Abstract

Aim

Abundant data are available on the effect of the A118G (rs1799971) single‐nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the μ‐opioid receptor OPRM1 gene on morphine and fentanyl requirements for pain control. However, data on the effect of this SNP on intraoperative remifentanil requirements remain limited. We investigated the effect of this SNP on intraoperative remifentanil requirements.

Methods

We investigated 333 Japanese women, aged 21–69 years, who underwent laparoscopic gynecological surgery for benign gynecological disease under total intravenous anesthesia at Juntendo University Hospital. Average infusion rates of propofol and remifentanil during anesthesia and the average bispectral index (BIS) during surgery were recorded. Associations among genotypes of the A118G and phenotypes were examined with the Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

The average propofol infusion rate was not different between patients with different genotypes. The average remifentanil infusion rate was significantly higher in patients with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype (p = 0.028). The average intraoperative BIS was significantly higher in patients with the GG genotype than the AA or AG genotype (p = 0.039).

Conclusions

The G allele of the A118G SNP was associated with higher intraoperative remifentanil requirements and higher intraoperative BIS values but was not associated with propofol requirements. Given that remifentanil and propofol act synergistically on the BIS, these results suggest that the G allele of the A118G SNP is associated with lower effects of remifentanil in achieving adequate intraoperative analgesia and in potentiating the sedative effect of propofol on the BIS.

Keywords: bispectral index, laparoscopic gynecologic surgery, mu‐opioid receptor gene, remifentanil, single‐nucleotide polymorphism

The G allele of the A118G polymorphism of the OPRM1 gene was associated with higher intraoperative remifentanil requirements and higher intraoperative bispectral index values in patients who underwent laparoscopic gynecological surgery under total intravenous anesthesia.

1. INTRODUCTION

There is considerable individual variation in the dose of opioids that is required to achieve adequate analgesia, reflecting significant individual differences in the sensitivity to opioids. 1 , 2 Although various candidate gene polymorphisms have been reported to affect the sensitivity to opioids, the A118G (rs1799971) single‐nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the OPRM1 gene, which encodes the μ‐opioid receptor, has been the most widely investigated genetic variation. 1 , 2 Many studies show that carriers of the G allele of the A118G SNP require higher opioid doses for pain control than non‐carriers. 1 , 2 However, remaining unclear is whether the G allele of this SNP uniformly increases opioid requirements. A meta‐analysis of the association between this SNP and postoperative opioid requirements concluded that G‐allele carriers required higher opioid doses than non‐carriers, especially in Asian populations, patients who received morphine, and patients who underwent visceral surgery. 3 However, this meta‐analysis demonstrated a significant effect of this SNP on postoperative morphine requirements but not fentanyl requirements, suggesting that the effect of the A118G SNP on opioid requirements may be ligand‐dependent. 3

Abundant data are available on the effect of the A118G SNP on postoperative morphine and fentanyl requirements. 1 , 2 , 3 However, to our knowledge, only three studies have investigated the effect of this SNP on requirements for the ultrashort‐acting opioid remifentanil that is used during surgery under general anesthesia, and conflicting results have been reported. 4 , 5 , 6 These disparate findings include intraoperative remifentanil requirements that were significantly higher in patients with the AG genotype than the AA genotype, 4 intraoperative remifentanil requirements that were unaffected by genotypes of the A118G SNP, 5 and intraoperative remifentanil requirements that tended to be lower in patients with the GG genotype than the AA or AG genotype. 6 Therefore, further data on this issue are crucial to clarify the precise effect of this SNP on remifentanil requirements. Thus, the present study investigated the effect of the A118G SNP on remifentanil requirements during surgical anesthesia.

2. METHODS

Before the study, the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Juntendo University Faculty of Medicine (protocol code: 2015053, date of approval: September 18, 2015) and Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science (protocol code: 15–29, date of approval: September 30, 2015). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Enrolled in the study were Japanese women, aged 21–69 years, who were classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status (ASA‐PS) Class I or II and scheduled to undergo laparoscopic gynecological surgery (LGS) for benign gynecological disease, such as uterine myoma and ovarian cysts, at Juntendo University Hospital between June 2017 and May 2019. Excluded were patients who chronically received antipsychotic drugs, antiepileptic drugs, or opioid analgesics, patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and patients with a body mass index (BMI) higher than 30 kg/m2. Additionally, patients for whom surgery was converted from LGS to open abdominal surgery were excluded.

2.1. General anesthesia

In the operating room, patients were monitored with a three‐lead electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure, percutaneous arterial oxygen saturation, and the electroencephalographic (EEG) bispectral index (BIS; Covidien, Dublin, Ireland). Anesthesia was induced with remifentanil at a rate of 0.5 μg/kg/min and a target‐controlled infusion (TCI) of propofol at a target concentration of 3–5 μg/mL using a TCI pump (TE‐371, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). After the cumulative remifentanil dose reached 3 μg/kg, the infusion rate was reduced to 0.2 μg/kg/min. After the BIS decreased to 60 or less, rocuronium bromide (1 mg/kg) was administered i.v. to facilitate tracheal intubation. The lungs were ventilated with oxygen‐enriched air using mechanical ventilation by employing a positive end‐expiratory pressure of 4 cmH2O. Minute ventilation was adjusted to keep end‐tidal carbon dioxide tension around 40 mmHg. The target concentration of propofol was adjusted to maintain the BIS between 40 and 60. Crystalloid was infused at a rate of 5 mL/kg/h. Dexamethasone (6.6 mg) and droperidol (1.25 mg) were administered i.v. to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), based on our previous study. 7 Ten milliliters of venous blood was sampled for the preparation of DNA specimens.

Before starting surgery, the infusion rate of remifentanil was increased to 0.3 μg/kg/min. During surgery, when hemodynamics could change in response to changing intensities of surgical stimuli, the infusion rate of remifentanil was titrated (within a range of 0.1–0.5 μg/kg/min) to keep systolic blood pressure (SBP) around 100 mmHg and heart rate (HR) at 75/min or less. Hypotension (SBP < 80 mmHg) was treated with i.v. ephedrine (5 mg) or phenylephrine (0.1 mg). Bradycardia (HR < 40/min) was treated with i.v. atropine (0.5 mg). Rocuronium bromide (10–20 mg) was repeatedly administered as required. At the end of surgery, infusions of propofol and remifentanil were discontinued. Fentanyl (4 μg/kg) and acetaminophen (20 mg/kg, up to 1000 mg) were administered i.v. to achieve immediate postoperative pain relief. Neuromuscular blockade was reversed with sugammadex (2–4 mg/kg). Patients were extubated after the recovery of adequate consciousness and spontaneous breathing. When patients complained of significant pain, rated 4 or higher on a 11‐point numerical rating scale (NRS: 0 = no pain; 10 = worst pain imaginable), a 50 μg or higher dose of fentanyl was administered in increments until adequate pain relief (pain rating ≤ 3) was achieved.

2.2. Postoperative pain management

Postoperative pain was then managed with i.v. fentanyl via patient‐controlled analgesia (PCA) using a CADD‐Legacy PCA pump (Smiths Medical Japan, Tokyo, Japan), whose cassette was filled with fentanyl (1000 μg in 20 mL) and droperidol (2.5 mg in 1 mL) diluted with normal saline (80 mL) to a total volume of 101 mL. A bolus dose of fentanyl on demand and lockout time were set at 25 μg and 5 min, respectively. Continuous background infusion was not employed. Additionally, acetaminophen (20 mg/kg, up to 1000 mg) was administered i.v. every 6 h until it became unnecessary during the first 24‐h postoperative period. When analgesia that was achieved with fentanyl PCA and periodic acetaminophen was inadequate, i.v. flurbiprofen axetil (50 mg) or i.v. pentazocine (30 mg) was administered as a rescue analgesic. The NRS pain score was assessed every 3 h (unless patients were asleep) until 12 h postoperatively and then every 6 h until 24 h postoperatively. The presence/absence of PONV was assessed at the same time or whenever patients complained of PONV. When required, i.v. metoclopramide (10 mg) or rectal domperidone (60 mg) was used to treat PONV. Other side effects of fentanyl, including respiratory depression, were also noted.

2.3. Genotyping the A118G SNP

DNA was extracted from whole‐blood samples by standard procedures. The extracted DNA was dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl and 1 mM ethylene‐diaminetetraacetic acid, pH 8.0). Briefly, whole‐genome genotyping was performed by utilizing the Infinium Assay II with an iScan system according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Infinium Asian Screening Array‐24 v. 1.0 BeadChips were utilized to genotype 333 patients' samples that remained after the filtration process based on the exclusion criteria of clinical data (total markers: 659184). GenomeStudio with the Genotyping v. 2.0.4 module (Illumina) was used to examine data for samples that had their entire genomes genotyped to assess quality of the findings, and quality control was performed as described in our previous report. 8 Because the genotype data for the A118G (rs1799971) SNP were included in the aforementioned BeadChip for whole‐genome genotyping, the data were extracted from the results of whole‐genome genotyping and used for the association study.

2.4. Data collection

As preoperative data, age, body height, body weight, and the BMI were recorded. As intraoperative data, the duration of surgery, duration of anesthesia, and duration of drug infusion (common to propofol and remifentanil) were recorded. Average infusion rates of propofol and remifentanil were calculated as total drug doses that were given during anesthesia divided by body weight and the duration of drug infusion. The average intraoperative BIS was calculated by averaging BIS values that were recorded every minute on the electronic anesthesia record (ORSYS, Philips Japan, Tokyo, Japan) during surgery. The use of vasoconstrictors (ephedrine or phenylephrine) and atropine was recorded.

As postoperative data, the initial bolus dose of fentanyl that was administered around the end of anesthesia and the dose of fentanyl consumed via PCA within the 24 h postoperative period were recorded. The total postoperative fentanyl dose was calculated as the sum of the initial fentanyl dose and PCA fentanyl consumption dose. These fentanyl doses were normalized to body weight. The number of i.v. acetaminophen doses that were given to each patient and the number of patients who required rescue analgesics within the 24 h postoperative period were also recorded. The average NRS pain score for each patient was calculated by averaging all NRS pain scores that were recorded within 24 h. The number of patients who experienced PONV or other adverse effects within 24 h was also recorded.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Because all continuous variables were non‐normally distributed after Shapiro–Wilk testing, continuous variables are shown as the median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are presented as a number (%). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables among patients with AA, AG, and GG genotypes of the A118G SNP. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between patients with two different genotypes or patients with dichotomized genotypes. Categorical data were compared with the χ 2 test among or between these patients. Additionally, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was tested using the χ 2 test (df = 1) for genotypic distributions of the SNP. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v. 27.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. RESULTS

A total of 333 patients who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria were studied. Perioperative data for these patients are shown in Table 1. Genotypes of the A118G SNP were AA in 121 women (36.3%), AG in 152 women (45.7%), and GG in 60 women (18.0%; Table 1). The minor G allele frequency was 40.8%. The genotype distribution met the criteria of testing for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p = 0.312).

TABLE 1.

Perioperative data in the total cohort and in patients with AA, AG, and GG genotypes of the A118G single‐nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the OPRM1 gene.

| Perioperative clinical variables | Total cohort (n = 333) | Genotypes of the A118G SNP | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA (n = 121) | AG (n = 152) | GG (n = 60) | |||

| Age (years) | 40 (32.8, 46) | 39 (31, 45) | 41 (33, 47) | 40.5 (35.5, 44) | 0.318 |

| Body height (cm) | 160 (156.48, 163.5) | 160 (156.38, 163.03) | 160 (156.1, 163.4) | 160 (157.3, 164.3) | 0.538 |

| Body weight (kg) | 53.55 (48.59, 59.71) | 51.9 (48.14, 57.71) | 54.65 (49.45, 60.13)* | 53.85 (47.95, 61.25) | 0.094 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 20.9 (19.1, 22.9) | 20.3 (18.88, 22.35) | 21 (19.6, 23.7) | 20.55 (19, 23.4) | 0.235 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 124 (98, 158) | 121 (85, 152.3) | 134.5 (99, 165) | 125.5 (105.5, 154) | 0.137 |

| Duration of anesthesia (min) | 171 (142.8, 206) | 168 (129, 195.5) | 178.5 (141.5, 214.5)* | 168 (149, 204) | 0.116 |

| Duration of drug infusion (min) | 145 (116.8, 178.3) | 136 (104.8, 167.3) | 152.5 (118, 188)* | 146 (124, 179.5) | 0.099 |

| Intraoperative bleeding (mL) | 20 (10, 50) | 20 (10, 50) | 25 (10, 65) | 30 (10, 60) | 0.225 |

| Average propofol infusion rate (mg/kg/h) | 6.41 (5.598, 7.245) | 6.63 (5.523, 7.288) | 6.26 (5.585, 7.19) | 6.36 (5.68, 6.98) | 0.705 |

| Average remifentanil infusion rate (μg/kg/min) | 0.300 (0.267, 0.336) | 0.296 (0.257, 0.326) | 0.300 (0.271, 0.338) | 0.312 (0.279, 0.369)* | 0.046 |

| Average intraoperative bispectral index | 42.4 (39.2, 46.8) | 42.1 (39.2, 46.2) | 42.2 (39.25, 46.25) | 44.7 (39.05, 49.3) | 0.119 |

| Use of ephedrine or phenylephrine (n [%]) | 153 (45.9%) | 59 (48.8%) | 67 (44.1%) | 27 (45.0%) | 0.733 |

| Use of atropine (n [%]) | 16 (4.8%) | 5 (4.1%) | 8 (5.3%) | 3 (5.0%) | 0.907 |

| Initial fentanyl dose (μg/kg) | 3.96 (3.94, 4.00) | 3.96 (3.94, 4.00) | 3.97 (3.94, 4.00) | 3.96 (3.93, 3.98) | 0.384 |

| PCA fentanyl consumption dose (μg/kg) | 4.54 (2.185, 7.455) | 4.53 (2.115, 7.34) | 4.205 (1.88, 7.38) | 5.195 (2.945, 8.095) | 0.331 |

| Total postoperative fentanyl dose (μg/kg) | 8.79 (6.333, 11.963) | 8.70 (6.223, 11.358) | 8.375 (6.215, 11.775) | 9.16 (6.91, 12.435) | 0.412 |

| Number of acetaminophen doses | 3 (3, 3) | 3 (2, 3) | 3 (3, 3)* | 3 (3, 3) | 0.237 |

| Average Numerical Rating Scale pain score | 1.7 (1, 2.5) | 1.7 (1, 2.63) | 1.7 (1, 2.6) | 1.5 (1, 2.3) | 0.732 |

| Use of rescue analgesics (n [%]) | 27 (8.1%) | 8 (6.6%) | 15 (9.9%) | 4 (6.7%) | 0.559 |

| Postoperative nausea and vomiting (n [%]) | 44 (13.2%) | 13 (10.7%) | 25 (16.4%) | 6 (10.0%) | 0.277 |

Note: Data are expressed as the median (interquartile range) or number (%). Values of p, based on the Kruskal–Wallis test or χ 2 test, are depicted.

p < 0.05, versus AA (Mann–Whitney U test).

3.1. Associations among genotypes of the A118G SNP and pre‐ and intraoperative data

The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed that among all perioperative data that were examined, only the average remifentanil infusion rate was significantly different among patients with AA, AG, and GG genotypes (p = 0.046; Table 1).

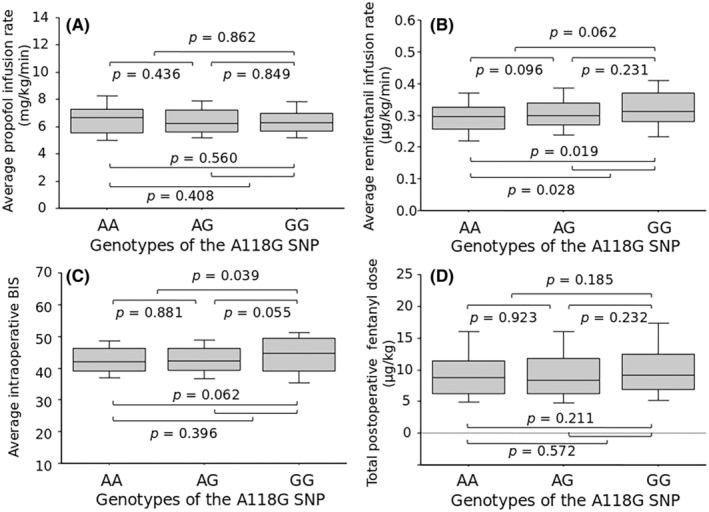

The Mann–Whitney U test revealed that the average propofol infusion rate was not different among patients with the three different genotypes or between patients with two different genotypes or dichotomized genotypes (Table 1, Figure 1A). The average remifentanil infusion rate tended to be higher in patients with the AG genotype than the AA genotype (p = 0.096) and was significantly higher in patients with the GG genotype than the AA genotype (p = 0.019; Figure 1B). Consequently, it was significantly higher in patients with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype (p = 0.028; Figure 1B). Although body weight was lower, the duration of surgery tended to be shorter, the duration of anesthesia was shorter, and consequently the duration of drug infusion was shorter in patients with the AA genotype than the AG genotype (p = 0.031, p = 0.055, p = 0.044, and p = 0.038, respectively; Table 1). Such differences would not influence the significant differences in the average infusion rate of remifentanil because this value was already adjusted for weight and the duration of drug infusion. The average intraoperative BIS tended to be higher in patients with the GG genotype than the AG genotype (p = 0.055) and in patients with the GG genotype than the AA genotype (p = 0.062; Figure 1C). Consequently, it was significantly higher in patients with the GG genotype than the AA or AG genotype (p = 0.039; Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Association between genotypes of the A118G single‐nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and (A) average propofol infusion rate, (B) average remifentanil infusion rate, (C) the average intraoperative bispectral index (BIS), and (D) total postoperative fentanyl dose. The data are expressed as box and whisker plots. The solid line in the box depicts the median. Ends of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles. Values of p, based on the Mann–Whitney U test, are depicted.

During anesthesia, 153 patients (45.9%) received ephedrine or phenylephrine to treat hypotension, and 16 patients (4.8%) received atropine to treat bradycardia, mostly once during anesthesia. Numbers of patients who received these vasoactive agents were not different among or between patients with any different genotype (Table 1).

3.2. Associations among genotypes of the A118G SNP and postoperative data

The number of periodic postoperative acetaminophen doses that were required during 24 h was significantly higher in patients with the AG genotype than the AA genotype (p = 0.039) and in patients with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype (p = 0.040; Table 1). Other pain‐related phenotypes, including the initial fentanyl bolus dose, PCA fentanyl consumption dose, total postoperative fentanyl dose (Figure 1D), number of patients who required rescue analgesics, and average NRS pain score, were not different among or between patients with any different genotype (Table 1). No significant postoperative complications, such as respiratory depression, developed in the patients. However, PONV developed in 44 patients (13.2%). The incidence of PONV was not different among or between patients with any different genotype (Table 1).

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, the average propofol infusion rate was not different according to genotypes, whereas the average remifentanil infusion rate was higher in patients with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype. The average intraoperative BIS was higher in patients with the GG genotype than the AA or AG genotype. Postoperative fentanyl requirements or postoperative pain scores were not different according to genotype, although the number of periodic postoperative acetaminophen doses was significantly higher in patients with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype.

In the present study, the A118G SNP did not affect postoperative fentanyl requirements. This finding agreed with results of a meta‐analysis that showed that the A118G SNP did not affect postoperative fentanyl requirements in a total of 1146 patients from seven studies, whereas this SNP had a significant effect on postoperative morphine requirements in a total of 3127 patients from nine studies, such that postoperative morphine requirements were higher in patients with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype. 3 However, more recent studies that investigated 240 patients who underwent cesarean section and 257 patients who underwent breast surgery reported that postoperative fentanyl requirements were higher in patients with the GG genotype than the AA or AG genotype. 9 , 10 In the present study, acetaminophen in periodic doses was co‐used with fentanyl PCA to achieve its opioid‐sparing effect, 11 , 12 and patients with the AG or GG genotype required more acetaminophen doses than patients with the AA genotype. Thus, the possibility cannot be excluded that co‐used acetaminophen might have masked the effect of the A118G SNP on postoperative fentanyl requirements.

The average remifentanil infusion rate that was required to achieve stable intraoperative hemodynamics was significantly higher in patients with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype, consistent with the generalized notion that the G allele of the A118G SNP reduces analgesic effects of opioids, thereby increasing doses of opioids that are required to achieve adequate analgesia. 1 , 2 , 3 Furthermore, our data agreed with previous findings that in 121 patients who underwent septoplasty under general anesthesia with fixed‐dose sevoflurane and variable‐dose remifentanil, a higher dose of remifentanil was required in patients with the AG genotype than the AA genotype. 4

Additionally, the average intraoperative BIS was higher in patients with the GG genotype than the AA or AG genotype, although patients received similar propofol doses regardless of genotype, and G‐allele carriers received higher remifentanil doses than non‐carriers. Given that propofol and remifentanil act synergistically to deepen sedation/anesthesia and thus reduce the BIS, 13 , 14 our data suggested that remifentanil potentiated the sedative effect of propofol on the BIS less effectively in patients with the GG genotype than the AA or AG genotype, in agreement with previous findings that in 207 patients who underwent endoscopic procedures under sedation‐analgesia with propofol and remifentanil, remifentanil synergistically potentiated the sedative effect of propofol on the BIS in patients with the AA or AG genotype but not in patients with the GG genotype. 14 Our data thus suggested that the G allele of the A118G SNP was associated not only with a lower analgesic effect of remifentanil but also with its lower ability to potentiate the sedative or BIS‐reducing effect of propofol.

Abundant data are available on the association between the A118G SNP and sensitivity to morphine and fentanyl. 1 , 2 , 3 To the best of our knowledge, however, only three studies have investigated the effect of this SNP on requirements for intraoperative remifentanil that is used during general anesthesia for surgical procedures. 4 , 5 , 6 Only eight studies have investigated the effect of this SNP on the efficacy of remifentanil that is used in other situations, such as sedation‐analgesia for endoscopic procedures, 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 and inconsistent results have been reported.

As mentioned above, a higher dose of remifentanil was required during surgical anesthesia in patients with the AG genotype than the AA genotype. 4 Remifentanil synergistically potentiated the sedative effect of propofol on the BIS in patients with the AA or AG genotype but not in patients with the GG genotype during sedation‐analgesia for endoscopic procedures. 14 Similarly, in 200 patients who underwent endoscopic procedures under sedation‐analgesia with propofol and remifentanil, the ability of EEG measures to predict responses to painful stimuli was enhanced in patients with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype, suggesting that sedation‐analgesia was lighter in G‐allele carriers. 15 Furthermore, in 54 women who underwent elective cesarean section under general anesthesia that was induced with fixed‐dose remifentanil and thiopental and maintained with fixed‐dose sevoflurane and nitrous oxide, an increase in blood pressure before delivery was better attenuated in women with the AA genotype than the AG genotype, although not statistically significantly. 16 Our unpublished reanalysis of previously reported data from 350 patients who underwent laparoscopic‐assisted colectomy under general anesthesia with fixed‐dose sevoflurane and variable‐dose remifentanil 22 revealed that a median remifentanil infusion rate increased in the order of patients with the AA (0.210 μg/kg/min), AG (0.217 μg/kg/min), and GG (0.222 μg/kg/min) genotypes, although not statistically significantly, whereas the median BIS increased in the order of patients with the AA (44.2), AG (45.8), and GG (48.0) genotypes, and the BIS was significantly higher in patients with the GG genotype than the AA genotype (p = 0.023). These data support our present findings that suggested that the G allele of the A118G was associated with a lower analgesic effect of remifentanil and its lower ability to potentiate propofol‐induced sedation.

In 416 patients who underwent breast surgery under general anesthesia with the anesthetic propofol or sevoflurane and the analgesic remifentanil, the intraoperative dose of remifentanil was not affected by genotype of the A118G SNP, although PONV was milder in patients with the GG genotype than the AA or AG genotype. 5 In 178 patients who underwent gynecological hysteroscopic procedures under monitored anesthesia care with remifentanil, intraoperative remifentanil consumption was affected by the rs2075572 SNP of the OPRM1 gene but not by the rs1799971 (A118G) SNP. 17 The sensitivity to remifentanil, assessed by changes in pressure pain thresholds that were measured before and after remifentanil infusion in 137 patients before anesthesia for gynecological surgery, was affected by the rs9397685 SNP of the OPRM1 gene but not by the rs1799971 (A118G) SNP. 18 In 136 patients who underwent endoscopic procedures under sedation‐analgesia with propofol and remifentanil, A118G genotypes did not affect remifentanil‐induced respiratory depression. 19 These data suggest that the A118G SNP does not affect the sensitivity to remifentanil, unlike our data.

Furthermore, in 90 patients who underwent thyroidectomy under general anesthesia with propofol and remifentanil, patients with the GG genotype consumed less remifentanil than patients with the AA or AG genotype, although not statistically significantly. 6 In 72 children who were anesthetized with propofol and remifentanil, mean blood pressure decreased more in children with the AG or GG genotype than the AA genotype, possibly reflecting deeper anesthesia that was achieved in G‐allele carriers. 20 In 80 patients with chronic low back pain before anesthesia for spinal fusion surgery, the G‐allele of the A118G SNP was associated with greater sensitivity to remifentanil, assessed by its pain‐relieving effect on pressure‐induced pain that was applied to the painful lesion in the lower back. 21 These data appear to be contrary to the present findings and also to the generalized notion that the G allele of the A118G SNP is associated with lower sensitivity to opioids. 1 , 2 , 3

As such, the results might differ when considering various factors, including the number of subjects studied, methods that are used to evaluate remifentanil sensitivity, types of surgery and procedures, types of general anesthesia and sedation, types of opioids, types of acute and chronic pain, and specific subject characteristics, such as age, sex, and ethnicity. 1 , 2 , 3 Clearly, further data are required to elucidate the precise effect of the A118G SNP on the analgesic effect of remifentanil and its ability to potentiate propofol‐induced sedation.

The frequency of the minor G allele was 40.8% in the present study in patients who underwent laparoscopic gynecological surgery, which was mostly consistent with other genotypic studies of the A118G SNP in Asian populations. 3 , 5 The consistency of this rate could indicate the accuracy of our genotypic data and possibly suggest similar rates among Asian populations whose perioperative opioid requirements are affected by this SNP.

In the present study, body weight was lower in patients with the AA genotype than the AG genotype. The duration of surgery also tended to be shorter, the duration of anesthesia was shorter, and consequently, the duration of drug infusion was shorter in patients with the AA genotype than the AG genotype. Because genotypes of the A118G SNP are highly unlikely to affect body weight or durations of surgery, anesthesia, or drug infusion for any surgical procedure, such differences could have resulted not from genotypes of the A118G SNP but rather from the insufficiently large number of patients to adequately control for clinical backgrounds of patients with different genotypes. However, such differences would not affect the significant association between genotypes of the A118G SNP and the average remifentanil infusion rate because this rate was already adjusted for body weight and the duration of drug infusion.

In our patients, higher rates of remifentanil infusion were required in G‐allele carriers to achieve stable intraoperative hemodynamics and in G‐allele homozygotes to achieve adequate sedative effects, possibly reflecting the G allele of the A118G SNP that was associated with lower analgesic/sedative effects of remifentanil. However, higher doses of remifentanil in G‐allele carriers would not result in immediate postoperative adverse effects, such as respiratory depression, because of remifentanil's ultrashort action that does not outlast the duration of anesthesia. 23 However, high‐dose remifentanil is associated with the development of acute opioid tolerance and/or opioid‐induced hyperalgesia, which can increase postoperative opioid requirements. 23 However, the G allele of the A118G SNP was not associated with higher postoperative fentanyl requirements in the present study. These results suggest that the mild increase in intraoperative remifentanil requirements that was associated with the G allele would not exert significant effects on patients' clinical outcomes.

The present study has limitations. First, the sample size might not be sufficiently large to draw definite conclusions, even after adjustments for multiple testing, although the sample size was mostly greater than in previous studies. 4 , 5 , 6 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 Second, some clinical background information, such as body weight and the duration of drug infusion, was not completely controlled among patients with different genotypes, although these differences would not affect the present findings of significant associations between genotypes of the A118G SNP and the average infusion rate of remifentanil, as mentioned above.

5. CONCLUSION

The G allele of the A118G SNP was associated with a greater need for intraoperative remifentanil and a higher intraoperative BIS, but it was not associated with the need for propofol. Given that remifentanil and propofol act synergistically to reduce the BIS, these results indicated that the G allele of the A118G SNP was associated with lower effects of remifentanil in achieving adequate intraoperative analgesia and in potentiating the sedative effect of propofol in Japanese women who underwent laparoscopic gynecological surgery.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MH, DN, and KI conceived and designed the study. MK conducted surgery. RI conducted anesthesia. RI, AH, and HS acquired the clinical data. RZ, DN, JH, YE, and KN analyzed the genetic data. RZ, DN, and MH conducted the statistical analysis. RZ drafted the original manuscript. DN and MH edited the manuscript. MH, KI, and IK supervised the conduct of this study. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DISCLOSURE

This research was funded by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (no. 22790518, 23 390 377, 24 790 544, 26 293 347, JP22H04922 [AdAMS], 17H04324, 17K08970, 18K08829, 20K09259, 21H03028, and 23K21457), Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) of Japan (no. H26‐Kakushintekigan‐ippan‐060), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED; no. JP19ek0610011 and JP19dk0307071), Smoking Research Foundation (Tokyo, Japan), Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology (JRFCP), and Asahi Kasei Pharma Open Innovation. The article processing charge was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI. Kazutaka Ikeda has received support from Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation and SBI Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd. and speaker's and consultant's fees from MSD K.K., VistaGen Therapeutics, Inc., Atheneum Partners Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Taisho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Eisai, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Inc., Sumitomo Pharma, Japan Tobacco, Inc., EA Pharma Co. Ltd., and Nippon Chemiphar. Kazutaka Ikeda is an Editorial Board member of Neuropsychopharmacology Reports and a coauthor of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision‐making related to the acceptance of this article for publication.

ETHICS STATEMENTS

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: The protocol for this research project has been approved by a suitably constituted Ethics Committees of the institutions and it conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Committee of Juntendo University Faculty of Medicine, Approval No. 2015053 (date of approval: 18 September 2015); Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Approval No. 15–29 (date of approval: September 30, 2015). All informed consent was obtained from the subjects and/or guardians.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects included in the study. Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: NA.

Animal Studies: NA.

Supporting information

Data S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Arends for editing the manuscript. We are grateful to the volunteers for their participation in the study and the anesthesiologists and surgeons for collecting the clinical data.

Zou R, Nishizawa D, Inoue R, Hasegawa J, Ebata Y, Nakayama K, et al. Effect of A118G (rs1799971) single‐nucleotide polymorphism of the μ‐opioid receptor OPRM1 gene on intraoperative remifentanil requirements in Japanese women undergoing laparoscopic gynecological surgery. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2024;44:650–657. 10.1002/npr2.12468

Contributor Information

Masakazu Hayashida, Email: mhaya@juntendo.ac.jp.

Kazutaka Ikeda, Email: ikeda-kz@igakuken.or.jp.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw data that are based on in this study are presented in a supplementary file.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kwon AH, Flood P. Genetics and gender in acute pain and perioperative opioid analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2020;38(2):341–355. 10.1016/j.anclin.2020.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frangakis SG, MacEachern M, Akbar TA, Bolton C, Lin V, Smith AV, et al. Association of genetic variants with postsurgical pain: a systematic review and meta‐analyses. Anesthesiology. 2023;139(6):827–839. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hwang IC, Park JY, Myung SK, Ahn HY, Fukuda K, Liao Q. OPRM1 A118G gene variant and postoperative opioid requirement: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(4):825–834. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al‐Mustafa MM, Al Oweidi AS, Al‐Zaben KR, Qudaisat IY, Abu‐Halaweh SA, Al‐Ghanem SM, et al. Remifentanil consumption in septoplasty surgery under general anesthesia: association with humane mu‐opioid receptor gene variants. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(2):170–175. 10.15537/smj.2017.2.16348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee SH, Kim JD, Park SA, Oh CS, Kim SH. Effects of μ‐opioid receptor gene polymorphism on postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing general anesthesia with remifentanil: double blinded randomized trial. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(5):651–657. 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.5.651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soultati I, Ntenti C, Tsaousi G, Pourzitaki C, Gkinas D, Thomaidou E, et al. Effect of common OPRM1, COMT, SLC6A4, ABCB1, and CYP2B6 polymorphisms on perioperative analgesic and propofol demands on patients subjected to thyroidectomy surgery. Pharmacol Rep. 2023;75(2):386–396. 10.1007/s43440-023-00455-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kasagi Y, Hayashida M, Sugasawa Y, Kikuchi I, Yamaguchi K, Okutani R, et al. Antiemetic effect of naloxone in combination with dexamethasone and droperidol in patients undergoing laparoscopic gynecological surgery. J Anesth. 2013;27(6):879–884. 10.1007/s00540-013-1630-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nishizawa D, Terui T, Ishitani K, Kasai S, Hasegawa J, Nakayama K, et al. Genome‐wide association study identifies candidate loci associated with opioid analgesic requirements in the treatment of cancer pain. Cancer. 2022;14(19):4692. 10.3390/cancers14194692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang J, Zhang L, Zhao X, Shen S, Luo X, Zhang Y. Association between MDR1/CYP3A4/OPRM1 gene polymorphisms and the post‐caesarean fentanyl analgesic effect on Chinese women. Gene. 2018;661:78–84. 10.1016/j.gene.2018.03.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumar S, Kesavan R, Sistla SC, Penumadu P, Natarajan H, Nair S, et al. Impact of genetic variants on postoperative pain and fentanyl dose requirement in patients undergoing major breast surgery: a candidate gene association study. Anesth Analg. 2023;137(2):409–417. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jokela R, Ahonen J, Seitsonen E, Marjakangas P, Korttila K. The influence of ondansetron on the analgesic effect of acetaminophen after laparoscopic hysterectomy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(6):672–678. 10.1038/clpt.2009.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moon YE, Lee YK, Lee J, Moon DE. The effects of preoperative intravenous acetaminophen in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(6):1455–1460. 10.1007/s00404-011-1860-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Röpcke H, Könen‐Bergmann M, Cuhls M, Bouillon T, Hoeft A. Propofol and remifentanil pharmacodynamic interaction during orthopedic surgical procedures as measured by effects on bispectral index. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13(3):198–207. 10.1016/s0952-8180(01)00255-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borrat X, Trocóniz IF, Valencia JF, Rivadulla S, Sendino O, Llach J, et al. Modeling the influence of the A118G polymorphism in the OPRM1 gene and of noxious stimulation on the synergistic relation between propofol and remifentanil: sedation and analgesia in endoscopic procedures. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(6):1395–1407. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31828e1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Melia U, Vallverdu M, Jospin M, Valencia JF, Jensen EW, Gambus PL, et al. Interaction between EEG and drug concentration to predict response to noxious stimulation during sedation‐analgesia: effect of the A118G genetic polymorphism. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2014;2014:4298–4301. 10.1109/EMBC.2014.6944575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bakhouche H, Noskova P, Svetlik S, Bartosova O, Ulrichova J, Kubatova J, et al. Maternal and neonatal effects of remifentanil in women undergoing cesarean section in relation to ABCB1 and OPRM1 polymorphisms. Physiol Res. 2015;64(Suppl 4):S529–S538. 10.33549/physiolres.933233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu J, Hu D, Jiang Y, Xi H, Li W. Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the OPRM1 gene and intraoperative remifentanil consumption in northern Chinese women. Pharmacology. 2014;94(5–6):273–279. 10.1159/000368082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Niu H, Zhao S, Wang Y, Huang S, Zhou R, Wu Z, et al. Influence of genetic variants on remifentanil sensitivity in Chinese women. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022;47(11):1858–1866. 10.1111/jcpt.13780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hannam JA, Borrat X, Trocóniz IF, Valencia JF, Jensen EW, Pedroso A, et al. Modeling respiratory depression induced by remifentanil and propofol during sedation and analgesia using a continuous noninvasive measurement of pCO2 . J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356(3):563–573. 10.1124/jpet.115.226977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liew Y, Capule FR, Rahman RA, Nor NM, Teo R, Makmor‐Bakry M. Effects of MDR1 and OPRM1 genetic polymorphisms on the pharmacodynamics of propofol‐remifentanil TIVA in pediatrics. Pharmacogenomics. 2023;24(5):247–259. 10.2217/pgs-2023-0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rhodin A, Grönbladh A, Ginya H, Nilsson KW, Rosenblad A, Zhou Q, et al. Combined analysis of circulating β‐endorphin with gene polymorphisms in OPRM1, CACNAD2 and ABCB1 reveals correlation with pain, opioid sensitivity and opioid‐related side effects. Mol Brain. 2013;6:8. 10.1186/1756-6606-6-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mieda T, Nishizawa D, Nakagawa H, Tsujita M, Imanishi H, Terao K, et al. Genome‐wide association study identifies candidate loci associated with postoperative fentanyl requirements after laparoscopic‐assisted colectomy. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17(2):133–145. 10.2217/pgs.15.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu EHY, Tran DHD, Lam SW, Irwin MG. Remifentanil tolerance and hyperalgesia: short‐term gain, long‐term pain? Anaesthesia. 2016;71(11):1347–1362. 10.1111/anae.13602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data that are based on in this study are presented in a supplementary file.