Abstract

Proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology represents a groundbreaking development in drug discovery, leveraging the ubiquitin‒proteasome system to specifically degrade proteins responsible for the disease. PROTAC is characterized by its unique heterobifunctional structure, which comprises two functional domains connected by a linker. The linker plays a pivotal role in determining PROTAC's biodegradative efficacy. Advanced and rationally designed functional linkers for PROTAC are under development. Nonetheless, the correlation between linker characteristics and PROTAC efficacy remains under-investigated. Consequently, this study will present a multidisciplinary analysis of PROTAC linkers and their impact on efficacy, thereby guiding the rational design of linkers. We will primarily discuss the structural types and characteristics of PROTAC linkers, and the optimization strategies used for their rational design. Furthermore, we will discuss how factors like linker length, group type, flexibility, and linkage site affect the biodegradation efficiency of PROTACs. We believe that this work will contribute towards the advancement of rational linker design in the PROTAC research area.

Key words: PROTAC, PROTAC linker, Linker characteristics, Rational design, Biodegradation efficiency

Graphical abstract

PROTAC represents a groundbreaking biotechnology in drug discovery. The characteristics of linker significantly impact the biodegradation efficiency of PROTAC, thereby governing the rational design of PROTAC.

1. Introduction

The proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) hold remarkable promise for resolving issues related to small-molecule inhibitors1, 2, 3, 4. These inhibitors frequently encounter difficulties in targeting proteins that are considered “undruggable”, are more likely to develop resistance, and often necessitate higher systemic drug concentrations to maintain therapeutic efficacy5, 6, 7, 8. As a novel drug development approach, PROTACs use the UPS (ubiquitin‒proteasome system) to biodegrade specific proteins, thereby increasing the probability of successfully overcoming these challenges7,9, 10, 11. This process occurs by a catalytic mechanism that leads to the dissociation of the target protein following polyubiquitination, producing therapeutic efficacy at lower concentrations12. PROTACs biodegrade target proteins of various conformations, which can overcome drug resistance due to target mutations, produce an increase in the durations of action, minimize off-target effects, and decrease the incidence of adverse effects. Furthermore, inactive or less active inhibitors can be converted into potent biodegraders13,14. As a result of these beneficial characteristics, PROTAC has garnered significant interest from both academic and industrial researchers, leading to a significant increase in the number of published studies on PROTAC15.

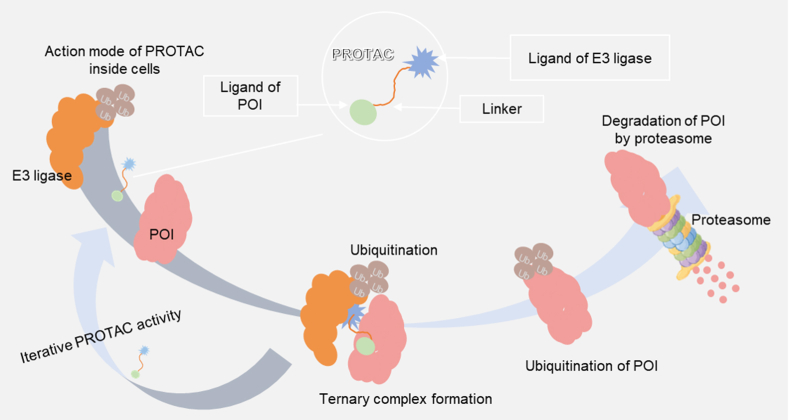

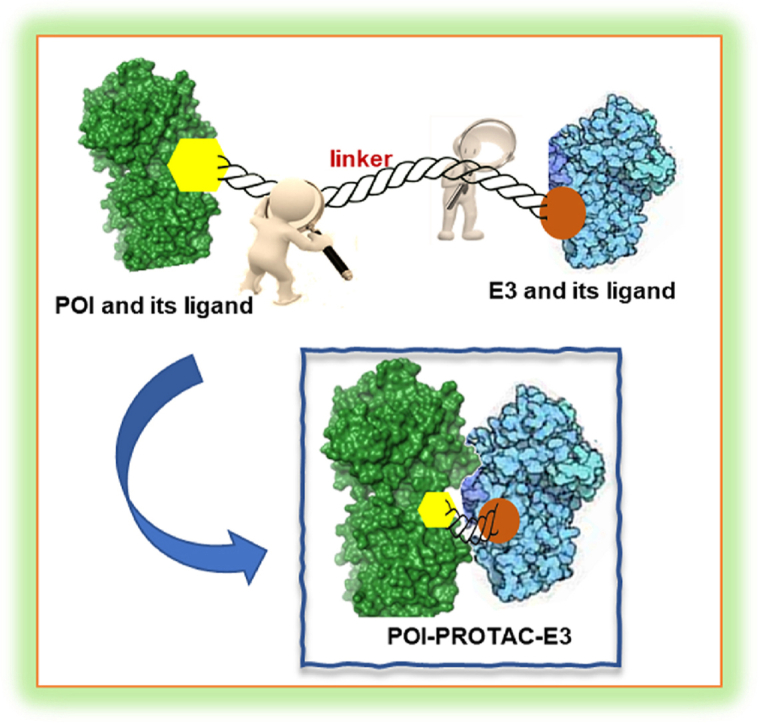

PROTAC is a unique molecule that has heterobifunctionality, characterized by a linker component that effectively links a protein of interest (POI) ligand with an E3 ubiquitin ligase (E3) recruiting ligand16. The unique configuration of PROTAC facilitates the establishment of a stable ternary complex between E3 ligase and POI. This ternary complex produces the selective polyubiquitination of the POI, ultimately leading to its biodegradation by the UPS (Fig. 1)17. Numerous studies have reported the crucial role of the linker in determining the efficacy of PROTAC18. The linker not only supports the stable formation of the ternary complex but also affects the physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of PROTACs19,20. The length, group type, flexibility, and linkage site of the linker all impact the stability of the ternary complex and, ultimately, the biodegradation efficiency of PROTACs21,22. Given these intricate relationships, it is evident that the linker is the essential factor in ensuring greater specificity and targeting efficiency of PROTACs23.

Figure 1.

The three key components of PROTAC are: 1) the E3 ligase ligand; 2) the POI ligand and 3) the linker connecting the two ligands. The PROTAC's mode of action within cells involves promoting the interaction among the POI and E3 to produce a stable ternary complex. POI is ubiquitinated as a result of this interaction and subsequently biodegraded by proteasomes, which typically consume multiple ubiquitin molecules labeled with the POI.

Recently, there has been a growing number of publications reporting progress in the design and optimization of PROTAC linkers. These efforts have primarily focused on linker length, group type, flexibility, and linkage site. For instance, Wurz et al. 24 discovered that increasing the linker length facilitated the formation of a ternary complex, ultimately increasing the biodegradation efficiency of PROTAC for the protein, bromodomain and extraterminal domain-4 (BRD4). Similarly, Han et al. replaced an alkyl chain with a pyridyl group of similar length, creating a potent PROTAC for the biodegradation of the androgen receptor (AR), by increasing solubility and pharmacokinetics25. Farnaby et al. increased linker rigidity by introducing a phenyl group, leading to an additional T-shaped stacking interaction that increased the potency of the PROTAC for (BAF)/phospho-BAF chromatin remodeling complexes26. Zengerle et al. used crystallographic data to identify an optimal linkage site that would increase the protein‒protein interactions, directly increasing the PROTAC's efficacy for BRD427. These studies have significantly advanced the PROTAC field and provided valuable insights for the design of linkers. However, there is still a need for more advanced and well-designed functional linkers to further revolutionize PROTAC technology23. To date, the relationship between linker characteristics and PROTAC efficacy has rarely been systematically explored.

In this study, we have focused our efforts on the multidisciplinary analysis of the structures and properties of PROTAC linkers and their effect on the biodegradation efficacy of PROTACs. Our major objective is to offer valuable insights into the rational design of PROTAC linkers. We have primarily examined three key areas: 1) an analysis of the various structural types and characteristics of PROTAC linkers reported to date; 2) the optimization strategies utilized in the rational design of effective PROTAC linkers; and 3) the impact of linker length, group type, flexibility, and linkage site on the ternary complex formation, pharmacokinetics, protein‒protein interactions, and ultimately, PROTAC biodegradation efficiency. We use case studies to demonstrate these comprehensive effects. We hope that our work will increase the understanding of PROTAC linker rational design, thereby facilitating future research in this field.

2. Structural types and characteristics of PROTAC linkers

2.1. An overview of existing PROTAC linkers

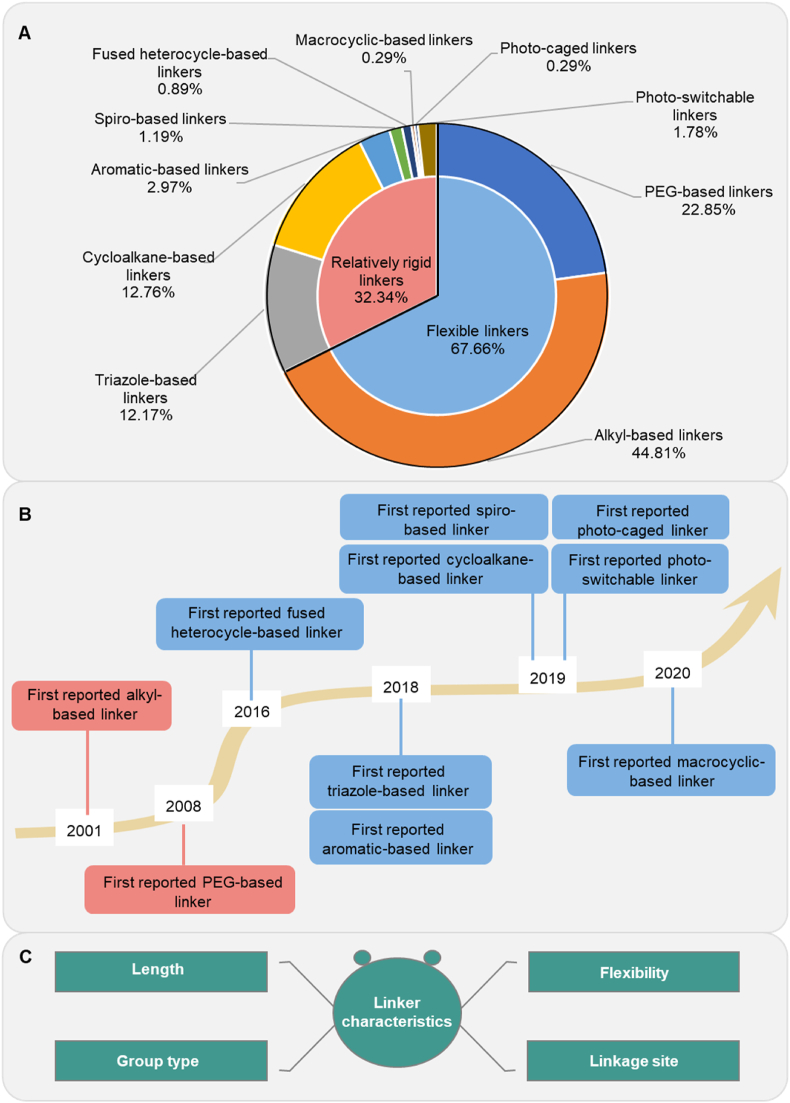

Given the crucial role of the linkers in PROTACs, we carried out a thorough examination of the various linker structural types and their frequencies in reported PROTACs, spanning from the first reported PROTAC in 200128 to the end of 2023. Based on a statistical principle, we only selected the linker of the most potent PROTAC in each paper for analysis. Our dataset comprises a total of 337 PROTACs. By analyzing the linkers of these PROTACs, we found that they can be categorized into two broad groups, according to their structural types: flexible linkers and relatively rigid linkers. The flexible linkers are the most widely used type, accounting for 67.66% of the total. These mainly include alkyl-based linkers and polyethyleneglycol-based (PEG-based) linkers, which account for 44.81% and 22.85% of the total, respectively (Fig. 2A). The flexible linkers are considered a standard feature in the PROTAC field, and they can not only enable systematic variations in linker length but also facilitate the rapid synthesis of molecules with distinct linkers29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34. The relatively rigid linkers account for 32.34% of the total and encompass eight types. Among them, triazole-based linkers and cycloalkane-based linkers are the two most commonly used types, accounting for 12.17% and 12.76% of the total, respectively. The advent of “click chemistry” reaction24,35,36, allows for the insertion of triazole-based linkers into PROTACs, which significantly addressed the challenges of synthesis in this field, thereby increasing the utilization rate of these linkers37. The cycloalkane-based linkers, particularly piperazine and piperazine groups, are the most widely used due to their excellent stability and chemical reactivity. These properties allow for the modulation of PROTAC polarity, thereby meeting design requirements and increasing cell permeability and biodegradation efficacy38, 39, 40. Additionally, in the relatively rigid linkers, the optically controlled linkers have increasingly been used as linkers in recent years41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46. These linkers introduce light-responsive protective groups, yielding PROTACs with increased targeting specificity, greater stability, and unique on-off interactions. This linker type holds significant promise in the field of PROTACs and will likely be widely used due to its potential in cancer precision diagnosis44. Overall, our analysis highlights the large diversity of linker structures and emphasizes the need for the design of novel linkers to increase PROTAC biodegradability.

Figure 2.

Structural types and characteristics of PROTAC linkers. (A) The frequency of occurrence of each type of linker in PROTACs encompasses the period from the initial report of PROTAC in 2001 up until the end of 2023. We have only counted the linker in the most effective PROTAC described in each publication. (B) A timeline has been created to indicate the initial appearance of each linker type in the scientific literature. (C) The linker characteristics that impact the biodegradation efficiency of the PROTAC have been identified.

To understand the emergence of different linker types over time, we examined the timeline in Fig. 2B. The initial linker introduced in 2001 was a flexible linear alkyl chain, which was utilized in the first PROTAC design28. In 2008, the amphiphilic PEG chain was introduced to enhance solubility and cell permeability47. In contrast, a fused heterocycle-based linker, the first relatively rigid linker, emerged in 2016 through bio-orthogonal click chemistry48. This was followed by a notable increase in PROTAC-related publications, highlighting their growing popularity and significance. Since 2018, additional linker types have been introduced, including the aromatic-49 and triazole-based linkers24,40,50, 51, 52, 53, 54. In 2019, cycloalkane-25,55, 56, 57, spiro-58,59, photo-caged-45 and photo-switchable-based linkers41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, were introduced. In 2020, a macrocyclic-based linker was designed, using computational modeling to produce the most potent PROTACs60. The significant growth in PROTAC linker diversity can be attributed to advancements in synthesis technology and more rational design strategies. These advancements will further facilitate the development of the PROTAC field19,24,61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66.

2.2. Flexible linkers

Flexible linkers, chains of a certain length that may be saturated or unsaturated67, are often categorized as alkyl-based or PEG-based linkers depending on their structural features (Table 1)13,68, 69, 70. These linkers are standard in the PROTAC field. The alkyl-based linker, which is based on saturated or unsaturated alkyl chains, often contains oxygen, nitrogen, carbonyl, secondary amine, or an amide, inserted at various locations30,71, 72, 73, 74. This linker is highly stable under physiological conditions and has a simple structure, making it relatively easy to synthesize30. It effectively links the warhead and the E3 ligase binder. However, this linker is frequently hydrophobic, leading to the poor water solubility of the resulting PROTAC and affecting its properties in physiological environments68,75. In fact, introducing polar groups into the structure can solve this problem, and these polar groups can also be used for further modification and connection with other groups68,75. Furthermore, these linkers are more susceptible to oxidative metabolism in vivo. For example, Khan et al.76 discovered a selective BCL-XL PROTAC degrader DT2216, with an aliphatic linker, to achieve safe and potent antitumor efficacy. The linker adds flexibility to DT2216 and its optimal length allows for the introduction of the favorable formation of a BCL-XL-DT2216-VHL ternary complex, resulting in greater BCL-XL biodegradation efficacy. Additional examples are presented in Table 1 and Supporting Information Table S1.

Table 1.

The types of PROTAC linkers and their associated information.

| Linker type | Common structure | Representative PROTAC | POI | E3 ligase | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible linker | Alkyl-based linker |  |

|

BCL-XL | VHL | 76 |

|

BET | CRBN | 32 | |||

|

BET | CRBN | 107 | |||

|

GSPT1 | CRBN | 108 | |||

|

AR | VHL | 109 | |||

|

PLK1 | VHL | 110 | |||

|

SOS1 | VHL | 111 | |||

|

GR | CRBN | 112 | |||

| Tau | Keap1 | 12 | ||||

|

ERα | VHL | 77 | |||

| PEG-based linker |  |

|

BRD4 | CRBN | 85 | |

|

BET | VHL | 33 | |||

|

BRD4 | VHL | 27 | |||

|

TDP-43 | CRBN | 113 | |||

|

HPK1 | CRBN | 114 | |||

|

FLT-3 | VHL | 13 | |||

|

BTK | CRBN | 6 | |||

|

FAK | VHL | 115 | |||

|

BRD4, P53 |

MDM2 | 21 | |||

|

ALK | CRBN | 116 | |||

| Relatively rigid linker | Triazole-based linker |  |

|

BRD3, BRD4 |

CRBN | 117 |

|

FKBP51 | VHL | 118 | |||

|

BCL-XL | CRBN | 103 | |||

|

HDAC6 | CRBN | 119 | |||

|

PARP1 | MDM2 | 38 | |||

|

FAK | CRBN | 120 | |||

|

p38 | CRBN | 121 | |||

|

ER | cIAP1 | 122 | |||

|

Sirt2 | CRBN | 51 | |||

|

MAFF | cIAP1 | 123 | |||

| Cycloalkane-based linker |  |

|

AR | CRBN | 98 | |

|

ER | CRBN | 97 | |||

|

SHP2 | VHL | 124 | |||

|

CDK9 | CRBN | 125 | |||

|

AR | CRBN | 126 | |||

|

LCK | CRBN | 127 | |||

|

c-Src | CRBN | 128 | |||

|

BTK | CRBN | 129 | |||

|

PLK4 | CRBN | 130 | |||

|

AR | CRBN | 131 | |||

| Aromatic-based linker |  |

|

PIKfyve | VHL | 106 | |

|

PIPK2 | VHL | 132 | |||

|

BTK | CRBN | 133 | |||

|

BET | CRBN | 134 | |||

|

PTP1B, TC-PTP | CRBN | 90 | |||

|

PCAF, GCN5 | CRBN | 49 | |||

|

AR | VHL | 135 | |||

| FGFR1 | VHL | 136 | ||||

|

EGFR | CRBN | 137 | |||

|

GSPT1 | CRBN | 138 | |||

| Spiro-based linker |  |

|

MLKL | CRBN | 139 | |

|

SMARCA2 | VHL | 140 | |||

|

ERα | CRBN | 141 | |||

|

AR | CRBN | 58 | |||

| Fused heterocycle-based linkers |  |

|

BRD4 | CRBN | 48 | |

|

CDK12 | CRBN | 102 | |||

|

NSPs | CRBN | 93 | |||

| Macrocyclic-based linker | – |  |

BRD4 | VHL | 60 | |

| Photo-caged linkers |  |

|

BRD4 | CRBN | 45 | |

| Photo-switchable linkers |  |

|

BCR-ABL | CRBN | 41 | |

|

BRD2, BRD4 | VHL | 43 | |||

|

BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, FKBP12 | CRBN | 44 | |||

|

BRD2, BRD4 | CRBN | 46 | |||

|

FAK, AURORA-A, TBK1 | CRBN | 46 | |||

|

CaMKⅡα | CRBN | 42 | |||

In alkyl-based linkers, various amino acids or short peptide sequences, such as aminohexanoic acid (Ahx), glycine, serine, and GSGS, are used as linkers in peptide PROTACs12,77,78. Although these PROTACs have produced effective biodegradation of numerous targets, they often have limited cell permeability and are highly susceptible to cleavage by proteases. To address these limitations, amino acids or short peptide sequences with cell-penetrating capabilities have been introduced to increase flexibility and facilitate the uptake of the PROTACs into intact cells79. The GSGS linker is currently the most widely used. This linker, along with the resulting PROTAC, can be easily synthesized using the standard Fmoc method. Lu et al.12 have developed a Keap1-dependent peptide PROTAC that degrades tau protein by the UPS degradation pathway. This PROTAC uses a short GSGS peptide to link the tau recognition moiety to the Keap1 binding moiety, increasing its flexibility and binding capabilities. Other examples are provided in Table 1 and Table S1.

The PEG-based linkers often consist of two or more consecutive ethylene glycol units and can be integrated with other chains (Table 1)26,80, 81, 82, 83. PEG's hydrophilic nature increases the water solubility of PROTACs, increasing their adaptability to physiological environments30. PEG's capacity to attach multiple chemical functions enhances the modifiability of PROTACs and their connectivity to other groups84. Furthermore, PEG has good compatibility in vivo, mitigating the risk of inducing an immune response or toxicity61. Nevertheless, compared to alkyl-based linkers, PEG-based linkers may have reduced stability under specific physiological conditions and their synthesis can be more complicated. The significant cost of PEG's raw materials can also contribute to an increase in the overall cost of PROTACs. Furthermore, these linkers are more susceptible to oxidative metabolism in vivo. For example, Crews et al.85 used a PEG linker to conjugate a classic BRD4 binding motif from the triazole-diazepine acetamide with a cereblon (CRBN) binding motif form the IMiD class pomalidomide, resulting in the potent PROTAC ARV-825, which has anticancer efficacy. The PEG linker's significant conformational flexibility optimized the ternary complex establishment between PROTAC, BRD4, and CRBN, thus producing an efficacious compound. Additional information is provided in Table 1 and Table S1.

2.3. Relatively rigid linkers

The linkers containing cyclic structures have been characterized as being relatively rigid40,48,86,87. Depending on the type of cyclic structures, these linkers can be further categorized into several types, including triazole-87, aromatic-88, cycloalkane-55, spiro-59, fused heterocycle-32, and macrocyclic-based60. Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of these types of cyclic structures. The triazole- and cycloalkane-based linkers are the most widely used. Triazole-based linkers contain a triazole group, which is easily accessible through copper-catalyzed azide‒alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction, also known as “click chemistry”89. The click reaction efficiently produces the triazole moiety with near-stoichiometric yield under mild conditions. This reaction has excellent compatibility with other functional groups, even in the presence of water90. This has greatly facilitated the application of this type of linker in the PROTAC field91. Furthermore, unlike the flexible linkers, which are more prone to oxidative metabolism in vivo, the triazole structure is more stable in vivo and has a longer duration of action92. As an example, Bagka et al. have developed a long-acting Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, PROTAC HPP-9, which utilizes a triazole-based linker to prolong biodegradation of BET bromodomains. The rigid linker in this compound ensures a stable interaction between the warhead HPI-1 and the POI, whereas the optimal linker length allows both moieties bind to their respective proteins, forming a stable low-energy complex93. Other examples are summarized in Table 1 and Table S1.

The cycloalkane-based linkers, a commonly utilized class of rigid linkers, frequently incorporate fragments of piperazine94, piperidine55, tetrahydropyrrole95, or cyclohexane96. Currently, the inclusion of piperazine and piperidine fragments is particularly prevalent. These linkers increase the metabolic stability of the resulting PROTACs, producing a longer duration of action, while maintaining their structural integrity94. Furthermore, they increase the water solubility of PROTACs, facilitating their dissolution and distribution within the body60. Currently, multiple PROTACs containing this type of linker are undergoing evaluation in clinical trials: ARV-47197, ARV-11098, CFT863499, KT-413100, and NX2127101. ARV-110 is a pertinent example. It selectively targets and produces the biodegradation of the androgen receptor (AR) protein, and is being developed to treat metastatic castration-resistance prostate cancer (mCRPC). During its development, the original flexible linker was modified into a more rigid structure, using piperidine and piperazine connections, which significantly increased its metabolic stability and therapeutic potency. The same linker design has also been used for the synthesis of the PROTAC drug, ARV-417, which is undergoing evaluation in a Phase 3 trail. Additional examples are shown in Table 1 and Table S1.

The photo-caged PROTAC linkers feature photosensitive groups that can be triggered to undergo irreversible photo-cracking reactions, after exposure to specific wavelengths of light45. Using light, the linker's protective group is effectively removed, resulting in the biodegradation of the targeted protein. This type of linker in PROTACs addresses the problem of off-target toxicity. The resulting PROTACs use a prodrug design strategy, enabling selective activation within target tissues. Xue et al.45 introduced the bulky DMNB photo-cage structure to the linker of the potent PROTAC dBET1, creating the groundbreaking photocaged PROTAC (pc-PROTAC), that biodegraded the protein, bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4). When exposed to light at 365 nm, pc-PROTAC efficiently generated dBET1 and produced the biodegradation of BRD4 in cells. This approach offers a promising strategy for achieving selective biodegradation of target proteins while minimizing the off-target adverse effects.

The photo-switchable PROTAC linkers use azo groups, rather than alkyl or polyether fragments, to attach the POI's ligand to the moiety, which recruits E3 ligase41. Following exposure to specific wavelengths of light, these linkers cause the resulting PROTACs to suffer reversible photoisomerization within their trans and cis isomeric variants. This allows for precise and bidirectional control over PROTAC biodegradative efficacy42. The predicted influence of PROTAC conformational changes, induced by alteration in the linker conformation, on protein biodegradation determines the regulating effect. For example, Pfaff et al.43 developed the first-in-class photoPROTACs that included a linker made of ortho-F4-azobenzene fragments introduced within the ligand of the BET protein, and the moiety recruited by the E3 ligase, van Hippel-Landau (VHL). These linkers allow for the continuous spatiotemporal control of the biodegradation of BET proteins by using wavelengths of 415 nm and 530 nm, minimizing the systemic toxicity produced by traditional anti-cancer drugs. Other examples are listed in Table 1.

Other infrequent rigid linkers in PROTACs include those based on aromatic, spiro, fused heterocycles, and macrocycles. The phenyl structure is present in the aromatic-based linkers, and thus far, only 10 related papers have been published88. Four papers have been published about spiro-based linkers containing structures, such as 7-azaspiro[3.5]nonane58, or 3,9-diazaspiro[5.5]undecane59. Three papers have been published regarding the fused heterocycle-based linkers, such as benzo[d]imidazole102 or cyclohepta[d]pyridazine48. Furthermore, one paper described the synthesis and characterization of a macrocyclic-based linker, which was developed using a computer-aided drug design strategy60. These rigid linkers are designed to increase the stability of PROTACs by stabilizing their structural and metabolic properties. Overall, these structures have good compatibility with other structural groups87,103,104. By decreasing the reconfiguration of the bind conformation of the ligands to that of POI or E3 ligase, they can maintain the initial interaction105. They form stacking interactions with the POI or E3 ligase, which increases the stability of the POI-PROTAC-E3 ternary complex and increases the biodegradation potency of the resulting PROTACs88. For example, Li et al.106 discovered a first-in-class phosphoinositide kinase PIKfyve biodegrader, PIK5-12d, which had an aromatic-based linker. PIK5-12d selectively induced PIKfyve biodegradation that was dependent on VHL and proteasome. The introduction of a phenyl ring in the linker maintained the aromaticity of the pyridyl group in the POI ligand, which may contribute to its binding with the PIKfyve protein, producing the highest PIKfyve biodegradation activity. Additional examples are shown in Table 1.

2.4. Linker characteristics

The examination of the structure‒activity relationship (SAR) of PROTACs highlights the significance that specific linker characteristics involved in their function (Fig. 2C). The length of the linker significantly affects the establishment and stability of the POI-PROTAC-E3 complex4,51,68,142,143. The type of group within the linker significantly affects pharmacokinetic properties6,29,64. Furthermore, the linkage site of the linker significantly affects protein‒protein interactions144, 145, 146. In summary, linker characteristics have a significant impact on PROTAC biodegradation efficacy by modifying interactions between the PROTAC, POI, and E3 ligase.

3. Reasonable design and optimization strategies for PROTAC linkers

3.1. Basic strategies

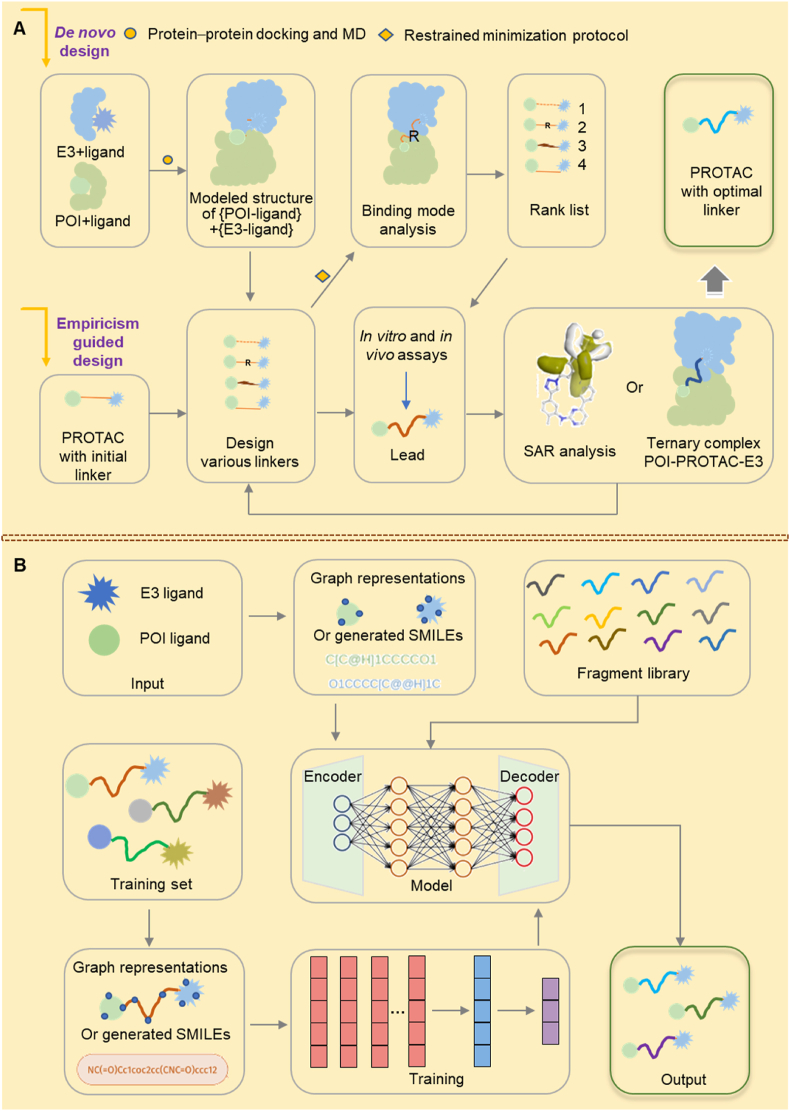

Typically, PROTAC linker design and optimization rely on empirical or computer-aided methods. These methods play a fundamental role in drug development81,147, 148, 149. Initially, researchers design PROTACs based on prior experience and then focus on optimizing the linker in four key areas: 1) adjusting the linker length to achieve an optimal configuration for a specific PROTAC150, 2) modifying the type of linker group to balance the hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties in the PROTAC151, 3) modifying the flexibility of the linker and linkage site, to increase the stability of the ternary complex involving the POI, PROTAC, and E3 ligase120,152, and 4) designing and synthesizing a diverse set of PROTACs with distinct linkers. This can also be accomplished using a computer-aided de novo approach19. The initial step involves determining the binding modes of the POI with its ligand and E3 with its ligand, respectively, using crystallography or molecular docking19. Subsequently, obtaining global protein‒protein docking simulations using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), Rosetta, PatchDock, or other computational software, an ensemble of modeled structures of the POI-ligand and E3-ligand are generated. Following evaluation using molecular dynamics (MD), a reasonably modeled structure is used to analyze the protein‒protein interactions (PPIs) and identify proteins interacting proximal to their ligated pockets. This is followed by the linker design process, where varying linkers are designed to generate a series of POI-PROTAC-E3 conformers. The ternary complex undergoes a restrained minimization protocol to eliminate steric hindrance between the PROTAC and proteins, allowing for the selection of an optimal linker for PROTAC synthesis. The rationality of the designed linker is ultimately verified through in vitro and in vivo experiments153. Additional analysis of the structure‒activity relationship (SAR) and the binding mode of the ternary complex, either through modeling or crystal structure, can guide the optimization of the linker, ultimately leading to the optimal linker (Fig. 3A)154, 155, 156, 157.

Figure 3.

Appropriate design and optimization strategies for PROTAC linkers. (A) A standard protocol for the fundamental strategies of PROTAC linker design and optimization, which encompasses empirical design, de novo design using computational modeling, and further structural optimization through SAR analysis or the ternary complex binding mode of POI-PROTAC-E3. (B) Machine learning-based strategies for PROTAC linker design and optimization, which utilized existing knowledge of PROTAC linkers to train a model for rational PAROTC linker design.

This strategy is widely applicable for linker design and optimization, particularly during initial efforts without knowledge of the binding mode of the ternary complex158,159. However, this approach has certain limitations. One significant disadvantage is the synthesis of PROTACs160,161. Nevertheless, this approach typically necessitates synthesizing multiple PROTACs with various linkers to comprehensively understand the SAR, which can be time-consuming, labor-intensive, and costly155. Another limitation is the accuracy of theoretical predictions, particularly those related to protein‒protein docking, which affects the design of the linker162. Sun et al.130 made a significant discovery in the treatment of breast cancer. Using a SAR investigation aimed at examining various linker lengths and compositions, they created the first PROTAC biodegrading of the protein polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4) that is highly powerful, selective, and effective. This innovation was achieved by conjugating PLK4 ligand to a CRBN ligand thalidomide analogue, using various linkers. Initially, they designed and synthesized PLK4 PROTACs, connecting them with even-carbon chains ranging from 2 to 18 carbon-chain lengths, to determine the optimal range for the linker length. Their results indicated that the biodegradation of PLK4 was maximal when the carbon length of the PROTACs as 4 to 8 carbon atoms. Next, they examined the influence of a rigid linker on biodegradative efficacy, given that an inappropriate linker rigidity produces unfavorable angles that prevent binding with the CRBN protein. They discovered that the angle of the rigid linkers may be efficiently changed by introducing a carbonyl group between the linker and the PLK4 ligand, which increased the binding affinity of PLK4 and significantly increased the efficacy of PLK4 biodegradation. Finally, they developed the first in vivo efficacious PROTAC, SP27, using a linker that had a greater number of conformational constraints. This innovative PROTAC offers a promising candidate for characterizing PLK4-dependent biological functions and treating TRIM37-amplified breast cancer.

3.2. Cutting-edged strategies

In recent years, several cutting-edged design strategies for PROTAC linkers have emerged that primarily use artificial intelligence (AI) technology to improve the accuracy of PROTAC linker design163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169. These methods are based on the utilization of existing knowledge. The general processes involve data collection, feature extraction, selection of suitable machine learning models, model training, validation, and application166. Initially, a comprehensive dataset of known PROTAC linkers is collected, encompassing their structures, efficacies, cellular penetration capabilities, and stability. This dataset is then utilized to train and validate the machine-learning models. Next, the pertinent chemical and physical properties are extracted from the structure of the PROTAC linker which may encompass the types of atoms and bonds, molecular weight, and electrical distribution, among others. Subsequently, suitable machine learning models, such as deep neural network (DNN)170, transformer neural network166, or recurrent neural network (RNN)163 are chosen and trained using the extracted features and known experimental data. By carefully adjusting the model's parameters and optimizing the underlying algorithm, the prediction accuracy and generalization are increased. An independent test dataset is used to evaluate the predictive performance of the trained model. Finally, the trained model is utilized to predict a novel PROTAC linker (Fig. 3B).

The integration of machine learning algorithms into PROTAC linker design enables rapid extraction of patterns from vast datasets, expediting the design process, increasing success rates, minimizing experimental iterations, and mitigating financial expenses171. Nonetheless, this approach possesses certain limitations, such as the caliber and volume of data impact the efficacy and precision of the model. As an instance, Kao et al.170 used cutting-edge techniques to introduce AIMLinker, a deep neural network that facilitates the rapid design and creation of novel PROTAC linkers. AIMLinker accepts two unconnected fragments as inputs and uses an encoder-decoder deep learning architecture to generate the substructures that constitute a novel PROTAC molecule. Subsequently, it conducts postprocessing on compounds that are produced to find possible candidates for drugs. It checks for repeats and ignores structures that contain unwanted substructures or defy basic chemical rules. This streamlined process allows for the timely generation of new small molecules that have strong affinity for binding CRBN-BRD4 and its adaptability for application to other PROTAC targets. Additional machine learning strategies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Innovative models for the design and development of PROTAC linkers.

| Model | Method | Principle | Characteristic | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROTAC-INVENT | Reinforcement learning (RL) | The model is jointly trained using the RL approach, aiming to direct PROTAC structure generation towards predefined 2D and 3D properties. | It can not only generate PROTAC SMILES, but it can also calculate their possible three-dimensional bind conformations in conjunction with POI and E3 protein. | 163 |

| DeLinker | Graph-based deep generative model (Gated Graph Neural Network (GGNN)) | The model combines structural knowledge with machine learning approaches, utilizes two fragments or partial structures, and generates a molecule that incorporates both. | This is the inaugural molecular generative model that incorporates 3D structural information directly into the design process, successfully demonstrating its efficacy and applicability in PROTAC design. | 165 |

| FFLOM | Deep generative model (graph convolutional network (GCN)) | The model typically adjusts the fragment and generation lengths, optimizing the local fragment while preserving the dominant region and its conformation. | During the PROTAC design process, the model not only replicates the experimentally verified baseline molecule but also generates numerous novel structures with superior binding affinity scores. | 167 |

| AIMLinker | Deep learning (deep neural network (DNN)) | The model retrieves structural data from input fragments and creates linkers for their integration. | It can rapidly design and generate linkers to create drug-like PROTACs with improved chemical properties. | 170 |

| Link-INVENT | Reinforcement learning (RNN) | The model takes two molecular subunits with a defined exit vector and a pair of warheads. It then produces a linker and outputs the connected molecule in SMILES format. | The model generates optimal linkers that connect molecular subunits and fulfill various goals, making it easier to use the model in practice for PROTAC design. | 168 |

| 3DLinker | Conditional VAE-based generative model (vector neuron networks) | The model has the ability to predict anchor atoms and generates invariant graphs and equivariant absolute coordinates of linkers given two 3D fragments. | The model has a significantly higher rate of recovering molecular graphs and accurately predicting the 3D coordinates of all atoms. | 164 |

| ShapeLinker | Reinforcement learning (RNN) | The model implements fragment-linking using reinforcement learning on an autoregressive SMILES generator. | The model generates linkers that satisfy relevant 2D and 3D criteria, achieving top-notch results in generating novel linkers under a predefined linker conformation. | 169 |

| DRlinker | Deep reinforcement learning (transformer neural network) | The model manages the linking of fragments by exploring the desired chemical space for novel molecules with anticipated properties. | The model is effective for various tasks, ranging from controlling linker length and logP to optimizing the predicted bioactivity of compounds and addressing various multiobjective challenges. | 166 |

| PROTAC-RL | Reinforcement learning (RL) (transformer neural network) | The model, utilizing generative deep learning, incorporates a robust transformer architecture along with memory-enhanced RL to create highly effective PROTACs. It accepts E3 ligands and warheads as input and generates linker sequences that produce chemically feasible PROTACs with superior properties. | It not only enables the rational design of PROTACs in limited resource settings but also guides the selection of PROTACs with the most favorable pharmacokinetics. | 172 |

| DeepPROTAC | Deep neural network model (graph convolutional network) | In the model, ligand and ligand binding pockets are represented using graphs and fed into GCNs for feature extraction. Linkers are represented using SMILES notation to generate features for rational PROTAC design. | It not only can achieve rational PROTAC design but also can estimate the biodegradation activity of the resulting PROTAC based on the targeted POI and E3. | 173 |

4. Effects of linker characteristics on the biodegradation efficiency of PROTACs

4.1. Linker length affects the formation of ternary complex

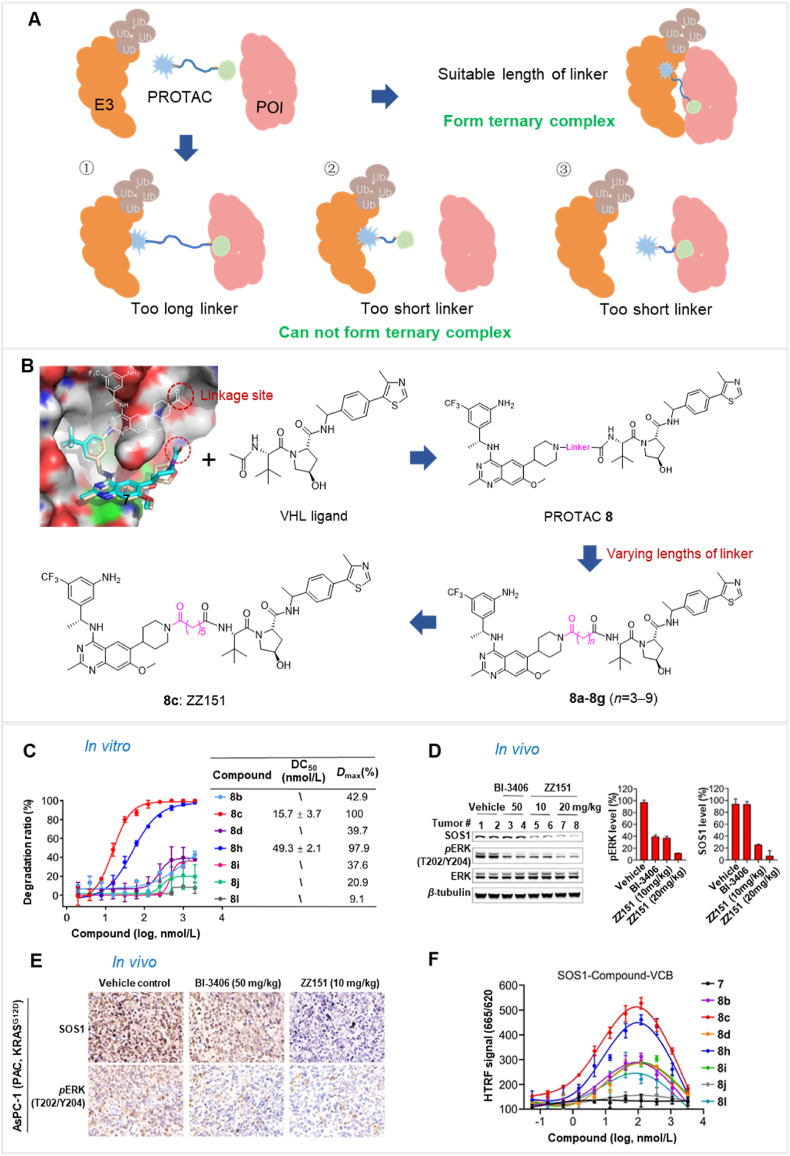

The linker length has a pivotal effect on determining the biodegradation efficacy of PROTACs. It affects the formation of the ternary complex, as illustrated in Fig. 4A68,142,143. The optimal linker length depends on the interaction pattern, distance, and spatial structure of the ternary complex151. Prior studies have shown that an inappropriate linker can significantly decrease PROTAC bioactivity58,174. If the linker is too long, it may weaken the interaction between POI and E3 ligase, decreasing the probability of a stable ternary complex formation. Conversely, a shorter linker may introduce steric hindrance, disrupting ternary complex formation, and decreasing the biodegradation efficacy of PROTAC58,174. Therefore, achieving an optimal linker length is essential to produce maximal interactions between the POI and E3 ligase, leading to effective ubiquitination and biodegradation of the POI.

Figure 4.

The impact of linker length on ternary complex formation. (A) The impact of linker length on the formation of the ternary complex between POI, PROTAC, and E3 is significant. An optimal linker length is essential for facilitating this ternary complex formation. (B) The design strategy for PROTAC 8 primarily focuses on optimizing linker length. (C) PROTAC 8C (ZZ151) exhibits the most potency in terms of biodegradation activity for SOS1. (D) After 21 days of treatment, the expression levels of SOS1 and pERK were quantified in AsPC-1 xenograft pancreatic cancer cells in mice. PROTAC 8C (ZZ151) at 10 and 20 mg/kg, BI-3406 (SOS1 inhibitor) at 50 mg/kg, and vehicle (DMSO) were administered. PROTAC 8C (ZZ151) was most effective in reducing the expression levels of SOS1 and pERK. (E) An immunohistochemistry assay was conducted to assess SOS1 and pERK levels in AsPC-1 xenograft tumors. (F) Minor modifications to the linker can significantly influence the formation of the ternary complex between SOS1, PROTAC, and VCB, as determined by HTRF assay results. The lead biodegradative compound, PROTAC 8c (ZZ151), exhibited the greatest maximal ternary complex formation. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 111. Copyright©2023 American Chemical Society (Supporting Information Fig. S1).

To demonstrate how linker length affects PROTAC efficiency, a study used the PROTAC ZZ151, which promotes the biodegradation of the protein, Son of Sevenless Homologue 1 (SOS1)111. SOS1 plays a crucial role in the activation of the oncogene, Kirsten ras (KRAS), making it a promising target for KRAS-induced cancer treatment175,176. Researchers have intended to develop effective inhibitors or complexes that biodegrade proteins for KRAS-driven cancers by regulating SOS1177. One study focused on determining the relationship between linker length and PROTAC efficacy, leading to the discovery of the PROTAC ZZ151111. Initially, inhibitor-based SOS1 PROTACs were developed that sequestered the E3 ligase VHL (von Hippel-Lindau)178. The initial SOS1 inhibitor, analog 7179, with an N-acetyl piperidine group, was an appropriate attachment site for the VHL ligand. Alkyl-based linkers were used to connect the SOS1 ligand, 7, to the VHL ligand, generating a series of PROTACs (8a‒g) containing 3 to 9 methylene units (Fig. 4B). The effect of PROTAC efficacy was determined by varying the linker length. The efficacy of PROTACs 8 in inducing the biodegradation of SOS1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells (NCI-H358) was evaluated. The results indicated a significant correlation between the length of the linker and the efficacy of the PROTACs 8a‒g, containing 3 to 9 methylene units. Among these, PROTAC 8c (ZZ151), with a linker that contained five methylene units, had the most potent activity, producing complete SOS1 biodegradation, at a half-maximal degradation concentration (DC50) of 15.7 μmol/L and a maximal biodegradation efficacy (Dmax) of 100% (Fig. 4C). In mice xenografted KRASG12D-mutant cancer cells, the PROTAC ZZ151 produced a dose-dependent decrease in SOS1 biodegradation (Fig. 4D), producing corresponding decrease in the levels of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) (Fig. 4E). In contrast, PROTACs 8b and 8d, containing four and six methylene units, respectively, were less potent than 8C. The relationship between the biodegradative efficacy of PROTACs for SOS1 and the ternary complex POI-PROTAC-E3 formation was determined using a homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) assay. PROTAC ZZ151 produced the highest HTRF signal and ternary complex formation. Other compounds with lower biodegradation efficacies produced weaker HTRF signals, indicating a lower propensity for ternary complex formation (Fig. 4F). In summary, the highly potent PROTAC ZZ151 was developed using meticulous linker length optimization. This compound effectively and rapidly produced the biodegradation of SOS1, indicating that it might represent a therapeutic approach to treating KRAS-driven cancers.

An analysis of the above examples highlights the significant effect of linker length on the biodegradation activity of PROTACs. Indeed, small variations in length produced significant alterations in efficacy. For example, this study identified an optimal 5-carbon chain length, as shorter or longer chains produced a lower magnitude of biodegradation efficacy. When the carbon chain was increased by 7 methylene units, the biodegradation efficacy was increased, and the corresponding HTRF signal was slightly weaker than that for an 8-carbon chain. This may be due to differences in spatial conformations of the linker, which can be determined by examining the crystal structure of the ternary complex. Therefore, in the design of PROTACs, careful consideration of linker length is paramount. A reasonable range of linker lengths should be established, typically spanning 5 to 15 carbon chain lengths. A detailed evaluation is essential and varying the number of carbon atoms one at a time is required to accurately identify optimal lengths. The length of a linker is intricately linked to ternary complex formation and, ultimately, biodegradation efficacy. Consequently, optimizing linker length is essential for the efficient identification of highly efficacious PROTACs.

4.2. The group type of the linker affects the cell permeability of the PROTACs

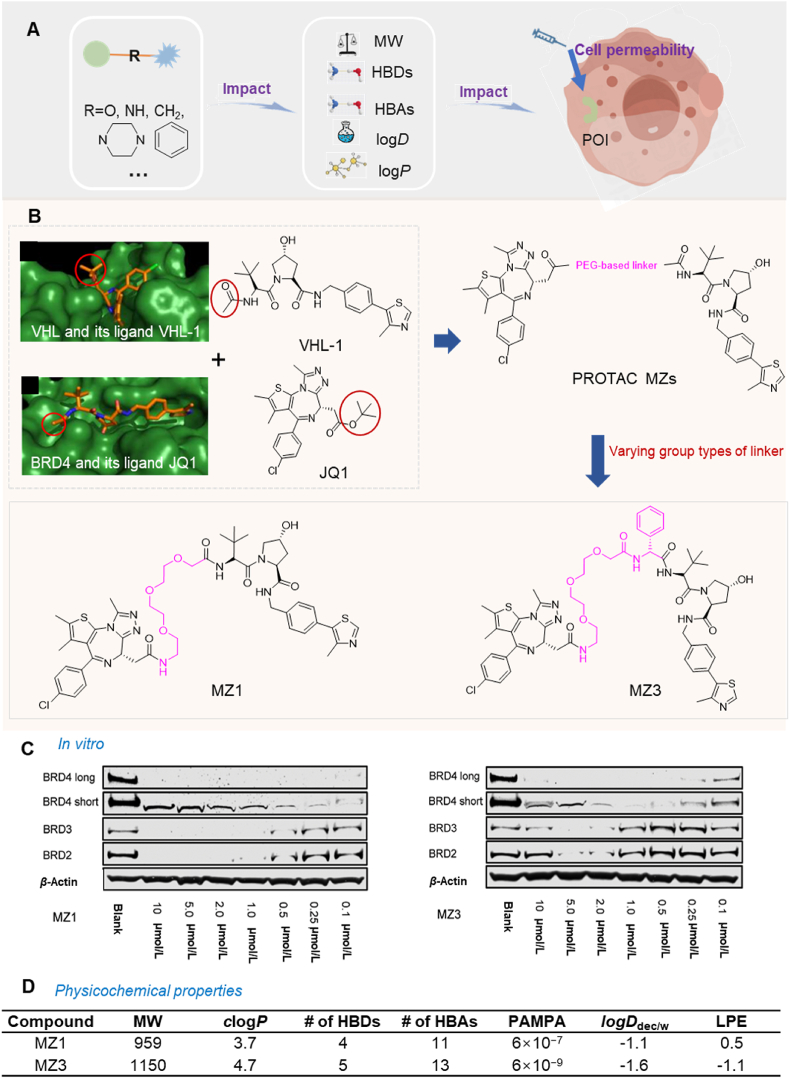

The group type of linker between the binding and recruiting moieties in PROTACs significantly affects their biodegradative efficacy105,180, 181, 182. This is due to the linker's chemical composition, which directly affects the physicochemical properties of the PROTAC, including its molecular weight (MW), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) and acceptors (HBAs), octanol‒water partition coefficients (clogP), hydrocarbon–water partition coefficient (logDdec/w), and solubility149,180. These factors, in turn, significantly affect the PROTAC's cell permeability (Fig. 5A)183. For example, as the MW increases, cell permeability generally decreases184. When the MW exceeds 1000 Da, there is a significant decrease in cellular permeability185,186. Furthermore, PROTACs with fewer HBDs and HBAs have a higher magnitude of cell permeability. However, introducing a solvent-exposed HBD can decrease cell permeability187. The lipophilic permeability efficiency (LPE) measures how well a PROTAC permeates a cell membrane through passive diffusion, at a specific lipophilicity level. A decrease in LPE results in lower cell permeability188. Therefore, selecting the appropriate group type of linker is crucial for optimizing the PROTAC's physicochemical features, which can significantly impact its cell membrane permeability.

Figure 5.

The linker group type's impact on PROTAC cell permeability. (A) The linker group type significantly impacts the cell permeability of PROTAC. This effect is primarily due to its influence on the physicochemical properties of PROTAC, ultimately determining its cell permeability. (B) The design strategy for PROTAC MZs primarily focuses on the insertion of different groups into the linker to alter the physicochemical properties of PROTAC. (C) HeLa cells incubated with different concentrations of MZ1 (left) and MZ3 (right) demonstrate selective biodegradation of BRD4. MZ1 is the most efficacious compound, removing over 90% of all BET proteins even at a concentration of 1 μmol/L. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 27. Copyright ©2015 American Chemical Society (Supporting Information Fig. S2). (D) The physicochemical properties of PROTAC MZs indicate that inserting different groups into the linker of PROTAC can significantly influence its physicochemical properties, leading to notable differences in cell permeability. MZ1, with an MW < 1000 Da, fewer solvent-exposed HBD and HBA, suitable clogP and logDdec/w, and LPE value, demonstrate higher cell permeability.

To illustrate the effect of the linker group type on cell permeability, we compared two PROTACs, MZ1 and MZ327,68, which target the bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) protein. BET regulates the expression of certain genes and it has been suggested that it may be a therapeutic target for various diseases189, 190, 191, 192. The PROTACs were developed based on a comprehensive study examining the effect of the linker group type on PROTAC efficacy27,68. The MZ series, composed of the BRD4 inhibitor, JQ1193, and the VHL binder, VHL-1194, used distinct linkers to join the two compounds. The connection points of the linkers were determined by analyzing the crystal structures of BRD4 complexed with JQ1 and VHL with VHL-1. The solvent-exposed t-butyl ester of JQ1 and the acetyl methyl of VHL-1 were suitable for linker attachment. MZ1 contained a PEG-based linker with three ethylene glycol units, whereas MZ3 used the same linker with an additional phenylalanine group between the ethylene glycol units and VHL-1 (Fig. 5B). The intracellular assay results indicated that MZ1, at 1 μmol/L, was the most efficacious compound, removing over 90% of BET proteins in HeLa cells. MZ3 produced concentration-dependent biodegradation of BET proteins, achieving efficacy in HeLa cells at concentrations from 0.1 to 10 μmol/L (Fig. 5C). Permeability experiments indicated that MZ1 had significantly higher permeability (Pe = 6 × 10−7 cm/s), compared to MZ3 (Pe = 6 × 10−9 cm/s), primarily due to their distinct physicochemical properties. MZ1 had optimal physicochemical properties, including an MW of 959 Da, clogP of 3.7, HBDs of 4, HBAs of 11, logDdec/w of −1.1, and LPE of 0.5. These properties contributed to its greater cell permeability and biodegradative efficacy. In contrast, introducing an additional phenylalanine moiety into the linker of MZ1, which produced MZ3 resulted in a MW exceeding 1000 Da and an increase in the solvent-exposed HBD count, which decreased cell permeability. Furthermore, modifications to the clogP and logDdec/w values caused a significant decrease in the LPE value, further compromising cellular permeability (Fig. 5D). Collectively, these findings emphasize the critical role of linker group types in determining the physicochemical properties of PROTACs and their subsequent effect on cell permeability and biodegradative efficacy.

Obtaining a high magnitude of cell permeability and oral bioavailability for PROTACs represents a significant challenge, as these values are beyond the constraints defined by Lipinski's rule of five195, approaching or even exceeding the outer limits of the oral beyond the rule of five (bRo5)196. Previous studies have shown that PROTACs, utilizing CRBN and VHL ligands, had median molecular weights of roughly 900 and 1000 Da, respectively, and have rotatable bond (ROB) counts of 20–30. The physicochemical characteristics of these PROTACs are similar to those for orally absorbed medications, as indicated by clogP values of 4–6 and HBD counts of 3–4. Notably, lipophilicities and HBD counts produce a greater effect on permeability compared to MW197,198. Differences in HBD counts and clogP values within a series of PROTACs produce significant disparities in cell permeability. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of PROTAC permeability across a broader clogP spectrum can provide a lipophilicity profile that can guide the development of PROTACs that have increased cell permeability.

4.3. Linker flexibility affects the stability of the ternary complex

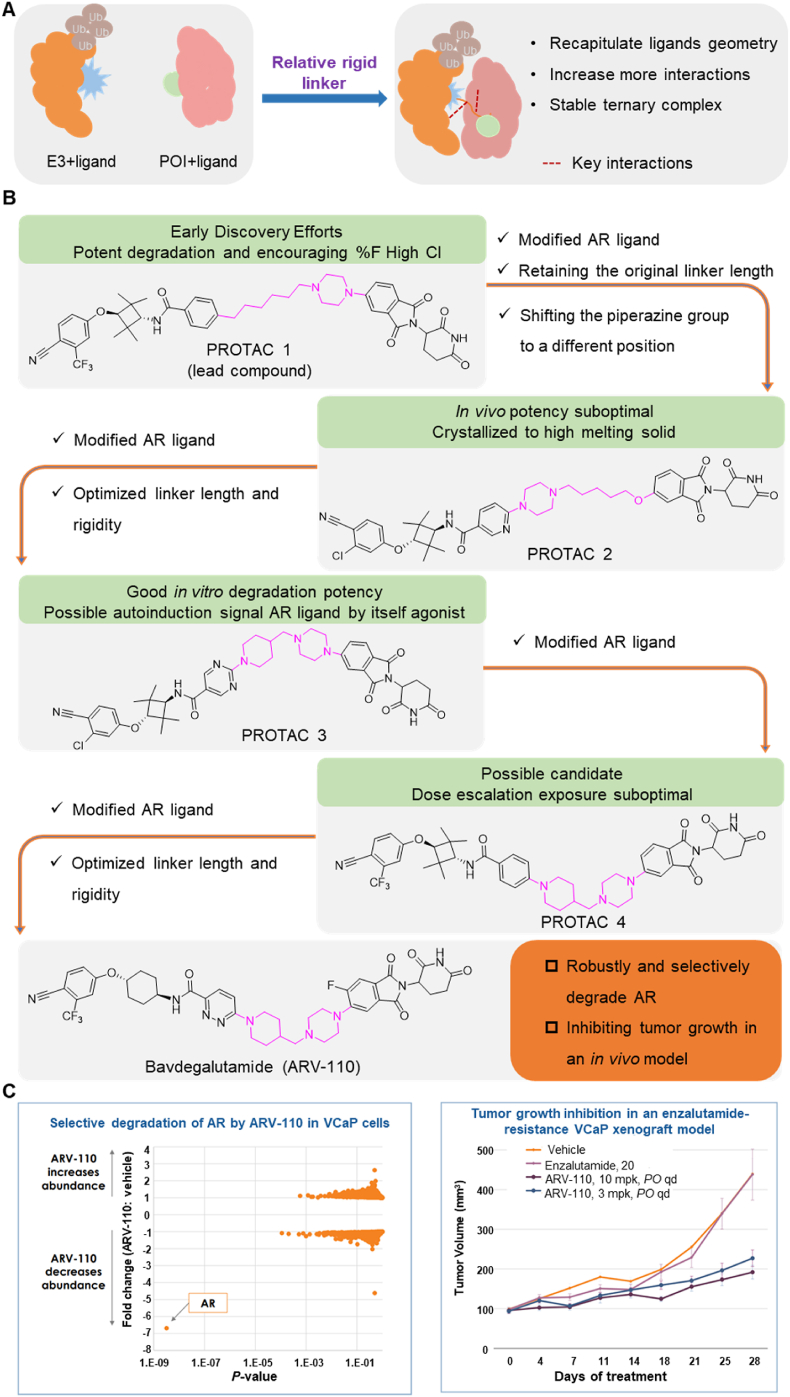

The flexibility of the linker is a critical factor in determining the biodegradative efficacy of PROTACs by modifying the stability of the ternary complex (Fig. 6A)6,29,64. It is essential to consider linker flexibility during PROTAC design85. A linker with significant conformational flexibility can enhance interactions between the PROTAC, POI, and E3 proteins, preventing stable binding at a fixed interface85. Conversely, introducing rigid groups into a flexible linker can enhance stiffness and replicate the original geometry of the PROTAC, leading to new interactions and increased stability of the ternary complex29. Therefore, it is beneficial to choose linkers with a certain degree of rigidity for use in PROTACs as they aid in stabilizing the POI-PROTAC-E3 complex, ultimately enhancing biodegradative efficacy.

Figure 6.

The effect of linker flexibility on PROTAC stability. (A) Linker flexibility has an impact on PROTAC stability. A more stable ternary complex enhances PROTAC efficacy. (B) The design approach for the discovery of PROTAC ARV-110 emphasizes linker flexibility and AR ligand optimization. (C) ARV-110 selectivity was evaluated by proteomics. After treating VCaP cells with 10 nmol/L ARV-110 for 8 h, AR was the only protein among nearly 4000 proteins. (D) Daily oral administration of ARV-110 significantly inhibited tumor growth. A 10 mpk dose resulted in 70% tumor growth inhibition.

In the following section, we will discuss the optimization process that was used for the PROTAC, Bavdegalutamide (ARV-110), and the impact of linker rigidity on the magnitude of the biodegradation of AR. Prostate cancer, which ranks second in frequency among cancers in males, is characterized by its dependence on abnormal AR signaling199. Chronic exposure to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) often produces castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), where the AR is still a crucial oncogenic driver200. Clinical research has reported the therapeutic advantages of AR degraders for patients with colorectal cancer. ARV-110, developed by Arvinas, was the first PROTAC to get into clinical trials with an emphasis on AR, specifically for the treatment of metastatic CRPC98. This PROTAC represents a prime example of the optimization process and the significance of linker rigidity in increasing AR biodegradation efficacy.

In the early design phase, the researchers evaluated various E3 recruiting ligands and AR binders. They ultimately selected PROTAC 1 as the lead compound for further structural optimization. PROTAC 1 consists of an AR ligand and the CRBN ligand, thalidomide, connected via an alkyl chain containing a piperazine ring. The initial step in optimization involved modifying the AR ligand of PROTAC 1. The trifluoromethyl group was replaced with chlorine atoms and a pyridinyl ring replaced the phenyl ring to increase the likelihood of hydrogen bond formation. The piperazine groups in the linker were directly connected to the AR ligand, while maintaining the length of the linker, yielding PROTAC 2. This compound could represent a potential candidate for further optimization. The next phase of optimization involved modifying the AR ligand. The pyridinyl group was replaced with a pyrimidine ring, introducing a piperidyl group that decreased the flexibility of the linker and this increased its hydrogen bonding capacity, yielding PROTAC 3, which had significant biodegradation efficacy in vitro. The addition of piperidyl to the linker limited the rigidity of the PROTAC, thus allowing for the original binding mode of the AR ligand, AR, thalidomide, and E3, thereby producing biodegradation efficacy. Subsequently, PROTAC 4 was developed by replacing the pyrimidine ring in the AR ligand with a phenyl ring, which decreased the number of hydrogen bond donors. Finally, the substituted cyclobutane in the AR ligand was replaced with cyclohexane and this modification increased the PROTAC's rigidity but decreased its TPSA. Finally, the replacement of the phenyl group with pyridazine increased the hydrogen bonding interactions and retained the unchanged linker, yielding ARV-110 (Fig. 6B)201. The oral administration of ARV-110 was efficacious in producing the biodegradation of the wild type and the antiandrogen therapy-induced mutant forms of AR. ARV-110 is capable of biodegrading 95%–98% of AR among various prostate cancer cells. ARV-110 also decreases tumor growth by 70%–100% in drug-resistant mouse models (Fig. 6C)202. Preliminary data from Phase I clinical trials indicated that ARV-110 has satisfactory safety and tolerability profiles.

The researchers developing ARV-110 initially focused on the linker segment. They evaluated various linker lengths, increased linker rigidity, and modified the AR ligand to obtain ARV-110. The examination of the crystal structure of CRBN and thalidomide indicated that the isoindoline of thalidomide, towards the solvent-exposed region, created a stacking interaction with the neighboring amino acids of CRBN203. This observation suggested that a rigid linker connected to this isoindoline would increase thalidomide's binding interaction with CRBN, by maintaining its original binding mode. Furthermore, the aromatic ring of the AR ligand, which was exposed to the solvent region, formed a stacking interaction with Thr877 in the AR protein204. The rigid linker component, directly connected to this aromatic ring, appeared to increase the stability of the AR ligand's binding mode within AR. Based on the interaction modes of the AR ligand with AR and thalidomide with CRBN, one could conclude that the rigid linker is essential for maintaining their binding modes, increasing the stability of the ternary complex, producing the biodegradation efficacy of ARV-110. During the design of the linker, it is crucial that the linker maintains a rigid structure when POI and E3 ligands accumulate in the solvent-exposed region and form engaging in stacking interactions. By maintaining a rigid linker, it may be easier to ensure the stability of the ternary complex, ultimately yielding the biodegradation efficacy of PROTACs.

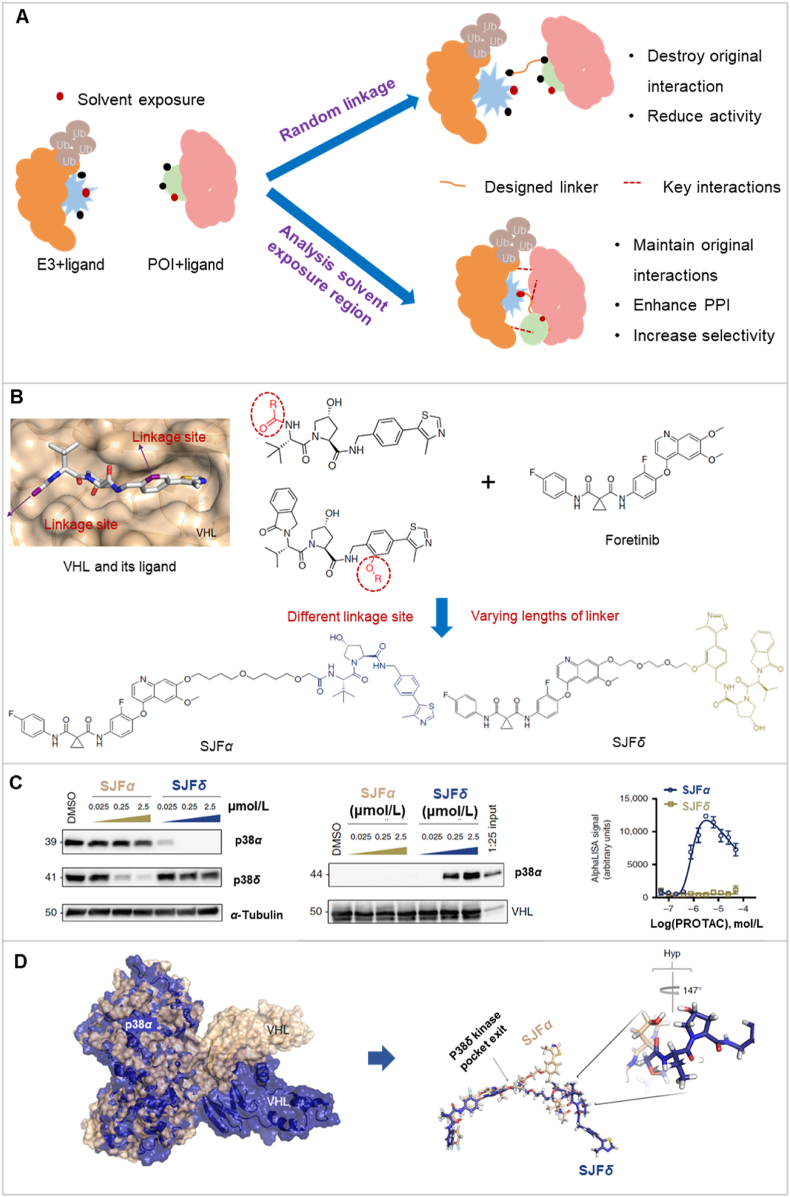

4.4. The linkage site of the linker affects the protein–protein interactions

The linkage site of the linker plays a significant role in determining the biodegradative efficacy of PROTACs by affecting the interaction of POI and E3 (Fig. 7A)144, 145, 146. The optimization of PROTAC linkers often involves identifying the most favorable site for structural derivatization, thereby ensuring that the maximal binding affinity is retained205. This selection process typically involves analyzing the solvent-exposed regions of the protein‒ligand interaction interfaces145,146. When a PROTAC linker cannot be extended, it limits the POI ubiquitination efficacy of the E3 ligase206. By introducing an optimal linker linkage in a solvent exposure region, protein‒protein interactions can be maximized, while preserving the original ligand interactions with the POI or E3 ligase205. Furthermore, an appropriate linker can establish alternative interactions with the POI, increasing ternary complex stability1. Overall, selecting the linkage site in the PROTAC linker is a crucial decision that can directly impact PROTAC's biodegradative efficacy and selectivity.

Figure 7.

The effect of linkage site on protein‒protein interactions. (A) The linkage site of the linker is essential for protein‒protein interaction (PPI). An increase in PPI formation enhances the biodegradation efficiency. (B) The design approach for PROTAC SJFα and SJFδ emphasizes the optimization of the linkage site. (C) PROTAC SJFα preferentially biodegrades p38α, while SJFδ preferentially biodegrades p38δ. (D) Immunoprecipitation of GST-tagged VBC is only feasible when p38α is incubated with PROTAC SJFα (left). The AlphaLISA assay indicates that p38α, SJFα, and VHL form a substantial ternary complex; p38α, SJFδ, and VHL do not create a ternary complex (right). Reprinted with permission from Ref. 147. Copyright ©2019 Nature Communication (Supporting Information Fig. S3). (E) Molecular dynamics simulations show distinct PPI contacts between p38δ and VHL depending on whether they are recruited by SJFδ or SJFα.

We will discuss the discovery of PROTACs, SJFα, and SJFδ147, which can produce the biodegradation of the p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). This discussion will illustrate the significance of the linkage site of the linker on the efficacy of PROTACs. The p38 MAPK pathway is a crucial regulator of pro-inflammatory cytokines biosynthesis at the transcriptional and translational levels. Thus, modulation of this pathway by pharmacological compounds could represent treatment for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases207,208. The p38 MAPK kinases, consisting of α, β, γ, and δ isoforms, are activated by environmental stress and cytokines. These kinases exhibit distinct expression patterns in different tissues208,209. The PROTACs, SJFα and SJFδ, were discovered based on foretinib22, a kinase inhibitor, and the VHL protein serving as an E3 ligase. The linkage site connecting the VHL ligand and foretinib was meticulously optimized to increase their biodegradative efficacy for the related kinase isoforms147. The authors, through the crystal structure of VHL and its ligand, identified two distinct groups in the solvent-exposure region that could serve as linkage sites67,210. They synthesized the “amide series” of PROTACs, using the known amide of VHL ligand as the linkage point for the linker to foretinib67. In contrast, the “phenyl series” of PROTACs used an under-explored phenyl group as the attachment site210. Both series utilized the same phenyl ether of foretinib as the linkage site, connecting it with different lengths of linkers (Fig. 7B). In the “amide series”, the PROTAC with a 13-atom linker (SJFα) was highly selective in biodegrading p38α (Dmax = 97.4%, DC50 = 7.16 nmol/L). However, it was significantly less efficacious in biodegrading p38δ (Dmax = 18%, DC50 = 299 nmol/L). In contrast, in the “phenyl series”, decreasing the linker length to 10 atoms yielded the PROTAC SJFδ, which selectively biodegraded p38δ (Dmax = 99.41%, DC50 = 46.17 nmol/L), without biodegradation p38α, β, or γ. The foretinib-based PROTAC had a weak binary affinity for p38α. Nonetheless, the obstacle was surmounted through the collaborative interactions within VHL and p38α, ultimately leading to a heightened affinity of SJFα for p38α with VHL22. Similarly, the affinity of SJFδ for p38δ and VHL is 436 nmol/L, representing a tenfold increase, compared to the affinity of the VHL-PROTAC complex. The ternary complex has a higher binding capacity than the binary complex due to the extra PPIs within VHL, p38α or p38δ, and SJFα or SJFδ, respectively. Furthermore, the affinity of the p38δ-SJFα-VHL and p38δ-SJFδ-VHL complexes was also determined, and the results indicated that the SJFδ complex is approximately 3-fold stronger than the SJFα complex (Fig. 7C). To determine the structural basis for the variation in ternary affinity among the p38δ-SJFα-VHL and p38δ-SJFδ-VHL complexes, molecular dynamics simulations were conducted. The results indicated that with SJFα, the interaction between Arg108 of VHL and Lys220, Thr221 of p38δ was unfavorable. In contrast, with SJFδ, Arg108 of VHL and Glu49, Glu160 of p38δ produced a favorable stabilization of the ternary complex (Fig. 7D). These findings suggest that the linkage site and linker length influenced the formation of distinct ternary interfaces, leading to inherent differences in ternary complex affinity. These differences ultimately enable selective biodegradation by different PROTACs.

The objective of the p38 PROTACs study was to create isoform inhibitors of p38 MAPKs by utilizing a single E3 ligand and a single POI ligand. By manipulating the linker design of PROTACs and producing a distinct orientation of the recruited E3 ligand while maintaining a consistent warhead, this approach allows for the selective biodegradation of a specific isoform of a protein family147. This study highlights the significance of linker linkage site selection in PROTAC design. Typically, linker design involves selecting solvent-exposed regions based on crystal structures. However, it is also essential to consider the ease of synthesizing linkers at these sites. For complexes without crystal structures, molecular docking is often employed to determine the binding mechanism of POI with its ligand, as well as E3 and its ligand, thereby aiding in the selection of linker linkage sites. In conclusion, the selection of linker sites is crucial in PROTAC design, as it affects the ternary complex stability by influencing the interactions among POI and E3, ultimately influencing the degradation activity of PROTACs.

5. Conclusions

In this review, we have summarized the types of PROTAC linkers, the design and optimization strategies used, and the impact of linker characteristics on PROTAC efficacy. As previously mentioned, PROTAC linkers can be broadly classified into two groups: flexible linkers and relatively rigid linkers. Flexible linkers, which are prevalent in PROTAC design, often use a long and flexible structure29, 30, 31. However, this design can increase the susceptibility to oxidative metabolism in vivo211. In contrast, relatively rigid linkers have been less frequently used due to limitations in synthesis technology within the PROTAC field37. Nonetheless, cycloalkane-based linkers, especially the inclusion of piperazine and piperidine components, are used as they increase the solubility and stability of the ternary complex. Triazole-based linkers are another frequently used rigid linkers, due to the advent of the “click” chemical reaction, using the copper-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction, which offers high compatibility with different functional groups and a consistent reaction rate24,35,36. Another type of linker, photo-controlled PROTAC linkers, such as photo-switchable PROTAC linkers, use azo fragments rather than alkyl or polyether fragments, causing the resulting PROTACs to undergo reversible photoisomerization when exposed to specific wavelengths of light41. This makes it possible to precisely and reciprocally regulate the rate of PROTAC biodegradation. Furthermore, researchers have developed different linker optimization strategies. The application of AI in PROTAC linker design has significantly improved the accuracy and efficiency of linker optimization171. By leveraging machine learning frameworks, researchers have gained insights into the structural, physical, and chemical properties of PORTAC linkers. These insights have been translated into practical applications, leading to more accurate PROTAC linker designs. Advanced AI techniques, such as deep learning and reinforcement learning, are expected to further enhance PROTAC linker design in the future63,162,212,213. Furthermore, the linker's four key characteristics: length, group type, flexibility and linkage site, were examined based on case studies. These characteristics are essential for influencing the stability of the ternary complex POI-PROTAC-E3, the cell permeability of PROTACs, the creation of the ternary complex, and the interaction between POI and E3. Consequently, they significantly affect the biodegradation efficacy of PROTACs214.

Currently, there is a lack of precise quantitative descriptions for these characteristics. Based on available data from reported and clinically tested PROTACs, the typical length of atoms within the linker chain ranges between 5 and 15 atoms. Although a longer chain length can diminish activity due to increased entropy, this effect is generally less significant than the effect of a shorter molecular distance between ligand ends caused by a shorter chain length. Consequently, in the initial stages of PROTAC design, a slightly longer linker chain is often chosen. To increase the formation of ternary complexes, a flexible linker is chosen, allowing the PROTAC to adopt a suitable angle that facilitates the stable assembly of ternary complexes23. Various chemical groups, including amino, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups, can be introduced in the linker to increase the chemical diversity of PROTAC and its ability to traverse cell membranes27. To facilitate subsequent chemical modification and optimization, it is essential for the linker to possess reactive functional groups or other modifiable sites. When selecting a linkage site, it is essential to consider the binding mode between the POI and ligand or E3 and ligand. The solvent-exposed region should be chosen, as it provides easy access for connecting groups214. Overall, with appropriate linker optimization, a wide range of linkers can be designed to produce greater PROTAC potency. Additional linker characteristics will be discussed in future studies. Nevertheless, our primary focus remains on rationally optimizing the linker characteristics to enhance the biodegradative efficacy of the PROTACS.

Although optimizing the length, group type, flexibility and the linkage site of the linker can increase the efficacy of PROTACs, several challenges must be overcome. Firstly, the structural complexity and diversity of PROTACs hinder the establishment of a clear structure–activity relationship215. To address this issue, exploring the optimal linker characteristics for a specific biodegradation system could facilitate the rapid identification of more efficacious PROTACs. Secondly, the physicochemical properties of the PROTACs often deviate from the classical “rule of five”196, necessitating the investigation of drug-likeness rules tailored to PROTACs, to minimize the likelihood of designing PROTACs with poor pharmacokinetic profiles. Thirdly, purification and low yields, due to their large molecular weight and intricate structure, pose challenges in PROTAC synthesis and optimization37. Therefore, the development of advanced synthetic techniques specific to PROTACs is essential to access a broader range of structural types. Finally, the large size of the ternary complex, consisting of POI-PROTAC-E3, can make crystal structure determination difficult206. To address this, the development of advanced crystallographic techniques or more accurate computational simulation methods is necessary to gain insights for further optimization. We believe that addressing these issues will significantly enhance the progress of PROTAC research. We anticipate that this study will prove to be an invaluable reference for further developments in the field of PROTAC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32125033, 32260688, China), Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project for Overseas Talents in Guizhou Province (No. [2022]03, China), Specific Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou University (No. [2022]42, China), and the Central Government Guides Local Science and Technology Development Fund Projects (Qiankehezhongyindi (2023) 001, China).

Author contributions

Yawen Dong conceived the idea and drafted the manuscript. Tingting Ma, Ting Xu, Zhangyan Feng, Yonggui Li, and Lingling Song contributed by creating representations of published PROTACs. Yawen Dong, Xiaojun Yao, Charles R. Ashby Jr., and Ge-Fei Hao reviewed and refined the manuscript meticulously before submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2024.04.007.

Contributor Information

Xiaojun Yao, Email: xjyao@mpu.edu.mo.

Charles R. Ashby, Jr, Email: cnsratdoc@optonline.net.

Ge-Fei Hao, Email: gefei_hao@foxmail.com.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supporting Information to this article.

References

- 1.Chen Y., Tandon I., Heelan W., Wang Y., Tang W., Hu Q. Proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) delivery system: advancing protein degraders towards clinical translation. Chem Soc Rev. 2022;51:5330–5350. doi: 10.1039/d1cs00762a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirnomas D., Hornberger K.R., Crews C.M. Protein degraders enter the clinic— new approach to cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:265–278. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekes M., Langley D.R., Crews C.M. PROTAC targeted protein degraders: the past is prologue. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21:181–200. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00371-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X., Song Y. Proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) for targeted protein degradation and cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:50. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00885-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong L., Li Y., Xiong L., Wang W., Wu M., Yuan T., et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2021;6:201. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00572-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zorba A., Nguyen C., Xu Y., Starr J., Borzilleri K., Smith J., et al. Delineating the role of cooperativity in the design of potent PROTACs for BTK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803662115. E7285–de7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toure M., Crews C. Small–molecule PROTACS: new approaches to protein degradation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:1966–1973. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun X., Gao H., Yang Y., He M., Wu Y., Song Y., et al. PROTACs: great opportunities for academia and industry. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2019;4:64. doi: 10.1038/s41392-019-0101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ottis P., Crews C.M. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras: induced protein degradation as a therapeutic strategy. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:892–898. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b01068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshaies R.J. Protein degradation: prime time for PROTACs. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:634–635. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun D., Zhang J., Dong G., He S., Sheng C. Blocking non-enzymatic functions by PROTAC-mediated targeted protein degradation. J Med Chem. 2022;65:14276–14288. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu M., Liu T., Jiao Q., Ji J., Tao M., Liu Y., et al. Discovery of a Keap1-dependent peptide PROTAC to knockdown Tau by ubiquitination‒proteasome degradation pathway. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;146:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burslem G.M., Song J., Chen X., Hines J., Crews C.M. Enhancing antiproliferative activity and selectivity of a FLT-3 inhibitor by proteolysis targeting chimera conversion. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:16428–16432. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X., Yao Y., Wu F., Song Y. A proteolysis-targeting chimera molecule selectively degrades ENL and inhibits malignant gene expression and tumor growth. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:41. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01258-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu S., Cui D., Chen X., Xiong X., Zhao Y. PROTACs: an emerging targeting technique for protein degradation in drug discovery. Bioessays. 2018;40 doi: 10.1002/bies.201700247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu T.T., Gao N., Li Q.Q., Chen P.G., Yang X.F., Chen Y.X., et al. Specific knockdown of endogenous Tau protein by peptide-directed ubiquitin–proteasome degradation. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao L., Zhao J., Zhong K., Tong A., Jia D. Targeted protein degradation: mechanisms, strategies and application. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2022;7:113. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00966-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cyrus K., Wehenkel M., Choi E.Y., Han H.J., Lee H., Swanson H., et al. Impact of linker length on the activity of PROTACs. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:359–364. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00074d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai A.C., Toure M., Hellerschmied D., Salami J., Jaime-Figueroa S., Ko E., et al. Modular PROTAC design for the degradation of oncogenic BCR-ABL. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:807–810. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He S., Dong G., Cheng J., Wu Y., Sheng C. Strategies for designing proteolysis targeting chimaeras (PROTACs) Med Res Rev. 2022;42:1280–1342. doi: 10.1002/med.21877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines J., Lartigue S., Dong H., Qian Y., Crews C.M. MDM2-recruiting PROTAC offers superior, synergistic antiproliferative activity via simultaneous degradation of BRD4 and stabilization of p53. Cancer Res. 2019;79:251–262. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bondeson D.P., Smith B.E., Burslem G.M., Buhimschi A.D., Hines J., Jaime-Figueroa S., et al. Lessons in PROTAC design from selective degradation with a promiscuous warhead. Cell Chem Biol. 2018;25:78–87.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bemis T.A., La Clair J.J., Burkart M.D. Unraveling the role of linker design in proteolysis targeting chimeras. J Med Chem. 2021;64:8042–8052. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wurz R.P., Dellamaggiore K., Dou H., Javier N., Lo M.C., McCarter J.D., et al. A "click chemistry platform" for the rapid synthesis of bispecific molecules for inducing protein degradation. J Med Chem. 2018;61:453–461. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han X., Wang C., Qin C., Xiang W., Fernandez-Salas E., Yang C.Y., et al. Discovery of ARD-69 as a highly potent proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) degrader of androgen receptor (AR) for the treatment of prostate cancer. J Med Chem. 2019;62:941–964. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farnaby W., Koegl M., Roy M.J., Whitworth C., Diers E., Trainor N., et al. BAF complex vulnerabilities in cancer demonstrated via structure-based PROTAC design. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15:672–680. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zengerle M., Chan K.H., Ciulli A. Selective small molecule induced degradation of the BET bromodomain protein BRD4. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:1770–1777. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakamoto K.M., Kim K.B., Kumagai A., Mercurio F., Crews C.M., Deshaies R.J. Protacs: chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1-Cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8554–8559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141230798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weerakoon D., Carbajo R.J., De Maria L., Tyrchan C., Zhao H. Impact of PROTAC linker plasticity on the solution conformations and dissociation of the ternary complex. J Chem Inf Model. 2022;62:340–349. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c01036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneekloth J.S., Jr., Fonseca F.N., Koldobskiy M., Mandal A., Deshaies R., Sakamoto K., et al. Chemical genetic control of protein levels: selective in vivo targeted degradation. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3748–3754. doi: 10.1021/ja039025z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee H., Puppala D., Choi E.Y., Swanson H., Kim K.B. Targeted degradation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by the PROTAC approach: a useful chemical genetic tool. Chembiochem. 2007;8:2058–2062. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winter G.E., Buckley D.L., Paulk J., Roberts J.M., Souza A., Dhe-Paganon S., et al. Drug development. Phthalimide conjugation as a strategy for in vivo target protein degradation. Science. 2015;348:1376–1381. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raina K., Lu J., Qian Y., Altieri M., Gordon D., Rossi A.M., et al. PROTAC-induced BET protein degradation as a therapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:7124–7129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521738113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Y., Pu C., Fu Y., Dong G., Huang M., Sheng C., et al. NAMPT-targeting PROTAC promotes antitumor immunity via suppressing myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:2859–2868. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henning R.K., Varghese J.O., Das S., Nag A., Tang G., Tang K., et al. Degradation of Akt using protein-catalyzed capture agents. J Pept Sci. 2016;22:196–200. doi: 10.1002/psc.2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]