Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the prevalence and prognostic role of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB) in patients with non-immunotherapy-treated advanced cervical cancer.

Methods

Clinical data were retrospectively collected from medical records between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2016, at Asan Medical Center (Korea); archived tumor samples were assessed for PD-L1 expression (combined positive score [CPS] ≥1) and TMB (≥175 mutations/exome). Overall survival (OS) was defined as time from advanced diagnosis or initiation of first-line or second-line systemic therapy until death/last follow-up. The association of OS with PD-L1 expression and TMB were analyzed using the log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for covariates.

Results

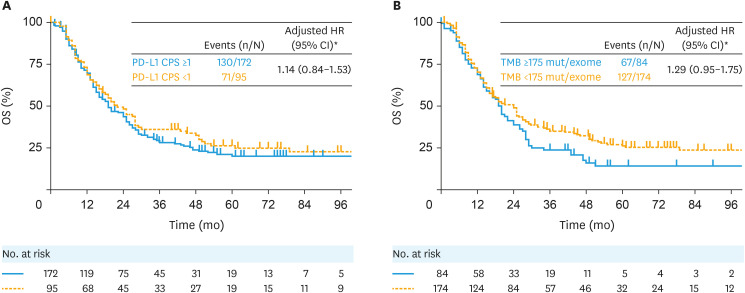

Of 267 patients, 76.0% had squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 24.0% had adenocarcinoma (AC)/adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC), 64.4% had PD-L1 CPS ≥1, and 32.6% had TMB ≥175 mutations/exome. PD-L1 CPS ≥1 and TMB ≥175 mutations/exome were more prevalent in SCC than in AC/ASC (73.9% and 37.2% vs. 34.4% and 17.7%). There was no association between OS and PD-L1 expression (CPS ≥1 vs. <1: adjusted hazard ratio [HR]=1.14; 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.84–1.53 from advanced diagnosis); OS trended shorter for the subgroup with TMB ≥175 versus <175 mutations/exome (adjusted HR=1.29; 95% CI=0.95–1.75).

Conclusion

Retrospective analysis of non-immunotherapy-treated patients with advanced cervical cancer demonstrated a higher prevalence of PD-L1 CPS ≥1 and TMB ≥175 mutations/exome in SCC versus AC/ASC. PD-L1 CPS ≥1 was not associated with OS; TMB ≥175 mutations/exome showed a trend toward shorter OS. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Cervical Cancer, PD-L1 Protein

Synopsis

Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB) were evaluated in non–immunotherapy-treated patients with advanced cervical cancer. Overall, 64.4% were PD-L1 positive (combined positive score [CPS] ≥1) and 32.6% had TMB ≥175 mutations/exome. PD-L1 CPS ≥1 was not associated with overall survival (OS). TMB ≥175 mutations/exome showed a trend toward shorter OS in patients with advanced cervical cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women worldwide [1]. Chemotherapy with or without the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody bevacizumab has been the standard-of-care for patients with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer for several years [2]. Recently, the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab showed efficacy benefit as first-line treatment in the all-comer population of the phase 3 KEYNOTE-826 trial in patients with persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer; the efficacy benefit was also observed in the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1)-positive population (combined positive score [CPS] ≥1) [3].

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, the cause of most cervical cancers [4], can activate the PD-L1 pathway, resulting in upregulated expression of PD-L1 in malignant squamous cells of the cervix [5]. PD-L1 expression is an adaptive mechanism of immune escape by cervical carcinomas and such tumors are associated with a poor prognosis [6,7]. At present, limited data have been reported on the prevalence and prognostic role of PD-L1 expression in patients with advanced cervical cancer. The prevalence of PD-L1-positivity (CPS ≥1) in patients with advanced cervical cancer was 83.7% in the phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 trial [8] and 88.8% (including 51.4% with PD-L1 CPS ≥10) in the phase 3 KEYNOTE-826 trial [3]. Among patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with radical chemoradiotherapy (95.6% of patient samples expressed PD-L1 [tumor proportion score >0%] and 87.9% had a PD-L1 tumor proportion score ≥1%), the expression of PD-L1 was not associated with progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) [9].

HPV-induced master regulators may also play crucial roles in relation to mutation and neoantigen load as well as the immune microenvironment of cervical tumors [10]. Tumor mutations may generate a large proportion of immunogenic neoantigens that may be associated with response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [11]. Tumor mutational burden (TMB; the total number of somatic nonsynonymous mutations per coding area of a tumor genome), is an emerging prognostic biomarker in advanced tumors [12,13,14]. A computational study showed that patients with TMB-high (≥ median) cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) may have a favorable prognosis [15]. In the multi-cohort KEYNOTE-158 study, which included patients with cervical cancer, patients with TMB ≥175 mutations/exome (concordant with ≥10 mut/Mb via FoundationOne® CDx [16]) were identified as a possible subgroup with a robust tumor response to pembrolizumab [17].

Although immunotherapy-based combination therapy is an effective treatment option for advanced cervical cancer, especially when PD-L1 expression and TMB status are known, the independent prognostic value of PD-L1 expression and TMB status in patients with advanced cervical cancer not previously treated with immunotherapy is unclear. There is a need to assess the extent to which PD-L1 and TMB influence prognosis without the potential cofounding effects of immunotherapy. In this retrospective study, we evaluated the real-world prevalence and prognostic value of PD-L1 expression and TMB status in patients with advanced (persistent, recurrent, or metastatic) cervical cancer that had not been treated with immunotherapy at any point in their treatment course.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design and patients

This was a retrospective, noninterventional study conducted at Asan Medical Center, Korea. Eligibility criteria included age ≥18 years on the date of diagnosis with advanced (persistent [disease that did not respond to prior treatment], recurrent [disease that initially responded to treatment but returned or progressed], or metastatic [disease that had spread at the time of diagnosis]) cervical cancer; histological subtype of SCC, adenocarcinoma (AC), or adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC); a diagnosis given between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2016; and sufficient formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue to produce ≥11 slides. Patients with locally advanced cervical tumors were included if they met the persistent, recurrent, or metastatic disease criteria. Patients with other primary malignant tumor types <1 year prior to diagnosis of advanced cervical cancer; lack of available data for OS analysis; who were treated before or during follow-up with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor (none of which were regulatory approved in Korea during the study period and, thus, were not considered standard-of-care); and were participating in an ongoing clinical trial were excluded. The retrieval of data, medical charts, and tissue samples was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (approval number: 2018-1573).

2. Outcomes and assessments

The objectives of this study were to characterize the tumor PD-L1 expression and TMB status, as well as each biomarker’s clinical impact (OS) in patients with advanced cervical cancer overall and by other key demographic, clinicopathologic, and key treatment parameters. The association of PD-L1 and TMB with real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) and the association of biomarker prevalence with OS in different subgroups were evaluated.

Demographic information, treatment history, and disease outcomes were collected from electronic medical records. OS was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis with advanced disease to death or loss to follow-up. Additionally, OS from first-line and second-line systemic therapy initiation (where applicable) to death or loss to follow-up were also calculated. Patients without documented death at the time of the last follow-up were censored.

PFS was calculated from first-line and second-line systemic therapy initiation (where applicable). Patients without documented disease progression or death at the time of the last follow-up were censored.

Biomarker testing of archived tumor samples was performed at a central laboratory (NeoGenomics, Fort Myers, FL, USA). PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry was assessed using PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Carpinteria, CA, USA) and scored using CPS (defined as the number of PD-L1-staining cells [tumor cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages] divided by total number of viable tumor cells evaluated, multiplied by 100). PD-L1 positivity was defined as CPS ≥1.

TMB was assessed by whole exome sequencing (WES) using SureSelect XT All Exon Target Enrichment System (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The methods for TMB analysis via WES have been previously published [14]. TMB was defined as the number of somatic nonsynonymous single nucleotide variants and indels that met predetermined criteria as previously described [14,18].

TMB was assessed using a cutoff of 175 mutations/exome (≥175 vs. <175 mutations/exome; concordant with 10 mut/Mb via FoundationOne® CDx [16]). The prognostic effects of PD-L1 and TMB were assessed separately as dichotomized variables without adjusting for the other.

3. Statistical analyses

Baseline demographic, clinical, and pathological characteristics were compared according to biomarker expression level (PD-L1 CPS ≥1 vs. <1 and TMB ≥175 vs. <175 mutations/exome) using a χ2 test. The association between PD-L1 and TMB was assessed using a χ2 test. The association between each clinical outcome and each biomarker was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves, log-rank test, and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for covariates of interest.

RESULTS

1. Patients

Between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2016, a total of 1,006 adult patients with advanced cervical cancer were retrospectively identified and screened for eligibility (Fig. S1). Samples from 280 eligible patients were identified and collected. After the exclusion of duplications (n=3) and non-evaluable samples (n=10), samples from 267 patients were included in this analysis. The median age at the time of advanced cervical cancer diagnosis was 47 years. Most patients had SCC (76.0%), early-stage (I/II) disease at initial diagnosis (77.5%), and recurrent disease (80.9%) (Table 1). There were 224 patients (83.9%) who had received first-line therapy and 169 patients (75.4%) who had received second-line therapy. The most common first-line treatments were carboplatin/paclitaxel (62.2%), cisplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab (16.7%), and cisplatin/paclitaxel (12.6%). Median follow-up from advanced cervical cancer diagnosis was 20 months (range, 17–25).

Table 1. Prevalence of PD-L1 expression and TMB by disease characteristics and prior treatment.

| Variables | All patients | PD-L1 expression | TMB status* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPS ≥1 | CPS<1 | p-value† | ≥175 mutations/exome | <175 mutations/exome | p-value† | |||

| Overall | 267 (100.0) | 172 (64.4) | 95 (35.6) | Not applicable | 84 (32.6) | 174 (67.4) | Not applicable | |

| Histology | <0.001 | 0.004 | ||||||

| SCC | 203 (76.0) | 150 (73.9) | 53 (26.1) | 73 (37.2) | 123 (62.8) | |||

| AC/ASC | 64 (24.0) | 22 (34.4) | 42 (65.6) | 11 (17.7) | 51 (82.3) | |||

| Stage at initial cervical cancer diagnosis‡ | 0.106 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Stages I and II | 207 (77.5) | 137 (66.2) | 70 (33.8) | 56 (28.3) | 142 (71.7) | |||

| Stages III and IV | 52 (19.5) | 32 (61.5) | 20 (38.5) | 25 (48.1) | 27 (51.9) | |||

| Stage at tissue collection§ | 0.259 | 0.045 | ||||||

| Stages I and II | 141 (52.8) | 97 (68.8) | 44 (31.2) | 35 (25.9) | 100 (74.1) | |||

| Stages III and IV | 46 (17.2) | 30 (65.2) | 16 (34.8) | 21 (45.7) | 25 (54.3) | |||

| Other‖ | 78 (29.2) | 44 (56.4) | 34 (43.6) | 27 (36.0) | 48 (64.0) | |||

| Age at advanced cervical cancer diagnosis | 0.054 | 0.512 | ||||||

| <65 years | 238 (89.1) | 158 (66.4) | 80 (33.6) | 73 (31.9) | 156 (68.1) | |||

| ≥65 years | 29 (10.9) | 14 (48.3) | 15 (51.7) | 11 (37.9) | 18 (62.1) | |||

| Disease state | 1.000 | 0.069 | ||||||

| Recurrent | 216 (80.9) | 139 (64.4) | 77 (35.6) | 60 (28.8) | 148 (71.2) | |||

| Persistent | 17 (6.4) | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | |||

| Metastatic | 34 (12.7) | 22 (64.7) | 12 (35.3) | 18 (52.9) | 16 (47.1) | |||

| Grade¶ | 0.098 | 0.241 | ||||||

| 1 or 2 | 179 (67.0) | 113 (63.1) | 66 (36.9) | 58 (33.3) | 116 (66.7) | |||

| 3 | 56 (21.0) | 42 (75.0) | 14 (25.0) | 13 (24.5) | 40 (75.5) | |||

| HPV infection** | 0.784 | 0.328 | ||||||

| Yes | 76 (28.5) | 50 (65.8) | 26 (34.2) | 20 (27.0) | 54 (73.0) | |||

| No | 32 (12.0) | 22 (68.8) | 10 (31.3) | 9 (28.1) | 23 (71.9) | |||

| Surgery prior to advanced cervical cancer diagnosis | 0.267 | 0.066 | ||||||

| Yes | 174 (65.2) | 116 (66.7) | 58 (33.3) | 44 (26.3) | 123 (73.7) | |||

| No | 58 (21.7) | 34 (58.6) | 24 (41.4) | 22 (39.3) | 34 (60.7) | |||

| Radiation prior to advanced cervical cancer diagnosis | 0.065 | 0.211 | ||||||

| Yes | 37 (13.9) | 19 (51.4) | 18 (48.6) | 7 (20.6) | 27 (79.4) | |||

| No | 195 (73.0) | 131 (67.2) | 64 (32.8) | 59 (31.2) | 130 (68.8) | |||

| Chemoradiation prior to advanced cervical cancer diagnosis | 0.473 | 0.063 | ||||||

| Yes | 129 (48.3) | 86 (66.7) | 43 (33.3) | 43 (34.7) | 81 (65.3) | |||

| No | 103 (38.6) | 64 (62.1) | 39 (37.9) | 23 (23.2) | 76 (76.8) | |||

| (Neo)adjuvant treatment prior to advanced cervical cancer diagnosis | 0.559 | 0.965 | ||||||

| Yes | 59 (22.1) | 40 (67.8) | 19 (32.2) | 17 (29.8) | 40 (70.2) | |||

| No | 173 (64.8) | 110 (63.6) | 63 (36.4) | 49 (29.5) | 117 (70.5) | |||

Advanced cervical cancer refers to persistent, recurrent, or metastatic disease. Values are presented as number (prevalence, %). Bold-faced p-values indicate statistically significant.

AC, adenocarcinoma; ASC, adenosquamous carcinoma; CPS, combined positive score; HPV, human papillomavirus; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; TMB, tumor mutational burden.

*Two hundred fifty-eight patients were evaluable for TMB.

†Statistical differences between subgroups were assessed with the χ2 test.

‡Stage at initial cervical cancer diagnosis was unknown for 8 patients.

§Patients might be initially diagnosed and staged at other hospitals before seeking treatment at the Asan Medical Center. Stage at tissue collection was unknown for two patients.

∥Among the “other” group for stage at tissue collection, all patients had recurrent disease with the exception of one patient with persistent disease.

¶Grade was unknown for 32 patients.

**HPV status was unknown for 159 patients.

2. Biomarker prevalence and correlation

The prevalence of biomarkers by disease characteristics and prior treatment is shown in Table 1. All 267 patients had samples evaluable for PD-L1 expression; 172 patients (64.4%) had PD-L1 CPS ≥1, the prevalence of which was higher in patients with SCC compared with AC/ASC (73.9% vs. 34.4%). There were 258 patients who had samples evaluable for TMB status; 84 patients (32.6%) had TMB ≥175 mutations/exome, the prevalence of which was higher in patients with metastatic disease compared with recurrent disease (52.9% vs. 28.8%) and in patients with SCC compared with AC/ASC (37.2% vs. 17.7%). PD-L1 CPS ≥1 and TMB ≥175 mutations/exome were not correlated (p=0.588).

3. OS

For OS from advanced cervical cancer diagnosis, 130 of 172 patients (75.6%) in the PD-L1 CPS ≥1 subgroup and 71 of 95 patients (74.7%) in the PD-L1 CPS <1 subgroup had died; the median (95% confidence interval [CI]) OS was 19.0 months (16.0–25.0) versus 22.0 months (16.0–28.0), respectively (adjusted hazard ratio [HR]=1.14; 95% CI=0.84–1.53) (Fig. 1A). Results for OS from first-line therapy initiation (Fig. S2A) and from second-line therapy initiation (Fig. S2B) were similar.

Fig. 1. OS from advanced cervical cancer diagnosis by (A) PD-L1 CPS and (B) TMB status.

CPS, combined positive score; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TMB, tumor mutational burden.

*HR was adjusted for age at advanced cervical cancer diagnosis, prior (neo)adjuvant treatments (yes/no), history of chronic kidney disease, birth parity, and body mass index.

For OS from advanced cervical cancer diagnosis, 67 of 84 patients (79.8%) in the TMB ≥175 mutations/exome subgroup and 127 of 174 patients (73.0%) in the TMB <175 mutations/exome subgroup had died; the median (95% CI) OS was 20.0 months (14.0–24.0) versus 24.0 months (16.0–27.0), respectively (adjusted HR=1.29; 95% CI=0.95–1.75) (Fig. 1B). Results for OS from first-line therapy initiation (Fig. S3A) and from second-line therapy initiation (Fig. S3B) were similar.

4. rwPFS

For PFS by first-line therapy initiation, 138 of 155 patients (89.0%) in the PD-L1 CPS ≥1 subgroup and 80 of 89 patients (89.9%) in the PD-L1 CPS <1 subgroup had experienced disease progression or died; the median (95% CI) rwPFS from first-line therapy initiation was 9.0 months (7.0–10.0) versus 9.1 months (7.1–12.0), respectively (adjusted HR=1.21; 95% CI=0.90–1.61) (Table 2). The median (95% CI) rwPFS from second-line therapy initiation was 3.1 months (3.1–5.0) in the PD-L1 CPS ≥1 subgroup versus 4.0 months (3.1–6.1) in the PD-L1 CPS <1 subgroup (adjusted HR=1.10; 95% CI=0.78–1.55) (Table 2).

Table 2. rwPFS by PD-L1 expression and TMB status from first-line therapy initiation and second-line therapy initiation.

| Variables | Biomarker status | Events (n/N) | rwPFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI), mo | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | ||||

| PD-L1 expression | |||||

| From first-line therapy initiation | CPS ≥1 | 138/155 | 9.0 (7.0–10.0) | 1.21 (0.90–1.61)* | |

| CPS <1 | 80/89 | 9.1 (7.1–12.0) | |||

| From second-line therapy initiation | CPS ≥1 | 101/105 | 3.1 (3.1–5.0) | 1.10 (0.78–1.55)† | |

| CPS <1 | 59/64 | 4.0 (3.1–6.1) | |||

| TMB status | |||||

| From first-line therapy initiation | TMB ≥175 mutations/exome | 71/76 | 7.1 (5.1–10.0) | 1.38 (1.03–1.85)* | |

| TMB <175 mutations/exome | 139/159 | 9.1 (8.0–11.0) | |||

| From second-line therapy initiation | TMB ≥175 mutations/exome | 50/52 | 3.1 (3.0–5.0) | 1.37 (0.96–1.94)† | |

| TMB <175 mutations/exome | 103/110 | 4.0 (3.1–5.1) | |||

CI, confidence interval; CPS, combined positive score; HR, hazard ratio; PD-L1, programmed death ligand; rwPFS, real-world progression-free survival; TMB, tumor mutational burden.

*HR was adjusted for age at persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer diagnosis, body mass index, history of kidney disease, receiving bevacizumab in first-line treatment, and prior radiotherapy (yes/no).

†HR was adjusted for age at advanced cervical cancer diagnosis, grade of cervical cancer at initial cervical cancer diagnosis, and smoking.

For PFS by first-line therapy initiation, 71 of 76 patients (93.4%) in the TMB ≥175 mutations/exome subgroup and 139 of 159 patients (87.4%) in the TMB <175 mutations/exome subgroup had experienced disease progression or died; the median (95% CI) rwPFS was 7.1 months (5.1–10.0) versus 9.1 months (8.0–11.0), respectively (adjusted HR=1.38; 95% CI=1.03–1.85) (Table 2). The median (95% CI) rwPFS from second-line therapy initiation was 3.1 months (3.0–5.0) in the TMB ≥175 mutations/exome subgroup versus 4.0 months (3.1–5.1) in the TMB <175 mutations/exome subgroup (adjusted HR=1.37; 95% CI=0.96–1.94) (Table 2).

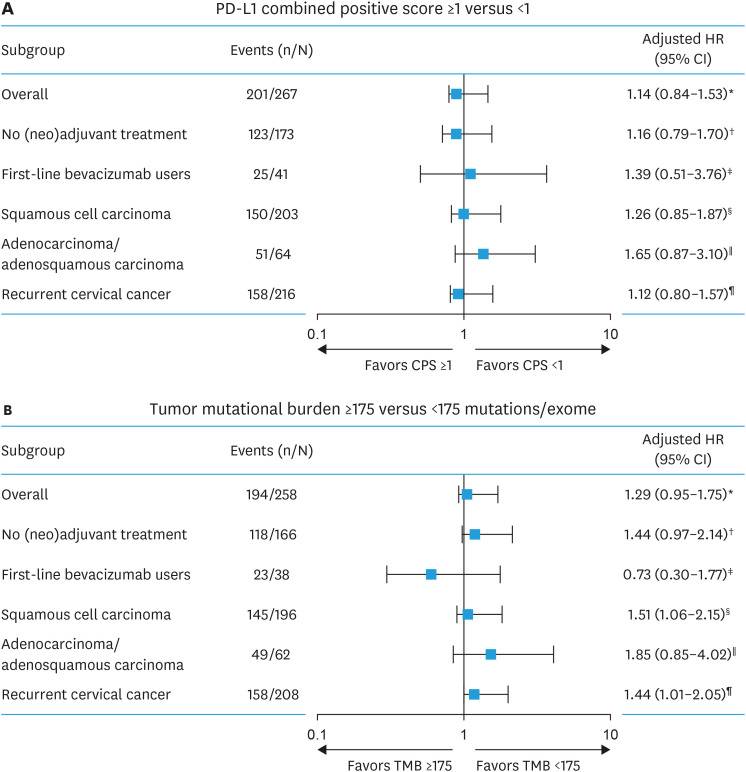

5. OS and biomarker association by clinical characteristics

Consistent with the overall population, PD-L1 status was not associated with OS when evaluated by subgroups based on clinical characteristics (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the trend for shorter median OS among patients with TMB ≥175 versus <175 mutations/exome was observed across subgroups based on clinical characteristics, except for patients who received bevacizumab in the first-line treatment setting (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Overall survival from advanced cervical cancer diagnosis by (A) PD-L1 CPS and (B) TMB status in patient subgroups.

CPS, combined positive score; HR, hazard ratio; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TMB, tumor mutational burden.

*HR was adjusted for age at advanced cervical cancer diagnosis, prior (neo)adjuvant treatments (yes/no), history of chronic kidney disease, birth parity, and body mass index.

†HR was adjusted for age at advanced cervical cancer diagnosis, history of chronic kidney disease, and tumor size for no (neo)adjuvant therapy.

‡HR was adjusted for age at advanced cervical diagnosis and body mass index.

§HR was adjusted for age at advanced cervical diagnosis, birth parity, body mass index, history of chronic kidney disease, tumor size, and prior (neo)adjuvant therapy.

∥HR was adjusted for age at advanced cervical diagnosis, stage at tissue collection, smoking, and prior radiation.

¶HR was adjusted for age at advanced cervical cancer diagnosis, stage at tissue collection, and prior (neo)adjuvant therapy.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis of patients with non-immunotherapy standard-of-care–treated advanced cervical cancer, 64.4% of patients had tumors with PD-L1 CPS ≥1 and 32.6% of patients had tumors with TMB ≥175 mutations/exome. A higher prevalence of PD-L1 CPS ≥1 and TMB ≥175 mutations/exome (concordant with ≥10 mut/Mb) was observed in patients with SCC than in patients with AC/ASC. Additionally, PD-L1 CPS ≥1 compared with PD-L1 CPS <1 was not associated with OS in the overall population or in subgroups based on clinical characteristics. Furthermore, TMB ≥175 mutations/exome showed a trend toward shorter OS compared with TMB <175 mutations/exome in the overall population or in subgroups based on clinical characteristics, except for patients who received first-line bevacizumab. Similarly, starting from the point of first-line therapy initiation, PD-L1 expression was not associated with rwPFS or OS, and TMB ≥175 mutations/exome showed shorter OS compared to TMB <175 mutations/exome. Because of the small sample size, trends were not clear for outcomes from second-line therapy initiation.

The prevalence of PD-L1-positive cervical cancer has been reported to range from 22% to >87% for SCC [19,20,21] and from 14% to 29% for AC/ASC [19,22]. The prevalence observed in this study is within the range reported, although different PD-L1 antibody clones and/or cutoffs for PD-L1 positivity were used. Also consistent is our finding that more patients with cervical cancer have SCC versus AC/ASC histology and that SCC is more frequently PD-L1-positive [19,23,24]. Previous reports have shown the prevalence of TMB-high advanced cervical cancer is 15%–16% [17,25].

A recent pan-tumor investigation of the prognostic value of TMB using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) showed that TMB-high was a statistically significant prognostic indicator of decreased mortality compared with non-TMB-high in patients with cervical SCC and endocervical adenocarcinoma [26]. Contrary to our findings, a computational study using data of patients from TCGA showed TMB-high (≥ median) cervical SCC may be associated with a higher OS [15]. However, observations from a recent single-institution study of patients with cervical cancer in Japan showed that those patients with TMB-H tumors (≥9.5 mut/Mb) had a worse 5-year OS rate than those with non–TMB-high tumors (<9.5 mut/Mb) after definitive radiotherapy (61.1% vs. 82.2%) [27]. Various theories and interpretations may account for the conflicting findings between studies, including differences in treatment regimen/modality, methods used for determining TMB, and thresholds for categorizing TMB as high or low. Additionally, a recent evaluation of TCGA datasets suggested that survival data from the database may not be adequately treated and processed, leading to misinterpretation and impacting survival analyses using this data source [28]. In addition, variations in treatment approaches, such as the use of different chemotherapy agents or targeted therapies, can impact treatment responses and, subsequently, survival outcomes. Studies conducted in neuroblastoma and lung cancer have further indicated that TMB-high tumors, characterized by elevated mutations and complex genetic profiles, may be more aggressive and resistant to current non-immunotherapies, leading to shorter OS [29,30]. The findings in patients with cervical cancer from our study and Ota et al. [27] further corroborate this theory and highlight a consistent trend of short OS in these patients with TMB-high tumors. The underlying biology of TMB-high tumors may contribute to their aggressiveness and resistance to conventional therapies [31]. TMB-high tumors are characterized by increased mutations and complex genetic profiles, which can lead to enhanced tumor heterogeneity and the emergence of treatment-resistant clones [32,33]. This heightened genomic instability may render TMB-high tumors less responsive to traditional non-immunotherapeutic approaches [34], potentially resulting in shorter OS. These mechanistic insights underscore the importance of considering both treatment-related factors and tumor biology when interpreting study findings and designing therapeutic strategies for patients with advanced cervical cancer.

This study was performed using extensive samples, and the results are based on a reliable analysis from a single institution that implements consistent standardized treatment. Detailed patient-level clinical data were collected, and the distribution of the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were consistent with published country-specific characteristics of patients with cervical cancer; thus, eliminating potential selection bias. However, this retrospective study has several limitations. First, the sampling process did not generate a random sample of all patients with advanced cervical cancer treated at the Asan Medical Center, thereby limiting generalizability of findings. Second, because patients were from large tertiary teaching hospitals, it is conceivable that tumor samples may represent more severe cases of advanced cervical cancer compared with the broader patient population. Third, requiring 11 slides may select for a population with only available and sufficient tissue samples, possibly characterizing an earlier stage of disease during which resection and transplantation were more likely. Furthermore, if the biomarker status changed over the course of disease due to internal and/or external factors, the biomarker data generated from this study may not be reflective of the later disease course; this limitation may reduce the generalizability of the data. Fourth, the variability in follow-up time relative to treatment may impact the evaluation of OS. Fifth, the heterogeneity of the study cohort, comprising 83.9% and 75.4% of patients who received prior first-line and second-line treatment, respectively, may impact the evaluation of the prognostic role of PD-L1 expression and TMB status. Lastly, the rwPFS outcome should be interpreted with caution given that the data were collected in routine clinical practice and analyzed retrospectively outside of a formal clinical trial.

The findings of this analysis suggest PD-L1 expression has no prognostic value for OS and TMB ≥175 mutations/exome showed a trend toward shorter OS in patients with advanced cervical cancer treated with non-immunotherapy standard of care therapy. Given the increasing use of immunotherapy, including PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, for the treatment of patients with advanced cervical cancer, prevalence data can help better understand the patient population potentially benefiting from this type of treatment. The current study exploring the association between TMB and clinical outcomes with non-immunotherapy are necessary to demonstrate prognostic value of PD-L1 expression and TMB, to help identify potential unmet medical needs based on a patient’s biomarker status, and to inform the management and treatment of patients with advanced cervical cancer.

In conclusion, this retrospective study observed a higher prevalence of PD-L1 expression (CPS ≥1) and TMB ≥175 mutations/exome (concordant with ≥10 mut/Mb) status in SCC versus AC/ASC advanced cervical cancer. PD-L1 CPS ≥1 was not associated with OS, whereas TMB ≥175 mutations/exome trended toward a shorter OS compared with TMB <175 mutations/exome. Future prospective studies are warranted to confirm these findings and elucidate the predictive and prognostic value of potential immune biomarkers in cervical cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the patients and their families and all investigators and site personnel. Li Ma, Xingshu Zhu, and Fansen Kong (Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA) contributed to data analysis. Medical writing and/or editorial assistance was provided by Holly C. Cappelli, PhD, CMPP, of ApotheCom (Yardley, PA, USA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

Footnotes

Funding: Funding for this study was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. The funder participated in the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. All authors had full access to the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Presentation: Presented in part as a poster at European Society of Medical Oncology 2021 Virtual Meeting (September 16-21, 2021).

Conflict of Interest: J-YP and M-HB have nothing to disclose. LC, CS, and PJ are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, and own stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. CT and XYJ are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. RC is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, owns stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, and has two pending patents (Angiogenesis and mMDSC gene expression-based biomarker of tumor response to PD-1 antagonists; patent WO 2020/167619). SI is an employee of MSD Korea (employment [JCAP asso RDMA]), registered pharmacist (Korea), and stockholder of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

Data Availability Statement: Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (MSD), is committed to providing qualified scientific researchers access to anonymized data and clinical study reports from the company’s clinical trials for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. MSD is also obligated to protect the rights and privacy of trial participants and, as such, has a procedure in place for evaluating and fulfilling requests for sharing company clinical trial data with qualified external scientific researchers. The MSD data sharing website (available at: http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php) outlines the process and requirements for submitting a data request. Applications will be promptly assessed for completeness and policy compliance. Feasible requests will be reviewed by a committee of MSD subject matter experts to assess the scientific validity of the request and the qualifications of the requestors. In line with data privacy legislation, submitters of approved requests must enter into a standard data-sharing agreement with MSD before data access is granted. Data will be made available for request after product approval in the US and EU or after product development is discontinued. There are circumstances that may prevent MSD from sharing requested data, including country or region-specific regulations. If the request is declined, it will be communicated to the investigator. Access to genetic or exploratory biomarker data requires a detailed, hypothesis-driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and MSD subject matter experts; after approval of the statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement, MSD will either perform the proposed analyses and share the results with the requestor or will construct biomarker covariates and add them to a file with clinical data that is uploaded to an analysis portal so that the requestor can perform the proposed analyses.

- Conceptualization: B.M.H., S.C., I.S.Y., J.P., P.J.Y.

- Data curation: B.M.H., C.L., S.C., I.S.Y., J.P., P.J.Y.

- Formal analysis: C.L., C.R., J.X.Y., J.P., P.J.Y.

- Investigation: B.M.H., J.P.

- Validation: C.L., T.C., C.R., J.X.Y., S.C., J.P., P.J.Y.

- Writing - original draft: B.M.H., C.L., I.S.Y., J.P., P.J.Y.

- Writing - review & editing: B.M.H., C.L., T.C., C.R., J.X.Y., S.C., J.P., P.J.Y.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Patient eligibility and data profile.

OS from (A) first-line therapy initiation and (B) second-line therapy initiation by PD-L1 CPS.

OS from (A) first-line therapy initiation and (B) second-line therapy initiation by TMB status.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marth C, Landoni F, Mahner S, McCormack M, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N, et al. Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv72–iv83. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, Caceres MV, Hasegawa K, Shapira-Frommer R, et al. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plummer M, de Martel C, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Franceschi S. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e609–e616. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mezache L, Paniccia B, Nyinawabera A, Nuovo GJ. Enhanced expression of PD L1 in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancers. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1594–1602. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang W, Song Y, Lu YL, Sun JZ, Wang HW. Increased expression of programmed death (PD)-1 and its ligand PD-L1 correlates with impaired cell-mediated immunity in high-risk human papillomavirus-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Immunology. 2013;139:513–522. doi: 10.1111/imm.12101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinh-Hung V, Bourgain C, Vlastos G, Cserni G, De Ridder M, Storme G, et al. Prognostic value of histopathology and trends in cervical cancer: a SEER population study. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung HC, Ros W, Delord JP, Perets R, Italiano A, Shapira-Frommer R, et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in previously treated advanced cervical cancer: Results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1470–1478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enwere EK, Kornaga EN, Dean M, Koulis TA, Phan T, Kalantarian M, et al. Expression of PD-L1 and presence of CD8-positive T cells in pre-treatment specimens of locally advanced cervical cancer. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:577–586. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin Y, Ekmekcioglu S, Forget MA, Szekvolgyi L, Hwu P, Grimm EA, et al. Cervical cancer neoantigen landscape and immune activity is associated with human papillomavirus master regulators. Front Immunol. 2017;8:689. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:202–206. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao J, Yang X, Chen S, Wang J, Fan X, Fu S, et al. The predictive efficacy of tumor mutation burden in immunotherapy across multiple cancer types: a meta-analysis and bioinformatics analysis. Transl Oncol. 2022;20:101375. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cristescu R, Aurora-Garg D, Albright A, Xu L, Liu XQ, Loboda A, et al. Tumor mutational burden predicts the efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy: a pan-tumor retrospective analysis of participants with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:e003091. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen F, Ruan S, Huang W, Chen X, Wang Y, Gu S, et al. Prognostic value of tumor mutational burden related to immune infiltration in cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:755657. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.755657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aurora-Garg D, Albright A, Qiu P, Li Y, Liu X, Fabrizio D, et al. Large-scale evaluation of concordance of genomic scores in whole exome sequencing and foundation medicine comprehensive genomic platform across cancer types. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:318. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, Shah M, Shapira-Frommer R, Nakagawa K, et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M, Albright A, Murphy E, Yearley J, et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science. 2018;362:eaar3593. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heeren AM, Punt S, Bleeker MC, Gaarenstroom KN, van der Velden J, Kenter GG, et al. Prognostic effect of different PD-L1 expression patterns in squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:753–763. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koncar RF, Feldman R, Bahassi EM, Hashemi Sadraei N. Comparative molecular profiling of HPV-induced squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Med. 2017;6:1673–1685. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang Y, Yu M, Zhou C, Zhu X. Variation of PD-L1 expression in locally advanced cervical cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Diagn Pathol. 2020;15:67. doi: 10.1186/s13000-020-00977-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saglam O, Conejo-Garcia J. PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced cervical cancer. Integr Cancer Sci Ther. 2018;5:10.15761/ICST.1000272. doi: 10.15761/ICST.1000272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omenai SA, Ajani MA, Okolo CA. Programme death ligand 1 expressions as a surrogate for determining immunotherapy in cervical carcinoma patients. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0263615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy OL, Shintaku PI, Moatamed NA. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) is expressed in a significant number of the uterine cervical carcinomas. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12:45. doi: 10.1186/s13000-017-0631-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao C, Li G, Huang L, Pruitt S, Castellanos E, Frampton G, et al. Prevalence of high tumor mutational burden and association with survival in patients with less common solid tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2025109. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu HX, Wang ZX, Zhao Q, Chen DL, He MM, Yang LP, et al. Tumor mutational and indel burden: a systematic pan-cancer evaluation as prognostic biomarkers. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:640. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.10.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ota N, Yoshimoto Y, Darwis ND, Sato H, Ando K, Oike T, et al. High tumor mutational burden predicts worse prognosis for cervical cancer treated with radiotherapy. Jpn J Radiol. 2022;40:534–541. doi: 10.1007/s11604-021-01230-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Idogawa M, Koizumi M, Hirano T, Tange S, Nakase H, Tokino T. Dead or alive? Pitfall of survival analysis with TCGA datasets. Cancer Biol Ther. 2021;22:527–528. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2021.1979845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang WL, Wolfson RL, Niemierko A, Marcus KJ, DuBois SG, Haas-Kogan D. Clinical impact of tumor mutational burden in neuroblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:695–699. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Offin M, Rizvi H, Tenet M, Ni A, Sanchez-Vega F, Li BT, et al. Tumor mutation burden and efficacy of EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:1063–1069. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fusco MJ, West HJ, Walko CM. Tumor mutation burden and cancer treatment. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:316. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang A, Miao K, Sun H, Deng CX. Tumor heterogeneity reshapes the tumor microenvironment to influence drug resistance. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:3019–3033. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.72534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie N, Shen G, Gao W, Huang Z, Huang C, Fu L. Neoantigens: promising targets for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:9. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01270-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang H, Yu M, Zhong S, You Y, Feng F. Neoantigens and the tumor microenvironment play important roles in the prognosis of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2022;15:18. doi: 10.1186/s13048-022-00955-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Patient eligibility and data profile.

OS from (A) first-line therapy initiation and (B) second-line therapy initiation by PD-L1 CPS.

OS from (A) first-line therapy initiation and (B) second-line therapy initiation by TMB status.