Abstract

The influence of oil and gas end-use activities on ambient air quality is complex and understudied, particularly in regions where intensive end-use activities and large biogenic emissions of isoprene coincide. In these regions, vehicular emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx≡NO + NO2) modulate the oxidative fate of isoprene, a biogenic precursor of the harmful air pollutants ozone, formaldehyde, and particulate matter (PM2.5). Here, we investigate the direct and indirect influence of the end-use emissions on ambient air quality. To do so, we use the GEOS-Chem model with focus on the eastern United States (US) in summer. Regional mean end-use NOx of 1.4 ppb suppresses isoprene secondary organic aerosol (OA) formation by just 0.02 μg m–3 and enhances abundance of the carcinogen formaldehyde by 0.3 ppb. Formation of other reactive oxygenated volatile organic compounds is also enhanced, contributing to end-use maximum daily mean 8-h ozone (MDA8 O3) of 8 ppb. End-use PM2.5 is mostly (67%) anthropogenic OA, followed by 20% secondary inorganic sulfate, nitrate and ammonium and 11% black carbon. These adverse effects on eastern US summertime air quality suggest potential for severe air quality degradation in regions like the tropics with year-round biogenic emissions, growing oil and gas end-use and limited environmental regulation.

Keywords: fine particle pollution, oil and gas consumption, atmospheric composition, summertime ozone, eastern United States, chemical transport model, criteria pollutants, isoprene emissions

Short abstract

We elucidate the complex effects of oil and gas end-use activity emissions on air quality in a region where intensive use of oil and gas products and large emissions of biogenic isoprene co-occur.

1. Introduction

End use of processed and unprocessed oil and natural gas in fuel combustion and industrial processes contribute significant emissions of air pollutants that are damaging to public health.1−5 In the US, oil and gas collectively accounts for more than two-thirds of total energy consumption6 and almost all (94%) energy consumed by the transport sector.7 High-temperature combustion of fossil fuels in transportation produces large amounts of nitrogen oxides (NOx)1,8 that directly increase abundance of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and that undergo heterogeneous chemistry to form fine particulate matter (PM2.5).9,10 Other widely used products of oil and gas include industrial and domestic volatile chemical products (VCPs) such as cleaning and personal care products that have been identified as a major source of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in US cities.11 VCPs directly harm health and contribute to PM2.5 pollution.12−14 Exposure to NO2 is linked to increased incidences of childhood asthma15 and exposure to PM2.5 is linked to premature mortality from multiple causes.16,17

Absent is a comprehensive assessment of the primary and secondary effects of oil and gas end-use activities on air pollutant precursor emissions and air quality in environments where end-use activities are in close proximity to large biogenic emissions of isoprene. Previous studies have quantified the adverse effects of end-use of oil and gas together with other fossil fuels such as coal,18 so it is not possible to disentangle the contribution from oil and gas end-use. Other studies that have examined air pollution from the oil and gas industry have only assessed the effects of pollution from the production stage of the oil and gas lifecycle.19−23 Almost all of these studies have focused exclusively on criteria air pollutant concentrations, rather than investigating the relationship between primary emissions of natural and anthropogenic precursors. This knowledge gap of the complex pathways leading to air quality degradation has implications for regions like the eastern US that are adopting net zero policies and transitioning to cleaner fuels and even more so for fast-growing cities in the tropics with year-round emissions of isoprene that are experiencing rapid industrialization, urbanization, economic and population growth and increasing air pollution.24,25

The large influence of urban NOx from vehicular combustion on atmospheric composition was apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering a glimpse into urban air quality in the absence of reliance on a prominent oil and gas end-use activity. This event enabled elucidation of the pathways leading to changes in atmospheric composition and improvements in air quality, but in early spring when isoprene emissions are dormant. In the densely populated eastern US, strict lockdowns substantially reduced traffic NOx emissions, causing a decline in NOx concentrations26−29 and affecting abundance of PM2.5. Formation of the PM2.5 component particulate nitrate (pNO3) from oxidation of NOx declined.30−32 As did the PM2.5 component particulate ammonium (pNH4). The decrease in pNH4 resulted from decline in ammonia emissions from mobile sources and less uptake of ammonia, an acid buffer, to aerosols due to decline in abundance of acidic pNO3.29 The effect of strict COVID-19 lockdowns on the secondary air pollutant ozone (O3) differed in urban and rural areas. Urban O3 increased, as its titration by NOx was dampened, while suburban and rural O3 decreased, as O3 production in these environments is limited by the availability of NOx.33

The strict lockdowns only offer an assessment of the contribution of road traffic to O3 and PM2.5, as VCP usage was unaffected.29 The occurrence of these lockdowns in early spring is also only the onset of the spring-summer peak O3 pollution period in the eastern US34 and precedes the summertime (June-August) peak in biogenic isoprene emissions in the southeast US caused by high temperatures, abundant sunlight, and dense vegetation.35 Isoprene is a precursor of multiple air pollutants. These include O3, the carcinogen formaldehyde (HCHO), and secondary organic aerosols (SOA) that make a substantial contribution to summertime PM2.5.36−39 The effect isoprene has on these pollutants depends on the availability of NOx, as NOx modulates the oxidative fate of isoprene.37,39,40 In the presence of large concentrations of NOx typical of the eastern US, isoprene oxidation leads to high and prompt yields of HCHO and of other similarly small oxygenated VOCs that react to form O3.39,40 When NOx concentrations are relatively low, as may occur in the absence of emissions of vehicular NOx, formation of SOA precursors via the competing hydroperoxyl radical (HO2) oxidation pathway should increase. These precursors include isoprene epoxydiols (IEPOX) that undergo fast acid-catalyzed reactive uptake to aqueous acidic aerosols, glyoxal that oligerimerizes in aqueous aerosols, and low-volatility high-molecular weight products (C5-LVOCs) that readily partition to pre-existing aerosols.36,41,42 Isoprene SOA formation is most influenced by availability of acidic sulfate aerosols (pSO4)36,43 that are still abundant and very acidic (pH ∼ 2-3)44−46 in the eastern US in summer, despite sustained decline in precursor emissions of sulfur dioxide (SO2)47 and due to the limited buffering capacity of ammonia.44

Here we investigate the complex direct and indirect pathways of influence of emissions of oil and gas end-use activities, hereafter referred to as “end-use”, on summertime eastern US air quality to better inform policies that mitigate emissions from processed and unprocessed oil and gas. To do so, we first process multiple contemporary emissions estimates to obtain an updated inventory of emissions of air pollutant precursors linked to end-use and implement this inventory in the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model to quantify air pollutant concentrations attributable to end-use activities. This includes evaluation of modeled NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM2.5 components with observations from the extensive national surface monitoring network needed to bias correct model-derived attribution of oil and gas end-use activity emissions to air pollutant concentrations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Oil and Gas End-Use Emissions and the GEOS-Chem Model

Anthropogenic emissions for on- and off-road mobile sources are from the Fuel-based Inventory for Vehicular Emissions (FIVE) (https://csl.noaa.gov/groups/csl7/measurements/2020covid-aqs/emissions/; last accessed 5 September 2022).8,48 These are provided as gridded (4-km) hourly emissions for 2018-2020 for use in COVID-19 modeling and emissions studies.8,29 Anthropogenic emissions for all other sources, except commercial ships and aircraft, are from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Emissions Inventory (NEI). These are provided as county-level annual totals of active Source Classification Codes (SCCs). The 248 SCCs we classify as end-use are listed in Supporting Information Table S1.

The most recent publicly available NEI emissions year not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic is 2017 (NEI 2017; https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-inventories/2017-national-emissions-inventory-nei-data; last accessed 5 September 2022) and so we select 2017 as the study year. Oil and gas consumption in the US has remained relatively stable since 2017. In 2018-2019, it increased by 5%, whereas in 2020-2021 it declined to 2017 totals due to reduced demand brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.7 We generate gridded hourly emissions from the NEI 2017 emissions using a custom codebase adapted from the Sparse Matrix Operator Kernel Emissions (SMOKE) processing system, previously developed and used in numerous publications.29,48,49 SMOKE processing yields hourly emissions for the same grid resolution and days as FIVE. Due to the computational cost of processing NEI, we generate emissions for end-use and other anthropogenic activities for July only. For consistency, we also select the FIVE July hourly emissions. FIVE emissions are for 2018 and so slightly underestimate 2017 emissions, as NOx emissions from mobile sources declined steadily each year prior to the pandemic due to controls on emissions.50 We use the NEI and FIVE data to calculate emissions for the other summer months and April-May needed for model chemical initialization by applying broad sector-specific seasonal scaling factors derived with the NEI 2016 emissions that have been custom built for use in GEOS-Chem (http://geoschemdata.wustl.edu/ExtData/HEMCO/NEI2016/v2021-06/, last accessed 10 December 2023). We regrid the FIVE and NEI 4-km resolution emissions to 0.1 ° × 0.1 ° to implement in GEOS-Chem.

We use GEOS-Chem version 13.0.0 (10.5281/zenodo.4618180; last accessed 1 March 2023) to simulate the complex changes in atmospheric composition linked to emissions from end-use activities. The model is driven with NASA GEOS-FP meteorology. We simulate the model in a nested configuration over contiguous US (23 °-51 °N, 128 °-63.5 °W) at 0.25 ° × 0.3125 ° (∼28 km latitude × ∼27 km longitude at the nested domain center) in summer (June-August 2017). Dynamic (3-hourly) boundary conditions are from a global simulation (4 ° × 5 °). Model chemical initialization is achieved with a 1-year spinup for the boundary conditions and 2 months for the nested domain.

NEI 2017 emissions of all aerosol-bound metals and "Other PM2.5" are emitted as dust. Anthropogenic emissions outside the US, including shipping emissions in US territorial waters, are from the global Community Emissions Data System (CEDS) v2 emission inventory. Aircraft emissions are from the global Aviation Emissions Inventory Code (AEIC) inventory for 2005.51,52 The model also includes open fire and natural emissions. Open fire emissions are from the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED) version 4 with small fires. Natural emissions are calculated using the Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature (MEGAN) version 2.135 for biogenic VOCs, and the parametrizations of Hudman et al.53 for soil NOx, and Jaeglé et al.54 for sea salt. Hourly offline dust55 and lightning NOx56 emissions are those generated at 0.25 ° × 0.3125 °. The timezone file currently implemented in GEOS-Chem, derived using Voronoi polygons, is at coarser resolution (1 ° × 1 °) than the nested grid and defines timezones by standard time only. We update GEOS-Chem representation of timezones by gridding to 0.1 ° × 0.1 ° the timezone data from the Time Zone Database (https://www.iana.org/time-zones; last accessed 16 April 2023) and by also accounting for daylight savings time, thus shifting emissions from sources like vehicle traffic to 1 hour earlier than standard time.

The model includes detailed coupled gas- and aerosol-phase chemistry and wet and dry deposition to represent formation and loss of O3 and PM2.5 components. pSO4 is formed from oxidation of SO2 by the hydroxyl radical and by in-cloud hydrogen peroxide.10 Formation of pNO3 and pNH4 is via thermodynamic equilibrium calculated by ISORROPIA II.57 We use a revised parametrization of rainout and washout58 that increases wet scavenging of pNO3 and pNH4 in the US. Primary OA (POA) is emitted as 50% hydrophilic and 50% hydrophobic59 that is assumed to age to hydrophilic with a lifetime of 1.15 days.60,61 SOA from isoprene is calculated using a mechanism that accounts for irreversible reactive uptake of the isoprene oxidation products IEPOX, C5-LVOCs, and glyoxal to aqueous aerosols.36 IEPOX, the dominant isoprene SOA precursor, undergoes acid catalyzed reactive uptake, so depends on the abundance of acidic aerosols. SOA from monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes is represented in the model using fixed mass yields of 10% each.62 Anthropogenic SOA formation from oxidation of anthropogenic VOCs and from aerosol uptake of intermediate- and semi-volatile organic compounds (IVOCs and SVOCs) is estimated as 6% by mass of anthropogenic CO emissions.63

The nested model is simulated with and without end-use emissions. End-use emissions turned off in the latter are FIVE for on-road and off-road mobile sources, NEI 2017 emissions of the selected end-use SCCs (Supporting Information Table S1 ), AEIC for aircraft, and CEDS for shipping. The difference between the two simulations is used to quantify the contribution of end-use to summertime O3 and PM2.5 in eastern US (east of 100 °W).

2.2. Surface Air Pollutant Observations to Evaluate GEOS-Chem

The eastern US includes a widespread, dense network of measurements of surface concentrations of PM2.5, PM2.5 components (organic carbon (OC), pNO3, pNH4, and pSO4), NO2, and O3 for extensive model evaluation and to correct model biases where these impart errors in findings that have implications for policy decisions. The network measurement data are from the US EPA Air Quality System (AQS) database (https://aqs.epa.gov/aqsweb/documents/data_api.html; last accessed 1 March 2023) for both trace gases and aerosols and the Interagency Monitoring of Protected Visual Environments (IMPROVE) program (http://vista.cira.colostate.edu/Improve/; last accessed 16 April 2023) for aerosols only. AQS sites, located mostly in urban and suburban areas, are part of the national ambient air monitoring program to assess compliance with the national air quality standards. IMPROVE monitors visibility in areas with special air quality protections such as national parks and wilderness areas. We use air quality data for all sites operational in the eastern US in June-August 2017. PM2.5 measurements are from beta attenuation monitoring or gravimetric sampling, OC from thermal optical reflectance analysis, pNO3 pNH4, and pSO4 from ion chromatography, NO2 from chemiluminescence, and O3 from an ultraviolet detector. We select sites with 75% data coverage in each month totalling 423 for PM2.5, 161 for OC, 154 for pNO3, 108 for pNH4, 159 for pSO4, 229 for NO2, and 829 for O3.

We correct OC observations from the IMPROVE network for a ∼30% low bias attributed to evaporative loss of semivolatiles.64,65 NO2 observations from chemiluminescence instruments used as part of air quality monitoring networks are often denoted as “NO2*” to represent positive interference from decomposition of thermally unstable NOx reservoir compounds such as peroxy-acetyl nitrate (PAN), methyl peroxy nitrate (MPN, CH3O2NO2) and peroxy nitric acid (HNO4).66,67 We calculate the equivalent NO2* in GEOS-Chem using reported operating temperature-dependent percentage interference values.67 At typical operating conditions of ground-based chemiluminescence instruments, interference includes reservoir compounds such as 5% PAN, 100% MPN and 100% HNO4. Interference according to GEOS-Chem is small (<1%), as these thermally unstable reservoir compounds are not prevalent in summer in the eastern US.

For consistent comparison of GEOS-Chem and the ground-based observations, we sample outputs from the lowest model layer and grid the observations to the GEOS-Chem grid. Modeled PM2.5 is calculated as the sum of the concentrations of individual simulated components multiplied by hygroscopic growth factors at the same relative humidity (35% RH) and temperature and pressure (ambient) as the measurements68

| 1 |

Equation 1 terms are BC for black carbon, OCPO for the hydrophobic component of primary OC, OCPI for the hydrophilic component of primary OC, SOA formed from biogenic and anthropogenic precursors, SSA for accumulation-mode sea salt, and DUST is dust aerosol. The α terms are OA/OC ratios that are typically 1.5 for primary sources and 2.1 after aging.69 OCPO is freshly emitted and so we use α1 = 1.5. OCPI is a mix of freshly emitted and aged aerosol and so we use α2 = 1.8. We sample hourly O3 concentrations from GEOS-Chem to calculate maximum daily 8-h running-mean ozone (MDA8 O3), the metric used for air quality compliance monitoring and health burden assessments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Contribution of Oil and Gas End-Use Activities to Emissions

Figure 1 shows total and end-use contribution to anthropogenic emissions of dominant air pollutant precursors in the eastern US for June-August 2017 that we include in GEOS-Chem. All NEI and FIVE emissions of CO, NOx, ammonia (NH3), SO2 and primary PM2.5 are included in the model, whereas a portion of NMVOCs emissions are represented in GEOS-Chem. Even though there are only 17 lumped and individual NMVOCs in GEOS-Chem, these account for 65% of the NMVOCs mass reported by the inventories. The largest anthropogenic emissions in GEOS-Chem are for CO (5.5 Tg), NOx (1.6 Tg) and NMVOCs (1.3 Tg). End-use activities contribute to more than half the emissions of CO (4.7 Tg), NOx (1.1 Tg), and BC (23 Gg), and just below half for NMVOCs (0.6 Tg). Dominant end-use activities include all mobile (vehicle) sources for CO70,71 and NOx,72 diesel vehicles for BC,72,73 and VCPs for NMVOCs.11 The relative contribution of end-use activities to anthropogenic emissions of the other compounds is smaller at 16% for OC (17 Gg), and 5% for NH3 (57 Gg) and for SO2 (23 Gg). End-use emissions are mainly from catalytic converters of onroad gasoline for NH3,74 industrial boilers and commercial buildings for SO2,75 and mobile sources for OC.76 There is a very small contribution of end-use activities to inorganic primary PM2.5 components (not shown) of 1.7 Gg pSO4, 0.7 Gg pNH4, and 0.3 Gg pNO3.

Figure 1.

Eastern US anthropogenic air pollutant precursor emissions in summer 2017. Stacked bars show the relative contribution of end-use (blue) and non end-use (orange) emissions to total anthropogenic emissions for dominant gaseous pollutants (CO, NOx, NMVOCs, NH3 and SO2) and primary PM2.5 components (OC and BC). Values outside the bars are the total emissions for June-August. Value for NMVOCs is total speciated emissions included in GEOS-Chem (Section 2.1).

3.2. Addressing GEOS-Chem Biases in Particulate Nitrate and Ammonium

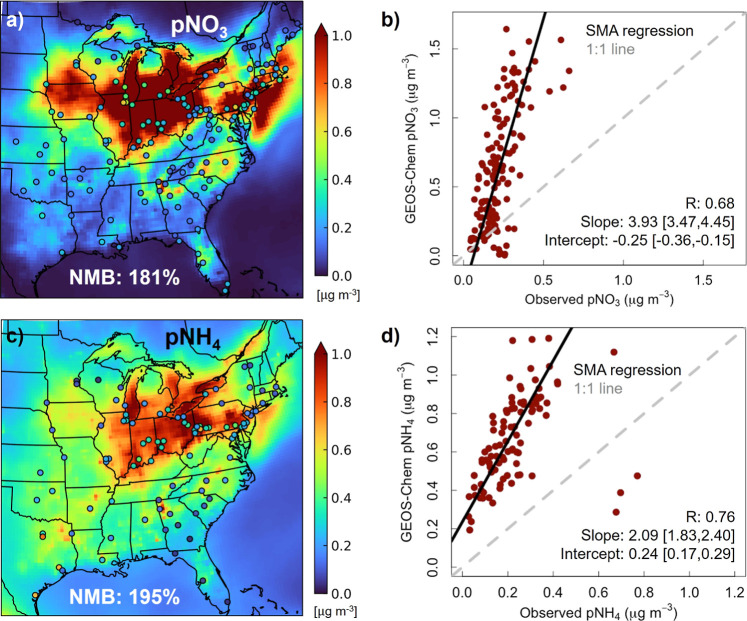

GEOS-Chem comparison to surface observations is shown and discussed in the SI (Supporting Information Text S1 and Figures S1-S2 ) for pollutants (NO2, MDA8 O3, PM2.5, OC) that the model is consistent with spatially (R > 0.5). Pertinent for perturbation studies is that the model also reproduces the observed variance for these pollutants, yielding regression slopes close to unity. The model exhibits a large and significant bias in both pNO3 and pNH4 (Figure 2). Observed pNO3 and pNH4 are typically <0.5 μg m–3 in the eastern US in summer. GEOS-Chem overestimates each component by almost a factor of 3 (NMBs of 181% for pNO3 and 195% for pNH4). Such large biases have also been reported in prior studies targeting the contiguous US86,87 and other parts of the world like China that have substantial anthropogenic precursor emissions of pNO3 and pNH4.88 A range of potential causes have been suggested for the bias in pNO3 that in turn enhances NH3 partitioning to aerosols to form pNH4, as the additional aerosol acidity from pNO3 promotes partitioning of gas-phase NH3 to the aerosol to neutralize the acidity by forming pNH4. Causes that have been proposed for the model bias in pNO3 include uncertainties in processes that affect abundance of nitric acid (HNO3), the NOx oxidation product and precursor of pNO3,86 kinetic inhibition of pNO3 formation by organically coated aerosols not accounted for in GEOS-Chem,89 and low biases in pNO3 and pNH4 wet deposition.58,87 Heald et al.86 tested sensitivity to uncertainties in a range of processes that affect model simulation of HNO3 to find that a brute force 75% decrease in HNO3 is most effective at improving agreement between GEOS-Chem and the same IMPROVE surface observations of pNO3 and pNH4 used in this study. Silvern et al.90 found that invoking kinetic inhibition was only effective at addressing the bias in the southeast US. We already implement the more efficient wet deposition scheme of Luo et al.58 that we find has limited effect on pNO3 and pNH4 in summer.

Figure 2.

Assessment of GEOS-Chem eastern US summer 2017 surface pNO3 and pNH4. Maps compare simulated (background) and observed (circles) June-August mean pNO3 (a) and pNH4 (c). Values inset are the model NMB for coincident grid squares and observations. Scatter plots compare coincident modeled and observed pNO3 (b) and pNH4 (d). Lines are SMA regression (black solid) and 1:1 agreement (gray dashed). Values inset are Pearson’s correlation coefficients (R) and SMA regression statistics. Relative errors on the slopes and intercepts are the 95% CI. R and SMA regression in panel (d) exclude the 3 outlier points in Texas.

The much greater variance in modeled pNO3 (slope ∼ 3.9) and pNH4 (slope ∼ 2.1) will cause a large overestimate in attribution of end-use emissions to these aerosol components. So, we apply a correction to modeled pNO3 and pNH4 to address this bias. To do so, we divide the difference in pNO3 and pNH4 concentrations between the simulations with and without end-use emissions by the regression slopes in Figure 2b and d. This yields corrected attributable concentrations that we apply to eq 1 to recompute end-use PM2.5. This decreases eastern US mean end-use attributable pNO3 by 0.21 μg m–3 and pNH4 by 0.05 μg m–3. Accounting for this correction and an associated decrease in aerosol water at 35% RH (eq 1) leads to a 0.32 μg m–3 decrease in end-use PM2.5. We use corrected end-use pNO3, pNH4, and PM2.5 to determine the influence of end-use emissions on summertime air pollution in the eastern US in the section that follows.

3.3. Contribution of Oil and Gas End-Use Activities to Air Pollution

Figures 3 and 4 show the influence of end-use activities on gas-phase (Figure 3) and particle-phase (Figure 4) pollutants obtained as the difference between model simulations with and without end-use emissions and corrected for model biases in pNO3, pNH4 and PM2.5 (Section 3.2). End-use activities make a large contribution to summertime mean NOx of up to 20 ppb. More than 90% of this is NO2 that is mostly collocated with major cities and highways (Figure 3a). Even though the majority of NOx is emitted as NO, the end-use activity NO concentration is small (0.12 ppb on average), as NO rapidly converts to NO2, maintaining eastern US mean NO/NO2 ratios at ∼9% in both simulations. As a result of the small contribution of NO to NOx, the shift in isoprene from oxidation via the NO pathway to oxidation via the HO2 pathway is small. In the absence of end-use emissions, 42% of isoprene is oxidized by NO and 30% by HO2. The proportion is 49:27 NO:HO2 with end-use emissions. The additional branching attributed collectively to the NO and HO2 pathway with end-use activities is because the less prevalent isomerization92,93 branch declines with end-use emissions. The modest response of the branching ratios to end-use activities is fairly consistent across the region, though these differ between the north (55:25 NO:HO2 without end-use, 62:22 NO:HO2 with) and south (34:33 NO:HO2 without end-use, 40:30 NO:HO2 with) due to greater NOx abundance in the north.

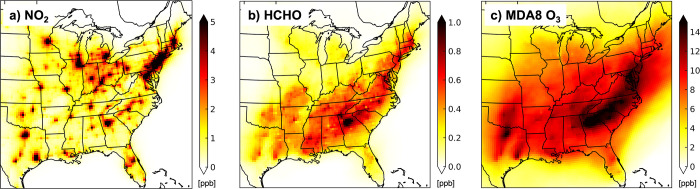

Figure 3.

Contribution of oil and gas end-use activities to surface concentrations of ozone and its precursors in summer (June-August) 2017. Maps are of eastern US NO2 (a), HCHO (b) and MDA8 O3 (c) from the difference in GEOS-Chem simulations with and without end-use emissions.

Figure 4.

Contribution of oil and gas end-use activities to surface concentrations of PM2.5 and its components in summer (June-August) 2017. Maps are eastern US OA (a), sum of pNO3 and pNH4 (b), isoprene SOA (c) and PM2.5 (d) from the difference in GEOS-Chem simulations with and without end-use emissions and, for pNO3, pNH4 and PM2.5, corrected for model biases using the surface network observations (see Section 3.2 for details).

Large end-use activity enhancements in HCHO in the southeast and along the northeast coast (Figure 3b) result from higher and more prompt yields of HCHO (Figure 3b) via the NO isoprene oxidation pathway than the HO2 pathway.40,94 We estimate that end-use activity NOx emissions increase isoprene oxidation HCHO yields by 8-10% over the locations in Figure 3b, exceeding 400 ppt from interpolation of reported GEOS-Chem chemical mechanism HCHO yields at 1 ppb NOx (∼1.9 moles HCHO per mole isoprene) and at 0.1 ppb NOx (∼1.6 mol mol–1).40 Secondary production of HCHO attributable to end-use activities exceeds 1 ppb in and around Atlanta, coincident with the NO2 hotspot in Figure 3a and where interaction of biogenic and anthropogenic emissions is well-known to degrade air quality.95−97 The enhanced yields of HCHO and other small reactive oxygenated VOCs from isoprene oxidation also contribute to MDA8 O3 in the region, as O3 production is limited by availability of VOCs.98 Overall, end-use emissions contribute at least 5 ppb MDA8 O3 in most (∼80%) of the eastern US and >14 ppb across a large swath of eastern US from north Georgia extending as far north as southern New England (Figure 3c). The role of end-use primary HCHO (12 Gg) in the enhancement in Figure 3b and in forming MDA8 O3 is minimal in comparison to secondary HCHO, as emissions of primary HCHO are limited to major cities. These primary HCHO emissions are evident as faint (<300 ppt) isolated enhancements in cities such as Pittsburgh, Detroit and Chicago located north of the southeast US biogenic HCHO enhancement.

The contribution of end-use activities to OA across the eastern US exceeds 2 μg m–3 along the northeast corridor and in large cities (Figure 4a). Most of this is due to anthropogenic OA from primary and precursor VOCs emissions from vehicles and from VCPs concentrated in cities. Eastern US mean end-use POA is 0.11 μg m–3 and anthropogenic SOA is 0.47 μg m–3. It is not possible to quantify the influence of individual VOCs or source types on anthropogenic SOA, as CO emissions are used to estimate anthropogenic SOA in GEOS-Chem (Section 2.1). End-use activities account for most of the anthropogenic CO emissions (Figure 2), resulting in a large decline in OA. Use of CO as a proxy for SOA formation is standard99,100 and defensible,63 given the limited detailed knowledge of VOCs emissions and reaction pathways forming SOA,101 challenges representing these in models without large computational burden, and the major (∼80%) contribution of end-use activity emissions of known SOA precursors such as alkanes and toluene to total anthropogenic emissions in the US NEI.

End-use NOx increases the abundance of acidic pNO3 that in turn promotes uptake of ammonia, mainly from agriculture,102,103 forming pNH4 (Figure 4b). As a result, pNO3 and pNH4 are typically collocated. The corrected pNO3 and pNH4 (Section 3.2) are similar in magnitude to that of end-use pSO4 (∼0.1-0.2 μg m–3) (not shown), but the spatial distribution of end-use pSO4 differs. The greatest contribution of end-use activities to pNO3 and pNH4 of up to 0.6 μg m–3 is in the northeast.

The end-use activity effect on isoprene SOA is mixed. Influence of end-use NOx emissions on the oxidative fate of isoprene (Section 3.2) suppresses formation of the SOA precursors IEPOX and C5-LVOCs and promotes formation of the SOA precursor glyoxal, though the SOA yields of this precursor are uncertain.36 End-use pSO4 enhances isoprene SOA formation by increasing the abundance of acidic aqueous-phase aerosols. The net effect is suppression of isoprene SOA formation, though the effect is small; 0.02-0.03 μg m–3 in most of the US and 0.06-0.08 μg m–3 in large cities in the southeast (Figure 4c). End-use BC (not shown), a potent short-lived climate forcer, is on average about 0.1 μg m–3 in the eastern US and 0.3-0.4 μg m–3 in large cities.

The net effect of end-use activities on PM2.5 (Figure 4d) is a 1.5 μg m–3 contribution in most of the eastern US and >3 μg m–3 contribution in cities and along the northeast coast. Anthropogenic OA makes the greatest and most widespread contribution to end-use PM2.5 concentrations, followed by BC and the inorganic secondary aerosols pSO4, pNO3, and pNH4.

3.4. Pathways of Influence of Oil and Gas End-Use on Atmospheric Composition

Figure 5 summarizes the primary and secondary routes of influence of end-use activities on eastern US mean concentrations of the health-damaging pollutants NO2, PM2.5, HCHO, and MDA8 O3. The direct effect of end-use activity emissions (Figure 1) on ambient concentrations of these and precursors to these pollutants is 1.4 ppb NOx, 17 ppt SO2, and 0.1 μg m–3 each of BC and primary OA. As pSO4, pNO3, pNH4, and BC loss processes are the same, we use the BC end-use emissions-to-concentration ratio of 220 Gg (μg m–3)−1 to estimate that 1.7 Gg primary end-use pSO4 accounts for ∼16% of end-use pSO4, 0.32 Gg primary end-use pNO3 for only 2% of end-use pNO3, and 0.69 Gg primary end-use pNH4 for 6% of end-use pNH4. Primary formation of HCHO is prevalent in urban areas (Section 3.3), but even in cities with relatively large anthropogenic HCHO sources attributable to end-use activities, most anthropogenic HCHO is secondary, from oxidation of VOCs.104

Figure 5.

Influence of oil and gas end-use on air pollutants in eastern US in summer (June-August) 2017. Bars and values above each bar indicate summer mean concentrations with and without end-use activity emissions and values in bubbles above bars are percent changes attributable to end-use activities. The dashed box distinguishes gas- and aerosol-phase pollutants. Hatched portion of PM2.5 is anthropogenic SOA parametrized in GEOS-Chem using CO emissions as a proxy (Section 2.1). A small contribution of end-use pSO4, pNO3 and pNH4 is from primary sources. With-end-use simulated summer mean concentrations of pNO3 and pNH4 are corrected for model biases by dividing by model NMBs in Figure 2. Without-end-use means are recomputed using the corrected with-end-use means and end-use attributable means (correction to latter detailed in Section 3.2). PM2.5 for both simulations is recomputed using the corrected pNO3 and pNH4.

Secondary effects include the influence of end-use NOx on the oxidative fate of isoprene that suppresses isoprene SOA formation by just 0.02 μg m–3, but promotes formation of 300 ppt HCHO via the prompt and high-HCHO-yield NO oxidation pathway (Section 3.3). The greater yields of HCHO and other associated small reactive oxygenated VOCs also enhance O3 formation, contributing to 8 ppb MDA8 O3. Other major secondary processes that affect end-use PM2.5 is SOA sourced from anthropogenic VOCs, pNO3 from oxidation of NOx, pSO4 from oxidation of SO2, and pNH4 from reversible partitioning of NH3 to neutralize acidic aerosols. The largest contributor to end-use PM2.5 is SOA (0.47 μg m–3). A meagre 17 ppt SO2 from end-use activities has an outsized effect on pSO4 (0.04 μg m–3) compared to a similar effect of 1.42 ppb end-use NOx (90% NO2) on pNO3 (0.07 μg m–3) that in turn promotes formation of a similar amount of pNH4 (0.05 μg m–3). PM2.5 components are mostly enhanced over urban areas and the northeast corridor, except for the enhancement in pNO3 and pNH4 that occurs over the agriculturally intensive corn belt (Figure 4b), as most US NH3 emissions are from agricultural activity102,103 that is well-known to exacerbate PM2.5 formed from other sector activities.105,106

Overall, end-use PM2.5 from primary and secondary processes is 0.88 μg m–3. This is ∼9% of eastern US PM2.5, though this is conservative, as GEOS-Chem PM2.5 has a positive bias in background PM2.5 that is likely due to a model overestimate in dust (Supporting Information Text S1 ). If we correct for our estimated systematic model bias of ∼2.8 μg m–3, the contribution increases to ∼13%. The influence estimates from this work are not directly comparable to previous studies, as past studies have either lumped together oil and gas end-use with coal, focused on a subset of end-use activities such as power generation, did not consider the primary emissions of air pollutant precursors to disentangle the secondary effects, or conducted annual assessments for the US that dampens the influence of summertime peak biogenic emissions on atmospheric chemistry and air pollution.

Public health concerns that our results raise include long-term exposure to traffic-related NO2 that has been linked to the increase in childhood asthma incidences by 1.26% for every 10 ppb increase in NO2, even at low concentrations (∼2 ppb) that end-use NO2 far exceeds in cities in the eastern US (Figure 3a).5,15,107 Long-term exposure to PM2.5 at concentrations typical of the eastern US (10-12 μg m–3; Figure S2a) increase the risk of all-cause premature mortality by 1% with a 1 μg m–3 increase in annual mean PM2.5, a threshold exceeded by almost half (48% area) the eastern US in summer (Figure 4d).108 Exposure to 0.3 ppb of end-use HCHO over a person’s statistical lifespan is associated with an increased cancer risk of ∼5-6 in a million,109 so would exceed 10 in a million in the isoprene-rich southeast US where end-use HCHO is at least 0.6 ppb (Figure 3b). End-use activities increase peak summer season MDA8 O3 well beyond the safe threshold of ∼32 ppb (Figure 3c), increasing the risk of premature mortality from chronic respiratory diseases by 6% for every 10 ppb increase in MDA8 O3.110,111 End-use MDA8 O3 in about 20% of eastern US exceeds 10 ppb. There is potential for substantial public health benefits from decline in oil and gas consumption, though only to the extent that cleaner alternatives adopted have limited unintended consequences on air quality. In that sense, our estimates represent upper-bounds of air quality improvements that could be achieved from policies that promote adoption of cleaner alternatives.

There are many emissions and model improvements that are needed to further refine understanding of the implications of oil and gas end-use activity emissions on summertime air quality. These include: (1) guidance from the US EPA on characterizing NEI “Other PM2.5” emissions, (2) addressing the cause of the model bias in pNO3 and pNH4 to avoid reliance on dense ground-based monitoring networks to derive correction factors and to utilize evidence of variable toxicity of individual PM2.5 components in burden of disease studies,112,113 (3) explicitly represent pathways from the suite of VOCs to anthropogenic SOA, as is being developed for VCPs,13 and (4) mechanistic representation of gas- and aerosol-phase chemistry of biogenic VOCs like monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes and the complex interactions between isoprene SOA and monoterpene SOA.114

Nonetheless, our results suggest that reducing the use of processed and unprocessed oil and natural gas in the eastern US has the potential to significantly benefit public health by simultaneously decreasing concentrations of multiple harmful pollutants emitted directly as POA, generated as anthropogenic SOA, formed as O3 and HCHO from large influence of end-use NOx on the oxidative fate of biogenic isoprene, and formed as pNH4 from partitioning of agricultural sources of NH3. These effects are examined for the summertime in the eastern US, but are likely to persist year-round in the tropics where fossil fuels are already a dominant energy source,115 where oil and gas demand is growing rapidly, particularly across Africa,116,117 and where effective environmental policies are lacking and barriers to adopting cleaner sources of energy persist. There are large sources of uncertainty and measurement and data collection gaps in the tropics that need to be addressed to similarly determine the complex pathways degrading air quality from interaction between oil and gas end-use activity and isoprene emissions.

Data Availability Statement

The gridded hourly July 2017 end-use emissions generated using NEI SCC codes are available for download from the NOAA data portal (https://csl.noaa.gov/groups/csl7/measurements/2020covid-aqs/emissions/).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.4c10032.

Supporting Information includes the detailed evaluation of the GEOS-Chem model and a tabulated list of activities classified as oil and gas end-use (PDF)

Author Present Address

⊥ Centre for Research and Clean Air, Helsinki 100810, Finland

This research has been supported by The Schmidt Family Foundation’s 11th Hour Project program and European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (through the Starting Grant awarded to Eloise A. Marais, UpTrop (grant no. 851854)).

Confidential manuscript submitted to ES&T.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Anenberg S. C.; Miller J.; Minjares R.; Du L.; Henze D. K.; Lacey F.; Malley C. S.; Emberson L.; Franco V.; Klimont Z.; Heyes C. Impacts and mitigation of excess diesel-related NOx emissions in 11 major vehicle markets. Nature 2017, 545 (7655), 467–471. 10.1038/nature22086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvile R. N.; Hutchinson E. J.; Mindell J. S.; Warren R. F. The transport sector as a source of air pollution. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35 (9), 1537–1565. 10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00551-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R. N.; Li H.; Chen T. Q.; Hou B. D. How does natural gas consumption affect human health? Empirical evidence from China. J. Cleaner Prod. 2021, 320, 128795. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield E. N.; Cohon J. L.; Muller N. Z.; Azevedo I. M. L.; Robinson A. L. Cumulative environmental and employment impacts of the shale gas boom. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2 (12), 1122–1131. 10.1038/s41893-019-0420-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achakulwisut P.; Brauer M.; Hystad P.; Anenberg S. C. Global, national, and urban burdens of paediatric asthma incidence attributable to ambient NO2 pollution: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet Health 2019, 3 (4), E166–E178. 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Dept of Energy . U.S. OIL AND NATURAL GAS: Providing Energy Security and Supporting Our Quality of Life. 2020. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/10/f79/NaturalGasBenefitsReport.pdf. accessed 3 June 2024.

- US EIA . U.S. energy facts explained, 2022. https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/. accessed 3 March 2024.

- Harkins C.; McDonald B. C.; Henze D. K.; Wiedinmyer C. A fuel-based method for updating mobile source emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16 (6), 065018. 10.1088/1748-9326/ac0660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fine P. M.; Sioutas C.; Solomon P. A. Secondary particulate matter in the United States: Insights from the particulate matter supersites program and related studies. J. Air Waste Manage 2008, 58 (2), 234–253. 10.3155/1047-3289.58.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park R. J.; Jacob D. J.; Field B. D.; Yantosca R. M.; Chin M.. Natural and transboundary pollution influences on sulfate-nitrate-ammonium aerosols in the United States: Implications for policy. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2004, 109( (D15), ). 10.1029/2003JD004473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B. C.; de Gouw J. A.; Gilman J. B.; Jathar S. H.; Akherati A.; Cappa C. D.; Jimenez J. L.; Lee-Taylor J.; Hayes P. L.; McKeen S. A.; Cui Y. Y.; Kim S. W.; Gentner D. R.; Isaacman-VanWertz G.; Goldstein A. H.; Harley R. A.; Frost G. J.; Roberts J. M.; Ryerson T. B.; Trainer M. Volatile chemical products emerging as largest petrochemical source of urban organic emissions. Science 2018, 359 (6377), 760–764. 10.1126/science.aaq0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer K. M.; Pennington E.; Rao V.; Murphy B. N.; Strum M.; Isaacs K. K.; Pye H. O. T. Reactive organic carbon emissions from volatile chemical products. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21 (6), 5079–5100. 10.5194/acp-21-5079-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington E. A.; Seltzer K. M.; Murphy B. N.; Qin M. M.; Seinfeld J. H.; Pye H. O. T. Modeling secondary organic aerosol formation from volatile chemical products. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21 (24), 18247–18261. 10.5194/acp-21-18247-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasidharan S.; He Y. C.; Akherati A.; Li Q.; Li W. H.; Cocker D.; McDonald B. C.; Coggon M. M.; Seltzer K. M.; Pye H. O. T.; Pierce J. R.; Jathar S. H. Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation from Volatile Chemical Product Emissions: Model Parameters and Contributions to Anthropogenic Aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57 (32), 11891–11902. 10.1021/acs.est.3c00683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khreis H.; Kelly C.; Tate J.; Parslow R.; Lucas K.; Nieuwenhuijsen M. Exposure to traffic-related air pollution and risk of development of childhood asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 2017, 100, 1–31. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer M.; Brook J. R.; Crouse D.; Erickson A.; Hystad P.; Li C.; Martin R.; Meng J.; Tjepkema M.; van Donkelaar A.; Christidis T.; Pinault L. L.; Yuchi W.; Weagle C.; Weichenthal S.; Burnett R.; Burnett R. T. Air pollution impacts at very low levels: Shape of the concentration-mortality relationship in a large population-based Canadian cohort. Res. Rep. - Health Eff. Inst. 2022, 2022 (1), 1–91. 10.1289/isee.2022.p-0237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett R.; Chen H.; Szyszkowicz M.; Fann N.; Hubbell B.; Pope C. A.; Apte J. S.; Brauer M.; Cohen A.; Weichenthal S.; Coggins J.; Di Q.; Brunekreef B.; Frostad J.; Lim S. S.; Kan H. D.; Walker K. D.; Thurston G. D.; Hayes R. B.; Lim C. C.; Turner M. C.; Jerrett M.; Krewski D.; Gapstur S. M.; Diver W. R.; Ostro B.; Goldberg D.; Crouse D. L.; Martin R. V.; Peters P.; Pinault L.; Tjepkema M.; van Donkelaar A.; Villeneuve P. J.; Miller A. B.; Yin P.; Zhou M. G.; Wang L. J.; Janssen N. A. H.; Marra M.; Atkinson R. W.; Tsang H.; Quoc Thach T.; Cannon J. B.; Allen R. T.; Hart J. E.; Laden F.; Cesaroni G.; Forastiere F.; Weinmayr G.; Jaensch A.; Nagel G.; Concin H.; Spadaro J. V. Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, 115 (38), 9592–9597. 10.1073/pnas.1803222115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohra K.; Vodonos A.; Schwartz J.; Marais E. A.; Sulprizio M. P.; Mickley L. J. Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110754. 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore J. J.; Reka S.; Yang D.; Chang C.; Roy A.; Thompson T.; Lyon D.; McVay R.; Michanowicz D.; Arunachalam S. Air pollution and health impacts of oil & gas production in the United States. Environ. Res. Health 2023, 1 (2), 021006. 10.1088/2752-5309/acc886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fann N.; Baker K. R.; Chan E. A. W.; Eyth A.; Macpherson A.; Miller E.; Snyder J. Assessing Human Health PM2.5 and Ozone Impacts from US Oil and Natural Gas Sector Emissions in 2025. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52 (15), 8095–8103. 10.1021/acs.est.8b02050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D. T. Emissions from oil and gas operations in the United States and their air quality implications. J. Air Waste Manage 2016, 66 (6), 549–575. 10.1080/10962247.2016.1171263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field R. A.; Soltis J.; Murphy S. Air quality concerns of unconventional oil and natural gas production. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2014, 16 (5), 954–969. 10.1039/C4EM00081A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T. M.; Shepherd D.; Stacy A.; Barna M. G.; Schichtel B. A. Modeling to Evaluate Contribution of Oil and Gas Emissions to Air Pollution. J. Air Waste Manage 2017, 67 (4), 445–461. 10.1080/10962247.2016.1251508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohra K.; Marais E. A.; Bloss W. J.; Schwartz J.; Mickley L. J.; Van Damme M.; Clarisse L.; Coheur P. F.. Rapid rise in premature mortality due to anthropogenic air pollution in fast-growing tropical cities from 2005 to 2018. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8( (14), ). 10.1126/sciadv.abm4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoornweg D.; Pope K. Population predictions for the world’s largest cities in the 21st century. Environ. Urban 2017, 29 (1), 195–216. 10.1177/0956247816663557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer C. L.; Cervone G.; Golbazi M.; Al Fahel N.; Hultquist C. Changes in air quality and human mobility in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bull. Atmos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 1 (3–4), 491–514. 10.1007/s42865-020-00019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D. L.; Anenberg S. C.; Griffin D.; McLinden C. A.; Lu Z. F.; Streets D. G.. Disentangling the Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdowns on Urban NO2 From Natural Variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47( (17), ). 10.1029/2020GL089269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J. D.; Ebisu K. Changes in U.S. air pollution during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139864. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J.; Harkins C.; O’Dell K.; Li M.; Francoeur C.; Aikin K. C.; Anenberg S.; Baker B.; Brown S. S.; Coggon M. M.; Frost G. J.; Gilman J. B.; Kondragunta S.; Lamplugh A.; Lyu C.; Moon Z.; Pierce B. R.; Schwantes R. H.; Stockwell C. E.; Warneke C.; Yang K.; Nowlan C. R.; González Abad G.; McDonald B. C. COVID-19 perturbation on US air quality and human health impact assessment. PNAS Nexus 2023, 3 (1), pgad483. 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer M. S.; van Donkelaar A.; Martin R. V.; McDuffie E. E.; Lyapustin A.; Sayer A. M.; Hsu N. C.; Levy R. C.; Garay M. J.; Kalashnikova O. V.; Kahn R. A.. Effects of COVID-19 lockdowns on fine particulate matter concentrations. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7( (26), ). 10.1126/sciadv.abg7670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremanloo M.; Lops Y.; Choi Y.; Jung J.; Mousavinezhad S.; Hammond D. A comprehensive study of the COVID-19 impact on PM2.5 levels over the contiguous United States: A deep learning approach. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 272, 118944. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2022.118944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar S.; Parida B. R.; Mandal S. P.; Pandey A. C.; Kumar N.; Mishra B. Impacts of partial to complete COVID-19 lockdown on NO2 and PM2.5 levels in major urban cities of Europe and USA. Cities 2021, 117, 103308. 10.1016/j.cities.2021.103308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P. C.; Tong D.; Tang Y. H.; Baker B.; Lee P.; Saylor R.; Stein A.; Ma S. Q.; Lamsal L.; Qu Z. Impacts of the COVID-19 economic slowdown on ozone pollution in the U. S. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 264, 118713. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder H. E.; Fiore A. M.; Polvani L. M.; Lamarque J. F.; Fang Y. Changes in the frequency and return level of high ozone pollution events over the eastern United States following emission controls. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8 (1), 014012. 10.1088/1748-9326/8/1/014012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther A. B.; Jiang X.; Heald C. L.; Sakulyanontvittaya T.; Duhl T.; Emmons L. K.; Wang X. The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): an extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012, 5 (6), 1471–1492. 10.5194/gmd-5-1471-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marais E. A.; Jacob D. J.; Jimenez J. L.; Campuzano-Jost P.; Day D. A.; Hu W.; Krechmer J.; Zhu L.; Kim P. S.; Miller C. C.; Fisher J. A.; Travis K.; Yu K.; Hanisco T. F.; Wolfe G. M.; Arkinson H. L.; Pye H. O. T.; Froyd K. D.; Liao J.; McNeill V. F. Aqueous-phase mechanism for secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene: application to the southeast United States and co-benefit of SO2 emission controls. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16 (3), 1603–1618. 10.5194/acp-16-1603-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettke P.; Brüggemann M.; Mutzel A.; Gräfe R.; Herrmann H. Secondary Organic Aerosol (SOA) through Uptake of Isoprene Hydroxy Hydroperoxides (ISOPOOH) and its Oxidation Products. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2023, 7 (5), 1025–1037. 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.2c00385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. W.; Palm B. B.; Day D. A.; Campuzano-Jost P.; Krechmer J. E.; Peng Z.; de Sá S. S.; Martin S. T.; Alexander M. L.; Baumann K.; Hacker L.; Kiendler-Scharr A.; Koss A. R.; de Gouw J. A.; Goldstein A. H.; Seco R.; Sjostedt S. J.; Park J. H.; Guenther A. B.; Kim S.; Canonaco F.; Prévôt A. S. H.; Brune W. H.; Jimenez J. L. Volatility and lifetime against OH heterogeneous reaction of ambient isoprene-epoxydiols-derived secondary organic aerosol (IEPOX-SOA). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16 (18), 11563–11580. 10.5194/acp-16-11563-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe G. M.; Kaiser J.; Hanisco T. F.; Keutsch F. N.; de Gouw J. A.; Gilman J. B.; Graus M.; Hatch C. D.; Holloway J.; Horowitz L. W.; Lee B. H.; Lerner B. M.; Lopez-Hilifiker F.; Mao J.; Marvin M. R.; Peischl J.; Pollack I. B.; Roberts J. M.; Ryerson T. B.; Thornton J. A.; Veres P. R.; Warneke C. Formaldehyde production from isoprene oxidation across NOx regimes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16 (4), 2597–2610. 10.5194/acp-16-2597-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais E. A.; Jacob D. J.; Kurosu T. P.; Chance K.; Murphy J. G.; Reeves C.; Mills G.; Casadio S.; Millet D. B.; Barkley M. P.; Paulot F.; Mao J. Isoprene emissions in Africa inferred from OMI observations of formaldehyde columns. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12 (14), 6219–6235. 10.5194/acp-12-6219-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krechmer J. E.; Coggon M. M.; Massoli P.; Nguyen T. B.; Crounse J. D.; Hu W. W.; Day D. A.; Tyndall G. S.; Henze D. K.; Rivera-Rios J. C.; Nowak J. B.; Kimmel J. R.; Mauldin R. L.; Stark H.; Jayne J. T.; Sipilä M.; Junninen H.; St Clair J. M.; Zhang X.; Feiner P. A.; Zhang L.; Miller D. O.; Brune W. H.; Keutsch F. N.; Wennberg P. O.; Seinfeld J. H.; Worsnop D. R.; Jimenez J. L.; Canagaratna M. R. Formation of Low Volatility Organic Compounds and Secondary Organic Aerosol from Isoprene Hydroxyhydroperoxide Low-NO Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49 (17), 10330–10339. 10.1021/acs.est.5b02031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates K. H.; Jacob D. J. A new model mechanism for atmospheric oxidation of isoprene: global effects on oxidants, nitrogen oxides, organic products, and secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19 (14), 9613–9640. 10.5194/acp-19-9613-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budisulistiorini S. H.; Li X.; Bairai S. T.; Renfro J.; Liu Y.; Liu Y. J.; McKinney K. A.; Martin S. T.; McNeill V. F.; Pye H. O. T.; Nenes A.; Neff M. E.; Stone E. A.; Mueller S.; Knote C.; Shaw S. L.; Zhang Z.; Gold A.; Surratt J. D. Examining the effects of anthropogenic emissions on isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol formation during the 2013 Southern Oxidant and Aerosol Study (SOAS) at the Look Rock, Tennessee ground site. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15 (15), 8871–8888. 10.5194/acp-15-8871-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. J.; Guo H. Y.; Russell A. G.; Nenes A. High aerosol acidity despite declining atmospheric sulfate concentrations over the past 15 years. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9 (4), 282–285. 10.1038/ngeo2665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawal A. S.; Guan X. B.; Liu C.; Henneman L. R. F.; Vasilakos P.; Bhogineni V.; Weber R. J.; Nenes A.; Russell A. G. Linked Response of Aerosol Acidity and Ammonia to SO2 and NOx Emissions Reductions in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52 (17), 9861–9873. 10.1021/acs.est.8b00711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. L.; Shen H. Z.; Russell A. G. Current and Future Responses of Aerosol pH and Composition in the US to Declining SO2 Emissions and Increasing NH3 Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53 (16), 9646–9655. 10.1021/acs.est.9b02005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nopmongcol U.; Beardsley R.; Kumar N.; Knipping E.; Yarwood G. Changes in United States deposition of nitrogen and sulfur compounds over five decades from 1970 to 2020. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 209, 144–151. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B. C.; McKeen S. A.; Cui Y. Y.; Ahmadov R.; Kim S. W.; Frost G. J.; Pollack I. B.; Peischl J.; Ryerson T. B.; Holloway J. S.; Graus M.; Warneke C.; Gilman J. B.; de Gouw J. A.; Kaiser J.; Keutsch F. N.; Hanisco T. F.; Wolfe G. M.; Trainer M. Modeling Ozone in the Eastern US using a Fuel-Based Mobile Source Emissions Inventory. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52 (13), 7360–7370. 10.1021/acs.est.8b00778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; McDonald B. C.; McKeen S. A.; Eskes H.; Levelt P.; Francoeur C.; Harkins C.; He J.; Barth M.; Henze D. K.; Bela M. M.; Trainer M.; de Gouw J. A.; Frost G. J.. Assessment of Updated Fuel-Based Emissions Inventories Over the Contiguous United States Using TROPOMI NO2 Retrievals. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2021, 126( (24), ). 10.1029/2021JD035484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K. A.; McDonald B. C.; Harley R. A. Evaluation of Nitrogen Oxide Emission Inventories and Trends for On-Road Gasoline and Diesel Vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55 (10), 6655–6664. 10.1021/acs.est.1c00586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone N. W.; Stettler M. E. J.; Barrett S. R. H. Rapid estimation of global civil aviation emissions with uncertainty quantification. Transp. Res. D Trans. Environ. 2013, 25, 33–41. 10.1016/j.trd.2013.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stettler M. E. J.; Eastham S.; Barrett S. R. H. Air quality and public health impacts of UK airports. Part I: Emissions. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45 (31), 5415–5424. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudman R. C.; Moore N. E.; Mebust A. K.; Martin R. V.; Russell A. R.; Valin L. C.; Cohen R. C. Steps towards a mechanistic model of global soil nitric oxide emissions: implementation and space based-constraints. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12 (16), 7779–7795. 10.5194/acp-12-7779-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaegle L.; Quinn P. K.; Bates T. S.; Alexander B.; Lin J. T. Global distribution of sea salt aerosols: new constraints from in situ and remote sensing observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11 (7), 3137–3157. 10.5194/acp-11-3137-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J.; Martin R. V.; Ginoux P.; Hammer M.; Sulprizio M. P.; Ridley D. A.; van Donkelaar A. Grid-independent high-resolution dust emissions (v1.0) for chemical transport models: application to GEOS-Chem. (12.5.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14 (7), 4249–4260. 10.5194/gmd-14-4249-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. T. Lightning NOx and Impacts on Air Quality. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2016, 2 (2), 115–133. 10.1007/s40726-016-0031-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoukis C.; Nenes A. ISORROPIA II:: a computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+-Ca2+-Mg2+-NH4+-Na+-SO42--NO3–-Cl–-H2O aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7 (17), 4639–4659. 10.5194/acp-7-4639-2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G.; Yu F. Q.; Schwab J. Revised treatment of wet scavenging processes dramatically improves GEOS-Chem. 12.0.0 simulations of surface nitric acid, nitrate, and ammonium over the United States. Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12 (8), 3439–3447. 10.5194/gmd-12-3439-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tie X. X.; Madronich S.; Walters S.; Edwards D. P.; Ginoux P.; Mahowald N.; Zhang R. Y.; Lou C.; Brasseur G.. Assessment of the global impact of aerosols on tropospheric oxidants. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2005, 110( (D3), ). 10.1029/2004JD005359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke W. F.; Liousse C.; Cachier H.; Feichter J. Construction of a 1° × 1° fossil fuel emission data set for carbonaceous aerosol and implementation and radiative impact in the ECHAM4 model. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 1999, 104 (D18), 22137–22162. 10.1029/1999jd900187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chin M.; Ginoux P.; Kinne S.; Torres O.; Holben B. N.; Duncan B. N.; Martin R. V.; Logan J. A.; Higurashi A.; Nakajima T. Tropospheric aerosol optical thickness from the GOCART model and comparisons with satellite and Sun photometer measurements. J. Atmos. Sci. 2002, 59 (3), 461–483. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pai S. J.; Heald C. L.; Pierce J. R.; Farina S. C.; Marais E. A.; Jimenez J. L.; Campuzano-Jost P.; Nault B. A.; Middlebrook A. M.; Coe H.; Shilling J. E.; Bahreini R.; Dingle J. H.; Vu K. An evaluation of global organic aerosol schemes using airborne observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20 (5), 2637–2665. 10.5194/acp-20-2637-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes P. L.; Carlton A. G.; Baker K. R.; Ahmadov R.; Washenfelder R. A.; Alvarez S.; Rappenglück B.; Gilman J. B.; Kuster W. C.; de Gouw J. A.; Zotter P.; Prévôt A. S. H.; Szidat S.; Kleindienst T. E.; Offenberg J. H.; Ma P. K.; Jimenez J. L. Modeling the formation and aging of secondary organic aerosols in Los Angeles during CalNex 2010. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15 (10), 5773–5801. 10.5194/acp-15-5773-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford B.; Heald C. L. Aerosol loading in the Southeastern United States: reconciling surface and satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13 (18), 9269–9283. 10.5194/acp-13-9269-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P. S.; Jacob D. J.; Fisher J. A.; Travis K.; Yu K.; Zhu L.; Yantosca R. M.; Sulprizio M. P.; Jimenez J. L.; Campuzano-Jost P.; Froyd K. D.; Liao J.; Hair J. W.; Fenn M. A.; Butler C. F.; Wagner N. L.; Gordon T. D.; Welti A.; Wennberg P. O.; Crounse J. D.; St Clair J. M.; Teng A. P.; Millet D. B.; Schwarz J. P.; Markovic M. Z.; Perring A. E. Sources, seasonality, and trends of southeast US aerosol: an integrated analysis of surface, aircraft, and satellite observations with the GEOS-Chem. chemical transport model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15 (18), 10411–10433. 10.5194/acp-15-10411-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McClenny W. A.; Williams E. J.; Cohen R. C.; Stutz J. Preparing to measure the effects of the NOx SIP call-methods for ambient air monitoring of NO, NO2, NOy, and individual NOz species. J. Air Waste Manage 2002, 52 (5), 542–562. 10.1080/10473289.2002.10470801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed C.; Evans M. J.; Di Carlo P.; Lee J. D.; Carpenter L. J. Interferences in photolytic NO2 measurements: explanation for an apparent missing oxidant?. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16 (7), 4707–4724. 10.5194/acp-16-4707-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell K.; Ford B.; Fischer E. V.; Pierce J. R. Contribution of Wildland-Fire Smoke to US PM2.5 and Its Influence on Recent Trends. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53 (4), 1797–1804. 10.1021/acs.est.8b05430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip S.; Martin R. V.; Pierce J. R.; Jimenez J. L.; Zhang Q.; Canagaratna M. R.; Spracklen D. V.; Nowlan C. R.; Lamsal L. N.; Cooper M. J.; Krotkov N. A. Spatially and seasonally resolved estimate of the ratio of organic mass to organic carbon. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 87, 34–40. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.11.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudman R. C.; Murray L. T.; Jacob D. J.; Millet D. B.; Turquety S.; Wu S.; Blake D. R.; Goldstein A. H.; Holloway J.; Sachse G. W.. Biogenic versus anthropogenic sources of CO in the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35( (4), ). 10.1029/2007GL032393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. M.; Matross D. M.; Andrews A. E.; Millet D. B.; Longo M.; Gottlieb E. W.; Hirsch A. I.; Gerbig C.; Lin J. C.; Daube B. C.; Hudman R. C.; Dias P. L. S.; Chow V. Y.; Wofsy S. C. Sources of carbon monoxide and formaldehyde in North America determined from high-resolution atmospheric data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2008, 8 (24), 7673–7696. 10.5194/acp-8-7673-2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dallmann T. R.; Harley R. A.. Evaluation of mobile source emission trends in the United States. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2010, 115. 10.1029/2010JD013862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dallmann T. R.; Kirchstetter T. W.; DeMartini S. J.; Harley R. A. Quantifying On-Road Emissions from Gasoline-Powered Motor Vehicles: Accounting for the Presence of Medium- and Heavy-Duty Diesel Trucks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47 (23), 13873–13881. 10.1021/es402875u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H. S.; Henze D. K.; Cady-Pereira K.; McDonald B. C.; Harkins C.; Sun K.; Bowman K. W.; Fu T. M.; Nawaz M. O. COVID-19 Lockdowns Afford the First Satellite-Based Confirmation That Vehicles Are an Under-recognized Source of Urban NH3 Pollution in Los Angeles. Environ. Sci. Tech Lett. 2022, 9 (1), 3–9. 10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore J. J.; Salimifard P.; Michanowicz D. R.; Allen J. G. A decade of the US energy mix transitioning away from coal: historical reconstruction of the reductions in the public health burden of energy. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16 (5), 054030. 10.1088/1748-9326/abe74c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D. R.; Isaacman G.; Worton D. R.; Chan A. W. H.; Dallmann T. R.; Davis L.; Liu S.; Day D. A.; Russell L. M.; Wilson K. R.; Weber R.; Guha A.; Harley R. A.; Goldstein A. H. Elucidating secondary organic aerosol from diesel and gasoline vehicles through detailed characterization of organic carbon emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109 (45), 18318–18323. 10.1073/pnas.1212272109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald C. L.; Collett J. L.; Lee T.; Benedict K. B.; Schwandner F. M.; Li Y.; Clarisse L.; Hurtmans D. R.; Van Damme M.; Clerbaux C.; Coheur P. F.; Philip S.; Martin R. V.; Pye H. O. T. Atmospheric ammonia and particulate inorganic nitrogen over the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12 (21), 10295–10312. 10.5194/acp-12-10295-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G.; Yu F. Q.; Moch J. M. Further improvement of wet process treatments in GEOS-Chem. v12.6.0: impact on global distributions of aerosols and aerosol precursors. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13 (6), 2879–2903. 10.5194/gmd-13-2879-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miao R. Q.; Chen Q.; Zheng Y.; Cheng X.; Sun Y. L.; Palmer P. I.; Shrivastava M.; Guo J. P.; Zhang Q.; Liu Y. H.; Tan Z. F.; Ma X. F.; Chen S. Y.; Zeng L. M.; Lu K. D.; Zhang Y. H. Model bias in simulating major chemical components of PM2.5 in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20 (20), 12265–12284. 10.5194/acp-20-12265-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liggio J.; Li S. M.; Vlasenko A.; Stroud C.; Makar P. Depression of Ammonia Uptake to Sulfuric Acid Aerosols by Competing Uptake of Ambient Organic Gases. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45 (7), 2790–2796. 10.1021/es103801g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvern R. F.; Jacob D. J.; Kim P. S.; Marais E. A.; Turner J. R.; Campuzano-Jost P.; Jimenez J. L. Inconsistency of ammonium-sulfate aerosol ratios with thermodynamic models in the eastern US: a possible role of organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17 (8), 5107–5118. 10.5194/acp-17-5107-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters J.; Müller J. F. HOx radical regeneration in isoprene oxidation via peroxy radical isomerisations. II: experimental evidence and global impact. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12 (42), 14227–14235. 10.1039/c0cp00811g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crounse J. D.; Paulot F.; Kjaergaard H. G.; Wennberg P. O. Peroxy radical isomerization in the oxidation of isoprene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13 (30), 13607–13613. 10.1039/c1cp21330j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Miller C.; Jacob D. J.; Marais E. A.; Yu K. R.; Travis K. R.; Kim P. S.; Fisher J. A.; Zhu L.; Wolfe G. M.; Hanisco T. F.; Keutsch F. N.; Kaiser J.; Min K. E.; Brown S. S.; Washenfelder R. A.; González Abad G.; Chance K. Glyoxal yield from isoprene oxidation and relation to formaldehyde: chemical mechanism, constraints from SENEX aircraft observations, and interpretation of OMI satellite data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17 (14), 8725–8738. 10.5194/acp-17-8725-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pye H. O. T.; D’Ambro E. L.; Lee B.; Schobesberger S.; Takeuchi M.; Zhao Y.; Lopez-Hilfiker F.; Liu J. M.; Shilling J. E.; Xing J.; Mathur R.; Middlebrook A. M.; Liao J.; Welti A.; Graus M.; Warneke C.; de Gouw J. A.; Holloway J. S.; Ryerson T. B.; Pollack I. B.; Thornton J. A. Anthropogenic enhancements to production of highly oxygenated molecules from autoxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116 (14), 6641–6646. 10.1073/pnas.1810774116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chameides W. L.; Lindsay R. W.; Richardson J.; Kiang C. S. The Role of Biogenic Hydrocarbons in Urban Photochemical Smog - Atlanta as a Case-Study. Science 1988, 241 (4872), 1473–1475. 10.1126/science.3420404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettiyadura A. P. S.; Al-Naiema I. M.; Hughes D. D.; Fang T.; Stone E. A. Organosulfates in Atlanta, Georgia: anthropogenic influences on biogenic secondary organic aerosol formation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19 (5), 3191–3206. 10.5194/acp-19-3191-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J.; Choi Y.; Mousavinezhad S.; Kang D. W.; Park J.; Pouyaei A.; Ghahremanloo M.; Momeni M.; Kim H. Changes in the ozone chemical regime over the contiguous United States inferred by the inversion of NOx and VOC emissions using satellite observation. Atmos. Res. 2022, 270, 106076. 10.1016/j.atmosres.2022.106076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody M. C.; Baker K. R.; Hayes P. L.; Jimenez J. L.; Koo B.; Pye H. O. T. Understanding sources of organic aerosol during CalNex-2010 using the CMAQ-VBS. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16 (6), 4081–4100. 10.5194/acp-16-4081-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodzic A.; Jimenez J. L. Modeling anthropogenically controlled secondary organic aerosols in a megacity: a simplified framework for global and climate models. Geosci. Model Dev. 2011, 4 (4), 901–917. 10.5194/gmd-4-901-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He M.; Ditto J. C.; Gardner L.; Machesky J.; Hass-Mitchell T. N.; Chen C.; Khare P.; Sahin B.; Fortner J. D.; Plata D. L.; Drollette B. D.; Hayden K. L.; Wentzell J. J. B.; Mittermeier R. L.; Leithead A.; Lee P.; Darlington A.; Wren S. N.; Zhang J.; Wolde M.; Moussa S. G.; Li S.-M.; Liggio J.; Gentner D. R. Total organic carbon measurements reveal major gaps in petrochemical emissions reporting. Science 2024, 383 (6681), 426–432. 10.1126/science.adj6233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder R. W.; Adams P. J.; Pandis S. N. Ammonia emission controls as a cost-effective strategy for reducing atmospheric particulate matter in the eastern United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41 (2), 380–386. 10.1021/es060379a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vayenas D. V.; Takahama S.; Davidson C. I.; Pandis S. N.. Simulation of the thermodynamics and removal processes in the sulfate-ammonia-nitric acid system during winter:: Implications for PM2.5 control strategies. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2005, 110( (D7), ). 10.1029/2004JD005038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L.; Jacob D. J.; Mickley L. J.; Marais E. A.; Cohan D. S.; Yoshida Y.; Duncan B. N.; González Abad G.; Chance K. V. Anthropogenic emissions of highly reactive volatile organic compounds in eastern Texas inferred from oversampling of satellite (OMI) measurements of HCHO columns. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9 (11), 114004. 10.1088/1748-9326/9/11/114004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J. M.; Marais E. A.; Lu G.; Obszynska J.; Mace M.; White J.; Leigh R. J. Diagnosing domestic and transboundary sources of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in UK cities using GEOS-Chem. City Environ. Interac. 2023, 18, 100100. 10.1016/j.cacint.2023.100100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind A. L.; Tessum C. W.; Coggins J. S.; Hill J. D.; Marshall J. D. Fine-scale damage estimates of particulate matter air pollution reveal opportunities for location-specific mitigation of emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116 (18), 8775–8780. 10.1073/pnas.1816102116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anenberg S. C.; Mohegh A.; Goldberg D. L.; Kerr G. H.; Brauer M.; Burkart K.; Hystad P.; Larkin A.; Wozniak S.; Lamsal L. Long-term trends in urban NO2 concentrations and associated paediatric asthma incidence: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6 (1), E49–E58. 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais E. A.; Kelly J. M.; Vohra K.; Li Y.; Lu G.; Hina N.; Rowe E. C. Impact of Legislated and Best Available Emission Control Measures on UK Particulate Matter Pollution, Premature Mortality, and Nitrogen-Sensitive Habitats. GeoHealth 2023, 7 (10), e2023GH000910 10.1029/2023GH000910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh M. M.; Levy J. I.; Spengler J. D.; Houseman E. A.; Bennett D. H. Ranking cancer risks of organic hazardous air pollutants in the United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115 (8), 1160–1168. 10.1289/ehp.9884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. J. L.; Aravkin A. Y.; Zheng P.; Abbafati C.; Abbas K. M.; Abbasi-Kangevari M.; Abd-Allah F.; Abdelalim A.; Abdollahi M.; Abdollahpour L.; et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020, 396 (10258), 1223–1249. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malashock D. A.; DeLang M. N.; Becker J. S.; Serre M. L.; West J. J.; Chang K. L.; Cooper O. R.; Anenberg S. C. Estimates of ozone concentrations and attributable mortality in urban, peri-urban and rural areas worldwide in 2019. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17 (5), 054023. 10.1088/1748-9326/ac66f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao H.; Wang Y. F.; Zhu Q.; Zhang H. S.; Rosenberg A.; Schwartz J.; Amini H.; van Donkelaar A.; Martin R.; Liu P. F.; Weber R.; Russel A.; Yitshak-sade M.; Chang H.; Shi L. H. National Cohort Study of Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5 Components and Mortality in Medicare American Older Adults. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57 (17), 6835–6843. 10.1021/acs.est.2c07064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. F.; Xiao S. Y.; Zhang Y. H.; Chang H.; Martin R. V.; Van Donkelaar A.; Gaskins A.; Liu Y.; Liu P. F.; Shi L. H. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 major components and mortality in the southeastern United States. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106969. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFiggans G.; Mentel T. F.; Wildt J.; Pullinen I.; Kang S.; Kleist E.; Schmitt S.; Springer M.; Tillmann R.; Wu C.; Zhao D. F.; Hallquist M.; Faxon C.; Le Breton M.; Hallquist Å. M.; Simpson D.; Bergström R.; Jenkin M. E.; Ehn M.; Thornton J. A.; Alfarra M. R.; Bannan T. J.; Percival C. J.; Priestley M.; Topping D.; Kiendler-Scharr A. Secondary organic aerosol reduced by mixture of atmospheric vapours. Nature 2019, 565 (7741), 587–593. 10.1038/s41586-018-0871-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharvini S. R.; Noor Z. Z.; Chong C. S.; Stringer L. C.; Yusuf R. O. Energy consumption trends and their linkages with renewable energy policies in East and Southeast Asian countries: Challenges and opportunities. Sustainable Environ. Res. 2018, 28, 257–266. 10.1016/j.serj.2018.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marais E. A.; Silvern R. F.; Vodonos A.; Dupin E.; Bockarie A. S.; Mickley L. J.; Schwartz J. Air quality and health impact of future fossil fuel use for electricity generation and transport in Africa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 13524–13534. 10.1021/acs.est.9b04958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLOCAT . Africa – SLOCAT Transport and Climate Change Global Status Report. 2021. https://tcc-gsr.com/global-overview/africa/. accessed 10 July 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The gridded hourly July 2017 end-use emissions generated using NEI SCC codes are available for download from the NOAA data portal (https://csl.noaa.gov/groups/csl7/measurements/2020covid-aqs/emissions/).