Abstract

The value chain analyses of a product can provide vital information for improving the production, value addition, market organization and boost the contribution of the product to the income of the stakeholders involved. Hence, this study was carried out on the Garcinia kola value chain in Belabo, Cameroon. Twenty-three focus group discussions were held, and semi-structured surveys were administered to 135 stakeholders engaged in the G. kola value chain in the Belabo municipality. The results reveal that nuts, barks, and roots are the main parts collected. The nuts are marketed without processing while the barks and roots are consumed directly, marketed or processed into powder before consumption and marketing. G. kola value chain in Belabo has two levels of structuring, rural and urban. Nuts are sold by the unit or in buckets corresponding to the kilogram, with the price per nut ranging from 0.4 to 1.70 USD, depending on whether you're in the rural or urban market. It also varies according to production season and nut size. Barks and roots are sold all year round, generally in piled strips weighing approximately 100 g, with prices ranging from 0.17 to 1.75 USD on the rural and urban markets, respectively. The main stakeholders involved in the value chain are collectors/harvesters, local traders, retailers and wholesalers. Marketing provides more income to wholesalers and retailers, contributing over 35 % and 20 % to their annual income and less than 30 % and 15 %, respectively, to those of collectors and local traders. The major problems the G. kola value chain in this locality is facing are the attack of the product by weevils (24 % of citation), poor storage facilities and deforestation (14 %), price fluctuation, and lack of market (13.33 and 11.85 %). In Belabo, the marketing of G. kola is not profitable for the collectors, who are the main actors in the production chain characterized by rudimentary processing, poor storage and preservation techniques high marketing. The organization of the different stakeholder into association would help to better structuring the G. kola value in Belabo are the two main opportunities for improving the G. kola value chain with the potential of increase its contribution to the livelihoods of the different main stakeholders involved. In addition, policymakers should consider initiating innovations to boost production, support conservation, processing and price regulation to scale up economic and environmental benefits from G. kola.

Keywords: Garcinia kola, Value chain, Stakeholders, Marketing, Belabo, Cameroon

1. Introduction

Garcinia kola (Clusiaceae) is a multipurpose agroforestry tree species native to the tropical African forests of the Western and Central regions with significant cultural and economic relevance [[1], [2], [3]]. Commonly known as bitter kola [4], the Garcinia kola tree is a dioecious tree that can reach a height of 40 m. It grows in lowland tropical forests. The economic and folk medical benefits of bitter kola significantly impact the livelihoods of rural households. Its seeds, bark, and leaves are most prized for their therapeutic [[5], [6], [7]], stimulants and aphrodisiac properties. These plant parts are used to treat or alleviate the symptoms of several common illnesses, including gonorrhoea, liver disorders, headaches, respiratory and digestive problems [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. The medicinal properties of G. kola parts can also be classified as purgative, antiparasitic and antimicrobial. The nuts are rich in carbohydrates, protein and other plant metabolites [12]. Phytochemical analyses of the seeds reveal a high proportion of lysine and valine that can be used in food and feed formulations [13]. In addition to these physiological benefits, traditional societies in West and Central Africa recognize the strong symbolic values of bitter kola because it serves as an instrument of integration and social cohesion. It is reported that the nuts are commonly used as gifts when receiving visitors at home or wherever during many ceremonies such as traditional ceremonies and naming rituals [13,14].

Alongside the highly appreciated and sought-after G. kola nuts, barks and roots are harvested from wild trees in natural forests, plantations and agroforestry plots [15]. In Cameroon, there is an increasing demand for the various parts of G. kola. Indeed, G. kola parts are heavily traded in Cameroon and exported on a large scale to Nigeria, Gabon, Central African Republic and Equatorial Guinea [16]. Although G. kola is a Non-Timber Forest Product (NTFP) that has long been the subject of several socio-economic and ecological studies in Cameroon, its value chain has not yet been well documented and understood in most production sites. Previous studies have focused on the economic value of G. kola [[16], [17], [18], [19]], revealing sale prices, quantities sold, market and the annual incomes generated. According to Ref. [19], the most prized part of the G. kola species is the nut, which is marketed in Cameroon for more than half a million dollars a year. Studies reported that, G. kola is among the top twenty NTFPs traded and consumed in Cameroon, contributing an annual value of US$249,938 [20]. Although some information on marketed parts and market values is known in some areas, the economic value, commercialization trends and behaviour data are unavailable at the household level [21]. In addition, since G. kola is mainly a wild plant species, its production in rural areas involves mainly the harvesting of the different parts in the wild. Details of the harvesting of G. kola parts which include the harvesting period, harvesting techniques, harvesting frequencies and quantities harvested have not yet been investigated in most production basins in Cameroon including Belabo. Yet, knowledge of the problems facing the G. kola value chain provides the basis for its value chain improvement. Owing to the fact that NTFP collection is a major source of income and employment for forest dwellers with a multi-fold impact on the economy through downstream processing and trading activities [22], the value chain analysis of a particular NTFP can be used to assess the potential to support pro-poor sustainable development [23] in rural landscapes. A value chain denotes how often economic and financial values change and increase with the activities involved in bringing a product from the forest, through production, processing and delivery to the final consumers [24]. [25], defined market structure as the characteristics of the organisation of a market that appear to strategically influence the nature of competition and the behaviour of prices within the market. Thus, a well-structured market would ensure the economic and environmental sustainability of the resource, and an analysis of the product's value chain can provide useful information for this structuring. When NTFPs move from subsistence use to commercialization, the livelihoods of stakeholders involved, such as harvesters, processors, traders and consumers become interlinked through demand and supply value chain interactions [26]. Furthermore, analysing the value chain of forest products is a way to gain competitive advantage while conserving the resource base [27]. Because, NTFP harvesting and trade in Cameroon is largely informal and small-scale [28], a good knowledge of the value chain with an understanding of the constraints and opportunities for adding value to a product would provide reliable information that can help to better structure its value chain so that the marketing of the product would be more beneficial to all the actors involved in the value chain of the species and preserve biodiversity.

According to Ref. [29], even if it was not locally documented, G. kola represented and high economic value for local people who depend on this resource, with a price that tends to increase as these resources become more and more scarce. Although G. kola is a highly solicited NTFP marketed by the people of eastern Cameroon, its economic contribution to the general income of local populations of Belabo Cameroon, which is one of the production basins of the resource has not yet been studied. Hence, this study aimed to analyse G. kola value chain and its contribution to the annual household revenue of local populations in Belabo Cameroon. The purpose of this study is provide baseline information that can be used to improve the G. kola value chain and increase its contribution to the income and livelihoods of the rural population dependent of G. kola resources in the East region and other production basins of Cameroon.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Description of the study site

The current study was carried out in Belabo Subdivision in the Lom and Djerem Division of the East Region of Cameroon (Fig. 1). Belabo is located about 80 km from Bertoua and 60 km from Deng-Deng National Park at the latitude 5°9″ North and the longitude 10° 26” East. It covers an area of about 6000 Km2. Its population is estimated at about 45559 inhabitants, unevenly distributed over approximately 46 villages [30]. The climate is equatorial with four seasons that are irregularly distributed. This area belongs to the Guineo-Congolese forest domain, specifically the semi-deciduous forest [31]. The local population depends on agriculture, NTFPs harvesting, hunting, small trade, fishing, and livestock for their livelihoods [32]. The most collected NTFPs in the locality are Ricinodendron heudolotii (Djansang), Irvingia gabonensis (wild mango or bush mango), Garcinia kola (Bitter cola), Baillonnella toxisperma (Moabi) [30].

Fig. 1.

Study site.

2.2. Data collection

Between February and March 2022, the data were collected in 32 villages surrounding the Belabo communal forest based on their access to G. kola resources and access to its local market. Firstly, Focus Group Discussions (FGD) were held in the selected villages with local populations according to the recommendation of [33] which states that focus groups involve multiple participants who share one or more common characteristics that are important from a research perspective. Moreover, according to Ref. [29], when a study in a community involves governance and value chain, FGDs approach helps to build a trustworthy relationship between participants who provide common and complementary points of view with a high possibility reaching consensual facts that can be useful improving governance and transforming the value chain. Thus, FGD were done to identify harvesters, and determine if there were harvester organizations in the villages, of which a proportion was randomly chosen for interview according to the recommendation of [34]. Secondly, semi-structured interviews were held with 119 harvesters and 4 local traders in Belabo villages, based on their willingness and availability to participate in the survey (using a semi-structured questionnaire). Indeed [35], argue that the semi-structured interview is more powerful than other types of interviews because it allows the researcher to obtain in-depth information and evidence from the interviewee while taking into account the aim of the study. The major parameters taken into account during the interviews was: parts harvested, harvesting season, harvesting frequency, distance from home to harvesting site, processing and storage techniques, contribution to the livelihoods of the population, selling price per part harvested, destination of products, roles of the different stakeholders in the value chain, existence of producers association. A specific questionnaire was also addressed to 5 retailers and 7 wholesalers in the towns of Belabo and Bertoua based on their availability. The primary information requested from these two categories of stakeholders concerned the Market place, parts marketed, selling price, their role in the value chain, processing and storage techniques, the existence of sellers association, and the destination of products (representing the markets where the products are sold). The G. kola value chain was assessed according to the theoretical foundations of value chains as defined by Refs. [36,37].

2.3. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to provide substantial results related to this study concerning the quantities, prices, and values of G. kola traded by the different direct stakeholders in the study area. Common measurement units used in villages and markets were converted into metric units. Prices were given in dollars ($), with the exchange rate of 1 $ to 572.41 FCFA during the study period. The Frequency of Citation (FC) for each parameter was calculated, It corresponds to the ratio between the number of respondents that mentioned a particular response (n) and the total number of time that all responses were mentioned in the survey (N).

| FC = n/Nx100 |

3. Results

3.1. Production of Garciniakola in the study site

The results showed that the main harvesting sites are forest, agroforest and food crop fields. The populations affirmed that the main harvesting techniques are hand-picking for nuts (100 %), felling of trees (1.62 %) and slashing for bark (84.55 %), digging and uprooting for roots (13 % and 11.38 %, respectively). The harvesting of nuts is done by all people living in the villages (men, women and children), while the harvesting of bark and roots is done mainly by men and hunters for the majority. Harvesters reported that they walked an average of 1.5–30 km to collect the various parts in the forest. All respondents reported that the bark and roots are harvested throughout the year, while fruits are collected from February to March corresponding to long dry season and from June to October corresponding to long rainy season (Table 1).

Table 1.

Harvesting periods, seasons, techniques and frequencies for G. kola.

| Part harvested | Harvesting period | Harvesting Seasons | Harvesting techniques | Harvesting frequency per household (1 to 7 times/week) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit | February to March | major dry season | Hand-picking | 44 % |

| June to October | major rainy season | |||

| Bark | Throughout the year | Every four seasons | Slashing and felling trees | 41 % |

| Root | Throughout the year | Every four seasons | digging and uprooting | 15 % |

3.2. Harvesting process (harvesting technique, harvesting frequency, distance from the house harvesting site)

3.2.1. Post-harvest processing and storage

The analyses of focus group data revealed that the post-harvest processing varies according to the part of G. kola harvested. For the fruits, once they are collected, they can undergo two processes to obtain the seeds (nuts). Mature fruits are collected and directly scarified without touching the seeds and then left in a damp environment for 2–5 days for the pulp to rot. Once the pulp rots, the seeds are easily extracted. In the second option, the fruits are left to decompose for 3–6 days after which the seeds are extracted easily. The extracted seeds in both cases are washed thoroughly with water to remove the endocarp residue, then drained, dried and ready for consumption or commercialization. The nuts are sold untransformed into any derivative. The barks and roots are carefully cleaned and used to make various beverages, or they are dried, transformed into powder and packaged in tightly sealed containers.

Storage techniques also vary from nuts to roots and bark. However, similar storage techniques are used for roots and bark. Table 1 presents the post-harvesting techniques of G. kola done by collectors. In most cases, nuts are dried and kept in a cold environment (17.86 %), dried and wrapped in plastics (12.14 %) and dried and put in bags (11.43 %). 6.43 % said they do not conserve nuts. This proportion of respondent are those who harvest and sell their products immediately after processing. The least used conservation techniques are keeping in straw (5 %), burying inside the ground (4.22 %), wrapping in plastics and keeping in cold environments (2.86 %) and keeping at home by spreading on a bag or a tarpaulin (0.71 %). Concerning bark and roots, 4.29 % of respondents transformed bark and roots into powder form to conserve, 2.86 % dried and kept in a dry place while 0.71 % mentioned that they wrapped in leaves and kept in dry environments. However, 2.86 % do not use post-harvesting techniques to conserve the bark and root (Table 2). Using these techniques, the nuts can be kept for a duration that varies from one week to two years while bark and roots can be kept from one week to one year.

Table 2.

Post-harvest processing and storage techniques of G. kola in Belabo.

| Part | Post harvest processing and storage techniques | Number of citation | Frequency of citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nut | Drying and keeping in cold environments | 25 | 17.86 |

| Drying_wrapping in plastics | 17 | 12.14 | |

| Drying_putting in bags | 16 | 11.43 | |

| Wrapping in plastics_putting in bags | 14 | 10.00 | |

| Bottling | 13 | 9.29 | |

| Drying and wrapping in banana leaves | 13 | 9.29 | |

| Does not conserve | 9 | 6.43 | |

| Keeping in straw | 7 | 5.00 | |

| Burying inside the ground | 6 | 4.29 | |

| Wrapping in plastics_keeping in cold environments | 4 | 2.86 | |

| Keep at home by spreading on a bag or a tarpaulin | 1 | 0.71 | |

| Bark and Root | Powder form | 6 | 4.29 |

| Drying and keeping in a dry place | 4 | 2.86 | |

| Does not conserve | 4 | 2.86 | |

| Wrapping in leaves and putting in dry environment | 1 | 0.71 |

3.2.2. Destination of Garcinia kola and products in the study site

Regarding the destination of G. kola parts harvested and products derived (nuts, bark roots and powder), 53 % of the respondents reported that the latter were destined for commercialization, 47 % of the respondents reported that theirs were destined for auto-consumption (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Destination of G. kola products.

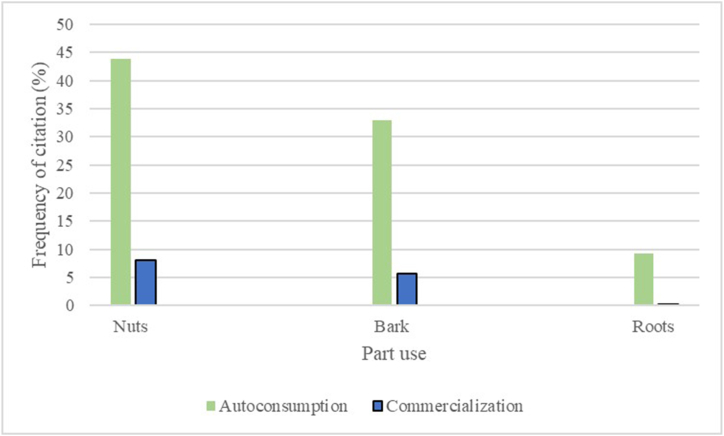

Detailed analyses of the destination of the different parts harvested revealed that 58 % of the population marketed the nuts, 40 % marketed the bark and 2 % marketed the roots of G. kola. Furthermore, 51 % of the respondents stated that they use the nut of Bitter kola nuts that they harvested in their homes (auto-consumption) or donated to others members of the community (the proportion of donations being very low was combined with auto-consumption) while 38 %11 % of respondents also used barks and roots, respectively at the level of their homes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Destination of different parts of G. kola.

3.2.3. Stakeholders involved and their roles in the Garcinia kola value chain

Four main categories of stakeholders involved in the G. kola value chain were identified in the context of this study. They were the collectors also referred to as harvesters (88 %) for the majority and mainly villagers in Belabo, retailers (5 %) who are urban citizens living in Belabo and Bertoua towns, wholesalers (4 %) living in Bertoua town, and local traders (3 %) who are rural citizen living in Belabo villages. Consumers were not quantified within the framework of this study since the majority of the entire population of the East region of Cameroon consumes the various products of G. kola and also because quantifying them could not add any value regarding the contribution of G. kola to the annual income of the different stakeholders involved.

The roles of the different stakeholders are embedded in the structural organization of the G. kola value chain. There are two levels of structuring in the G. kola value chain in Belabo: the rural and urban levels. At the rural level, the main stakeholders involved are collectors and local traders. At the urban level, the main stakeholders are retailers and wholesalers. Collectors are mainly involved in the harvesting of the different parts, they sell products in raw form and in processed form (only for bark and root), they generally sell product to locales traders and retailers and rarely to wholesalers. The local traders buy products in the various villages of Belabo town from collectors settled in their villages, and some go to neighbouring villages to obtain supplies, they collect large quantities which they sometimes sell to retailers or wholesalers. The retailers at the Belabo market obtain their supplies from collectors and local traders, they sell part of their products at their marketplaces while the remainder is sold to wholesalers of Bertoua, who come to the Belabo market for supplies. Wholesalers obtain their supplies from local traders and very rarely from collectors and retailers. They keep their products to sell to the retailers in the Belabo market, in the Bertoua market or national and international markets (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Garcinia kola Value chain in the East region of Cameroon.

3.2.4. Organization and marketing of Garcinia kola

Unlike in most cases where NTFP collectors are often grouped into producer groups (Associations or Common Initiative Groups or Cooperatives) that facilitate the harvesting, processing and marketing of products with favourable price negotiations, there were no producer groups for G. kola in Belabo. Products are collected and consumed locally or sold to local traders in the same village or from neighbouring villages, who buy and resell to semi-wholesalers in Belabo town. Semi-wholesalers retail a small portion of their stock while a high proportion of their stock is sold to wholesalers from Bertoua town.

Product prices are negotiated between the buyer and seller. At the local level, the measurement unit are the nut, the pile or the kilogram. Barks and roots are sold in piles (approximately 0.5 kg), or the kilogram (Table 3). At the village/rural market, the price of a G. kola nut varies from 0.04 to 0.09 USD, while the price of a bag of 50 kg varies from 26.21 to 52.45 USD. The price of a pile of bark or root (approximately 0.5 kg) varies according to quantity, with prices ranging from 0.17 to 0.35 USD, the price of a bag of 50 kg of nuts varies from 70.00 to 122.30 USD. In Urban market, the price of a G. kola nut varies from 0.09 to 1.70 USD, and the price of a bag of 50 kg from 43.67 to 87.53 USD. The price of 100 g of bark or root from 0.87 to 1.75 USD, the price of a bag of 50 kg of bark or roots varies from 87.35 to 148.45 USD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Garcinia kola pricing in rural and urban market in the East region of Cameroon.

| Part sold | Measurement unit | Price in rural market (USD) | Price in urban market (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuts | Nuts | 0.04–0.09 | 0.09–0.17 |

| 1 kg | 1.74–6.11 | 4.37–5.24 | |

| 5 kg | 4.37–10.48 | 10.48–19.22 | |

| 10 kg | 12.23–29.70 | 26.20–43.67 | |

| 50 kg | 26.21–52.40 | 43.67–87.35 | |

| Bark and root | 0.5 kg | 0.17–0.35 | 0.87–1.75 |

| 1 kg | 4.37–8.73 | 5.24–10.48 | |

| 5 kg | 9.61–11.36 | 10.48–19.22 | |

| 10 kg | 26.21–34.94 | 34.94–52.41 | |

| 50 kg | 70.00–122.30 | 87.35–148.49 |

Exchange rate: USD ($) 1 = 572.41 FCFA.

Source: Field survey, 2021

3.2.5. Contribution of Garcinia kola to annual income of stakeholders

G. kola marketing contribute mostly to wholesalers and retailers incomes compared to other stakeholders. The marketing of G. kola contributes more that 80 % to the annual income of approximately 6 % of the wholesalers surveyed. To retailers, marketing of G. kola contributes to approximately 20–70 % of their annual income. It contributes between 5 and 50 % for all the collectors interviewed, with a contribution of less than 20 % of the annual income of the majority of collectors interviewed (31 %). In the locality of Belabo, the marketing of G. kola is very little benefit to locals traders, it contributes around 30 % to the annual income of around 3 % of locals traders interviewed. (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Contribution of Garcinia kola to the annual income of stakeholders.

3.2.6. Problems facing the of Garcinia kola value chain in Belabo

The results revealed that the most important problems that the G. kola value chain is facing are: attack of the product by weevil (24.26 % frequency of citation), lake of storage and deforestation (14.71 %), price fluctuation (13.24 %), poor access to market (11.76 %). The least important problems listed by the populations were seasonal fluctuation in production, diebacks and rots, and attack of the products by caterpillars (5.15 %; 3.68and 2.21 %, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Problems facing the G. kola in value chain in Belabo.

| Marketing problems | Number of citation | Frequency of citation (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Attack of product by weevil | 33 | 24.26 |

| Lake of storage facilities | 20 | 14.71 |

| Deforestation | 20 | 14.71 |

| Price fluctuation | 18 | 13.24 |

| Poor access to markets | 16 | 11.76 |

| No difficulty | 14 | 10.29 |

| Seasonal fluctuation in production (Supply of bitter cola is rare in the dry season) | 7 | 5.15 |

| Dieback and Rots | 5 | 3.68 |

| Attack of product by caterpillars | 3 | 2.21 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Products collected

In the G. kola value chain at Belabo, the products collected are nuts, bark and roots, which are either consumed, given to other community members or marketed, following the pattern of all natural resources with food and market values. In contrast to other NTFPs whose bark and roots are intended solely for auto-consumption, G. kola bark and roots are marketed in Belabo, as they are generally used to make local beverages. These results are contrary to those obtained by several authors who reported that in Nigeria and Ivory Coast, only the nuts are marketed by local populations [[38], [39], [40]]. This difference could be accounted for by cultural difference whereby the use of bark and roots is not known by the people of Nigeria and Ivory Coast. This means that G. kola is likely more valued by local populations in the East region of Cameroon than in these countries.

4.2. Harvesting, processing and storage

The process of collecting and preserving G. kola in Belabo is a laborious one as people walk long distances and go up to 30 km into the forest to harvest. This implies that G. kola is becoming scarce at the peripheries of the villages [41]. reported that in the village of Gribe in eastern Cameroon, people walk an average of 8 km to collect NTFPs, due to the scarcity of resources on the peripheries of villages. In Belabo, given the long distances trekked by collectors, men participate more in the harvesting of bark and roots as they are obliged to go deep into the forest to obtain supplies of these parts as they are harvested throughout the year. Similar observations had already been made by Ref. 42, who highlighted that both men and women collect NTFPs, although men undertake special long distance often referred to as harvesting trips while women collect opportunistically. Similarly [43], pointed out that the availability of natural resources in the forest varies according to space and time and thus affects people's spatial mobility in the forest. In Belabo, the bark is the second most traded part of G. kola highly prized in both national and international markets [17]. reported that 3 tonnes of G. kola bark and nuts were exported to Europe in 1998. However, the bark is not harvested and marketed in all G. kola production basins in Cameroon [44]. report that the exploitation of the bark remains almost not practiced in the central region of Cameroon. This is also the case in Nigeria and Ivory Coast where [[38], [39], [40]] reported that, only the nuts are marketed by local populations. The availability of G. kola nuts in Belabo is seasonal and varies according to fruiting periods, which go from February to March and from June to October, corresponding to the long dry season and the long rainy season. whereas, bark and roots are available all year round, contributing to the resource's scarcity, as populations debark and uproot G. kola stems throughout the year. In addition, the deeper they go into the forest, they collect the larger quantities. These observations are similar to those made by Ref. [45], who pointed out that harvesting distance influences harvesting capacity and species availability. The harvesting technique could also influence the quantity of resource harvested. The main harvesting technique for G. kola nuts in Belabo is handpicking. This technique is similar to that used by the populations of Central and Southern Cameroon, but different from that used by the populations of the Southwest of Cameroon. In fact, farmers from Southwest Cameroon preferred to harvest the fruits from the tree. This technique is more labour intensive than picking fallen fruits and ensures a higher and more stable yield by preventing the fruits from deteriorating or being stolen or eaten by wild animals when they fall [21].

The study revealed that post-harvest processing and storage techniques for the different G. kola parts were mainly local and manual. This very common for value chains of most NTFPs Similar observations were made by Ref. [46], who report that Ricinodendron heudelotii nuts are extracted manually. This manual extraction limits the quality of the nuts, the seeds extracted, and the possibilities for large-scale extraction and marketing. [47], reported that manual kernel extraction is time consuming efforts. A better collection process would guarantee better product quality and increase market value. Product storage techniques are rudimentary. and consisting of drying and bottling the nuts, or drying and storing in a humid environment, or drying and wrapping in plastics, bags, straws or banana leaves to prevent the products from drying up. These processing and storage techniques are similar to those identified by Ref. [38] who reported that fruits are processed by separating seeds from the pulp, air-drying them locally and preserving them for marketing locally. However, these techniques do not guarantee good product quality. Some authors have shown that the storage of kola nuts in baskets lined with fresh leaves at a high temperature and high humidity provokes the development of various parasitic fungi, especially the wet rots caused by Fusarium and Penicillium species [48,49]. Contrary to the observations made by Ref. [50], who reported the using powders as a preservative for G. kola nuts in Nigeria, in Belabo, thelocal population mentioned no use of powders. One of the special features of the post-harvesting and storage of G. kola bark and root in Belabo is their processing into powder. Once processed, the powder is stored in bottles with a shelf life ranging from one week to one year. The nuts are still sold unprocessed.

4.3. Stakeholders organization and marketing of Garcinia kola

The results of this study revealed that the main stakeholders involved in the G. kola value chain in Belabo (collectors, local traders, retailers and wholesalers) were not organized in associations, common initiative groups or cooperatives. This is a major limitation as it prevents the weaker stakeholders from obtaining maximum benefits from the commercialization of G. kola as far as price negotiations are concerned. Meanwhile, it has been proven that when producers are organized in groups, they negotiate better prices for their products alongside other benefits like access to technology for improved transformation and packaging of products [51]. In Belabo vilages, local traders buy their supplies from collectors in their villages or go from villages to village to buy the products and then sell them in the local market or at the Belabo market. Retailers generally installed in Belabo go to the villages and directly buy from collectors. Wholesalers from Bertoua town buy products from local traders at the Belabo market. This organization is similar to that of Irvingia gabonensis value chain described by Ref. [52], who identified four main actors in the marketing channel of the product. However, the value chain of G. kola in Belabo locality is less complex than the one described by Ref. [53], who noted that the NTFP value chain in the Gribe village in East Cameroon is very complex and involves several actors, including intermediaries mandated by the wholesalers, who barter for the purchase of products. Moreover [38], mentioned that in most cases, NTFP marketing involves intermediaries or mediators who traverse the interior rural areas looking for primary collectors from wild sources and then transport the product to urban markets. This is not the case with the G. kola value chain in Belabo locality which is less complex.

As in most natural resource marketing processes, in Belabo the selling price of the various G. kola organs is negotiated between the trader and the buyer, which does not allow a fixed price for the different organs marketed. [21], highlights that in Cameroon, data on the selling price of G. kola seeds differed significantly over regions and seasons and depended on individual collectors' practices, capacities, and preferences. Nuts are sold by the unit or in buckets corresponding to the kilogram, with the price per nut ranging from 0.4 to 1.70 USD, depending on whether you're in the rural or urban market, and also varying according to production season and nut size. [16], report that on the Cameroon market, a nut can cost between 0.04 and 0.13 USD, depending on its size. Bark and roots are generally sold in strips of piles corresponding to approximately 0.50 kg, with prices ranging from 0.17 to 1.75 USD, and the price per kilogram varying from 4.37 to 10.48 USD on rural and urban markets, respectively. According to Ref. [16], on the Cameroon market, bark is sold according to season, market and size, with prices ranging from 0.02 to 0.09 USD. Prices have risen in recent years, indicating that the resource is becoming increasingly popular worldwide, especially in Cameroon.

4.4. Contribution of Garciniakola commercialization to the livelihoods of local populations in eastern Cameroon

In the locality of Belabo, the marketing of G. kola products provides income to all the main stakeholders involved in the value chain. However, wholesalers and retailers benefit the most from the marketing of G. kola products with contributions to their annual income of over 35 % and 20 %, respectively. In comparison, the marketing of G. kola contributes less than 30 % and 15 % to the annual income of collectors and local traders, respectively. This contribution follows the normal trend in the income contribution of the commercialization of untransformed natural resources whereby the producers benefit less compared to those that are at the top of the value chain who benefit more. Although [45,53] assert that NTFPs are sources of income for several unemployed people in Central Africa, their commercialization less profitable to the collectors who are the primary actors in the value chain. this could be attributed to the weak structuring of the G. kola value chain and the low level of transformation of the product.

4.5. Problem facing the Garciniakola value chain

In Belabo locality, G. kola value chain faces several problems from its production to its marketing. In the decreasing order of importance, these problems are:the attack of product by weevils; lack of storage facilities, deforestation, price fluctuation, poor access to markets, seasonal fluctuation in production; dieback and rots. Some of these observations are similar to those made by Ref. [30], who reported that the constraints encountered by collectors and marketers in the commercialization of G. kola in Nigeria include rot and decay during storage (99 %), poor storage facilities (97 %), pests and diseases (88.2 %) and labour costs (68.2 %) and [54] among Bitter cola producers in Cameroon. The local population of Belabo also cited deforestation as a factor limiting the activity. Indeed, the locality is subject to extensive logging activity, particularly in the Belabo forest reserve and its peripheral zone, which considerably limits the production potential of the resource. This scarcity of natural resources is becoming increasingly apparent throughout Cameroon. According to Ref. [45], increasing pressure on forest resources deprived the local population of important sources of subsistence and income. Similar constraints were reported by Refs. [52,53,55] in the value chains of other NTFPs such as Irvingia gabonensis; Ricinodendron heudelotii; Gnetum spp.; Afrostyrax lepidophyllus; Scorodophloeus zenkeri; Beilschmiedia louisii; Baillonella toxisperma; Tetrapleura tetraptera; Panda oleosa and Piper guineense.

4.6. Perspectives for improving Garciniakola value chain for an increased contribution to the livelihoods of the stakeholders involved

The desired result in the extraction of a natural resource by the local population is always to provide for their livelihoods and secure a better human-wellbeing. This is not often the obtained result. From the results of this study, it is clear that the contribution of G. kola to the annual income of the main stakeholders is still very low due to the various problems facing its value chain as confirmed by Ref. [29]. However, there exist opportunities for value chain improvement and products valorisation. Firstly, organization of stakeholders is indispensable in value chain transformation processes for several reasons: it facilitates access to product transformation technology; it provides a good platform for price negotiation, it is favourable for capacity building and learning; and can easily secure markets. These opportunities, if applied, can step up the benefits from the commercialization of G. kola products for all main stakeholders involved and most especially the harvesters who benefit less than retailers and wholesalers by reducing their financial gap in often created by weak price negociation and poor access to the market. Secondly, a better structuring of the value chain is necessary as it reduces the loss along the value chain. These practical interventions for which policymakers need to consider will be contribute to the sustainable management of G. kola resource linked with the improvement of income generated by stakeholders involved in G. kola value chain [29].

5. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to analyse G. kola value chain and its contribution to the annual household revenue of local populations in Belabo, Cameroon., study found that the main actors involved in this value chain were collectors, local traders, retailers and wholesalers. The marketing of G. kola products is most profitable to retailers and wholesalers who are at the end of the value chain, whereas the collectors who are at the start of the chain benefit less. However, the contribution of G. kola to the income of annual income of stakeholders remains low in Belabo. All the stakeholders were not organized into associations. Although the G. kola value chain generates income for the various stakeholders in the sector, it is not well structured. The G. kola value chain in Belabo faces a number of problems, including: processing and storage techniques that vary from one stakeholder to another; the products collected are subject to various attacks by weevils, price fluctuations; and control mechanisms that vary from one stakeholder to another. Hence, the organization of the different stakeholder into association and a better structuring of the G. kola value chain in Belabo locality are the two main opportunities for improving the G. kola value chain with the potential of increase its contribution to the livelihoods of the different main stakeholders involved. In addition, policymakers should consider initiating innovations to boost production, support conservation, processing and price regulation to scale up economic and environmental benefits from G. kola.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Marlène Tounkam Ngansop: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Preasious Forbi Funwi: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mireil Carole Votio Tchoupou: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Jules Christian Zekeng: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Cédric Djomo Chimi: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Evariste Fedoung Fongnzossie: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Data availability statement

On request.

Additional information

Full collectors and traders questionnaires are availabel as supplemantary file.

Ethics and consent

The prior informed consent of the population surveyed was obtained in accordance with the guidelines for the application of the Nagoya protocol and more precisely, the newly adopted ABS law of Cameroon. In this case, we obtained verbal consent of the local authorities (local chiefs are the ones representing local communities) and those of the different participants. This was done by the principal investigator. We obtained this oral consent after having explained in detail the objectives of the survey, the procedures, the risks and the potential benefits. The participants had the opportunity to ask questions and to withdraw at any time they wanted.

We didn't consider people of ages lower than 21 years in the study as the majority of the youths below this age are still in the secondary school and early university and assumed not knowledgeable to provide the information researched. So we did not need any parental authorization.

Funding

This work was supported by the Rufford Foundation for funding this research (Grant agreement N° 32319-1).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Rufford Foundation, United kingdom for funding this research and the Millennium Ecologic Museum for their technical and scientific support during the study. We equally thank Dr. Sonwa Jean Denis; Dr. Takanori Oishi; Dr. Bezeng Bezeng Simeon for their contribution to the implementation of this research project. We also thank all the fieldworks guides, all the differents Chiefs and their populations for the warm welcome during the survey. We are also grateful to the Belabo Municipal Council for their logistical support and warm collaboration during the fieldwork. We further express our thanks to all those involved in fieldwork and data collection and community members of the different villages of Belabo.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39568.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Agyili J., Sacande M., Koffi E., Peprah T. Improving the collection and germination of West African Garcinia kola Heckel seeds. N. For. 2007;34:269–279. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yogom B.T., Avana-Tientcheu M.L., Mboujda M.F.M., Momo T.S., Fonkou T., Tsobeng A., Barnaud A., Duminil J. Ethnicity differences in uses and management practices of bitter kola trees (Garcinia kola) in Cameroon. Econ. Bot. 2020;74:429–444. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maňourová A., Polesný Z., Ruiz-Chután A., et al. Identification of plus trees for domestication: phenotypical description of Garcinia kola populations in Cameroon. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024;71:1893–1909. doi: 10.1007/s10722-023-01750-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tauchen J., Frankova A., Manourova A., Valterova I., Lojka B., Leuner O. Garcinia kola: a critical review on chemistry and pharmacology of an important West African medicinal plant. Phytochem Rev. 2023;22:1305–1351. doi: 10.1007/s11101-023-09869-w(0123456789. ,-volV(.)0123456789(.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanmegne G., Mbouobda H.D., Temfack B., Koffi E.K., Omokolo D.N. Impact of biochemical and morphological variations on germination traits in Garcinia kola heckel seeds collected from Cameroon. Res. J. Seed Sci. 2010;3:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yakubu F.B., Adejoh O.P., Ogunade J.O., Igboanugo A.B.I. Vegetative propagation of Garcinia kola (Heckel) World J. Agric. Sci. 2014;10:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tshibangu P.T., Kapepula P.M., Kapinga M.J.K., Lupona H.K., Ngombe N.K., Kalenda D.T., Jansen O., Wauters J.N., Tits M., Angenot L., et al. Fingerprinting and validation of a LC-DAD method for the analysis of biflavanones in Garcinia kola -based antimalarial improved traditional medicines. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016;128:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Indabawa I., Arzai A. Antibacterial activity of Garcinia kola and cola nitida seed extracts. Bayero J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2011;4:52–55. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ijomone O.M., Nwoha P.U., Olaibi O.K., Obi A.U., Alese M.O. Neuroprotective effects of kolaviron, a biflavonoid complex of Garcinia kola, on rats Hippocampus against methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2012;5:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwu M.M. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2014. Handbook of African Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oluwatosin A., Tolulope A., Ayokulehin K., Patricia O., Aderemi K., Catherine F., Olusegun A. Antimalarial potential of kolaviron, a biflavonoid from Garcinia kola seeds, against Plasmodium Berghei infection in Swiss Albino Mice. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014;7:97–104. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; [a] Kagbo H.D., Ejebe D.E. Phytochemistry and Preliminary toxicity studies of the methanol extract of the stem bark of Garcinia kola (Heckel) Internet J. Toxicol. 2010;7:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adesuyi A.O., Elumm I.K., Adaramola F.B., Nwokocha A.G.M. Nutritional and phytochemical screening of Garcinia kola. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012;4(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eleyinmi, Afolabi F., Bressler D.C., Amoo I.A., Sporns P., Oshodi A.A. Chemical composition of Bitter cola (Garcinia kola) seed and hulls. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2006;15/56(4):395–400. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adebisi A.A. 115_132. Center for International Forestry Research; 2004. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep02033.13 (Case Studies of Non-timber Forest Product Systems). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngansop T.M. Distribution and natural regeneration of Garcinia kola Heckel, a highly solicited vulnerable non timber forest product in the Belabo communal forest, eastern Cameroon. Final projet evaluation. Rufford Fundation. 2022;11p [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eyog M., Ndoye O., Kengue J., Awono A. IPGRI; 2006. Les fruitiers forestiers comestibles du Cameroun. CIFOR, Sub-Saharan Africa Forest Genetic Resources Programme (SAFORGEN) p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honoré Tabuna. 1999. Le Marché des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux de l'Afrique Centrale en France et en Belgique. ISSN 0854-9818 occasional paper no.19. 35pp. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ndoye O., Ruiz Perez M., Eyebe A. In: Les produits forestiers non-ligneux en Afrique Centrale. Sunderland T.C.H., Clarck L.E., Vantomme P., editors. Recherches actuelles et perspectives pour la conservation et le développement; Rome: 2000. L’influence de la commercialisation des produits forestiers non ligneux sur la dégradation des ressources en Afrique Centrale: le rôle de la recherche dans l’équilibre entre le bien-être des populations et la préservation des forêts; pp. 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awono A., Eba’a A.R., Foundjem T.D., Levang P. Vegetal non-timber forest products in Cameroon, contribution to the national economy. Int. For. Rev. 2016;18(S1):66–77. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingram V., Schure J. Yaounde. CIFOR/FORENET Project; 2010. Review of non timber forest products (NTFPs) in central Africa: Cameroon. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manourova A., Polesny Z., Lojka B., Degrande A., Pribyl O., Van Damme P., Verner V. Tracing the tradition: Regional differences in the Cultivation, utilization, and commercialization of bitter kola (Garcinia kola, clusiaceae) in Cameroon. Econ. Bot. 2023;XX(X):1–16. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallik M.R. Sustainable management of non-timber forest products in Orissa: some issues and options. Ind. in. of Agri. Econ. 2000;55(No.3):384–397. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lecup I. FAO; Rome: 2006. Using the Market Analysis and Development (MA&D) Approach as a Small-Enterprise Development Strategy for Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Natural Resource Management; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplinsky R., Morris M. vol. 144p. IDRC; 2000. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/42791981 (A Handbook for Value Chain Research). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akerele E.O., Akanni K.A., Oyebanjo O., E M., Agbaje M.E. Market structure analysis in local stimulants marketing among women in Osun state, Nigeria. AUDOE. 2023;19(2/2023):21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ingram V., Bongers G. Valuation of non-timber forest product chains in the Congo basin: a methodology for valuation. CIFOR. Yaounde, Cameroon, FAO-CIFOR-SNVWorld Agroforestry Center-COMIFAC. 2009:80. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dadebo A.M., Sarfo-Adu K.G., Somari S., Galley D. Forest resources value chain analyses: Alternative development pathways toward biodiversity conservation and sustainable forest management in Ghana. Sustainable Forest Management. 2024 doi: 10.5772/intechopen.1005049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eba'a Atyi R., Lescuyer G., Poufoun J.N., Fouda T.M. CIFOR Report; 2013. Étude de l'importance économique et sociale du secteur forestier et faunique au Cameroun; p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chimi D.C., Ngansop T.M., Zekeng J.C., Tchoupou V.C.M., Funwi P.F. Enhanced local governance as response to threats on vulnerable non-timber forest product species: case of Garcinia kola Heckel in East Cameroon. Environmental Development. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2024.100974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.PCDB Plan simple de gestion de la forêt communautaire de Belabo. Commune de Belabo. 2012:156. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Letouzey R. Institut de l’internationale de la végétation; Toulouse, France: 1985. Notice de la carte phytogéographique du Cameroun au 1:500000. Domaine de la forêt dense humide semi-caducifoliée; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- 32.CTFC . Centre Technique de la Forêt Communale; 2013. Commune de Belabo étude socio-économique dans le cadre de l’aménagement de la réserve forestière Belabo-Diang; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eeuwijk V.P., Angehrn Z. Swiss TPH - Fact Sheet Society, Culture and Health; 2017. How to … Conduct a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) : Methodological Manual; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingram V. Changing governance arrangements: NTFP value chains in the Congo Basin. Int. For. Rev. 2017;19(S1):152–169. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruslin Saepudin Mashuri S., Rasak M.S.A., Alhabsyi F., Syam H. Semi-structured interview: a methodological reflection on the development of a qualitative research instrument in educational studies. IOSR J. Res. Method Educ. 2022;12(1):22–29. doi: 10.9790/7388-1201052229. 2320-737x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplinsky R., Morris M. International Development research Center; Canada: 2000. A Handbook for Value Chain Research; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell D., Hanoomanjee S. vol. 49. Project Funded by the European Union; 2012. (Manual on Value Chain Analysis and Promotion). Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unaeze H.C., Oladele A.T., Agu L.O. Collection and marketing of bitter cola (Garcinia kola) in nkwerre local government area, Imo state, Nigeria. Egypt. J. Biol. 2013;15:37–43. doi: 10.4314/ejb.v15i1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olowoyo F.B., Samson E.O., Okpara I.G., Nwachukwu J.Q., Oyewusi E.O. Market performance and utilization of Garcinia kola (Heckel) (bitter kola) in Abia state, Nigeria. Niger. Agric. J. 2021;52(3):240–249. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kouame N.M., Ake C.B., Mangara A., Koffi N. Analyse de l ’ intérêt socio-économique des graines de Garcinia Kola Heckel (Clusiaceae) dans la commune de Koumassi (Abidjan), Côte d'Ivoire. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences. 2016;10(6):2587–2595. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ngansop T.M. Ecologie et régénération naturelle des espèces à Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux de la périphérie du Parc National de Boumba-bek, Sud-Est Cameroun. Thése de Doctorat PhD. Botanique-Ecologie, Université de Yaoundé I. 2020:150. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schreckenberg K. University of London; 1996. Forests, Fields and Markets: a Study of Indigenous Tree Products in the Woody Savannas of the Bassila Region, Benin. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bahuchet S. Berg Publ; (NY, Oxford): 1991. Spatial Mobility and Access to Resources Among the African Pygmies; pp. 205–255. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamga Y.B., Nguetsop V.F., Anoumaa M., Kanmegne G., Momo M.C. Garcinia kola (Guttiferae) in tropical rain forests: exploitation, income generation and traditional uses, in the East and Central regions of Cameroon. Journal of Pharmaceutical, Chemical and Biological Sciences. 2019;7:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ketchatang T.P., Zapfack L., Louis-Paul-Roger Kabelong B.L.-P.-R., Endamana D. Disponibilité des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux fondamentaux à la périphérie du Parc national de Lobeke. Vertigo. 2015 doi: 10.4000/vertigo.18770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ndumbe N.L., Ingram V., Tchamba M., Nya S. From trees to money: the contribution of njansang (Ricinodendron heudelotii) products to value chain stakeholders' financial assets in the South West Region of Cameroon. Forest Trees and Livelihoods. 2018;17p doi: 10.1080/14728028.2018.1559107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mbosso C., Degrande A., Tabougue P., Franzel S., Mein V.N., Van Damme P., Tchoundjeu Z., Foundjem-Tita D. No appropriate technology so far for Ricinodendron heudelotii (Baill. Pierre ex Pax) processing in Cameroon: performance of mechanized kernel extraction. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013;8(46):5741–5751. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oludemokun A.A. 1979. A Review of Cola Diseases; pp. 265–269. Pans25. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Opeke L.K. Spectrum Books, Ibadan; 1992. Tropical Tree Crops; p. 327. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babalola F.D., Agbeja B.O. Marketing and distribution of Garcinia kola (Bitter kola) in southwest Nigeria: opportunity for development of a biological product. Egypt. J. Biol. 2010;12:12–17. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 51.MINFOF . Capitalisation des résultats et approche de gestion dans le cadre du programme d’appui à la mise en œuvre de la stratégie de développement du secteur rural volets forêt-environnement de 2010 à 2019. Rapport d’étude GIZ/ProPFE; 2019. Valorisation des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux au Cameroun; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ingram V. vol. 31p. Centre for International Forestry Research; 2009. (Governing Forest Commons in the Congo Basin: Non-timber Forest Product Value Chains). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ngansop T.M., Sonwa J.D., Fongnzossie F.E., Biyé E.H., Forbi P.F., Takanori O., Nkogmeneck B.-A.†. ASC-TUFS Working Papers. Kyoto University; Japan: 2019. Identification of main Non-Timber Forest Products and related stakeholders in its value chain in the Gribe village of southeastern Cameroon; pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mbanoso M. Idzi; Sussex: 2008. Research Finding for Development Policy Makers and Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caspa G.R., Tchouamo R.I., Mate Mweru J.-P., Amang M.J. Marketing Ricinodendron heudelotii kernels and Gnetum spp. leaves around Lobeke national Park, East Cameroon. Tropicultura. 2018;36(3):565–577. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

On request.