Abstract

Harmful traditional practices are deeply ingrained beliefs and behaviors within a society that significantly impact the well-being of mothers and children. In Ethiopia, there is limited awareness and comprehension concerning the prevalence of harmful traditional practices in the puerperal period. The underlying reasons for engaging in harmful cultural practices during this period at the community level remain inadequately studied. The main aim of this research is to investigate the prevalence of harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period and its associated factors in public health facilities of southwestern Ethiopia, 2023. A mixed-methods community-based cross-sectional approach was undertaken from June 1st to July 31st, 2023. The study utilized the 24 kebeles in the Ilubabor and Buno Bedele Zones of Southwest Ethiopia. Three hundred twenty puerperal mothers in selected kebeles found in Ilubabor and Buno Bedele zones met inclusion criteria during the data collection period. We used a pretested semi-structured questionnaire, supplemented by in-depth interviews and focused group discussions with purposively selected 18 mothers. We utilized backward multiple logistic regressions were utilized to evaluate the interplay between various factors, with statistical significance set at a P-value below 0.05. This finding disclosed that the prevalence of harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period was 76.3%. Factors such as educational status (AOR = 3.47, CI = 1.57–9.27), rural residency (AOR = 2, CI = 1.51–4.88), absence of antenatal care in the last pregnancy (AOR = 6.42, CI = 2.33–8.74), and the place of delivery for the most recent child (AOR = 1.7, CI = 1.15–4.07) were significantly associated with these practices. The findings underscore a substantial prevalence of harmful traditional practices among mothers during the puerperal period. It is imperative for the Zonal Health department, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, to actively combat these practices within rural communities and healthcare facilities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-75344-x.

Keywords: Harmful, Traditional practice, Southwest Ethiopia, Puerperal period, Ilubabor zone

Subject terms: Health care, Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

Harmful traditional practices, referred to as cultural malpractices, are deeply ingrained in societies and can result in negative consequences for the physical, sexual, and psychological health of women, children, and entire communities. These actions may also contravene human rights and impede individuals’ ability to participate and benefit from social and economic opportunities1. These beliefs and actions are commonly endorsed and upheld within specific cultural contexts, yet they threaten the well-being of mothers and their offspring2. In various cultures, the puerperal period is considered a sensitive time, during which specific traditional practices occurs during caring for mothers and their babies3. These cultural practices frequently influence the healthcare provided to mothers and infants in the postpartum period, which is a critical determinant of maternal mortality4.

In Ethiopia, numerous traditional practices contribute positively to the well-being of various population groups, such as breastfeeding, postnatal care, and social gatherings that prioritize the needs of the elders, children, and religious leaders. However, alongside these beneficial practices, some harmful practices that commonly occurred during the puerperal period. These practices encompass the act of delivering at home, the use of cow dung on the umbilical cord, keeping infants shielded from direct sunlight, preference for male offspring, the avoidance of colostrum, the use of unsterile sharp objects for umbilical cord cutting, delaying the initiation of breastfeeding, bathing the newborn early, providing the newborn with butter and water, and administering “Koso” to the mother and the utilization of traditional herbal remedies1,5. Inadequate management of the puerperal period is a contributing factor to the marked disparity in maternal and infant mortality rates between developed and developing nations6–10. Internationally, about 287,000 women succumb to postpartum complications, with an additional 1 million newborns and 2.5 million infant deaths within the first 24 h and first four weeks of life11. In the puerperal period, around 33% of women in the United Kingdom and 50% in Taiwan developed distinct dietary patterns12. Studies carried out in Ethiopia have found that harmful practices are widespread in the puerperal period, with prevalence ranging from 37 to 85 percent5. In numerous low to middle-income nations, pre-lacteal nourishment provided to babies can be classified into three varieties: solely water, water-based options (like rice water, herbal blends, and juice), and milk-based alternatives (which encompass animal milk and infant formula)7. These harmful traditional practices and ideologies practiced during the puerperal period have a substantial effect on women’s attitudes toward seeking healthcare5. The precise frequency of maternal mortality resulting from harmful traditional practices in developing nations remains uncertain, but it accounts for 5–15% of total maternal mortality13. The preponderance of deaths among newborns, approximately 98 percent, takes place in developing nations, where the majority occur in home settings14.

In Ethiopia, a variety of factors, including but not limited to socioeconomic adversity, maternal age, levels of women’s empowerment, educational status, number of children, societal attitudes, religious beliefs, economic standing, gender dynamics, proximity to healthcare resources, and limited access to healthcare services, are known to contribute to the prevalence of harmful maternal practices among mothers in the country5,12. Substantial advancements have been achieved in advocating for the promotion of optimal breastfeeding, both in healthcare settings and local communities15. Breastfeeding and postnatal care follow-up are considered constructive traditional practices in Ethiopia, particularly prominent in rural regions of the country16.

Similarly, to combat harmful traditional practices, World Vision Ethiopia conducted specific and timely counseling on the Basic Health Service Package through faith-based organizations to decrease maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality by enhancing Supportive Supervision and Primary Health Care Units17. Additionally, Ethiopia has effectively utilized the National Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Guideline and recognized the advantage of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI). This initiative discourages giving newborns pre-lacteal feeding to encourage optimal breastfeeding practices18.

The persistence of harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period in various regions of the country continues despite previous studies and government interventions addressing this issue. The specific occurrence rate and determinants of these behaviors in the southwestern region of Ethiopia are not well studied. During this time, there has been a notable deficiency in comprehensive research that can be universally applied to comprehend harmful traditional practices. Hence, this research aimed to investigate the prevalence of harmful traditional practices and the factors influencing particular harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period in southwestern Ethiopia. The results of this research are vital in ascertaining the magnitude of the issue. Furthermore, the findings of this study assisted in increasing mothers’ understanding of the importance of embracing healthy practices during the puerperal period.

Methodology

Study area and period

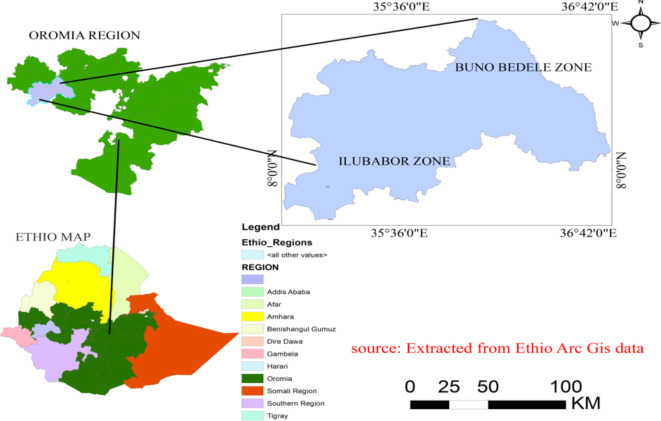

The study was conducted from 1st June to 31st July in 2023. Illubabor and Buno Bedelle Zones are found in the Oromia regional state, located in the southwest of Ethiopia, near to the Sudanese border. The Illubabor Zone is located approximately 600 km from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, and has an estimated elevation of 1817 m above sea level. As of 2020, the zonal administration’s total population was 968,303, comprising 14 rural woredas, one town administration, 23 urban kebeles, and 263 rural kebeles. In the realm of healthcare services, there were two hospitals, 41 health centers, and 263 health posts accessible.

On the contrary, Buno Bedele is a recently formed administrative division about 480 km from the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa. It has one town administration, nine rural districts, and a total population of 815,437. The zone has three functioning hospitals as well as 32 health centers and 246 health posts. Buno Bedele Zone, with an expanse of 5,856.5030 square kilometers, contains 1,126.64 square kilometers of forested terrain (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map showing the study area of Ilubabor and Buno Bedele zones constructed by Principal investigators extracted from Arc Gis software version 10.0 (https://arcgis.en.softonic.com/download).

Patient and public involvement

None.

Study design and population

A mixed cross-sectional study design was implemented in a community setting during the data collection period. The source population consisted of women who had given birth within the past six weeks in the Ilubabor and Buno Bedelle zones. The study population included women who met the inclusion criteria and had given birth within the specified timeframe in the selected woredas of the two zones.

Sample size and sampling technique

The sample size was determined using Epi Info TM version 3.1 StatCalc tool of Sample Size Calculation for population survey at 95% confidence interval (CI), 5% margin of error, with a proportion of 72.6% taken from a study in Loma woreda18. After considering the large sample size and a non-response rate of 5%, the sample size became 320, which is the sum of 305 and 15. A total of 320 participants were supposed for this study. It was calculated based on the following equation.

|

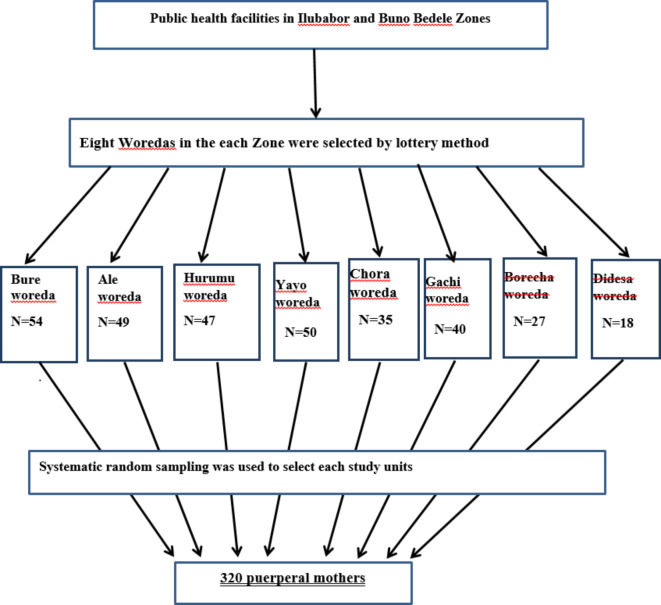

For the quantitative part, a multi-stage sampling method was used to choose the Zones, woredas, kebeles, and study participants. Two zones were deliberately chosen from the regions in Southwest Ethiopia for the initial stage. In the second stage, 30% of the administrative districts (n = 8) were chosen at random, with four districts selected from each geographical zone. In the third stage, 24 kebeles were selected from 8 chosen woredas using a lottery method. The study included postnatal mothers who met the inclusion criteria from selected kebeles in the Ilubabor Zone (n = 200) and Buno Bedelle Zone (n = 120). The study subjects were chosen in succession from each kebeles until the final required sample size was attained (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Diagrammatic representation of sampling procedure among puerperal mothers at Ilubabor and Buno Bedele Zones, Southwest Ethiopia, 2023.

Purposive sampling was implemented for gathering qualitative data. Three focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted, each consisting of six mothers, until idea saturation was reached. Eight Key informants (one at each health facility) were purposely chosen based on their strong connection with neonates and expected to provide valuable insights into the research at hand. The selection of key informants was influenced by the saturation level to determine the appropriate number.

Data collection tools, procedures, and quality controls

The quantitative component of the study involved the utilization of a semi-structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. This questionnaire was adapted and modified from existing literature reviews1,5,19–29. Initially, the questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated into the local language, Afan Oromo. The translated questionnaire was then translated back into English to ensure consistency. Data collection was conducted through face-to-face interviews. A total of eight data collectors with a bachelor’s degree in Midwifery and four health professionals with a Master’s degree were recruited as supervisors for this study.

Before data collection, the data collectors underwent a three-day training session. This training covered various topics related to the questionnaire, interviewing procedures, the study’s objectives, and the importance of maintaining privacy, discipline, and a respectful approach toward the interviewees. Additionally, the importance of maintaining the confidentiality of the respondents’ information was emphasized. A pretest was conducted in Agaro Town of Jimma Zone, involving 16 participants, which accounted for 5% of the total sample size. This pretest aimed to assess the reliability of the questionnaire, with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.78 set as the threshold. At the end of each day, the questionnaires were reviewed and checked for completeness, accuracy, and consistency by the supervisors. Any necessary corrections or discussions were conducted with the entire research team to ensure the quality of the data collection process.

In the qualitative part, the principal investigators oversaw the data collection process and made necessary adjustments as needed. A single research assistant was responsible for taking notes and recording audio during the motivational and in-depth interviews at each kebeles. Several measures were implemented to ensure the quality of the data collected. Firstly, the structured guide was pre-tested with four mothers. Secondly, the research assistant provided daily debriefings on the data. Thirdly, after each data-gathering session, the study respondents were allowed to discuss and confirm significant topic areas. Additionally, the women were granted access to the transcriptions and important findings to verify interpretations, and they were encouraged to share their opinions. The process of collecting data was subsequently followed by a review and discussion of the gathered data. The audio files were transcribed word for word and then translated into English to aid in the analysis process. The transcriptions were thoroughly examined and reviewed to obtain a thorough comprehension of the data. After the completion of the meticulous coding process performed individually by the lead researchers and the research assistant, the subsequent stage entailed prioritizing transcriptions that held the most comprehensive data pertinent to the research inquiries. Following the establishment of consistency among the coders, a manual for the codebook was created. The principal investigator carefully categorized all of the data. By clustering codes and categories, potential themes and categories were identified to address the research topic at hand. The manual for the codebook, as well as the associated categories and topics, underwent a process of refinement across three iterations of coding. In conclusion, the primary themes, categories, and quotations derived from the data were presented in conjunction with the study’s results.

Data processing and analysis

The qualitative portion of the study involved a thorough examination of the data. Epidata version 3.1 was used for data entry. The data was carefully reviewed for completeness and consistency before being cleaned, coded, and exported into the SPSS software version 26 for analysis (https://www.filehorse.com/download-ibm-spss-statistics/41390/download/). Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and cross-tabulation, were then performed for further analysis. The results of the study were presented using various graphical presentations like pie charts as well as texts and tables. For the multivariable logistic regression analysis, all variables that were found to be significant at a level of α = 0.25 in bivariate logistic regression were retained for consideration. The overall goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, which determined the model’s fitness, which was sig = 0.877. A Q–Q plot test and histogram were used to identify the normality of the data.

A multicollinearity test was performed using variance inflation factor to test the presence or absence of collinearity among them, and the result showed no evidence of multicollinearity (mean VIF = 2.55, Min VIF = 1.11, Max VIF = 5.23). The strength of the relationships between harmful traditional practices during puerperium and its explanatory variables was reported using adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95 percent confidence intervals (CI). In this study, a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant association.

The qualitative portion of the research utilized an inductive thematic approach to analyze the data. The data was examined through the use of Atlas.ti.7.1 software (https://atlas-ti.soft112.com/), enabling the generation of codes, categories, and themes.

Operational definitions

Harmful traditional practices or cultural malpractices encompass a range of actions that are considered detrimental to individuals’ well-being. These practices include various behaviors such as food taboos, avoidance of colostrum, delayed initiation of breastfeeding, giving cow milk or butter to newborns, and providing water instead of breast milk. Additionally, unsterile sharp materials are sometimes used to cut the umbilical cord, and unclean materials are used to tie it. Another harmful practice is giving newborns an early bath before 24 h of delivery and not properly tying the umbilical cord. Furthermore, engaging in sexual intercourse at specific intervals after delivery and taking a shower on the third or fourth day are also considered harmful practices. Lastly, some cultural beliefs involve providing collected blood from animals and giving a glass of butter to women following delivery. These practices have been identified as harmful and should be discouraged11.

Food taboo: Refers to the practice of abstaining from consuming certain foods and beverages during the perinatal period due to religious and cultural reasons5.

Puerperium/puerperal period/postpartum period: It is typically defined as the time frame starting from the expulsion of the placenta following childbirth and extending through the initial weeks postpartum. This phase is commonly recognized to span six weeks8.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

The study consisted of 320 participants, all of whom responded, resulting in a 100% response rate. The average age of the participants was 30 years, with a standard deviation of 14.6, ranging from 17 to 40 years. The majorities, 278 individuals (86.9%), were reported to be married [Table 1].

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants at Ilubabor and Buno Bedele Zones, southwest Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 320).

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of women | 17–26 | 94 | 29.4 |

| 27–36 | 159 | 49.7 | |

| > 37 | 67 | 20.9 | |

| Residence | Urban | 141 | 44.1 |

| Rural | 179 | 55.9 | |

| Religion | Protestant | 172 | 53.8 |

| Muslim | 95 | 29.7 | |

| Orthodox | 32 | 10.0 | |

| Others | 21 | 6.6 | |

| Marital status | Married | 278 | 86.9 |

| Unmarried | 24 | 7.5 | |

| Divorced | 10 | 3.1 | |

| Widowed | 8 | 2.5 | |

| Educational status | Cannot read and write | 179 | 55.9 |

| Can read and write | 66 | 20.6 | |

| Primary school | 38 | 11.9 | |

| Secondary school | 32 | 10.0 | |

| College and above | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Occupation | Housewife | 162 | 50.6 |

| Employed | 75 | 23.4 | |

| Merchant | 43 | 13.4 | |

| Student | 40 | 12.5 |

Obstetrics characteristics of study participants

Approximately 51.2% (164) of the respondents experienced multipara childbirth. A significant majority, 55.9% (179) of the participants sought the assistance of a healthcare provider during their most recent childbirth. Around 40.6% (130) of the participants received antenatal care (ANC) follow-up during their last pregnancy. The vast majority, 88% (283) of the participants availed antenatal care services at government health facilities. A considerable proportion, 56.9% (182) of the participants did not receive any counseling regarding cultural malpractices during the puerperal period (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric characteristics of study participants during puerperal period at Ilubabor and Buno Bedele Zones, southwest Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 320).

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | Primipara | 54 | 16.9 |

| Multipara | 113 | 35.3 | |

| Grandmultipara | 153 | 47.8 | |

| Antenatal care follow-up | Yes | 196 | 61.3 |

| No | 124 | 38.8 | |

| Number of ANC contacts | 1 Contact | 55 | 28.1 |

| 2 Contacts | 40 | 20.4 | |

| 3 Contacts | 60 | 30.6 | |

| 4 or more Contacts | 41 | 20.9 | |

| Where is your ANC follow up? | At government health facility | 283 | 88.4 |

| At Private Clinic | 37 | 11.6 | |

| Counseled about harmful traditional practice | Yes | 138 | 43.1 |

| No | 182 | 56.9 | |

| Where did you delivered your last child? | Home | 34 | 10.6 |

| Health facility | 286 | 89.4 |

Harmful traditional practice during the puerperal Period

During the puerperal period, a significant proportion of women engaged in harmful traditional practices, with a magnitude of 76.3% [95% CI = 72.48–80.1]. The timing of the first shower varied among the women, as 45.9% (147) of them took their first shower on the third day after delivery, while 31.9% (102) waited until the fourth day. Furthermore, a considerable number of respondents, 35.3% (113), engaged in sexual intercourse within six weeks following delivery.

In the case of home deliveries, a majority of women, 91.2% (31), applied substances such as butter, Vaseline, cow dung, and soil on the umbilical stump within three days after delivery to prevent drying and aid detachment. Among all study participants, a significant proportion, 64.7%, chose to avoid colostrum, and a majority of mothers, 73.6% (238), provided pre-lacteal feeding to their infants. Additionally, 32.2% (103) of women did not appropriately tie the cord after delivery.

On the other hand, within the first six weeks, a considerable number of mothers provided cow milk (55.0%), butter (20.9%), water (13.8%), and inappropriate formula feeding (10.3%) to their infants. However, more than half of the respondents, 52.9% (309), initiated breastfeeding immediately within one hour after delivery. Regarding baby wash, around 53.5% of the mothers washed their neonate between 1–24 h after delivery, 27.8 of the participants washed within one hour of delivery, and 18.7% washed after 24 h.

Factors associated with cultural malpractice during the postnatal period

Quantitative part

Bivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that various factors such as educational status, rural residence, lack of ANC follow-up, being a housewife, parity, and giving birth outside a health facility were statistically associated with harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period, with a p-value of less than 0.25. On the other hand, multivariable logistic regression analysis indicated that factors like educational status, rural residence, lack of ANC follow-up, and place of delivery were significantly associated with harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period.

Those mothers who could not read and write were 3.4 times more likely to partake in harmful traditional practices than those who could read and write (AOR = 3.47, CI = 1.57–9.27). Additionally, women residing in rural areas exhibited a twofold increase in the likelihood of engaging in harmful traditional practices than their urban counterparts (AOR = 2, CI = 1.51–4.88). Moreover, women who did not have ANC follow-up had 6.4 times higher odds of practicing harmful cultural practices during the puerperal period (AOR = 6.42, CI = 2.33–8.74). Lastly, women who gave birth outside a health facility without the presence of a healthcare provider were 1.7 times more inclined to participate in harmful traditional practices compared to those who delivered at a health facility with the assistance of a healthcare provider (AOR = 1.7, CI = 1.15–4.07 ) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Bi-variable and multiple logistic regressions on factors associated with harmful traditional practice during puerperal period at Ilubabor and Buno Bedele Zones, southwest Ethiopia, 2023.

| Variables | Categories | Harmful traditional practice during puerperium | COR(95%:CI) | AOR(95%:CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Residence | Urban | 95(29.7%) | 46(14.4%) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 149(46.6%) | 30(9.4%) | 2.41(1.42–4.83) | 2(1.51–4.88)* | |

| Mother`s Education | Cannot read and write | 139(43.4%) | 40(12.5%) | 5.2 (1.8–12.14)* | 3.47(1.57–9.27)* |

| Can read and write | 49(15.3%) | 17(5.3%) | 0.37 (.11–1.21)* | 0.31(.08–1.11) | |

| Primary school | 29(9.1%) | 9(2.8%) | 0.42 (.11–1.49) | 0.29 (.07–1.18) | |

| Secondary school | 26(8.1%) | 6(1.9%) | 0.56 (.14–2.19) | 0.43(.09–1.94) | |

| ≥ College | 2(0.63%) | 3(0.94%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Mother`s Occupation | Housewife | 124(38.8%) | 38(11.8%) | 0.36 (.12–1.08)* | 0.31(.09-.95) |

| Merchant | 48(15%) | 27(8.4%) | 0.19 (.06-.61) | 0.14 (.04-.47) | |

| Employed | 36(11.3%) | 7(2.2%) | 0.57 (.15–2.12) | 0.47 (0.12–1.91) | |

| Student | 36(11.3%) | 4(1.3%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Place of last child delivery | Home | 97(30.3%) | 43(13.4%) | 10 (5.93–16.8)* | 6.4 (2.34–8.74)* |

| Health facility | 33(10.3%) | 147(45.9%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Parity | Primipara | 43(13.4%) | 11(3.4%) | 1 | 1 |

| Multipara | 90(28.1%) | 23(7.2%) | 1 (.45–2.24) | 0.72 (.29–1.79) | |

| Grandmultipara | 111(34.7%) | 42(13.1%) | 0.68 (.32–1.43)* | 0.41 (.17-.97) | |

| Did the mother have ANC follow up | Yes | 40(12.5%) | 82(25.6%) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 14(4.4%) | 60(18.8%) | 2.14 (1.1–4.24)* | 1.7(1.15–4.07)* | |

Reference category, AOR = adjusted odd ratio, COR = crude odd ratio, CI = confidence interval, * = statistically significant.

Qualitative part

The participants contributed qualitative data through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. The examination of the data yielded three main themes through qualitative analysis. The participants underwent interviews on their socio-demographic characteristics, antenatal care contacts, and delivery place for the last child. Within the theme of socio-demographics, two sub-themes emerged: educational status and residence. Although the themes were said to be distinct, there was a significant overlap between them. Moreover, the participant answers to the interview inquiries frequently delved into multiple facets or subjects. In such instances, the interview data were stated in a manner that aligns with their most fitting context.

Educational status/literacy of the mother

Many participants concerns about the practices and caring for a new baby were motivated by a lack of knowledge or comprehension of what was typical.

Beshatu revealed that “I am sometimes anxious because I am aware of how little I know and comprehend about the potential impacts of these practices. She is active right now, even though I provided her with fresh butter after delivery. I heard a little about how it harms newborns. So I have been worrying for days and nights about what might happen to her as a result of these practices.”

Residence

Many of the participants’ concerns about performing traditional practices after childbirth depend on where they live. Mainly, those from rural areas explained that they had to practice being in line with their ancestors.

The 36-year-old lady said “I have to do those practices because I live here in a rural area. Unlike those from the cities, we are proud of keeping our ancestor’s traditions. It keeps me from evil spirits and blesses me and my newborn. But if I don’t do it, I will be worrying for days and nights about what might happen to me and my newborn.”

Antenatal care contacts

Some members explained that they performed these traditional practices since they had no ANC follow-up.

Fatuma clarified that regardless of having four children, she never visits a health facility during or after pregnancy; therefore, she has no information regarding these harmful traditional practices. ''I have heard from my friends who visited health centers during pregnancy that they were told me not to do this practice because it had no good outcome for their health or the health of their newborn.”

I had no prenatal care follow-up previously. And I delivered this child at a health center with the help of doctors. After delivery, the birth attendants ordered me to drink coffee and Mirinda (soft drink/ beverage) before starting breastfeeding. They considered this could be expressed as mother breast milk and help newborns to initiate breastfeeding. But my breast refused to express the milk, and my mother informed me to stay for some time to breastfeed the child. For the next three days, my child was not taking adequate milk but now am giving it well and the child is sucking eagerly” (A 21-year-old in-depth interview participant woman).”

Place of delivery

One of the focuses of the study is the mother’s place of delivery of their last child. Participants reveal little compassionate maternity care at health facilities during delivery. The participants state their experience as follows:

Megertu discussed her parents’ pressure to home delivery encouraged her to give birth at home after her sister who gave birth to her first child, ignored by health care professionals to practice these cultures. ‘’I do not know what the issue was about, but they said I should give birth at home. I thought that practice must possible immediately after delivery.’’.

Discussion

In this research, the prevalence of harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period in the Ilubabor and Buno Bedele zones was 76.3% [95% CI = 72.48–80.1]. This rate was notably higher compared to various studies carried out in rural India (52%)30, Northern KwaZulu-Natal (64%)31, Nigeria (35.3%)32, Egypt (37.5%)33, Meshenti town (50.9%)4, and Southwest Ethiopia (37%)34. The disparity observed could be attributed to differences in socio-demographic characteristics, sociocultural norms, regional variations, time gaps between study periods, accessibility to healthcare facilities, and affordability of medical costs. Notably, studies conducted in Ethiopia were not included in this comparison as most services are provided free of charge during the perinatal period.

One possible reason for the higher prevalence of harmful traditional practices is the challenge of accurately determining their prevalence at the community level, particularly practices that may have become normalized and no longer recognized as bad practices. Conversely, the prevalence found in this study was slightly lower than that reported in studies conducted in Turkey (84.2%)35, North Karnataka (85.7%)36, and Nigeria (81.5%)37. This variance could be due to discrepancies in study settings, sample sizes, and differences in socioeconomic characteristics. The findings of this study align with those of investigations conducted in Bangladesh (74%)38, Afar region (73.1%)39, Diredawa (74.6%)40, and Gurage zone (71.4%)18. This consistency could be explained by the proximity of study periods, study settings, and the study designs employed.

Level of education was a significant predictor of engaging in Harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period in various studies. This observation is consistent with research conducted in Nigeria, Northwest Ethiopia, Limmu Genet town of Jimma zone, and Wonago South Ethiopia, where students or educated were more likely to practice harmful traditional rituals compared to other categories. Another study conducted in the Pastoralist Community of the Afar Region, Ethiopia, found a correlation between educational status and the prevalence of Harmful traditional practices. The rationale behind this association could be that individuals who cannot read and write may lack an understanding of modern healthcare services and tend to rely on traditional healers and cultural remedies. Conversely, educated women are more informed about healthcare options during the postnatal period. Additionally, illiterate women may not fully comprehend the negative impact of harmful traditional practices on their health and that of their newborns, leading to lower awareness of preventive healthcare measures.

Furthermore, residency was linked to the practice of Harmful traditional rituals during the puerperal period. Women residing in rural areas were found to be approximately two times more likely to engage in harmful traditional practices compared to their urban counterparts. This finding was supported by studies conducted in the Alamata and the Gurage zones, where rural women were almost five times more likely to partake in harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period. The lack of access to information and resources in rural settings may contribute to the higher prevalence of harmful traditional practices among women in these areas.

During the puerperal period, the study found a significant association between ANC follow-up and harmful traditional practices. This finding is consistent with research conducted in the western region of Ghana41, the Awi Zone of the Amhara Region2, and Gurage zone5. The reason behind this association could be that women who receive ANC follow-up have the opportunity to receive counseling on the complications associated with harmful traditional practices, unlike women who do not receive ANC follow-up. Additionally, women who have ANC follow-up are more likely to deliver at health institutions under the care of skilled health professionals than those without ANC follow-up. It could further explain the association, as women who visit health facilities for ANC services are more aware of the risks and complications associated with postnatal cultural malpractices. Furthermore, ANC follow-up allows women to establish a relationship with health professionals and makes understanding of the actual practices carried out in health facilities, thus dispelling any cultural rumors.

Regarding the association between the place of delivery for their last child and cultural malpractices during the postnatal period, women who gave birth outside of a health facility were 1.7 times (AOR = 1.7, CI = 1.15–4.07 ) more likely to engage in cultural malpractices compared to women who gave birth at a health facility. This finding aligns with a study conducted in Southern Ethiopia. Women who give birth outside of a health facility do not have contact with healthcare providers during the postnatal period, which deprives them of information regarding the adverse effects of cultural malpractices on their health and the health of their infants.

In the qualitative analysis, similar to the study done in Dire Dawa City Ethiopia40, the socio-demographic theme was identified as the main factor toward harmful traditional practice during the puerperal period. It might be the result of the cultural similarity of the study population. It also showed the significance of societal awareness and communication to alter community member’s harmful traditions and foster the development of health-seeking behavior such as employing a full package of new ANC contact services.

Finally, as strength, this study used primary data rather than secondary data as in previous studies. The majority of prior studies used only a single study design at the facility level, but this study utilized a mixed community-based design. However, this study has some limitations. Firstly, the wealth index of the study participants was not conducted; we only focused on monthly income. In addition, due to the qualitative nature of the analysis, the conducted study may provide incomplete information and other limitations.

Conclusion

The prevalence of harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period was found to be more prevalent than the findings of a previous study conducted in a different location. Factors such as being unable to read and write, residing in rural areas, lack of antenatal care follow-up during the previous pregnancy, and delivering the last child outside of a healthcare facility were significantly associated with the practice of harmful traditional practices during the puerperal period. To address this issue, the collaboration between the Zonal Health department, healthcare providers, health extension workers, and religious leaders is crucial. They should actively work towards eradicating harmful traditional practices in rural communities and healthcare facilities.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mattu University, the Zonal Health Department, and the study participants of of Ilubabor and Buno Bedele Zones shared their time to give their genuine responses. Finally, we have heartfelt gratitude toward data collectors and supervisors of the study.

Author contributions

E.T.B. and B.D.D. made an equal contribution to the conception, design, and execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation. All authors have also read and agreed to its content, given final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The financial support for this research was gained from the Mattu University. The funder had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, and in the writing of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data sets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The STROBE checklist guideline was used.

Declaration

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical consideration

The Institutional Research Ethical Review Board of Mattu University College of Health Science provided ethical clearance by Ref.No.MDD/136/2016. The endorsement letter was acquired from the health department of Illubabor and Buno Bedele zone. The collection of data was done in a manner that ensured anonymity, and the investigators were responsible for safeguarding the information. All procedures adhered to the guidelines and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The research objectives were communicated to every puerperal mother, and subsequently, written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. No personal information was recorded, and unique codes were assigned to each questionnaire. Electronic data were protected with a confidential password. The research data was solely utilized for its intended purpose and was not shared with any external parties.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zenebe, K. et al. Prevalence of cultural malpractice and associated factors among women attending MCH Clinic at Debretabor Governmental Health Institutions South Gondar, Amhara Region, North West Ethiopia. Gynecol. Obst.10.4172/2161-0932.1000371 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melesse, et al. Cultural malpractices during labor/delivery and associated factors among women who had at least one history of delivery in selected Zones of Amhara region, North West Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.21, 10.1186/s12884-021-03971-7504 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Altuntuğ, K. et al. Traditional practices of mothers in the postpartum period: Evidence from Turkey. Afr. J. Reprod. Health.22, 94–102. 10.29063/ajrh2018/v22i1.9 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gedamu, H. et al. The prevalence of traditional malpractice during pregnancy, child birth, and postnatal period among women of childbearing age in Meshenti Town, 2016. Int. J. Reprod. Med.10.1155/2018/5945060 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abebe, H. et al. Harmful cultural practices during the perinatal period and associated factors among women of childbearing age in Southern Ethiopia: Community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE.16(7), e0254095 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke, J. Public Health in Africa - A Report of the CSIS Global Health Policy Center. J. Public Health Africa.10.4081/jphia.2010.e8 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teklay, et al. Pre-lacteal feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children less than two years of age in Aksum town, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2017: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatrics.18, 10.1186/s12887-018-1284-7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.World Health Organization, World Bank, United Nations Population Fund & United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990–2015: estimates from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/194254 (2015).

- 9.Ambaw, Y. L. et al. Antenatal care follow-up decreases the likelihood of cultural malpractice during childbirth and postpartum among women who gave birth in the last one-year in Gozamen district, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health.80(1), 53 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayalew, T. & Asmare, E. Colostrum avoidance practice among primipara mothers in urban Northwest Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.21(1), 123 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kassahun, G., Wakgari, N. & Abraham, R. Patterns and predictive factors of unhealthy practice among mothers during pregnancy, childbirth, postnatal and newborn care in Southern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes.12, 594 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kibr, G. A narrative review of nutritional malpractices, motivational drivers, and consequences in pregnant women: Evidence from recent literature and program implications in Ethiopia. ScientificWorldJournal.10.1155/2021/5580039 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkateswarlu, M. et al. Assessment of cultural beliefs and practices during the postnatal period in an urban field practice area of SRMC, Nandyal, Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health.6(8), 3378–3383 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochieng, et al. Barriers to formal health care seeking during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal period: a qualitative study in Siaya County in rural Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.19, 339 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bermio, et al. Beliefs and practices during pregnancy, labor and delivery, postpartum and infant care of women in the Second District of Ilocos Sur, Philippines. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res.8, 850–860 (2017).

- 16.Wudu, M. A. Determinants of early days of newborn feeding malpractice among mothers of children less than one year of age in Mizan-Aman Town, Southwestern Ethiopia, 2020. Pediatric Health Med. Ther.12, 79–89 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beharu, et al. Norms and Practices of Gewata Community toward Maternal and Child Health Services. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-585019/v1 (2021).

- 18.Habte, et al. Cultural malpractices during pregnancy, childbirth, and postnatal period among women of childbearing age in Loma Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon. 9, E12792. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12792 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Nigussie, et al. Cultural malpractices during pregnancy, child birth and postnatal period among women of child-bearing age in Limmu Genet Town, Southwest Ethiopia. Sci. J. Public Health. 3, 752–756 (2015).

- 20.Ebabu, A. et al. Traditional practice affecting maternal health in pastoralist community of afar Region, Ethiopia: A facility-based cross-sectional study. J. Midw. Reprod. Health9(3), 2817–2827 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messele, H. Traditional maternal health beliefs and practices in Southern Tigray: The case of Raya Alamata District. Anat. Physiol.10.4172/2161-0940.1000298 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdollahi, F. et al. Postpartum mental health in relation to sociocultural practices. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol.55(1), 76–80 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kokushubira, et al. Factors affecting exclusive breastfeeding among post-natal mothers in Kinondoni Municipality, Dar es Salaam. 5, 42–48 (2017).

- 24.Withers, M. et al. Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: A review of the evidence from Asian countries. Midwifery.56, 158–170 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramulondi, et al. Traditional food taboos and practices during pregnancy, postpartum recovery, and infant care of Zulu women in northern KwaZulu-Natal. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine17, 15 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Rogers, N. L. et al. Colostrum avoidance, pre-lacteal feeding, and late breast-feeding initiation in rural Northern Ethiopia. Public Health Nutr.14(11), 2029–2036 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aynalem, B. Y. et al. Cultural beliefs and traditional practices during pregnancy, child birth, and the postpartum period in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: A qualitative study. Womens Health Rep. (New Rochelle).4(1), 415–422 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gashaw, A. et al. Pre-lacteal feeding practice and associated factors among mothers having children aged less than six months in Dilla town, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr.24(1), 208 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. World health statistics 2012. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44844 (2012).

- 30.Bhakta, et al. Cultural, social, religious beliefs and practices during postpartum period among post natal women in selected rural and urban health care settings. Indonesian J. Glob. Health Res.1, 1–12. 10.37287/ijghr.v1i1.10 (2019).

- 31.Ramulondi, M. et al. Traditional food taboos and practices during pregnancy, postpartum recovery, and infant care of Zulu women in northern KwaZulu-Natal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed.17(1), 15 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikeaba, N. C. et al. Harmful traditional practices among market women in Ojuwoye market mushin, South West, Nigeria. Ann. Afr. Med.21(3), 208–216 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osman, A. et al. Maternal cultural practices for neonates’ care in upper Egypt. Women Birth.31(4), e278–e285 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tesfaye, M. et al. Prevalence of harmful traditional practices during pregnancy and associated factors in Southwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open.12(11), e063328 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitila, et al. Folk practice during childbirth and reasons for the practice in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Gynecol. Obst.08. 10.4172/2161-0932.1000465 (2018).

- 36.Morris, et al. Maternal health practices, beliefs and traditions in Southeast Madagascar. Afr. J. Reprod. Health18(3), 101–117 (2014). [PubMed]

- 37.Jimoh, A. O. et al. A cross-sectional study of traditional practices affecting maternal and newborn health in rural Nigeria. Pan. Afr. Med. J.31, 64. 10.11604/pamj.2018.31.64.15880 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Md Khobair Hossain. Beliefs and Practices during Antenatal and Postnatal Period among the Host Communities in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.08.001451 (2020).

- 39.Getachew, G. et al. Early newborn bathing and associated factors among mothers in Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia. J. Trop. Pediatr.10.1093/tropej/fmac117 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hailu, M. et al. Cultural malpractice during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period and its associated factors among women who gave birth once in Dire Dawa city administration, Eastern Ethiopia, in 2021. Front. Glob. Womens Health.10.3389/fgwh.2023.1131626 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patience, O. et al. Food prohibitions and other traditional practices in pregnancy: a qualitative study in western Region of Ghana. Adv. Reprod. Sci.3, 41–49 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The STROBE checklist guideline was used.