Abstract

The incidence of patients diagnosed with either breast cancer (BC) or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is increasing each year. IBD has been shown to be strongly associated with the development of a variety of solid tumors, but the relationship with breast cancer is not yet definitive. We explored the causative relationship between IBD and BC using a Mendelian randomization (MR) strategy. MR-Egger regression, weighted median (WM), simple median (SM), maximum likelihood (ML), and inverse variance weighting (IVW) methods were among the analytical techniques used in this work. The examination of heterogeneity was conducted by the use of Cochran's Q test and Rucker's Q test. The sensitivity analysis in this study used the IVW and MR-Egger methodologies. The results of our investigation suggested that IBD had a beneficial impact on estrogen receptor-negative (ER-) breast cancer (odds ratio (OR) = 0.92, P = 0.02). The study did not find a significant association between IBD and the risk of developing overall breast cancer (OR = 0.99, P = 0.60), as well as estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer (OR = 1.02, P = 0.60) specifically. In addition, our study findings indicated that there was a detrimental association between ER+ breast cancer and IBD as determined using reverse MR analysis (OR = 1.07, P = 0.04). Furthermore, this analysis failed to observe any significant association between overall breast cancer (OR = 1.07, P = 0.07) or ER- breast cancer (OR = 0.99, P = 0.89) and IBD. Our bidirectional MR study yielded a correlation between IBD and some specific hormone receptor status of BC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-024-01514-y.

Keywords: breast cancer, Inflammatory bowel disease, Mendelian randomization, Estrogen receptor, Genetics

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) has emerged as the predominant form of cancer globally and represents the malignancy with the greatest occurrence among women. It constituted about 25% of all malignancies diagnosed in women and contributed to 15% of cancer-related fatalities in the female population. The annual incidence of new breast cancer cases exceeded one million [1, 2]. The global incidence of breast cancer in 2020 reached approximately 2.3 million new cases, leading to an estimated 685,000 fatalities. Furthermore, it is anticipated that the number of breast cancer cases would escalate to 4.4 million by the year 2070 [3], constituting a major danger to women's physical and emotional health. The complete elucidation of the pathogenesis of breast cancer remained elusive. Breast cancer resulted from the combination of several components under certain circumstances. These factors consist of reproduction [4], densification of the mammary [5], lifestyle [6], nutrition, obesity [7, 8], hormonal medication [9], and family history [10].

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a complex and chronic autoimmune condition that has a prevalence rate of around 0.5% in the general population [11], and is becoming more common in newly industrialized countries [12], with a chronic course and a prolonged duration. IBD has two main subtypes, namely Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [13], both of which entail gastrointestinal lesions, reducing patients' quality of life and increasing mortality and economic burden [14, 15]. The exact cause of IBD remains unknown, since it is believed to be influenced by a combination of genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and the composition of the gut microbiota [16, 17]. Patients diagnosed with IBD have been shown in studies to be strongly associated with the development of a variety of malignant tumors such as colorectal cancer, small bowel cancer, intestinal lymphoma and cholangiocarcinoma [18–20], which may be due not only to the presence of chronic inflammation, but also to the use of a variety of medications (e.g., immunosuppressants or biologics) as part of the treatment regimen [21]. No discernible effect of IBD on the risk of breast cancer was found in a meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies, regardless of the type of IBD or the location [22]. Based on a population-based study conducted in Canada, there was observed variation in the association between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and the risk of breast cancer across different provinces. Specifically, the province of Ontario did not exhibit a significant correlation between these two conditions [23], However, in Alberta, patients with IBD displayed a slightly reduced risk of developing breast cancer compared to other types of extraintestinal cancers [24]. The causal relationship between IBD and breast cancer may be related to the estrogen receptor, the protective effect of estrogen on colon physiology, and the fact that low estrogen levels are a susceptibility factor for colonic inflammation [25–28]. It has also been suggested that IBD-induced changes in the gut microbiome are associated with the development of breast cancer [29]. The possible association between IBD and breast cancer is a subject of continuing scholarly discourse and remains unclear.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a genetic variation-based approach of causal inference [30]. The research premise of MR is based on Mendel's laws, which utilize the influence of randomly assigned genotypes on phenotype in nature to infer the effect of biological variables on illness. Comparable to a randomized controlled experiment (RCT), but with lower expensive [31]. In Mendelian randomization, we analyze genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to find single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) that are associated with biological factors, which are called “instrumental variables (IVs)”. These instrumental variables are then used to infer the influence of biological factors on disease. Because genes are randomly assigned and not subject to confounding factors, the use of genetic variants to study causation avoids the influence of confounding factors on the outcome and improves the reliability of causal inferences [32].

This study aims to investigate the potential relationship and interactions between BC and IBD, providing a scientific basis for the correlation between the two diseases, as well as informing and guiding the development of new medicines and public health decision-making.

Method

Study design

The present work used a two-sample MR methodology, using summary statistics derived from a Genome-wide association study (GWAS), to examine the potential causative relationship between BC and IBD. In this research, the first hypothesis posited that IBD served as the primary exposure variable. The IVs were chosen based on their substantial connections with IBD among single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The variable of outcome in this study was breast cancer. In order to investigate the causal relationship between the exposure and outcome variables, we used two-sample MR studies. The assessment of the findings' reliability was conducted by means of sensitivity analysis. Subsequently, breast cancer was used as an exposure component, with IBD being utilized as the outcome variable. The reverse two-sample MR analytical technique was used to examine the existence of bidirectional causation. The current inquiry did not need ethical clearance. However, it is important to acknowledge that ethical authorization and informed consent were obtained for all original studies used in this research.

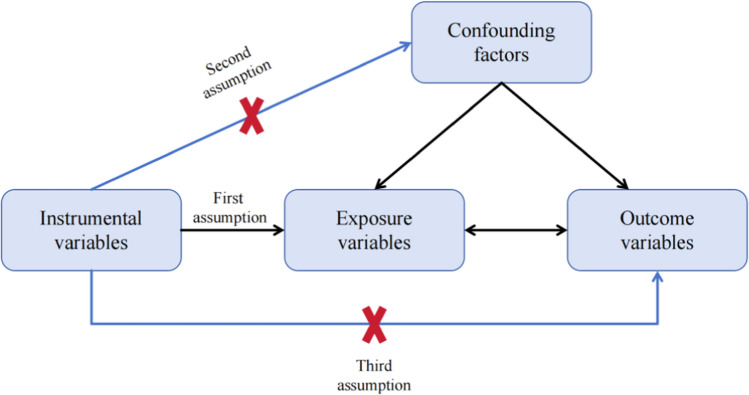

MR studies must adhere to three fundamental assumptions: Firstly, the premise of association requires that SNPs have a significant linkage to the exposure factor. Secondly, SNPs are not associated with other confounding variables that may affect the outcome variable, therefore satisfying the principle of independence. Lastly, the exclusive assumption asserts that SNPs must independently impact the outcome variable solely through the exposure component, eliminating the possibility of any alternative pathways (Fig. 1) [33].

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram for Mendelian randomization

Data sources

The GWAS datasets for both IBD and breast cancer were obtained from the https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/ website of the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit (MRCIEU). The SNPs associated with the inquiry code finn-b-K11_IBD have been obtained from the FinnGen biobank (https://www.finngen.fi/en). The database contained in total of 16,380,466 SNPs and had a comprehensive collection of 218,792 samples, of which 5673 were cases and 213,119 were controls. The Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) provided the breast cancer data, which encompassed overall BC (inquiry code: ieu-a-1129), positive estrogen receptor (ER+) BC (inquiry code: ieu-a-1132), and negative estrogen receptor (ER−) BC (inquiry code: ieu-a-1135) [34]. 10,680,257 SNPs and 106,776 samples made up the overall breast cancer dataset, and there were 61,282 cases in the case group and 45,494 controls. In the meanwhile, 10,680,257 SNPs and 83,691 samples in total were examined in connection to ER+ breast cancer, there were 38,197 cases and 45,494 controls. In addition, 55,149 samples and 10,680,257 SNPs were examined in connection to ER- breast cancer, there were 9655 cases and 45,494 controls. All of the data pertains to the population of Europeans.

Instrumental variable extraction

The criteria used for the screening of SNPs were as follows: (1) SNPs exhibiting statistically significant relationships with exposure variables were identified using a criterion of P < 5 × 10–8. (2) In order to address potential correlations among SNPs and minimize the impact of chain imbalance, the parameters were configured with a threshold of r2 < 0.001 and a distance of kb = 10,000. (3) The F-statistic was generated using the formula F = (R2/(1 − R2) × (n − k − 1)/k), where n denotes the sample size, k denotes the number of instrumental variables used, and R2 reflects the extent to which instrumental variables explain exposure. R2 is determined by the equation R2 = 2 × EAF × (1 − EAF) × β2, EAF is the minimum allele frequency and β is the allele effect value. SNPs with F values less than 10 were excluded due to their weak strength as IVs [35, 36]. Furthermore, a thorough examination was undertaken using the PhenoScanner website (http://www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk/) to ascertain the associations between IVs and other variables in the present research. In the event that an association was seen between SNPs and the outcomes, these SNPs were subsequently removed from the MR research.

Given that the SNPs pertaining to the variable of BC outcome were sourced from the same institutional research, we acquired a total of 12 same SNPs as the final selection. In a similar vein, we acquired a total of 59 (overall breast cancer), 57 (ER+ breast cancer), and 12 (ER- breast cancer) SNPs for the variable pertaining to IBD outcome. The main data are presented in Supplementary tables 1–6.

Observational indicators

This research investigates the reciprocal relationship between IBD and BC, encompassing both the general incidence of breast cancer and its specific subtypes, such as ER + and ER− breast cancer. Furthermore, sensitivity studies are performed in order to ascertain the robustness and replicability of the results.

Statistical analysis

The random-effects inverse-variance weighted (IVW) approach was the major technique adopted for data analysis. The tool was used to analyze the data related to exposure and outcomes within the framework of heterogeneity. In contrast, the fixed-effects IVW method was used in cases when heterogeneity was not present. Supplementary analysis included the use of weighted median (WM), simple median (SM), maximum likelihood (ML), and MR-Egger regression methodologies. The presence of heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran's Q and Rucker's Q test methodologies. The use of funnel plots facilitated the inference of the presence or absence of heterogeneity in a subtle manner. The observation of a symmetrical distribution of scattered dots in the funnel plots allowed us to deduce the absence of heterogeneity, particularly when P > 0.05. In order to provide more clarification on the association between exposure and outcome, scatter plots were used. Furthermore, the leave-one-out approach was employed to evaluate the influence of individual SNPs and determine the combined impacts of the remaining SNPs.

Result

The impact of IBD on breast cancer

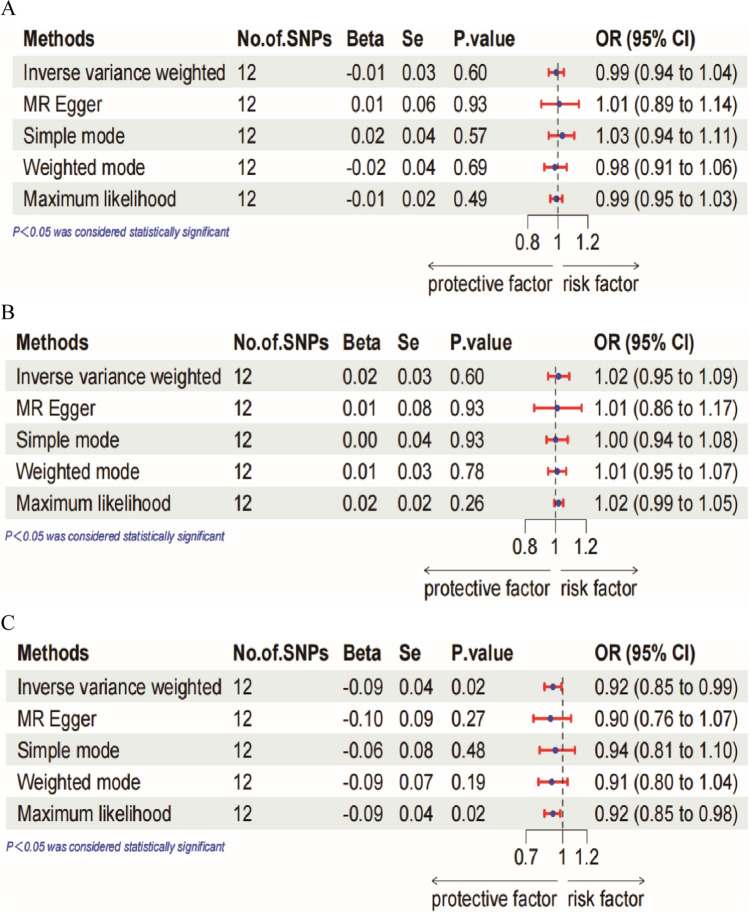

The random-effects IVW analysis did not find any evidence of a genetic causal relationship between IBD and overall breast cancer, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.99 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.94–1.04, P = 0.60). Similarly, no genetic causality was observed for IBD and ER+ breast cancer (OR = 1.02, 95%CI 0.95–1.09, P = 0.60). The results of the other four analyses (MR-Egger, WM, SM and ML) were consistent with the random-effects IVW analysis. However, there was an inverse correlation seen between IBD and the incidence of ER− breast cancer (OR = 0.92, 95%CI 0.85–0.99, P = 0.02). This suggests that those with IBD had a decreased likelihood of developing ER- breast cancer. Figure 2 displays a forest plot illustrating the MR study conducted to investigate the causal impact of IBD on overall breast cancer, as well as its subtypes, namely ER+ and ER− breast cancer. The maximum likelihood method also showed a negative association between IBD and ER− breast cancer incidence.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of MR analysis of the causal effect of IBD on (A) overall breast cancer. B ER+ breast cancer. C ER− breast cancer

In addition, a sensitivity analysis was performed to verify the accuracy of the findings. The scatterplot revealed a negative association between IBD and ER- breast cancer, but no significant connection was seen between overall breast cancer and ER+ breast cancer. Heterogeneity was seen in the Rucker's Q test (Q = 18.65, P = 0.045) pertaining to total breast cancer, but no heterogeneity was detected in the Cochran's Q test (Q = 18.85, P = 0.06). The findings of this study indicate the presence of potential variations between the exposures and outcomes under investigation. Consequently, we choose to use the random-effects IVW approach for the two-sample MR analysis. The intercept test conducted using MR-Egger indicated the absence of horizontal pleiotropy (P > 0.05) in the MR analysis of IBD in relation to breast cancer. Additionally, the leave-one-out test analysis demonstrated that individual SNP did not have a significant impact on the findings (see Supplementary Fig. S1–3). In terms of ER+ breast cancer, it was shown that both Rucker's Q test (Q = 22.75, P = 0.01) and Cochran's Q test (Q = 23.19, P = 0.02) indicated the existence of heterogeneity, whereas no statistically significant evidence of horizontal pleiotropy was observed. In the context of ER- breast cancer, it was shown that both Rucker's Q test (Q = 10.93, P = 0.363) and Cochran's Q test (Q = 10.97, P = 0.446) did not indicate the existence of substantial heterogeneity. Furthermore, the MR-Egger intercept test (P > 0.05) did not provide any evidence of horizontal pleiotropy. Table 1 presents the results of a MR sensitivity analysis that examines the causal impact of IBD on breast cancer across various estrogen receptor statuses. The leave-one-out test was conducted to exclude single SNPs in a sequential manner. Following this, the IVW analysis was performed on the remaining SNPs. The results of the IVW analysis were found to be identical to the original results, indicating that the findings of this Mendelian randomization study were robust. In order to enhance the robustness of the aforementioned results, funnel plots are used to visually depict the degree of heterogeneity across the datasets (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, the scatter plots offer a visual depiction of the correlation between data sets in the MR analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Table 1.

MR sensitivity analysis of the causal effect of inflammatory bowel disease on breast cancer in different estrogen receptor states

| Heterogeneity | Pleiotropy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rucker’s Q tes | Cochran’s Q test | MR-Egger | ||||

| Q test | P value | Q test | P value | Intercept | P value | |

| Overall | 18.65 | 0.045 | 18.86 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.74 |

| ER+ | 22.75 | 0.01 | 23.19 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.67 |

| ER− | 10.93 | 0.36 | 10.97 | 0.46 | 0.01 | 0.85 |

The relationship of BC on IBD

The findings obtained from the random-effects IVW indicated that there was no evidence of a genetic causal relationship between overall breast cancer (OR = 1.07, 95%CI 0.99–1.15, P = 0.07) and ER− breast cancer (OR = 0.99, 95%CI 0.92–1.08, P = 0.89) and IBD. Nevertheless, there was a significant positive correlation between ER + breast cancer and the occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease (OR = 1.07, 95%CI 1.00–1.14, P = 0.04). Figure 3 displays a forest plot illustrating the results of a MR study investigating the causal impact of total breast cancer, ER+ breast cancer, and ER- breast cancer on IBD. The findings obtained from the ML approach to analysis consistently align with those obtained from the IVW technique of analysis, indicating that individuals diagnosed with ER+ breast cancer may exhibit a heightened vulnerability to IBD.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of MR analysis of the causal effect of (A) overall breast cancer. B ER+ breast cancer. C ER− breast cancer on IBD

Rucker's Q test (Q = 80.29, P = 0.02) and Cochran's Q test (Q = 80.49, P = 0.03) suggested the presence of heterogeneity in overall breast cancer. Nevertheless, the datasets pertaining to both IBD and ER+ breast cancer, as well as IBD and ER− breast cancer, shown a lack of heterogeneity (all P > 0.05) (Table 2). The MR-Egger intercept test could not detect any evidence of horizontal pleiotropy in any of the three datasets (Table 2). Leave-one-out test analyses indicate that the presence of a single SNP may have a serious impact on causality estimates (Supplementary Figs. 5–7). Funnel plots are used to visually depict the degree of heterogeneity across the datasets (Supplementary Fig. 1), and scatter plots can visualize the relationship between exposures and endings (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Table 2.

MR sensitivity analysis of the causal effect of breast cancer in different estrogen receptor states on inflammatory bowel disease

| Heterogeneity | Pleiotropy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rucker's Q test | Cochran's Q test | MR-Egger | ||||

| Q test | P value | Q test | P value | Intercept | P value | |

| Overall | 80.29 | 0.02 | 80.49 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| ER+ | 67.65 | 0.12 | 67.72 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.82 |

| ER− | 6.08 | 0.81 | 6.09 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.96 |

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the bidirectional relationship between breast cancer and IBD through a genetic analysis using bidirectional two-sample MR. The findings revealed that individuals with a genetic predisposition to IBD had a decreased likelihood of developing ER- breast cancer. However, no significant associations were observed between genetic susceptibility to IBD and the risk of overall breast cancer or ER+ breast cancer. Conversely, individuals with a genetic predisposition to ER+ breast cancer exhibited an increased risk of developing IBD. Notably, no significant correlations were found between genetic susceptibility to overall breast cancer or ER− breast cancer and the risk of developing IBD. The potential association between breast cancer and IBD remains unclear, since the existing body of research on this topic is limited in both national and international contexts. Multiple studies have provided data suggesting a correlation between autoimmune illnesses, including systemic lupus erythematosus [37, 38] and rheumatoid arthritis [39], and a decreased susceptibility to breast cancer. The current research also provided genetic evidence supporting a causal relationship between IBD and breast cancer, particularly ER− breast cancer. Furthermore, the study revealed that IBD is associated with a decreased occurrence of ER- breast cancer. One of the postulated rationales for this phenomenon is the potential occurrence of delayed onset of menarche and premature menopause in individuals with IBD compared to those without the condition. Consequently, it is plausible that women with IBD may have a comparatively abbreviated duration of estrogen exposure throughout their lifespan [40, 41]. Breast cancer often arises from a complex interplay of several pathogenic variables. Further exploration might be conducted in the future to identify possible shared characteristics of autoimmune illnesses that may mitigate the risk of developing breast cancer.

One longitudinal research conducted in Norway examined the patient population with IBD over a span of 20 years, with the aim of investigating the occurrence of malignant neoplasms. The findings of this study revealed a heightened susceptibility to breast cancer among those diagnosed with IBD [42]. Due to the intricate nature of breast cancer as a disease, the involvement of gene-environment interactions in its development is of paramount importance. However, the precise processes behind these observations have yet to be fully elucidated. There is speculation that the observed phenomenon might be attributed to the down-regulation of Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) levels in individuals diagnosed with IBD. BCRP serves as an efflux transporter that plays a protective role in intestinal cells by preventing the accumulation of harmful chemicals. In a study conducted by Gutmann et al. it was shown that the levels of BCRP were notably reduced in individuals who had just been diagnosed with drug-naive IBD in comparison to a control group without IBD [43]. Similar observations were found in individuals who exhibited unresponsiveness to 5-ASA or prednisolone therapy, indicating that the reduction in BCRP levels may be attributed to the inflammatory process, potentially implicating its involvement in the etiology of breast cancer [44]. Another hypothesis posits that oxidative stress is a significant factor in the development of IBD and breast cancer [45]. This suggests that there may be shared pathological mechanisms involving the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant activity in both diseases. Specifically, research has demonstrated the inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase, an endogenous antioxidant enzyme, in individuals with IBD, which has also been linked to an increased susceptibility to breast cancer [46]. The current research had an extensive duration of follow-up, but with a limited patient cohort. The median age at the time of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) diagnosis was seen to be 38 and 29 years, respectively. Furthermore, even after a span of 20 years, the patients remained relatively youthful, leading to a diminished occurrence of cancer and findings that may not be fully typical. This research observed a decrease in the occurrence of ER+ breast cancer at the genetic level in individuals with IBD. The use of a substantial sample size effectively controlled for the potential confounding influence of subsequent medication treatment, which might impact cancer development.

A scholarly cohort study conducted in Taiwan, China, on an Asian population revealed that there was no significant association between IBD and an elevated risk of breast cancer. However, the study did find a strong correlation between the frequency of hospitalizations related to IBD and the risk of developing breast cancer. Specifically, patients with IBD who required more than two hospitalizations per year were approximately ten times more likely to develop breast cancer [47]. While this study offers a unique perspective on the association between breast cancer and IBD, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. Specifically, it was observed that patients with IBD exhibited a higher prevalence of risk factors for breast cancer, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and obesity [48]. Additionally, the study did not provide any information regarding potential confounding factors that may have influenced the results. Hence, it is inconclusive to ascertain whether IBD has an impact on the occurrence of breast cancer via the aforementioned potential risk factors. The current study does not present any contradictory evidence, and the selection of independent variables pertaining to IBD effectively eliminates confounding factors that could be linked to breast cancer, thereby enhancing the credibility of the findings.

A similar finding was obtained via the examination of 16 cohort studies in a subsequent meta-analysis: the collective OR for IBD was determined to be 0.94 (95% CI 0.82–1.06), indicating no statistically significant correlation with breast cancer. In further subgroup analyses, it was shown that patients diagnosed with CD and UC did not exhibit a statistically significant association with the risk of developing breast cancer. Furthermore, the risk of breast cancer among individuals with IBD did not demonstrate significant variation across different geographical locations. These findings imply that IBD does not have a substantial impact on the risk of developing breast cancer [22]. The findings of the current research also align to some extent with the aforementioned results, since no statistically significant correlation was seen between the occurrence of breast cancer and IBD. This further supports the credibility and validity of the study's outcomes. This research aims to further investigate the effects of IBD on a specific subset of breast cancer. Hence, it is essential to acknowledge the significance of considering the risk of breast cancer in the management of female patients diagnosed with IBD. Furthermore, there is a need for further investigation via clinical and fundamental research to explore the possible pathophysiologic connection between breast cancer and IBD. The findings of these research have the potential to facilitate the identification of people with a heightened susceptibility to breast cancer, hence enabling targeted implementation of breast cancer screening interventions for maximum benefit.

Anecdotal evidence from physicians treating IBD has long suggested that female with CD tend to have more severe clinical symptoms and disability than their male counterparts, and that the prevalence of UC is higher among male patients [49]. Although estrogen has anti-inflammatory properties, it can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the gut, promote wound healing and improve the barrier function of the intestinal epithelium [28]. However, there are many studies that consider higher levels of estrogen a deleterious factor in IBD [50], and population-based studies in most Western groups have shown that women are at higher risk of developing IBD compared to men [51]. One of the most common problems is the oral contraceptive pill (OCP), where women exposed to OCP have a higher risk of both CD and UC than women not exposed to OCP [52, 53]. The effect of elevated estrogen levels on the development of IBD is further reinforced by the finding in a Danish cohort study that women with endometriosis also had an increased risk of developing IBD compared to women without endometriosis [54]. This is consistent with our findings that individuals with a genetic susceptibility to ER+ breast cancer have an increased risk of developing IBD, considering that it may be associated with higher estrogen levels.

The management of individuals with IBD who have a history of malignancy presents significant complexities. Oncologists often advise against the use of immunosuppressive medications due to the potential for cancer recurrence or the emergence of new malignancies during their administration. Conversely, insufficient management of IBD has the potential to heighten the likelihood of recurring flare-ups, diminished quality of life, progressive gastrointestinal damage, and disability [55]. The present research used reverse MR analysis to investigate the association between IBD and different subtypes of breast cancer. The findings revealed a heightened risk of IBD among patients with ER+ breast cancer. However, no significant causal link between IBD and overall breast cancer or ER- breast cancer was seen. This resource serves as a valuable guide for clinicians in formulating diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for patients presenting with various subtypes of breast cancer. It underscores the importance of assessing the efficacy of oncological interventions while also highlighting the significance of tailoring treatment plans for individuals with ER+ breast cancer who have a prior history of IBD or a familial predisposition to IBD. Specifically, it advises a cautious approach towards medications known to elicit pronounced gastrointestinal reactions in this patient population, while placing emphasis on monitoring and promptly identifying potential instances of newly-developed IBD during the course of treatment.

The study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the genetic data included in the current investigation were only extracted from populations of European descent. It is important to recognize that different geographic regions and races may introduce variations in causal relationships, and therefore, the findings of this study may not be fully generalizable to non-European populations. Secondly, Breast cancer GWAS has been performed only in female population, whereas IBD GWAS includes both females and males. This study did not conduct a gender-specific analysis to explore potential differences, which can represent a confounding factor and affect the results of the analyses. Thirdly, the availability of detailed data on disease severity, as well as specific markers such as HER2 and Ki67, was limited due to constraints in the utilized database.

Conclusion

This research provides evidence for a reciprocal causal association between breast cancer and IBD, whereby IBD is shown to reduce the likelihood of developing estrogen ER- breast cancer, whereas ER+ breast cancer is associated with an increased chance of developing IBD. Additional study is required to have a more thorough comprehension of the interaction between IBD and BC, as well as to explore the association between autoimmune illnesses and the outcomes of BC. The identification of pathways implicated in the susceptibility to BC among individuals with autoimmune disorders has potential for enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy and the development of novel pharmaceutical agents.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

The authors, YL, XM, and SW, developed and formulated the framework for this research work. Writing the text and evaluating its quality were done by XM and SW. The statistical analysis was done by XM and SW. SW contributes equally to XM. The paper was revised with help from XZ, KD, and CY. The final draft was updated by CY and SG. All authors worked together to create the essay, and they all afterwards evaluated and approved the final draft.

Funding

Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province, No. H2023206441 and Beijing-tianjin-hebei Basic Research Cooperation project, No. J230016 provided financing for the research done for this paper.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xindi Ma and Shang Wu are co-first authors since they contributed equally to this research.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Rose F, Meduri B, De Santis MC, Ferro A, Marino L, Colciago RR, Gregucci F, Vanoni V, Apolone G, Di Cosimo S, Delaloge S, Cortes J, Curigliano G. Rethinking breast cancer follow-up based on individual risk and recurrence management. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;109: 102434. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei S, Zheng R, Zhang S, Wang S, Chen R, Sun K, Zeng H, Zhou J, Wei W. Global patterns of breast cancer incidence and mortality: a population-based cancer registry data analysis from 2000 to 2020. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41(11):1183–94. 10.1002/cac2.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dierssen-Sotos T, Palazuelos-Calderón C, Jiménez-Moleón JJ, Aragonés N, Altzibar JM, Castaño-Vinyals G, Martín-Sanchez V, Gómez-Acebo I, Guevara M, Tardón A, Pérez-Gómez B, Amiano P, Moreno V, Molina AJ, Alonso-Molero J, Moreno-Iribas C, Kogevinas M, Pollán M, Llorca J. Reproductive risk factors in breast cancer and genetic hormonal pathways: a gene-environment interaction in the MCC-Spain project. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):280. 10.1186/s12885-018-4182-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nazari SS, Mukherjee P. An overview of mammographic density and its association with breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2018;25(3):259–67. 10.1007/s12282-018-0857-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashemi SH, Karimi S, Mahboobi H. Lifestyle changes for prevention of breast cancer. Electron Phys. 2014;6(3):894–905. 10.14661/2014.894-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LubiánLópez DM, ButrónHinojo CA, Castillo Lara M, Sánchez-Prieto M, Sánchez-Borrego R, Mendoza Ladrón de Guevara N, González Mesa E. Relationship of breast volume, obesity and central obesity with different prognostic factors of breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1872. 10.1038/s41598-021-81436-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amadou A, Torres Mejia G, Fagherazzi G, Ortega C, Angeles-Llerenas A, Chajes V, Biessy C, Sighoko D, Hainaut P, Romieu I. Anthropometry, silhouette trajectory, and risk of breast cancer in Mexican women. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3 Suppl 1):S52-64. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heikkinen S, Koskenvuo M, Malila N, Sarkeala T, Pukkala E, Pitkäniemi J. Use of exogenous hormones and the risk of breast cancer: results from self-reported survey data with validity assessment. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(2):249–58. 10.1007/s10552-015-0702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Martinez L, Zhang Y, Nakata Y, Chan HL, Morey L. Epigenetic mechanisms in breast cancer therapy and resistance. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1786. 10.1038/s41467-021-22024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrero-Castillo S, Baertling F, Kownatzki D, Wessels HJ, Arnold S, Brandt U, Nijtmans L. The assembly pathway of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I. Cell Metab. 2017;25(1):128–39. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Tawil AM. Epidemiology and inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(10):1505–7. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i10.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kucharzik T, Ellul P, Greuter T, Rahier JF, Verstockt B, Abreu C, Albuquerque A, Allocca M, Esteve M, Farraye FA, Gordon H, Karmiris K, Kopylov U, Kirchgesner J, MacMahon E, Magro F, Maaser C, de Ridder L, Taxonera C, Toruner M, Tremblay L, Scharl M, Viget N, Zabana Y, Vavricka S. ECCO guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and management of infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(6):879–913. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roda G, Chien Ng S, Kotze PG, Argollo M, Panaccione R, Spinelli A, Kaser A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Crohn’s disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):22. 10.1038/s41572-020-0156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi T, Siegmund B, Le Berre C, Wei SC, Ferrante M, Shen B, Bernstein CN, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Hibi T. Ulcerative colitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):74. 10.1038/s41572-020-0205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ananthakrishnan AN, Bernstein CN, Iliopoulos D, Macpherson A, Neurath MF, Ali RAR, Vavricka SR, Fiocchi C. Environmental triggers in IBD: a review of progress and evidence. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1):39–49. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos GP, Papadakis KA. Mechanisms of disease: inflammatory bowel diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):155–65. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murthy SK, Kuenzig ME, Windsor JW, Matthews P, Tandon P, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, Coward S, Jones JL, Kaplan GG, Lee K, Targownik LE, Peña-Sánchez JN, Rohatinsky N, Ghandeharian S, Meka S, Chis RS, Gupta S, Cheah E, Davis T, Weinstein J, Im JHB, Goddard Q, Gorospe J, Loschiavo J, McQuaid K, D’Addario J, Silver K, Oppenheim R, Singh H. The 2023 impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: cancer and IBD. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2023;6(Suppl 2):S83-s96. 10.1093/jcag/gwad006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutgens MW, van Oijen MG, van der Heijden GJ, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B. Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: an updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(4):789–99. 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828029c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laredo V, García-Mateo S, Martínez-Domínguez SJ, López de la Cruz J, Gargallo-Puyuelo CJ, Gomollón F. Risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases and keys for patient management. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(3):871. 10.3390/cancers15030871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LoConte NK, Gershenwald JE, Thomson CA, Crane TE, Harmon GE, Rechis R. Lifestyle modifications and policy implications for primary and secondary cancer prevention: diet, exercise, sun safety, and alcohol reduction. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:88–100. 10.1200/edbk_200093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gong C, Xu R, Zou P, Zhang Y, Wang X. Inflammatory bowel disease and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2022;31(1):54–63. 10.1097/cej.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murthy KGS, Kuenzig E, et al. Temporal trends and relative risks of intestinal and extra-intestinal cancers in persons with inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based study from a large Canadian province (Abstract). Gastroenterology. 2023;164:212. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coward MS, Singh H, Benchimol EI, Kuenzig ME, Kaplan GG. Cancers associated with inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: a population-based analysis of cases and their matched controls (Abstract). Gastroenterology (2023).

- 25.Loosen SH, Jördens MS, Luedde M, Modest DP, Labuhn S, Luedde T, Kostev K, Roderburg C. Incidence of cancer in patients with irritable Bowl Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2021;10(24):5911. 10.3390/jcm10245911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Florens MV, Viola MF, Jain P, Decraecker L, Appeltans I, Cuende-Estevez M, Fabre N, Van Beek K, Perna E, Balemans D, Stakenborg N, Theofanous S, Bosmans G, Mondelaers SU, Matteoli G, Ibiza Martínez S, Lopez-Lopez C, Jaramillo-Polanco J, Talavera K, Alpizar YA, Feyerabend TB, Rodewald HR, Farre R, Redegeld FA, Si J, Raes J, Breynaert C, Schrijvers R, Bosteels C, Lambrecht BN, Boyd SD, Hoh RA, Cabooter D, Nelis M, Augustijns P, Hendrix S, Strid J, Bisschops R, Reed DE, Vanner SJ, Denadai-Souza A, Wouters MM, Boeckxstaens GE. Local immune response to food antigens drives meal-induced abdominal pain. Nature. 2021;590(7844):151–6. 10.1038/s41586-020-03118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazaridis N, Germanidis G. Current insights into the innate immune system dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31(2):171–87. 10.20524/aog.2018.0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Giessen J, van der Woude CJ, Peppelenbosch MP, Fuhler GM. A direct effect of sex hormones on epithelial barrier function in inflammatory Bowel disease models. Cells. 2019;8(3):261. 10.3390/cells8030261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Douglass J, Prasath V, Neace M, Atrchian S, Manjili MH, Shokouhi S, Habibi M. The microbiome and breast cancer: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;178(3):493–6. 10.1007/s10549-019-05407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;362:601. 10.1136/bmj.k601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu X. Mendelian randomization and pleiotropy analysis. Quant Biol. 2021;9(2):122–32. 10.1007/s40484-020-0216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Yarmolinsky J, Davies NM, Swanson SA, Van der Weele TJ, Higgins JPT, Timpson NJ, Dimou N, Langenberg C, Golub RM, Loder EW, Gallo V, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Davey Smith G, Egger M, Richards JB. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using Mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR statement. JAMA. 2021;326(16):1614–21. 10.1001/jama.2021.18236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanderson E, Glymour MM, Holmes MV, Kang H, Morrison J, Munafò MR, Palmer T, Schooling CM, Wallace C, Zhao Q, Smith GD. Mendelian randomization. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2022;2:6. 10.1038/s43586-021-00092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michailidou K, Lindström S, Dennis J, et al. Association analysis identifies 65 new breast cancer risk loci. Nature. 2017;551(7678):92–4. 10.1038/nature24284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Ren Q, Zheng Q, Bai Y, He S, Zhang Y, Ma H. Causal associations between gastroesophageal reflux disease and lung cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. Cancer Med. 2023;12(6):7552–9. 10.1002/cam4.5498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai J, He L, Wang H, Rong X, Chen M, Shen Q, Li X, Li M, Peng Y. Genetic liability for prescription opioid use and risk of cardiovascular diseases: a multivariable Mendelian randomization study. Addiction. 2022;117(5):1382–91. 10.1111/add.15767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernatsky S, Ramsey-Goldman R, Foulkes WD, Gordon C, Clarke AE. Breast, ovarian, and endometrial malignancies in systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(9):1478–81. 10.1038/bjc.2011.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parikh-Patel A, White RH, Allen M, Cress R. Cancer risk in a cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in California. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(8):887–94. 10.1007/s10552-008-9151-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smitten AL, Simon TA, Hochberg MC, Suissa S. A meta-analysis of the incidence of malignancy in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(2):R45. 10.1186/ar2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bharadwaj S, Kulkarni G, Shen B. Menstrual cycle, sex hormones in female inflammatory bowel disease patients with and without surgery. J Dig Dis. 2015;16(5):245–55. 10.1111/1751-2980.12247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lichtarowicz A, Norman C, Calcraft B, Morris JS, Rhodes J, Mayberry J. A study of the menopause, smoking, and contraception in women with Crohn’s disease. Q J Med. 1989;72(267):623–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hovde Ø, Høivik ML, Henriksen M, Solberg IC, Småstuen MC, Moum BA. Malignancies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from 20 years of follow-up in the IBSEN study. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(5):571–7. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutmann H, Hruz P, Zimmermann C, Straumann A, Terracciano L, Hammann F, Lehmann F, Beglinger C, Drewe J. Breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein expression in patients with newly diagnosed and therapy-refractory ulcerative colitis compared with healthy controls. Digestion. 2008;78(2–3):154–62. 10.1159/000179361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Englund G, Jacobson A, Rorsman F, Artursson P, Kindmark A, Rönnblom A. Efflux transporters in ulcerative colitis: decreased expression of BCRP (ABCG2) and Pgp (ABCB1). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(3):291–7. 10.1002/ibd.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Federico A, Morgillo F, Tuccillo C, Ciardiello F, Loguercio C. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in human carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(11):2381–6. 10.1002/ijc.23192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kruidenier L, Verspaget HW. Review article: oxidative stress as a pathogenic factor in inflammatory bowel disease—radicals or ridiculous? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(12):1997–2015. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai MS, Chen HP, Hung CM, Lee PH, Lin CL, Kao CH. Hospitalization for inflammatory bowel disease is associated with increased risk of breast cancer: a nationwide cohort study of an Asian population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(6):1996–2002. 10.1245/s10434-014-4198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosato V, Bosetti C, Talamini R, Levi F, Montella M, Giacosa A, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(12):2687–92. 10.1093/annonc/mdr025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagtmans MJ, Verspaget HW, Lamers CB, van Hogezand RA. Gender-related differences in the clinical course of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(5):1541–6. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mulak A, Taché Y, Larauche M. Sex hormones in the modulation of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(10):2433–48. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Betteridge JD, Armbruster SP, Maydonovitch C, Veerappan GR. Inflammatory bowel disease prevalence by age, gender, race, and geographic location in the U.S. military health care population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(7):1421–7. 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281334d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ortizo R, Lee SY, Nguyen ET, Jamal MM, Bechtold MM, Nguyen DL. Exposure to oral contraceptives increases the risk for development of inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis of case-controlled and cohort studies. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(9):1064–70. 10.1097/meg.0000000000000915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cornish JA, Tan E, Simillis C, Clark SK, Teare J, Tekkis PP. The risk of oral contraceptives in the etiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(9):2394–400. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jess T, Gamborg M, Matzen P, Munkholm P, Sørensen TI. Increased risk of intestinal cancer in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(12):2724–9. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herrera-Gómez RG, Grecea M, Gallois C, Boige V, Pautier P, Pistilli B, Planchard D, Malka D, Ducreux M, Mir O. Safety and efficacy of bevacizumab in cancer patients with inflammatory Bowel disease. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(12):2914. 10.3390/cancers14122914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.