, four were found to be ineligible or became ineligible following being approached and five were excluded for an unknown reason as data were missing. Twenty participants were consented, all of whom had a baseline assessment and started olanzapine.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram

The main baseline demographics and clinical characteristics for the 20 consented participants are presented in Table 1. For a comprehensive synopsis of demographics, clinical characteristics and baseline measurement results see Supplementary S2.

Table 1.

Main baseline demographics and clinical characteristics for the 20 consented participants

| Baseline demographics/scales | Available data | n (%) / Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-reported gender | 20 (100%) | |

| Male | 0 (0%) | |

| Female | 19 (95%) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (5%) | |

| Ethnicity | 20 (100%) | |

| Black | 0 (0%) | |

| White | 15 (75%) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 2 (10%) | |

| Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups | 3 (15%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | |

| Primary diagnosis | 20 (100%) | |

| Anorexia Nervosa | 18 (90%) | |

| Atypical Anorexia Nervosa | 2 (10%) | |

| Setting at time of recruitment | 20 (100%) | |

| Outpatient | 18 (90%) | |

| Inpatient | 1 (5%) | |

| Day care | 1 (5%) | |

| Age | 20 (100%) | 16.3 (3.1) |

| Adolescents (12–17) | 15 (75%) | |

| Adults (18–24) | 5 (25%) | |

| Height (m) | 20 (100%) | 1.6 (0.082) |

| Weight (Kg) | 20 (100%) | 46 (7.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20 (100%) | 17 (1.8) |

| EDE-Q Global score | 20 (100%) | 4.8 (0.68) |

Feasibility measures

The main feasibility parameter was recruitment; 20 participants out of the 55 required per the sample size calculation were recruited and 20 participants were recruited out of the 35 who were approached and identified as eligible (57%, 95% CI, 39–74). Fifteen out of 20 (75%, 95% CI, 50–91) participants were prescribed olanzapine for over 112 days (16 weeks) during the study. However, body weight and BMI were measured in only 10 of these participants at week 8 and week 16, even though they were still in the study at this point in time. Supplementary S3 depicts a comprehensive overview of the feasibility parameters and their confidence intervals.

Thirteen out of 20 (65%, 95% CI, 41–85) participants remained in the study until follow-up (either 6 or 12 months). However, body weight and BMI were measured in only 11 of these participants at 6 months. Completion rates for the main individual measures at each timepoint are presented in Table 2. Comprehensive longitudinal summary statistics for all measures are reported in the Supplementary S4. Supplementary S5 depicts BMI descriptives over time split by age (adult vs. adolescents).

Table 2.

Completion rates for the main individual measures at each timepoint

| Scales | Week 8 completion (n, %) | Week 16 completion (n, %) | Month 6 completion (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (Kg) | 10 (50%) | 10 (50%) | 11 (55%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 10 (50%) | 10 (50%) | 11 (55%) |

| EDE-Q Global score | 11 (55%) | 9 (45%) | 7 (35%) |

Fourteen out of 18 participants (77%) at baseline said they would have participated in an RCT of olanzapine vs. placebo (3 participants, 17% responded as “don’t know” and data were missing for 2 participants). The percentage of people who would have agreed to take part in an RCT went down from 77% at baseline to 45% (5/11 participants) at month 6.

Adverse events

Thirteen adverse events were recorded affecting seven (35%) participants (see Supplementary S6). There were two adverse reactions reported: diarrhoea/incontinence (assessed as possibly related to olanzapine) and elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) (assessed as definitely related). There were no serious adverse events or serious adverse reactions reported. Two events of hospitalization for anorexia nervosa were reported, but neither were considered related to the intervention by trial investigators and these events were not considered serious adverse events for this trial as outlined in the protocol.

Exploratory change over time in outcomes

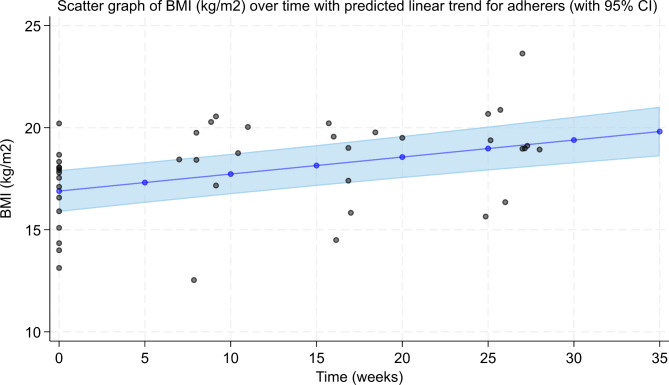

There was a mean decrease of 0.07 (0.04, 0.09 95% CI) in EDE-Q Global Score per week in the whole sample of 20 participants and a mean BMI increase of 0.08 kg/m2 (0.06, 0.10 95% CI) per week. These values did not change when analyses used only the subsample of 15 participants who had olanzapine prescribed over 112 days. See Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 for patients who adhered to olanzapine treatment. Supplementary S7 shows further figures and exploratory results.

Fig. 2.

EDE-Q Global score over time in people who adhered to olanzapine. The graph corresponds to a mean decrease of 0.07 EDE-Q Global score (0.04, 0.09 95% CI) per week

Fig. 3.

BMI over time in people who adhered to olanzapine. This graph corresponds to a mean increase of 0.08 kg/m2 (0.06, 0.11 95% CI) per week in those who adhered to olanzapine

Olanzapine levels were only measured in 4 participants. Their mean serum level was 14 ng/ml (see Supplementary S8).

Discussion

In summary, only 20 of the 55 potential participants could be included into the study, only 13 of these 20 participants (65%) completed the trial up till 6 or 12 months. Thus, the study failed to meet the recruitment target and showed low adherence rates for treatment with olanzapine. Reluctance of patients to agree to olanzapine [7] and the low adherence rates [8] have been reported in previous studies.

Participants who were recruited into the trial showed on average an improvement in their ED psychopathology as measured using the EDE-Q Global score as well as an increase in BMI of 0.08 kg/m2 per week. Thus, the BMI increase in our study and in the RCT reported by Attia et al. [8] was ∼ 0.3 kg/m2 per month.

There are several potential reasons why this feasibility study did not recruit the envisaged number of patients. Firstly, the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic when inpatient and daycare services had reduced numbers of therapy places and outpatient services worked mainly remotely. This situation led to fewer patients who could be approached in person and recruited for the study. Another consequence of the pandemic was that clinical services for people with EDs were overwhelmed because many staff members were on sick leave or deployed (e.g., to vaccination hubs or specialised COVID-19 services), with some ED services having half their positions vacant. Therefore, staff may have prioritised clinical needs over research with the consequence that recruitment, booking appointments for follow-up assessments, completion of all examinations and questionnaires at each time point, and the documentation of results may have been affected. The current study included laborious baseline measurements (e.g. physical examinations, ECG, blood tests and questionnaires) which, taken together, meant a significantly bigger effort than the usual clinical prescription of olanzapine.

Secondly, the inclusion and exclusion criteria of this feasibility study may have been too strict. Notably, the narrow age range (12–24 years) was not helpful for recruitment: Several people with AN who were older than 24 years had asked to be part of the study but could not be included. In terms of exclusion criteria, there was reluctance to do a pregnancy test or to take contraceptive measures. Some clinicians felt that the topic of sexuality, reproduction and contraception was difficult to address with children and adolescents. Another example is that there were a handful of agitated and anxious patients who were eligible in principle and considered for the study, but their clinicians felt that they should commence olanzapine on the same day. As these people would not have had the required time to consider study participation, they were not included. The study protocol required that all baseline measurements were performed before olanzapine was started. Some ED services did not have the necessary equipment immediately available, and waiting for these results would have led to a delay in the start of olanzapine.

Thirdly, olanzapine is known to lead to weight gain, and patients with AN fear this particular side effect of medication [32] as it relates to their core psychopathology [33]. The information about weight gain as a side effect of olanzapine is freely available on the internet, textbooks and the relevant product information. A previous survey among patients with AN showed that many have concerns about potential weight gain, increased appetite, changes in body shape and metabolism during psychopharmacological treatment; and most think that medication should help with anxiety, concentration, sleep problems and anorexic thoughts rather than weight gain [32].

Three of the 10 sites did not consent any participants, while other sites were able to do so. Potential reasons are different pressures on the health care providers and their research and development departments, the number of potentially eligible patients in each service, and the different availability of assessments (e.g., ECT or olanzapine serum concentration measurement). However, it remains speculative whether a higher number of study sites with easy access to the necessary assessments for this study might have led to higher recruitment rates.

We had embedded a qualitative study into OPEN to understand clinicians’ views and experiences of using olanzapine in AN and the challenges in implementing the trial in clinical settings. This study identified four main themes spanning acknowledgment of patient/family concerns, prioritisation of person-centred care, limited service capacity, and the strict study eligibility criteria, thus providing valuable insight into individual and systemic challenges with implementing a feasibility study with olanzapine for AN [34].

Current scientific knowledge about antipsychotic-induced weight gain is mainly based on studies in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder [35]. However, even drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia have a higher risk to develop a metabolic syndrome [36]; whereas AN has been reported to have genetic correlations with fat mass, BMI, type 2 diabetes, fasting insulin and insulin resistance [37]. A recent network meta-analysis comparing physiological effects of antipsychotic drugs in children and adolescents with neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental conditions identified an acute treatment for a median duration of seven weeks with olanzapine increased BMI by 1.24 kg/m2 [38]. Thus, the risk for metabolic side effects and the mechanisms that lead to weight gain or metabolic changes under olanzapine might differ between patient groups.

However, most alternative medications in AN have been used and tested in the past because of their ability to help with weight recovery. The cannabinoid receptor agonist dronabinol, for example, showed efficacy regarding weight gain in a cross-over RCT [39, 40]. Likewise, for the atypical antipsychotic drug aripiprazole, several case series [41–43] and two retrospective case-controlled studies [44, 45] have reported successful treatment in AN. There is also evidence from a single small RCT with lithium [46] that this led to weight gain but not to changes in ED psychopathology.

Data on pill return was missing in most cases. We believe that pill count by a clinician or the monitoring of prescription charts would have been a more successful measure of concordance, particularly for inpatients. However, most study participants were already outpatients at inclusion or became outpatients during the study. For outpatients, it might have been too difficult to remember to keep their old pill films over several weeks or and bring them to the next assessment. Often, the medication was prescribed by GPs and dispensed by local pharmacists. However, in a future RCT, it might be easier to monitor adherence by centralising the dispensing of medication.

Novel psychopharmacological approaches to treat AN are the typical psychedelic psilocybin [47], , which has shown safety, tolerability and beneficial effects on ED psychopathology in a small feasibility study in AN [48], and the atypical psychedelic ketamine [49], which might have benefits on depressive and ED symptoms in people with AN [50]. These two psychedelics have the advantage that they do not immediately lead to weight gain, a side effect that may have deterred patients with AN from taking olanzapine in this study.

Novel biological, but non-pharmacological, treatment approaches for people with AN include different forms of non-invasive brain stimulation and deep brain stimulation with evidence from small RCTs for the efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation regarding mood, anxiety and ED psychopathology [51].

As there are novel biological treatment options for further investigation in AN, such as psilocybin and ketamine, as well as non-invasive brain stimulation treatments on the horizon, olanzapine may not be the preferred medication for people with AN and their clinicians. However, these treatments are currently labour- and cost-intensive because patients either have to be observed for long periods of time in a clinical setting for safety reasons or they receive psychedelic-assisted therapy for several hours per dosing session. Thus, olanzapine may still be considered by clinicians as a treatment option for AN.

Although monitoring of serum concentrations of olanzapine was part of the study as a compliance and safety measure, olanzapine levels were only measured in 4 participants as this proved difficult for the trial sites as this is not part of standard practice. Nonetheless, monitoring of olanzapine serum concentrations has been suggested to increase the safety of olanzapine treatment, and a preliminary therapeutic reference range between 11.9 and 39.9 ng/mL has been suggested for adolescents with AN [52]. The mean level of the 4 participants where olanzapine was measured in the serum was 14 ng/ml which is at the lower end of this reference range.

Conclusions

Our open feasibility study to test olanzapine in young people with AN failed to recruit enough patients, and the adherence rate was lower than expected. The reluctance of patients to agree to olanzapine [7] and the low adherence rates [8] have been reported in previous studies. Therefore, an RCT to test olanzapine would need a higher recruitment effort, and the expectations regarding adherence should be reduced.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Consort Checklist.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NIHR Research Design Service London for their advice on study design. We also thank the members of the Data Monitoring Committee (John Roche, Charlotte Scott, Rebecca Woolley) and the Trial Steering Committee (Helen E. Bould, Paul Robinson, Michael Kluge, Stephany Fulda, Jessica Bentley, Aylin Unlu) for contributing their time and valuable expertise to the oversight of the project. We would like to thank all colleagues from the participating NHS Trusts for their effort to recruit study participants; in particular, we would like to thank Paula Herrera-Gener, Camilla Day, Nikola Kern, Natalie Pretorius, Leola Cruden-Smith, Nacharin Phiphopthatsanee, Mutlu Tacihan Uygur, Camilla Mills, Annika Ray, Demelza Beishon-Murley, Carol Kan, Frances Connan, Rebecca Neale, Rosalind Byles, Rebecca Cowan, Elizabeth Fofana, Irene Bishton, Hazel Burt, Carla Figueiredo, Katarzyna Malczuk, Zofia Bronowska, Sam Clark-Stone, Francesca Hill, Elizabeth Dodd, Ruth Dawson and Lina Hamoudi. OPEN has a separate sister study planned in Australia, which aims to recruit 15 participants. The study was planned in two countries to allow for differences in healthcare systems and care processes to be explored. The study protocols are largely similar, with separate ethics approval, funding and sponsorship. The Australian part of the study was approved by the Sydney Children Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC reference 2021/ETH01321) on 20 September 2021 and has been funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). The sponsor is the University of Sydney. The current article refers exclusively to the OPEN study performed in the UK.

Abbreviations

- ALT

Alanine transaminase

- AN

Anorexia nervosa

- BAVQ-R

Revised Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire

- BMI

Body mass index

- CAA-SUS

Child, Adolescent and Adult Service Use Schedule

- DASS

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale

- DSM-5

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition

- ED

Eating disorder

- EDE-Q

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire

- EDSIS

Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- RCADS

Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- SREBQ

Self-Regulation of Eating Behaviour Questionnaire

- TAU

Treatment as usual

- WFSBP

World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry

Author contributions

HH, JT, US, BC, DS, MS, DS, SL, JB, AHY, SB, SM and VL planned the study design. OS, ESF, DS, HM, SB, MNA, VK, KI, ETB, DBM, JWTK, LA, JB, NK, BC, MS, VL, JT, US, DN and HH conducted the study. DS, BC, and SL evaluated the data. OS, ESF, DS and HH drafted the manuscript. All authors made contributions to the interpretation of the study results, were involved in the revision of the manuscript, participated in, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme (project reference NIHR130780). King’s College London (KCL) is the lead sponsor and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) is the cosponsor for this study. The sponsors act as data controllers.

This research was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre. US, JT, SL and HH receive salary support from NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) and KCL. SL is also supported by the Applied Research Collaboration (ARC), South London. DN is supported by the NIHR ARC Northwest London, and the NIHR Imperial BRC. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the National Health Service (NHS), the Department of Health and Social Care or the NHMRC. This work is also supported by the MRC/AHRC/ESRC Adolescence, Mental Health and the Developing Mind initiative as part of the EDIFY programme (grant number MR/W002418/1).

Data availability

Ethical approval and the obtained consent from study participants did not include public availability of the data. However, the data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

OPEN received a favourable Research Ethics Committee (REC) opinion from the Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland (ORECNI) on 10/03/2022; REC reference: 22/NI/0010; IRAS project ID: 295297. Before inclusion into the study, informed consent was obtained from each participant who was 16 years old or older. Children and adolescents who were younger than 16 years were asked to give their informed assent before inclusion into the study, and additional informed consent was obtained from their parents. We conducted this investigation following the Helsinki Declaration’s guiding principles. This study has been registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) register on the 27/04/2022 under the unique identification number ISRCTN80075010. Current Protocol version 1.3; 2 December 2022.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This manuscript reports results from anonymized data only.

Competing interests

HH is the Principal Investigator on “Efficacy and Safety of COMP360 Psilocybin Therapy in Anorexia Nervosa: a Proof-of-concept Study,” a COMPASS Pathways-funded and -sponsored proof-of-concept study testing psilocybin in AN. AHY participated in paid lectures and advisory boards for the following companies: Allegan, AstraZeneca, Bionomics Ltd, Boehringer Ingelheim, COMPASS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LivaNova, Lundbeck, Neurocentrx, Novartis, Sage, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, and Sunovion. AHY is the Principal Investigator in the Restore-Life VNS registry study funded by LivaNova; Principal Investigator on ESKETINTRD3004: ‘An Open-label, Long-term, Safety and Efficacy Study of Intranasal Esketamine in Treatment-resistant Depression’; Principal Investigator on ‘The Effects of Psilocybin on Cognitive Function in Healthy Participants’; Principal Investigator on ‘The Safety and Efficacy of Psilocybin in Participants with Treatment-Resistant Depression (p-TRD)’; UK Chief Investigator for Novartis MDD study MIJ821A12201. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Miskovic-Wheatley J, Bryant E, Ong SH, Vatter S, Le A, National Eating Disorder Research Consortium, Touyz S, Maguire S. Eating disorder outcomes: findings from a rapid review of over a decade of research. J Eat Disord. 2023;11(1):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gull WW. Anorexia nervosa (apepsia hysterica, anorexia hysterica) 1868. Obes Res. 1997;5(5):498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himmerich H, Treasure J. Psychopharmacological advances in eating disorders. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(1):95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergner L, Himmerich H, Steinberg H. Therapy of food refusal and anorexia nervosa in German-Language psychiatry textbooks of the past 200 years. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2022. 10.1055/a-1897-2330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brambilla F, Garcia CS, Fassino S, Daga GA, Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Ramaciotti C, Bondi E, Mellado C, Borriello R, Monteleone P. Olanzapine therapy in anorexia nervosa: psychobiological effects. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissada H, Tasca GA, Barber AM, Bradwejn J. Olanzapine in the treatment of low body weight and obsessive thinking in women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1281–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attia E, Kaplan AS, Walsh BT, Gershkovich M, Yilmaz Z, Musante D, Wang Y. Olanzapine versus placebo for out-patients with anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attia E, Steinglass JE, Walsh BT, Wang Y, Wu P, Schreyer C, Wildes J, Yilmaz Z, Guarda AS, Kaplan AS, Marcus MD. Olanzapine versus placebo in adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):449–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spettigue W, Norris ML, Maras D, Obeid N, Feder S, Harrison ME, Gomez R, Fu MC, Henderson K, Buchholz A. Evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of olanzapine as an adjunctive treatment for anorexia nervosa in adolescents: an open-label trial. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(3):197–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kafantaris V, Leigh E, Hertz S, Berest A, Schebendach J, Sterling WM, Saito E, Sunday S, Higdon C, Golden NH, Malhotra AK. A placebo-controlled pilot study of adjunctive olanzapine for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21:207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Himmerich H, Lewis YD, Conti C, Mutwalli H, Karwautz A, Sjögren JM, Uribe Isaza MM, Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor M, Aigner M, McElroy SL, Treasure J, Kasper S, WFSBP Task Force on Eating Disorders. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines update 2023 on the pharmacological treatment of eating disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2023;24(8):643–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Said O, Sengun Filiz E, Stringer D, Applewhite B, Kellermann V, Mutwalli H, Bektas S, Akkese MN, Kumar A, Carter B, Simic M, Sually D, Bentley J, Young AH, Madden S, Byford S, Landau S, Lawrence V, Treasure J, Schmidt U, Nicholls D, Himmerich H. Olanzapine for young PEople with aNorexia nervosa (OPEN): a protocol for an open-label feasibility study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2024;32(3):532–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, Croce E, Soardo L, Salazar de Pablo G, Il Shin J, Kirkbride JB, Jones P, Kim JH, Kim JY, Carvalho AF, Seeman MV, Correll CU, Fusar-Poli P. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):281–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nazar BP, Gregor LK, Albano G, Marchica A, Coco GL, Cardi V, Treasure J. Early response to treatment in eating disorders: a systematic review and a diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2017;25:67–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Research (NICE). Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. Last updated: December 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69. [Accessed: 14/10/2024].

- 16.Halvorsen I, Tollefsen H, Rø Ø. Advances in eating disorders. Rates of weight gain during specialised inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. Adv Eat Disord. 2016;4(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization (WHO). The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Last updated: January 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924159938-2. [Accessed: 14/10/2024].

- 18.Luce KH, Crowther JH. The reliability of the eating disorder examination-self-report questionnaire version (EDE-Q). Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:349–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandwick P, Lees S, Birchwood M. The revised beliefs about voices questionnaire (BAVQ-R). Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:229–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boekaerts M, Maes S, Karoly P. Self-regulation across domains of applied psychology: is there an emerging consensus?’. Appl Psychol. 2005;54(2):149–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chorpita BF, Moffitt CE, Gray J. Psychometric properties of the revised child anxiety and depression scale in a clinical sample. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:309–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irish M, Dalton B, Potts L, McCombie C, Shearer J, Au K, Kern N, Clark-Stone S, Connan F, Johnston AL, Lazarova S, Macdonald S, Newell C, Pathan T, Wales J, Cashmore R, Marshall S, Arcelus J, Robinson P, Himmerich H, Lawrence VC, Treasure J, Byford S, Landau S, Schmidt U. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a ‘stepping into day treatment’ approach versus inpatient treatment as usual for anorexia nervosa in adult specialist eating disorder services (DAISIES trial): a study protocol of a randomised controlled multi-centre open-label parallel group non-inferiority trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gowers SG, Clark AF, Roberts C, Byford S, Barrett B, Griffiths A, Edwards V, Bryan C, Smethurst N, Rowlands L, Roots P. A randomised controlled multi-centre trial of treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa including assessment of cost-effectiveness and patient acceptability – the TOuCAN trial. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(15):1–98. 10.3310/hta14150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burstrom K, Cavrini G, Devlin N, Egmar AC, Greiner W, Gusi N, Herdman M, Jelsma J. Development of the EQ-5D-Y; a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):875–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sepulveda AR, Whitney J, Hankins M, Treasure J. Development and validation of an eating disorders symptom impact scale (EDSIS) for carers of people with eating disorders. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:28. 10.1186/1477-7525-6-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lingjærde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychatr Scand. 1987;76(Suppl 334):1–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jennings KM, Phillips KE. Eating disorder examination–questionnaire (EDE–Q): norms for clinical sample of female adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(6):578–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fairburn CG, Beglin S. Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE–Q 6.0). In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 309–14. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, Bond CM, Hopewell S, Thabane L, Lancaster GA. On behalf of the PAFS consensus group. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dessain A, Bentley J, Treasure J, Schmidt U, Himmerich H. Patients’ and Carers’ perspectives of psychopharmacological interventions targeting anorexia nervosa symptoms. In: Himmerich H, Jáuregui Lobera I, editors. Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa. London: IntechOpen; 2019. pp. 103–22. 10.5772/intechopen.86083 [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th text revision. Washington DC: APA Publishing; 2013.

- 34.Kellermann V, Sengun Filiz E, Said O, Bentley J, Khor JWT, Simic M, Nicholls D, Treasure J, Schmidt U, Himmerich H, Lawrence V. A feasibility trial of olanzapine for young people with anorexia nervosa (OPEN): clinicians’ perspectives. J Eat Disord. 2024;12(1):146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Himmerich H, Minkwitz J, Kirkby KC. Weight gain and metabolic changes during treatment with antipsychotics and antidepressants. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2015;15(4):252–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu S, Liu X, Zhang Y, Ma J. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its associated factors in first-treatment drug-naive schizophrenia patients: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2024. 10.1111/eip.13565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bulik CM, Carroll IM, Mehler P. Reframing anorexia nervosa as a metabo-psychiatric disorder. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021;32(10):752–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogdaki M, McCutcheon RA, D’Ambrosio E, Mancini V, Watson CJ, Fanshawe JB, Carr R, Telesia L, Martini MG, Philip A, Gilbert BJ, Salazar-de-Pablo G, Kyriakopoulos M, Siskind D, Correll CU, Cipriani A, Efthimiou O, Howes OD, Pillinger T. Comparative physiological effects of antipsychotic drugs in children and young people: a network meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2024;8(7):510–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andries A, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Støving RK. Dronabinol in severe, enduring anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andries A, Gram B, Støving RK. Effect of dronabinol therapy on physical activity in anorexia nervosa: a randomised, controlled trial. Eat Weight Disord. 2015;20(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trunko ME, Schwartz TA, Duvvuri V, Kaye WH. Aripiprazole in anorexia nervosa and low-weight bulimia nervosa: case reports. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44(3):269–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frank GKW. Aripiprazole, a partial dopamine agonist to improve adolescent anorexia nervosa a case series. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49(5):529–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tahillioglu A, Ozcan T, Yuksel G, Majroh N, Kose S, Ozbaran B. Is aripiprazole a key to unlock anorexia nervosa? A case series. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8(12):2827–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frank GKW, Shott ME, Hagman JO, Schiel MA, DeGuzman MC, Rossi B. The partial dopamine D2 receptor agonist aripiprazole is associated with weight gain in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(4):447–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marzola E, Desedime N, Giovannone C, Amianto F, Fassino S, Abbate-Daga G. Atypical antipsychotics as augmentation therapy in anorexia nervosa. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0125569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gross HA, Ebert MH, Faden VB, Goldberg SC, Nee LE, Kaye WH. A double-blind controlled trial of lithium carbonate primary anorexia nervosa. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1981;1(6):376–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spriggs MJ, Douglass HM, Park RJ, Read T, Danby JL, de Magalhães FJC, Alderton KL, Williams TM, Blemings A, Lafrance A, Nicholls DE, Erritzoe D, Nutt DJ, Carhart-Harris RL. Study protocol for psilocybin as a treatment for anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:735523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peck SK, Shao S, Gruen T, Yang K, Babakanian A, Trim J, Finn DM, Kaye WH. Psilocybin therapy for females with anorexia nervosa: a phase 1, open-label feasibility study. Nat Med. 2023;29:1947–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keeler JL, Treasure J, Juruena MF, Kan C, Himmerich H. Ketamine as a treatment for anorexia nervosa: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keeler JL, Treasure J, Himmerich H, Brendle M, Moore C, Robison R. Case report: intramuscular ketamine or intranasal esketamine as a treatment in four patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anorexia nervosa. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1181447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gallop L, Flynn M, Campbell IC, Schmidt U. Neuromodulation and eating disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022;24(1):61–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karwautz A, Zeiler M, Schwarzenberg J, Mairhofer D, Mitterer M, Truttmann S, Philipp J, Koubek D, Glüder M, Wagner G, Malcher A, Schöfbeck G, Laczkovics C, Rock HW, Zanko A, Imgart H, Banaschewski T, Fleischhaker C, Correll CU, Wewetzer C, Walitza S, Taurines R, Fekete S, Romanos M, Egberts K, Gerlach M. Therapeutic drug monitoring in adolescents with anorexia nervosa for safe treatment with adjunct olanzapine. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2024;32(6):1055–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Consort Checklist.

Data Availability Statement

Ethical approval and the obtained consent from study participants did not include public availability of the data. However, the data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.