Abstract

Background

The complications associated with cardiac device implants ranges between 5.3% and 14.3%. Cardiac perforation due to “leads” represent a very rare complication of cardiac device implantation, ranging between 0.3% and 0.7%. Clinically, they can manifest different, nonspecific symptoms; hence, the diagnosis may not be immediate.

Case presentation

Our clinical case describes the successful treatment of cardiac tamponade occurring in a Caucasian 79-year-old man following a pacemaker implantation. Two days after the procedure, the patient reported an episode of nonspecific chest pain associated with syncope. The echocardiogram performed revealed a pericardial effusion in the apical area, along the right chambers, with a thickness of 7 mm, not hemodynamically significant. A chest computed tomography scan with contrast showed hemopericardium (maximum thickness of 11 mm), caused by an atrial perforation. A few hours later, the patient experienced hemodynamic instability. For this reason, an urgent sternotomy was performed with drainage of a significant hemopericardial effusion, revealing a perforation of the upper free wall of the right atrium with pericardial injury caused by the retractable screw lead. The perforation site was sutured and the sternal wound was closed. The patient was discharged after 4 days without further complications. At the control visit, scheduled 30 days after the hospital discharge, the patient was in good conditions.

Conclusions

Although the atrial perforations from leads are very rare complications of pacemaker implantation procedures, they are potentially lethal. In conclusion, this clinical case highlights the need, before hospital discharge, of an accurate screening for evaluation the pericardial effusion in patients that undergo to the cardiac implantable electronic devices.

Keywords: Cardiac tamponade, Pericardial effusion, Cardiac surgery, Ecocardiography, Case report

Introduction

Complications related to cardiac device implants ranges between 5.3% and 14.3%. Cardiac perforations due to “leads” represent a very rare complication of device implantation, occurring between 0.3% and 0.7% [1, 2], although the prevalence may be higher. Acute perforations (occurring during or within 24 hour of implantation) and subacute perforations (from 1 to 30 days after implantation) are more common than late perforations (after 30 days of implantation) and may present with nonspecific symptoms, thus diagnosis and treatment might not be immediate. Among predisposing causes of cardiac perforation, we recognize both technical factors related to the intervention technique, the type of “lead” used, the site of leads implantation, the number of previous interventions, and the site of vascular access, as well as patient-related risk factors such as age > 80 years, female sex, thinner atrial walls, and body mass index (BMI) < 20 kg/m2 [3–5]. Our clinical case describes the effective management of cardiac tamponade occurring in a 79-year-old man, caused by an atrial perforation resulting from an active fixation atrial lead. This report has its own clinical relevance, since to the best of our knowledge, there are only few studies regarding the management of atrial perforation post pacemaker implant.

The clinical case

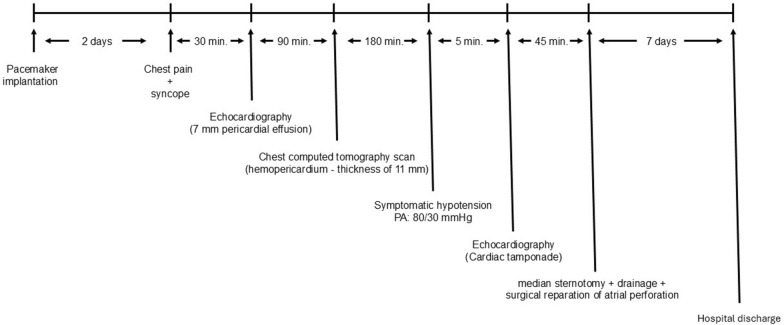

This clinical case concerns a Caucasian 79-year-old man with arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipemia, and carotid atherosclerosis. The patient had previously undergone implantation of a dual-chamber pacemaker (PMK) in the left subclavian region due to advanced atrioventricular block. Two years after implantation, due to infection of the device pocket, as evidenced by positron emission tomography computed tomography (PET–CT) (Fig. 1), the patient was scheduled for PMK device removal surgery. Prior to PMK removal, the patient underwent blood culture and subsequent empirical antibiotic therapy, awaiting results, with daptomycin 700 mg once daily and ceftazidime 1 g three times daily. Additionally, upon completion of the extraction procedure, a transesophageal echocardiogram with Doppler color flow imaging was performed, which ruled out the presence of vegetations suggestive of endocarditis. Subsequent blood culture results were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus hominis, prompting discontinuation of the previous antibiotic therapy and replacement with amoxicillin/clavulanate for 14 days. The reimplantation procedure was performed 4 months after removal of the infected device, although it could have been performed 2 weeks after discharge, following confirmation of negative blood cultures, at the patient’s request.

Fig. 1.

PET–CT, which highlights the uptake of the tracer in correspondence with the proximal section of the leads A and B, and the implant pocket C and D (arrows)

This procedure was performed via the right subclavian transvenous route using active fixation lead. Difficulties were encountered during the positioning of the atrial lead in the right atrial appendage; therefore, placement on the posterior wall of the right atrium was chosen. No complications were encountered during the positioning of the lead in the mid-apical interventricular septum (Fig. 2), neither did the patient report any discomfort immediately after the PMK implant. Two days after the procedure, the patient experienced an episode of nonspecific chest pain associated with syncope. Therefore, to document the ischemic origin of the symptoms the following tests were performed: electrocardiogram, which showed results comparable to the previous one; serial blood tests for high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-TnI) and creatine kinase-myocardial band (CK-MB), which resulted in the normal ranges. Moreover, to document the eventual defect of newly implanted device, telemetric control of the device was done, showing normal functioning, with impedance, pacing, and sensing values within normal ranges. Finally, to verify the presence of the pericardial effusion an echocardiogram was performed; this revealed a slight increase in systolic pulmonary artery pressure (PAPs) and a layer of pericardial effusion in the apical area, along the right chambers, with a thickness of 7 mm, not hemodynamically significant. Subsequently, to verify the physical characteristic of the effusion and the site of the probable perforation, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast was performed, which showed hemopericardium (maximum thickness of 11 mm), not enhancing (Fig. 3). The patient was then transferred to the coronary intensive care unit for further monitoring and medical treatment, remaining hemodynamically stable.

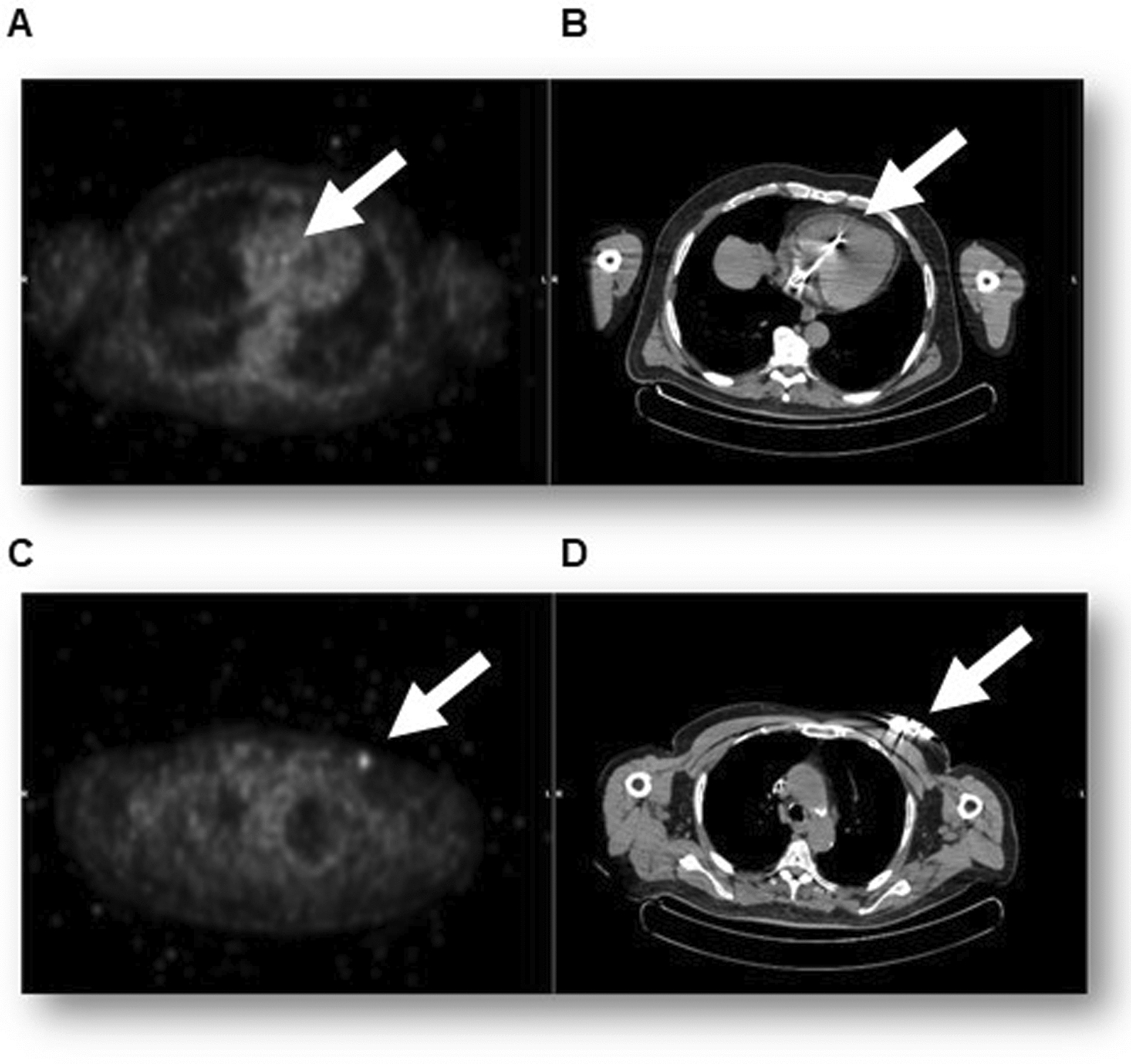

Fig. 2.

Anteroposterior postimplantation x-ray. Evidence of bicameral pacemaker positioned in the right subclavicular region, with leads in the right atrium and right ventricle (arrows)

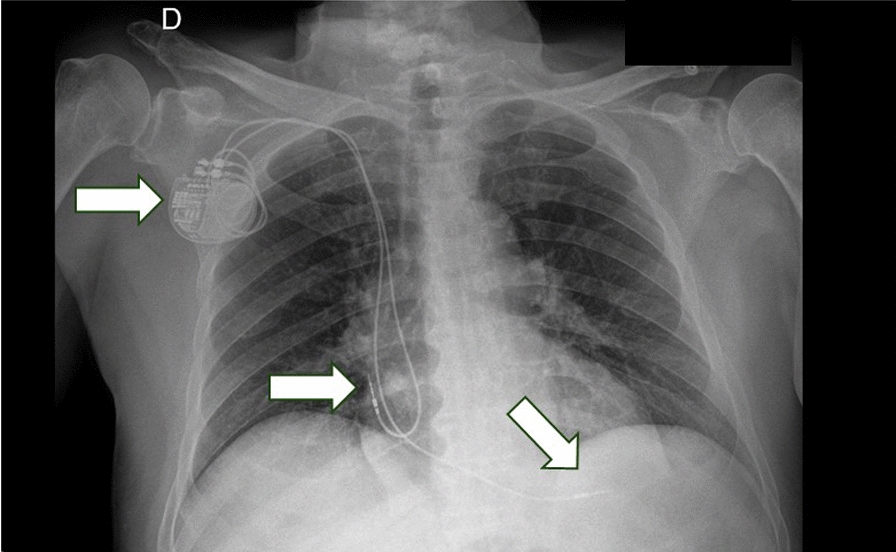

Fig. 3.

Non-electrocardiogram-gated plain cardiac computed tomography scan with contrast enhancement showing the not-replenished hemopericardium; however, it is not able to exclude lead perforation. White arrow indicates pericardial effusion

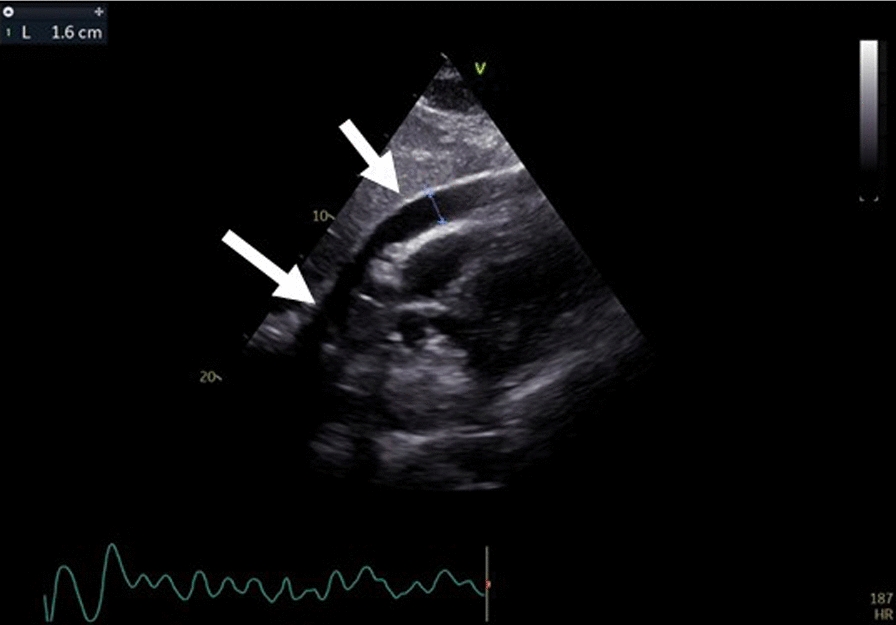

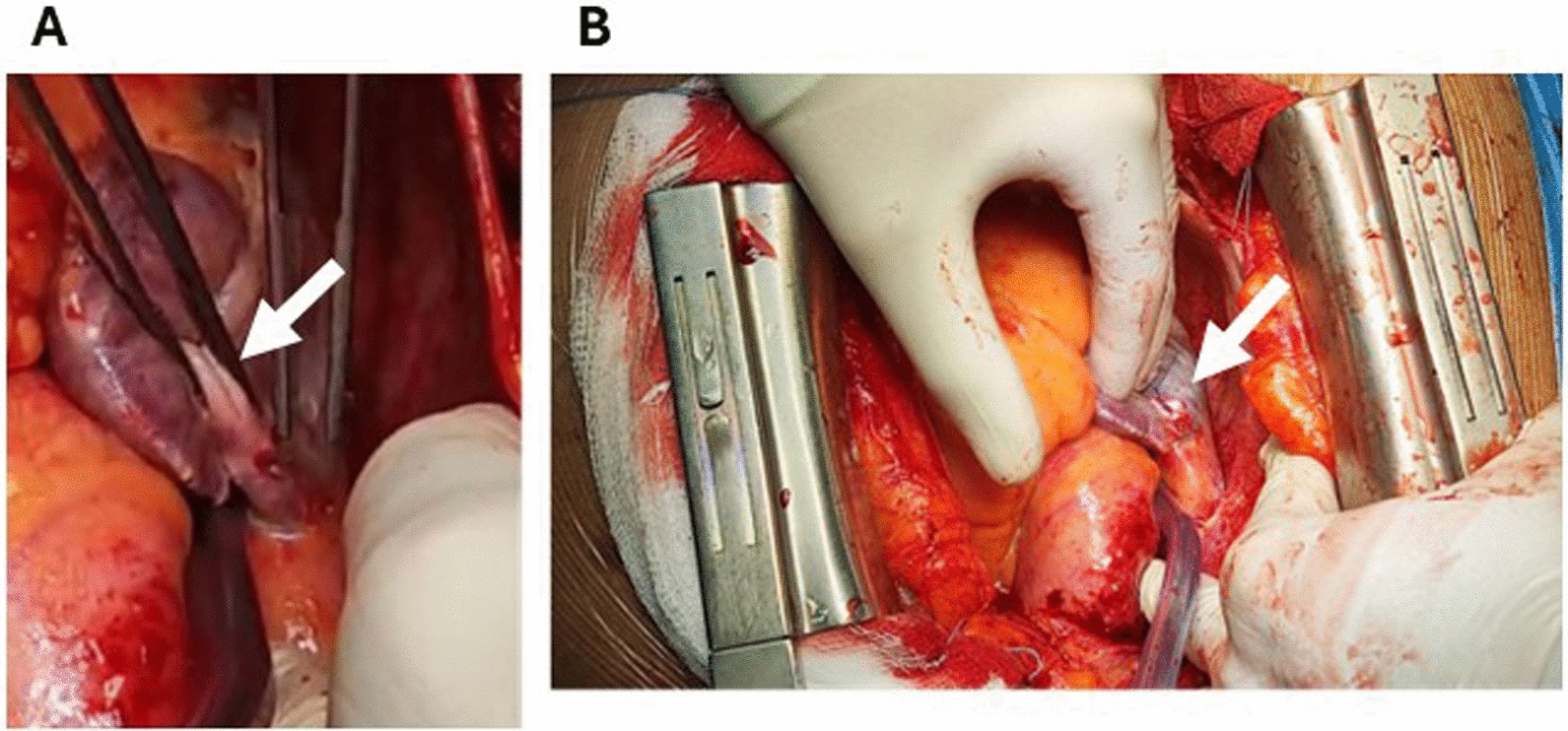

A few hours later, the patient experienced worsening clinical condition, characterized by hemodynamic instability (blood pressure: 80/30 mmHg) and the need for inotropic support. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed typical signs of cardiac tamponade with a pericardial effusion measuring 1.6 mm (Fig. 4). Due to the severe hemodynamic compromission, the patient was moved immediately in the department of cardiac surgery, for the surgical treatment of the complication. An urgent median sternotomy was performed with drainage of a significant hemopericardial effusion, revealing a perforation of the upper free wall of the right atrium (Fig. 5A), with pericardial injury caused by the retractable screw lead. The perforation site was sutured (Fig. 5B) and the sternal wound was closed. Three days later, the patient was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit, and a check of the recently implanted device showed normal functioning of the ventricular electrode and malfunction of the atrial one, prompting reprogramming of the PMK to ventricular demand pacing (VVI) mode. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to the cardiac rehabilitation department for continuation of antibiotic therapy and was discharged after 4 days without further complications. In the Fig. 6 is represented the time-course of the principal events that have characterized the hospitalization. At the control visit, scheduled 30 days after the hospital discharge, the patient was in good conditions, the hemodynamic parameters were in the normal ranges; the telemetric control of the newly implanted device documented normal functioning, as well as, the echocardiographic evaluation showed the absence of pericardial effusion and normal functional and morphologic cardiac parameters.

Fig. 4.

Pericardial effusion of 1.6 mm (arrow) and collapse of the right atrium visualized on echocardiography in conjunction with the drop in the patient's blood pressure

Fig. 5.

Lesion on the roof of the right atrium (A, arrow) treated by suturing with 5/0 prolene on a pledget (B, arrow)

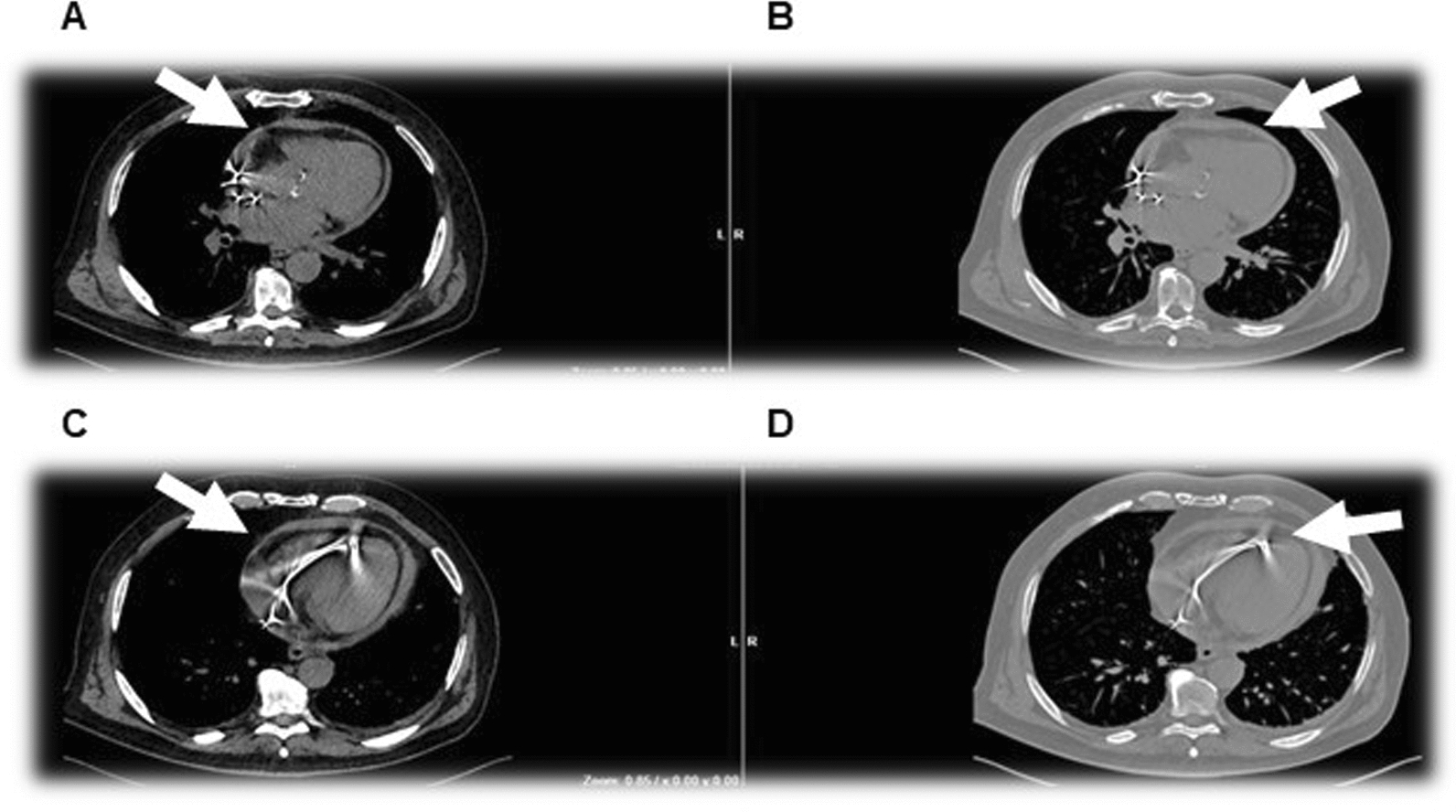

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the time-course of the principal events that characterized this clinical case

Discussion

This clinical case aims to raise awareness among readers about a very rare complication of cardiac device implantation procedures, namely cardiac perforations from a lead, specifically atrial perforations from leads. Although they are even rarer than ventricular perforations, they present with nonspecific symptoms and may not be immediately recognized through imaging techniques [6, 7]. Possible risk factors for cardiac perforation include the type of active fixation atrial lead, excessive screwing of the lead, distal insertion of the stylet, abrupt withdrawal of the lead with extended screw, and inadvertent displacement of the atrial lead during positioning of the ventricular one [8]. It is also worth noting that despite alternative sites being identified for lead fixation, the preferred location remains the right atrial appendage, as a thinner atrial wall may predispose to cardiac perforation, and fixation on the interatrial septum could be dangerous due to the proximity to the aortic root [9, 10]. Therefore, when difficulties are encountered in lead placement in the atrium, in the presence of symptoms, atrial perforation should be suspected.

Furthermore, it is important to pay more attention to patients who, due to their characteristics and medical history, are at higher risk of cardiac perforation, such as age over 80 years, female sex, thinner atrial walls, low BMI, chronic lung disease, congestive heart failure, and numerous previous cardiac interventions [3–5, 11]. This report seems to be inconsistent with the current literature that reports the female sex as a risk factor for post-PMK lead perforation. However, we believe that the senility, independent from the gender, represents a risk factor for this complication.

Patients with lead perforation may be asymptomatic or present with various symptoms such as retrosternal pain or discomfort, retrosternal burning, dyspnea, hiccups, dizziness, and weakness; in addition, evaluation of pacemaker parameters may remain unchanged [12, 13].

In cases of suspected pericardial effusion from lead, chest x-ray can certainly help in diagnosis, but the best imaging techniques are echocardiography with Doppler color flow, and contrast-enhanced CT, capable of both characterizing the effusion and identifying the point of cardiac rupture and the positioning of the lead [14, 15]. In particular, the accuracy of CT scan for the diagnosis of cardiac perforation has been reported to be 92.9%, which is superior to the echocardiography and chest x-ray (62.7% and 61.1%, respectively).

The treatment of post-PMK pericardial effusion may benefit from either pericardiocentesis or drainage through cardiac surgery. Although it has been reported that the treatment with pericardiocentesis and replacement or reposition of lead is safe and useful [16], expert consensus favors the use of cardiac surgery when urgent drainage is needed in cases of cardiac tamponade, as well as in all situations where pericardiocentesis is not feasible [17, 18].

Most complications occur during implantation or within the first 24 hours thereafter, but subacute perforations are also not uncommon phenomena. Although various patient- and procedure-related characteristics are independent predictors of early and late complications, their ability to identify high-risk patients is rather low. Given the increasing number of cardiac device implantation procedures, the incidence of these complications, and their unpredictable nature, we emphasize the usefulness of current guidelines for regular follow-up of patients with pacemakers both in the short and long term.

It is also important to remember that adverse events such as the one described can lead to legal disputes. The patient may argue that cardiac perforation is not to be considered a complication but rather caused by medical negligence and demand compensation. Full compliance with guidelines and best practices, along with careful preliminary assessment of the patient and any predisposing causes of the accident, as well as accurate documentation of procedures and subsequent patient care, can help prevent legal issues.

Conclusions

Although the atrial perforations from leads are very rare complications of pacemaker implantation procedures, they are potentially lethal. Therefore, in individuals at risk for this complication, there should always be the presence of aspecific symptoms. In conclusion, this clinical case highlights the need, before hospital discharge, of an accurate screening for evaluation the pericardial effusion in patients that undergo to the cardiac implantable electronic devices. Hopefully, in the next future, algorithms for the post-implant management will be better defined.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ms Federica De Luise for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

Author contributions

Conceptualization was performed by GF and GM; methodology was planned by PG and GG; writing of the original draft and preparation was carried out by GF, SG, SA, FL, SP, GBP, EP, and CDR; writing, review and editing, was performed by SG, PG, GG, CM, and GE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since they belong to the medical record of the patient; therefore, they are property of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria FEDERICO II, but they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report did not require the Ethical approval, at the hospitalization the patient gave the written consent for subsequent analysis of his data.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

None.

Footnotes

Publisher‘s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IM, Barrabés JA, Boriani G, Braunschweig F, Brignole M, Burri H, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: developed by the Task Force on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Eur Heart J. 2021;42(35):3427–520. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waechter C, Koenig AM, Chatzis G, Mueller J, Schieffer B, Luesebrink U. Delayed perforation of an atrial pacemaker electrode: lifelong risk for a rare but serious complication. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11(6): e7525. 10.1002/ccr3.7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avcı A, Demir K, Altunkeser BB. Aktif atriyum elektrodu yerleştirilmesi sonrası sağ atriyum delinmesi [Right atrial perforation after an endocardial screw-in atrial lead implantation]. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2013;41(6):541–4. 10.5543/tkda.2013.67299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole JE, Gleva MJ, Mela T, Chung MK, Uslan DZ, Borge R, Gottipaty V, Shinn T, Dan D, Feldman LA, Seide H, Winston SA, Gallagher JJ, Langberg JJ, Mitchell K, Holcomb R, REPLACE Registry Investigators. Complication rates associated with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator generator replacements and upgrade procedures: results from the REPLACE registry. Circulation. 2010;122(16):1553–61. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cano Ó, Andrés A, Alonso P, Osca J, Sancho-Tello MJ, Olagüe J, Martínez-Dolz L. Incidence and predictors of clinically relevant cardiac perforation associated with systematic implantation of active-fixation pacing and defibrillation leads: a single-centre experience with over 3800 implanted leads. Europace. 2017;19(1):96–102. 10.1093/europace/euv410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grebmer C, Russi I, Kobza R, Berte B. Atrial lead perforation early after device implantation: a case series. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2020;7(2):100–5. 10.1016/j.hrcr.2020.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirschl DA, Jain VR, Spindola-Franco H, Gross JN, Haramati LB. Prevalence and characterization of asymptomatic pacemaker and ICD lead perforation on CT. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30(1):28–32. 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trigano AJ, Taramasco V, Paganelli F, et al. Incidence of perforation and other mechanical Complications during dual active fixation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1996;19:828–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamidar H, Goli V, Reynolds DW. The right atrial free wall: an alternative pacing site. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1993;16(5 Pt 1):959–63. 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1993.tb04568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burri H, Starck C, Auricchio A, Biffi M, Burri M, D’Avila A, Deharo JC, Glikson M, Israel C, Lau CP, Leclercq C, Love CJ, Nielsen JC, Vernooy K, Dagres N, Boveda S, Butter C, Marijon E, Braunschweig F, Mairesse GH, Gleva M, Defaye P, Zanon F, Lopez-Cabanillas N, Guerra JM, Vassilikos VP, Martins Oliveira M. EHRA expert consensus statement and practical guide on optimal implantation technique for conventional pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin-American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace. 2021;23(7):983–1008. 10.1093/europace/euaa367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Date K, Murata T, Mano A, Kawata M, Kyo S. Perforation of the right atrial appendage during implantation of a leadless pacemaker. J Arrhythm. 2021;38(1):163–5. 10.1002/joa3.12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim YM, Uhm JS, Kim M, Kim IS, Jin MN, Yu HT, Kim TH, Lee HJ, Kim YJ, Joung B, Pak HN, Lee MH. Subclinical cardiac perforation by cardiac implantable electronic device leads detected by cardiac computed tomography. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1):346. 10.1186/s12872-021-02159-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellenbogen KA, Hellkamp AS, Wilkoff BL, Camunas JL, Love JC, Hadjis TA, Lee KL, Lamas GA. Complications arising after implantation of DDD pacemakers: the MOST experience. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:740–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajkumar CA, Claridge S, Jackson T, Behar J, Johnson J, Sohal M, Amraoui S, Nair A, Preston R, Gill J, Rajani R, Rinaldi CA. Diagnosis and management of iatrogenic cardiac perforation caused by pacemaker and defibrillator leads. Europace. 2017;19(6):1031–7. 10.1093/europace/euw074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pang BJ, Lui EH, Joshi SB, Tacey MA, Alison J, Seneviratne SK, Cameron JD, Mond HG. Pacing and implantable cardioverter defibrillator lead perforation as assessed by multiplanar reformatted ECG-gated cardiac computed tomography and clinical correlates. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37(5):537–45. 10.1111/pace.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rav Acha M, Rafael A, Keaney JJ, Elitzur Y, Danon A, Shauer A, Taha L, Shechter Y, Bogot NR, Luria D, Ilan M, Singh SM, Mela T, Weisz G, Glikson M, Medina A. The management of cardiac implantable electronic device lead perforations: a multicentre study. Europace. 2019;21(6):937–43. 10.1093/europace/euz120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Barón-Esquivias G, Bogaert J, Brucato A, Gueret P, Klingel K, Lionis C, Maisch B, Mayosi B, Pavie A, Ristic AD, Sabaté Tenas M, Seferovic P, Swedberg K, Tomkowski W, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921–64. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ristić AD, Imazio M, Adler Y, Anastasakis A, Badano LP, Brucato A, Caforio AL, Dubourg O, Elliott P, Gimeno J, Helio T, Klingel K, Linhart A, Maisch B, Mayosi B, Mogensen J, Pinto Y, Seggewiss H, Seferović PM, Tavazzi L, Tomkowski W, Charron P. Triage strategy for urgent management of cardiac tamponade: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(34):2279–84. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since they belong to the medical record of the patient; therefore, they are property of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria FEDERICO II, but they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.