Abstract

Background

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the use of a free online continuing education (CE) course that sought to address barriers of capability by training dental team members in the specific recommendations of the American Dental Association (ADA)-endorsed adult guideline for the pharmacologic management of acute dental pain, shared decision-making, and the adoption of the guideline into practice.

Methods

In 2022 and 2023, dentists completed an online, asynchronous CE course on the guideline-concordant pharmacologic management of acute dental pain. They completed 11-item knowledge tests before and after completing the course. Total scores on the pre- and post-tests were compared using a t-test.

Results

The mean score increased from 7.68 (SD = 1.08) on the pretest to 8.79 (SD = 1.35) on the post-test (t(4468) = -27.34, p < .01), indicating that dentists gained knowledge from the CE course.

Conclusions

We found that the CE course increased knowledge with respect to the guideline recommendations and shared decision-making but not epidemiology or incorporating a guideline into practice. Future studies should evaluate whether the CE course increased guideline-concordant prescribing.

Keywords: Practice guideline, Decision making, Shared, Clinical pharmacology, Dentists’ practice patterns, Educational assessment, Lifelong learning

Background

According to the COM-B model of behavior change [1], for a person to adopt a new behavior, three conditions need to be met. They must have the capability to engage in the behavior, which includes having relevant knowledge and skills. They must have the opportunity to engage in the behavior, which includes the social environment. And they must have the motivation to engage in the behavior, which includes having the desire to engage in the behavior. Dentists have the opportunity to manage acute dental pain. Dental pain arises from many diagnoses and procedures, including having a toothache and/or having a tooth removed. Furthermore, dentists can manage acute dental pain by multiple means, including both non-pharmacologic means, such as heat and ice, and pharmacologic means, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and opioid analgesics.

Dentists also have the motivation to manage acute dental pain. All dentists would prefer to choose the pain management intervention that offers the patient the largest benefit with the fewest adverse effects. Furthermore, many dentists have demonstrated that they have the motivation to manage acute dental pain without the use of opioids. With the onset of the opioid crisis in the United States, policy makers have been working to encourage all providers, including dentists, to manage acute dental pain using approaches other than opioids [2, 3]. These efforts have yielded results, with dentists demonstrating decreases over time in morphine milligram equivalents (MME) of opioids prescribed [4, 5].

Capability includes having the knowledge of how to manage acute dental pain. Recently, a team from the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Pennsylvania schools of dental medicine developed American Dental Association (ADA)-endorsed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the pharmacological management of acute dental pain arising from simple and surgical tooth extraction and toothache in children, adolescents, adults, and older adults [6, 7]. Unlike most existing clinical practice guidelines for the management of acute dental pain [3], these guidelines offer specific recommendations regarding medications, dosages, and durations. For dentists to implement these guidelines, they must learn the specifics of the recommendations, a component of capability. Furthermore, qualitative studies have shown that dentists face barriers of capability beyond knowledge of pain management approaches. These include not knowing how to talk to patients about pain management and how to say “No” to patient requests for opioid analgesics [8].

Continuing education (CE) courses are one way to increase providers’ knowledge about guidelines and address other barriers of capability. There are several ways in which CE courses are delivered, such as online (e.g., interactive text-based and multimedia activities), live (e.g., dinner meetings, workshops), and enduring (e.g., newsletters, mobile text-based activities) [9]. In a meta-analysis of over 600 CE medical programs, all of these methods demonstrated a moderate-to-large educational effect [9]. Furthermore, several systematic reviews of CE programs have shown that CE courses improve physician performance and patient health outcomes [10–12].

Online multimedia activities (e.g., slides with audio or recorded lectures) can have a comparable effect to live events [9]. Online CE courses have especially gained popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic. A study in Taiwan found online dental continuing education courses to be effective and accepted by providers during and after the height of the pandemic [13]. With socioeconomic constraints, oral health providers in rural and remote areas may have difficulty accessing quality educational resources. Online CE education courses can and have been found to be successful in reducing this disparity in access [11].

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate a free online CE course that addressed identified barriers of capability by training dentists and their staff in the recommendations of the ADA-endorsed adult guideline, shared decision-making, and incorporating a guideline into practice.

Methods

Human subjects protection

Human Ethics and Consent to Participate declarations: not applicable. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board determined that evaluating the effect of the CE course on change in oral health providers’ knowledge did not meet the criteria for human subjects research. The study conforms to STROBE Guidelines.

Participant recruitment

To prevent contamination of our results from exposure to the adult guideline, we made the CE course available to oral health providers before the adult guideline became publicly available in February 2024 [7].

We adopted several approaches to publicize the course. In collaboration with the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD), beginning in the summer of 2021, we contacted the state dental directors in Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, Montana, and Oregon. These states were chosen because they had high rates of opioid prescribing and represented diverse geographic regions of the country. In October 2021, we sent each of the five state dental directors a Qualtrics survey (Seattle, WA and Provo, UT) addressing how best to promote the CE course to oral health providers in their states. Based on those results, in December 2021, the ADA developed and distributed promotional materials to the state dental associations and dental societies in those five states including flyers and language for emails, newsletters, and social media. Oral health providers could sign up to receive an email when the course went live.

After the CE course launched, the ADA sent an email with the course link to all oral health providers who were on record with the ADA in the five states and distributed a “word of mouth” toolkit to colleagues in the five states. The toolkit included language for social media, emails, and newsletters. In December 2022, the ADA added language to the toolkit that saying that the CE course increased knowledge for most oral health providers who took the course. ASTDD distributed this revised toolkit to dental directors and colleagues in the five states. Finally, in April 2023, the ADA publicized the course to all its members.

The CE course

The CE course was a 1-hour pre-recorded video [14]. The primary purpose of the CE course was to provide dentists and other oral health providers information about the recommendations included in the adult guideline. Following a 4 min introduction, the first three slides provided speaker disclosures and background information. Epidemiological information about opioid prescribing was provided on the next nine slides. The subsequent 25 slides presented goals, caveats, and the methodology used for the guideline development as well as examples of the recommendations from the adult guideline. The recommendations included the first- and second-line approaches to managing acute dental pain resulting from surgical tooth extractions for adolescents, adults, and older adults, as well as the roles of opioids, bupivacaine, and corticosteroids following surgical tooth extraction. The Good Practice Statements from the guideline were also included. The speaker for this section was selected because he is a recognized authority on the topic, and authority is an element of effective persuasion [15]. This information was presented over 34 min.

Provider-level barriers to implementing the guideline

In addition to providing information about the recommendations included in the adult guideline, the CE course also targeted provider-level barriers to implementing the guideline. To identify the barriers to target, in the summer of 2021 we convened two focus groups, with five members in the first group and 6 in the second group, drawn from participants on the guideline panel who were willing and available on at least one of the days and times of the focus groups. To start, each member of the focus groups listed their top three challenges related to clinical decision-making about acute dental pain management. Then, together, the focus groups ranked the challenges by their importance. Next, the focus groups ranked the challenges by their difficulty in being addressed. Each challenge was then plotted on two-dimensional graph by its importance and difficulty. Based on the results of the importance-by-difficulty matrix, we decided to target dentists’ communication skills and their skills in incorporating a guideline into practice, which the focus groups had determined to be important but not difficult to be addressed.

To address barriers relating to communication, based on the United States’ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s SHARE approach to shared decision-making [16], we developed a five-step approach to patient communication around acute dental pain management (Table 1). To make sure the steps were appropriate for our target audience of dentists and other members of the dental team, we developed this content with a team that included a senior teaching consultant in Pedagogy, Practice, and Assessment and a consultant with expertise in translating complex, scientific content into messaging that is clear, concise and compelling. We obtained feedback on the steps and slides from two dentists and a dental hygienist iteratively until the material was clear. In the video recording of the course, this information was presented on 15 slides over 14 min.

Table 1.

Five steps of shared decision-making

| Step | Skill |

|---|---|

| 1 | Let the patient know you need their involvement in the decision about pain management |

| 2 | Ask about factors that may influence the options available to your patient |

| 3 | Explore the patient’s understanding of and preferences for pain management options |

| 4 | Share the pain management options that are available |

| 5 | Reach a mutually agreeable decision about pain management |

To address barriers related to implementing a guideline in practice, we recommended oral health providers conduct mini-experiments by applying the recommendations with their patients and seeing what happens [17]. In the video recording of the course, this information was presented on three slides over 4 min. Finally, the course was summarized in 2 min.

Supporting materials

To complement the presentation, we also provided links to evidence-based screening tools for adult and adolescent substance use including opioids [18]; a tip sheet for storing medications away from children [19]; information on the safe disposal of drugs [20]; a link to Prescription Drug Monitoring Program information by state [21]; information about communicating with pediatric patients [22]; and a journal article on communication strategies used during pediatric dental treatment [23].

Procedure

Clinical trial number: not applicable. The course launched in July 2022 on the ADA’s online CE learning management system (Aptify, v6.0, CommunityBrands, St. Petersburg, Florida) and was free to anyone, regardless of ADA membership status. Learners could obtain 1 ADA CERP credit.

Oral health providers received a link to the CE course Web site, which included the course title page, an overview, learning objectives, funding statement, and speaker biographies. They then completed an optional pre-test (Qualtrics, Seattle, WA and Provo, UT). Following the pretest, they viewed the CE course video and completed the post-test (Aptify, v. 6.0, CommunityBrands, St. Petersburg, Florida). It was not possible for oral health providers to access the post-test without first viewing the video. To receive an ADA CERP credit, they had to answer at least 80% of the post-test questions correctly. They could take the post-test as many times as they wanted to. Because the pre- and post-tests were delivered on different platforms, there was no way to link them.

Measures

The pre- and post-tests each comprised 11 items that were each summed into a total score. Although the questions on the pre- and post-tests were not identical, the same concepts were tested. The first two items assessed the learner’s knowledge about the epidemiology of opioid use in the U.S. The next four items assessed the learner’s knowledge about pharmacological approaches to managing acute dental pain. All these items were measured using a true-false response set. Four of the five remaining items assessed the learner’s shared decision-making communication skills, and the remaining item assessed the learner’s knowledge of how to incorporate a guideline into practice. Four of the final five items were assessed using multiple choice options, and the remaining item was assessed using a true-false response set. To ensure the test questions were clear and to reduce non-response bias, we screened the questions with a fourth-year dental student, two dentists, a dental hygienist, and a senior teaching consultant in Pedagogy, Practice, and Assessment and iteratively revised them until they were clear. Although we obtained course evaluation ratings, we did not include those results in this paper because they do not inform the research question.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the effect of the course on the learner’s knowledge and because learners could take the post-test as many times as they wanted, we analyzed only the first post-test score from each participant. Statistical analysis was conducted on participants who completed at least 80% of either test. Missing data were left missing. Because we could not link pretest scores to post-test scores, we used an independent t-test to compare the pretest scores with the post-test scores. We used frequencies to evaluate the effect size. Accuracy, including whether those who responded differed from those who did not, is determined by comparing the results with external criteria. To enable the assessment of selection bias, we obtained the gender, age, race/ethnicity, employment, and specialty training of U.S. dentists [24]. Due to the large sample sizes, which could result in statistically but possibly not meaningfully significant results, we did not conduct statistical analyses of differences in frequencies between U.S. dentists and either pre- or post-test takers.

Results

Because the pre-test was optional, some learners did not take it. A total of 2,042 and 3,061 learners began the pre- and post-tests, respectively. Of those, 1,418 (65.4%) and 3,052 (95.7%) learners completed at least 80% of the pre- and post-tests, respectively. Demographic characteristics of the learners and U.S. dentists can be found in Table 2. Compared with learners who completed at least 80% of the post-test, a greater percentage of women and a lower percentage of men completed at least 80% of the pretest. The gender distribution of the learners taking the post-test was similar to that of U.S. dentists. In addition, Pediatrics, Periodontics, and Endodontics may have been over-represented among our learners, and Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics may have been under-represented. Dental Anesthesiology was not represented among the learners.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of learners and US dentists

| Pre-test | Post-test | US Dentists, 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (1,418) | % | n (3,052) | % | % |

| Gendera | |||||

| Male | 714 | 51% | 1849 | 61% | 61% |

| Female | 609 | 43% | 1203 | 39% | 38% |

| Other | 7 | 0.5% | |||

| Prefer not to answer | 80 | 6% | |||

| Ageb | |||||

| 18–24 | 6 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.1% | |

| 25–34 | 326 | 23% | 474 | 16% | 17.4 (under 35) |

| 35–44 | 395 | 28% | 815 | 27% | 26% |

| 45–54 | 280 | 20% | 685 | 22% | 22% |

| 55–64 | 215 | 15% | 569 | 19% | 19% |

| 65–74 | 106 | 8% | 321 | 11% | 16% (65 and older) |

| 75–84 | 14 | 1% | 51 | 2% | |

| Over 85 | 2 | 0.1% | 2 | 0.1% | |

| Prefer not to answer | 45 | 3% | 134 | 4% | |

| Ethnicityc | |||||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino/ Spanish origin | 1187 | 85% | |||

| Hispanic/Latino/ Spanish origin | 79 | 6% | |||

| Prefer not to answer | 135 | 10% | |||

| Racec | |||||

| White | 913 | 65% | 67% | ||

| Asian | 244 | 17% | 20% | ||

| Black or African American | 19 | 1% | 3% | ||

| Other | 32 | 2% | |||

| Prefer not to answer | 193 | 14% | |||

| Employment | |||||

| General Dentist | 1142 | 81% | 2993 | 98% | 78% |

| Specialty Training | 206 | 14% | 22% | ||

| Dental hygienist | 14 | 1% | 14 | 0.5% | |

| Not currently working | 13 | 1% | |||

| Other | 43 | 3% | 45 | 1% | |

| Specialty Training | |||||

| Pediatric Dentistry | 56 | 27% | 21% | ||

| Periodontics | 43 | 21% | 13% | ||

| Endodontics | 34 | 16% | 13% | ||

| Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | 39 | 19% | 17% | ||

| Prosthodontics | 14 | 7% | 8% | ||

| Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics | 12 | 6% | 25% | ||

| Other | 8 | 4% | 4% | ||

| Years since dental trainingd | |||||

| 0–5 | 311 | 22% | 886 | 3% | |

| 6–10 | 257 | 18% | 377 | 15% | |

| 11–15 | 181 | 13% | 300 | 12% | |

| 16–20 | 155 | 11% | 288 | 11% | |

| 21–25 | 155 | 11% | 246 | 10% | |

| 26–30 | 99 | 7% | 199 | 8% | |

| 31–35 | 106 | 8% | 160 | 6% | |

| 36–40 | 76 | 5% | 77 | 3% | |

| Over 40 years | 71 | 5% | 29 | 1% | |

Note

aOn the pretest, gender was not answered by 8 learners

bOn the pretest, age was not answered by 29 learners

cOn the pretest, ethnicity and race were not answered by 17 learners

dYears since dental training was not answered by seven learners on the pre-test and by 490 learners on the post-test

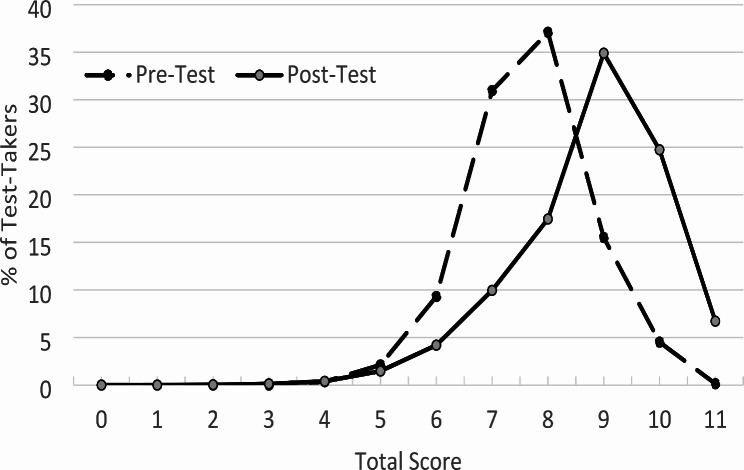

The mean knowledge score increased from 7.68 (SD = 1.08) on the pretest to 8.79 (SD = 1.35) on the post-test (t(4468) = -27.34, p < .01; Table 3; Fig. 1). A breakdown of performance by item is shown in Table 4. On the pretest, the percentage correct per item ranged from 7.48 to 99.37%. On the post-test, the percentage correct per item ranged from 32.79 to 99.67%. As can be seen (Table 4), before taking the course, many learners were familiar with the epidemiology of opioids and prescribing recommendations. Fewer learners were familiar with concepts associated with shared decision-making or incorporating a guideline into practice. Following exposure to the course, the percentage correct increased from the pretest to the post-test on items assessing pharmacological approaches to pain management and shared decision-making but not epidemiology or incorporating a guideline into practice.

Table 3.

Distributional characteristics of pre- and post-test total scores

| Pre-test n = 1,418 |

Post-test n = 3,052 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 7.7 | 8.8 |

| Median | 8 | 9 |

| Mode | 8 | 9 |

| Standard deviation | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Range | 4–11 | 2–11 |

| Skewness | -0.1 | -0.8 |

| Kurtosis | 0.3 | 0.9 |

Fig. 1.

Frequency distributions of the pre- and post-test total scores. Note. Learners passed the test if they answered at least 80% of the questions (i.e., 9 questions) correctly. Although learners could take the post-test more than once, the post-test scores reported are from the first test the learners took.

Table 4.

Performance by item on pre- and post-tests

| Correct responses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-testa | ||||

| Item | Category | N = 1,418 | % | N = 3,052 | % |

| Q1 | Epidemiology | 1,316 | 93% | 2,947 | 97% |

| Q2 | Epidemiology | 1,268 | 89% | 2,460 | 81% |

| Q3 | Pharmacologic approaches | 1,407 | 99% | 2,816 | 92% |

| Q4 | Pharmacologic approaches | 1,375 | 97% | 2,332 | 76% |

| Q5 | Pharmacologic approaches | 559 | 39% | 2,582 | 85% |

| Q6 | Pharmacologic approaches | 1,409 | 99% | 3,042 | 99.7% |

| Q7 | Shared decision-making | 1,286 | 91% | 3,037 | 99.5% |

| Q8 | Shared decision-making | 1,020 | 72% | 2,724 | 89% |

| Q9 | Shared decision-making | 106 | 7% | 2,471 | 81% |

| Q10 | Adopting a guideline | 900 | 63% | 1,427 | 45% |

| Q11 | Shared decision-making | 239 | 17% | 999 | 33% |

Note. aAlthough learners could take the post-test more than once, the post-test scores reported are from the first test the learners took.

Discussion

This project sought to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of an asynchronous, online CE course to overcome barriers of capability regarding the recommendations of the ADA-endorsed clinical practice guideline on the management of acute dental pain in adults, shared decision-making, and incorporating a guideline into practice. We found that the CE course increased overall knowledge. Specifically, it increased knowledge about the prescribing recommendations and shared decision-making but did not increase knowledge about incorporating a guideline into practice.

On average, scores increased from the pretest to the post-test by one point. Because learners had prior knowledge about six of the 11 questions, only five of the questions had the potential to demonstrate an increase in knowledge. Thus, the 1-point increase corresponds to a 20% increase in knowledge. Although this increase is statistically significant, until we assess change in behavior, it is unknown whether this increase is clinically meaningful. Learners’ increase in knowledge was limited to the two topics on which more time was spent in the course. In the course, the least amount of time was spent on how to incorporate a guideline into practice, and learners did not increase their knowledge in this area. The brevity of this particular component may have limited its effectiveness. Adding interactive components or case-based learning may be effective. Future research should examine this issue. We also observed that scores on four questions decreased from the pretest to the post-test. We assume that the decline in performance on these items indicates confusing or poorly written questions. Although we pretested the questions with volunteers who were similar to the learners, this may not have been sufficient.

According to Knowles [25], there are six principles that optimize learning for adults. First, adult learners seek to understand why they need to learn something. To address this principle in our CE course, we began by framing the topic as one of providing a new approach to managing their patients’ acute dental pain — one that best balances benefits and harms.

Second, adults’ motivation to learn is stronger when it comes from themselves (i.e., intrinsic) rather than from an external source (i.e., extrinsic). This principle suggests that learners should learn about guidelines because they are intrinsically interested in the topic and not because they are required to learn the material. As of June 27, 2023, however, the U.S. Congress, through the Medication Access and Training Expansion Act, began requiring all new and renewing licensees of the Drug Enforcement Administration to complete eight hours of training on opioid or other substance use disorders and the appropriate treatment of pain. Thus, thought should be given to how to engage intrinsic motivation around this topic. To address this principle in our CE course, we presented epidemiological data demonstrating the harms associated with opioids.

Third, adult learners prefer to be responsible for their own learning. To address this principle, we structured our CE course as an asynchronous online course. This structure enables learners to engage autonomously with the course. Fourth, adult learners prioritize learning information that is immediately applicable to their lives. Simple or surgical extractions or managing a toothache, which cause acute dental pain, are procedures commonly conducted by dentists. Thus, the course was most likely immediately applicable to them.

Our study had some limitations. First, according to Knowles, the foundation of adult learning lies in the learners’ prior experiences. We could have structured the course to enable learners to consider what they already knew before providing them with new information. Had we engaged prior experience, we also could have linked their prior experience to the new information. And second, according to Knowles, adults learn better when they are focused on solving problems rather than learning content. We could have done a better job framing the content as problems to be solved. Thus, although our course manifested many elements of adult learning principles, we see room for improvement.

Although comparing a pretest score with a posttest score is an appropriate way to measure changes in knowledge, it is a one-time test of knowledge gains. Without follow-up, there is no way to determine how well participants retained or implemented what they learned. Additionally, the passive nature of an online, asynchronous didactic session and the fact that the course was short may have also contributed to the lack of knowledge increase on the question about incorporating the guideline into practice. Third, there is the potential for self-selection bias and limits to generalizability if the learners who chose to complete the course and tests had more knowledge or interest in the topic than those who didn’t choose to participate. For example, dentists practicing Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics may have been under-represented. Finally, fewer learners completed the pre-test compared with the post-test, and we were unable to compare pre- and post-tests by learner, which limits the conclusions we can draw.

This study had several strengths. Given our large sample sizes, we can have confidence in the precision of our estimates. In addition, the dentists who took the course and completed the pre- and post-tests were similar in gender, age, and race to dentists in the U.S., suggesting that our results could generalize to U.S. dentists overall. Finally, the online, asynchronous format and the fact that the course was free made it accessible to a broad audience. It can be challenging to reach providers in solo and small practices. Online asynchronous CE courses can be one way to reach these dentists.

CE courses supporting the dissemination of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines are just one component of an infrastructure associated with the ongoing shift by oral health providers to evidence-based practice. This infrastructure includes but is not limited to the guidelines themselves, which have to be developed; endorsements by associations seen as authorities by dentists; metrics to measure guideline-concordant practice; support from payers for guideline-concordant practice; and training, including training for students in dental schools and for providers already in practice. The development of each element requires different responsible parties with different skill sets. Unfortunately, the parties responsible for developing CE courses supporting evidence-based clinical practice guidelines have not been clearly identified. This means that published guidelines sometimes lack associated and broadly available CE courses (e.g., the ADA guidelines on antibiotic stewardship). Thought should be given to clarifying whose responsibility it is to develop CE courses once an evidence-based clinical practice guideline has been developed.

In summary, we found that the CE course designed to disseminate the 2024 ADA-endorsed evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the management of acute dental pain in adults increased knowledge with respect to the recommendations and shared decision-making. Although online CE courses have been found to be effective, some studies have found that the passive nature of didactic sessions fail to significantly impact patient care [26]. For this reason, future studies should evaluate whether the CE course increased guideline-concordant prescribing.

Acknowledgements

Megan E. Hamm and Neil Kenkre provided assistance with the focus groups. Lindsay Onufer and Samuel Zwetchkenbaum provided assistance in developing the components of the communication skills, and Hana Mujkovic, provided assistance in designing the pre- and post-tests.

Author contributions

DEP contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition and interpretation of data, and drafted the work. ANR contributed to the analysis of the data and drafted the work. BA contributed to the conception and design of the study. FC contributed to the acquisition of the data. BI contributed to the conception and design of the study and the acquisition of the data. MJ contributed to the design of the study and the acquisition of the data. NHS contributed to the design of the study and analysis and interpretation of the data. PAM contributed to the conception and design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project was financially supported by grant U01FD007151 from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, the FDA, Department of Health and Human Services, or the US government. The funders had no decision-making role in designing and conducting the CE course, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. FDA staff provided nonbinding feedback to the authors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human Ethics and Consent to Participate declarations: not applicable. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board determined that evaluating the effect of the CE course on change in oral health providers’ knowledge did not meet the criteria for human subjects research. IRB# 2112013.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ information

As Chair of the RESPITE study’s “Clinical Practice Guidelines Panel,” Dr. Moore provided content expertise for the guideline development methods and the creation of presentation materials used for this CE program.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: a Guide to Designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain - United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khouja T, Shah NH, Suda KJ, Polk DE. Trajectories of opioid prescribing by general dentists, specialists, and oral and maxillofacial surgeons in the United States, 2015–2019. J Am Dent Assoc (1939). 2024;155(1):7–16. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan CH, Lee TA, Sharp LK, Hubbard CC, Evans CT, Calip GS, et al. Trends in Opioid Prescribing by General dentists and Dental specialists in the U.S., 2012–2019. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(1):3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrasco-Labra A, Polk DE, Urquhart O, Aghaloo T, Claytor JW Jr., Dhar V et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic management of acute dental pain in children: A report from the American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, and the Center for Integrative Global Oral Health at the University of Pennsylvania. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2023;154(9):814 – 25 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Carrasco-Labra A, Polk DE, Urquhart O, Aghaloo T, Claytor JW Jr., Dhar V et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic management of acute dental pain in adolescents, adults, and older adults: A report from the American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, the University of Pittsburgh, and the University of Pennsylvania. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2024;155(2):102 – 17 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Yan CH, Ramanathan S, Suda KJ, Khouja T, Rowan SA, Evans CT et al. Barriers to and facilitators of opioid prescribing by dentists in the United States: A qualitative study. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2022;153(10):957 – 69 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Salinas GD. CME effectiveness: utilizing outcomes assessments of 600 + CME programs to evaluate the association between format and effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(Suppl 1):S38–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Ansari A, Nazir MA. Dentists’ responses about the effectiveness of continuing education activities. Eur J Dent Educ. 2018;22(4):e737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Wei X, Zhou L, Zhu EF, Xu Y. The effectiveness of continuing education programmes for health workers in rural and remote areas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rural Remote Health. 2023;23(4):8275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cervero RM, Gaines JK. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(2):131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng FC, Tang LH, Lee KJ, Wei YF, Liu BL, Chen MH, et al. Online courses for dentist continuing education: a new trend after the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent Sci. 2023;18(4):1812–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore PA, Polk DE. Clinical practice guideline for management of acute dental pain Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2023 https://engage.ada.org/courses/295/view

- 15.Cialdini RB. Influence. The psychology of persuasion. Harper Business; 2021.

- 16.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. SHARE approach workshop Rockville, MD2021 [updated February, 2021. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/workshop/index.html

- 17.Armstrong D. Clinical autonomy, individual and collective: the problem of changing doctors’ behaviour. Social science & medicine (1982). 2002;55(10):1771-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Screening tools and prevention: National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2023 [updated January 6, 2023; cited 2024 May 28]. https://nida.nih.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/screening-tools-prevention

- 19.Safe medicine storage for. Parents: UpAndAway.org; [cited 2024 May 28]. https://upandaway.org/en/resource/up-and-away-tip-sheet-2/

- 20.Digital Communications Division. How to safely dispose of drugs [updated December 16, 2022; cited 2024 May 28]. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/prevention/safely-dispose-drugs/index.html

- 21.State PDMP. profiles and contacts: Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Training and Technical Assistance Center; [cited 2024 May 28]. https://www.pdmpassist.org/State

- 22.Waldron R. Communicating with pediatric patients before, during and after appointments: Colgate; [updated September 24, 2018; cited 2024 May 28]. https://www.colgateprofessional.com/dentist-resources/patient-care/communicating-pediatric-patients#

- 23.Sarnat H, Arad P, Hanauer D, Shohami E. Communication strategies used during pediatric dental treatment: a pilot study. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23(4):337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.HPIData_Supply_of_Dentists_2023 [Internet]. American Dental Association. 2024 [cited April 19, 2024]. https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/hpi/hpidata_supply_of_dentists_2023.xlsx?rev=fe9e8a179d424050a72def0fddc19389&hash=F41FC950BB22E5D26F857C5E31564091

- 25.Knowles MS. The modern practice of adult education: from pedagogy to andragogy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall/Cambridge; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiener RC, Waters C, Bhandari R, Trickett Shockey AK, Panagakos F. U.S. Re-licensure Opioid/Pain Management Continuing Education requirements in Dentistry, Dental Hygiene, and Medicine. J Dent Educ. 2019;83(10):1166–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.