Abstract

KRAS is one of the most frequently mutated oncogenes across various cancers. Oncogenic KRAS mutations rewire cellular signaling, leading to significant alterations in gene expression. RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) play a pivotal role in gene expression regulation by post-transcriptionally controlling various aspects of RNA metabolism. It has become clear that interactions between RBPs and RNA are frequently dysregulated in numerous cancers. However, how oncogenic KRAS mutations reshape the post-transcriptional regulatory network mediated by RBPs remains poorly understood. In this study, we systematically dissected oncogenic KRAS-driven alterations of RNA-RBP networks. We identified 35 cancer-associated RBPs with either increased or decreased RNA binding upon oncogenic KRAS activation, including PDCD11, which is essential for the viability of KRAS mutant cancers, and ELAVL2, which regulates cell migration in KRAS mutant lung cancers. Our study serves as a crucial resource for elucidating RBP regulatory networks in KRAS mutant cancers and may provide new avenues for therapeutic strategies targeting KRAS mutant malignancies.

Subject terms: Mechanisms of disease, Oncogenes, Lung cancer, Proteomics, RNA metabolism

Introduction

Post-transcriptional regulation, encompassing mRNA processing, mRNA transport, mRNA stability, and translational regulation, plays a pivotal role in gene expression1. RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are key post-transcriptional regulators, dictating the function and fate of mRNAs at every stage of post-transcriptional regulation2,3. An accumulating body of evidence suggests that RBPs are dysregulated in cancers, playing critical roles in various aspects of cancer biology including cancer development, invasion, metastasis, and resistance to cancer therapy4–7. The identification of cancer-associated RBPs has primarily relied on gene expression profiling, leveraging transcriptome data to discern RBPs that are upregulated or downregulated in cancers compared to normal tissues. However, transcript levels do not always correlate with protein abundance, and the total abundance of RBPs does not reflect RNA-bound RBPs (active RBPs). Thus, variations at the transcript level may not accurately represent alterations in the RNA-bound RBPs8–10. Therefore, studies on dynamic RNA interactions with RBPs are crucial to fully understand the impact of RBP-mediated post-transcriptional regulation on cancer development.

KRAS is one of the most frequently mutated oncogenes in various human cancers. In particular, its mutation occurs in 20–40% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with TP53 mutation often identified as a co-mutation11–13. KRAS mutation leads to constitutive activation of several downstream signaling pathways, including RAF/MAPK and PI3K/AKT, which are involved in cell growth, differentiation, and survival14. This in turn results in significant gene expression changes, promoting malignant transformation15. Furthermore, the gene expression changes in cancer can also result from aberrant post-transcriptional regulation16,17. However, the mechanisms through which oncogenic KRAS mutations reshape the post-transcriptional regulatory network, particularly those involving RBPs, are not fully understood. A recent study has demonstrated that oncogenic KRAS dynamically modulates a network of RBPs including nucleolin to induce cell proliferation and tumorigenesis18. This modulation was observed in the context of whole transcriptome interactions governed by ERK signaling, downstream of KRAS, in pancreatic cancers. Nevertheless, our understanding of the changes in the mRNA interactome in response to oncogenic KRAS, particularly in lung cancer and other cancer types, is still limited.

In this study, we systematically examined RNA-bound RBPs in lung isogenic cell lines with KRAS mutation using the mRNA interactome capture (RIC) method. This approach allowed us to discover the changes in mRNA-RBP interactions that occur during the development of lung cancer driven by oncogenic KRAS. We identified 35 RBPs that exhibit significantly altered RNA binding, including PDCD11 and ELAVL2, which play roles in survival and migration in KRAS mutant lung cancers.

Results

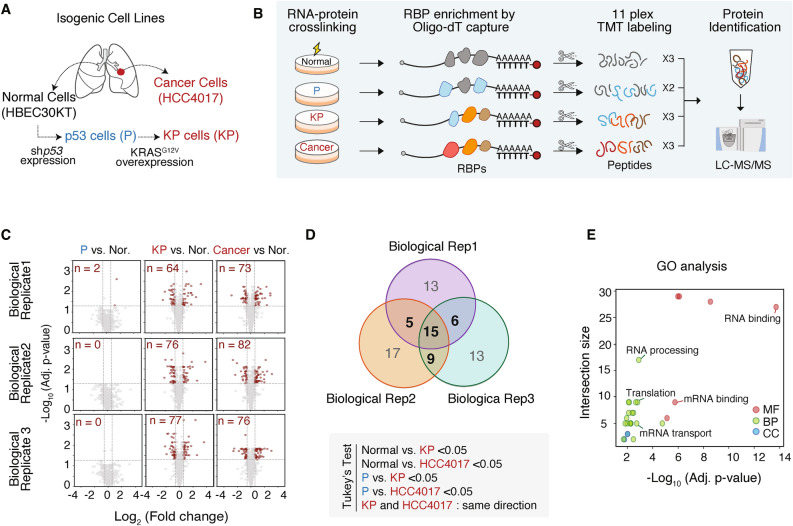

RNA binding landscape changes during oncogenic KRAS-driven tumorigenesis

To understand the alterations in post-transcriptional regulation driven by oncogenic KRAS activation, we set out to examine the global landscape of the RBPome using a matched tumor/normal pair (HCC4017/HBEC30KT) derived from a 62-year-old female smoker with stage 1A adenocarcinoma19. For a comprehensive interrogation of lung cancer pathogenesis, we simultaneously examined isogenic cell lines that were stepwise-transformed to full malignancy by introducing specific genetic modifications : a loss of p53 in “P” cells and a KRAS mutation in “KP” cells (Fig. 1A)20. To identify the RNA-bound RBPs (active RBPs) in each cell, we employed formaldehyde crosslinking combined with RNA interactome capture (FAX-RIC)21. This was followed by 11-plex TMT-based protein profiling, which includes technical triplicates of HBEC30KT cells (normal cells), technical duplicates of P cells, technical triplicates of KP cells, and technical triplicates of HCC4017 cells (Fig. 1B). We performed three independent experiments (three biological replicates) and detected a total of 794 RBPs (Figure S1A, Table S1).

Fig. 1.

RNA binding landscape changes during oncogenic KRAS-driven tumorigenesis. (A) Schematic representation of stepwise-transformed isogenic cell lines derived from normal human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC30KT) and cancer cell lines (HCC4017) from a lung cancer patient. Normal cells were immortalized and engineered to generate p53-depleted cells (P cells) through shp53 expression, and P cells were transformed into KP cells through KRASG12V overexpression. (B) Experimental workflow for TMT-based quantitative profiling of RNA-bound proteins. Isogenic cell lines were subjected to FAX-RNA interactome capture followed by 11-plex TMT labeling and LC–MS/MS. (C) Volcano plots showing the Log2 fold change (X-axis) and its significance (adjusted p-value, Y-axis) of captured RBPs in P, KP, and cancer cells compared to normal cells (Nor.) across three biological replicates. RBPs with Benjamini–Hochberg corrected unpaired t-test p < 0.05 and |fold change|> 1.5 are highlighted in red. The number of the RBPs in red is indicated in each plot. (D) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of significantly altered RBPs in KP and cancer cells across three biological replicates. Tukey’s test was performed to determine the significantly altered RBPs, with the criteria indicated below the Venn diagram. (E) Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the 35 KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs using g:Profiler, highlighting the biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC). The size of the intersections represents the number of proteins involved in each category, and the -Log10 (adjusted p-value) indicates the significance of enrichment.

In each biological replicate, we examined the dysregulation of RBP-RNA interactions in transformed cells compared to their normal counterparts. An increase in the number of RBPs with altered RNA binding was evident in the more malignant cell lines (Fig. 1C). To identify RBPs that exhibited significant changes in their association with RNA–either increased or decreased binding–specifically in malignant cells (KP and HCC4017), we performed Tukey’s test using the following criteria : Normal vs. KP < 0.05, Normal vs. HCC4017 < 0.05, P vs. KP < 0.05, P vs. HCC4017 < 0.05. Among the 794 RBPs assessed, 35 RBPs (~ 5% of the RBPome) exhibited differential RNA association in the context of oncogenic KRAS expression across at least two biological replicates (Fig. 1D). Of these, 14 RBPs showed increased RNA binding, whereas 21 RBPs exhibited decreased binding in malignant cells (Figure S1B). These RBPs are termed “KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs”. Gene ontology analysis demonstrated that most of them are conventional RNA-binding proteins with functions related to mitochondrial RNA processing, translation, and mRNA transport (Fig. 1E).

We next investigated if these KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs are differentially expressed in cancers. We compared the transcriptome of KRAS mutant lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and normal tissue from TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas Program). This analysis revealed that the majority of KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs do not exhibit differential RNA expression in KRAS mutant LUAD compared to normal tissue (Figure S1C, Tables S2,3). This suggests that transcript levels of the RBPs may not directly correlate with their protein expression levels, highlighting the importance of RBPome analysis in dissecting dysregulated RBP networks in pathological conditions. Collectively, our RBPome analysis reveals that oncogenic KRAS activation leads to significant alterations in the RNA-binding activities of approximately 5% of RBPs, suggesting a notable reshaping of the post-transcriptional regulatory network.

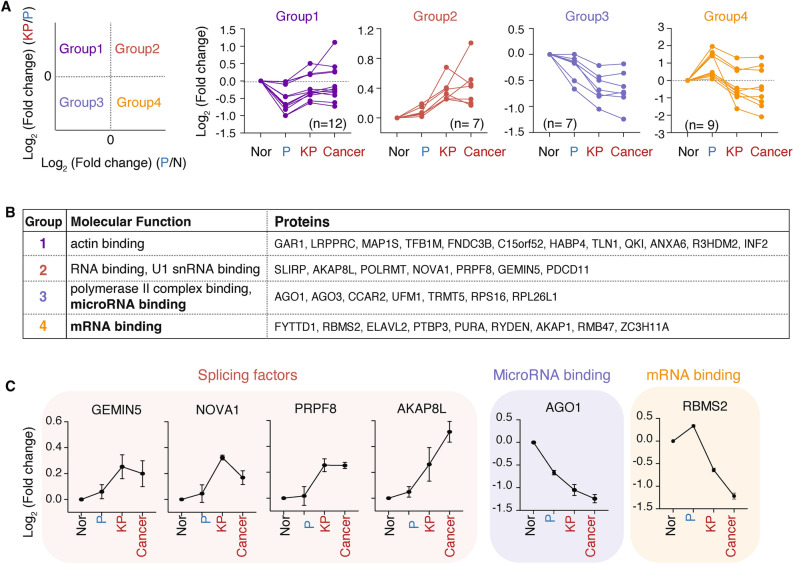

KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs exhibit distinct RNA binding patterns and functional roles in lung tumorigenesis

The kinetics of RBP activation and inhibition can provide valuable insights into the functional impact of proteins on gene regulation22. To elucidate RBP responses during lung tumorigenesis, we clustered the KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs based on their fold changes. Half of these RBPs showed a gradual increase (Group2) or decrease (Group 3) in RNA binding activity during stepwise transformation, while others in Group 1 and 4 showed complex RNA binding patterns, decreasing RNA binding with p53 depletion and increasing with concomitant KRAS mutation, or vice versa (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs exhibit distinct RNA binding patterns and functional roles in lung tumorigenesis. (A) Categorization of 35 KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs into four groups based on their Log2 fold change of RNA binding in KP cells compared to P cells (KP/P, Y-axis) versus in P cells as compared to normal cells (P/N, X-axis). Data are shown as the mean of three biological replicates. (B) Molecular function(s) enriched in each group, returned by GO analysis using g:Profiler. (C) Line plots depicting the Log2 fold change of indicated RBPs across P, KP and cancer cells as compared to normal cells (Nor). Data are shown as the mean of three biological replicates ± s.d.

One of the molecular functions highly enriched in Group 3 was microRNA binding, consistent with the previous notion that the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) in cancers is shortened and exhibits less microRNA binding activity (Fig. 2B, C)23. Group 2 and 4 RBPs are related to RNA binding, while Group 1 RBPs are less relevant to RNA metabolism. Among Group 4 RBPs, RBMS2, RBM47, and ELAVL2 were identified as 3’ UTR binders (Fig. 2C). Consistent with its decreased binding to RNA in malignant cells, RBMS2 was previously reported to bind and stabilize the mRNA of p21 and exert anti-proliferative roles24. RBM47 has been shown to have a complex role in cancer biology, serving as both a tumor suppressor and promoter depending on the context25–28. ELAVL2’s function in cancers is less understood. Among Group 2, RBPs involved in RNA splicing were identified, including GEMIN5, NOVA1, PRPF8, and AKAP8L, reflecting the aberrant and uncontrolled splicing events in cancers (Fig. 2C)29.

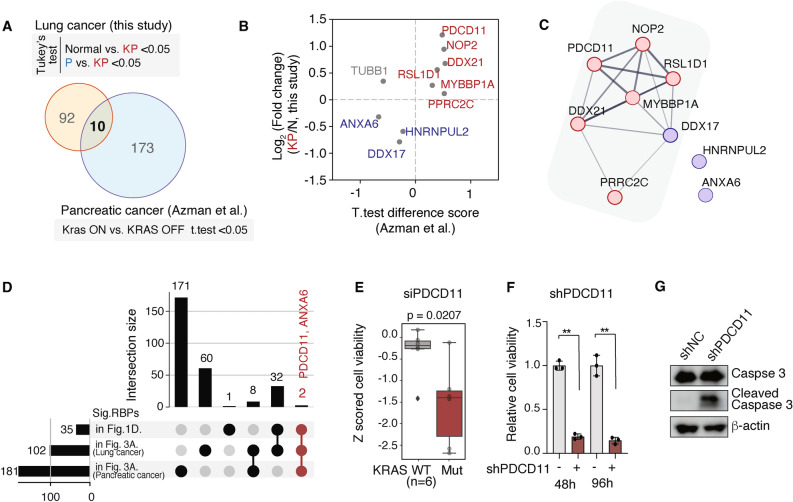

Comparative analysis identifies PDCD11 as a potential therapeutic target in KRAS mutant cancers

To examine if the changes in the RBPome upon oncogenic KRAS activation are specific to lung cancer or shared with other cancers, we analyzed our RBPome data together with that from PDAC cells. Recently the Mardakeh group reported the RBPome landscape of pancreatic cancer cells using an inducible oncogenic Kras model system18. We began by identifying RBPs that showed differential RNA associations in KP cells compared to P cells and normal cells, in at least two biological replicates (Figure S2A, Table S1). HCC4017 cancer cells were excluded in this analysis to focus solely on changes induced by KRAS activation. We identified 102 RBPs with enrichment in translation and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) processing (Figure S2B). Cross-referencing these RBPs with those dysregulated in PDAC cells (Fig. 3A), we found only 10 RBPs overlapping in both datasets, with 9 showing consistent upregulation or downregulation (Fig. 3B). This suggests that the influence of oncogenic KRAS on the RBPome may be context-dependent.

Fig. 3.

Comparative analysis identifies PDCD11 as a potential therapeutic target in KRAS mutant cancers. (A) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of significantly altered RBPs in two studies (this study and Azman et al.). RBPs significantly altered in each study were determined using the indicated criteria. (B) Scatter plot showing the t-test difference score determined in Azman et al. (X-axis) and Log2 fold change determined in this study of the 10 RBPs commonly detected in both datasets. (C) Protein–protein interaction network of 9 RBPs from (B) with STRING (full string network with medium confidence). Line thickness indicates the strength of data support. TUBB1 was excluded since its binding to RNA upon KRAS activation was regulated in opposite ways in two datasets. (D) Upset plot illustrating the overlap of RBPs detected in the indicated analyses. (E) Box plot showing cell viability following PDCD11 depletion in KRAS WT (H1395, H1819, H1993, H2073, HCC95, and HCC366) versus KRAS mutant NSCLC cell lines (HCC4017, 2009, H460, HCC44, H2122, and H1155). Box plots indicate median and interquartile range. Unpaired t-test. (F) The effect of PDCD11 knockdown on cell viability in H2009 cells. H2009 cells infected with lentivirus carrying shPDCD11 were subjected to puromycin selection for 3 days, followed by MTT assay 48 and 96 h post-selection. Data are shown as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). ** p < 0.01, Unpaired t-test. (G) Expression levels of Caspase-3 and cleaved Caspase-3 in H2009 stably expressing shPDCD11. H2009 cells infected with lentivirus carrying shPDCD11 were subjected to puromycin selection for 3 days, followed by western blot analysis one day post-selection. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Further interactome analysis revealed that 7 out of the 9 RBPs are known to interact with each other both functionally and physically, with roles related to ribosome biogenesis (Fig. 3C). Among these, PDCD11 and ANXA6 belong to KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs (Fig. 3D). To explore the functional relevance of these RBPs in KRAS mutant cancers, we employed publicly available whole-genome siRNA screening data from 12 NSCLC cell lines and determined if KRAS mutant cancer cells are more vulnerable to depletion of these RBPs30. While ANXA6 depletion had no effect (Figure S2C), PDCD11 depletion selectively reduced the viability of KRAS mutant lung cancer cells (Fig. 3E). Consistently, shPDCD11 expression in H2009 KRAS mutant cancer cells resulted in decreased cell viability and increased cleaved caspase-3 expression (Figs. 3F, G and S2D), indicating that PDCD11 can be a potential therapeutic target in KRAS mutant cancers.

Exploration of the RBPs with decreased RNA binding reveals ELAVL2 as an important regulator of cell migration in KRAS mtuant lung cancer cells

Most loss-of-function screens aimed at identifying cancer-related RBPs have focused on overexpressed or activated RBPs in cancers31. This led us to direct our attention toward RBPs with reduced activity in cancers. We identified 21 RBPs that exhibited decreased RNA binding (down-RBPs) (Fig. 4A). We examined protein expression levels of 4 down-RBPs in three KRAS mutant lung cancer cell lines (HCC4017, H2009, and H460) along with normal cells (HBEC30KT) (Fig. 4B). ELAVL2 and AGO3 were downregulated in KRAS mutant cancer cells, while the expression of FYTTD1 and RBMS2 remained unchanged upon KRAS mutation. This suggests that dysregulated RBP binding may not necessarily correlate with changes in protein abundance.

Fig. 4.

Exploration of the RBPs with decreased RNA binding reveals ELAVL2 as an important regulator of cell migration in KRAS mutant lung cancer cells. (A) Bar graph showing the Log2 fold change of RBPs with decreased RNA binding in KRAS mutant cells (KP and cancer cells) compared to normal cells. ELAVL2 is among the most significantly affected RBPs. (B) Expression levels of ELAVL2 and other RBPs (FYTTD1, RBMS2, AGO3) in HBEC30KT (normal) and KRAS mutant lung cancer cell lines (HCC4017, H2009, and H460). GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) The effect of ELAVL2 overexpression on cell viability in H2009 cells. Representative images of cell viability are shown on the left, with quantification of relative cell viability determined by MTT assay on the right. MTT assay was performed 72 h after pCK-Flag-ELAVL2 transfection. Data are shown as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). ** p < 0.01, unpaired t-test. (D) The effect of ELAVL2 knockdown on cell viability in P cells. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. MTT assay was performed 48 and 72 h after siELAVL2 transfection. Data are shown as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). *p < 0.05, unpaired t-test. (E) The effect of ELAVL2 knockdown on cell migration in P cells. In vitro wound healing assay was performed 72 h after siRNA transfection. Representative images of cell migration at 0 and 9 h post-wound are shown on the left, with quantification of cell migration (fold change relative to 0 h) using ImageJ on the right. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, unpaired t-test. (F) The relative RNA levels of ECM and EMT-related genes in P cells following siELAVL2 transfection. P cells were harvested 48 h after siRNA transfection, and subjected to RT-qPCR. Data are shown as mean ± s.d. (n = 4). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, unpaired t-test.

Among the down-RBPs, ELAVL2 showed the most notable change in RNA binding activity in malignant cells (Cancer and KP cells) as compared to normal cells (Fig. 4A). ELAVL2 is a member of the ELAVL mRNA-binding proteins containing three RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) that predominantly bind to AU-rich regions in the 3’ UTR of mRNA (Figure S3A)32. Its paralog, ELAVL1 (also known as HuR), has been found to regulate the stability and translation of mRNA involved in cell proliferation and cancer progression33,34. However, the potential function of ELAVL2 in cancers remains elusive. Despite their evident sequence similarity in RRM domains, the expression and binding amount of ELAVL1 were only marginally changed upon oncogenic KRAS activation (Figure S3B,C). In contrast, ELAVL2 showed a marked increase in binding to RNA in P cells and a substantial decrease in KRAS mutant cells (KP cells and cancer cells) (Figure S3B).

Given that ELAVL2 expression was notably downregulated in cancer cells, we examined the effect of ELAVL2 overexpression in cancer cells. To that end, we chose H2009 cells, a KRAS mutant lung cancer cell line that can be efficiently transfected with plasmids. Ectopic expression of ELAVL2 in H2009 cells resulted in reduced cell viability (Fig. 4C). Conversely, in P cells that highly express ELAVL2, we instead depleted ELAVL2 to examine if ELAVL2 downregulation promotes cancer-associated properties. The knockdown of ELAVL2 had little effect on cell viability, but significantly enhanced cell migration (Fig. 4D,E).

To understand the molecular mechanism underlying the role of ELAVL2 in cell migration, we investigated the expression levels of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers and extracellular matrix (ECM) components. ELAVL2 depletion in P cells showed complex results in the expression of mesenchymal markers. SNAIL2 was upregulated upon ELAVL2 depletion, while other mesenchymal markers (SNAIL1, TWIST, and TGF-β) were downregulated (Fig. 4F). However, it was interesting that the expression of ECM markers changed toward ECM degradation—upregulation of FN1, MMP9, and Integrin β1—which is closely associated with cell migration (Fig. 4F). We also overexpressed ELAVL2 in H2009 cells and examined the expression of EMT markers and ECM components. Since overexpression of ELAVL2 is detrimental to H2009 cells, we were not able to detect drastic upregulation of ELAVL2 upon transient ectopic expression. Nevertheless, it is notable that ELAVL2 overexpression in H2009 cells led to significant downregulation of SNAIL2, FN1, and MMP9, which is the opposite phenotype to ELAVL2 depletion (Figs. 4F, S3D, and S3E). This suggests that the SNAIL2-FN1-MMP9 axis may be primarily involved in increased migration observed following ELAVL2 depletion. Collectively, these results suggest that reduced ELAVL2 binding to RNA in KRAS mutant lung cancer cells may contribute to enhanced cell migration and invasion.

Discussion

In this study, we provide a systematic and comprehensive analysis of RNA–protein interactome alterations driven by KRAS activation, employing stepwise-transformed isogenic cells and their NSCLC counterpart. We demonstrate that KRAS activation substantially remodels the RBPome, as evidenced by altered binding activities in approximately 5% of RBPs, which may have wide-ranging implications for gene expression regulation.

Our analysis revealed that changes in the RBPome can occur independently of protein abundance, underscoring the limitations of previous approaches that sought to identify dysregulated RBPs solely based on transcriptome analysis. Since RBPs exert their function by binding to RNA, it is critical to investigate RNA-RBP interaction changes to dissect functionally important RBPs in specific contexts.

KRAS is a relevant oncogene implicated in the development of various cancers, including NSCLC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and colorectal cancer (CRC). A recent study reported on RBPome changes following oncogenic Kras induction in mouse pancreatic cancer cells. A comparison of this dataset with ours revealed 10 dysregulated RBPs by oncogenic KRAS, with an enrichment of ribosome biogenesis-related RBPs, consistent with the previous notion that altered ribosome biogenesis is highly associated with cancer35. Nevertheless, it was surprising to observe the minimal overlap between the two datasets. This can be attributed to both biological and technical discrepancies including cancer context (PDAC vs. NSCLC), KRAS mutation variation (G12V vs. G12D), cell line system (doxycycline-inducible cell lines vs. permanently stepwise-transformed cell lines), and interactome capture methodologies (UV crosslinking followed by organic phase separation vs. formaldehyde crosslinking followed by oligo-dT capture).

Among the common RBPs identified, PDCD11 emerged as a key protein with significantly increased RNA binding in cancer cells and is essential for the survival of KRAS mutant cancer cells. PDCD11 is known to be involved in ribosomal RNA processing and assembly in the nucleolus. Additionally, it has been recently shown that PDCD11 has “extra-nucleolar” functions through interactions with proteins such as P53 and NFκB36. However, it is not clear how PDCD11 influences RNA processing outside the nucleolus and how KRAS engages PDCD11 for tumorigenesis. Further investigation into the role of PDCD11 in KRAS-driven cancer development is warranted.

Additionally, we identified several cancer-associated RBPs, particularly those with decreased RNA binding activity (down-RBPs). Notably, Argonaute (AGO) proteins, components of RNA-induced silencing complex, displayed decreased RNA binding. This aligns with the previous findings that cancer cells express mRNA isoforms with shorter 3’ UTRs to evade microRNA binding23. Among the down-RBPs, we further investigated the functional role of ELAVL2 in cancers. Our results suggest that ELAVL2 has an anti-cancer role in KRAS mutant lung cancer cells. We found that ELAVL2 inhibits cell migration by regulating SNAIL2 and ECM components, including FN1 and MMP9. Corroborating our observations, a recent study has reported that ELAVL2 is often deleted, and its loss facilitates mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma37,38. Given the significant sequence homology between ELAVL1 and ELAVL2, particularly within the RRM domains, the divergent functional impacts of these proteins on cancer were unexpected. We speculate that low sequence conservation at both the N-terminus and the region between RRM2 and RRM3 may potentially enable the paralogs to participate in a variety of ribonucleoprotein complexes, contributing to functional diversity32. Further studies on their binding partners and target RNAs will help us to comprehensively understand how KRAS mutant lung cancer engages these paralogs for their survival.

Our work highlights the dynamic modulation in protein and RNA interactions upon oncogenic KRAS activation in lung cancer, offering a potential catalog of cancer-related RBPs linked to oncogenic KRAS. Further research on these RBPs will provide valuable insights into additional layers of gene regulation mechanisms in cancer biology, potentially leading to the identification of novel therapeutic targets and strategies for KRAS mutant lung cancer treatment.

Limitation of the study

Despite the in-depth analysis of RNA–protein interactome changes driven by oncogenic KRAS activation, our analysis employed isogenic cell line system, which may not fully reflect the complexicities of cancer biology observed in vivo. Future studies with animal models would help validate our findings and their translationl relevance. In addition, our study focused on the identification and initial functional characterization of KRAS-responsive Cancer RBPs. Further investigation will be necessary for more comprehensive understanding of their roles in KRAS mutant lung cancer.

Methods

Cell lines

HBEC30-derived isogenic cell lines and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines were obtained from The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The HBEC30 series and HCC4017 cells were cultured in ACL4 media (RPMI 1640 (Welgene) supplemented with 0.02 mg/ml insulin, 0.01 mg/ml transferrin, 25 nM sodium selenite, 50 nM hydrocortisone, 10 mM HEPES, 1 ng/ml EGF, 0.01 mM ethanolamine, 0.01 mM O-phosphorylethanolamine, 0.1 nM triiodothyronine, 2 mg/ml BSA, 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate) with 2% FBS (Welgene)30. Other NSCLC cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FBS. H2009 cells expressing shPDCD11 were established by infecting cells with a lentivirus carrying the puromycin resistance gene and shRNA sequences (Table S4), followed by puromycin selection for 3 days.

RNA interactome capture (RIC)

Cell crosslinking followed by RNA interactome capture was performed as previously described with some modifications21. Briefly, cells were crosslinked with 0.5% formaldehyde (Thermo Scientific) in PBS for 5 min at RT and then were washed twice with cold 200 mM Tris in PBS to quench the reaction. Cells were harvested, lysed with lysis buffer (0.5% (w/v) lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS), 500 mM lithium chloride (LiCl), 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA, and 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 4 M Urea (all Sigma-Aldrich)) and homogenized by passing through a 21-gauge needle syringe 20 times. The lysates were quantified by a BCA protein assay kit for reducing reagent (Pierce™, 23,250). Equal amounts of protein from each sample were subjected to oligo-dT capture.

Oligo-dT25 magnetic beads (NEB) were incubated with cell lysate for 1 h at RT and washed with buffers containing decreasing concetrations of LiCl and LiDS as previously described21,39. Poly(A) mRNAs and crosslinked proteins were eluted from the beads with 20 mM Tris containing 0.5 M EDTA. For protein analysis, reverse crosslinking was done by incubating the elutes at 65 °C overnight.

TMT-based quantitative profiling of RNA-bound proteins

The elutes were first made to be 4 M urea by addition of urea buffer (8 M urea in 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 8.5), added to the 30 kDa molecular weight cut off (MWCO) filter (Amicon 30 kDa, Merck Millipore) and centrifuged down to the minimum amount retained in the filter following the manufacturer’s protocol. Urea buffer with 10 mM DTT (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the filter and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and centrifuged down to the minimum amount. Urea buffer with 40 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in dark, followed by the centrifugation. Each sample was then washed with urea buffer and 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.5) twice each. Trypsin (1:50 w/w) in HEPES buffer was added to each sample and incubated at 37 °C for overnight. Each samples was then desalted using the C18 SPE cartridge (Supelco) and proceeded to the labeling step with TMT11plex reagents (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples were combined for the desalting with C18 SPE cartridge.

LC–MS/MS analysis

The sample was analyzed using an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled with nanoAcquity UPLC system (Waters). The sample was separated on an analytical column (75 μm i.d. × 100 cm) which was in-house packed with 3 μm of Jupiter C18 particles (Phenomenex). A linear gradient of solvent A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) was applied at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The gradient was set to be 5 to 8% solvent B for initial 10 min, 8 to 35% solvent B for next 230 min. Total run time for the SPS-MS3 analysis was 240 min with the following setup for MS acquisition; Full MS scans (m/z 375–1500) were acquired at a resolution of 120 k with 5E6 of AGC target value and 100 ms of Maximum Injection Time (ITmax). Selected precursor ions were first isolated at 0.7 Th of isolation window and subjected to HCD fragmentation for MS2 scans in orbitrap at a resolution of 15 k (ITmax 60 ms, AGC 1E6 and Collision Energy of 30%). The 10 most intense MS2 fragment ions were synchronously isolated in ion trap for final HCD MS3 scans at a resolution of 50 k and 0.4 Th of isolation width (AGC 5E5, ITmax 150 ms, and Collision energy of 65%). Overall, 3 s of cycle time was applied. MS data were searched against canonical protein sequences (SwissProt) of UniProt human reference proteome UP000005640 using MaxQuant (version 1.6.1.0) using default parameter for protein identification and TMT11plex quantification.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 89,901) supplemented with a 1X protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A32955). The lysates were then centrifuged at maximum speed for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were transferred to new tubes and quantified using BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23,227) and diluted equally with 5X sample buffer. Equal amounts of protein from each sample were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel (10% SDS solution) (Thermo Fisher Scientific AM9823) along with a protein ladder, transferred to a PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare, 0,600,023) and incubated overnight with the following primary antibodies : anti-FYTTD1 (Abcam, ab125082), anti-AGO3 (Cell signaling, 5054S), anti-RBMS2 (Santa Cruz, SC-514918), anti-ELAVL2 (RN005P; MBL life science), anti-ELAVL1 (Santa Cruz SC-5261) and anti-GAPDH (sc-47724; Santa Cruz). The membranes were washed with 1X TBS-T (TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) for 3 times and subsequently incubated with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson immunoResearch, 111–035-144). Signals were detected using the Amersham ImageQuant 800 system (Cytiva Life Sciences).

Transfection

For gene depletion, siRNAs were delivered to single-cell suspensions using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen™, L3000015) following the manufacturer’s protocol, at a final concentration of 20 nM siRNAs. The sequences of the synthetic siRNAs used in this study are listed in Table S4. For gene overexpression, cells were seeded one day before the transfection and transfected with the specified plasmid using fugene HD transfection reagent (Promega, E231A), in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

qPCR analysis

Cells were treated with RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara Bio Inc., 9109). RNAs were isolated using the Direct-zol RNA miniprep kit (Zymo Research, R2052) and then reverse-transcribed with PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio Inc., RR047A). The resulting cDNA was subjected to RT-qPCR using the CFX384TM Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad) utilizing SYBR Premix Ex Taq II and ROX plus (Takara Bio Inc.). The gene-specific primer sequences used in this study are listed in Table S4.

Wound-healing assay

P cells were transfected with either siNC or siELAVL2 in a 6-well plate, cultured for 2 days, and subsequently transferred to 12-well plates to reach 100% confluence. A 200μL yellow pipette tip was used to create a scratch in the center of each well. The cell free gaps were imaged in phase contrast using the Nikon software (NIS Elements) imaging system with a 4X objective on a Nikon Eclipse TS2 microscope (Nikon). Pictures were taken at 0 and 9 h after scratch formation. The size of the scratches in each group was measured using ImageJ software.

Cell viability assay

The MTT assay was performed to assess cell viability. For transfected cells, they were prepared in a 96-well plate, as mentioned in the Transfection section above, incubated for the designated time, and subjected to the MTT assay. For cells expressing shRNA, they were seeded in a 96-well plate, incubated for the indicated time, and subjected to the MTT assay. To conduct the assays, 5 mg/mL of MTT solution (Sigma, M5655) was added to each well (final concentration 0.5 mg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The medium was carefully removed, and 100 µL of DMSO (Sigma, 67–68-5) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (VersaMax).

TCGA data analysis

Transcriptome profiling data of 320 KRAS mutant LUAD tumors and 35 normal tissues were downloaded from the National Cancer Institute Genomic Data Commons data portal. TPM_unstranded counts from each data were log2 transformed and used for subsequent analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of the proteomics data were performed using Python. All other statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad PRISM.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. V. Narry Kim and her lab members for their insightful discussions and support at the initiation of this project. We like to give special thanks to Yoonseok Jung for initial analysis of the RBPome profiling data. We also thank Cheol Gi Chae for technical support. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by Korean government [NRF-RS-2023-0025229112982076870002 to J.K., NRF-2022R1C1C2003822 to Y.N.].

Author contributions

K-Y, B., J, S., and J, K. designed, performed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. Y, N., and J.-S, K. generated the LC–MS/MS data. J, K. conceived and supervised the project, and secured funding.

Funding

The National Research Foundation of Korea grant, NRF-2022R1C1C2003822, NRF-RS-2023-0025229112982076870002.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD053310. The data can be accessed at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/login using the reviewer token: rlhUbzMGsjdX.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-78333-2.

References

- 1.Corbett, A. H. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression and human disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol52, 96–104. 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.02.011 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Nostrand, E. L. et al. A large-scale binding and functional map of human RNA-binding proteins. Nature583, 711–719. 10.1038/s41586-020-2077-3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerstberger, S., Hafner, M. & Tuschl, T. A census of human RNA-binding proteins. Nat Rev Genet15, 829–845. 10.1038/nrg3813 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cen, Y. et al. Novel roles of RNA-binding proteins in drug resistance of breast cancer: from molecular biology to targeting therapeutics. Cell Death Discov9, 52. 10.1038/s41420-023-01352-x (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira, B., Billaud, M. & Almeida, R. RNA-Binding Proteins in Cancer: Old Players and New Actors. Trends Cancer3, 506–528. 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.05.003 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin, H. et al. RNA-binding proteins in tumor progression. J Hematol Oncol13, 90. 10.1186/s13045-020-00927-w (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohibi, S., Chen, X.B., and Zhang, J. (2019). Cancer the’RBP’eutics-RNA-binding proteins as therapeutic targets for cancer. Pharmacol Therapeut 203. ARTN 107390. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Liu, Y., Beyer, A. & Aebersold, R. On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell165, 535–550. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maier, T., Guell, M. & Serrano, L. Correlation of mRNA and protein in complex biological samples. FEBS Lett583, 3966–3973. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.036 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Sousa Abreu, R., Penalva, L. O., Marcotte, E. M. & Vogel, C. Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Mol Biosyst5, 1512–1526. 10.1039/b908315d (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adderley, H., Blackhall, F. H. & Lindsay, C. R. KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: Converging small molecules and immune checkpoint inhibition. EBioMedicine41, 711–716. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.02.049 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceddia, S., Landi, L., and Cappuzzo, F. (2022). KRAS-Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: From Past Efforts to Future Challenges. Int J Mol Sci 23. 10.3390/ijms23169391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Skoulidis, F. et al. Co-occurring genomic alterations define major subsets of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma with distinct biology, immune profiles, and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer Discov5, 860–877. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1236 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, L., Guo, Z., Wang, F. & Fu, L. KRAS mutation: from undruggable to druggable in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther6, 386. 10.1038/s41392-021-00780-4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell100, 57–70. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghoshdastider, U. & Sendoel, A. Exploring the pan-cancer landscape of posttranscriptional regulation. Cell Rep42, 113172. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113172 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jewer, M., Findlay, S. D. & Postovit, L. M. Post-transcriptional regulation in cancer progression : Microenvironmental control of alternative splicing and translation. J Cell Commun Signal6, 233–248. 10.1007/s12079-012-0179-x (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azman, M.S., Alard, E.L., Dodel, M., Capraro, F., Faraway, R., Dermit, M., Fan, W., Chakraborty, A., Ule, J., and Mardakheh, F.K. (2023). An ERK1/2-driven RNA-binding switch in nucleolin drives ribosome biogenesis and pancreatic tumorigenesis downstream of RAS oncogene. EMBO J 42, e110902. 10.15252/embj.2022110902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Kim, H. S. et al. Systematic identification of molecular subtype-selective vulnerabilities in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cell155, 552–566. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.041 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato, M. et al. Human lung epithelial cells progressed to malignancy through specific oncogenic manipulations. Mol Cancer Res11, 638–650. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0634-T (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Na, Y. et al. FAX-RIC enables robust profiling of dynamic RNP complex formation in multicellular organisms in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res49, e28. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1194 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamel, W. et al. Global analysis of protein-RNA interactions in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells reveals key regulators of infection. Mol Cell81(2851–2867), e2857. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.05.023 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayr, C. & Bartel, D. P. Widespread shortening of 3’UTRs by alternative cleavage and polyadenylation activates oncogenes in cancer cells. Cell138, 673–684. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.016 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun, X. et al. RBMS2 inhibits the proliferation by stabilizing P21 mRNA in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res37, 298. 10.1186/s13046-018-0968-z (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo, T. et al. RBM47 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression by targeting UPF1 as a DNA/RNA regulator. Cell Death Discov8, 320. 10.1038/s41420-022-01112-3 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu, X. C. et al. RNA-binding motif protein RBM47 promotes tumorigenesis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma through multiple pathways. J Genet Genomics48, 595–605. 10.1016/j.jgg.2021.05.006 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen, D. J., Jiang, Y. H., Li, J. Q., Xu, L. W. & Tao, K. Y. The RNA-binding protein RBM47 inhibits non-small cell lung carcinoma metastasis through modulation of AXIN1 mRNA stability and Wnt/beta-catentin signaling. Surg Oncol34, 31–39. 10.1016/j.suronc.2020.02.011 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing, Y. Q. & Zhu, T. Z. RNA-Binding Motif Protein RBM47 Promotes Invasiveness of Glioblastoma Through Activation of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Program. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers27, 384–392. 10.1089/gtmb.2023.0368 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerasuolo, A., Buonaguro, L., Buonaguro, F. M. & Tornesello, M. L. The Role of RNA Splicing Factors in Cancer: Regulation of Viral and Human Gene Expression in Human Papillomavirus-Related Cervical Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol8, 474. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00474 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim, J. et al. XPO1-dependent nuclear export is a druggable vulnerability in KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Nature538, 114–117. 10.1038/nature19771 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Einstein, J. M. et al. Inhibition of YTHDF2 triggers proteotoxic cell death in MYC-driven breast cancer. Mol Cell81(3048–3064), e3049. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.06.014 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulligan, M. R. & Bicknell, L. S. The molecular genetics of nELAVL in brain development and disease. Eur J Hum Genet31, 1209–1217. 10.1038/s41431-023-01456-z (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nabors, L. B., Gillespie, G. Y., Harkins, L. & King, P. H. HuR, a RNA stability factor, is expressed in malignant brain tumors and binds to adenine- and uridine-rich elements within the 3′ untranslated regions of cytokine and angiogenic factor mRNAs. Cancer Research61, 2154–2161 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdelmohsen, K. & Gorospe, M. Posttranscriptional regulation of cancer traits by HuR. Wires Rna1, 214–229. 10.1002/wrna.4 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelletier, J., Thomas, G. & Volarevic, S. Ribosome biogenesis in cancer: new players and therapeutic avenues. Nat Rev Cancer18, 51–63. 10.1038/nrc.2017.104 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding, L. et al. Programmed cell death 11 modulates but not entirely relies on p53-HDM2 loop to facilitate G2/M transition in colorectal cancer cells. Oncogenesis12, 57. 10.1038/s41389-023-00501-2 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhargava, S., Patil, V., Mahalingam, K., and Somasundaram, K. (2017). Elucidation of the genetic and epigenetic landscape alterations in RNA binding proteins in glioblastoma. Oncotarget 8, 16650–16668. 10.18632/oncotarget.14287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Kim, Y. et al. ELAVL2 loss promotes aggressive mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma. NPJ Precis Oncol8, 79. 10.1038/s41698-024-00566-1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castello, A. et al. System-wide identification of RNA-binding proteins by interactome capture. Nat Protoc8, 491–500. 10.1038/nprot.2013.020 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD053310. The data can be accessed at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/login using the reviewer token: rlhUbzMGsjdX.