Abstract

Background:

Decision-making for adult tracheostomy and prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV) is emotionally complex. Expectations of surrogate decision-makers and physicians rarely align. Little is known about what surrogates need to make goal-concordant decisions. Currently, little is known about the decisional needs of surrogates and providers, impeding efforts to improve the decision-making process.

Methods:

Using a thematic analysis approach, we performed a qualitative study with semi-structured interviews with surrogates of adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation (MV) being considered for tracheostomy and physicians routinely caring for patients receiving MV. Recruitment was stopped when thematic saturation was reached. We describe the decision-making process, identify core decisional needs, and mapped the process and needs possible elements of a future shared decision-making tool.

Results:

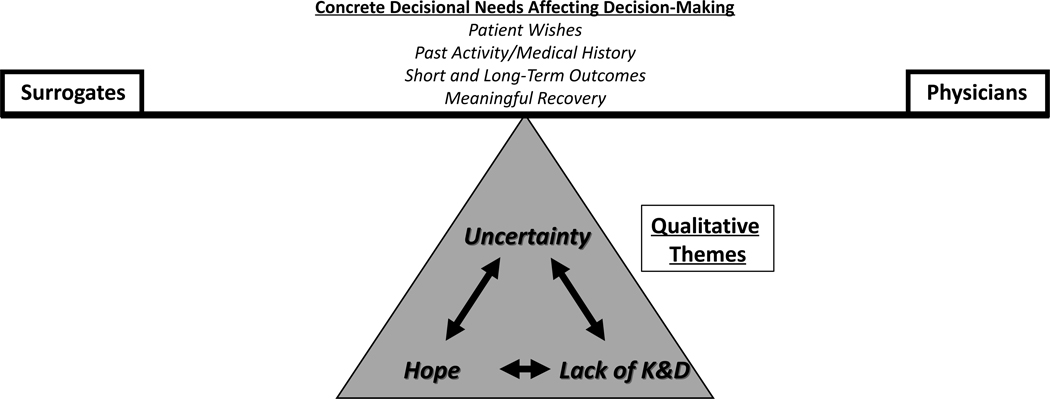

43 participants (23 surrogates and 20 physicians) completed interviews. Hope, Lack of Knowledge & Data, and Uncertainty emerged as the three main themes that described the decision-making process, and which were interconnected with one another and, at times, opposed each other. Core decisional needs included information about Patient Wishes, Past Activity/Medical History, Short and Long-Term Outcomes, and Meaningful Recovery. The themes were the lens through which the decisional needs were weighed. Decision-making existed as a balance between surrogate emotions and understanding and physician recommendations.

Conclusions:

Tracheostomy and prolonged MV decision-making is complex. Hope and Uncertainty were conceptual themes that often battled with one another. Lack of Knowledge & Data plagued both surrogates and physicians. Multiple tangible factors were identified that affected surrogate decision-making and physician recommendations.

Implications:

Understanding this complex decision-making process has the potential to improve the information provided to surrogates and, potentially, increase the goal concordant care and alignment of surrogate and physician expectations.

Introduction

In the United States, nearly 100,000 adults undergo tracheostomy annually, mostly to enable prolonged respiratory support.[1, 2] While a tracheostomy can facilitate life-prolonging interventions like prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV), it is also associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The majority of patients with a tracheostomy require prolonged hospitalization and intensive rehabilitation.[2, 3] Older adults with a tracheostomy often have a median survival of three to six months with high rates of readmission, frequent complications, and prolonged hospital stays.[3–5] The struggle between the potential for longer survival versus the complications associated with prolonged life support can make tracheostomy-related decisions emotionally complex for surrogate decision-makers.

Shared decision-making (SDM) is the collaborative process of patients, surrogates, and providers reaching an informed collective agreement on the treatment most consistent with a patient’s values and is recommended as a core part of care for critically ill patients.[6–10] SDM for tracheostomy and PMV is not a new concept. Several studies have investigated decisional needs among parents of pediatric patients being considered for a tracheostomy.[11–15] These studies describe multiple factors that impacted decision-making for children including the child’s well-being, uncertainty, and provider engagement in the process. Across most studies, a child’s survival was the most important consideration for parents. However, tracheostomy and PMV are fundamentally different decisions for adults. The diseases processes (chronic progressive respiratory failure for pediatric patients vs acute respiratory failure, stroke, etc. for adults) are vastly different and most adults experience extremely poor survival compared to pediatric patients with a tracheostomy.[2, 3, 5, 16, 17] Home ventilation is also far less feasible for adults making tracheostomy decisions for adults ones that often revolve around long-term hospitalization.[2, 3, 5] These differences have significance for decision-making and SDM. In pediatric cases, parents often can anticipate the eventual need of a tracheostomy due to the chronic progressive nature of most indications. Due to the gradual development of chronic respiratory failure, high rates of survival with PMV among pediatric patients, and the emotional calculus of a parent making decisions a young child, decision-making in pediatric patients is often one of timing rather than considerations of palliative options. However, for adult patients the decisions are more imminent and truly represent a branchpoint in care – tracheostomy and PMV versus palliative options. While extensive work has been done to describe processes for pediatric patients, several gaps remain in describing the decision-making process and needs for adult patients. Greater understanding of the process for adults and the needs of their surrogate decision-makers could aid providers in navigating a complex decision choice.

Prior studies have attempted to describe patient and surrogate needs during the decision-making process for adults but few have been able to identify core decisional needs or account for the complex interaction between surrogates and providers.[18, 19] Xu et al analyzed recordings from family meetings and found that almost half did not discuss patient’s previous wishes or long-term implications of a tracheostomy.[18] Cox et al found that surrogate expectations for recovery rarely aligned with those of providers.[19] Rubin et al found that some adults viewed being attached to machines as being “worse than death”.[20] Several studies have also shown that patients and families feel uninformed and that their values were not considered.[21–24] Few studies commented on the provider role in the decision-making process. Collectively, these studies highlight gaps in identifying decisional needs as well as understanding the decision-making process. These gaps may contribute to care that is not goal-concordant that has been suggested by prior studies.[2, 5, 25] Understanding decisional needs and the interactive process of decision-making between surrogates and providers, is a key step in ensuring that tracheostomy decisions align with patient/surrogate value structure.[26–31]

In order to address these gaps and inform SDM efforts, we conducted a qualitative study of surrogates and providers with two explicit goals: (1) identify surrogate and provider decisional needs while describing the interactive process of decision-making and (2) identify potential features of future SDM tools that can contribute to more goal-concordant care and less decisional conflict.

Methods

Please see the Online Supplemental Methods for full details.

Study Design:

We conducted a qualitative study of surrogate decision-makers of patients being considered for tracheostomy and critical care physicians routinely involved in tracheostomy decisions from 2018–2022. Standards from the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research were followed (See eTable 1).[32] We used a thematic analysis approach within a larger Grounded Theory framework to 1) describe the decision-making process, 2) identify key decisional needs, and 3) explore elements for potential SDM tools that could be designed based on our findings. [33, 34] Decisional needs were pieces of information that aided or hindered the decision-making process. Potential elements of a SDM tool were things that could improve the process, improve communication, or improve the presentation of information about decisional needs.

Participants:

Surrogate decision-makers were recruited from two hospitals and critical care physicians were recruited from multiple academic, public, and private physician practices. Surrogates were eligible if they represented a patient being considered for tracheostomy (see Online Supplement for details), were ≥18 years, and were English-speaking. Up to three surrogates per patient were allowed to enroll.[35] Critical care physicians who routinely care for patients receiving MV and engage with surrogates about tracheostomy related decisions were recruited through invitational emails.

A convenience sampling approach was initially used, followed by theoretical sampling to increase the number of surrogates who decided not to pursue a tracheostomy and physicians in private practice. Participant recruitment was discontinued once thematic saturation, the point at which no new themes emerge with additional interviews, was reached.[36, 37] Multiple interruptions to recruitment occurred due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Collection and Analysis:

Separate surrogate and physician interview guides were developed, and semi-structured interviews were conducted in person or virtually by study members trained in qualitative interviews (Online Supplement). Interview guides focused on general approaches to decision-making, decisional needs, and features that might make a SDM tool more usable and acceptable. Interviews were digitally recorded Interview transcripts were coded and categorized using a constant comparative method and inductive approach.[38] The first five transcripts in each group were independently double-coded to develop separate codebooks for surrogates and physicians. Thereafter, every fifth transcript was double-coded to ensure calibration. An open team-based coding process allowed conceptual themes to emerge from the data.

Atlas.ti v9 (Berlin, Germany) was used for data management. All participants provided informed consent for the study. The study was approved by the National Jewish Health Institutional Review Board (HS-3136) and the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (20–3102).

Results

Participants

Forty-three participants (23 surrogates and 20 physicians) participated in interviews (Table 1). Surrogates had a mean age of 48.2 years (SD=15.4) and were predominantly either the spouse/partner (26.1%) or child (34.8%) of the patient. Physicians had a mean age of 45.1 years (SD=7.5) with a broad range of years in practice.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Surrogate (n=23) | Physician (n=20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 48.2 (15.4)A | 45.1 (7.5) |

|

| ||

| Female, n (%) | 16 (76.2)A | 4 (20) |

|

| ||

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 9 (39.1) | 15 (75.0) |

| Black | 9 (39.1) | 2 (10.0) |

| American Indian/Native American | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0) |

| Other/Unknown | 3 (13.1) | 3 (15.0) |

|

| ||

| Hispanic, n (%) | 4 (17.4) | 2 (10.0) |

|

| ||

| Relationship to Patient (%) | NA | |

| Spouse/Significant Other | 6 (26.1) | |

| Child | 8 (34.8) | |

| Sibling | 3 (13.0) | |

| Other/Unknown | 6 (23.1) | |

|

| ||

| Where do you practice? (%) | NA | |

| Academic Setting | 8 (40.0) | |

| Private Practice Model | 4 (20.0) | |

| Hybrid Model | 8 (40.0) | |

|

| ||

| How long have you practiced critical care medicine? (%) | NA | |

| <5 years | 4 (20.0) | |

| 5–9 years | 5 (25.0) | |

| 10–14 years | 7 (35.0) | |

| >15 years | 4 (20.0) | |

Abbreviations: SD – standard deviation. n – number.

2 surrogates did not provide demographic information. No missing data was imputed.

Decision-Making Process and Decisional Needs

Based on the interviews, three conceptual themes emerged that described the decision-making process for surrogates and providers: Hope, Uncertainty, and Lack of Knowledge & Data. The themes were highly interactive (e.g., the Lack of Knowledge & Data contributed to Uncertainty for nearly all participants). Additionally, four concrete decisional needs that contributed to surrogate decision-making and physician recommendations about tracheostomy were identified: Patient Wishes, Past Activity/Medical History, Short and Long-Term Recovery, and Meaningful Recovery. Decision-making existed as a complex bidirectional process between surrogates and physicians. Surrogates did not view the provider’s role as simply offering information and the final decisions resting solely with the surrogate but rather as a key part of the decision-making team. (Figure 1).

Hope:

Hope was one of the most common concepts discussed by all participants but affected surrogates and providers differently (Table 2, eTable 2) Hope was the lens through which many surrogates viewed past medical issues and influenced considerations about short- and long-term outcomes and meaningful recovery. When considering different possible outcomes, Hope sometimes superseded factual understanding of medical issues or even the potential for recovery. Some surrogates indicated that despite knowing the high percentages of poor outcomes, they still held onto Hope for meaningful recovery. Some surrogates connected the feeling of Hope to their faith, “We just believe that prayer and everybody’s faith and hope is there. And it’s just a different way of looking at life I guess than a lot of the medical field looks at it, and we never knew that.” (Surrogate ID1) Surrogates were split on whether physicians fully acknowledged how their Hope was a key part of their decision-making.

Table 2.

Hope

| Oh, I think he’s strong. Stronger than everybody thought he could be with the blessings he’s had. I have no idea how long he’ll live. I’m just going to enjoy every day that we have, and his family is the same and his friends. I read and I see 70 percent of people don’t make it to three years or five years or whatever that percentage is, and I see it and I can’t help but hope that he’ll be the one that’ll be on the other percentage that’ll live longer, and I don’t know if that’ll happen or not. (Surrogate ID1) |

| Well hopefully she gets out of the hospital and gets off the breathing machine. If she has to have a trach, she has to have one. But she needs to get back home, in her own bed, and back to her old life. And back to the regular things she does. Even though she can’t eat my good cooking. (Surrogate ID2) |

| I wish it was all better…had to do what I need to do if she’s gonna stay alive. I can’t just say take it off. I was just explaining to you earlier. I’m not gonna make a decision that will end her life. I can’t do that. (Surrogate ID6) |

| We’re saying it’s not necessarily benefiting the patient. Yeah, and, typically, families will tell you that they usually get it, and they usually eventually come to a decision that they’ll say, “We don’t want the tracheostomy,” and so on. Sometimes families, though, the values are such that they feel a heartbeat is life. As long as there’s a heartbeat, there’s hope, and they want it done. They will express that the patient’s was such that, when they were lucid, they said that that was their values. They would rather be alive in a vegetative state than not, and so we’ll go ahead and do it. (Physician ID36) |

| None of us can predict the future. Everyone should have hope. I don’t count that as a negative. I just try to—what you don’t want, is you don’t want the family, the surrogate or the patient afterwards saying, “I never wish I’d have to go through that again.” It’s really hard to portray it accurately enough and for the family to make a decision based on that. Right? They’re making decisions based on wanting their family member to live. It’s really, really hard. That’s what I’m trying to do, but I don’t think any of us do it that well. (Physician ID40) |

| In our patient population, which may or may not be similar to what you guys deal with is pretty much all the patients go to the mat that they want everything done, every intervention. They’re a fighter. There’s miracles. We’re praying to God. Most of our families don’t ever wanna give up anything, and they’re demanding more and more and more. Even when the patient’s skin in falling off, and they just, “Keep going, keep going.” (Physician ID42) |

Physicians spoke about Hope from a different perspective. Many physicians described struggling with the cognitive disconnect between surrogates’ Hope for meaningful recovery and the clinical probability for recovery for patients with severe comorbid disease like cancer or acute illness like cardiac arrest: “I think family members who end up having tracheostomy put in patients who probably have no hope of getting better are, in a sense, kicking the can down the road, meaning they’re not—they’re hoping God intervenes and makes ‘em better.” (Physician ID37). When physicians felt that there was little Hope for meaningful recovery (e.g., older patients, patients with severe chronic comorbidities, or those with poor baseline functional status), they would often steer conversations away from tracheostomy, “I think someone who doesn’t have a bridge therapy to a good quality of life, so say someone who has a cardiac arrest and it has pretty obvious anoxic brain injury and there’s not likelihood for meaningful recovery, I try to steer the family away from a tracheostomy” (Physician ID39). Physicians struggled when surrogates held onto strong Hope in the face of evidence of poor likelihood of recovery.

Lack of Knowledge & Data:

The Lack of Knowledge & Data had a large impact on the decision-making process for both surrogates and providers (Table 3, eTable 3) and drove strong feelings of Uncertainty. Surrogates mentioned feeling uninformed about possible outcomes like ventilator liberation, regaining the ability to eat or talk, regaining functional status, returning home, and overall survival. Even after a family meetings, one surrogate was still unclear about what the “quality of life” would be after a tracheostomy or any potential alternatives even after the discussion with the medical team: “Can they have a quality of life? Can they do things? Or are they just bound to a bed and that machine? Is there a portable machine that helps them breathe or is it – I don’t know. What options would there be? (Surrogate ID3). Physicians echoed many of these sentiments both in describing their perception about how the Lack of Knowledge & Data affected surrogates and how the inability to accurately predict short- and long-term outcomes limited their confidence in recommendations. Physicians specifically used the term ‘Meaningful Recovery’ although this concept meant different things to different providers. The lack of outcomes data strongly contrasted with other areas of critical care where physicians felt that they are better able to guide patients and surrogates.

Table 3.

Lack of Knowledge & Data

| Maybe more details about the rehabs and absolutely about the rehabs, what he’d do there, what the possibility – we were wanting to ask about if he can’t walk, would he have to have a mobile chair, wheelchair or those little gadget chairs that move around, what can he do to still have a little bit of quality of life to get around. We wanted to ask if the dry weather was going to be better than humid weather, warm weather better than cold weather altitudes, but they – we never got a chance to sit down. And even when we were in the team meetings, we weren’t ever asked do you have any questions ever. (Surrogate ID1) |

| Interviewer: Sure. What kind of education would want in terms of the different things that people can do with a trach, a tracheostomy? Interviewee: Can they have a quality of life? Can they do things? Or are they just bound to a bed and that machine? Is there a portable machine that helps them breathe or is it – I don’t know. What options would there be? (Surrogate ID3) |

| Educational stuff. What you can expect. . . .Going forward with it. The amount of sicknesses. Even if you don’t go over every sickness that you can get because yeah, you can get everything from not having a trach too. But the chances of getting sick go up. The chances of having a respiratory infection go up. But really what you can expect is the biggest thing that I would really have wanted to know going forward with somebody with a trach. (Surrogate ID7) |

| But I think if the trach is seriously being considered, if there’s a good prediction tool that could really say, “There’s a better chance than not this is a permanent fixture to this person’s body, and it may mean they’re gonna be living in the nursing home forever,” that can be helpful. (Physician ID28) |

| I think that would be good information to tell patients, here’s where this patient fits in terms of expected outcomes and trying to come to that decision with the family. Is it really worth it for us to pursue the tracheostomy or not? I think if we had a good data that showed us this patient fits this phenotype and they have this percentage chance to come off the ventilator, I think that would be very beneficial. . . I try not to do that, but if I had objective data that I could plug the specific patient’s information into and say, “Hey, 50 percent of patients have this outcome,” then I think that—or to stay on the ventilator for this long when they have this particular course to this particular disease pathology. I think that’s good information for them to manage their expectations and say, “Hey, maybe this is worth it, maybe this isn’t,” so that just everyone’s more informed. (Physician ID39) |

Multiple surrogates indicated that the Lack of Knowledge about rehabilitation, long-term acute care facilities, and costs made tracheostomy decisions much more difficult and caused them to hesitate on final decisions, “I think that I’m still a little fuzzy about the long-term. Because they had said that he was going to go to a long-term rehab facility. His insurance doesn’t cover that.” (Surrogate ID18). Physicians recognized that the long-term implications of tracheostomy often revolved around rehabilitation options. However, not all physicians explored these areas with surrogates with some leaving those discussions to case managers or social workers. Other physicians also felt that they did not have enough information to guide these conversations further fueling decisional conflict on the part of surrogates.

Surrogates also expressed a Lack of Knowledge about a patient’s wishes, even those who had severe illness prior to coming to the hospital: “I think it’s difficult to make decisions for somebody. I know that I know her for a long time, but this is something we never actually talked about” (Surrogate ID20). Providers similarly expressed difficulty in guiding surrogates around goal-concordant care when previous wishes were not known.

Discussions around alternatives to tracheostomy appeared to be one area in which surrogates and providers differed in their view of Lack of Knowledge. Most surrogates indicated that they did not know of any alternatives to tracheostomy even after meeting with the medical team. Some surrogates specifically stated that alternatives were never explored. In contrast, physicians felt that understanding alternatives was important and most stated that they always explored other options, “But I think they also need to know what the alternative is. I think they a lot of times make a decision to proceed with tracheostomy based on fear of the alternative, as opposed to wanting the tracheostomy.” (Physician ID28). This may represent a situation in which one party believes they are saying something, but the other party is not digesting it resulting in a Lack of Knowledge on the part of surrogates.

Another complex manifestation of Lack of Knowledge and Data and disconnect between physicians and surrogates was perceptions of past medical and acute medical issues. Some surrogates felt ill informed about the medical issues that were driving a need for tracheostomy, “He may have had shortness of breath and maybe passed out and had been unconscious. . . You know what, I think they did say he had a cardiac arrest” (Surrogate ID23). However, other surrogates felt confident in their knowledge even when it stood in contrast to medical facts. For example, one surrogate did not feel her loved one had any major medical issues that would affect his chances of recovery despite the fact that the patient had been dependent on supplemental oxygen due to progressive interstitial lung disease prior to the acute illness. As providers often tried to anchor discussions about the potential for recovery in past and acute medical issues, they struggled with what they perceived to be surrogates’ Lack of Knowledge around patients’ medical issues.

Uncertainty:

Uncertainty manifested as an intangible feeling about the entire decision-making process described by both surrogates and physicians (Table 4, eTable 4). Uncertainty was intricately linked to and interactive with Hope and Lack of Knowledge & Data. For many surrogates, decision-making was described as a battle between feelings of Hope and feelings of Uncertainty. Moreover, while Lack of Knowledge & Data dealt with concrete information and outcomes, it fueled the general sense of Uncertainty that surrogates and physicians described as contributing to decisional conflict. Patient wishes were reported to be important to both surrogates and physicians but views on these wishes were often influenced by Uncertainty even for patients with severe comorbid disease, “Because of the fact that he didn’t have any advance directive, we were winging it” (Surrogate ID7). Surrogates with a clearer view of a patient’s past wishes reported being less burdened during the decision-making process. Physicians also expressed their own Uncertainty about what might happen after a tracheostomy when discussing matters with surrogates. Physicians’ Uncertainty often revolved around more general concepts about the potential for recovery, the temporary or permanent nature of the tracheostomy, etc., “it’s [recovery] uncertain. Right? So, I can’t actually tell ‘em, but I can say . . . I say, “I can’t guarantee anything in medicine with the exception of I can guarantee we’re honest. I’ll tell you if they got worse or better. . . I’m not gonna get too high or too low.” (Physician ID33). One of the most common ways in which Uncertainty manifested for physicians was when they felt that patients had a poor chance of meaningful recovery but because of Uncertainty about outcomes, patient wishes, or surrogate values, they reported still recommending tracheostomy to surrogates. Additional participant quotes for concrete decisional needs can be found in eTables 5-8.

Table 4.

Uncertainty

| So I’ve often wondered, have I let them try too much already? Should we have just said enough is enough? And it’s just hard to know when enough is enough. Because, of course, you don’t want to give up on your family member at all, especially when you’re the one making the decision. You don’t want to make that decision. But it’s just hard because you can’t foresee the future. (Surrogate ID5) |

| I think it’s difficult to make decisions for somebody. I know that I know her for a long time, but this is something we never actually talked about (Surrogate ID20) |

| Interviewer: Okay, has that been hard not knowing what your dad would’ve wanted if he got really sick? Interviewee: Well, it’s just hard bein’ in that position of knowing or not knowing, but having to make that decision [laughter] for him as far as what to do health wise, and it’s extremely uncomfortable. I believe that that was maybe the hardest part in this whole thing, not just because I didn’t know what my dad would want, but also because I am a firm believer in Jesus Christ. I didn’t want to play the role of God in any decision-making like that, though, as far as life and death. (Surrogate ID22) |

| Interviewee: I don’t know at first . . . I guess I was just worried. I was worried if he would be able to breathe on his own, and then I was also worried as far as how long they would be allowed to leave him on there ‘cause I wasn’t really sure how that worked, if they could only leave him on there for a certain amount of days, and then take him off. Interviewer:Gotcha, so that uncertainty? Interviewee: Mm-hmm. (Surrogate ID23) |

| I guess it’s usually tailored to the clinical situation, but there’s always uncertainty, so I’ll usually—the hope would be that this would be a short-term thing and I guess that’s one other thing that I usually add on to your prior question which if this is reversible? You can take it out and the hole will heal up and go away, usually within days. . . I think it’s, hopefully, temporary, but it’s always hard to know. May often translate into leaving the hospital to go to a long-term acute care hospital, so different physical settings. Sometimes that can be seen as at least an encouraging sign of recovery to make it out of the hospital, but also to know that it could be something that goes on for days, weeks or even months. In rare cases, it’s clear that it’s going to be indefinite, in which case I’ll certainly try not to pull any punches here in these discussions and I’ll let them know if I think it will be indefinite. (Physician ID35) |

Shared Decision-Making Interventions

Key decisional needs emerged from the interaction of the qualitative themes and factors and informed by specific questions about aspects of a potential SDM intervention that could improve the decision-making process. Surrogates overwhelmingly felt that greater education was needed to guide the decision-making process, “Education stuff is really what I would want” (Surrogate ID7). Both groups identified early values clarifications, discussions about long-term implications including rehabilitation facilities, and robust outcome predictions as being essential to any attempt to improve decision-making. Surrogates indicated that they wanted more information about what it meant to be a surrogate decision-maker and how they should approach the issue of substituted values. They also wanted more detailed descriptions about potential alternatives to long-term tracheostomy including time trial and palliative options. Many providers were in favor of a possible SDM tool if it could potentially standardize the approach to discussing tracheostomy, “I think that would be very helpful. I think they [surrogates] want numbers that I feel like I can’t provide them. What is his chance of coming off the vent? I end up really pulling numbers out of just from general sense of my past experience, which not good. ‘Cause everyone’s so different. It’s just if we could get those numbers, it’d be awesome. . . But I think that would be great.” (Physician ID27). However, they stated that any such tool would have to be flexible and ideally customizable such that it could be incorporated into their usual practices rather than be viewed as extra work or an extra step (Figure 2 and Table 5).

Table 5.

Elements of a Potential Shared Decision-Making Intervention

| . . . get an idea for the people that you’re dealing with, kind of their values, you know, what they’re hoping and anticipating for with their family members and their loved ones. And it’s something I have a great interest in, but sometimes there’s not always the time to pick up on those nuances (Physician ID32) |

| I’d like to know what’s going to happen short-term and long-term, and like I say, more information on if I have to put her in assisted living. (Surrogate ID2) |

| I think that could be helpful. Maybe if you entered personal stuff about, like if I entered my dad’s previous health concerns, maybe his age, and things like that, and they compared it to other tracheostomy patients. . . I would have looked at it if I had to ultimately make that decision, I would’ve looked at it. (Surrogate ID11) |

| I’m a visionary person. I like to see what you’re talking about in my mind or whatever, and I think if they would have explained to me even just like sometimes, you might go to the doctor’s office, and he has this skeleton up here. (Surrogate ID16) |

| I actually think it would be helpful to both depending on the ease of use. I actually think that the physicians sometimes need it more than the families because I think what happens is the physicians get so busy that they don’t ask the right questions before they have these trach discussions. But if it’s not easy enough to use, the physicians aren’t going to use it (Physician ID34) |

Discussion

In a prospective qualitative study, we identified qualitative themes that described the decision-making process and identified core decisional needs that highlighted information that surrogates and/or physicians felt they lacked during the decision-making process (Figure 1). Decisional needs were viewed through the lens of the qualitative themes that permeated the process. Moreover, decision-making was a highly interactive process between surrogates and providers with surrogates wanting active involvement from the physicians and often viewing them as partners in the process. The study further highlighted several possible components of a SDM tool that could address gaps in the decision-making process or inform decisional needs.

While much of the work on tracheostomy decision-making has been done with pediatric patients where parents are the primary surrogate, tracheostomy decisions for adult patients are fundamentally different.[11–14, 39] The causes of respiratory failure, prognoses, possibilities for long-term ventilation, and survival greatly differ. Our work highlights that for adults, palliative considerations are far more common and the desire to know about short- and long-term outcomes is similar to pediatric discussions but far less data exists on long-term outcomes for adults. While the pediatric literature can inform the adult approach to decision-making, the decisional needs for parents greatly differ from children/spouses making decisions for adult patients.

Few studies exist in the adult literature that attempt to describe adult surrogate decision-making, but multiple gaps remain. Cox et al described that surrogate expectations for recovery of patients being considered for tracheostomy rarely align with physician predictions but their study focused more on the end result than the process and the needs.[19] In a larger study of all ICU patients, Azoulay et al found that half of families in the ICU experience poor communication with provider teams leading to poor comprehension of disease state and potential for recovery, similar to our study.[23] Xu et al reviewed transcripts from family meetings and identified several decisional needs described by surrogates during those meetings but indicated that physicians rarely discussed them.[18] As Xu et al only reviewed family meetings, they could not investigate why the decisional needs they described were important or why providers did not address them during meetings. Therefore, large gaps remain in understanding the decision-making process and identifying decisional needs on the part of both surrogates and physicians. These gaps may be partly responsible for the failure of previous attempts at developing SDM interventions for adult tracheostomy and PMV and our study provides a roadmap for the development of future interventions.[40]

The qualitative themes that describe the decision-making process (Hope, Uncertainty, and Lack of Knowledge & Data) were non-linear and highly interactive. By non-linear, we mean that surrogates did not think about Hope, then think about Uncertainty, and then think about the things they did not know. Rather, the themes co-existed in surrogates’ minds at the same time, informing each other, or, at times, opposing one another. The qualitative themes reflected the surrogate’s value structure or the value structure of the patient as perceived by the surrogate and in many cases, the value structure evolved over time.

While Uncertainty was one of three themes to emerge, from one perspective, it could be viewed as central to all other themes. In 2011, Han et al described a new taxonomy for Uncertainty given its key importance in health care.[41] Han et al described multiple sub-types of Uncertainty in health care including prognostic Uncertainty, Uncertainty related to structures and processes of care, and existential Uncertainty. These subtypes of Uncertainty encompass many of the themes and factors identified in this study. Prognostic Uncertainty aligns with Lack of Knowledge & Data. Uncertainty related to structures and processes of care was akin to surrogate concerns about rehabilitation options. Existential Uncertainty also mirrored the classic intangible form of Uncertainty identified as a core theme in this study. This deeper understanding of Uncertainty may highlight some of the core struggles for surrogates and physicians.

The three major qualitative themes of Hope, Uncertainty, and Lack of Knowledge & Data interacted in a way that went beyond Han et al’s taxonomy and forms the foundation of the theoretical model. As stated, the Lack of Knowledge & Data could be viewed as a manifestation of Prognostic Uncertainty. However, for some surrogates, the Lack of Knowledge & Data actually fueled Hope. Several surrogates highlighted the fact that since little was known about potential outcomes, they were able to fall back on Hope for recovery. For some, Hope could have been diminished in the face of accurate prediction models. Similarly, Hope was also able to override Uncertainty. This often manifested as surrogates suggesting that they might choose more aggressive options (i.e., tracheostomy) even when a great deal of Uncertainty existed about the potential for recovery.

Understanding the decision-making process through qualitative themes provides a potential roadmap to improve the process. Surrogates clearly held onto Hope for recovery despite evidence that would suggest a low likelihood of meaningful recovery. Surrogates tended to indicate that physicians who acknowledged that Hope even while discussing the higher likelihood of a poor outcome spoke more to their needs. Surrogates also tended to hold onto mental pictures of their loved ones as healthy individuals, which often meant before they struggled with chronic illness. For the surrogate of a patient with interstitial lung disease on 6 liters per minute of supplemental oxygen before the acute decline, their mental image was not of their loved one attached to machines but of them healthy and active before they developed lung disease. Understanding this mental image can help physicians fill in gaps about the impact and severity of acute or chronic illness and acknowledging the surrogate’s Hope can help build trust. Similarly, surrogates struggled with their Uncertainty and Lack of Knowledge & Data. However, in many situations, they also recognized that the physicians did not know and could not predict every outcome. Many surrogates felt more comfortable when physicians more openly acknowledged their own Uncertainty and the gaps in the literature.

To design potential SDM interventions, this study also specifically explored possible elements that surrogates and/or providers believed would improve the decision-making process or address specific decisional needs. In some cases, Past Wishes cannot be known. However, using anecdotal evidence to infer prior wishes, such as avoidance of hospitals or ability to return to activities that previously brought them joy, is an application of both the qualitative themes and decisional needs that could improve the decision-making process and appealed to both surrogates and physicians. As illustrated in Figure 2, potential elements of a SDM intervention described by most participants stemmed directly from one or more qualitative themes and decisional needs where addressing the qualitative themes through better communication could improve the process and including more information about decisional needs could satisfy the need for greater knowledge. This relationship highlights the utility of the qualitative descriptions of decisional needs the potential of adapting them into an actionable framework to inform future SDM interventions.[40]

This study has multiple limitations. Despite transitioning to a theoretical sampling approach towards the end of the study, it remained difficult to enroll surrogates who had chosen not to pursue tracheostomy. While many expressed interest, not pursuing tracheostomy was often accompanied by the patient dying and surrogates struggled to commit to interviews while grieving. As such, there is a selection bias. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a nearly two-year interruption in recruitment as research was paused at an institutional level and because tracheostomy practices evolved during the first year of the pandemic. While the study was multi-center, different themes may influence decision-making in other regions and institutions related to different populations and different hospital structures. Surrogates and physicians were also interviewed separately and not as part of a dyad. Therefore, it was not possible to determine what was actually discussed during tracheostomy conversations, only surrogate recollections of what was said. However, surrogate experience and final decisions are always based in perceptions of decision-making conversations making the themes identified in this study highly relevant to improving the decision-making process. Finally, this study focused on surrogates and physicians. Nurses and respiratory therapists can also play a crucial role in tracheostomy decision-making with nurses spending the most time with patients and families of all providers. Due to limitations in the study, we were not able to interview nurses or respiratory therapists, and understanding their perceptions should be a focus of future investigations.

This study has multiple novel findings: (1) we describe the decision-making process through qualitative themes that apply to both surrogates and physicians in a way not previously done, (2) we highlight core decisional needs that surrogates and providers use to weigh final decision-making, and (3) we establish potential elements for a SDM intervention that can address existing decisional gaps. This work adds to the existing body of literature on complex decision-making and can serve as the foundation for SDM tools designed to improve goal-concordant care for adults being considered for tracheostomy and PMV.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Decision-making for tracheostomy and prolonged mechanical ventilation is a complex interactive process between surrogate decision-makers and providers.

Qualitative themes of Hope, Uncertainty, and Lack of Knowledge & Data shared by both providers and surrogates were identified and described the decision-making process.

Concrete decisional needs of Patient Wishes, Past Activity/Medical History, Short and Long-Term Outcomes, and Meaningful Recovery affected each of the larger themes and represented key information upon surrogates and providers based decisions and recommendations.

The qualitative themes and decisional needs identified provide a roadmap to design a shared decision-making intervention to improve adult tracheostomy and prolonged mechanical ventilation decision-making.

Acknowledgements:

ABM is supported by NIH K23HL141704 (Primary funding source). ABM had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. No authors had any conflicts of interest related to this study. The funders did not have any role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No authors have any conflicts of interest to report for this study.

References

- [1].HCUPnet. 2021. January 1 [cited 2021 July 1] Available from: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/

- [2].Mehta AB, Syeda SN, Bajpayee L, Cooke CR, Walkey AJ, Wiener RS. Trends in Tracheostomy for Mechanically Ventilated Patients in the United States, 1993–2012. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2015; 192(4):446–54. 10.1164/rccm.201502-0239OC [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mehta AB, Walkey AJ, Curran-Everett D, Douglas IS. One-Year Outcomes Following Tracheostomy for Acute Respiratory Failure. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47(11):1572–81. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Law AC, Stevens JP, Choi E, Shen C, Mehta AB, Yeh RW, Walkey AJ. Days out of Institution after Tracheostomy and Gastrostomy Placement in Critically Ill Older Adults. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022; 19(3):424–32. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202106-649OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mehta AB, Matlock DD, Shorr AF, Douglas IS. Healthcare Trajectories and Outcomes in the First Year After Tracheostomy Based on Patient Characteristics. Crit Care Med. 2023. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000006029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. The New England journal of medicine. 2012; 366(9):780–1. 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, Danis M, White DB, American College of Critical Care M, American Thoracic S. Shared Decision Making in ICUs: An American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Critical Care Medicine. 2016; 44(1):188–201. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001396 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Matlock DD, Spatz ES. Design and testing of tools for shared decision making. CirculationCardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2014; 7(3):487–92. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000289 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Michalsen A, Long AC, DeKeyser Ganz F, White DB, Jensen HI, Metaxa V, et al. Interprofessional Shared Decision-Making in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Recommendations From an Expert Panel. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47(9):1258–66. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, Mor V. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. Jama. 2004; 291(1):88–93. 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gower WA, Golden SL, King NMP, Nageswaran S. Decision-Making About Tracheostomy for Children With Medical Complexity: Caregiver and Health Care Provider Perspectives. Acad Pediatr. 2020; 20(8):1094–100. 10.1016/j.acap.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nageswaran S, Gower WA, Golden SL, King NMP. Collaborative decision-making: A framework for decision-making about life-sustaining treatments in children with medical complexity. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022; 57(12):3094–103. 10.1002/ppul.26140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nageswaran S, Gower WA, King NMP, Golden SL. Tracheostomy decision-making for children with medical complexity: What supports and resources do caregivers need? Palliat Support Care. 2022:1–7. 10.1017/s1478951522001122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Edwards JD, Panitch HB, Nelson JE, Miller RL, Morris MC. Decisions for Long-Term Ventilation for Children. Perspectives of Family Members. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020; 17(1):72–80. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201903-271OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jabre NA, Raisanen JC, Shipman KJ, Henderson CM, Boss RD, Wilfond BS. Parent perspectives on facilitating decision-making around pediatric home ventilation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022; 57(2):567–75. 10.1002/ppul.25749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hebbar KB, Kasi AS, Vielkind M, McCracken CE, Ivie CC, Prickett KK, Simon DM. Mortality and Outcomes of Pediatric Tracheostomy Dependent Patients. Front Pediatr. 2021; 9:661512. 10.3389/fped.2021.661512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu P, Teplitzky TB, Kou YF, Johnson RF, Chorney SR. Long-Term Outcomes of Tracheostomy-Dependent Children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023; 169(6):1639–46. 10.1002/ohn.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xu L, El-Jawahri AR, Rubin EB. Tracheostomy Decision-making Communication among Patients Receiving Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021; 18(5):848–56. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1217OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cox CE, Martinu T, Sathy SJ, Clay AS, Chia J, Gray AL, et al. Expectations and outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Critical Care Medicine. 2009; 37(11):2888–94. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ab86ed [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rubin EB, Buehler AE, Halpern SD. States Worse Than Death Among Hospitalized Patients With Serious Illnesses. JAMA internal medicine. 2016; 176(10):1557–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4362 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Thompson BT, Cox PN, Antonelli M, Carlet JM, Cassell J, Hill NS, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003: executive summary. Critical Care Medicine. 2004; 32(8):1781–4. 00003246–200408000-00023 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].White DB, Malvar G, Karr J, Lo B, Curtis JR. Expanding the paradigm of the physician’s role in surrogate decision-making: an empirically derived framework. Critical Care Medicine. 2010; 38(3):743–50. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c58842 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Critical Care Medicine. 2000; 28(8):3044–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, Fowler RA. Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: a systematic review. Critical Care Medicine. 2011; 39(5):1174–89. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eacf2 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jivraj NK, Hill AD, Shieh MS, Hua M, Gershengorn HB, Ferrando-Vivas P, et al. Use of Mechanical Ventilation Across 3 Countries. JAMA Intern Med. 2023; 183(8):824–31. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ottawa Decision Support Framework. 2022. October 10 [cited 2023 December 15] Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/odsf.html

- [27].Hoefel L, Lewis KB, O’Connor A, Stacey D. 20th Anniversary Update of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework: Part 2 Subanalysis of a Systematic Review of Patient Decision Aids. Med Decis Making. 2020; 40(4):522–39. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hoefel L, O’Connor AM, Lewis KB, Boland L, Sikora L, Hu J, Stacey D. 20th Anniversary Update of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework Part 1: A Systematic Review of the Decisional Needs of People Making Health or Social Decisions. Med Decis Making. 2020; 40(5):555–81. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Stacey D, Légaré F, Boland L, Lewis KB, Loiselle MC, Hoefel L, et al. 20th Anniversary Ottawa Decision Support Framework: Part 3 Overview of Systematic Reviews and Updated Framework. Med Decis Making. 2020; 40(3):379–98. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. 2019. May 31 [cited 2020 May 10]Available from: http://www.ipdas.ohri.ca/

- [31].Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, Volk R, Edwards A, Coulter A, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2006; 333(7565):417. bmj.38926.629329.AE [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007; 19(6):349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd edition. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Starks H, Trinidad SB. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative health research. 2007; 17(10):1372–80. 17/10/1372 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Reczek C. Conducting a multi family member interview study. Family process. 2014; 53(2):318–35. 10.1111/famp.12060 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006; 18(1):59–82. 10.1177/%2F1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Guest G, Namey E, Chen M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One. 2020; 15(5):e0232076. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Clandinin DJ. Qualitative Analysis, Anthropology. In: Kempf-Leonard K, ed. Encyclopedia of Social Measurement: Elsevier Inc. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mack C, Mailo J, Ofosu D, Hinai AA, Keto-Lambert D, Soril LJJ, et al. Tracheostomy and long-term invasive ventilation decision-making in children: A scoping review. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2024. 10.1002/ppul.26884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cox CE, White DB, Hough CL, Jones DM, Kahn JM, Olsen MK, et al. Effects of a Personalized Web-Based Decision Aid for Surrogate Decision Makers of Patients With Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 170(5):285–97. 10.7326/m18-2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Han PK, Klein WM, Arora NK. Varieties of uncertainty in health care: a conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Making. 2011; 31(6):828–38. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.