Abstract

Background

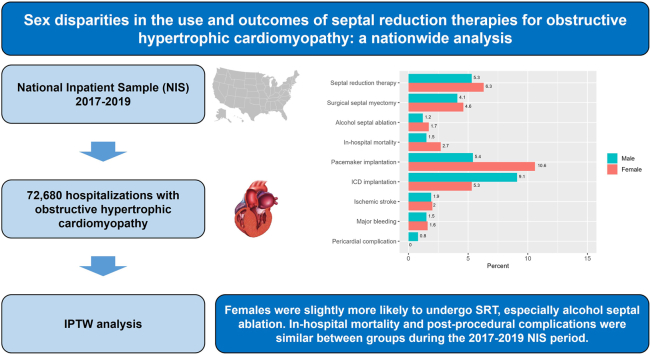

Data are limited that examine potential sex-based disparities in the utilization and complications of septal reduction therapy (SRT) in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Our aim was to assess the use and in-hospital outcomes of SRT, according to sex. We performed a retrospective cohort study using the 2017-2019 National Inpatient Sample database. Adult patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy were identified.

Methods

We assessed the use of SRT (surgical septal myectomy and alcohol septal ablation), according to sex. In those who underwent SRT, rates of in-hospital mortality, pacemaker implantation, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation, ischemic stroke, major bleeding, and pericardial complication were assessed. All outcomes were compared between groups using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), adjusting for demographics, comorbidity burden, and hospital characteristics.

Results

In total, 72,680 weighted hospitalizations (median age: 67 years [range: 57-77]; 61% female patients) were included, and only 5.9% of patients underwent SRT. After IPTW adjustment, female patients were more likely to undergo SRT (adjusted risk ratio [aRR] 1.18, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.03-1.36) and alcohol septal ablation (aRR 1.38, 95% CI 1.04-1.83). Likewise, female patients received pacemaker implantation more often (aRR 1.96, 95% CI 1.10-3.50) and ICD implantation (aRR 0.58, 95% CI 0.34-0.99) less frequently, compared with male patients. No differences were present in rates of surgical septal myectomy, in-hospital mortality, ischemic stroke, major bleeding, and pericardial complication between groups.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that female patients were slightly more likely to undergo SRT, especially alcohol septal ablation. In-hospital mortality and postprocedural complications were similar between the sexes, but women received more pacemaker implantation and less ICD implantation.

Graphical abstract

Résumé

Contexte

Les données sont limitées sur les disparités potentielles liées au sexe dans l'utilisation et les complications de la thérapie de réduction septale (TRS) chez les patients atteints de cardiomyopathie hypertrophique obstructive. Notre objectif était d'évaluer l'utilisation et les résultats hospitaliers de la TRS, en fonction du sexe. Nous avons réalisé une étude de cohorte rétrospective en utilisant la base de données 2017-2019 National Inpatient Sample. Les patients adultes atteints de cardiomyopathie hypertrophique obstructive ont été identifiés.

Méthodes

Nous avons évalué le recours à la TRS (myectomie septale chirurgicale et ablation septale à l'alcool), en fonction du sexe. Les taux de mortalité à l'hôpital, d'implantation de stimulateurs cardiaques, de défibrillateurs cardioverteur implantables (DCI), d'accidents vasculaires cérébraux ischémiques, d'hémorragies majeures et de complications péricardiques ont été évalués chez les patients ayant subi une TRS. Tous les résultats ont été comparés entre les groupes en utilisant la pondération par l’inverse de la probabilité d’être traité (IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting), en ajustant pour les données démographiques, la charge de comorbidité et les caractéristiques de l'hôpital.

Résultats

Au total, 72,680 hospitalisations pondérées (âge médian: 67 ans [fourchette : 57-77]; 61% de patients de sexe féminin) ont été incluses, et seulement 5.9% des patients ont subi une TRS. Après ajustement de l'IPTW, les femmes étaient plus susceptibles de subir une TRS (rapport de risque ajusté [RRa] 1.18, intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95% 1.03-1.36) et une ablation septale à l'alcool (RRa 1.38, IC à 95% 1.04-1.83). De même, les patientes ont plus souvent bénéficié de l'implantation d'un stimulateur cardiaque (RRa 1.96, IC à 95% 1.10-3.50) et moins souvent de l'implantation d'un DCI (RRa 0.58, IC à 95% 0.34-0.99) que les patients de sexe masculin. Aucune différence n'a été constatée entre les groupes en ce qui concerne les taux de myectomie septale chirurgicale, de mortalité à l'hôpital, d'accident vasculaire cérébral ischémique, d'hémorragie majeure et de complication péricardique.

Conclusions

Nos résultats suggèrent que les patients de sexe féminin étaient légèrement plus susceptibles de subir une TRS, en particulier une ablation septale à l'alcool. La mortalité hospitalière et les complications post-procédurales étaient similaires entre les sexes, mais les femmes ont reçu plus d'implantations de stimulateurs cardiaques et moins d'implantations de DCI.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is one of the most common genetic heart diseases and is characterized by an unexplained hypertrophy of the left ventricle.1 Dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), either at rest or upon physical exertion, may be present in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 LVOTO is associated with an increased risk of heart failure, syncope, and sudden cardiac death.3 Septal reduction therapies (SRTs), including surgical myectomy and alcohol septal ablation, have been used widely to relieve LVOTO in patients with drug-refractory symptoms and resting or provoked gradients ≥ 50 mm Hg.3,4

In the field of cardiovascular disease, women often have been excluded or under-recruited to clinical trials and large research studies, making any generalization difficult regarding the effectiveness of treatments or interventions and the possible occurrence of adverse effects.5 In those with HCM, female patients, compared with male patients, tend to be older at diagnosis, present with more severe symptoms, have more-advanced disease, and receive fewer cardiovascular treatments.6

Historically, more patients diagnosed with HCM are male than female. A variable degree of genetic penetrance has been suggested, which would favour a more pronounced manifestation of the disease in male patients. Differences in HCM prevalence also could be explained by an underdiagnosis of HCM in female patients, as the autosomal dominant inheritance of HCM would be expected to result in similar proportions of female and male patients with this diagnosis.7 In addition, female patients with HCM have a higher mortality rate than do male patients,8 although both sexes have a similar risk of sudden death.9 Female patients also have worse cardiopulmonary exercise tolerance and different hemodynamics than male patients, more mitral regurgitation, and higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure.8

Although sex-based differences in the clinical presentation and prognosis of HCM have been reported previously, the impact of sex on surgical myectomy and alcohol septal ablation remains unclear.10, 11, 12 Therefore, we aimed to assess the prognostic role of sex on the use and short-term outcomes of SRTs in a large cohort of patients with obstructive HCM.

Methods

Data source and study population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). The NIS is the largest, publicly available, all-payer administrative database of hospital discharges developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that represents a 20% stratified sample of hospital discharges from all US community hospitals. All diagnoses and procedures are available in the NIS, noted using International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision codes. Our analyses focused on the NIS database from 2017 to 2019, to identify weighted admissions of adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) with obstructive HCM. We excluded patients with a diagnosis of aortic stenosis.

Outcomes

We assessed the use of SRT (surgical septal myectomy and alcohol septal ablation) during hospitalization, according to sex status. In addition, in those undergoing SRT, we assessed the following outcomes: in-hospital mortality; pacemaker implantation; implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation; ischemic stroke; major bleeding; and pericardial complication (Supplemental Table S1).

Covariates

Patient demographics and hospital characteristics were collected, including the following: age; race (White, Black, Hispanic, or other); type of admission (elective or nonelective); household income quartile ($1-$45,999; $46,000-$58,999; $59,000-$78,999; or ≥ $79,000); expected primary payer (Medicare, Medicaid, private, or other); hospital location (rural, urban nonteaching, or urban teaching); hospital bed size (small, medium, or large); hospital control and/or ownership (government nonfederal, private nonprofit, or private investor-owned); length of hospital stay; and total charges. In addition, the Deyo modification of the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was used to assess the comorbidity burden.13

Statistical analysis

Absolute and relative frequencies were used for categorical data, and mean ± standard deviation or median (percentile 25 – percentile 75) for continuous data. A χ2 test was used for categorical data, and an unpaired Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data, as appropriate. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to estimate the effect of sex on outcomes. The balance of baseline covariates (demographics, comorbidity burden, and hospital characteristics) was compared, using the standardized mean difference, considering an appropriate balance when the standardized mean difference was < 0.1. Adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated through a log-binomial model in the crude and weighted samples. All analyses were performed using R 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A 2-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics

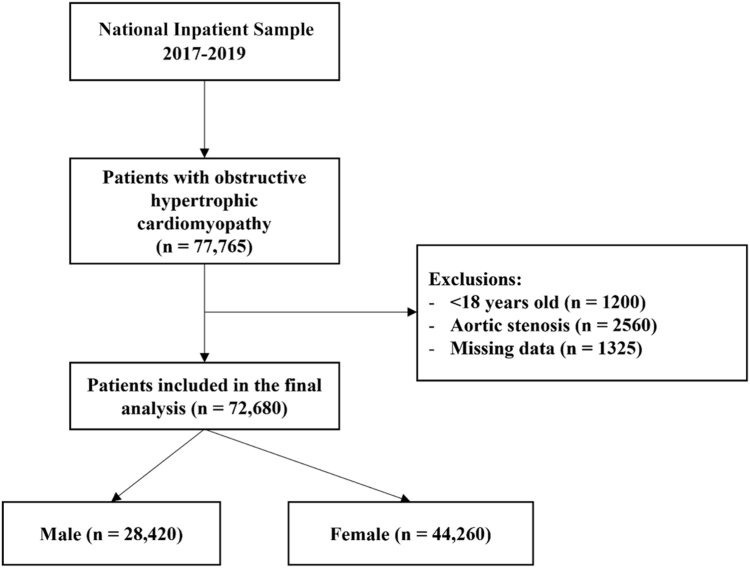

Of a total of 77,765 weighted hospitalizations in the NIS database with a diagnosis of obstructive HCM, 72,680 were included in the final analysis, of whom 60.9% were female patients (Fig. 1). Female patients were older than male patients (median age: 70 years [interquartile range {IQR} 60-80] vs 63 years [IQR 52-72] in male patients, P < 0.001; Table 1). In addition, the number of nonelective hospital admissions was slightly higher in female patients. With regard to hospital costs, male patients also were more likely to have private health insurance than were female patients (32% vs 18%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, hospital costs were higher for male patients than for female patients ($47,593 vs $44,162, P < 0.001). Among comorbidities, heart failure was more frequent in female patients with HCM (50% vs 41%, P < 0.001). Female patients, compared with male patients, also had a greater prevalence of hypertension (82% vs 78%, P < 0.001), valvular heart disease (33% vs 26%, P < 0.001), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (35% vs 24%, P < 0.001; Supplemental Table S2). Baseline covariates were well balanced after IPTW adjustment (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the selection of study participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

| Characteristic | Overall | Male patients | Female patients | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted hospitalizations, n | 72,680 | 28,420 | 44,260 | |

| Age, y | 67 (57–77) | 63 (52–72) | 70 (60–80) | < 0.001 |

| Race | < 0.001 | |||

| White | 50,275 (69) | 20,050 (71) | 30,225 (68) | |

| Black | 12,180 (17) | 4125 (15) | 8055 (18) | |

| Hispanic | 4220 (6) | 1735 (6) | 2485 (6) | |

| Other | 6005 (8) | 2510 (9) | 3495 (8) | |

| Household income, $ | < 0.001 | |||

| 1–45,999 | 19,635 (27) | 6915 (24) | 12,720 (29) | |

| 46,000–58,999 | 17,600 (24) | 6750 (24) | 10,850 (25) | |

| –59,000–78,999 | 17,765 (24) | 7180 (25) | 10,585 (24) | |

| ≥ 79,000 | 17,680 (24) | 7575 (27) | 10,105 (23) | |

| Elective admission | 14,395 (20) | 6215 (22) | 8180 (18) | < 0.001 |

| Admission on weekend | 14,335 (20) | 5565 (20) | 8770 (20) | 0.730 |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) | < 0.001 |

| Expected primary payer | < 0.001 | |||

| Medicare | 45,120 (62) | 14,405 (51) | 30,715 (69) | |

| Medicaid | 7570 (10) | 3155 (11) | 4415 (10) | |

| Private | 16,975 (23) | 9135 (32) | 7840 (18) | |

| Other | 3015 (4) | 1725 (6) | 1290 (3) | |

| Total charges, $ | 45,464 (23,411– 98,327) | 47,593 (23,768– 106,418) | 44,162 (23,101–92,741) | < 0.001 |

| Bed size of hospital | 0.002 | |||

| Small | 11,275 (16) | 4320 (15) | 6955 (16) | |

| Medium | 17,815 (25) | 6565 (23) | 11,250 (25) | |

| Large | 43,590 (60) | 17,535 (62) | 26,055 (59) | |

| Location of hospital | < 0.001 | |||

| Rural | 3685 (5) | 1335 (5) | 2350 (5) | |

| Urban, nonteaching | 9910 (14) | 3540 (12) | 6370 (14) | |

| Urban, teaching | 59,085 (81) | 23,545 (83) | 35,540 (80) | |

| Region of hospital | < 0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 16,425 (23) | 6695 (24) | 9730 (22) | |

| Midwest | 19,015 (26) | 7860 (28) | 11,155 (25) | |

| South | 23,730 (33) | 8575 (30) | 15,155 (34) | |

| West | 13,510 (19) | 5290 (19) | 8220 (19) | |

| Ownership of hospital | < 0.001 | |||

| Government, nonfederal | 7440 (10) | 3205 (11) | 4235 (10) | |

| Private, nonprofit | 60,030 (83) | 23,330 (82) | 36,700 (83) | |

| Private, investor-owned | 5210 (7) | 1885 (7) | 3325 (8) | |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index | 5.00 (3.00–6.00) | 5.00 (3.00–6.00) | 5.00 (4.00– 7.00) | < 0.001 |

Values are n (%), or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated.

Use of SRTs

In the crude analysis, only a minority of patients (5.9%) underwent a specific procedure for SRT (5.6% of female patients and 6.5% of male patients, P = 0.034; Table 2). The most common procedure for LVOTO was surgical septal myectomy, the prevalence of which was slightly higher for male patients (5%) than that for female patients (4%), P = 0.002. Alcohol septal ablation was performed in 1.6% of female patients and 1.4% of male patients (P = 0.272). In the adjusted analysis, outcomes according to sex showed a greater frequency of SRT in female, compared to male, patients (6.3% vs 5.3%, aRR 1.18, 95% CI 1.03-1.36, P = 0.016), and alcohol septal ablation (1.7% vs 1.2%, aRR 1.38, 95% CI 1.04-1.83, P = 0.024). Surgical septal myectomy was comparable in female vs male patients (4.6% vs 4.1%, aRR 1.12, 95% CI 0.96-1.32, P = 0.151; Table 3).

Table 2.

Crude and weighted outcomes according to sex status

| Characteristic | Crude outcomes |

Weighted outcomes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male patients | Female patients | P | Male patients | Female patients | P | |

| Septal reduction therapy | 6.5 | 5.6 | 0.034 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 0.016 |

| Surgical septal myectomy | 5.0 | 4.0 | 0.002 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 0.151 |

| Alcohol septal ablation | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.272 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.023 |

| In-hospital mortality | 1.1 | 2.8 | 0.079 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 0.353 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 4.6 | 11.5 | < 0.001 | 5.4 | 10.6 | 0.019 |

| ICD implantation | 9.5 | 4.8 | 0.007 | 9.1 | 5.3 | 0.045 |

| Ischemic stroke | 1.6 | 2.0 | 0.682 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.977 |

| Major bleeding | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.217 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.925 |

| Pericardial complication | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.044 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.055 |

Values are %, or P where indicated.

ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Table 3.

Crude and weighted analyses between sex and all outcomes

| Outcome | Crude model |

Weighted model∗ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cRR | 95% CI | P | aRR | 95% CI | P | |

| Septal reduction therapy | 0.87 | 0.76–0.99 | 0.034 | 1.18 | 1.03–1.36 | 0.016 |

| Surgical septal myectomy | 0.79 | 0.67–0.91 | 0.002 | 1.12 | 0.96–1.32 | 0.151 |

| Alcohol septal ablation | 1.16 | 0.89–1.53 | 0.272 | 1.38 | 1.04–1.83 | 0.024 |

| In-hospital mortality | 2.59 | 0.86–7.82 | 0.091 | 1.76 | 0.52–5.87 | 0.361 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 2.48 | 1.47–4.2 | < 0.001 | 1.96 | 1.1–3.5 | 0.023 |

| ICD implantation | 0.51 | 0.31–0.84 | 0.008 | 0.58 | 0.34–0.99 | 0.047 |

| Ischemic stroke | 1.23 | 0.45–3.37 | 0.682 | 1.02 | 0.36–2.9 | 0.977 |

| Major bleeding | 2.22 | 0.6–8.16 | 0.23 | 1.07 | 0.26–4.38 | 0.925 |

aRR, adjusted relative risk; CI, confidence interval; cRR, crude relative risk; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Male sex was the reference group for all analyses.

Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving SRTs

Patients undergoing septal reduction interventions were younger than those managed medically, and female patients were older than male patients (median age: 66 years [IQR 56-74] in female patients vs 57 years [IQR 49-67] years in male patients, P < 0.001; Supplemental Table S3). The Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was higher in female patients than in male patients (5 [IQR 3-6] vs 4 [IQR 3-6], P = 0.005). After IPTW adjustment, baseline covariates were well balanced (Supplemental Fig. S2). The prevalence of crude in-hospital mortality was higher among female patients than male patients (2.8% vs 1.1%, respectively, P = 0.079). However, adjusted in-hospital mortality did not differ between the sexes (2.7% for female patients and 1.5% for male patients; aRR 1.76, 95% CI 0.52-5.87, P = 0.361; Table 2; Table 3; Fig. 2). Female patients were more likely than male patients to require pacemaker implantation after SRT in both crude (11.5% vs 4.6%, P < 0.001) and adjusted analysis (10.6% vs 5.4%; aRR 1.96, 95% CI 1.10-3.50, P = 0.023), whereas male patients were more likely than female patients to receive defibrillator implantation, in both crude (4.8% vs 9.5%, P = 0.007) and adjusted analyses (9.1% vs 5.3%; aRR 0.58, 95% CI 0.34-0.99, P = 0.047; Table 2; Table 3; Fig. 2). No significant association was present between sex and ischemic stroke and major bleeding, using adjusted estimates (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the adjusted risk ratios (RRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between sex (reference group: male) and outcomes. The x-axis is in log scale. ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the largest to analyze the role of sex in SRT in patients with HCM, with a total of 72,680 weighted hospitalizations. We found the following: (i) a minority of patients (6%) underwent SRT; (ii) after IPTW adjustment, being female was associated with a higher risk of undergoing SRT, specifically alcohol septal ablation; and (iii) outcomes during hospitalization were similar for male and female patients, but women received more pacemaker implantation and less ICD implantation.

Other studies analyzing the general population of patients with HCM have found that it has a higher prevalence in male patients worldwide.6,14, 15, 16 In this study, we found that more than half of the patients admitted with a diagnosis of obstructive HCM were female. A previous report described that the HCM phenotype with LVOTO is more common in female patients than in male patients, which may explain the higher proportion of female patients in our study.12 Female patients with HCM have been been reported to have a higher left ventricular outflow tract gradient than male patients, and more than half of the female patients with HCM have a significant LVOTO, both at rest and during exercise.7,8,12,17

Female patients with HCM are diagnosed later than male patients, at a more advanced stage of the disease,7,12 with worse functional class. This finding is consistent with the more common history of heart failure in female patients that we have found. Although dyspnea is the most dominant symptom, female patients also have a higher prevalence of chest pain, fatigue, palpitations, or syncope than that of male patients.18 The prognosis in female patients with HCM is worse than that in male patients,19 and a higher mortality rate has been reported, especially for mortality due to worsening heart failure.20

An interesting aspect of our study, which also analyzed socioeconomic variables, is that it highlights a gender gap in the healthcare of patients with obstructive HCM. Male patients were more likely to have private insurance, and their income level was much higher than that of female patients. Compared to male patients, female patients face social and economic barriers to accessing healthcare.21,22 This situation would result in a longer delay in diagnosis for female patients with HCM and other medical conditions, who may present with more-advanced disease, once diagnosed, and are more likely to present to emergency services. The more-limited access to healthcare would lead to underdiagnosis and probably undertreatment of female patients. Therefore, the frequency of SRTs in female patients with HCM is likely to be lower than indicated here, given the worse outcomes and more-advanced disease that occur in female patients.

Later diagnosis in female patients presenting at an older age also affects medical decisions and the type of treatment they receive.23 SRT was more common in women, but the type of procedure differed between the sexes. After removing the effect of age in the statistical adjustment, a trend toward a higher propensity to use SRT in female patients was observed. This propensity is understandable given that female patients have more-severe HCM manifestations, including heart failure.23 However, the type of intervention differed between the 2 sexes. A less invasive approach was preferred in female patients, who received more alcohol septal ablation, whereas surgical septal myectomy was performed at an equal rate in both sexes.

As part of our study, we analyzed in-hospital mortality by sex in patients with obstructive HCM and found no differences between the sexes, or in the group of patients who underwent SRT. Despite the age difference and the more frequent history of heart failure in female patients, the in-hospital survival rate in patients who underwent SRTs was similar in both sexes.23,24 The rate of in-hospital mortality was low, around 2%, although female patients tended to have a slightly higher crude mortality rate. A previous study showed a higher mortality rate (4%) in patients undergoing septal reduction interventions, but this previous work included earlier procedures, so the improved technique and better postsurgery medical care may have influenced the more-favourable mortality rate found in our study.25

We did not find any differences in complications of septal reduction procedures between the sexes, despite the differences in age and comorbidities mentioned earlier. A trend toward a greater need for pacemaker implantation in female patients was observed, which also was observed in another study. Likely, the greater need for pacemakers in this group is explained by the greater indication for alcohol septal ablation in female patients.26 The frequency of ICD implantation in female patients was almost half that in male patients. Notably, sex was not shown to be a predictor associated with an increased risk of sudden death in patients with HCM. The reasons for this difference in indication for ICD implantation should be investigated further in future studies. In patients undergoing SRT for HCM, likely the lower incidence of initial indication for ICD implantation in female patients was due to factors such as age, although comorbidities, with the exception of heart failure, were fairly comparable between male and female patients, with a similar Charlson Comorbidity Index score. In other settings outside of invasive LVOTO treatment, in-hospital ICD implantation in patients with HCM was also lower in female patients.27,28 Other postoperative complications, such as bleeding and ischemic stroke, were similar in male vs female patients. As discussed earlier, the lack of differences likely is due to the selection of female patients who are at low surgical risk.

Another interesting part of our workis the inclusion of social and economic variables, including type of healthcare and expenditure. These factors play an increasingly important role in the care of patients with heart disease, including those with HCM. Female patients and those of minority races with HCM have been found to receive less-specialized care, including prevention of sudden cardiac death with ICD implantation, and in another study, even SRTs.26,27 An important point to recognize is that decisions to optimize medical therapy or refer for SRT are typically made during outpatient evaluations by cardiologists specializing in the management of HCM. The presence of referral bias is an important consideration in the interpretation of our results. Referral patterns may vary due to several factors, including clinician bias, patient preferences, and health inequalities. Plausibly, certain patient subgroups, including women, may be less likely to be referred for SRT, owing to unrecognized symptoms, underrepresentation in cardiology clinics, or other systemic factors. This difference in likelihood of referral may have contributed to the sex differences in SRT uptake observed in our study.

This study has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, our study relied on retrospective data extracted from the NIS database, which carries inherent limitations related to data accuracy, completeness, and potential bias in coding practices across institutions and over time. These factors could introduce misclassification, affecting the reliability of the observed associations. Second, as this was a clinical–administrative database, other variables relevant to patient prognosis, information that would drive SRT, such as symptomatology and LVOTO gradient, were not included. In addition, no information was available on medical treatments and genetic testing. Third, our study does not account for the selection process underlying the choice of SRT, which might introduce selection bias. Patients deemed to be suitable for this intervention could possess unique clinical characteristics and disease trajectories that could confound the relationship between sex and treatment outcomes. Patients with HCM exhibit marked variability in disease phenotype, severity, and associated complications, which may influence treatment decisions and outcomes. In addition, the sex differences observed, such as the older age of the female patient cohort and the higher prevalence of comorbidities, may affect the interpretation of these findings. Drawing meaningful conclusions about sex differences in outcomes and the use of SRT based on the data from our study alone is difficult, as retrospective analyses have inherent limitations. We therefore caution against overinterpretation of our findings, and emphasize the need for further research, ideally using prospective and more-detailed data, to provide a better understanding of the complexities of sex differences in HCM management. Finally, because the database contains information from only the period during hospitalization, evaluation of medium- and long-term outcomes was not possible.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that although the level of use of SRT was higher in female patients with HCM, an underindication for these procedures may be occurring. In selected patients who underwent SRT, the risks of in-hospital mortality and postprocedural complications were similar in men vs women, but women received more pacemaker implantation and less ICD implantation.

Data Statement

Data are available in a public, open-access repository. The National Inpatient Sample is available online at https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/databases.jsp.

Patient Consent

The authors confirm that patient consent is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

L.V. is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain (CM20/00104 and JR22/00004). The other authors have no funding sources to declare.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See page 1114 for disclosure information.

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit CJC Open at https://www.cjcopen.ca/ and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2024.05.013.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Maron B.J., Desai M.Y., Nishimura R.A., et al. Diagnosis and evaluation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:372–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron B.J., Desai M.Y., Nishimura R.A., et al. Management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:390–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ommen S.R., Mital S., Burke M.A., et al. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:3022–3055. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sebastian S.A., Panthangi V., Singh K., et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: current treatment and future options. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48 doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin X., Chandramouli C., Allocco B., et al. Women's participation in cardiovascular clinical trials from 2010 to 2017. Circulation. 2020;141:540–548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olivotto I., Maron M.S., Adabag A.S., et al. Gender-related differences in the clinical presentation and outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siontis K.C., Ommen S.R., Geske J.B. Sex, survival, and cardiomyopathy: differences between men and women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geske J.B., Ong K.C., Siontis K.C., et al. Women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have worse survival. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:3434–3440. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowin E.J., Maron M.S., Wells S., et al. Impact of sex on clinical course and survival in the contemporary treatment era for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao H., Tan Z., Liu M., et al. Is there a sex difference in the prognosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.026270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butzner M., Leslie D., Cuffee Y., et al. Sex differences in clinical outcomes for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the USA: a retrospective observational study of administrative claims data. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butters A., Lakdawala N.K., Ingles J. Sex differences in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: interaction with genetics and environment. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2021;18:264–273. doi: 10.1007/s11897-021-00526-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quan H., Sundararajan V., Halfon P., et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maron B.J., Olivotto I., Bellone P., et al. Clinical profile of stroke in 900 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:301–307. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01727-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butzner M., Leslie D.L., Cuffee Y., et al. Stable rates of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a contemporary era. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.765876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee C.H., Liu P.Y., Lin L.J., Chen J.H., Tsai L.M. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Taiwan—a tertiary center experience. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30:177–182. doi: 10.1002/clc.20057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maron M.S., Olivotto I., Betocchi S., et al. Effect of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on clinical outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:295–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preveden A., Golubovic M., Bjelobrk M., et al. Gender-related differences in the clinical presentation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy—an analysis from the SILICOFCM Database. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58:314. doi: 10.3390/medicina58020314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trongtorsak A., Polpichai N., Thangjui S., et al. Gender-related differences in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulse (Basel) 2021;9:38–46. doi: 10.1159/000517618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimitrow P.P., Czarnecka D., Jaszcz K.K., Dubiel J.S. Sex differences in age at onset of symptoms in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1997;4:33–35. doi: 10.1177/174182679700400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee L.K., Chien A., Stewart A., et al. Women's coverage, utilization, affordability, and health after the ACA: a review of the literature. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:387–394. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vohra-Gupta S., Petruzzi L., Jones C., Cubbin C. An intersectional approach to understanding barriers to healthcare for women. J Community Health. 2023;48:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s10900-022-01147-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meghji Z., Nguyen A., Fatima B., et al. Survival differences in women and men after septal myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:237–245. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sreenivasan J., Khan M.S., Kaul R., et al. Sex differences in the outcomes of septal reduction therapies for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:930–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altibi A.M., Ghanem F., Zhao Y., et al. Hospital procedural volume and clinical outcomes following septal reduction therapy in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.028693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawin D., Lawrenz T., Marx K., et al. Gender disparities in alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2022;108:1623–1628. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2022-320852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patlolla S.H., Schaff H.V., Nishimura R.A., et al. Sex and race disparities in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: unequal implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use during hospitalization. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhalla J.S., Madhavan M. Racial and sex disparities in the management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:442–444. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.